Exploring the Role of Implementing Agencies in Home Buyouts: Process, Equity, and Inclusion in Program Design and Implementation

Abstract

In the wake of recent major hurricanes, the federal government has funded a number of buyout programs that are designed and implemented by local or state agencies. Understanding how these programs are designed and implemented is paramount, given that recent research has suggested that design decisions have considerable impacts on participants. This Quick Response research explored the early phases of the design and implementation of a buyout program in Harris County, Texas, following Hurricane Harvey. To explore this issue, we conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with staff from the local implementing agency and other key stakeholder agencies operating in the area. We found that the implementing agency, which had an ongoing buyout program when Harvey impacted the area, generally kept their existing structure intact. Although Harvey increased buyout demand from residents, the implementing agency suggested that their existing partnerships would continue to facilitate buyouts, as they had in the past. At the city level, Harvey prompted new partnerships and debates about the role of buyouts. In particular, we found that there was considerable tension regarding whether buyouts were a tool for mitigation or for recovery. When asked about the purpose of buyout programs, participants often discussed reducing financial losses for government in future disasters and reducing risks in terms of homes, infrastructure, and the lives of residents and first responders, as well as an opportunity to correct poor land use planning decisions from the past. When asked what residents expected from buyouts, however, participants suggested that residents viewed buyouts as a tool to restore what was lost, a chance to forego a lengthy housing restoration process, and an opportunity to restart in a safer area.

Introduction

Communities in hazard prone areas of the United States increasingly face the prospect of permanent post-disaster or climate-induced relocation, with home buyout programs often used as policy tools to that end. Home buyout programs have potential benefits and risks for both residents in hazard-prone areas and for the government. For residents, buyouts provide an opportunity to relocate to safer areas and may provide financial protection against decreased property values or costly mitigation requirements (David and Mayer 19841). For the government, home buyout programs may protect against costly future losses and prevent costs associated with expensive structural mitigation measures that may ultimately increase community vulnerability to large-scale events (Burby 20062; Phillips 20153). At the same time, studies have indicated that relocation is associated with a wide range of social costs for affected households, including losses in homeownership, social networks, access to healthcare, employment, income, and physical and mental health (Tate et al. 20164; Maly and Ishikawa 20135; Binder and Greer 20166; Blaze and Shwalb 20097; Hori and Schafer 20098; Mortensen, Wilson, and Ho 20099; Riad and Norris 199610; Sanders, Bowie, and Bowie 200311; Weber and Peek 201212).

While researchers have begun to examine the impacts of buyouts on households, there is a significant gap in our understanding of how these programs are designed and implemented. Although such programs are often federally funded, they are frequently implemented at the state, county, or municipal level through local agencies. In a prior study (Greer and Binder 201713), we used policy learning theory to explore how buyout programs iterated over time. Given their 40-year history in the United States, we expected that buyouts would show evidence of improvement over time. Instead, we found that buyouts were designed and implemented independently by local agencies with limited influence from past programs and minimal guidance from federal funding agencies. We also found that micro-level data on the process of buyout design and implementation within local agencies was virtually non-existent. This is a critical knowledge gap given that design decisions have significant implications for communities and households that opt into buyouts (Binder and Greer 2016). Given our lack of understanding about the impacts of buyouts from the perspective of community stakeholders, the increased use of buyouts in recent disasters (FEMA, 201214; Lewis, 201215), and the onset of climate-induced buyouts (Koslov, 201616; Pilkey, Pilkey-Jarvis, & Pilkey, 201617), it is increasingly important that we examine the roles, experiences, practices, and priorities of agencies that implement buyouts.

This study examines questions related to the design and early implementation phases of a home buyout program currently underway in Harris County, Texas. Harris County established a voluntary flood buyout program in 1989, and they have used federal and county funds to purchase approximately 3,300 properties to date in areas designated as high risk for future floods. The county significantly increased the scope of this program after both Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 and the 2015 Memorial Day floods and is expanding the program’s scope again post-Harvey. The buyout program is currently managed by the Harris County Flood Control District (HCFCD).

Research Questions

The home buyout program underway in Harris County presents a unique research opportunity because of the history of buyouts in the area, successive iterations in program design, and the placement of the buyout program in the county’s planning department. Given the pivotal role of local implementing agencies in the buyout process and our limited knowledge of how these agencies operate, our primary research question for this study was:

RQ 1: How do local implementing agencies design and implement home buyout programs?

This question, which previous studies have not directly addressed, is central to our understanding of how policy and practice relate in this area. By examining the mechanics of how individual buyout programs are designed and implemented early in the process and at a micro level, we will gain valuable insights into several key aspects of these programs, including how agencies determine and balance program priorities (e.g., timeliness, development outcomes, and policy directives), select specific program components and parameters, how and to what extent they draw upon past programs as models, and how they perceive the roles of key stakeholders in these processes.

Building on this primary research question, this study addressed three sub-questions that focused on key dimensions of buyout design and implementation.

RQ 1(a): Given the lack of established best practices and the flexibility given to local implementing agencies, what is the process they use when designing buyout programs?

In our earlier work (Greer and Binder 2017), we presented a framework outlining design features reflected by all home buyout programs, including primary funding source, duration, criteria for inclusion, use of financial incentives and disincentives, and degree of government involvement. The framework serves as a tool for conducting in-depth examinations of individual programs. We will document and examine the processes used by the implementing agency in considering program priorities and in making decisions on specific program components, all of which impact program outcomes (Baker et al. 201818; Binder and Greer 2016).

RQ 1(b): To what extent are implementing agencies considering issues of equity in the design and implementation of buyout programs?

In the design and implementation of buyout programs, there are multiple points where issues related to equity may emerge. In design, decisions related to criteria for inclusion, incentives offered, and support provided to participants in the relocation process influence both eligibility and accessibility for affected households. Even if these design decisions are not inherently discriminatory, discriminatory practices may manifest during implementation in communications with affected communities, property appraisal and purchase, and in the relocation options made available to participants. Through this study, we will examine whether and how the implementing agency addresses these concerns.

RQ 1(c): How are community needs and interests considered during design and implementation?

The true test of home buyout programs is arguably their impact on affected households and communities. The limited buyout literature suggests that community engagement in the buyout process improves outcomes (Fraser, Doyle, and Young 200619; Knobloch 200520). As such, we will examine how the implementing agency invites, accommodates, and responds to community engagement in the buyout process. In this study, we will focus on capturing perspectives on community engagement from the implementing agency.

Methods

We gathered data from four sources: in-depth interviews, site visits, program documents, and media reports. We conducted 10 semi-structured interviews with staff from the local implementing agency—HCFCD—and other key stakeholder agencies, including FEMA Region VI, the Texas Water Development Board, Harris County Real Property Division, Houston Public Works, the Houston Floodplain Management Office, and the Houston City Council. We conducted interviews in person, when possible, or by phone. Interviews lasted an average of approximately 45 minutes. The interview guide included questions related to the process of program development and design, including the role of key decision-makers, identification of program priorities, consideration of equity in design and implementation, and the nature of community outreach and involvement. Participants were also asked to reflect on their perceptions of successful outcomes for both government agencies and homeowners and their views of buyouts as a disaster mitigation tool (See Appendix A). An undergraduate researcher transcribed the interviews verbatim for analysis. In addition to the interviews, we gathered information from informal conversations with additional program stakeholders, program documents (including public documents and internal documents provided by interview participants), media reports, and site visits to the areas where buyouts had been implemented or were planned.

In this report, we present preliminary findings based on the qualitative interview data. We analyzed the interview data using grounded theory methodology (Corbin and Strauss 200821), selected due to its applicability to exploratory research. We used an inductive process of open coding to organize data into initial categories, and axial coding to organize categories into higher-level (thematic) concepts.

Preliminary Findings

In the following sections, we present preliminary findings related to our primary research question, which focused on design and implementation processes for the buyout in Harris County. We then present an emergent theme related to the nature of home buyouts as disaster mitigation programs.

The Design and Development of Harris County’s Home Buyout Program

Government Stakeholders

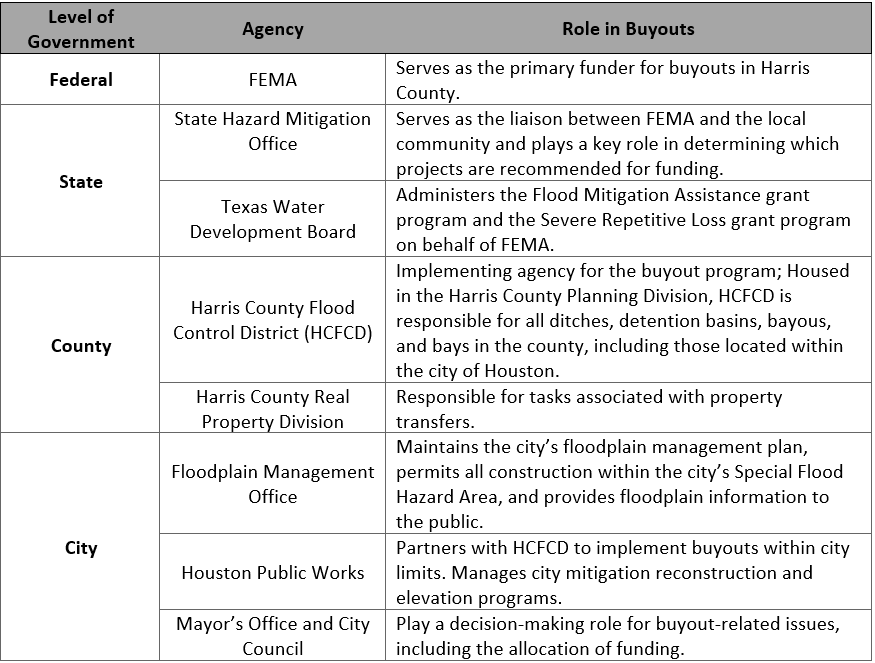

In Harris County, the Harris County Flood Control District serves as the local implementing agency for the buyout program. However, there are many key stakeholders involved in the buyout process from all levels government. See Table 1 for a summary of stakeholders by level of government and a brief description of the roles of each agency.

Table 1. Home buyout stakeholders by level of government

Home Buyouts in Harris County

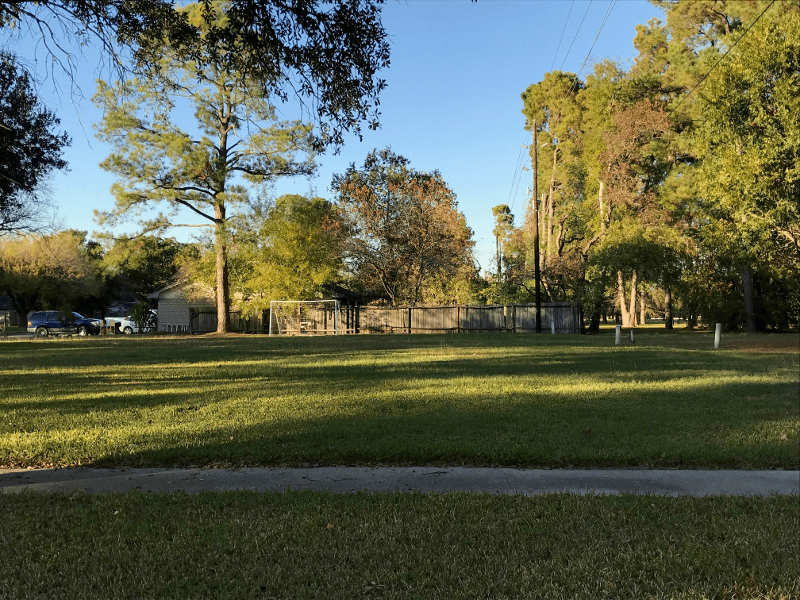

Harris County initiated its home buyout program in 1985. Previously housed at the Harris County Engineering Department, the program was moved to the Planning Department in early 2017, where it is currently administered through the HCFCD. Prior to Harvey, the county had purchased approximately 3300 properties through the buyout program using a mix of federal (FEMA) and county funds. Of these 3300 properties, the majority were purchased after Tropical Storm Allison struck the area in 2001. Participants described buyouts in this period as “scattered,” resulting in “checkerboarding” in areas where most, but not all, homeowners participated in a buyout. Importantly, HCFCD’s jurisdiction includes areas along certain waterways within the Houston city limits, and the city and county have partnered in the past to implement buyouts in the city.

Participants reported that the structure of HCFCD’s buyout program had not significantly changed in many years, despite the fact that there were no real resources available to inform the design of the original program at the time it was created. Through the program, homeowners are eligible for up to $31,000 in relocation assistance beyond the pre-storm fair market value of their homes. This incentive is designed to offset the expected price difference between buyout properties and comparable, lower-risk homes (e.g., homes outside of the floodplain or compliant structures within a floodplain). In addition, the program covers moving and closing costs for buyout participants. Each homeowner is assigned a relocation agent (a county employee) whose job is to guide the homeowner through the buyout process.

Figure 1: An example of "checkerboarding", where a homeowner remains in an otherwise bought-out neighborhood

Home Buyouts after Harvey

When Hurricane Harvey struck the Houston area in late August 2017, it dropped over 40 inches of rain in some areas and flooded an estimated 120,000 structures in Harris County (Di Liberto 201722). Within weeks of the storm, officials from FEMA and Harris County were publicly discussing the need for home buyouts, and the HCFCD was taking steps to prepare for an influx of homeowner requests. HCFCD developed a list of criteria for identifying properties that were appropriate for buyouts, including floodplain depth (with an emphasis on properties that are “hopelessly deep” in the floodplain), infeasibility of structural mitigation measures in the area, and potential future use of purchased properties. All of these criteria pointed to an overarching goal of realizing (and demonstrating) cost savings in future flood events, which in turn reflects HCFCD’s organizational home in the Planning Division.

HCFCD planned to maintain the existing structure of the buyout program post-Harvey, while significantly increasing its scope and capacity. HCFCD’s website includes an online form that homeowners can complete if they are interested in a buyout; these requests increased dramatically after the storm. By November 2017 (three months after the storm), HCFCD had received requests from approximately 3,500 homeowners throughout the county. Of those, approximately 800 met the eligibility criteria discussed above.

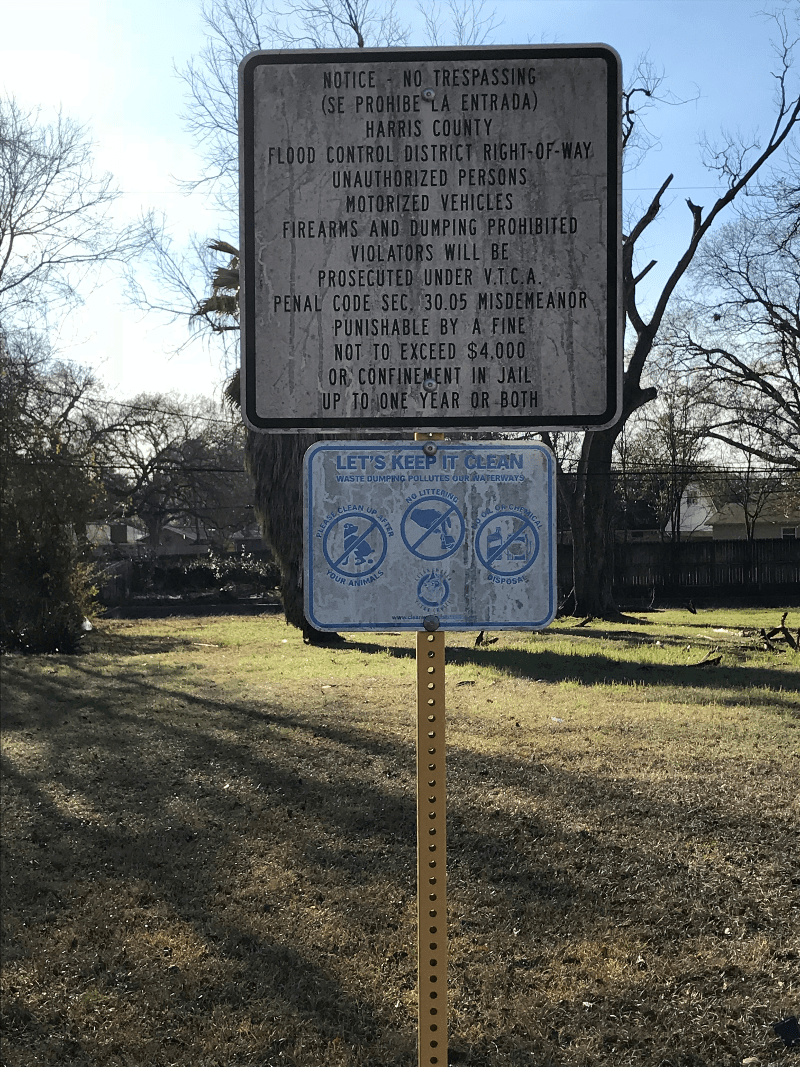

Figure 2: Harris County is tasked with maintaining all properties purchased through buyouts

Discussions about possible buyouts also emerged within the city of Houston soon after the storm. Prior to Harvey, buyouts within the city limits had been funded by the city but were managed and implemented by the county, an arrangement that all participants spoke of positively and agreed would continue. For the city, however, new questions arose post-Harvey, including questions related to the appropriateness of buyouts relative to other mitigation methods and questions about how to best handle buyouts for properties that were within the city limits but beyond the jurisdiction of HCFCD (i.e., not adjacent to a ditch, detention basin, bayou, or bay). Two working groups were established to address these questions. First, an internal working group comprised of representatives from key city agencies was formed, led by the Floodplain Management Office and Houston Public Works. Second, a formal task force made up of representatives from the city and state, as well as industry and academia, was formed to examine broader issues related to mitigation and redevelopment. The internal group addressed buyouts directly and was tasked with making recommendations to city leadership. For buyouts specifically, stakeholders within the city articulated several priorities that differed from those articulated by the county (e.g., losses in the tax base and the need for voter satisfaction).

Challenges in Planning and Implementation

In discussions with key stakeholders, challenges related to funding—and specifically variability in the funding for buyouts—emerged as salient across all levels of government. Participants described multiple challenges related to navigating federal funding sources, requirements, and cycles, all of which were seen as significant hindrances. Federal funding sources operate on a long, slow cycle such that, at the time of Harvey, the county was still waiting to receive federal funds allocated after a 2016 storm event. For Harvey-related funding, it was generally expected that funding would not be available for over a year. These time lags were blamed for several significant challenges, particularly at the county and city levels. For example, while HCFCD was receiving an influx of requests for buyouts and making programmatic decisions related to increasing the scale of the buyout program, they were operating without any knowledge of what funds would be available for buyouts, where the funds would come from, or when they would be available. Beyond the internal challenges this created, the agencies also had to navigate the expectations of homeowners who were facing their own difficult recovery decisions.

“Yeah, that's the biggest thing right now—funding. We need funding because the longer it takes, the more owners are going to repair and spend that flood insurance money if they had flood insurance money, or spend disaster assistance money if they got that. And what I've seen is typically the more time and money an owner puts into a property the less likely they are to continue to volunteer for our program because they say, ‘well, you know, we put $100,000 dollars back into this or $150,000. And it took us six months to do this, and we got it back were we want it. We think that Hurricane Harvey was a freak event, and we're not going to flood again.’ Or they've already sold it to an investor, they let it go back to the bank, or sold it on the open market to someone else who's in that situation.”

While funding is a commonly cited pain point, these challenges illustrate a fundamental tension in the purpose of buyout programs. From the perspective of government agencies and funding sources, buyouts are mitigation programs designed to reduce future hazard losses. Mitigation programs generally have the benefit of operating on longer timelines than recovery programs, and our current systems for funding and implementing buyouts reflect this assumption. Buyouts are nearly always implemented in the recovery phase; however, where changes happen on a compressed timeline, individuals in implementing agencies are taking on responsibilities only loosely associated with their normal roles, and survivors are often experiencing varying levels of housing instability. In the case of Harris County, stakeholders from government agencies recognized that homeowners were hoping for the buyout program to move quickly and aid in their recovery. They were convinced, however, that this was not a realistic expectation.

“They want it to happen right away. They are ready—they’re ready to move on. They’re ready to start—I mean they just—I mean in most cases it’s totally traumatic for them. They’re ready to get back to normal, and they want to get there as quickly as possible. And we have to explain to homeowners that’s just not the nature of the grant program. It’s not something that happens instantaneously.”

The tension between whether buyouts function as mitigation or recovery programs was most evident at the local level, where the implementing agency interacts directly with affected households and communities. While the language used by participants at the city and county levels favored the view of buyouts as mitigation programs, they were regularly challenged by perceptions and realities of households in the midst of recovery.

“I think people thought that FEMA was going to come and write them a check the next week, and… our programs do not run like that… there’s an application process, and it’s state administered, and I have to have funding available. I mean, there’s just all these things in between the bureaucracy of the program, but I think that’s what—I think people, I think the first thought is, ‘FEMA buys houses.’ Well no, FEMA doesn’t buy houses, right? Local communities buy houses using federal funds, but I think that’s what the main—if I asked people in general what they thought, it’s, ‘FEMA’s going to buy me out and they’re slow, but I want out now or I wanted out three months ago. I wanted out the day after.’”

“The only negative side to that is that you have, maybe, unrealistic expectations of the public. ‘Well I signed up for it, so where is my buyout? I signed up, and I haven’t gotten an offer for my house yet,’ and that may not be the most realistic view of how this will proceed.”

In the following section, we explore this emergent finding in more detail.

Emergent Finding: Tension in Home Buyout Programs—Recovery or Mitigation Efforts?

When describing the purpose of the buyout program, our participants often noted that the program was primarily a mitigation measure. More specifically, they saw such programs as a way to limit future losses and reduce exposure, and as an opportunity to improve land use or complete existing projects. When asked about homeowners’ perspectives and expectations, however, they typically described the purpose of the program as aligning closer to traditional definitions of recovery. They cautioned, however, that this measure often failed to serve as an effective tool for recovery given the lengthy period of time between the disaster, the acquisition of funding, and the eventual purchase of properties.

Buyouts as a Mitigation Measure

Participants often described buyouts as one mitigation measure among many, highlighting the importance of selecting the most appropriate mitigation measure for each area or property. They emphasized the importance of assessing long-term mitigation needs, taking a wide view of the needs of a given area, and then determining whether a buyout was the best tool to meet those needs.

“There might be some homes that have severe repetitive losses, that have tons and tons of claims that frequently flood, but we don’t consider it for a buyout because maybe a bigger outfall pipe needs to be put in, or maybe if that house was just built a little bit higher it wouldn't be flooding. And to go in and, um, turn a whole—you know, a neighborhood into an open field forever just because the homes were built one foot too low is hard.”

In many cases, buyouts were not the preferred method of mitigation. Rather, participants suggested buyouts were the best option only in cases where other mitigation measures were not viable or had failed.

“Um, my understanding is, you know, back in the mid-1980s, they had these catastrophic flood events that were on Cypress Creek that really kind of wiped out a couple of areas, and um, and they decided at that time that it really wasn't, there wasn't a good project that could reduce flooding, and the fact was the homes were just built in the wrong place. Which is really the basis of our program still today it, there's a lot of areas that were built that should have never been developed because we didn't have any flood regulations until the mid-1980s. Also, because that's when we got our floodplain maps and flood insurance rate maps, the first detailed flood insurance studies.”

When buyouts were determined to be the most appropriate choice, the reasons given by participants reflected priorities typically associated with mitigation. Among these, financial implications were the most commonly mentioned reason for selecting a buyout, with participants at all levels of government referencing some form of cost-benefit analysis associated with taking the properties out of flood-prone areas and eliminating repeat losses.

“The purpose is to relocate residents that live in flood prone areas. And, because they’re mostly insured, and FEMA keeps having to pay those flood insurance claims over and over. And I just think they have to realize that it’s a lot cheaper just to buy out the properties, demolish the homes, and then there will never be another claim on that property again. So, it gets everybody to higher ground and saves FEMA money.”

“You know, being financial um, what's the term? Cost-effective, that's what they use. That's the talking point. It has to be cost-effective, and when it's cheaper to buy out the property than it is to do repairs… it makes sense.”

“So, if we can buy, that $700 or $800 million that I talked about, you know, NFIP [the National Flood Insurance Program] is going to save money because we are actually taking those repetitive flood properties, because that's what they are.”

At the county level, this priority was institutionalized through routine assessments of avoided losses after major storms. These analyses were used to quantify losses that were avoided through previous property acquisitions and cited as a justification for future buyout applications.

Beyond cost savings, participants suggested several additional purposes for buyouts. These included reducing future exposure, removing building stock from areas in which they likely would not allow construction today, and expanding existing mitigation projects, such as greenways or retention ponds.

“The one that I think is the most meaningful is when a community looks and says, ‘we really should not have building stock in this location’…you know, I always think that is the best approach. Acquisition is our one project that we fund in our hazard mitigation grant program that doesn’t have any residual risk, so it is a complete elimination of risk…”

“The purpose? Um, I mean it's really to take properties that should have never been developed and turn it back to its natural function as a floodplain. Um, yeah, it's, you know, there were no regulations on building in a floodplain until the mid-1980s so, and I forget the numbers, like 2 million people or more that had already moved here at that time. So, a lot of areas were developed that shouldn't have been developed, and we're just correcting that problem.”

Interestingly, future land use played a prominent role in participants’ descriptions of successful buyout programs. This included concerns about the long-term maintenance of acquired properties and hopes for community benefits related to the reuse of bought out land.

“Um, one that’s looking at everything holistically. You know the conversation we have with communities is, ‘once you acquire the property, what are you doing to do with the property?’ Um, you know, these are options that other communities have done, you know, whether they’ve done soccer fields or detention pounds or a park, or in some cases, they’ll lease it to the neighboring property you know, so they have a bigger yard.”

Buyouts as a Tool for Recovery

When asked about the purpose of the buyout, interviewees would occasionally mention that a buyout could be used as a tool to jumpstart recovery efforts for affected households. More often, however, the idea of buyouts as recovery was mentioned when asking participants about what households expected from buyout efforts. Participants suggested that homeowners often, reasonably, wanted to resume normal routines, including returning to some semblance of housing stability. Interviewees acknowledged that homeowners saw the buyout program as a potential means to that end, though they countered that buyouts, by design, only worked to reduce future flood losses to a community.

“They expect it to be an emergency relief program. They expect it to be, ‘we flooded, we flooded bad, get me out of here,’ and that's not what it is. Everybody wants to be bought out yesterday so that they can move on with their lives. Sadly, that's not what this program is, and I don't think there is any way it could be.”

“Yeah, it's not an immediate relief program. It's for—like I said, its future flood reduction measures and what we're trying to do is buy out homes where we can do some measures by just simply removing the home and really reduce flood risk, but in the future, other projects will happen that will reduce the flood risk for even more people. So, it's a stepwise—we’re reducing flooding not because, not for the house that we're buying, but for the surrounding area by doing the buyout program. That it's, that the program isn't buying a house—that’s not the goal of the program. While that's what you see, the actual goal of the program is to reduce flooding for the larger area, which is the mandate of Harris County Flood Control District.”

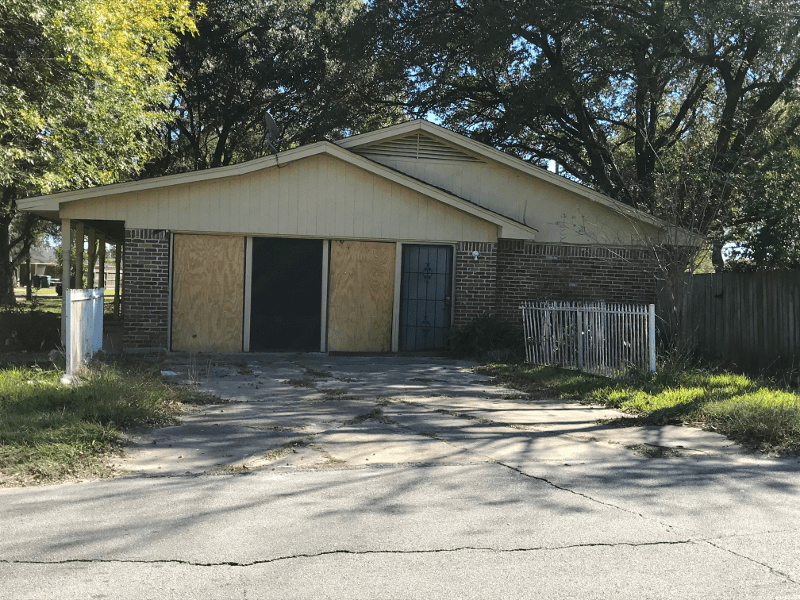

Figure 3: Housing damage is still evident three months after Harvey

The Implications of this Discrepancy

Taken together, the data suggest that a lack of timely funding and competing priorities inhibit the implementation of buyout programs, creating significant challenges for both government agencies and homeowners. While funding for buyouts is not guaranteed, buyout program administrators want property owners to wait for buyout offers so they can mitigate without leaving a checkerboard of existing properties, where homeowners want certainty regarding the future of their housing and permanence in their post-disaster housing.

“One of the more frustrating things for the, because the process takes so long, it's hard to say—you know tell people we may or may not have money six months from now. So, it's just a matter of keeping them updated, and once they get the money, it goes quick.”

From the perspective of local implementing agencies, the primary consequence of this tension was attrition. Many homeowners expressed interest in being bought out in the wake a Harvey, including owners of over 800 properties that met the aforementioned HCFCD criteria. Homeowners, however, could not put their recovery on hold while they waited for appropriate funding to come through. Participants were concerned that, as time passed, these homeowners would use available funding (including insurance and FEMA Individual Assistance grants) to repair and rebuild their homes, or that they would sell their homes to private investors who would redevelop and repopulate the properties. In either case, the mitigative potential of the buyout program would be significantly compromised.

“Additionally, timing being so extended, there are some folks who could and would accept a buyout on the day after the flood if they are looking at combining proceeds from various streams that are available to them, you know? Before they take the SBA loan, before they, you know, before they spend their insurance claim on repairs, before they spend their personal resources on temporary living, you know? All those streams of resources that people are expending, if you can get them before then, they can afford to take the buyout. But if you got somebody who’s upside down on their mortgage and also has an SBA loan and has already spent all their personal resources and already spent their, you know, their disaster relief check or insurance check, they’re a tough customer. They can’t afford to take the buyout, and the reason they can’t afford to take it is because we’re too slow. We recognize that that’s such a barrier, and it’s really a shame because it’s all a waste of resources—both their personal resources and federal dollars, local dollars, and it makes a program less successful…”

“I've had conversations with a lot of the folks who have volunteered [to participate in the buyout program], the 840, and a lot of them are, at the same time that they volunteer, they put their home on the open market, and really the first decent offer they get a lot of times they go with that. A lot of times investors are trying to come in and purchase those properties that are damaged and then repair them and put someone else in them who may or may not be aware of the flooding problem. Sometimes they're walking away from the home all together, letting it go back to the mortgage company and then of course the mortgage company is going to put someone back into it… If we had that funding and we knew that we could move, we still wouldn’t have 100 percent participation, but I'm sure we'd have a lot more volunteers that we would be able to assist and, you know, help them move to higher ground and convert that property back to its natural function.”

Applications and Future Research

In the United States, the federal government has funded a number of buyout programs in the wake of recent major hurricanes. Although these programs are federally funded, they are locally implemented, and the agencies responsible for designing and carrying out these programs are given considerable latitude when building these programs (Greer and Binder 2017). Understanding how these programs are designed and implemented is paramount given that recent research has suggested that these design decisions have considerable impacts on how survivors experience these programs (Binder and Greer 2016). Given the magnitude of Hurricane Harvey and the history of land use decisions and buyouts in Harris County, this served as an excellent setting to learn more about buyout programs, particularly with a focus on how programs evolve over time.

Through this Quick Response research, we wanted to explore how HCFCD designed and implemented their home buyout program in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. In particular, we wanted to understand how they considered issues of equity and community needs and interests when shaping the program. What we found, in many ways, was that HCFCD felt that the system they had in place before Harvey for selecting properties and ushering them through the buyout process would be adequate for Harvey as well. While they acknowledged that interest and demand is much higher than in the past, they suggested that the same key stakeholders would be involved, and their existing partnerships would continue to operate as they had in the past. Although they have always wanted to acquire a larger number of properties than funds allowed, they saw this as an accelerating issue in the wake of Harvey, with a new onslaught of homeowners requesting buyouts. At the city level, Harvey prompted the development of new internal and external partnerships and sparked discussions about the role of buyouts that are ongoing.

As an emergent finding from this research, we found that there was considerable tension regarding whether buyouts were a tool for mitigation or a tool for recovery. When asked about the purpose of buyout programs, participants often discussed reducing financial losses for government in future disasters; reducing risks in terms of homes, infrastructure, and the lives of residents and first responders; and as an opportunity to correct poor land use planning in the past. Essentially, they saw buyouts as another tool in their mitigation toolbox. When asked about what residents expected from buyouts, however, participants suggested that residents were viewing buyouts as a tool to restore what was lost, and a chance to forego a lengthy housing restoration process and restart in a safer area. This was stymied, however, by design. These programs require considerable federal funding, and these funds often arrive years after an event, requiring residents to wait to restart their lives after a disaster pending a possible buyout. For this reason, most participants suggested that while homeowners often viewed buyouts as a recovery measure, they could really only function—as current policy dictates—as a long-term nonstructural mitigation measure.

This research opens several avenues for future research. First, as evidenced by previous buyouts, these programs evolve over time (Greer and Binder 2017). Often, changes to these programs are poorly documented, so there is considerable value in a longitudinal study where researchers embed themselves with buyout administrators for the life of a buyout program, which ranges from a few years to a few decades. Second, while we focused on the perspective of agencies that implement buyouts, there are survivors who are advocating for their homes to be purchased and who have their own perspectives on buyout design, communication, and timelines. Future research should continue to explore this issue from the perspective of the affected population. Likewise, there are those requesting buyouts who likely will not be included, whether because of a lack of funds or because they fail to meet the selection criteria. The fate of this population in the long-term represents a gap in our understanding. Lastly, we suggest that future researchers continue to compare buyout programs to build systematic knowledge regarding design, implementation, and effects on participating households.

References

-

David, Elizabeth, and Judith Mayer. 1984. “Comparing Costs of Alternative Flood Hazard Mitigation Plans: The Case of Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin.” Journal of the American Planning Association 50 (1): 22–35. ↩

-

Burby, Raymond. 2006. “Hurricane Katrina and the Paradoxes of Government Disaster Policy: Bringing about Wise Governmental Decisions for Hazardous Areas.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604: 171–91. doi:10.1177/0002716205284676. ↩

-

Phillips, Brenda D. 2015. Disaster Recovery. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ↩

-

Tate, Eric, Aaron Strong, Travis Kraus, and Haoyi Xiong. 2016. “Flood Recovery and Property Acquisition in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.” Natural Hazards 80 (3). Springer Netherlands: 2055–79. doi:10.1007/s11069-015-2060-8. ↩

-

Maly, Elizabeth, and Eiko Ishikawa. 2013. “Land Acquisition and Buyouts as Disaster Mitigation after Hurricane Sandy in the United States.” Proceedings of International Symposium on City Planning, 1–18. ↩

-

Binder, Sherri Brokopp, and Alex Greer. 2016. “The Devil Is in the Details: Linking Home Buyout Policy, Practice, and Experience after Hurricane Sandy.” Politics and Governance 4 (4): 97. doi:10.17645/pag.v4i4.738. ↩

-

Blaze, John T., and David W. Shwalb. 2009. “Resource Loss and Relocation: A Follow-up Study of Adolescents Two Years after Hurricane Katrina.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 1 (4): 312–22. doi:10.1037/a0017834. ↩

-

Hori, Makiko, and Mark J. Schafer. 2009. “Social Costs of Displacement in Louisiana after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita.” Population and Environment 31 (1–3): 64–86. doi:10.1007/s11111-009-0094-0. ↩

-

Mortensen, Karoline, Rick K Wilson, and Vivian Ho. 2009. “Physical and Mental Health Status of Hurricane Katrina Evacuees in Houston in 2005 and 2006.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 20 (2): 524–38. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0130. ↩

-

Riad, Jasmin K., and Fran H. Norris. 1996. “The Influence of Relocation on the Environmental, Social, and Psychological Stress Experienced by Disaster Victims.” Environment and Behavior 28 (2): 163–82. ↩

-

Sanders, Sara, Stan L Bowie, and Yvonne Dias Bowie. 2003. “Chapter 2 Lessons Learned on Forced Relocation of Older Adults.” Journal of Gerontological Social Work 40 (4): 23–35. ↩

-

Weber, Lynn, and Lori Peek. 2012. Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ↩

-

Greer, Alex, and Sherri Brokopp Binder. 2017. “A Historical Assessment of Home Buyout Policy : Are We Learning or Just Failing ?” Housing Policy Debate 27 (3). Routledge: 372–92. doi:10.1080/10511482.2016.1245209. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2012. “Hazard Mitigation Assistance - Property Aquisition (Buyouts).” http://www.fema.gov/application-development-process/hazard-mitigation-assistance-property-acquisition-buyouts. ↩

-

Lewis, David A. 2012. “The Relocation of Development from Coastal Hazards through Publicly Funded Acquisition Programs: Examples and Lessons from the Gulf Coast.” Sea Grant Law and Policy Journal 5 (1): 98–139. http://nsglc.olemiss.edu/. ↩

-

Koslov, L. 2016. “The Case for Retreat.” Public Culture 28 (2): 359–87. doi:10.1215/08992363-3427487. ↩

-

Pilkey, OH, L Pilkey-Jarvis, and K Pilkey. 2016. Retreat from a Rising Sea: Hard Choices in an Age of Climate Change. New York: Columbia University Press. ↩

-

Baker, Charlene K, Sherri Brokopp Binder, Alex Greer, Paige Weir, and Kalani Gates. 2018. “Integrating Community Concerns and Recommendations into Home Buyout and Relocation Policy.” Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy. doi:10.1002/rhc3.12144. ↩

-

Fraser, James C, M.W. Doyle, and H. Young. 2006. “Creating Effective Flood Mitigation Policies.” Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 87 (27): 265–70. ↩

-

Knobloch, Dennis M. 2005. “Moving a Community in the Aftermath of the Great 1993 Midwest Flood.” Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education 130 (1): 41–45. doi:10.1111/j.1936-704X.2005.mp130001008.x. ↩

-

Corbin, J.W., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. ↩

-

Di Liberto, Tom. 2017. “Reviewing Hurricane Harvey’s Catastrophic Rain and Flooding.” Climate.Gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/reviewing-hurricane-harveys-catastrophic-rain-and-flooding. ↩

Brokopp Binder, S. & Greer, A. (2018). Exploring the Role of Implementing Agencies in Home Buyouts: Process, Equity, and Inclusion in Program Design and Implementation (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 281). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/exploring-the-role-of-implementing-agencies-in-home-buyouts-process-equity-and-inclusion-in-program-design-and-implementation