The Public Health Implications of Abandoned Spaces in Post-Maria Puerto Rico

Publication Date: 2022

Executive Summary

Overview

This study describes how engaging in community-focused planning and abandonment transformation processes can improve community resilience and public health in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States, is currently suffering from an alarming increase in abandoned properties, buildings, and vacant lots (hereafter referred to as “abandoned spaces”). Abandoned spaces are environmental hazards that increase risks to individual and community health and reduce opportunities for healthy and pro-social behaviors. Studies show they are associated with higher prevalence of chronic diseases, mosquito-borne illnesses, and injuries and also negatively affect the mental health of individuals living nearby.

The abandoned spaces crisis in Puerto Rico is further complicated by the archipelago’s high exposure to natural hazards and the deep economic vulnerabilities. Puerto Rico has the highest rates of poverty and economic inequality in the United States, but, there are also high levels of social cohesion, community resilience, and innovation in the archipelago that can be learned from as well. This study documents a transformation being led by municipalities and communities to address abandonment and ensure healthier neighborhoods.

Research Questions:

For this study, we investigated four research questions:

- What are the socio-economic conditions in communities affected by abandonment and what factors are driving the problem in Post-Maria Puerto Rico?

- What environmental and health risks are created by abandoned spaces?

- What actions are municipalities taking to address abandoned spaces?

- How does participation in collective action to transform abandoned spaces affect participants?

Research Design

We employed a convergence approach to build our research team. All our team members live in Puerto Rico and are practitioners in addition to serving as academics or scientific researchers. Two team members—Michelle Alvarado and Luis Gallardo—are the leading experts in Puerto Rico on the issue of abandonment and form part of the Centro para la Reconstrucción del Hábitat (in English, the Center for the Reconstruction of the Habitat, hereafter “CRH”). Four years ago, CRH was founded to address the severe abandonment crisis in the archipelago and is the only nonprofit organization in Puerto Rico dedicated to identifying and transforming abandoned spaces. We partnered with CRH to conduct this mixed methods study exploring abandonment in Puerto Rico in the Post-Maria context, the environmental and health risks associated with abandoned spaces, and collective actions to transform abandoned spaces into usable places.

Our study included the following data collection activities: First, we compiled secondary data on abandonment from three sources: (1) a survey of 46 municipalities conducted by CRH about the status of municipal code enforcement programs, (2) CRH-directed community-based inventories of abandoned spaces in 48 communities across nine municipalities, and, (3) code enforcement site reports from four of those municipal governments. Second, we compiled additional contextual measures from publicly available data sources to incorporate into our geospatial analysis. Third, our research team conducted an in-person survey of individuals in seven communities impacted by abandonment.

We then analyzed the data using descriptive statistics and geographic information systems (GIS) tools. This allowed us to identify socio-economic conditions associated with abandonment in the post-Maria context and the environmental and health risks that abandoned spaces create in communities. This study is ongoing and we plan to conduct in-depth interviews and focus groups in two municipalities in the near future.

Findings

Our study revealed that abandonment in Puerto Rico is more likely to occur in marginalized communities, including communities of color and working-class or poor neighborhoods. It also showed that the main drivers of increasing abandonment rates in the post-Maria context include tenure insecurity, migration, negligence, property tax debt, and lack of resources for municipal code enforcement programs. Moreover, it demonstrated that abandonment is associated with several environmental health risks, including higher levels of contaminated water, soil, and air; an increase in mosquitos and other disease vectors; public illicit drug activity; and other unwanted activities that threaten public safety.

The community-based survey also suggested that individuals participating in collective action to transform abandoned properties benefit from improved physical and mental health and adopt more healthy behaviors such as eating produce and exercising. Finally, the survey pointed to ways that collective action may increase social capital and feelings of pride and community enjoyment among participants.

Public Health Implications

Our study has several public health implications. First, we showed that municipal code enforcement programs are effective ways to reduce the risks related to abandonment, but these programs are chronically under-funded and under-staffed. Secondly, our finding that abandonment increased post-Maria in marginalized communities suggests that programs to address abandoned spaces should be incorporated into disaster response and recovery programs. Our results demonstrate that community-based inventories and efforts to transform abandoned spaces benefit communities in post-disaster contexts in multiple ways. Based on our findings, we recommend that public health and other officials responsible for emergency preparedness do the following: First, these officials should incorporate programs that train municipal governments and community groups to identify, monitor, and transform abandoned spaces within disaster plans. Second, disaster recovery funds should include funding for community-based inventories of abandonment and community-led transformation of said spaces.

Lastly, we recommend that programs to abate abandonment include community-based inventories and community-led transformation efforts. Our community-based inventories were better at identifying properties with greater environmental risks. Moreover, community-led collective actions to transform abandoned spaces into community assets showed the potential to remove environmental health risks and benefit participants in these actions via increased social interaction.

Introduction

Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States, is currently suffering from an alarming increase in vacant and abandoned residential properties, buildings, and undeveloped lots (hereafter referred to as “abandoned spaces”). The abandoned spaces crisis in Puerto Rico is worsened in part by the high number of natural hazards affecting the archipelago. According to the Climate Risk Index, Puerto Rico had the most climate-related loss events in the world over the past two decades (Eckstein et al., 20211), including major hurricanes in 2017, Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Maria, and an earthquake swarm reaching 6.4 magnitude throughout 2019 and 2020. These cumulative disasters have worsened abandonment and exacerbated the chronic problem of abandoned spaces in almost every municipality across Puerto Rico.

This study documents abandonment in Puerto Rico in the post-Maria context, the environmental and health risks associated with abandoned spaces, and efforts by municipal governments and community groups to transform abandoned spaces. Puerto Rico has some of the highest poverty rates of any United States jurisdiction, and the sixth highest level of economic inequality in the world. The first goal of our study was to illuminate the links between these economic inequalities, abandoned spaces, and public health risks. Puerto Rico, however, is also known for high levels of social cohesion (Roque et al., 20202). We saw this demonstrated in municipalities’ code enforcement efforts (hereafter “code enforcement programs”) to curtail abandoned spaces that had become public nuisances; defined as a property with the potential to affect the health, safety, welfare, and/or comfort of the general public. Our second goal in this project was to learn how Puerto Ricans are collectively responding to public health challenges posed by abandonment.

Literature Review

Hypervacancy and Abandonment in Puerto Rico

Experts in the field of housing and urban development have defined communities with vacancy rates of 25% or higher as suffering from “hypervacancy,” a condition which “vacant properties—either buildings or vacant lots or both—are so extensive and so concentrated that they define the character of the surrounding area” (Mallach, 2018, p. 4-53). Research has also shown that hypervacancy is unequally distributed and concentrated in marginalized communities, including working class communities and communities of color (Klein, 20174; Harrison & Immergluck, 20215).

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.)6, the archipelago had a vacancy rate of 22.7% in 2020, which was more than two times the average of mainland United States and has been increasing at a fast pace during the past two decades, doubling from 11.2% in the year 2010. Many neighborhoods in municipalities across Puerto Rico have neared or surpassed the hypervacancy threshold of 25%. Evidence suggests that Hurricanes Irma and Maria are partially responsible for the accelerating rate at which properties are being vacated and that the most vulnerable places may be the most affected. A recent study of the San Juan metropolitan area, for example, showed that storm impacts from Hurricane Maria had increased vacancy rates and that vacancies averaged between 18.6 and 27.4% in some of the most populous San Juan neighborhoods (Santiago et al., 2022, p. 147).

Public Health Effects of Abandonment

Research shows a strong association between abandonment and negative health outcomes. For example, a comprehensive review showed that abandonment negatively affected public health in numerous ways, including higher rates of violence, chronic illness, psychological behavior dysfunctions, child maltreatment, elevated blood lead levels, neurological damage, hyperactivity, learning disabilities, and suicide (de Leon & Schilling, 2017[^De Leon]). Another study of 295 cities in the United States found that adults living in neighborhoods with long-term vacancy rates of three years or more were significantly more likely to suffer from heart disease, asthma, and mental illnesses (Wang, 20188).

Ecosocial Theoretical Framework

In this study, we applied an ecosocial theoretical framework to explore and visualize how politics, economics, the built environment, social networks, and other social determinants work to impact health at the individual level (Krieger, 20129). Ecosocial theory explains connections between multiple levels, from the individual to the global, and locates determinants of health within economic and political systems. There are four elements of the theory: (1) embodiment, (2) pathways of embodiment, (3) cumulative interplay of exposure, susceptibility, and resistance, and (4) accountability and agency. Embodiment is the process by which social determinants of health “get under the skin” and change individual physical and mental health status. Pathways of embodiment describe the specific mechanisms that connect broad social trends or large-scale events to individual health effects. For example, in Puerto Rico, Hurricane Maria harmed mental health via various connected pathways, including economic crisis, bankruptcy, out-migration, and social isolation (Benach et al., 201910). The cumulative interplay of exposure, susceptibility, and resistance recognizes that there are determinants of health that increase people’s exposure to health risks, and there are others that increase either susceptibility or resistance to negative health outcomes.

Lastly, accountability and agency describe two related issues. First, people in power have accountability to the people whose lives are directly impacted by their decisions. Secondly, individuals have agency to act on the multiple determinants of health that impact them and their communities. Exercising such agency can increase individual resistance to negative health impacts by increasing social capital and social connectedness (Krieger, 2012). Figure 1 shows how we applied this theory to identify the effects of abandoned spaces and efforts to transform them on public health and other social conditions.

Figure 1. Ecosocial Model of Abandoned Spaces and Health

Image Credit: Research Team.

Research Design

We designed a mixed methods study to explore abandonment in Puerto Rico in the Post-Maria context, the environmental and health risks associated with abandoned spaces, and collective actions to transform abandoned spaces into usable places. We modeled our research design on other studies that explored blight (i.e., Pinto et al., 202111) and collected data that combined objective and subjective measures. This design allowed us to observe the interplay between the physical cases of abandonment in a community and their less apparent impacts on behaviors, social interactions, and perceptions. More specifically, we asked the following four research questions:

- What are the socio-economic conditions in communities affected by abandonment and what factors are driving the problem in Post-Maria Puerto Rico?

- What environmental and health risks are created by abandoned spaces?

- What actions are municipalities taking to address abandoned spaces?

- How does participation in collective action to transform abandoned spaces affect participants?

Research Team and Convergence Approach

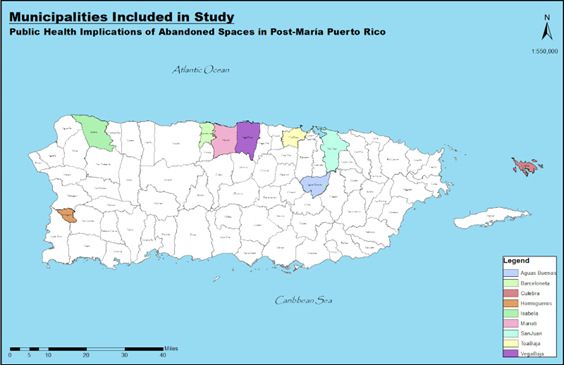

Our research team is composed of four researchers who all live in Puerto Rico, three of whom are Puerto Rican. We include a lawyer and long-time affordable housing advocate, an anthropologist lawyer with expertise in community and environmental law, an urban planner who presided the Puerto Rican Planning Society and currently works for a major philanthropic organization, and public health expert who specializes in exploring the social determinants of health with a systems focus. All our team members are also practitioners in addition to serving as academics or scientific researchers. The first two team members—Michelle Alvarado and Luis Gallardo—are the leading experts in Puerto Rico on the issue of abandonment and form part of the Centro para la Reconstrucción del Hábitat (in English, the Center for the Reconstruction of the Habitat, hereafter “CRH”). Four years ago, CRH was founded to address the severe abandonment crisis in the archipelago and is the only nonprofit organization in Puerto Rico dedicated to identifying and transforming abandoned spaces. CRH uses research, policy advocacy, and community organizing to accomplish its mission. One CRH milestone includes the surveying of over 2,600 nuisance properties throughout 16 municipalities, as well as spearheading the creation of Puerto Rico’s very first community land bank in the municipality of Toa Baja. Figure 2 shows a map of the municipalities where CRH has provided services and where several research activities for this investigation took place.

Figure 2. Map of Municipalities Partnering with the Center for Reconstruction of the Habitat (Click to Enlarge)

Our team’s expertise in abandonment and public health, our lengthy experience as practitioners working on these issues, and our deep roots in the Puerto Rican communities where we did this study enabled us to employ a convergence approach that is “transdisciplinary, problem-focused, and solutions-oriented” (Peek & Guikema, 2021, p. 105212). Table 1 shows the municipalities where CRH has provided services and where several research activities for this investigation took place. The table shows the population living in communities served by CRH. We drew on CRH’s pre-existing partnerships with these municipalities and their community members to carry out the community-based methods we used in this study.

Table 1. Municipalities and Communities Partnering with the Center for Reconstruction of the Habitat and the Research Team

| Aguas Buenas | ||||

| Barceloneta | ||||

| Culebra | ||||

| Hormigueros | ||||

| Isabela | ||||

| Manatí | ||||

| San Juan | ||||

| Toa Baja | ||||

| Vega Baja |

Data Collection Methods

We completed the following data collection activities: First, we compiled secondary data on abandonment from three sources: (1) the CRH survey of 46 municipalities about their code enforcement programs, (2) CRH-directed community-based inventories of abandoned spaces in 48 communities across nine municipalities, and, (3) code enforcement site reports from four of those municipal governments. Second, we compiled additional contextual measures from publicly available data sources to incorporate into our geospatial analysis, such as: estimated population; the extent of relevant boroughs (for data geography purposes); median age; poverty rate; median household income; median property value; vacant properties per the U.S. Census; relevant water body proximity, industrial and commercial activity, or tourism-driven activity; and health-related variables such as proportion of the population with disabilities, percent of the population with health insurance coverage, and population replacement rate. Third, our research team conducted an in-person survey of individuals in seven municipalities impacted by abandonment. Each of these data collection activities is explained in more detail below. This research project is ongoing and researchers plan new rounds of data collection, including in-depth individual interviews and focus groups for the two case studies.

Secondary Data

Municipal Survey. CRH conducted a municipal survey to inform their programming and policy platform in April 2022. Our team used the municipal survey to get an overview of the scale of abandonment in Puerto Rico and gain a deeper understanding of the breadth of municipal responses across the municipalities. The survey gathered responses from municipal code enforcement program staff in 46 of Puerto Rico’s 78 municipalities, which comprise 59% of all municipalities in Puerto Rico.

Community-Led Inventories of Abandoned Spaces. One of CRH’s major programmatic initiatives is to train municipalities and community-based stakeholders to inventory the abandoned spaces in their communities. These inventories serve as baseline assessments that support local code enforcement programs as well as the design of transformation projects and city-level public policies. To conduct the inventories, CRH organized community meetings to describe the project, consulted with neighbors of abandoned spaces, and worked with residents to identify properties. In total, CRH has facilitated 48 of these inventories within nine municipalities, which provided the research team with data on 1,856 abandoned properties. The inventories provided basic information on the properties (e.g., location and type of building) and rated their physical conditions on a scale that included “good” (property is habitable by clearing up vegetation, garbage, and maintenance-related upkeep), “regular” (missing windows or doors, with repairs within the scope of a “handyperson”), or “bad” (damaged roofs, ruins, or structural faults). Specific indicators related to public health risks include: illegal drainage, the presence of suspected toxic chemicals, illegal landfills, stagnant water, trash accumulation, among others to be discussed below.

Municipal Code Enforcement Data. Our research team supplemented the community-based inventories by gathering additional data for 864 of these properties from the four municipal governments who have already implemented code enforcement programs. This sub-population of properties had already been processed through their respective nuisance declaration protocols, providing valuable information on property owners’ city and state of residency, rate of appearance and compliance, property tax debts, availability of deeds, and the presence of tenure issues related to lack of title registration or heir problems.

Community-Based Surveys

To better understand the perceptions of community stakeholders, including leaders, activists, and residents, our research team conducted community-based surveys in person in seven total communities, within the municipalities of Barceloneta, Cidra, Culebra, Florida, Orocovis, Toa Baja, and San Juan. We recruited survey participants during CRH-organized community meetings about the municipal code enforcement programs. During the recruitment speech, a member of our research team read the informed consent information and explained that all survey participants would be able to ask questions or opt out of the survey if they preferred. Our survey sample was not designed to be representative of the broader community and results are not generalizable, as we utilized purposive sampling. We employed this sampling strategy for theory development rather than to prove a hypothesis (Etikan et al., 201613).

Our research team created two survey instruments. The first was designed for two communities that had a known history of collective action responses to abandonment. The second survey instrument was designed for five communities that we had assessed as having little to no experience of collective action to address abandoned spaces or their associated problems. In total we surveyed 134 individuals across 42 communities, including 51 people from the two communities with known collective action and 83 people in the five communities where there was no known collective action.

Both survey instruments included questions for respondents about their views of community health problems, health behaviors, health risks, perceived health of neighbors, and self-described health status. The surveys also asked respondents about their communities and abandonment. These questions were followed by open questions which allowed participants to describe their views and emotions in more depth. In addition, respondents were asked about their perceptions of the actions their municipal governments had taken to address abandonment. Lastly, participants were asked to describe how the following topics changed before and after the 2017 hurricanes: abandonment, collective actions to rescue abandoned spaces in the communities, physical and mental health status of self and neighbors, health behaviors, social capital, community services and spaces, and health risks. Survey participants in communities with known collective action were also asked to describe these topics before and after the collective action began to transform abandoned spaces.

Table 2 shows the seven communities where we conducted the in-person survey, the type of survey instrument used, and other data collection activities that were carried out in those communities.

Table 2. Community-Based Survey Sites

Sites Participating in Survey | ||

| Barceloneta | No Collective Action | |

| Cayey | No Collective Action | |

| Cidra | No Collective Action | |

| Culebra | Collective Action | |

| Florida | No Collective Action | |

| Orocovis | No Collective Action | |

| San Juan | No Collective Action | |

| Toa Bajo | Collective Action |

Data Analysis

Municipal Survey Data Analysis

CRH staff obtained survey responses via an online Google Forms questionnaire sent directly to nuisance program contacts in each of Puerto Rico’s 78 municipalities or via telephone, wherein CRH staff entered said data into the form’s questionnaire. Once compiled, information was exported into spreadsheet format to enable visualization and analysis. For all of the questions, researchers calculated percentages of the total with the total number of participants in the denominator, resulting at times in totals less than 100% for many multiple response answers as “not applicable” or “do not know” answers were present in some responses.

Analysis of Inventory and Code Enforcement Cases

The community-led inventories facilitated by the CRH team, included all code violation data in addition to multiple other measures related to potential health risks as described above. In addition, we had access to secondary data on relevant tax and public nuisance elements and processes from municipal administration and tax databases which in the case of four municipalities (Barceloneta, Hormigueros, Toa Baja and Vega Baja). This allowed us to cross-reference these code enforcement data with general inventory data to draw conclusions about relationships between enforcement, tax revenue impacts, and abandonment trends in said municipalities. All 1,856 cases were georeferenced and unified into one sole dataset and contains over 70 data fields which can be cross referenced and overlaid among themselves or with additional data.

Geospatial Analysis

We combined the contextual measures described above with data collected from community-led inventories of abandonment and the code enforcement site reports. Some secondary measures were available only at a municipality-wide scale, while others were available at the census tract level. Therefore, the first step was making data adjustments to match said scales. Next, we created georeferenced community profiles with data from data.census.gov (which houses data from the American Community Survey and the Puerto Rico Community Survey, among other surveys) and local georeferenced data for infrastructure, risks, natural resources, using Geographical Information Systems (GIS). Finally, we created a spreadsheet table arranging specific measures by community to identify patterns. These statistical and geographical elements of the analysis aspire to lead the research towards a better understanding of when, how, and why these phenomena documented by the inventories keeps developing.

Community-Based Survey Analysis

We uploaded the responses from the community-based survey into a spreadsheet and counted responses to each option for all questions, as well as non-responses. We then compared them by grouping (communities with collective action and communities without collective action) and calculated the differences in the before and after questions. For most questions, we calculated percentages of the total by the two groups with the total number of participants in the denominator. Only where indicated, the denominator was changed to total number of responses due to the high level of non-responses on a few questions to provide a more accurate description of the comparative proportion of answers. We then compared how answers differed by time period (before Hurricane Maria or after, before collective action to transform abandonment began in the community or after), or across the two groups of communities (communities where there was no collective action compared to communities where there was collective action). For qualitative answers, we reviewed each single answer and grouped them by theme. Here again, trends and patterns were identified both across the data and within, paying particular attention to differences between communities that were known for taking some collective action in the identification, abatement and transformation of abandoned spaces, and those that were perceived with no collective action efforts.

Ethical Considerations, Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity and Other Considerations

The primary study sites for this project were communities for which CRH was providing services or initiating services. Moreover, as described above, two members of the research team are CRH leaders and we have envisioned this research effort as an opportunity to hone their organization’s capacity to work with communities. Therefore, we prioritized reciprocity and considered it to be essential for the co-creation of knowledge with community members. Our research team feels it is our ethical responsibility to both inform communities about the harms of abandonment and provide them with tools to minimize those harms.

Data collection procedures, including recruitment protocols and all instruments, were approved by the Ethical and Independent Review Services (IRB), a private IRB Board that is unaffiliated with any university, on January 18, 2022, before any data collection activities commenced. Although we sought a local IRB approval, it was not possible due to the short timeline of our rapid research and the disruption to business activities that results from a long Christmas holiday in the University of Puerto Rico, lasting through January.

Findings

Abandonment in the Post-Maria Context

As mentioned above, several indicators suggest that abandonment is a growing problem in post-Maria Puerto Rico. The results of our community-based survey show residents agree, as nearly 70% stated that the amount of abandoned structures in their neighborhood had increased since the 2017 Hurricanes. Similarly, 54% of local municipal leaders responding to the municipal survey said that the vacancy rate in their municipalities was much higher than official estimates. In this section, we describe the findings from our analysis of abandonment cases. This analysis reveals the types of places where abandonment is more likely to occur and the drivers of increasing abandonment rates in the post-Maria context.

Geography of Abandonment

Our analysis, as other studies prior to ours have also found, shows that abandonment is more concentrated and enduring in marginalized communities. These same communities are also more vulnerable to other public health impacts of natural hazards. Yet, there are nuances regarding types of abandonment depending on factors, such as the reason why the community occupied the space or settled originally, availability of infrastructure, proximity to water bodies, and general demographic history of the community. We found that land use planning and the way these settlements were developed have the biggest influence on their future path, including the health risks that will be imposed upon their residents.

Our analysis of the geography of abandonment also revealed the extent of post-Maria economic and housing vulnerabilities in the municipalities and the study sites where we focused our research after Maria. Table 3 depicts the socio-economic and housing conditions in the municipalities where most of our research activities took place. Table A1 in the Appendix expands this table to show how socio-economic conditions at the community-level varied from the average conditions in the municipality. Our analysis of this data showed that communities with an above average presence of abandonment also consistently reported employment rates significantly higher than the average municipal rate. At the same time, these communities had considerably higher poverty rates and lower median household incomes. In other words, people who live in communities with higher rates of abandonment are generally working more, for less. Also, the median value of their properties is consistently lower than the municipal averages.

Table 3. Socio-Economic and Housing Conditions in Selected Municipalities

| Aguas Buenas | |||||

| Barceloneta | |||||

| Culebra | |||||

| Hormigueros | |||||

| Isabela | |||||

| Manatí | |||||

| San Juan | |||||

| Toa Baja | |||||

| Vega Baja |

We analyzed differences in accident risk by type of building and found that abandoned buildings that are residential are more likely to present an accident hazard risk (23% of all residential buildings in our dataset) compared to buildings that were either commercial, for mixed use, or undetermined (15% of all buildings in any of the three categories). Furthermore, our data demonstrate that the presence or proximity of informality, water bodies, and industrial uses—such as quarries and power plants—as well as the tourist industry and outside investment, play a part in the growing emergence of abandonment and blight within these settlements.

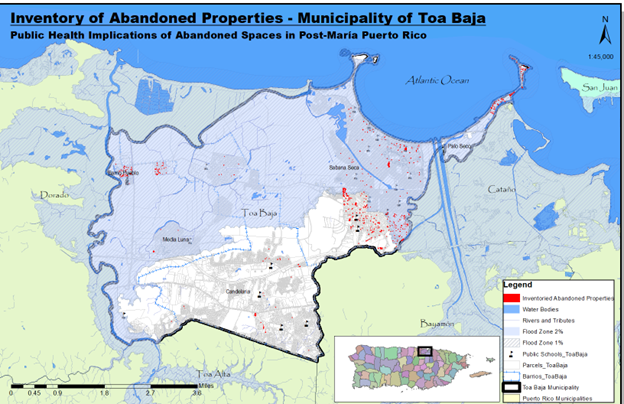

Figure 3 demonstrates one such case study, illustrating an overlay analysis including variables such as the community-led inventories of Toa Baja and the location of water bodies. This map was particularly informative in identifying proximity to water bodies as being associated with higher levels of abandonment in communities, a pattern we saw repeated across the municipalities. This map consists of a bird’s eye view (1: 45,000) of the whole municipality. Toa Baja, being the municipality with the most entries within the inventory, has the most different examples of types of abandonment. From this analysis, flood zone-designation and proximity to bodies of water seem to be the predominant factors promoting abandonment in this municipality. Table A2 in the Appendix provides additional information on the settlement types and other community and environmental conditions in each of the study sites, including their flood zone designation and proximity to bodies of water.

Figure 3. Inventory of Abandoned Properties in the Municipality of Toa Baja

(Click to Enlarge)

Drivers of Abandonment in the Post-Maria Context

Our analysis of abandonment cases revealed factors that contributed to properties entering various stages of abandonment. We identified the main drivers of abandonment, described below.

Tenure insecurity. The vast majority of abandoned properties demonstrated title issues and tenure insecurities. There is no standard approach for determining whether a property is “tenure insecure.” To determine tenure insecurity for this study, we developed a list of indicators based on our previous experience dealing with housing law: properties that were owned by heirs, properties that were not registered in the cadastral system, and also cases where legitimate persons of interest appeared though did not match with owner names as registered. For example, our previous work has showed that properties owned by heirs and properties which were not registered in the municipal cadastral system are more likely to have problems associated with abandonment, so we used these as indicators of tenure insecurity. In total, 71% of the abandoned properties we identified in our review of the code enforcement program were tenure insecure, with some properties triggering multiple indicators.

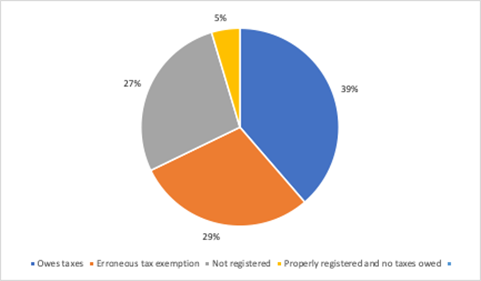

Only 15% of the abandoned properties we identified in our review had functional, publicly available deed registry information. Even though the Property Registry is voluntary, it represents the prima facie protection to those registered and is required for many legal and banking transactions. As elaborated below, 27% of the abandoned properties in our review were not registered in Puerto Rico’s tax collection system, suggesting that many were the result of unauthorized construction.

Migration. Our analysis also showed that property owner absenteeism could be a significant factor in some abandonment cases. We identified the last known residential address of persons of interest for 594 code enforcement program cases. Of these, only 304, or 51% of addresses were current and functional. More than half of the owners of the abandoned properties—55%—were still living within the municipality. Approximately 36% were living within another municipality, most often the closest metropolitan area. Nine percent were living in mainland United States.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.), the Puerto Rican population decreased by 2.2% between 2000 and 2010, the first time that population had declined since the U.S. Census Bureau conducted its first decennial census of the archipelago in 1910. An even more stunning decline occurred between 2010 and 2020, as the population shrunk by 11.8%, by far the most dramatic reduction in population in Puerto Rico in recent history (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.). Our evidence suggests that internal migration within Puerto Rico is a more significant driver in separating owners from their properties than migration to the United States mainland. However, the post-Maria population decline suggests that the latter may become a more significant driver of abandonment in the near future.

Negligence. Most owners of abandoned properties which have been cited as nuisances never respond to requests by municipal officials for them to abate the code violations. Property owners, possessors, or persons of interest appeared in only 44% of code enforcement program cases. All properties cited for code infractions have to pass through a legal withdrawal process which requires owners to participate. The reluctance of owners to participate in abatement suggests most of these properties will continue to slide towards deep abandonment without any intervention.

We were initially hesitant to presume negligence for “no show” owners, because, as we discuss in more detail below, municipalities lack resources or updated addresses to inform absent property owners about their code violations. Nevertheless, in combination with other factors, as well as the observance of total inaction on behalf of owners, lack of interest can be attributed to a property progressively becoming worse.

Property Tax Debt. The property tax status of abandoned properties in our dataset was quite diverse, but suggested that owners who fail to keep up with their tax obligations may be at higher risk of letting their properties fall into abandonment. Figure 4 shows the distribution of code enforcement program properties based on their cadastral and tax collection status. As the figure depicts, only 43% of the abandoned properties researchers reviewed were properly registered on the tax rolls and just 5%, were up to date with their tax payments. The median debt amount was $3,758.54. We interpret high tax debts as an indicator for absent or disinterested property owners with higher tax debts correlated to worse property conditions, as higher debts were correlated to an increased number of code enforcement violations.

Figure 4. Tax Status of Abandoned Properties

Lack of Resources for Municipal Code Enforcement Programs. Our analysis showed that when municipalities were successful in contacting owners about their properties through Code Enforcement Programs, owners responded proactively and abated 72% of the code infractions. Overall, 55% of owners or other persons of interest appeared after being contacted by municipal code enforcement officers. Of persons of interest who appeared, 90% either abated their nuisance properties or were in the process of doing so at the time of this publication.

Efforts to contact owners, however, were often severely hampered by deficient public records or address systems, as mentioned above. Of the global population of code enforcement cases, only 35% of properties had functional mailing addresses for their listed owners. This suggests that lack of compliance with municipal orders is strongly tied to the lack of resources and data in municipalities to locate and inform absent owners.

Environmental and Health Risks Associated With Abandonment

In this section, we use data from two data sources—the community-based property inventories and community surveys—to identify risks that abandoned structures pose to population health.

Environmental and Health Risks Identified in Community-Based Inventories of Abandoned Spaces

The environmental and social code violations identified in the inventories are associated with several health risks to the surrounding community. These have been detailed in Table 4. For example, standing water creates conditions for increased mosquito breeding, leading to higher risk of mosquito-borne diseases, while illegal drainage and suspected toxic chemicals contribute to pollution of water that people use for household needs or recreation, rusty metals pose accident risks and potential risk for tetanus, and vandalism and illicit activities decrease community sense of safety, often reducing outdoor exercise options and social cohesion as a result.

Table 4. Risks to Population Health Identified in Community-Based Inventories of Abandoned Properties

| Illegal drainage | 18 |

| Dead animals | 25 |

| Fiberglass | 32 |

| Suspected toxic chemicals | 67 |

| Oil spills | 73 |

| Unauthorized animals | 84 |

| Fire damage | 157 |

| Excrement or urine | 177 |

| Illegal landfill | 180 |

| Abandoned vehicles | 199 |

| Rodents | 412 |

| Stagnant water | 459 |

| Rusty metals | 532 |

| Pests | 633 |

| Garbage accumulation | 748 |

| Debris accumulation | 871 |

| Drug paraphernalia | 72 |

| Illicit activities | 129 |

| Vandalism | 252 |

Environmental and social code violations were identified in both community-led inventories and the municipal code enforcement program data which was based on complaints at similar rates (73% and 75% of all properties respectively). However, the concentration of such risks did differ between these two groups. Properties identified through community-led inventories documented on average 3.03 environmental code enforcement violations while complaint properties had 1.99. This suggests that community-led inventories provide a more detailed portrait of the threat posed by abandonment to public health.

Community Perceptions of Health Risks Associated With Abandonment

Table 5 reports the principal health problems identified by community members participating in the community-based survey. As the table shows, the greatest percentage of community members reported mental illnesses were the greatest health threat in their communities (with 75.2% of respondents classifying mental illnesses as either the principal health problem facing their communities or a problem though not the principal problem). An even greater overall percentage of respondents identified chronic illnesses as a health problem in their communities (78.38% of respondents), although slightly fewer classified chronic illnesses as the principal health problem facing their communities. These perceived health problems are associated in various ways with abandonment. For example, research has shown that adequate nutrition and exercise are both protective against mental and chronic illnesses, and our comparison of the diet and exercise behaviors of community members before and after abandonment increased in their communities points to the possibility that abandonment impacts these health behaviors.

Furthermore, our survey found that abandonment impacts feelings of pride and social connections, both of which are linked to mental health. Over one fifth of respondents identified criminal violence or mosquito-borne illnesses as the principal health problem in their communities. Criminal violence can impact community health in a number of ways, from direct injuries to acute psychological trauma to increased health risks that mediate the pathways to other negative health outcomes, such as low quality or quantity of sleep or social isolation.

Table 5. Percent of Respondents Identifying Issue as Public Health Problem in Their Community

| Intrafamilial violence | |||

| Criminal violence | |||

| Chronic illnesses | |||

| Mosquito-borne diseases | |||

| Mental illnesses | |||

| Sexually-transmitted or drug use-related illnesses |

a Respondents who identified the issue as a public health problem, but not the principal problem in the community.

b Respondents who identified the issue as the most prominent public health problem in the community.

In our analysis of the survey results, we made two comparisons—one between communities where there was collective action and where there was no collective action, and one between the time points before abandonment increased in the neighborhood and afterward. In reviewing results across these time periods, there were two clear trends—first, both self-reported health and the perception of the respondents’ neighbors’ health were generally better in communities with collective action when compared to communities without collective action, across physical health and mental health. Second, the same measures of self-reported health and perceptions of neighbors’ health were also improving when respondents compared these health statuses to before collective action began, and conversely they were decreasing when they were compared to a time when there was less abandonment in their neighborhoods. Taken together, these trends reinforce other research findings that abandonment is a health risk across several health outcomes (de Leon & Schilling, 2017; Wang, 2018), and they reveal an exciting area for further inquiry—the potential for collective action to be health protective at both the individual and community levels. While there may be broader trends that impact the changes in health over time, the comparison of different geographic communities across the same time period as well as the same communities across time reinforces the strength of these findings.

In communities where no collective action was known to the CRH prior to the survey, researchers asked whether health risks associated with abandonment have increased since Hurricane Maria. Almost two thirds (63%) noted an increase in trash around or in abandoned spaces. A majority of respondents (55%) reported an increase in mosquitoes and standing water. Fewer respondents noted an increase in the public consumption of drugs (29%) or violence or crime (22%). This suggests that health risks associated with abandonment are increasing in the post Maria context in communities which are not organizing to address the issue.

Municipal Response to Abandonment

The municipal survey demonstrated that the vast majority of municipalities—93.5%—were interested in addressing abandonment to tackle health, environmental, and security concerns. Nevertheless, our review of the municipal code enforcement data revealed variation in the degree to which municipalities were prioritizing abandonment and capable of responding to it. For the most part, data showed that most municipalities were failing to address the matter entirely. When measuring different activities carried out by municipalities in response to nuisance control, 31% had utilized eminent domain powers to expropriate abandoned structures, 16.7% had purchased the property at market rate, and 2.4% had started some sort of foreclosure proceeding. Nevertheless, very few municipalities actually ended up selling abandoned properties to the general public, with only 6% reporting so. Even when considering selling, municipalities rarely considered ways that the properties could be used to address the needs of low- and middle-income families or community-based projects, opting instead for selling at market rate, primarily to investors. Tables A3 and A4 in the Appendix A provide more results from the municipal survey about the municipal response to abandonment and the priorities municipalities have set for addressing the issue. In addition, in Appendix B we describe how we reviewed the Puerto Rico Municipal Code (2020) to evaluate the policies regulating the acquisition and disposition of abandoned properties.

Effect of Collective Action on Participants

Survey respondents who had participated in collective action to transform abandoned spaces stated that their actions had resulted in a number of positive community-level outcomes, including more social or cultural events (65%) and more space to do exercise or organized sports (62%). Furthermore, respondents answered that the transformation of abandoned spaces into community spaces had resulted in them knowing more of their neighbors. (See Table A5 in the appendix for the full results of the community-based survey.)

Across all communities, nearly two-thirds of respondents felt that the amount of abandonment in their neighborhoods impacted their feelings of pride, happiness, and their sense of community. Respondents who participated in collective action were even more likely to feel abandonment affected their pride, happiness, and sense of community, with nearly 76% agreeing with this statement. Given the overwhelming amount of research that links self-efficacy, social capital, community agency and place with public health outcomes (Kawachi & Berkman, 200014), including and most strikingly life expectancy (Frederick et al., 201915), these emotions and perceptions are almost assuredly impacting the public health profile of these neighborhoods. Further research is needed to explore those pathways, but this finding demonstrates that place-based collective action does impact social capital, which other researchers have found to be crucial to disaster preparedness, response, and recovery (Talbot et al., 202016; Hernández et al., 201817).

Conclusions

Public Health Implications

Our study suggests several implications for public health practice and policy, most of which are aligned with needs identified by communities and municipalities. Following the guidance in the CONVERGE training module, The Public Health Implications of Hazards and Disaster Research, we derived the following implications from our study (Natural Hazards Center, 202218).

Strengthen Municipal Institutions to Address Abandonment

Our findings suggest that strengthening municipal institutions is an effective way to mitigate abandonment. As stated above, 90% of property owners who appeared after receiving a citation from the municipal code enforcement office engaged in abatement activities. This demonstrates that it is possible to hold people accountable for the damage their properties do to community health. Our data also demonstrated that property owners who engaged in abatement were more likely to pay their tax debts (55%) than those who did not (40%). If researchers are able to show that engaged property owners pay their back taxes, this could be used to encourage municipalities to strengthen their code enforcement programs as a way to improve both tax collection and public health.

Unfortunately, our study showed that municipal code enforcement programs are under-resourced and under-staffed in most Puerto Rican municipalities. According to the municipal survey, only 36.2% of code enforcement program staff were career or contract-based professionals. The majority of code enforcement workers—55.3%—were temporary staff whose positions change each electoral cycle (note that the total doesn't add up to 100% because non-answers where excluded). Permanent, dedicated code enforcement programs, as well as increased prioritization and funding of this municipal responsibility, is needed to expand the public health workforce and ensure continuity and effectiveness of these efforts.

While our study shows that municipal code enforcement programs can work, it also demonstrates that these municipal programs are not enough to entirely address the problem of abandonment. According to our community-based survey, as many as 57% of abandoned properties continued in a state of abandonment after being cited for code infractions due to challenges in locating owners or getting legal permission to take over the property. Municipalities need more resources and new community-based strategies to address these persistently abandoned spaces, otherwise they will continue to perpetuate environmental, health, and safety risks.

Add Abandonment to Disaster Response and Recovery Plans

Our study confirms that abandonment is likely to increase post-disaster and that concentrated abandonment is associated with negative health outcomes. We also found, as have previous studies, that post-disaster abandonment most frequently occurs in marginalized communities of color, working class, or poor communities. Therefore, future public health disaster response and recovery efforts should include resources and guidance for local municipalities and community groups about how to locate abandoned spaces and document their environmental, social, and health risks. It is also important to include mechanisms for tracking vacancy trends in disaster recovery programs, because, as our study has shown, hypervacancy is an indicator of a community which may be experiencing high concentrations of abandonment and their associated health and environmental risks, especially in the disaster-affected regions.

Based on our findings, we recommend that public health and other officials responsible for emergency preparedness incorporate programs that train municipal governments and community groups to identify, monitor, and transform abandoned spaces into their disaster plans. They should also earmark disaster recovery funds for community-based inventories of abandonment and community-led transformation of abandoned spaces.

Use Community-Based Neighborhood Improvement Programs in Disaster Recovery Efforts

Our study suggests that community-based inventories and community-led transformation of abandoned spaces are needed to effectively address abandonment. As we stated in the findings, community-based inventories were more thorough in documenting environmental, health, and other risks associated with abandoned properties than traditional complaint-based municipal code enforcement programs. Moreover, the properties identified through community inventories were also more likely to have been abandoned for a longer amount of time. These two results suggest that code enforcement programs should be built around community-based inventories.

Additionally, our results suggest that community-led transformation efforts are more likely to result in lasting benefits for the community. These efforts reduce negative population health outcomes by removing environmental health risks. But they also benefit community members in other ways via increased social interaction. The study also points to potential ways that participating in community-led action to improve one’s neighborhood may serve to increase protective health factors, including providing opportunities to socialize, build social capital, and increase positive health behaviors, such as eating more produce and exercising more.

Strengths and Limitations

This study design had several strengths. These include the interdisciplinary team with a transdisciplinary method of collaboration, the solutions-focused aspect of the convergence framework, and the reciprocity with communities. Another strength we would like to highlight is the systems framework that we used to develop the project. In more traditional epidemiological studies, there is sometimes an attempt to isolate causality between factors, events or phenomenon under study and specific health outcomes. This linear thinking was avoided by situating the study within an ecosocial theoretical approach, starting from a recognition that the relationships being explored exist within, and are thus changing and changed by, multiple levels of the ecosocial system that Puerto Rican communities are nested within.

The major limitations of this study were the short timeline and the challenges associated with fieldwork during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, we were not able to complete the two case studies we intended to conduct as part of this study, in part because public health measures related to numerous COVID-19 outbreaks prevented us from gathering for focus groups and other interviews. Our team hopes to complete this part of the study in the upcoming months and to publish the findings in a separate report.

Future Research Directions

Important lessons from Puerto Rico can be applied elsewhere, as abandonment is affecting communities across the United States. It is common knowledge that, due to climate change, disasters are increasing in both frequency and intensity across the world. It is also becoming clear recently that populations are declining across the world (Ryan, 201919). As these two global trends intersect, it is imperative that communities learn how to effectively address abandonment. Future research should include a comparison of place-based case studies exploring post-disaster changes in trends of abandonment and their health outcomes, as well as differing community-led strategies to transform abandoned spaces as part of larger emergency preparedness functions. Another important direction for further research is in understanding the economics of abandonment, mitigation, and transformation. Given the unequal distribution of abandonment, it is highly likely that unaddressed accelerating abandonment contributes to both rising spatial economic inequality and attendant entrenched geographic health inequities.

References

-

Eckstein, D., Künzel, V., & Schäfer, L. (2021). Global Climate Risk Index 2021. German Watch. https://www.germanwatch.org/en/19777 ↩

-

Roque, A., Pijawka, D. & Wutich, A. (2020). The role of social capital in resiliency: Disaster recovery in Puerto Rico. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 11(2): 204-235. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12187 ↩

-

Mallach, A. (2018). The empty house next Door: Understanding and reducing vacancy and hypervacancy in the United States. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/empty-house-next-door-full.pdf ↩

-

Klein, A. (2017). Understanding the true costs of abandoned properties. Community Blight Solutions. https://www.cityofmiddletown.org/DocumentCenter/View/883/Community-Blight-Solutions-Understanding-the-True-Costs-of-Abandoned-Properties-How-maintenance-Can-Make-a-Difference-6-14-18 ↩

-

Harrison, A. & Immergluck, D. (2021). Housing vacancy and hypervacant neighborhoods: Uneven recovery after the U.S. foreclosure crisis. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1945930 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d. *data.census.gov *[Data dissemination platform]. Retrieved July 10, 2022, from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/ ↩

-

Santiago, R., Lamba D., & Figueroa, E. (2022). Tracking neighborhood change in geographies of opportunity for post-disaster legacy cities: A case study of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/working-papers/tracking-neighborhood-change-in-geographies-opportunity-post-disaster ↩

-

Wang, K. & Immergluck, D. (2018). The geography of vacant housing and neighborhood health disparities after the US foreclosure crisis. Cityscape 20(2), 145-170. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/urban_studies_institute/41/ ↩

-

Krieger, N. (2012). Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: An ecosocial approach. American Journal of Public Health 102(5), 936–944. ↩

-

Benach J., Rivera, M., Muñoz, N., & Eliana, M. (2019). What the Puerto Rican hurricanes make visible: Chronicles of a public health disaster foretold. Social Science & Medicine 238, 112367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112367 ↩

-

Pinto, A. M., Ferreira, F. A., Spahr, R. W., Sunderman, M. A., Govindan, K., & Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I. (2021). Analyzing blight impacts on urban areas: A multi-criteria approach. Land Use Policy, 108, 105661. ↩

-

Peek, L. & Guikema, S. (2021). Interdisciplinary theory, methods, and approaches for hazards and disaster research: An introduction to the special issue. Risk Analysis, 41(7), 1047-1058. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13777 ↩

-

Etikan, I., Abubakar, S., & Sunusi, R. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11 ↩

-

Kawachi, I. & Berkman, L. (2000). Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In Berkman, L. & Kawachi I. (Eds). Social Epidemiology. (pp. 174-190). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Frederick, C., Hammersmish, A., & Gilderbloom, John. (2019). Putting ‘place’ in its place: Comparing place-based factors in interurban analyses of life expectancy in the United States. Social Science & Medicine 232, 148-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.047 ↩

-

Talbot, J., Poleacovschi, C., Hamideh, S. & Santos, C. (2020). Informality in Postdisaster Reconstruction: The role of social capital in reconstruction management in post–hurricane Maria Puerto Rico. Journal of Management in Engineering 36(6), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000833 ↩

-

Hernández, D., Chang, D., Hutchingson, C., Hill, E., Almonte, A., Burns, R., Shepard, P., González, I., Reissig, N., & Evans, D. (2018). Public housing on the periphery: Vulnerable Residents and depleted resilience reserves post-hurricane sandy. Journal of Urban Health 95(5), 703-715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0280-4 ↩

-

Natural Hazards Center. (2022, April 22). CONVERGE public health implications of hazards and disaster research training module: A demonstration webinar [Webinar]. University of Colorado Boulder. https://converge.colorado.edu/webinars/converge-public-health-implications-of-hazards-and-disaster-research-training-module-a-demonstration-webinar/ ↩

-

Ryan, B. (2019). Shrinking cities, shrinking world: Urban design for an emerging era of global population decline. In T. Banerjee & A. Loukaitou-Sideris (Eds.), The New Companion to Urban Design. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203731932 ↩

Alvarado, M., Carrasquillo, D., Gallardo, L., & Chopel, A. (2022). The Public Health Implications of Abandoned Spaces in Post-Maria Puerto Rico (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 25). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/the-public-health-implications-of-abandoned-spaces-in-post-maria-puerto-rico