Building Back Better: Understanding How Health Considerations are Incorporated into Local Post-Disaster Recovery Implementation

Publication Date: 2018

Abstract

Using Hurricane Harvey as a case, this study examines the extent to which communities are aiming to build resilience during the disaster recovery process. We conducted key informant interviews with local health departments and one office of emergency management to determine if and how their communities are incorporating public health considerations into the visioning, planning, implementation, and assessment phases of disaster recovery. Utilizing a combined inductive and deductive approach, we coded and thematically analyzed interview notes and/or transcripts. We found that communities are continuing to miss opportunities to “build back better” and to build resilience through disaster recovery. Local health departments would benefit from additional resources, support, and technical assistance designed to facilitate work across sectors and resilience-building during recovery.

Background

In 2017, the United States was plagued by a historic number of billion-dollar disasters. These events exacted sizeable impacts on life and property—across all 16 billion-dollar disasters, the cost was more than $300 billion, and the disasters claimed 362 lives (NOAA 2018a1). Unfortunately, certain types of extreme weather events are only expected to increase in frequency and intensity in the future (Melillo et al. 20142; IPCC 20143). Aside from the impacts of increased natural hazard activity on the areas in which they will occur, it is possible that these events will also impact areas that are not directly affected via future migration out of disaster-prone regions. This migration will place additional strains on the areas where disaster refugees settle (IPCC 20124).

Building Resilience

Given these harsh realities, it is imperative that we strengthen the ability of our communities to minimize the impacts of and cope with future disasters—that is, we must build resilience. While various definitions for community resilience exist, Chandra et al. (20115) developed the following definition in the context of national health security: “Community resilience entails the ongoing and developing capacity of the community to account for its vulnerabilities and develop capabilities that aid that community in (1) preventing, withstanding, and mitigating the stress of a health incident; (2) recovering in a way that restores the community to a state of self-sufficiency and at least the same level of health and social functioning after a health incident; and (3) using knowledge from a past response to strengthen the community’s ability to withstand the next health incident.” Resilience necessitates that communities work together to build robust physical infrastructures, socioeconomic characteristics, population health, education, and natural environments that offer protection during and after disasters (NRC 20126).

Fortunately, in recent years, federal agencies have increasingly recognized the importance of community resilience; some have incorporated it into their disaster-related frameworks and grants (Chandra 20147). For example, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) states in the “purpose” section of its National Disaster Recovery Framework that it aims to reduce vulnerabilities and build resilience through recovery (FEMA 20168). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) includes community resilience as one of six domains for their Preparedness Capabilities, and the first strategic objective of the National Health Security Strategy is to “build and sustain healthy, resilient communities” (CDC 20119; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response 201510).

Despite abundant frameworks for resilience and apparent federal support for resilience, prescribing an approach for building resilience has proved to be challenging (Wulff, Donato, and Lurie 201511). To address this challenge, Chandra et al. (2011) developed eight levers designed to assist communities in building resilience. The levers—and a brief description for each—are:

- Wellness: promote pre-and post-incident population health, including behavioral health;

- Access: ensure access to high-quality health, behavioral health, and social services;

- Education: ensure ongoing information is available to the public about preparedness, risks, and resources before, during, and after disasters;

- Engagement: promote participatory decision-making in planning, response, and recovery activities;

- Self-sufficiency: enable and support individuals and communities to assume responsibility for their preparedness;

- Partnership: develop strong partnerships within and between government and nongovernmental organizations;

- Quality: collect, analyze, and utilize data on building community resilience; and

- Efficiency: leverage resources for multiple uses and maximum effectiveness.

Resilience and Disaster Recovery

In addition to improving communities’ abilities to withstand and mitigate disasters, these levers provide benefits for communities during steady state. By targeting actions that can promote everyday population health and resilience, Chandra et al. (2011) present levers that can be applied to both pre- and post-disaster contexts. As recovery experts have noted, disaster recovery yields an opportune time to build resilience, given the influx of resources into a community post-disaster and the unique chance to invest in and rebuild society for the long-term—to “build back better” (IOM 201512; Dzau, Lurie, and Tuckson 201813). Although these characteristics of the recovery process position it as a natural candidate for resilience building, barriers exist. Chief among these barriers is conflict between the desire to reflexively return to pre-disaster conditions and the desire to rebuild in a way that is attentive to equity and health (Rubin 2009; Kates et al. 200614). This creates a tension between “snapback (essentially restoration of the past) and redevelopment that addresses future needs and vision” (Rubin 200915). During recovery from previous disasters, communities have largely attempted to build resilience by adopting infrastructure-centric approaches rather than those that focus on people, equity, and address the levers of resilience described above (IOM 2015). Furthermore, the disaster recovery process is subject to time compression wherein—in some cases, depending on the disaster—an entire community must be redeveloped and rebuilt, services must be restored, and livelihoods must be returned (Olshansky, Hopkins, and Johnson 201216). Time constraints present a significant challenge for building back better, as the process of community development is complex even under ideal circumstances. These barriers constitute significant missed opportunities for building back communities in ways that are more conducive to resilience—ones we can no longer afford to forego with anticipated increases in disaster frequency and intensity.

Fortunately, frameworks have been developed to assist communities in overcoming these barriers and exploiting the natural synergies between the recovery process and building community resilience. One such framework was put forth by the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)) in their 2015 report entitled, Healthy, Resilient, and Sustainable Communities After Disasters (hereafter, referred to as “the NAM report”). The NAM report identified gaps in understanding the extent to which resilience building is incorporated into disaster recovery efforts and offered cross-sectoral and sector-specific recommendations on how to build resilience. The report: describes the recovery planning process as similar to the steady state community strategic planning process; recommends implementing a process for recovery planning similar to that utilized in strategic planning; provides examples of how communities have built resilience through recovery; and calls for research to identify the facilitators and barriers to building resilience during recovery and develop tools to evaluate the impacts that recovery activities may have on health. The report also provides a framework for integrating resilience into recovery planning that consists of four phases: developing a vision of a healthy community to guide recovery planning and efforts; utilizing assessments to inform recovery planning; planning for recovery; and implementing the recovery process (IOM 2015).

Beyond the aforementioned elements, another major component of the NAM report is its recommendation to implement a Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach to recovery. The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) describes HiAP as “a change in the systems that determine how decisions are made and implemented by local, state, and federal governments to ensure that policy decisions have neutral or beneficial impacts on health determinants. HiAP emphasizes the need to collaborate across sectors and break down ‘silos’ to achieve common health goals. It is an innovative approach to the processes through which policies, plans, and programs are created and implemented but does not require that health be at the center of every policy, plan, or program” (NACCHO 201417). HiAP has been promulgated by researchers and practitioners alike as a tool for addressing social determinants of health and promoting health equity through decision making (Hall and Jacobson 201818). By strategically applying a HiAP approach during each of the four phases outlined in the NAM report—visioning, assessment, planning, and implementation—communities can build back in ways that build resilience (IOM 2015). NACCHO describes local health departments (LHDs) as “natural leaders to implement HiAP at the local level,” and the report similarly recommends that LHDs take the lead in many of the resilience-building recovery activities given the natural connection between building resilience and their mission of promoting population health (NACCHO 2014; IOM 2015). Thus, we have focused this study on assessing LHDs’ resilience-building efforts after Hurricane Harvey.

Hurricane Harvey

Hurricane Harvey pummeled Southeast Texas from August 25–31, 2017 (NOAA 2018b19). Making landfall as a Category 4 hurricane, Harvey pelted the areas in its path with rainfall of between 4.62 and 56 inches, resulting in a cumulative 33 trillion gallons of water (NWS; Shultz and Galea 201720). Approximately 90 percent of the river forecast points in the affected area reached flood stage, and nearly half of the river forecast points broke records (NWS 201721). Harvey displaced more than 30,000 people and wreaked havoc on more than 200,000 homes and businesses, with an estimated cost of $125 billion—a price tag second only to Hurricane Katrina’s $161 billion (NOAA 2018c22). In light of these devastating impacts, Hurricane Harvey presents a timely opportunity to test the operationalization of the NAM report’s recommendations. By exploring the extent to which entities participating in recovery efforts have incorporated health considerations, information, and data into rebuilding Southeast Texas, we can gain a better understanding of the challenges and lessons learned associated with building resilience through recovery, and can better identify the supports and actionable strategies from which LHDs could benefit as they aim to build resilience in their communities.

Research Question and Methods

This study aimed to answer the research question: How are local health departments working across sectors to incorporate health and wellbeing considerations into local recovery planning and implementation processes in the Texas jurisdictions affected by Hurricane Harvey? Through semi-structured interviews, the study team elicited information from respondents regarding their recovery planning and implementation processes and activities, as well as their organizations’ roles in recovery. The research team developed the interview guide through an iterative process that involved review and refinement by seven public health practitioners and academics, including those from the University of Washington, the University of Texas School of Public Health, NACCHO, and the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS). The interview guide was informed by the NAM report and intended to address the core elements of the recovery strategic planning framework presented in the report. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board determined the study to be exempt on November 3, 2017.

Recruitment

The study team first identified all of the counties eligible for individual assistance as part of FEMA’s Texas Hurricane Harvey (DR-4332) disaster declaration. Then, we cross-referenced the list of counties with the DSHS list of local public health agencies, identified the counties without these agencies, and obtained contact information through online searches. DSHS then reviewed the list to resolve discrepancies between DSHS websites and to provide any contact information that the research team was unable to locate. Finally, we contacted the 26 agencies that remained after these steps. We emailed individuals for whom an email address was available and contacted the other individuals via telephone. Follow up correspondence was conducted via the same method as the initial contact. The study team obtained consent from all participants prior to beginning the interviews.

Data Collection

The interviews were mixed mode, with the mode dependent on interviewee availability and fieldwork logistics. We conducted six of the 10 interviews in person and conducted the remaining four interviews via telephone. Five of the in-person interviews occurred at the respondent’s LHD, and one occurred at the DSHS office. We audio recorded all but one of the interviews, and the recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. One interviewee declined to be recorded, so the research team utilized the detailed typed notes taken during the interview in lieu of a transcription. Interviews were conducted in December 2017 and January 2018.

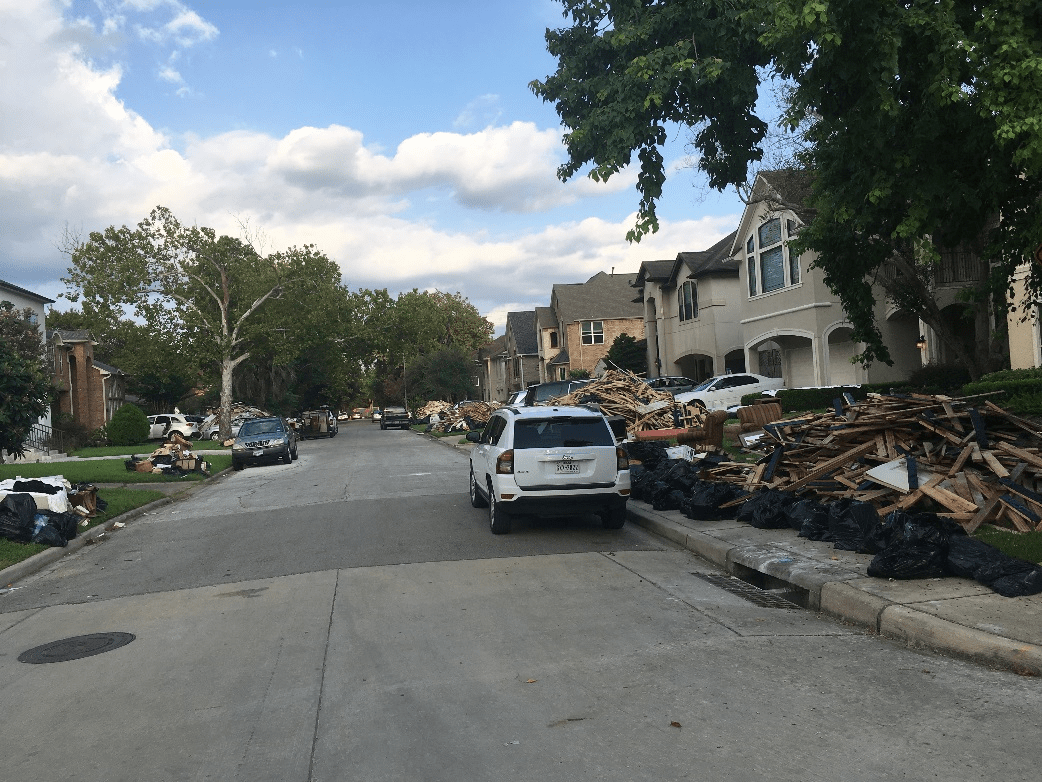

Aftermath of Hurricane Harvey in Bellaire, Texas. ©Janelle Rios, 2017

Aftermath of Hurricane Harvey in Bellaire, Texas. ©Janelle Rios, 2017

Data Analysis

We utilized a combined inductive and deductive approach to conduct a thematic analysis of the data. First, we developed a priori codes based on the research question and the NAM report framework underpinning the study. Next, we reviewed all of the transcripts, noting additional themes that warranted inclusion as codes. After this step, we drafted a preliminary codebook. We then conducted consensus-building activities wherein two research team members coded one transcript, discussed and adjudicated the results, and refined the codebook accordingly. Finally, one research team member coded the remaining interviews in NVivo for Mac v11.4.3 (QSR International, Australia) and summarized themes across respondents. The level of analysis for this study was the agency rather than the individual interviewee. Throughout this report, “respondent” refers to the responding agency.

Results

The research team conducted semi-structured interviews with 17 respondents from 10 different organizations—nine LHDs and one office of emergency management—for this study. Of the 26 agencies that were contacted, 10 agreed to participate in an interview. In Table 1, we describe the respondents and their job titles.

Table 1. Number of Respondents by Position

| Number of Respondents | Positions |

|---|---|

| 5 | Health Department Director |

| 4 | Public Health Emergency Preparedness Coordinator |

| 1 | Deputy Health Authority |

| 1 | Special Assistant to the Health Department Director |

| 1 | Emergency Management Coordinator |

| 1 | Epidemiologist |

| 1 | Public Health Nurse |

| 1 | Staff Analyst |

| 1 | Communications Staff |

| 1 | Purchasing/Finance Staff |

In this section, we highlight key themes that emerged during thematic analysis of the interview transcripts and notes. The results are divided into the following sections: recovery visioning and goals; planning; the role of LHDs in recovery; interdisciplinary collaboration; response and short-term recovery implementation; intermediate and long-term recovery implementation; assessments; and challenges and lessons learned.

Recovery Visioning and Goals

The NAM report notes that recovery should be “viewed as an opportunity to advance a shared vision of a healthier, more resilient, and sustainable community.” In order to advance this shared vision, a shared vision first must be developed and accepted by the health department, the larger community, and decision makers. Ideally, the community then utilizes this goal to guide the recovery process, serving as the driving force underpinning the decisions and actions taken to achieve the goal.

Our findings suggest that the visioning phase of recovery is largely absent from the Harvey recovery process. Rather than striving to create a healthy community, respondents most frequently described the chief objective of their recovery processes as returning their community to normal. Respondents noted that recovery discussions revolved around “getting back to normal,” “trying to stabilize” the community, and “restoring [infrastructure] to pre-disaster condition.” When asked to describe successful recovery in their community, one respondent said, “coming back into what we call a steady state.”

In general, respondents described undertaking more reactive—rather than proactive—approaches to recovery. Respondents’ recovery processes focused on providing resources and addressing community needs as they were identified, rather than setting overarching community recovery goals and acting to achieve them. Even in cases when respondents anticipated community needs as opposed to reacting to them, their efforts largely focused on hardening critical infrastructure or preventing future short-term health impacts from the storm, rather than aiming to improve long-term community health. For example, two respondents mentioned taking steps to prevent the flu and mold-related health impacts resulting from Harvey. While the recovery process should be responsive to and informed by community needs, the approach of allowing short-term needs to guide recovery priorities minimizes the ability to implement a coordinated, HiAP approach due to its reactive nature. Without concrete recovery goals that focus on addressing the determinants of long-term health, it is unlikely that communities will have the coordinated approach and community-wide buy-in necessary to build resilience long-term.

While the majority of respondents employed reactive approaches to recovery, it is encouraging that one community described attempting to build resilience from future disasters through their recovery efforts. This respondent noted that the goal of their community’s long-term recovery group “is to not only address the needs of this particular disaster, but also, in some way, shape, or form, be able to look at future disasters, and see, at least, if we can put some things in place that might be beneficial.” By adopting a long-term, resilience-based perspective, this community aims to improve its ability to withstand and recover from future disasters.

Planning

During the interviews, respondents described the plans and planning processes they utilized for the recovery process. These plans and processes involved both pre-event planning and post-event planning, which we describe separately below.

Pre-Event Planning

All respondents described engaging in some form of pre-event planning. The planning activities respondents cited most commonly were emergency preparedness exercises, drills, and trainings. Most of these activities focused on components of the response and short-term recovery, such as testing the emergency alert system, trainings on Incident Command System (ICS) and National Incident Management System (NIMS), shelter plan drills, and mass vaccination trainings. In addition to exercises, drills, and trainings, respondents also reported engaging in other planning efforts—such as developing written plans or participating in less formalized planning efforts—which also largely focused on response and short-term recovery. These activities included:

- developing plans for: points of distribution, mass care, evacuation for individuals with functional and access needs, mass vaccination, shelter operations, ICS operations, severe weather, and post-event disease surveillance;

- establishing contracts with debris removal services;

- vaccinating responders pre-event; and

- identifying individuals with functional and access needs for evacuation purposes.

Only a couple of respondents described developing plans that focused on intermediate and long-term recovery. As one respondent remarked, “I don't know how much the plan has been set up to guide the recovery effort, because it's really a response plan. It's what are you doing in those immediate 24 hours to a week, 2 weeks out after the event. So it's really sort of that response phase. And that's kind of where the plan begins and ends.”

Most respondents noted that grant funds enabled and/or required them to engage in these pre-event planning activities (e.g., CDC funding for the Public Health Emergency Preparedness cooperative agreement and the Cities Readiness Initiative and hazard mitigation grants), and several noted having a staff member at the LHD whose role was to lead planning efforts. However, respondents did not report leveraging these grants to develop recovery-specific plans.

Post-Event Planning

Only half of the respondents reported having a formalized structure or group responsible for post-event recovery planning. These structures included long-term recovery groups and collaboratives—typically consisting of subgroups around basic needs, case management, public health, mental health, volunteer management, and efforts to repair and rebuild—as well as a “virtual ICS” structure and an interdisciplinary group of county agencies convened by the county judge.

The half of respondents without formalized structures for making recovery-related decisions reported simply responding to community needs as they were identified. Several of these respondents noted that their Commissioners’ Courts and/or county judges were responsible for allocating resources toward recovery efforts, but respondents did not describe any intentional planning activities undertaken by these entities.

The respondents who reported having formalized structures for post-disaster recovery planning described a more coordinated approach to recovery than those who lacked formalized structures. While most of these respondents reported engaging partners in their recovery decision-making processes, sharing resources across partner organizations, and undertaking a more whole-community approach to recovery, in some cases, their post-event planning processes were fragmented. For instance, respondents reported having long-term recovery groups with different subcommittees, but did not always indicate whether or how these subcommittees looked to exploit natural synergies across their work. While one respondent noted that the intent of their recovery group was to minimize duplication of recovery activities, another described decisions as typically made “on the fly” and said that partners typically “report out” during meetings rather than exerting true influence over the direction of each other’s work. Notably, one health department was able to utilize recovery-related technical assistance and recommendations provided by a national philanthropic organization with recovery experience in planning and structuring their recovery activities.

Additionally, despite these formal recovery planning structures, none of the respondents reported developing written plans post-event to guide recovery or utilizing previously developed, community-wide plans—such as community health assessments, community health improvement plans, or community-level strategic plans—to guide their communities’ recovery efforts. Instead, recovery planning was driven largely by community needs articulated by a variety of sources, including elected officials, social service professionals working in the community, community members themselves, or experiences with previous disasters. As one respondent said, “there's no set plan for it, there's not, but we've been around long enough and operating in disasters here in the county, we kind of know based on the intelligence or information that we're getting from the community, what's the priority.”

The Role of LHDs in Recovery

According to the NAM report, the public health sector has a large role in building resilience through recovery. The NAM report designates public health as the lead entity for a host of priority activities and lists public health as primary and/or supporting actor for the priority activities for many other sectors. For example, LHDs may inform community redevelopment planning and provide data and information to other sectors to ensure that they consider the long-term health impacts of their decisions and actions. These activities are contingent on the meaningful engagement of public health in recovery planning and decision making. To this end, during the interviews, we asked respondents from LHDs to describe the role of the health department in the recovery process, as well as the extent to which the recovery process prioritizes other areas over public health.

The majority of LHD respondents reported being involved in their communities’ recovery decision-making processes to some extent. Several LHD respondents provided recommendations and input to facilitate decision making, such as decisions around aerial mosquito spraying and lifting boil water advisories. Several others reported influencing the direction of recovery in other ways. For instance, one health department helped develop the community’s long-term recovery group and sits on the group’s executive committee. From that position, the LHD is able to influence the direction of recovery, including subgroups in which the LHD does not participate directly. Other LHDs said that their local government looks to them to make decisions and that they convey their community’s most pressing needs directly to state representatives and request resources. Some LHDs assumed leading roles in whole-community recovery efforts, such as leading Neighborhood Restoration Centers and other recovery activities.

While most respondents reported having a “seat at the table,” the extent to which their participation was meaningful and influential varied. One respondent remarked that despite the LHD’s involvement in decision-making bodies, they struggle to gain support for their positions, having to “consistently remind them that the decisions need to be driven by a citizen's need and really empirical data, and not so much of political fallout, and who's controlling the purse strings.” Several health departments participated in recovery decision-making processes mainly through participation in health-specific decisions, thus limiting their impact on community-wide changes beyond the health sector. Additionally, some health departments’ involvement focused on updating other stakeholders on their recovery activities and processes rather than providing feedback or recommendations to impact the direction of recovery.

Nearly half of the respondents reported that public health is only important in certain circumstances, such as outbreaks and other emergencies; one respondent described public health as “an afterthought,” while another stated public health is “an outside entity because it never was a part of anything to begin with,” The majority of respondents also mentioned that their county judge plays a significant role in decision-making for their jurisdiction, with respondents describing the judge as the “tsar of the county,” and the individual who “runs everything.” As one respondent stated, “when the judge wants to do something, it’s a lot easier.” Respondents indicated that judges issue disaster declarations, are kept apprised of all response and recovery activities, set the dollar amount for food vouchers, and determine which county agencies will participate in decision-making processes and meetings.

The research team also asked respondents to describe areas that were commonly prioritized over public health. These areas included: basic needs, such as housing, social services, and displacement; police and fire; emergency management; public works; engineering; and politics. One respondent simply said that public health is “not at the top of the list.”

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

In Table 2, we list the key types of partners with which respondents reported collaborating. This collaboration included work on elements of response and recovery implementation and planning, as well as other activities.

Table 2. Key Collaborators and Activities

| Partner Organization(s) | Activities |

|---|---|

| Emergency Management |

Response planning, including:

|

| Other Local Government Agencies (e.g., law enforcement, mosquito control, roads and bridges, county mental health agencies, environmental health, flood agencies, social services, purchasing) |

Response planning, including:

|

| Local Decision Makers (e.g., judge, Commissioner’s Court, elected officials) |

|

| State and Federal Partners |

Response implementation, including:

|

| Schools and Academic Institutions |

Response planning, including:

|

| Community Recovery Groups (comprised of private sector, local nonprofits, governmental entities, faith-based organizations, schools, and other entities) |

|

| Foundations, Nonprofits, Community-Based Organizations, and Non-Governmental Organizations (e.g., American Red Cross, United Way, Medical Reserve Corps, legal aid organizations, workforce development programs) |

Response implementation, including:

Recovery planning, including:

|

| Health Care Partners (e.g., nursing homes, dialysis centers, hospitals; health care coalitions) |

Response implementation, including:

|

Response and Short-Term Recovery Implementation

Although we reminded respondents at the outset of the interview—and during the interview, as needed—that the interview was intended to focus on intermediate and long-term recovery, respondents consistently conflated response/short-term recovery and intermediate/long-term recovery. In this section, we describe the response/short-term recovery activities reported. These activities included shelter operations and surveillance, as well as administering vaccines to responders and/or community members. Several respondents also reported that health department staff: assisted with evacuation and rescue efforts; connected community members with resources; disseminated alerts and other information about response and short-term recovery activities to the public; and coordinated Strategic National Stockpile supplies and points of distribution materials and logistics. A couple of respondents described managing medical volunteers, including dispatching the Medical Reserve Corps to conduct assessments and coordinating and verifying the credentials of out-of-state health care professionals. Additional activities, reported by only one respondent each, included:

- coordinating contracts with debris removal services;

- monitoring employee mental health during the event;

- performing essential public health services in the shelter;

- housing employees from other governmental agencies in the local health department; and

- helping triage patients to the area hospital.

Intermediate and Long-Term Recovery Implementation

In this section, we describe the intermediate and long-term recovery implementation activities reported by respondents. First, we describe the extent to which respondents described utilizing recovery as an opportunity to meet preexisting goals and mitigating health issues through recovery. Then, we turn to descriptions of the recovery activities by sector.

Meeting Preexisting Goals and Mitigating Health Issues

Despite the NAM report’s lofty goals of communities utilizing recovery to meet preexisting goals, we found minimal evidence of this throughout our interviews. Only one respondent reported tying recovery activities to their health department’s strategic plan objectives, noting that in tandem with recovery efforts, they were encouraging healthy habits, attempting to address behavioral health issues, and promoting other population health initiatives. However, while the health department aligned its strategic plan to its recovery activities, this connection appeared to be largely internal. They did not appear to connect the community-level strategic plan to their recovery activities and did not mention involving partners or other stakeholders in achieving these goals.

Additionally, the majority of respondents did not describe any actions being undertaken—either by the LHD or by partner organizations—to mitigate their community’s extant health issues through recovery. The only example of a community potentially mitigating health issues through recovery was through updating building codes to improve the community’s housing. As Hurricane Harvey exposed substandard housing in the respondent’s community, they indicated that their county’s decision makers were debating whether to adopt and enforce stricter building codes to ensure homes are rebuilt to a higher standard.

Public Health and Healthcare

Respondents described the public health- and health care-related recovery activities their communities were undertaking. These activities focused on restoring and delivering essential public health and health care services.

The most commonly described intermediate and long-term recovery activity related to these areas—reported by over half of the respondents—was health and safety inspections (e.g., at restaurants, schools, and foster homes). Several respondents described their efforts to restore potable water and sanitation, including testing water samples, providing input on when to lift their community’s boil water advisory, restoring sanitation services, ensuring wastewater systems were operational and not overflowing, and checking septic systems. Several respondents also reported that community-based organizations were providing health services to residents, including services targeted to low-income individuals, older adults, and the “medically vulnerable.”

Additionally, several respondents reported conducting vector control, disease surveillance, and outbreak investigations, and administering flu and tetanus vaccines. A couple of respondents reported that their communities provided animal control services—including repatriating animals and tracking strays—and helped with medication assistance. Other public health and health care recovery activities included:

- conducting public information campaigns about the flu;

- focusing on addressing health disparities;

- restoring LHD business operations;

- having a public and behavioral health group as part of the long-term recovery group;

- communicating with the public about family planning; and

- dispatching mobile clinics to the community to distribute health information.

Mental Health

Only half of the respondents described recovery activities focused on mental and behavioral health. However, the majority of these respondents described mental health as a high priority issue in their recovery efforts—both for the community and for their organization’s employees. For example, one LHD conveyed to the state health commissioner that mental health case management was their community’s most pressing issue, noting that they “wanted to make sure that we weren't putting [mental health] on the back-burner…you can't have a healthy recovery unless you're focused on [mental health].” A couple of respondents acknowledged that mental health is part of holistic recovery, and several noted that their communities had specific groups dedicated to providing mental health services during recovery. Despite this commitment to addressing mental health issues through recovery, several respondents expressed doubts about the success of their mental health programming, citing a lack of resources allocated for mental health services and cultural stigmas associated with seeking mental health services as the rationale for these doubts.

Social Services

Respondents also described the social services provided by their communities during recovery. The most commonly reported social service offered—reported by half of respondents—was case management. Respondents reported that their communities were referring individuals to other services identified by case managers and connecting people to case managers through their basic needs hotline. A couple of respondents identified case management as a subgroup of their long-term recovery groups, while another respondent said there were multiple private organizations offering case management. The organizations providing case management services included these private organizations, FEMA, the county’s social services department, and other community-based organizations.

Following case management, the next most commonly identified recovery social service was food assistance, described by several respondents. This included the Disaster Special Nutrition Assistance Program (D-SNAP) and other food vouchers. A couple of respondents also described working with Special Nutrition Assistance Programs for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) to provide baby formula, diapers, and other supplies for young children and their families. Other social services described by only one participant each included:

- establishing an “adopt-a-family” program in which families, community-, and faith-based organizations agreed to provide basic needs for a family;

- community education and outreach describing the social services available;

- a pop-up shop for community members to secure furniture and clothing;

- providing transportation for residents to medical appointments, grocery stores, and other services;

- transitioning individuals into long-term care facilities;

- providing legal assistance; and

- providing workforce development opportunities.

Housing

Although several respondents described residents’ displacement as a result of the storm, only a couple expressed concerns about affordable housing post-Harvey, and there were few mentions of communities making long-term plans to address affordable and healthy housing. One respondent identified ensuring affordable housing and keeping displaced communities together as key goals of their recovery efforts, and another indicated that their community was providing short-term rental assistance for residents. The most commonly reported recovery activity related to housing—reported by nearly all respondents—was providing the community with information, outreach, or supplies to assist with mold remediation. This information and education focused on the adverse health effects of mold exposure and safe mold cleanup instructions, and LHDs either worked with partners to disseminate mold kits or provided mold kits and cleanup supplies themselves. One health department reported connecting community members to mold remediation services, while another noted that one of their partner organizations trained volunteers to assist with mold remediation. Additionally, one health department said their long-term recovery group was mucking and gutting homes.

Half of the respondents also reported that their communities were working to renovate or repair homes, but none of them described the rebuilding process as having the ultimate goal of increasing resident access to goods or services, increasing the number of structures that utilize green designs, or building social connectedness, as described in the NAM report. Rebuilding activities reported centered on rebuilding to the previous state rather than utilizing recovery as an opportunity to influence community redevelopment.

Assessments

The NAM report recommends that communities assess their community’s health status both before and after a disaster. Communities should integrate community health assessments, hazard identification assessments, and risk assessments into recovery planning by utilizing the data from these assessments to inform the community’s recovery goals. After a disaster, a community should continuously conduct impact assessments to identify the damage wrought by the disaster, as well as to identify community health needs and monitor recovery. In this section, we describe the assessments reported by respondents.

Pre-Disaster Assessments

There was only one instance of a health department conducting a pre-disaster community health assessment for the purpose of baseline data collection. This LHD reported conducting a Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER) both pre-event and post-event.

Post-Disaster Assessments

The most common mechanism for assessing the community’s status post-disaster was through the collection of anecdotal and informal information about community needs. These informal assessments were reported by more than half of the respondents. Mechanisms for collecting this information included:

- residents contacting the emergency management office, phone bank, or hotline directly to articulate their needs and get connected to resources;

- the LHD collecting information on community needs while conducting Harvey outreach efforts;

- elected officials conveying community needs to the entities conducting recovery activities;

- the LHD identifying needs based on anecdotal information provided by the social services organizations working with the community; or

- the LHD collecting observational data on housing conditions in the community (e.g., the number of individuals living in tents and the number of tarps being utilized as roofs).

Nearly half the respondents reported conducting or relying on data gathered through formalized needs assessments, including conducting a post-Harvey CASPER or other needs assessment or relying on CASPER data collected after a previous disaster. However, respondents did not describe conducting follow-up formalized assessments to identify ongoing community needs or to evaluate their recovery efforts. Several respondents also indicated that their recovery-monitoring processes included surveillance of health outcomes that could be related to Harvey, such as respiratory illnesses related to mold exposure, suicides, and infectious diseases. One respondent reported conducting epidemiological investigations in permanent shelters to detect and monitor illness.

Additionally, several respondents reported that they or their partner organizations conducted damage assessments. These assessments included: FEMA assessors examining the damage and reporting to the county the number of homes affected; academic institutions utilizing drones to observe flooding and damage patterns; epidemiological teams “eyeballing” structural damage; the flood administrator identifying damaged homes; and the LHD monitoring hospital repairs and Harvey’s effects on the level of care provided at the hospitals. Finally, a few respondents reported tracking recovery progress through their structured recovery groups and partners. For instance, two respondents described “report-out” meetings in which their partners described their progress. Another respondent described utilizing the American Red Cross’s Coordinated Assistance Network to track client information and needs across partner organizations.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

In this section, we detail the challenges and lessons learned that respondents described during their interviews.

Resources and Capacity

Nearly all respondents encountered resource-related difficulties. Most commonly, respondents described an overall lack of resources. For example, one respondent described a “watering down of support services that typically will be in place for an adequate amount of time” due to the need to dedicate resources to hurricane response and recovery in Florida and Puerto Rico. These resources included lack of physical resources—such as long-term and functional/access needs shelters—as well as inadequate staff and responder capacity; this included evacuation and rescue teams that were “maximized, stressed out,” as well as a lack of mental health professionals, health inspectors, health care professionals, and staff to conduct shelter surveillance. As such, respondents described learning lessons related to the types of resources they would like to have on hand to aid response and recovery, such as functional and access needs shelters, high water vehicles, and mental health professionals.

Respondents cited small tax bases, the chronic underfunding of public health, and a lack of volunteers and resources as undermining their abilities to carry out all of their recovery activities. Half of the respondents described delays in receiving resources, including vaccination clinic supplies, D-SNAP, water, generators, and debris removal services. Respondents identified opportunities for addressing this challenge, including streamlining the processes for requesting resources, developing a guide that describes where and how to procure various resources, and identifying which partner organizations will be able to furnish resources, staff, and services in the event of a disaster.

Respondents also described difficulties procuring medications for their populations, a lack of financial resources for mental health activities, a lack of volunteers, and difficulty identifying funding sources. A couple of respondents described difficulties coordinating resources, and one said that their community needs donations and volunteer coordinators to help address this challenge.

Communication

Nearly all respondents described communication challenges—both with partners and with the public—and identified lessons learned related to the challenges they described.

Partners—Health Care

Several respondents cited a lack of communication with their health care partners as the cause of health care facility closures during Harvey. This included dialysis centers, pharmacies, and other facilities. As a result of these closings, several respondents identified a need to: strengthen their relationships with their health care partners prior to the disaster; more clearly delineate roles and responsibilities with health care facilities; improve communication; and develop agreements and plans that ensure that these facilities do not close during future disasters.

Partners—Non-Health Care

Respondents also described a lack of longstanding relationships with partners due to staff turnover, both at partner organizations and at LHDs. Additionally, a couple of respondents reported that their roles and responsibilities, as well as those of their partners, were not clearly defined prior to the disaster. As one respondent noted, “there was kind of a disconnect between the actual shelter plan of record and what the services that [partner organization] provided in the shelter.” As such, respondents described the need for improved and more frequent discussion with partners to outline the roles, responsibilities, and expectations of partner organizations and health departments alike. Similarly, respondents highlighted the need for better communication with partners around the resources to be provided by each organization, and the need for other agencies to become more familiar with ICS structure and terminology.

The Public

Respondents described difficulties communicating effectively with the public before and after Harvey. Several respondents indicated that it was difficult to assess community needs and/or to communicate the resources available for addressing these needs. In particular, one respondent described their lack of alternative communication strategies to reach community members without access to the Internet or cell phones, noting, “no matter how hard we try not everybody is going to call us. Not everybody is going to reach us…we need to find a way to be able to get the word out to our citizens more quickly and more effectively, and to use more methods and not just simply rely on, not everybody has the Internet. So not everybody can get to Facebook. Not everybody has a phone or a cell phone. So we've got to find other ways to be able to get the word out.”

A couple of respondents characterized their community outreach as lacking. Two respondents noted that they should have better prepared the community on maintaining access to their medications, while others identified the need for better public education concerning: drowning and water safety; mold remediation; transitions to life after leaving the shelters; the role of public health and related resources and services; and how to function without cell phones. A couple of respondents also highlighted the need to improve outreach and communication to specific segments of the population, namely, individuals with functional and access needs, cultural and ethnic minorities, and those with limited English proficiency.

Planning

A majority of respondents also reported insufficient response and recovery planning and identified potential improvements for their planning processes. Respondents described lacking plans for recovery, as well as for specific elements of their response—such as shelter operations, drive through mass vaccination clinics, addressing functional and access needs, and medical waste disposal. Additionally, nearly half of the respondents emphasized the importance of maintaining flexibility when planning for and responding to disasters. Respondents cautioned against becoming too comfortable in responding to specific disasters, as the need to alter plans and staffing could arise depending on the disaster’s characteristics. Respondents also described the need to conduct the following activities prior to a disaster: develop a plan for a centralized volunteer check-in center; streamline response decision-making processes; identify individuals with functional and access needs; develop supply checklists and identify resources; plan to shelter medical staff close to recovery centers; and establish processes for credentialing providers. One respondent described being too reliant on “on the fly” messaging and activities due to their lack of a written recovery plan.

Lessons Learned from Prior Disasters

Most respondents described applying lessons learned from prior to disasters to their Harvey response and recovery. One respondent noted that their experiences with Hurricane Katrina led them to understand that after big disasters, “communities are never the same…your normal is over with when you're hit with a storm like this” Several respondents indicated that they had made improvements in their response and recovery capabilities, including: repairing infrastructure quickly; stockpiling mold remediation supplies; and improving emergency operations center functioning and public notification and supply management systems. Prior disasters also helped respondents shape their response and recovery priorities, such as increasing their focus on mental health, quickly restoring drinking water and sanitation, offering an adopt-a-family program, and keeping communities together during rebuilding. One respondent noted that they developed their long-term recovery group as a result of a prior disaster, while another indicated that seeing the success of the Neighborhood Restoration Centers utilized in previous disasters influenced their decision to implement the model in their jurisdiction. Finally, one respondent said that their experience with prior disasters demonstrated that they excelled at response but needed to improve their recovery processes.

Processes for Learning Lessons

Respondents’ communities employed a host of strategies to identify lessons learned from Harvey. The most frequent process for identifying lessons learned was conducting an after-action review or hotwash with partner organizations. A couple of respondents described conducting reviews of their plans and updating them with lessons learned. Respondents also described: reviewing flood data to improve their evacuation plans; asking residents to provide feedback on the government’s performance; and speaking with other states to identify lessons learned.

Possible Application of Results

The findings from this study provide valuable insight on the extent to which cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary disaster recovery has been attentive to health, wellbeing, and resilience promotion. The study illuminates barriers to and facilitators for leveraging recovery resources to build healthy, sustainable, and resilient communities. Results can inform strategies used by emergency and community planners and responders to better coordinate a cross-sectoral, community-wide disaster recovery that is forward thinking and that enhances community resilience in the long-term. This study indicates that LHDs would benefit from technical assistance, support, and resources designed to facilitate their ability to work across sectors and incorporate public health considerations into disaster recovery.

Future Work

We are in the process of utilizing the protocol developed through this study to conduct interviews with county LHDs affected by wildfires in Northern California in 2017. Upon completion of the interviews, we will compare the findings from the interviews with California LHDs with those from the Texas LHDs to assess differences in their approaches to recovery and building resilience. Furthermore, we hope to use the results of this study to inform the development of a quantitative data collection tool to assess the extent to which health considerations are being incorporated in disaster recovery processes across communities and disasters, with the ultimate goal of developing and disseminating a toolkit to promote health integration into disaster recovery.

References

-

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2018a. “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview.” https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/ ↩

-

Melillo, Jerry M., Richmond, Terese (T.C.), and Gary W. Yohe, eds. 2014. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/J0Z31WJ2. ↩

-

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) [R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer, eds.]. 2014a. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/syr/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf ↩

-

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) [A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] (Field, C.B., V. Barros, T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S.K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P.M. Midgley, eds.)]. 2012b. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/special-reports/srex/SREX_Full_Report.pdf ↩

-

Chandra, Anita, Joie Acosta, Stefanie Howard, Lori Uscher-Pines, Malcolm Williams, Douglas Yeung, Jeffrey Garnett, and Lisa S. Meredith. 2011. "Building community resilience to disasters: A way forward to enhance national health security." Rand health quarterly 1, no. 1. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2011/RAND_TR915.pdf ↩

-

NRC (National Research Council). 2012. Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13457 ↩

-

Chandra, Anita. 2014. “Considerations for community health in disaster recovery.” Paper presented at IOM Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services: Meeting Three, Washington, DC, April 28-29, 2014. http://www.nationalacademies.org.../Chandra.pdf ↩

-

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 2016. National Disaster Recovery Framework, Second Edition. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1466014998123-4bec8550930f774269e0c5968b120ba2/National_Disaster_Recovery_Framework2nd.pdf ↩

-

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2011. Public Health Preparedness Capabilities: National Standards for State and Local Planning. https://www.cdc.gov/phpr/readiness/00_docs/DSLR_capabilities_July.pdf ↩

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. 2015. National Health Security Strategy and Implementation Plan. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/authority/nhss/Pages/strategy.aspx ↩

-

Wulff, Katharine, Donato, Darrin, and Nicole Lurie. 2015. "What is health resilience and how can we build it?". Annual review of public health, 36: 361-374. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122829 ↩

-

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2015. Healthy, Resilient, and Sustainable Communities After Disasters: Strategies, Opportunities, and Planning for Recovery. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18996. ↩

-

Dzau, Victor J, Lurie, Nicole, and Reed V. Tuckson. 2018. "After Harvey, Irma, and Maria, an Opportunity for Better Health—Rebuilding Our Communities as We Want Them,” American Journal of Public Health, 108: 32-33. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304194 ↩

-

Kates, Robert W., Colten, Craig E., Laska, Shirley, and Stephen P. Leatherman. 2006. "Reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: a research perspective." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(40): 14653-14660. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0605726103 ↩

-

Rubin, Claire B. 2009. "Long Term Recovery from Disasters – The Neglected Component of Emergency Management." Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 6 (1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1616 ↩

-

Olshansky, Robert B., Hopkins, Lewis D., and Laurie A. Johnson. 2012. "Disaster and Recovery: Processes Compressed in Time." Natural Hazards Review 13(3) 173-178. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000077 ↩

-

NACCHO (National Association of City and County Health Officials). 2014. "Local Health Department Strategies for Implementing Health in All Policies". https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Programs/Community-Health/factsheet_hiap_dec2014-1.pdf ↩

-

Hall, Richard L., and Peter D. Jacobson. 2018. "Examining Whether The Health-In-All-Policies Approach Promotes Health Equity." Health Affairs 37(3): 364-370. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1292. ↩

-

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2018b. “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Table of Events.” https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/events/US/1980-2017 ↩

-

Shultz, James M., and Sandro Galea. 2017. "Preparing for the next Harvey, Irma, or Maria—addressing research gaps." New England Journal of Medicine 377 (19): 1804-1806. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1712854. ↩

-

NWS (National Weather Service). 2017. "Hurricane Harvey Info.” https://www.weather.gov/hgx/hurricaneharvey ↩

-

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2018c. “Fast Facts: Hurricane Costs.” https://coast.noaa.gov/states/fast-facts/hurricane-costs.html ↩

Kennedy, M. (2018). Building Back Better: Understanding How Health Considerations are Incorporated into Local Post-Disaster Recovery Implementation (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 277). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/building-back-better-understanding-how-health-considerations-are-incorporated-into-local-post-disaster-recovery-implementation