Transit Agencies and Wildfire Evacuation

Case Study of the 2021 Caldor Fire

Publication Date: 2024

Abstract

The 2021 Caldor Fire necessitated the unprecedented evacuation of over 30,000 people from the Lake Tahoe basin. The greater Lake Tahoe area is comprised of a series of communities along a single highway between steep, forested mountains and the largest alpine lake in North America. Despite being an international tourist destination, spanning both Northern California and Nevada, the jurisdictions in Tahoe are relatively small, with planning and transportation agencies with limited capacity. The topography and relatively rural nature of the area results in constrained and challenging evacuation routes. During the Caldor Fire, the Tahoe Transportation District—the regional government agency responsible for public transit—played a significant role in evacuating people, including people with disabilities and the unhoused residents of the area. Interviews with staff revealed that the agency was not formally included in the emergency response planning and operations during the early days of the fire; conditions that resulted in frustration, confusion, and delays. Prior to the fire, neither the transportation agency nor local and regional emergency management offices had formal plans for transit or paratransit evacuation. These challenges notwithstanding, the Tahoe Transportation District demonstrated several strengths during the evacuation, including the staff’s strong shared commitment that no one be left behind. This case study adds to existing research showing that transit, and transportation agencies more broadly, must be included in emergency preparedness and evacuation plans, especially for vulnerable populations, such as older adults, people with disabilities, and the unhoused. There are few research studies of transit evacuation, particularly in rural areas in the United States. This study sought to contribute to this knowledge area and highlight the need for research on safe and effective evacuation beyond relying on private automobiles. It will be of interest to government agencies, emergency managers, transportation providers, and anyone dedicated to inclusive, safe, and effective disaster evacuation.

Introduction

During the 2021 Caldor Fire in northern California, the Tahoe Transportation District (TTD)— the local transit Endnote 1 and paratransit Endnote 2 agency in the Lake Tahoe Basin—safely evacuated over 1,800 bus riders, including many local people experiencing homelessness and nearly 500 people with disabilities. Overall, more than 30,000 people around the lake and 50,000 people total evacuated during August and September 2021. Lake Tahoe is an international tourist destination, a series of towns and communities arrayed along a single corridor between steep, forested mountains of the Sierra Nevada mountains and the lake. The roadway network already provides limited options in and out of the basin, and the encroachment of the fire from the south resulted in road closures that forced evacuations from the most populated areas of South Lake Tahoe and Stateline, Nevada to head north and east out of the basin into Nevada. As local officials issued evacuation warnings and then mandatory evacuation orders starting from the south end of the lake northward, the majority of people evacuated via the Highway 50 corridor along the east side of Lake Tahoe. People evacuating in car were stuck for hours along the road, resulting in frustration, stress, and fear that received national and international attention in the media (Atagi, 20211; Canon & Anguiano, 20212; R. W. Miller et al., 20213). Not all people could evacuate by private automobile, however, whether they are carless by choice or circumstance.

The TTD provides regular transit and paratransit on the south and east side of the lake, making 20,000 to 25,000 trips per month on average (Tahoe Transportation District [TTD], 20214). During the Caldor Fire, TTD provided special routes to take people to emergency shelters and drop-off zones out of the evacuation zones. The agency also assisted their existing paratransit riders with evacuation and coordinated with local groups to assist in the evacuation of local unhoused residents.

The purpose of this study was to explore the role that transit played in the Caldor Fire evacuation and what lessons the transportation agency staff learned from the experience. To date, there are few research studies of transit evacuation, particularly in rural areas in the United States. This study sought to fill this gap in knowledge and highlight the need for additional policies and planning to implement safe and effective evacuation beyond private automobiles. Using a research case study approach that included interviews with staff members and document review, I collected lessons learned, analyzed themes, and developed policy and research recommendations.

Literature Review

The role of public transportation in disasters became of increased interest to both researchers and practitioners following the successes and failures of evacuation during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 (Renne et al., 20095). Despite this, there remain significant research and policy gaps regarding the challenges and opportunities for “evacuating the carless” (Renne, 20186). In particular, whether and how transit is integrated into larger emergency management and response systems is an understudied topic, including planning for the specific evacuation needs of transit-dependent, disabled, and unhoused people (Renne &Mayorga, 20227) . A review of the literature revealed that the specific challenges and opportunities of wildfire evacuation in rural locations among communities in the wildland urban interface is even less explored. The following sections briefly review existing literature on these topics to explain the need and potential benefit of this study.

The Current State of Evacuation Planning by Transportation Agencies

Emergency preparedness among state and local transportation agencies in the United States prioritizes traffic control, response teams, and situational awareness (Kim et al., 20198). The majority of existing research on evacuation is quantitative and focuses on traffic disruptions in evacuation (Donovan & Work, 20179; Kim et al., 202210; Kim et al., 201911). There is a need for more qualitative research that provides nuanced understanding of the planning and operations within transportation agencies, including both formal processes and organizational culture related to evacuation planning. Training of emergency managers, police, and transportation agencies is key to improve evacuation preparedness (Kim et al., 2022), but there is not existing literature on how many transportation professionals participate in training specific to evacuation or the effect of emergency drills in increasing transportation agency participation in emergency planning and response.

Transit-Based Disaster Evacuation

The failures of evacuation during Hurricane Katrina resulted in increased awareness among both researchers and practitioners about the need for improved transit-inclusive evacuation planning and policy (Renne & Mayorga, 2022). Despite several large federal reports written post-Katrina to provide guidance in transit evacuation, a 2022 review of evacuation plans in the 50 largest urban areas found only “marginal” improvements in the creation and quality of plans and many urban areas with no plan at all (Renne & Mayorga, 2022). This persists despite resources like the Federal Transit Administration’s Public Transportation Agency Safety Plan Technical Assistance Center, which provides training and voluntary reviews of draft agency safety plans.

Resources aimed specifically at small and rural transit agencies are sparse. While there are some e-learning resources available for rural transit providers provided by groups like the National Rural Transit Assistance Program (National RTAP, n.d.12), most emergency management, evacuation, and transit-focused guidance publications (e.g. (White et al., 200813) focus on large urban areas with extensive transit systems. The one research report focused on emergency planning for rural and small urban transit agencies we were able to locate was published in 2000 and focused specifically on Texas (Higgins et al., 200014). We also located a handbook on paratransit emergency preparedness and operations produced through the Transit Cooperative Research Program (Boyd et al., 201315). Due to the lack of existing plans amongst agencies that might benefit from published guidance, it is unclear whether transportation professionals are aware of these resources or how widely they are used.

While some of the existing guidance applies to transportation agencies at any scale, agencies in small and rural areas face unique challenges. Transportation networks cross jurisdictional boundaries (Renne et al., 2009), but local agencies in rural and/or smaller jurisdictions often have limited capacity to coordinate with neighboring jurisdictions (Cova et al., 201316). Even in places with public transportation, most evacuation plans only include evacuation by private automobile (Cirianni et al., 201417), e.g., routes and traffic signal timing for private car-based operations. Evacuation clearance times are often conceptualized around residents with cars (Zhang et al., 201918), and authorities typically focus on issues of personal household evacuation via automobile (Zhao & Wong, 202119). This approach risks excluding many vulnerable people from evacuation plans and operations.

Vulnerable Groups During Evacuation

This report—adopting an approach based in the research literature—uses the term “vulnerable populations” to refer to groups of people who may have difficulty evacuating due to limited access to transportation. Renne and Mayorga (2022), for example, define the following groups as vulnerable during evacuation:

Individuals who cannot drive or who do not have access to a vehicle. This includes, but is not limited to low-income, elderly, young, individuals with specific needs, and transient populations (i.e.., tourists that may not have a car while on vacation)—and who may require transportation and other evacuation assistance to be safely and effectively evacuated before, during or immediately following a disaster. (p. 2).

Other terms used for vulnerable groups by emergency management officials, advocates, and affected populations include: “people with disabilities and other with access and functional needs” (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 202420); “disproportionately affected individuals”; and “historically disenfranchised communities”, among others. Wherever possible, terms should reflect the terms used by that particular group, and should be specific to the sub-groups and not treat them as homogenous, while acknowledging the intersectionality of identities that result in compounding inequities (Williams et al., 202221).

Research shows that in order to meet the needs of vulnerable groups during disasters, these groups must be included early and often in planning and disaster risk management activities. If not, they are “rendered invisible” in official policies (United Nations, n.d.22). Even prior to Katrina, researchers identified the need to plan for evacuation of “temporarily carless and the permanently carless” people who may have different needs in evacuation (Renne et al., 2009). These vulnerable people do not belong to a homogenous group, but rather include individuals who cannot or chose not to drive due to age, physical or cognitive ability, poverty, undocumented status, lifestyle choice, and/or medical conditions (Rhodes, 201723; United Nations, n.d.). People with disabilities in rural areas, who rely on small transit agencies for evacuation may face additional challenges related to geography and technology access that emphasize the need for emergency plans that address specific community needs (Asfaw et al., 201924).

Wildfire Evacuation

Relative to hurricane evacuation, there is limited research specifically into wildfire evacuation. While this is understandable since severe storms and tropical cyclones often represent the most costly and deadly of disasters in the United States (Gusner & Masterson, 202325), wildfires represent a significant danger to life and property, with over 4.5 million U.S. households at a high risk of wildfire (Gusner & Masterson, 2023). Like with other disasters, wildfires may be “no notice”, meaning they occur unexpectedly or with minimal warning, limiting activation of formal emergency systems and thus alerts and protocols to evacuate people, particularly populations at risk due to limited mobility, age, disability, cognitive differences, or other characteristics (Federal Highway Administration, n.d.-a26). The 2023 wildfires that devastated Lahaina are an example of a no-notice wildfire.

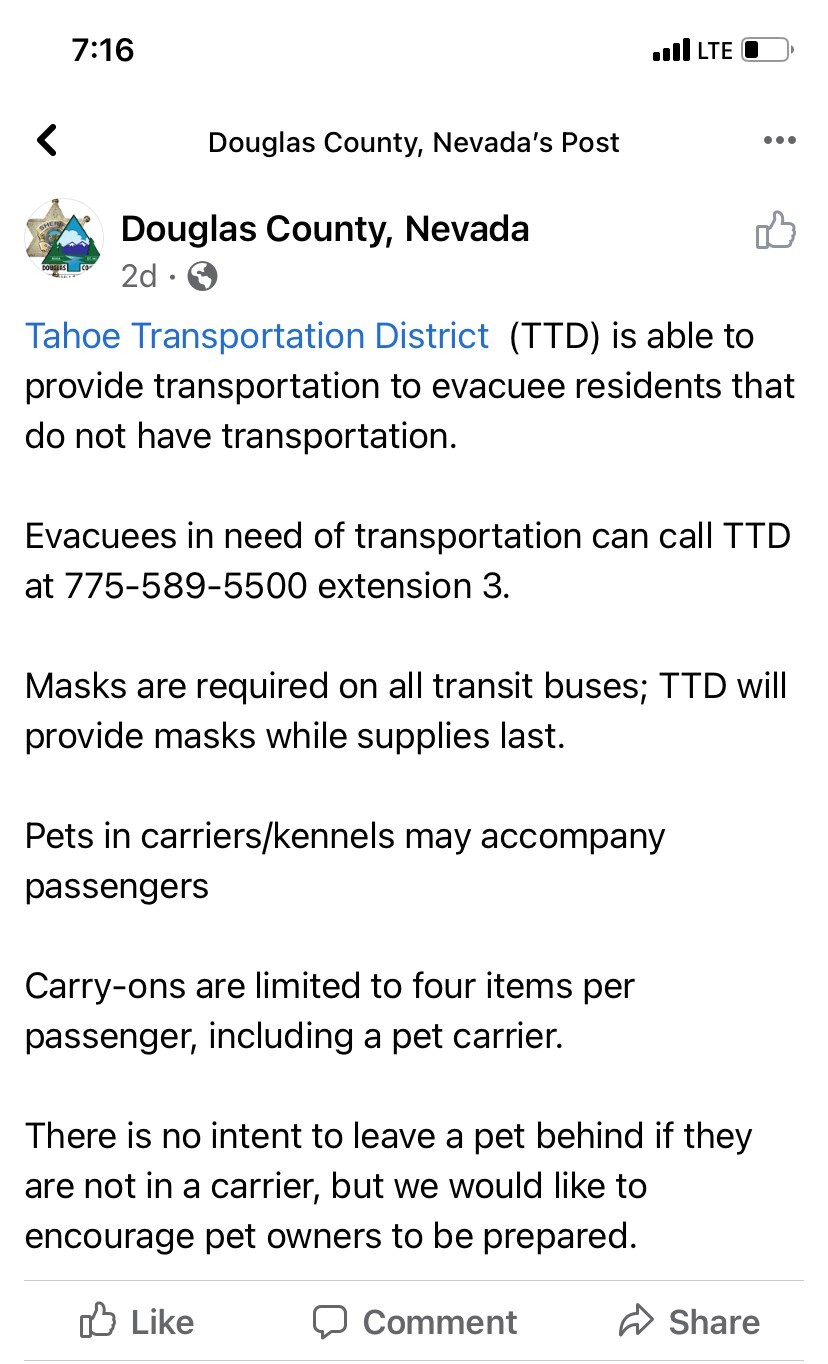

Even with advance notice, evacuation choices are not always simple, particularly for the populations referenced above. While individuals with private automobiles may be able to evacuate at any point when alerted to a potential threat or imminent evacuation warnings and orders, transit- and paratransit-riders may be forced to rely on transit service providers activating special operations. These operations may include additional routes or increased frequencies, routes that go directly to emergency shelters, and/or changes in policy to support the evacuation of people with belongings and pets (White et al., 2008).

In summary, international and U.S. federal guidance on disaster planning and transit, and non-profit and advocacy groups publications on the needs and best practices of inclusive disaster planning exist. There remain gaps, however, in the research literature in particular about planning related to the overlapping challenges of transit- and paratransit-based wildfire evacuation, particularly in a rural area. The role of local or regional transportation agencies and their employees in evacuation planning and response is virtually unexplored. This study sought to address this knowledge gap through a case study of a transportation agency that provided transit- and paratransit-evacuation during a large and challenging wildfire event, with the goal of telling the successes of the evacuation, sharing lessons learned and potential policy and practice implications, and highlighting the need for transportation agencies to consider themselves, and be considered by other agencies, as playing a vital role in emergency management systems.

Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to document how the TTD was involved in planning for and evacuating residents via public transportation during a wildfire emergency, with a special focus on how the transit agency responded to the needs of people with disabilities and unhoused citizens without vehicles. Several specific questions guided this study:

- How was transit included in plans for wildfire evacuation in the Tahoe area? Did plans explicitly include vulnerable groups that may rely on transit or paratransit services, such as people with disabilities, non-car households, older adults, and unhoused people?

- What challenges did the local transportation agency face during the evacuation of transit- and paratransit-dependent people during this wildfire? What were the strengths and success of the agency’s and employees’ evacuation of transit- and paratransit-dependent residents?

- How can those challenges and successes translate into lessons learned for planning for future evacuations of transit- and paratransit-dependent people?

Research Design

The study used a research case study approach, which examines the “how” and “why” of a contemporary event, including the operational processes over time and the interaction of the decision-making processes within their real-world context (Yin, 201827). As the principal investigator, I conducted interviews with the staff of the TTD who were centrally involved in the fire response, resulting in approximately five hours of interviews. I also reviewed documents to understand what evacuation planning, policies, and procedures were in place for transporting transit-dependent people, including those with disabilities, car-free households, and unhoused residents of the area. This section describes the research methods in more detail.

Study Site and Access

Lake Tahoe

Lake Tahoe is a freshwater lake located on the border of California and Nevada in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in the northern part of both states. It is an international tourist destination, with tourism making up most of the local economy (Federal Highway Administration, n.d.-b28) . The permanent population of the Lake Tahoe Basin is approximately 56,000 people but it receives over 15 million visitors per year, resulting in over 300,000 people in the area on peak summer and winter days (Anguiano, 202329). The COVID-19 pandemic worsened the housing crisis in the region, as over 3,000 people moved to the area in 2020 (Anguiano, 2023). The increase in new local residents and tourists adds to local road congestion even under normal operations, and newer residents or visitors may be less familiar with local emergency plans or where to get information during an evacuation event. These pressures of growth and tourism are compounded by the topography and limited road network, essentially a 72-mile “ring road” around the lake with limited major roadways leading to the large cities of Sacramento to the west and Reno and Carson City to the east (Federal Highway Administration, n.d.-b).

The Caldor Fire

The Caldor Fire started at approximately 7:00 p.m. on August 14, 2021, near the community of Grizzly Flats, California, and was active for 68 days (CalFire, 202130). It was one of several “mega fires”—fires that burn over 100,000 acres—in 2021 and eventually burned over 220,000 acres, destroying 1,005 structures and injuring 21 fire personnel and civilians (Serrin, 202231). It was only the second fire in recorded history to cross over the Sierra Nevada mountains (Sion et al., 202332), just after the Dixie Fire did so in the same fire season (H. Miller, 202133). During the fire, county and local emergency officials issued several evacuation warnings and orders and over 30,000 people evacuated from the Lake Tahoe Basin (CalFire, 2021). The Governors of both California and Nevada issued Declarations of Emergency (State of California, 202134; State of Nevada, 202135) and subsequently President Biden declared the Caldor Fire as a Federal Disaster area, the first in El Dorado County history (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 202136; US Forest Service, n.d.37).

During the height of the evacuation, people waited for hours on Highway 50, the primary route out of the basin. Headlines in the national news included “Wildfire Evacuees Fill Lake Tahoe Roads in Rush to Flee” (Metz & Har, 202138) and “Roads packed after South Lake Tahoe ordered to evacuate” (R. W. Miller et al., 2021). The Guardian trumpeted “Chaos as Caldor fire forces unprecedented evacuation of Tahoe tourist town … fleeing residents clog roads” (Canon & Anguiano, 2021). One iconic photo captured a 74-old man playing his violin in an attempt to calm himself and others drivers stuck in the traffic “standstill” (Atagi, 2021).

Tahoe Transportation District

TTD was created as a special regional transportation district to facilitate transportation planning, implementation, and operations across two states, five counties, one city, and multiple unincorporated areas in the Tahoe Basin (TTD, n.d.-a39). The agency is overseen by a fourteen-member Board of Directors comprised of city, county, and state officials and representatives from transportation associations (TTD, n.d.-b40). The agency has an administrative office located in Stateline, Nevada, and a maintenance and operations facility, two transit centers and one mobility hub, all located in South Lake Tahoe, California. The full agency staff includes approximately sixty-five full- and part-time transit planners and analysists, bus drivers, dispatchers, and maintenance and fleet technicians (TTD, 202441).

TTD provides bus transit to both residents and visitors through fixed-route and commuter bus system and specialty shuttles to local destinations. The agency currently provides fare-free transit to all users through grants from the Federal Transit Administration. The agency began direct provision of paratransit in 2011. Using 2020 Census data, the agency considers approximately 21,000 local residents to be potentially transit dependent due to age, disability, poverty, and/or lack of a vehicle in the household (TTD, 2024). In the months prior to the fire, when many medically-vulnerable residents were sheltering in place due to the ongoing COVID pandemic, the agency provided between 600 and 1,000 paratransit trips per month (TTD, 2021).

Agency Access

I was invited by two staff at TTD to discuss the potential for research collaborations unrelated to wildfire or evacuation. This invitation to support the agency’s long-term knowledge needs with research grew out of conversations with one staff member, with whom I have been personal friends for two decades. When we met to discuss those research ideas, the conversation naturally turned to the Caldor Fire, one of the most significant events to affect the Tahoe area in recent memory. That conversation revealed the depth of the “untold story” of the Caldor Fire transit and paratransit evacuation .

It is important to acknowledge the potential role of my existing personal relationship with one of the participants and that my immediate family was personally affected in the Caldor Fire evacuation. While these gave me both motivation and access to participants for this study, it was important to stay cognizant of my positionality and how it might influence my research design, interviews, and interpretation of the data. I used self-reflection through the analytic memo process (Saldaña, 202342). My goal was to be aware of what personal aspects I brought to the work while acknowledging that removing those aspects is neither possible nor necessarily desirable (Brown, n.d.43) .

Interviews

I interviewed five TTD staff members who were centrally involved in the fire response. Interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and I conducted two in person and three via video chat as requested by the participants. I sent several interview requests to additional employees involved in the evacuation communication and operations but was unable to obtain interviews with these staff. This likely reflects challenges of employee turnover, small agency capacity, and broader issues of participation and capacity. The limitations section of the report addresses the small size of the interview sample. Interviews with the TTD staff provided an opportunity for rich, nuanced insight into the pre-, during, and post-fire planning and operations of transit evacuations of the Tahoe Basin. While physical planning documents and adopted policies describe the official structures in place, the experiences of those directly involved in some or all the evacuation provided additional context and helped illuminate power dynamics, politics, or unofficial but crucial factors that influenced the successes and challenges of the event.

Participant Consent and Other Details

I provided participants with an electronic version of the consent script (Appendix A) via email prior to their interview and provided a physical or electronic copy again at the time of the interview. I requested verbal consent for interviews to be audio recorded and stated that audio recordings were for internal use only and would not be shared outside the research team. All participants agreed to be recorded and participate in the interviews.

Interview Questions

Each interview followed a semi-structured approach, guided by the interview guide but with enough flexibility to allow participants to steer the conversation to important related topics and broaden the discussion beyond the pre-planned questions. The following list outlines the questions used for the interviews: Pre-event planning and experiences with disaster response as an agency or employee; event experiences with mobilization, communication, personal evacuation, interjurisdictional coordination, challenges and successes; and post-event return to normal operations, debriefs, planning, and lessons learned. The full interview guide is provided in Appendix B.

I submitted a human subjects research protocol to the Texas A&M University Human Research Protection Program, which determined on April 25, 2023, that this research met the criteria for Exemption in accordance with 45 CFR 46.104.

While the subject of the study is the evacuation related to their official professional roles, most people in these agencies were personally affected by the wildfire evacuation. Discussing these events, although now nearly two years post-event, could evoke stressful situations, either professional or personal. The interview questions were intended to minimize this potential, but participants were encouraged to take a break if they needed to and were reminded that they could stop at any time. No participants expressed concerns, took breaks, or declined to answer any questions.

Interview Data Analysis Procedures

I audio recorded all interviews with a phone application (for in-person interviews) or Zoom (for video interviews). Transcripts were generated using NVivo’s transcription software or Zoom’s transcription function and appended to their relevant audio files. I simultaneously read and listened to the transcripts and interviews to correct transcription errors and pull out important direct quotes for use in this report.

To explore the overarching themes in the interviews, I used a combination of two “first cycle coding methods”, initial coding and concept coding (Saldaña, 2023). As I read the transcripts, I made notes in “analytic memos”, to document major themes, reflect on my process and watch out for introducing biases based on a priori hypotheses, and to engage more deeply with the data (Saldaña, 2023). Using this iterative process, I developed concept codes that became the sub-headings in the Findings section.

To illustrate the themes in the participants’ own words, I extracted quotes from the transcripts, which I wove into the Findings section. Quotes have been edited to remove filler words and phrases (e.g., “um”, “I mean”) where it does not change the meaning of the quote or the underlying sentiment.

Document Review

Relevant materials to the transit- and paratransit evacuation of people during the Caldor Fire included: (a) existing plans and procedures before the fire; (b) communications and alerts during the evacuation; (c) any after action reports, plans, policies, or procedures publicly available by August 2023 in response to the 2021 event. We collected documents from any local, regional, or state agency that might reference evacuation, wildfire, and/or emergency planning for transit-dependent and vulnerable communities in the Tahoe region, including the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, the Tahoe Resource Conservation District, the Tahoe Fires and Fuel Team, and more (full list in Appendix C). Documents were collected through internet searches, requests to agency staff, through university library searches, and via news articles and press releases by agencies. We then uploaded the documents into citation management software Zotero and qualitative analysis software NVivo and categorized them by type. Documents were then keyword searched for “wildfire”, “fire”, and “evacuation” in the first round, and then “transportation planning”, “transit”, “paratransit”, “disabled/disability”, and “homeless/unhoused/houseless” in the second round.

Findings

In this section , I use subheadings that attempt to capture the overarching lesson or theme related to that topic and use direct quotes along with my interpretation and analysis. The first sub-sections focus on the challenges related to pre-planning and response, and the latter sections highlight successes and strengths. I discuss implications for policy and practice in the later Conclusion section. Overall, specific themes revealed during the analysis include: limited previous experience and a lack of formal existing plans related to transit and paratransit evacuation; omission from formal emergency response and lack of inclusion of vulnerable populations in local emergency planning and response; the challenges of negative perceptions of transit and a lack of vision for transit’s potential role in large evacuations; the importance of personal relationships for mutual aid; and positive outcomes due to personal relationships and employees at all levels going “above and beyond”. Each theme is discussed in more detail below.

Challenges of Transit and Paratransit Evacuation in Tahoe Wildfire Planning and Response

Lack of Existing Plans for Transit Evacuation

Prior to Caldor, the agency’s disaster response experiences had mostly been “ad hoc” and not a function of formal emergency plans or mutual aid agreements. As one interviewee explained, on previous occasions they had been asked to send buses to move guests staying at local ski resorts which had lost power or been damaged by building fires: “We get a call [from law enforcement], ‘please help.’ And then we send a driver in a bus.” Participants reported a lack of formal inter-agency agreements or protocols, and the document review confirmed that TTD neither had its own formal plan for evacuation during a wildfire nor did local or regional emergency plans specifically reference the agency or transit evacuation.

Interviewees also described challenges due to unclear incident response command structures prior to the Caldor Fire. As one interviewee said:

When there’s an emergency event, who takes the leadership role? [It] came into place during Caldor because it was a true emergency, but I think leading up to that, there was … a lot of jurisdictional [interviewee motioned people pointing in opposing directions].

Another participant noted that the regional aspect of transit requires “crossing jurisdictional boundaries” but that transit professionals are not familiar with or trained in incident command systems: “The whole emergency response stuff is not our bailiwick. So, there’s all of that protocol and language and things like that. That’s not what transit agencies deal with.” This appears to be a limitation for both transportation agencies and the larger emergency management ecosystem, with a lack of resources and training aimed at transportation agencies and a lack of inclusion of transit agencies, in particular, in both formal and informal agreements.

This was confirmed through review of documents related to hazard mitigation and community wildfire preparedness for the Tahoe area. Few documents even discuss interagency or transit planning for future evacuations in Tahoe, and there is limited availability of existing documents on public sites. One employee was actively involved in trying to increase disaster planning for the agency, but reported working on it, often on their personal time, without support from the agency board:

I would bring things forward. They knew I was doing these things, but it was very much [not a part of our official work plan] … we didn’t have really any budget for it, I honestly would just do it. I did a lot of things on my own time, because I thought they were important. But they didn’t budget for it.

A review of the agency’s existing plans and agenda packets in the two years prior to the fire confirmed that there was limited or no formal evacuation planning.

Lack of Planning and Tools for the Evacuation of Paratransit Users and Unhoused People

It is important to recognize that transit and paratransit are not just different transportation modes equivalent to private automobiles, but rather represent programs, vehicles, and operations that serve heterogenous populations with varied needs related to physical mobility, cognitive abilities, specialized equipment, health conditions, and more. Thus, specific plans and operational tools are needed.

In the Caldor fire evacuation, the lack of a reliable, real-time communication system with paratransit riders, in particular, resulted in inefficiencies, frustrations, and concerns about missing anyone who might need assistance. As put by one interviewee, “We were going on a wild goose chase trying to pick people up. How long does the driver wait before he goes on to the next call? So that piece could definitely have been improved.” This was echoed by another interviewee, who said “By the time we got to those homes, most of those folks had already found somebody else and were gone. That type of chaotic situation is pretty hard to navigate through in a timely way.”

The lack of good communication and tracking procedures, along with the sheer size of the need, resulted in a need for adapting and innovating on the fly. Several interviewees explained that the agency did not have software to coordinate emergency alerts, track evacuation communications, or interface between the transit operators and law enforcement. One participant discussed the attempt to rapidly develop a tool to track potential rider locations and where drivers should be sent for pick-ups:

It was like an Excel spreadsheet that had a map component that I would say one of their IT guys like put it together on the fly. And we were like ‘this is kind of wonky. We’re going to do the best we can.’ I think that could have been hugely helpful just for all of us to have it ahead of time.

Disaster registries may be helpful but also limited for assisting in locating and communicating with riders (Rhodes, 2017), particularly if the transportation agency does not have an intuitive, reliable software to connect registry information with real-time information like road closures, evacuation order zones, and communication from riders (e.g., whether a ride is needed). Another extremely vulnerable population in disasters are unhoused people. During the Caldor evacuations, the transportation agency was a key provider of evacuations for unhoused people in the area, despite a lack of advanced planning around this issue. There was a sense among interviewees that once evacuations started, most emergency officials did not consider the unhoused population their “responsibility” and were focused on housed residents and tourists. One person said that “[unhoused people] weren’t really being thought about all that much. It was very focused on ‘we need to get our residents out [via cars].’ It’s like, hey, they’re residents, too.” Several interviewees noted the importance of the local organization Tahoe Coalition for the Homeless, who helped 60 people evacuate to shelters or motels (Angst & Kelliher, 202144).

Omission From the Emergency Management Process During the Response

One key issue that surfaced in every interview was the perception that the agency was not involved during the initial emergency response in the formal incident command structures and the Emergency Operations Center (EOC). Put bluntly by one participant,

We really had to elbow our way in [to the EOC]. One day [we] just went to [the meeting without being invited]. We’re like, where are you guys [meeting]? Okay, we’ll show up in an hour. And they were definitely surprised to see us.

This lack of inclusion is reflected in situation reports during the fire. The Incident Updates throughout the fire include a list of more than sixty (60) Cooperating Agencies, including government agencies, utility companies, school districts, and tribal governments, but TTD is not included on the list (CalFire, 2021).

Participants noted how important it is to be part of the formal and informal conversations that occur at the EOC. For example, there may be information announcements that are only shared at official daily briefings, early discussions about anticipated scenarios and responses, and opportunities for serendipitous inter-jurisdictional coordination and general relationship-building. One participant referred to this as “ambient information”, saying:

I don’t necessarily think we would have been forgotten. Of course not, because we had the resources that they needed. But maybe we could have been brought in a couple calls earlier or [been included in the EOC]. … there’s a lot of that ambient information that’s being shared that might not be shared [elsewhere].

Once they were part of the EOC, however, participants felt like many emergency professionals had an epiphany about the need to include the transit agency:

[Local police and fire departments] and all those [did not think about us]. I think it really set us back by not being invited to the table … [but] once we were there it was like, ‘Oh, yeah, this was a great idea’ and the guys that are sitting at the table realize that ‘hey, you’ve got these big busses that can move a lot of people.’

It is possible that earlier attendance at daily briefings might have avoided some of the technological or operational challenges that occurred or provided earlier opportunities for evacuation to carless residents and tourists. For example, earlier knowledge of the evacuation phasing may have resulted in the agency switching to evacuation operations earlier, giving residents the chance to get to shelters or out of the area sooner. The interviewees were unsure who should bear responsibility for making sure the transportation agency is included in the EOC from day one. Emergency managers should also be consulted to gather more input. But this study shows that the inclusion of transportation agency officials in EOCs could provide significant benefits.

Demands on Bus drivers and On-Board Challenges

Bus drivers are essential workers at the heart of any transit provider. Even during normal operations, they not only drive the buses but interact with riders, aid users of assistive devices like wheelchairs, and enforce rules about what people can and can’t do or bring on board. During unusual and stressful situations like the COVID pandemic and the Caldor wildfire, these roles can put a large burden on drivers. During evacuation, vehicle design, capacity, and agency rules about allowable items onboard all may come into conflict with people’s evacuation needs and desires. For example, assistive devices (e.g., wheelchairs, walkers) take up room and specialized areas with flip-up seats and wheelchair attachments may be limited. People evacuating may try to bring on many more possessions, filling up capacity that could be used for more riders. Most bus systems have limits about bringing non-service animals on board, but having to leave pets behind can significantly affect people’s decision whether to evacuate (Chadwin, 201745).

To support people’s evacuation and limit the amount of time that drivers had to spend trying to enforce rules, the agency sought to be “very liberal” about what people could bring onboard during the evacuation. Several interviewees noted that this created challenges for drivers:

We told [the drivers] ‘You guys have to pick your battles at this point.’ . . . Some people had limited ambulatory abilities, all sorts of different circumstances . . . usually we have this really staunch carry-on policy and pet policy, and it’s like everything’s out the window.

One interviewee highlighted how evacuating people experiencing mental illness during a stressful emergency event put an additional strain on drivers. “It poses a whole new challenge with trying to get a driver who’s comfortable at that point . . . [they are] not trained to handle very specific cases of mental illness and trauma at the same time.” This example shows that transit agencies should consider providing drivers with additional support staff and training that could relieve their burden and better support riders in duress. Opportunities to partner with local organizations and health agencies that can provide this assistance should be further explored.

Successes and Strengths of the Transportation Agency’s Transit and Paratransit Evacuation

Awareness Among Transit Agency Staff About Potential Role in Response

When discussing emergency planning, all interviewees reported that they were personally aware—as was the agency more broadly—that wildfire conditions could develop in the region and require rapid evacuation, as had occurred during the recent devastating wildfire that destroyed the community of Paradise, CA. One interviewee noted the awareness among employees that the agency would be needed in the case of a large evacuation and would be called upon by emergency management and response officials:

We always kind of figured it would be us if something happened down here. So, we had given some forethought and had some awareness because of Paradise and our work with the fire districts . . . [if there is] some kind of catastrophe. We’re going to get called up.

As discussed in the challenges section, the agency was not involved in the initial meetings at the EOC, but staff made the explicit point that TTD management saw the need to be involved, as in the words of one interviewee: “I give [our agency leadership] credit for making sure that we had a seat at that table.”

"Above and Beyond” Commitment by Staff

All the interviewees emphasized that TTD staff at all levels—from office staff to bus operators to maintenance workers—made significant efforts to safely evacuate people via transit and paratransit. One participant said, “I was so proud of our bus drivers [who would say to evacuees]: ‘like just get on!’ Yeah, proud [of the] bus drivers, just being heroes.” Another participant repeatedly praised the efforts by bus operators, many of whom were themselves displaced by the fire: “Our crews were very responsive, did a great job . . . we were all working together in getting these things done.” One interview framed this as a general reflection on how transit employees approach their work:

I don’t really look at it as, you know, this was a heroic thing. We did our job, and that job is to move people and we moved people. We did as best we could. We had a lot of people that stayed and put in all, you know, constant hours for it.

The Importance of Relationships With Residents and Partner Organizations

Organizations that serve people with disabilities are well aware of their vulnerabilities in emergency situations that require evacuation. One participant discussed how the agency works with a local group that had long been discussing wildfire concerns and the need for better ways of contacting people with disabilities in an emergency. The interviewee noted the importance of the TTD maintaining a consistent relationship and building trust with partner organizations and individuals in the community, saying “our paratransit folks were calling us throughout because we’re their transportation every day . . . they were calling sometimes just for that connection to normalcy.”

Employees noted the importance of transit agency employees’ existing relationships with local social services and nonprofit organizations serving the unhoused population. Unhoused people often lack trust with law enforcement, but these service organizations helped overcome that challenge by getting the word out about the need to evacuate and how to use transit to do so. In addition to information shared with local partners and via word of mouth among the social networks, signs were used to tell people where to wait and when buses would depart for the evacuee shelters.

Post-Caldor Challenges

A key goal of this study was to understand what the TTD and other local emergency officials did after the evacuation to improve coordination and planning for future events. When asked about this, one interviewee said, bluntly, “There’s been NOTHING.” Another participant echoed this sentiment: “I would say we didn’t come together [after the fire].” A third staffer noted that TTD staff are aware that they should be involved in disaster planning and preparedness, but neither local authorities and emergency officials responsible for these activities have included them nor has the agency taken an official role in local planning:

If it is, we’re still not part of it . . . I don’t even have a copy of each of those local jurisdictions’ plans . . . ‘Where are you guys on your planning? And what would we do different together out of any of this?’ We haven’t even really had that kind of debrief conversations with each other.

When asked why they thought transit continued to be left out of evacuation planning, particularly in a proactive way, the interviewee said most people – both emergency professionals and citizens – think “that’s for those ‘transit people.’ And it just never clicks that [transit] would be useful for the general public to move large amounts of people.” The interviewee’s latter argument is in regard to the idea that transit could be used to evacuate larger numbers of people quickly and reduce congestion due to private automobile evacuation. The interviewees sensed, however, that neither citizens nor local emergency professionals felt it was necessary to prioritize transit for evacuating existing riders or for the general public. Previous research backs up the interviewees’ perception that transit is held in low esteem. Negative attitudes, both explicit and subconscious, about buses and bus riders and the subsequent effect on actual bus use is well-documented (Moody et al., 201646). Additionally, the concept of “windshield bias” dominates professional and citizen viewpoints (Maus, 202347; Walker, 200548; Walker et al., 202249).

One interviewee reported seeing the concrete effects of this bias at a local public meeting where additional transit routes were being considered and an attendee brought up evacuation as a reason not to add transit even for regular service:

[The person at the meeting said:] We don’t need public transit here. What if we need to evacuate? We need our roads clear.’ [I thought to myself:] ‘Okay. You’re not thinking very deeply about this. You know how many people can fit on a bus versus how many people can fit in a car. And if you end up burning, that is going to be why, because there’s too many people trying to get out on narrow roads and you’re not taking the bus thinking that is for other people in that situation. You’re the other people.’

An additional factor emerged post-fire that made it difficult to improve transit’s participation in emergency planning: The high rate of employee turnover, particularly in management. The TTD relied heavily on internal champions, but this can fall short when employees leave. One interviewee explained how an employee leaving the agency affected ongoing planning efforts: “The problem was not having a champion after [they] left. While both homeland security and the OES [State of California Office of Emergency Services] were supportive of [working with the TTD], and even bringing money to the basin for it, once [they] left, it struggled.”

Other factors contributed to the lack of significant planning post-event. Coordinating large-scale interagency planning processes takes time, and COVID-19 challenges were on-going after the fire and repopulation in late 2021. Then record snow in winter 2022 brought a different type of slow-moving disaster to the area, resulting in evacuations, school and business closures, and massive transportation challenges of a different sort.

When asked about the increased awareness about evacuating non-drivers that arose from Katrina and federal guidance on needing to include transit authorities in evacuation planning (Renne & Mayorga, 2022), an interviewee said, wryly, “That’s interesting that you said, ‘we learned that with Katrina.’ Well, I would say [that] we didn’t learn it right here [in the Tahoe area]. We continue to rediscover it through every single disaster.”

A review of the agency’s quarterly reports for the first half of 2022 (in the months immediately following the fire) showed that there was no discussion among the Caldor-related agenda items related to future evacuation planning efforts. There is no public-facing “after action report” that would help demonstrate any direct line from the Caldor evacuation to ongoing planning efforts.

Conclusions

Many small and/or rural communities in the United States have only one or two main roads that lead in or out, whether due to topography or local land uses like agriculture. These limited road networks can make evacuation during wildfires or other emergencies very difficult and even deadly to people stuck in vehicles on the roadway. The devastating wildfire on Maui in August 2023 is a tragic example, where 15 of the 100 victims were found inside of vehicles (Baker & Bogel-Burroughs, 202450).

In the case of the Caldor Fire, the regional transit provider was not part of the initial coordination of the emergency response. There were no existing evacuation plans for transit and no existing formal plans or emergency management that included transit- and paratransit-dependent people in the evacuation. While individual staff undertook advance planning of their own accord and were “heroic” in their efforts during the emergency response, an investment in hazard reduction and advance planning may relieve pressure on staff, improve efficiencies, and better integrate with broader incident command systems.

This case study demonstrates the value of incorporating transportation agencies and staff into evacuation planning and response. Many communities around the United States would likely benefit from better realizing their wildfire risk, and particularly, planning for evacuation that neither relies on private automobiles entirely nor leaves behind vulnerable groups that lack of evacuation access. This study helped illuminate and expand on challenges that should be of high priority to government agencies, emergency managers, transportation providers, and anyone dedicated to inclusive, safe, and effective disaster evacuation.

Implications for Practice or Policy

This case study has several implications for the role of transit in evacuation policy and practice, particularly for smaller and/or rural communities. There is a need to address both structural and cultural issues. I describe each of these recommendations in more detail below.

Transportation Professionals as Leaders and Partners in Emergency Management Structures

Formal agreements and well-communicated protocols could reduce the exclusion of transit providers from emergency operations. Increased training for emergency managers and responders could raise awareness of the potential for using transit in evacuations for larger numbers of people, and not just existing riders. Both formal designation of emergency roles within transportation agencies and additional capacity- and relationship-building between the transportation agency and local and regional emergency management officials may support earlier and more effective integration into emergency operation.

As emphasized by interviewees, transit agencies need to see themselves as key players in emergency response and be pro-active about ensuring their inclusion in emergency response from the beginning. Emergency managers and transportation professionals should work together to determine what would a transit-forward evacuation look like in practice in their community.

Planning for the Evacuation of People Who Cannot or Do Not Drive

Nearly one-fifth of Americans cannot or do not drive, whether by choice or circumstance. These non-drivers are more likely to be older adults, children, people with disabilities, and/or lower income, making their reliance on other forms of transportation an issue of equity (Smart Growth America, 202251). Importantly, transit providers and the broader emergency response community need to be more proactive and inclusive in planning for the evacuation of people with many types of disabilities and local unhoused citizens.

Transit and paratransit agencies occupy a unique role in identifying the needs of vulnerable populations (in the planning stage) and meeting those needs during the response because they serve, and have relationships with, these communities every day. As highlighted by the interviewees in this case study, they have unique knowledge and resources that should be drawn upon during emergency planning and response. This includes their existing relationships with partners organizations servicing vulnerable as well as the knowledge and experience that they have gained serving riders. One potential outcome of this would be identifying the correct people and methods who might provide peer support or mental health services to riders during disasters (e.g., on-board public health professionals), to both support individuals and reduce the burden on drivers.

The Need to Plan for Protection of the Assets Central to Transit Operations

The experience of the agency demonstrated that when transit assets (i.e., buses and maintenance equipment) are within evacuation zones, there is a need for safe and convenient places to relocate while minimizing disruptions to emergency services . This may require mutual aid agreements with other agencies or authorities (such as school districts), which have similar capabilities to stage and maintain buses.

The Potential of Transit for Proactive Evacuation During Disasters

The potential to use transit more proactively to evacuate the public during wildfire events was not the focus of this study. Yet, this theme emerged in the interviews as a topic that should be considered by transportation and emergency management professionals moving forward. While this is not a new idea, particularly after Hurricane Katrina, there appears to be little planning for it, particularly among smaller and rural agencies. However, it may be even more urgent to consider transit in rural and small communities than larger urban areas due to the limited roadway networks in rural areas. As summarized by one participant:

I think that’s the important thing – there needs to be more awareness of these resources and of these different roles that public transit can play. It’s kind of like airplanes [in an emergency]. Leave all your stuff behind and exit the plane. That’s what you need to do. It’s not like, ‘Oh, I need to save my car.’ You just get on the bus and go.

Limitations

As with all interviews, recall bias is inherently a challenge, particularly two years after the event. The intensity and novelty of the event, however, meant that interviewees had no problem recalling significant events. Additionally, there is value in understanding how participants remember and interpret their experiences now, since now is when the planning (or not) for the next event is happening.

In this initial study, I focused entirely on interviews with the transportation district staff. As evidenced by those interviews, the Caldor Fire response included an array of agencies, who may have different views on the role of transit and paratransit agencies in emergency response generally and the Caldor Fire specifically. Additional research on this event should include perspectives from other agencies and emergency professionals.

Next Steps and Future Research Directions

The creation of an updated Tahoe Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) is now underway. This process will provide additional insight into the lessons learned from the Caldor Fire and provides the potential for fruitful applied research. The agency coordinating the Tahoe CWPP has requested the findings from this report to include in a section on the lessons learned from the Caldor Fire.

No evacuation can be considered fully successful if it is not inclusive of people who do not or cannot use private automobiles. Yet there are many unknowns about the challenges and opportunities of non-automobile-based evacuation, including via public transit. By learning from the successes and challenges of this event, this report highlights research gaps and discusses lessons learned for future planning activities around transit and paratransit evacuation. The overarching questions that guided this research focused on what lessons can be learned not only for the Tahoe Basin, but areas that face similar potential challenges with complex transportation governance, topography, and/or transient/tourist populations.

I recently launched a new initiative to study inclusive evacuation—called the Planning the Future of Evacuation—Inclusive, Resilient, and Safe (PFEIRS) within the Texas A&M University Hazards Reduction and Recovery Center (HRRC). This study is the first in a series of research projects that I am planning to conduct in collaboration with other researchers and practitioners.

Endnote 1: This report uses the term “transit” to refer to public transportation systems, which are also frequently known as “mass transit” and “mass transportation” or simply “transit.” Transit systems may include rail, bus, streetcar, and bikeshare services. They are publicly funded and operated. The federal government defines public transportation as “regular, shared-ride surface transportation services that are open to the general public or open to a segment of the general public defined by age, disability, or low income” (Federal Transit Administration, n.d., Funding52). ↩

Endnote 2: Paratransit provides additional door-to-door transportation options for individuals for whom the local transit system in their region is not accessible due to its fixed routes or timetables. The prefix “para” means “alongside of”. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) mandates that any agency that provides publicly-funded transit systems must provide paratransit (U. S. Government Accountability Office, 202253). Individuals must apply and register for paratransit service, and eligibility is determined by the local agency rather than a national standard (National Express Transit, 201754). ↩

Acknowledgements. First and foremost, I would like to thank the Tahoe Transportation District staff who gave generously of their time and were willing to discuss events that were challenging both professionally and personally. I want to thank the Natural Hazards Center staff for selecting this project for funding and giving a nascent transportation disaster researcher a chance. Additional thanks to Chris Anthony, recent Deputy Director at CalFire, for his knowledge and for sharing evacuation maps. Haider Anwar, a PhD student, also aided with the initial literature review.

References

-

Atagi, C. (2021, August 30). Violinist plays at evacuation standstill as Caldor fire edges toward South Lake Tahoe. The Press Democrat. https://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/news/watch-violinist-playing-at-evacuation-standstill-as-caldor-fire-edges-towa/ ↩

-

Canon, G., & Anguiano, D. (2021, August 31). Chaos as Caldor fire forces unprecedented evacuation of Tahoe tourist town. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/30/caldor-fire-california-lake-tahoe-evacuations ↩

-

Miller, R. W., Wilkins, T., & Hayes, C. (2021, August 30). Caldor Fire: Roads packed after South Lake Tahoe ordered to evacuate; all national forests in California closed due to wildfires. USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/08/30/caldor-fire-red-flag-evacuations-warnings-across-lake-tahoe/5647169001/ ↩

-

Tahoe Transportation District. (2021). Tahoe Transportation District Special Board Meeting Agenda Packet. https://www.tahoetransportation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2021-6-18-Spec-TTD-Board-Mtg-Agenda-Packet.pdf ↩

-

Renne, J. L., Sanchez, T. W., Jenkins, P., & Peterson, R. (2009). Challenge of Evacuating the Carless in Five Major U.S. Cities: Identifying the Key Issues. Transportation Research Record, 2119(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.3141/2119-05 ↩

-

Renne, J. L. (2018). Emergency evacuation planning policy for carless and vulnerable populations in the United States and United Kingdom. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, 1254–1261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.02.016 ↩

-

Renne, J. L., & Mayorga, E. (2022). What has America learned since Hurricane Katrina? Evaluating evacuation plans for carless and vulnerable populations in 50 large cities across the United States. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 103226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103226 ↩

-

Kim, K., Renne, J., & Wolshon, B. (2019). Minding the gap: New section in transportation research, Part D to focus on disasters and resilience. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 77, 335–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.10.023 ↩

-

Donovan, B., & Work, D. B. (2017). Empirically quantifying city-scale transportation system resilience to extreme events. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 79, 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2017.03.002 ↩

-

Kim, K., Yamashita, E., Ghimire, J., Bye, P. G., & Matherly, D. (2022). Knowledge to Action: Resilience Planning Among State and Local Transportation Agencies in the United States (TRBAM-22-02189). Article TRBAM-22-02189. https://trid.trb.org/view/1909440 ↩

-

Kim, K., Pant, P., Yamashita, E., & Ghimire, J. (2019). Analysis of Transportation Disruptions from Recent Flooding and Volcanic Disasters in Hawai’i. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2673, 036119811882546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198118825460 ↩

-

National Rural Transit Assistance Program. (n.d.). National Rural Transit Assistance Program Rural, Public & Community. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.nationalrtap.org/ ↩

-

White, R. A., Blumenberg, E., Brown, K. A., Contestabile, J. M., Haghani, A., Howitt, A. M., Lambert, T. C., Morrow, B. H., Setzer, M. H., Stanley, Sr., E. M., Velasquez III, A., & Humphrey, N. P. (2008). The Role of Transit in Emergency Evacuation: Special Report 294. Transportation Research Board. https://doi.org/10.17226/12445 ↩

-

Higgins, L. L., Hickman, M. D., Weatherby, C. A., & Texas. Dept. of Transportation. Office of Research and Technology Transfer. (2000). Emergency Management Planning for Texas Transit Agencies: A Guidebook (FHWA/TX-00/1834-4). https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/41652 ↩

-

Boyd, A., Lazaro, R., Pankratz, D., & Lazaro, V. (2013). Paratransit Emergency Preparedness and Operations Handbook. Transportation Research Board. https://doi.org/10.17226/22669 ↩

-

Cova, T. J., Theobald, D. M., Norman, J. B., & Siebeneck, L. K. (2013). Mapping wildfire evacuation vulnerability in the western US: The limits of infrastructure. GeoJournal, 78(2), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-011-9419-5 ↩

-

Cirianni, F., Rindone, C., & Ianno, D. (2014, October 4). Public Transport in Evacuation Planning: The Case of Italy. 2014 European Transport Conference, Frankfurt, Germany. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4713.1362 ↩

-

Zhang, Z., Wolshon, B., & Murray-Tuite, P. (2019). A conceptual framework for illustrating and assessing risk, resilience, and investment in evacuation transportation systems. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 77, 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.08.016 ↩

-

Zhao, B., & Wong, S. D. (2021). Developing Transportation Response Strategies for Wildfire Evacuations via an Empirically Supported Traffic Simulation of Berkeley, California. Transportation Research Record, 2675(12), 557–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981211030271 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2024, January 5). Planning for People with Disabilities and Others with Access and Functional Needs Toolkit. https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/practitioners/recovery-resilience-resource-library/planning-people-disabilities ↩

-

Williams, P. C., Binet, A., Alhasan, D. M., Riley, N. M., & Jackson, C. L. (2022). Urban Planning for Health Equity Must Employ an Intersectionality Framework. Journal of the American Planning Association, 0(0), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2079550 ↩

-

United Nations. (n.d.). Disability-Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction and Emergency Situations. Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/issues/disability-inclusive-disaster-risk-reduction-and-emergency-situations.html ↩

-

Rhodes, T. (2017). Strategies for Inclusive Planning in Emergency Response. http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/eprp/documents/StrategiesforInclusivePlanninginEmergencyResponse_FINAL.pdf ↩

-

Asfaw, H. W., Sandy Lake First Nation, McGee, T. K., & Christianson, A. C. (2019). A qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators of effective service delivery for Indigenous wildfire hazard evacuees during their stay in host communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 41, 101300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101300 ↩

-

Gusner, P., & Masterson, L. (2023, June 7). Natural Disaster Facts And Statistics 2024. Forbes Advisor. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/homeowners-insurance/natural-disaster-statistics/#natural-disasters-occur ↩

-

Federal Highway Administration. (n.d.-a). Using Highways For No-Notice Evacuations: 3 Explanation of No-Notice Incidents—FHWA. Retrieved February 29, 2024, from https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/evac_primer_nn/chap3.htm ↩

-

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (Sixth edition). Sage. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/case-study-research-and-applications/book250150 ↩

-

Federal Highway Administration. (n.d.-b). Mitigating Traffic Congestion—The Role of Demand-Side Strategies: Lake Tahoe Basin—CA. Retrieved October 31, 2023, from https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/mitig_traf_cong/lake_tahoe_case.htm ↩

-

Anguiano, D. (2023, February 12). ‘Lake Tahoe has a people problem’: How a resort town became unlivable. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/feb/12/lake-tahoe-resort-housing-crisis ↩

-

CalFire. (2021, August 14). Caldor Fire Incident Report. https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2021/8/14/caldor-fire/ ↩

-

Serrin, G. (2022, August 15). Caldor Fire, One Year Later: A look back at the destructive blaze that burned into Lake Tahoe Basin. KCRA. https://www.kcra.com/article/caldor-fire-one-year-later/40874998 ↩

-

Sion, B., Samburova, V., Berli, M., Baish, C., Bustarde, J., & Houseman, S. (2023). Assessment of the Effects of the 2021 Caldor Megafire on Soil Physical Properties, Eastern Sierra Nevada, USA. Fire, 6(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire6020066 ↩

-

Miller, H. (2021, August 31). “Caldor is a real tough one for us”: Cal Fire chief talks about blaze’s progression. KCRA. https://www.kcra.com/article/caldor-fire-outlook-thom-porter-cal-fire/37435501 ↩

-

State of California. (2021, August 31). Governor Newsom Proclaims State of Emergency in Additional Counties Due to Caldor Fire, Signs Order to Support Wildfire Response and Recovery Efforts. California Governor. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2021/08/30/governor-newsom-proclaims-state-of-emergency-in-additional-counties-due-to-caldor-fire-signs-order-to-support-wildfire-response-and-recovery-efforts/ ↩

-

State of Nevada. (2021, August 30). 2021-08-30—Declaration of Emergency for the Caldor Fire. Declaration of Emergency for the Caldor Fire. https://gov.nv.gov/layouts/full_page.aspx?id=338563 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2021, December 14). Designated Areas | FEMA.gov. Designated Areas: Disaster 4619. https://www.fema.gov/disaster/4619/designated-areas ↩

-

U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.). Caldor Fire Recovery. Retrieved February 18, 2024, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/eldorado/home/?cid=fseprd952172 ↩

-

Metz, S., & Har, J. (2021, August 31). Wildfire Evacuees Fill Lake Tahoe Roads in Rush to Flee. NBC Bay Area. https://www.nbcbayarea.com/news/california/caldor-fire-lake-tahoe-evacuations-traffic/2644500/ ↩

-

Tahoe Transportation District. (n.d.-a). Frequently Asked Questions – Tahoe Transportation District. Retrieved March 3, 2024, from https://www.tahoetransportation.org/about/faq/ ↩

-

Tahoe Transportation District. (n.d.-b). Board of Directors – Tahoe Transportation District. Retrieved March 3, 2024, [from https://www.tahoetransportation.org/board-of-directors/](from https://www.tahoetransportation.org/board-of-directors/) ↩

-

Tahoe Transportation District. (2024). Tahoe Transportation District (TTD) Finance and Personnel Committee Agenda Packet. https://www.tahoetransportation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/2024-2-7-TTD-Finance-Comm-Mtg-Agenda-Packet.pdf ↩

-

Saldaña, J. (2023). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (Fourth). Sage Publications Ltd. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/the-coding-manual-for-qualitative-researchers/book273583 ↩

-

Brown, N. (n.d.). Reflexivity and Positionality in Social Sciences Research. Social Research Association. Retrieved November 7, 2023, from https://the-sra.org.uk/SRA/SRA/Blog/ReflexivityandPositionalityinSocialSciencesResearch.aspx ↩

-

Angst, M., & Kelliher, F. (2021, August 31). Caldor Fire evacuation caused hours of South Lake Tahoe traffic gridlock. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2021/08/30/its-out-of-control-caldor-fire-prompts-south-lake-tahoe-evacuation-traffic-gridlock/ ↩

-

Chadwin, R. (2017). Evacuation of Pets During Disasters: A Public Health Intervention to Increase Resilience. American Journal of Public Health, 107(9), 1413–1417. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303877 ↩

-

Moody, J., Goulet Langlois, G., Alexander, L., Campbell, J., & Zhao, J. (2016). Measuring Explicit and Implicit Social Status Bias in Car vs. Bus Mode Choice. ↩

-

Maus, J. (2023, February 7). Podcast: Car culture researcher Tara Goddard. BikePortland. https://bikeportland.org/2023/02/07/podcast-car-culture-researcher-tara-goddard-370100 ↩

-

Walker, I. (2005). Road users perceptions of other road users: Do different transport modes invoke qualitatively different concepts in observers? Advances in Transportation Research, 6A(a), 25–36. ↩

-

Walker, I., Tapp, A., & Davis, A. (2022). Motornomativity: How Social Norms Hide a Major Public Health Hazard. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/egnmj ↩

-

Baker, M., & Bogel-Burroughs, N. (2024, February 7). 9 Key Revelations in Maui’s First Review of the Lahaina Inferno. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/06/us/maui-fire-investigation-deaths.html ↩

-

Smart Growth America. (2022). Dangerous by Design 2022. https://smartgrowthamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Dangerous-By-Design-2022-v3.pdf ↩

-

Federal Transit Administration. (n.d.). About FTA. Retrieved February 29, 2024, from https://www.transit.dot.gov/about-fta ↩

-

U. S. Government Accountability Office. (2022, July 21). Mobility Ability: 25 Years of ADA Transit Services | U.S. GAO. https://www.gao.gov/blog/2015/07/22/mobility-ability-25-years-of-ada-transit-services ↩

-

National Express Transit. (2017, December 28). 7 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Paratransit. https://www.nationalexpresstransit.com/blog/7-things-you-probably-didnt-know-about-paratransit/ ↩

Goddard, T. (2024).