Learning From Hurricane Laura’s Near Miss

Evacuation Decision-Making Under Uncertainty

Publication Date: 2022

Executive Summary

Overview

This study took an interdisciplinary approach to explore hurricane evacuation under conditions of compounding climatic and social uncertainty. Some storms have particularly uncertain forecast tracks, making predictions and subsequent protective behaviors, such as evacuation, difficult. Hurricane Laura presented such uncertainty to Houston-Galveston residents in August 2020: although it made landfall northeast of the Houston-Galveston area, local authorities issued evacuation orders for many of the most vulnerable coastal Houston-Galveston communities. There were social concerns, however, about the safety of evacuation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the political climate throughout the COVID-19 pandemic led to doubt in messages from scientists, government authorities, and experts. These conditions provided a unique context to answer the question How do we effectively communicate extreme weather events under conditions of high uncertainty?

Research Questions

- How did the uncertainty of Hurricane Laura as a near-miss event affect evacuation intentions for future storms? How do these prospective evacuation intentions vary based on whether Houston-Galveston residents viewed Laura as a “disaster that almost happened” (vulnerable near-miss framing) or a “disaster averted” (resilient near-miss framing)?

- For communication about a hypothetical future storm, how do variations in risk messengers (who provides the storm information?) and messaging (what information is provided?) affect prospective evacuation intentions? Do any of these variations in messenger or messaging offset the effects of near-miss framings or distrust of official advisories?

- How did the political tensions from the 2020 election and the Covid-19 pandemic affect evacuation behavior?

- What role does trust in science play in evacuation behavior as well as the selection of information sources to inform evacuation decisions? Does distrust of science in the context of a politicized scientific issue (i.e., COVID-19) spill over to scientific issues, more broadly (i.e., hazard warnings)?

Research Design

An online survey of 850 residents of the Houston-Galveston metro region was administered to a panel recruited through the Qualtrics platform. Survey themes for variables of interest included: (a) evacuation behavior (for Hurricane Laura and intentions for future storms); (b) near-miss framing; (c) subjective measures of storm uncertainty and likely impacts; (d) information sources, broadly and specific to evacuation; (e) hazard risk perceptions; (f) science perceptions; (g) political identity and worldviews; and (h) demographics and control variables. To evaluate the effects of near-miss framing on future evacuation intentions, participants’ framing of Laura were assessed and their likelihood of evacuating for a similar future storm was measured. The effects of future hurricane scenarios was considered by randomly assigning participants to control and treatment groups that were shown vignettes that varied in their messengers and descriptions of future storms’ threat and then repeating the measure of evacuation intentions.

Findings

Framing of Hurricane Laura as a vulnerable near miss was associated with higher evacuation intentions for a future storm described as being very similar to Hurricane Laura; however, this effect was fully mediated by risk perceptions for Hurricane Laura. Risk messages highlighting heightened vulnerability to this future storm significantly increased evacuation intentions while messages highlighting the storm’s uncertainty decreased them. COVID-19 concerns did not directly affect evacuation behavior but were instead fully mediated by risk perceptions for Hurricane Laura. There was no significant difference in evacuation behavior for Hurricane Laura between liberal and conservative respondents, although politically unaffiliated respondents appeared to have a lower probability of evacuating. Trust in science showed significant and moderately strong correlations with reliance on evacuation information from local authorities and the media as well as concern about COVID-19.

Practical Implications

The results have several implications for emergency managers and other hurricane risk communicators. First, our real-world results are consistent with prior near-miss research. Risk communicators should therefore be confident in applying lessons from the near-miss literature in the field. In particular, both our results and existing literature suggest that to increase evacuation intentions, risk communicators should attempt to frame a hurricane near miss as vulnerable rather than resilient—i.e., in a way that emphasizes how the near miss was almost a disaster. Second, risk communicators should acknowledge concerns about compounding hazards (i.e., hurricanes and COVID-19) in their messaging. Although concern about COVID-19 did not affect evacuation behavior in our regression modeling, such concern was more prevalent among respondents who evacuated, suggesting a need for messaging that eases the possible burden on mental health associated with simultaneous concern for multiple hazards (e.g., by emphasizing the availability of socially-distanced evacuation options). Finally, risk communicators should consider how trust in science and political beliefs may affect receptivity to their messages and willingness to engage in preparedness and mitigation behaviors. Our results highlight the need for more research on the multiple, complex relationships among these variables and hurricane evacuation and information seeking.

Introduction

While evacuation behavior has been extensively studied (Huang et al., 20161), there remains space for new insights into evacuation decision-making under the context of uncertainty. Among the thirty named storms that occurred in 2020, uncertainty regarding the forecasted track of Hurricane Laura was particularly high. For residents facing decisions regarding whether to evacuate, the variability of Laura’s forecasted track may have been compounded by social uncertainties. Chief among these were concerns regarding the safety of evacuating during the COVID-19 pandemic and a political climate that has contributed to loss of trust in messages from scientists, government authorities, and medical experts. This unique context provided an opportunity to study how to effectively communicate extreme weather events under conditions of high uncertainty.

The questions addressed by this project were informed by the experience of coastal residents in the Houston-Galveston metro region during a near-miss event in late August 2020. Although Hurricane Laura ultimately made landfall as a category 4 hurricane 150 kilometers northeast of the Houston-Galveston area, uncertainty regarding the track was unusually high in the days prior to landfall. Computer models suggested a significant risk of landfall west of the forecast track, potentially placing the highly populous and vulnerable Houston-Galveston metro region in the most damaging quadrant of the storm. In response, local authorities issued mandatory evacuation orders for many of the most vulnerable coastal Houston-Galveston communities; voluntary evacuation orders were in force in other coastal areas.

Beliefs regarding likely hurricane intensity, damage, and household vulnerability are key determinants of household evacuation—as is taking note of official guidance and warnings on these aspects of hurricane events. The heightened and compounding uncertainties surrounding Hurricane Laura’s potential impacts on Houston-Galveston, coupled with safety concerns associated with evacuating during the pandemic and potential loss of trust in expert forecasts, may therefore have impacted evacuation behavior in novel ways. Such near-miss events are likely to influence evacuation intentions for future storms, with the direction of this effect varying based on whether the near miss is framed as highlighting resilience or vulnerability (Dillon et al., 20142; Dillon & Tinsley, 20163). The case of Hurricane Laura’s near miss on Houston-Galveston therefore provided an opportunity for a natural experiment addressing whether residents who frame the near miss in different ways show the expected effects on future evacuation intentions, and whether such framing effects are mediated by perceived trust in experts.

Literature Review

It is widely accepted that risk is socially constructed and, therefore, subject to cognitive biases and inaccuracies (Slovic, 19914). Part of the construction of risk involves weighing uncertainty—uncertainty of the likelihood of an event, uncertainty related to the efficacy of actions taken to prepare for or respond to an event, and uncertainty of the magnitude of the consequences of an event (Eiser et al., 20125). Given the complexity of uncertainty, people typically depend on others for information. In hazard events, broadly, and hazard warnings, specifically, the ‘other’ is often science as it “is our best guide to developing factual understanding” (Dietz, 2013, p. 140826). However, people also draw upon their own experience and values in decision-making; yet, few studies have addressed how real-world experiences and political values, including trust in science, affect evacuation decisions. A better understanding of how the experience of an actual near-miss hurricane event and political values inform evacuation behavior is needed.

Determinants of Hurricane Evacuation Behavior and the Role of Near Misses

There is general agreement regarding the determinants of evacuation behavior. In a meta-analysis of 49 hurricane evacuation studies published between 1991 and 2014, Huang et al. (2016) found positive associations between evacuation and awareness of official warnings, observing peers evacuate, mobile home residence, expected personal casualties, expected storm intensity, expected damage, residing in a high-risk area, and environmental cues. These findings are largely in line with those of Baker (19917), whose review of 15 studies published from 1960 to 1990, found that residing in a high-risk area and receipt of evacuation notices to be the strongest predictors of evacuation. Work published from 2014 to present has shown continued support for positive associations between evacuation and previously-identified correlates, including mobile home residence, higher risk perceptions, receipt of evacuation orders, and living in an evacuation zone (Morss et al., 20168; Sadri et al., 20179; Karaye et al., 201910).

There is less agreement regarding how prior hurricane experience affects evacuation behavior. Although many researchers have found associations between hurricane experience and evacuation, the direction of this effect has been debated. Many suggest the directionality is context-dependent (e.g., Baker, 1991; Whitehead et al., 200011; Hasan et al., 201112; Huang et al., 2016), and the near-miss hypothesis, formulated by Dillon & Tinsley (200813), is a leading attempt to explain this. A series of studies using hypothetical vignettes have found that near-miss events decrease the probability that individuals will take protective actions for future hurricanes (Dillon et al., 201114) but that this can be changed by framing (Dillon et al., 2014) and message content (Dillon & Tinsley, 2016). For events that were framed as vulnerable near misses, emphasizing the danger of a disaster that almost happened but luckily did not (vulnerable frame) rather than a disaster that was averted (resilient frame), risk perceptions and protective behavioral intentions were higher. When damage information was made salient, for example by highlighting damages suffered by a close friend, the near miss no longer reduced the likelihood of intended protective actions (Dillon et al., 2014; Dillon & Tinsley, 2016).

Notably, studies of near-miss events have not yet considered how persons who have experienced a real-world near miss might alter their behavioral intentions due to variation in risk messaging for a similar future hazard. This is particularly important for evacuation behavior, as Huang et al. (2016) noted inconsistencies between studies of actual and hypothetical evacuation behavior. In particular, they found differences in the effects of expected storm intensity, expected wind damage, and taking note of official warnings—all aspects of the hazard that may contribute to its framing as a vulnerable or a resilient near-miss event. This strongly suggests that additional research is needed to confirm the consistency of actual and real-world results.

Effects of Uncertainty and Distrust of Science on Evacuation Behavior

Although science may be the best guide for developing a factual understanding, when faced with a conflict of values and scientific information, individuals often chose information that fits with their values—a behavior known as ‘motivated reasoning’ (Taber & Lodge, 200615; Druckman, 201216). This allows individuals to preserve consistency in their existing understanding of the world and is particularly acute for scientific issues that have been politicized (Pielke, 200717). Politicization occurs when political actors emphasize and exaggerate the uncertainty of science in order to confuse the public and erode their confidence in scientific findings and the agencies which use science to develop policy (Bolsen & Druckman, 201518). The shadow of uncertainty that has been cast by conservatives on the scientific consensus about COVID-19 is a clear example of the politicization of science (Halpern, 202019; Hart et al., 202020) and has caused considerable polarization among the American public (Pew Research Center [Pew], 202021).

Political polarization in our country is increasingly characterized by divisions of identity-based, rather than issue-based, political ideology (Mason, 201822). Rather than debates about policy options, politics has become an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ battle between Republicans and Democrats, rooted in social identity—a sense of self in relation to a social group (Tajfel & Turner, 198623). Scientific information, then, is filtered through the lens of political party identity, and like a sports fan, partisans choose loyalty to their home team over rationality and, even, their own issue preferences (Mason, 2018; Pew, 201924). While Republicans and Democrats in the United States have been found to have about the same level of scientific knowledge (Mason, 2018), they are divided in their confidence in scientists. Trust in science has sharply declined in past decades among conservatives (Gauchat, 201225) to the point of wide divides between partisans today: 67% of liberal Democrats in the United States say they have ‘a lot’ of trust in scientists, compared to only 17% of conservative Republicans (Funk et al., 202026).

The effect of political identity and trust in science on hurricane evacuation behavior has not specifically been tested by researchers; however, past studies show that related variables affect evacuation decisions. Studies have shown that when the accuracy of official forecasts or warnings are called into question, evacuation becomes less likely (Lazo et al., 201027; Morss et al., 2016). Research has also found that individualist worldviews are associated with lower hurricane evacuation intentions, beliefs that hurricane forecasts are “overblown,” higher information avoidance, lower information seeking, and stronger beliefs that hurricane information from media and official sources is biased (Morss et al., 2016; Morss et al., 202028). Political commitments may also affect the likelihood of hurricane evacuation. Such an effect was evident for Floridians’ evacuation from Hurricane Irma; following conservative media sources’ claims that official advisories were overblown and fearmongering, residents in precincts won by Trump were significantly less likely to evacuate than those in precincts won by Clinton (Long et al., 202029).

Current studies have not fully examined the role of political identities, mediated by trust in science, on risk perceptions and evacuation behavior. Given the highly politicized nature of scientific issues today, coupled with considerable political polarization, it is important to take into account how political values and identities affect trust in science and how this, in turn, may spill over to evacuation decision-making, ranging from selection of information sources to behavioral intentions.

Research Design

Research Questions

To address these gaps in the literature, this study considered the following research questions:

- How did the uncertainty of Hurricane Laura as a near-miss event affect evacuation intentions for future storms? How do these prospective evacuation intentions vary based on whether Houston-Galveston residents viewed Laura as a “disaster that almost happened” (vulnerable near-miss framing) or a “disaster averted” (resilient near-miss framing)?

- For communication about a hypothetical future storm, how do variations in risk messengers (who provides the storm information?) and messaging (what information is provided?) affect prospective evacuation intentions? Do any of these variations in messenger or messaging offset the effects of near-miss framings or distrust of official advisories?

- How did the political and epidemiological circumstances of 2020 combine with uncertainty regarding Laura’s track to affect evacuation behavior?

- What role does trust in science play in evacuation behavior as well as the selection of information sources to inform evacuation decisions? Does distrust of science in the context of a politicized scientific issue (i.e., COVID-19) spill over to scientific issues, more broadly (i.e., hazard warnings)?

Study Site Description

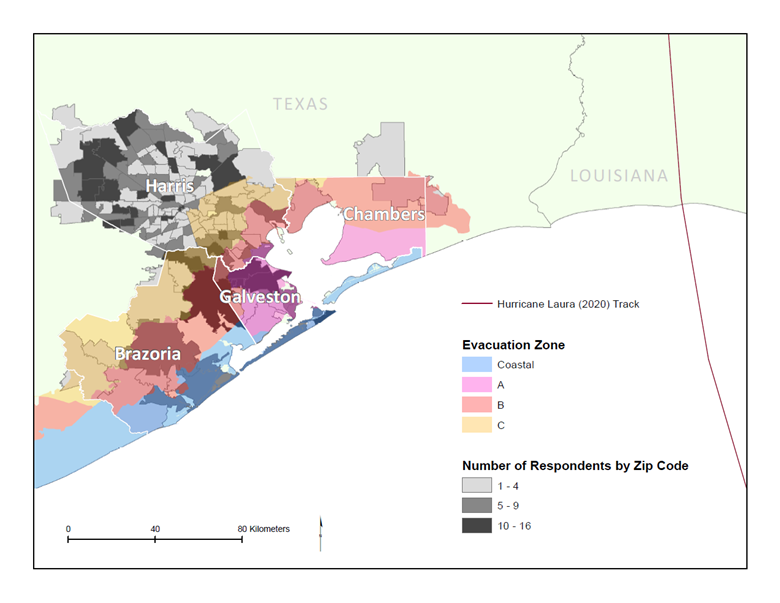

The geographic target of the sample included the four coastal counties in the Houston metropolitan statistical area, including respondents from all four regional evacuation zones (Figure 1). For Hurricane Laura, all “Coastal” zones and some in “A” zones were under mandatory evacuation orders; most other “A” zones were under voluntary evacuation orders.

Figure 1. Study Area Respondents and Evacuation Zones

Data, Methods, and Procedures

The survey was administered online and was hosted on the Qualtrics platform. Survey themes for variables of interest included: (a) evacuation behavior (for Hurricane Laura and intentions for future storms); (b) near-miss framing; (c) subjective measures of storm uncertainty and likely impacts; (c) information sources, broadly and specific to evacuation; (d) hazard risk perceptions; (e) science perceptions; (f) political identity and worldviews; and (g) demographics and control variables (found to be predictive of evacuation behavior, as in Huang et al. (2016) and Baker (1991)). To evaluate the effects of near-miss framing on future evacuation intentions, participants’ framing of Laura were assessed and their likelihood of evacuating for a similar future storm was measured. The effects of future hurricane scenarios were considered by randomly assigning participants to control and treatment groups that were shown vignettes that varied in their messengers (a close friend or a forecaster who works for the National Weather Service) and descriptions of future storms’ threat (probability of causing severe damage or tracking across the metro region) and then repeating the measure of evacuation intentions. Questions regarding near misses, COVID-19, trust in science, individualist worldview, and information sources were replicated from previous studies (i.e., Dillon et al., 2014; Smith & Leiserowitz, 201430; Morss et al., 2020). Zip codes for respondents’ residences were collected to match responses with mandatory and voluntary evacuation zones and identify “shadow evacuees.” (See Appendix A for the full text of survey items and treatment vignettes used in the analyses conducted for this report, along with references to literature supporting their use.)

The respondent pool was recruited by Qualtrics to match a set of demographic quotas taken from the American Community Survey 2018 5-year estimates. Qualtrics drew from a number of panels to recruit participants. Incentives, ranging from discounts and gift cards to entries into sweepstake drawings, were provided by Qualtrics for participation. Consent was collected at the beginning of the survey via an information sheet.

Sampling and Participants

To collect the data needed to explore our research questions, we surveyed a sample of 850 residents in the Houston-Galveston region. The sample size was chosen based on a power analysis for a small to medium-sized effect with ɑ = 0.05 and β = 0.20 (Kane, n.d.31). To be eligible to participate in the survey for this study, respondents were required to be 18 years or older and residents of Harris, Galveston, Brazoria, or Chambers Counties.

Data collection was from March 22 to May 19, 2021. Most of the respondents were residents of Harris County (80%) while 12% came from Galveston County, seven percent from Brazoria County, and one percent from Chambers County. These proportions roughly align with the region’s county-level population density. However, we note that the Galveston County sample proportion, compared to proportion of the county’s population share of the total sample area, was increased from six percent to 12% to capture more respondents from evacuation zones. This was critical given the purpose of the study. Accordingly, the Harris County sample proportion was reduced from 86% to 80% to accommodate for more Galveston County respondents.

This sampling approach succeeded in capturing a substantial percentage of responses from metro region residents under evacuation orders. For mandatory evacuation orders, 9.2% of respondents self-identified as being under such an order while an analysis of zip codes reported for residence location at the time of Hurricane Laura identified 3.6% of residents as being under an order. For voluntary evacuation zones, 21.4% of respondents self-identified as being under such an order while an analysis of zip codes reported for residence location at the time of Hurricane Laura identified 13.6% of residents as being under an order.

The counties targeted for the survey have a population of approximately 5.47 million people, comprised of approximately 40% Latino, 18% African American, and 33% White residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 201932). To sample a representative group of adults in the targeted geographic area, the respondent pool was recruited by Qualtrics to match a set of demographic quotas taken from the American Community Survey 2018 five-year estimates. Qualtrics draws from a number of panels to recruit participants. Incentives, ranging from discounts and gift cards to entries into sweepstake drawings, are provided by Qualtrics for participation.

Quota sampling techniques are found to produce accurate, valid samples of a population because the sample is drawn from a large panel, based on known criteria from the population (Ansolabehere & Schaffner, 201533; Miller et al., 202034). Despite this advantage, the sample drawn was not representative of the population in terms of race and ethnic composition. Specifically, the sample, compared to the population, under-represents Hispanics/Latinos (24.1% versus 40%) and over-represents Whites (45.8% versus 33%). To adjust for this, a survey weight was created using a “raking” or iterative proportional fitting method (Bergmann, 201135). The weight included population parameters on age, gender, and race/ethnicity. While there are no strict rules on trimming survey weights—and many surveys use different trimming procedures and threshold points (Izrael et al., 201136), we adopt the procedure used by others (National Household Travel Survey, 201737) to trim observations three times smaller or three times larger than the median weight value (0.86). No observations fell outside this range; therefore, no weight values were trimmed. The weighted sample, as shown in Table 1, matches population parameters for sex, age, and race/ethnicity.

Table 1. Sample Compared to Population Proportions

| Population Percentage | Unweighted Sample Percentage | Weighted Sample Percentage | ||

| Gender | Male | 49 | 50.1 | 49 |

| Female | 51 | 49.9 | 51 | |

| Age | 18-29 years | 24 | 24.9 | 24 |

| 30-49 years | 39 | 39.3 | 39 | |

| 50-64 years | 23 | 21.9 | 23 | |

| 65 years + | 14 | 13.9 | 14 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 33 | 45.8 | 33 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 40 | 24.1 | 40 | |

| African American | 18 | 19.5 | 18 | |

| Asian and other | 9 | 10.6 | 9 | |

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, regression models, and correlation analyses were used to evaluate the research questions. Pearson correlation tables were calculated to evaluate relationships among trust in science, concern about COVID-19, and evacuation information sources for the fourth research question. Mediation testing was performed as in Baron & Kenny (198638), using the Sobel test (Sobel, 198239). All statistical analyses were performed on a version of the data that had been trimmed using listwise deletion of responses with missing values for study variables: 33 responses were removed due to missingness, leaving 817 valid responses for analysis.

Evacuation decisions for Hurricane Laura were modeled with logistic regression; linear regression was used to model evacuation probabilities for future storms at both pretest and posttest. All regression modeling was performed using the Survey package in R (Lumley, 200440), which accommodates the sample weights developed for our responses. The linear regression models showed some evidence of heteroskedasticity, which was addressed by using robust standard errors. Multicollinearity was evaluated for study variables and found to be acceptable (all variance inflation factor (VIF) values less than 10 and 89% less than five). Regression models for all three dependent variables were run 4-5 times each using a hierarchical approach. The first block entered in the regression included the predictors of greatest interest in this study: near-miss framing and trust in science. (For regressions where posttest probabilities are the dependent variable, this first block also contained a control for pretest values.) The next several blocks added other variables that were either directly related to research questions and/or have been suggested as likely mediators of effects on evacuation behavior for these study variables (i.e., variables for concern about COVID-19, use of science information sources, treatments applied to respondents [only for future evacuation probability dependent variables], risk perceptions, and political beliefs). The final block added other variables that the literature has found to be associated with evacuation behavior or intentions. Model fit was evaluated using R² (linear regressions) and McFadden pseudo-R² (logistic regressions) with values exceeding 0.49 for all full models, indicating good model fit.

Ethical Considerations

This research was determined to meet the criteria for Exemption in accordance with 45 CFR 46.104 by the Institutional Review Board of the Human Research Protection Program of Texas A&M University (IRB ID: IRB2021-0044M).

Findings

The findings are discussed separately for each research question below. (In the appendices, we report the full results from our linear and logistic regression models and cross tabulations.)

Research Question 1: Effects of Near-Miss Framing on Evacuation Behavior and Intentions

Near-miss framing was associated with self-assessed probability of evacuation for future storms at pretest (Appendix B) but not at posttest (Appendix C). Framing of the near miss as more vulnerable was associated with a higher pretest probability of evacuating. This effect was partially mediated by concern about COVID-19 during evacuation (vulnerable near-miss framing was predictive of evacuation probability (β = 6.37, p = 0.007) and COVID-19 concern (β = 0.25, p < 0.001) and the strength of its association with evacuation probability was reduced (β = 4.39, p = 0.06) when controlling for COVID-19 concern (β = 7.82, p < 0.001); a Sobel test was significant (z = 3.85, p < 0.001)). This partial mediation of the near-miss effect by concern about COVID-19 suggests that some portion of the near-miss effect may be driven by general levels of optimism and attitudes towards risk taking (rather than by risk perceptions for a specific hazard), consistent with Dillon & Tinsley (2016). The effect of near-miss framing was also fully mediated by risk perceptions for Hurricane Laura (vulnerable near-miss framing was predictive of Laura risk perceptions (β = 27.11, p = 0.001) and the strength of its association with evacuation probability was greatly reduced (β = 0.78, p = 0.58) when controlling for Laura risk perceptions (β = 0.21, p < 0.001); a Sobel test was significant (z = 5.97, p < 0.001)). This result is consistent with the literature, which has shown that risk perceptions for a hazard often fully mediate near-miss effects on evacuation intentions and other mitigation and preparedness behaviors (Dillon et al., 2014).

Research Question 2: Effects of Risk Messaging on Evacuation Intentions

When controlling for pretest evacuation probabilities, near-miss framing did not significantly affect evacuation probabilities at posttest—either before or after accounting for variations in risk messengers and messaging (Appendix C). Risk messenger (friend or forecaster) and message type (describing track or strength) did not affect self-assessed probability of evacuation for future storms. However, information about the probability of impacts from the hypothetical future storm did have a significant effect, with message formats describing impacts as being twice as likely or twice as damaging resulting in a nearly seven percent higher probability of evacuating (p < 0.001) compared to respondents assigned to the control group (no change in likelihood of direct impacts or expected damage). Additionally, when the expected track or damage potential was described as “highly uncertain,” probability of evacuating decreased by more than 3.5% on average (p < 0.05). These results remained consistent even when controlling for political beliefs and chosen evacuation information sources.

These results suggest that the framing of Hurricane Laura as a vulnerable or resilient near miss did not affect how respondents interpreted the vignettes providing updated risk information for a hypothetical future hurricane. The effects of the vignettes themselves on evacuation intentions were consistent with literature showing that messages highlighting vulnerability (whether via probability or damage potential) can increase intentions to perform mitigation or preparedness actions (Dillon & Tinsley, 2016). Conversely, the message highlighting the hypothetical storm’s uncertainty (whether regarding probability of direct impacts or damage potential) may have activated optimism bias (Sharot, 2011) and an associated tendency to focus on the resiliency against future hurricane impacts (Dillon & Tinsley, 2016).

Research Question 3: Effects of Political Beliefs and COVID-19 Concerns on Evacuation Behavior

Of the entire sample (n = 850), only about 2-in-10 individuals reported evacuating for Hurricane Laura, and one-third expressed that they were “very concerned” about contracting COVID-19 if evacuating. Cross-tabulations reveal that COVID-19 concern was higher among those who evacuated than those who did not: 49% of respondents who evacuated said they were “very concerned” about contracting COVID-19, compared with 31% of those who did not evacuate. Approximately one-third of each group—those who evacuated and those who did not—said they were “somewhat concerned” about contracting COVID-19 if evacuating. Lack of concern, however, was higher among those who did not evacuate: 21% of this group said they were “not very concerned,” compared to 13% of those who did evacuate; and 18% of those who did not evacuate were “not concerned at all,” compared to only five percent of those who did evacuate.

Regarding whether partisan attachments and ideological beliefs were associated with evacuation behavior, descriptive statistics showed that 22% of Republicans, 27% of Democrats, and 14% of Independents/other party evacuated due to the threat of Hurricane Laura (Appendix D). Among those who said they were “extremely liberal,” 44% evacuated. The lowest rate of evacuation was evident among those who say they were “slightly conservative”—only 14% evacuated—while 37% of the “extremely conservative” reported evacuating. (The full results of the cross tabulations for political attachments and evacuation decisions are available in Appendix D.)

Regression results confirmed that higher concern about COVID-19 was associated with a higher probability of evacuating (Appendix E). However, this effect was no longer significant when risk perceptions for Hurricane Laura were entered into the model. Additional analyses confirmed that risk perceptions for Hurricane Laura fully mediated the effect of concern about COVID-19 (COVID-19 concern was predictive of evacuation probability (OR = 1.74, p < 0.001) and Laura risk perceptions (β = 33.60, p < 0.001) and the strength of its association with evacuation probability was greatly reduced (OR = 1.22, p = 0.10) when controlling for Laura risk perceptions (OR = 1.01, p < 0.001); a Sobel test was significant (z = 9.12, p < 0.001)). Regression results also showed that political identification on a spectrum from liberal to conservative did not affect evacuation behavior for Hurricane Laura; nor did egalitarian or individualist worldviews.

These analyses reveal that concerns about COVID-19 were prevalent for individuals who evacuated due to the threat of Hurricane Laura. However, regression and mediation analyses suggest that concerns about COVID-19 did not directly affect evacuation decisions; instead, higher concern about COVID-19 may have been associated with a general tendency towards greater risk awareness, which, in turn, was also associated with higher risk perceptions for Hurricane Laura and a higher probability of evacuating. Our findings also suggest that evacuation behavior is not markedly different among Republicans and Democrats; however, among those who do not affiliate with the two major parties, there is a tendency for lower rates of evacuation. Additional analyses are needed to explore more fully the evacuation behavior of Independents and how being unaffiliated with the major political parties may shape information seeking and evacuation decisions.

Research Question 4: Role of Trust in Science in Evacuation Given Politicized COVID-19 Concern

Turning to the question if trust in science is associated with evacuation behavior, descriptive statistics suggest that confidence in what scientists report is higher among those who evacuated ahead of Hurricane Laura. Thirty-six percent of those who evacuated said they have “a great deal” of confidence in science, compared to 27% among those who did not evacuate. Nearly 59% of those who did not evacuate said they have “a fair amount” of confidence in science, compared to 48% among those who evacuated. Among both groups, nearly 11% said they have “not too much” confidence in what scientists report. Five percent of those who evacuated said they have “no confidence at all” in what scientists report, compared to 3.5% among those who did not evacuate. This indicates that a high degree of confidence in science is evident among those who evacuated; however, even among those who evacuated, science skepticism is present. The majority of individuals who did not evacuate only moderately trust science or show a high degree of skepticism in science.

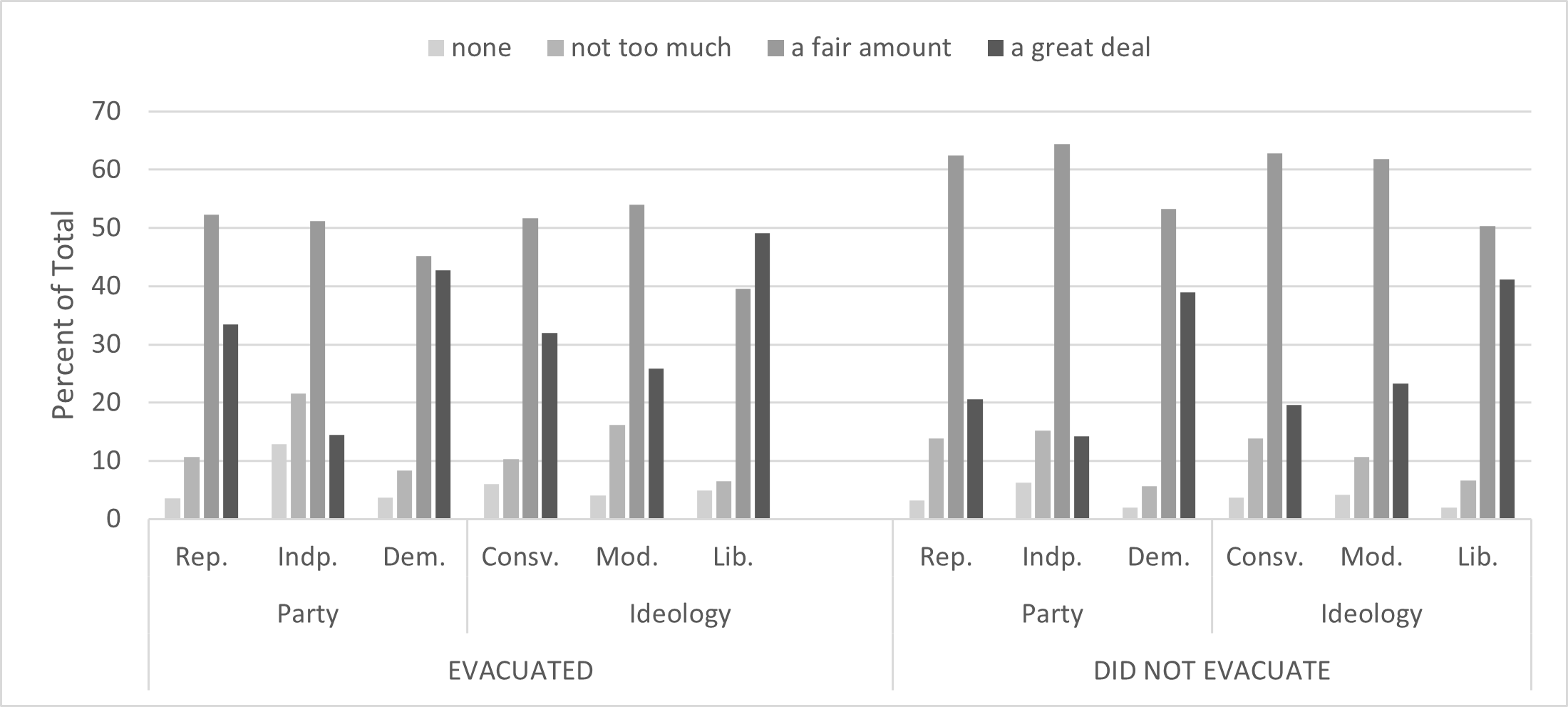

To begin exploring whether trust in science mediates any effects of political beliefs on evacuation behavior, we consider how trust in science varies by party, ideology, and evacuation behavior. Figure 2 shows the prevalence of confidence in what scientists report (none, not too much, a fair amount, a great deal) among those who evacuated and who did not evacuate for each political party subgroup (Republican, Democrat, Independent/other) and aggregated political ideology subgroup (Conservative, Moderate, Liberal). Among those who evacuated in comparison to those who did not evacuate, a great deal of confidence in what scientists report is higher for Republicans and Democrats as well as Conservatives and Liberals but about the same for Independents and Moderates. This points not only to higher rates of trust in science among those who evacuated but also to higher rates of trust among Democrats and Liberals. These findings suggest that political attachments may influence perceptions of science, which may, in turn, shape hurricane evacuation behavior.

Figure 2. Rates of Trust in Science by Political Subgroup and Evacuation Decision

Regression modeling showed that trust in science (scale variable, Table 1) was not a significant predictor of evacuation behavior when entered with only the vulnerable near-miss variable but was associated with a lower probability of evacuating (p < 0.05) when controlling for general trust in others, political beliefs, and risk perceptions for Hurricane Laura. Regression modeling did not support trust in science as a mediator of the effect of political beliefs on evacuation behavior: political beliefs were found to be predictive of trust in science, with more conservative respondents predicted to have less trust (β = -0.12, p = 0.003), but neither political beliefs (on liberal-conservative scale) nor trust in science were found to be significant predictors of evacuation behavior (p > 0.05), whether entered alone or together in regression models.

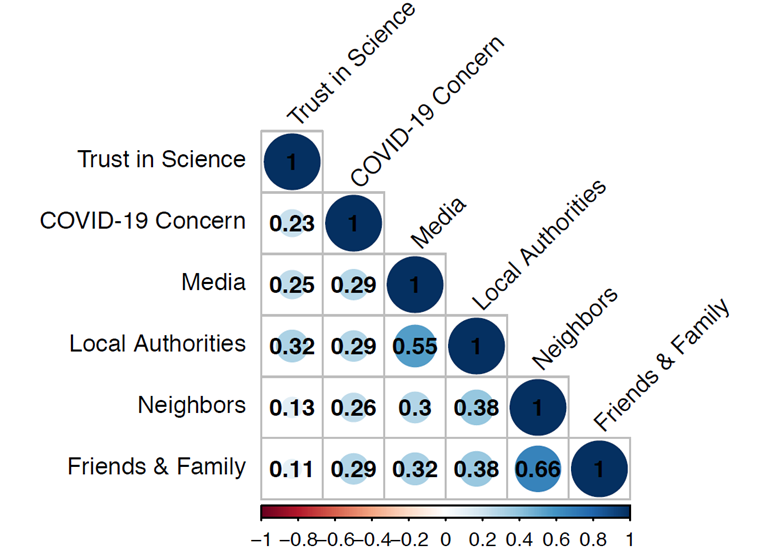

Significant (p < 0.05) positive correlations were found between trust in science and concern about COVID-19 during evacuation and the importance given to information from various sources (media, local authorities, neighbors, and friends and family) during evacuation (Figure 3). The strongest correlations with trust in science were for importance of information from local authorities (p = 0.32) and media (p = 0.25) and for COVID-19 concern (p = 0.23).

Figure 3. Correlation Matrix for Trust in Science, COVID-19 Concern, and Sources of Evacuation Information

These analyses indicate that political beliefs were predictive of trust in science, and showed significant correlations among trust in science, reliance on information from local authorities and the media during evacuation decision-making, and concern about COVID-19. The effect of trust in science and political beliefs on evacuation behavior was less clear, with descriptive statistics suggesting higher rates of trust in science among those who evacuated and identified as Democrats or Liberals while regression analyses suggested that, when controlling for other variables, increased trust in science may instead be associated with lower odds of evacuating (perhaps due to greater trust in official track forecasts for Laura, which accurately predicted that the storm would miss the Houston metro to the east).

Conclusions

These results highlight how risk communication may be particularly challenging in cases where there is uncertainty about the pathway of the threat. Below, we consider the specific implications for practice of our each of our results and associated directions for future research.

Implications for Practice

Focusing on the uncertain risk communication context surrounding Hurricane Laura, this study found that framing the hazard as a near miss was associated with higher evacuation intentions for a future storm of similar threat. Critically, risk messages that highlighted heightened vulnerability (i.e., potential losses) to this future storm significantly increased evacuation intentions. These findings point to a need to emphasize and discuss near-miss events with the public, not as indications of poor climate and weather modeling (which the uninformed may infer) but as possibilities for future threats. Rather than justifying misses as ‘lucky’, communities should promote a dialogue about near misses and the possible damage they could have caused. These recommendations are consistent with those from prior near-miss research, which has shown that preparedness intentions (including for hurricane evacuation) tend to be higher when near-miss framings emphasize vulnerability. Because this study tested the effects of near-miss framing for a directly experienced, real-world near miss (as opposed to prior work, where near misses were generally hypothetical or not directly experienced by the participants), it should increase risk communicators’ confidence in applying lessons from the near-miss literature in the field.

Although concern about COVID-19 did not affect evacuation behavior in our regression modeling, such concern was more prevalent among respondents who evacuated. This suggests a need for messaging that eases the possible burden on mental health associated with simultaneous concern for multiple hazards (e.g., by emphasizing the availability of socially-distanced evacuation options). Risk communicators should therefore consider acknowledging concerns about compounding hazards (i.e., hurricanes and COVID-19) in their messaging.

Finally, risk communicators should consider how trust in science and political beliefs may affect receptivity to their messages and willingness to engage in preparedness and mitigation behaviors. Although there was no significant difference in evacuation behavior for Hurricane Laura between liberal and conservative respondents, politically unaffiliated respondents appeared to have a lower probability of evacuating. Additionally, trust in science showed significant and moderately strong correlations with reliance on evacuation information from local authorities and the media as well as concern about COVID-19. This is suggestive of multiple, complex relationships among these variables and evacuation behavior and information seeking, with more research needed to better understand these results and their practical implications.

Future Research Directions and Next Steps

Building on the analyses presented, next steps include updating regression analyses to consider possible interaction terms (e.g., of risk messages with political beliefs and near-miss framing) and to operationalize political beliefs in different ways to more completely examine their effects on evacuation behavior and their possible mediation by trust in science. Additional analyses are also needed to: 1) explore more fully the evacuation behavior of Independents, especially with regard to understanding how and why they may differ from those affiliated with major political parties in their information seeking and evacuation decisions; and 2) further tease out whether and how trust in science mediates information sources that individuals with different political beliefs seek out when making evacuation decisions. Once study findings have been finalized, they will be shared through research briefs and informal, science café style talks with local stakeholder groups with an interest in disaster preparedness.

References

-

Huang, S.-K., Lindell, M. K., & Prater, C. S. (2016). Who leaves and who stays? A review and statistical meta-analysis of hurricane evacuation studies. Environment and Behavior, 48(8), 991–1029. ↩

-

Dillon, R. L., Tinsley, C. H., & Burns, W. J. (2014). Near-Misses and Future Disaster Preparedness. Risk Analysis, 34(10), 1907–1922.https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12209 ↩

-

Dillon, R. L., & Tinsley, C. H. (2016). Near-miss events, risk messages, and decision making. Environment Systems and Decisions, 36(1), 34–44 ↩

-

Slovic, P. (1991). Beyond Numbers: A Broader Perspective on Risk Perception. Acceptable Evidence: Science and Values in Risk Management, 48. ↩

-

Eiser, J. R., Bostrom, A., Burton, I., Johnston, D. M., McClure, J., Paton, D., Van Der Pligt, J., & White, M. P. (2012). Risk interpretation and action: A conceptual framework for responses to natural hazards. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 1, 5–16. ↩

-

Dietz, T. (2013). Bringing values and deliberation to science communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(Supplement 3), 14081–14087. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212740110 ↩

-

Baker, E. J. (1991). Hurricane evacuation behavior. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 9(2), 287–310. ↩

-

Morss, R. E., Demuth, J. L., Lazo, J. K., Dickinson, K., Lazrus, H., & Morrow, B. H. (2016). Understanding public hurricane evacuation decisions and responses to forecast and warning messages. Weather and Forecasting, 31(2), 395–417. ↩

-

Sadri, A. M., Ukkusuri, S. V., & Gladwin, H. (2017). The role of social networks and information sources on hurricane evacuation decision making. Natural Hazards Review, 18(3), 04017005. ↩

-

Karaye, I. M., Horney, J. A., Retchless, D. P., & Ross, A. D. (2019). Determinants of hurricane evacuation from a large representative sample of the US Gulf Coast. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(21), 4268. ↩

-

Whitehead, J. C., Edwards, B., Van Willigen, M., Maiolo, J. R., Wilson, K., & Smith, K. T. (2000). Heading for higher ground: Factors affecting real and hypothetical hurricane evacuation behavior. Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards, 2(4), 133–142. ↩

-

Hasan, S., Ukkusuri, S., Gladwin, H., & Murray-Tuite, P. (2011). Behavioral model to understand household-level hurricane evacuation decision making. Journal of Transportation Engineering, 137(5), 341–348. ↩

-

Dillon, R. L., & Tinsley, C. H. (2008). How near-misses influence decision making under risk: A missed opportunity for learning. Management Science, 54(8), 1425–1440. ↩

-

Dillon, R. L., Tinsley, C. H., & Cronin, M. (2011). Why Near-Miss Events Can Decrease an Individual’s Protective Response to Hurricanes. Risk Analysis, 31(3), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01506.x ↩

-

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x ↩

-

Druckman, J. N. (2012). The Politics of Motivation. Critical Review, 24(2), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2012.711022 ↩

-

Pielke Jr, R. A. (2007). The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics. Cambridge University Press. ↩

-

Bolsen, T., & Druckman, J. N. (2015). Counteracting the politicization of science. Journal of Communication, 65(5), 745–769. ↩

-

Halpern, 2020: Halpern, L. W. (2020). The Politicization of COVID-19. The American Journal of Nursing 120(11), 19-20. ↩

-

Hart, P. S., Chinn, S., & Soroka, S. (2020). Politicization and Polarization in COVID-19 News Coverage. Science Communication, 42(5), 679–697. ↩

-

Pew Research Center (2020). Republicans, democrats move even further apart in coronavirus concerns. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/06/25/republicans-democrats-move-even-further-apart-in-coronavirus-concerns/ ↩

-

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/U/bo27527354.html ↩

-

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 7–24. ↩

-

Pew Research Center (2019). Partisan antipathy: More intense, more personal. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/10/10/partisan-antipathy-more-intense-more-personal/ ↩

-

Gauchat, G. (2012). Politicization of science in the public sphere: A study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. American Sociological Review, 77(2), 167–187. ↩

-

Funk,. C, Tyson, A., Kennedy, B., & Johnson, C. (2020). Science and Scientists Held in High Esteem Across Global Publics. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/29/science-and-scientists-held-in-high-esteem-across-global-publics/ ↩

-

Lazo, J. K., Waldman, D. M., Morrow, B. H., & Thacher, J. A. (2010). Household evacuation decision making and the benefits of improved hurricane forecasting: Developing a framework for assessment. Weather and Forecasting, 25(1), 207–219. ↩

-

Morss, R. E., Lazrus, H., Bostrom, A., & Demuth, J. L. (2020). The influence of cultural worldviews on people’s responses to hurricane risks and threat information. Journal of Risk Research, 1–30. ↩

-

Long, E. F., Chen, M. K., & Rohla, R. (2020). Political storms: Emergent partisan skepticism of hurricane risks. Science Advances, 6(37), eabb7906. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb7906 ↩

-

Smith, N., & Leiserowitz, A. (2014). The Role of Emotion in Global Warming Policy Support and Opposition. Risk Analysis, 34(5), 937–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12140 ↩

-

Kane, S. (n.d.). Sample Size Calculator. ClinCalc. Retrieved July 24, 2019, from https://clincalc.com/stats/samplesize.aspx ↩

-

United States Census Bureau (2019). QuickFacts United States [Data set]. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/ ↩

-

Ansolabehere, S., & Schaffner, B. F. (2015). Does survey mode still matter? Findings from a 2010 multi-mode comparison. Political Analysis, 285–303. ↩

-

Miller, C. A., Guidry, J. P., Dahman, B., & Thomson, M. D. (2020). A tale of two diverse Qualtrics samples: Information for online survey researchers. Cancer, Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 29(4): 731–735. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0846 ↩

-

Bergmann, M. (2011). IPFWEIGHT: Stata Module to Create Adjustment Weights for Surveys. Statistical Software Components S457353. Department of Economics: Boston College. ↩

-

Izrael, D., Battaglia, M.P., & Frankel, M.R. (2011). Extreme survey weight adjustment as a component of sample balancing (aka raking). Proceedings from the Thirty-Fourth Annual SAS Users Group International Conference. 247-2009. http://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings09/247-2009.pdf ↩

-

National Household Travel Survey (2017). Weighting Report. https://nhts.ornl.gov/assets/2017%20NHTS%20Weighting%20Report.pdf ↩

-

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. ↩

-

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. ↩

-

Lumley, T. (2004). Analysis of complex survey samples. Journal of Statistical Software, 9(1), 1–19. ↩

Retchless, D., & Ross, A. (2022). Learning From Hurricane Laura’s Near Miss: Evacuation Decision-Making Under Uncertainty (Natural Hazards Center Weather Ready Research Report Series, Report 4). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/learning-from-hurricane-lauras-near-miss-evacuation-decision-making-under-uncertainty