Steep Risks

Assessing Social Vulnerability to Landslides in Rural Puerto Rico

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

Landslide hazards are of special concern for public health during hurricane disaster response in Puerto Rico. After Hurricane Maria in 2017, more than 70,000 landslides occurred across communities in the mountainous interior of the main island, and hundreds more occurred after Hurricane Fiona in 2022. Despite documented impacts, it was previously unknown how many Puerto Ricans live with landslide risk. This mixed-methods study addressed that gap, determining for the first time the total population living in landslide-prone areas in Puerto Rico while also assessing their social vulnerability to disaster and revealing how communities experience and define their own vulnerability. Using an existing landslide susceptibility model and gridded population data, we analyzed the population exposed to landslides at a 100m scale and found that one-third of the Puerto Rican population—one million people—live in areas of high to extreme landslide susceptibility. We also conducted two focus groups in the municipality of Utuado (n=22) and semi-structured interviews with agronomists, emergency managers, community leaders, and local researchers (n=11) to assess the social dimensions of landslides. Early findings indicate that landslides were highly disruptive to the road network, which limited residents’ mobility and access to water, food, and healthcare. Landslides also blocked access to farms, leading to lost harvests and income. This study finds that age, disability, and remoteness are top indicators of vulnerability to landslides. Finally, we are working with local partners to develop an interactive map that shows the location of critical infrastructure—schools, health centers, transportation networks, among others—relative to vulnerable populations. The purpose of the interactive map is to enable public health practitioners and emergency managers to see where vulnerable populations are located relative to critical services after a disaster. We have made a draft version of the interactive map available.

Introduction

More than 70,000 landslides occurred in Puerto Rico after Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, and anywhere from hundreds to thousands of landslides occur on an annual basis (Bessette-Kirton et al., 20191; Hughes et al., 20192). Landslides disrupted transportation across the island, with the most significant impacts on rural populations. There are many anecdotal accounts of landslides blocking the only road to mountain communities, leaving people without access to critical medical care in the wake of disasters. Ambulances or other emergency vehicles also cannot reach these communities when landslides block or wash out road access. Despite the broad extent of landslide hazards in Puerto Rico, there has been no formal estimate of the total population living in high-risk areas for landslides. This information is a critical missing piece for addressing the public health needs of rural communities after heavy rainfall events like tropical storms.

Landslides need not damage homes directly to generate health concerns. In many cases, landslides damage drinking water pipes in the mountains, leaving rural households without access to clean water for weeks or months. After Maria and Fiona, this contributed to elevated cases of leptospirosis from contaminated water. At least 26 fatalities in Puerto Rico were attributed to this bacterial disease after Hurricane Maria (Sutter, 20183). Examining landslide hazards through a social determinants of health lens helps reveal how landslides, and slow responses to them, shape mortality and health outcomes for rural populations.

Landslides are understudied relative to other hazards likely because they primarily affect rural populations, and disaster reporting has been biased toward more densely populated areas (Nadim et al., 2006). Landslides also tend to occur as compound hazards, often following major events such as hurricanes, torrential rains, or earthquakes in Puerto Rico. As such, landslide impacts are systematically left out of many datasets because landslides are often nested under other hazards that precede or trigger them. Therefore, little is known about the effects of landslides on people and the disparities associated with landslide vulnerability. Understanding more about the populations exposed to landslides is a critical step toward improving preparedness and response to these hazards. Geological and engineering research tend to dominate landslide hazard scholarship, so this study aims to add a sociological lens of inquiry to this topic and clarify the public health implications of landslides.

Literature Review

Landslide Susceptibility

In this study, landslide susceptibility describes the likelihood of a landslide occurring at a given site based on physical characteristics, environmental conditions, and/or human activities. Susceptibility alone is important to provide context for landslide hazards, but it does not uniquely identify risk to people, which requires additional information about exposure and social vulnerability. Prior to Hurricane Maria, the landslide susceptibility map for Puerto Rico had not been updated since the 1970s. Hughes and Schulz (2020)4 developed a high-resolution landslide susceptibility model using several geospatial datasets and empirical data from a landslide inventory generated after Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017.

The datasets used to model landslide susceptibility include slope inclination, land-surface curvature, soil type, geologic terrane, mean annual precipitation, land use, pre-event soil moisture, and distance to roads and streams (Hughes & Schulz, 2020). They chose these factors after filtering a larger group of datasets based on sensitivity analysis and statistical analysis of more than 70,000 landslides (Hughes et al., 2019). They classified binned subgroups of each factor as more or less correlated to landslide sites in the inventory, creating a landslide susceptibility index (LSI) value. They then aggregated the LSI raster maps at 5-meter resolution into a compilation product, weighting slope more heavily than other factors. They normalized the values on this LSI compilation map based on their minimum and maximum values and, finally, assigned five categories of “low”, “medium”, “high”, “very high”, and “extremely high” to discrete ranges of the LSI values (Hughes & Schulz, 2020). This process resulted in one of the highest resolution landslide susceptibility maps available for any part of the United States, which created an opportunity to study population exposure in detail for the main island of Puerto Rico.

Social Vulnerability

Social vulnerability to disasters may be defined as “the sociodemographic characteristics of a population and the physical, social, economic, and environmental factors that increase their susceptibility to adverse disaster outcomes and capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from disaster events” (Adams et al., 20225). Social vulnerability indices are popular approaches to quantifying or measuring social vulnerability, and the CDC’s social vulnerability index (SVI) is one of the most commonly used in the United States. The SVI is constructed using 15-16 variables, or indicators, which include socioeconomic status, age, race, ethnicity, language, and housing type, among others (Flanagan et al., 20116).

Rural populations in much of Puerto Rico are uniquely vulnerable after hurricanes because of their exposure to landslides. Nearly half of the population in the rural mountain interior live below the poverty line (U.S. Census Bureau, 20227). There are also higher rates of chronic health issues in these areas, with some residents relying on oxygen machines and other life-sustaining medical devices, yet they have been deprioritized for power restoration after large power outages (Román et al., 20198; Tormos-Aponte et al., 20219 As Ramírez-Ríos and colleagues (2022)10 identified, landslides represented one of the major transportation barriers to healthcare access after Hurricane Maria. Furthermore, much of the population of Puerto Rico’s interior work in agriculture, which generally heightens their exposure and sensitivity to the impacts of natural hazards.

Research Questions

In general, there has been limited research on the human dimensions of landslide hazards, even less using qualitative methods. Therefore, this study sought to understand the populations living with landslide risk in Puerto Rico through a variety of methods.

We answered four research questions:

- What is the total population living in high-risk areas for landslides in Puerto Rico?

- How does social vulnerability vary across the exposed population, and what is the relationship between social vulnerability and landslide susceptibility?

- What are the negative impacts associated with landslide hazards for residents and communities?

- How do communities self-define social vulnerability to landslides?

Research Design

This study follows a concurrent mixed-methods approach (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 201811) with the goal of integrating secondary quantitative data with qualitative data regarding the social dimensions of landslides in Puerto Rico. We used quantitative methods to estimate the population at-risk for landslides and assess the relationship between landslide risk and social vulnerability. We used qualitative methods to understand how Puerto Ricans living with landslide risk perceive their vulnerability and what they are doing to counteract it. This section describes the methods we used to collect and analyze both quantitative and qualitative data.

Quantitative Analysis of Population Exposure

For the main island of Puerto Rico, we assessed population exposure to landslides by calculating the number of people living in areas within each of the five levels of landslide susceptibility from “low” to “extreme,” as described above. We started by combining existing geospatial datasets for landslide susceptibility at 5m resolution as well as 2020 population distribution at 100m resolution, downloaded from WorldPop (2020)12.

Next, we used QGIS software to conduct geographic information system (GIS) analysis, resampling the landslide susceptibility data from 5m pixel scale to 100m resolution based on the maximum susceptibility within each 100m pixel. This had the effect of slightly increasing the amount of land area categorized as high susceptibility, but in a way that we considered to be consistent with the scale at which people experience exposure to landslide hazards. This transformation enabled direct comparison of landslide susceptibility to the population dataset of the same scale. Then, population and the susceptibility index were compared for each 100m pixel. We computed raster layer zonal statistics which produced a population value for each of the five categories in the landslide susceptibility map: low, medium, high, very high, and extreme.

Social Vulnerability

We assessed social vulnerability quantitatively using the 2020 CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) data for Puerto Rico at the census tract level (Flanagan et al., 2011). The SVI is a composite measure of vulnerability that ranks census tracts relative to each other based on 16 demographic variables for 2020, including variables such as poverty, age, disability, education, minority status, housing type, and more (Flanagan et al., 2011). We calculated the average landslide susceptibility value for each census tract and compared it to the SVI value, which is a continuous measure scaled from 0 to 1, with 1 being more socially vulnerable and 0 being less socially vulnerable. Based on Pearson’s correlations, average landslide susceptibility and the 2020 SVI appeared to be uncorrelated at the census tract scale (r=0.09). However, the variable for those without a high school diploma was weakly positively correlated (r=0.28, p=0.000), suggesting a relationship between educational attainment and landslide susceptibility that merits further study.

Interviews and Focus Groups

We designed focus groups and semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative insights (Creswell, 201413). We conducted two focus groups in Utuado with a total of 22 participants, as well as semi-structured interviews with 11 residents and professionals who work in relation to landslide hazards. We followed best practices for conducting focus groups with potentially vulnerable populations (Peek & Fothergill, 200914). There were slightly more men than women in our sample, with a wide range of ages, from 18 to 70.

Study Site and Access

We based our qualitative work in the municipality of Utuado and surrounding areas for several reasons, including its remoteness from major cities, location in the mountainous zone of Puerto Rico (Cordillera Central), and preexisting relationships between the research team and local service providers and organizations. Moreover, the central municipality of Utuado experienced the highest concentration of landslides after Hurricane Maria in 2017 (Bessette-Kirton et al., 2019) and many more after Hurricane Fiona in 2022. Furthermore, residents of Utuado lived through several months without power and water, longer than most other municipalities. The impacts of Maria, coupled with the 2020 earthquakes, COVID-19 pandemic, and Hurricane Fiona in 2022, have left the municipality in a constant state of response and recovery.

Current socioeconomic constraints in Utuado exacerbated these accumulated shocks. More than half of Utuado’s population (54.6%) has an income under the federal poverty level, 24.5% of residents are age 65 or older and 14.1% of residents have a disability (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). It is also important to note that Utuado is an agricultural municipality, and many of its residents are involved in farming. The latest U.S. Department of Agriculture Census states that the Utuado region has the highest number of farms in Puerto Rico and is one of the main producers of coffee (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2020). In comparison to the general population of Puerto Rico, farmers tend to have a lower household income (Rodríguez-Cruz et al., 202215). Moreover, their dependence on and embeddedness with natural resources is linked to their exposure and sensitivity to natural hazards, but it also contributes to their nuanced traditional knowledge and lived experiences.

Focus Group Procedures

We carried out two focus groups in Utuado: We conducted the first at the University of Puerto Rico in Utuado with residents who either live near the urban center or commute to Utuado for work or school. We carried out the second focus group at the Corporación de Servicios de Salud Primaria y Desarrollo Socioeconómico El Otoao (COSSAO), which is located in barrio Tetuán, an hour away from Utuado’s urban center. Most residents of Tetuán are farmers or agricultural workers. We held both focus groups on weekdays at a time of the host’s choosing. Two members of the team (Jocelyn West and Luis Alexis Rodríguez-Cruz) conducted the two focus groups. The protocol for the focus group consisted of five guiding questions and prompts, which were facilitated by Rodríguez-Cruz, who served as the main facilitator, while West served as notetaker and participated in facilitating questions and prompts (Steward & Shamdasani, 201516). Additionally, team members used the focus group guide in semi-structured interviews with three residents. A second protocol guided semi-structured interviews with eight service providers. The team transcribed each focus group and interview recording verbatim to preserve meaning. West and Rodríguez-Cruz, both Spanish speakers, verified transcriptions and conducted thematic analysis (Creswell, 2014, 201617).

Participant Recruitment and Consent

Rodríguez-Cruz has close working relationships and partnerships (i.e., ongoing research and capacity building projects) with the aforementioned institutions. Rodríguez-Cruzcontacted key partners of each organization and provided information about the project. These collaborators expressed interest and agreed to provide us with spaces to conduct the focus groups. Each partner received the project invitation and consent forms with information about the scope of work and a $200 stipend for their collaboration. Focus groups participants were invited through purposive and snowball sampling (Creswell, 2014). All participants had witnessed and/or directly experienced landslide impacts. Ages ranged from 18 to 70, and formal education attainment ranged from junior high school to Ph.D. We obtained consent from individuals using a Spanish-language consent form. Participants and facilitators sat around a large round table and had refreshments available. West and Rodríguez-Cruz introduced themselves and reaffirmed consent verbally before starting the focus group activity. We conducted each focus group in Spanish and recorded with permission. Each participant received $50 compensation at the conclusion of the focus group discussion.

Focus Group Guide

The focus group guide was semi-structured and designed to elicit answers, conversation, and stories from participants about their encounters with landslide hazards since Hurricane Maria. The guide prompted participants to recall and compare landslide impacts to themselves and their communities after Hurricane Maria as well as Hurricane Fiona. The next questions focused on the response to landslide damage and progress with recovery. Then, we asked about risk perception and participants’ ideas about social vulnerability to landslides. We also asked participants to describe any preparedness or mitigation measures they have taken specific to landslide hazards.

Interview Procedures

The team recruited interview participants through existing professional networks related to landslide hazards or snowball sampling. We conducted interviews either in-person at a location of the participant’s choosing or via a secure Zoom video call in three cases. The interviewer first explained the consent form and obtained consent. The interviewer then obtained permission to start recording and followed the interview guide for conversations with service providers. When interviewees participated in their personal rather than professional role, the interviewer asked questions using the focus group guide and provided each participant with $40 compensation for their time.

Interview Guide

We created the semi-structured interview guide for conversations with professionals who work as service providers in relation to landslide preparedness, mitigation, or response. Many of the topics covered were similar to those from the focus group guide, but the questions focused more on the individual’s professional responsibilities and experiences in emergency situations. Finally, the interview guide included a demonstration and request for feedback on the map of susceptibility and population distribution in Puerto Rico.

Data Analysis Procedures

Thematic analysis of the combined focus group and interview transcripts is ongoing. Two members of the team have independently coded interview and focus group transcripts. Next, they will meet to discuss independent findings and establish a shared set of codes. This will be followed by a second round of coding using the established codes for the project. The qualitative thematic analysis will continue to be refined and developed to achieve stronger answers to the research questions.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

This project received human subjects approval (22-0594; exempt) from the University of Colorado Boulder Institutional Review Board on December 12, 2022. We took care to conduct focus groups and interviews in familiar settings near where participants lived or worked. It was important to us to secure funding for this project to offer compensation to participants for their time. We also started focus groups and interviews by sharing information about landslide risk, for which participants expressed gratitude. We provided participants with a physical or digital copy of the illustrated Landslide Guide for Residents of Puerto Rico as a resource for them to take home.

Our team employed an interdisciplinary approach to this research by combining data and methods across the social sciences and earth sciences to study public health in disasters. Our team members had prior experience conducting interdisciplinary and convergence research that is problem-oriented and solutions-focused, which prepared us to work across disciplines as a team on this project. During the project, we exchanged knowledge about methods and data integrity to strengthen our interpretations and answers to research questions.

Results

Population Exposure to Landslides

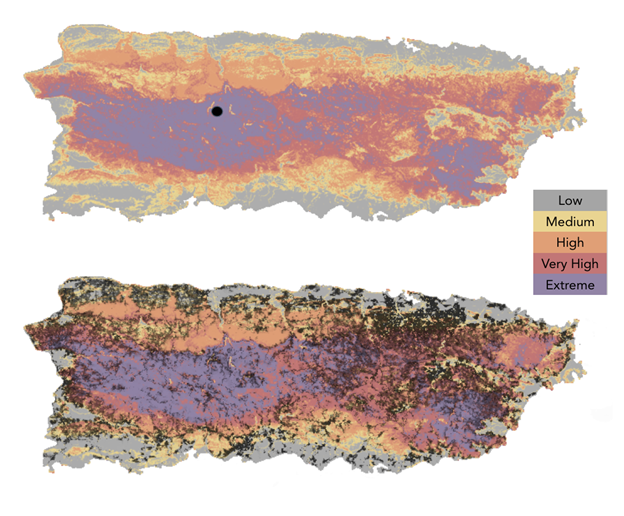

Figure 1 depicts two data visualizations of landslide susceptibility across the main island of Puerto Rico. The upper map shows landslide susceptibility using the five-zone landslide susceptibility index: Low (grey), Medium (yellow), High (orange), Very High (red), and Extreme (purple). The purple and red areas mostly align with the steep interior mountains, where Utuado is located, as depicted by the black dot on the map. The lower map shows the population distribution in black overlaid on the same susceptibility map, with the most populated areas shown in the upper right near the capital city San Juan.

Figure 1. Landslide Susceptibility and Population Distribution in Puerto Rico

Table 1 presents the results of our GIS analysis of the number of people living in landslide susceptible areas. This analysis indicated that more than one-third of Puerto Rican residents (1.07 million people) live in areas of high, very high, or extreme susceptibility to landslides. Nearly 180,000 people, About 6.3% of the total population, are living in areas with the most extreme susceptibility to landslides.

Table 1. Population Living in Landslide Susceptible Zones in Puerto Rico

Exposed |

Population Exposed |

Population Percentage |

|

| Low | 62.26 |

||

| Medium | |||

| High | 37.41 |

||

| Very High | |||

| Extreme |

Now that these estimates are available, they demonstrate the large extent to which Puerto Rican residents are exposed to landslide hazards in their everyday lives. This is not a far-removed problem for only the most remote populations. More than one-third of Puerto Ricans are living at risk. Even more residents have to commute to work or school in areas of high landslide susceptibility.

It is important to note that this is likely an undercount because the total population for Puerto Rico in this dataset is 2.86 million, but the latest U.S. Census estimate for Puerto Rico’s population is 3.22 million for 2022, a difference of 360,000 (11%). If the gridded population data are rescaled to match the Census total estimate, then as many as 200,000 people may live in areas of extreme susceptibility.

Social Vulnerability to Landslides

Quantitative analysis of the SVI and landslides at the census tract level suggested a weaker than anticipated relationship between social vulnerability and landslide hazards. Further investigation would help verify the lack of correlation. For instance, it is still possible that social vulnerability and susceptibility are correlated at a different scale (e.g., municipality level) or would be correlated if social vulnerability were defined and operationalized differently, as recommended by Tormos-Aponte et al. (2021) and West (2023)18. Based on feedback from participants about social vulnerability, analyses may be refined moving forward to determine which individual variables relate most to variation in landslide susceptibility at the census tract or municipality level.

As discussed below, qualitative findings from this study suggest that more attention should be paid to elderly populations, those with disabilities, and remote populations. In Puerto Rico, geographic factors including elevation and distance from urban centers are determinants of landslide vulnerability. Farmers who lived outside metropolitan municipalities were more likely to report food insecurity after Hurricane Maria (Rodríguez-Cruz et al., 2022). Furthermore, vulnerability measures should consider non-individual variables as well, such as geographic or structural factors (e.g., community remoteness, condition of road infrastructure, the state of local institutions that provide essential services, etc.).

Community Experiences With Landslides

Seeking Solutions for Perpetual Problem

It was clear that residents of interior mountain communities think about or deal with landslides on a regular basis. One participant described landslides as a “24/7/365” issue, meaning they can happen seemingly anytime in Utuado. Landslides can represent anything from minor nuisances to major threats to safety. Residents recognized that both natural and human activities can contribute to, or mitigate, landslides. For example, farmers and landowners reported planting vetiver or patchouli plants to stabilize slopes and reduce erosion. They also expressed a desire for more guidance about how to mitigate landslide hazards along road cuts.

Government Neglect

Participants also called attention to the nearly absent role of government in mitigating risk and responding to landslide hazards. They described being let down by slow responses from private insurance as well. Residents recounted being left to clear roads on their own after storms with whatever machinery or tools were available to them, contributing to disparities in the rate or degree of recovery after hurricanes. As one resident said:

The landslides have not been fixed; the roads have not been fixed. Here we are still as if hurricane season passed last month. And two or three months from now the season will come again. And here there is no need for a hurricane; if it rains for 12 hours straight, the roads are gone and landslides are the order of the day. There is no need for a hurricane. Because there is no planning, there is no maintenance of anything that exists.

Mental and Emotional Toll of Landslides

We heard many comments regarding the toll landslides have on the mental and emotional states of participants. The combination of continued impacts, accumulated hazards, and the sense of neglect from institutions seem to expand stress and worry among residents when they anticipate landslides.

Before [Hurricane] Maria there were landslides, but you never felt that sense of insecurity that… now it's raining and you're almost crying… because there could be landslides all the time. But now with these downpours one worries even more, because the house is already affected in the sense of [earthquake] tremors, landslides, and all that.

Discussion

Taken together, these results demonstrate that exposure to landslides is widespread and vulnerability to landslides is dependent on interconnected social and geographic factors. The analysis identified residents with needs for ongoing medical care as well as residents in remote or higher elevation areas as more vulnerable to harm or losses associated with landslides. Further research is needed to detect whether existing quantitative data align with participants’ lived experience and perspectives. In terms of livelihoods, dependence on agriculture also increased residents’ exposure to the effects of landslides. This suggests that agronomists and farmers alike could use more support with respect to mitigating and recovering from landslides.

Taking a step back, we hope that this study may eventually serve as a model for the study of the social dimensions of landslides in other locations and contexts. The diversity of information that can be gained about this hazard from quantitative and qualitative methods indicates that multiple modes of inquiry may be necessary to fully understand the impacts of landslides. For example, because so many landslides are cleaned up informally in Puerto Rico, there is little documentation of how residents have addressed the issue with their own resources out of necessity. This study provided glimpses into the solutions residents have found, as well as the support they would like to have for this work.

Furthermore, the qualitative data suggest that continued experiences with landslide hazards, coupled with the neglect felt by residents from local and federal institutions, has led them to take individual and collective actions to prepare for, respond to, and recover from landslide impacts. Here we note a possible feedback loop that could be the subject of future research. We grasp from the qualitative data that governmental mismanagement and neglect has led to distrust in institutions, which may fortify the discourse of self-sufficiency among rural residents that, in turn, allows the government to further shirk responsibility.

Finally, this work has implications for how the impacts of hurricanes are recorded. Stronger attention to landslides in post-hurricane research can clarify the mechanism for certain public health outcomes observed in rural areas. Therefore, future post-hurricane research should attend to the unique experiences of populations in landslide-prone areas.

Conclusions

Public Health Implications

There are several implications of this research for public health practice and policy. At a high level, practitioners and policymakers should recognize that a significant portion of the population in Puerto Rico lives with landslide risk. Slow responses to landslides in some areas exacerbate the second disaster that is recovery after hurricanes. Furthermore, landslide-affected communities are often medically underserved because areas with higher landslide susceptibility tend to have fewer medical or public health facilities. Participants mentioned the long distance that they have to travel to a hospital or health center in case of injury or medical emergencies after major storms. Public health practice should seek to close these gaps through preparedness efforts. Furthermore, identifying community organizations, such as nongovernmental organizations or community-based groups (e.g., neighbors that have organized together), can lead to better provision of resources in these underserved areas.

Compound hazards exacerbate public health concerns in rural areas after hurricanes. After Hurricane Maria, for example, landslides often limited mobility in communities that were also dealing with months-long power outages. Lack of potable water and electricity also became more dangerous and deadly when combined with impassable roads and long distances from health centers.

Post-Maria, residents and community groups have started anticipating possible isolation after hurricanes and taking preparedness measures, including stockpiling necessary medications for neighbors and, when possible, prepositioning heavy machinery that can be used to clear roads. Public health practitioners should identify and coordinate with these types of groups at the neighborhood level.

The uncertainty around when or where landslides may occur creates stress and anxiety for rural residents. Intense or frequent experiences with landslides seem to generate ongoing mental health concerns. Public health organizations should acknowledge that these nuisance hazards have day-to-day effects on people’s mental wellbeing in addition to the acute stress they can cause after major storms. As we documented, government neglect contributes to residents’ stress, heightening their experiences of isolation or abandonment by officials in times of need. Public health agencies should increase their engagement with landslide-susceptible communities and work more closely with community-based organizations to mitigate risk.

Limitations

This study’s limitations mainly relate to the scale of the analysis. First, we focused our qualitative research on the municipality of Utuado and surrounding municipalities, but we were not able to speak with individuals from other rural or mountainous regions. Therefore, our findings or interpretations may not be representative of all landslide-prone communities in Puerto Rico. Another limitation relates to the availability of accurate population data for Puerto Rico, the scarcity of which has been highlighted previously (Rivera, 202019). Our analyses of population exposure used the best available gridded population data but are limited by the accuracy of the modeled data, which are not an exact count of where people live. Finally, the measurement of social vulnerability in Puerto Rico represents another area for continued improvement as data availability currently limits analyses to the census tract level or larger spatial units.

Future Research Directions

This project raised questions for future research about the exposure of transportation infrastructure in addition to population exposure, calling attention to a need for a road network analysis in relation to landslide hazards and critical infrastructure in Puerto Rico. Interview participants made this suggestion directly or alluded to it in conversations about identifying which communities have only one point of access. Puerto Rico’s road network is also one of the densest in the United States. We believe this is an important future research direction and intend to build upon our understanding of landslide exposure and vulnerability through future analyses of the road network.

Future Research Application: Interactive Map of Landslide Susceptibility

To facilitate the application of the research findings, we have created a draft interactive map of landslide susceptibility that includes the locations of health centers and schools. In future versions of the map, we will incorporate the locations of transportation networks and other critical infrastructure. The purpose of the interactive map is to enable public health practitioners and emergency managers to see where vulnerable populations are located relative to critical services after a disaster. We intend to continue working closely with local organizational partners to continue developing the interactive map into a more intuitive and accessible tool for planning and public health.

In addition, we plan to make the data we used developing this tool available through the DesignSafe data repository, which will enable others to add the geospatial data layers to existing public health and disaster-related tools for Puerto Rico.

Finally, we plan to continue working with research assistants from the University of Puerto Rico Mayagüez on science communication activities. We are planning a communications campaign that will include presentations to community groups in mountain communities and interviews or op-eds with local media outlets in Puerto Rico.

Acknowledgments. Our team gratefully acknowledges the contributions of members of the UPRM SLIDES-PR team, including Tania Figueroa Colón and Kimberly Trahan, who assisted with the qualitative research and community outreach. We are also grateful for the efforts by COSSAO and the University of Puerto Rico Utuado in hosting focus groups. Many thanks to Francisco “Tito” Valentín and Mariangie Ramos Colón for assisting in setting up focus groups. Finally, we would like to thank our research participants for their trust, encouragement, and time spent discussing this topic with us.

References

-

Bessette-Kirton, E., Cerovski-Darriau, C., Schulz, W., Coe, J. A., Kean, J. W., Godt, J. W., Thomas, M. A., & Hughes, K. S. (2019). Landslides Triggered by Hurricane Maria: Assessment of an Extreme Event in Puerto Rico. GSA Today, 29(6), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1130/GSATG383A.1 ↩

-

Hughes, K. S., Desiree, B. G., Martínez Milian, G. O., Schulz, W. H., & Baum, R. L. (2019). Map of slope-failure locations in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria [Data set]. U.S. Geological Survey. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9BVMD74 ↩

-

Sutter, J. D. (2018, July 3). Deaths from bacterial disease in Puerto Rico spiked after Maria. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/03/health/sutter-leptospirosis-outbreak-puerto-rico-invs/index.html ↩

-

Hughes, K. S., & Schulz, W. (2020). Map depicting susceptibility to landslides triggered by intense rainfall, Puerto Rico. In Map depicting susceptibility to landslides triggered by intense rainfall, Puerto Rico (USGS Numbered Series No. 2020–1022; Open-File Report, Vols. 2020–1022). U.S. Geological Survey. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20201022 ↩

-

Adams, R. M., Evans, C., Wolkin, A., Thomas, T., & Peek, L. (2022). Social vulnerability and disasters: Development and evaluation of a CONVERGE training module for researchers and practitioners. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 31(6), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-04-2021-0131 ↩

-

Flanagan, B. E., Gregory, E. W., Hallisey, E. J., Heitgerd, J. L., & Lewis, B. (2011). A Social Vulnerability Index for Disaster Management. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1792 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau (2022). Population Estimates, July 1, 2022, Utuado Municipio. Quick Facts, Utuado Municipio, Puerto Rico [Data set]. Retrieved May 24, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/utuadomunicipiopuertorico ↩

-

Román, M. O., Stokes, E. C., Shrestha, R., Wang, Z., Schultz, L., Carlo, E. A. S., Sun, Q., Bell, J., Molthan, A., Kalb, V., Ji, C., Seto, K. C., McClain, S. N., & Enenkel, M. (2019). Satellite-based assessment of electricity restoration efforts in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. PLOS ONE, 14(6), e0218883. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218883 ↩

-

Tormos-Aponte, F., García-López, G., & Painter, M. A. (2021). Energy inequality and clientelism in the wake of disasters: From colorblind to affirmative power restoration. *Energy Policy, 158, 112550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112550 ↩

-

Ramirez-Rios, D., Wallace, W. A., Kinsler, J., Martinez Viota, N., & Mendez, P. (2022). Exploring Post-Disaster Transportation Barriers to Health Care for Socially Vulnerable Puerto Rican Co mmunities (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Grant Report Series). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/exploring-post-disaster-transportation-barriers-to-healthcare-of-socially-vulnerable-puerto-rican-communities ↩

-

Creswell, J. W., & Plano-Clark, V. (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd ed.). SAGE. ↩

-

WorldPop. (2020). Global 100m Population total adjusted to match the corresponding UNPD estimate: Puerto Rico population 2020 [Data set]. University of Southampton. doi:10.5258/SOTON/WP00660.

https://hub.worldpop.org/geodata/summary?id=28388 ↩ -

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th ed.). SAGE. ↩

-

Peek, L., & Fothergill, A. (2009). Using focus groups: Lessons from studying daycare centers, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina. Qualitative Research, 9(1), 31–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794108098029 ↩

-

Rodríguez-Cruz, L. A., Álvarez-Berríos, N., & Niles, M. T. (2022). Social-ecological interactions in a disaster context: Puerto Rican farmer households’ food security after Hurricane Maria. Environmental Research Letters. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac6004 ↩

-

Steward, D., & Shamdasani, P. (2015). Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. Sage. ↩

-

Creswell, J. W. (2016). Thirty Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher. Sage. ↩

-

West, J. (2023). Social vulnerability and population loss in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. Population and Environment, 45(2), 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-023-00418-3 ↩

-

Rivera, F. I. (2020). Puerto Rico’s population before and after Hurricane Maria. Population and Environment, 42(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-020-00356-4https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-020-00356-4 ↩

West, J., Rodríguez-Cruz, L. A., & Hughes, K. S. (2023). Steep Risks: Assessing Social Vulnerability to Landslides in Rural Puerto Rico (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 34). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/steep-risks