Community-Based Organization Cultural Brokering

A Case Study of the Almeda Fire

Publication Date: 2025

Abstract

This report describes a qualitative case study of community-based organizations (CBOs) that provided recovery services to Latino/LatineEndnote 1 wildfire survivors in Jackson County, OR, after the Almeda Fire of 2020. For the study, I conducted 23 in-depth interviews, three focus groups, a document review, and participant observation with CBOs serving low-income communities of color. The purpose of the study was to examine the role of CBOs as cultural brokers between Latino/Latine survivors of the Almeda Fire and traditional recovery culture. Traditional recovery culture refers to institutionalized ways in which disaster recovery is understood, practiced, and managed, typically embodied by disaster management agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency, large-scale disaster relief funders, and state agencies. These CBOs served as cultural brokers, helping survivors and personnel in these large agencies communicate across their cultural divide by translating, mediating, and negotiating resource access. Findings demonstrated that this cultural navigation occurred both uni-directionally—meaning CBOs translated traditional recovery cultural norms to Latino/Latine survivors—and bi-directionally—meaning there were instances where Latino/Latine survivor culture was able to inform and transform conventional recovery practices and culture. Preliminary analysis indicates that most CBOs in Jackson County operated within a unidirectional cultural brokering path. However, some CBOS used culturally responsive programming that leveraged local cultural knowledge and created opportunities for bidirectional cultural brokering. Despite challenges around CBO-community trust and power differentials, the engagement of culturally rooted disaster resilience holds promise for facilitating mutual learning between diverse community practices and external partners.

Introduction

During the 2020 Oregon wildfire season, the state struggled with extensive drought conditions and historically low fuel moistures and relative humidity, leading to the emergence of five simultaneous megafires larger than 100,000 acres each (Newburger, 20201). These fires rapidly grew within a span of three days, ranking them one of Oregon's top 20 largest wildfires since 1900 (Oregon Department of Forestry, 20222). The Almeda Fire in rural Southern Oregon was particularly devastating. On September 8, 2020, the Almeda Fire rapidly moved through the Rogue Valley leaving a trail of destruction in Ashland, Talent, Phoenix, and Medford, Oregon. While its acreage was comparatively small relative to other wildfires that season, the Almeda Fire surpassed all other Labor Day Fires in 2020 combined in terms of homes burned (McCall, 20223), including many impacted manufactured homes without fire insurance (Vaughan, 20224). Many of these homes belonged to Latino/LatineEndnote 1 families, the majority of whom predominantly spoke only Spanish within their households (Schmidt, 20205). Multiple residents suffered direct and indirect financial, physical, and mental health losses from the Almeda Fire (Frail & Cozad, 20226).

Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) are public, non-profit, or not-for-profit entities that provide responsive services to their community, characterized by local leadership and staffing, community-driven priority setting, and resident involvement from program design to evaluation (Community-Based Public Health Caucus, n.d.7). For the purposes of this report, culturally responsive CBOs are characterized by the following: (a) they are primarily made up of local Latino/Latine community leaders or staff, (b) they integrate cultural knowledge, practices, and norms into their disaster programming, and (c) they primarily serve their local Latino/Latine communities. During the 2020 Labor Day Fires, culturally responsive CBOs serving Latino/Latine communities identified how shortcomings in communications, evacuation, shelter, and other wildfire response systems had limited their capacity to address community needs (United Way of the Columbia-Willamette, 20218). Many wildfire survivors, including many from the Latino/Latine communities, are still recovering from the long-lasting impact of the Almeda Fire (Neumann, 20239). Culturally responsive CBOs continue to support the recovery of Latino/Latine residents who were impacted.

The purpose of this research was to explore the role that culturally responsive CBOs played in fire recovery among the Latino/Latine communities in Phoenix and Talent, Oregon, with a cultural and historical trauma lens. Disaster recovery work has been slow to integrate local culturally responsive systems, community trauma, and the emotional impact of disasters into its practice (Russo & da Rosa, 202310). By examining the role of culturally responsive CBOs as cultural brokers between government systems and disaster-impacted marginalized communities after the Alameda fire, this report aims to identify the risks and opportunities that CBOs experience in wildfire recovery programming in partnership with local funders, government departments, government representatives, other culturally responsive CBOs, and non-culturally responsive CBOs.

Literature Review

The Role of Community-Based Organizations in Disaster Resilience

Disaster-impacted communities of color experience significant recovery disparities, such as violent evictions (Betteridge, 2019 11), limited financial opportunities (Jacobs, 201912), and inequitable access to relief funds (Rivera et al., 202213). Disaster management governmental agencies can benefit from working with community collaborators to address these disparities. CBOs serving communities of color are well-situated to recognize and address these pre-existing and disaster outcome disparities. These organizations mediate and advocate between funding agencies (e.g., philanthropy, state authority, etc.) and community members. Collaborating with local organizations can improve community member engagement in disaster preparedness activities, ensure more targeted distribution of resources and disaster-related information, and improve community capacity to respond to disasters (Chi et al., 201514). In turn, depending on the strength and nature of this collaborative effort, these partnerships have the potential to channel crucial feedback and community-based knowledge about the efficacy, relevancy, and cultural safety of disaster recovery efforts (Tom & Kim, 202415). Through their community-driven initiatives, CBOs are well-situated to leverage culturally rooted knowledge in communities most impacted by disasters.

Despite their potential, research has yet to explore what challenges CBOs experience in receiving local government support for culturally responsive disaster recovery. A critical examination of how CBOs harness local cultural knowledge can help mitigate risks and empower autonomous CBOs in addressing disaster recovery disparities within Latino/Latine communities in rural areas.

Historical Trauma

Historical trauma theory recognizes that populations historically have been subjugated to long-term, mass trauma (e.g., genocide, cultural colonization, forced migration, etc.), which continues to influence health outcomes, culture, and other multilevel structural determinants of health (Danieli, 199816). This theory offers wildfire recovery work a temporal lens for understanding the subjugation of communities of color, intergenerational trauma in both body and culture, and how disasters create a unique widespread experience of trauma across populations (Danieli, 1998; Sotero, 200617). Historical trauma theory correlates militaristic disaster responses with re-traumatization from forced displacement (Boyd et al., 201018), erasure or appropriation of cultural responses to disasters (Humbert & Joseph, 201919), and the absence of agency and decision-making power in the implementation of disaster responses (Jacobs, 2019).

Culturally responsive recovery programming must also consider how historical trauma compounds disaster induced collective trauma. While disaster practice leans towards individual trauma, there is less intervention addressing collective trauma—the effects disasters have at a community level (Somasundaram, 201420). Collective trauma refers to the challenges traumatized communities face when their interlinked systems are disrupted or dissolved post-event (Somasundaram, 2014; Thamotharampillai & Somasundaram, 202121). Wildfires can suddenly remove one or more interlinked systems which can drastically change how these systems function, resulting in health, social, and response and recovery resource issues (Rosenthal et al., 202122).

The Cultural Broker Model

Culture is crucial in disaster recovery, constituting a foundational domain in recovery interventions. Culture is broadly understood as being entangled with ontological and epistemological perspectives, meaning that culture serves as a paradigm for experiencing the world. Culture has a temporal lens to survival, with social norms passed down to the next generation for use and preservation (Hall, 200323). Culture frames how to approach disaster work, shaping community risk perception and influencing responses from preparation to structural transformation (Krüger et al., 201524). For wildfire recovery, culture remains at the core—shaping the identification of resources, how recovery is defined and understood, and the methods of recovery.

The Cultural Broker model—which was developed by Browne (201525) to describe the cultural needs of Hurricane Katrina survivors—offers a theoretical framework for understanding how culturally responsive CBOs operate in wildfire recovery, namely by mediating communication and interactions between institutions practicing recovery culture and communities practicing wounded culture. Browne (2015) defines recovery culture as the institutionalized ways in which disaster recovery is understood, practiced, and managed by disaster response and recovery organizations—such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency, American Red Cross, recovery funding organizations, and state agencies. In contrast, wounded culture encompasses how disaster-stricken community members understand and practice recovery, grief, trauma, and healing. In this model, cultural brokers act as intermediaries—communicating insights between the two groups and translating essential information across this cultural divide. However, because non-tangible cultural resources rarely receive attention in disaster scholarship, the value that cultural brokers could bring to recovery efforts is unexplored (Browne, 2015).

Defining Culturally Responsive Community-Based Organizations

While Browne (2015) examined how family members with more experience in institutional norms (e.g., tracking agencies, following up on claims) served as cultural brokers for their relatives, this study extended this concept to examine how culturally responsive CBOs operate in this role. For the purpose of this report, I defined culturally responsive CBOs as CBOs that met the following criteria: First, they primarily worked with Latino/Latine communities in Jackson County, Oregon. Second, they identified their services as culturally responsive. Third, their programming was delivered by bicultural and bilingual staff and/or their organization was led by and designed for Latino/Latine residents. These CBOs were a small subset of CBOs providing disaster programming in Jackson County, OR. While there were other CBOs involved in this work, referred to as local CBOs in this report, these CBOs provided general disaster recovery services for all Almeda wildfire survivors and did not necessarily have programming specifically for Latino/Latine communities or meet all the criteria listed above. At times, these local CBOs and culturally responsive CBOs would collaborate to provide joint disaster programming, such as staffing a community resource fair, to combine staff and resource capacity. In addition, I used a historical trauma lens to assess how CBOs translated resources and buffered against institutionalized harm inherent in recovery culture to those in wounded culture.

Research Questions

Two questions guided this study:

How, and to what extent, do CBOs working with low-income Latino/Latine communities affected by the 2020 Alameda Fire use their cultural knowledge to serve as cultural brokers for members of those communities to traditional disaster recovery organizations?

What challenges do these CBOs encounter as cultural brokers?

Research Design

To address these research questions, I conducted a qualitative case study of culturally responsive CBOs and actors supporting Latino/Latine wildfire survivors recovering from the Almeda Fire in Jackson County, Oregon. Research participants included Latino/Latine recipients of culturally responsive wildfire recovery programming, culturally responsive CBO staff, and representatives of local CBOs, government, and philanthropic organizations.

Study Site and Context

Jackson County, Oregon

Jackson County, Oregon, has a population of approximately 223,000 (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.26). The Latino/Latine communities comprise 14.5% (n=32,942) of the population and grew by 50.5% between 2010 to 2022 (USA Facts, 202227), making them the second largest ethnic group in the county. While Latino/Latine individuals in Oregon have higher labor force participation after non-Hispanic Whites, they experience higher unemployment rates and lower incomes, partly due to lower educational attainment (Ruffenach et al., 201628; Lehner, 202329). The agricultural industry, spanning 170,298 acres and generating $71 million annually, relies heavily on year-round Latino/Latine farmworkers (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 201730). However, Jackson County faces significant housing challenges, with approximately half of renters being cost burdened, paying 30-49% of their income for housing (ACCESS, 2023 31).

The Almeda Fire

On September 8, 2020, the Almeda Fire swept through Phoenix and Talent in Jackson County, OR. County estimates reveal the destruction of 2,357 residential structures, a staggering 75% (about 1,748 units) of which were manufactured homes located in a dozen mobile home parks along Oregon 99 and Interstate 5 (Crombie, 202032). These parks mostly housed older adults, Latino/Latine families with household members employed in local businesses and farms and housekeepers and childcare providers employed in nearby Ashland who sought affordable housing. The fire’s impact was far-reaching, with authorities estimating that around 6,000 residents were displaced (Martinez-Medina et al., 202333). The Phoenix-Talent School District, where 40% of students are Latino/Latine, reported that approximately 1,000 students lost their homes and were subsequently scattered across the region (Crombie, 2020).

Interviews and Focus Groups

For this study I conducted 23 interviews and three focus groups. As Table 1 shows, interviewees included nine staff members from culturally responsive CBOs serving Latino/Latine Almeda Fire survivors, three representatives of philanthropic organizations, two local teachers, four government representatives, three staff members from local CBOs (i.e., CBOs partnering with culturally responsive CBOs), and one independent clinical social worker who collaborated on wildfire recovery with multiple culturally responsive CBOs. Most interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes and were conducted over Zoom or in-person, in accordance with the participant’s preference.

Table 1. Description of Interview and Focus Group Participants

| Government Representative | 1 official elected to state government 3 officials elected to local government |

|

| Philanthropic Organization | Employed at 2 separate philanthropic organizations | |

| Local Community-Based Organization (CBO) | Employed at 3 separate local CBOs | |

| Culturally Responsive Community-Based Organization (CBO) | Employed at 6 separate Latino/Latine CBOs | |

| Community Member | Latino/Latine wildfire survivors | |

| Other Professional/ Teacher | Individuals partnering with 2 Latino/Latine CBOs | |

| Total |

The three focus groups were conducted in Spanish with a total of 12 recipients of services from culturally responsive CBOs or local CBOs. These focus groups lasted from 90 minutes to 2 hours. Because I do not speak Spanish, I collaborated with local facilitators, who were not affiliated with a culturally responsive CBO, to conduct the focus groups in-person with an interview guide. I provided context for the study and brief training facilitation as needed though these individuals had a history of facilitating groups independently. I was present for all focus groups to provide additional support and answer questions as needed.

Recruitment and Consent

I recruited participants using snowball sampling. All interviewees were recruited through personal invitation or a connection from another participant. I collaborated with local and culturally responsive CBOs to recruit focus group members via a flier, email, or direct invitation.

At the outset of the interviews and focus groups, I described the nature of the research and its potential risks and benefits. All participants provided verbal consent to participate in data collection. Because most participants had been directly impacted by the Almeda Fire, I co-created emotional safety measures with participants prior to interviewing in order to ensure that they had ways to address any emotional distress that they experienced during and after the interview. These included honoring and naming potential emotional impacts of the interview, identifying ways the interview could be paused or ended, follow-up with this investigator or trusted people if needed, and providing trauma informed care resources. For some interviews, I transitioned the discussion out of topics that were notably becoming stress activating to the interviewee. Because this study took place in a small community, I also emphasized to what degree confidentiality could be held and that I would make small modifications to stories shared if they became too specific to the individual in addition to removing demographic identifiers.

Interview Questions

All interviews and focus groups followed a semi-structured approach, including an interview guide that covered the following topics: wildfire recovery, culturally responsive wildfire recovery, culture in wildfire recovery, and challenges and successes. The Human Research Protection Program at Portland State University reviewed this research proposal and interview guide and qualified the research exempt on January 22, 2024.

Data Analysis

Virtual interviews were recorded with Zoom and in-person interviews with Recorder, a phone application. Whisper AI (Version 1.01 with the large V2 model) transcribed English interviews, and a bilingual research assistant transcribed and translated the Spanish focus groups into English with feedback from the focus group facilitators. I reviewed all transcripts for their accuracy. Because Phoenix and Talent are small, rural communities with a highly engaged interagency wildfire recovery network, some quotes were slightly altered to remove situational identifying information.

Data analysis followed iterative thematic inquiry which requires the ongoing creation and revision of themes throughout the analysis process (Morgan & Nica, 202034). This analysis is philosophically based on pragmatism, acknowledging that the investigator’s beliefs cannot be completely bracketed from data analysis. It offers a structure which continuously examines these beliefs by comparing preliminary themes to data collected. This included constant writing, reflexive memo writing, iterative coding, and switching back and forth between data collection and data analysis. Following this logic, this analysis engaged the investigator’s beliefs about the research topic to create an iterative learning process around data collected to develop the preliminary themes presented in this report.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

For the past four years, I have worked with culturally responsive CBOs throughout Oregon. I am trained as a social worker with specialization in trauma-informed clinical approaches; I have conducted consultation and trainings for organizations implementing trauma informed care and have worked in workforce wellness and culturally responsive affinity spaces for disaster leaders of color. This study grew from this work. Several key factors shape my positionality. I am a college-educated daughter of an immigrant with mixed ancestry (Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese), I have a professional background in clinical social work, and I have experience working within a community mental health practice that serves wildfire survivors and addresses worker burnout. While these lived experiences served as assets in this research context in many ways, it was crucial to acknowledge how this positionality influenced research design and site access. This recognition partially informed the selection of iterative thematic inquiry as the data analysis approach for ongoing reflection and adjustment throughout the research.

Findings

The themes presented in this report are derived from preliminary data analysis. As an initial exploration of the data, this report should be considered a snapshot of the broader investigation currently underway. The themes culminate in an analysis of cultural brokering paths, common risks, and opportunities CBOs encounter as cultural brokers, emphasizing the transformative potential of local organizations in reshaping the traditional power dynamics inherent in cultural brokering processes.

Unidirectional Cultural Brokering

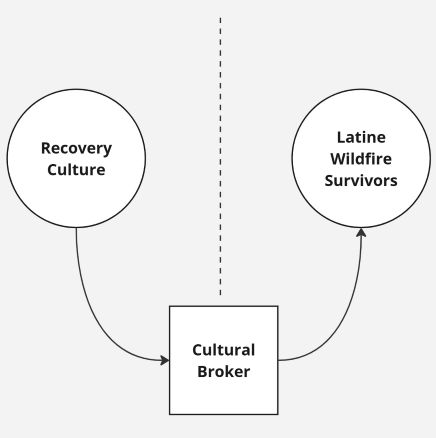

All interviewed CBO representatives, regardless of whether they explicitly identified their programming as culturally responsive, described engaging in cultural brokering to some degree. Figure 1 illustrates this process which situated these CBOs as intermediaries of recovery culture while leveraging local cultural knowledge to facilitate resource transfer. In this figure, the black arrows represented the direction of cultural translation, with recovery cultural norms and informational needs being translated through the cultural broker and then to Latino/Latine wildfire survivors. Language access and technical assistance were two identified essential cultural brokering tasks.

Figure 1. Unidirectional Cultural Brokering

Language Access

All interviewees reported language access as the primary barrier to accessing resources for Latino/Latine wildfire survivors in Phoenix and Talent. Government and funder interviewees echoed this need. Three of these entities indicated hiring bilingual staff and actively improving language access infrastructure in response to their collaborations with CBOs. This infrastructure included hiring on bilingual staff, having interpreters during public meetings, and mandating all communications be available in English and Spanish. Two entities reported already having this infrastructure in place because of pre-existing relationships with CBOs or hiring local Latino/Latine community leaders prior to the fire.

Technical Assistance

In addition to language access, most CBOs, local and culturally responsive, also collaborated with funders and governmental entities to provide technical assistance. At the time of this study, one culturally responsive CBO and two local CBOs were contracted with the state to assist Latino/Latine wildfire survivors with applying for federal housing assistance. The cultural brokering aspect of technical assistance addressed several access barriers in this community: legal literacy, technological literacy, governmental distrust, linguistic access, and cultural access. By cultural access, CBOs staff described connecting with Latino/Latine wildfire survivors through cultural belonging and knowledge to mitigate distrust and trauma while providing technical assistance. As one staff member described:

You know why they have to work in the fields with no social security number…. If you don't really personally understand that, it's a lot harder for you to connect with the participants. If you can speak the language, that’s awesome. But if you're not understanding the fear that they live in constantly, it's really hard to make that connection with them.

Hidden Loopholes

Though CBOs were well-positioned to improve resource access through their direct contact with recovery culture representatives and Latino/Latine wildfire survivors, cultural brokering appeared to be a unidirectional path from recovery culture to Latino/Latine wildfire survivors. Local CBOs and culturally responsive CBOs described efforts to improve resource accessibility (e.g., home outreach) without fundamentally altering the underlying processes. Multiple interviewees noted that funding applications, such as the Homeownership Opportunities Program or the Intermediate Housing Assistance program, often requested unrealistic or inappropriate evidence for the Latino/Latine communities. These included requesting burned documents, bank statements from individuals unable to open an account, and not accepting Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers as valid identification.

These fundamental barriers necessitated a hidden cultural brokering service by CBOs. As one interviewee stated, "[Our] organizations need to find loopholes to find help in systems that aren't designed for help." In their efforts to meet survivors' needs, some interviewees relied on conveying latent meanings when giving advice, hoping that survivors could work around the system. Yet, this innovation did not absolve incongruence between recovery culture and Latino/Latine wildfire survivors and, in some cases, caused stress activation, meaning a physiological and emotional response triggered by programming processes, at times rooted in past trauma or systemic inequities. A wildfire survivor described being denied rental assistance because they were employed and the organization providing technical assistance suggested they write a letter to explain their need. They stated,

They said I needed to write a letter saying that I had a need. I lost my house. How is that not a need? So I wrote a letter…and it felt like I was begging…And that’s something that honestly stays with community. You get into that victim mentality because in order to apply for assistance, like you literally have to be.

Although CBOs served as a protective buffer against the imposition of recovery culture, their inability to fundamentally change the process risked perpetuating harm and creating a sense of distrust. As one CBO representative observed, "There's a big distrust by anybody who is associated with any kind of government affiliate."

Rooting in Local Culture

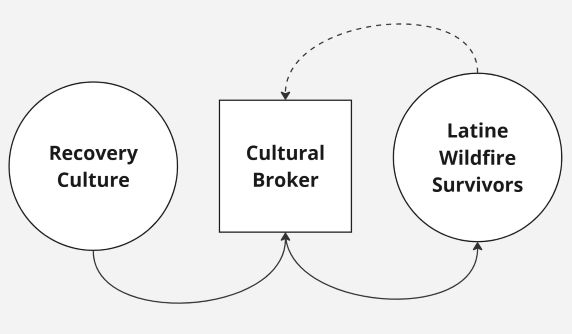

Many culturally responsive CBOs offered technical assistance and linguistic accessibility but with priorities that could reverse the cultural brokering direction. This reversal represents a shift from adapting existing recovery processes for Latino/Latine survivors to restructuring these processes based on Latino/Latine culture. Consequently, as illustrated in Figure 2, this inverted cultural brokering pathway moves Latino/Latine wildfire survivors to active agents in shaping recovery processes, centralizing their lived experiences and cultural knowledge. In Figure 2, similar to Figure 1, the black arrows represent the direction cultural translations occurs – from recovery culture to cultural broker and to Latino/Latine survivors. The dotted arrow represents the potential for this cultural translation path to be reversed, meaning Latino/Latine survivor cultures informing and reshaping cultural broker infrastructure. These priorities included nurturing relationships and trust, fostering self-efficacy and skill engagement, and growing leadership within the community.

Figure 2. Reversing the Cultural Brokering Direction

The majority of culturally responsive CBO representatives interviewed articulated that their programmatic priorities were linked to addressing the compounding effects of historical and systemic trauma on wildfire recovery within their communities. These interviewees posited that the challenges faced by their constituents were deeply rooted in intergenerational experiences of systemic marginalization, encompassing a lack of political representation, trauma associated with immigration and colonization, and persistent socioeconomic disparities, creating a complex landscape of needs that extended far beyond the scope of traditional disaster recovery frameworks. Culturally responsive programming aimed to navigate the intricate interplay between immediate post-wildfire needs and the deeper, long-standing issues that fundamentally shaped their community's capacity for recovery. This interplay was exemplified by one interviewee’s reflection:

I will give them the information that I think is going to help their problem. The problem is the following almost always will happen. They feel…either afraid or unable to deal with the system. How do you ask somebody to advocate for their rights? When everything for generations has told them not to rock the boat, how can you not be afraid?

Culturally responsive CBOs sought to embed local cultural knowledge in the disaster recovery process to address these structural barriers (e.g., civic identity loss, distrust, and grief).

Relationship-Building and Trust

While all interviewees acknowledged how relationships and trust impacted wildfire recovery, culturally responsive CBOs described a nuanced understanding of the importance of relationship and trust building in wildfire recovery programming. These organizations developed strategies to integrate this local cultural knowledge into conventional disaster relief practices to build CBO relationships and trust for future service engagement. As an example, one culturally responsive CBO that provided mental health services recognized that mental health stigma was a significant barrier to seeking help and ran a donation drive to engage the community: "We put stickers over diapers, bags, and rice…people will not come for mental health services in the middle of a disaster but they will go for a bag of rice." This culturally responsive CBO saw engagement in their services increase months later through the combination of immediate disaster relief, word-of-mouth networking, and reframing their services as “self-care” instead of mental health.

Most culturally responsive CBO interviewees described their personal commitment to their community as transcending traditional organizational boundaries. Being in organizations that encouraged them to center their lived experience as Latino/Latine wildfire survivors bridged professional services and peer support. As one interviewee noted about a particular culturally responsive CBO leader: "She stays connected with everyone. It's reciprocal and nourishes both. It's a different form of cultural resource outside of money. They know her support is forever."

Skill Building

Interviewees theorized that individual wildfire trauma and systemic trauma within the community compounds the impact of wildfires on survivors, leading to hesitance to engage recovery services. Culturally responsive CBO interviewees described prioritizing self-efficacy and skill-building components into their disaster recovery programs, addressing the long-standing traumatization within systems of disaster relief. While these approaches may not fundamentally alter conventional models of disaster resource distribution, they emerged in relation to "slow violence"— the gradual and often invisible accumulation of detrimental effects on marginalized communities (Nixon, 201135). One culturally responsive CBO representative emphasized the importance of slowing the referral process to create space for recognizing traumatization:

Hold their hand if need be. Even if it doesn't seem to be part of our job. Change is possible…It's slow, but it's beautiful…. Maybe it's not the next time but the fourth time they will go confidently and by themselves because the first three times they had support.

By shifting resources processes to Latino/Latine wildfire survivors’ time, rhythm, and capacity, culturally responsive CBOs sought to create their own systems to address immediate needs and long-term community resilience and empowerment.

Leadership

The development of community leadership emerged as a crucial strategy to indirectly address the impacts of trauma in wildfire recovery. These CBOs aimed to empower community members to actively contribute to decision-making processes to tailor programming to the local community. As one representative explained, “We did trainings on advocacy because they didn't know how to advocate for their own rights. We knew they were lacking even [feeling that they couldn’t] communicate with their elected officials.”

Other CBOs emphasized the importance of involving community members in all aspects of recovery. Two interviewees expressed concerns that statewide wildfire recovery summits lacked Latino/Latine wildfire survivor representation, citing lack of childcare, belonging, and story exploitation as deterrents to attending. By story exploitation, interviewees expressed concerns with government or local CBOs sharing stories of Latino/Latine wildfire survivors for reputation or the novelty of harm without actual benefit to survivors who shared their stories. In response, they commented,

We are planning a wildfire survivor-led retreat. We are survivors, not victims. We want to show that community can show up and be in these spaces. We want them to benefit from it. We want to give them training to help them become community leaders.

By reframing community members as survivors with decision-making power, culturally responsive CBOs actively counteracted disempowerment in the unidirectional cultural brokering path. As another culturally responsive CBO interviewee stated, "They've demonstrated that they don't need the help, but the opportunity to start again." This shift in perspective from dependency to agency recognizes the legacy of historical trauma while simultaneously shifting recovery processes to center local Latino/Latine wildfire survivor culture over recovery culture norms.

Culturally responsive CBOs transformed their role as cultural brokers by leveraging local cultural knowledge in disaster recovery. Instead of facilitating unidirectional flow from recovery agencies to Latino/Latine wildfire survivors, these organizations established bidirectional feedback paths. Their multifaceted programs address immediate disaster needs while fostering sustained community action. This approach marks a shift from traditional cultural brokering to a culturally resonant, community-led recovery framework.

Discussion

Opportunities for Cultural Brokering

Since the early 2000s there has been a significant effort to better understand how disaster resilience can be conceptualized, operationalized, and measured in communities (see examples Gowan et al., 200936; Feofilovs & Romagnoli, 201737). Through these efforts, CBOs emerged as community leaders with valuable sector-based knowledge, access to volunteers, and insights from the communities they serve, enabling them to effectively inform and operationalize disaster-related strategies (Mlcek, 201538).

Bidirectional cultural brokering presented significant opportunities for CBOs to act as decision-makers in wildfire recovery. Culturally responsive organizations described reversing the cultural brokering path to influence their own programming and actively shaping recovery culture infrastructure. In this study, a local official dedicated funding for Spanish interpretation of their meetings and hiring bilingual staff as a result of CBO cultural brokering. Local officials also reported receiving cultural awareness training from CBOs and volunteering to improve community relationships. Some Latino/Latine interviewees who transitioned from CBO work to funder positions created infrastructure within their organizations for Latino/Latine programming and leadership education. These examples suggest bidirectional cultural brokering can drive systemic changes in disaster recovery practices.

Challenges of Cultural Brokering

Cultural brokering offers CBOs the opportunity to shepherd resources to their community members through collaborations with government and funders, but also presents significant organizational risks. Cultures of non-dominant groups can clash with or be subjugated by dominant cultures which choose the governing models that favor them (Hobfoll, 200439). CBOs may also find themselves associated with or reinforcing harmful practices, potentially jeopardizing their trust with local community members. Harmful practices refer to rigid, one-size-fits-all approaches in institutionalized disaster programming that can fail to account for the specific needs, histories, and barriers faced by marginalized communities. These can include bureaucratic processes that prioritize efficiency over equity, requirements that exclude undocumented individuals from aid, or data collection practices that compromise survivor privacy and trust. When CBOs are pressured to align with these practices to maintain funding or access to resources, they may unintentionally perpetuate systemic inequities rather than addressing the unique recovery needs of their communities.

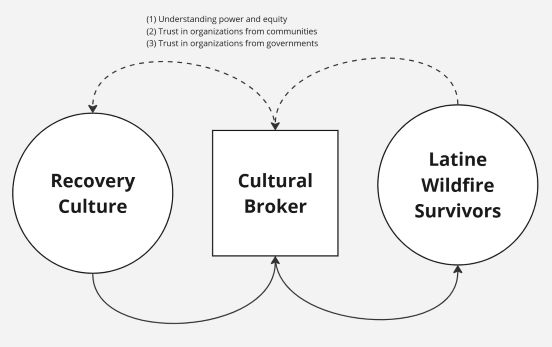

As CBOs continue to function as cultural brokers between recovery culture and disaster-impacted communities, certain factors can either support or obstruct culturally responsive programming.. First, power and equity must be considered. Repeated governmental policies and actions that disproportionately favor majority groups over low-income communities of color have sowed deep mistrust for well-intentioned governmental officials (Henkel et al., 200640). While CBOs can offer highly localized knowledge and support to communities they serve, their capacity to engage with governmental entities is limited by the same historical and political context. In this study, a CBO reported declining technical assistance funding as, "It wasn't aligning with our morals and community.” While this decision limited their funding and resources, they gained greater autonomy in their practice. Therefore, CBOs may be skeptical of partnerships with governmental agencies that might lead to the replication or reinforcement of oppressive practices.

The second issue to consider is that CBOs can maintain community trust while collaborating with recovery culture. CBOs play a crucial role in their communities, often mediating relations between service recipients and the larger U.S. society. However, this mediation has its limitations as they negotiate their civic role while translating recovery cultural norms in resource acquisition. Having bicultural and bilingual staff do not absolve CBOs of perpetuating institutionalized racism and harm themselves. In this study, one Latino/Latine wildfire survivors described a harmful interaction when requesting resources at a culturally responsive CBO reflecting, “We never returned to that organization even though we hear that this organization helps people.” CBOs can struggle with strict resource criteria, potentially reinforcing systemic harm and constraining the application of cultural knowledge in the process.

The final issue to consider in CBO cultural brokering is the CBO’s capacity to maintain its agency and leverage local cultural knowledge in their community while collaborating with recovery cultural actors. This role is contingent on their legitimacy among the community members they serve and their capacity to maintain this trust (Molden et al., 201741). In this study, one CBO, honoring Latino/Latine wildfire survivors' fear towards government, deliberately did not track resource recipients at the initial stages of wildfire recovery. While this procedure protected Latino/Latine wildfire survivors, the interviewee observed repercussions by experiencing challenges to collaborating with the state. Therefore, it is crucial that CBOs embody local cultural knowledge and priorities in their programming, even when collaborating with governmental or other institutional partners. Figure 3 provides a visualization of this balance that ensures that CBOs can effectively serve as cultural brokers while retaining the trust and legitimacy essential to their role within the Latino/Latine communities. In this figure, the black arrows continue to represent cultural translation from recovery culture to Latino/Latine wildfire survivors. However, the dotted arrows offer a visualization of the potential of CBO cultural brokering to offer cultural translation from Latino/Latine wildfire survivors to recovery culture – building a bridge in this cultural divide for both parties to inform one another.

Figure 3. Cultural Brokering Considerations

Conclusions

The aftermath of wildfires in Phoenix and Talent revealed significant challenges in wildfire recovery for Latino/Latine survivors, stemming from linguistic and cultural barriers as well as distrust towards governmental institutions. Findings suggest that CBOs played a crucial role in bridging the gap between Latino/Latine wildfire survivors and recovery resources. Collaboration between CBOs and disaster government agencies is essential for developing and implementing disaster-related strategies that are equitable, tailored to community needs, and promote long-term systematic change. The bidirectional cultural brokering model offers a promising framework for fostering powerful state-community partnerships that can effectively address the structural barriers Latino/Latine wildfire survivors face during recovery.

Implications for Practice or Policy

This study has multiple implications for disaster recovery policy and programming. Disaster recovery policies that do not account for political and historical context risk systematically disadvantaging marginalized communities while prioritizing majority groups (Rivera et al., 2022). The findings underscore the importance of institutionalizing partnerships between CBOs, funders, and government entities in wildfire recovery efforts. The bidirectional cultural brokering model offers significant policy implications for institutionalizing partnerships between CBOs, funders, and government entities in wildfire recovery efforts. This study showed that CBOs can leverage their cultural knowledge in ways that improve the services they provide. But, to be able to leverage that cultural knowledge, they need to be redesignated as decision-makers rather than solely service providers or advocates. This shift requires shared governance models where CBOs, government agencies, and funders collectively determine recovery priorities and program implementation. These shared governance models should also reflect a revision of flexible wildfire disaster recovery assessment tools that can better reflect diverse living arrangements, informal housing networks, and cultural understandings of recovery CBOs operate within. Last, similar to as seen in bi-directional cultural programming in this report, recovery culture agencies can adopt policies that prioritize long-term relationship-building with CBOs and disaster-impacted communities before a disaster occurs. Disaster recovery is more effective when systems of trust are in place before an event happens, rather than being developed reactively.

Limitations

Despite this study’s strengths, there are certain limitations to acknowledge. CBO recruitment influenced focus group attendance, potentially excluding survivors with poor trust in certain CBOs. Organizational representation was limited, with only one or two staff members interviewed per organization, with many outside of leadership positions. The diverse perspectives from different organizational levels provided a broad view of cultural brokering but may have lacked depth in specific areas. This report also presents preliminary findings. Further analysis will likely offer deeper insights into cultural brokering.

Future Research Directions

This study will continue iterative thematic inquiry data analysis. This process will allow the investigator to continue to evaluate developing themes, revise, and review the themes as systematically assessed against the collected data during coding. This process will deepen the trustworthiness and rigor of its methodology, contributing to the overall quality of the research. Final findings will be compiled into a dissertation.

A comprehensive examination of the government-CBO collaboration experiences of CBOs working with communities of color is critical for promoting meaningful state-community partnerships to build culturally grounded disaster resilience strategies. While this report offers the potential of bidirectional cultural brokering for fostering long-term institutional changes that enhance wildfire recovery for underrepresented communities, future research should explore the sustainability and scalability of such approaches across diverse disaster contexts. These disaster contexts should include an in-depth analysis of CBO-government technical assistance, public perception and trust of local CBOs engaged in wildfire recovery, and moral injury risks experienced during unidirectional cultural brokering.

Acknowledgments. I would like to thank all the incredible wildfire survivors, CBO staff, government officials, and funder staff who generously contributed time and thought to this project and Phoenix and Talent, OR recovery efforts. Additional gratitude to a certain community leader for their knowledge, wisdom, and passion for the Latino/Latine communities in Phoenix and Talent, OR, both young and old. I want to thank the Natural Hazards Center staff for selecting this project for funding, their support, and kindness during this process.

Endnote 1: I learned from my fieldwork in Jackson County that people of Latin American descent are hotly debating which term should be used to describe their ethnicity. Elders expressed strong opposition to the terms Latine and Latinx. Younger leaders were similarly opposed to the term Latino. Some younger leaders use Latinx, but others felt it had its own challenges. To respect the preferences of both groups, I chose to use Latino/Latine in this report.↩

References

-

Newburger, E. (2020 September 12). At least 33 dead as wildfires scorch millions of acres across Western U.S. – ‘It is apocalyptic.’ CNBC. Retrieved September 22, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/12/fires-in-oregon-california-and-washington-spread-death-toll-rises.html ↩

-

Oregon Department of Forestry. (2022 May). Forest Facts: 2020 Labor Day Fires: Post-fire challenges with invasive plants. Oregon Department of Forestry. Retrieved from https://oregon.gov/odf/Documents/forestbenefits/fact-sheet-labor-day-fire-weeds.pdf On 11/19/2023 ↩

-

McCall, E. (2022, October 25). The Almeda Fire. ArcGIS StoryMaps. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/152aa529aa5c4dd29165bacd60422a8f ↩

-

Vaughan, J. (2022, April 14). Oregon officials and nonprofits work on rebuilding resources for people who lost homes in Almeda fire. Oregon Public Broadcasting. https://www.opb.org/article/2022/04/14/oregon-officials-nonprofits-work-rebuild-resources-manufactured-homeowners-after-almeda-fire/ ↩

-

Schmidt, S. (2020, September 10). In a small Oregon town, a wildfire devastates a Latino community. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/09/10/wildfires-decimate-oregon-latino-community/ ↩

-

Frail, A. & Cozad, A. (2022, February 4). Wildfire Recovery: Rebuilding After a Natural Disaster. AARP Research. https://www.aarp.org/pri/topics/work-finances-retirement/financial-security-retirement/2021-jackson-county-wildfire-recovery-survey.html ↩

-

Community-Based Public Health Caucus. (n.d.). What is a CBO? University of Michigan: School of Public Health. Retrieved August 4, 2024, from https://sph.umich.edu/ncbon/about/whatis.html ↩

-

United Way of the Columbia-Willamette. (2021). Wildfire fund report 2021. https://www.unitedway-pdx.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/UWCW%20Wildfire%20Fund%20Report%20112421.pdf ↩

-

Neumann, E. (2023, September 8). Three years after wildfires, some southern Oregon survivors still struggle to recover. Oregon Public Broadcasting. https://www.opb.org/article/2023/09/08/wildfire-survivors-recovery-southern-oregon/ ↩

-

Russo, A., & da Rosa, C. (2023). Acknowledge, elevate, and reclaim: A thematic review of critical and decolonial perspectives on contemporary disaster resilience. Administrative theory & praxis, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2023.2282899 ↩

-

Betteridge, B., & Webber, S. (2019). Everyday resilience, reworking, and resistance in North Jakarta’s kampungs. Environment and planning E: Nature and space, 2(4), 944-966. ↩

-

Jacobs, F. (2019). Black feminism and radical planning: New directions for disaster planning research. Planning theory (London, England), 18(1), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095218763221 ↩

-

Rivera, D. Z., Jenkins, B., & Randolph, R. (2022). Procedural vulnerability and its effects on equitable post-disaster recovery in low-income communities. Journal of the American planning association, 88(2), 220–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2021.1929417 ↩

-

Chi, G. C., Williams, M., Chandra, A., Plough, A., & Eisenman, D. (2015). Partnerships for community resilience: Perspectives from the Los Angeles county community disaster resilience project. Public health, 129(9), 1297–1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.004 ↩

-

Tom, A., & Kim, A. (2024). Partnerships in the recovery planning process: Lessons from Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria and Irma. Disaster prevention and management: An international journal, 33(4), 321-334. ↩

-

Danieli, Y. (Ed.). (1998). International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. Springer Science & Business Media. ↩

-

Sotero, M. M. (2006) A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of health disparities research and practice 1(1), 93-108 ↩

-

Boyd, B., Quevillon, R. P., & Engdahl, R. M. (2010). Working with rural and diverse communities after disasters. In Priscilla Dass-Brailsford (Ed), Crisis and disaster counseling: Lessons learned from hurricane Katrina and other disasters, 149-163. ↩

-

Humbert, C & Joseph, J. (2019) Introduction: the politics of resilience: problematising current approaches, Resilience, (7)3, 215-223, 10.1080/21693293.2019.1613738 ↩

-

Somasundaram, D. (2014). Addressing collective trauma. Intervention: International journal of mental health, psychosocial work, and counselling in areas of armed conflict, 12(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/WTF.0000000000000068 ↩

-

Thamotharampillai, U., & Somasundaram, D. (2021). Collective trauma. In D. Bhugra, O. Ayonrinde, E. J. Tolentino, K. Valsraj, A. Ventriglio (Eds.), Oxford textbook of migrant psychiatry (pp. 105-113). Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Rosenthal, A.T., Stover, E., & Haar, R.J. (2021). Health and social impacts of California wildfires and the deficiencies in current recovery resources: An exploratory qualitative study of systems-level issues. PLoS ONE, 16. ↩

-

Hall, J. R., Neitz, M. J., & Battani, M. (2003). Sociology on culture. Psychology Press. ↩

-

Krüger, F.W., Bankoff, G., Cannon, T., Orlowski, B.M., & Schipper, E.L. (Eds.) (2015). Cultures and disasters: Understanding cultural framings in disaster risk reduction. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315797809 ↩

-

Browne, K. E. (2015). Standing in the need: Culture, comfort, and coming home after Katrina. University of Texas Press. ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). Jackson County, Oregon profile. Explore Census Data. Retrieved August 4, 2024, from https://data.census.gov/profile/Jackson_County,_Oregon?g=050XX00US41029 ↩

-

USA Facts. (2022, July). Our changing population: Jackson County, Oregon. Retrieved July 6, 2024, from https://usafacts.org/data/topics/people-society/population-and-demographics/our-changing-population/state/oregon/county/jackson-county/#racial-ethinic-population-change ↩

-

Ruffenach, C., Worcel, S., Keyes, D., Franco, R. (2016). Latinos in Oregon: Trends and opportunities in a changing state. Oregon Community Foundation. https://oregoncf.org/Templates/media/files/reports/latinos_in_oregon_report_2016.pdf ↩

-

Lehner, J. (2023, June 21). Oregon’s growing Hispanic and Latino population. Oregon Office of Economic Analysis. https://oregoneconomicanalysis.com/2023/06/21/oregons-growing-hispanic-and-latino-population/ ↩

-

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2017). 2017 Census of Agriculture: Jackson County, Oregon. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Online_Resources/County_Profiles/Oregon/cp41029.pdf ↩

-

ACCESS Community Action Agency. (2023). 2023 Community needs assessment. https://accessagency.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ACCESS-2023-Community-Needs-Assessment-7.pdf ↩

-

Crombie, N. (2020, September 27). Southern Oregon wildfire razes close-knit Latino community, thousands face housing crisis. Oregonlive. https://www.oregonlive.com/wildfires/2020/09/southern-oregon-wildfire-razes-close-knit-latino-community-thousands-face-housing-crisis.html ↩

-

Martinez-Medina, J., Kumar, M., Ledesma, E., García, C., & García, N. A. (2023). Southern Oregon housing study: The Almeda Fire impact on our Latinx community. Coalición Fortaleza. https://casaoforegon.org/southern-oregon-housing-study-the-almeda-fire-impact-on-our-latinx-community ↩

-

Morgan, D. L., & Nica, A. (2020). Iterative thematic inquiry: A new method for analyzing qualitative data. International journal of qualitative methods, 19, 160940692095511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920955118 ↩

-

Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press. ↩

-

Gowan, M. E., Kirk, R., Johnston, D., Ronan, K., & Anonymous. (2009). Measuring disaster resilience by measuring health. Geological society of America abstracts with programs, 41(7), 374. https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2009AM/webprogram/Paper164780.html ↩

-

Feofilovs, M., & Romagnoli, F. (2017). Measuring community disaster resilience in the Latvian context: An apply case using a composite indicator approach. Energy procedia, 113, 43-50. ↩

-

Mlcek, S., & Ismay, D. (2015). Balanced management in the delivery of community services through information and neighbourhood centres. Third sector review, 21(1), 31-50. ↩

-

Hobfoll, S. E. (2004). Stress, culture, and community: The psychology and philosophy of stress. Springer Science & Business Media. ↩

-

Henkel, K. E., Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2006). Institutional discrimination, individual racism, and Hurricane Katrina. Analyses of social issues and public policy, 6(1), 99-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2006.00106.x ↩

-

Molden, O., Abrams, J., Davis, E. J., & Moseley, C. (2017). Beyond localism: The micropolitics of local legitimacy in a community-based organization. Journal of rural studies, 50, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.01.001 ↩

da Rosa, Christine. (2025). Community-Based Organization Cultural Brokering: A Case Study of the Almeda Fire. (Natural Hazards Center Weather Ready Research Report Series, Report 13). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/community-based-organization-cultural-brokering