Local Voices of Maui

Critical Visual Reflections From the 2023 Maui Fires

Publication Date: 2025

Abstract

The period following the 2023 Maui fires included an intense public debate about recovery efforts and whether members of the impacted community were being incorporated into recovery planning and programs. While some governing agencies made efforts to include community perspectives in their initiatives, many Maui residents remain concerned about the direction of the recovery. To understand their views, we utilized an adapted photo elicitation method—which combines researcher-taken photographs with interviews and social media data—to answer two primary research questions: (a) How do residents view the organizational recovery efforts to build back Maui? (b) What opportunities and challenges do residents see in the recovery process? Guided by these questions, we conducted site visits in May and August 2024, a period which coincided with the disillusionment phase of the disaster recovery process. We took 23 photos, conducted 31 interviews with representatives of local nonprofits, grassroots organizations, and community members, and collected 381 social media posts that highlight community perspectives regarding the recovery process in Maui. Our analysis of the data revealed residents perceived four major challenges during the recovery, which we categorized as: (a) respecting our grief, (b) focusing on families first, (c) distrust of government aid, and (d) inflated housing prices. The data also showed that residents saw three opportunities emerging, which we categorized as: (a) restoring the water, (b) building on community resilience, and (c) planning for the next disaster. Based on these results, we recommend continued efforts to build trust with local communities by working with trusted leaders and organizations. We also recommend that decision-makers consider affordable housing policies to prevent displacement, evacuation route planning to prevent future hazard tragedies, and recovery planning that considers cultural and place-based priorities like honoring burial sites and restoring the water.

Introduction

In August 2023, wildfires razed the city of Lahaina and the Upcountry/Kula areas on the island of Maui, leading to one of the “deadliest fire[s] in modern American history” (Maui Police Department, 2024, p. 91). The event also instigated an uproar about the emergency preparedness and response failures that contributed to the high death toll as well as the direction of recovery efforts. Communication (or lack thereof) among governing agencies, nonprofit responders, grassroots providers, and the community plays a large role in ensuring recovery efforts are reflective of community needs and effective in supporting survivors after a disaster. However, survivors of the Maui wildfires struggled to have their voices heard by authorities and their views incorporated into recovery measures (Ing, 20232). The discontent among community members could be a warning sign that recovery efforts are ineffective recovery or survivor needs are being neglected.

Scholars have consistently highlighted the importance of community involvement in disaster recovery processes (Onstad et al., 20173; Morello-Frosch et al., 20114). When community voices are overshadowed by other interests, recovery is uneven (Duval-Diop et al., 20105; Gotham & Greenberg, 20146). Moreover, as disasters have increased in frequency and intensity, the number of disaster survivors needing recovery services have multiplied. Many jurisdictions have turned to nonprofits to undertake community engagement efforts and fill unmet community needs (Kapucu et al., 20187; Mathias et al., 20228). The involvement of nonprofits in recovery efforts highlights the potential for collaboration, but it also reveals a challenging recovery environment where funding prioritizes immediate, visible actions over addressing long-term and often unforeseen consequences (Winkworth, 20079).This study explores these issues in the context of the 2023 Maui fires by asking community members, grassroots organizations, and nonprofit leaders about their perceptions of the recovery process using visual reflections and narrative interview data.

Literature Review

Research on wildfire risks in Hawaiʻi has a history going back decades (Ka’anapu, 202310). Many studies have focused on key risk factors, such as the susceptibility of the island to fires, which is exacerbated by nonnative vegetation (grasslands and shrublands); densely-populated areas near the shore with unpermitted accessory dwelling units for large Hawaiian families, increasing the number of people impacted and hindering already stressed roads for any evacuation; and a dry, tropical ecosystem that has been degraded by climate change and urban development (Ainsworth & Drake, 202411; Bremer et al., 201812; Tran et al., 202413; Trauernicht et al., 201514). However, studies examining how wildfire survivors recover in Hawaiʻi are limited; more research is needed to understand the long-term recovery outcomes of those Hawaiians who lose the most. Furthermore, community health impacts, the cascading effects of recovery decision-making, and investigations into how residents are informed about and involved in recovery are understudied topics within the body of wildfire recovery research (Finlay et al., 201215; Steelman et al., 201516; Zheng, 202317).

Disasters and Long-Term Recovery

Prior research has explored wildfire recovery among impacted communities across the United States (Kooistra et al., 201818; Kulig & Botey, 201619; Miller & Mach, 202120; Moloney et al., 202321). These studies highlight the importance of focusing on wildfire recovery efforts because “there remains little research specific to wildfire recovery…[and] the emotional highs and lows experienced by people after the disaster” (McGee et al., 2020, pp. 175-17622). In their study examining wildfire recovery, McGee and colleagues (2020) found that emotional highs occur immediately following the hazard when community cohesion is at its highest. As the community moves from response to recovery, however, survivors tend to experience sharp emotional lows in what they and other scholars have labeled the disillusionment phase, which usually coincides with one-year anniversary reactions. Similarly, Ryan and Hamin’s (200823) post-wildfire study found that it is critical to address community members’ emotions and perceptions during the wildfire recovery processes. For example, survivors frequently want access to their homes, even if they have been destroyed, because this gives them a sense of agency regarding their community’s recovery decisions. Overall, previous studies on wildfire recovery highlight the importance of not only considering these emotionally vulnerable moments but also capturing residents’ perspectives during these moments as they can inform the reconstruction process.

Visual Data Analysis for Disasters

While visual methods have been used to study various disaster contexts, photo elicitation is a less utilized approach. For example, visual cultures research has been used to study earthquakes (Weisenfeld, 201224), COVID-19 (Callender et al., 202025), and terrorist attacks (Stubblefield, 201426). However, these studies used pre-existing cultural documents (i.e., famous photos, newspaper pictures) which do not necessarily capture the reality of those impacted by a disaster. Visual methods that combine community-relevant photos with participant narratives can draw out conscious and unconscious emotions (Lorenz & Kolb, 200927) and elicit culturally shared realities (Rose, 201428)—both of which are important in the study of disasters as communities are constantly in the state of reconstructing their own lives and realities (Kelly et al., 201929). This study harnessed the strength of community-driven visual data analysis by combining an adaptive photo elicitation method (i.e., photos and semi-structured interviews) and social media data. By focusing on community perspectives during the disillusionment phase of the 2023 Maui fires recovery, this study addresses gaps in knowledge related to community emotions and reactions to long-term recovery efforts.

Research Questions

This study was guided by the following research questions:

- How do residents view the organizational recovery efforts to build back Maui?

- What opportunities and challenges do residents see in the recovery process?

Research Design

We collected qualitative data on the long-term recovery perspectives of Maui residents following the 2023 fires. We selected an adapted photo elicitation method which included semi-structured interviews (Harper, 200230) and an analysis of social media data because it allowed us to uncover complex experiences and opinions that can be difficult to communicate verbally. The photo elicitation method guided our conversations with participants and captured difficult-to-communicate emotions (Harper, 2002). In total, we took 23 photos, conducted 31 interviews, and analyzed 381 social media posts. The latter supported the interviews and visual data by adding more community conversations and diverse perspectives.

Study Site and Access

There is widespread distrust of the federal government among Hawaiians, which derives in part from the islands’ history of colonization, which many consider part of Hawai‘i’s unique culture (Vogeler, 201431). Because distrust in government officials is sometimes attributed to their lack of presence in the community, we felt it was crucial for us to conduct in-person interviews and fieldwork. In-person interviews also allowed us to create a more comfortable setting than virtual interviews and build stronger rapport with interviewees. Additionally, being at the research site allowed us to observe how community members interact with one another, which would not have been possible through online conversations. We traveled across the island to meet interviewees in locations convenient to them, including Kaʻanapali, Lahaina, Kihei, Wailuku, and Kula. These locales ranged from easily accessible urban areas to rural areas with limited road infrastructure. During our fieldwork, we observed visual reminders of support (e.g., Lahaina Strong stickers, street art, public messages of support) in unexpected places, which we recorded using our adapted photo elicitation method. In total, we conducted two site visits to Maui in May and August 2024.

Interviews and Photos Using the Adapted Photo Elicitation Method

Guided by photo elicitation (Harper, 2002) and Photovoice (Wang & Burris, 199732), we initially planned to collect visual reflections through a photographic survey and host group discussions. However, after consulting with local experts and considering the appropriateness of our methods, we shifted to an adapted photo elicitation technique that included interviews (Harper, 2002). This method combines in-depth interviews with meaningful visuals to elicit deep reflections (Harper, 2002). Although photo elicitation typically includes photos taken before the interview to elicit more information from the participant, we included research-taken photos at the end of the interview, guided by the themes of the interview. This change allowed both the researchers and participants to actively reflect on the stories that were told in the interview by grounding the photographs within the themes that were most important to the participant. This also allowed participants an opportunity to correct any interpretations that weren’t grounded in their story. By focusing on visual recovery objects or places discussed during interviews, we aimed to bridge cultural meanings and foster participant self-reflection.

Sampling Strategy

We targeted two groups to participate in interviews: (a) representatives of organizations (nonprofit, grassroots, and government) that were active in the recovery efforts and (b) community members in the research sites who displayed some visual depiction of recovery or resilience. We wanted to interview organizational representatives to learn about their experiences as the frontline responders. We chose to interview community members to learn about personal experiences, oftentimes as community responders and recipients of those services. We used three sampling strategies to select interviewees. First, we developed a targeted purposive sample of nonprofit and grassroots organizations who were centrally involved in the wildfire recovery effort. We determined centrality by creating a network of nonprofit organizations (N = 68) that were involved in fundraising, resource allocation, or donation support in the months following the fires through newspaper articles. We created a matrix that coded “relationships” between those organizations that were listed in an article with similar purposes. Those organizations that had more relationships with other organizations had higher degrees of centrality, that is, more connectivity to other organizations. From there, we reached out to the 15 organizations with the highest degree of centrality in the network. We contacted organizations via email or through social media to request in-person interviews. Two interviews took place over Zoom per the organization’s request. This strategy yielded 13 interviews with 22 participants. Another purposive sampling strategy was a targeted reach to the State Emergency Management Agency, which led to one interview with two community outreach employees, both Native Hawaiian.

Second, we used a convenience and snowball sample to capture the perspectives of community members, faith leaders, and homeowner groups. Our first strategy to capture these perspectives was to walk around public areas in the impacted area (e.g., parks, grocery stores, parking lots) and attend public meetings about the recovery efforts. We approached individuals in these spaces who had visual displays of recovery (e.g., cars with Lahaina Strong written on them, t-shirts, stickers, pins, etc.). This resulted in three interviews with four participants. In our second strategy, we used a snowball sample and asked participants to introduce us to others within the community that had perspectives on the recovery process. This strategy yielded four interviews with six participants. In total, our sampling strategy resulted in 20 interviews with 32 people.

Participant Recruitment and Consent

All interviews took place between May and August of 2024. At the outset of the interview, we explained the purpose of the study and read a verbal consent script to the interviewees which informed them of their rights and asked for their consent to participate. We also provided the interviewees with study flyers and our contact information. During interviews, we took notes on visual imagery mentioned by the interviewees. At the end of the interview, we explained the photo elicitation component of the study and asked the following question:

As part of this project, we are collecting visual images of resilience to include in a living gallery. We hope to display these images in university galleries across the world to raise awareness. Do you have an image of resilience that you would like to share? (People have shared pictures of their cats or their garden growing.)

After their consent, we asked interviewees to describe the meaning of relevant objects or places and asked permission to photograph these objects, ensuring images were edited to remove identifying information. Participation in the photo elicitation component was voluntary and not required to participate in the interview. Appendix A provides the interview guide for the nonprofit and grassroots leaders and Appendix B provides the interview guide for community members.

Interview and Photograph Samples

The interview sample included 32 participants across 20 interviews. Table 1 provides an overview of the interview sample. The majority of the interviewees were women (69%) and most were between 20 and 40 years of age (50%). Fifteen participants (47%) identified as White or Caucasian, 13 (41%) identified as having some Native Hawaiian heritage, three identified as Asian, and one participant did not discuss their heritage.

Table 1. Select Characteristics of the Interview Sample

| Gender | Women | ||

| Men | |||

| Race or Ethnicity | White | ||

| Native Hawaiian | |||

| Asian American | |||

| Mixed | |||

| Not Provided | |||

| Occupation | Nonprofit or Grassroot Leaders | ||

| Nonprofit Employee | |||

| Religious Leader | |||

| Government Agency Employee | |||

| Lahaina Residents | |||

| Age | 20-40 | ||

| 41-60 | |||

| 61+ | |||

The photographic sample included 23 photos. We took all photos in the field as guided by the elicitation interview. Table 2 includes the number of photos segmented by theme.

Table 2. Visual Data Themes

| Challenges in Recovery | |

| Respecting Our Grief | |

| Focusing on Families First | |

| Distrust of Government Aid | |

| Inflated Housing Prices | |

| Opportunities in Recovery | |

| Restoring the Water | |

| Building on Community Resilience | |

| Planning for the Next Disaster | |

| Total Number of Photos |

Reflexive Approach and Data Analysis Procedures

We used a reflexive approach (Jenkings et al., 200833) during and after the elicitation interviews to analyze the visual and interview data. We began with a set of interview questions informed by after action reports and a priori literature on community and nonprofit recovery efforts. Although many reflexive approaches include participant-taken photos, we chose an alternative approach in which we actively reflected on the visual themes during the interview and then presented these themes to participants at the end for their feedback. This elicited a collaborative analysis between the researcher—who is actively summarizing themes and connecting them to a priori research in real time—and the participant—who is verifying or correcting researcher interpretations, suggesting alternative visual representations, and providing analytical categorizations through title and description suggestions (Jenkings et al., 2008).

As is common practice in photo elicitation studies (e.g., Noland, 200634), we used participant quotes and descriptions of photos as the basis for analytic themes. These themes are considered “locally co-constructed” categories that should be applied to other photos and interviews (Jenkings et al., 2008, p. 14). This reflexive process produced two main themes and eight sub-themes (see Table 1). To ensure accuracy of these co-created themes, we uploaded all photos to a website where participants could view the photos alongside the themes, and descriptions we had developed. The website also allowed participants to provide edits or clarifications. The website information was shared with all participants during the interviews through the flyer that had the relevant information about the study. They were encouraged to check the website for the images uploaded, and to reach out by email or phone to provide their feedback. To date, one participant has provided edits for their photo’s themes and description.

After this initial analysis, we uploaded the interview data into Dedoose (9.2.22) for further qualitative analysis. This software allows researchers to code interview data, with the simultaneous ability for multiple researchers to work on the same file and view the work.

Social Media Data

It was evident at the beginning of our first visit that residents were research-fatigued with calls for surveys and interviews from various sources. This meant our original plan to utilize a survey collection method for photo elicitation, along with focus groups to discuss images further, was not successful. We pivoted to a more personal approach. These changes to our data collection and sampling strategies allowed us to collect reflexive visual and interview data. However, we felt that omitting focus groups impacted our ability to capture community conversations around recovery issues. Without these conversations, we felt that our study would exclude hard-to-reach populations that should be heard when making critical decisions within the recovery process. To account for this limitation, we added a social media data analysis component.

Sampling Strategy

We collected social media posts from Instagram, Facebook and TikTok. These platforms were chosen because they incorporate visual components as a primary way to communicate messages to the public, which aligns with the overall purpose of this research project. Data collection occurred between June 27, 2024, and August 28, 2024. The process of collecting data included first searching for hashtags or keywords related to the 2023 Maui fires (#Lahainastrong, #Kulastrong, #Upcountrystrong, #Mauistrong, #Mauifire, #Lahainafire, #Kulafire) to identify relevant social media posts created between August 7, 2023, and August 11, 2024. We reviewed each post to see if the account holder lived in Maui or if the post had comments from anyone who lived in Maui. We then took a screenshot of the post’s content and associated comments, focusing on perspectives of those who lived in Maui. The screenshots were uploaded to a secure Google Drive, where a research assistant local to the area coded segments of the picture based on analytical themes. Finally, we met with the research assistant weekly to discuss the codes and resolve any discrepancies.

We collected 413 cases from social media. When a post included multiple pictures, lengthy descriptions, and/or active discussions within the comments, we used multiple screenshots to capture the overall context to understand the nuances within community conversations surrounding recovery. Thus, cases may have included different elements of the same social media post. Table 3 includes the number of codes by social media type and by theme.

Table 3. Themes of Social Media Data

| Challenges | ||||

| Tourism and the Economy | ||||

| Slow Rebuilding Process | ||||

| Outside Influence | ||||

| Criticism of Government | ||||

| Aid from Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and Red Cross | ||||

| Addressing the Housing Crisis | ||||

| Opportunities | ||||

| Restoring the Environment | ||||

| Community Response Efforts | ||||

| Building Resilience | ||||

| How Others Can Help Maui | ||||

| Total Number of Cases | ||||

Data Analysis Procedures

We used a deductive approach to analyze social media data. Guided by the initial themes from the photo elicitation component and unanswered questions within our interviews, we established a preliminary coding scheme, as outlined in Table 1. Throughout the coding process, we adjusted, merged, and split themes within weekly coding meetings. An example of this was the criticisms of government code and the aid from Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Red Cross code, which was originally one code capturing all recovery aid. After discussions with our research assistant and others on the team, we segmented this code to capture specific opinions related to aid versus criticisms of government processes, responses, and actions. After the data was coded by a research assistant, we uploaded the pictures to NVivo 12 and one lead researcher verified themes.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

This project was given an exempt determination by the University of South Florida on March 26, 2024, and by Florida Atlantic University on April 23, 2024. An amendment was acknowledged by Florida Atlantic University on May 8, 2024, to include social media and researcher observations, including the use of researcher-taken photos.

Throughout the lifecycle of this research project, we reflected on our positionality and the impact that our research would have on the interviews, including the historical impacts of colonialism and researcher responsibility to amplify Native Hawaiian voices (Barnard, 200635; Hall, 200836; Silva, 200437). Before entering the field, we consulted six local experts with ties to the Maui community. We learned that we would be considered “outsiders” and had to be invited to access certain populations. Although we could not secure a local partner in time, we hired a student from the University of Hawaiʻi as a local facilitator. However, due to geographical and cultural challenges, her role was adjusted to social media analysis.

We also actively reflected on our positionality in the field. We heard stories of other researchers using residents to gain access to sensitive information, which caused distrust between residents and the academic community. We addressed these challenges by entering into each interview transparently about our project and data collection methods. We tried to provide participants with the time and space to talk, embracing the Hawaiian concept of “talk story” (P, Lahaina Resident and Master carpenter). Talk story refers to the “casual exchange of narrative with a sense of mutuality…a method of sharing the incidentals that shape daily existence” (Simpson Steele, 2012, p. 3938). In the context of this research, it was the notion of connecting with residents and their stories with the time that they chose to provide us with. Interviews were approached with one goal: to learn from their stories. One participant appreciated our approach, noting, “just being aware is a huge thing.”

Regarding reciprocity, we emphasized how we planned to share our data and asked participants what action items or takeaways they desired. This approach allowed them to express their hopes for the research, often highlighting the need for ongoing global support and considerate tourism. We avoided solicitation of participants by posting flyers in public spaces following guidance from local experts, and incorporated a more personal approach—honoring conversations, learning from stories, and showing gratitude to participants.

Findings

Challenges in the Recovery Process

Our analysis of the data revealed that interviewees perceived four main challenges in recovery, which we categorized as: (a) respecting our grief, (b) focusing on families first, (c) distrust of government aid, and (d) inflated housing prices.

Respecting Our Grief

Figure 1 is a visual example of the theme respecting our grief. This particular one is called “E Komo Mai,” for “welcome” in Hawaiian. Handwritten signs, like Figure 1, are found across Maui and reflect residents’ concerns about tourists not being respectful of the losses that Maui experienced, a topic which was discussed by six interview participants. Two interviewees, for example, mentioned that the burn zone needed to be respected as a burial site. A nonprofit manager expressed, “We will never go in there [the ocean in Lahaina] again. I feel as long as that’s respected, that is understood, that that’s what that is, it can be whatever they want.” Our analysis of social media data, which we coded with the theme tourism and the economy, showed growing tensions between tourists and residents, with some highlighting the need for space from tourists to grieve; others called attention to insensitivity to their loss. This included not only their loved ones and homes, but also their history.

Figure 1. Image Depicting the Theme Respecting Our Grief

Focusing on Families First

Figure 2 is a visual example of the theme focusing on families first and was taken after an interview with a self-employed contractor and resident of Maui for 20 years. The interviewee emphasized that families and small businesses were the ones suffering within the recovery process due to slow rebuilding and loss of jobs. The image shows his truck, which he called “Fiametta,” meaning “little fiery one in Italian.” He said he painted it to bring visibility and attention to the cause of aiding Hawaiian families. He also retrofitted the truck so he could sleep in it (thus reducing the burden of shelter from those displaced residents he felt needed it more), and work as constantly as possible to help the community rebuild. As he said,

I am already helping to rebuild this town…I only care about redoing business and homes. I won’t rest until every square block is rebuilt. I built up my truck so that I can put my tent on the back. And that’s how I can [help].

The interviewee’s primary goal and message, as indicated on his truck, was “Donate to Maui families!!!”, highlighting the idea of focusing on families first. In the social media data, the themes of slow rebuilding process and outside influence highlighted growing concerns that long-time residents would not be able to stay on the island. Specifically, there were reports on social media that investors were trying to purchase family-owned land in the immediate aftermath of the fires.

Figure 2. Image Depicting the Theme Focusing on Families First

Distrust of Government Aid

Figure 3 is a visual example of the theme distrust of government aid taken following an interview with a church pastor in Lahaina outside of the burn zone. The image depicts remnants of a time when FEMA was present in that park, the chalk markings serving as a reminder of how FEMA representatives took up space in the local community. In this interview, she described a strong distrust between residents and federal government aid organizations, specifically FEMA: “But some people were very much against the FEMA people, when they first came here…the local people only wanted to deal with their own coalition of people.” Seven other interviewees described community distrust of FEMA, some of which was fed by underlying historical distrust. Others expressed feelings that FEMA was trying to stop community-led recovery efforts instead of working with them. In the social media data, the themes criticisms of government and aid from FEMA and Red Cross highlighted some initial reassurance in FEMA’s presence immediately following the fires, which was quickly replaced with reports of frustration with red tape in accessing benefits and “turf wars” with local community organizations.

Figure 3. Image Depicting the Theme Distrust of Federal Government Aid

Our data showed residents were upset with the high cost of FEMA’s direct lease program, which the agency implemented to address the displacement of survivors from their homes by the fire. As part of the program, FEMA encouraged property owners to lease their existing residential properties to displaced families for 12 to 24 months (FEMA, 202339). FEMA promised property owners who agreed to participate in the program that it would honor their existing property policies and pay for property maintenance and contractual services. Three interviewees mentioned the cost of FEMA direct lease rentals—with one mentioning that these could be upwards of $10,000 per month—as responsible for driving up rental prices across the island and causing secondary displacement of renters. As one nonprofit leader stated, “It was a knee-jerk reaction, because [they] couldn’t find houses, okay, and people didn’t have any place to go. So [the state government] said, hey, whatever it takes…And FEMA’s like, sure, 10 grand.”

Inflated Housing Prices

Finally, Figure 4 is a visual example of the theme inflated housing prices. While the image showcases a window with the flyers in support of the impacted Maui regions, it also has listings for at least a dozen homes on the island, ranging in price from the high six figures to seven figures, right next to those flyers. This image highlights the extremely high prices in the housing market in Maui, which was noted by many interviewees. The high cost of housing coupled with a lack of available housing units (i.e., limited supply on the island and abundance of short-term rentals) magnified housing insecurities and created a complex environment for residents looking to stay on the island.

Figure 4. Image Depicting the Theme Inflated Housing Prices

Seven interview participants mentioned the high cost of housing prior to the fires, which was exacerbated post-disaster because the fire had destroyed housing and displaced residents, including multigenerational families. Of the participants we interviewed, three were renters who had been displaced post-fire by the increase in rental costs caused by the housing shortage. One was living with a friend, another was living in their truck, and one was losing their current rental and was considering moving off the island. Our analysis of the social media data revealed similar concerns about rising housing costs and secondary rental displacement; we coded these posts with the theme addressing the housing crisis.

In addition to secondary rental displacement, various social media accounts described another form of displacement--families being kicked out of temporary housing. As there was limited housing availability on the island, hotels were temporarily housing displaced residents until they could be placed in FEMA housing. However, various social media posts complained that residents were being “kicked out” of hotels for mundane reasons (e.g., microwaving food, missing curfew, etc.). Without a place to live, residents on social media described the pain of having to move off Maui either to other islands or, in many cases, to other mainland U.S. states.

Opportunities in the Recovery Process

Our analysis showed that community members perceived three opportunities emerging during the recovery: (a) restoring the water, (b) honoring community strength and resilience, and (c) planning for the next disaster.

Restoring Historical Lahaina

Figure 5 is a visual display of the theme restoring the water. The picture depicts bright red signs that people had posted in public spaces and which contained messages like “Restore the Water” and “Defend the Land,” reminding tourists and residents alike that water and land restoration must be the priority for Lahaina. Five interviewees discussed restoring Native Hawaiian environment and specifically ways to restore the wai (freshwater streams). As one faith leader expressed:

There are lots of Hawaiians who want to establish Lahaina in a different way. Going back to the other way. And I, I haven't reckoned that with myself yet. Because I wasn’t part of that, where the water was flowing through the towns.

Conversations like these with interviewees included reflecting on what Lahaina looked like when the island was the Hawaiian Kingdom, with water flowing through what is now Front Street, or the greenspaces and infrastructure that existed at the time, almost as though the idea should be to turn Lahaina back in time. In the social media data, conversations related to this theme centered around environmental consideration and using traditional land use practices to restore natural protections against fire hazards.

Figure 5. Image Depicting the Theme Restoring the Water

Honoring Community Strength and Resilience

Figure 6 is a visual display of the theme honoring community strength and resilience. It provides a visual reminder of “We are Lahaina Strong” for all those who drive at the onset of the underpass, the only one that goes to and from Lahaina from the south side of the island. All interview participants mentioned the strength of the Maui community in their interviews. Specifically, six participants described how they relied on their community for aspects of their recovery, including getting food at food distribution hubs, furnishing their apartments with donations from neighbors, or using community contacts to find a place to live. As one participant said about support she received from other in Hawaiians, “[Our community is] very strong… The community is what has been the most helpful out of anything.” Our analysis of the social media data also showed that community members perceived strength in how they supported each other after the fire. We coded 43% of the social media posts as having content that highlighted efforts by community members to support one another during the recovery process, which was the most frequently occurring theme in our analysis.

Figure 6. Image Depicting the Theme Build on Community Resilience

Planning for the Next Disaster

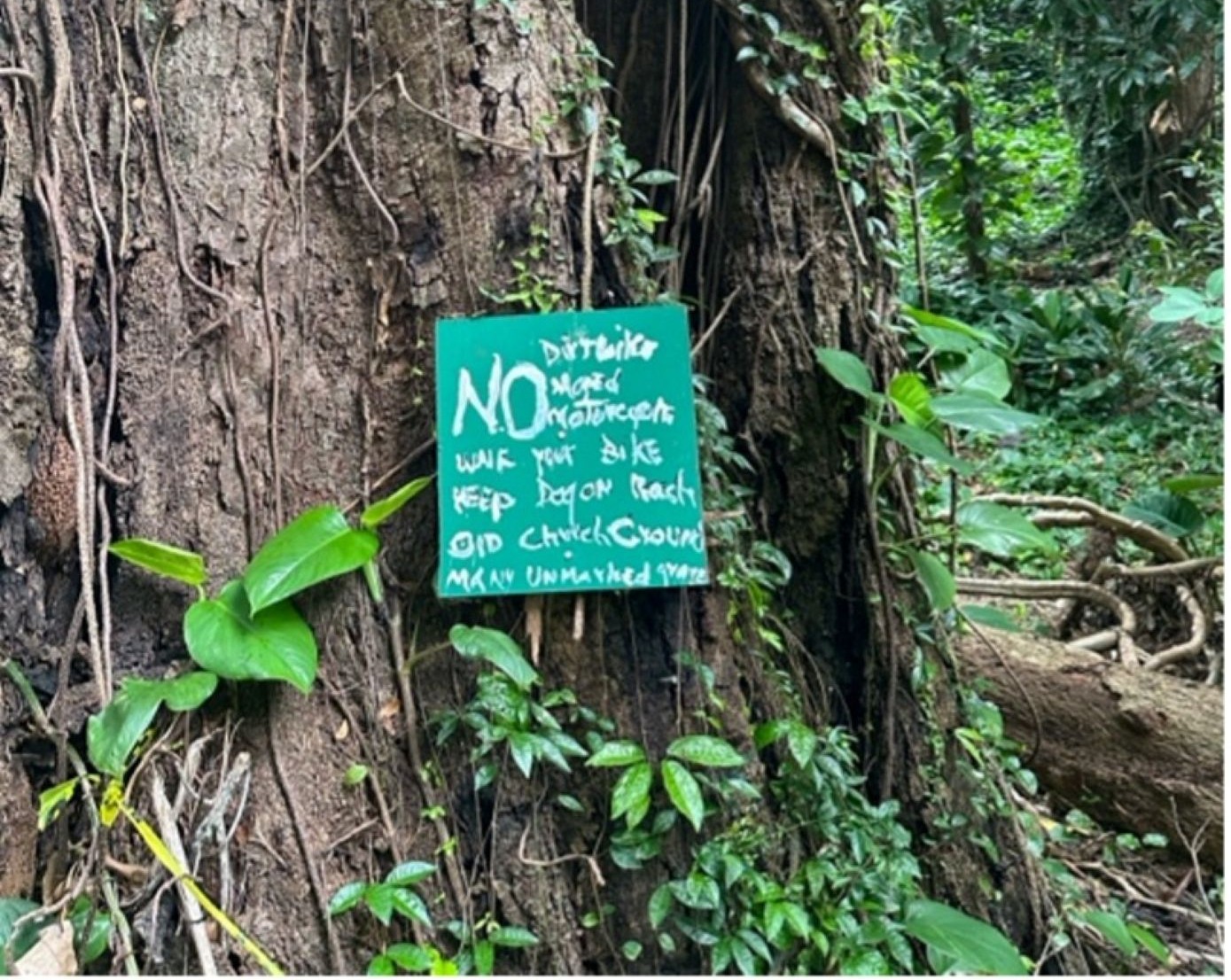

Finally, Figure 7 is a visual display of the theme planning for the next disaster. This sign, placed at the highway turn for one of the entrances going into Lahaina, serves as a daily reminder to all those who drive on their road, the consequences of this disaster. These temporary signs are also a reminder that Lahaina has one road in and one road out, accentuating the need to create emergency plans for the next disaster to help residents living in these areas evacuate. Most interviewees acknowledged that fires were becoming more frequent and destructive, and many lauded the almost overnight setup of community hubs that were run by community members and provided much-needed supplies for survivors, but only three interview participants specifically noted the specific actions to prepare for the next fire. These participants discussed the possibility of building resiliency hubs, which they described as places where organizations could come to distribute aid and information and where community members could find a safe place to evacuate. At a minimum, these participants stressed that the community needed to establish an evacuation plan and a “good evacuation route.” In the social media data, only 4% of posts discussed specific concerns with disaster mitigation or preparedness.

Figure 7. Image Depicting the Theme Planning for the Next Disaster

Discussion

The most unsurprising elements identified in the themes were distrust of government aid, inflated housing prices, and conversations centered around community resilience. As the storied past of the Hawaiian Islands indicates, trusting and accepting government assistance in the immediate aftermath and during the recovery process remains difficult. For instance, Figure 4, depicting support for survivors, was next to housing listings on the island—an irony which cannot be missed. One participant identified that FEMA’s direct lease program was inflating rent prices and exacerbating the already high housing costs on the island. Additionally, government agencies have inherent procedures and processes to follow, which often lead to unintended or unexpected administrative burdens for survivors. The discussions around community resilience were evident in many conversations with interviewees about how community hubs were built almost overnight to support resource distribution for survivors. This highlights the unique strength with which these hubs were formed and could be of interest to other communities around the world. The visuals from our study further cement this element, as motifs of support could be seen in unlikely places, and examples of this resilience were evident in our research in the conversations with residents.

Respect for survivors’ grief, restoring the water, and planning for the next disaster were unexpected themes for consideration that emerged from our study. Hawaiʻi’s unique culture and practices regarding their deceased created additional considerations that may not have been considered previously. A nonprofit worker we interviewed even said that many in her family believed she should not go into the burn zone because it was “tarnished with death.” As figure 5 indicated, many survivors in Lahaina see the site as a burial ground now, and in the recovery and rebuilding of the area, they want this respected.

Some discussions centered around restoration of the environment and the water. While some would like to see its traditional and cultural practices restored to its original esteem when it was the capital of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, others simply want that the waters to flow through the Front Street again, as some noted this rerouting of waters to other areas of the island and for large corporations is what propelled such a deadly event. The challenges that surround this restoration will have to consider these differing opinions, as well as what is conducive to a more disaster-resilient community.

Finally, interview participants highlighted that the disaster-prone nature of the island is unlikely to diminish in the near future. The lack of active discussions or consideration of how to plan for the next disaster are ongoing concerns for the community. This needs to be prioritized from an educational perspective, as well as an action item. For instance, one interviewee noted that having resiliency hubs for resources and safety would be a great asset. This could be easily manageable within the existing infrastructures (e.g., fire and police stations), which in turn might build trust between the community and government. However, many participants just wanted an evacuation route and standards for sounding warning alarms. These solutions, ranging from simple to extensive infrastructure considerations, must be discussed and decided upon by the governing structures in Maui, with input from the community and considering best practices that will minimize detrimental impacts of future disasters. With the current distrust and tensions that exist between the Federal government and community, this will be an additional bridge to cross to be successful in this endeavor.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice or Policy

One evident consideration for practice was that governing agencies need to continue their efforts to be transparent but also need to meet impacted residents where they are; they can do so by using community channels that are trusted. There are still gaps in the response and recovery initiatives. While some of these are unavoidable, others result from a lack of communication and management of resources. As identified in Figure 3, many community members distrusted the government at all levels (i.e., local, state, and federal), limiting their ability to serve impacted residents. However, there was a strong community and nonprofit presence as identified in Figure 2 and Figure 6. Bearing this in mind, practitioners need to align themselves with trusted local organizations and leaders.

From a policy perspective, there is a need to formalize affordable housing and emergency evacuation planning. As shown in Figure 4, housing has become unaffordable for some residents currently living on the island. The fires have exacerbated the felt impacts of housing insecurity as renters have experienced secondary displacement from FEMA housing applicants, residents waiting for FEMA housing experienced displacement from temporary housing and the high cost of building (as is evident in the listings in Figure 4) compel residents to move off island. In order to prevent further displacement, decision-makers need to prioritize affordable housing for both renters and those displaced from the fires. Additionally, Figure 7 highlighted the need for decision-makers to prioritize emergency evacuation planning as many interviewees expressed concerns over the current methods and routes to evacuate. In order to prevent future fatalities, decision-makers will need to address these concerns.

Finally, there is a need to incorporate place-based strategies that account for cultural considerations within the recovery process. Figure 1 and Figure 5 highlighted cultural concerns with honoring burial sites or respecting traditional methods for water restoration. Policies and programs aimed at helping residents recover and rebuild should focus on these place-based priorities by putting them at the forefront of recovery conversations.

Limitations

The first limitation was the adapted study protocol. In the field, we identified very quickly that our initial photo elicitation method would not work, as the distrust in the community was generalized to all they considered “outsiders.” This was a significant challenge to overcome at first, but provided more insight into how the community was so resilient within itself. The second limitation was in the process for collecting visual data, which included post-interview photographic confirmation by participants. This could lead to confirmatory bias based on subjective interpretations. To reduce this, we built in co-construction of the visuals and encouraged feedback where the participants could view and edit their images and descriptions. Lastly, as with any qualitative study, this study is not generalizable; however, we do not see this as a limitation of the work, but rather, insight into how diverse communities have different perspectives on recovery initiatives.

Future Research Directions

This study highlighted many of the unforeseen elements of disaster recovery and resilience, and some of the hindrances to it. For instance, government agencies have established procedures and processes to follow, often leading to unintended or unexpected administrative burdens for survivors. An example of this can be seen in Figure 3. This element was both insinuated and blatantly expressed by some interviewees and needs to be explored in future studies. This could include exploring how nonprofit or community organizations serve as a broker between survivors and governmental agencies that require specific information, to reduce those burdens. It could also include assessing post-disaster policies that dictate administrative procedures and processes, to streamline and simply requirements so that assistance can be provided more expediently. There are growing discussions around zero responders— a name that some have given to those people who “partake in the survival process because they are forced to take actions to protect their families and neighborhoods.” (Briones et al., 2019, p. 12240)—and how grassroots organizations and community members are able to spring to action and support the community in places where established organizations often cannot. These non-established disaster response groups and their motivations, values, and organization should be further studied and replicated, as they are a growing force for disaster response in many communities. Lastly, the management of the mass fatality incident that these fires caused, and the inherent cultural and social practices that should be (and were) considered by governmental agencies when managing it, must be further explored. We are exploring some of these issues as well as how they can be transferred to other disaster contexts or geographical locations.

Acknowledgments. We would like to express our deepest thanks to the many people who made this effort possible. Lauren Azevedo, Assistant Professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, spearheaded our effort to secure interviews with organizational representatives prior to our data collection trips. Savannah Havird and Megan Corn, students in the Master’s in Public Administration (MPA) program at the University of South Florida, collected previous research and documentary data that we used to develop the background information and social network analysis we describe in this report. Christa Remington, Assistant Professor at the University of South Florida, connected us with her family friends near Lahaina in Maui and shared her expertise on analyzing social media data. Wangchuk Dema, MPA student at the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa, who collected the social media posts that we analyzed for this project. The University of South Florida Humanities Institute provided internal funding and support that allowed Dr. Dougherty to conduct this work. Lastly, we are grateful for the community members and organizational representatives who took the time to talk story with us and trusted us to share their voices through our work. Mahalo and a hui hou (thank you and until we meet again).

References

-

Maui Police Department. (2024). Maui wildfires of August 8, 2023: Maui Police Department Preliminary After-Action Report. https://www.mauipolice.com/_files/ugd/fefc36_72030e3e1aff4754bd9bf13889b50a0e.pdf ↩

-

Ing, K. (2023, August 17). The climate crisis and colonialism destroyed my Maui home. Where we must go from here. Time Magazine. https://time.com/6305817/maui-wildfires-climate-change-colonialism-essay/ ↩

-

Onstad, P. A., Danes, S. M., Hardman, A. M., Olson, P. D., Marczak, M. S., Heins, R. K., & Coffee, K. A. (2017). The road to recovery from a natural disaster: Voices from the community. In B. Hales, N. Walzer, & J. Calvin (Eds.), Innovative Community Responses to Disaster (pp. 39-53). Routledge. ↩

-

Morello-Frosch, R., Brown, P., Lyson, M., Cohen, A., & Krupa, K. (2011). Community voice, vision, and resilience in post-Hurricane Katrina recovery. Environmental Justice, 4(1), 71-80. ↩

-

Duval-Diop, D., Curtis, A., & Clark, A. (2010). Enhancing equity with public participatory GIS in hurricane rebuilding: Faith based organizations, community mapping, and policy advocacy. Community Development, 41(1), 32-49. ↩

-

Gotham, K. F., & Greenberg, M. (2014). Crisis cities: Disaster and redevelopment in New York and New Orleans. Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Kapucu, N., Yuldashev, F., & Feldheim, M. A. (2018). Nonprofit organizations in disaster response and management: A network analysis. Journal of Economics and Financial Analysis, 2(1), 69-98. ↩

-

Mathias, J., Burns, D. D., Piekalkiewicz, E., Choi, J., & Feliciano, G. (2022). Roles of nonprofits in disaster response and recovery: Adaptations to shifting disaster patterns in the context of climate change. Natural Hazards Review, 23(3), Article 04022011. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000559 ↩

-

Winkworth, G. (2007). Disaster recovery: A review of the literature. Institute of Child Protection Studies. https://acuresearchbank.acu.edu.au/item/85yx2/disaster-recovery-a-review-of-the-literature ↩

-

Ka'anapu, K. (2023). Paradise on fire: How Hawai‘i developed one of the worst wildfire problems in America. Intersections: Journal of Asia Pacific Undergraduate Research, 1(1), 53-69. ↩

-

Ainsworth, A., & Drake, D. R. (2024). Hawaiian subalpine plant communities: Implications of climate change. Pacific Science, 77(2-3), 275-296. ↩

-

Bremer, L. L., Mandle, L., Trauernicht, C., Pascua, P., McMillen, H. L., Burnett, K., Wada, C. A., Kurashima, N., Quazi, S. A., Giambelluca, T., Chock, P. & Ticktin, T. (2018). Bringing multiple values to the table: Assessing future land-use and climate change in North Kona, Hawaiʻi. Ecology and Society, 23(1), 1-34. ↩

-

Tran, T. T. K., Janizadeh, S., Bateni, S. M., Jun, C., Kim, D., Trauernicht, C., Rezaie, F., Giambelluca, T. W., & Panahi, M. (2024). Improving the prediction of wildfire susceptibility on Hawaiʻi Island, Hawaiʻi, using explainable hybrid machine learning models. Journal of Environmental Management, 351, Article 119724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119724 ↩

-

Trauernicht, C., Pickett, E., Giardina, C. P., Litton, C. M., Cordell, S., & Beavers, A. (2015). The contemporary scale and context of wildfire in Hawai‘i. Pacific Science, 69(4), 427-444. ↩

-

Finlay, S. E., Moffat, A., Gazzard, R., Baker, D., & Murray, V. (2012). Health impacts of wildfires. PubMed Central. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3492003/ ↩

-

Steelman, T. A., McCaffrey, S. M., Velez, A. L. K., & Briefel, J. A. (2015). What information do people use, trust, and find useful during a disaster? Evidence from five large wildfires. Natural Hazards, 76, 615-634. ↩

-

Zheng, J. (2023). Exposure to wildfires and health outcomes of vulnerable people: Evidence from US data. Economics & Human Biology, 51, Article 101311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2023.101311 ↩

-

Kooistra, C., Hall, T. E., Paveglio, T., & Pickering, M. (2018). Understanding the factors that influence perceptions of post-wildfire landscape recovery across 25 wildfires in the northwestern United States. Environmental Management, 61, 85-102. ↩

-

Kulig, J., & Botey, A. P. (2016). Facing a wildfire: What did we learn about individual and community resilience? Natural Hazards, 82, 1919-1929. ↩

-

Miller, R. K., & Mach, K. J. (2021). Roles and experiences of non-governmental organisations in wildfire response and recovery. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 31(1), 46-55. ↩

-

Moloney, K., Vickery, J., Hess, J., & Errett, N. (2023). After the fire: A qualitative study of the role of long-term recovery organizations in addressing rural communities’ post-wildfire needs. Environmental Research: Health, 1(2), Article 021009. https://doi.org/10.1088/2752-5309/acd2f7 ↩

-

McGee, T. K., McCaffrey, S., & Tedim, F. (2020). Resident and community recovery after wildfires. In F. Tedim, V. Leone, & T. K. McGee (Eds.), Extreme Wildfire Events and Disasters (pp. 175-184). Elsevier. ↩

-

Ryan, R. L., & Hamin, E. (2008). Wildfires, communities, and agencies: Stakeholders' perceptions of postfire forest restoration and rehabilitation. Journal of Forestry, 106(7), 370-379. ↩

-

Weisenfeld, G. (2012). Imaging disaster: Tokyo and the visual culture of Japan’s Great Earthquake of 1923 (Vol. 22). University of California Press. ↩

-

Callender, B., Obuobi, S., Czerwiec, M. K., & Williams, I. (2020). COVID-19, comics, and the visual culture of contagion. The Lancet, 396(10257), 1061-1063. ↩

-

Stubblefield, T. (2014). 9/11 and the visual culture of disaster. Indiana University Press. ↩

-

Lorenz, L. S., & Kolb, B. (2009). Involving the public through participatory visual research methods. Health Expectations, 12(3), 262-274. ↩

-

Rose, G. (2014). On the relation between ‘visual research methods’ and contemporary visual culture. The Sociological Review, 62(1), 24-46. ↩

-

Kelly, A. H., Keck, F., & Lynteris, C. (Eds.). (2019). The anthropology of epidemics. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429461897 ↩

-

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13-26. ↩

-

Vogeler, K. (2014). Outside Shangri La: Colonialization and the US occupation of Hawaiʻi. In N. Goodyear-Kaopua, I. Hussey, & E. K. A. Wright, (Eds.), A Nation Rising: Hawaiian Movements for Life, Land, and Sovereignty (pp. 252-266). Duke University Press. ↩

-

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369-387. ↩

-

Jenkings, N. K., Woodward, R., & Winter, T. (2008, September). The emergent production of analysis in photo elicitation: Pictures of military identity. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1169 ↩

-

Noland, C. M. (2006). Auto-photography as research practice: Identity and self-esteem research. Journal of Research Practice, 2(1), 1-19. ↩

-

Barnard, D. (2006). Law, narrative, and the continuing colonialist oppression of native Hawaiians. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review, 16, 1-46. ↩

-

Hall, L. K. (2008). Strategies of erasure: US colonialism and native Hawaiian feminism. American Quarterly, 60(2), 273-280. ↩

-

Silva, N. K. (2004). Aloha betrayed: Native Hawaiian resistance to American colonialism. Duke University Press. ↩

-

Simpson Steele, J. (2012). Talk-story: A quest for new research methodology in neocolonial Hawai‘i. Youth Theatre Journal, 26(1), 38-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/08929092.2012.678213 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023, December 18). Frequently asked questions about FEMA’s direct lease program. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.fema.gov/fact-sheet/frequently-asked-questions-about-femas-direct-lease-program ↩

-

Briones, F., Vachon, R., & Glantz, M. (2019). Local responses to disasters: Recent lessons from zero-order responders. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 28(1), 119-125. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-05-2018-0151 ↩

Dougherty, R. B., II, & Witkowski, K. (2025). Local Voices of Maui: Critical Visual Reflections From the 2023 Maui Fires. (Natural Hazards Center Weather Ready Research Report Series, Report 14). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/local-voices-of-maui