An Assessment of UNHCR Crisis Response of a Rohingya Refugee Camp in India

Publication Date: 2019

Abstract

This quick response research project examines the crisis response mechanisms employed after a fire completely destroyed an urban refugee camp inhabited by Rohingya refugees in New Delhi, India in the early morning of April 15, 2018. Data were collected via semi-structured interviews and participant observation of 11 stakeholders, including those in the international humanitarian aid network and Rohingya refugee leaders. By examining the crisis response mechanisms used by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), this research examines the effectiveness of the response framework that is in place for in-country urban response. Effectiveness was measured by the quickness of emergency response, maintenance of physical security, efforts to address physical and emotional trauma, and recuperation of shelter and livelihoods. Additionally, the author sought to obtain qualitative data on the subjective experience of security and maintenance of dignity as perceived by the refugees themselves. A key motivation of this analysis is to understand how political security is maintained while upholding the dignity and physical safety of refugees in a socio-politically charged environment. Since October 2017, the Indian government has been actively attempting to deport its Rohingya refugee population, creating tension between UNHCR and the central government.

Methodology and Research Questions

The methodology employed attempts to uncover the political security of urban refugees by triangulating the international response of the UNHCR, the domestic response of the Indian state, and the subjective experience of the Rohingya refugees. Over the span of 10 days, the author conducted 11 total interviews: three interviewees were representatives from the UNHCR and their Implementing Partners (IPs)Endnote 1, one interviewee was a major Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) donor for the Zakat Foundation of India (ZFI), and seven interviewees were Rohingya leaders (including three men, three women, and one youth leader). Additionally, the author attended the last in a series of four coordination meetings among all key stakeholders, had informal conversations with Rohingya neighbors who are Indian nationals, and met with international media correspondents. These data will highlight nuances based on Indian domestic policy on refugees and its geopolitical positioning. Finally, this report will offer directional insights on how these findings might be useful to mitigate harm from such disasters in the future.

The common questions asked of the international humanitarian aid network interviewees were: (1) When did you learn about the fire and from whom?; (2) Who organized the response?; (3) What was the response?; (4) What were your organization’s top three concerns; (5) In what ways were political relationships a part of the decision making process?; (6) What are your measures for success in a crisis response?

Rohingya refugee leaders were asked: (1) Tell me what happened; (2) Who responded to the fire first?; (3) What have the UNHCR or the IPs done for you?; (4) What has the Indian government done for you?; (5) What has ZFI done for you?; (6) Which response has been most helpful?; (7) What do you need? What have you asked for?; (8) Do you feel respected in the process?; (9) The media is reporting that it was a short circuit that started the fire, what do you think about that? I will address only the major findings from these interviews below.

Regional Context

The fire was located at a refugee settlement that has received a disproportionate amount of media attention over the past five years. The media’s fascination with this particular space is its accessibility from the main road, its more depraved conditions than many other settlements, and because it is an exclusively Rohingya refugee settlement—all factors that have thrust it into the limelight, thus inadvertently drawing the Rohingya inhabitants into a larger national anti-immigration context.

The Rohingya are an ethnic-Muslim minority group from the western border state of Rakhine, Myanmar. In spite of the fact that the Rohingya people have been living in Rakhine for many generations, the current Myanmar state accuses them of being illegal immigrants from Bengal (modern day Bangladesh and eastern parts of India). For decades, during increased violence, Rohingya have commonly fled to Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and India. Since Myanmar’s turn toward democracy in 2011, the government has attempted to unite its ethnic minorities under the central government; however, the Rohingya continue to be singled out as people who do not belong in Myanmar. Stripped of citizenship in 1982, they have been subject to acts of ethnic cleansing.1 2 The killing of Rohingya escalated in August 2017, as approximately 850,000 Rohingya fled to Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh.

Currently there are approximately 17,500Endnote 2 Rohingya refugees in India. The first major influx of Rohingya refugees into India occurred in 2012 following heightened violence in the Rakhine state after the rape and murder of a Buddhist woman. Although the culprit was never found, accusations were enough to bring violence to an already tension-filled region. Because Bangladesh was no longer registering Rohingya refugees during this time, many Rohingya fled to India. In New Delhi they underwent a Refugee Status Determination (RSD) process that legally acknowledges an individual as fleeing persecution, granting them official refugee status, and thus access to international protections under the UNHCR.

Although the UNHCR office in India began registering the Rohingya, it is important to understand that India is not a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention or the 1967 Protocol. Furthermore, India has no national refugee laws that hold the state accountable for treating refugees in accordance with the standards laid out by the UNHCR. In spite of this, India has historically invested in infrastructure, administration, and international partnerships to aid refugees who have entered Indian territory, including Tibetans, Sri Lankans, Afghans, and Burmese. However, in the modern-day geopolitical climate of anti-immigration and heightened Islamophobia, India too is affected by biases based on these discriminations. Presently, India is experiencing an era of right-wing conservatism led by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that challenges the foundational human rights in its constitution, thus also threatening the plight of refugees. Media coverage of increasing violence against Muslims demonstrates how the political security of migrating Muslims, such as the Rohingya, is in danger, as xenophobia and Islamophobia are supplanting democratic values.

In October 2017, India’s Supreme Court began hearing a Public Interest Litigation case filed against Rohingya refugees by Home Affairs Minister Kiran Rijiju. Rijiju is demanding that all Rohingya Muslims be deported back to Myanmar due to national security concerns. This is in direct violation of Article 21 of India’s Constitution, which protects the human right to life. It is also in violation of various pledges of commitment to the United Nations Human Rights Council and the customary law of non-refoulment, which states that a person fleeing persecution from a state may not be sent back to their country of origin. This case is still open before the court; it has, however, split public opinion, making the situation for Rohingya refugees in India precarious. Liberal media outlets write sympathetic reports detailing the horrors of refugee life; conservative media labels them as a threat to the nation with plans of a hostile Muslim takeover; religious Islamic media portray them as pious victims of India’s historic dejection of Muslims. Objective reporting is in the eye of the beholder.

Fires at refugee settlements are not uncommon. Families use individual gas tanks to fuel small stoves for cooking. Their shanties are made of bamboo, scrap board, and tarpaulin—all highly flammable materials that could be set alight by discarded cigarettes or stove kindling. Electricity tends to come from a highly unstable series of thin wires and exposed outlets strung in and out of individual shanties. The April 2018 fire started at 3:30 a.m., at a time when no one was cooking, nor were light switches being flipped on and off. Was it arson? Was it an electrical short?

Days after the fire, a BJP youth wing leader claimed credit for the fire. He proudly took to Twitter, calling the Rohingya community “terrorists.” This angered the local Muslim community, but made Hindu-conservatives proud. No one I spoke with believes this young man committed arson; it was simply a political posture. What everyone is certain of is that this small refugee space (no larger than two-basketball courts) is bringing immense pressure to an already tension-filled socio-political climate, and Rohingya lives hang in the balance.

First 72 Hours After the Fire

The first 72 hours after the fire were critical in establishing refugee protection. The following is an account of events created by merging interview data to provide a comprehensive timeline of events

At 03:00, the fire began in the southeast corner of the settlement, near the common toilets. Various Rohingya individuals called the police. Two fire brigades arrived by 03:55. The fire burned fast and swift, engulfing the entire settlement of 47 shanties within 30 minutes. Additionally, each home had a small- to medium-sized gas tank for cooking; five gas cylinders exploded during the fire. It took eight fire brigades five to six hours to put out the fire completely.

In between 07:00 and 08:00, Delhi University and Jamia Millia Islamia University students arrived with breakfast and water; a Rohingya refugee youth leader with vast social capital had enlisted their help. A small group of eight Indians from surrounding shanties came by to donate clothes and hijabs for the women. Afghan youth also came to provide support and supplies. It was not until approximately 08:00 that representatives from Don Bosco Ashalayam, an IP and Indian NGO with a focus on education and healthcare, arrived. Representatives from another IP contracted to address legal issues, the Socio-Legal Information Centre (SLIC) and the UNHCR followed soon thereafter.

The Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) of Okhla, Amanatullah Khan, catalyzed first responders from the Delhi Disaster Management Authority (DDMA). At this point, the UNHCR played a secondary role. The UNHCR holds that “the primary responsibility to protect refugees rests with the state. Coordination of the refugee response is determined by capacity and approaches of the host government and builds on resources of refugees and hosting communities.”3 Delhi’s Civil Defence volunteers arrived with temporary shelter tents, a medical tent, meals, water, and mobile toilets. These necessities were provided for three to seven days. Additionally, a bulldozer was sent to level and clear out the debris from the fire. The MLA also promised 25,000 rupees to each family for rehabilitation. Khan represents the Aam Aadmi Party, a popular party among minorities and more liberally minded citizens who oppose the current Hindu-nationalist ruling party, the BJP.

The UNHCR and Rohingya refugees alike were pleased with the government response, mainly because it was unexpected. Given the precarious relationship between the Rohingya and the central government, any level of government support was met with astonishment. The Rohingya were excited to hear they would be receiving compensation; however, three weeks later, when they had not received their stipends, they felt forgotten and lied to. According to the UNHCR, the government is trying to figure out how to process the one-time cash assistance proposal. Disbursements made via check or bank transfers are challenging, because refugees are not legally allowed to have bank accounts or state identification.

For weeks after the fire, there was overwhelming support by the local community, which included cash donations to fund the rental of army-grade tents that were erected on government land only meters away from the charred grounds. Every UNHCR and IP interviewee commented on the unprecedented donations and prompt action. This speaks to both the positive relationships the Rohingya community have created during their five years in India, and to the popularity of this particular settlement, encouraged by past media reports.

There were approximately five donation reception areas created by various local NGOs. These intake spaces were for drive-by donations; many university clubs, NGOs, masjids, and individual community members know this particular settlement well. Some NGOs placed banners and boards stating that they were collecting donations on behalf of the Rohingya. IPs and Rohingya alike noted that it seemed these NGOs were in competition with one another, vying to be the “guardians” of the Rohingya.

UNHCR and IP Actions

Within hours, UNHCR began creating a coordination fact sheet. The UNHCR official website lists various emergency response frameworks. The appropriate framework in this case was a country-level Coordination of Refugee Emergencies Guide that employs a partner inclusive platform by using cluster coordination. Kiri Arti, a Senior Protection Officer at UNHCR India, adapted the guide to fit the Delhi context; the information flow chart became a way for all stakeholders to coordinate plans and avoid duplication of goods and services. UNHCR, IPs, government departments, NGOs, and individual donors were all part of the emergency response and rehabilitation plan. Three weeks after the fire, the UNHCR stated that the emergency response was nearly complete, and rehabilitation was next on the agenda.

Four coordination meetings were held with stakeholders, including Rohingya refugee representatives. The amount of donations and services were staggering; for the 225 victims of the fire, the following is a partial list of donated items or paid services: rental of eight mobile toilets, 26 army-grade tents, water supply of 15 liters per person, meals, electric power, dignity kits (including bras, panties, and sanitary pads), milk powder, clothes, new burqas, mosquito nets, bedding, mattresses, bed sheets, buckets, water coolers, kitchen utensils, stoves, gas cylinders, sewing machines, electric rickshaws, refrigerators, vegetable carts, chicken coups, and medicines. Table 1 shows the principal concerns of UNHCR and IP, and their responses and outcomes.

Table 1. Principal concerns, responses, and outcomes of UNHCR and its IPs

| Agency/Organization | Principal Concerns | Responses and Outcomes |

| UNHCR | Loss of life Getting refugees documentation Obtaining headcounts |

There were zero human causalities from the fire. Documents were dispensed to refugees within 48 hours. Heads counts were obtained through the help of refugee leaders; everyone was accounted for. |

| Don Bosco Ashalayam, IP for refugee education and health | Physical safety for refugees Immediate shelter, food, and water Psycho-social well-being of refugees coping with sudden trauma and loss |

Minor burns and injuries were addressed in medical tents provided by DDMA. Shelter, food, and water were provided by DDMA for 3–7 days; thereafter ZFI managed distribution with support from Minorities, Education, and Empowerment Mission (MEEM). Child trauma and Gender-Based Violence (GBV) was observed and addressed by Human Welfare Foundation and Shakti Shalini. |

| SLIC, IP for refugee legal aid | Documents Ensuring refugees were not experiencing violence Ensuring no illegal fundraising was taking place |

Documents were dispensed to refugees within 48 hours. Observations and conversations dispelled any concerns with mistreatment. Positive relationships with the local police department were reaffirmed. SLIC could not prevent fund-raising, but Rohingya leaders were warned not to accept donations. |

| Fair Trade Forum Implementing Partner for refugee livelihoods (Recently obtained contract, so responsibilities were shared among other partners | Addressing loss of livelihoods | List of refugee families, occupations, and losses collected and organized by a Rohingya youth leader. Individual donors and charitable organizations enlisted for assistance. |

The initial and immediate concern of UNHCR and their IPs was to ensure that there was no loss of life and to safeguard against additional harm. For Bosco, safety was defined by ensuring that social workers were present to help the community cope with sudden loss and trauma. The socio-psychological well-being of the Rohingya was important to Selin Mathews, a Project Manager; she requested the presence of child welfare services for four days to help children process the trauma. Within a week, all the children had gone back to school. Additionally, Mathews had Shakti Shalini, a Delhi based NGO that works specifically on issues of gender-based violence, come for five days to address issues of domestic violence that had arisen within the community.

The major concerns of SLIC were legal in scope. Immediately, they organized to observe police treatment to ensure that there was no mistreatment or harassment. Once they establish that the police were indeed sympathetic, SLIC met with police authorities to offer support and to file a First Information Report (FIR) so that an investigation into the fire could be launched. SLIC also initiated a head count to ensure that there were no missing children and that all adults were accounted for. The resulting list allowed SLIC to reprint refugee identity cards within 48 hours. “SLIC did a very good job regarding our refugee cards,” said one of the camp leaders. “It’s the only proof we have that we’re refugees.” UNHCR representatives stated that because of the open deportation case against the Rohingya, they had to act swiftly to ensure that refugees could demonstrate that they were documented.

The challenge in Delhi was not the lack of resources or goods to rehabilitate the refugees, but equitable allocation and timely reconstruction of homes on the original plots of land. With monsoon season looming, refugees wanted to return to their old space with the promise of new waterproof, fireproof shanties. Reconstruction, coordinated by the ZFI, proved to be challenging. Ninety days later, the new homes had not been erected. The Rohingya are situated in a peri-urban space prone to flooding, thus the local government does not permit residential building. Additionally, the plot of land sits at the border of two states, and ownership is being disputed, severely delaying reconstruction.

Rohingya Perspectives

The Rohingya perspectives are quite different from the top-down account of events. This is where the gap in response lies. There are two major issues that surfaced from the findings: basic communication and the absence of a vetting process or management of local NGOs.

The lack of basic conversations with the community led to misperceptions about the UNHCR and IP role in the emergency response. Unanimously, every Rohingya leader interviewed (n=7) felt they were treated with respect immediately after the fire. Leaders noted that the government, social workers, and NGOs all spoke nicely and counseled them well. One male leader stated that he was worried that his community would regress, but it did not take long for them to recover because of the support. However, the perception of the refugees was that UNHCR representatives were not involved in the recovery efforts. I was told UNHCR never came to visit and that IPs who did come “only came to see;” they did not do anything.

Meanwhile, in the background, the UNHCR and IPs coordinated the emergency response after the departure of the DDMA. While it is understandable that UNHCR needs to maintain a low profile in front of the government and media, when their profile is so low that refugees do not recognize their efforts, it creates a contentious relationship between the international agency and the people they seek to support. Part of the concern is that Rohingya community members, out of desperation, may align themselves with local entities that do not understand the legal intricacies of refugee protection in India. Additionally, this lack of communication leads to low morale within the community.

Historically, India has limited the reach of UNHCR within the state, both geographically and administratively. Currently, their main objective in New Delhi is to manage the RSD process for urban refugees to ensure their protection throughout various states in India. Rohingya and Afghan populations are the largest groups they serve in New Delhi. Contract IPs manage refugee legal matters, livelihoods, education, and health. As IPs, they are vetted through a procurement process that includes ensuring IPs are able to conduct themselves ethically. Under the code of conduct, one warning states: “…procurement of goods and services is an activity that is potentially vulnerable to fraud and/or corruption. As such, Partners must ensure that reasonable measures are in place to prevent, investigate and, if needed, discipline fraudulent actions.”Endnote 3 NGOs wanting to working with refugees do not to go through a vetting process with the UNHCR. As urban refugees, they have the autonomy to accept assistance from whomever they wish. In New Delhi, at least, there is need for a system that ensures “reasonable measures” are in place for refugees to at the very least report mistreatment.

As humanitarian organizations, local Indian NGOs tend to have fewer constraints when assisting refugee populations. They are able to advocate openly without political backlash. However, without proper oversight or training, these guardian-like relationships can place refugees in a precarious position where they are beholden to the mission of local NGOs, which may not be focused solely on refugee protection.

Small local NGOs visit Rohingya communities to provide weekly meals, provide health programming, and to teach Hindi or English. In urban spaces, specifically, host country participation in activities that advance social inclusion helps root the refugee community within the local community. UNHCR India encourages activities that strengthen the capacity of civil society to support refugees. In addition to creating social bridges, local NGOs have the ability to network and reach into their own professional networks to aid refugees. Local involvement allows the UNHCR to maintain a neutral position with the state, because the activities are not UNHCR-sponsored.

When an NGO, such as ZFI, voluntarily steps in to help advocate on behalf of Rohingya refugees, the burden is lifted from UNHCR. In fact, at the final coordination meeting, a UNHCR staff member said, with relief, “Zakat Foundation has adopted the Rohingya from this camp.” Because UNHCR’s mandate is so limited and the Rohingya situation has become highly politicized, it helps UNHCR to have prominent local NGOs take responsibility for the Rohingya refugees. Follow-up interviews after this meeting revealed anger regarding this statement from both humanitarian agencies and a Rohingya representative. The contesting sentiments were that the Rohingya are not abandoned children requiring adoption. They do, however, need benevolent partners to offer guidance and negotiate pathways by extending their social capital, and at times, material goods. Rohingya leaders routinely expressed a desire to be included in decision-making processes, allowing them a modicum of agency.

Currently, the relationship between ZFI and the Rohingya community is strained for three major reasons. First, the rebuilding of their settlement is taking far longer than expected. ZFI owns a large portion of the 1,100 gaz (9,805 square feet) plot that was set ablaze. Endnote 4 Although there are contractors at the site, ZFI is facing territorial disputes with the neighboring state. ZFI claims they have documentation proving that the plot of land is theirs. Some Rohingya claim to know that only 500–600 gaz belongs to ZFI, and that the rest is government land. Delhi’s MLA gave ZFI permission to build upon the land, but Uttar Pradesh claims that it is not Delhi’s to give. Land grabbing in India is a common fear of landowners, who worry that squatter’s rights may usurp their ownership rights. This tug-of-war over a relatively small 4,500 square foot plot is souring the trust of the Rohingya in ZFI to complete reconstruction. Rohingya refugees are not privy to any high-level discussions that take place regarding land ownership; this leaves them feeling powerless and creates a fertile ground for rumors about the disposition of already-tenuous refugee land tenure rights.

Second, the local community has expressed concern over ZFI’s fundraising efforts, questioning if the Rohingya community is receiving the full benefit of donated funds. When I probed locals and Rohingya alike about how much ZFI has raised, estimates varied from 500,000 to tens of millions of rupees. These numbers are all speculative. ZFI is actively fundraising, and states that the reconstruction will cost 40–50 lakh rupees (one lakh is $100,000). ZFI also claims that all donations are listed on their website. The purpose of this research is not to corroborate fundraising efforts. Instead, these acts of defense and accusation demonstrate that the political tension between UNHCR and the state creates a situation in which refugees are left to rely on other organizations whose activities they do not completely understand for social support.

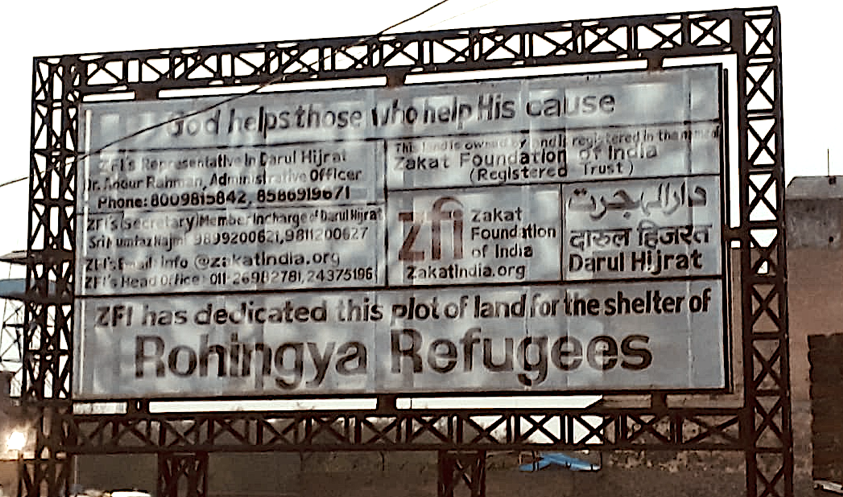

Lastly, humanitarians NGOs, such as ZFI, are not refugee protection agencies. They are not trained to handle the types of situations and sensitivities that are required with politically displaced populations. For example, ZFI erected the following billboard at the site of the fire.

Considering the political climate discussed earlier in this report, and because we do not yet know if this was an act of arson, such highly visible advertising puts the Rohingya community at unnecessary risk of physical harm. ZFI’s lack of technical expertise can also be seen in their outreach efforts to the Rohingya population. ZFI Secretary, Naved Khan, spends hours at the temporary tent community helping to facilitate construction and donations, and supporting the community. His time is primarily with the male leaders, not the common man, and certainly not with the women.

At the coordination meeting, I was told there is a complaint box at the settlement for anyone who wants to communicate with ZFI anonymously. Placing a complaint box for an illiterate population who cannot read and write in their only language, and certainly not in English, is not an efficient means to learn about their needs. When I mentioned this to ZFI, I was told that Khan is present all day, so he could write comments for them. However, this does not make the process anonymous. In addition, the box is inside a tent allocated for worship, a place reserved exclusively for men.

Some Rohingya have called the billboard exploitative; however, ZFI’s intentions are not necessarily directed to self-promotion. It may be that ZFI is gesturing that the land is theirs to drive Uttar Pradesh out. Regardless, UNHCR typically protects refugee populations by helping them attain a certain level of anonymity in the city; this billboard does the opposite.

The Rohingya community’s relationship with ZFI is an important one, but it is only one such example. According to Bosco, shortly after the fire, those who rushed to aid the refugees with food and water brought sugary biscuits for the children, which resulted in several cases of diarrhea. Additionally, one local NGO brought two large containers of water. When one NGO volunteer heard refugee women complaining about the water receptacle, they were given to collect the water, in anger, he toppled over the entire container. Such a violent act further distresses an already traumatized population. The UNHCR should be reducing the risks and impacts of such incidents.

Socio-Political Considerations

This section considers the societal relations with the state and government entities, but also relationships that demonstrate hierarchies of power, including those with Rohingya leaders. The creation, maintenance, and security of these relationships inform the safety conditions of urban refugees. Every UNHCR and IP interviewee maintained that politics bore no consequence on their crisis management, but their actions tell a different story.

Socio-political considerations that affected the disaster response included the following:

- The MLA and DDMA provided the only official government responses. Despite the international attention of the Rohingya situation, the central government remained silent.

- UNHCR and IP representatives met UNHCR guidelines by maintaining a low profile and not interacting with the police or media. Bosco always maintain a low profile because they are a Christian organization, and 90 percent of their beneficiaries are Muslim.

- One of the primary concerns of the UNHCR and SLIC was to reprint UNHCR identity cards immediately to protect the refugees from accusations of illegal status by the central government.

- The first response of SLIC was to ensure that local police were sensitive to the needs of the refugees. Since the deportation case, they have been diligent in touching base with the local police to ensure that their allegiances have not swayed in the direction of the central government.

- Rohingya refugee leaders were told not to accept money from NGOs or individual donors because they did not know the source of the funds. There should not be any link between Rohingya Muslims and any nefarious claims.

- Rohingya leaders were told by SLIC not to give interviews to the media because their case is being heard in India’s highest court. The court appears to be sympathetic, and they do not want to say or do anything to jeopardize this.

- Rohingya leaders were also told by UNHCR at the coordination meeting that they should minimize their interaction with the press and attempt to manage their image given the open deportation case.

- Via participant observation at the temporary settlement, there were many conversations regarding the disparity of who received donor assistance. There were complaints that leaders were helping themselves and their families above others to maintain their power. Some also stated that UNHCR only asked one person to compile a list of losses, and he was biased in his reporting.

- UNHCR, IPs, ZFI, and six out of seven Rohingya leaders all claimed that they did not know how the fire began. Some listed ways it could have happened (e.g., sabotage, an act of god, faulty electrical wiring, or a cigarette) while others said they simply did not know. All understood that assigning blame was not an option; that is a privilege for citizens who are protected by their government. The Rohingya and their advocates remained completely silent on the issue of possible perpetrators.

The central government has created an environment of precarity for Rohingya refugees, specifically. Socio-political motivations are important to understand because they contribute to the protection response and reach for each refugee

Directional Insights

The following are directional insights based on research outcomes:

- UNHCR needs to spend more time in the field to build positive relationships with the communities they seek to protect. Typically, UNHCR and IPs funnel information and resources through male leaders who serve as the points of contact for the community. Over time, this has created a hierarchy of power within the settlement that contributes to exploitation and disparity of resources within the community. Getting to know the members of the community might allow UNHCR to select apolitical points of contact.

- Although it is important for urban refugees to integrate and build social capital networks, there needs to be some level of oversight in terms of the relationships formed with local NGOs. Perhaps, training sessions can be offered to NGOs that wish to visit the communities regularly to impart the unique sensitivities of refugee populations, including legal and political repercussions of NGO actions. There needs to be reporting mechanisms for refugees as well.

- As stated by ZFI President Syed Zafar Mahmood, greater effort should be placed on finding permanent, safe housing for urban refugees. Finding accommodation in the city is not part of UNHCR Urban Refugee Policy, however, when the precarity of their living conditions has the potential to cause physical harm it becomes a protection issue.

- There was no safe space allocated for children during the disaster response. This needs to be made a priority in urban settings where the public has direct access to vulnerable populations.

Overall, the UNHCR and IPs did a remarkable job responding to the crisis in Delhi. They had institutional leverage to act quickly and coordinated goods and services well. This response was made possible by the mere proximity to the fire location. In Jammu, an act of arson at a Rohingya settlement in April 2017 received very little community and UNHCR support. In fact, the author visited the site in October 2017, and many Rohingya were still waiting for UNHCR replacement identity cards. Even though the UNHCR is restricted in Jammu by the Indian government, their partner organization in the region failed to provide this basic protection for months after the arson. Where urban refugees self-settle has a great impact in terms of safety and aid response.

Every organization claimed not to be guided by political relationships or concerns; however, their actions demonstrate otherwise. The quick reprint of identity documents demonstrates the precarity of the political situation of the Rohingya in India. The first concern of police harassment is an extension of this concern. SLIC has been working with police since the announcement of deportation to harbor goodwill. They fear that, as administrators of laws, a state representative’s allegiances may wane, or exploitation may occur.

The Rohingya refugees from this settlement continue to live in squalid conditions to this day. Monsoon rains continue to flood their temporary tents. They are living in still waters, creating opportunity for the spread of disease and snakebites. Mosquito season is soon to follow. There appears to have been a vigorous emergency response, but declining attention is being paid to rehabilitation. To prevent harm in such disasters, a more nuanced definition of safety and rehabilitation needs to be employed based on regional socio-political considerations.

Typical emergency responses will entail ensuring physical safety and providing food, water, and shelter, but undergirding these responses is a tangle of hierarchical relationships that determine the long-term security of refugees.

Endnotes

Endnote 1: IPs are local organizations contracted by the UNHCR to help carry out their mandate in the host country. IPs understanding of the local culture, laws, and geography allows them to execute UNHCR’s mission to be executed with greater ease. ↩

Endnote 2: Number registered by UNHCR India as of April 2018↩

Endnote 3: UNHCR Implementing Partnership Management Guidance Note No. 4↩

Endnote 4: At the time of publication of this report the Rohingya resettlement still had not been rebuilt.↩

References

-

Lowenstein, Allard K. 2015. Persecution of the Rohingya Muslims: Is Genocide Occurring in Myanmar’s Rakhine State? A Legal Analysis. International Human Rights Clinic, Yale Law School. ↩

-

Advisory Commission on Rakhine State. 2017. Towards a Fair and Prosperous Future For The People of Rakhine: Final Report. ↩

-

UNHCR Emergency Handbook. https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/167183/refugee-coordination-model-rcm ↩

Patel, A. (2019). An Assessment of UNHCR Crisis Response of a Rohingya Refugee Camp in India (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 286). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/an-assessment-of-unhcr-crisis-response-of-a-rohingya-refugee-camp-in-india