The Public Health Implications of Social Vulnerability in the U.S. Virgin Islands

Publication Date: 2022

Executive Summary

Overview

The U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), a U.S. territory in the Caribbean, is a highly unequal community with high levels of poverty, high health disparities, low home ownership rates, and low educational achievement. The USVI is also impacted by natural hazards such as hurricanes, droughts, and earthquakes. The health and well-being of people with high levels of social vulnerability—that is, those who experience negative impacts from factors such as limited economic means, disability, age, racial or ethnic identity, language barriers, or substandard housing or transportation—are generally more at risk from the impacts of disasters. The creation of a social vulnerability index for USVI communities is critical to understanding the social determinants of health for the most vulnerable and creating appropriate policy and interventions to protect them from adverse outcomes during disasters.

Although the social vulnerability of people living in all U.S. states and most other territories has been quantified and then mapped using sophisticated geographic information systems (GIS) tools, an equivalent geospatial dataset of the social vulnerability of the communities of the USVI has not been developed. Consequently, interventions to protect vulnerable communities are being crafted in the absence of data. Without this data, local agencies are likely unaware of large swaths of the population that could be better protected from harm and negative health outcomes associated with hazards.

Research Questions

In this study, we are asking the following research questions:

- What is the spatial distribution of social vulnerability in the U.S. Virgin Islands?

- Are places with high social vulnerability also more at risk of flooding impacts than places of low social vulnerability?

Research Design

To calculate a USVI social vulnerability index, we followed the method used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), but adapted it to recognize that the USVI Census results are provided at the estate level, rather than traditional census tracts. We also normalized the variables used to account for the difference in population numbers between estates. Results are presented by dividing populations in each estate into quartiles, representing populations with the lowest to highest social vulnerability.

Findings

This report provides the first estimate of social vulnerability in the USVI. We found that most urban populations in St. Thomas and St. Croix had high levels of social vulnerability. We also found that most populations with high levels of vulnerability are at greater risk of exposure to flooding, especially on St. Thomas. On St. Croix, they live downwind from a major industrial area that also has a refinery. On St. Thomas and St. Croix, they live near major roads, airports, ports, and other industrial facilities. Results of this analysis can be used to better understand, mitigate, and communicate risk to populations in the USVI.

Public Health Implications

Results indicate the populations that had the highest social vulnerability were also the most exposed to sources of noise and air pollution, placing them at higher risk of developing mental and physical ailments. In addition, many are located in flood zones, especially in St. Thomas. These compounding factors must be addressed to improve the ability of these populations to rebound faster after major disasters.

Introduction

Disasters are harmful to people’s health. People can be injured or killed in floods, windstorms, earthquakes, other type of hazards, or a combination of hazards. People also die after disasters because of the consequences of the event on critical infrastructure and essential services sectors (loss of power, loss of water, loss of transportation, etc.) (Méndez-Lázaro et al., 20211). In addition to these impacts on physical health, disasters also have negative effects on mental health (Goldmann & Galea, 20142), which can linger and impact people’s ability to thrive long after an event (Bland et al., 19963; Makwana, 20194).

To reduce the negative health impacts of disasters, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and others have developed various social vulnerability indices (Flanagan et al., 20115). Social vulnerability indices are computed using census data describing the following variables: level of poverty; unemployment level; per capita income; educational attainment; persons 65 years of age or older; persons 17 years of age or younger; persons with disabilities; single parent households; minority populations; those who do not speak fluent English; multi-unit housing structures; mobile homes; household crowding; transportation availability; and persons living in group quarters (CDC, 2018). Flanagan et al. (2011) validated these variables for use in disaster management, concluding that they provide useful information for locating socially vulnerable populations.

The U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), a territory of the United States since 1917, suffers from a high level of poverty, with 22% of the population and 30% of families with children living in poverty; low educational achievement, with nearly 60% of students testing below standard for literacy and mathematics; lack of access to affordable fresh and healthy food, and limited access to health care (Mills et al., 20186; Nunez-Smith et al., 20117; St. Croix Foundation for Community Development, 20218; U.S. Census Bureau, 20149; Wang et al., 202010). In addition, health disparities are some of the highest in the country (U.S. Virgin Islands Department of Health, 202011). At the same time, the USVI has experienced a variety of natural hazards: hurricanes, which bring high wind speeds, rain, and storm surges; rainstorms; earthquakes; tsunamis; droughts; and epidemics caused by mosquito borne diseases or other viruses such as COVID-19.

Despite the threat natural hazards pose to the USVI, no national database or report has been developed to measure the social vulnerability of people living in the islands. The main reason is that census data is analyzed at the county scale, and counties do not exist as a geographic unit in the USVI (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 202212). As a result, the USVI lacks an understanding of the geographic spread and variation in social vulnerability across its communities. It also has limited understanding of the location of the most vulnerable populations and the causes of this vulnerability. Consequently, emergency management and other organizations are developing disaster preparedness or mitigation strategies without a full understanding of population needs and vulnerabilities. In addition, efforts by these agencies to inform the population about emergency preparedness or household mitigation strategies might not reach all groups that would benefit from such messages.

Here, we are presenting, for the first time, the results of a social vulnerability analysis for the USVI. The social vulnerability index for the USVI was computed using data from the 2010 U.S. Census, and shows where, on each island, people are likely to be more vulnerable to the impacts of disaster based on their socio-economic status, household composition, ability status, race, language, and housing and transportation access. We also analyze whether groups with the highest social vulnerability levels are also at higher risk of exposure to stormwater damage compared to the lowest level of vulnerability.

Literature Review

Why a Social Vulnerability Index

Since the Disaster Management Act of 2000, states and territories have developed hazard mitigation plans to identify and address where hazards could damage critical infrastructure and disrupt services (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 200813, 201814). The physical approach to hazards, however, does not take into consideration how social variables—class, gender, race, disability status, sexual identity, etc.— shape resilience to hazard impacts (Fordham et al., 201315). The physical approach also does not show how some groups of people within the same locations are made more fragile because of their socio-economic conditions. These groups suffer more adverse disaster outcomes for various reasons, including being less likely to afford emergency expenses be or have the ability to evacuate; being more likely to have pre-existing health conditions; and being more likely to live in substandard housing that is unable to resist storms or is located in hazard-prone areas.

Social vulnerability impacts the human ability to cope in hard times and conditions. Most demographic measures of vulnerability—such as age, income, education, gender, and race—are also indicators of social inequality (Kuhlicke et al., 201116, King & MacGregor, 200017; Tapsell et al., 200218; Cutter et al., 200319). Social vulnerability is unequal across people and places, creating differential vulnerability in a population (Wu et al., 200220). And most importantly, this vulnerability is highly related to location. Some communities as described or defined by certain social, demographic, and economic conditions tend to also display high natural hazard risk because where they live, such as in coastal plains, floodplains, and seismic zones (Chang et al., 201521). Therefore, to reduce the negative impacts of natural hazards on health, it is important to understand the social vulnerability of a population, in addition to its physical vulnerability (Fordham et al., 2013).

Researchers generally measure and communicate social vulnerability using a composite index approach because it produces one number resulting from multivariable analyses, through a method that is replicable and comparable across time and space, as well as various users and audiences (Alwang et al., 200122). The social vulnerability index developed by Cutter et al. (2003) was the first effort to examine the spatial patterns of social vulnerability to natural hazards in the United States at the county level (Schmidtlein et al., 200823). After the U.S. Congress passed the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act in 2006, the CDC developed its own methodology to create a nationwide social vulnerability index. The index the U.S. mainland was first published in 2011 (Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program, n.d.24) and more recently for territories of Guam and Puerto-Rico (Paulino et al., 202125; Tormos-Aponte et al., 202126).

Uses of Social Vulnerability Indices

Because they are standardized, social vulnerability indices allow for analysis and comparison of social vulnerabilities across various geographies (Kuhlicke et al., 2011). One disadvantage of standardization is that local nuances can be lost (Weis et al., 201627). However, certain overarching results and trends remain stable even when scale of variable aggregation changes (Schmidtlein et al., 2008). This stability and robustness allow results of social vulnerability indices to be used for policy development, government affairs, and the public agendas of hazard mitigation and development (Benson, 201328). This has proved to be especially crucial in federal, state, and local discussions related to program development and funding for climate adaptation, disaster management, and equitable development (Weis et al., 2016; Wood et al., 202129). The CDC map and database of social vulnerability indices for the continental United States and Puerto Rico (CDC, 2022) have also been used to support state, local, and tribal health and emergency managers in planning and executing aid response after disasters, hazard mitigation planning, and assessments of vulnerability to physical hazards including sea level rise, flooding, tornadoes, and volcanic risk (Lue & Wilson, 201730; Horney et al., 201731).

Another common application of social vulnerability indices has been to raise awareness of equity issues in planning practices and exposure to hazards, such as flooding. Analysis of hazard and social vulnerability assessments demonstrated that socially vulnerable populations are more likely to suffer from the impacts of flooding because they tend to disproportionately occupy flood-prone areas (Tate et al., 202132; Platt, 199833; Lee & Jung, 201434; Rolfe et al., 202035; Qiang, 201936). Specifically, communities whose members are from racially marginalized groups, impoverished or low-income, and have higher rates of unemployment are more likely to suffer adverse outcomes in disasters than other social groups (Laska & Morrow, 200637; Adeola & Picou, 201238; Collins et al., 201339; Emrich et al., 202040).

Limitations of Social Vulnerability Indices

There are several limitations to the taxonomic approach of an index to capture a complex concept such as social vulnerability. Aside from the complications that arise from trying to make representative the often limited data available on vulnerability, differences in the interpretation and definition of vulnerability, in the selection of proxy variables, and in the analysis of the relationship amongst the proxy variables all have been considered in the literature (Schmidtlein et al., 2008). Poorly designed or communicated analyses can lead to limited, stereotyped, and poorly informed views of vulnerable people (Kuhlicke et al., 2011). Also, a composite index does not reveal the historical root causes of vulnerability and the social structures which reproduce it (Adger et al., 200441; Wood et al., 2021).

Perhaps more importantly, it is still unclear if policy makers and emergency managers use social vulnerability indices to guide their mitigation or preparedness strategies. For example, there are few publications about how the use of social vulnerability indices impact resource allocation and activities undertaken at the local scale in the name of reducing vulnerability (Chang et al., 2015; Wood et al., 2021).

Research Design

Research Questions

In this study, we are asking the following research questions:

- What is the spatial distribution of social vulnerability in the U.S. Virgin Islands?

- Are places of high social vulnerability also more at risk of flooding impacts than places of low social vulnerability?

Study Site

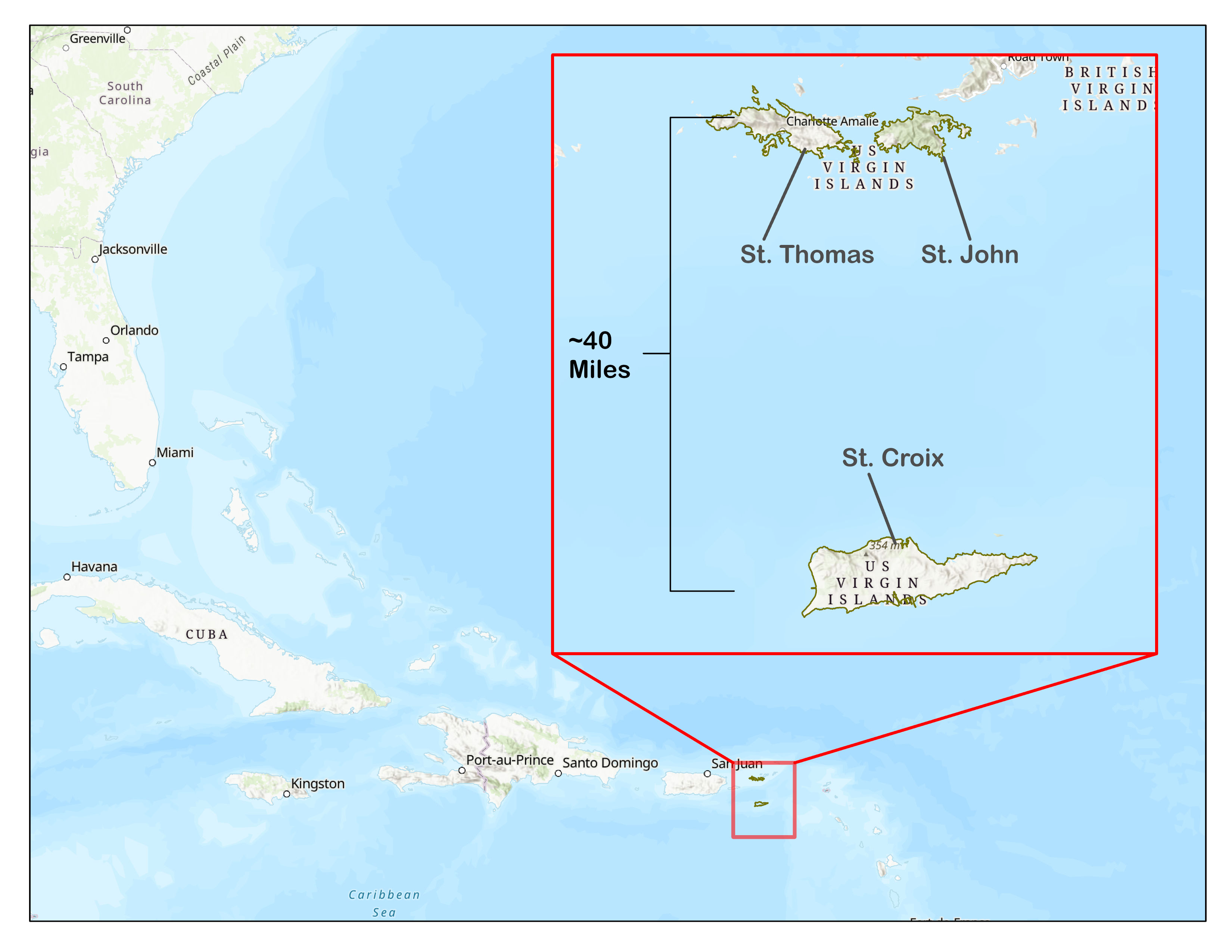

The USVI is a territory of the U.S. composed of three main islands: St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John (see Figure 1). The territory has only one level of government consisting of a governor and senate, which are responsible for governing the entire territory. There is no House of Representatives and there are no municipal governments.

Figure 1. Map of U.S. Virgin Islands in the Caribbean

Each island is divided into estates, which are old land-tenure boundaries that were created during the slavery era (United States Virgin Islands, 202242). Estates are used to identify places, but they are not political jurisdictions nor do they have political representatives. The geographic boundaries of estates also encompass diverse areas including various rural and urban zones, rich and poor regions and neighborhoods, and the footprint of a few buildings sometimes spans two estates.

The climate of the USVI is generally mild tropical, but the islands experience tropical storms and hurricanes on a regular basis, the most recent being Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 (USVI Hurricane Recovery and Resilience Task Force, 2018). St. Thomas and St. John have a narrow coastal zone and a steep interior. As a result, most of the large flood zones are located along the coast. St. Croix on the other hand is mostly flat, except for a mountain range on the northwest corner. As a result, flood zones are wide and cover a large portion of the island.

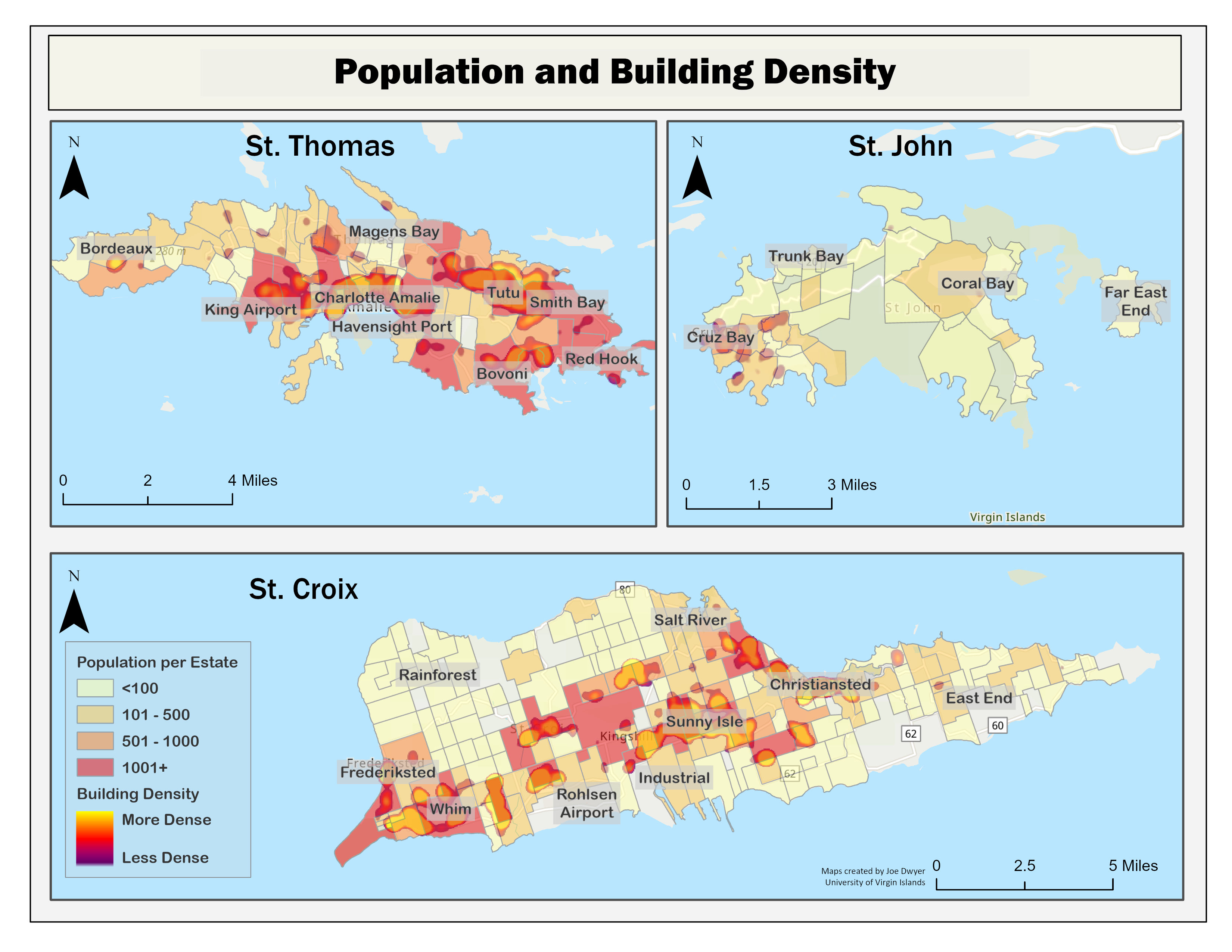

The population in 2010 was estimated at 106,405 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014), but it has decreased in the years since, first slightly to 100,768 in 2015 (Mills et al., 2018); and then precipitously after the hurricanes to 87,146 in 2020 (U.S. Census Bureau, 202143). Most of the population lives on St. Thomas and St. Croix, and in regions with high building density, especially on St. Thomas (Figure 2). In the remainder of this document, we refer to urban areas regions that have high building density and high population (e.g., Charlotte Amalie, Bovoni, Smith Bay and Tutu on St. Thomas; Cruz Bay on St. John; Frederiksted, Estate Whim, Sunny Isle, Christiansted on St. Croix).

Figure 2. Population and Building Density in the U.S. Virgin Islands

Data, Methods, and Procedures

General Model

The CDC Social Vulnerability Index is composed of fifteen census variables, which we have outlined in Table 1. The variables are scored and summed for all U.S. census tracts with a non-zero population (CDC, 2022).

Table 1. Variables in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Social Vulnerability Index

| Theme | Variable |

| Socioeconomic Status | ● People living below poverty ● Unemployed ● Median income ● People without high school diploma |

| Household Composition and Disability | ● People 65 and older ● People 19 and younger ● Children older than 5 with a disability ● Single parent households |

| Minority Status and Language | ● Minority ● Speaks English “less than well” |

| Housing and Transportation | ● Multi-unit structures ● Mobile homes ● Crowding ● No vehicles ● Group quarters |

Note. Adapted from “Planning for an Emergency: Strategies for Identifying and Engaging At-Risk Groups. A guidance document for Emergency Managers.

To develop the index for the USVI, we used the 2010 Census results (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014) that were published at the estate scale (University of the Virgin Islands, 202244), since results for the 2020 Census were not yet available. The 2010 Census of the USVI contained 335 estates. However, 85 estates had no population and were ignored, leaving 270 estates for the analysis.

We followed the method used by CDC (201545, 2022) with a few exceptions. The first adjustment was made to account for the difference in population between estates, where we first calculated the percentage of the population that fell into a particular variable category for each census variable listed in Table 1, and for each estate, (e.g., the number of persons aged 65 or older divided by the estate’s population). Next, we ordered the percentages for the variable from lowest to highest and scored the estates in ascending order. The estate in this ordered list with the lowest percentage greater than zero was given a score of 1. Each subsequent estate in the list was scored as “1 + [the previous estate’s score]”. Estates with a zero percent value for a variable (i.e., nobody in that estate fell in that particular category) were scored with “0” to indicate that they had the lowest vulnerability for that variable. After determining individual estates' overall score, we divided them all into four equal groupings based on that score.

In addition to this adjusted approach to ranking the variables, we also flagged those estates that had scores in the in the 90th percentile to account for estates where certain variables with low vulnerability might mask other variables with particularly high vulnerability in the overall score. This process was completed for all fifteen census variables, except for income, where a lower value represents higher vulnerability and does not require creating a percentage. After ranking all variables, we summed the relevant variable scores of each estate to create a theme score. We also ordered theme scores from lowest to highest, divided them into quartiles, and identified those estates in the 90th percentile.

From the raw values for each theme as described by the CDC (2015), we computed a total vulnerability score by summing the scores of each theme for each estate, and ranked them into quartiles and again identified those in the 90th percentile. Table 2 displays a sample of scores and associated rank for each theme for six (out of 270) estates. The percentiles and quartile distribution were similar. We did not normalize the results like the CDC does because this step did not add any new information to our findings.

Table 2. Sample of Social Vulnerability Score and Ranking for Six Estates

| Estate Name | Socioeconomic Status | Household Composition and Disability | Minority Status and Language | Housing and Transportation | Social Vulnerability | |||||

| Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | |

| Adelphi | 839 | 4 | 465 | 3 | 248 | 3 | 34 | 1 | 1586 | 4 |

| Adrian | 408 | 3 | 368 | 2 | 267 | 3 | 356 | 4 | 1399 | 3 |

| Adventure | 679 | 4 | 366 | 2 | 308 | 3 | 313 | 4 | 1666 | 4 |

| Agnes Fancy | 477 | 3 | 444 | 3 | 305 | 3 | 129 | 2 | 1355 | 3 |

| All for the Better | 409 | 3 | 350 | 2 | 205 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 964 | 2 |

| Altona | 200 | 1 | 520 | 4 | 106 | 2 | 308 | 4 | 1134 | 2 |

Once the final social vulnerability index score was computed, we imported the database with these records into the geographic information system (GIS) program, ArcGIS Pro. This program allowed us to display the results spatially. The full results of our social vulnerability analysis for all 270 estates in the USVI is presented in the appendix.

Social Vulnerability and Flood Risk

As mentioned earlier, people with high social vulnerability are more likely to suffer during flooding events. We quantified the spatial relationship between exposure to flooding risk and social vulnerability in the USVI to better understand the potential overlap.

We obtained flood maps from the Hazard Mitigation and Resilience Plan for the USVI (n.d.46). These flood maps are improvements from the existing territorial flood maps because they were generated using a rainfall-runoff approach rather than a streamflow approach, which neglects runoff outside the floodplain near streams (Strategic Alliance for Risk Reduction [STARR], 201847). In some places, they reproduce previous maps, but they also cover other regions that were not included in previous efforts because of modeling limitations (STARR, 2018).

From the cadastral, or property registrar system, we identified those homes and apartment buildings that would be flooded during a 100-year storm event and computed the percentage of those houses in the flood zone that fall in the different vulnerability categories. We also identified how much of the road network (including primary and secondary roads) is in the flood zone for each estate.

Findings

Social Vulnerability

Socio-Economic Status

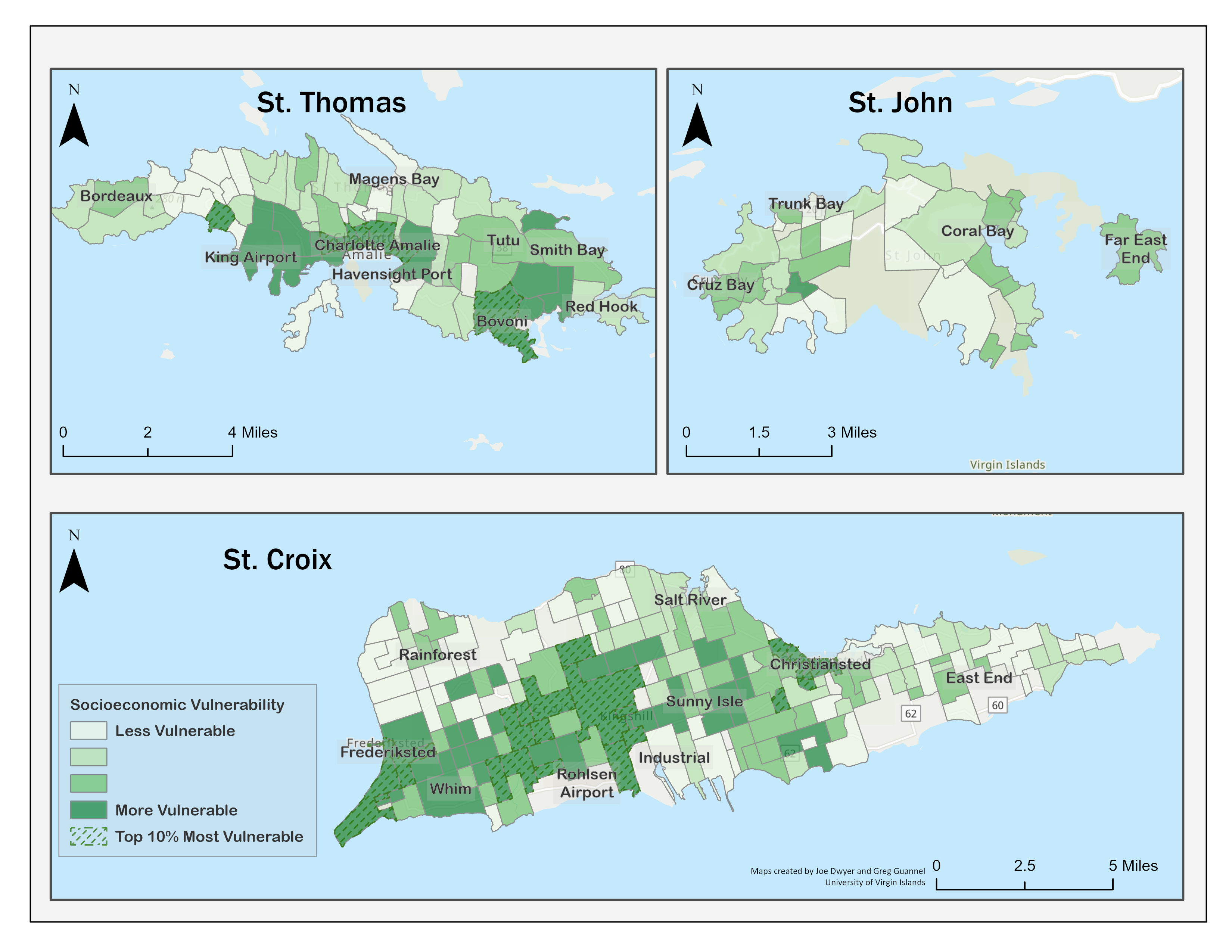

Figure 3 presents the results of our analysis of socioeconomic vulnerability. As the map shows, individuals with the highest social vulnerability were located in the urban areas—defined as those with high population and high building density (see Figure 2). St. Croix had more regions or estates of high socio-economic vulnerability compared to the other islands. However, this does not mean that St. Croix has less social vulnerability. Overall population number, poverty, and income levels were comparable between St. Thomas and St. Croix, but St. Croix is less densely populated than St. Thomas, which means that people with higher social vulnerability are more spread out than on St. Thomas.

Figure 3. Socioeconomic Vulnerability of USVI Population

On St. Thomas, regions of higher socio-economic vulnerability were concentrated in the urban regions of Charlotte Amalie, Bovoni, Smith Bay, and near the King airport. On St. John, the most socio-economically vulnerable areas were concentrated in the region east of the urban center of Cruz Bay. In contrast, on St. Croix, regions of high socio-economic vulnerability were spread across a wider area that extends from Frederiksted, Whim, Sunny Isles, and towards Christiansted.

Household Composition and Disability

Figure 4 displays the results of our analysis of household composition and disability. In many ways, these results were similar to the socioeconomic analysis. On St. Thomas, the regions of high household and disability vulnerability are in Bovoni and Charlotte Amalie. However, two rural regions did not exhibit the highest socioeconomic vulnerabilities—the Tutu and Bordeaux regions. These are home to many farmers and have high levels of vulnerability on the measures of household composition and disability.

Figure 4. Household Composition and Disability Vulnerability of USVI Population

On St. Croix, Frederiksted, Christiansted, and Whim also show a high household composition and disability vulnerability. However, in general, St. Croix has fewer estates with high levels of these types of vulnerabilities than it has estates with high levels of socioeconomic vulnerability.

On St. John, the area of high socioeconomic vulnerability has medium to low household composition and disability vulnerability, but estates south of Cruz Bay have a higher vulnerability.

Our analysis shows that there is some overlap between socio-economic and household vulnerabilities, but it is not universal. Some areas have high household vulnerabilities, but lower socio-economic ones. The difference is probably related to the fact that households in these estates are often multi-generational family units who have established social roots in these regions for many generations. These are also traditionally middle-class regions, especially on St. Thomas. However, as the results show, they are home to people whose age and disability status put them at a disadvantage when it comes to resilience to natural hazards. In contrast, some areas—for example, estate Bovoni on St. Thomas and estates Whim, Christiansted, and neighboring estates on St. Croix—show both high socioeconomic and high household composition and disability vulnerability.

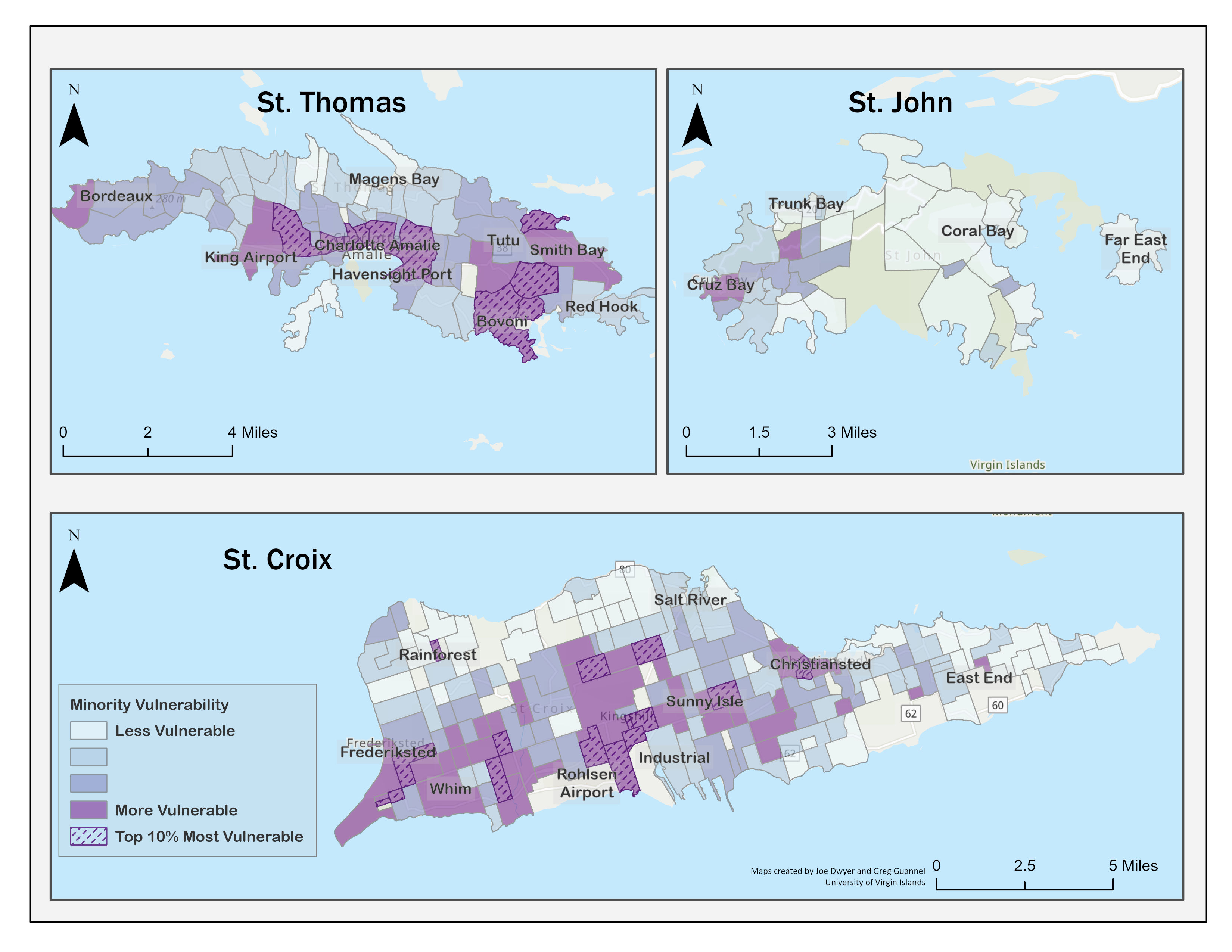

Minority and Language

Figure 5 displays the results of our analysis of minority and language vulnerabilities. The map shows high vulnerability in regions which are populated predominantly by people who are Blacks and/or Hispanic. Moreover, people in these areas are also often immigrants from other islands in the Caribbean (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Results for St. Thomas and St. Croix have some similarities with the previous two themes. On St. Thomas, the Bovoni region is once again the most vulnerable. But so is the Charlotte Amalie region, and the Tutu region and surrounding estates, such as Smith Bay. On St. Croix, estate Whim and surrounding estates, Sunny Isle and the region near the refinery, and Christiansted are again among the most vulnerable. On St. John, however, the most vulnerable estates are in Cruz Bay and east of Cruz Bay. St. John was the only island in our analysis where results vary from one theme to another and there is not one estate with consistent high ranking.

Figure 5. Minority and Language Vulnerability of USVI Population

Interestingly, the maps show that estates with lower socioeconomic vulnerability tend to also have lower minority and language vulnerabilities. This is evident on the north-northwest side of St. Thomas, the East End of St. Croix, and the east side of St. John. According to the Census and Community Survey data (Mills et al., 2018; U.S. Census Bureau, 2014), the low vulnerability areas are populated mostly by Whites who tend to earn more, on average, than Blacks. Table 3 depicts socio-economic characteristics by race in the USVI. It shows how Blacks are the predominant racial group in islands, making up 80% of the population, but also have less education, income, and wealth on average than Whites. Our analysis shows that racial inequalities are correlated with vulnerability: Estates with high socioeconomic, racial and language, and household composition and disability vulnerabilities tend to be populated mostly by Blacks and Hispanics.

Table 3. Socioeconomic Characteristics of White, Black, and Other Racial Groups in the U.S. Virgin Islands

| Variable | Overall | Black | White | Other | |

| Population | Total | 100,768 | 80,559 | 11,672 | 8,537 |

| Percent | 100 | 80 | 12 | 8 | |

| Education | Percent high school or above | 70 | 70 | 79 | 59 |

| Percent bachelor degree or above | 15 | 13 | 30 | 11 | |

| Poverty | Percent below poverty line | 20 | 21 | 17 | 16 |

| Income and Wealth | Median Income | $33,964 | $33,677 | $43,073 | $24,309 |

| Median Home Value | $199,849 | $197,265 | $442,201 | $150,568 | |

| Housing Type | Percent in owner-occupied housing units | 47 | 46 | 51 | 49 |

| Percent in renter-occupied housing units | 53 | 54 | 49 | 51 | |

Similar patterns are usually observed in more mixed parts of the United States, and states with White population majorities. However, analysis of the latest community survey results show that Whites, on average, have higher educational achievement and more wealth. They are also more likely to own their home and have more valuable homes. These dynamics have roots in history and other socioeconomic forces (Dookhan, 199448; Krigger, 201749).

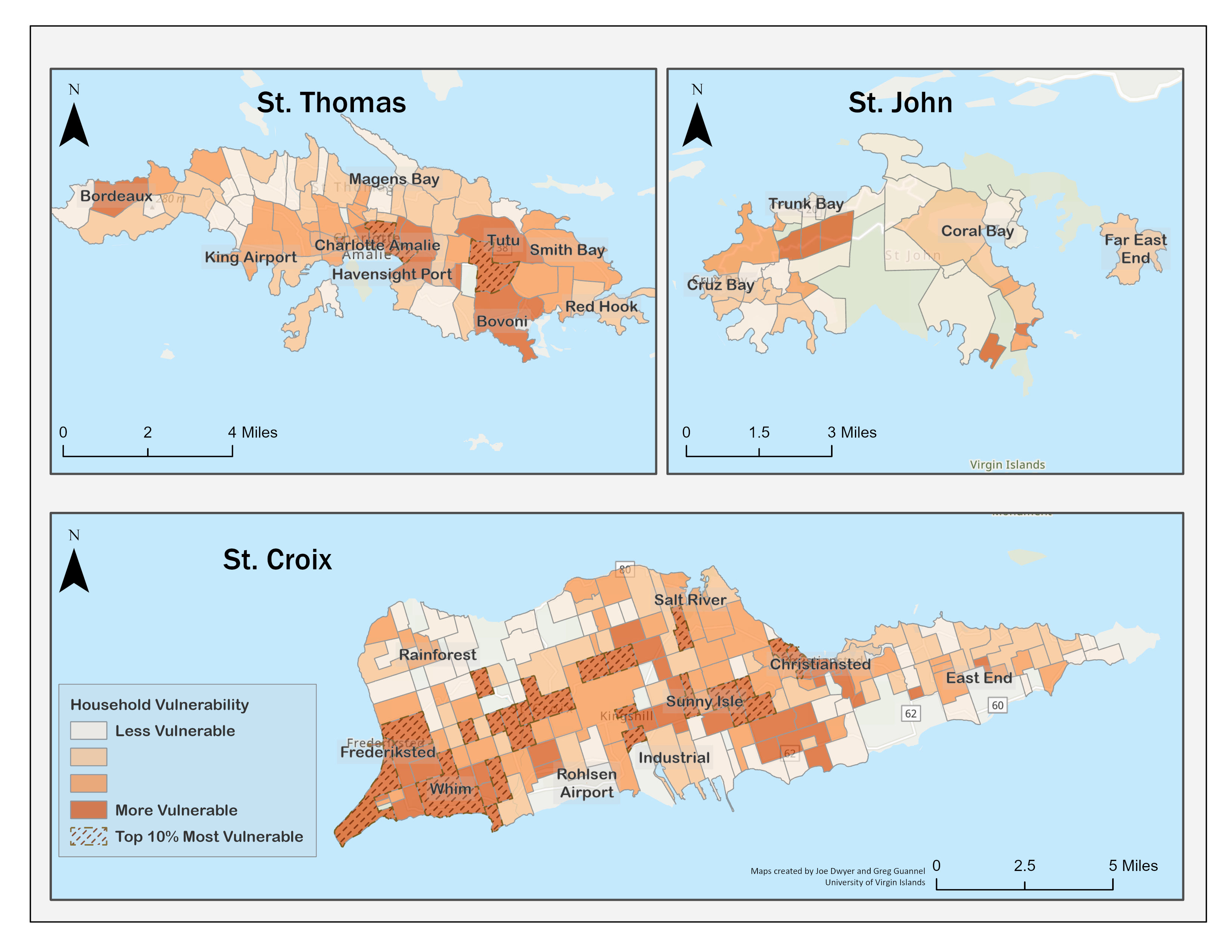

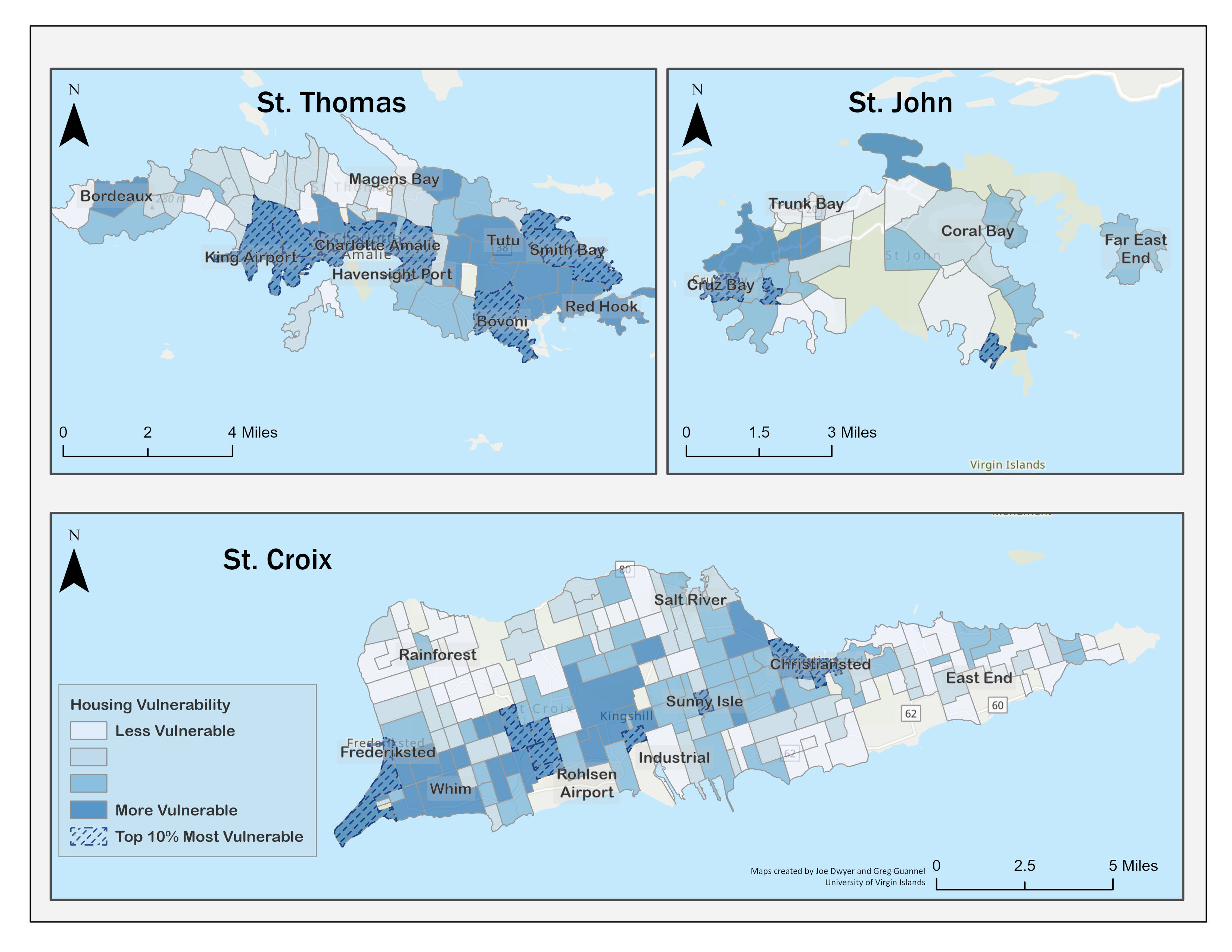

Housing and Transportation

Figure 6 displays the results of our analysis of the last theme, housing and transportation. This map is, to some extent, the least similar to the other themes. On St. Thomas, the Charlotte Amalie, Bovoni, Smith Bay areas again shows some high housing and transportation vulnerability. So do the east end of the island and estates spread in the north and central parts of the island. On St. Croix, Frederiksted, estate Whim and Christiansted also show high vulnerability, but so do parts of the northeast and north. On St. John, estates that did not have high vulnerability for the other themes exhibit high housing and transportation vulnerabilities.

Figure 6. Housing and Transportation Vulnerability of USVI Population

Despite the overall agreement between this result and previous themes, it is worth noting that in general quality housing in the Virgin Islands is a challenge for all, as illustrated by the impacts of the hurricanes (Virgin Islands Housing Finance Authority, 202050). In addition, the Virgin Islands has one of the highest car ownership rates of the nation (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014), so people of all classes tend to own a car. However, these cars are, in general, more fragile as they tend to be old—17 years old on average—based on the analysis of car registration data done by the team. This means that car ownership does not necessarily guarantee mobility during a disaster.

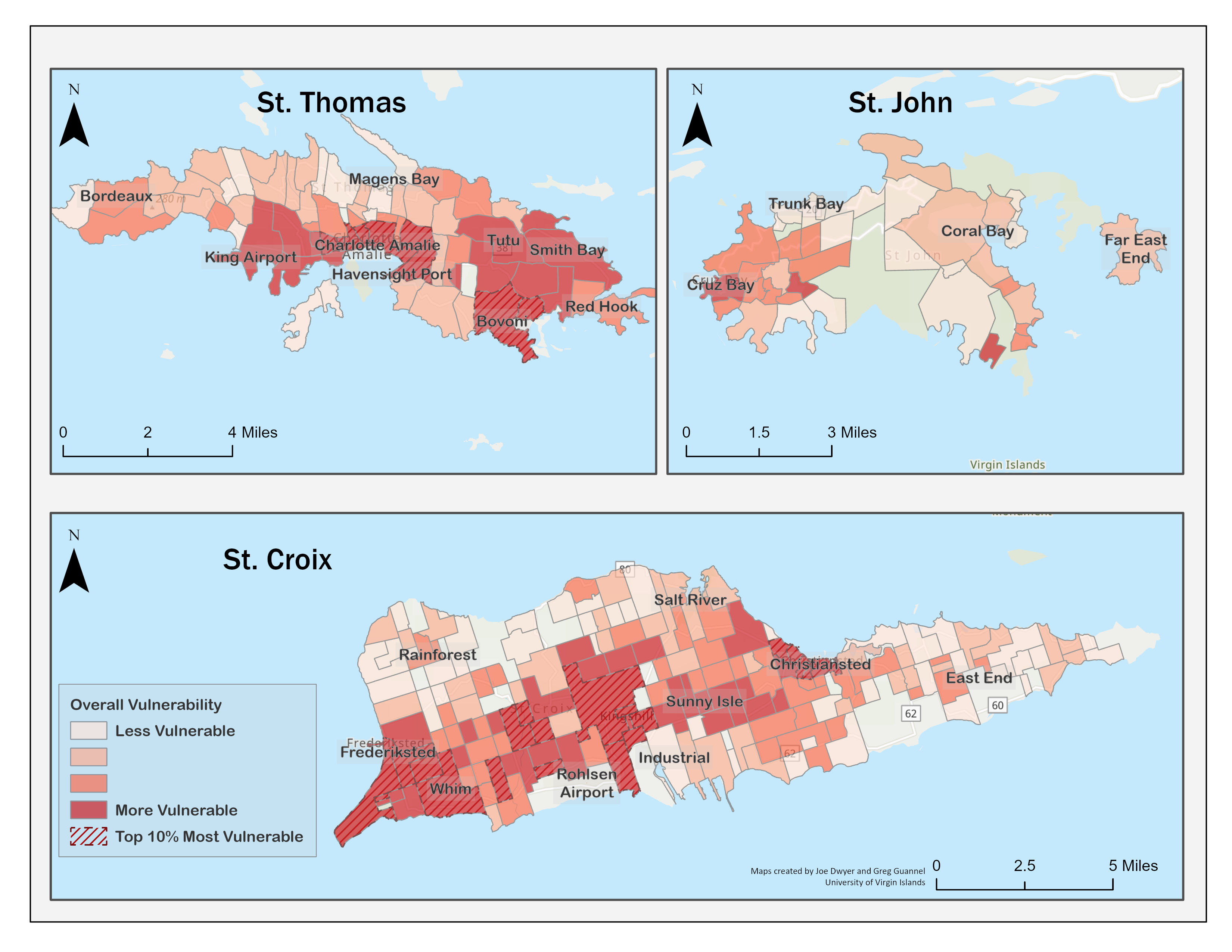

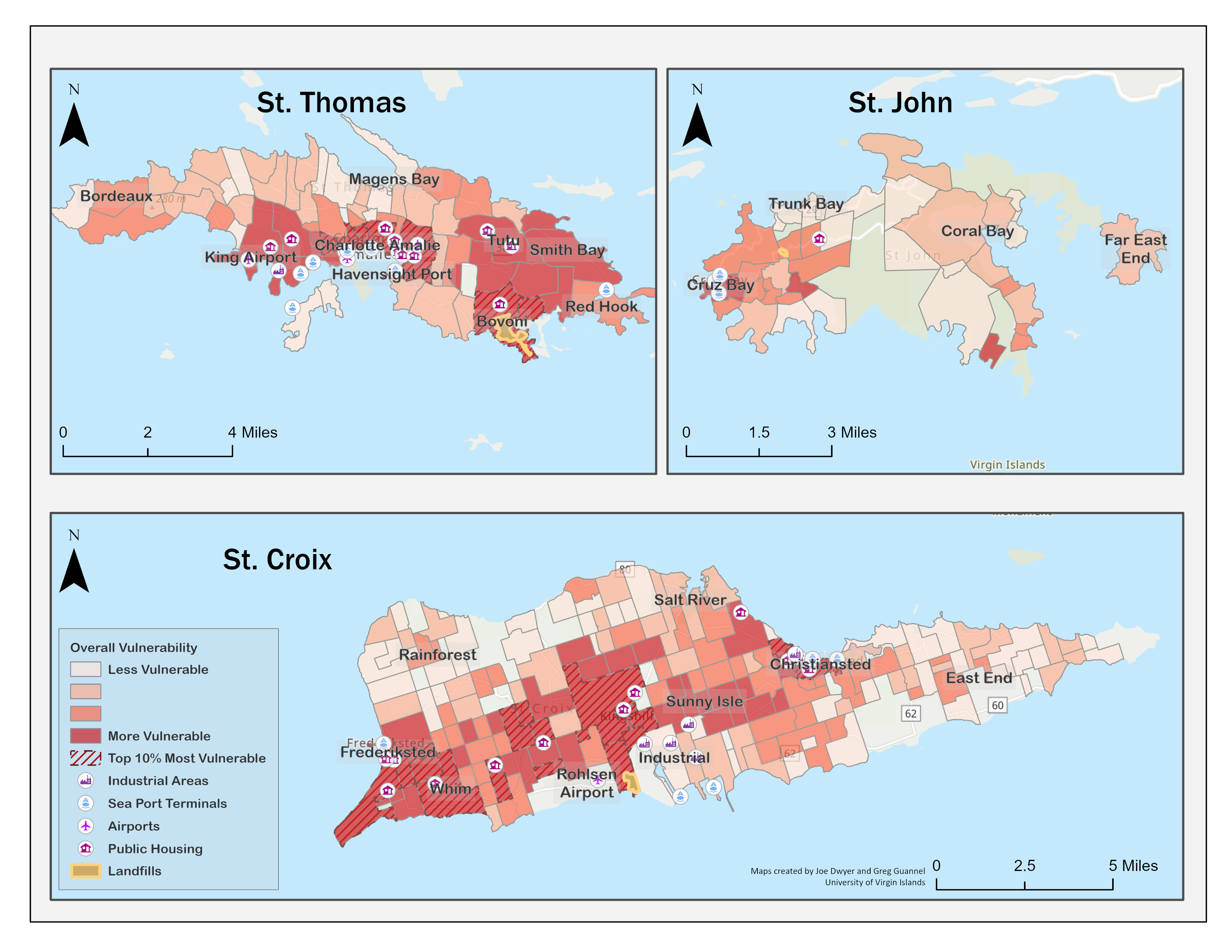

Social Vulnerability

The social vulnerability of the people living in different estates was computed as the combination of the vulnerability scores in the themes discussed above. The more vulnerable regions in the USVI are in St. Croix and St. Thomas. St. John has estates of higher vulnerability, but they are in general lower than on the other two islands. Water Island has a low vulnerability.

Figure 7. Social Vulnerability of USVI Population

The regions with the highest social vulnerability correspond to areas that have high socioeconomic, household composition, racial, and housing and transportation vulnerabilities. They tend to be regions with a high population density with many low-income housing developments. On St. Croix, they are in Christiansted, or downwind of the refinery.

The most vulnerable regions are estates around and including Whim on St. Croix, followed by Bovoni, and Charlotte Amalie. Estates west–downwind–and around of the refinery, Christiansted, as well as Tutu and estates north of Tutu also show high overall vulnerability. Few estates north-northwest on St. Thomas, east of Christiansted, and the east end of St. John show high or medium vulnerability.

Finally, although St. John has a lower social vulnerability, most of the populations with higher vulnerabilities are also in and near the urban area of Cruz Bay. Nevertheless, only one estate on that island is within the highest vulnerability quartile. It is important to note that St. John has a much lower population than the other two islands, particularly located in the island’s interior. The data from these estates may only represent extremely small populations of fewer than 25 people.

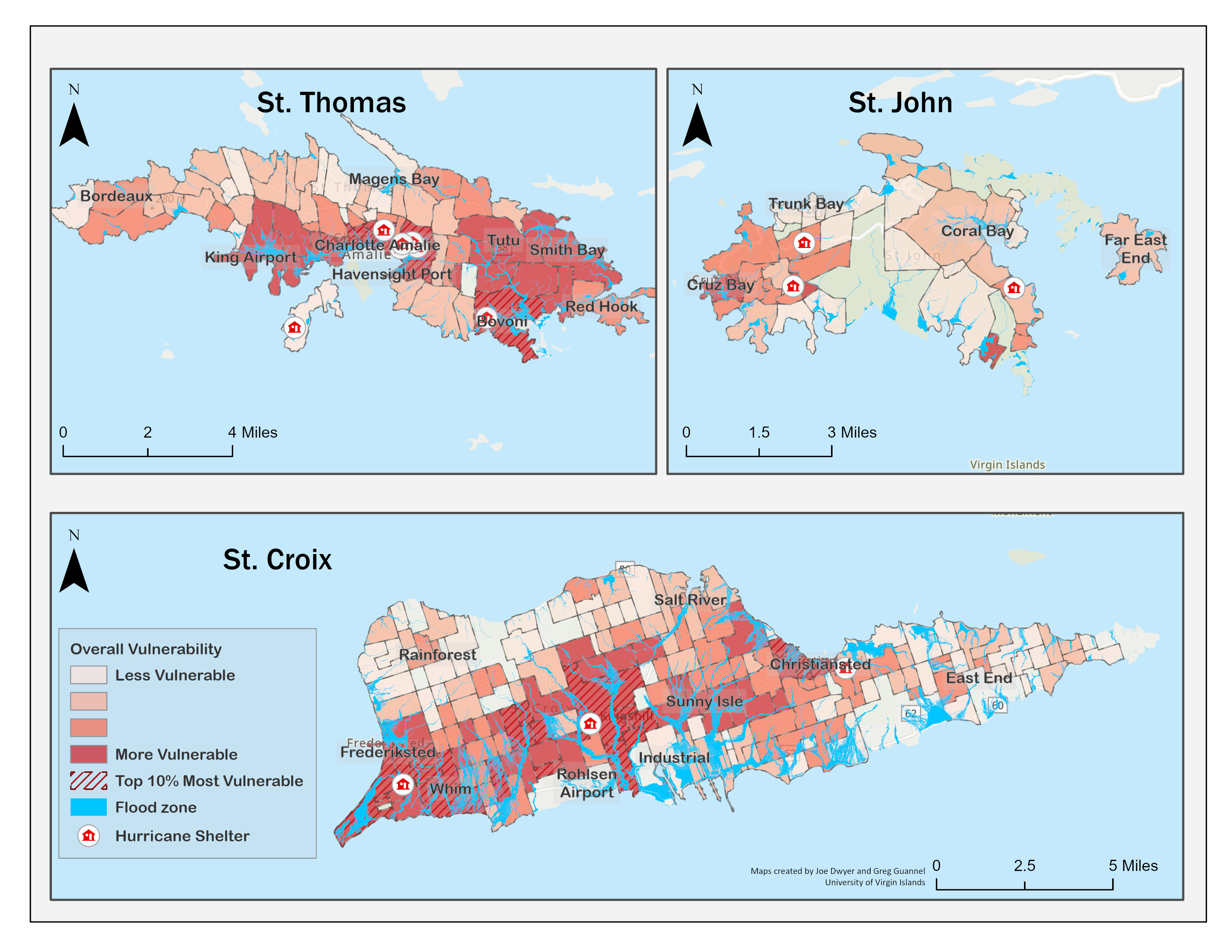

Social Vulnerability and Flood Risk Findings

Previous studies have shown that areas with higher social vulnerability tend to suffer the most from flooding impact (Tate et al., 2021; Qiang et al., 2017). As shown in Figure 8, many of the most extensively flooded areas (dark blue) are within some of the most socially vulnerable estates. For St. Thomas, the areas of Bovoni, Smith Bay (north of Tutu) and Charlotte Amalie appear to be of particular concern. This result is not surprising as most of these regions are along the coast, and due to its topography, most of the floodplains are on the coast.

Figure 8. Social Vulnerability of USVI Population and Flood Zones

Flooding on St. Croix is generally more widespread than on St. Thomas, especially on the island’s southern portion. Regions with high social vulnerability, such as the estates west of the refinery, seem to also suffer from flooding risk, as well as the Christiansted region. However, many more estates with medium to low vulnerability also are in the flood zone.

Flooding on St. John is much more localized and restricted to the immediate coastal areas due to the island’s topography. There are some flooding concerns in the relatively more vulnerable areas near Cruz Bay. Still, generally, the overall flood risk on St. John is limited and even more so for vulnerable populations.

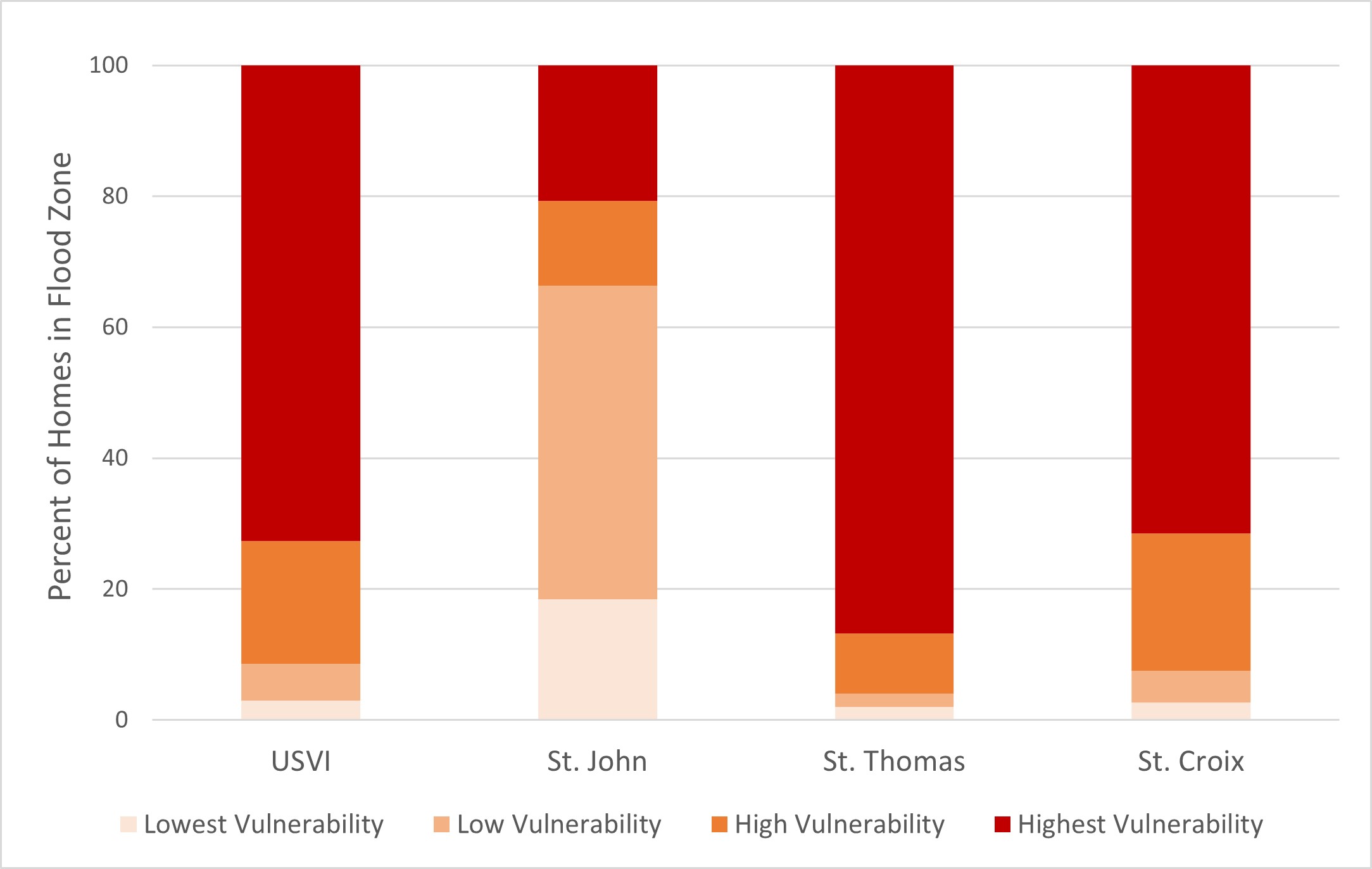

These qualitative observations are confirmed by statistical analysis. As Figure 9 depicts, 73% of the residences that are located in flood zones are inhabited by people the most socially vulnerable individuals in the USVI. This varies by island, with 87% of flood-prone homes belonging to highly socially vulnerable people on St. Thomas, 71% on St. Croix, and 33% on St. John. The latter island differs significantly from the others, in that 66% of the residences in the flood zones are home to people with lower social vulnerability. The same patterns are found when looking at estimated flood losses (not shown).

Figure 9. Share of Homes and Roads in Flood Zones Whose Residents Have Varying Levels of Social Vulnerability

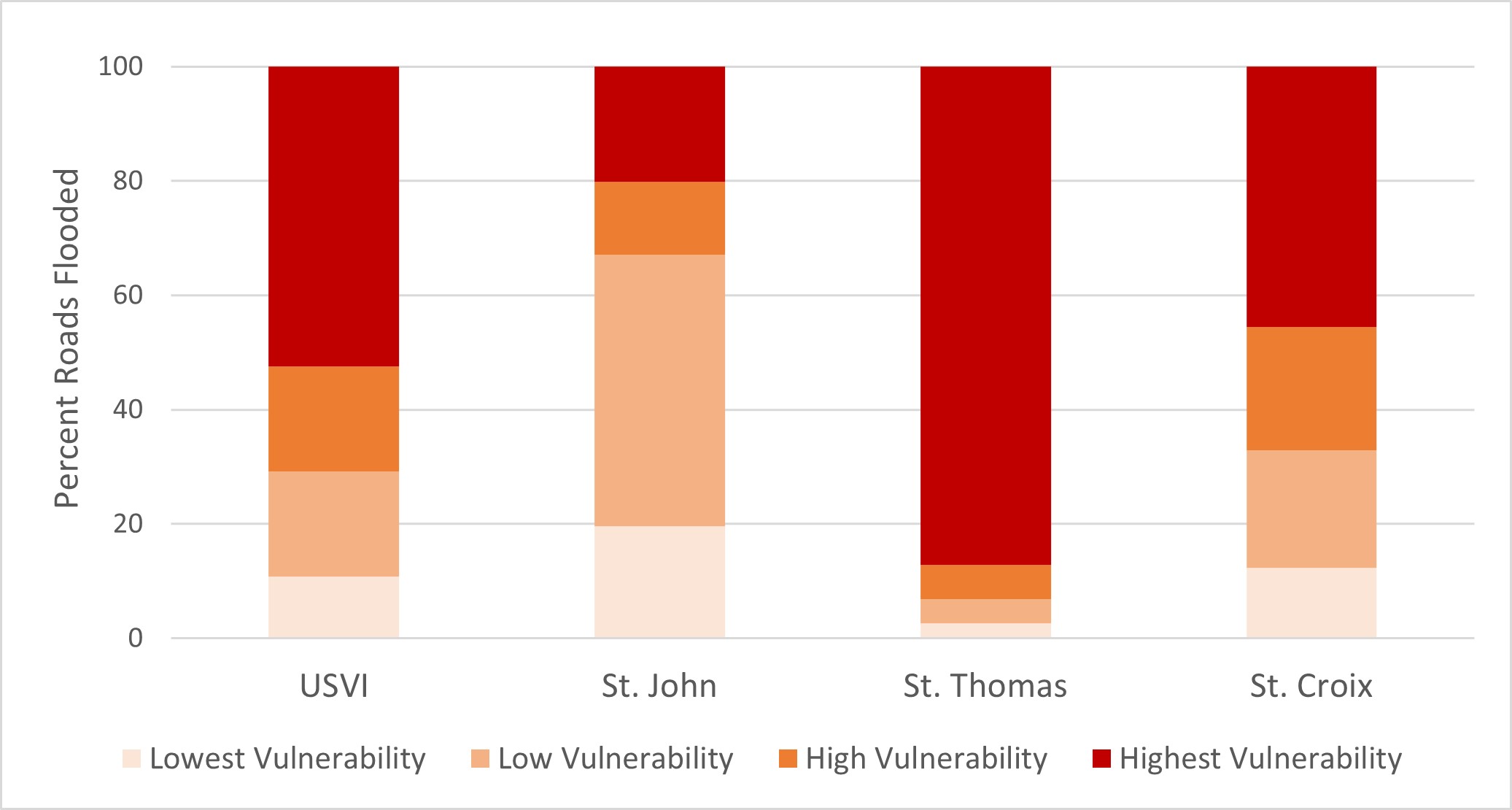

Looking at the transportation impact, we find similar patterns (see Figure 9b). Territory-wide, 52% of flooded roads are where people with the highest social vulnerability live. The islands with the highest concentration of roads in flood zones affecting populations with high social vulnerability are St. Thomas (87%) and St. Croix (46%). In contrast, on St. John, people with the lowest social vulnerability are more likely to experience flooded roads.

Conclusions

Implications for Public Health

The most obvious implication for public health is the fact that many of the people who live or have to travel through flood zone also have a high social vulnerability. These areas tend to be in and around Whim on St. Croix; in Bovoni, Charlotte Amalie and Smith Bay on St. Thomas; and Cruz Bay on St. John. These areas also tend to be more populated and urbanized (see Figure 2), which increases the risk of contamination and injury from chemicals and sewage overflow in case of a flood as the USVI suffers from a deficient wastewater system (USVI Hurricane Recovery and Resilience Task Force, 201851).

Finally, as Figure 10 displays, our analysis indicates that there is significant correlation between social vulnerability and low air quality and noise. On St. Croix, most of the regions of higher social vulnerability are located downwind of an industrial area that has a refinery and a landfill. This refinery has been cited by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency multiple times in the past for air quality violations (i.e., U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 202152) and the landfill has experienced many fires (Virgin Islands Waste Management, 202253). Also, people living in the estates in the Christiansted region, which our results showed had higher social vulnerability, are surrounded by an active urban center with heavy industries—ports, fossil fuel power plants, seaplane port, desalination plant, etc.—which tend to emit a lot of pollutants and noise (see Figure 10). Similarly, on St. Thomas, the Bovoni area is where a landfill is located, and it is a main transportation corridor. Charlotte Amalie is also a main transportation corridor, home to the cargo and cruise ship port, airport, fossil fueled power plant, and many other small manufacture plants.

Figure 10. Social Vulnerability of Estates with Noise and Air Pollution Sources

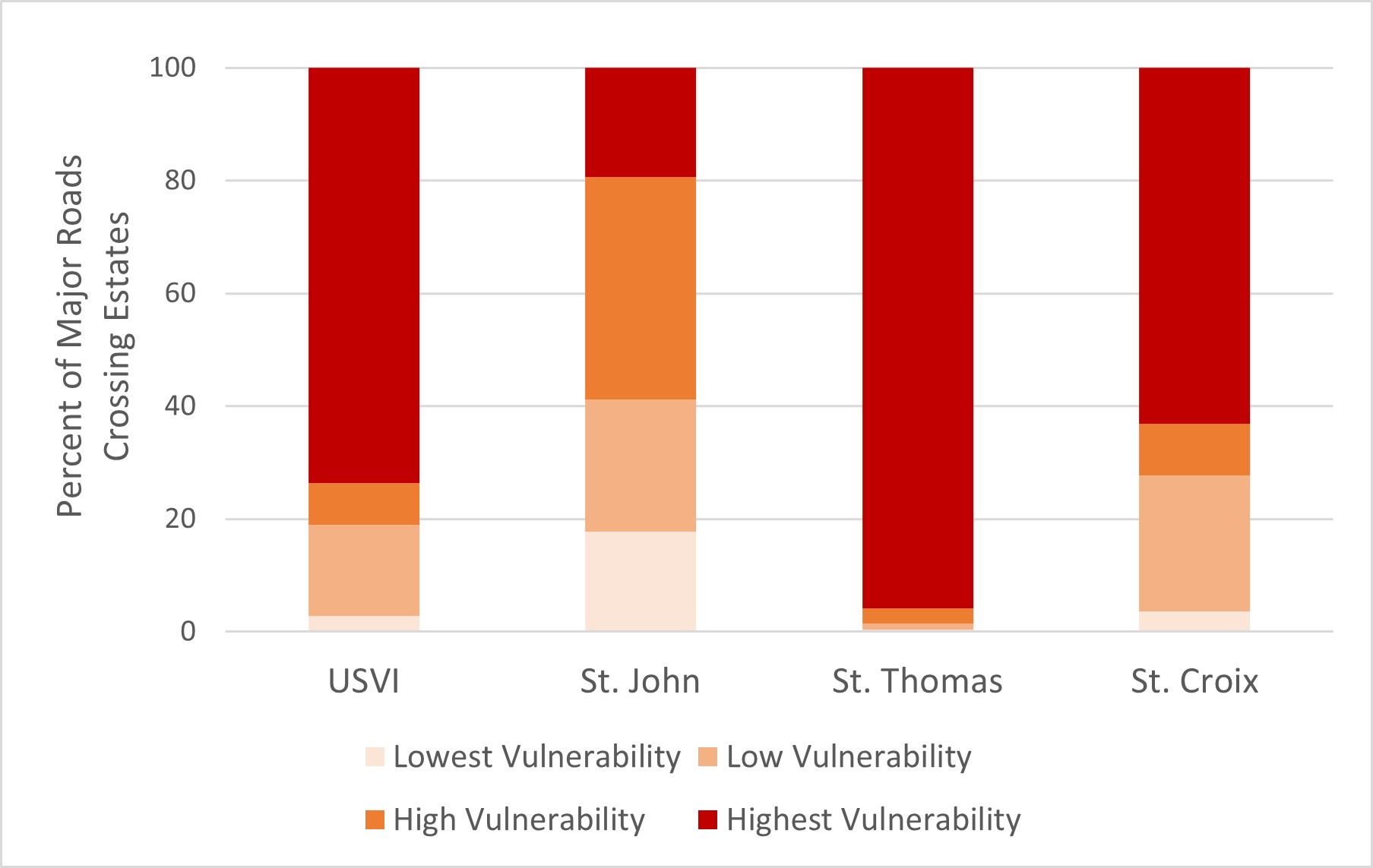

Finally, we find that the majority (74%) of primary roads (federal roads and multilane roads) tend to be more concentrated in regions of higher social vulnerability (see Figure 11), especially on St. Thomas (96%) and St. Croix (63%). St. John distribution seems to be relatively even, which can be explained by the fact that many major roads cross through the National Park. Although no data exist on the effects of these noise from ports, airports, and roads on communities in the USVI, it is likely that they experience negative health impacts (Basner et al., 201454; Lim et al., 201855; van Kamp & Davies, 201356).

Figure 11. Share of Major Highways and Primary Roads Passing Through Estates of Varying Vulnerability

Other Implications for Practice

The USVI Social Vulnerability Index has many implications for various agencies responsible for hazard mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery that could improve the quality of service received by vulnerable people in exposed locations. Agencies can use the maps to identify critical areas to set up shelters for disasters that will service the largest number of vulnerable people without placing them at greater risk by setting the shelter in a flood zone ( CDC, 2022). They can also use this information to promote, host preparedness events, and/or distribute resources in advance of hazardous events. Examples include geographically/locally tailored and language-diverse (to include Spanish and French) materials or workshops regarding how to reduce standing water after a storm to prevent mosquitoes from thriving and possibly carrying disease to the people; trainings to show how to distribute sandbags to protect property from floodwaters, etc. In the wake of a hazardous event, socially vulnerable hotspots could be highlighted for Federal Emergency Management Agency Public Assistance grants and establishing Points of Distribution during disaster recovery. The social vulnerability results can inform priority areas to check for damage to critical infrastructure, people who are hurt or in danger, and areas where the loss of electricity and water, often disrupted or damaged during an event, will have a severe impact on already vulnerable populations less equipped to cope with service loss.

Policy Applications

The results presented can be used to craft better regulations to prevent adverse health effects of hazard or land use practices. These include ensuring that those industrial activities do not impact air and noise quality by crafting appropriate mitigation and treatment strategies. They also include reducing the compounding effect in some regions of both flood, noise, and air quality risk. Results can also help craft better policy to increase the resilience of these communities and decrease their vulnerability. This can include changing land use planning practices that concentrate people of lower socioeconomic status in one location (Tate et al., 201057; Horney et al., 2017). Mix-development areas and mixing low-income housing in more diverse neighborhoods has proved to increase economic outlook of those people living in these low-income households (Brophy & Smith, 199758; Metzger & Webber, 201859). Other strategies include activities to increase the economic competitiveness or improving the quality of the housing stock of those regions.

Limitations and Strengths

Results presented in this report are consistent with the authors’ impressions of the social vulnerability of the USVI. However, for the first time, the intuitive understanding of many has been quantified and mapped using a rigorous approach. The findings also highlight the fact that although many places with disadvantaged populations are in the flood zone, many of other places in the flood zone are not home of the most disadvantaged. Not all socially vulnerable populations will suffer further harm during flood events. However, it is still important to ensure that those who are in the flood zone receive the proper level of protection.

Nevertheless, the results presented herein will need to be updated soon. We computed the Social Vulnerability Index using the 2010 Census data because the 2020 Census is not yet available, and the territory experienced a significant population shift following the 2017 hurricanes (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Another weakness of the results is that they are at the estate level, and not census tracts. The estates, especially on St. Thomas where they are larger than on the other islands, are often homes to people who experience very different socioeconomic realities. Unfortunately, there are no publicly available data that helps address these limitations.

Future Research Directions

More research is needed to better understand the drivers of social vulnerability in the USVI. Although it is not surprising that outputs from the different themes are different, it is still surprising that there is so much variation in the spatial distribution of the different theme outputs. We are planning to conduct a more rigorous statistical analysis of drivers of vulnerability in the near future. We also expect to relate the data shown to some of the social determinants of health and “cues to care” variables such as green space, access to health care practices, etc. (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 202260). We will publish results of these additional analyses in a peer reviewed publication. In addition to refining the vulnerability index, more research might also be needed to characterize the state of the infrastructure in those areas of higher vulnerability to understand whether those communities are at higher risk than others.

References

-

Méndez-Lázaro, P. A., Bernhardt, Y. M., Calo, W. A., Pacheco Díaz, A. M., García-Camacho, S. I., Rivera-Lugo, M., Acosta-Pérez, E., Pérez, N., & Ortiz-Martínez, A. P. (2021). Environmental stressors suffered by women with gynecological cancers in the aftermath of hurricanes Irma and María in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111183 ↩

-

Goldmann, E., & Galea, S. (2014). Mental Health Consequences of Disasters. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435 ↩

-

Bland, S. H., O’Leary, E. S., Farinaro, E., Jossa, F., & Trevisan, M. (1996). Long-Term Psychological Effects of Natural Disasters. Psychosomatic Medicine, 58(1), 18–24. ↩

-

Makwana, N. (2019). Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(10), 3090–3095. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19 ↩

-

Flanagan, B. E., Gregory, E. W., Hallisey, E. J., Heitgerd, J. L., & Lewis, B. (2011). A Social Vulnerability Index for Disaster Management. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1792 ↩

-

Mills, F., Bellew, A., Williams-Liburd, D., Jean-Charles, C., Johnson-Rogers, M., & Henry, S. (2018). 2015 United States Virgin Islands Community Survey. Eastern Caribbean Center, University of the Virgin Islands. https://uvi.edu/research/eastern-caribbean-center/documents.aspx ↩

-

Nunez-Smith, M., Bradley, E. H., Herrin, J., Santana, C., Curry, L. A., Normand, S.-L. T., & Krumholz, H. M. (2011). Quality of Care in the US Territories. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(17), 1528–1540. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.284 ↩

-

St. Croix Foundation for Community Development. (2021). Kids Count USVI 2021 Data Book: Building Level Pathways for Our Children. https://www.stxfoundation.org/st-croix-foundation-releases-the-2021-kids-count-usvi-data-book/ ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2014, March). U.S. Virgin Islands Demographic Profile Summary File—2010 Census of Population and Housing. Technical Documentation DPSFVI/10-3 (RV). Retrieved from https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2010/technical-documentation/complete-tech-docs/island-areas/us-virgin-island/dpsfvi.pdf ↩

-

Wang, K. H., Hendrickson, Z. M., Friedman, H. R., Nunez, M. A., & Nunez-Smith, M. (2020). Improving US Virgin Islands’ heath system: “You get more benefits with your insurance in the States than you get here” medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.02.20135657 ↩

-

U.S. Virgin Islands Department of Health. (2020). United States Virgin Islands Community Health Assessment. https://doh.vi.gov/community-health-assessment-report ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2008). Hazard Mitigation Planning. http://www.fema.gov/plan/mitplanning/index.shtm ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2018). An affordability framework for the national flood insurance program. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/Affordability_april_2018.pdf ↩

-

Fordham, M., Lovekamp, D., & Phillips, B. (2013). Understanding Social Vulnerability. In D.S.K. Thomas, B.D. Phillips, W.E. Lovekamp, A. Fothergill (Eds.), Social Vulnerability to Disasters (pp. 1–29). CRC Press. ↩

-

Kuhlicke, C., Scolobig, A., Tapsell, S., Steinführer, A., & De Marchi, B. (2011). Contextualizing social vulnerability: findings from case studies across Europe. Natural hazards, 58(2), 789-810. ↩

-

King, D., & MacGregor, C. (2000). Using social indicators to measure community vulnerability to natural hazards. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The, 15(3), 52-57. ↩

-

Tapsell, S. M., Penning-Rowsell, E. C., Tunstall, S. M., & Wilson, T. L. (2002). Vulnerability to flooding: health and social dimensions. Philosophical transactions of the royal society of London. Series A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 360(1796), 1511-1525. ↩

-

Cutter, S. L., Boruff, B. J., & Shirley, W. L. (2003). Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Social science quarterly, 84(2), 242-261. ↩

-

Wu, S. Y., Yarnal, B., & Fisher, A. (2002). Vulnerability of coastal communities to sea-level rise: a case study of Cape May County, New Jersey, USA. Climate research, 22(3), 255-270. ↩

-

Chang, S. E., Yip, J. Z., van Zijll de Jong, S. L., Chaster, R., & Lowcock, A. (2015). Using vulnerability indicators to develop resilience networks: a similarity approach. Natural Hazards, 78(3), 1827-1841. ↩

-

Alwang, J., Siegel, P. B., & Jorgensen, S. L. (2001). Vulnerability: A view from different disciplines (English). Social protection discussion paper series. World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/636921468765021121/Vulnerability-a-view-from-different-disciplines ↩

-

Schmidtlein, M. C., Deutsch, R. C., Piegorsch, W. W., & Cutter, S. L. (2008). A sensitivity analysis of the Social Vulnerability Index. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 28(4), 1099-1114. ↩

-

Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program. (n.d.) At A Glance: CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved June 10, 2022 from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/at-a-glance_svi.html ↩

-

Paulino, Y., Badowski, G., Chennaux, J., Guerrero, M., Cruz, C., King, R., & Panapasa, S. (2021). Calculating the Social Vulnerability Index for Guam. Natural Hazards Center Public Health Grant Report Series, 12. Boulder, CO: Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. Available at: https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/calculating-the-social-vulnerability-index-for-guam ↩

-

Tormos-Aponte, F., García-López, G., & Painter, M. A. (2021). Energy inequality and clientelism in the wake of disasters: From colorblind to affirmative power restoration. Energy Policy, 158, 112550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112550 ↩

-

Weis, S. W. M., Agostini, V. N., Roth, L. M., Gilmer, B., Schill, S. R., Knowles, J. E., & Blyther, R. (2016). Assessing vulnerability: an integrated approach for mapping adaptive capacity, sensitivity, and exposure. Climatic Change, 136(3), 615-629. ↩

-

Benson, P. P. C. (2013). Macro-economic concepts of vulnerability: Dynamics, complexity and public policy. In G. Bankoff, G. Frerks., & D. Hilhorst (Eds.), Mapping Vulnerability: Disasters, Development, and People (pp. 178-192). Routledge. ↩

-

Wood, E., Sanders, M., & Frazier, T. (2021). The practical use of social vulnerability indicators in disaster management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 63, 102464. ↩

-

Lue, E., & Wilson, J. P. (2017). Mapping fires and American Red Cross aid using demographic indicators of vulnerability. Disasters, 41(2), 409-426. ↩

-

Horney, J., Nguyen, M., Salvesen, D., Dwyer, C., Cooper, J., & Berke, P. (2017). Assessing the quality of rural hazard mitigation plans in the southeastern United States. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 37(1), 56-65. ↩

-

Tate, E., Rahman, M. A., Emrich, C. T., & Sampson, C. C. (2021). Flood exposure and social vulnerability in the United States. Natural Hazards, 106(1), 435-457. ↩

-

Platt, R. H. (1998). Planning and land use adjustments in historical perspective. Cooperating with nature: Confronting natural hazards with land-use planning for sustainable communities. National Academies Press. ↩

-

Lee, D., & Jung, J. (2014). The growth of low-income population in floodplains: A case study of Austin, TX. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 18(2), 683-693. ↩

-

Rolfe, M. I., Pit, S. W., McKenzie, J. W., Longman, J., Matthews, V., Bailie, R., & Morgan, G. G. (2020). Social vulnerability in a high-risk flood-affected rural region of NSW, Australia. Natural Hazards, 101(3), 631-650. ↩

-

Qiang, Y. (2019). Disparities of population exposed to flood hazards in the United States. Journal of Environmental Management, 232, 295-304. ↩

-

Laska, S., & Morrow, B. H. (2006). Social vulnerabilities and Hurricane Katrina: An unnatural disaster in New Orleans. Marine technology society journal, 40(4), 16-26. ↩

-

Adeola, F. O., & Picou, J. S. (2012). Race, social capital, and the health impacts of Katrina: Evidence from the Louisiana and Mississippi Gulf Coast. Human Ecology Review, 19(1), 10-24. ↩

-

Collins, T. W., Jimenez, A. M., & Grineski, S. E. (2013). Hispanic health disparities after a flood disaster: results of a population-based survey of individuals experiencing home site damage in El Paso (Texas, USA). Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15(2), 415-426. ↩

-

Emrich, C. T., Tate, E., Larson, S. E., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Measuring social equity in flood recovery funding. Environmental Hazards, 19(3), 228-250. ↩

-

Adger, W. N., Brooks, N. Bentham, G., Agnew, M., & Eriksen, S. (2004). New indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity Norwich: Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research. ↩

-

United States Virgin Islands (2022, June 29). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=United_States_Virgin_Islands&oldid=1079278239 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021, October 28). Census Bureau Releases 2020 Census Population and Housing Unit Counts for the U.S. Virgin Islands. (Press Release Number CB21-TPS.74). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021/2020-census-us-virgin-islands.html ↩

-

University of the Virgin Islands. (2022). Eastern Caribbean Center. https://www.uvi.edu/research/eastern-caribbean-center/default.aspx ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Planning for an Emergency: Strategies for Identifying and Engaging At-Risk Groups. A guidance document for Emergency Managers. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/hsb/disaster/atriskguidance.pdf ↩

-

Hazard Mitigation and Resilience Planning team. (n.d.) Flood maps. Retrieved June 10, 2022, from resilientvi.org ↩

-

Strategic Alliance for Risk Reduction (STARR). (2018). U.S. Virgin Islands Advisory Data and Products Post-Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Federal Emergency Management Agency. ↩

-

Dookhan, I. (1994). A History of the Virgin Islands of the United States. University Press of the West Indies. ↩

-

Krigger, M. (2017). Race Relations in the US Virgin Islands. Carolina Academic Press. ↩

-

Virgin Islands Housing Finance Authority. (2020). United States Virgin Islands Disaster Recovery Action Plan. https://cdbgdr.vihfa.gov/contracts/action-plan/ ↩

-

U.S. Virgin Islands Hurricane Recovery and Resilience Task Force. (2018). Final Report. https://first.bloomberglp.com/documents/257521_USVI_Hurricane+Recovery+Taskforce+Report_DIGITAL.pdf ↩

-

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2021). Limetree Bay Terminals and Limetree Bay Refining, LLC (U.S. Virgin Islands) [Overviews and Factsheets]. https://www.epa.gov/vi/limetree-bay-terminals-and-limetree-bay-refining-llc ↩

-

Virgin Islands Waste Management. (2022). Fire-Virgin Islands Waste Management. http://www.viwma.org/index.php/component/search/?searchword=fire&searchphrase=all&Itemid=437 ↩

-

Basner, M., Babisch, W., Davis, A., Brink, M., Clark, C., Janssen, S., & Stansfeld, S. (2014). Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. The Lancet, 383(9925), 1325–1332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61613-X ↩

-

Lim, J., Kweon, K., Kim, H.-W., Cho, S. W., Park, J., & Sim, C. S. (2018). Negative Impact of Noise and Noise Sensitivity on Mental Health in Childhood. Noise & Health, 20(96), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.4103/nah.NAH_9_18 ↩

-

van Kamp, I., & Davies, H. (2013). Noise and health in vulnerable groups: A review. Noise and Health, 15(64), 153. https://doi.org/10.4103/1463-1741.112361 ↩

-

Tate, E., Cutter, S. L., & Berry, M. (2010). Integrated multihazard mapping. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 37(4), 646-663. ↩

-

Brophy, P. C., & Smith, R. N. (1997). Mixed-Income Housing: Factors for Success. Cityscape, 3(2), 3–31. ↩

-

Metzger, M. W., & Webber, H. S. (2018). Facing Segregation: Housing Policy Solutions for a Stronger Society. Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2022). Social Determinants of Health—Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health ↩

Guannel, G., Lohmann, H., & Dwyer, J. (2022). The Public Health Implications of Social Vulnerability in the U.S. Virgin Islands (Natural Hazards Center Public Health Disaster Research Report Series, Report 23). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/the-public-health-implications-of-social-vulnerability-in-the-u-s-virgin-islands