Resilience Planning With Two Tribal Governments in Virginia for Climate Hazards and Health Impacts

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

Climate change is increasing the risk, frequency, and intensity of hazards and their health impacts. Climate hazards have direct and indirect health impacts that require holistic resilience planning. Although Native American communities are among the most at-risk due to environmental and socio-economic factors, holistic climate resilience assessments have not been adapted to address their needs and interests. This study employed a qualitative approach involving interviews and workshops with citizens of the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe and the Mattaponi Indian Tribe and Reservation. In partnership with representatives from Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi, we co-produced resilience assessments, resilience priority lists, and an integration model indicating how partners, resources, and health initiatives can contribute to resilience building efforts. Our research team worked closely with tribal liaisons from the Upper Mattaponi and the Mattaponi to respect each sovereign nation’s data ownership and generate products tailored to their specific needs and contexts. Our findings indicate that the Resilience Adaptation Feasibility Tool’s (RAFT) resilience planning process met the basic needs of the Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi. We adjusted the RAFT process and products to account for the institutional knowledge, governance structure, cultural interactions, and traditional planning timeframes of the Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi. Health factors, such as housing, food security, and mental health, were linked to efforts and capacities to raise awareness, conduct outreach, and access funding for resilience. This study has two significant public health implications: (1) It offers a holistic health-hazards resilience planning process for engaging with tribal nations and adapting resilience tools to their needs and context; and (2) It develops an integrative resilience building model that leverages the participation of tribal nation partners and external resources in the context of previous and existing efforts. The RAFT scorecards and Resilience Action Checklists that we co-produced with the Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi as part of this project can be found on our project website.

Introduction

The risk, frequency, intensity, and impacts of hazards are increasing and will continue to increase due to climate change. Climate hazards impact health directly through heat-related illness, exacerbation of chronic illnesses, and exposure to pollutants. They also impact health indirectly through increased food insecurity, reduced access to medical care, and infrastructure disruptions that lead to loss of sanitation, clean water, and shelter. The hazard-health relationship requires holistic resilience planning. This is especially true for Native American communities who have specific relationships with the landscape and governance structures that must be carefully considered. While some Native American communities in the western United States have developed resilience plans, they are not directly transferable to eastern tribal nations, such as those in Tsenacomoco (coastal Virginia) who have less land area. Resilience processes have been tested with coastal tribal nations to address climate hazards, particularly flooding; however, these remain disconnected from health. Without a holistic assessment centered on Native American communities, resilience goals and efforts are not reflective of their experiences, capacities, and interests. The purpose of this study is twofold: (1) to develop a holistic resilience planning process for climate hazards that can be used with and by Native American communities, and (2) to develop a resilience building integration model for leveraging partnerships and capturing synergies across health-hazard initiatives.

Literature Review

Climate Hazards and Health Impacts

Climate change increases the risk, frequency, and intensity of extreme events like heat waves, heavy downpours, and flooding from precipitation and coastal storm surges. The intensity, frequency, and/or duration of hurricanes, winter storms, precipitation, and extreme heat events are increasing and will continue in the future (Reidmiller et al., 20191). Along the northeast and mid-Atlantic coasts, sea level rise has further increased the frequency and severity of flooding events (Atkinson et al., 20132; Ezer, 20133; Ezer & Atkinson, 20144; Ezer et al., 20135; Ezer & Corlett, 20126). The health impacts of these climate hazards include exposure to pollutants, heat-related illness, and exacerbation of chronic illnesses. Increased flooding and extreme heat can cause disruptions to power supply, overwhelm clean water and wastewater infrastructure, strain shelter options, and reduce accessibility to medical facilities and healthy food, which can further exacerbate negative impacts to population health (Keim, 20087). For example, flooding may limit access to healthy foods, and over time, food insecurity can increase the prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease (Hutton et al., 20228). Extreme heat is particularly dangerous for outdoor laborers, residents in homes without air conditioning, and older adults (Allen et al., 20229). Following a hazard, residents experiencing stress may also resort to unhealthy short-term coping responses such as relying on alcohol or drugs (Freedy et al., 199210).

The hazard-health relationship reflects a vicious cycle where hazard exposure causes negative health outcomes which in turn lead to greater vulnerability to hazards. Unhealthy residents are more vulnerable to the impacts of hazards and these health impacts further increase their vulnerability. However, the social determinants of health are generally not linked or incorporated directly into hazard resilience models that seek to improve the ability to bounce back from a hazard by improving the political, socio-economic, structural, and environmental conditions that increase a population’s risk (Hutton et al., 2022; Birkmann, 200611; Wisner et al., 201412). Similarly, quantitative resilience assessment and planning are prone to overlook the intertwined health components of risk (Weichselgartner & Kelman, 201513).

Assessing Climate Resilience Planning Needs With Tribal Governments

Climate change impacts do not affect all communities in the same way; a one-size-fits-all approach to resilience and planning efforts may overlook the needs of certain segments of the community. Low-income communities, communities of color, medically vulnerable groups, Indigenous peoples and tribal nations, and immigrant communities may suffer first and worst from the effects of climate change (Birkmann, 2006; Chambers, 198914; Cutter, 199615; Dow, 199216; Liverman, 199017; Wisner et al., 2014). These communities may also experience higher costs for energy, utilities, transportation, and necessities; fewer quality jobs and educational opportunities; higher levels of poverty; greater exposure to environmental hazards and pollutants; limited access to public services and health care facilities; and are served by outdated and weak critical infrastructure. They have fewer resources to cope with the risks of climate change and disproportionately bear the impacts of climate hazards. Furthermore, these communities have often been excluded from planning and policy processes that affect them and their responses to climate impacts.

Each Native American community has unique circumstances, such as governance structures, land ownership arrangements, traditional land-uses, and formal relationships with the state and federal government that must be accounted for in resilience planning. In many tribal nations, climate change has begun impacting the health and livelihoods of citizens in substantial ways. For example, flooding increases erosion and reduces access to environmental resources to support cultural livelihoods dependent upon fisheries and clay deposits (Curry et al., 201118; Hutton & Allen, 202019). These impacts are attributable not only to relationships with the landscape that put individuals engaged in traditional livelihoods at increased risk of exposure to pollutants but also to socio-economic conditions surrounding reservation lands that feature limited resources for employment, health care, and healthy food. Climate impacts also exacerbate vulnerabilities—, such as inadequate infrastructure and high poverty rates—that already make it more difficult for citizens in tribal nations to access resources (Norton-Smith et al., 201620). For example, tribal nations in Virginia recently identified in risk assessments that frequent flooding of reservation roadways reduced access to goods and services (Hutton & Allen, 2020).

Native American communities must prepare for climate hazards by assessing the resilience of their land and community and creating a plan to address their specific vulnerabilities. Long-term plans of up to seven generations, significantly longer than locality and state planning periods, have been defined as appropriate by traditional ecological knowledge holders (Hutton & Allen, 2020). Extended planning periods are also necessary because federally recognized tribes go through the Bureau of Indian Affairs to implement some traditional ecological knowledge informed solutions, such as relocation (Hutton & Allen, 2020). Further, because residents do not individually own the reservation land on which their homes sit, loans to build or modify structures are limited. Limited taxation of tribal citizens by the tribal government and disconnected parcels also reduces the capacity to implement mitigation and adaptation strategies for the whole reservation, such as installing living shorelines or rip rap, without grant funding.

Native American communities throughout the United States have already begun to develop and implement resilience efforts through climate vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans. These assessments and plans highlight the history and values of each Native American community, the community’s current state, and actions the community will take to build resilience. Many tribal resilience plans are the works of tribal nations located in the western United States (University of Oregon, 202221). While some strategies are transferable, Native American communities in the west tend to have larger land areas and deal less with sea level rise caused by climate change. Eastern tribal nations have engaged in logic model informed processes to identify how traditional ecological knowledge would guide resilience strategies (Bethel et al., 201122; Hutton & Allen, 2020); however, these assessments have not examined health implications.

Native American communities in Viriginia already have governmental structures in place, such as councils and varying offices and departments that can support resilience planning and implementation. Virginia Indian tribesEndnote have tribal councils and government structures in place that can identify resilience planning staff and citizens (Saenz, 202023; Wood, 200824). Various data and information sources are available to support vulnerability assessment, such as death records that tribal governments have specific rights to but can be difficult to access, as well as census data, which is useful to some but not inclusive of all. Institutional knowledge, including but not limited to traditional ecological knowledge, should also inform assessment.

Resilience planning for Native American communities does not happen in a vacuum. In Virginia, existing state and local plans—such as comprehensive plans, hazard mitigation plans, and emergency operations plans—provide multi-faceted planning resources for tribal nations. Neighboring jurisdictions, service agencies, and nonprofit organizations can contribute to tribal resilience planning efforts. Further, tribes must interact with local and regional stakeholders, such as first responders, electricity providers, and railway companies to manage resources running through reservation property. Recognition at the state level elevates tribal issues and expedites response post-disaster, particularly when multiple jurisdictions or state-wide actors are involved. Relationships between tribes, service agencies, and nonprofit organizations exist regardless of jurisdictional engagement and may be bolstered by tribal networks, such as United South and Eastern Tribes Inc., a national nonprofit, and Kenah Consulting, a local Tribal agency. Health care and food provision through mobile distribution are both examples of nonprofit interactions facilitating tribal resilience.

Like localities (i.e., counties and cities), Native American communities need to develop plans that best meet their strengths, weaknesses, and current capabilities. An international survey of research shows that Indigenous people have expressed interest in merging traditional knowledge with emergent technologies including grey (e.g., rip rap) and green (e.g., living shoreline) infrastructural solutions to build resilience (Gómez-Baggethun et al., 201325) and participating in co-production activities that support advancement of resilience priorities (Bethel et al., 2011). Incorporating traditional knowledge is critical for supporting tribal resilience planning that is often under-resourced and disconnected from the mitigation plans of adjacent localities. While a comprehensive national assessment of existing tribal plans was beyond the scope of this study, no common structure or form for resilience planning has been identified across Virginia Indian tribes.

Adapting the Resilience Adaptation Feasibility Tool for Coastal Virginia Indian Tribes

Virginia Indian tribes are noted as contributing to regional resources in hazard mitigation plans, particularly through their fish hatcheries, but it is their prerogative to integrate themselves as they see fit. While some Virginia Indian tribes choose to be added to the nearest planning district’s hazard mitigation plans, others may not. Although the Commonwealth of Virginia’s requirements for planning do not apply to all Virginia Indian tribes in the same ways that they apply to localities, tribal nations may adopt regional plans. The Resilience Adaptation Feasibility Tool (RAFT), a process endorsed by Virginia’s Coastal Resilience Master Plan, could be adapted to tribes to increase tribal capacity to obtain funding and advocate for comprehensive resilience priorities.

The RAFT is a planning process that approaches community resilience holistically by considering environmental, social, and economic resilience. Community health is a dimension of the RAFT (Yusuf et al., 202226), focusing on physical and mental wellbeing and the provision of food, health, and medicine. The RAFT was developed by a leadership team from three universities, including the University of Virginia’s Institute for Engagement and Negotiation, William and Mary’s Virginia Coastal Policy Center, and Old Dominion University. Since 2015, 28 coastal localities in Virginia have used the RAFT to advance planning by identifying resilience gaps and progressing locality-centered goals ranging from flood mitigation to food and housing security.

The RAFT process involves three steps: (1) assessment via a scorecard and qualitative interviews and focus groups, (2) development of a community-driven plan, and (3) implementation of the plan through specific resilience-focused projects. The RAFT Scorecard assesses resilience in five areas:

- Leadership and collaboration

- Risk assessment and emergency management

- Infrastructure

- Planning

- Community engagement, health, and wellbeing

The RAFT Scorecard was originally developed specifically for coastal hazards such as storms and flooding. Parallel to Virginia’s 2023 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update, it was revised to include extreme heat. The Scorecard is completed by the RAFT Team based on public policy documents and qualitative interviews of community representatives including the Planning District Commission, and City Council members, non‐profits, community organizations, critical service providers, and other groups identified using snowball methods. A report of the qualitative findings is shared with participants alongside the Scorecard.

Building off the resilience assessment, community stakeholders come together in a planning workshop to co-produce a Resilience Action Checklist, a resilience priority list that identifies four to five resilience priorities for the community to pursue over the next year. A volunteer implementation team is formed by residents, community and business leaders, nonprofit agency representatives, local officials, and state agencies to progress the checklist via resilience-focused projects.

In 2022, the RAFT Mini and Micro-Grant Fund and the Regional Resiliency Equity Workgroup were established to reinforce support in 16 RAFT alumni localities. The RAFT Mini and Micro-Grant Fund provided 14 grants to fund nonprofit organizations and localities conducting resilience projects ranging from food security to cultural site restoration. The workgroup is a set of volunteers from nonprofits, locality and tribal representatives, and residents that meet monthly to address topics ranging from transit, food security, economic development and living wages, health care and mental wellbeing, affordable housing and shelters, and programs for youth and families. The capacity to launch such support for additional localities is request-driven and funding dependent.

The RAFT process has included citizens of adjacent tribal nations in developing the Resilience Action Checklist and comprising the implementation team for several coastal Virginia localities, as well as, participating in the Regional Resiliency Equity Workgroup and the RAFT Mini- and Micro-grant Fund. However, for the RAFT to be appropriate and useful for tribal nations themselves, the process requires that it be adapted to the specific tribal contexts because tribes may not be subject to the same regulations as localities, are differently resourced and connected than localities, and do not have to make their policies a matter of public record.

Research Questions

This study adapts a tool for resilience assessment and resourcing and fills a gap in the literature linking existing priority setting strategies for environmental hazard mitigation with social determinants of health to improve resilience more holistically. Without a process specifically tailored to their needs, tribes do not receive the full benefit of the RAFT, or any other resilience tool. To address the issues identified in the literature, this study addresses two research questions:

- How can the RAFT process be adapted to reflect health implications of climate hazards in tribal nations?

- How can tribal nations leverage synergies between external partners and internal resources at the health-hazards nexus to bolster resilience building efforts?

This study adapted the RAFT to tribal community contexts and governance structures. We worked with two coastal Virginia Indian tribes in applying the RAFT process of resilience planning and implementation. In addition to co-producing the RAFT with our partners, we also aimed to build an integration model that other tribal nations could use to engage external partners in addressing climate hazards and their health implications comprehensively.

Research Design

This study used an iterative participatory research process to co-produce RAFT Scorecards and Resilience Action Checklists that were adapted to the contexts of Virginia Indian tribes. Based on these products, a Tribal Resilience Building Integration Model was produced to highlight the role of health in complementing tribal resilience efforts through funded projects. Qualitative methods provided detailed reflection upon the applicability of the RAFT process, resilience priorities, and resourcing requirements to achieve resilience goals.

This process was adapted based on the literature about tribes in coastal Virginia that engaged tribal liaisons to assess and prioritize resilience to sea level rise (Hutton & Allen 2022). We partnered with the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe and the Mattaponi Indian Tribe and Reservation. With each of our tribal nation partners, we conducted an interview with one liaison and a workshop including up to ten participants. Interviews were 1.5 hours long and the workshops were 6 hours long. Interviews were conducted on Zoom and the workshops had a hybrid format with an in-person component at a location of the liaison’s choosing that was convenient for the participants and a Zoom option for those unable to attend in-person. This abbreviated RAFT process relied upon the liaisons to draft a Scorecard, recruit workshop participants, and approve products so that researchers were not (a) in contact with documents that are not a matter of public record outside the tribe, (b) making determinations about qualifications for workshop participation, or (c) misrepresenting or too broadly sharing proprietary institutional or traditional knowledge.

Study Site and Access

We recruited representatives of coastal Virginia Indian tribes from several sources, including contact information from the RAFT team, RAFT Fund grantees, and members of the Regional Resiliency Equity Workgroup. We contacted representatives of five sovereign nations of Virginia and two agreed to participate: the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe and the Mattaponi Indian Tribe and Reservation. We only recruited representatives from coastal Virginia due to the increased likelihood of flooding resulting from sea level rise. Based on scoping conversations with regional consultants, this work was not found to be directly duplicative of other work underway. Both tribal nations were engaged in RAFT activities prior to the study and have avenues to stay engaged afterward.

The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe is one of the seven federally recognized tribal nations in Virginia. The Mattaponi Indian Tribe and Reservation is one of the four tribal nations recognized by the state of Viriginia but not by the federal government. Of note, the Mattaponi Chief and Council engaged in this study are recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia. The Upper Mattaponi and the Mattaponi both have property adjacent to Upper Mattaponi, Mattaponi, and Pamunkey lands (King William County, VA) along the Mattaponi River, a tributary to the York River, which empties into the Chesapeake Bay. King William County is in the Middle Peninsula, a rural region of Virginia between Richmond and Williamsburg that underwent a RAFT process from 2021–2023.

Data Collection Methods

Interviews

Liaisons from the Upper Mattaponi and the Mattaponi were recruited from RAFT Fund and Regional Resiliency Equity Workgroup contacts. The Upper Mattaponi liaison was a staff member, and the Mattaponi liaison was a member of the Tribal Council. During the interview, the liaison went through each element of the RAFT Scorecard to revise the language and categories to account for tribal contexts, provided an initial score for applicable categories, and explained the reasoning behind each score.

Workshops

Liaisons recruited up to ten participants from their respective tribal nations, including but not limited to, tribal nation staff, citizens, traditional ecological knowledge holders, and members of council with experience the liaison deemed relevant for the Resilience Workshop. During the workshop, participants provided input on the Scorecard. Scores and language were adjusted according to the consensus reached during the workshop and any internal information provided by the liaison after the workshop in direct response to requests made during the workshop. A checklist of resilience priorities was also produced based on the workshop discussion. The RAFT Team and tribal liaison co-facilitated the workshop. Ten participants attended the Upper Mattaponi workshop on February 15, 2023, including staff, citizens, and a Council representative. Eight participants attended the Mattaponi workshop including local residents, citizens of the diaspora, and the Chief on February 25, 2023. The Workshop began with a fifteen-minute presentation of the RAFT process and research objectives. Then, the workshop discussion went through the Scorecard section by section. The same guided semi-structured questions were used for each section covering: (a) areas of the Scorecard missing or inadequately representing information, (b) irrelevant areas or areas in need of alteration within the Scorecard, (c) gaps from the Scorecard that are already being addressed, (d) gaps that would be important priorities for inclusion in a Resilience Action Checklist, (e) appropriate priorities and associated timelines in which to address the Resilience Action Items from the checklist, and (f) resource needs to address the Resilience Action Items. Approximately one hour of the workshop was allocated to each Scorecard section. The final forty-five minutes involved a review of the checklist produced during the Scorecard discussion.

Data Analysis Procedures

Two members of the RAFT Team used qualitative open coding methods to identify resilience building strategies that emerged from the Scorecard and Resilience Action Checklist generated from the interviews and workshops. Responses were then organized hierarchically to assess their interconnectivity and produce a “Tribal Resilience Building Integration Model.”

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

This study (Project # 1971333-1) was exempt from Institutional Review Board review by the Old Dominion University Arts and Letters Human Subjects Review Committee. The tribal governments of the Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi each issued a letter of support for the study approving the liaison selection and research process. The liaisons also provided updates on the progress of the RAFT at tribal council meetings or through other communication formats deemed appropriate. The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe and the Mattaponi Indian Tribe and Reservation retain the rights to any respective institutional and traditional knowledge collected during this process. The workshop was recorded by the liaison and remains the property of each tribal nation. The information reported has been approved by government representatives (e.g., Chief and/or council) of each tribal nation as advised by the respective liaisons. Any further data usage or reproduction requires additional approval.

Findings

RAFT Process Application to Native American Communities

The RAFT process is applicable to Native American communities; however, some sections of the Scorecard were modified to better reflect tribal culture and structure. Regarding the Scorecard and the Commonwealth's Climate Resilience Taskforce, an Upper Mattaponi participant stated, “Cultural assets aren’t included fully and are very important to tribal nations.” Elaborating on the difficulty in including cultural assets in scoring, the same Upper Mattaponi participant stated, “Grave sites and people with specific skill sets can be included in cultural assets, which can be difficult to identify.” This demonstrated that resources are not just policy-based or infrastructural, but that they included human resources, such as traditional knowledge holders or past leaders, and also showed that locations and identities were of particular concern for personal and site safety. For example, grave robbing may occur for sites that do not fall within reservation boundaries and protecting traditional ecological knowledge holders from hazards and health issues is a priority. More cultural focus was added to the Leadership, Risk, Planning, and Community sections of the Scorecard and language was changed to reflect variations in leadership (i.e., being elected and/or appointed), land utilization, and funding streams, as well as the influence of extreme cold. These changes were made before the workshop based on the liaison interviews and again after the workshop to reflect participant input. The final Scorecards for the Upper Mattaponi and the Mattaponi include the full set of modifications.

The qualitative assessment was utilized exclusively in this study, rather than in conjunction with policy analysis as is usually done in the RAFT process, because tribal policies are not a matter of public record. The Upper Mattaponi Scorecard Report reveals that the Upper Mattaponi score was 54 out of 110 whereas the Mattaponi Scorecard Report shows that the Mattaponi score was 50 out of 110. These scores place both tribal nations in the low resilience category, less than 50 percent, with opportunities for improvement. The strongest categories for the Upper Mattaponi were Community and Risk. The categories with the most opportunity for improvement for the Upper Mattaponi were Planning and Infrastructure. The strongest categories for the Mattaponi were Community and Risk. The categories with the most opportunity for improvement for the Mattaponi were Leadership and Infrastructure.

The Resilience Action Checklists were also adapted to include more than the five goals that are usually part of the RAFT. In addition, the one-year implementation timeframe was extended to accommodate the longer planning timelines that Virginia Indian tribes described as traditional in their contexts. Instead, goals were sorted by priority (i.e., high to low) and amount of time for completion ranging from short (i.e., less than one year) to medium (i.e., one to two years) and long (i.e., three or more years). The Upper Mattaponi Resilience Action Checklist shows how the Upper Mattaponi selected seven short-term goals out of 17 total with seven high priority goals. The Mattaponi Resilience Action Checklist shows how the Mattaponi selected nine short-term goals out of 20 total with 17 high priority goals. Action items for the Upper Mattaponi included six related to Leadership, one for Risk, four for Infrastructure, and three each for Planning and Community. Action items for the Mattaponi included six related to Leadership, five for Risk, five for Infrastructure, one for Planning, two for Community, and one other that did not fit into the associated categories.

Leveraging Variation Towards Resilience

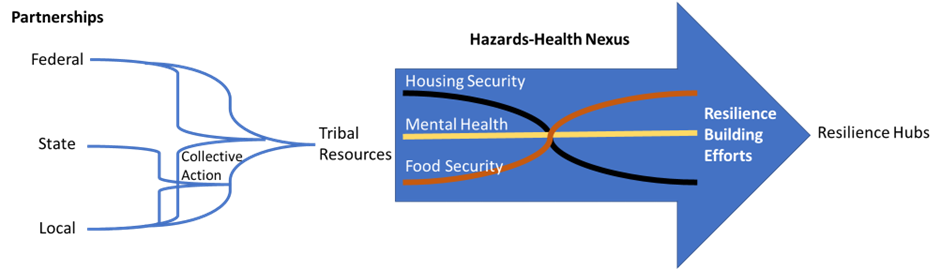

The varying experiences and opportunities documented in the Scorecards and Resilience Action Checklists inform an integrated resilience building model (Figure 1). Commonalities between the Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi occurred in the need for additional resilience trainings for leadership, a way to share emergency alerts and information with local and distant tribal citizens, increased outreach to medically-fragile populations, access to medical records and mental health trainings available specifically to Native Americans, improving volunteer programs, ongoing documentation of traditional knowledge of cultural assets and historic experiences with hazards, water quality and infrastructure improvements, and ultimately, turning tribal communities into resilience hubs. A resilience hub provides shelter including access to electricity and supplies. A physical or conceptual resilience hub unites these needs by making the tribal nation a base for resilience resources to provide or identify shelter and associated resources either physically, administratively, or both. Figure 1 demonstrates how Native American communities, regardless of recognition or land utilization, can work toward a resilience hub. Figure 1 begins with the various partnerships that contribute to tribal resources. Then, Figure 1 shows the hazards—health nexus wherein health related work is intertwined with and contributes to resilience building efforts that may facilitate the establishment of more formal resilience hubs. Figure 1 ends with the establishment of a resilience hub that builds on unique contexts of the land and population distribution.

Figure 1. Tribal Resilience Building Integration Model

Partnerships

Our study showed that the role of local, state, and federal partners in providing resources to tribal nations varied based in part on recognition status. The federally recognized Upper Mattaponi representatives mentioned that they had additional emergency management resources through participation in the state level Virginia Coastal Resilience Master Plan process and local Middle Peninsula Planning District Commission. Further, the Upper Mattaponi could address some concerns, such as water quality, at the federal or state levels rather than at the county level. Access to federal or state officials allowed the Upper Mattaponi to address upstream concerns, whereas county level officials could only address impacts by ensuring safety of local septic systems. On the other hand, representatives from the state-recognized Mattaponi said that they have a direct relationship with the Governor’s Office after disaster declarations and that this relationship facilitates their ability to meet immediate needs like water provision. The Mattaponi also mentioned that local personal connections with state representatives and agencies, nonprofits with state and federal advocacy capacities, federal agencies, universities, the county, a tribal consultant, and other tribes maximized efforts through collective action. The Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi representatives mentioned common partners, including: (a) health clinics, food pantries, and the electricity provider (i.e., Dominion Power) at the local level; (b) Virginia Department of Emergency Management at the state level; and (c) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (e.g., Indian Community Development Block Grants and Indian Housing Block Grant) at the federal level. United South and Eastern Tribes Inc. was a resource for collective action efforts at the regional level. Although partnerships may be generated through different relationships, the collective contributes to the resources available.

Resources

The Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi representatives noted that they had internal resources to generate newsletters, social media, and community gatherings. However, the level of staffing that each tribal nation had to produce these resources differed. Staffing was recently expanded by the Upper Mattaponi to include Emergency Management and an Environmental Department that contributed to robust emergency plan integration. However, staffing was still limited to administrative staff for the Mattaponi who were collecting historical documentation needed to apply for federal recognition. These differences in tribal staffing resources alter approaches to resilience building efforts.

The Health-Hazards Nexus for Resilience Building Efforts

While the funding that was leveraged from partners by staff, Chiefs, and Councilors was project specific, participants identified synergies at the health-hazards nexus between food security, mental health, and housing security. For example, participants identified the potential to translate mental health outreach by staff or volunteers into hazard vulnerability assessment through added or expanded home visits if the citizen is willing to have such a visit. Electricity and wireless internet projects were also identified as potential areas to integrate other housing resilience. However, workshop participants said that tribal resilience building efforts are dependent upon the land availability and use on the reservation. For example, the Mattaponi have residents on their reservation whereas the Upper Mattaponi do not. Some Virginia Indian tribes do not have reservations. Further, the differences in the ways in which land is held (e.g., in trust or as fee simple land) will make planning different. The Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi participants both expressed interest in additional land use planning to maximize resources and build resilience. Figure 1 can guide a comprehensive resilience plan for funding and land use or facilitate integrated operations in the absence thereof.

Unique features of each reservation caused some variation in efforts that progressed resilience differently but still contributed to the food security, mental health, and housing security aspects. The Mattaponi reservation features a fish hatchery, trading post, and museum that influence resilience building capacities and priorities. For example, the fish hatchery contributes to food security and has opportunities for expanding the species hatched as well as studying threats to and improving natural protections for them. The trading post and museum, however, are emergency management priorities due to the value of cultural assets within that would benefit from building reinforcement for flood protection. These resource specific priorities complement the Mattaponi’s other priorities to protect shorelines from erosion and reduce flooding by reinforcing the existing rip rap and French drains used for protection with living shorelines. The Upper Mattaponi expressed interest in the future development of the reservation through expanded land use regulations as well as dam and drainage management. Existing resources, such as chickens, community gardens, beekeeping on the reservation, and ice chairs at the Pow Wow site complement future development interests by contributing to food security, community wellbeing, and limiting heat related illness.

Resilience Hubs

The Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi expressed that a resilience hub, whether conceptual or physical in structure, would strengthen tribal resilience. The Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi prioritized hazards and health awareness outreach and provision of shelter resources on reservation land. For example, workshops participants in both tribal nations identified generators as resources and wanted to ensure that a community building and residences had them. They also expressed interest in more accessible roads, particularly ones that will not flood, which is critical for citizens to access physical resilience hubs. The structure of the resilience hubs also varied with tribal land utilization. Participants noted that Native American communities without land or with large diasporas would rely more on conceptual hubs related to communication and outreach. For example, those without land could develop a phone application or promote an existing local application to connect citizens with nearby shelter resources. Alternatively, Native American communities with reservation land may provide a building or set of buildings as a physical shelter with a variety of resources in addition to connecting citizens with individual resources via a phone application to improve the resilience of their own homes.

Conclusions

Public Health Implications and Policy Recommendations

Adaptable resilience planning processes, such as the RAFT, can be used with tribal nation partners to advance convergence-oriented science. Resilience planning tools must be co-produced with tribal nation partners to address the disparities in access to infrastructure and services that increase vulnerability to hazards in tribal nations. These disparities result in health implications specific to each tribal community. For example, our study showed that the Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi need more access to healthy food, telehealth, and cooling centers. A tribal liaison should be engaged in the research processes to ensure that resilience planning is based on the experiences and needs of tribal citizens, and that the data produced by the study will be owned by the sovereign tribal nation. Further, the process should be adaptable to accommodate different language and timelines.

Guided by the health-hazards nexus, tribal nations can organize funding, outreach, and communication efforts to bolster mental health, housing, and food security, which are intertwined with and contribute to hazards resilience efforts. Once resilience efforts are identified and prioritized, these modifications should be communicated to partners and pursued opportunistically as funding from appropriate sources becomes available. Due to resource constraints, many tribal nations may rely upon internal resources, grant funding, partnerships with food pantries, and close relationships with the state or federal governments to implement projects that improve safety and security, such as access roads, shelters, and clean waterways. The Tribal Integrated Resilience Building Model facilitates comprehensive project development wherein agencies can appropriately approach tribal nations based on the priorities expressed and resource needs identified in resilience plans produced by tribal nations.

Expanding emergency alert systems and building physical resilience hubs out of community centers offer an opportunity for enhancing hazards resilience while improving mental health, housing, and food security. Native American communities, in conjunction with health departments, should pursue increased access to health data (e.g., death records) and mental health resources available to them to improve outreach and awareness raising efforts. Without access to data and resources, institutional knowledge and partnerships with health clinics are central to identifying and supporting medically fragile populations. Communication is key to maintaining an accurate understanding of individual and collective resources and capacities.

Future Research Directions

The RAFT Team is exploring ways to facilitate implementation of the Resilience Action Checklist with the Upper Mattaponi and the Mattaponi and to test the applicability of the RAFT process with other Virginia Indian tribes. The RAFT process and the Tribal Resilience Building Integration Model should also be tested with tribal nations outside of Virginia to explore transferability regionally as well as within and outside the Algonquian language group, of which the Upper Mattaponi and Mattaponi are a part. Language groups are suggested because they are a more appropriate way to group tribal nations than by state. Future research should also quantitatively track the role of public health related funding in synergistic resilience building for climate hazards.

Acknowledgements. This RAFT product was created with funding from the Natural Hazard Center Public Health Disaster Research Award Program. We are grateful to our funders for supporting various phases of The RAFT from 2015-Present including the Environmental Resilience Institute at the University of Virginia, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the School of Architecture at the University of Virginia, Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program, Virginia Environmental Endowment, Virginia Sea Grant Climate Adaptation and Resilience Program, Jessie Ball DuPont Foundation, and anonymous donors. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders.

Endnote: A note from the authors on the usage of “Virginia Indian tribes:” We acknowledge that language is living and changing and that terminology preferences vary among sovereign tribal nations and their citizens. The language used here reflects the guidance that we received from the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe and Mattaponi Indian Tribe and Reservation, as well as additional Virginia Indian tribes engaged by the RAFT team to date. We consulted with the tribal liaisons for the Upper Mattaponi, Mattaponi, Pamunkey, Chickahominy, Cheroenhaka Nottoway, and Nottoway about what term to use when referring to them. The tribal liaisons requested that the authors refer to them collectively as Virginia Indian tribes.

Readers can find further explanation on why sovereign tribal nations in Virginia prefer this usage in The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail (Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 2008). ↩

References

-

Reidmiller, D. R., Avery, C. W., Easterling, D. R., Kunkel, K. E., Lewis, K. L. M., Maycock, T. K., & Stewart, B. C. (2019). Fourth National Climate Assessment. Volume II: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/ ↩

-

Atkinson, L. P., Ezer, T., & Smith, E. (2013). Sea level rise and flooding risk in Virginia. Sea Grant Law & Policy Journal, 5(2), 3-14. ↩

-

Ezer, T. (2013). Sea level rise, spatially uneven and temporally unsteady: Why the U.S. East Coast, the global tide gauge record, and the global altimeter data show different trends. Geophysical Research Letters, 40(20), 5439-5444. ↩

-

Ezer, T., & Atkinson, L. P. (2014). Accelerated flooding along the U.S. East Coast: On the impact of sea‐level rise, tides, storms, the Gulf Stream, and the North Atlantic Oscillations. Earth's Future, 2(8), 362-382. ↩

-

Ezer, T., Atkinson, L. P., Corlett, W. B., & Blanco, J. L. (2013). Gulf Stream's induced sea level rise and variability along the U.S. mid‐Atlantic coast. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 118(2), 685-697. ↩

-

Ezer, T., & Corlett, W. B. (2012). Is sea level rise accelerating in the Chesapeake Bay? A demonstration of a novel new approach for analyzing sea level data. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(19). ↩

-

Keim, M. E. (2008). Building human resilience: The role of public health preparedness and response as an adaptation to climate change. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(5), 508-516. ↩

-

Hutton, N. S., McLeod, G., Allen, T. R., Davis, C., Garnand, A., Richter, H., . . . Romero, C. (2022). Participatory mapping to address neighborhood level data deficiencies for food security assessment in Southeastern Virginia, USA. International Journal of Health Geographics, 21(1). doi:10.1186/s12942-022-00314-3 ↩

-

Allen, M., Hoffman, J., Whytlaw, J. L., & Hutton, N. (2022). Assessing Virginia cooling centers as a heat mitigation strategy. Journal of Emergency Management, 20(3), 205-224. ↩

-

Freedy, J. R., Shaw, D. L., Jarrell, M. P., & Masters, C. R. (1992). Towards an understanding of the psychological impact of natural disasters: An application of the conservation resources stress model. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 441-454. ↩

-

Birkmann, J. (2006). Measuring vulnerability to promote disaster-resilient societies: Conceptual frameworks and definitions. In J. Birkmann (Ed.), Measuring Vulnerability to Natural Hazards: Towards Disaster Resilient Societies (pp. 9-54). United Nations University Press. ↩

-

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2014). At risk: Natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters. Routledge. ↩

-

Weichselgartner, J., & Kelman, I. (2015). Geographies of resilience: Challenges and opportunities of a descriptive concept. Progress in Human Geography, 39(3), 249-267. ↩

-

Chambers, R. (1989). Vulnerability, coping and policy (Editorial introduction). IDS Bulletin, 37, 33-40. ↩

-

Cutter, S. L. (1996). Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Progress in Human Geography, 20(4), 529-539. ↩

-

Dow, K. (1992). Exploring differences in our common future(s): The meaning of vulnerability to global environmental change. Geoforum, 23(3), 417-436. ↩

-

Liverman, D. M. (1990). Vulnerability to global environmental change. In: R. E. Kasperson, K. Dow, D. Golding, & J. X. Kasperson (Eds.), Understanding global environmental change: The contributions of risk analysis and management (pp. 27-33). Clark University. ↩

-

Curry, R., Eichman, C., Staudt, A., Voggesser, G., & Wilensky, M. (2011, March 11). Facing the storm: Indian tribes, climate-induced weather extremes, and the future for Indian Country. National Wildlife Federation. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Reports/2011/08-03-2011-Facing-the-Storm ↩

-

Hutton, N. S., & Allen, T. R. (2020). The role of traditional knowledge in coastal adaptation priorities: The Pamunkey Indian Reservation. Water, 12(12), 3548. ↩

-

Norton-Smith, K., Lynn, K., Chief, K., Cozzetto, K., Donatuto, J., Redsteer, M. H., ... & Whyte, K. P. (2016). Climate change and Indigenous peoples: A synthesis of current impacts and experiences (General Technical Report PNW-GTR-944). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/treesearch/53156# ↩

-

University of Oregon. (2022, October 5) Tribal Adaptation Plans. Tribal Climate Change Guide. https://tribalclimateguide.uoregon.edu/adaptation-plans ↩

-

Bethel, M. B., Brien, L. F., Danielson, E. J., Laska, S. B., Troutman, J. P., Boshart, W. M., ... & Phillips, M. A. (2011). Blending geospatial technology and traditional ecological knowledge to enhance restoration decision-support processes in coastal Louisiana. Journal of Coastal Research, 27(3), 555-571. ↩

-

Saenz, M. (2021, September) Statewide Tribal legislation database. National Conference of State Legislatures. https://www.ncsl.org/quad-caucus/statewide-tribal-legislation-database ↩

-

Wood, K. (Ed.). (2008). The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. https://www.virginiahumanities.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/VA-Indian-Trail-Guide.pdf ↩

-

Gómez-Baggethun, E., Corbera, E., & Reyes-García, V. (2013). Traditional ecological knowledge and global environmental change: Research findings and policy implications. Ecology and Society, 18(4). ↩

-

Yusuf, J.-E. W., Cobb, T. D., Andrews, E., Gladfelter, S., & Montrose, G. (2022). The Resilience Adaptation Feasibility Tool (RAFT) as an approach for incorporating equity into coastal resilience planning and project implementation. Shore & Beach, 90(4), 53-63. ↩

Hutton, N. S., Yusuf W., & Palma J. (2023). Resilience Planning With Two Tribal Governments in Virginia for Climate Hazards and Health Impacts (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 30). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/resilience-planning-with-two-tribal-governments-in-virginia-for-climate-hazards-and-health-impacts