Adapting Transportation to Accommodate Populations Vulnerable to COVID-19 in Hazardous Settings

Publication Date: 2021

Abstract

Effective evacuation and sheltering operations in advance of a severe weather event require resources, including transportation assets and personnel, to be matched with the need for services. In a compound hurricane and pandemic scenario both demands and capacities may be truncated by space limitations to allow for social distancing; budgetary and staff strain from prolonged pandemic response; and risk of virus transmission. This study addresses three research questions to identify how planning efforts and transit options may be adjusted:

How has COVID-19 altered the composition and distribution of vulnerable populations in need of transportation options for evacuation and sheltering?

What is the threshold for evacuation and sheltering in the case of a compound natural hazard?

How can transportation adapt to the needs of the additional populations and demands for evacuation and sheltering in the case of a compound (pandemic and other) hazard?

First, we generated visualizations of redistributed vulnerability and transportation resources from geospatial and statistical analysis of survey data assessing evacuation behavior in southeastern Virginia. Then, we utilized themes from national workshops on preparation for the 2020 hurricane season during the COVID-19 pandemic to provide context regarding expectations and options being considered. Finally, we re-convened stakeholders from emergency management, transportation, and public health in a workshop. Participants evaluated progress toward adapting evacuation transportation options in Hampton Roads, Virginia, through a participatory web application and facilitated discussions. Results show that demand for sheltering assistance stayed consistent amongst populations previously in need. However, fear of virus transmission motivated others to reconsider evacuation decisions, which may leave more vulnerable populations in high-risk areas. From the beginning to the peak of hurricane season agreement emerged regarding messaging and non-congregate options for evacuation and sheltering. COVID-19 protocols and enforcement thereof, however, varied by jurisdiction. Real-time web applications with tailored sets of data layers were of interest for evacuation facilitation, especially with reduced timelines between order issuance and landfall common during the pandemic.

Introduction

Natural hazards may disrupt transportation systems. For hydrometeorological hazards, such as hurricanes and floods, evacuation routes may need to be used and traffic flow changed. Resources need to be deployed via roadway, rail, and air to areas that declare an emergency in advance of a hazard. Vulnerable populations in hazardous areas may depend on transit resources to evacuate or reach a shelter. A pandemic alters supply chains, changes the density of vehicles on roadways, and limits the number of seats available on public transit. It also increases the burden of public-facing transportation workers to provide safe options to populations with emergent or exacerbated vulnerabilities. The performance of the transportation sector has significant public health and economic implications for vulnerable populations, especially during a compound hazard.

Vulnerable populations have an increased risk of negative outcomes from hazards due to political, economic, or social inequities experienced at the household, community, state, or federal level (Wisner et al., 20041). A variety of factors beyond traditional vulnerability indicators influence evacuation decision-making at the household level including perceived risk, information received, previous hazard experience, pets, social amplification of risk, location, and type of evacuation order issued (Bowser & Cutter, 20152; Hasan et al., 20113; Sadri, 20174). After Hurricane Katrina, evacuation approaches reliant upon an individual or household automobile changed to accommodate more vulnerable populations (Deka & Carnegie, 20105). Transportation is critical for accessing medical care, shelter, and other life-sustaining resources. Limited transportation options contribute to poor health outcomes, particularly for vulnerable populations (Syed et al., 20116). The transportation sector uses an all-hazards approach to preparedness and coordinates with federal, state, and local authorities to provide services for vulnerable populations in the case of an emergency requiring an evacuation and sheltering (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 20187). Randomizing factors, such as fears during a concurrent pandemic, make evacuation and sheltering needs difficult to determine. Manuals for Hazard Identification Risk Assessment and Community Emergency Response Team(s) require additional information on prolonged and compound hazards, especially those where underlying health conditions exacerbate risk.

Methods

This study uses geospatial technology to engage emergency, public health, and transportation officials in a participatory research process to address the redistribution of vulnerable populations related to COVID-19 and altered options for evacuation and sheltering under a compound hazard.

Research Questions

We addressed three research questions to assess the demand for and evolving capacity to provide emergency transportation services to vulnerable populations during a compound hazard (hurricane and pandemic):

How has COVID-19 altered the composition and distribution of vulnerable populations in need of transportation options for evacuation and sheltering?

What is the threshold for evacuation and sheltering in the case of a compound natural hazard?

How can transportation adapt to the needs of the additional populations and demands for evacuation and sheltering in the case of a compound (pandemic and other) hazard?

A web application of populations vulnerable to COVID-19; demand for evacuation and sheltering; potential route changes; and resource needs to account for the transportation demands of emerging vulnerable populations was produced.

Study Site

Tropical cyclones occasionally require evacuation of Virginia’s coastal areas (Liu et al., 20168). A combination of development, geographic, and geologic features increase the likelihood of flooding from high tides and heavy rains in Hampton Roads, a set of cities in southeast Virginia at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay (Allen & Allen, 20199). For example, sea level rise has occurred at twice the global average rate over the past 80 years (Eggleston & Pope, 201310). Emergency planners throughout the region and in neighboring states are particularly concerned about how these factors affect roadway and shelter access during evacuations (Kirchmeier-Young & Young, 2020). Navigating around flooded roadways or to more distant shelters would increase transportation costs and timelines. Consequently, evacuation planners prioritize roadway flooding reduction, shelter retrofitting, and communication of evacuation assistance (Hampton Roads Planning District Commission, 201711). Although modeling software such as HURREVAC allows tailoring emergency operations to specific storm characteristics, and spatial datasets allow identification of at-risk populations and resources for transportation and sheltering, as well as monitoring traffic flows, cooperation between jurisdictions is necessary to unify and disseminate information in user-friendly applications. The Virginia Hurricane Evacuation Restudy is an example of federal, state, and local cooperation to unite the most updated static data with modeling software in a dynamic online platform (Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 202012). However, there is still room for improvement through the integration of real-time and fine-scale data.

Studies of evacuation behavior within Hampton Roads in response to previous hurricanes (i.e., Hurricane Irene) indicate that vulnerable and medically fragile populations have lower propensity to evacuate relative to non-vulnerable populations (Ng et al., 201413; Ng et al., 201514). Variation in risk perception, access to transportation, and resources to support basic needs once outside the region are cited as explanations for sheltering within the region (Ng et al., 201615).

It is reasonable to assume that for medically fragile and vulnerable populations, the propensity to either evacuate or shelter in a congregate venue will be less under a pandemic-type public health crisis (Behr et al., 201316; Behr et al., 201417). With this premise in mind, as we continue through the 2020 hurricane season, we must revisit planning assumptions and adjust plans. Taking action sooner rather than later will allow an opportunity to alter transportation and sheltering practices in a way that will effectively reduce risk posed to vulnerable populations and, thus, encourage hesitant populations.

Data

Surveys of Hampton Roads were quantitatively and geospatially analyzed to identify and visualize changes in behavior, as well as demand for evacuation and sheltering and the role of transportation or virus transmission in household decision-making. Workshop and focus groups of emergency management, public health, and transportation professionals contributed to a temporal analysis of policy and procedural adaptations for evacuation and sheltering operations during the post-lockdown/pre-vaccine period.

Hurricane Florence Survey

Analysis of the Hurricane Florence survey showed the role of transportation options in past evacuation behavior. The survey was produced by Old Dominion University’s (ODU) Virginia Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation Center and conducted by the ODU Social Science Research Center (SSRC). The dataset included 1,210 phone surveys completed by residents of seven Hampton Roads cities (Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Portsmouth, Chesapeake, Newport News, Hampton, and Poquoson) between November 11, 2018 and February 19, 2019. The survey covered topics such as evacuation and shelter behaviors, as well as how costs associated with those behaviors may have influenced respondents’ decisions. The Resilient Distribution Dataset for telephone numbers, including mobile phones, was used for random stratified sampling with oversampling of residents in evacuation Zone A based on listed numbers. Quantitative analysis included percentages and crosstabs generated using SPSS to identify behaviors and the influence of transportation limitations upon them. Geospatial analysis was conducted for past evacuation and sheltering behavior.

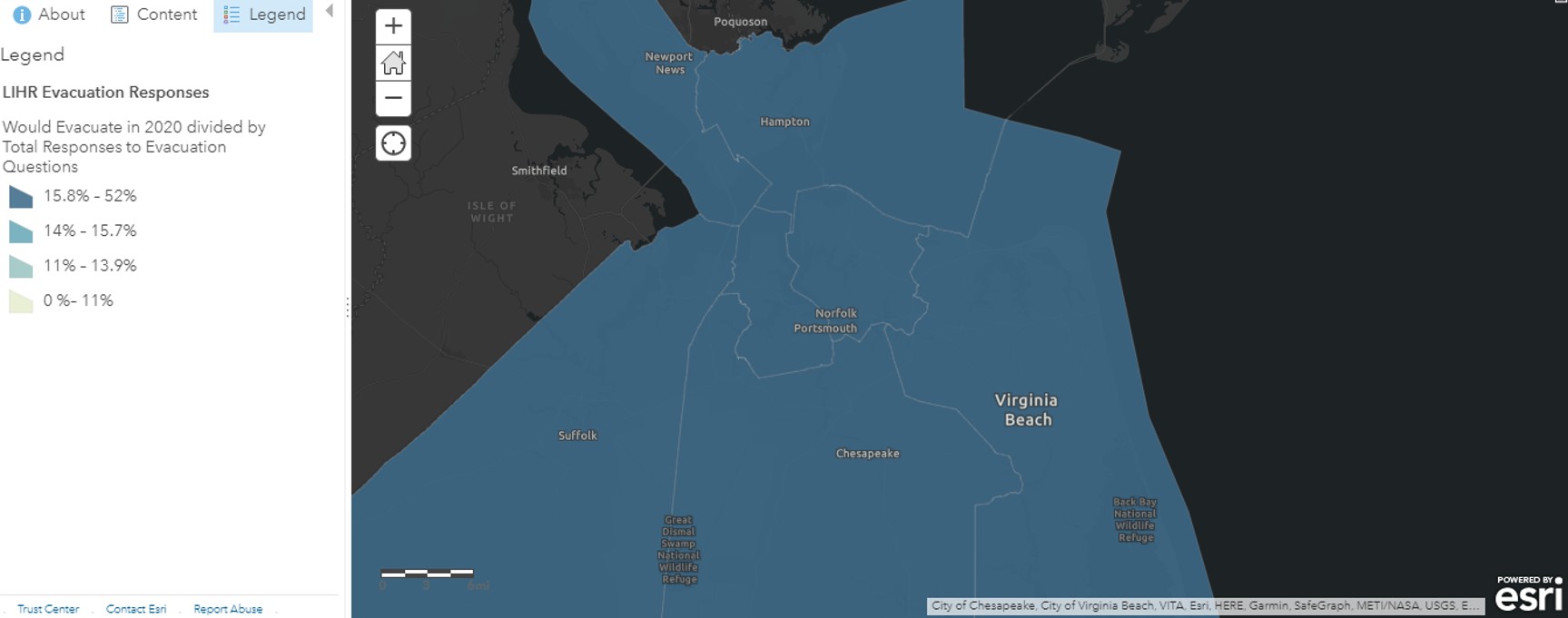

2020 Life in Hampton Roads Survey

The influence of COVID-19 upon demand for evacuation and sheltering services was assessed through the 2020 Life in Hampton Roads (LIHR) survey. The ODU SSRC developed and conducted the survey between June and July 2020 to gain insight into residents’ perceptions of the quality of life in Hampton Roads during the COVID-19 pandemic. The dataset included 1,100 online surveys completed by residents of the seven Hampton Roads cities identified above. Two different panels—one from Qualtrics and a proprietary SSRC panel of previous LIHR survey participants from 2014-2019—were used to solicit respondents to complete the web-based survey. The data files were weighted to correct for discrepancies in age, race, gender, and internet usage between the survey sample and the population of each Hampton Roads city. Data were also weighted on city of residence to maintain the representativeness of the sample with regard to the population distribution in Hampton Roads. Statistical analysis included percentages and crosstabs generated from SPSS to identify expected behaviors and the influence of financial hardship and fears of COVID-19 transmission upon them. Geospatial analysis was conducted for questions about intended evacuation and sheltering behavior during the 2020 hurricane season.

Hurricane-Pandemic Workshops

Population and transportation vulnerability expectations during the 2020 hurricane season were assessed from the CONVERGE Hurricane and Pandemic Working Group Workshops’ After Action Reports. These six workshops were convened in May and June 2020 by researchers at ODU and the University of South Florida. The 265 total participants were recruited from a national convenience sample of stakeholders involved with emergency management, public health, and human services through government, nonprofit, and academic roles. Attendees self-selected to attend one or multiple workshop(s) depending on topic (i.e., vulnerability, logistics, work force, mental health, infection control, and messaging). Each workshop was split into breakout groups of 12 to 18 participants to respond to a semi-structured questionnaire. Transcripts of the workshop recordings were analyzed qualitatively for emergent themes.

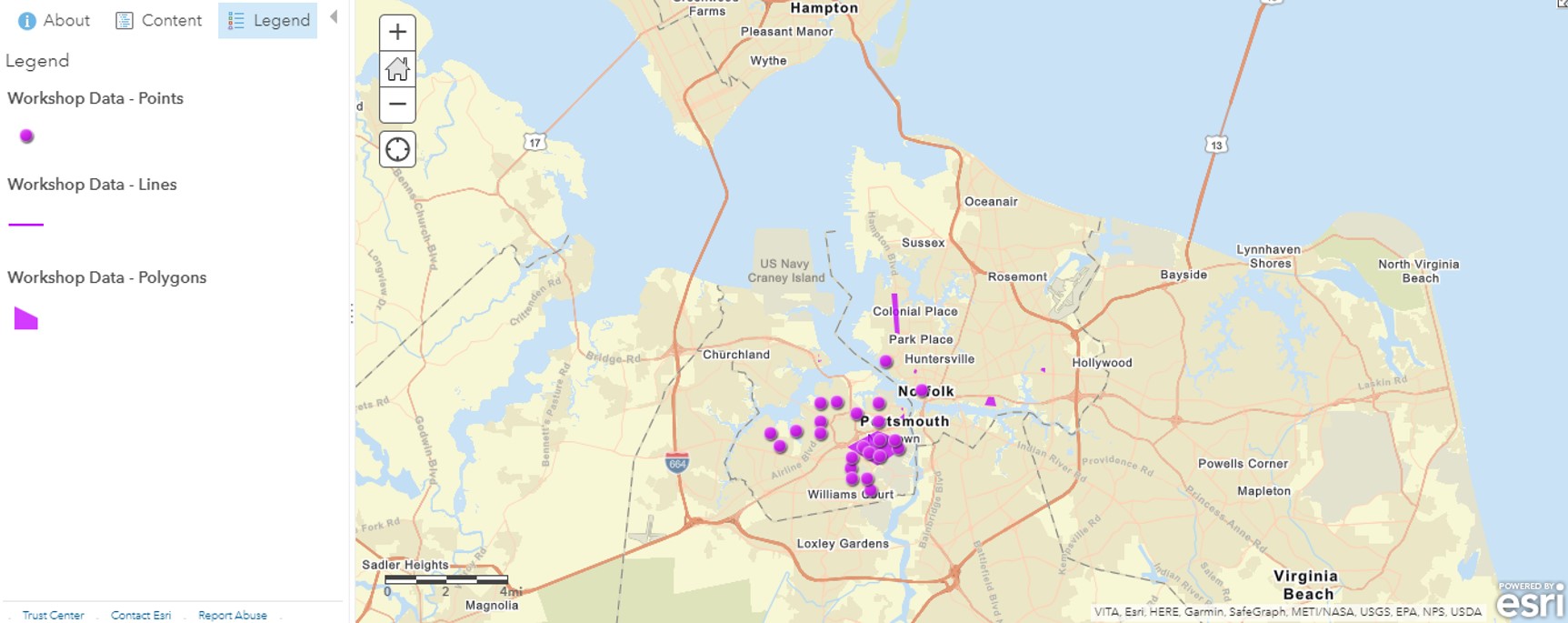

Webapp Development

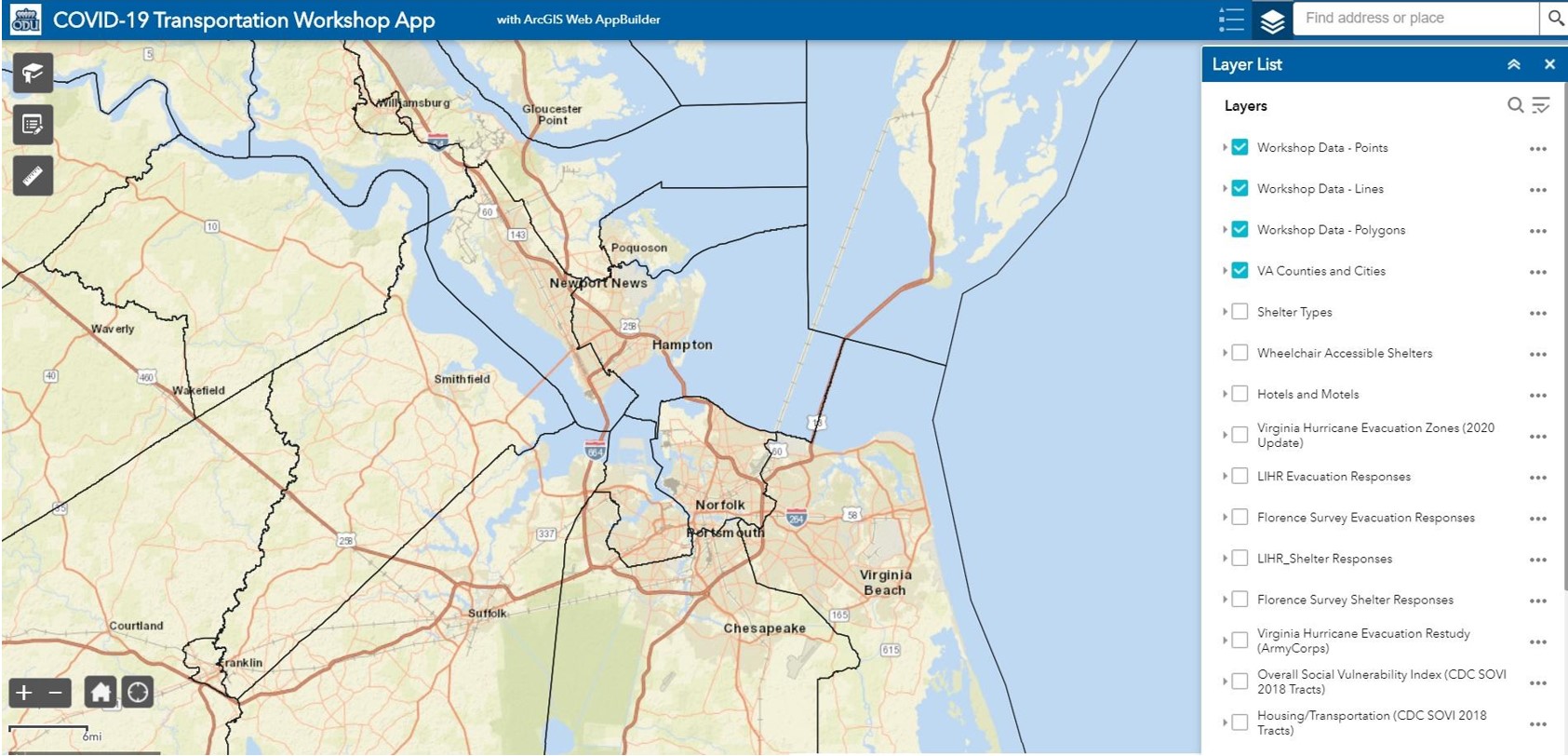

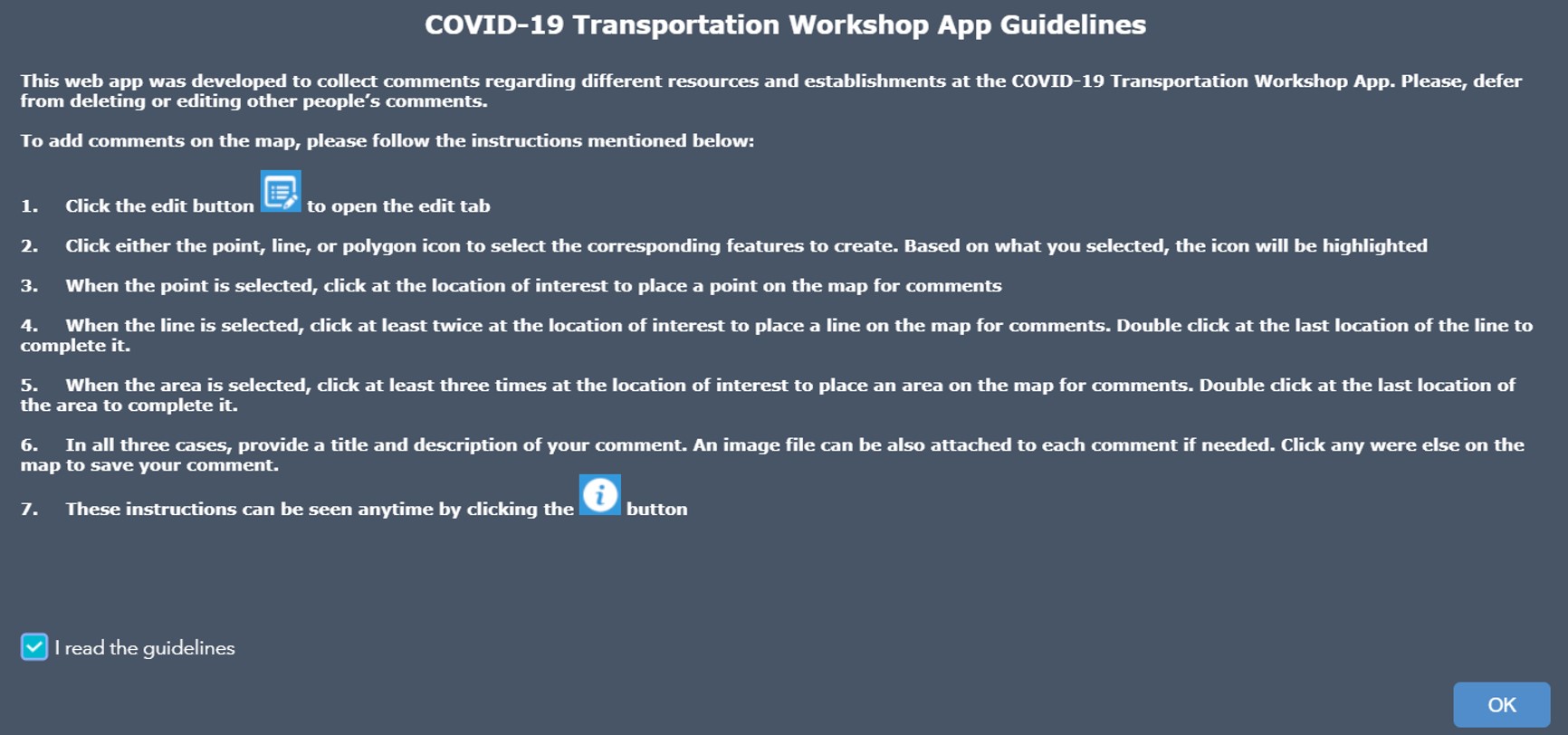

The COVID-19 Transportation Workshop App (Figure 1) was developed using Esri’s Web AppBuilder Application Programming Interface (API) for this study to allow users to identify areas of concern along roadways and transit changes needed to accommodate shifting vulnerabilities and behaviors. Twenty-nine data layers related to vulnerability, behavior, and infrastructure are included at national, state, regional, and local scales through the Layer List menu. Appendix 1 provides a comprehensive data dictionary. Users were provided the functionality to: (a) zoom in and out, (b) search for particular locations, (c) view the legend, (d) turn on and off data layers, (e) bookmark different map extents, (f) measure linear distances, (g) identify location coordinates (i.e., latitude and longitude), and (h) create new features (i.e., draw points, lines, or polygons). Figure 2 shows the instructions provided and agreement required prior to opening the web application.

Figure 1. COVID-19 Transportation Workshop Application

Figure 2. Application Guidelines

Transportation, Vulnerability, and COVID-19 Focus Groups

ODU researchers convened two online focus groups in September 2020 to identify policy and resource changes needed to adapt the transportation system for evacuation and sheltering options during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were recruited from CONVERGE Workshops registration lists. Twenty-seven participated in the local focus group and 23 in the national group. A presentation of data from the Florence Survey, LIHR Survey, and Converge Workshops, including a demonstration of the COVID-19 Transportation Workshop App, was provided. A predetermined set of questions guided discussion about the utility of the shared data and how resource and policy needs had shifted throughout the 2020 hurricane season. Transcripts of the focus group recordings were manually coded based on vulnerability indicators and evacuation procedures from the literature and resource needs and operating options that emerged from the responses to generate themes and identify relationships between them.

Dissemination of Findings

Visualizations of changing demand and resources based on survey analysis and focus group input into the COVID-19 Transportation Workshop App were integrated into a publicly accessible ArcGIS StoryMap. The visualization complements a sector-specific timeline for adaptation based on the evolving understanding of the virus, role of transit workers in transmission prevention, and resource availability, as articulated in the CONVERGE Workshops and Transportation, Vulnerability, and COVID-19 Focus Groups.

Findings

Results present exploratory findings from a case study of changes in demands for evacuation and sheltering assistance in Hampton Roads and benchmarks derived from stakeholders operating from local to national scales for understanding and adapting operations to account for redistributed vulnerabilities in the post-lockdown/pre-vaccine timeframe.

Florence Survey

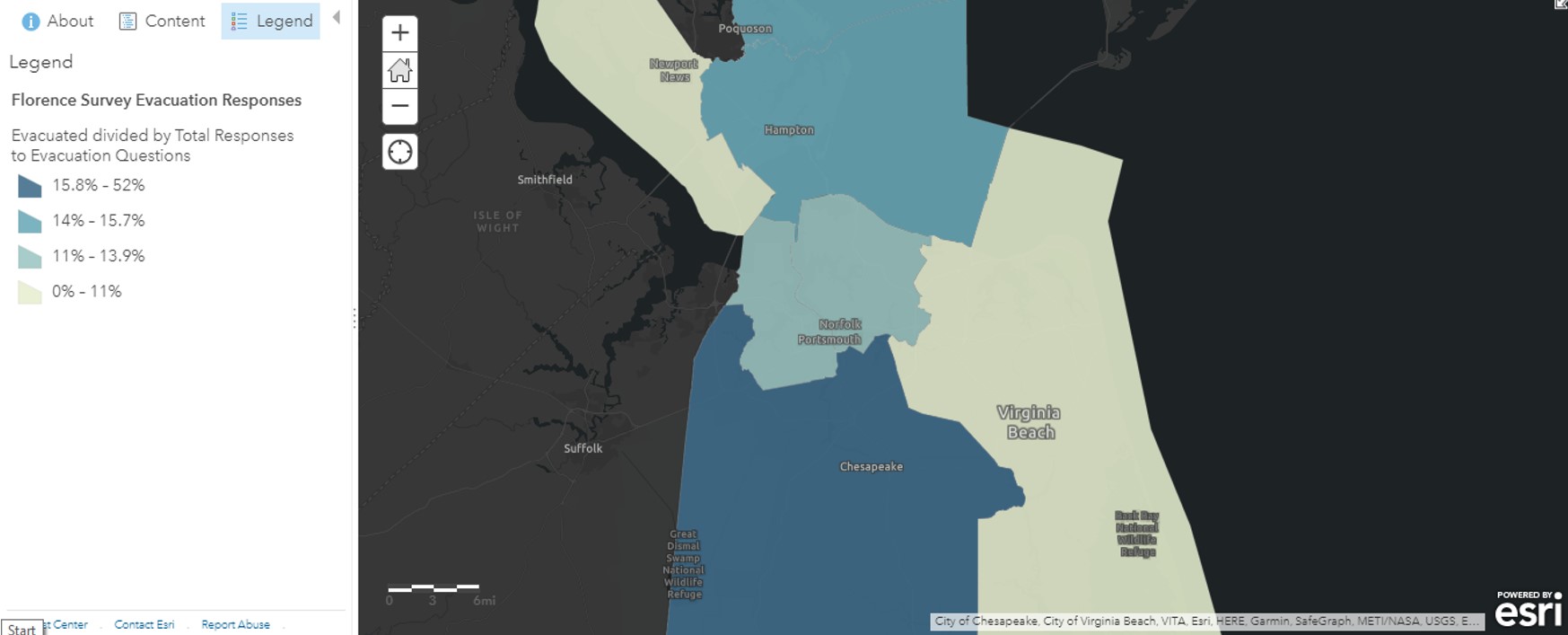

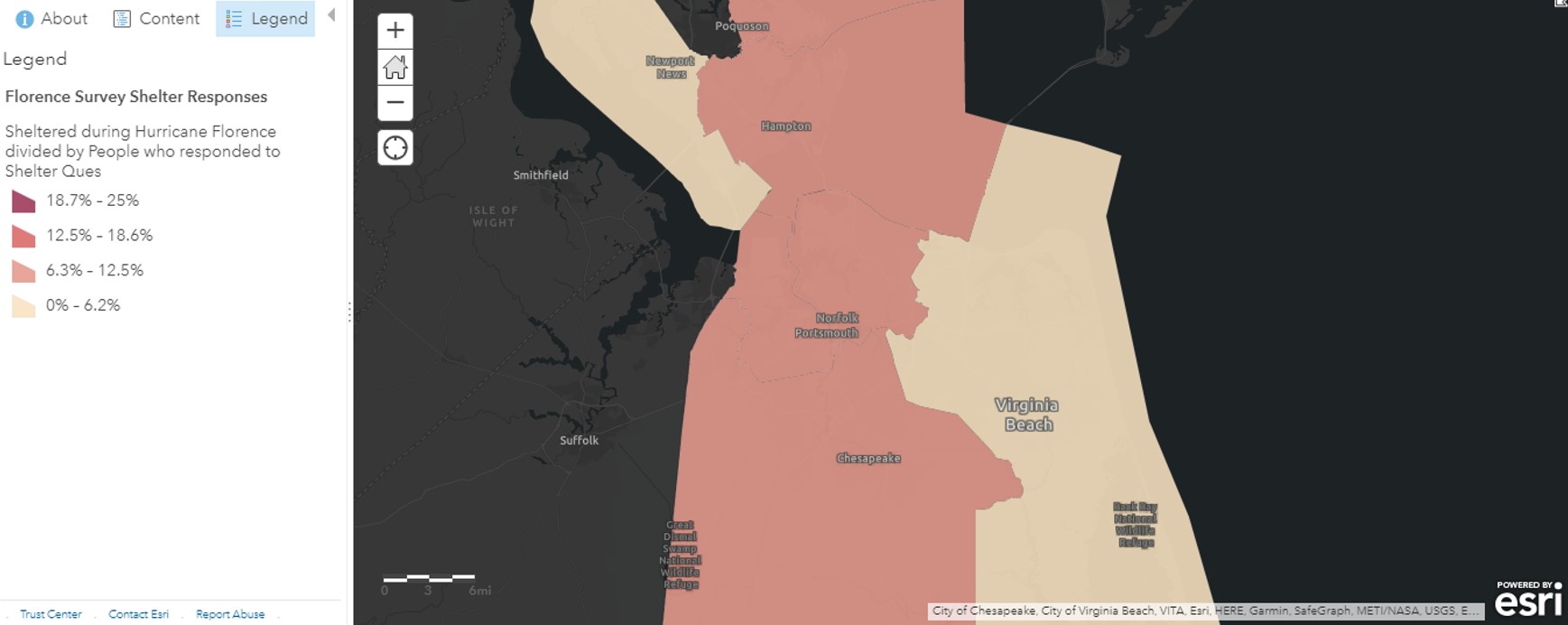

Virginia Governor Ralph Northam issued an evacuation order in 2018 for low-lying areas identified as Zone A prior to Hurricane Florence’s arrival. Forty percent of respondents lived in Zone A. Twenty percent of Zone A residents evacuated outside Hampton Roads, and 14% stayed at a place other than their residence within Hampton RLIHRoads. Of those who stayed in Zone A,16% reported caring for a person with a medical condition, 9% cost, and 2% no transportation access as the reason for staying. Eighty-six of the total survey respondents stayed in Hampton Roads, whereas 13% evacuated. Of those who stayed in Hampton Roads, 7% sheltered somewhere other than their residence within Hampton Roads. Figures 3 and 4 show the breakdown of total respondents deciding to evacuate or shelter. When those who stayed were asked directly about the following as being their primary reason, 15% reported caring for a person with a medical condition, 10% cost, and 3.5% no transportation access. Although the overall percentage of evacuation for the region was lower than in Zone A, some residents outside Zone A did evacuate without a mandatory order. Of those evacuating outside Zone A, the propensity to shelter somewhere other than the primary residence was reduced by half. The locations chosen require additional analysis to inform planning decisions about type and distribution of shelter options.

Figure 3. Florence Survey Evacuation Responses

Figure 4. Florence Survey Sheltering Responses

The reasons for staying were similar for Zone A and other residents. Transportation access was a higher consideration by 1.5% or three quarters within the region compared to Zone A. Providing transportation and sheltering options for the medically fragile remains a priority for emergency planners, but the amount and type of shelter and transportation available may change during COVID-19. Additional information is needed to identify how concerns about virus transmission to individuals with medical conditions and the medication/healthcare-dependent influence household decision-making. Additional information is also needed to identify how the financial implications of COVID-19 may change the need for local evacuation and sheltering options. Further, planners should consider income constraints when determining if personal protective equipment (PPE), sanitization, and non-congregant meals will be provided for users of public evacuation transportation and shelters. Finally, the variance in transportation access should be of concern to emergency planners when determining how to distribute public transit services.

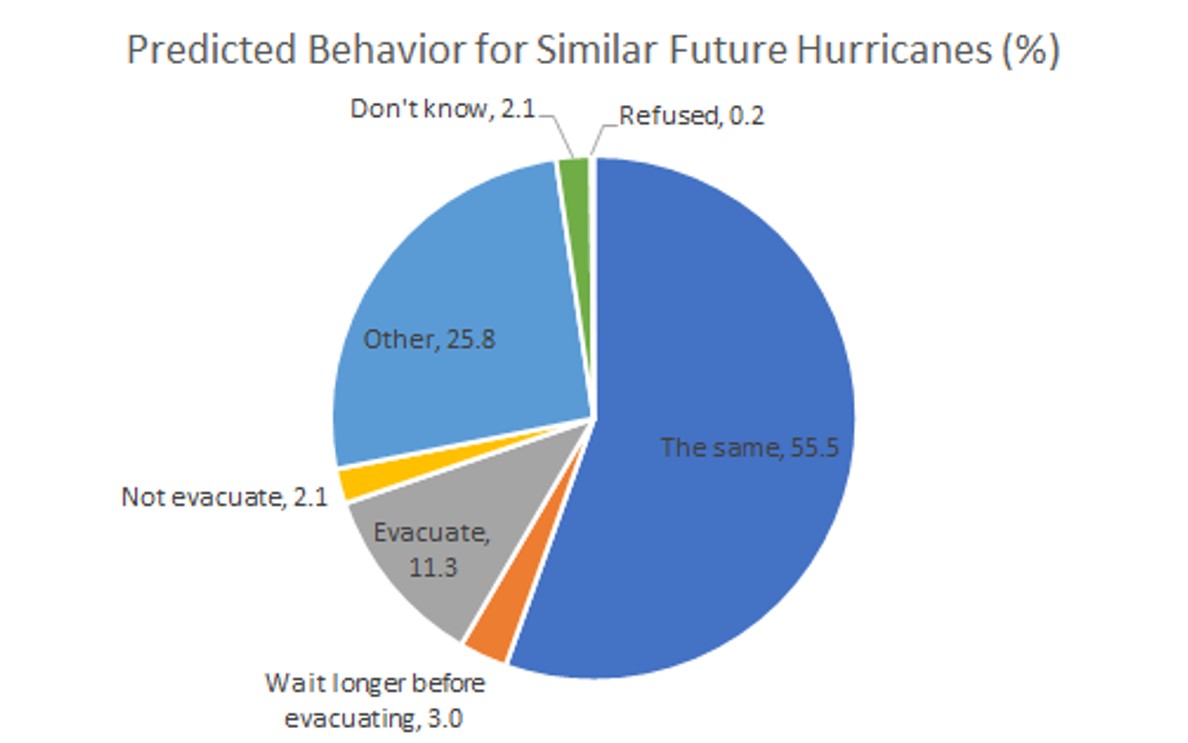

Figure 5 shows predicted future behavior. Fifty-six percent of respondents would not do anything different in the event of a similar future storm; 24% of total respondents had evacuated for past storms, and 76% did not. Fewer evacuated for Hurricane Florence than had for past storms. Differences in risk perception, responsibilities, or resources may have played a role. Although 40% of both Zone A and regional residents chose not to evacuate for Hurricane Florence because of low perceived risk, an additional 11% planned to evacuate for similar future storms that did not in 2018. This increase in planned evacuations is relevant to planning during the 2020 hurricane season. Additional information is needed to determine if the perceived risk of COVID-19 will alter individual and household evacuation intentions.

Figure 5. Future Behavior Predictions—Florence Survey

Life in Hampton Roads Survey

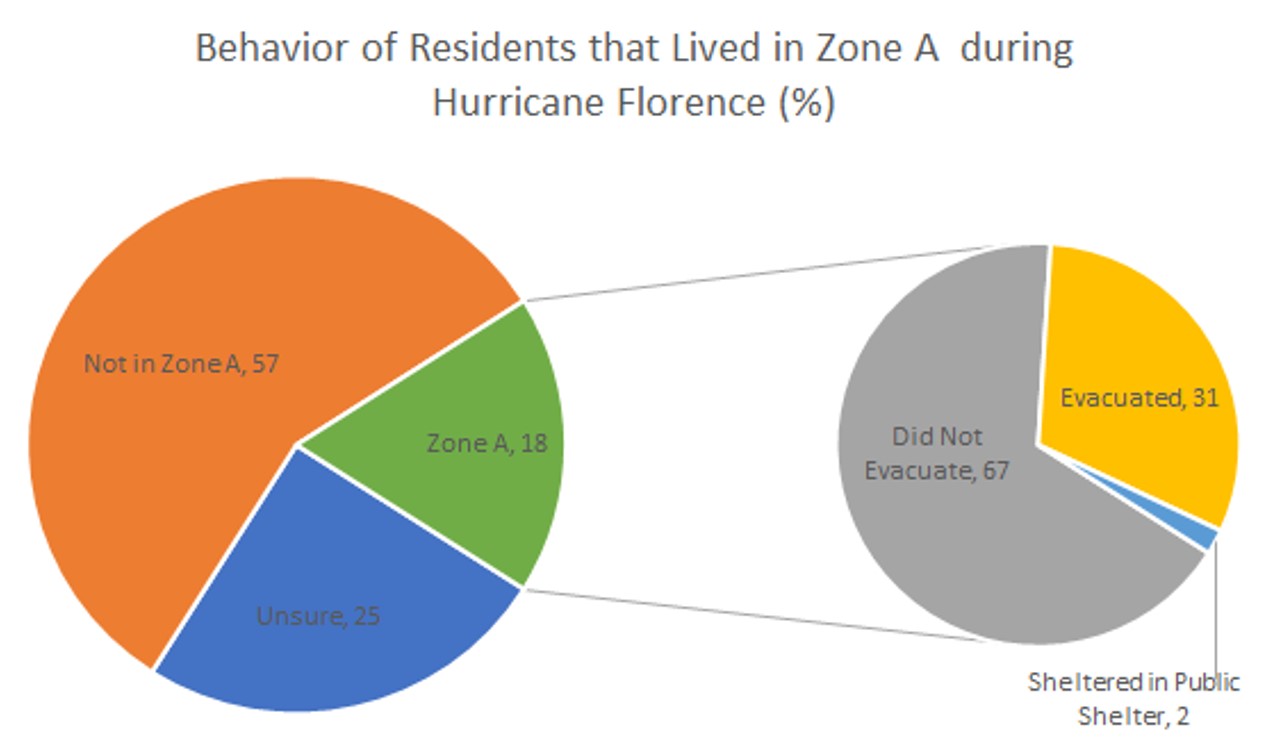

The 2020 LIHR survey assessed evacuation and sheltering decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to Hurricane Florence. Eighteen percent of respondents lived in Zone A during Hurricane Florence; 31% evacuated and 2% went to a public shelter (Figure 6). In comparison, the Florence survey showed 20% evacuated outside Hampton Roads and 14% sheltered somewhere other than their residence. The discrepancy may indicate that the higher percent who reported evacuating and lower percent willing to go to public shelter in the LIHR survey represent evacuations within Hampton Roads to friends’ and relatives’ homes or hotels. If that is the case, these percentages of the population are of interest to planners of mandatory evacuations during COVID-19 because local evacuation is the type of behavior being promoted to reduce virus transmission outside the region. Those that evacuated outside the region require additional messaging to modify that behavior, and those that typically evacuate locally should be accounted for in transportation and non-congregate sheltering plans. Additional analysis of the whole region follows to account for shadow evacuations.

Figure 6. Zone A Residents Compared to Total Participants and Past Evacuation Behavior—Life in Hampton Roads Survey

Table 1 shows the intended behavior of those who evacuated from Zone A during Hurricane Florence. Seventy-two percent would consider doing the same in 2020 and 3% were unsure. The intent to evacuate for a similar storm in 2020 far exceeded the actual evacuations in 2018. Table 2 shows the influence of financial limitations and virus transmission fears upon decision-making in Zone A. Of those that evacuated for Hurricane Florence but would not in 2020, 73% cited insufficient cash or credit on hand as a contributor to the decision. Also of those respondents who evacuated, 50% would consider going to a public shelter in the 2020 hurricane season. Of those who would not consider going to a public shelter, 70% reported concerns with virus transmission. Forty percent of those who went to a public shelter in 2018 would consider evacuating in 2020, and 20% were unsure. All those who would not evacuate but previously went to a public shelter reported insufficient cash or credit on hand. Of those who went to a public shelter, 60% would consider doing the same, and 40% were unsure. The concern of virus transmission was not calculable for those who sheltered during Florence because none said they would definitely not do the same again. Of those who did not evacuate in 2018, 44% would not evacuate during 2020 either, and 12% would consider going to a public shelter. Of those who did not and would not evacuate, 28% cited insufficient cash or credit on hand. Of those who did not evacuate and would not go to a public shelter in 2020, 64% cited concerns about virus transmission. An average of 59% would do the same thing in 2020 as 2018.

Table 1. Behavior in 2018 Versus in 2020 (%)

| Zone A | Would Shelter | Would Not Shelter | Unsure |

| Did Not Evacuate | 12 | 75 | 13 |

| Did Evacuate | 50 | 43 | 7 |

| Shelter in a Public Shelter | 60 | 0 | 40 |

| Zone A | Would Evacuate | Would Not Evacuate | Unsure |

| Did Not Evacuate | 29 | 44 | 27 |

| Did Evacuate | 72 | 25 | 3 |

| Shelter in a Public Shelter | 40 | 40 | 20 |

Table 2: Influence on Behavior in Zone A (%)

| No Because Not Enough Cash or Credit | Yes | No |

| Did Not Evacuate | 28 | 72 |

| Did Evacuate | 73 | 27 |

| Shelter in a Public Shelter | 100 | 0 |

| No Becaues of Possible COVID-19 Exposure A | Yes | No |

| Did Not Evacuate | 64 | 36 |

| Did Evacuate | 69 | 31 |

| Shelter in a Public Shelter | 0 | 0 |

Forty-five percent of total LIHR respondents would consider evacuating if a major hurricane threatened Hampton Roads during the 2020 season, 29% would not, and 26% were unsure. Figure 7 shows the breakdown of respondents deciding to evacuate. Comparison of actual behavior during Hurricane Florence and intention for a similar storm in 2020 shows a much higher intent (42% to 53%) to evacuate than previously occurred (10% to 16%). Of those who would not evacuate, 30% reported that the answer was at least partially due to financial concerns. Eighteen percent of total survey respondents would consider going to a public shelter, 63% would not, and 19% were unsure. Figure 8 shows the breakdown of respondents deciding to go to a public shelter by city. Although the intent to go to a public shelter in 2020 (15% to 25%) is higher than those reporting sheltering in a location other than their home for Hurricane Florence (3% to 11%), a direct comparison is not possible because the number of people who sheltered in a public shelter was not collected in the Florence survey. Of those who would not consider a public shelter, 70% stated that concerns about exposure to COVID-19 at least partially influenced their response. Non-congregant shelter options may be needed to address these concerns for those who may have financial limitations restricting evacuation. Exposure concerns that may reduce public shelter use are not necessarily related to a household member with an underlying medical condition, but it is possible that COVID-19 fears may have the opposite effect that medical fragility had during Hurricane Florence, when it contributed to the decision not to evacuate for 15% to 16% of residents. Additional information about and planning to accommodate changing behavioral factors is needed.

Figure 7. Life in Hampton Roads Survey Evacuation Responses

Workshops

The CONVERGE Workshops participants sought ways to be more strategic, to triage, and to work within resource limitations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Government budget constraints and furloughs, layoffs, and hiring freezes reduced the availability of transportation and shelter staff. Despite that, evacuation and sheltering during COVID-19 were expected to require expanded public transit and shelter facilities to maintain social distancing and allow for space to quarantine. Additional staff, skilled health workers, sanitization supplies, PPE, mental health resources, and training for new cleaning protocols were thought to be necessary. Participants suggested outsourcing transportation resources and bringing in staff from other organizations, regions, and states to assist in evacuation procedures and account for burnout.

In addition to facilities, staff, and partnerships, health and safety protocols were of interest to maintain critical services and accommodate vulnerable populations, including staff. Participants determined that existing socioeconomic vulnerabilities were exacerbated by COVID-19 and additional vulnerabilities based on underlying health conditions had emerged. Populations commonly served by public sheltering and evacuation, such as families with pets, the disabled, caretakers, and group housing facilities, were of additional concern due to COVID-19. Participants also questioned how the financial impact of lockdowns might change the amount of people requiring transportation, utilizing public shelters, or ability to evacuate.

Participants desired revised guidance for what supplies are needed to prepare and who should evacuate and shelter based on COVID-19 risk. Shadow evacuations in particular were not desirable. Sheltering with family and friends outside of evacuation zones was preferred to long evacuations. Wider use of registries for public transit and shelters was proposed to ensure sufficient space for the number of people and accommodate those who self-report as COVID-19 positive or symptomatic. The extent of separation available for sick individuals and families remained unclear but alternative arrangements were of interest.

PPE would be required on buses, but participants expressed concern regarding how operators might communicate and enforce this requirement safely. Physical barriers on buses and air filtration systems were being considered. Review of existing transportation and supplier contracts was suggested to ensure companies could comply with new guidelines, had operational equipment, and were still in business. Participants were concerned that timelines for evacuation could be extended beyond the traditional window because buses would be expected to make multiple trips to transport evacuees; drop off users at alternative shelter locations or pick them up at an expanded number of sites to reduce the density of individuals waiting; and sanitize between rotations. New and expanded partnerships as well as non-congregate options such as Uber and Lyft were also being considered to supplement public transit.

Focus Groups

Consistent messaging and outsourcing allowed policies and procedures for evacuation transportation during COVID-19 to gain traction by the peak of the 2020 hurricane season. Although focus group participants expressed consistent preferences for local evacuations, it was evident that public sheltering was still needed. Concerns about capacity with social distancing, timing, registration, and enforcement remained. Participants noted that most states have a registration system, at least for medically fragile individuals and those with pets, which could be expanded. Participants debated if police were appropriate for protocol enforcement or might deter vulnerable populations from accessing public evacuation and sheltering assistance. Who would enter registry information and the availability of staff training for protocol enforcement beyond document circulation remained unclear.

Registration and other COVID-19 measures were expected to take additional time. However, experiences with timing of evacuation orders during the 2020 hurricane season varied. Participants recalled and were concerned about the potential for more instances where officials waited until the last minute to order an evacuation in hopes of a non-event or to avoid congregate settings, thereby inundating roadways with vehicles. Participants expressed confidence in existing infrastructure to communicate evacuation orders and sheltering options, but consistent messaging between jurisdictions was desired for those who might still evacuate across local or state boundaries. One participant suggested a ‘disaster czar’ to make final decisions in a timely manner. In part, this was thought to be necessary because lockdowns are political, administrations change, resources are limited, and there is disagreement amongst jurisdictions regarding COVID-19 safety requirements.

Despite disagreement between localities about mask requirements while sleeping in public shelters, it was widely accepted that masks are needed to protect staff and volunteers. Several supply chain and enforcement issues had been resolved by the peak of the hurricane season. Participants reported that PPE stockpiles were available or being collected in spite of ongoing strain; sharing arrangements were used where available and expansion was of interest. Some areas made the evacuee responsible for bringing PPE and meals to the evacuation destination, congregant or non-congregant. The capacity of low-income individuals and families to afford or source supplies concerned some participants.

Participants in multiple states explored contracts with hotels. While shelter staff costs may be reduced through non-congregant options, costs for accommodation could vary depending on each hotel’s policy. For example, some hotels required an entire floor to be purchased to accommodate COVID-19 positive individuals. One participant noted that a statewide survey of hotels found a low percentage willing to provide public shelter. Further, hotel limitations including flood zones and low density (e.g., in rural areas) required the inclusion of bed and breakfasts, Airbnbs, and campgrounds as shelter options.

Some participants had established new or expanded transportation options to friends’ or family’s residences or shelters. One participant shared that current state plans included two non-congregant options: (a) sending voucher codes for individuals and households to book their own Lyft, Uber, or other contracted ride-sharing provider, and (b) booking the ride for the individual or household in the ride-share portal. However, participants reiterated that individuals with COVID-19 symptoms, disabilities, and pets still require public transportation options for evacuation. Another participant shared the results of trying to include public school buses for congregant transportation while schools are virtual, wherein schools were hesitant to allow access. This was not unexpected since public schools were also backing out of shelter contracts. Although a shift to non-congregant options would reduce the need for bus operators, concerns with worker fatigue and attendance remained because social distancing would still increase the number of trips, and public-facing operators have high exposure risk even with PPE requirements.

While HURREVAC remained useful during the pandemic to predict timelines and resource mobilizations based on unique storm characteristics, the consensus was that modeling options could be improved by integrating static information about roads that flood prior to a storm and additional real-time information about counterflow measures, closures, traffic, weather forecasts, supplies, staffing, and rideshare availability. For example, participants identified low response census tracts, public housing units, pick-up points, parking garages used to temporarily park vehicles above flood waters, and areas with frequent flooding as locations in need of additional attention in evacuation and shelter planning using the COVID-19 Transportation Workshop App (Figure 9; StoryMap). One participant remained conflicted, stating that these features could negatively brand frequently flooded areas. Another expressed concern regarding staff and data limitations to do real-time analysis of emergent events, such as COVID-19 or events with short return periods like 25- or 50-year floods to complement travel demand models. Resource redeployment once limitations and problem areas are identified was proposed as an alternate use. Some participants suggested additions—for example, crime, food banks, childcare centers, mental health services, COVID-19 infection rates, or expansion to broader areas to show inter-jurisdictional traffic flows—to account for factors that may influence household evacuation decision-making. Collaborations to generate similar applications were underway in some locations, but participants remained cautious that unless the data and platform were easily updated, accessed, and tailored, they could go unused.

Figure 9. Participant Inputs from Workshop App

Conclusions

Surveys from 2020 show the intent to evacuate and shelter is elevated above previous behavior in Hampton Roads, but COVID-19-related financial concerns are preventing some from considering it. Public shelters remain a refuge of last resort for those who had to shelter before. Households that did not previously use public shelters may be unwilling to go to one because of virus transmission concerns. This indicates that more people with limited resources may remain in high-risk areas during the 2020 hurricane season unless alternative transportation and sheltering options are available.

Although emergency management, public health, and transportation stakeholders had more questions than answers at the beginning of the 2020 hurricane season, understanding of the virus and options for dealing with it during an evacuation were clearer by the peak of hurricane season. The preference for local evacuations, including sheltering with family and friends, was broadly accepted. Pre-registration was determined to be feasible based on existing registries, and safety protocols were largely agreed upon despite some jurisdictional discrepancies. Contracts with non-congregate shelter and transportation options were negotiated as possible, which allowed public resources to adjust for budget and staff strain and accommodate vulnerable populations still in need. Stockpiles and sharing agreements were identified for health and safety supplies but training opportunities on new protocols were not. Safety enforcement options were delegated to law enforcement in some cases and remained unclear in others. Struggles with timing evacuation orders emerged. Additional time for deploying strained resources was desired, but localities were hesitant to order evacuations early in the hopes of avoiding congregant situations. Additional modeling was needed to identify route and pick-up point changes in the case of a local mobilization for specific storm characteristics. A need for coordinating real-time weather, resource, staffing, and traffic information as well as local knowledge with interjurisdictional data was noted. Interest in local application development to include additional health and social service resources was expressed. Vaccine availability and administration changes were anticipated to be the next planning hurdles.

Limitations and Future Research

Study limitations included varied geographic coverage and wording of surveys, as well as distance in time from the most recent evacuation order. First, the cities included in the Florence and LIHR surveys were not identical. Suffolk was excluded from the Florence survey and Poquoson from the LIHR survey. Spatial analysis of behavioral change in these locations consequently was more limited than the other cities. Both were still included in the COVID-19 Transportation Workshop App to provide as much coverage as possible. Second, the Hurricane Florence survey classifies evacuation as outside Hampton Roads and, as a follow-up, at a location other than one’s residence within Hampton Roads, but the LIHR survey asks about evacuation and sheltering in the same question. This discrepancy reduced comparability because interpretation may vary. Third, reported behavior in Zone A varies between the Florence and LIHR surveys. This may be a result of the aforementioned sampling and wording variances or reduced recall. Despite these limitations, this exploratory case study has implications for practice regarding a variety of hazards, such as flooding or fire, compounded with a pandemic.

References

-

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Blaikie, P. M., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2004). At risk: Natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters. Routledge. ↩

-

Bowser, G. C., & Cutter, S. L. (2015). Stay or go? Examining decision making and behavior in hurricane evacuations. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 57(6), 28-41. ↩

-

Hasan, S., Ukkusuri, S., Gladwin, H., & Murray-Tuite, P. (2011). Behavioral model to understand household-level hurricane evacuation decision making.Journal of Transportation Engineering, 137(5), 341-348. ↩

-

Sadri, A. M., Ukkusuri, S. V., & Gladwin, H. (2017). The role of social networks and information sources on hurricane evacuation decision making. Natural Hazards Review, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000244 ↩

-

Deka, D., & Carnegie, J. (2010). Analyzing evacuation behavior of transportation-disadvantaged populations in northern New Jersey (Report 10-1584). Transportation Research Board. https://trid.trb.org/view/910046 ↩

-

Syed, S. T., Gerber, B. S., & Sharp, L. K. (2013). Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. Journal of Community Health, 38(5), 976-993. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2018). 2018-2022 Strategic Plan. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-03/fema-strategic-plan_2018-2022.pdf ↩

-

Liu, H., Behr, J. G., & Diaz, R. (2016). Population vulnerability to storm surge flooding in coastal Virginia, USA. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 12(3), 500-509. ↩

-

Allen, M. J., & Allen, T. R. (2019). Precipitation trends across the Commonwealth of Virginia (1947–2016). Virginia Journal of Science, 70(1). https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/vjs/vol70/iss1/4/ ↩

-

Eggleston, J., & Pope, J. (2013). Land subsidence and relative sea-level rise in the southern Chesapeake Bay region (Circular 1392). United States Geological Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1392/ ↩

-

Hampton Roads Planning District Commission. (2017). Hampton Roads hazard mitigation plan. https://www.hrpdcva.gov/library/view/620/2017-hampton-roads-hazard-mitigation-plan-and-appendices/ ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, & U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. (2020). Virginia Hurricane Evacuation Restudy Summary Report. ↩

-

Ng, M., Behr, J., & Diaz, R. (2014). Unraveling the evacuation behavior of the medically fragile population: Findings from hurricane Irene. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 64, 122-134. ↩

-

Ng, M., Diaz, R., & Behr, J. (2015). Departure time choice behavior for hurricane evacuation planning: The case of the understudied medically fragile population.Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 77, 215-226. ↩

-

Ng, M., Diaz, R., & Behr, J. (2016). Inter-and intra-regional evacuation behavior during Hurricane Irene. Travel Behaviour and Society, 3, 21-28. ↩

-

Behr, J. G., & Diaz, R. (2013). Disparate health implications stemming from the propensity of elderly and medically fragile populations to shelter in place during severe storm events. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 19, S55-S62. ↩

-

Behr, J. G., & Diaz, R. (2014). Hurricane preparedness: Community vulnerability and medically fragile populations. The Virginia News Letter, 90(3). https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=vmasc_pubs ↩

Hutton, N., Whytlaw, J., & Hill, S. (2021). Adapting Transportation to Accommodate Populations Vulnerable to COVID-19 in Hazardous Settings (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 319). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/adapting-transportation-to-accommodate-populations-vulnerable-to-covid-19-in-hazardous-settings