Dimensions of Vulnerability, Resilience, and Social Justice in a Low-Income Hispanic Neighborhood During Disaster Recovery

Publication Date: 2018

Abstract

Disasters expose social structures that put marginalized communities in harm's way. The impacts of Hurricane Harvey on low-income Hispanic communities in Houston, Texas, illustrate patterns of historical inequalities that have led to poor minorities in the United States being disproportionately exposed to environmental risks. In disaster contexts where inequality increases vulnerabilities and reduces adaptive capacities and resilience for marginalized groups, it can be argued that effective disaster recovery initiatives call for stakeholders to better understand and explicitly address structural barriers to resilience rooted in social injustice. This research explores post-Harvey disaster recovery as a lived experience at the household level from the perspectives of community residents and as an issue of neighborhood organization at the community level from the perspective of community advocacy groups. The project considers the collective conversation surrounding these themes six and 12 months after the storm to assess how community residents and local advocacy groups prioritize and address needs during the crucial first year of recovery efforts after the storm. This report details the preliminary findings after the first field visit.

Introduction

The materially destructive and socially disruptive impacts of natural disasters are often shaped by historical processes whereby human practices have caused systemic inequities that are aggravated in times of crisis. As a result, the severity of disaster impacts runs parallel to the inequitable distribution of disaster risk across lines of gender, race, class, and ethnicity (Barrios 20171). The extent to which societies allocate resources and support capacities in a socially just way determines who is safe, who is at risk, and how various institutions manage risk to ensure the safety of their populations. The impacts of Hurricane Harvey on low-income Hispanic communities in Houston, Texas, illustrate patterns of historical inequalities that have led to poor minorities in the United States being disproportionately exposed to environmental risks. In disaster contexts where inequality increases vulnerabilities and reduces adaptive capacities and resilience for marginalized groups, it can be argued that effective disaster recovery initiatives require stakeholders to better understand and explicitly address the structural barriers to resilience rooted in social injustice.

The first year after a disaster strikes is crucial to preserving well-being and empowering communities to ensure their participation and agency in shaping their recovery (Lehtola and Brown 19982). This project considers the collective conversation surrounding these themes six and 12 months after the storm to assess how community residents, local advocacy groups, and official government recovery and aid organizations prioritize and address needs during the crucial first year of recovery efforts. This report details the findings of the first field visit, which was conducted in March 2018 and focused on households and advocacy groups.

This report first outlines the anthropological perspectives on vulnerability, resilience, and social justice that serve as a theoretical framework for this research and then identifies the research problem and details the research activities and methodologies used to conduct this research. The report then continues with a discussion of preliminary field work findings, followed by concluding observations.

Theoretical Framework: Anthropological Perspectives on Vulnerability, Resilience, and Social Justice

Approaching disaster recovery through an anthropological lens is an effective way to address issues of vulnerability and resilience rooted in social injustice. The anthropology of disasters highlights the role of culture, social organization, and the compatibility of sociopolitical recovery institutions with recovering minority communities (Faas and Barrios 20153) to understand the impacts of natural phenomena on human populations. At the same time, anthropological theories and methods effectively identify the real-world impacts that expert practices have on marginalized groups, opening them up to reflection and improvement (Browne 20154; Faas and Barrios 2015). Anthropological theories regarding vulnerability, resilience, and social justice can inform more inclusive and effective disaster recovery initiatives.

Vulnerability refers to “the characteristics of a person or group and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from the impacts of a natural hazard (Wisner et al. 2004, 3-485).” Some groups of people are more prone than others to damage, loss, and suffering in the context of various hazards. These variations in vulnerability are due to factors such as differences in wealth and social class, occupation, ethnicity, gender, disability, health, age, and status. Furthermore, “vulnerability can be measured in terms of damage to future livelihoods, and not just as what happens to life and property at the time of the hazard event (Wisner et al. 2004, 3-48).” The temporal dimension of vulnerability is a key consideration because current decision-making processes will shape future patterns of vulnerability in a similar way to present-day vulnerabilities, which are often rooted in poor decisions of the past.

Recent work on vulnerability in the social sciences focuses on incorporating the cultural, psychosocial, and subjective impacts of disasters into more conventional measures of disaster impact and vulnerability (such as mortality, morbidity, and property damage) to leverage qualitative and quantitative vulnerability research in planning and policy-making. At the same time, perspectives are shifting from “vulnerable groups” to “vulnerable situations” that people move into and out of over time, viewing people as agents that act on their capacities to protect themselves rather than as passive victims of their environment limited by embodied vulnerabilities (Wisner et al. 2004, 13-15). This shift encourages an approach that emphasizes the adaptive capacities of individuals, human communities, and larger societies in the face of adversity (Norris et al. 20086).

Norris et al. (2008) define resilience as “a process linking a set of adaptive capacities to a positive trajectory of functioning and adaptation after a disturbance,” enabling people to weather stresses and adapt to their aftermath in a way that allows them to retain their basic social structures and identities. In bringing this definition into practice, resilience must be conceptualized as an ability or a process rather than an outcome, and as adaptability rather than stability. In other words, resilience is to be supported rather than achieved, by enabling a flexible process whereby people link key resources and capacities to final adaptation outcomes.

Variations in vulnerability and resilience result from conditions of inequality that determine the resources and capacities that people have at their disposal to prepare for, cope with, and recover from the impacts of natural hazards. Social justice, generally viewed as “a fundamental axiom of value in political and economic life (Bankston 20107),” rests on the principle of capital redistribution to improve the circumstances of disadvantaged groups, reducing their vulnerabilities and supporting their resilience as a matter of human rights. In line with Norris et al.’s conceptualization of resilience as an ability or a process, Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach to human rights considers what people are able to be or do as a starting point to better understand the barriers that societies have erected against full justice for those in positions of disadvantage (Nussbaum 20038). In order to address these barriers, social justice emphasizes the importance of context, advocacy, leadership, and culturally competent care (Clingerman 20119) to support resilience and well-being.

Research Problem: When Historical Disadvantage Meets a Natural Hazard

This research project is aimed at better understanding how disaster recovery processes can effectively support resilience and mitigate vulnerabilities of historically disadvantaged Hispanic communities in the face of environmental hazards. By exploring post-Harvey disaster recovery in the Hispanic community of Port Houston (Houston, Texas), I hope to generate insights regarding how community residents address disaster recovery as a lived experience, and how community advocacy groups address disaster recovery at the community level.

Historical inequalities have led to poor minorities in the United States today being disproportionately exposed to environmental risks (Bullard 200010; Mohai et al. 200911; Mohai and Bryant 199212; Peterson and Maldonado 201613). In the case of Hispanic communities, historical minority exclusion and institutionalized economic disadvantages have led to a higher risk of socioeconomic insecurity for this segment of the population. Undocumented status aggravates this insecurity by limiting access to formal employment, increasing workplace risk, and reducing access to benefits such as health insurance and other social services, with harmful effects on Hispanic families' economic, physical, and emotional well-being (Angel and Angel 200914; Dawson 201615; Peterson and Maldonado 2016).

Disasters often expose social structures and hierarchies that place marginalized communities in harm's way. In August 2017, Hurricane Harvey exacerbated longstanding social, political, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities faced by Hispanic communities in the city of Houston, Texas. Surpassing the Texas tropical cyclone rainfall record, Harvey's destructive winds and 50 inches of rainfall caused damages estimated by government officials at over $180 billion (Parraga and McWilliams 201716). The floodwaters drained into the Houston Ship Channel (Hersher 201717), an area where low land prices, combined with Houston's lack of zoning regulations (Walsh 201818), have historically attracted both low-income residents seeking affordable housing and industrial facilities seeking to minimize operational costs. As a result, many neighborhoods in the area are home to low-income, largely Hispanic communities (Mankad 201719) and are located within one mile of an industrial facility, including hazardous waste generators and treatment centers, and dischargers of known cancer-causing and neurotoxic substances (City of Houston 200320; Whitworth et al. 200821). Emergency shutdowns and subsequent startups of these industrial facilities due to the storm caused the release of an estimated 4 million pounds of excess pollutants into the air and as toxin-laden wastewater (Schlanger 201722). After floodwaters drained, the contaminants they carried were likely left behind (Hersher 2017), further exposing portside communities along the ship channel.

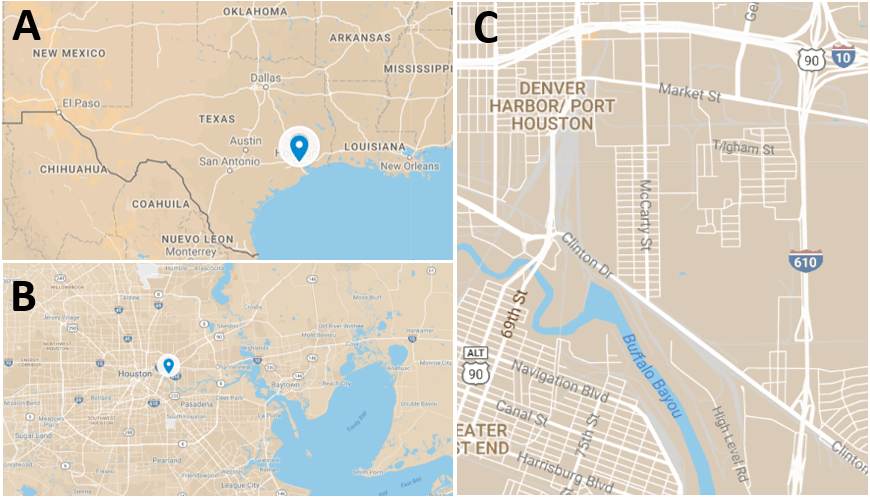

Port Houston

The neighborhood of Port Houston is a portside community located in eastern Houston, Texas. Of Port Houston’s 5,000 residents, 91 percent (Meier 201823) are Hispanic, and over half of community residents live below the poverty line (City of Houston 2003). The neighborhood consists of a grid of approximately 20 streets that are traversed by McCarty Street, an industrial access road that connects the neighborhood to Market Street and the I-10 freeway to the north, and to Clinton Drive and the 610 freeway to the south (see Figure 1). These roads are the only access points to the neighborhood. Port Houston is officially considered an area of minimal flood hazard (FEMA 201724), and community residents emphasize that the neighborhood has not traditionally been prone to flooding during hurricanes. The experiences of Port Houston residents during and after Hurricane Harvey speak to the severity of the storm and reflect the wide range of factors that can shape household capacity to prepare for, endure, and recover from a natural disaster.

Figure 1. Maps showing the location of Port Houston (A. Location of Port Houston marked on the state of Texas map; B. Location of Port Houston marked on the City of Houston; C. The Port Houston neighborhood consists of a series of small streets traversed by McCarty Street, which connects the community to Market Street on the North and Clinton Drive to the South. These are the only access points to the neighborhood.) 25

Figure 1. Maps showing the location of Port Houston (A. Location of Port Houston marked on the state of Texas map; B. Location of Port Houston marked on the City of Houston; C. The Port Houston neighborhood consists of a series of small streets traversed by McCarty Street, which connects the community to Market Street on the North and Clinton Drive to the South. These are the only access points to the neighborhood.) 25

Port Houston residents state that the neighborhood endured continuous rains for one week when Hurricane Harvey struck the city. McCarty Street and its connecting roads and freeways were submerged, making travel into and out of the neighborhood impossible until the floodwaters receded. Residents commented that their streets and homes flooded to varying degrees during the storm, ranging in depth from a few inches to up to four feet. Clogged drainage ditches contributed to this issue. Port Houston is considered a food desert, with a significant number of low-income residents living more than one mile away from a supermarket and lacking vehicle access to seek alternative food sources elsewhere (USDA 201526). Residents who ran out of food while waiting for floodwaters to recede had to resort to expensive, poorly stocked local convenience stores. Neighborhood residents dedicated up to three weeks to cleanup activities after the storm. While most considered that it took one month for the neighborhood to return to a state that they recognized as normalcy, many people expressed that Harvey’s impacts, including debris in neighborhood yards and structural damages to homes, were still visible six months after the storm.

As a context of disaster recovery heightens the challenges that low-income Hispanic families contend with in their daily lives, it is crucial for disaster response and recovery organizations to identify and address the structural, socioeconomic, and cultural barriers that leave vulnerable populations to forge their own paths to recovery outside the reach of official channels (Angel and Angel 2009; Dawson 2016; Hauslohner 201727). In such circumstances, there is a risk that post-disaster response lacking cultural sensitivity and historical perspective will merely replicate and exacerbate existing patterns of disadvantage (Faas and Barrios 2015; Norris et al. 2008). In order to effectively address vulnerabilities and support the recovery and rebuilding of more resilient communities, organizations must consider how the distribution of disaster impacts across lines of ethnicity and socioeconomic disadvantage determine the types of support that Hispanic families in communities such as Port Houston need to recover from the impacts of Hurricane Harvey.

Research Activities and Methodology

In order to examine the various dimensions of vulnerability and resilience that shape disaster experience and recovery, this study includes interviews with eight Hispanic women who are heads of households and three community-based advocacy groups. Field work for this project is divided into two phases to capture the progression of the community’s discourse surrounding themes of vulnerability, resilience, and social justice at the 6- and 12-month marks during the crucial first year of recovery. Phase 1 investigates disaster recovery as a lived experience at the household level from the perspective of community residents, as well as from the perspective of community-based advocacy groups that are responding to residents’ needs throughout this process. Phase 2 will follow up with community residents and community-based advocacy groups to assess the progression of the recovery process from the 6- to the 12-month mark after the storm. In this report, I will detail the preliminary findings of the Phase 1 field visit, which was conducted in March 2018.

The author conducted field work in both English and Spanish, based on participant preference, to address language barriers. The following methods were used for this study:

Participant observation involves observing and engaging in daily community activities to gain insight into social, cultural, political, and economic dynamics within communities and in the broader city context that shape interactions among and between community residents and community-based advocacy groups. This method also helps to contextualize more systematic data collection;

Semi-structured ethnographic interviews that explore aspects of household and community life before, during, and after Hurricane Harvey, as well as how community-based advocacy groups engage with the immediate and long-term needs and challenges that arose during and after the storm;

Household surveys conducted with community residents alongside ethnographic interviews to track changes in household well-being and perceived progress and recovery between the 6- and 12-month marks; and

Free-listing exercises conducted with community residents alongside ethnographic interviews to determine overarching experiences of vulnerability, resilience, and empowerment across households.

The research protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Colorado State University. See Appendix A for data collection instruments.

Results and Discussion

This section details the key takeaways from the preliminary findings of the Phase 1 field visit, which the author conducted in March 2018. The main themes include the importance of social capital and information resources to support disaster preparedness and recovery; social justice and the root causes that shape household vulnerabilities; and the ways in which community advocacy organizations respond to immediate community needs while fostering long-term development to minimize vulnerability and support resilience in the face of future disasters. It is important to note that the findings discussed in this section are preliminary. An in-depth qualitative data analysis using Maxqda will be conducted after Phase 2 of the research project to identify broader themes and patterns. Furthermore, while the information gathered through this small number of interviews cannot be generalized, it does suggest themes for more expansive research.

Social capital and information for disaster preparedness and recovery

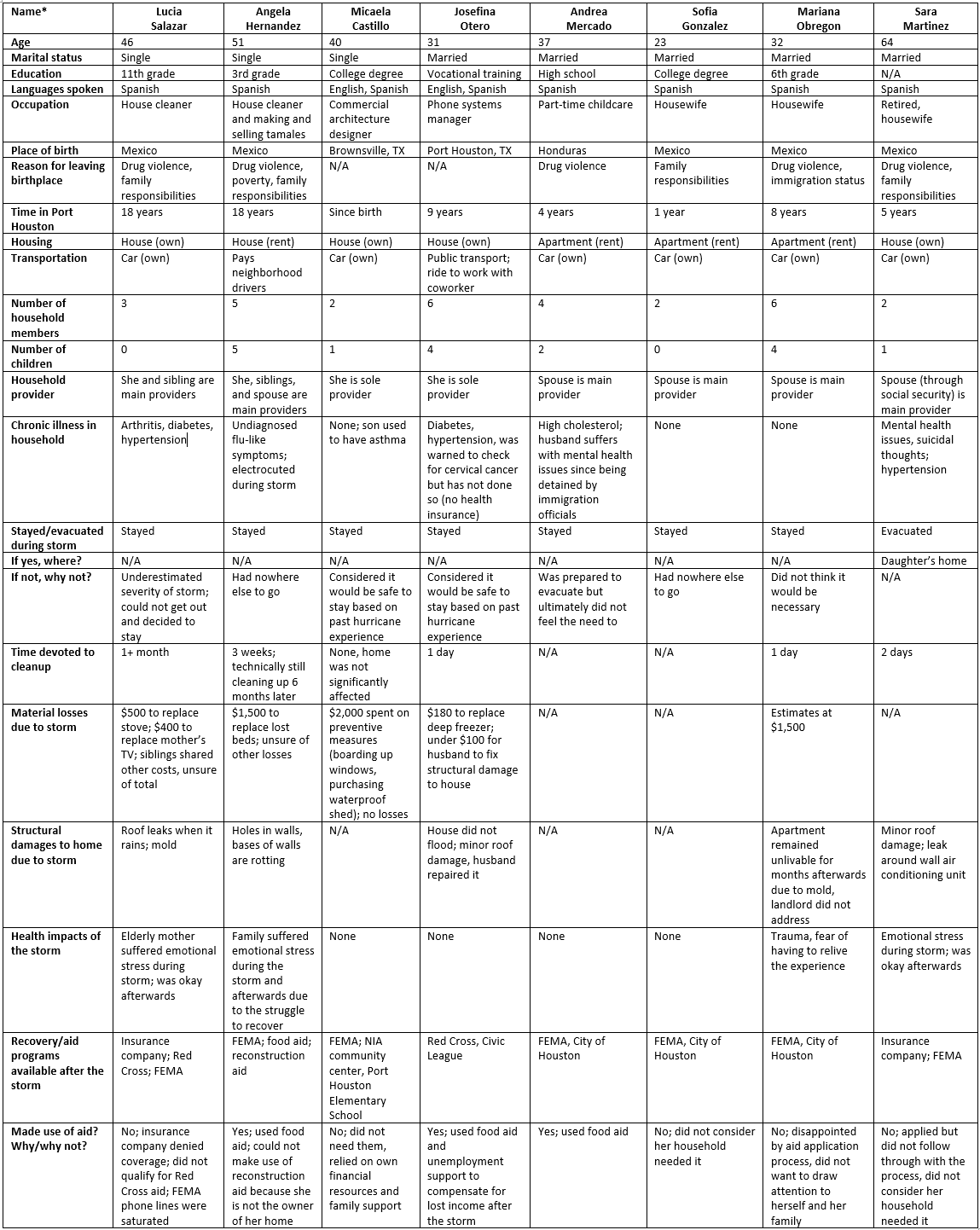

Natural disasters can be considered the combination of natural hazards, the vulnerability of people, and their ability to respond to risk. Interviews with eight Port Houston women (see Table 1) revealed the ways in which household experiences during Hurricane Harvey were influenced by household disaster preparedness, which was itself shaped by household access to a combination of social capital, information, and material and financial resources. At the same time, these factors influenced how Harvey impacted each household and what needs had to be met to support household recovery and resilience.

Table 1. Port Houston women interviewed for this study.

*Names have been changed using a random name generator to protect the privacy of research participants.

Disaster preparedness consists of the measures that enable individuals, households, communities, and societies to effectively respond and quickly recover when disasters strike (Sadeka et al. 201528). Disasters are usually unexpected, making disaster preparedness key for the mitigation of human, material, economic, and environmental impacts and losses that may exceed the ability of affected communities to rely on their own resources to cope (UNISDR 201529). Several women expressed their reliance on family and community networks of support to prepare for and recover from the storm, highlighting the potential of social capital to support disaster preparedness, response, and recovery at individual, household, and community levels (Dokhi et al. 201730). Social capital refers to the norms and networks that facilitate cooperation among people either within or between groups. Developing and strengthening social capital is essential to human development and disaster preparedness, improving people's access to adaptive resources and capacities (Dokhi et al. 2017).

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) also play a major role in supporting resilient behaviors and strengthening social capital in disaster contexts by enabling people to maintain social collaborations and obtain information in an otherwise chaotic environment (Semaan et al. 201231). During Hurricane Harvey, Port Houston residents relied on mobile phones, internet applications, and Spanish-language television channels to communicate and stay informed. This allowed residents to increase situational awareness, communicate with family members and coworkers in other neighborhoods, connect with family members outside the country, and negotiate recovery activities.

Residents who were born in Port Houston or who have lived in the neighborhood most of their lives often considered risk awareness and disaster preparedness as individual responsibilities. They had taken precautionary measures to protect their homes from structural damage in the event of a flood, such as raising their homes or digging drainage trenches to direct floodwaters away from their house. They expressed that their experience with Hurricane Harvey had reinforced their view of Port Houston as a resilient community and strengthened their desire to stay in the neighborhood. These residents value their knowledge and understanding of the area’s potential risks, being able to rely on extended family networks for support, and having access to their own material and financial resources to mitigate risk and minimize damages and loss in the wake of a storm.

The women highlighted the importance of having a network of friends and family members to ensure that more vulnerable family members, such as children and the elderly, were safe and had everything they needed. For residents who were not born in Port Houston, being in touch with family members in their countries of origin or in other parts of the United States was a source of comfort and emotional support. It is worth noting that, while most of the women maintain friendly relationships with their neighbors, all of them were reluctant to reach out to people outside of their immediate family circles for support during the storm and its aftermath. Several households, particularly those that did not have extended family networks in the neighborhood, relied on government aid and donations to provide for their families in the days and weeks following the storm. It can be argued that effective aid structures are an important source of support for households lacking the resources and social capital to cope with disaster impacts that exceed their adaptive capacities.

Social Justice and Disaster Recovery

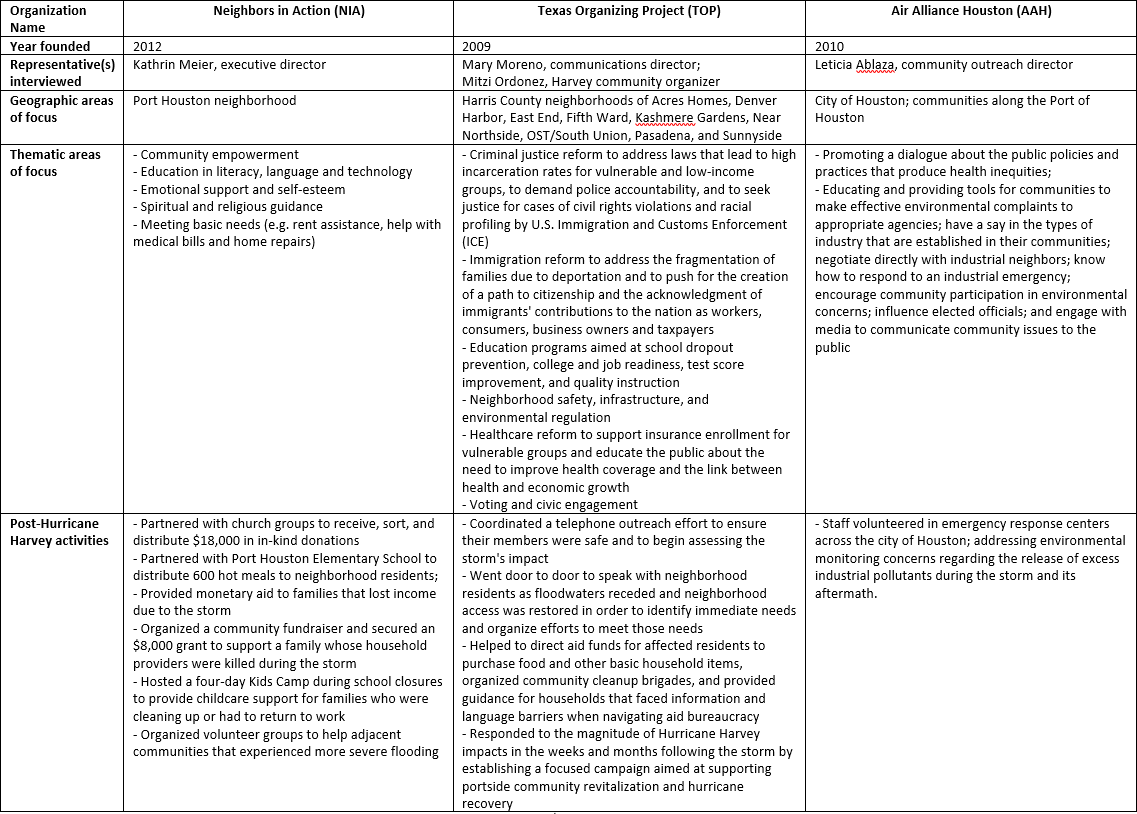

Interviews with three community advocacy organizations (see Table 2) illuminated the issues that affect the daily lives of Port Houston residents, which are exacerbated when disasters like Hurricane Harvey strike. These organizations use a social justice lens to address what Peterson and Maldonado (2016) call the "consequences of layered disasters"—that is, the web of interconnected social, political, and economic disadvantages that combine to exacerbate vulnerabilities and limit people's abilities to respond and adapt to disasters and their aftermath. A social justice framework promotes an understanding of the life contexts of vulnerable groups, based on fairness, tolerance, equity, knowledge, and respect for human dignity (Clingerman 2011; Douglas et al. 200932). This approach identifies the inequalities that marginalize and disenfranchise vulnerable populations, limiting their capacities to perform or to reach a valued state of well-being throughout a lifetime (Clingerman 2011; Powers and Faden 200633). Furthermore, it questions whether the distinct patterns of disadvantage affecting vulnerable groups are a result of human choice or equality of access, and seeks to identify relevant policies and institutional structures that can address inequalities to improve the choices available to marginalized groups (Clingerman 2011).

Table 2. Community-based advocacy organizations interviewed for this study.

The representatives of these community organizations explicitly acknowledged the correlations between disaster vulnerability and historical disadvantages faced by Hispanic communities. Moreno emphasized that Texas Organizing Project (TOP) "[focuses] on organizing communities of color, and right now, in Houston that means organizing people impacted by Harvey (Moreno 201834)." During the storm, as flooding prevented people from leaving their homes and neighborhoods, the staff from these community organizations relied on mobile phone and social media connections to coordinate outreach efforts to ensure their members were safe and to begin assessing the storm's impact. As floodwaters receded and neighborhood access was restored, canvassers went door-to-door to speak with neighborhood residents in order to identify immediate needs and organize efforts to meet those needs. For instance, the organizations distributed hot meals, helped to direct aid funds for affected residents to purchase food and other basic household supplies, organized community cleanup brigades, and provided guidance for households that faced information and language barriers when navigating aid bureaucracy (Meier 2018; Moreno 2018; Ordonez 201835). Meier emphasized the importance of community ownership over these recovery activities, stating that:

I think the best thing is just how the [neighborhood] moms responded, and just knowing that they have it all under control. I couldn't get out of the house—they were here. They took over, and that's good, that's much better than if I did it... The idea is really that it is their community center. [We avoid] a paternalistic kind of approach. It can easily become, “Oh, this poor neighborhood, and oh, these poor kids." It's not. I mean, it lacks resources... but that doesn't mean we come here as the saviors. We're just partnering, it's really their community center. It should be what the community wants it to be, and we just bring the resources in, what we need. I have several moms who have been key, which is very practical because sometimes, especially when I was not able to come here, they organized everything (Meier 2018).

Hurricane Harvey's impacts were not uniform across neighborhoods; rather, they manifested in varying forms and degrees of severity within neighborhoods. In some cases, impacts varied between households on the same street. Ordonez commented on the need to transform community perceptions of storm impacts exclusively in terms of flooding—a perception that is arguably reinforced by official aid organizations' approach to property damage assessment and aid allocation based on floodwater depth. TOP worked to raise awareness in affected neighborhoods regarding the various ways that Harvey could have impacted their households, such as affected livelihoods and lost income; structural damage to homes; expenses related to home repairs and replacement of damaged belongings; and stress on household physical and mental well-being (Ordonez 2018).

Layered Disasters and Root Causes of Vulnerability

Undocumented Immigration Status

Community-based organization representatives considered undocumented immigration status to be a key determinant of household vulnerability and resilience. Undocumented people in the United States face additional challenges during disaster recovery, including a lack of access to government assistance to rebuild their homes, obstacles in navigating aid bureaucracy, and being at increased risk of having their vulnerabilities exploited. Due to the sensitivity of the subject, this study did not inquire about Port Houston residents' immigration status during interviews. Meier (2018) commented on the difficulty of broaching the subject with neighborhood residents, emphasizing the importance of building relationships and trust as a prerequisite for addressing the issue.

Just from my personal survey, with the moms that I know—and it's only because we have this relationship of trust that I can ask those things, you know, because we've known each other for five years. People tell me, 'You asked them that?!' But I mean, they have been to my birthday parties, you know? [laughs] We know each other well. So I would guess 90 percent of the moms [that we work with] are undocumented. That doesn't mean 90 percent of the children, because some were born here, but... my guess would be 70-80 percent of the children are undocumented. And this is a neighborhood where, if they're not undocumented, they [often have] political asylum (Meier 2018).

In Houston, the ongoing immigration enforcement legislation debate under Texas Senate Bill 4 (SB4) creates an uncertain and hostile climate for minority families that were impacted by Hurricane Harvey (Aguilar 201736; Meier 2018; Ordonez 2018). SB4 is a controversial law that allows police to question the immigration status of anyone they detain or arrest; requires police chiefs and sheriffs to cooperate with federal immigration officials by honoring requests for deportation; and pushes to punish local officials for adopting, enforcing, or endorsing policies that stand against the bill (ACLU 201837). Fear of deportation keeps undocumented families from leaving dangerous living conditions or making use of official support mechanisms (Ablaza 201838; Hauslohner 2017; Moreno 2018). While undocumented residents are especially fearful of calling attention to themselves and their families, Hispanic communities in general tend to distrust government assurances that they will not be victimized because of their ethnicity or their socioeconomic and legal status, preferring to rely on family, friendship, and neighborhood relationships for support (Ablaza 2018).

There's people who are just, in our current political climate, are just scared to call any attention at all. Even if they have maybe a child that's born here, there's just this fear to just come out and say, 'Here I am.' And I mean, this has probably nothing to do with Harvey relief, but at the same time that Harvey happened, Texas allowed the... SB4, so that just put additional stress on people. While all this is happening, also all of a sudden they're targeted (Meier 2018).

Housing

Undocumented immigration status can shape housing circumstances by restricting access to quality housing and increasing the likelihood that families will settle in less-advantaged neighborhoods where perceived fears of detection are minimized (Hall and Greenman 201339). Undocumented householders are less likely to be homeowners than documented migrants, tend to live in more crowded homes, report greater structural deficiencies with their dwellings, and express greater concern about the quality of public services and environmental conditions in their neighborhoods (Hall and Greenman 2013; Moreno 2018). Community organizations working in neighborhoods like Port Houston have been closely following the systemic issues at the city level that shape housing challenges for both renters and homeowners.

Houston's susceptibility to flooding, coupled with insufficient housing inspectors and poor enforcement of housing regulations, results in water damage from repeated flooding events that often goes unaddressed in rental complexes. At the same time, a lack of affordable housing in the city drives vulnerable groups to tolerate subpar living conditions and increases their risk of having their vulnerabilities exploited. For example, Moreno and Ordonez recounted various instances when TOP mediated conflicts involving landlords that refused to repair rental units that were rendered uninhabitable by the storm and used threats to keep tenants from breaking their leases. In addition, homeowners in poor Houston neighborhoods face increased flooding risk due to poor maintenance of clogged drainage ditches and crumbling infrastructure. Furthermore, homeowners risk losing their homes as a result of new building requirements that place the burden of flood mitigation on individual homeowners. Finally, the struggle between community residents and urban developers regarding the allocation of recovery aid funds highlights communities' fear of gentrification and being driven out of their communities after a disaster strikes.

If you have a certain percentage of damage to your home, you have to get a permit to repair it and they won't give you the permit [unless your repair plans] include raising your home. Flood prevention [should be] a government function, it shouldn't be up to each individual. Raising homes can cost $100,000. How are you gonna get $100,000 to raise your home? We have a member who lives near the bayou... her family bought her house 30 years ago for like twenty-something thousand dollars. Before the hurricane, the house was valued at more than $100,000... [Now] they can't afford to [raise the house]. So what do you do? You sell. But then you get a fraction. Right now, they're offering $30,000 cash. You had finally built some equity, you had finally built some wealth, and it was wiped out by Harvey. You look at your home, and you're like, I can't fix it, I can't live in it, what do I do? For a lot of people, it's easier to sell and just give up on it, and then you get moved out, someone else buys your home and they build something else there, and they're gonna sell it for a lot of money, because it's a nice area (Moreno 2018).

Income and Livelihoods

Hispanic communities have historically been among the most disadvantaged groups in the United States with regard to earnings and employment benefits (Angel and Angel 2009). This segment of the population is often confined to occupations in sectors that include agriculture, construction, and services in which salaries are low and benefits such as retirement and health-care coverage are rare. Undocumented status exacerbates this trend, as labor structures limit livelihood options and worsen income disparities that constitute a major challenge for economic mobility (Angel and Angel 2009). These issues affect the material and financial resources that vulnerable households have at their disposal to mitigate risks, prepare for disasters, minimize damages and losses, and recover quickly and effectively.

Hurricane Harvey resulted in additional expenses and lost income for Port Houston households. Residents' ability to mitigate flood risk and prepare for the storm was determined by the material and financial resources at their disposal to take precautions to protect their homes from structural damage, as well as the amount of money they were able to spend on extra food, drinking water, medicines, and other basic supplies to weather the storm in their homes. Several Port Houston women stated that government food aid was a key resource for them to be able to provide for their families in the days and weeks after the storm. Furthermore, home repairs and the replacement of damaged belongings were often limited by financial resource availability. Most of the interviewed households reported lost wages due to the inability to reach their workplace during the first few weeks after the storm. While a few of these households were able to rely on their savings to endure this period of reduced income, others had to take measures such as requesting extensions to pay their rent or seeking aid to purchase food for their families. Two women who work as house cleaners expressed that their job stability was negatively impacted by the storm; six months after Hurricane Harvey, their work availability and income remained a fraction of what it had been before the storm. One resident lamented that "new expenses don't wait for you to catch up (Salazar 201840)."

It is worth noting that, while some households were able to weather the storm by relying on their own material and financial resources, all of them were aware of the possibility that the severity of Harvey’s impacts would escalate to a point from which they would struggle to recover. For instance, while Sofia's apartment did not suffer any damages from the storm, she explains that if their apartment or belongings had been damaged, or if her husband had lost more than one week's wages, their recovery would have been more difficult.

Aid

Most of the Port Houston women stated that they were aware of the aid opportunities that were available to them, and many of them made use of government food aid and church donations that were distributed to neighborhood families through NIA. Some confusion surrounded FEMA aid to support home repairs. Some residents received information about the application process but did not understand it, while others applied but did not follow through with the process. Some homeowners were not eligible for FEMA aid because of their insurance coverage, despite struggling to secure insurance payments for their home repairs. Renters were often frustrated by their inability to ensure that damages to their homes would be addressed, despite being assured that their landlords had applied for aid through FEMA to make repairs. One woman stated that she was unaware of the aid options that were available to her, as she did not feel she had needed to make use of them. Although experiences applying for aid were varied, there was a widespread sentiment among Port Houston residents that aid resources should be saved for the families and neighborhoods that had been most severely impacted by the storm.

Health and Environment

The health and environmental safety of Hispanic communities are shaped by historical patterns of disadvantage that result in disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards (Bullard 2000; Mohai et al. 2009; Mohai and Bryant 1992; Peterson and Maldonado 2016). Many portside communities like Port Houston are located within one mile of an industrial facility (City of Houston 2003) and are home to low-income, largely Hispanic communities (Mankad 2017). Emergency shutdowns and subsequent startups of these industrial facilities during Hurricane Harvey caused the release of millions of pounds of excess pollutants into the air and as toxin-laden wastewater (Schlanger 2017). It has remained a struggle for residents to obtain accurate measurements of the industrial emissions that occurred during the storm, due to a lack of transparent reporting and the shutting down of air monitors by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (Ablaza 2018). Portside residents struggle with chronic illnesses and health challenges that many attribute to their exposure to industrial pollutants (Ablaza 2018; UCS and t.e.j.a.s. 201641).

Minority exclusion and institutionalized economic disadvantages have led to a higher risk of socioeconomic insecurity for Hispanic households, which translates into poor health outcomes. Undocumented status can aggravate this insecurity by limiting access to formal employment, increasing workplace risk, and reducing access to benefits such as health insurance, with harmful effects on Hispanic families' health and well-being (Angel and Angel 2009; Dawson 2016; Peterson and Maldonado 2016).

Health challenges played a significant role in some Port Houston residents’ ability to prepare for and recover from Hurricane Harvey. A woman named Angela recounted the “layered disasters” that interacted with her health problems before and after the storm. Angela’s ability to work was hindered by adverse health reactions that she attributes to the chemicals she used in her work cleaning houses. At the same time, she experienced persistent flu-like symptoms that she delayed seeking medical attention for due to a lack of medical insurance. The illness, which she suspects to be pneumonia or bronchitis, grew debilitating and left her bedridden for weeks. During the storm, Angela waded into the waist-deep floodwaters outside her home to help her daughter and her newborn baby back into their house next door. Upon her return, she was electrocuted by a live wire that came into contact with the water. After this accident, she was unable to walk for two weeks and has been unable to work ever since, struggling with muscle stiffness, pain, and the remnants of her illness. Angela expresses feelings of sadness and fear "that so many bad things could happen" to her family. Facing the household's recovery expenses on a reduced income, coupled with health challenges that limit her ability to work, she states that "after something like this, one is simply no longer okay. Everyone suffers more."

Balancing Immediate Needs and Long-Term Development

The need to balance immediate needs with long-term recovery objectives became a priority for community organizations in the weeks and months following Hurricane Harvey.

We need to link our discourse with the problems and concerns that people are facing. People have immediate needs to address right now. Our goal is to engage them in a long-term battle because we don't just want to seek immediate solutions. We want to rebuild and reshape communities with [residents’] inputs, so that they become communities that truly work for [their residents]. Sometimes we knock on people's doors and they expect us to be case managers, or to offer a service. We tell them that we don't offer that service, but that we're fighting for more permanent things, that we want to fight for policies that will protect us in future storms. Just because your house didn't flood this time around, that doesn't mean it won't flood the next time. And that has been a great challenge, but we want to drive home that understanding. And some people say, "yes, I want to be a part of that," but others explain that what they need right now, it's not what we're offering (Ordonez 2018).

In order to tackle this challenge and address immediate vulnerabilities while supporting community resilience to minimize future vulnerabilities, community organizations draw on the networks of relationships that they have built through their continued presence in the community. It is important to highlight the participatory and holistic approach of these community organizations as a key element of their successful neighborhood initiatives. In TOP's case, the organization’s immigration advisor attends neighborhood meetings across all of the organization’s core campaigns, addressing residents’ questions regardless of their direct relevance to the meeting’s focus. This recognition of immigration concerns as all-encompassing challenges that cannot be compartmentalized reveals a deep understanding of and respect for the complexities of communities’ lived experiences of vulnerability. The organizations' approach to community organization emphasizes the need to enable community participation and choice during disaster recovery, illustrating the importance of addressing vulnerabilities and supporting community resilience through a process that is rooted in social justice.

Any solution that the city comes up with has to put people at least in the same place they were before the storm. So if [people] owned [their] house outright, either you pay for the cost of raising the house, so [they] can stay there, or you help people find another suitable home where they're free and clear in the same financial conditions [as they were before]. One of our basic principles is that people should have the right to stay or the right to move, but it should be their choice, it shouldn't be because they're forced out (Moreno 2018).

As the city is rebuilt and reimagined in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, the representatives of community organizations expressed their concern for marginalized neighborhoods that have experienced "historic disinvestment (Moreno 2018)" and highlighted the importance of ensuring that these neighborhoods have a seat at the table. In order to achieve this, Ordonez also pointed to the need to meet transformations in bureaucratic aid and decision-making structures with community empowerment.

The idea is for [communities] to realize that they hold the power. It's what I like the most about my job, being able to empower communities, for them to realize that they can do it, that they are worthy, but that they need to stand up for their rights and to be a part of the process. To understand that they can be a part of the solution. As long as you live in this community, and as long as you live in Houston, this is relevant to you, because we're fighting for everyone, not just for a few individuals (Ordonez 2018).

Conclusion

Natural disasters expose the hierarchies and structures that place marginalized communities in harm's way. This research project explores post-Harvey recovery in the Hispanic community of Port Houston to determine how disaster recovery processes can effectively support resilience and mitigate vulnerabilities of historically disadvantaged communities in the face of natural hazards. The author analyzed the research problem according to a theoretical framework based on anthropological perspectives on vulnerability, resilience, and social justice. The author applied anthropological methods (including participant observation, semi-structured ethnographic interviews, household surveys, and free-listing exercises) to gain insights into how community residents address disaster recovery as a lived experience and how community-based advocacy organizations address disaster recovery needs at the community level.

The key takeaways from the Phase 1 field visit include the importance of social capital and information resources to support disaster preparedness and recovery; social justice and the root causes that shape household vulnerabilities; and the ways in which community advocacy organizations respond to immediate community needs while fostering long-term development to minimize vulnerability and support resilience in the face of future disasters. The first year after a disaster strikes is crucial to preserving well-being and empowering communities to ensure their participation and agency in shaping their recovery. The preliminary results detailed in this report will inform Phase 2 of the research project. An in-depth qualitative data analysis using Maxqda will be conducted after a follow-up field visit to identify broader themes and patterns. It is important to note that, while the information gathered through this small number of interviews cannot be generalized, it does suggest themes for more expansive research.

Research outcomes will be aimed at informing future disaster recovery processes through a more comprehensive understanding of the barriers that exacerbate the vulnerabilities and impede resilience for marginalized communities; approaches that allow community advocacy groups to address vulnerabilities and support resilience in culturally-appropriate ways at the local level; and mechanisms that can improve the effectiveness of organizations addressing vulnerabilities and supporting resilience at larger scales.

Appendix

References

-

Barrios, Roberto E. 2017. “What Does Catastrophe Reveal for Whom? The Anthropology of Crises and Disasters at the Onset of the Anthropocene.” Annual Review of Anthropology, 46: 151-166. ↩

-

Lehtola, Carol J. and Brown, Charles M. 1998. The Disaster Handbook – National Edition. Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. ↩

-

Faas, A.J. and Barrios, Roberto E. 2015. “Applied Anthropology of Risks, Hazards, and Disasters.” Human Organization, 74(4): 287-295. ↩

-

Browne, Katherine E. 2015. Standing in the Need: Culture, Comfort, and Coming Home After Katrina. Austin: University of Texas Press. ↩

-

Wisner, Ben, Piers Blaikie, Terry Cannon and Ian Davis. 2004. “The Challenge of Disasters and Our Approach.” In At Risk: Natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters, 2nd edition, edited by Ben Wisner, Piers Blaikie, Terry Cannon and Ian Davis. pp. 3-48. London; New York: Routledge. ↩

-

Norris, Fran, et al. 2008. “Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities and Strategy for Disaster Readiness.” American Journal of Community Psychology 41: 127-150. ↩

-

Bankston, Carl L. 2010. “Social Justice: Cultural Origins of a Perspective and a Theory.” The Independent Review 5(2): 165-178. ↩

-

Nussbaum, Martha. 2003. “Capabilities as Fundamental Entitlements: Sen and Social Justice.” Feminist Economics 9 (2-3): 33-59. ↩

-

Clingerman, Evelyn. 2011. “Social Justice: A Framework for Culturally Competent Care.” Journal of Transnational Nursing 22(4): 334-341. ↩

-

Bullard, R. D. 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. 3rd edition, Boulder, Colorado: Westview. ↩

-

Mohai, Paul, David Pellow and J. Timmons Roberts. 2009. “Environmental Justice.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 34: 405-430. ↩

-

Mohai, Paul and Bryant, Bunyan. 1992. “Race, poverty, and the environment.” EPA Journal 18(1): 01451189 ↩

-

Peterson, Kristina and Maldonado, Julie. 2016. “When Adaptation is not Enough: Between the ‘Now and Then’ of Community-Led Resettlement.” In Anthropology and Climate Change: From Actions to Transformations, edited by Susan A. Crate and Mark Nuttall. New York and London: Routledge. ↩

-

Angel, Ronald J. and Angel, Jacqueline L. 2009. Hispanic Families at Risk: The New Economy, Work, and the Welfare State. New York: Springer. ↩

-

Dawson, Nigel. 2016. The Undocumented Experience in the United States and Fort Collins, Colorado (Master's portfolio). Fort Collins, Colorado: Department of Anthropology, Colorado State University. ↩

-

Parraga, Marianna and McWilliams, Gary. 2017, September 3. “Funding battle looms as Texas sees Harvey damage at up to $180 billion.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-storm-harvey/funding-battle-looms-as-texas-sees-harvey-damage-at-up-to-180-billion-idUSKCN1BE0TL ↩

-

Hersher, Rebecca. 2017, October 23. “Digging In The Mud To See What Toxic Substances Were Spread By Hurricane Harvey.” National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/10/23/558334923/digging-in-the-mud-to-see-what-toxic-substances-were-spread-by-hurricane-harvey ↩

-

Walsh, Patrick. Patrick Walsh to Whom It May Concern. City of Houston No Zoning Letter. Houston, TX, January 1, 2018. ↩

-

Mankad, Raj. 2017, August 23. “As Houston plots a sustainable path forward, it's leaving this neighborhood behind.” The Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/2017/08/23/houston-plots-sustainable-path-forward-its-leaving-neighborhood-behind/ ↩

-

City of Houston. 2003. Community Health Profiles 1999-2003. Department of Health and Human Services. Houston, Texas: Office of Surveillance and Public Health Preparedness. ↩

-

Whitworth, Kristina W., Elaine Symanski and Ann L. Coker. 2008. “Childhood Lymphohematopoietic Cancer Incidence and Hazardous Air Pollutants in Southeast Texas, 1995-2004.” Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(11): 1576-1580. ↩

-

Schlanger, Zoe. 2017, August 30. “Oil refineries in Hurricane Harvey's path are polluting Latino and low-income neighborhoods.” Quartz. https://qz.com/1066097/hurricane-harvey-oil-refineries-are-polluting-latino-and-low-income-neighborhoods/ ↩

-

Meier, Kathrin (Executive Director, Neighbors In Action), interviewed by Shadi Azadegan at Neighbors In Action Port Houston office, March 2018, Houston, Texas. ↩

-

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 2017. FEMA Flood Map. FEMA Flood Map Service Center. https://msc.fema.gov/portal/search. ↩

-

Google Maps. 2018. Denver Harbor/Port Houston (Houston, TX). https://goo.gl/Lo9Fsk. ↩

-

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). 2015. Food Access Research Atlas. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/. ↩

-

Hauslohner, Abigail. 2017, September 5. “Recovering from Harvey when 'you already live a disaster every day of your life.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/recovering-from-harvey-when-you-already-live-a-disaster-every-day-of-your-life/2017/09/05/40a07e10-9247-11e7-8754-d478688d23b4_story.html?utm_term=.a9fab38cbc6a ↩

-

Sadeka S., M.S. Mohamad, M.I. Hasan Reza, J Manap, and M.S. Kabir Sarkar. 2015. “Social capital and disaster preparedness: conceptual framework and linkage.” E-J Soc Sci Res 3:38–48. ↩

-

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2015. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction. Bangkok: ISDR Asia Partnership (IAP). ↩

-

Dokhi, Mohammad, Tiodora Hadumaon Siagian, Agung Priyo Utomo and Eka Rumanitha. 2017. “Chapter 24: Social Capital and Disaster Preparedness in Indonesia: A Quantitative Assessment Through Binary Logistic Regression.” In Disaster Risk Reduction in Indonesia: Progress, Challenges, and Issues, edited by R. Djalante, M. Garschagen, F. Thomalla and R. Shaw. Switzerland: Springer. ↩

-

Semaan, Bryan, Gloria Mark and Ban Al-Ani. 2012. "The effects of continual disruption: technological resources supporting resilience in regions of conflict." In Crisis Information Management, edited by Christine Hagar. Oxford, Cambridge, and New Delhi: Chandos Publishing. ↩

-

Douglas, M.K., J.U. Pierce, M. Rosenkoetter, L.C. Callister, M. Hattar-Pollara, J. Lauderdale, and D. Pacquiao. 2009. “Standards of practice for culturally competent nursing care: A request for comments.” Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20: 257-269. ↩

-

Powers, M. and Faden, R. 2006. Social justice: The moral foundations of public health and health policy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Moreno, Mary (Communications Director, Texas Organizing Project), interviewed by Shadi Azadegan at Texas Organizing Project Houston Office, March 2018, Houston, Texas. ↩

-

Ordonez, Mitzi (Lead Harvey Community Organizer, Texas Organizing Project), telephone interview by Shadi Azadegan, March 2018. ↩

-

Aguilar, Julian. 2017, September 25. “Appeals court allows more of Texas ‘sanctuary cities’ law to go into effect.” The Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/2017/09/25/appeals-court-allows-more-texas-sanctuary-cities-law-go-effect/ ↩

-

ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union). 2018. Know Your Rights Under SB4. ACLU Texas. https://www.aclutx.org/en/sb4. ↩

-

Ablaza, Leticia (Community Outreach Director, Air Alliance Houston), telephone interview by Shadi Azadegan, March 2018. ↩

-

Hall, Matthew and Greenman, Emily. 2013. “Housing and neighborhood quality among undocumented Mexican and Central American immigrants.” Social Science Research, 42: 1712-1725. ↩

-

Salazar, Lucia (Port Houston resident), interviewed by Shadi Azadegan on March 2018, Port Houston (Houston, Texas). ↩

-

UCS (Union of Concerned Scientists) and t.e.j.a.s. (Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services). 2016. Double Jeopardy in Houston: Acute and Chronic Chemical Exposures Pose Disproportionate Risks for Marginalized Communities. Houston, Texas. ↩

Azadegan, S. (2018). Dimensions of Vulnerability, Resilience, and Social Justice in a Low-Income Hispanic Neighborhood During Disaster Recovery (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 284). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/dimensions-of-vulnerability-resilience-and-social-justice-in-a-low-income-hispanic-neighborhood-during-disaster-recovery