Multi-Hazard Planning for Access and Functional Needs in the U.S. Territories and Hawaii

Publication Date: 2022

Executive Summary

Overview

Public health is increasingly intertwined with disaster management. The COVID-19 pandemic has generated a complex environment in which traditional planning resources for keeping people safe may also put them in harm’s way. Evacuation and shelter planning, especially for individuals with access and functional needs, must be better understood, integrated, and managed to reduce loss and to improve community resilience.

Research Questions

Our study investigates the following four questions about the evacuation and sheltering of individuals with access and functional needs in the U.S. territories and Hawaii: (1) Which public health agencies are responsible for multi-hazard evacuation and shelter planning for this population? (2) What plans and strategies are in place for reaching this population during evacuation and sheltering scenarios? (3) What planning resources exist to support public health agencies in these efforts? (4) What education and training do public health agencies need?

Research Design

This study develops an understanding of network structures and partnership models that enable cross-sector engagement and collaboration for multi-hazard evacuation and shelter planning. The study area includes Guam, American Samoa, the Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), and Hawaii. The research is transdisciplinary and convergence oriented, engaging public health, disability studies, urban planning, disaster management, media, and other disciplines in the research design process. The study gathers perishable data about the experience of public health and disaster management stakeholders who worked with individuals with access and functional needs during the pandemic. First, the team reviewed existing plans and strategies for disaster evacuation and sheltering to determine the extent to which they include multi-hazard guidance for individuals with access and functional needs. Second, through surveys, interviews, and focus groups with disaster management stakeholders, we produced a social network map of actors responsible for evacuation and shelter planning, a summary of resources deployed by those actors, and an assessment of their gaps in education and training.

Findings

The study finds that government agencies are primarily responsible for planning multi-hazard evacuation and shelters for individuals with access and functional needs. Universities, the private sector, and community organizations also play significant roles in educating the public about resources available for this population. All study areas had some form of evacuation and sheltering plan, some of which are standalone plans while others are standard operating procedures or guidance for mass care. Puerto Rico, the USVI, Guam, and Hawaii have updated evacuation, sheltering, and mass care guidance often by adapting for the local context from national-level guidance developed by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The most common resources deployed for evacuation and sheltering included testing and screening processes for COVID-19 and related safety measures in shelters; having a formal evacuation/sheltering plan; accessible methods to communicate COVID-19 changes in evacuation services or procedures to those with access and functional needs; nonprofit resources (technical assistance, outreach, support); and standard operating procedures that align with public health guidance and promote social distancing. Regarding education and training, the U.S. territories have a need for more training in community planning for disaster recovery, evacuation planning, Natural Disaster Awareness for Caregivers, climate change adaptation, hurricane awareness, coastal hazards assessment and planning, Disaster Awareness for Community Leaders, tsunami awareness, disaster debris management planning and small business continuity planning.

Public Health Implications

Study results offer insights on how state, territorial, and local governments can enhance the delivery of mass care and sheltering through updated planning guidance, increased resources, and education and training. Workforce development within public health can be strengthened by increasing opportunities for education and training for access and functional needs caregivers and care receivers. The study shows that agencies responsible for access and functional needs exhibit strong bonding (within networks) and bridging (between networks) social capital. However, linking social capital (across vertical gradients and hierarchies) between agencies should be strengthened so that trust can be built between government agencies and nongovernmental organizations directly serving individuals with access and functional needs. Healthy relationships across these networks are critical for cultivating community resilience. Finally, the study finds that the term “access and functional needs” might require deconfliction with “underserved populations” and “disabled populations.” These terms help to elucidate nuanced socioeconomic factors that make certain populations more vulnerable to poor disaster health outcomes. Clarifying which factors are captured by these terms may help to ensure planning is more inclusive and equitable.

Introduction

Disaster management and public health have become closely intertwined in recent years (Llibre-Guerra et al., 20201; Marliana et al., 20202; Mrduljaš-Đujić et al., 20213; Samy et al., 20214). Climate-related hazards, coupled with the pandemic and geologic threats, require disaster planners to manage multiple hazards at once. Public health workers are now more deeply involved with multi-hazard disaster response and recovery, which traditionally fell under the purview of disaster management. Evacuation and shelter planning, especially for vulnerable populations, must be better understood, integrated, and managed to reduce losses and to improve community resilience.

Literature Review

The decision to evacuate or not is an ethical dilemma in disaster management for which there is no easy solution. Existing research documents well-known challenges: individuals unwilling or unable to evacuate, insufficient transportation, congested road networks, shelters not being built up to code, and varied perception of risk leading to differences in protective action measures (Natural Hazards Center, 20205; Baker, 19916; Collins et al., 20217; Florido, 20188; Cava, 20189; National Disaster Preparedness Training Center [NDPTC], 201810, 2021a11, 2021b12; Quarantelli, 198013; Yasui and Numada, 202114). Research shows that only 15% of evacuees go to public shelters (NDPTC, 2018; Wu et al., 201315). During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the inability to successfully evacuate vulnerable populations led to unintended fatalities (Wu et al., 201216). Even so, successful evacuation of vulnerable populations can lead to unintended fatalities as well, such as in the case of Hurricane Rita that very same year (NDPTC, 2018; Whitfield, 201717).

Multi-Hazard Planning and Coordination Among Agencies

The COVID-19 global pandemic ensures that any hazard event now requires multi-hazard planning considerations. Thus, planning increasingly requires disaster managers and public health workers to lean on national guidance to facilitate cooperation between both fields. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) guide COVID-19 Supplement for Planning Considerations: Evacuation and Shelter-in-Place (2020) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance Going to a Public Disaster Shelter During the COVID-19 Pandemic (202018) are existing resources for disaster managers and planners to update evacuation and sheltering procedures with attention to public health equity. Screening and testing, providing personal protective equipment, alternative shelter locations, social distancing, sheltering in place, and risk communication have been identified as top strategies and resources for planners (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], n.d.19; FEMA, 201020, 201821, 202122; Kim et al., 2021a23; Kim, 202124; Kim et al., 202025; Federal Highway Administration, 200926; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 202127; National Cooperative Highway Research Program, 2020: 4328; Prep It Forward, 202229; Renne et al. 201130; Sanchez & Brown, 201331). Localized versions of national multi-hazard planning guidance have been adopted by states and counties (California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services [Cal OES], 202032; City and County of Honolulu, 202133; Indiana State Department of Health, 202134).

Access and Functional Needs as an Area of Focus

Some state-level guidance increasingly places emphasis on cultural competence and capacity building for disaster managers who work with individuals with access and functional needs (Cal OES, 201935; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 202036; Solano County, 201737). The term “access and functional needs” refers to individuals who may need additional assistance due to temporary or permanent conditions, which may limit their ability to act in an emergency (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 202138; Kuran et al., 202039; NDPTC, 2021b; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). This includes but may not be limited to individuals with a physical, developmental, or intellectual disability; individuals with economic disadvantage; older adults; children; pregnant women; individuals with limited English proficiency or limited literacy; individuals with a chronic medical condition; and individuals with mobility challenges. Recent research also shows that COVID-19 morbidity and mortality are linked to access and functional needs (Steinman et al., 202040; Turk & McDermott, 202041; Whytlaw, 202142). For instance, persons with intellectual disabilities have died from COVID-19 at a rate two or more times higher than those without, and eight out of 10 U.S. COVID-19 related deaths are adults 65 years and older (FEMA, 202043).

Legal requirements set forth by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and other applicable federal, state, and local laws or executive orders, require emergency managers and planners to identify the needs within the community and the resources needed to fully support individuals with access and functional needs during the implementation of protective actions (FEMA, 2020). Given the disproportionate risk to these individuals during disasters, resources, education, and training are needed to reduce their risk and vulnerability.

Evacuation, Sheltering, and Public Health Guidance in an Island Context

Many disaster research studies focus on urban and rural areas in continental locations (Botzen et al., 202244; Cohn et al. 200645; Huang et al., 201646; Meyer et al., 201847; Wu et al., 2013). One limitation of these studies is that they tend to privilege self-evacuees who have the access to transportation (Kim et al., 201548; Kim et al., 201849). Fortunately, island evacuation and sheltering strategies have received more attention in disaster research in recent years (e.g., United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 201650; Brown, 200151; Collins et al., 202252; Kelman, 200853; Putra & Mutmainah, 201654; Schultz et al., 201955; Schnall et al., 201956; Yuzal et al., 201757). Various studies on the 2009 earthquake-tsunami in American Samoa showed that income level, social vulnerability, and risk perception are key drivers of evacuation behavior in island contexts. For example, Apatu et al. (201658) found that higher income households were more likely to evacuate than lower-income households in American Samoa during the 2009 earthquake-tsunami. Okumura et al. (201159) found that most people evacuated by foot, which can be more difficult for older adults or individuals with mobility challenges. Lindell et al. (201560) found that people who had prior natural hazards awareness had higher risk perception about the event, but this did not necessarily affect their likelihood to evacuate.

The response to hazards in island communities also tends to be distinct from practices in the continental United States. For example, strangers are more likely to share resources among each other during disasters (Kim et al., 2021b61). This common prosocial behavior means that islanders are more likely to evacuate to the home of another individual, even a stranger, than to evacuate to a shelter managed by government agencies or organizations. COVID-19 also appears to have made evacuation and sheltering more difficult. Studies in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), for example, showed that public shelter usage would likely decrease when affected individuals were faced with COVID-19 threats (Avilés Mendoza et al., 202162; Corbin, 202163; Collins et al., 2021; Collins et al., 2022; Kim et al., in press64). Other research has demonstrated that shelter and transportation options, financial capacity, mental health services, and disaster management resources are often limited in the island territory contexts (Kim et al., 2015; Parr et al., 202065; Swiatek et al., 202166; Webster et al., 202267). However, studies have not yet focused on individuals with access and functional needs in island communities and the challenges they face when navigating evacuation and sheltering decisions during multi-hazard events.

Research Design

Research Questions

This study investigates four research questions about the evacuation and sheltering of individuals with access and functional needs in the U.S. territories and Hawaii:

- Which public health agencies are responsible for multi-hazard evacuation and shelter planning for this population?

- What plans and strategies are in place for reaching this population during evacuation and sheltering scenarios?

- What planning resources exist to support public health agencies in these efforts?

- What education and training do public health agencies need?

Study Site Description

The study includes Guam, American Samoa, the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands , Puerto Rico, USVI, and Hawaii. While Hawaii is a state and not an island territory, we included it in this study for comparative analysis, given that it is also an island jurisdiction located outside of the contiguous United States and shares similar planning and resource challenges, cultural practices, and value systems with other islands due to its geography.

Data Collection Methods and Procedures

The study gathers perishable data about the experiences of public health and disaster management stakeholders who work with individuals with access and functional needs. As public health restrictions for travel, masking, social distancing, and proof of vaccination begin to relax worldwide, we believe it is critical to capture the experiences and attitudes of public health and disaster management workers earlier in the pandemic when perceived and actual risk was significantly higher.

Our data collection activities involved the following: First, we analyzed existing documents, including state and local plans, policies, and budgets for disaster evacuation and sheltering, mass care, and preparedness in order to determine to what extent those plans and strategies included multi-hazard guidance. Second, we distributed a survey hosted on the Qualtrics platform to a purposive sample of disaster management stakeholders, public health workers, and local disaster researchers in the U.S. territories and Hawaii. Finally, we conducted 17 follow-up interviews and one focus group with respondents who indicated consent and interest in further discussion. The survey and interviews were carried out between January 31 and March 11, 2022.

The research was conducted within the convergence framework (Peek et al., 202068) by working across disciplinary boundaries, and ensuring that research participants also benefit from the final outputs of the project. The research team consisted of researchers from urban and regional planning, emergency management, policy, engineering, transportation safety, coastal science, and media. The study engaged individuals in public health, disability studies, and disaster management. All research team members are residents of Hawaii.

Survey

The survey was designed by the research team and made available in English and Spanish. The survey measures were informed by the CDC Access and Functional Needs Toolkit Partner List (CDC, 2021, pp. 49-50). Questions about agencies responsible for evacuation and shelter planning for individuals with access and functional needs were designed using the partner list in this Toolkit. Survey questions regarding education and training gaps were informed by existing course topics available in the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center (NDPTC) course curriculum. The survey tool was pre-tested by graduate students at the University of Hawaii before being distributed to participants. After pre-testing, survey questions were edited for relevance, strength of connection to research questions, and grammatical and spelling errors. The full survey instrument (in English and Spanish) is available in Appendix A.

We distributed the survey via e-mail and used our networks with partners in the wider emergency management community, agencies and organizations that work directly with access and functional needs populations in the study sites, and institutions that provide them with social or legal services or that advocate on their behalf. The partnerships we used to distribute the survey included the Pacific Risk Management ʻOhana (PRiMO) network, Social Science Extreme Events Network (relevant contacts in the U.S. territories), the National Domestic Preparedness Consortium, the National Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies, chairs of the Volunteer Organizations Active in Disasters (VOAD), the Red Cross, and the FEMA Caribbean and Pacific offices for Disability Integration and Coordination and Emergency Support Functions. We also asked our partners to forward the survey to relevant contacts in their networks and to volunteer for follow up interviews.

Participants were sampled based on the following criteria: (a) they were residents of a U.S. island territory or Hawaii and (b) they worked in disaster management, disaster risk reduction, or related field. The total number of survey respondents was 95. As described below, our research participants also included 17 interviewees and 15 focus group participants. Altogether, 127 individuals participated in this study, including 76 from the U.S. territories and 51 from Hawaii. Table 1 shows the organizational affiliations, education, and gender identities of the research participants.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Research Participants

(n=76) |

(n=51) |

||

| Organizational Affiliation |

Government agency | 39.53 | 24.00 |

| Hospital or healthcare organization |

4.65 | 4.00 | |

| Nongovernmental organization |

11.63 | 12.00 | |

| University or educational institution |

20.93 | 16.00 | |

| Community-based organization |

4.65 | 16.00 | |

| Faith-based organization |

2.33 | 12.00 | |

| Private company/ business |

2.33 | 4.00 | |

| Insurance or financial institution |

2.33 | 0.00 | |

| General public (non-specified) |

9.30 | 12.00 | |

| Other | 2.33 | 0.00 | |

| Education | Less than high school |

2.33 | 0.00 |

| High school (includes equivalency) |

0.00 | 12.00 | |

| Some college, no degree |

9.30 | 4.00 | |

| Associate degree | 2.33 | 4.00 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 27.91 | 28.00 | |

| Graduate degree | 58.14 | 52.00 | |

| Gender | Female | 64.44 | 48.00 |

| Male | 33.33 | 52.00 | |

| Prefer not to respond |

2.22 | 0.00 | |

Interviews and Focus Group

Survey respondents who agreed to a follow-up were selected for in-depth interviews. Some interviews were conducted with individuals who did not complete the survey but who were part of a purposive sample of individuals who indicated interest in participating in the study. The total number of interviewees was 17. We conducted the interviews virtually using Zoom and the full list of questions we asked participants can be found in the Interview Protocol in Appendix B. Interviewees included members from emergency management at the state, county, and territory levels; leaders of organizations that provided direct services to those with access and functional needs; and representatives from Centers for Independent Living, Offices of Aging, Councils on Developmental Disabilities, accessibility boards, self-advocacy networks, and individuals who identified with one or more of the CDC access and functional needs categories.

We held one focus group by invitation at a special Post-Pacific Rim Conference in Honolulu, Hawaii, focused on disability integration into emergency management. There were 15 participants in the focus group, which included emergency managers who specialized in disability integration from California, American Samoa, Guam, the Mariana Islands, and Hawaii. Two members of the FEMA Region 9 Office of Disability Integration and Coordination also attended. Two participants disclosed that they had a disability. The focus group discussion centered on education and training gaps for access and functional needs in evacuation and shelter planning in the U.S. territories.

Study Participation by Island

Table 2 shows the number of study participants across all data collection methods by their island of residence. The majority of survey, interview, and focus group participants were from Hawaii. All U.S. territories were also represented in this study.

Table 2. Research Participants by Island

Respondents |

Participants |

Participants |

Participants |

||

| Hawaii | |||||

| American Samoa | |||||

| Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands | |||||

| U.S. Virgin Islands | |||||

| Puerto Rico | |||||

| Guam | |||||

| Other | |||||

| Total |

Data Analysis

Survey Analysis

Survey data was analyzed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software for tabulation and descriptive/inferential statistical insights. Background questions on age, gender, ethnicity, and occupation were used to compare survey respondents to the census distribution for statistical control. Data were de-identified for statistical analysis in Qualtrics before analysis in SAS. Contact information was used for follow-up interviews and to share findings.

A logistic regression was developed to evaluate survey results. The survey was designed with the intention of questions containing binary predictor variables (Yes or No) to be able to predict the likelihood of an event. In this case, the survey was designed to evaluate the likelihood of an individual’s perception of evacuation preparedness. The model examined the relationship between respondent perception of evacuation preparedness (a binary predictor variable) and seven categorical response variables. These included: no preventive measures (prevention), No COVID-19 testing within the shelters (testing), respondents 61 years or older (age), No graduate education (education), being in the U.S. territories (territory), being in a nongovernment job (nongovernment), and being female (female). The logistic regression is identified by the following equation:

where p is the probability, p/1 - p is the odds ratio, and β is the regression coefficient associated with the response variables. The following variables were significant at the 0.05 confidence level: having no preventive measures (0.0129), having no COVID-19 testing in shelters (<.0001), respondents aged 61 years and older (0.0128), respondents without a graduate degree (0.0266), and the respondents from the U.S. territories (0.0218). Neither affiliation with government agency nor gender impacted the significance of the model.

Survey Limitations

Since our survey sample size was skewed toward individuals living in Hawaii with higher-education degrees, our analysis included various statistical tests to determine the difference in survey population responses between Hawaii and the U.S. territories, as well as to determine the significance of variables such as educational attainment, as displayed in the tables below. For example, Table 3 displays the results of a Wald Chi Square test that showed “having no graduate degree” having a moderate likelihood of being a significant predictor variable.

Table 3. Logistic Regression Analysis Results

| Intercept | ||||

| No preventive measures (prevention) |

||||

| No COVID-19 testing in shelters (testing) |

||||

| 61 years and older (age) |

||||

| No graduate degree (education) |

||||

| U.S. territories (territories) |

||||

| Nongovernment jobs (nongovernment) |

||||

| Female |

The dependent variable in our model is “low perception of evacuation preparedness” (i.e., a score of 5 or lower in survey question number 19). The estimate value tells us how appropriate a predictor (coefficient size) is and its direction of association (positive or negative). The Wald Chi Square test can tell us which model variables are contributing something significant. The higher the number, the more likely an explanatory variable in a model is significant. The odds ratio is a measure of the strength of association with an exposure and an outcome. In our survey, it tells us the likelihood of an outcome. For example, having no preventive measures in place for COVID-19 made it 11 times more likely for individuals to have a lower perception of preparedness. The p-value tells us if the dependent variable is significant (i.e., within the 95% confidence interval). If the p-value is 0.05 or lower, the result is significant, but if it is higher than 0.05, the result is not significant.

Table 4 shows the results of a t-test for differences in responses between participants in the study area. A t-test is a type of inferential statistic used to determine if there is a significant difference between the means of two groups being tested.

Table 4. T-Test Results

Deviation |

Error |

|||||||

| Types of resources to support multi-hazard evacuation and sheltering for those with access and functional needs (Question 8) | ||||||||

| Hawaii | ||||||||

| U.S. Territories | ||||||||

| Organizational preparedness for evacuation and sheltering (Question 19) (10 being the most prepared) | ||||||||

| Hawaii | ||||||||

| U.S. Territories | ||||||||

Generally, any t-value greater than +2 or less than – 2 is acceptable. The higher the t-value, the greater the confidence we have in the coefficient as a predictor. Low t-values are indications of low reliability of the predictive power of that coefficient. The Pr(>|t|) column represents the p-value associated with the value in the t-value column. If the p-value is less than a certain significance level (e.g. α = .05) then the predictor variable is said to have a statistically significant relationship with the response variable in the model. This table displays the level of differences in survey responses between Hawaii and the U.S. territories.

Interview and Document Analysis

Interviews and focus groups were transcribed into Microsoft Word, translated into English, and manually coded with regard to content alignment with the study’s research themes. The codebook we used to analyze the interview and focus group data is available in Appendix C. Initially, one coder reviewed and coded the transcriptions. To establish intercoder reliability, other research team members then reviewed the initial coding and provided feedback on agreement (i.e., whether the emergent codes aligned with content, and whether the codes aligned with the overall research question themes). Adjustments to the codebook were made accordingly, based on group consensus. Data from document analysis, surveys, and interviews were triangulated by systematically sorting data into frequency tables organized by research question. Insights for the report were gleaned from synthesis of information from these tables.

Ethical Considerations, Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Considerations

This study (Protocol #2021-00781) was approved as exempt from federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants by the University of Hawaii Office of Research Compliance on October 7, 2021. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study. Individuals were not offered compensation for participating in any data-gathering activities. The research team will share results with participants near the close of the study through dissemination of a final report to collaborators and partners as well as through a public webinar event convening emergency managers and study participants across government, nongovernmental organizations, academia, and communities to share findings in a pre-hurricane season briefing. In addition, we will create accessible infographics and one-page summaries of the study results to circulate to study participants and other interested parties. The research team actively engaged in ethical reflexivity throughout the course of the project, taking into consideration our role in the research process to ensure that the project continues to pose less than minimal risk (i.e., no known physical, emotional, psychological, reputational, or economic risk) to those who participated in the study.

Findings

Agencies Responsible for Multi-Hazard Evacuation and Shelter Planning

Table 5 displays all agencies and organizations that study participants identified as responsible for multi-hazard evacuation and shelter planning for individuals with access and functional needs in the U.S. territories and Hawaii. Study participants overwhelmingly responded that government agencies were primarily responsible for planning for this population. Table 5 outlines the specific government agencies that respondents identified for each island.

Table 5. Organizations Responsible for Evacuation and Shelter Planning for Individuals With Access and Functional Needs

| Hawaii | Government: FEMA Pacific Area Office; Hawaii Emergency Management Agency (HI-EMA); Office on Ageing; Department of Transportation; City and County of Honolulu Elderly Affairs Division; Department of Health and Human Services; Department of Education Special Education Group; Disability and Communication Access Board; Developmental Disability Council; State Developmental Disabilities Council; ESF 6 – Mass Care Core Team; Parks and Rec; Medical Reserve Corps; Hawaii State Council on Developmental Disabilities; County-Level Emergency Management Agencies Nongovernmental organizations: Kupuna Collective; American Red Cross; Anaina Hou Community Park (Kauai North Shore Resilience Hub); Language Access Board Pacific Gateway Center; Special Parent Information Network (SPIN); Leadership Disability Achievement in Hawaii (LDAH); Self-Advocacy Advisory Council; Centers for Independent Living University: University of Hawaii Center for Disability Studies Community-Based Organizations: Hawaii Hazards Awareness and Resilience Program (HHARP); condo associations; Cross Island Community Resilience Network; Island Preparedness Group |

| Guam | Government: Guam Homeland Security/Office of Civil Defense; Public School Systems; Public Assistance Office; Governor’s COVID-19 Task Force; Department of Community and Cultural Affairs; Board of Education |

| Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands | Government: Public School System; Homeland Security and Emergency Management Office; Public Assistance Office; Governor’s COVID-19 Task Force; Department of Community and Cultural Affairs; Board of Education; Department of Fire and Emergency Medical Services; Commonwealth Office of Transit Authority; Department of Public Safety Nongovernmental organizations: Karidat Social Services; Micronesian Legal Services; American Red Cross; Legal Aid Private sector: Commonwealth Healthcare Corporation Community-Based Organizations: Disability Network |

| American Samoa | Government: Territorial Emergency Management Coordinating Office; Office of Protection and Advocacy for Disabilities; Department of Health and Human Services; Department of Education; Office of Disaster Assistance and Petroleum Management Nongovernmental organizations: American Red Cross University: American Samoa Community College University Center for Excellence on Developmental Disabilities (UCEDD) |

| Puerto Rico | Government: Ombudsman for disabilities; Departamento de la Vivienda; Puerto Rico Emergency Management Agency (PREMA); Departamento de Salud; Departamento de la Familia; Municipal Offices for Emergency Management Nongovernmental organizations: Movimiento para el Alcance de Vida Independiente (MAVI); American Red Cross Universities: University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras Program in Public Administration and Social Service |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | Government: Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency (VITEMA); Department of Human Services; FEMA Office of Disability Integration Nongovernmental organizations: American Red Cross Universities: Virgin Islands University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities |

Table 5 also summarizes the other nongovernmental, educational, and community-based groups organizations which are involved in planning processes. For example, study participants were aligned in identifying similar types of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including the Red Cross, advocacy networks, centers for independent living, legal aid, social services, and the Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD). In-depth interviews confirmed that NGOs in the study area were essential resources for their communities. For example, the Puerto Rican nonprofit, Movimiento para el Alcance de Vida Independiente (MAVI) (Independent Living Outreach Movement, in English) a, promotes the philosophy of independent living and develops skills in people with disabilities so that they take control in making decisions about their lives. Study participants who worked for government agencies in Puerto Rico pointed to MAVI as a critical partner that identifies and advocates for access and functional needs within the community. Similarly, the Kūpuna Collective, Leadership for Disability Achievement in Hawaii, and Self-Advocacy Advisory Council are Hawaii-based nonprofit organizations that coordinate with government agencies and aim to improve access to resources for vulnerable populations. The Self-Advocacy Advisory Council is also plugged into nation-wide, community-organized advocacy networks for people with access and functional needs such as the Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies, which is led by individuals with disabilities (Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies, 201869).

Study participants working for government agencies noted that fostering relationships with NGOs that work directly with individuals with access and functional needs is essential for risk communication with those most vulnerable in disasters. Still, there is room for improvement. One interviewee who works for a center of independent living and who responded to the Kilauea volcanic eruption in the County of Hawaii said, “The awareness [of who is responsible] is there, but the connection is not.” During the Kilauea response, this interviewee was responsible for identifying shelter options for the elderly, a population which, according to our survey results, is nearly eight times more likely to feel unprepared for evacuation and shelter. She remembers:

I went to the shelters and…their registry didn’t capture disability. Access to shelters was difficult—security was so high at the time. It was difficult to find the right contact from FEMA or Red Cross. People rotated, so it was hard to stay in touch.

The interviewee stated that pre-established relationships, including contracts with transportation service providers for individuals with access and functional needs, would have helped her identify shelter options more efficiently.

Academic institutions also play a role in educating the public about resources for individuals with access and functional needs. University of Hawaii Center for Disability Studies, American Samoa Community College University Center for Excellence on Developmental Disabilities (UCEDD), and the Virgin Islands University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (CEDD) were mentioned as resources that study participants used for multi-hazard evacuation and shelter planning. In addition, study participants also identified private sector actors, such as the Commonwealth Healthcare Corporation in the Mariana Islands, condo associations, and hotels.

Lastly, study participants emphasized that community-based organizations (CBOs) play an important role as stakeholders. In our study, we distinguish CBOs from NGOs. The former tend to be informally organized, such as neighborhood watch groups. NGOs tend to be more formally organized and incorporated as tax entities. Both can be concerned with the well-being of people and society. In Hawaii, there are multiple CBOs that organize to exercise plans, identify needs, and build relationships during non-disaster periods to care for those with access and functional needs. The Island Preparedness Group, Hawaii Hazards Awareness and Resilience Program, and Cross-Island Community Resilience Network are examples of self-organized groups at the neighborhood or community level who meet regularly to discuss disaster risk reduction for the most vulnerable members in their communities (Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, 2022a70, 2022b71). These groups are a form of civic engagement for disaster preparedness that operate outside of government agencies but sometimes sync up with government planning efforts. While our deeper dives were limited to CBOs in Hawaii, CBOs also exist in the U.S. territories and play similar roles in terms of bringing communities together for disaster preparedness. The study also found that individuals who work for government agencies sometimes donate their disaster management knowledge, skills, and time to community organizations.

Planning for Multi-Hazard Evacuation and Sheltering During COVID-19

All study areas had some form of evacuation and sheltering plan, some of which are standalone plans while others are standard operating procedures or guidance for mass care. The study participants reported that several public health measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 had been updated in their evacuation and sheltering plans. The most common measures added to plans were social distancing, protective actions (i.e., masking and handwashing and disinfecting common areas), and vaccination.

Plans were less likely to include the following strategies: testing or screening measures, quarantining individuals who displayed COVID-19 symptoms, reducing shelter capacity, expanding shelter site options to include places like schools or hotels, and sheltering in place. Other strategies suggested by study participants for future plans included reducing overall shelter capacity; spacing out cots and bedding; using smaller locations as shelters to avoid mass sheltering options; providing interpretation and translation services at shelter locations for those who are deaf or who have limited English proficiency; packing masks in “go” bags; and expanding transportation options for those who do wish to evacuate (e.g. pick-up services from care centers). In our survey results, we found that those who come from jurisdictions with no preventive measures felt nearly 12 times less prepared for evacuation and shelter planning. Those who came from jurisdictions that had no COVID-19 testing in shelters felt nearly 27 times less prepared for evacuation and shelter planning.

By default, the islands follow CDC and FEMA guidance on preventing the spread of COVID-19 during evacuation and sheltering. Puerto Rico, the USVI, Guam, and Hawaii have gone beyond this step and updated their evacuation and sheltering plans by adapting many elements in the CDC and FEMA national-level guidance to local context and need. For example, as of March 2022, the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency (2022c72) and the Puerto Rico Emergency Management Agency were updating their Emergency Support Function #6 (Mass Care, Emergency Assistance, Housing, and Human Services) plan to include COVID-19 protocols and best practices. Puerto Rico’s experience in Hurricane Maria in 2017 heavily influenced the island’s proactive planning measures. One interviewee from Puerto Rico said, “We’ve learned a lot from Maria, especially with expanding messaging to disabled populations. We’ve learned from mistakes, but we are way, way better than we were in Maria.”

The USVI recently completed an exercise involving evacuation and sheltering to train disaster managers on the Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency’s newly updated guidance on hurricane preparedness during a global pandemic (Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency, 202173).

Some interviewees shared that multi-hazard protocols can sometimes be ad hoc without having been formally written into plans. Most territory- and state-level guidance focuses first on reducing risk from the natural hazard (e.g., a tropical cyclone) first, then mitigating COVID-19 risk during an evacuation and sheltering scenario. For instance, one emergency manager noted:

We only have so much space in shelters for tropical cyclone events. We wouldn’t have enough staffing. None of that is really codified. We would make operational, on-the-fly adjustments for how to manage the situation…[I]t’s better to survive the storm and get COVID-19 than not take action to protect yourself from the storm.

Study participants noted that multi-hazard guidance should be further developed to help individuals with access and functional needs understand how to prioritize protective action measures in different combinations of concurrent events (e.g., a hurricane and pandemic, a volcano and hurricane). Although more specific strategies to mitigate multi-hazard risk for access and functional needs populations still need to be incorporated into evacuation and shelter plans, study findings illustrate show that some strategies have already been put into place as safety measures for access and functional needs populations.

Guidance Needed for Households Sheltering in Place

Study participants described how sheltering in place was the preferred strategy for populations with access and functional needs in the islands during the COVID-19 pandemic. One interviewee explained, “In the Pacific, we take care of our own.” Multigenerational households and a baseline culture of sharing resources lead to a preference for sheltering in place during disaster events to not separate families and to not abandon care of individuals who may have mobility challenges or who have chronic medical conditions. At the same time, multi-hazard guidance for sheltering in place for those with access and functional needs is underdeveloped. There was consensus among interviewees that more guidance for individuals with access and functional needs sheltering in place should be developed for lockdown situations, especially regarding providing sufficient test kits to multigenerational households, transportation services, food security planning (Kupuna Food Security Coalition, 202274), telehealth, psychosocial support, and communications access.

Planning Resources

Table 6 shows resources at the territory, state, or local level to support multi-hazard evacuation and shelter planning for those with access and functional needs. As the table shows, study participants identified the most commonly identified COVID-19 planning resources as incorporating testing or screening processes for COVID-19 into sheltering plans; having a formal evacuation/shelter plan; accessible methods to communicate COVID-19 changes in evacuation services or procedures to those with access and functional needs; nonprofit resources (technical assistance, outreach, support); and standard operating procedures that align with public health guidance and promote social distancing. In American Samoa, study participants said the most commonly identified resource was having a formal evacuation and shelter plan. In the Mariana Islands, Guam, and Puerto Rico, study participants said the most commonly identified resource was including testing and screening processes for COVID-19 in shelter plans to implement safety measures in shelters. In Hawaii study participants said the most commonly identified resource was having accessible methods to communicate COVID-19 changes in evacuation services or procedures to individuals with access and functional needs. Lastly, in the USVI, study participants said the most commonly identified available COVID-19 planning resources were testing and screening processes; having a formal evacuation and shelter plan; and evacuee intake procedures include protocols that align with public health guidance and promote social distancing.

Table 6. Percentage of Respondents Indicating Planning Resources Are Available for Multi-Hazard Evacuation and Sheltering of Individuals With Access and Functional Needs

(n=15) |

(n=12) |

(n=4) |

(n=39) |

(n=8) |

(n=11) |

(N=95) |

|

| Testing/screening process for COVID-19 into your plans to implement safety measures in shelters | |||||||

| Additional capacity or sheltering facilities that can accommodate household pets with the necessary social distancing | |||||||

| Community demographic information to identify populations with access and functional needs | |||||||

| Accessible methods to communicate COVID-19 changes in evacuation services or procedures to those with access and functional needs | |||||||

| Formal evacuation and sheltering plan | |||||||

| Private or public funding to support those with access and functional needs | |||||||

| Nonprofit resources (technical assistance, outreach, support) | |||||||

| Planning guidance to account for COVID-19 risk in evacuation and sheltering scenarios (documents, online resources) | |||||||

| Updated accessible pre-scripted messaging to de-conflict COVID-19-related public health guidance (such as stay at home/safer at home orders) from incident-specific shelter- in-place or evacuation orders | |||||||

| Standard operating procedures that include public health and multi-hazard information for evacuation and sheltering | |||||||

| Evacuee intake procedures include protocols that align with public health guidance and promote social distancing | |||||||

| Evacuee procedures to handle the relocation and re-entry of evacuees from a shelter facility (both congregate and non-congregate) in the event of confirmed COVID-19 cases | |||||||

| Agreements with vendors that provide supplies or services to support evacuees in a COVID-19 environment | |||||||

| Additional or alternate evacuation routes to facilitate an evacuation in a COVID-19 environment before and after an incident | |||||||

| Other Resources |

In-depth interviews revealed more specific resources beyond formal protocols for evacuation and shelter planning. NGOs and caregivers providing direct services to individuals with access and functional needs pointed to self-advocacy networks at the local level (e.g., Hawaii’s State Council on Developmental Disabilities and American Samoa Community College’s University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities) and national level (e.g., the Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies) and critical resources for disaster preparedness. Self-advocacy networks which organize formally or informally have been able to ensure that individuals with access and functional needs can enlarge their circle of support (i.e., a group of people in someone’s life, whether paid or unpaid staff) and help the person in need to access emergency support. One interviewee noted, “It takes a village to protect the village. The more closely we can work with communities, the better.” The ethos of people within a community being their own best resource aligns with the prosocial values and behaviors in island communities during disasters.

Most survey respondents answered “No” when asked the question, “Do you think the existing resources are sufficient to support evacuation and shelter planning for those with access and functional needs” Indeed, study participants perceived several resource gaps created or amplified by the pandemic. Study participants said mental health and psychosocial support services were the largest of these resource gaps. Lockdown measures placed already-vulnerable populations in isolation. On islands like American Samoa, suicide rates increased during the pandemic. One emergency manager noted, “If [mental health and psychosocial support resources] are not addressed and included, we will have done a disservice. Access and functional needs populations may be more resilient for having overcome adversity, but isolation can also exacerbate their circumstances.” In places where cultures tend not to outwardly express pain, the need for psychosocial support may be barely visible yet critical.

Another problem identified by study participants involved the ways that resources for evacuation and shelter planning that were available before the pandemic were disrupted or blocked during extended periods of lockdown, social distancing, and limited large gatherings. For example, Hawaii Emergency Preparedness Fairs were put on hold. One emergency manager noted, “People with disabilities would normally come to events like the fair to connect with people they know and should know to build trust and understand who to go to during disasters.” Planning considerations might include telehealth resources or ways to expand circles of support for individuals with access and functional needs who choose to shelter in place.

Education and Training Needs

Education plays an important role in individuals’ perceived preparedness for evacuation and shelter. The majority of our study sample in the U.S. territories and Hawaii have higher education degrees. Our survey results find that individuals with no graduate degree were nearly five times more likely to feel less prepared for evacuation and shelter than individuals with graduate degrees. This finding points at the significant influence that education can play in shaping preparedness. Nearly half of the survey respondents stated that they were unaware of any education or training opportunities on the evacuation or sheltering of individuals with access and functional needs in their jurisdiction. This suggests that organizations tasked with these responsibilities lack awareness of trainings that are readily available on this issue. Through our literature review, in-depth interviews, and roles as researchers at the NDPTC, for example, we know that there are multiple training opportunities available for government agencies through FEMA, Red Cross, and other NGOs. Some training is meant to be internal to organizations but can be delivered to audiences outside of that organization. The NDPTC’s FEMA-certified Evacuation Planning Strategies and Solutions and National Disaster Awareness for Caregivers courses have been socialized and delivered in the study area. National Disaster Awareness for Caregivers focuses on providing guidance for those working with access and functional needs. Fifty percent of respondents indicated that they had attended an NDPTC training course in the past.

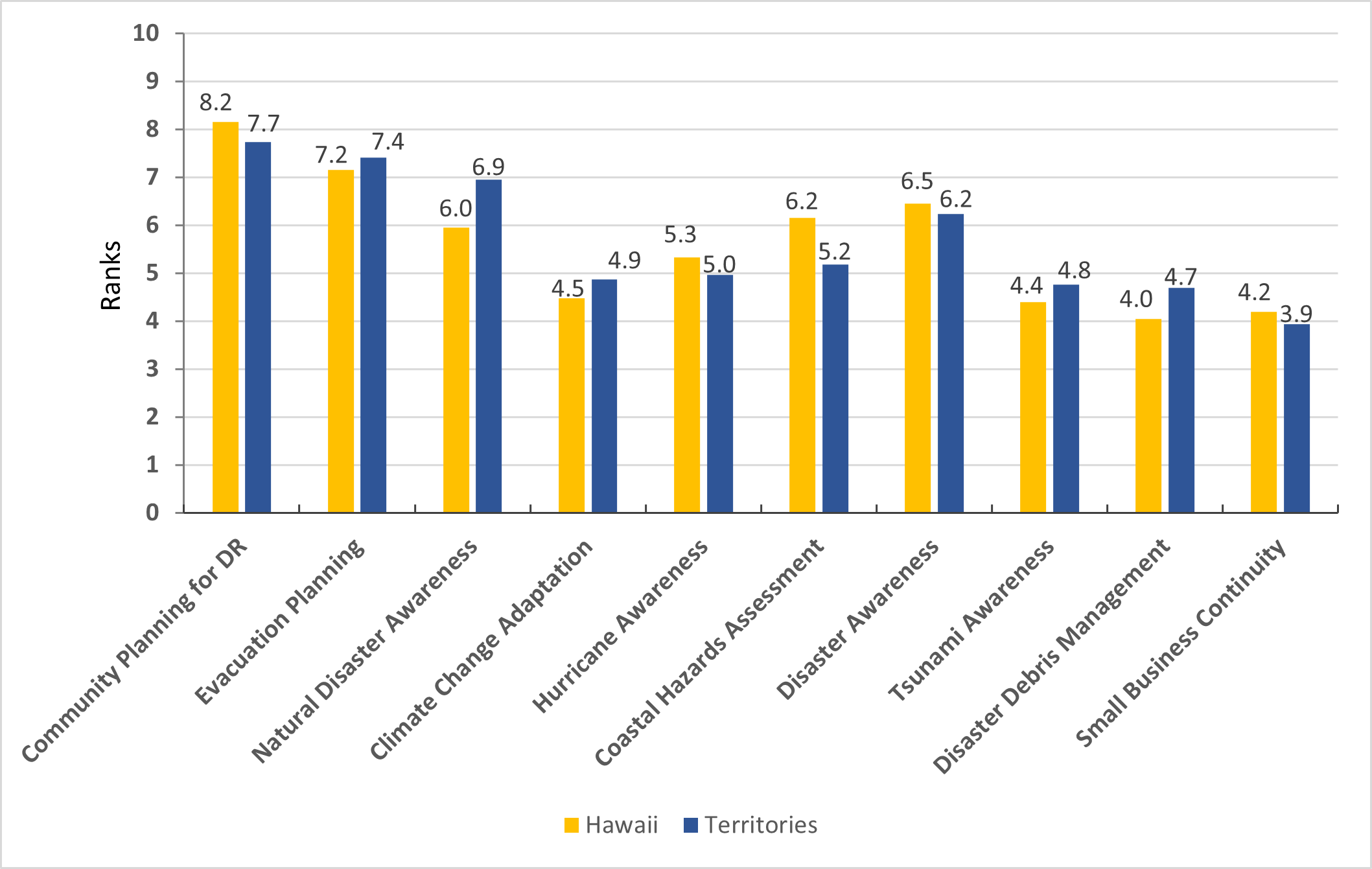

Figure 1 shows the education and training priorities that study participants identified. Trainings listed in the survey were curated based on relevance to multi-hazard events, evacuation and shelter, and guidance for caregivers. Results in Figure 1 compare responses in Hawaii to the territories to determine differences in training priorities between the jurisdiction types (i.e., territory and state). An overall assessment of the data shows, in order of priority, that the territories have greater need than Hawaii for training in Evacuation planning, Natural Disaster Awareness for Caregivers, Climate Change Adaptation, Tsunami Awareness, and Disaster Debris Management Planning. While Small Business Continuity ranked lower on overall training needs in the survey, it was identified as a priority in interviews with individuals from American Samoa, particularly for businesses owned by individuals with access and functional needs. American Samoa has a large veteran population who are disabled; this group is particularly vulnerable to business disruptions caused by disasters. This conclusion was confirmed in interviews. Interviewees suggested other training priorities, including psychosocial support to provide services for individuals with access and functional needs in isolation; telehealth training to deliver vaccine guidance, testing, and psychosocial support in virtual environments; and broadband resource guides to ensure digital access to virtual training and online services, particularly during lockdown. Territories like the Mariana Islands sometimes encounter connectivity challenges due to gaps in internet service provision. Basic broadband connectivity can sometimes be a barrier to receiving virtual training and can also be a barrier to accessing telehealth resources.

Figure 1. Training Needs, Ranked Highest to Lowest Priority

An example of an effective emergency preparedness course is Feeling Safe, Being Safe, an individual preparedness training from the California Department of Developmental Services (202275). This training was created by those with disabilities for individuals with disabilities. Families and caregivers of those with access and functional needs are also encouraged to attend Feeling Safe, Being Safe training events. The training model is inclusive of both caregivers and care receivers as agents of preparedness. Versions of this training have been adopted for island communities by the Self-Advocacy Advisory Council (202076) in Hawaii. The latest version of training materials includes guidance on COVID-19 safety measures and pre-planning guidance for evacuation. One interviewee shared an example of how evacuation guidance is implemented:

If we train a person with disabilities to pack a go bag, we don’t just teach them what goes in it. We make them pack it and ask if they can carry it. That way, if something happens, they know whether they themselves have the ability to carry that bag out the door safely. If not, we ask them to identify the right people in their circle to call when something goes wrong.

A “train the trainer” model empowers those who have taken the training–-who have access and functional needs–-to deliver the training to others with access and functional needs, building capacity and awareness through advocacy circles.

Conclusions

Public Health Implications

This study has several, public health implications, which we explain in detail below:

Adapt federal evacuation and shelter guidance to state and local plans, with attention to the island context. The U.S. territories and Hawaii should update evacuation and shelter planning guidance to include specific state-, territory-, and local-level considerations for individuals with access and functional needs. Doing so would not only localize planning guidance, but it would also fulfill the core goals areas of the FEMA Strategic Plan (202277), which heavily focuses on climate change, equity, and building a FEMA-ready nation (FEMA, 202278). This plan embodies in many ways the current strategic direction of disaster management which places equity at the center of the work that needs to be done. The goals FEMA established in this plan include hiring people with disabilities, increasing workforce diversity, and ensuring equitable outcomes for affected populations in need of their services. Still, while national guidance is useful, island communities have unique requirements and contexts that do not align completely with those on the continent. As we found in this study, shelter-in-place guidance—especially for multigenerational households—is critical for protecting vulnerable populations from harm in island communities. Because sheltering in place is the preferred by those with access and functional needs in the territories, more robust guidance for food security, transportation, risk communication, and psychosocial support should be developed for this population.

Include access and functional needs stakeholders in designing educational and training programs. Disaster management organizations and agencies should increase awareness among access and functional needs stakeholders of education and training opportunities for caregivers and care receivers during disasters. These organizations should also prioritize making these services more accessible to this population. Moreover, organizations should adopt the Feeling Safe, Being Safe model which operationalizes the ethos of “nothing about us without us” and provides organizations with guidance about how to design programs for individuals with access and functional needs with their collaboration (Self-Advocacy Advisory Council, 2020). Training centers responsible for developing and delivering training for caregivers and care receivers should be cognizant of the difference between designing for and designing with individuals with access and functional needs. Training content, delivery platforms, outreach strategies, and evaluation mechanisms should be developed with advice from and consultation with individuals with access and functional needs to improve public health equity in education and training. Training providers must be proactive in conducting outreach to access and functional needs stakeholders to ensure awareness of existing training for caregivers and care receivers.

Add training exercises for access and functional needs population to public health and disaster scenario planning. Public health and disaster management organizations should strengthen their workforce development programs in the U.S. territories and Hawaii so that these organizations are prepared to assist individuals with access and functional needs. For example, training exercises should include access and functional needs scenarios such as evacuating individuals in wheelchairs, providing food security solutions for individuals sheltering in place, and coordinating interpretation services for individuals who are deaf, blind, or who have limited literacy (Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Centers, 202179). The Feeling Safe, Being Safe training model frames both caregivers and care receivers as agents of preparedness (Self-Advocacy Advisory Council, 2020). This is a useful model in the territories and Hawaii where familial and social ties often drive individual decision making for protective action. If individuals are more likely to prefer caring for themselves and their household members at home within island communities, education and training for preparedness must reflect these values.

Incorporate representatives from access and functional needs population in emergency operations centers. Healthy relationships across linking social capital networks have a positive effect on community resilience. Agencies responsible for access and functional needs exhibit strong bonding (within networks) and bridging (between networks) social capital; linking social capital (across vertical gradients and hierarchies) should be strengthened (Aldrich & Meyer, 201580). One way to approach this is to advance the role of disability integration in FEMA regional offices toward long-term, on-site representation in island communities and emergency operations centers. There is evidence that current FEMA Office of Disabilities Integration and Coordination representatives have gained and fostered trust with leaders within advocacy circles for individuals with access and functional needs in the U.S. territories and Hawaii during the pandemic. Emergency operations centers are responsible for centralizing coordination across agencies during disaster events but still largely leave out FEMA’s disability integration coordinators and specialists, whose responsibilities already involve ensuring that emergency response operations consider challenges faced by those with access and functional needs (T. Tua-Tupuola, personal communication, March 2022). Access and functional needs should be critical aspects to emergency operations center planning to ensure that issues like evacuation and sheltering options are accessible and equitable.

Re-evaluate the definition of access and functional needs. The term “access and functional needs” requires demarcation from “underserved populations” and “disabled populations.” This terminology should be clarified so that agencies can better coordinate how to provide inclusive and equitable services to specific vulnerable groups. The current CDC definition of access and functional needs population includes individuals with a physical, developmental, or intellectual disability; individuals with economic disadvantage; older adults; children; pregnant women; individuals with limited English proficiency or limited literacy; individuals with a chronic medical condition; and individuals with mobility challenges (CDC, 2021). The definition developed by FEMA includes these same groups except for children or pregnant women. There are other groups—such as migrants, individuals who are undocumented, and gender and sexual minorities—who may also experience vulnerability during disasters but are not included in the CDC or FEMA definitions of the access and functional needs population (Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, 201781; National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 201882). Often, competitive grants and funding opportunities for federal, state, and local initiatives are defined by their focus on underserved, vulnerable populations, and/or access and functional needs populations. Triangulating between which term refers to which groups can become a challenge to ensure no group gets left behind. Government agencies, academics, groups working with individuals with access and functional needs, and relevant stakeholders would benefit from coming to a consensus about who this term refers to, in order to help agencies better coordinate, identify, and provide resources and services to specific vulnerable groups.

Recognize the uneven playing field that the U.S. territories too often face. Our study shows significant differences in planning resources and education and training needs between the U.S. territories and Hawaii. Survey results showed that those in the territories were nearly nine times as likely to feel less prepared for evacuation and shelter than those in Hawaii. Out of their own necessity and scarcity of alternatives, emergency managers and practitioners in the U.S. territories have innovated solutions such as sheltering in place and adapting education and training curriculum developed elsewhere. However, bringing the U.S. territories into focus at the center, rather than the periphery, will be crucial to building long-term resilience, especially for those with access and functional needs.

Limitations and Strengths

There are four main limitations of the study. First, our survey and interview sample overrepresented respondents from Hawaii. However, overrepresentation of the sample population in Hawaii has also served as a strength of the study. Availability of more data around one island geography supported the research team in being able to describe a more granular, detailed picture of planning gaps in a place that experiences similar challenges to other jurisdictions in the study. Second, there is a bias toward the perspectives of disaster risk reduction stakeholders who work for government agencies; this group was also overrepresented in the study sample. As such, attitudes about who is responsible for evacuation and shelter planning mostly represent individuals within the public sector. Likewise, this is also a strength, given the study’s finding that study participants largely feel that government agencies should take responsibility for evacuation and shelter planning for individuals with access and functional needs. Third, the study did not evenly capture all groups that fall under access and functional needs. Study participants were mostly stakeholders working with individuals with physical, developmental, or intellectual disabilities; older adults; individuals with limited language proficiency or literacy; individuals with a chronic medical condition; and individuals with mobility challenges. Stakeholders working with pregnant women, children, and individuals with economic disadvantage; sexual and gender minorities; and migrants were underrepresented in the study sample. Finally, the study timeline was relatively short and participant enrollment in the survey and interviews took place over only six weeks. This was not enough time to publicize the project in multiple forums or expand survey outreach and interviewee recruitment. In addition, our survey and interview recruitment strategy was highly dependent upon the availability individuals working in emergency management. Many participants indicated enthusiasm for the study but were unable to fully participate because their availability was limited due to their active engagement with the ongoing pandemic response in their respective jurisdictions.

Future Research Directions

In future phases of this research endeavor, we plan to build a more robust evidence base for addressing the access and functional needs population by use spatial demographic data achieve the following: (a) to identify where individuals with access and functional needs live in the U.S. territories and Hawaii and (b) to determine where and what their evacuation and sheltering options would be. We will also consider using agent-based models informed by this study to predict evacuation behaviors of individuals with access and functional needs during different types of hazard events (and multi-hazard events). We will also include more organizations that work with pregnant women, children, and individuals with economic disadvantage, sexual and gender minorities, and migrants in future research projects on this topic.

Since we approach this study primarily from the perspective of planning, we aspire to motivate knowledge with action. Our study findings will be integrated as lessons learned and case studies for NDPTC’s existing training courses on Natural Disaster Awareness for Community Leaders, Natural Disaster Awareness for Caregivers, Evacuation Planning Strategies and Solutions, and Community Planning for Disaster Recovery, all of which have modules that include guidance for working with those with access and functional needs during evacuation and sheltering procedures. Course audiences include disaster managers, caregivers, NGOs, community leaders, researchers, and other stakeholders in the disaster management community. Importantly, NDPTC will consider new ways to proactively engage individuals with access and functional needs in course design and piloting processes as a best practice. The advancement of public health equity must go hand in hand with amplifying the voices and participation of those most vulnerable.

References

-

Llibre-Guerra, J. J., Jiménez-Velázquez, I. Z., Llibre-Rodriguez, J. J., & Acosta, D. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on mental health in the Hispanic Caribbean region. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(10), 1143-1146. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220000848 ↩

-

Marliana, T., Keliat, B. A., & Kurniawan, K. Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Online-Based Services to Improve Elderly Integrity and Reduce Loneliness During the Pandemic Covid-19. Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences, 18, 1-6. https://scholar.ui.ac.id/en/publications/mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-online-based-services-to-i ↩

-

Mrduljaš-Đujić, N., Antičević, V., & Britvić, D. (2021). Psychosocial effects of the quarantine during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on the residents of the island of Brač. Family Practice, 39(3), 447-454. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmab128 ↩

-

Samy, A. L., Awang Bono, S., Tan, S. L., & Low, W. Y. (2021). Mental health and COVID-19: Policies, guidelines, and initiatives from the Asia-Pacific Region. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 33(8), 839-846. https://doi.org/10.1177/10105395211025901 ↩

-

Natural Hazards Center. (2020). Mass Sheltering and Disasters Special Collection. https://hazards.colorado.edu/news/research-counts/special-collection/mass-sheltering ↩

-

Baker, E. J. (1991). Hurricane evacuation behavior. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters. 9(2), 287-310. ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., Dunn, E., Maas, L. Ackerson, E., Valmond, J., Morales, E., Colón-Burgos, D. (2021). COVID-19 and Hurricane Evacuations in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. DesignSafe-CI. https://doi.org/10.17603/ds2-7czq-en54 ↩

-

Florido, A. (2018, October 18). Why Stay During A Hurricane? Because It's Not As Simple As 'Get Out’'" National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2018/10/18/658258370/why-stay-during-a-hurricane-because-its-not-as-simple-as-get-out ↩

-

Cava, D. L. (2018). Hurricane Irma Emergency Evacuation Report and Recommendations. Miami-Dade County Commissioner, District 8. https://www.miamidade.gov/district08/library/irma-after-report.pdf ↩

-

National Disaster Preparedness Training Center (NDPTC). (2018). MGT-461 Evacuation planning strategies and solutions participant guide. FEMA. ↩

-

National Disaster Preparedness Training Center (NDPTC). (2021a). AWR-308 Natural disaster awareness for caregivers participant guide version 3.0. FEMA. ↩

-

National Disaster Preparedness Training Center (NDPTC). (2021b). AWR-356 Community planning for disaster recovery participant guide version 2.0. FEMA. ↩

-

Quarantelli, E. L. (1980). Evacuation behavior and problems: Findings and implications from the research literature. Ohio State University Disaster Research Center. https://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/1283 ↩

-

Yasui, A., & Numada, M. (2021). A report of the questionnaire survey on awareness of COVID-19 and shelters. Journal of Disaster Research, 16(4), 747-764. ↩

-

Wu, H.C., Lindell, M. K., Prater, C. S., & Huang, S. K. (2013). Logistics of hurricane evacuation during Hurricane Ike. In J. Cheung & H. Song (Eds.), Logistics: Perspectives, Approaches, and Challenges (pp. 127-140). Nova Science Publishers. ↩

-

Wu, H., Lindell, M., & Prater, C. (2012). Logistics of hurricane evacuation in Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 15(4), 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2012.03.005 ↩

-

Whitfield, Frederika (2017, August 27). Harvey dumps nearly two feet of rain [Television Broadcast Transcript]. CNN. http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/1708/27/cnr.02.html ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Going to a Public Disaster Shelter During the COVID-19 Pandemic. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/covid-19/public-disaster-shelter-during-covid.html ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (n.d.). FEMA Emergency Non-Congregate Sheltering during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (Interim). FEMA Policy 104-009-18. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_non-congregate-sheltering-during-the-covid-19-phe-v3_policy_1-29-2021_0.pdf ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2010). Guidance on Planning for Integration of Functional Needs Support Services in General Population Shelters. https://www.fema.gov/pdf/about/odic/fnss_guidance.pdf ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2018). Engaging Faith-based and Community Organizations; Planning Considerations for Emergency Managers. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1528736429875-8fa08bed9d957cdc324c2b7f6a92903b/Engaging_Faith-based_and_Community_Organizations.pdf ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2021). Territory and Federal Partners Execute Evacuation Shelter Drill in a Pandemic Environment. https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20210830/territory-and-federal-partners-execute-evacuation-shelter-drill-pandemic ↩

-

Kim, K. Ghimire, J., & Yamashita, E. (2021a). Factors associated with differences in initial pandemic preparedness and response: Findings from a nationwide survey in the United States. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 11, 100430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2021.100430 ↩

-

Kim, K. (2021) Evacuation Planning and Transportation Resilience. In. R. Vickerman, Ed., International Encyclopedia of Transportation (pp. 276-281). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102671-7.10136-8 ↩

-

Kim, K., Wolshon, B., Pant, P., Yamashita, E., & Ghimire, J. (2020). Assessment of evacuation training needs: Targeting instruction to meet the requirements of local communities and agencies. Journal of Emergency Management (Weston, Mass.), 18(6), 475-487. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2020.0518 ↩

-

Federal Highway Administration. (2009). Evacuating Populations with Special Needs: Routes to Effective Evacuation Planning Primer Series. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop09022/fhwahop09022.pdf ↩

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). Research report 225: A pandemic playbook for transportation agencies. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26145 ↩

-

National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP). (2020). NCHRP 20-116: An emergency management playbook for state transportation agencies. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://apps.trb.org/cmsfeed/TRBNetProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=4207 ↩

-

Prep It Forward. (2022). Disabilities and access and functional needs (DAFN) disaster and emergency communication guide. https://www.cpp.edu/em/files/shakeout-resources/dafn-communication-guide.pdf ↩

-

Renne, J. L., Sanchez, T. W., & Litman, T. (2011). Carless and special needs evacuation planning: A literature review. Journal of Planning Literature, 26(4), 420-431. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412211412315 ↩

-

Sanchez, T. W., & Brown, L. (2013). National study on carless and special needs populations. https://www.transit.dot.gov/sites/fta.dot.gov/files/FTA_Report_No._0067.pdf ↩

-

(2020, August 20). Fire Evacuation Shelters Now Have COVID-19 Protocols [Video]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=329258764883648 ↩

-

City and County of Honolulu Department of Emergency Management. (2021). Make a Plan. http://www.honolulu.gov/dem/preparedness/make-plan.html ↩

-

Indiana State Department of Health. 2021. COVID-19 Toolkit for Long-Term Care Facility Staff. Strategies for COVID-19 in Memory Care Units. Retrieved September 28, 2021, from https://www.coronavirus.in.gov/files/IN_COVID-19%20IP%20Toolkit%20ISDH_12.17.2020.pdf ↩

-

California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services. (2019, November 13). Access and Functional Needs Concerns Met During Recent California Emergencies (No. 69) [Audio Podcast Episode]. In All Hazards. https://www.caloes.ca.gov/cal-oes-divisions/access-functional-needs ↩

-

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2020, September 8). At-risk individuals with access and functional needs. Public Health Emergency. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Pages/at-risk.aspx ↩

-

Solano County. (2017). Solano County emergency operations plan access and functional needs guidance annex. Office of Emergency Services. https://www.solanocounty.com/civicax/filebank/blobdload.aspx?BlobID=13282 ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Access and Functional Needs Toolkit Integrating a Community Partner Network to Inform Risk Communication Strategies. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/readiness/00_docs/CDC_Access_and_Functional_Needs_Toolkit_March2021.pdf ↩

-

Kuran, C. H. A., Morsut, C., Kruke, B. I., Krüger, M., Segnestam, L., Orru, K., Nævestad, T. O., Airola, M., Keränen, J., Gabel, J., Hansson, S., & Torpan, S. (2020). Vulnerability and vulnerable groups from an intersectionality perspective. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 101826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101826 ↩

-

Steinman, M. A., Perry, L., & Perissinotto, C. M. (2020). Meeting the care needs of older adults isolated at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(6), 819-820. ↩

-

Turk, M. A., & McDermott, S. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and people with disability. Disability and Health Journal, 13(3), 100944. ↩

-

Whytlaw, J. L., Hutton, N., Yusuf, J. E. W., Richardson, T., Hill, S., Olanrewaju-Lasisi, T., Antwi-Nimarko, P., Landaeta, E, & Diaz, R. (2021). Changing vulnerability for hurricane evacuation during a pandemic: Issues and anticipated responses in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 61, 102386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102386 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2020). ADA National Network Learning Session: FEMA Perspective on Emergency Management, COVID‐19 and People with Disabilities. An overview of FEMA’s roles and responsibilities in the midst of COVID‐19. https://adapresentations.org/doc/8_12_20/FEMA%20Perspective%20on%20Emergency%20Management,%20COVID-19%20and%20People%20with%20Disabilities.pdf ↩

-

Botzen, W. J., Mol, J. M., Robinson, P. J., Zhang, J., & Czajkowski, J. (2022). Individual hurricane evacuation intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights for risk communication and emergency management policies. Natural Hazards, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05064-2 ↩

-

Cohn, P. J., Carroll, M. S., & Kumagai, Y. (2006). Evacuation behavior during wildfires: results of three case studies. Western Journal of Applied Forestry, 21(1), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.1093/wjaf/21.1.39 ↩

-