Sharing During Disasters

Learning From Islands Preliminary Findings and Initial Implications for Action

Publication Date: 2021

Executive Summary

Overview

Sharing during disasters is an important form of prosocial behavior in isolated island communities with limited opportunity for mutual aid and outside assistance. Due to geographic isolation, islands are disproportionately exposed to hazards, threats, and risks and must develop approaches to cope with disasters with the lack of mutual aid from neighboring jurisdictions. This study examines the sharing behaviors in island communities and offers lessons on prosocial behaviors during disasters.

Research Design

We gathered empirical evidence using a quantitative and qualitative research design. Based on a questionnaire survey administered to residents of American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CMNI), Guam, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), and Hawaii, information on sharing behaviors during disasters were gathered and analyzed. The survey contained demographic questions and focused on the perceptions, practices, and experiences of islanders with respect to sharing during disasters. Basic descriptive and inferential statistics and several nonparametric (chi-square) and regression models (OLS and Logit) were run using the SAS statistical analysis software. Based on survey findings, two focus group meetings were organized to collect additional information on sharing behaviors in these islands. Transcripts from meetings and open-ended responses of the survey were analyzed and coded NVivo, Version 12 software which revealed common themes of community, culture, family, neighbors, and the importance of identity in sharing behaviors.

Research Questions

The research questions were: 1) How do disaster-prone, isolated communities share resources during disasters? 2) What are the challenges and opportunities for resource sharing in these communities? and 3) How can formal and informal disaster response mechanisms work together to improve community resilience?

Implications and Conclusions

Our analyses showed that while sharing is a widely accepted practice, there are differences based on respondent characteristics, cultural norms, institutions, and the size of the disasters in each of the communities. The study showed that there are many different barriers to sharing, which provide clues and directions for increasing prosocial behaviors during disasters. There also was strong support for training and education to overcome these barriers.

Introduction and Literature Review

Sharing during disasters is an important form of prosocial behavior (Tierney, 20141) which is especially needed in isolated island communities with limited opportunities for mutual aid and outside assistance. Prosocial behaviors are actions that help or benefit other members of society (Penner et al., 20052) which may be motivated by altruism or reciprocity and emerge during disasters that strain access to vital goods and services (Rodriguez et al., 20063). For this study, sharing is defined as the voluntary exchange of goods and services between people who are not family members or friends. Research on this topic is limited, especially in island settings.

Islands are special places with opportunities for and challenges building community resilience (Kim & Freitas, 20184). They are disproportionately exposed to hazards, threats, and risks (Kelman & West, 20095), including isolation, and have developed approaches for coping with and managing disasters in the absence of mutual aid from adjacent jurisdictions (Barmejo, 20066; Kim & Bui, 20197). There are valuable lessons from islanders on sustainability and resilience (Becker & Legg, 20128). The COVID-19 pandemic has generated unusual challenges and opportunities for learning about resilience from island communities (Kim, 20209; Edwards, 202010). Given the changing context and dire consequences of hazards and threats due to climate change and other stressors (Cutter, 201611; Kelman & West, 2009), there is a need to better understand and disseminate the "shared agency of acting together" (Bratman, 201512), not just for islands but in other communities concerned with safety, security, and resilience. The motivation for our research arises from a knowledge to action understanding of planning (Friedmann, 198713) with an appreciation of long-standing tensions between theory and practice (Forester, 201914).

The research builds on prior research on social capital, networks, and behaviors during disasters (Aldrich, 201215; Kawamoto & Kim, 201616; Sadri et al., 201817). It also extends understanding of local and indigenous knowledge and customary roles in disaster risk reduction and resilience (Kravel, 201918; Rumbach & Foley, 201419). Social cohesion supports community functioning and resilience (Links et al., 201820). While the importance of social relationships has been recognized in approaches such as the Communities Advancing Resilience Toolkit (Pfefferbaum et al., 201321), further research on sharing behaviors during disasters is needed. While there are larger forces associated with globalization, urbanization, and technological change affecting communications, information sharing, and the movements of goods and services across the planet, islands provide a unique window into local places and processes (Keil et al., 199622; Kim & Freitas, 2018; Lippard, 199723).

The findings are based on a survey and focus group discussions with residents in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), Guam, American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), and Hawaii. Sharing behaviors during 40 different natural and human-caused disasters, including hurricanes, tsunamis, flooding, earthquakes, and the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the background characteristics of respondents, are analyzed. The study also examines barriers to sharing and solutions for increasing sharing during disasters.

Methods

The research is based on a questionnaire administered during the Spring of 2021 to residents of American Samoa, CNMI, Guam, Puerto Rico, and USVI. Virtual focus group meetings were organized on June 1 (American Samoa, Guam, and CNMI) and June 25 (Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands) to discuss survey findings and collect additional data on sharing practices during disasters. The findings were widely shared with researchers and practitioners. The questionnaire was also administered to people in Hawaii who face similar challenges of isolation and remote location. It provides a pathway for translating the results and findings into actions supporting resilience to other island communities.

The survey instrument was pre-tested with students and staff at the University of Hawaii. The questions were revised based on feedback. The instrument, sampling plan, and protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Hawaii Human Studies Program, Office of Research Compliance (Protocol # 2021-00193) on March 11, 2021. The researchers have maintained certifications and have received updated training on data governance and human subjects as required by the university.

The responses were collected with the Qualtrics online survey platform, with separate URLs for each of the six island communities. The survey was widely distributed through email contacts with key informants and organizations and circulated through social media, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and other platforms. The URLs were sent to over 10,000 participants, Subject Matter Experts (SMEs), and delivery partners of the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center (NDPTC). They were asked to distribute the instrument in their local networks. A total of 285 valid responses were received. The data were loaded into Statistical Analysis System (SAS) for tabulation and analysis.

There were 18 questions on the survey, which took approximately 15 minutes to complete. The survey instrument focused on the perceptions, practices, and experiences of islanders with respect to sharing during disasters. It asked respondents to provide examples of sharing and had questions about demographic characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, and occupation. Respondents identified and enumerated the goods and services that were shared. A variable called the Propensity to Share (PtS) based on the number of items shared was derived.

Two focus group discussions focused on the methods and findings, how to improve prosocial and sharing behaviors during disasters, and approaches to training and capacity building. Both meetings were organized in the same format. With the consent of the participants, both meetings were recorded. The discussions from both focus group meetings were transcribed and coded using NVivo 12 to draw conclusions.

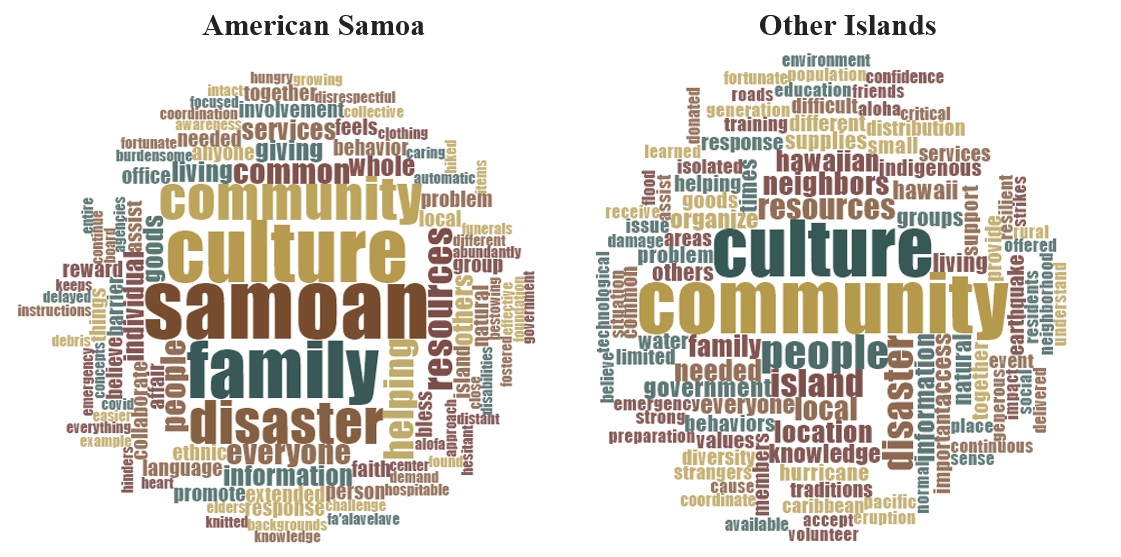

In addition to basic descriptive and inferential statistics, several nonparametric (chi-square) and regression models were run. The survey included an open-ended question asking how culture, location, and indigenous knowledge affect sharing practices and behaviors. A total of 83 respondents responded to the question. Responses were imported into NVivo 12 and organized by five study areas—American Samoa, Guam and CNMI, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and USVI. Responses from Guam and CNMI were grouped together due to their geographic proximity and low response rates. Word frequencies were generated for the 500 most frequently used words, including stemmed words, with a minimum length of five characters. The 500 most frequently used words were used to generate word clouds. The size of the word in the cloud represents the frequency of use.

Findings

Survey Results

The demographic characteristics of the 285 respondents are contained in Table 1, “Background Characteristics of Respondents and Propensity to Share (PtS).” The mean age of the respondents was 52.53 years, with 57.64% female respondents and 42.36% male respondents. The most commonly reported ethnicity was Hispanic/Latino (29.18%), followed by Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (24.46%), Caucasian (19.31%), Asian (13.73%), African American (7.73%), and Other (5.58%). A wide range of occupations was reported, including government (33.48%), education (22.03%), nonprofits (10.13%), fire and law enforcement (5.29%), disaster management (3.08%), medical and health care (3.96%), construction and transportation (2.20%), self-employed (5.29%) and retired (12.78%). The largest number of responses were from Puerto Rico (88), followed by Hawaii (81), American Samoa (43), USVI (43), and Guam and CNMI (34). Compared to the overall populations, the sample is biased towards older adults, females, those with higher education, and those working in the public sector.

Table 1 contains frequencies and percentages by demographic groupings for the PtS, which was derived by tabulating the number of items shared with strangers from a list of goods and services by the number of people in each category. Demographic categories are not consistent with other studies due to unique demographic compositions among island communities. The PtS value ranges from 0 to 9, with a mean of 5.65, a median of 6, and a standard deviation of 2.42. Those younger than 30 had the highest mean PtS score (6.33), followed by those in the 41–50 age category (6.07). Females were more likely to share, with a PtS score of 5.94 compared to males (5.65). The highest PtS scores were for Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders (6.26), followed by Others (6.15), Caucasians (6.02), African Americans (5.83), and Asians (4.84). The PtS variable ranged from a low of 3.67 for those in medical and health care occupations to a high of 8.80 for those in the construction and transportation industry, followed by emergency managers and responders at 7.57. The highest PtS values were for American Samoa (6.26), with the lowest value in Puerto Rico (5.25) with CNMI and Guam (6.03), USVI (5.46), and Hawaii (5.32), falling in between. CNMI and Guam were grouped together due to low response rates and their geographic proximity.

Table 2, “Sharing of Goods and Services During Disasters,” contains data on what goods and services were shared with strangers during disasters, what was “most important” (in terms of sharing), and what was the “most difficult” to share. Approximately 87% of respondents reported sharing food, 78.6% reported sharing water, and 64.6% reported sharing shelter or housing. These were also ranked highest in terms of most important to share: water (29.04%), food (24.63%), and shelter/housing (15.81%). The least important items for sharing among these respondents were vehicles (0.37%) and clothing (1.10%). The highest-ranking categories, in terms of the percentage of respondents identifying the most difficult good or service to share, were: shelter/housing (22.85%), money (22.47%), water (11.24%), and services (10.86%). However, information (9.36%) and other items (8.99%) were also difficult items to share. Other items that respondents mentioned as most important to share were medication, energy, household items (flour, paper towels, and disinfectant wipes), personal hygiene supplies, masks, and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Respondents entered them under other items that were shared during disasters and were not listed in response options.

Table 3, “Barriers to Sharing,” shows that inadequate supply (49.12%), delivery problems (45.3%), communications and coordination (45.96%), and health and safety concerns (35.09%) were the main barriers. Other barriers included concerns over liability and legal matters (18%), unwillingness to share (11%), and ethnic or religious differences (6.32%). Also mentioned were the existing institutional setup for sharing, the mismatch between demand and supply, no power source, and hoarding behaviors.

Table 4, “Strategies for Overcoming Barriers to Sharing,” shows that training and education were identified as the strategy endorsed by 56.49% of respondents while improving social relations was supported by 44.91% of those participating in the survey. Training and education was the most-supported strategy of the four listed to overcome the barriers to sharing. Setting systems for accounting and recording of sharing and developing mechanisms for payback and reciprocity were supported by 23.86% and 23.16%, respectively, of all respondents. Other strategies were identified by 29.12% of respondents. Respondents were allowed to report other strategies for overcoming the barriers to sharing. The strategies mentioned were communication and coordination, pre-disaster planning, stockpiling, better distribution systems including distribution hubs, the outreach of sharing and reciprocity, and recruiting and mobilizing volunteers.

Table 5, “Ranking of Strategies to Overcome Barriers,” contains a comparison of different strategies, including creating an electronic bulletin board; use existing platforms; have government agencies establish platforms; and encourage non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to develop sharing systems, which are categorized as “best,” “good,” “neither good nor bad,” “bad,” and “worst.”. Respondents could rank each strategy on a scale of best to worst, and they were allowed to rank multiple strategies as the best or worst. The “best” strategy supported by most respondents (49.80%) was to have government agencies establish platforms activated during disasters. Encouraging nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and NGOs to be more involved with sharing platforms was a close second, with 45.20% of all respondents signifying that this was the “best” strategy. The creation of electronic bulletin boards (51.42%) and using or modifying existing platforms (46.53%) were identified as “good” strategies. These two strategies were also identified by some respondents as “bad” or “worst” (12.95% for bulletin board and 10.21% for using/modifying existing platforms). This data reveals stronger support for the government and nonprofit/faith-based organizations and NGOs in facilitating sharing among strangers during disasters.

Table 6, “Disasters with Reported Sharing of Goods and Services,” contains the types of disasters identified by respondents. The disaster most cited was Hurricane Maria, identified by 35.8% of respondents, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic (10.76%), Hurricane Irma (7.99%), Typhoon Yutu (6.60%), 2009 American Samoa Tsunami (6.25%), Cyclone Gita (4.86%), and Hurricane Iniki in 1992 (3.82%). Other disasters identified by respondents include the 2020 earthquake in Puerto Rico, the 2018 volcanic eruption in Hawaii, and other flooding events. Respondents identified the 9/11 terrorist attack and other disasters as well.

Using data from the survey, a multiple regression model of the Propensity to Share (PtS) on demographic characteristics of respondents was run (Table 7). While the model is significant (probability (pr) = 0.0022), with an r-square of approximately 12%, most of the terms were not significant at the 0.05 level. A negative binomial regression model was also estimated, yielding similar results without increasing overall explanatory power. Based on the model, there are interesting results. Compared to all other disasters, Hurricane Maria and the COVID-19 pandemic stood out with statistically significant negative coefficients showing reduced sharing behaviors during these disasters. With COVID-19, the negative value makes sense because of social distancing orders and discouragement of sharing food and goods that could transmit the disease. Perhaps because of the extent and shortages associated with Hurricane Maria, there may have been fewer resources and opportunities for sharing than with other disasters. Focus group participants from Puerto Rico described the long duration and widespread shortages during Maria, which limited sharing of goods and services.

To better isolate the specific sharing behaviors, sharing of homes/shelters was more closely examined. Compared to sharing goods, information, or other services, the willingness of residents to share their homes and shelter spaces is particularly important given the earlier reported finding that sharing housing/shelter was both important and the most difficult to share. A chi-square analysis was performed to compare home/shelter sharers to home/shelter non-sharers (Table 8). Due to small cell sizes, most of the tests were not significant at the 0.05 level. Geographic area (American Samoa) was strongly associated with sharing, with 39 respondents reporting home/shelter sharing and four reporting not sharing home/shelter (chi-square = 14.783; pr < 0.0001). The COVID-19 pandemic was strongly associated with not sharing homes/shelters compared to other disasters (chi-square = 27.103, pr< 0.0001).

Table 9 shows the results of a logit model to estimate the odds of being a home/shelter sharer over not sharing a home/shelter during a disaster. COVID-19 (pr< 0.0005) and American Samoa (pr < 0.0156) were both significant. Based on the odds ratios, respondents were 0.18 times more likely to not share homes/shelters during COVID-19 than other disasters, and respondents from American Samoa were 32.79 times more likely to share homes/shelters than respondents from other islands. While other terms were not statistically significant, the direction of the coefficients and the size of effects were nonetheless interesting. The groups with the highest odds ratio (OR) on home/shelter sharing include those in the 30–40-year age group (OR= 2.17); males were less likely than females to share (OR=0.25); and respondents were more likely to share during hurricanes compared to all other types of disasters (OR=1.43) except for Hurricane Maria (OR=0.66). Those in government and white-collar jobs (banking, finance, medical/healthcare, and teaching) were less likely than blue-collar (transportation, restaurant, retail, military, utilities, construction, grocery, and fire and law enforcement) workers to share home/shelter, as were respondents from Puerto Rico, USVI, and respondents of Asian, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander backgrounds (as indicated by the odds ratios below). Odds ratios close to one indicate no effect. Caution in interpretation is encouraged because of the small cell sizes and lack of statistical significance.

Figure 1 and Table 10 show the differences in perception of the roles of culture, location, and indigenous knowledge on sharing behavior. American Samoa is different than other islands. The words “Samoan,” “Culture,” and “Family” were the three most frequently used in responses from American Samoa. For other islands, “Community,” “Culture,” and “People” were the most frequently used three terms to explain the roles of culture, location, and indigenous knowledge on sharing behavior.

Figure 1. Word Clouds of 500 Most Frequently Used Words - Role of Culture, Location, and Indigenous Knowledge on Sharing Behaviors (American Samoa and Other Islands)

Insights from Focus Group Meetings

Research methods and survey findings were discussed during two focus group sessions in June. Additional comments and explanations of findings were provided. Participants from American Samoa explained how sharing homes and shelters is a common practice. One informant reported that:

The research hit on the dot about American Samoa and sharing because we have our main house, and we have our family house, the extended traditional home. During the disaster, the extended family house is open to anyone who needs shelter, within the family or another family for that matter.

Focus group participants also raised the practices of interisland sharing during disasters. An informant from USVI described how their community received tremendous support and donation of goods from Puerto Rico when Hurricane Irma hit their island in 2017, and then two weeks later, Maria struck Puerto Rico before it could replenish its own supplies. An informant from CNMI also reported receiving goods and services from other islands. He reported:

When a small island like Saipan gets struck heavily by Category 4 typhoon, hands are really limited, so we are just isolated in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. We had assistance from the neighboring islands. They were bringing in a lot of goods and equipment, particularly from Guam and American Samoa and Palau.

Participants from both focus groups mentioned that the scarcity of resources is an impediment to sharing during disasters. Informants from the USVI and Puerto Rico mentioned that residents did not have cash, gas, and other essential goods after [Hurricanes] Irma and Maria. Communication systems were down. As a result, they did not know where to get food and services. It was challenging for residents to fulfill basic needs for their families, which resulted in less sharing of goods and services with other people. As an informant from Puerto Rico explained:

Hurricane Maria was a mega disaster. We did not have access to money, we did not get to the bank. All the banks were limiting the quantity of money you can get from your account on a daily basis. If you wanted to get gas, there were eight to nine hours of waiting in line… people did not have communications. People did not know when they would have services or food or other services on the island. That could be one of the reasons for less sharing behavior during these disasters.

Meeting participants also commented on higher dependence on government and eroding community values of sharing over time. They said that people, these days, tend to look for government support after a disaster rather than helping each other. An informant from the USVI stated:

I have noticed changes in the sharing behaviors. After Hurricane[s] Hugo and Marilyn, the people of the U.S. Virgin Islands were exemplary as to their willingness to share. By the time we got to [Hurricanes] Irma and Maria, we see the change in that greatly. One of the factors may be the personality of the younger groups influence on the tendency of sharing, and society also relies on outside help. We used to help each other when we think anybody will not help us. Now, everybody waits for FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency]. Now, everybody has alternatives.

Discussion of Findings

The analysis of survey data and focus group transcripts shows that while sharing is a widely accepted practice, there are differences based on respondent characteristics, cultural norms, institutions, and the size of the disasters in each of the communities. While the research is limited by the nature of electronic surveys and small focus groups, as well as by biases in terms of response and challenges with interpreting and extracting meaning, there are several key findings to reiterate.

First, there is widespread acknowledgment of the importance of sharing and the need to better understand and improve sharing during disasters. More than half of survey respondents mentioned sharing food, water, shelter, equipment, clothing, information, and services during disasters. Respondents pointed out inadequate supply, resource delivery, poor coordination, and health and safety concerns as barriers to sharing resources during disasters. These barriers arise from the governance, institutions, and administrative structures within the community. There is a need to better understand existing preparedness and response mechanisms within communities.

Second, the respondents identified many different barriers to sharing, which provide clues and directions for action and increased prosocial behaviors. Some of the barriers were related to the availability of goods and services and also to the mechanisms for delivery during disasters. Nearly 18% of respondents reported “concerns over liabilities and legal matters,” and 35% stated that “health and safety requirements” were barriers to sharing. While only 6.32% said “ethnic or religious differences,” with almost 11% reported “unwillingness to share resources,” a large proportion of respondents (45.96%) reported “poor communications” as barriers to sharing.

Third, there is strong support (over 56%) for training and education to overcome barriers to sharing. Also, approximately 45% reported “improving social relations” as a needed strategy to increase sharing. Nearly a quarter of respondents supported more “accounting and recording of sharing behaviors” and “developing mechanisms for payback and reciprocity” as strategies to support overcoming barriers.

Fourth, there are differences between communities and differences between cultural and social groupings (age, gender, ethnicity, occupation, etc.). Some of these differences affect both the capacity and availability of sharable goods and services. In contrast, others pertain more to the behaviors, practices, motivations, priorities, and understanding of sharing beyond family and friends. More detailed assessment and disentanglement of the contributing social, cultural, and pragmatic considerations of sharing during disasters, especially among strangers, is needed.

Fifth, there are differences between communities. While some common themes across all island communities have emerged, the sharing behaviors were most strongly observed in American Samoa. Figure 1 shows the word clouds for all island communities and a separate one for American Samoa. It is clear that while there are common words such as community, culture, people, family, and island, they are strong descriptors. In American Samoa, Samoan culture and family are dominant words. It is necessary to further investigate how these words and meanings are translated into actions and institutions, and practices to support sharing behaviors.

Sixth, there are differences between disasters. Some events, such as Hurricane Maria, covered such a large area, crippling infrastructure, and services for such a long duration of time that resource constraints were quite severe. There is a strong, statistically significant difference between sharing behaviors during the pandemic compared to all other disasters. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was less reported sharing of goods and services than during other hazards and disasters.

Seventh, the research using both Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression on the PtS variable and the logit model investigating home/shelter sharers shows the complexities of the interactions between demographic factors, island or territorial characteristics, disaster types, and sharing behaviors. While there was a deeper understanding of data and modeling issues, additional cases and increased responses would have helped increase statistical power and significance levels. There are also concerns about biases associated with the sampling and representativeness of electronic questionnaires. A mixed-methods approach is clearly needed, with discussion, critique, and further analysis of the quantitative data assembled in this analysis.

Finally, the methods, data, and analyses related to the original question as to “knowledge to action.” The findings widen the understanding of sharing behaviors and the many actors at different scales (individual, family, neighborhood, island, and beyond) that support sharing during disasters. There are complexities, intervening factors, circumstances, and challenges of transferring ideas and systems across diverse island communities. The results show support for more government, formal action, increased coordination, communications, and convergence between faith-based community groups and NGOs.

Conclusion

Key Findings

Sharing among strangers is an important behavior during disasters, especially in remote island territories and jurisdictions. There are commonalities across the six jurisdictions studied, including the importance of community and collective identities and actions. There are differences between disasters, places, and motivations for sharing. The next stage of the research—further analysis of survey data and additional focus group discussions in each of the island and other remote communities—will support deeper understanding and policy and plan development.

Implications for Practice

In addition to improved communications and coordination for sharing during disasters, there is also reason to focus on the sharing behaviors of key demographic groups in key places and times—such as in American Samoa or during events where sharing behaviors were strongest—to better distill and understand the mechanisms and reinforcement of prosocial sharing among strangers. The survey found strong support for increased training and education and improved social relations as pathways for overcoming barriers. Training and education programs should target community-based organizations, self-help groups, faith-based organizations, local clubs, user groups, schools, and community leaders. They are key agents who can promote resource sharing in communities. Training program content should focus on sharing culture, resource sharing to support preparedness and response, challenges to sharing during disasters, overcoming barriers, and successful case studies of prosocial sharing behaviors during disasters.

Dissemination

A report of findings was sent to all respondents who provided contact information. The focus group meetings also provided opportunities for further dissemination and return of research results to island communities. The findings and results will be presented more widely in national and island venues.

Limitations

There are limitations when conducting research remotely during a pandemic without in-person interviews and the ability to reach low-income, minority, and other disadvantaged groups. It is difficult to estimate the response rate because the survey was distributed through social media as well as by email to over 10,000 individuals. Based on the estimated count of email addresses, the overall response rate of the survey was 3%. American Samoa and U.S. Virgin Islands had the highest and lowest response rates at 9% and 1%, respectively. Another limitation was that the survey was administered only in the English language, which may also have limited participation and increased biases. The statistical analyses, including the development and testing of the regression, logit, and negative binomial models, needed additional cases to increase power and statistical significance. Participation in the focus groups was limited because of the reliance on virtual platforms rather than in-person meetings. The focus group for Puerto Rico occurred on a day following several earthquakes, which may have disrupted communications.

Future Research

While Hawaii was included as a reference community, further research will involve collection, analysis, and comparison of data from tribal and other remote continental communities to better explore the differences between urban and rural contexts and to better understand the processes, institutions, and systems for improving sharing during disasters. Further attention to the development of training and educational programs to support sharing among strangers during disasters will be part of ongoing extensions of the work described in this report. Team members express gratitude to the Natural Hazards Center and the many informants and participants who have supported this initial effort.

Further contemplation of the agency of collective actions and deeper analysis of the differences between bonding, bridging, and linking forms of social capital, as well as the potential for systemic racism (Feagin & Bennefield, 201424) and discrimination in sharing economies (Edelman et al., 201725) and ways that race, ethnicity, and disaster intersect (Fothergill et al., 199926), are all part of unfinished work.

References

-

Tierney, K. (2014).The social roots of risk: Producing disasters, promoting resilience. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Business Books. ISBN: 978-0-8047-7263-1. ↩

-

Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., & Schroeder, D. A. (2005). Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 365–392. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070141. ↩

-

Rodriguez, H., Trainor, J., & Quarantelli, E. (2006). Rising to the challenges of a catastrophe: The emergent and prosocial behavior following Hurricane Katrina. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 604(1), 82–101. https://doi-org.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/10.1177/0002716205284677. ↩

-

Kim, K. & Freitas, K. (2018). The Resilience of islands: Borders and boundaries of risk reduction. In M. A. Miller, M. Douglass, & M. Garschagen (Eds.) Crossing Borders: Governing Environmental Disasters in a Global Age in Asia and the Pacific (Chapter 9, pp. 155–174). New York: Springer. ISBN: 978-981-10-6126-4. ↩

-

Kelman, I. & West, J. (2009). Climate change and small island developing states: A critical review. Ecological and Environmental Anthropology, 5(1), 1–16. ↩

-

Barmejo, P. (2006). Preparation and response in case of natural disasters: Cuban programs and experience. Journal of Public Health Policy, 27(1), 13–21. www.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200056. ↩

-

Kim, K. & Bui, L. (2019). Lessons from Hurricane Maria: Island ports and supply chain resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 39, 101244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101244. ↩

-

Becker, C., & Legg, Y. (2012). Small island states in the Pacific: The tyranny of distance (IMF Working Paper No. 12/223). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Small-Island-States-in-the-Pacific-the-Tyranny-of-Distance-26253. ↩

-

Kim, K. (2020, March 4). Hawaii's coronavirus plan must address unusual challenges. Civil Beat. Downloaded May 5, 2021 from: https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/03/hawaiis-coronavirus-plan-must-address-unusual-challenges/ ↩

-

Edwards, R. (2020). Bubble in, bubble out: Lessons for the COVID-19 recovery and future crises from the Pacific. World Development, 135, 105072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105072. ↩

-

Cutter, S. L. (2016). The changing context of hazard extremes: Events, impacts and consequences. Journal of Extreme Events, 3(2), 1671005. https://doi-org.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/10.1142/S2345737616710056. ↩

-

Bratman, M. (2015). Shared Agency: A planning theory of acting together. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal in the Analytic Tradition, 172(12), 3375–3378. www.doi.org/10.1093/analys/anu155. ↩

-

Friedmann, J. (1987). Planning in the public domain: From knowledge to action. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN: 0-691-02268-2. ↩

-

Forester, J. (2019). Five Generations of theory-practice tensions. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 2, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-019-00033-3. ↩

-

Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building resilience: Social capital in post disaster recovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN: 978-0-226-01288-9. ↩

-

Kawamoto, K. & Kim, K. (2016). Social capital and efficiency of earthquake waste disaster management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 18, 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.10.003. ↩

-

Sadri, A., Ukkusuri, S., Lee, S., Clawson, R., Aldrich, D., Nelson, M., Seipel, J., & Kelly, D. (2018). The role of social capital, personal networks, and emergency responders in post-disaster recovery and resilience: A study of rural communities in Indiana. Natural Hazards, 90(3), 1377–1406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-3103-0. ↩

-

Kravel, R. (2019). Indigenous and communitarian knowledges. In T. Halvorsen, K. Orgenet & R. Kravel (Eds.) Sharing Knowledge, Transforming Societies (Chapter 4, pp. 105–131). Cape Town: African Minds. ISBN: 978-1-928502-00-5. ↩

-

Rumbach, A. & Foley, D. (2014). Indigenous institutions and their role in disaster risk reduction and resilience: Evidence from the 2009 Tsunami in American Samoa. Ecology and Society, 19(1), 336–344. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-06189-190119. ↩

-

Links, J., Schwartz, B., Lin, S., Kanarek, N., Mitrani-Reiser, J., Sell, T., Watson, C., Ward, D., Slemp, C., & Burhans, R. (2018). COPEWELL: A conceptual framework and system dynamics model for predicting community functioning and resilience after disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 12(1), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2017.39. ↩

-

Pfefferbaum, R., Pfefferbaum, B., Van Horn, R., Klomp, R., Norris, F., & Reissman, D. (2013). The communities advancing resilience toolkit (CART): An intervention to build community resilience to disasters. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 19(3), 250–258. http://www.doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e318268aed8. ↩

-

Keil, R., Wekerle, G. & Bell, D. (1996). Local places in the age of the global city. New York: Black Rose Books. ISBN: 9781551640464. ↩

-

Lippard, L. (1997). The lure of the local: Senses of place in a multi-centered society. New York: New Press. ISBN: 928-1-56584-248-9. ↩

-

Feagin, J. & Bennefield, Z. (2014). Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Social Science and Medicine, 103, 7–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.101016/j.socsimed.2013.09.006. ↩

-

Edelman, B., Luca, M., & Svirksy, D. (2017). Racial discrimination in the sharing economy: evidence from a field experiment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2), 1–22. www.doi.org/10.1257/app.20160213. ↩

-

Fothergill, A., Maestas, E., & Darlington, J. (1999). Race, ethnicity and disaster in the United States: A review of the literature. Disasters, 23(2), 156–172. https://doi-org.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/10.1111/1467-7717.00111. ↩

Kim, K., Ghimire, J., & Yamashita, E. (2021). Sharing During Disasters: Learning From Islands Preliminary Findings and Initial Implications for Action (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 11). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/sharing-during-disasters-learning-from-islands-preliminary-findings-and-initial-implications-for-action