Risk Messaging During Syndemics

Publication Date: 2022

Executive Summary

Overview

In August 2020, the Gulf Coast along the state line that divides Texas and Louisiana was hit by Category 4 Hurricane Laura. The area, like the rest of the world, was also coping with a pre-vaccine increase in COVID-19 cases. This study uses syndemic theory and the protective action decision-making model to understand how stakeholders in emergency response and communication balanced a dual threat environment that involved conflicting protective action messaging. Protective actions regarding COVID-19 exposure included social distancing, while protective action for Hurricane Laura included evacuation and sheltering.

Research Questions

This study examined the following three research questions:

- What hurricane and pandemic risk information sources do emergency managers rely on?

- How do emergency managers distribute hurricane and pandemic risk information to the public?

- What communication strategies were perceived as most effective during the multi-hazard event?

Research Design

We conducted 35 semi-structured interviews with emergency management stakeholders in Texas and Louisiana in the spring of 2021. Participants were recruited using a purposive sample designed to identify agency representatives and other officials involved in Hurricane Laura response that we could speak with. Thematic analysis was used to code and analyze the data.

Findings

Survey participants relied on various sources to access information about the risks posed by both COVID-19 and Hurricane Laura. Participants at the state and local levels typically identified federal sources of information, such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the National Weather Service (NWS). Participants at the local level also relied heavily on state and local health departments.

Many interview participants stated that COVID-19 presented communication challenges within their own organizations and with constituents because of social distancing and the reliance on virtual meetings. Sheltering precautions, primarily non-congregate sheltering, also made it difficult for local entities to communicate information to their constituents who werer spread across multiple hotels and sometimes located in different states. Several participants noted they used flyers or other printed materials to communicate with evacuees and other residents.

While both Louisiana and Texas relied heavily on non-congregate sheltering for evacuees, each state took a different approach to coordinating sheltering and both presented challenges. Many participants stated that 211 networks were a primary way to communicating important information to individuals spread across hotels; they also used relationships with media contacts in host cities.

Practical Implications

It is likely that dual-hazard threats will increase in the future, and therefore, emergency response and planning agencies should focus on how to gather and disseminate information regarding protective actions before these events. Individuals engaged in risk communication should identify a diverse set of options in the planning and mitigation stages in order to overcome any difficulties accessing customary communication channels, such as cell phone service or media centers. Furthermore, in instances where dual threats have conflicting protective actions, those communicating risk will have to carefully assess all the risks and effectively communicate both the trade-offs and the protective actions to stakeholders. Therefore, we should invest in better emergency manager awareness and emergency management policy that encourages a greater understanding of risk assessment and risk analysis at all levels of emergency management.

Introduction and Literature Review

This project examines the process of risk messaging during a dual-hazard event (hurricane and pandemic). This project is guided by syndemic theory (Hart & Horton, 20171; Singer, 20092). As indicated in the theory, “the synergistic interaction of coexisting diseases and biological and environmental factors” (Hart & Horton, 2017, p. 888) worsens the complex outcomes of chronic and infectious diseases in marginalized racial and ethnic populations living in poverty. While protective actions and risk communication have been widely studied, syndemic theory has not often been applied to examine coinciding natural and biological hazards, including hurricane protective action decisions when facing a harmful social condition resulting from a pandemic, and varying risk communication strategies employed during a syndemic (Huang et al., 20123; Kendra et al., 20084; Lindell & Hwang, 20085; Wu et al., 20206; Wu et al., 2015a7, 2015b8). This study uses a qualitative approach to address this literature gap. A total of 35 emergency management professionals in Texas and Louisiana were interviewed during the spring of 2021, during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic management and Hurricane Laura. Thematic analyses were used to code and analyze the data. The project translates findings from risk and health communication and emergency management into a set of risk communication practices and guidelines for future dual hazards or syndemics in the United States.

This study investigated the risk communication process and protective action decisions during a dual-threat event: Hurricane Laura and COVID-19. While these circumstances were novel, past literature provided a starting point for inquiry. First, experimental studies have demonstrated that people prefer graphic communication and categorical risk intensity ratings (e.g., the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale) when making protective action decisions (Choi, 20209; Meyer et al., 201310; Wu et al., 201411). These studies provided insights to meteorologists and emergency managers for presenting hurricane risk information to the public, but did not address why the public prefers certain types of information and how this information leads to protective action.

Second, studies have shown people typically evacuate to and shelter at the homes of friends and relatives, hotels, and public shelters during a hurricane threat (Huang et al., 2012, 201612; Wu et al., 201213, 201314). The London Imperial College’s report No. 38 suggested that the COVID-19 transmission rate was highest when people gathered indoors for a sustained duration (Thompson et al., 2020). Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, sheltering in these locations without proper cleaning, physical distancing, and protective action could spread the disease and create a premature or risky evacuation reentry process.

It was unclear how perceptions of evacuation routes, transportation modes (private vehicles and public buses), and evacuation destinations (shelters, hotels, etc.) influenced behavioral response decisions during this dual-threat event. In addition, the movement of people increased the risk of disease spread in the community and created challenges in managing the outbreak. Emergency managers needed to be able to prepare built environment systems (e.g., traffic management, shelters, hotels) in a way that makes those impacted feel safe, as well as use infection control protocols to monitor disease spread. Households also needed to be able to adequately prepare their families for better disaster response outcomes (Tierney et al., 200115). While literature has shown that household members often evacuate together (Drabek, 198616), some recent evidence suggests households might evacuate separately (Maghelal et al., 201717). This could be amplified and more challenging during a dual-threat event, where each household member could have varying levels of risk for COVID-19 that could lead to conflicting protective action choices (evacuate vs. shelter in place) within households.

Finally, there is a need to investigate this issue through the lens of syndemic theory. As hazards increase in frequency and severity, individuals, households, communities, and institutions will be faced with preparing for, responding to, and recovering from multiple hazards more often. Syndemic theory provides a deeper understanding of the interactions of hazard events, how exposures to multiple hazards cluster, and the social conditions that influence how individuals cope with and respond to the complexities of multiple events (Mendenhall et al., 202118).

Research Design

Research Questions

Our three research questions were:

- What hurricane and pandemic risk information sources do emergency managers rely on?

- How do emergency managers distribute hurricane and pandemic risk information to the public?

- What communication strategies were perceived as most effective during the multi-hazard event?

Study Site Description

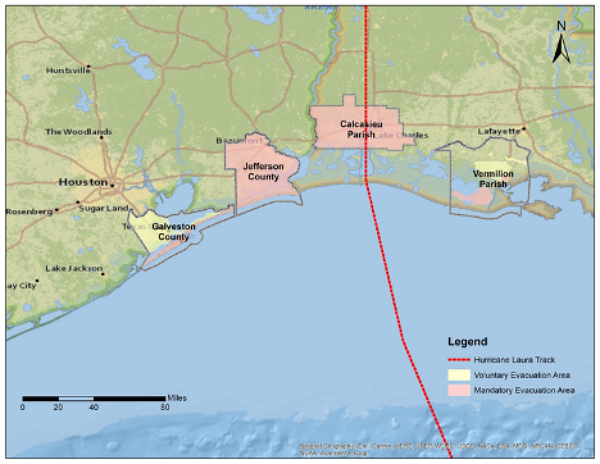

Based on preliminary damage assessments and the type of evacuation orders, four areas in Texas and Louisiana were selected for this study. Mandatory evacuation areas included the Bolivar Peninsula, the City of Galveston in Galveston County, and Jefferson County in Texas and Calcasieu Parish, Pecan Island, Intracoastal City, Esther, Forked Island, Mouton Cove, South Erath, South Delcambre, and South Gueydan in Vermilion Parish in Louisiana. Voluntary evacuation areas included Galveston County in Texas and several areas in Louisiana (below Highway 14 in Erath and Delcambre, south of Abbeville, south of Highway 335, west of Vermilion River in Vermilion Parish. See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Hurricane Laura Track and Study Area

Data, Methods, and Procedures

Building on a previous National Science Foundation-funded project (Award # 2051578), this project added interviews with chief information officers and health communication professionals from emergency management and public health offices in Texas and Louisiana. Adding these interviews to ongoing research project interviews and surveys of decision-making and behavior during a multiple-hazard event supported a more complete understanding of the role of risk messaging. Participants were recruited using a purposive sample designed to identify representatives from agencies and organizations, as well as other officials, involved in responding to Hurricane Laura. Potential participants were identified from state and local agency websites, after-action reports from past hurricane events, and through snowball sampling with interviewees. Interviewees were asked for information on their roles; their agency’s role in COVID-19 response; their process for planning for the hurricane season; Hurricane Laura evacuation and sheltering; and reentry decisions after the hurricane. With our focus on information gathering and dissemination processes, we asked participants to detail where they acquired information about COVID-19 and hurricanes and how they shared information with the public. In addition, given the quick succession of hurricanes in the area, we also asked participants to reflect on their experiences with Hurricane Delta, which struck less than two months after Laura.

Interviewers obtained informed consent from interviewees before beginning the interviews. Once consent was provided, interviews began and were recorded. Interviews were transcribed for analysis. Interview transcripts were analyzed deductively using a codebook incorporating syndemic theory and the literature on hurricane risk communication, health communication, and emerging literature on pandemic risk communication (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 201919; Eisenman et al., 200720; Guion et al., 200721; Hart & Horton, 2017; Reynolds & Seeger, 200522; Wogalter et al., 200223). Interviews were also inductively coded using process and open coding to identify emergent themes for this multiple hazard event.

Sampling and Participants

A total of 19 emergency management professionals in Texas and 16 in Louisiana were interviewed. Each participant had a role in the risk communication process, from interpreting science to delivering messages to the public. Exclusion criteria included being under age 18 or not involved in the Hurricane Laura or COVID-19 response in Louisiana or Texas. The interviews were conducted during the spring of 2021.

Ethical Considerations & Researcher Positionality

The Institutional Review Board at the University of North Texas reviewed and approved this research on August 28, 2020 (IRB-20-509). The research team was well-positioned to conduct research on Hurricane Laura as they have extensive hurricane and emergency management research expertise, experience studying evacuation behavior, and local knowledge of Texas and Louisiana from living and/or working there.

Preliminary Findings

Below, we present preliminary findings that begin to address research questions about issues relating to information sources, communication challenges, and perceptions of communication strategies.

Information Sources

Participants named a number of sources when describing how they acquired information about the risks posed by both COVID-19 and Hurricane Laura. Participants at the state level often cited federal sources of information, particularly the CDC for COVID-19 information and guidance and the National Hurricane Center and National Weather Service (NWS) for hurricane forecasts and updates. Emergency managers relied on guidelines from the CDC for COVID-19 precautions in evacuation and sheltering (i.e., busing evacuees, congregate versus non-congregate sheltering), but they were also bound by guidance from state-level agencies.

At the local level, in regard to COVID-19, many participants still mentioned the CDC but also noted substantial reliance on their state health departments. In some cases, participants noted that local health departments were heavily involved, but others suggested that local health departments deferred to the state in response to COVID-19 concerns:

So that was driven by Louisiana Department of Health, which was following the CDC guidelines and the guidance from the CDC. So we were very careful to not just spin off on our own and just say, "I found this article on COVID-19"…we wanted to keep things centralized and really follow the CDC guidance on that. (Louisiana Emergency Management Professional)

Many local- and state-level participants noted that they had pre-existing relationships with NWS offices and that they would speak to the NWS daily about storm updates. Others suggested that the NWS would embed individuals with them during hurricanes for direct information to influence evacuation and sheltering decision-making before and during hurricanes. A common theme across interviewees was concern that Hurricane Laura’s path would (or would not) shift, moving the storm’s path to center more on Louisiana:

Of course it was a Category 4 and it was headed this way and the weather service couldn't really guarantee whether or not it was going to make that right-hand turn. What I was afraid of is in the trends that we've had…rapid intensification with several of the storms before that, and we had it with this as well, and we were anticipating that. I'm not a meteorologist, but I really watched the trends and try to watch what's possible, so we were prepared. (Louisiana Emergency Management Professional)

Nonprofits and city- and county-level officials often referred to many of the same sources but also discussed their reliance on local meteorologists who worked for local news outlets.

Communication Channels

According to many of our interviewees, COVID-19 presented challenges in planning for the hurricane season. Interviewees noted that, before COVID-19, they conducted many of their meetings with collaborators in person, but the risks associated with COVID-19 caused them to move their communications online. While some noted that this transition was smooth, a number said that it was challenging and that many were feeling “Zoom fatigue” quickly.

The COVID problem this year…because we're unable to have many of the face-to-face meetings that we would normally have, we've had to do them by Zoom, Teams, or whatever. I think everybody's tired of that by now, but that's what we had and that's what we had to work with. (Louisiana Emergency Management Professional)

Hurricane Laura disrupted communication channels in areas that suffered substantial impacts, and the non-congregate sheltering approach also dispersed evacuees in a way that presented additional communication challenges. Participants noted that electricity and internet were down for three to six weeks in some sites. Cell phones for select carriers were out for a while as well, along with damage to news stations and their necessary infrastructure for sharing information. This created an environment that required flexible communication with both coworkers and residents.

If they were signed up for that [211] service, then they get those messages. But without internet access, it was quite a challenge. The newspaper wasn't printing. The TV station…were doing their best to broadcast on social media…But if you didn't have internet or electricity, because we were without electricity for three to six weeks, you didn't get that information. (Louisiana Emergency Management Professional)

When communicating with the public before and after Hurricane Laura, stakeholders used diverse communication channels, including social media, mass telephone/text emergency alert systems, local television, radio, and 211 systems, which refer residents to needed services. In a few cases, participants described printing and hand delivering informational flyers each day, as well as communicating with displaced residents using television news media contacts in host cities. They pushed messaging that provided updates on the availability of contractors for repairs, space in local shelters, the status of local utilities, services available from local non-governmental organizations, and information from the state. In some cases, however, agency personnel resorted to going door to door:

Everybody would just pick a neighborhood and go through and talk to people and just check on them and say, "Hey, do you want to get out of here? If you want to, here's how you do that." You get so reliant on technology, but sometimes you have to go back to the basics. And in those few weeks or so after Laura, and even after…Delta, that's what we did. (Louisiana Emergency Management Professional)

When speaking with emergency managers and public information officers, we commonly heard participants describe themselves as intermediaries in sharing information. They often said that they were not generating essential information for the public, but instead that they served as a trusted source to distribute the information. They also noted that they had established infrastructure—whether a 211 information network, social media, or relationships with local media—to share that information with the public:

We are probably what they call a middleman. From the state agencies, down to the [parish] residents…. So we're the middle guy. They pass it down to us, and we go ahead and take the information, and we send it down to the mayors, chief of police, hospitals, nursing homes. Make sure everybody gets the information that they're trying to put out. (Louisiana Emergency Management Professional)

A number of participants also mentioned that changes in COVID-19 guidance presented challenges in serving as intermediaries. One interviewee stated, “COVID, like [everything] else, has been very challenging because of constant changing information, which we understand…we still pushed our message and pushed the resources that we had available for our community, pushed free testing, pushed free COVID vaccines.”

Perceptions of Communication Strategies

When asked about how COVID-19 affected their communication strategies in response to Hurricane Laura, many participants described challenges largely associated with communicating about how to find a shelter and communicating with a dispersed set of evacuees. Participants explained that coordinating hotel availability and routing evacuees to appropriate hotels was challenging. While Texas eventually worked with a third-party vendor to establish a reservation system, Louisiana managed its demand by working with local hotels and an unnamed hotel association in the state. As noted by participants, this led to a number of issues, particularly in coordinating who went to what shelter:

…when folks are coming up here, their friends and neighbors are evacuating too. And so they text or Facebook or whatever they do and share information… "Hey, there's rooms available in Frisco." And they bypass the reception center, because you're supposed to go there first, and then they tell you which hotel. Because we had hotels…all over North Texas, but the hub is supposed to direct that based on how many you have available, and then you can send them to where there's room, but sometimes they bypass that. (Texas Emergency Management Professional)

We also heard, on several occasions, that participants had to work through hotels to communicate with displaced residents, which made it difficult to ensure messages were received, to track who was in shelters, and to coordinate reentry into the community. One Texas emergency management official explained that the “fragmentation makes things even harder to track” because those sheltering weren’t in a common area where they could get critical information—they might be in their room or out of the hotel entirely. The official went on to say:

When it came time to call for the repopulation of the city, bring our folks back home, there was definitely a problem with herding the cats. That's the best way I can explain it. [The hotels] would get the buses loaded up. Everybody's there. They're coming home and next thing you know, I find out there's another 20 or 30 people in another hotel, somewhere that we've missed…. That's probably the best way that to paint the picture…it was an exercise in herding cats.

Many participants suggested that their 211 system served a critical role in response to Hurricane Laura, particularly by providing information about evacuation to vulnerable populations and about non-congregate sheltering. A Texas emergency management professional shared that:

…we partnered with 211 and we always have in terms of getting the message out….We supply 211 with the right info and then the 211 operators direct that person, based on their need, to the appropriate resource or place to get the information. …For example, during the Hurricane Laura evacuation when we did the virtual reception center, we gave 211 the number and the information on the virtual reception center…When someone would call 211, the 211 operator would tell them, “okay, I understand you need a shelter. Call this number…and then they'll process you from there.” So 211…was a conduit to get people to that virtual reception.

Conclusions

Key Findings

Our findings highlight ways that COVID-19 affected communication around Hurricane Laura. First, participants acknowledged that, due to the nature of the risk, they relied on new information sources, such as the CDC and state and local public health officials, when planning and carrying out the evacuation efforts in response to Hurricane Laura. While these were known entities, they weren’t typically involved in hurricane planning or evacuation efforts previously. Second, participants noted that, from the planning stage to re-entry, COVID-19 forced them to work in a remote environment with diverse stakeholders, which led to concerns about the quality of collaborations and Zoom fatigue. Likewise, lifeline outages and the scale of displacement led to unconventional messaging efforts when reaching the public. Finally, due to the scale of the displacement and non-congregate sheltering, participants said that they created new intake systems for evacuees and relied heavily on hosting hotels to share messages with evacuees.

Limitations

Our study has a few important limitations, primarily related to sampling, that could lead to some form of response bias or an incomplete picture of messaging in this context. We found participants via web searches and snowball sampling, potentially limiting our ability to find contradicting or differing experiences. Likewise, in some areas in southeastern Texas, we struggled to find participants. We learned through subsequent interviews that there was considerable personnel turnover since the hurricane there and that, additionally, many of the hotels that hosted evacuees were in northern Texas, where we were quite successful in finding participants. While we made attempts to contact them, we also were unable to recruit participants representing hosting hotels, which would have provided a fuller picture of communication with evacuees.

Future Research

Our work provides a starting point for future research. First, future work could compare our interview results with other data sources such as after-action reports and media reporting to develop a better understanding of communication around the evacuation effort. Second, there have been other situations, such as wildfires in California or hurricanes in Florida, where evacuation orders were issued during COVID-19. Comparing cross-hazard and cross-state experiences could shed light on communication in dual-hazard environments. Finally, future work should consider messaging from the public’s perspective. Given that Louisiana and Texas both have considerable experience with hurricanes, it would be beneficial to ask residents how they would compare communication across past events.

References

-

Hart, L., & Horton, R. (2017). Syndemics: committing to a healthier future. The Lancet, 389(10072), 888. ↩

-

Singer, M. (2009). Introduction to syndemics: A critical systems approach to public and community health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ↩

-

Huang, S., Lindell, M., Prater, C., Wu, H., & Siebeneck, L. (2012). Household evacuation decision making in response to Hurricane Ike. Natural Hazards Review, 13(4), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000074 ↩

-

Kendra, J., Rozdilsky, J., & McEntire, D. A. (2008). Evacuating large urban areas: Challenges for emergency management policies and concepts. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1365 ↩

-

Lindell, M., & Hwang, S. (2008). Households’ perceived personal risk and responses in a multi-hazard environment. Risk Analysis, 28(2), 539–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01032.x ↩

-

Wu, H.-C., Huang, S.-K., & Lindell, M. (2020). Evacuation planning. In M. Lindell (Ed.), Handbook of urban disaster resilience: Integrating mitigation, preparedness, and recovery planning. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. ↩

-

Wu, H., Lindell, M., & Prater, C. (2015a). Process tracing analysis of hurricane information displays. Risk Analysis, 35(12), 2202–2220. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12423 ↩

-

Wu, H., Lindell, M., & Prater, C. (2015b). Strike probability judgments and protective action recommendations in a dynamic hurricane tracking task. Natural Hazards, 79(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-1846-z ↩

-

Choi, S. (2020). Tornado warning response among international and domestic college students in a dynamic tracking task. Oklahoma State University. https://shareok.org/bitstream/handle/11244/325528/Choi_okstate_0664D_16766.pdf?sequence=1 ↩

-

Meyer, R., Broad, K., Orlove, B., & Petrovic, N. (2013). Dynamic simulation as an approach to understanding hurricane risk response: insights from the Stormview lab. Risk Analysis, 33(8), 1532–1552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01935.x ↩

-

Wu, H., Lindell, M., Prater, C., & Samuelson, C. (2014). Effects of track and threat information on judgments of hurricane strike probability. Risk Analysis, 34(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12128 ↩

-

Huang, S., Lindell, M., & Prater, C. (2016). Who leaves and who stays? A review and statistical meta-analysis of hurricane evacuation studies. Environment and Behavior, 48(8), 991–1029. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0013916515578485 ↩

-

Wu, H., Lindell, M., & Prater, C. (2012). Logistics of hurricane evacuation in Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 15(4), 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2012.03.005 ↩

-

Wu, H., Lindell, M., & Prater, C. (2013). The logistics of household hurricane evacuation during Hurricane Ike. In J. Cheung & H. Song (Eds.), Logistics: Perspectives, approaches and challenges (pp. 127–140). Nova Science Publishers. ↩

-

Tierney, K., Lindell, M., & Perry, R. (2001). Facing the unexpected: Disaster preparedness and response in the United States. Washington DC: Joseph Henry Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/9834/facing-the-unexpected-disaster-preparedness-and-response-in-the-united ↩

-

Drabek, T. E. (1986). Human system responses to disaster-an Inventory of sociological findings. New York: Springer International Publishing. ↩

-

Maghelal, P., Peacock, W. G., & Li, X. (2017). Evacuating together or separately: Factors influencing split evacuations prior to Hurricane Rita. Natural Hazards Review, 18(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000226 ↩

-

Mendenhall, E., Newfield, T., & Tsai, A. (2021). Syndemic theory, methods, and data. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 114656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114656 ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Crisis & emergency risk communication (CERC) Manual. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/manual/index.asp ↩

-

Eisenman, D. P., Cordasco, K. M., Asch, S., Golden, J. F., & Glik, D. (2007). Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Public Health, 97(S1), s109–s115. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.084335 ↩

-

Guion, D. T., Scammon, D. L., & Borders, A. L. (2007). Weathering the storm: A social marketing perspective on disaster preparedness and response with lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 26(1), 20–32. ↩

-

Reynolds, B., & Seeger, M. (2005). Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. Journal of Health Communication, 10(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/-10.1080/10810730590904571 ↩

-

Wogalter, M. S., Conzola, V. C., & Smith-Jackson, T. L. (2002). Research-based guidelines for warning design and evaluation. Fundamental Reviews in Applied Ergonomics, 33(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(02)00009-1 ↩

Clay, L., Greer, A., Murphy, H., & Wu, H. (2022). Risk Messaging During Syndemics (Natural Hazards Center Weather Ready Research Report Series, Report 9). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/risk-messaging-during-syndemics