Boosting Resilience

Exploring a Research Collaborative’s Role in Natural Hazard Adaptation

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

Collaborative approaches are used to address complex natural hazards like wildfire, drought, and flooding. Despite their prevalence, little is known about the long-term outcomes of collaborative groups and there is a need to understand how collaborative groups build adaptive capacity and resilience to natural hazards. This study sought to fill such gaps in understanding using a qualitative case study of a past participatory research project in central Montana, the Judith River Watershed Nitrogen Project. We facilitated a ripple effects mapping (REM) workshop with eleven participants of the original Judith River Watershed Nitrogen Project to understand (a) the outcomes that emerged from participating in the project, (b) how the project’s structure contributed to outcomes, and (b) how participation in the project supported adaptive capacity and community resilience in the watershed. We found that by participating in the Judith River Watershed Nitrogen Project, individuals built awareness and trust and implemented alternative farm management practices. We also found that the project’s structure, goals, and research team helped support these outcomes. Overall, findings indicate that collaborative research projects like the Judith River Watershed Nitrogen Project support outcomes that may contribute to a group’s adaptive capacity to respond to future natural resource challenges and hazards. Though more work is needed to fully explore the linkages between the project’s outcomes and community resilience, Federal Emergency Management Region 8 emergency managers can implement the collaborative processes demonstrated in the Judith Nitrogen Project to build greater awareness and trust in their natural hazard work, as well as look to draw on the networks formed through such participatory research projects when operating in rural contexts.

Introduction

Collaborative models are used to address complex natural resource and hazard challenges in the management, policy, and planning spheres. Collaboration supports several processes and outcomes, including social learning and building knowledge and social capital, and scholars suggest that collaboration can also bolster a group's adaptive capacity and long-term resilience (Pahl-Wostl, 20091; Tabara & Chabay, 20132). Collaborative approaches are increasingly used in environmental research, although given the more recent use of these models, little work has been done to explore the processes and long-term outcomes of such science-oriented projects and groups (Margerum, 2011). Furthermore, few scholars have examined how these kinds of groups contribute to group and broader community adaptive capacity and resilience in addressing natural resource and hazard challenges, especially in rural settings.

This project sought to examine and clarify the processes and long-term outcomes of collaborative environmental research groups by studying an example of a past participatory research project in central Montana, the Judith River Watershed Nitrogen Project (referred to hereafter as the Judith Nitrogen Project). The Judith Nitrogen Project, which occurred from 2011-2015, examined sources of groundwater contamination and evaluated the impacts of alternative farming practices in the Judith River Watershed of Montana. The project included two participant groups: a producer research advisory group and an advisory committee. The producer research advisory group consisted of six area farmers who implemented and evaluated the research team’s alternative practices on their farms. The advisory committee consisted of sixteen individuals representing both farmers and natural resource agencies and entities such as the Montana Natural Resource Conservation Service and Montana State University Extension Service. Both groups worked extensively with the research team to design, implement, and assess the project's findings. By studying participation in the Judith Nitrogen Project, our work aims to contribute to the small but growing body of research about the long-term outcomes of collaborative research projects, develop a greater understanding of how such projects contribute to increased adaptive capacity and resilience in rural contexts, and aid communities and researchers in building effective and mutually beneficial projects.

Literature Review

Since the 1970s, scholars have recognized the existence of “wicked problems,” or those problems in society that have high levels of complexity and are not well understood (Rittel & Webber, 19733). Many of the wicked problems that society faces today fit into the category of natural hazards (Defries & Nagendra, 20174), with examples in Montana including drought (Cravens et al., 20215), wildfire (Hammer et al., 20096), and other exacerbating impacts from climate change (Whitlock et al., 20177). Due to their entanglement with political, economic, and social factors, these hazards offer no clear solution (Head, 20088). Consequently, collaborative approaches that involve multiple individuals and groups are used to address natural hazards and resource challenges, with examples ranging from natural hazard management to policy planning processes (Innes & Booher, 20189; Ray-Bennett et al., 202010; Wondolleck & Yaffee, 200011). Along with management and policy processes, collaborative approaches are increasingly used within scientific research to better understand a topic and aid in improved application of research (Church et al., 202212; Fazey et al.13, 2014; Krueger et al., 201614). Collaborative research includes models such as interdisciplinary science and participatory research, among others (Houser et al., 202115; Jacobs & Frickel, 200916; Klein 200817).

As stated above, scholars argue that collaborative approaches are key to addressing natural resource and hazard challenges (Kapucu et al., 201318; Ray-Bennett et al., 2020). Collaborative groups facilitate shared dialogue and support connections between potentially divergent interests and forms of knowledge (Bos et al., 201319; Innes & Booher, 199920). Studies specific to collaborative research groups also support their role in creating shared understanding and holistic knowledge of a topic (Jacobs & Frickel, 2009). Although these groups vary according to the level of integration and synthesis among participating academics and stakeholders, scholars argue that they may lead to participants having greater trust in project results and improve the implementation of research into decision-making (Krueger et al., 2016). Prominent institutions such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) have even focused their efforts on supporting collaborative science through their funding strategies. NSF listed “growing convergence research,” as one of their “10 Big Ideas for NSF Investment” (202321). There are also growing expectations within society for collaborative groups to produce socially relevant and beneficial knowledge that community members and decision-makers can act on to address natural resource challenges and hazards (McNie 200722; Wall et al., 201723).

Scholars recognize the potential long-term benefits that collaboration provides for individuals and organizations in addressing future challenges (Kapucu et al., 2013; de Kraker, 201724). When individuals work together collaboratively, they can engage in social learning, or learning that promotes individual and collective action within and outside of a group (Bodin 201725). In turn, social learning and other collaborative processes can support the development of sustained social networks and promote the overall adaptivity of a group (Armitage et al., 200826; Margerum, 201127). As a result, collaborative groups and the communities they are embedded in can be more resilient and prepared for future natural hazards and “shocks” to their social-ecological system (Church et al., 2022; de Kraker, 2017).

Research Questions

Although factors such as social learning and greater adaptive capacity are documented in research literature, there is still a need for improved understanding of how collaborative approaches, including those used in science, support adaptive capacity and build community resilience. This lack of information represents a major knowledge gap and an important area of study given the increasing emphasis on collaborative research approaches. Understanding how collaborative groups support resilience to events such as flood and fire is especially important in rural states like Montana where communities are notably vulnerable to natural hazards (Kapucu et al., 2013). The study therefore asked the following research questions:

What outcomes have emerged from participating in the Judith River Watershed Nitrogen Project?

How did the structure of the Judith River Watershed Nitrogen Project contribute to emergent outcomes?

How did participation in the Judith River Watershed Nitrogen Project support the adaptive capacity and resilience of the watershed’s communities?

Research Design

This study used a qualitative critical case study approach to focus on an example of a past collaborative research project located in the Judith River Watershed, the Judith Nitrogen Project (Flyvberg 200628). The study sought to clarify the outcomes of participating in the Judith Nitrogen Project to further understand how participation has supported the adaptive capacity and resilience of the watershed communities. The research design consisted of facilitating a ripple effects mapping (REM) workshop with past participants of the Judith Nitrogen Project. REM is a qualitative, participatory method that consists of open-ended group interviewing and mind mapping to elucidate the outcomes of a particular program or project. REM is valuable because it allows researchers to examine both intended and unintended outcomes, as well as how outcomes are connected (Kollock et al., 201329).

Study Site and Access

We facilitated an in-person REM workshop in June 2023 in the Judith River Watershed of central Montana. We chose this site given the presence and history of a previous collaborative research project in the watershed, the Judith Nitrogen Project. The Judith River Watershed encompasses the counties of Judith Basin and Fergus and has a predominantly rural landscape. The region’s primary economic driver is agriculture, with most acreage in the watershed dedicated to crops such as wheat and barley as well as livestock forages and pastureland (Jackson-Smith et al., 201830). The workshop was developed and facilitated by a PhD student and faculty members at Montana State University working in the disciplines of natural resource social science, environmental planning, and water quality science and education. We accessed potential workshop participants through the previous research leads of the Judith Nitrogen Project, to build off the relationships they had established with participants to conduct outreach and share workshop invitations. Two of these research leads are dissertation committee members for author Madison Boone, and Boone has recently been a project assistant for a Montana NSF Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research project in the watershed. Our proposed research dissemination plan, which includes sharing reports and giving oral presentations to Judith Nitrogen Project participants, including those who did and did not attend the workshop, will allow individuals to respond to our findings in a discursive and informative manner.

Ripple Effects Mapping Workshop

We facilitated the study’s REM workshop with participants of the Judith Nitrogen Project in June 2023. The workshop consisted of four data collection components: first, individuals completed a worksheet, then we held small group discussions followed by an iterative, whole group physical mapping and discussion exercise. We concluded with a final ranking activity. Further description of the study’s design, data collection, and data analysis is included below.

Sampling Strategy

Working with the leads of the original project research team and using purposive sampling, we generated a list of workshop invitees who had been a part of either the project advisory committee, producer research advisory group, or research team. For our workshop outreach strategy, which occurred in Spring 2023, we sent an email invitation to participants and then conducted follow-up calls to confirm if they would attend.

Participant Consent

Following the protocol outlined in this study's IRB, we asked for verbal consent from participants before the start of the workshop regarding their voluntary participation and the recording of workshop discussions.

Workshop Guide

As a project team, we developed and finalized the REM workshop guide in Spring 2023. For our guide, we developed a series of questions for each component of the workshop, including the handout, small group discussion, and broader group discussion. Examples of workshop questions included: “What is one key highlight you took away from participating in the Judith Nitrogen Project?” and “What has happened as a result of participating in the Judith Nitrogen Project?” For the full REM workshop guide and questions, please see the appendix.

Data Analysis Procedures

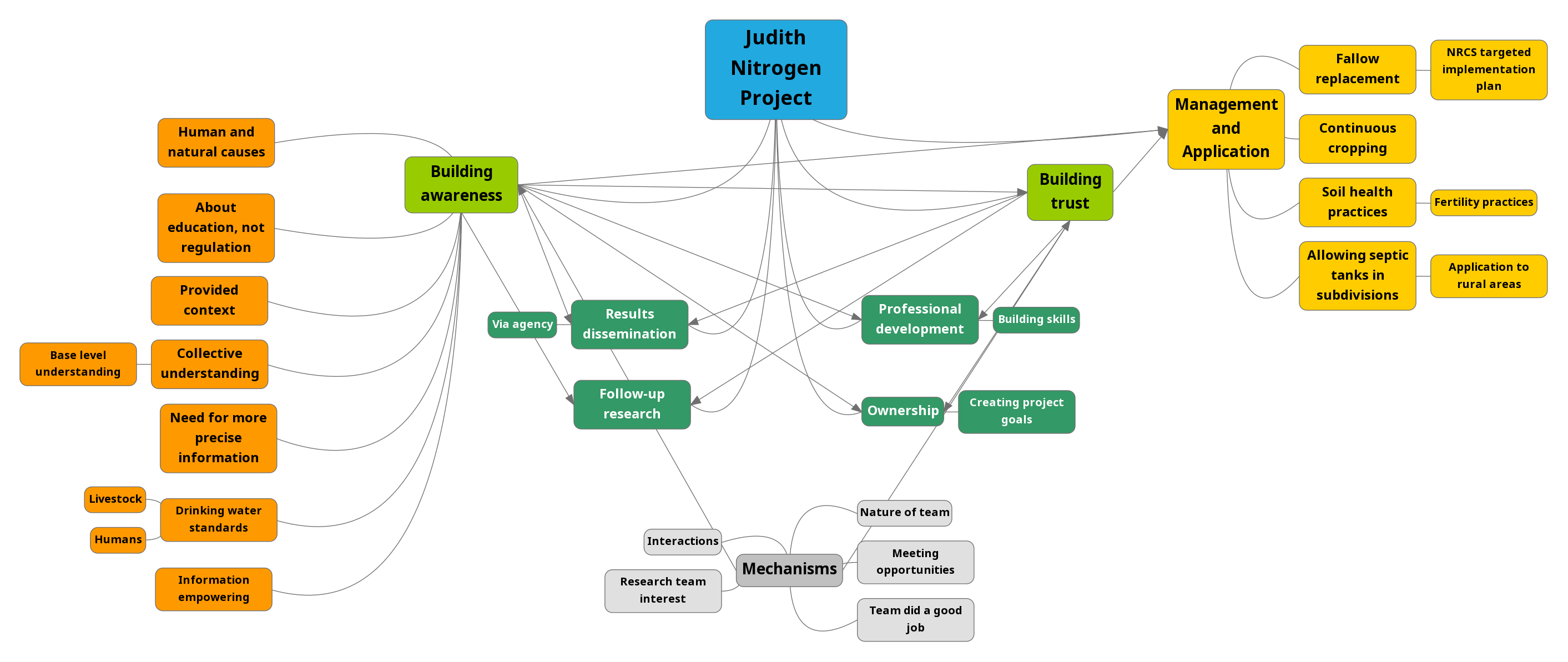

With participant consent, we collected all individual worksheets and recorded the small and large group discussions. We digitized the worksheets and used the Pro Version of the online software Otter.ai to transcribe all workshop audio. We also digitized the physical ripple effects map (see Figure 1) generated from the workshop using Version 1.0 of the online mind mapping software MindMup. We have begun preliminary qualitative coding of the workshop data and outcomes represented on the ripple effects map, but this study’s data analysis is still ongoing.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted through Montana State University’s Institutional Review Board under an Amended Exempt Review Approval (Protocol #2022-843-MB031122-EXEMPT). The study’s IRB was amended and approved in June 2023. The research design posed minimal risks to participants. Before the start of the workshop, we described the purpose of the research, clarified its voluntary nature, asked for permission to record audio, and informed participants that they could leave the workshop at any time. Moreover, we communicated to participants that all information collected from the workshop was confidential and anonymous; we would not use any identifying information in materials that emerged from the research, all findings would be reported in a way that maintains confidentiality, and any sensitive or potentially harmful information would not be reported.

Findings

Figure 1 depicts the ripple effects map created by workshop participants and illustrates what they identified as the major outcomes of participating in the Judith Nitrogen Project. These outcomes were grouped into three primary categories: building awareness, building trust, and management and application. In addition, the map depicts the factors that participants shared when asked how outcomes were achieved, labeled as “Mechanisms” in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Ripple Effects Map of Judith Nitrogen Project Outcomes

Building Awareness

Participants shared that participating in the Judith Nitrogen Project helped them build awareness and understanding of several different topics, noted in Figure 1 above. Participants reported that the project helped them build a greater understanding of how nitrogen moves in soil and water and learned more about the impacts of cropping systems and alternative crop management options. Furthermore, participants reported that they learned specifically about drinking water standards for both humans and livestock, as well as the human and natural causes of nitrogen in surface and groundwater. One participant shared, “…it's not all because of livestock or farming practices, sometimes there is a natural element there. And that's one thing I learned from this; trying to separate that out.” Another stated that humans “do contribute [to nitrates in the water], but the information is empowering.” Participants felt that having a greater understanding of the research and results was not only empowering and increased collective understanding, but that it also provided a foundation from which they could discuss the work with individuals external to the project. As one participant said:

I think one of the outcomes of this whole project was a whole other base level of understanding that affects so many things in terms of agriculture in the Judith Basin area…As a result of this project, I can visit with people that were involved with water well testing. And what I learned from it helped me to visit with those folks that had really high nitrates in [their] wells. Help them understand how some of the practice and timing and so on were affecting the nitrate level in their well. And so, I think, it just extends that whole base, another level in that base of understanding.

Finally, participants reported that their project experience built their awareness of the project’s overall goals and intentions, in addition to its core research and results. For example, participants felt that they understood that the project was about education and not regulation, which helped dissuade initial fears of government intervention and control (discussed below in the Building Trust section). Furthermore, several individuals also identified awareness of the need for long-term research (versus the one- to three year-timeframes of the original project) as a core project outcome, and the group even identified several follow-up topics they felt research focus on more. For example, they were interested in the way that alternative farming and soil fertility practices interact with climate as well as linking changed behaviors to the project.

Building Trust

In addition to building awareness, workshop participants identified building trust as a major outcome of participating in the Judith Nitrogen Project. Several participants shared that before the project started, they were fearful that, if their farming practices were shown to directly contribute to nitrogen pollution in the Judith River Watershed, then project results might be used against them. Specifically, many participants noted that they were concerned that the research results could lead to increased government intervention and regulation in agriculture. As one speaker noted:

My biggest fear getting into this was because of the knee-jerk reaction of politicians and government officials. That they would, if this was deemed that we were more involved in the water and the nitrate level, then it would be a knee-jerk reaction to regulate agriculture.

By participating in the project, and because of the character and efforts of the research team (discussed below in the Mechanisms section), individuals said that they felt they were able to build trust between each other and with the team, as well as have a sense of ownership in the project. As one participant shared, “It was simply just, let’s bring everybody together, and let’s get the participation that we can, and it created that team trust.” However, despite increased trust between the participants and researchers, others noted that government regulation was still a concern, with one individual saying, “Some of the paranoia, for me at least in the early days around regulating agriculture, was kind of difficult to navigate…I think those concerns are always there, and they still are.”

Management and Application

Along with the relational outcomes highlighted above, participants shared that the Judith Nitrogen Project helped create changes in farm management practices across the watershed, labeled as “management and application” on the map (Figure 1). Individuals from both the producer research advisory group and advisory committee felt that the project activities and results spurred increased interest in alternative management practices. One individual from the advisory committee said, “I think [the project has] made a real difference in, every day when I drive home, I go by several fields, now either lentils or annual grain, but it's never fallow.” Another individual from the producer research advisory group shared:

I did somewhat change…I bought a spreader. So, I apply my own fertilizer when I think the time is right for less volatilization, and I soil test more now, and that was probably in large part because of what this study showed…And I also, don’t spread the word around, but I do put some legumes in.

Mechanisms for Outcomes

In addition to the three core outcomes discussed above, workshop participants also shared examples of how they thought these outcomes were achieved, labeled as “mechanisms” on Figure 1. In the context of this study, mechanisms refer to the factors that workshop participants shared as contributing to or supporting the original project’s outcomes. These mechanisms ranged from participants feeling that they had ample opportunities to interact and collaborate with the research team to the level of interest and openness of the research team. One individual shared that “It was well formed. It was all very open and fluid.” Furthermore, the interdisciplinary nature of the research team was often cited by participants as contributing to the project’s success, especially the social science aspect of the project. As one participant noted, “It had never occurred to me to involve a sociologist in the project…You know, some of these things, they need to have a discussion other than the technical…Sociology does play a role on the success and decision-making, actually.”

Discussion

Although the Judith Nitrogen Project formally ended in 2015, our findings indicate that the project supported several long-term outcomes. Regardless of whether an individual was a member of the producer research advisory group, advisory committee, or research team, all workshop participants agreed that building awareness, building trust, and changes in farm management practices were key outcomes of the project. In addition, participants shared several factors related to why they thought the project was successful, including the structure of the project and the openness, interest, and interdisciplinary nature of the research team. Building awareness and understanding are commonly cited outcomes of collaborative groups, regardless of their focus (Eaton et al., 202131; Innes & Booher, 2018; Jacobs & Frickel, 2009). These kinds of outcomes can be categorized as a form of social learning, as participants and researchers in the project learned from each other to build new knowledge that then helped create a shift in understanding and action (Fernandez-Gimenez et al., 200832; Wilmer et al., 202133). For example, participants noted that they learned more about specific alternative farming practices as well as gaining a greater collective understanding of the dynamics and causes of nitrogen pollution, thereby shifting their management practices. Furthermore, they shared this knowledge with individuals external to the project group.

The workshop also catalyzed discussions around interconnections, as participants shared examples of how they continue to use the understanding and awareness they gained from the project. The knowledge participants gained from the project has resulted in them becoming curious about other aspects of the Judith River Watershed, and several individuals expressed a desire to better understand the intersection of water quality and nitrate leaching with economics and drought. One participant noted:

One of the things that we were wondering about is, is that fertilizer became very high priced. And then with the drought conditions, the two things created less fertilizer. So, it would be nice to know how that affected the nitrate leaching. The impact was right away. We’ve had at least two or three years of drought.

These questions remain key topics for potential future research and their discussion in relation to project outcomes demonstrates that participants potentially gained more awareness of the interconnected nature of human and physical systems by participating in the project. Our research therefore suggests that participant knowledge led them to build a greater holistic awareness of the Judith River Watershed.

Although workshop attendees shared that they built greater awareness and curiosity due to their participation in the Judith Nitrogen Project, our findings also suggest that participants’ pre-existing perceptions may have led them to draw unsubstantiated and even incorrect conclusions from the project. For example, how participants perceived human and physical systems in the Judith River Watershed was an interesting point when discussing the causes of nitrogen in surface and groundwater. Several individuals said that the project helped them become more aware that farming was not the sole source of nitrogen pollution, but rather things such as soil type, natural leaching, and existing background levels were also causal factors. There was pushback against the idea that the weight of natural causes was equal to human causes, however, with a member of the original research team clarifying that before human activity, the watershed likely contained low levels of nitrate. These differences in understanding underscore the importance of not only recognizing what kinds of knowledge any participant of a collaborative project gains from that project (Berkes, 200934), but how they use that information with their existing knowledge, context, and perceptions (Taylor & Loë, 201235).

In this case, even though participants felt that they gained a greater awareness of human and natural causes, their understanding may not have been supported by the research (nor was discerning causes necessarily the goal of the Judith Nitrogen Project). Their existing perceptions and concerns about agriculture and government regulation may have interacted with their learning in the project, a finding supported by research that indicates individuals often use new information in a way that confirms, rather than discredits, their existing experiences and perceptions (Jones & Sugden, 200136). In this way, participants created new knowledge that was not necessarily supported by science but fed directly into their preexisting perceptions and contexts, thereby alleviating, rather than challenging, their concerns. More work is needed to truly clarify the interaction of existing beliefs and views with new information gained through a collaborative group to better understand how and why individuals form particular narratives over others.

Greater awareness and understanding helped build trust among the participants and the original research team, another key outcome of the project. By becoming more aware of the nature and goals of the project, combined with the research team’s willingness to listen and learn, project participants felt that they could trust that project results would not be used against them. It is important to note that, although participating in the project did build trust, this trust was specifically developed between participants and researchers. This point may be unsurprising given the scientific focus of the project but is still important to note as individuals continued to express clear distrust of government agencies, both as a regulator and as an information source, as compared to research and practice-oriented entities such as agricultural extension services (Settle et al., 201737). Our results align with previous work that shows that government distrust is common in agricultural and natural resource contexts. For example, in a study of Midwest farmer’s perceptions of climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies, Arbuckle et al. (201538) found that most farmers in the study’s sample opposed government action as compared to agricultural interest groups. Similarly, Ormerod et al. (202139) concluded in a study of public trust of water resource information sources that local government officials were uniformly the least trusted group.

Government distrust was also present even though some of the project participants had worked for federal agencies, and during the workshop, there was clear pushback on these professional roles, despite the strong interpersonal connection and rapport the group had built. Therefore, while participants may have built personal relationships with each other and the research team, their trust in an individual did not necessarily extend to the institution that the individual represented. A portion of this continued distrust may also arise from the perception that broad entities, such as government agencies, often prescriptively operate in rural communities with little understanding or regard for their particular context (Goetz et al., 201840; Ulrich-Schad & Duncan, 202141). As one participant noted when discussing septic systems regulations, “When the rules were written they didn’t care about rural Montana. All they cared about was the high-density area; high-density population areas. That’s where the rules were written, but they apply to the whole state, which is really unfortunate.” Even within the Judith River Watershed, participants noted when discussing fallow replacement and continuous cropping practices that different parts of the watershed had their own localized contexts that did or did not lend themselves to these types of practices.

Conclusions

Although projects like the Judith Nitrogen Project explicitly focus on science, our findings indicate that such projects could lower the "cost" of working together again around new topics, results that are supported by previous work that examines how collaborative natural resource management groups bolster adaptive capacity and response to complex socio-environmental challenges (Armitage et al., 2008; Berkes, 2009; Pahl-Wostl et al., 200742). Participants built a new, collective awareness of their human and natural systems, prompting curiosity about how other natural hazards, such as drought, connect to the knowledge they gained from the project. Furthermore, if participants were to work together again, they may not need to reinvest the same time into building the required relationships and trust. As such, these types of participatory research groups and the long-term relationships they support might more easily pivot to addressing future shocks and hazards, even after a project has formally ended. Our findings also indicate that elements of social learning were present in the project, thereby supporting our hypothesis that the Judith Nitrogen Project strengthened group adaptive capacity and overall resilience. However, more research and theoretical analysis are needed to fully relate these outcomes to specific types of social learning (for example, whether they ascribe to single-, double-, or triple-loop learning) (Newig et al., 201043), gain richer insight into the mechanisms that support such outcomes, and further explore how such projects build broader adaptive capacity and long-term resilience in rural regions.

Implications for Practice

We suggest there are important lessons learned from our research that government agencies and emergency managers in FEMA Region 8 can apply to natural hazard planning that may have implications for disaster recovery and response. We found that the structure of the Judith Nitrogen Project, which focused on equal relationships between scientists, practitioners, and farmers, fostered both awareness and trust. Workshop attendees shared that they often felt that government activity in the Judith River Watershed, of any kind, was overly prescriptive and not applicable to their rural context. The people who took part in the ripple effects mapping workshop made it clear that because of the open sharing of information, consistent meeting opportunities, and emphasis on answering scientific questions, they did not feel that there was an overarching government oversight type of “agenda.”

Consequently, FEMA could use the collaborative strategies demonstrated in the Judith Nitrogen Project in their own communities to help foster awareness and trust at the same time. For example, by promoting continuous, open learning opportunities focused on the hazard at hand, FEMA Region 8 emergency managers and the networks they work with can build mutual awareness of a watershed’s unique social, cultural, and environmental context while simultaneously fostering trust-building interactions. Several workshop attendees also pointed to the presence of a social scientist in the project as a key factor in the project’s success. We therefore suggest that FEMA either require or encourage Region 8 emergency managers to integrate social science training and skillsets into their work to better facilitate and operate in the complex social space of natural hazard planning, response, and recovery. Integrating these new processes and skills would entail long-term time frames to build relationships and trust, which might translate into changes in practice to mitigate risk and responsiveness by FEMA in the case of disaster response and recovery.

In the case that FEMA must respond to a hazard in a community with which they have not yet worked, emergency managers should look to established organizations and groups, something they already do through their work with communities before, during, and after a natural hazard event (Samuel & Siebeneck, 201944). However, FEMA emergency managers and other federal agencies should also consider connecting to groups that form through participatory research like the Judith Nitrogen Project, as these types of networks may not typically be considered. We suggest reaching out to extension, NRCS, and watershed groups who most likely have established relationships with their communities. But beyond simply connecting with local organizations, which FEMA emergency managers already do, utilizing these connections as trusted messengers (Getson et al., 202245) to move forward FEMA’s work is important, given the level of federal and local government distrust found in the Judith River Watershed and similar socio-environmental contexts (Arbuckle et al., 2015).

Study Limitations

Although our study elucidated several key outcomes of participating in the Judith Nitrogen Project, our findings are limited by several factors. First, the workshop had a small sample size and not all original participants of the project engaged in the workshop. Second, the time-limited nature of the workshop did not allow for in-depth exploration and discussion of emergent themes and topics. Finally, our study did not engage individuals outside of the Judith Nitrogen Project and consequently, we cannot fully understand the broader scope of the reported outcomes and the magnitude of our findings beyond the select group of participants.

Future Research Directions

This study acts as a first step in clarifying critical gaps in understanding related to the processes and long-term outcomes of collaborative research groups, and as such, there are ample opportunities for future research that could expand our key findings. For example, more research could be dedicated to clarifying the mechanisms that support the Judith Nitrogen Project's reported outcomes to better understand how these outcomes were achieved. Similarly, each outcome category could warrant its own thread of inquiry to gain greater detail and add nuance. This work could even act as a jumping-off point for researchers and agencies to explore how people perceive the intersection between natural resource and hazard issues (in this case, water quality and drought) and how and why people perceive certain environmental challenges as disasters and not others. Finally, as noted above, more research should be dedicated to applying a theoretical lens to this work to connect it to the broader literature and better understand the role of collaborative environmental research groups in supporting adaptive capacity and resilience in rural contexts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to wholeheartedly thank the participants of the Judith Nitrogen Project and members of the original research team for their time and support in developing this study’s workshop and for their enthusiastic engagement at the workshop. The Quick Response Research Award Program is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF Award #1635593). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or Natural Hazards Center.

References

-

Pahl-Wostl, C. (2009). A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 19, 354-365. ↩

-

Tabara, J. D., & Chabay, I. (2013). Coupling human information and knowledge systems with social-ecological systems change: Reframing research, education, and policy for sustainability. Environmental Science & Policy, 28, 71-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.005 ↩

-

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155-169. ↩

-

Defries, R., & Nagendra, H. (2017). Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science, 356(6335), 265-270. ↩

-

Cravens, A. E., McEvoy, J., Zoanni, D., Crausbay, S., Ramirez, A., & Cooper, A. E. (2021). Integrating ecological impacts: Perspectives on drought in the Upper Missouri Headwaters, Montana, United States. Weather, Climate and Society, 13(2), 363-376. ↩

-

Hammer, R. B., Stewart, S. I., & Radeloff, V. C. (2009). Demographic trends, the wildland-urban interface, and wildfire management. Society & Natural Resources, 22(8), 777-782. ↩

-

Whitlock, C., Cross, W. F., Maxwell, B., Silverman, N., & Wade, A. (2017). 2017 Montana Climate Assessment. Montana State University and University of Montana, Montana Institute on Ecosystems. ↩

-

Head, B. W. (2008). Wicked problems in public policy. Public Policy, 3(2), 101-118. ↩

-

Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2018). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality in public policy processes (2nd ed.). Routledge. ↩

-

Ray-Bennett, N., Mendez, D., Alam, E., & Morgner, C. (2020). Inter-agency collaboration for natural hazard management in developed countries. In D. Benouar (Ed.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia: Natural Hazard Science. Oxford University Press USA. ↩

-

Wondolleck, J. M., & Yaffee, S. L. (2000). Making Collaboration Work. Island Press. ↩

-

Church, S. P., Wardropper, C. B., Usher, E., Bean, L. F., Gilbert, A., Eanes, F. R., Ulrich-Schad, J., Babin, N., Ranjan, P., Getson, J.M., Esman, L. A., & Prokopy, L. S. (2022). How does co-produced research influence adaptive capacity? Lessons from a cross-case comparison. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 4, 205-219. ↩

-

Fazey, I., Bunse, L., Msika, J., Pinke, M., Preedy, K., Evely, A.C., Lambert, E., Hastings, E., Morris, S., & Reed, M. S. (2014). Evaluating knowledge exchange in interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder research. Global Environmental Change, 25, 204-220. ↩

-

Krueger, T., Maynard, C., Carr, G., Bruns, A., Mueller, E. V., & Lane, S. (2016). A transdisciplinary account of water research. WIREs Water, 3, 369-389 ↩

-

Houser, M., Sullivan, A., Smiley, T., Muthukrishnan, R., Browning, E. G., Fudickar, A., Title, P., Bertram, J., & Whiteman, M. (2021). What fosters the success of a transdisciplinary environmental research institute? Reflections from an interdisciplinary research cohort. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 9, 1. ↩

-

Jacobs, J. A., & Frickel, S. (2009). Interdisciplinarity: A critical assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 43-65. ↩

-

Klein, J. T. (2008). Evaluation of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: A literature review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(2), S116-S123. ↩

-

Kapucu, N., Hawkins, C.V., Rivera, F.I. (2013). Disaster preparedness and resilience for rural communities. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 4(4), 215-233. ↩

-

Bos, J. J., Brown, R. R., & Farrelly, M. A. (2013). A design framework for creating social learning situations. Global Environmental Change, 23(2), 398-412. ↩

-

Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (1999). Consensus building and complex adaptive systems: A framework for evaluating collaborative planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 65(4), 412-423. ↩

-

National Science Foundation (2023). NSF’s 10 Big Ideas. https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/big_ideas/ ↩

-

McNie, E. C. (2007). Reconciling the supply of scientific information with user demands: An analysis for the problem and review of the literature. Environmental Science & Policy, 10, 17-38. ↩

-

Wall, T. U., McNie, E., & Garfin, G. M. (2017). Use-inspired science: Making science usable by and useful to decision makers. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 15(10), 551-559. ↩

-

de Kraker, J. (2017). Social learning for resilience in social-ecological systems. Environmental Sustainability, 28, 100-107. ↩

-

Bodin, O. (2017). Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science, 357, 659. ↩

-

Armitage, D., Marschke, M., & Plummer, R. (2008). Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Global Environmental Change, 18, 86-98. ↩

-

Margerum, R. D. (2011). Beyond Consensus: Improving Collaborative Planning and Management. MIT Press. ↩

-

Flyvberg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219-245. ↩

-

Kollock, D. H., Flage, L., Chazdon, S., Paine, N., & Higgins, L. (2012). Ripple effect mapping: A “radiant” way to capture program impacts. Journal of Extension, 50(5). ↩

-

Jackson-Smith, D., Ewing, S., Jones, C., Sigler, A., & Armstrong, A. (2018). The road less traveled: Assessing the impacts of farmer and stakeholder participation in groundwater nitrate pollution research. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 73(6), 610-622. ↩

-

Eaton, W. M., Brasier, K. J., Burbach, M. E., Whitmer, W., Engle, E. W., Burnham, M., Quimby, B., Chaudhary, A. K., Whitley, H., Delozier, J., Fowler, L. B., Wutich, A., Bausch, J. C., Beresford, M., Hinrichs, C. C., Burkhart-Kriesel, C., Preisendanz, H. E., Williams, C., Watson, J., & Weigle, J. (2021). A conceptual framework for social, behavioral, and environmental change through stakeholder engagement in water resource management. Society & Natural Resources, 34(8), 1111-1132. ↩

-

Fernandez-Gimenez, M., Ballard, H. L., & Sturtevant, V. E. (2008). Adaptive management and social learning in collaborative and community-based monitoring: A study of five community-based forestry organization in the western USA. Ecology and Society, 13(2), 4. ↩

-

Wilmer, H., Schulz, T., Fernandez-Gimenez, M. E., Derner, J. D., Porensky, L. M., Augustine, D. J., Ritten, J. Dwyer, A., & Meade, R. (2021). Social learning lessons from collaborative adaptive rangeland management. Rangelands, 44(5), 326-326. ↩

-

Berkes, F. (2009). Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management, 90, 1692-1702. ↩

-

Taylor, B., & Loë, R. C. (2012). Conceptualizations of local knowledge in collaborative environmental governance. Geoforum, 43(6), 1207-1217. ↩

-

Jones, M., & Sugden, R. (2001). Positive confirmation bias in the acquisition of information. Theory & Decision, 50, 59-99. ↩

-

Settle, Q., Rumble, J. N., McCarty, K., & Ruth, T. K. (2017). Public knowledge and trust of agricultural and natural resources organizations. Journal of Applied Communications, 101(2). ↩

-

Arbuckle, Jr., J. G., Morton, L. W., & Hobbs, J. (2015). Understanding farmer perspectives on climate change adaptation and mitigation: The roles of trust in sources of climate information, climate change beliefs, and perceived risk. Environment & Behavior, 47(2), 205-234. ↩

-

Ormerod, K. J., Kelley, S., & Redman, S. (2021). The geography of trust: Understanding differences in perception of risk, water resources, and regional development. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 23(6). ↩

-

Goetz, S. J., Partridge, M. D., & Stephens, H. M. (2018). The economic status of Rural America in the President Trump Era and beyond. Applied Economic Perspectives & Policy, 40(1), 97-118. ↩

-

Ulrich-Schad, J. D., & Duncan, C. M. (2021). People and places left behind: Work, culture and politics in the rural United States. In I. Scoones, M. Edelman, S. M. Borras Jr., L. F. Forero, R. Hall, W. Wolford, & B. White (Eds.), Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World, pp. 59-79. Routledge. ↩

-

Pahl-Wostl, C., Craps, M., Dewulf, A., Mostert, E., Tabara, D., & Tailieu, T. (2007). Social learning and water resources management. Ecology and Society, 12(2), 5. ↩

-

Newig, J., Gunther, D., & Pahl-Wostl, C. (2010). Synapses in the network: Learning in governance networks in the context of environmental management. Ecology and Society, 15(4), 24. ↩

-

Samuel, C., & Siebeneck, L.K. (2019). Roles revealed: An examination of the adopted roles of emergency managers in hazard mitigation planning and strategy implementation. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 39, 101145. ↩

-

Getson, J.M., Church, S.P., Radulski, B.G., Sjöstrand, A.E., Lu, J., & Prokopy, L.S. (2022). Understanding scientists’ communication challenges at the intersection of climate and agriculture. PLOS One, 1-22. ↩

Boone, M., & Church, S. P. (2023). Boosting Resilience: Exploring a Research Collaborative’s Role in Natural Hazard Adaptation (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 358). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/boosting-resilience