Support for Prescribed Burning in Midwestern States

Results From an Online Experiment

Publication Date: 2025

Abstract

Prescribed fire is a sound measure to prevent wildfires, but it is often opposed by citizens who fear that it will escape and spread. Consequently, policymakers who craft prescribed fire policies must weigh the advice of experts against the desires of their constituents. To investigate how decision-makers weigh information provided by experts or citizens as well as their own risk perceptions when evaluating prescribed burning, we conducted an online experiment with 166 participants from the Midwest. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental treatments: Both groups were given the same short informational text, but one was told it was written by local community members whereas the other group was told it was written by experts from their local prescribed fire council. Our results showed that neither the citizen nor the expert experimental interventions influenced support for prescribed burning. The only meaningful predictor of support for prescribed burning was pre-existing support for it. Descriptive analyses of policymakers’ responses showed that they were experienced with prescribed burning and had positive attitudes. However, most policymakers thought that their constituents would feel uncomfortable with the implementation of prescribed burning, seemingly underestimating levels of support in the population. These findings suggest that policymakers falsely believe that the public holds more negative attitudes than they really do. Resolving this cognitive bias, while also further strengthening citizens’ support, might encourage policymakers to support legislation that promotes prescribed burning.

Introduction

Prescribed burning is an environmentally friendly and reliable tool to reduce wildfire risk by decreasing the amount of natural fuel available (Clark et al., 20221). The U.S. Forest Service conducts many prescribed burns; however, outside of federal lands, they are often executed by prescribed fire councils, which are groups that promote and facilitate safe and effective prescribed fire use (Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils, 20222). Based on their experience and goals, these councils operate as experts on prescribed fires in their respective regions.

A major impediment to prescribed burning is negative public perception. Many people perceive prescribed fires as dangerous and irresponsible (Melvin, 20183). Despite major public concern about prescribed fires escaping their perimeters, these events are exceedingly rare, occurring in only 1% of prescribed burns (Joshi et al., 20194; Weir et al., 20195, 20206). Other major impediments, such as smoke management laws and liability concerns, are also connected to public perceptions, with public citizens often strongly opposed to smoke or air pollution resulting from prescribed fires (Weisshaupt et al., 2005 7). Indeed, one escaped prescribed fire in a region can potentially reduce public support for decades (McCaffrey, 2009 8), often leading policymakers to implement stricter liability laws.

County commissioners are crucial decision-makers when it comes to prescribed burning, especially in the Midwest—a region experiencing increased wildfire risk (Behrer & Wang, 20239). These elected officials are responsible for enforcing or repealing outdoor burning bans, which can help prevent wildfires in dry periods, but also impact prescribed burning. County commissioners may also grant burn ban exemptions to trained burners ( et al., 2022). Consequently, county commissioners find themselves pressed by both members of the public, who tend to be relatively skeptical of prescribed fires, and experts, who are often advocates of them (McDaniel et al., 202110).

The purpose of this study is to shed light on how expert opinions, public opinions, and personal risk perceptions interplay in influencing people’s support for prescribed fire policies. We designed an online experiment to investigate how people’s support for prescribed fires is affected by an informational text supposedly written by the public versus one written by experts. We also assessed how their pre-existing views of prescribed fires were related to their support for policies that allow or further the implementation of prescribed burning. We hypothesized that participants in the experiment would consider the views of the public and experts, but would be predisposed to making decisions that aligned with their own pre-existing opinions. This process—trying to find and interpret information in line with one’s own worldviews and motivations—is called motivated reasoning (Kunda, 199011). Previous studies have found substantial evidence of motivated reasoning among public officials (Baekgaard et al., 201912; Christensen & Moynihan, 202413).

Literature Review

Before we detail how motivated reasoning might influence policymakers’ decisions on wildfire prevention, we first discuss the basis of the conflict that policymakers must solve: differences between best practice information provided by experts and the will of the citizenry, which does not necessarily align with evidence.

Expertise and Accountability

The tension between technocratic expertise and democratic accountability is the subject of longstanding debate (Bertsou & Caramani, 202014). Public officials are expected to base their decisions on evidence while at the same time attending to their constituents’ preferences. This tension is especially relevant in the context of risk policies, about which citizens often hold different opinions than experts (Siegrist & Árvai, 202015) or are perceived as having irrational risk perceptions (Jasanoff, 199816). Despite the vast body of literature documenting the use of evidence and expertise for policymaking (Nutley et al., 200717; Weiss, 197918), there is surprisingly little research investigating how policymakers deal with this tension in practice. Research has shown that when policymakers are making decisions about risk management, they rank listening to citizens as more important than listening to experts (Sjöberg, 200119). Relatedly, substantial research has investigated which sources citizens trust (e.g., scientists, media, environmental organizations; Brewer & Ley, 201320). However, caution is advised when drawing conclusions from citizens’ preferences on who to trust about policymakers’ preferences, as policymakers might have other ways to go (e.g., because of their own expertise in decision-making) when evaluating information from various sources.

Motivated Reasoning Theory

When facing a policy question in which expert opinion and that of the public conflict, policymakers might solve the tension by referring to their own preconceived opinions and attitudes on the matter. This cognitive process is known in psychology as motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990). According to motivated reasoning theory, information is processed selectively based on one’s prior opinions. This means that evidence is not uniformly accepted; instead, people tend to interpret information (even scientific evidence) in a way that conforms with their pre-existing attitudes. Additionally, two basic motivations influence people’s processing of information: accuracy and direction (Kunda, 1990). Accuracy promotes interpreting information as objective regardless of the implications. Directionality is the will to use information to arrive at the conclusion that matches what a person already believes. For policymakers, the directional goal might be more influential because they have to make ideologically informed decisions. Policymakers, on average, have stronger political attitudes than citizens. Strong political beliefs relate to stronger tendencies toward motivated reasoning (Kahan, 201321). Requiring a justification for decisions weakens motivated reasoning for non-decision-makers, but strengthens it among policymakers (Christensen & Moynihan, 2024). To the best of our knowledge, motivated reasoning in policymakers has yet to be tested when comparing the influence of information sources, and no research has examined the phenomenon in the context of risk policies and investigating biased reasoning in policy.

County Commissioners and Burn Ban Decisions

When considering the role of county commissioners in prescribed fire decision-making, the difference between what policymakers say and the actions they take becomes clear. Research on the U.S. southern plains finds that county commissioners say they listen to local fire departments—which are often represented in prescribed fire councils as well—but in practice tend to align their decisions with public risk perceptions (McDaniel et al., 2021). County commissioners can implement burn bans that essentially ban all open fires in their jurisdiction, which also may include prescribed fires (Clark et al., 2022). While burn bans and related regulations vary widely by state, research has shown they often impede the use of prescribed burning across the United States (Clark et al., 2022). Our own conversations with prescribed fire council members in Indiana and Illinois confirmed this issue in the Midwest. In general, experts favor prescribed burning because research has shown that prescribed burning is effective and efficient in preventing wildfires (McDaniel et al., 2021). In contrast, many members of the public are wary of prescribed burning because of the perceived risk of fire unintentionally escaping and spreading. With our research, we aimed to unravel how support for prescribed burning was affected by exposure to technocratic knowledge and public risk perceptions.

Research Questions

We designed an experiment to answer the following research questions:

- How is people’s support for prescribed burning affected by information they receive from the public and experts?

- How do preconceived opinions about prescribed burning influence people’s support for prescribed burning policies?

Research Design

We conducted an online experiment using a between-subjects experimental design with pre-intervention and post-intervention assessments of policy support. Initially, we planned to sample county commissioners in the Midwest and explore their support for prescribed burning and whether information from experts or constituents affected the policy decisions they made about prescribed fires within their county. However, as described in more detail below, a very low response rate among the county commissioners caused us to adapt our study plan. We shifted to recruiting residents in the Midwest using an online panel and focusing on how information from experts or citizens affected their support for prescribed burning. We opted to use an online experiment in order to minimize as much as possible the time needed to respond. We preregistered our original study plan (Gerdes et al., 202422) and published our dataset and instruments (Jose et al, 202423) on the Open Science Framework data repository website for transparency and to increase reproducibility of our research.

Study Location and Outreach

We conducted our study in the Midwestern states of Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, and Wisconsin. We chose these states because they each have an active prescribed fire council and decision-makers at the county level (i.e., county commissioners or fire chiefs). To better understand the prescribed burning climate and policies in the Midwest, we met with two leaders from the Indiana prescribed fire council and one leader from the Illinois prescribed fire council, respectively, and discussed the current state of wildfire prevention and policymaking in their area prior to setting up the experiment. After completing the study, we also hosted a meeting at the 2024 Northeast-Midwest Prescribed Fire Workshop in Albany, New York, where we shared our preliminary findings with and received feedback from practitioners and researchers from the Midwest.

Online Experiment

Sampling Strategy and Recruitment

Following our initial study plan, we targeted county commissioners and fire chiefs in four Midwestern states—Missouri, Indiana, Illinois, or Wisconsin—to participate in the study. To recruit them, we collected their email addresses and phone numbers from public webpages and invited them to participate in the experiment via email. Later, we called their offices to remind them to take part in the survey. We sent invitation emails over a 2-week period at the beginning of March 2024 to approximately 390 county commissioners and fire chiefs. Between March 11 and April 1, 2024, a research assistant called the county commissioners’ offices to ask them to take part in the survey. On June 20, 2024, we sent out a last reminder. In total, five county commissioners provided usable data (response rate ~1%). Because our efforts to recruit county commissioners and fire chiefs did not result in a sufficient sample, we shifted to recruiting adults in the Midwest using an online panel from Prolific in July 2024. Of the responses we received, we excluded from the sample those participants who failed an attention check—which had instructed them to click on “somewhat agree”—because it suggested that they were not properly reading the survey questions. We also excluded two participants who reported that they did not live in Missouri, Indiana, Illinois, or Wisconsin. The final sample of adults in the Midwest consisted of 161 participants.

Survey Sample

Of the five participants in the county commissioner sample, only three provided demographic information: The three participants were male, two lived in Missouri and one in Illinois, and their ages were between 45 and 57 years old. In the public sample, 50.3% of participants identified as male, 46.0% as female, and 3.1% as non-binary. They ranged in age from 18 to 82 (M = 37.35, SD = 12.38). Their state of residence was evenly distributed, with 23.6% of participants living in Missouri, 26.1% each in Indiana and Illinois, and 24.2% in Wisconsin. The majority (67.7%) lived in predominantly urban counties. Two participants in the public sample reported that they currently serve as county commissioners. These individuals’ results were included in the county commissioner analyses, as described in the Results section.

Experimental Design and Procedures

The experiment was designed to assess how participants’ support for prescribed burning was affected by an informational text and, importantly, by the source (citizens or experts) that supposedly provided the information. We used a between-subjects experiment research design, which involved manipulating one independent variable (source of information) with two conditions (citizens and experts). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental treatments: Both groups were given the same short informational text, but one was told it was written by local community members whereas the other group was told it was written by experts from their local prescribed fire council. Of the 166 participants, 74 were in the citizen condition and 87 were in the expert condition. Before the experimental intervention, we assessed participants’ pre-intervention prescribed burning support with a six-item survey. Afterward, we measured their post-intervention prescribed burning support with a 10-items survey. Endnote 1

Survey Measures

To assess participants’ support for prescribed burning we developed a questionnaire with measures of the following topics: (a) opinions about prescribed burning, (b) expressions of support for policies that would allow the implementation of prescribed burning, and (c) past behavior in support of prescribed burning (Jose et al., 2024). We distributed those items across the two assessment points to avoid repetitiveness in the questionnaire. As mentioned above, the pre-intervention assessment had six items whereas the post-intervention assessment had 10 items. Four of those 10 items were repeated from the pre-intervention assessment. Pre- and post-intervention prescribed burning support were calibrated as a Rasch scale. The Rasch model was originally designed to assess student skill levels by assigning scores in skill tests that compared student skill levels to the level of a test item’s difficulty (Rasch, 1960/198024). Recently researchers in psychology have applied Rasch scales to improve how to assess and quantify latent variables such as attitudes based on behavioral indicators (i.e., relying on the idea that people’s attitudes become observable in their overt behaviors; Kaiser et al., 201025). A recent study used a Rasch scale to assess environmental policy support (Kaiser et al., 202326:).

To avoid violations of local independence, we independently calibrated pre- and post-intervention prescribed burning support. Because estimates from two separate calibrations are not on the same scale per se, we rescaled support post-intervention into the metric of support pre-intervention (Kolen & Brennan, 201427). Two negatively formulated items were inversely coded. To apply the dichotomous Rasch model, we recalibrated items by collapsing the responses 1, 2, and 3 on the original 5-point response scales into 0 (“no active support”) and the responses 4 and 5 into 1 (“active support”).

Seventeen participants had scores of 0, which indicating they had “no active support” on all items. Twenty participants had perfect scores, which indicated that they had “active support” on all items. Because their responses had no variability, the Rasch model could not estimate their level of prescribed burning support. We replaced the missing values for those participants with the lowest estimated score from the Rasch calibration and the highest estimated score, respectively. We tested the goodness of fit of the two scales; results are presented in Table 1. Separation reliability was comparably low, but not surprisingly so considering that we applied an ad-hoc measure with a small number of items. Item fit was good as indicated by weighted mean squares which are within recommended benchmarks (Wright et al., 199428).

Table 1. Calibration Results of the Prescribed Burning Support Scales

Prescribed Burning Support |

Prescribed Burning Support |

|

|---|---|---|

| Item Fit Statistics | ||

| Mean Squares (Standard Deviation) | ||

| Minimum Mean Squares | ||

| Maximum Mean Squares | ||

| Person Fit Statistics | ||

| % of people with underfit (t ≤ 1.96) | ||

| Separation Reliability | ||

Data Analysis

We focused our quantitative data analyses on the sample of public participants. We tested two hypotheses based on our research questions and as specified in the pre-registration:

Hypothesis 1: People’s support of prescribed burning is influenced by whether they receive information on prescribed burning from citizens or experts.

To test Hypothesis 1, we applied with two statistical tests: (a) the correlation of participants pre-intervention support for prescribed burning support with their post-intervention support and (b) a t-test for paired data. To correct for measurement error, we corrected the correlation for attenuation. With a t-test for independent samples, we tested whether post-intervention prescribed burning support differed between participants who

Hypothesis 2: The impact of the information source on people’s support of prescribed burning is moderated by their pre-existing support of prescribed burning.

To test Hypothesis 2, we applied a multi-factorial analysis of variance, including the source of the message, pre-intervention prescribed burning support, and state of residence as predictors of post-intervention support. In this model, we also investigated whether the moderators—pre-intervention support and state of residence—interacted with the main predictor, the source of the message, in their effect on post-intervention support.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

The study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the State University of New York at Buffalo (STUDY00007803) on November 29, 2023. Our research adheres to the American Psychological Association’s (201729) ethical code of conduct for research with human participants. Data was collected anonymously. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and public participants received approximately $1.35 for participation (estimated because Prolific billed in pound sterling). In the beginning of the study, participants were informed that the study’s purpose was to assess their opinions about prescribed burning and how they approach making decisions about prescribed burning. At the end, participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation. Policymaker participants who were approached during our original effort to sample only county commissioners received the opportunity to win a gift card for $100 and to be invited to a workshop about the study results. A multi-disciplinary team conducted the research. Esther Jose, with her background applying operations research to prescribed fire policy, contributed her knowledge of prescribed burning in the United States. Wouter Lammers, with his background in public governance, contributed his knowledge of policymaker decision-making. Ronja Gerdes, as a social psychologist, contributed her knowledge of scale development and policy support.

Results

We present our results in three sections. In the first section, we provide an overview of public sample’s responses to the pre- and post-intervention surveys using descriptive statistics. In the second section, we test our hypotheses using more advanced statistical analyses of the public sample’s responses. In the third section, we compare the responses from policymakers to those from citizens from the public sample.

Overview of Responses to Prescribed Fire Survey Items

Table 2 shows the public sample’s responses to the pre- and post-intervention survey questions about prescribed fire. Only 17 (10.7%) participants from the public sample reported that they had previously attended or conducted prescribed fires. A minority of the public sample (40.9%) said that they felt well-informed about prescribed fires before the intervention. Even after the intervention that provided information on the safety of prescribed burning, most respondents (62.3%) said that prescribed fires were risky because of the potential for escapes. Most (52.8%) also said constituents in their county would be uncomfortable with prescribed fires. After the intervention, strong majorities, however, said that prescribed fires were “effective in reducing the risk of wildfires” (84.3%) and “essential tools for healthy forests or grasslands” (78.6%). After having received information on prescribed burning, majorities also indicated their support for offering monetary incentives to landowners for conducting prescribed fires (56.0%) or for encouraging them to allow state organizations to conduct prescribed fires on their grounds (66.7%). At the same time, only a minority supported state laws that lower liabilities for certified prescribed burners (45.9%).

Table 2. Survey Responses From the Public Sample

| Pre-Intervention Survey Items | ||||

| I have attended or conducted prescribed fires. | ||||

| If you were a county commissioner, would you be willing to exclude prescribed fires from burn bans if they are conducted for… | ||||

| Prescribed burning is effective in reducing the risk of wildfires. | ||||

| I feel well-informed about prescribed burning. | ||||

| Post-Intervention Survey Items | ||||

| If you were a county commissioner, would you be willing to exclude prescribed fires from burn bans if they are conducted for… | ||||

| If you were a county commissioner, would you be willing to support or implement the following policies in your county or state? |

||||

| Prescribed burning is effective in reducing the risk of wildfires. | ||||

| Prescribed burning is an essential tool for healthy forests or grasslands. | ||||

| Prescribed burning is dangerous because of the potential for escapes. | ||||

| My constituents would feel uncomfortable with the implementation of prescribed fires. | ||||

An overview of the survey responses from the seven participants Endnote 2 that identified themselves as county commissioners can be found in the appendix.

Effects of Intervention on Support for Prescribed Burning

The public sample’s support for prescribed burning before and after the intervention was strongly correlated (r = .50) and perfectly correlated when corrected for measurement error (rcorr = 1.00). Furthermore, participants’ support for prescribed burning before the intervention (M = 0.20, SD = 1.52) did not significantly differ (p = .886) from their support after the intervention (M = 0.22, SD = 1.53). Participants’ support for prescribed burning after reading the vignettes did not significantly differ (p = .994) between people in the citizen condition (M = 0.22, SD = 1.53) and the expert condition (M = 0.22, SD = 1.53).

To test for motivated reasoning and potential state effects, we conducted a multi-factorial analysis of variance which included pre-intervention prescribed burning support and state of residence as predictors. The overall model was significant (F[9, 151] = 5.73, p < .001) and explained 25.4% of variance in post-intervention prescribed burning support (indicated by R2). The source of the message (citizens or experts) did not influence participants’ post-intervention support (F[1, 151] = 0.14, p = .709). At the same time, pre-intervention support had significant influence on post-intervention support (F[1, 151] = 48.32, p < .001). The source of the message and pre-intervention support did not interact in their influence on post-intervention support (F[1, 151] = 0.22, p = .730). The state in which participants resided did not influence their post-intervention support (F[3, 151] = 0.19, p = .905). Unsurprisingly, the source of the message and state of residence did not interact in their influence on post-intervention support (F[3, 151] = 0.08, p = .973).

Comparison of Policymaker and Public Support for Prescribed Burning

In this section, we compare the responses from the seven county commissioners who participated in the study to the public sample. Because the policymaker sample is very small, this analysis is exploratory, and we have mostly refrained from applying statistical inference.

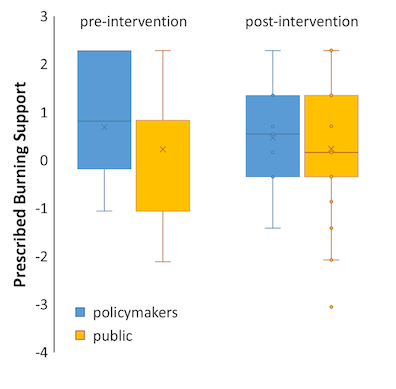

Figure 1 displays the boxplots of support for prescribed burning before and after the intervention among policymakers and the public. Support did not differ before or after the intervention. Before the intervention, policymakers appeared to be more supportive of prescribed burning (M = 0.67, SD = 1.27) than the public (M = 0.21, SD = 1.53). The low power of the policymaker sample does not allow for testing statistical difference here. It is possible that our policymaker sample is biased towards policymakers who are relatively strongly supportive of prescribed burning because people who hold strong opinions about the survey topic are more likely to take part, a phenomenon known as self-selection bias (that might be extremely prevalent in a sample with a low response rate such as our policymaker sample; Whitehead, 199130). After the intervention, support in the two groups was more similar than before (policymakers: M = 0.45, SD = 1.19; public: M = 0.23, SD = 1.54).

Figure 1. Support for Prescribed Burning Before and After the Intervention Among Policymakers and the Public

Our analysis also showed that the policymakers in the sample had more direct experience with prescribed fires (28.6%) and were more likely to feel well-informed about them (57.1%) than the general public. Policymakers were also more likely to reject the premise that prescribed burning is potentially dangerous (60%, n = 5). Three out of five policymakers who responded to the respective item agreed that their constituents would feel uncomfortable with the implementation of prescribed fires, however, suggesting that they are aware that citizens perceive prescribed fires as risky.

Discussion

Providing information about prescribed burning, along with the source of the information, did not change people’s pre-existing prescribed burning support. Their pre-existing support before the intervention was the only meaningful predictor of their level of support after the intervention. There might be two reasons for these effects. First, we kept the vignettes short because we anticipated that policymakers would not have much time to respond to our survey. Arguably, reading a short paragraph about prescribed burning was not strong enough as an intervention to change people’s opinion. Second, a large share of participants (41.6% across the two samples) somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement that they felt well-informed about prescribed burning even before the intervention. Therefore, it is likely that they held preconceived opinions and were not “blank slates” before receiving our information, making them susceptible for motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990). From our results, we can conclude that preconceived opinions are a much stronger determinant for policy support than an informational intervention.

Accordingly, and as becomes apparent in the perfect correlation between pre-intervention and post-intervention prescribed burning support, people were unlikely to change their opinion about prescribed burning after the experimental intervention. At least within our study, people’s existing attitudes towards prescribed burning seemed to be stable. Furthermore, support also was not influenced by the state in which participants lived. This is unsurprising as we picked the states based on their similarity.

We descriptively compared the data from seven policymakers to the data from the general public. Policymakers had higher pre-existing support for prescribed burning. The policymakers in our sample tended to have more hands-on experience with prescribed burning and perceived prescribed burning as less risky than the general public. Interestingly, policymakers seemed to be aware that the public tends to view prescribed burning as risky. Most policymakers reported that they think their constituents would feel uncomfortable with the implementation of prescribed burning, potentially underestimating policy support in the population.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice and Policy

From our research, we conclude that even members of the public who mostly have no personal experience with wildfire prevention already have preconceived attitudes about prescribed burning, as people in the Midwest generally understand what prescribed burning is. From previous research, we know that policy support is a function of an overarching goal (Kaiser et al., 2023). Expectedly, people support prescribed burning because they understand prescribed burning helps to reach an overarching goal (e.g., protecting the environment from wildfires, maintaining hunting grounds). Said differently, people’s commitment to a more general goal, such as conservation or hunting, drives their support for policies that help reach that goal.

Originally, we were interested in how policymakers decide on the implementation of seemingly risky wildfire prevention measures such as prescribed burning. From our research, we can cautiously assume that policymakers in the Midwest are educated on prescribed burning and deem its risk to be low. However, they also think that citizens in their county might not be supportive of prescribed burning, which might lead to their reluctance to lower liability for certified prescribed fire burners. Other research suggests that policymakers are guided by political feasibility that is partly based on their conception of citizen support (Gärling & Loukopoulos, 200731). Our results (presented in Table 2 and in the Appendix), however, speak for pluralistic ignorance (the factually wrong conviction that other people hold different beliefs than oneself; Allport, 192432; Katz & Allport, 19333) in both groups, the public and policymakers. Apparently, policymakers as well as the public are prone to believe that, although they themselves are in favor of prescribed burning, other people will not support policies that promote prescribed burning. Wildfire prevention efforts could benefit from efforts to dispel pluralistic ignorance, especially in policymakers. However, in light of the findings that mere information often does not help to change preconceived beliefs (that our own research contributes to), this might be a rather ambitious endeavor in itself (for an overview of potential interventions and their shortcomings, see Miller, 2023 34).

Limitations

The biggest limitation of our study was that we were unable to recruit a sufficient sample of policymakers to answer our original research questions. We deviated from our original study plan by recruiting members of the public to participate. Furthermore, our descriptive analysis of the seven policymakers needs to be interpreted cautiously, because of the very small sample size.

Lastly, we assessed policy support with a newly developed and rather short Rasch scale. As can be expected when there is little information provided per participant, separation reliability (i.e., how well the scale can discriminate between people based on their support) was comparably low (see Table 1). At the same time, when each item is answered by a comparably large number of participants, the items fit the scale rather well, as indicated by mean squares presented in Table 1. We believe that our calibration approach was sensible, because the Rasch model at least uncovers these issues when measuring a psychological attribute with a small number of ad-hoc constructed items. Another advantage of our measurement approach was that we could calibrate pre- and post-intervention policy support on the same scale without repeating the exact same set of items before and after the intervention. This is possible because Rasch measures possess the trait of specific objectivity—that is, a fixed set of indicators is not necessary to assess a psychological attribute (Kaiser et al., 201835). From the results of the Rasch calibration, we can derive information on how to improve the scale for future research assessing support for prescribed burning.

Future Research Directions

We set out to understand whether policymakers make decisions about wildfire prevention measures based on their own preconceived opinions or information provided by citizens or experts. Due to the low response rate of county commissioners, we were not able to answer our original research questions. There are several ways to address this problem. First, increasing the pool of potential participants by including more states and strengthening efforts to recruit participants might increase the number of policymakers taking part in the survey. For example, participants may be motivated by more reminder emails and calls; personal visits; active involvement of prescribed fire councils in the recruitment process; and better compensation. Second, it might be necessary to apply a qualitative approach, such as focus groups with policymakers, to receive insights into how policymakers make their decisions on wildfire prevention measures. Apart from applying new approaches to study our original research questions, we also believe there are other aspects of prescribed burning policymaking that deserve exploration. First, it would be worthwhile to investigate what kind of policies wildfire prevention policymakers are willing to implement. From our research, we already see that the type of policy (e.g., incentives for landowners or lowering liability) plays a great role in policymakers’ view on wildfire prevention. Additionally, future research should investigate how and to what degree policymakers take into consideration their perceptions of public support or skepticism for prescribed burning and other wildfire prevention policies when they make decisions on these measures.

Endnote 1: For a list of all survey items, response options, and scale details see Table S1, see the Open Science Framework data repository where we published the study instruments and dataset (Jose et al., 2024).] You can also see a copy of the informational text—also known as vignettes—that we used in the experiment in this same repository.↩

Endnote 2: The policymaker sample includes the five county commissioners or fire chiefs who responded to our initial recruitment effort and the two people in the public sample who indicated that they were currently serving as county commissioners.↩

Acknowledgments. First, we would like to thank Dr. Klaus Fiedler, Dr. Florian Kutzner, and Dr. Linda McCaughey for organizing the International Rationality Summer Institute 2022 where our research idea was born. Second, we thank all the people who took the time and provided feedback on the research design and provided insights on the policymaking context, namely Dr. André Mata, Dr. Carissa Wonkka, Dr. Janet Yang, Dr. Francesca Colli, Dr. Valérie Pattyn, Allison Frederick, Chris Fox, and Stuart Orr.

References

-

Clark, A. S., McGranahan, D. A., Geaumont, B. A., Wonkka, C. L., Ott, J. P., & Kreuter, U. P. (2022). Barriers to prescribed fire in the US Great Plains, Part I: Systematic review of socio-ecological research. Land, 11(9), Article 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091521 ↩

-

Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils. (2022). About us. Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils. https://www.prescribedfire.net/index.php/about-us ↩

-

Melvin, M. (2018). 2018 National prescribed fire use survey report. Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils. https://www.frames.gov/catalog/57065 ↩

-

Joshi, O., Poudyal, N. C., Weir, J. R., Fuhlendorf, S. D., & Ochuodho, T. O. (2019). Determinants of perceived risk and liability concerns associated with prescribed burning in the United States. Journal of Environmental Management, 230, 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.09.089 ↩

-

Weir, J. R., Kreuter, U. P., Wonkka, C. L., Twidwell, D., Stroman, D. A., Russell, M., & Taylor, C. A. (2019). Liability and prescribed fire: Perception and reality. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 72(3), 533–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2018.11.010 ↩

-

Weir, J. R., Bauman, P., Cram, D., Kreye, J. K., Baldwin, C., Fawcett, J., Treadwell, M., Scasta, J. D., & Twidwell, D. (2020). Prescribed fire: Understanding liability, laws, and risk. Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service.https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/prescribed-fire-understanding-liability-laws-and-risk.html ↩

-

Weisshaupt, B. R., Carroll, M. S., Blatner, K. A., Robinson, W. D., & Jakes, P. J. (2005). Acceptability of smoke from prescribed forest burning in the northern inland west: a focus group approach. Journal of Forestry, 103(4), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/103.4.189 ↩

-

McCaffrey, S. (2009). Crucial factors influencing public acceptance of fuels treatments. Fire Management Today, 69(1), 9-12. ↩

-

Behrer, A. P., & Wang, S. (2023). Current benefits of wildfire smoke for yields in the US Midwest May Dissipate by 2050. Environmental Research Letters, 19, Article 084010. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad5458 ↩

-

McDaniel, T. W., Wonkka, C. L., Treadwell, M. L., & Kreuter, U. P. (2021). Factors influencing county commissioners’ decisions about burn bans in the Southern Plains, USA. Land, 10(7), Article 686. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070686 ↩

-

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480-498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480 ↩

-

Baekgaard, M., Christensen, J., Dahlmann, C. M., Mathiasen, A., & Petersen, N. B. G. (2019). The role of evidence in politics: Motivated reasoning and persuasion among politicians. British Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 1117-1140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000084 ↩

-

Christensen, J., & Moynihan, D. P. (2024). Motivated reasoning and policy information: Politicians are more resistant to debiasing interventions than the general public. Behavioural Public Policy, 8(1), 47-68. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.50 ↩

-

Bertsou, E., & Caramani, D. (2020). The technocratic challenge to democracy. Routledge. ↩

-

Siegrist, M., & Árvai, J. (2020). Risk perception: Reflections on 40 years of research. Risk Analysis, 40(S1), 2191-2206. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13599 ↩

-

Jasanoff, S. (1998). The political science of risk perception. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 59(1), 91-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0951-8320(97)00129-4 ↩

-

Nutley, S. M., Walter, I., & Davies, H. T. O. (2007). Using evidence. How research can inform public services. Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.51952/9781847422323 ↩

-

Weiss, J. A. (1979). Access to influence: Some effects of policy sector on the use of social science. American Behavioral Scientist, 22(3), 323-472. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276427902200307 ↩

-

Sjöberg, L. (2001). Political decisions and public risk perception. Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 72, 115-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0951-8320(01)00012-6 ↩

-

Brewer, P. R., & Ley, B. L. (2013). Whose science do you believe?Explaining trust in sources of scientific information about the environment. Science Communication, 35(1), 115-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547012441691 ↩

-

Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgement and Decision Making, 8(4), 407-424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500005271 ↩

-

Gerdes, R., Lammers, W., & Jose, E. (2024). Motivated reasoning and burn ban decisions by county commissioners [Study Plan]. Open Science Framework. Center for Open Science. https://osf.io/a3fcb ↩

-

Jose, E., Gerdes, R., & Lammers, W. (2024). Motivated reasoning and burn ban decisions by county commissioners [Data set and Instruments]. Open Science Framework. Center for Open Science. https://osf.io/ctg8m/ ↩

-

Rasch, G. (with Wright, B.). (1980). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1960). ↩

-

Kaiser, F. G., Byrka, K., & Hartig, T. (2010). Reviving Campbell’s paradigm for attitude research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(4), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310366452 ↩

-

Kaiser, F. G., Gerdes, R., & König, F. (2023). Supporting and expressing support for environmental policies. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 87, Article 101997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101997 ↩

-

Kolen, M. J., & Brennan, R. L. (2014). Test equating, scaling, and linking. Methods and practices. Springer. ↩

-

Wright, B. D., Linacre, J. M., Gustafson, J.-E., & Martin-Löf, P. (1994). Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 8(3), Article 370. Retrieved from https://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt83b.htm ↩

-

American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code ↩

-

Whitehead, J. C. (1991). Environmental interest group behavior and self-selection bias in contingent valuation mail surveys. Growth and Change, 22(1), 10-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2257.1991.tb00538.x ↩

-

Gärling, T., & Loukopoulos, P. (2007). Effectiveness, public acceptance, and political feasibility of coercive measures for reducing car traffic. In T. Gärling & L. Steg (Eds.), Threats from car traffic to the quality of urban life: Problems, causes, and solutions (pp. 313-324). Elsevier. ↩

-

Allport, F. H. (1924). Social psychology. Houghton-Mifflin. ↩

-

Katz, D., and Allport, F. H. (1931).Student attitudes: A report of the Syracuse University research study. Craftsmen Press. ↩

-

Miller, D. T. (2023). A century of pluralistic ignorance: what we learned about its origins, forms, and consequences. Frontiers in Social Psychology, 1, Article 1260896. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2023.1260896 ↩

-

Kaiser, F. G., Merten, M., & Wetzel, E. (2018). How do we know we are measuring environmental attitude? Specific objectivity as the formal validation criterion for measures of latent attributes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 55, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.01.003 ↩

Jose, E., Lammers, W., & Gerdes, R. (2025). Support for Prescribed Burning in Midwestern States: Results From an Online Experiment. (Natural Hazards Center Weather Ready Research Report Series, Report 15). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/support-for-prescribed-burning-in-midwestern-states