Do Virtual Reality Hazard Simulations Increase People’s Willingness to Contribute to Hazard Mitigation?

Results From An Experiment

Publication Date: 2025

Abstract

This study explored the impact of virtual reality (VR) simulations on public perceptions and behaviors related to climate change, focusing on Galveston, Texas. Using a quantitative research approach, we conducted an experimental design that involved participants experiencing immersive VR scenarios depicting extreme weather events, followed by participation in a public goods game to evaluate their willingness to contribute to climate resilience efforts. Data collection methods included surveys, VR simulations, and subsequent behavioral analysis. The findings indicate that participants who were exposed to detailed informational content (control group) contributed more consistently to climate resilience than those exposed to immersive storm surge simulations (treatment group). Additionally, higher levels of education were positively associated with increased contributions, whereas older participants showed less willingness to contribute. These results suggest that providing comprehensive information, alongside immersive experiences, rather than solely relying on immersive experiences, may be more effective in fostering proactive mitigation behaviors. The implications for practice highlight the need for policymakers to incorporate educational interventions and information-based strategies alongside experiential tools like VR to enhance public engagement in climate adaptation, with a particular focus on tailoring communication strategies by age and education level.

Introduction

Climate change poses significant threats to both ecosystems and human societies, but its future impacts often lack urgency in public consciousness. Unlike immediate social issues, the long-term effects of climate change are not highly salient to the average citizen (Baumgartner et al., 20091). Consequently, despite the pressing need for cities to build resilience against these future impacts, public risk perceptions of climate change remain relatively low. This lack of urgency is problematic, as it hinders proactive measures necessary for effective adaptation and mitigation. Extreme weather events, however, are expected to increase in frequency and intensity due to climate change (Chan et al., 20182). These events are highly salient and can potentially influence public perceptions of climate change risks. For instance, experiencing a severe flood or hurricane might make the abstract concept of rising sea levels more immediate and personal.

Galveston, Texas, with its high future risks from climate change and relatively low public risk perceptions, provided an ideal setting for this experiment. The city's vulnerability to hurricanes and rising sea levels presents a tangible context for our study. Higher seas mean more damaging floods, and hurricanes threaten Galveston every year, making the risk highly salient to the general population. With the most severe climate change scenario predicting the potential for sea levels to rise as much as 14 feet in the next 130 years (Mendelsohn et al., 20123), there is an urgent need for effective public communication and engagement strategies (Warner & Tissot, 20124).

Literature Review

Virtual Reality in Education

Virtual Reality is a powerful educational tool that enhances learning through immersive, interactive experiences (Bowman & McMahan, 20075; Jensen & Konradsen, 20186). It allows the simulation of otherwise inaccessible situations due to time, location, or ethical reasons (Freina & Ott, 20157; Slater & Sanchez-Vives, 20168). In climate change education, VR makes abstract concepts like extreme weather impacts more tangible, potentially raising awareness and motivating climate action.

Studies show VR improves understanding and retention of complex topics. For example, it has been used to educate the public on flood risks (Gneezy & Imas, 20179). D’Amico et al. (202310) reported improved flood safety knowledge using VR, while Calil et al. (202111) showed that VR fosters community engagement in coastal risk planning by bridging psychological distance. Fauville et al. (202012) found VR effective in visualizing invisible climate impacts, which fostered emotional connections and pro-environmental behaviors. Mol et al. (202213) highlighted that VR flood simulations not only enhance understanding but also encourage investment in risk-reducing actions.

These experiences evoke emotional responses that support learning and motivate action, demonstrating VR's value in climate change education. VR also allows users to experience scenarios that are impractical to replicate in everyday life, like future climate conditions and extreme events, providing impactful learning opportunities. However, Mikropoulos and Natsis (201114) suggest that the novelty of VR may not be as effective for long-term knowledge retention compared to well-designed learning activities.

Empirical Studies on Public Perception

Empirical research has investigated the relationship between experiencing extreme weather events and increased climate change risk perceptions, often hypothesizing a Bayesian updating process—a statistical framework in which individuals revise their prior beliefs as they receive new information—where tangible evidence influences public understanding (Larcom et al., 201915; Van Gevelt et al., 201916). However, findings are mixed: while some studies find a positive link between experiencing extreme weather and increased risk perceptions (Konisky et al., 2 01617), others do not observe significant associations (Carmichael et al., 201718; Mildenberger & Leiserowitz, 201719).

Public perceptions are influenced by multiple factors beyond extreme weather experiences, such as personal experience, media coverage, and pre-existing beliefs. Personal experiences may encompass a broad range of interactions with climate and environmental factors, not limited to direct encounters with extreme weather events. For example, McDonald et al. (201520) noted that personal experiences can reduce the psychological distance of climate change, but this reduction might lead to avoidance rather than proactive behavior. Individuals with direct experience of severe weather may better recognize climate risks (Leiserowitz et al., 200821). Simpson et al. (202222) found that while VR improved users' spatial understanding of flood impacts, it did not increase their personal risk perception, showing the nuanced effect of immersive experiences.

These mixed results reflect the complexity of the public’s climate risk perceptions, shaped by a combination of personal experiences, media, and beliefs. Research is thus needed to develop innovative methods to better understand and influence public perceptions of climate risks.

Methodological Challenges and Innovations

The majority of empirical studies exploring the link between extreme weather events and climate change perceptions rely on retrospective surveys and observational data, which face limitations like non-random assignment and recall bias, hindering causal inference (Howe et al., 201923). Virtual Reality technology also ensures standardized experiences across participants, enhancing both reliability and validity by reducing individual interpretation variability (Fan et al., 202224). Standardization of VR elements, as emphasized by Peeters (201825), supports experimental consistency across different settings and participant groups, making findings more reproducible and applicable.

Moreover, incorporating realistic VR elements improves user engagement and presence, which is crucial for eliciting authentic affective and cognitive responses to climate scenarios (Newman et al., 202226). Queiroz et al. (202327) highlighted the importance of message framing and physical interaction within VR, contributing to improved learning outcomes and increased self-efficacy.

In summary, while previous studies have demonstrated the potential of VR in enhancing climate change awareness, they often face limitations in terms of ecological validity, generalizability, and long-term impact on behavior. Existing research also varies in its effectiveness across different demographic groups and lacks standardized methods to measure VR's impact on climate perception and action. This study addressed these gaps by using a controlled experimental design that combines controlled VR simulations with real-world relevance, enhancing ecological validity. The VR simulations allowed for random assignment, isolating the effects of experiences on climate perceptions and behaviors, thereby strengthening the causal inferences of our findings. Additionally, by standardizing VR elements and employing rigorous data analysis methods, this research aimed to provide more reliable and applicable findings.

Research Questions

This study investigates how VR simulations of extreme weather events impact public perceptions of climate change and subsequent adaptive behaviors. Specifically, our research sought to answer the following questions:

How does the order of VR simulations (flooding vs. informational) influence participants' willingness to contribute to climate change mitigation efforts?

How do contribution behaviors differ between participants exposed to a VR simulation of flooding and those provided with informational content through charts and photographs?

How do participants' demographic backgrounds and pre-existing beliefs about climate change influence their behaviors and perceptions in the VR environment?

Research Design

This study involved designing and implementing immersive virtual reality (VR) simulations and a public goods game to evaluate participants’ perceptions of climate change and their willingness to contribute to resilience efforts. The experimental setup integrated both VR storm surge scenarios and structured informational content, enabling a controlled comparison of participant behaviors across treatment and control conditions. A quantitative research design was then employed to collect objective, numerical data on participants’ decisions and responses, allowing for rigorous statistical analysis of their engagement with climate change scenarios.

Treatment Scenario: Virtual Reality Simulations of Hazard Events in Galveston, Texas

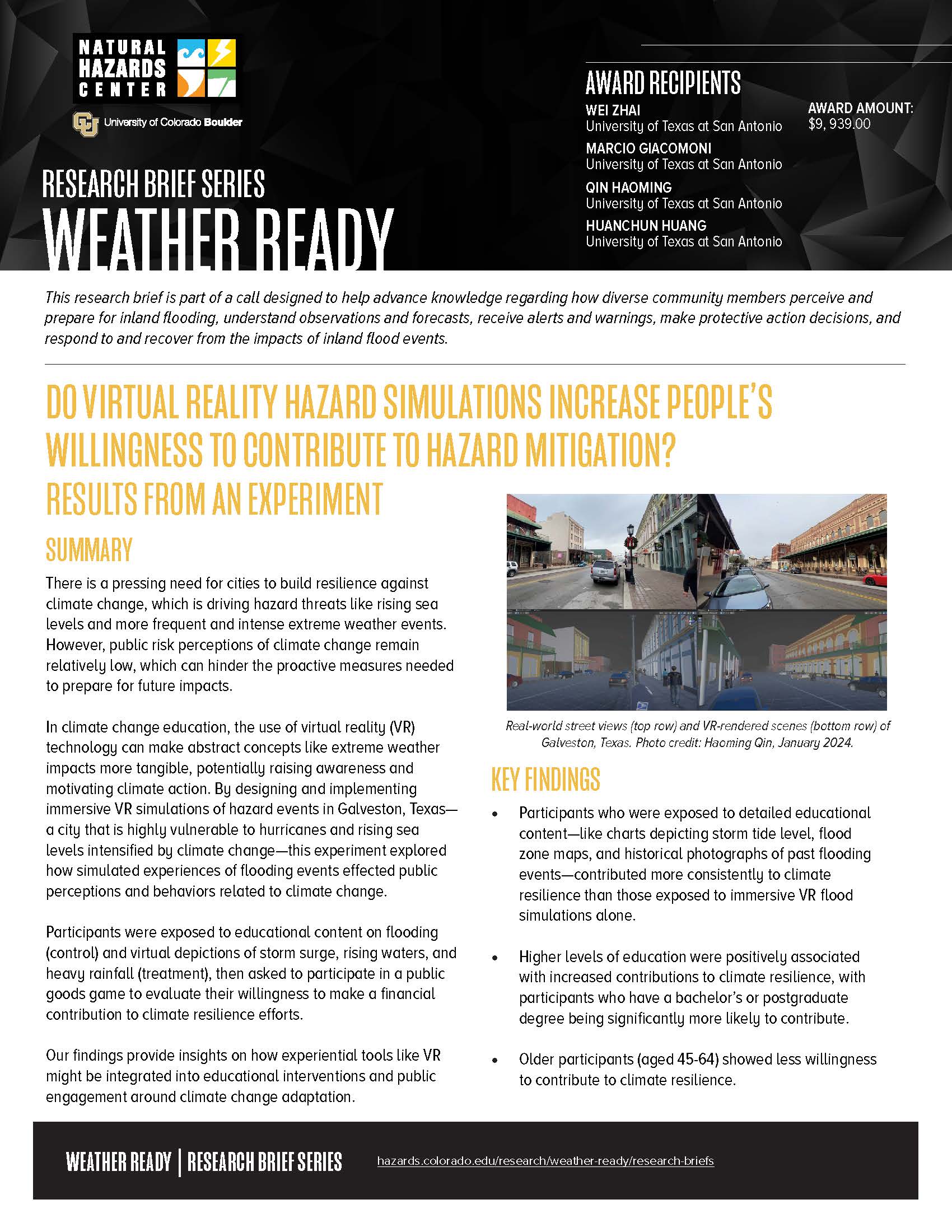

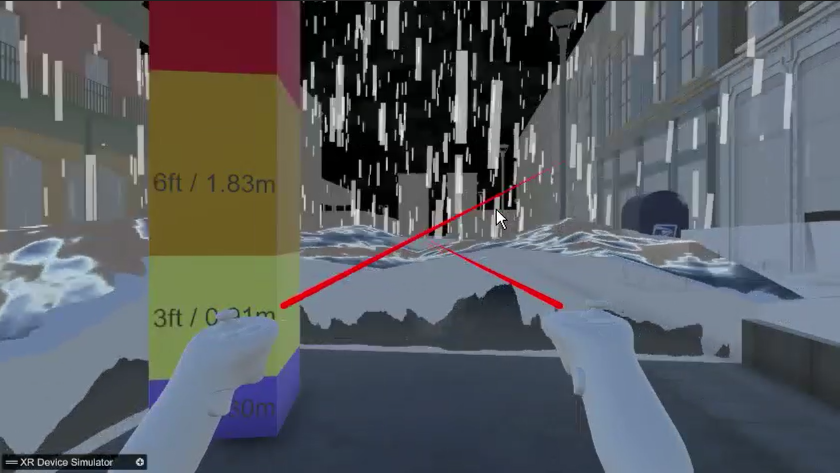

The VR simulations were modeled on Galveston, Texas, due to its high vulnerability to hurricanes and rising sea levels intensified by climate change. To build a realistic and contextually rich environment, we first used detailed building footprint data and GIS-based elevation information to reconstruct the city’s urban layout in SketchUp. These models were then imported into Unity, where we developed the immersive simulation environment. The simulation incorporated dynamic visual and auditory elements, such as storm surge flooding, heavy rainfall, and ambient soundscapes, to heighten the sense of immersion. Historical data on Galveston’s past flood events and storm surges were integrated to provide narrative depth and contextual realism. This combination of physical modeling and environmental storytelling aimed to evoke a stronger emotional and cognitive response from participants. All participant interactions, including movement within the VR environment and their choices during the public goods game, were automatically logged to facilitate rigorous quantitative analysis. Figure 1 displays the VR simulation scenes, designed to reflect real-world locations in Galveston using images and data from actual sites to enhance realism. In the Flood Simulation scenario, participants were immersed in a sequence of heavy rainfall followed by progressively increasing flood levels over five rounds (ranging from 1 foot to 9 feet of flooding).

Figure 1. Comparison of Real-World Location and Virtual Reality Simulation

Control Scenario: Structured Informational Content

In the control scenario, participants were presented with structured informational content that summarized Galveston’s flooding risks and historical hurricane events. The content included a series of historical photographs (e.g., the 1915 Jefferson Hotel flood and Hurricane Harvey street flooding in 2017), charts depicting storm tide levels from 1880 to 2017, and flood zone maps showing inundation at 1, 3, 6, and 9 feet. These visual materials were organized to convey the same key information as the VR scenario, but in a non-immersive format, allowed us to isolate the effects of immersion and interactivity by comparing the control group’s responses with those exposed to the VR treatment. These visualizations emphasized the potential damage from rising flood levels, with a particular focus on vulnerable areas like the communities surrounding the Offatts Bayou estuary.

The Public Goods Game

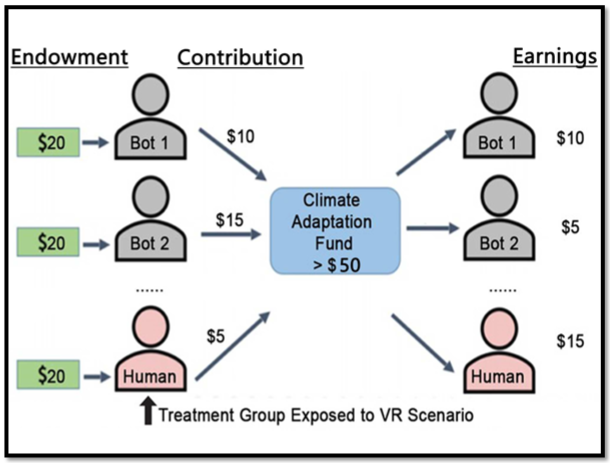

Our public goods game was designed to evaluate participants’ willingness to contribute to Galveston’s climate resilience. Figure 1 demonstrates how the public goods game was structured. Prior to starting the game, participants were informed that their objective was to decide how much to contribute to the collective climate fund while retaining their personal balance, simulating the trade-off between individual benefit and collective resilience. They were told that the group’s goal was to collectively meet a resilience threshold, which would represent effective community investment in climate preparedness. Each participant was given $20 endowment as starting funds, and they were told that this balance could either be retained or partially contributed to the collective climate fund during each round. Participants then engaged in five rounds of the game. Each game consisted of five players: one human participant and four bots (computer-controlled players designed to simulate the decisions of other participants). In each round, the participant decided how much ($0–4) to contribute to a collective climate fund (“contribution”), while the remaining amount was retained as their personal balance (“earnings”). The contributions from all players were pooled simultaneously each round, and the total fund was used to represent investments in building Galveston’s resilience to climate change. Each bot followed a pre-programmed strategy and contributed a fixed amount to the fund each round.

Figure 2. Public Goods Game With Virtual Reality Scenarios

At the end of each round, participants were shown the total contribution to the climate fund and how much was needed to meet the $50 threshold. If the threshold was met, participants retained the money they did not contribute (e.g., contributing $5 meant keeping $15). This represented a scenario with sufficient adaptation funds for climate resilience. If the target was not met, participants faced a 50% chance of losing their remaining funds, symbolizing insufficient adaptation, as determined by a simulated coin toss.

Experimental Design

Each participant was assigned to experience both the Flood Simulation (treatment) and the Hurricane Information (control) scenarios in alternating order to control for order effects. Specifically, the first participant experienced the Flood Simulation scenario first, followed by the Hurricane Information scenario. The second participant began with the Hurricane Information scenario, followed by the Flood Simulation scenario. This alternating order continued for all participants, ensuring that each participant experienced both scenarios but in different sequences. This design helped control for potential order effects, minimizing bias by balancing the influence of the first scenario on subsequent behavior.

Participant Recruitment and the Experiment’s Procedures

From January to October 2024, we recruited 45 volunteers and conducted the experiment primarily in our office using Quest 2, as well as at VizLab at the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA). Participants, who had to be at least 18 years old, received a $10 Amazon gift card for their time.

Prior to the experiment, each participant was briefed on its purpose and underwent the informed consent process. Next, participants completed a survey with questions about their demographic and socio-economic backgrounds as well as questions about their climate change knowledge and beliefs. The full survey instrument is available in the Appendix. The survey was administered using Google Forms.

After completing the survey, participants were instructed how to play the public goods game and completed a practice round. After completing the survey and a practice round, participants proceeded to play the public goods game. In the third stage, they experienced both the Flood Simulation and Hurricane Information scenarios in an alternating order. After experiencing both VR scenarios: a Flood Simulation scenario and an Informational VR scenario, participants received their payment via Amazon gift cards. Finally, they were debriefed with information about climate change impacts on the Texas Gulf Coast and the importance of adaptation.

Data Analysis Procedures

As previously noted, assuming that risk perceptions change through a Bayesian updating process, we can measure changes in risk perceptions of climate change through observing changes in individual adaptation behavior (Larcom et al., 2019). Our experimental design allows us to compare the behavior (in terms of contributing to the climate change fund) of individuals exposed to the treatment group with the behavior of individuals in the control group. We isolated the effect of our treatment using four standard analytical approaches: First, we undertook two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (also known as the Mann-Whitney test) to see if there was a statistically significant difference between the behavior of our treatment and control groups. Secondly, we conducted paired sample t-tests to compare the mean differences in contributions before and after the treatment within the same group. This test helped us determine whether the VR simulation had a significant impact on participants' contribution behaviors by comparing their contributions in the public goods game pre- and post-exposure to the extreme weather event simulation.

Finally, we estimated a Tobit (censored) regression using our panel data with both fixed-effects and random-effects (Ashley et al. 201028). The Tobit model was appropriate for our data since contribution behaviors may have lower and upper limits. This model allowed us to account for the censored nature of the data and provided more accurate estimates of the treatment effects. By utilizing these analytical approaches, we aimed to comprehensively assess the impact of the VR simulations on climate change risk perceptions and adaptation behaviors.

Ethical Considerations

Our research team is committed to upholding ethical standards, prioritizing participants' well-being, dignity, and privacy. Recognizing the sensitivity of our work, we adhered to ethical guidelines, respecting both scientific integrity and community values. The study received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval (FY23-24-193) from UTSA. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, clearly outlining the study's purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits, and the steps we took to ensure participants’ privacy and data confidentiality. To minimize risks, we ensured simulations were considerate of participants' potential vulnerabilities.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 summarize the contributions made by participants in two different game scenarios: treatment and control. Each game consisted of five rounds where participants could contribute varying amounts to a climate change fund. The table displays the mean and standard deviation for each round and the final balance for both scenarios.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Game Contributions

| Round | Treatments ($) | Control ($) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

The average contributions in the treatment scenario generally increase from Round 1 (M = 2.21) to Round 4 (M = 3.56), then slightly decrease at Round 5 (M = 3.23). In the control scenario, the average contributions do not follow a consistent trend, with fluctuations observed across different rounds. The mean contributions start at Round 1 (M = 3.18), increase to Round 4 (M = 3.69), and then slightly decrease at Round 5 (M = 3.38). Comparing the two scenarios, participants in the control scenario tend to contribute more on average in rounds 1, 3, 4, and 5 compared to the treatment.

The standard deviation indicates the variability of contributions among participants. In the treatment scenario, the variability is highest at Round 1 (SD = 1.51) and lowest at Round 3 (SD = 1.00). For the control, variability peaks at Round 2 (SD= 1.20) and is lowest at Round 4 (SD = 0.89). Overall, the variability in contributions is slightly higher in the treatment, indicating more consistent behavior among participants.

The final balance, which represents the remaining endowment after all contributions, is higher on average in the treatment scenario (M = 4.67) compared to the control (M = 3.74). However, the variability in the final balance is also lower in the treatment (SD= 2.94) than in the control (SD= 3.13), suggesting that participants' endowment outcomes are slightly more consistent in the treatment scenario. These descriptive statistics suggest that participants tend to contribute higher amounts in the control scenario, especially in the early and final stages. Additionally, the consistency of contributions is somewhat greater in the control, which may indicate that the specific scenario or instructions led to more uniform participant behavior. The differences in the final balance reflect the cumulative effect of these contributions, providing insights into how different game scenarios influence the decision-making process regarding climate change fund contributions.

Survey Data Analysis

The survey data collected for this study primarily consisted of responses from UTSA students. The majority of participants fell within the age range of 18-34, with the highest concentration in the 25-34 age group. This demographic distribution is reflective of a university population and suggests that the results may largely represent the perspectives of young adults. The majority of participants also reported holding a bachelor's degree, while others had various levels of education, ranging from high school diplomas to master's degrees. This educational profile aligns with the typical educational background of university-affiliated participants.

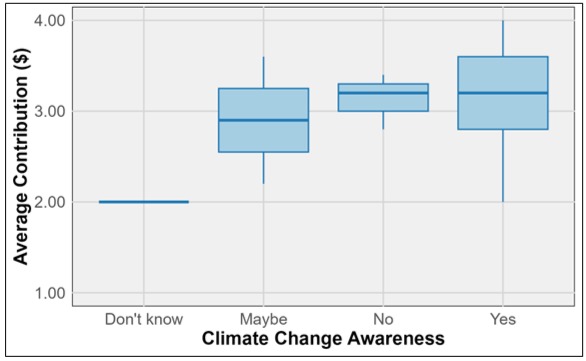

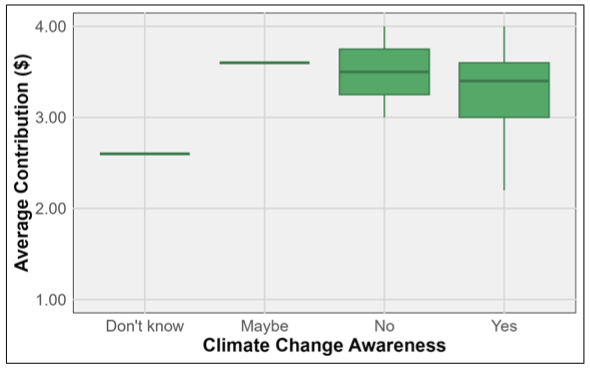

Figures 3 and 4 below display the relationship between climate change awareness and the average contribution participants made during the treatment and control conditions. Participants rated their awareness of climate change using four categories: “Don’t Know” (not aware at all), “Maybe” (uncertain awareness), “No” (aware but skeptical), and “Yes” (fully aware). The treatment condition, illustrated in Figure 3, presents contributions made after participants experienced the VR simulation focusing on storm surge impacts. The control condition, represented in Figure 4, reflects contributions after participants were shown hurricane information.

In the treatment condition (Figure 3), the average contributions appear to follow an upward trend with increased awareness of climate change. Participants who answered "Yes" to being aware of climate change contributed the highest amounts, while those who responded "No" also had relatively high contributions but with less variability. Interestingly, those who were uncertain about their awareness ("Maybe") showed a wider range of contributions but generally contributed less on average compared to the "Yes" and "No" groups. The "Don't know" group consistently contributed the least, with very little variation in their responses.

Figure 3. Participants’ Climate Change Awareness: Treatment Condition

In the control condition (Figure 4), the trend is somewhat less pronounced. Participants who responded “Yes” to being aware of climate change contributed slightly less than those who responded “No.” The "Maybe" group contributed similarly, with more consistency across their contributions. The “Don't know” group, once again, contributed the least. Overall, the control condition displays a narrower range of contributions across awareness levels compared to the treatment condition.

Figure 4. Participants’ Climate Change Awareness: Control Condition

While the data suggests a potential trend where participants with higher climate change awareness tend to contribute more, the overlap in the box plots indicates that these findings are not statistically significant. This suggests that although the VR treatment may have influenced contributions slightly, the differences across awareness levels may not be substantial enough to conclude a strong causal relationship. Future studies with larger sample sizes or more varied participant demographics may help clarify these potential trends. Nevertheless, these insights emphasize the relevance of focusing on younger populations, particularly given that most participants in this study were students.

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test

Table 2 shows Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test results, which indicate a significant difference in participant behavior in the first Round, suggesting that initial reactions or perceptions differed notably between the treatment and control conditions. However, subsequent rounds did not show statistically significant differences, reflecting a convergence in behaviors as participants progressed through the scenarios. This suggests that participants adapted their strategies over time, leading to similar overall contributions by the end of the experiment. Interestingly, there was also a trend (though not statistically significant) indicating that participants who started with the treatment might have been slightly more cautious in the subsequent rounds. These findings are crucial for understanding how initial conditions and game design influence participant behavior. The significant difference in Round 1 emphasizes the importance of initial impressions, while the lack of differences in later rounds suggests that consistent and clear instructions can mitigate initial variability, leading to comparable outcomes.

Table 2. Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test Results

The paired t-test results show that there is no statistically significant difference between the average contributions in the two game scenarios (p-value = 0.1087). Although there is a slight trend where participants who experienced the treatment scenario first seem to contribute more in the subsequent game, this difference is not statistically significant.

Tobit Regression

The Tobit regression model was used to analyze the influence of various factors on participant contribution behavior. The results in table 3 indicate that several variables significantly impact contribution levels.

Table 3. Tobit Regression Results

| Variable | Treatment | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | P-value | Estimate | P-value | |

| (Intercept) | ||||

| Age 25 - 34 | ||||

| Age 35 - 44 | ||||

| Age 44 - 54 | ||||

| Age 55 - 64 | ||||

| Gender: Men | ||||

| Education: Bachelor's Degree | ||||

| Education: Postgraduate | ||||

| Climate Awareness: Maybe | ||||

| Climate Awareness: No | ||||

| Climate Awareness: Yes | ||||

| Household Size | ||||

| Climate Importance: Not Important | ||||

| Climate Importance: Quite Important | ||||

| Climate Importance: Very Important | ||||

| Flood Insurance: No | ||||

| Flood Insurance: Yes | ||||

| logSigma | ||||

In the treatment scenario, participants aged 45 to 54 years and 55 to 64 years provide significantly lower contributions (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively), indicating that older participants tend to contribute less. For gender, men are significantly more likely to contribute higher amounts (p < 0.001). Education level also plays a role, with participants who have a bachelor’s or postgraduate degree being significantly more likely to contribute (p < 0.001 for both). The household size variable is also positively associated with contributions (p < 0.001), implying that participants from larger households contribute more. Rating climate change as important has a significant positive effect, particularly for those who rated climate importance as quite or very important (p < 0.001).

In the control scenario, participants aged 55 to 64 years also show significantly lower contributions (p < 0.01), while men are again more likely to contribute (p < 0.05). Participants with a bachelor’s degree are significantly more likely to contribute (p < 0.05), and those with flood insurance are also more likely to contribute (p < 0.05). Unlike the treatment scenario, rating climate change as important does not show significant effects, suggesting that the influence of perceived climate importance may diminish in different game contexts or due to other influencing factors. The logSigma parameter is highly significant (p < 0.001) in both scenarios, indicating that there is considerable variability in contributions that the model captures effectively. The significance of logSigma suggests that while the model explains a substantial portion of the variability in contributions, other unmeasured factors might still play a role.

These findings provide insights into how demographic factors such as age, gender, education level, household size, and perceptions of climate importance influence contribution behavior towards climate change mitigation efforts. The results emphasize the importance of targeting specific demographics, such as older individuals and those with less education, to enhance contributions in public goods game. Moreover, the differences between the treatment and control scenarios highlight how varying game contexts can alter the impact of these factors, suggesting that the framing and sequence of scenarios can influence participant behavior.

Discussion

The findings of this study provide several important insights into how VR simulations and demographic factors influence public perceptions and behaviors related to climate change. However, contrary to our initial expectations, participants in the control group—who experienced the static informational scenario in VR—contributed more consistently and in higher amounts than those in the treatment group exposed to the dynamic flood simulation. This suggests that while immersive VR experiences may have a role in engagement, clear and structured information, as presented in the control condition, may more effectively encourage participants to contribute toward climate change mitigation efforts.

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test highlighted an initial significant difference in contributions between the control and treatment groups in the first Round, with participants exposed to control (informational content) contributing higher amounts. This initial exposure appears to have had a stronger influence on participant behavior compared to the treatment (VR simulation). However, as the game progressed, participant behavior converged, and no significant differences were observed in the later rounds, suggesting that participants adapted their strategies once familiar with the game's structure.

The Tobit regression analysis further revealed that participants with higher education levels were more likely to contribute larger amounts in both the treatment and control conditions. However, this should not be interpreted as a direct endorsement of educational interventions alone as being effective. Rather, it highlights the importance of considering demographic factors, such as education, in designing communication strategies for climate change. Additionally, participants aged 45-64 tended to contribute less, which indicates the need for age-specific communication approaches.

These findings demonstrate that both immersive VR and informational content have a role in climate change education. While VR can be effective for engagement, structured information, as shown in the control condition, is particularly impactful for immediate contributions to climate resilience. Future research should continue exploring the complex interactions between demographic factors, VR experiences, and climate perceptions to develop targeted and effective communication strategies.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice or Policy

Firstly, the results show that participants with higher education levels contributed more to climate change mitigation. This indicates that individuals with more education may be more aware of climate issues and more willing to take action. However, it is essential that climate education initiatives do not exclusively focus on those who are already predisposed to engage. Instead, policymakers should develop more inclusive educational strategies that target a wider range of demographics, to foster a broader engagement with climate issues. Secondly, the observed success of informational content (control group) over immersive VR experiences (treatment group) in driving consistent and higher contributions suggests a practical approach to public engagement. This indicates that clear, structured informational content—especially when combined with impactful visuals—is effective in conveying the urgency of climate change. Therefore, environmental organizations and government campaigns should focus on well-designed infographics, informative videos, and structured messages to raise awareness and encourage climate-friendly behaviors among the public.

Lastly, the study indicates a need for age-specific communication strategies. Older participants, particularly those between 45 and 64 years of age, tended to contribute less, implying that this demographic may have different motivators and concerns regarding climate action. Tailoring campaigns to address these unique factors could be instrumental in increasing engagement across all age groups, ensuring that older populations are not left behind in climate resilience efforts.

Limitations

Despite the insightful findings of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged that affect the interpretation and generalizability of the results. First, the study design involved different participants for each scenario before ID 13, with odd-numbered IDs participating in the treatment scenario and even-numbered IDs in the control, followed by all participants experiencing both scenarios in alternating order from ID 13 onwards. While this approach controlled for order effects, the initial split in participant groups introduced variability that affects data comparability. Future experiments will ensure all participants experience both scenarios, with the sequence randomized to allow a more detailed analysis of order effects.

The sample size of 45 participants, primarily UTSA students, also limits generalizability due to homogeneity in age and education level. A broader participant pool is needed in future research to enhance external validity. Additionally, most experiments were conducted in a controlled office environment or the VizLab at UTSA, which may not fully reflect real-world variability. Future studies should include more naturalistic settings, such as community spaces, to better assess the effectiveness of VR interventions.

Potential biases, such as the Hawthorne effect and the reliance on self-reported data, also pose limitations. Future research will employ methods to mitigate these biases, such as unobtrusive measures and mixed-methods approaches, providing a more comprehensive understanding of participant behaviors and perceptions.

Dissemination and Community Engagement

We presented a poster at the Natural Hazards Workshop held from July 14 to July 17, 2024. The Workshop allowed us to share our findings with federal, state, and local mitigation officials, as well as planning professionals and researchers dedicated to alleviating the impacts of disasters. This provided an opportunity to engage with key stakeholders in the hazards and disaster research community. We also participated in the Alamo Area GIS User Group (AAGIS) event held on September 26, 2024, where we set up a booth to promote our research. This event, held in San Antonio, provided an opportunity to present our work to local GIS professionals, including showcasing our VR equipment and the climate change simulation game. We distributed informational flyers and engaged in discussions to raise awareness of the study and foster collaborations on GIS-related climate initiatives.

Lastly, we conducted campus outreach activities on the UTSA campus to engage students and faculty, raising awareness about climate change risks and the role of immersive technologies in enhancing public understanding of these issues.

Future Research Directions

Future research will focus on addressing the limitations identified in this study and exploring new directions. To reduce variability from participant group splits, future studies will ensure all participants experience both scenarios, with sequences randomized. The participant pool will be expanded to include more diverse demographics, making findings more generalizable. Data collection will be conducted in naturalistic settings, like public parks, to assess the effectiveness of VR and informational content in real-world environments. To minimize biases, future studies will incorporate unobtrusive methods and follow-up assessments to validate findings.

Additionally, new research will explore optimizing VR immersion for greater emotional engagement and collaboration with practitioners to create VR-based educational tools for different community settings. We recommend future studies examine the interaction between immersive content and demographic diversity to develop effective climate change communication strategies for varied populations.

References

-

Baumgartner, F. R., Breunig, C., Green-Pedersen, C., Jones, B. D., Mortensen, P. B., Nuytemans, M., & Walgrave, S. (2009). Punctuated equilibrium in comparative perspective. American Journal of Political Science, 53(3), 603-620. ↩

-

Chan, F. K. S., Chuah, C. J., Ziegler, A. D., Dabrowski, M., & Varis, O. (2018). Toward resilient flood risk management for Asian coastal cities: Lessons learned from Hong Kong and Singapore. Journal of Cleaner Production, 187, 576-589. ↩

-

Mendelsohn, R., Emanuel, K., Chonabayashi, S., & Bakkensen, L. (2012). The impact of climate change on global tropical cyclone damage. Nature Climate Change, 2, 205-209. ↩

-

Warner, N. N., & Tissot, P. E. (2012). Storm flooding sensitivity to sea level rise for Galveston Bay, Texas. Ocean Engineering, 44, 23-32. ↩

-

Bowman, D. A., & McMahan, R. P. (2007). Virtual reality: how much immersion is enough?. Computer, 40(7), 36-43. ↩

-

Jensen, L., & Konradsen, F. (2018). A review of the use of virtual reality head-mounted displays in education and training. Education and Information Technologies, 23, 1515-1529. ↩

-

Freina, L., & Ott, M. (2015, April). A literature review on immersive virtual reality in education: State of the art and perspectives. In The international scientific conference e-learning and software for education (Vol. 1, No. 133, pp. 10–1007). ↩

-

Slater, M., & Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2016). Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 3, Article 74. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2016.00074 ↩

-

Gneezy, U., & Imas, A. (2017). Lab in the field: Measuring preferences in the wild. In A. V. Banerjee & E. Duflo (Eds.), Handbook of economic field experiments (Vol. 1, pp. 439–464). North-Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.hefe.2016.08.003 ↩

-

D'Amico, A., Bernardini, G., Lovreglio, R., & Quagliarini, E. (2023). A non-immersive virtual reality serious game application for flood safety training. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 96, Article 103940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103940 ↩

-

Calil, J., Fauville, G., Queiroz, A. C. M., Leo, K. L., Mann, A. G. N., Wise-West, T., Salvatore, P., & Bailenson, J. N. (2021). Using Virtual Reality in Sea Level Rise Planning and Community Engagement—An Overview. Water, 13(9), Article 1142. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13091142 ↩

-

Fauville, G., Queiroz, A. C. M., & Bailenson, J. N. (2020). Virtual reality as a promising tool to promote climate change awareness. In Technology and Health (pp. 91–108). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816958-2.00005-8 ↩

-

Mol, J. M., Botzen, W. W., & Blasch, J. E. (2022). After the virtual flood: Risk perceptions and flood preparedness after virtual reality risk communication. Judgment and Decision Making, 17(1), 189-214. ↩

-

Mikropoulos, T. A., & Natsis, A. (2011). Educational virtual environments: A ten-year review of empirical research (1999–2009). Computers & Education, 56(3), 769-780. ↩

-

Larcom, S., She, P. W., & Van Gevelt, T. (2019). The UK summer heatwave of 2018 and public concern over energy security. Nature Climate Change, 9, 370-373. ↩

-

Van Gevelt, T., Abok, H., Bennett, M. M., Fam, S. D., George, F., Kulathuramaiyer, N., Low, C. T., & Zaman, T. (2019). Indigenous perceptions of climate anomalies in Malaysian Borneo. Global Environmental Change, 58, Article 101974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101974 ↩

-

Konisky, D. M., Hughes, L., & Kaylor, C. H. (2016). Extreme weather events and climate change concern. Climatic Change, 134, 533-547. ↩

-

Carmichael, J. T., & Brulle, R. J. (2017). Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: An integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001-2013. Environmental Politics, 26, 232-252. ↩

-

Mildenberger, M., & Leiserowitz, A. (2017). Public opinion on climate change: Is there an economy-environment tradeoff? Environmental Politics, 26(5), 801-824. ↩

-

McDonald, R. I., Chai, H. Y., & Newell, B. R. (2015). Personal experience and the ‘psychological distance’ of climate change: An integrative review. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 44, 109-118. ↩

-

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E. W., & Roser‑Renouf, C. (2009). Climate change in the American mind: Americans’ climate change beliefs, attitudes, policy preferences, and actions. Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2667029 ↩

-

Simpson, M., Padilla, L., Keller, K., & Klippel, A. (2022). Immersive storm surge flooding: Scale and risk perception in virtual reality. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 80, Article 101764. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101764 ↩

-

Howe, P. D., Marlon, J. R., Mildenberger, M., & Shield, B. S. (2019). How will climate change shape climate opinion? Environmental Research Letters, 14(11), Article 113001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab466a ↩

-

Fan, X., Jiang, X., & Deng, N. (2022). Immersive technology: A meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tourism Management, 91, Article 104534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104534 ↩

-

Peeters, D. (2018). A standardized set of 3-D objects for virtual reality research and applications. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 1047-1054. ↩

-

Newman, M. A. R. K., Gatersleben, B., Wyles, K. J., & Ratcliffe, E. (2022). The use of virtual reality in environment experiences and the importance of realism. Journal of environmental psychology, 79, Article 101733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101733 ↩

-

Queiroz, A. C., Fauville, G., Abeles, A. T., Levett, A., & Bailenson, J. N. (2023). The efficacy of virtual reality in climate change education increases with amount of body movement and message specificity. Sustainability, 15(7), Article 5814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075814 ↩

-

Ashley, R., Ball, S., & Eckel, C. (2010). Motives for giving: A reanalysis of two classic public goods experiments. Southern Economic Journal, 77(1), 15-26. ↩

Zhai, W., Giacomoni, M., Qin, H., & Huang, H. (2025). Do Virtual Reality Hazard Simulations Increase People’s Willingness to Contribute to Hazard Mitigation? Results From An Experiment. (Natural Hazards Center Weather Ready Research Report Series, Report 18). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/do-virtual-reality-hazard-simulations-increase-peoples-willingness-to-contribute-to-hazard-mitigation