Gathering Places During the Short-Term Recovery Following Hurricane Harvey

Publication Date: 2018

Author Mary Nelan, of University of North Texas, visits a donation center at a Rockport, Texas, church. ©Ronald Schumann, 2017.

Author Mary Nelan, of University of North Texas, visits a donation center at a Rockport, Texas, church. ©Ronald Schumann, 2017.

Abstract

This report introduces the concept of gathering places in disaster recovery and describes gathering places active in southern Texas one month after Hurricane Harvey.

Gathering places are conceptualized as nodes of internal convergence, where impacted residents and aid workers come together to access information about recovery resources and seek support from others. These places can be part of the formal disaster assistance system (e.g., Federal Emergency Management Agency Disaster Recovery Centers and Red Cross shelters) or they can emerge informally (e.g., diners, salons, bars, and neighborhood cookouts). Gathering places are sites where social capital is developed and place attachment is actualized. Over the course of recovery, we would expect the nature and function of gathering places to evolve, according to the changing needs of residents and aid workers as well as the shifting service landscape.

While researchers have extensively studied housing recovery, business recovery, and aid distribution, fewer systematic studies have focused on ephemeral social geographies essential to the recovery process. Using brief, semi-structured interviews with residents and aid workers, this study identifies gathering places that emerged in Harvey’s aftermath, qualifies what functions they served, investigates the nature of interactions occurring there, and explores aspects that might limit their effectiveness.

Introduction

Damage in Rockport, Texas, observed by the authors during a windshield survey on September 21. ©Ronald Schumann, 2017.

Damage in Rockport, Texas, observed by the authors during a windshield survey on September 21. ©Ronald Schumann, 2017.

In the aftermath of disaster, extensive damage to infrastructure, businesses, and established communications channels can lead to the emergence of new networks for procuring supplies, financial aid, information, and psychological support (Kaniasty and Norris 19951; Van Wassenhove 20062). Survivors might initially congregate at formal locations established for disaster relief. These locations could include emergency distribution centers offering food, water, and household items; churches that serve hot meals and organize volunteers to assist with cleanup; and Federal Emergency Management Agency Disaster Recovery Centers, where residents can register for financial aid and get referrals to community resources. These centralized nodes, or gathering places, function as sites of internal and external convergence (Fritz and Mathewson 19573) for community members and non-local aid workers.

Unfortunately, short-lived media coverage and the brief national attention span can limit the sustained availability of recovery resources in disaster-affected areas (Downs 1972). Thus, these formal gathering places often vanish long before community businesses and services are completely recovered (Haas et al. 19774), leaving impacted residents and aid workers to navigate an unfamiliar, shifting, and service-poor landscape to meet their daily needs. As short-term recovery transitions to long-term recovery, not only does the service landscape evolve (Zhang 20095; Phillips 20136), but so do the needs (in terms of information, physical support, and emotional support) of residents and aid workers. We contend that this evolution, combined with the initial shortage of facilities that meet the needs of residents and aid workers simultaneously, presents potential for improvising routines, developing new social capital, and creating positive and negative interactions among and between the populations.

This study focuses on this process of community evolution during recovery, examining it through the lens of gathering places. We conceptualize gathering places as nodes of internal convergence where community members and aid workers come together to access recovery resource information and seek support from others. These places, which can be either formal or informal, are also sites where social capital is formed. We expect that the nature and function of gathering places will evolve throughout the recovery process according to the changing needs of affected residents and aid workers, as well as the shifting service landscape. This research investigates the geographic and temporal dimensions of social capital formation and convergence behavior, thereby uniting the hazards geography and disaster sociology traditions. The study area is comprised of three South Texas coastal communities impacted by Hurricane Harvey: Bayside, in Refugio County, Port Aransas, and the Rockport/Fulton/Aransas Pass area located in Aransas County.

Hurricane Harvey’s Impact in South Texas

On August 25, 2017, Hurricane Harvey made landfall near Rockport, Texas, as a Category 4 (sustained winds of 130-155 mph) storm (FEMA 20177; NOAA 20178). Coastal communities were flooded by storm surge measuring nearly six feet (Crow 20179). In Aransas County, 13,000 people registered for FEMA assistance (Jervis 201710). In Port Aransas, approximately 650 individuals were treated for injuries resulting from the storm (Bradshaw 2017 11) and 90 percent of businesses were damaged (Chang 201712). Hurricane Harvey resulted in the death of 75 people—the majority of the were in the Houston area. One person in Aransas County was killed by the storm. There were no deaths in Refugio County (George et al. 201713). As of July 2018, the total monetary cost of the storm was estimated at $125 billion (NOAA Office for Coastal Management 201814).

While Houston has received significant national media coverage due to widespread flooding, the South Texas Coast where Harvey made landfall remains relatively unnoticed. The three selected coastal communities in the study were all impacted by the northeastern eyewall of the storm where the strongest winds and storm surge were located (NWS 201715). Port Aransas sits on a barrier island bordering the Gulf of Mexico. The town experienced Harvey’s maximum measured wind gust (132 mph) and received extensive damage from both wind and storm surge (NWS 2017). Across Aransas Bay, the suburban towns of Rockport, Fulton, and Aransas Pass blend together along State Highway 35. This area received the storm’s worst wind damage: many buildings suffered collapsed walls, while roofs and upper stories of homes were sheared off (NWS 2017). Bayside, the smallest of the communities, sits farthest from the coast and is separated from the Rockport/Fulton/Aransas Pass area by Copano Bay. While Harvey produced a local rainfall maximum just north of Copano Bay (NWS 2017), a windshield survey and local interviews in Bayside confirmed that a combination of extreme wind and wind-driven rain pushed homes off their foundations, unsheathed roofs, and caused widespread interior mold damage.

Place Attachment and Social Capital

The current study of gathering places draws from theory on social capital and place attachment, but we focus on place attachment as it has received much less attention in disaster literature. Social capital refers to the value derived from shared norms of trust and reciprocity that exist within one’s interpersonal networks (Ritchie and Gill 200716). Numerous studies have highlighted the pivotal role of social capital in fostering a successful recovery from disaster and in building community resilience to future threats (Aldrich 201217; NRC 201218; Aldrich and Meyer 201519). Place attachment refers to a set of positively experienced behavioral, cognitive, emotional bonds that individuals and groups form with their socio-physical environment (Brown and Perkins 199220; Scannell and Gifford 201021). There is a degree of overlap in the concepts, which is why researchers sometimes conflate place attachment with bonding social capital. The notion of sense of community is, after all, implicit to social capital, and community identity is formed by repeated social interactions in a distinctive place (Milligan 198822).

Researchers disagree over how many components of place attachment exist, but this study on gathering places touches on at least three: place dependence, place identity, and place bonding. Place dependence refers to the of ability of a location to meet the functional needs of an individual, such as the availability of adequate housing, employment, transportation, commercial services, and public services (Pretty, Chipuer, and Bramston 200323). Place identity refers to individual notions of self, which are endowed by the symbolic elements of a community (Cuba and Hummons 1993 24). Finally, place bonding is the emotional connection fostered with a natural, physical, and social environment (Scannell and Gifford 2010).

Gathering places can simultaneously serve one or all of these place attachment functions. For instance, before a disaster, residents would have relied upon traditional locations (e.g. hardware stores, diners, grocery stores, places of worship, bars/restaurants, salons, etc.) to access information from neighbors and complete routine tasks (i.e., place dependence). These commonplace locations can also contain memories that make up personal identities and provide necessary spaces for neighboring and altruistic activities that solidify trust and care about a community (i.e., place identity, place bonding). Disaster studies have long documented the tendency of places to recover in ways that restore place dependence (Haas et al. 1977; Franciviglia 197825) as well as place identity and place bonding, which often occur in tandem (Erikson 197626; Fothergill 200427; Chamlee-Wright and Storr 200928). In the aftermath of disaster, gathering places traditionally used by residents may not be operational or accessible. Thus, a large degree of improvisation in routine may occur as residents seek out new community networks and locations that meet their place-based needs.

Convergence

Three types of convergence emerge following disaster events: personal, material, and informational (Fritz and Mathewson 1957). This research focuses primarily on the first type. Personal convergence includes any individuals that move into the disaster affected area, such as volunteers, aid workers, researchers, journalists, residents of surrounding communities, and people returning to their own homes during the recovery. There are a multitude of motivations for individuals to come into the impacted area, one being the urge to help those negatively affected by the disaster. In addition, returnees may be motivated by their own desires to return home and back to the routines that they had before the event (Kendra and Wachtendorf 200329).

While their very entrance into the disaster area exemplifies convergence behavior, there are also places of internal convergence within the disaster zone where people congregate (Fritz and Mathewson 1957). These places can have a variety of functions such as provision of mass care, donation and food distribution, and information distribution (e.g., FEMA Disaster Recovery Centers). It is at these locations that aid workers (both paid employees and volunteers) interact and gather together with residents of the impacted area. Given the limited number of gathering places in the community, we anticipated that aid workers and residents would occupy the same spaces, prompting interactions between groups and individuals who might not normally encounter each other.

This research seeks to understand where and how these groups interact, whether residents and aid workers find the support and recovery-related resources they need at these locations, and, if not, what limits gathering place effectiveness. The following sections describe the research questions, methods, and findings based on interview data collected on gathering places one month after Hurricane Harvey made landfall on the Texas coast.

Research Questions

This study addresses the following research questions:

(1) What formal and informal gathering places emerge in the aftermath of a disaster?

(a) Do these places differ for aid workers and for residents?

(2) Where do aid workers and residents interact?

(a) What is the nature of these interactions?

(3) What aspects limit the ability of gathering places to meet the needs of residents and aid workers?

Methodology

To answer these research questions, we traveled to the Coastal Bend region of South Texas to investigate the locations and functions of formal and informal gathering places. Previous research indicates that population size is an important factor in shaping the nature of community bonding and place attachment (Hummon 199230), therefore we selected three Texas coastal communities of differing sizes for data collection: Bayside, with a population of 325, Port Aransas, population 3,480, and Rockport, Aransas Pass, and Fulton area with a combined population of 19,129 (given their proximity and geographic contiguity we addressed the three town as one area) (U.S. Census Bureau, 201031). We varied the size of areas sampled to see if there were differences in how gathering places evolve given different populations sizes. We intentionally avoided larger urban areas, such as Houston, since gathering places there could have been too numerous or too dispersed to study effectively. In addition to size, the study communities differed in their sense of place and degree of interdependence from nearby communities. Whereas Port Aransas functions as a relatively self-contained resort town, we found that residents of Rockport, Fulton, and Aransas Pass traveled frequently between the areas for work, shopping, and leisure activities. Bayside contains only about half a dozen non-residential structures, including a city hall/community center, gas station, small café, and three churches. We learned from an interview that residents drive about 17 miles to either Refugio or Woodsboro to access schools, stores, and most services.

We conducted interviews in these communities from Friday, September 22 to Sunday, September 24, 2017, four weeks after Hurricane Harvey made landfall. These dates were chosen because residents would have begun the short-term recovery effort in some areas and would be seeking to reconnect with neighbors, friends, and others in their community. In addition, aid workers would have settled into the recovery effort and would be in the process of developing their own gathering places. We anticipated that many of the gathering places that were active four weeks after the hurricane would be ephemeral. In addition, with the expectation that gathering places will evolve and change as the recovery effort continued, it was necessary to collect baseline data soon after the event so that future cross comparisons can be made.

Sampling Techniques

Interviewees were recruited through a snowball sample of residents and aid workers. We first began recruitment at formal community gathering places, specifically targeting the FEMA Disaster Recovery Centers (DRCs) in Ingleside and Port Aransas that serviced the study communities. After obtaining permission from the manager in charge of each DRC, the authors interviewed individuals waiting in line or leaving at each facility. Through these interviews, we identified other locations where residents were seeking resources, information, or emotional support. We then traveled to those locations to conduct further interviews. In addition, we sought aid workers at formal bases of operation. Volunteer checkpoints at the Aransas Pass Library and the Port Aransas Community Center (where the Port Aransas DRC was located) were starting points for aid worker snowball samples.

Interviews

We conducted semi-structured, anonymous interviews with residents of the three affected communities and with aid workers in those communities. Each interview took five to ten minutes, and we did not collect identifying information from participants. Participants gave verbal consent to take part in the research, and upon the conclusion of the interview, they were provided with a handout outlining our research objectives and contact information should they have further questions.

Two distinct interview guides were created—one tailored to residents and the other to aid workers. Interviews with residents of the affected areas focused on locations in the community where they gathered to obtain information, resources, and emotional support; and how successful they felt they were at finding needed resources. Additional context questions asked about resident housing tenure and displacement status (including displacement location), displacement of neighbors, and the presence of household members from vulnerable groups.

Author Mary Nelan interviews aid workers at an emergent camp in Port Aransas, Texas. ©Ronald Schumann, 2017.

Author Mary Nelan interviews aid workers at an emergent camp in Port Aransas, Texas. ©Ronald Schumann, 2017.

Interviews with aid workers focused on locations where they interacted with residents and other aid workers and what tasks they were performing in these locations. Additionally, aid workers were asked about their organizational affiliation, previous experience in other disasters, the length of their stay in the vicinity following Harvey, and how long they planned to continue serving in the area. Each interview guide was formatted as a standardized, single-page form, which enabled the researchers to collect interview data using pen and pad in the field.

A total of 111 interviews were conducted with 125 individuals. In all, 81 residents took part in 76 interviews and 44 aid workers took part in 35 interviews. Every effort was made to interview one participant at a time, but in some cases this was not possible due to interpersonal dynamics at the data collection site. Elderly residents accompanied by adult children, spouses living in the same household, neighbors seeking aid together, and small teams of affiliated aid workers are examples of these sporadic cases. Five resident interviews included multiple individuals, but only one of these interviews included members of different households. Five aid worker interviews were conducted with multiple individuals, but in all of these interviews, the aid workers were affiliated with the same organization. Personal characteristics were logged for the dominant speaker in each of these multi-person interviews. In describing sample characteristics below, we use a sample size of 111 based on the number of unique interviews conducted. Characteristics for aid workers further break down the data by individual aid worker, as interviews with multiple workers sometimes contained more than two individuals.

Interviewee Characteristics

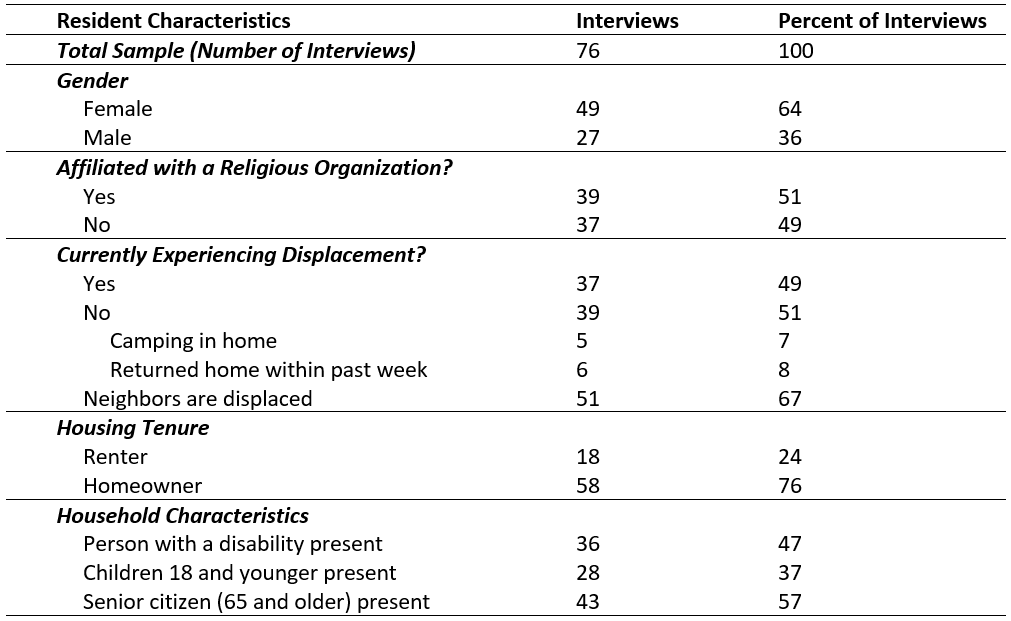

Table 1 highlights resident characteristics. Approximately two-thirds of the resident sample were female. Only half of residents indicated that they were members of a church or religious body. Most residents in the sample lived in either Rockport (26 percent), Aransas Pass (24 percent), or Port Aransas (21 percent). This is unsurprising, as these cities are the most populous and densely settled in the impacted region. Residents from Corpus Christi and neighboring small towns (e.g., Ingleside, Portland, Bayside, and Fulton) are also represented in the sample. All interviewees reported residing in either Aransas, Nueces, San Patricio, or Refugio Counties. At the time of data collection, just under half of residents indicated they were currently displaced from their homes. However, of the 39 residents who were not currently displaced, six indicated that they had returned to their homes in the past week, and five indicated that they were essentially camping in homes that lacked utilities or had sustained extensive damage. Two-thirds of residents indicated that their neighbors were currently displaced. In terms of housing and household characteristics, approximately three-quarters of the residents sampled were homeowners. In some cases, these residents owned recreational vehicles and lived in them as their primary residence, which presented unique challenges for household recovery. More than half of the residents interviewed indicated one or more persons age 65 or older lived in their household. Forty-seven percent of residents indicated they lived with a person who had a disability, and 37 percent indicated that there were children under 18 present in the household.

Table 1: Resident Characteristics

Table 1: Resident Characteristics

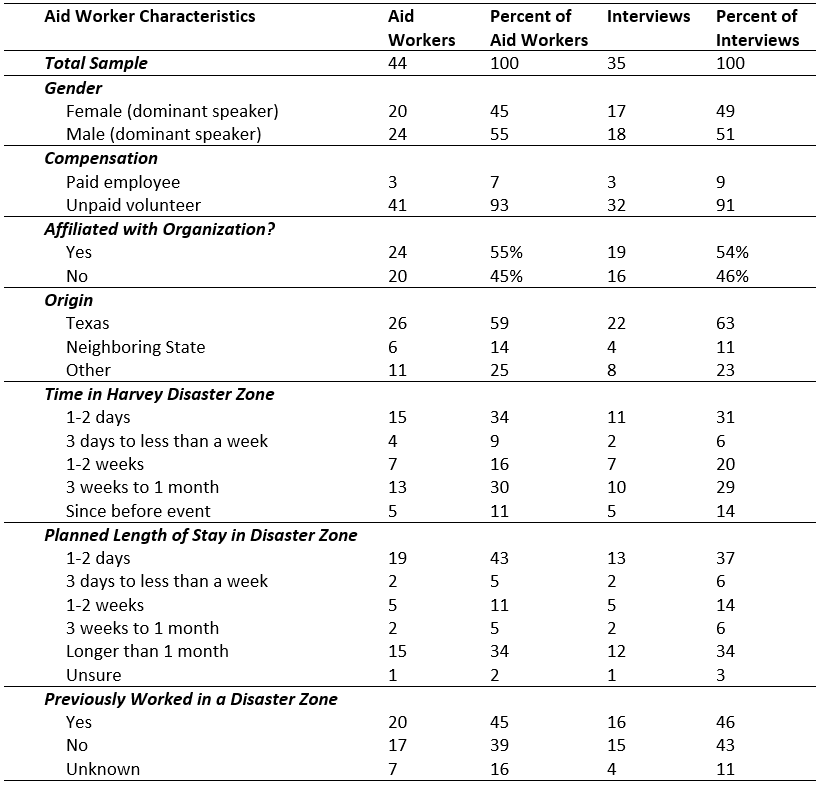

Table 2 displays characteristics of aid workers. Because five of the 35 interviews were conducted with two or more aid workers, this table breaks out characteristics by individual aid worker and by interview. Of the aid workers interviewed, slightly more than half were male, and more than 90 percent were working in the disaster zone on a volunteer basis. More than half were affiliated with a parent organization, though it is striking that 45 percent identified themselves as independent. Three-quarters of aid workers came from Texas or an adjacent state. When asked about the length of time spent working in the Harvey disaster zone, the majority of aid workers fell into one of two groups—those who had only been active during the weekend (one to two days) interviews were conducted and those who had been active since the hurricane (three weeks to one month). This bifurcation pattern was more pronounced when aid workers were questioned about their planned length of stay in the disaster zone. Most expected to be present and actively serving for either one or two days total or for longer than a month. Just more than 50 percent of aid workers interviewed indicated they had served in previous disaster zones, typically after hurricanes and floods. Hurricane Katrina was the most cited event where aid workers had gained experience before Harvey relief efforts.

Table 2: Aid Worker Characteristics

Analysis

Interview data collected in the field were aggregated in Google Forms and then analyzed using Microsoft Excel. To answer Research Question 1, two separate lists of gathering places were compiled using resident data and aid worker data. Duplicate references to the same gathering place were eliminated from both lists to identify unique gathering places and their functions. These data are presented below in the subsections on resident gathering places and aid worker gathering places. The two exhaustive lists generated were then combined and the same process of eliminating duplicate references was undertaken to produce a single list of gathering places in the study communities and a comprehensive typology of these gathering places. To answer Research Questions 2 and 3, thematic coding of interview data was undertaken. To increase the validity of findings, each author coded independently, then met to compare and reconcile key themes.

Findings

This section presents the results of the content and thematic analyses of interview data on gathering places one month after Hurricane Harvey in South Texas. Findings are organized by research question. First, we discuss unique gathering places, their functions, and differences between places identified by residents and aid workers. Second, themes related to interactions among and between residents and aid workers are examined. Finally, we identify and discuss aspects of gathering places that limit their effectiveness in delivering vital recovery resources, information, and emotional support.

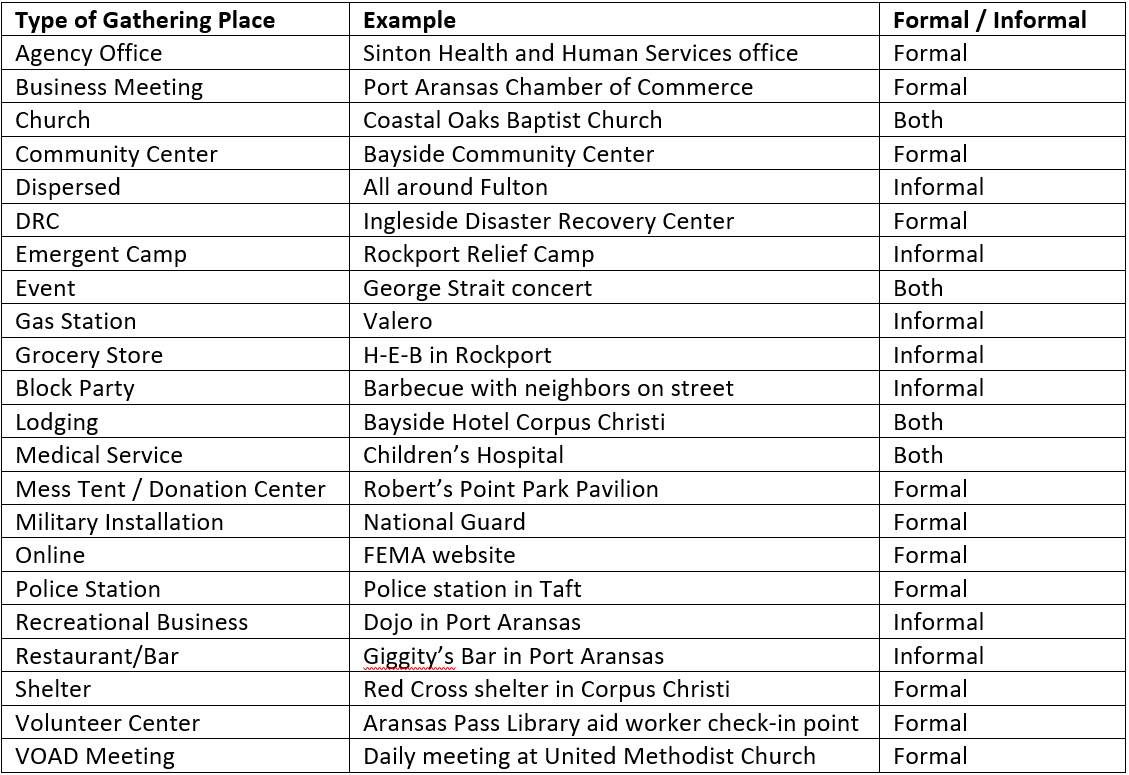

Gathering Places

Twenty-two distinct types of gathering places were identified through interviews with residents and aid workers (Table 3). These gathering places included formal locations, where established and expanding organizations provided disaster-specific services or resources through institutionalized channels, and informal locations, where residents and aid workers shared information or resources on an ad hoc basis. Instances where residents congregated with neighbors or friends for pre-planned purposes but in non-regular (or non-specific) locations were categorized as informal gathering places. Residents tended to identify their street, their neighborhood, or a familiar haunt as a location for informal gathering, but proper place names were avoided, hence it was not possible to assign a more specific label. Aid workers described similar informal interactions with residents; however, these were often framed as chance encounters that happened “all over town.” These gathering places were categorized as dispersed based on the nebulous geographic description given by aid workers. Dispersed gatherings usually involved aid workers and residents engaging either one-on-one or two-on-two. These exchanges typically resulted in a request for volunteer labor, offering of directions, or sharing of hugs. Also, noteworthy in this type classification is the combination of mess tents and donation centers, which were often housed together.

Four types of gathering places are designated as both formal and informal because of their ability to serve dual purposes. These included churches, events, lodging, and medical services. Interviewees identified churches as formal places to shop for free disaster supplies, obtain volunteers for debris removal, and post on community needs bulletin boards. Additionally, other interviewees identified churches as places providing informal spiritual and emotional support through attendance and one-on-one interaction with congregation members. A George Strait concert held as a disaster relief benefit was identified, as well as several local school pep rallies, where neighbors reunited for the first time. Lodging included formal accommodations set up specifically for aid workers, such as the USS Lexington where AmeriCorps and FEMA Corps volunteers were being housed, as well as local hotels in the area heavily damaged by Harvey, which provided a space for chance encounters between displaced residents and aid workers. Finally, while most examples of medical services mentioned were formal in nature, Green Cross, an organization that mobilizes mental health professionals to provide crisis assistance, was also noted. The next sections discuss how the types of gathering places and their proportion differed between residents and aid workers interviewed.

Table 3: Types of Formal and Informal Gathering Places Identified by Interviewees

Table 3: Types of Formal and Informal Gathering Places Identified by Interviewees

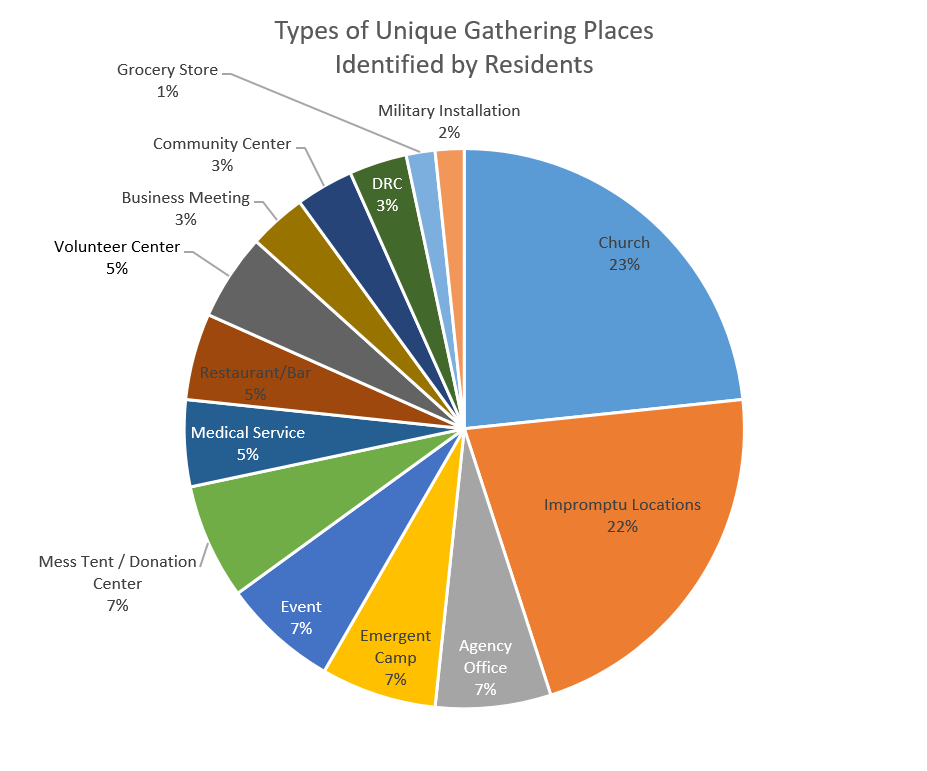

Resident Gathering Places

Of the 81 residents interviewed, only 61 were able to identify at least one gathering place. The remainder stated either that there were no gathering places or that they did not know of any. Residents identified 91 total gathering places, with 57 being unique gathering places. Each unique gathering place was classified according to type (Table 3). However, due to vague descriptions of some locations, it was impossible to distinguish the multiple functions served by two of these gathering places. These included the Port Aransas Community Center, a community center that simultaneously functioned as a Disaster Recovery Center and a volunteer check-in point, and Downtown Rockport, home to a mess tent/donation center, as well as agency offices for the Small Business Administration and the Texas Wind Insurance Agency. These two places are represented twice in the dataset, once for each unique function. Figure 1 shows a breakdown of unique gathering places by type, adjusting for multiple functions (n=61). In all, residents identified fourteen types of gathering places. Churches (23 percent) and impromptu locations (22 percent) were the most common types. Here impromptu locations refer to instances where the place reference provided by the resident was non-specific. This category includes loosely planned gatherings (e.g., neighborhood cookouts, meeting friends at home) and chance encounters with other residents and aid workers (e.g., meeting on the street, volunteer workers showing up unannounced at a residence).

Figure 1: Resident-identified unique gathering places by type, adjusting for multiple functions of each gathering place.

Figure 1: Resident-identified unique gathering places by type, adjusting for multiple functions of each gathering place.

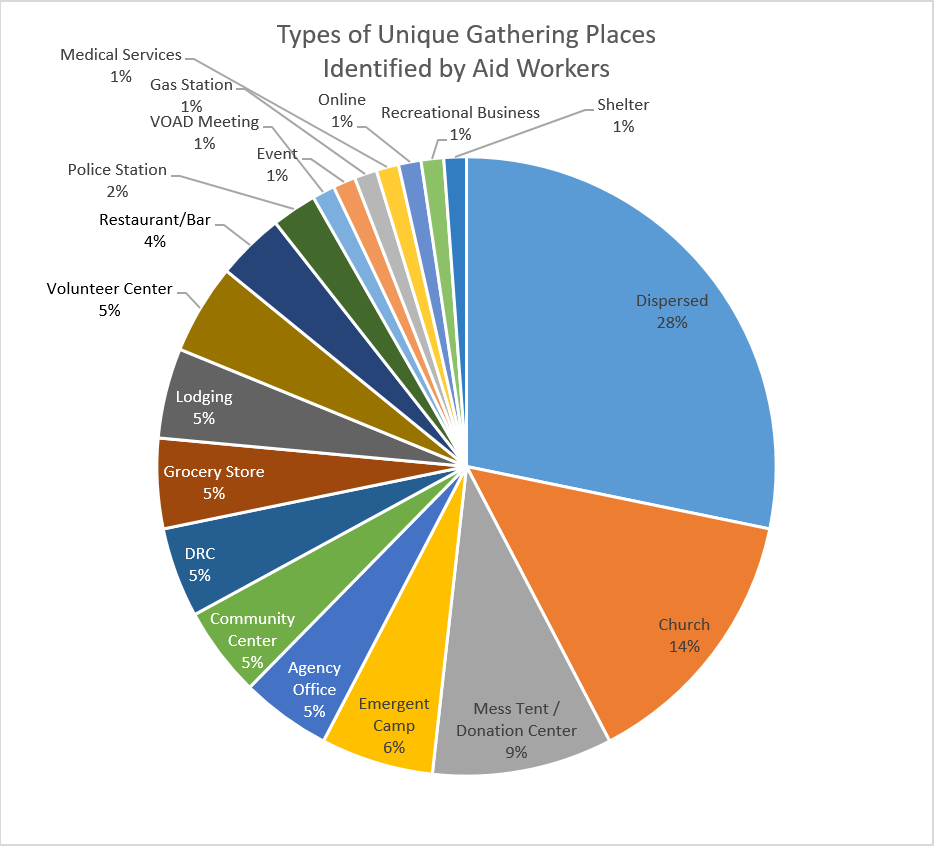

Aid Worker Gathering Places

Aid workers identified a total of 149 gathering places, and 81 of these were unique. All but six interviews with aid workers resulted in the identification of gathering places. Among the unique gathering places, three of them performed multiple functions. In addition to the Port Aransas Community Center, mentioned above, two churches assumed secondary disaster-specific roles as a daily meeting location for National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD) and a donations center. Figure 2 displays a breakdown of unique gathering places by type, adjusting for multiple functions (n=85). Aid workers identified a wider variety of gathering place types than did residents—19 types in all. The most common types of places identified were dispersed locations (27 percent), churches (13 percent), and mess tents/donation centers (9 percent).

Figure 2: Aid worker-identified unique gathering places by type, adjusting for multiple functions of each gathering place.

Figure 2: Aid worker-identified unique gathering places by type, adjusting for multiple functions of each gathering place.

Interactions between Residents and Aid Workers

A significant theme that emerged from the aid worker interviews was the relative isolation of aid workers from community residents. Interaction was generally restricted to the relief effort. Specifically, when asked about where they interact with residents, 77 percent of aid workers they only interacted with residents during their work tasks (13 percent of aid workers did interact with residents outside of work, primarily at local businesses, and 11 percent did not describe where their interactions with residents took place).

Among the VOAD groups located in the area, only one organization specified that they had regular interactions with a part of the local population. Team Rubicon was housed at the local Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) Hall and were in regular contact with veterans through that venue. During the day, they were based out of the Aransas Pass Civic Center, which also housed the Mennonite Disaster Response volunteers. However, when asked if they socialized with local residents other than those at the VFW, the interviewee stated that they did not. Team Rubicon did socialize with volunteers from other groups, and within their own organization—team members would share a beer together at the end of the work day. During an interview at Team Rubicon’s command post, a musician approached and offered to put on a concert for the team at the VFW hall, signaling that the community was aware of their lodgings.

Our findings suggest that volunteering with established organizations may limit individual agency to socialize with residents, whereas independent aid workers may be less restricted. One instance that illustrates the latter suggestion was an the case of an independent aid worker who traveled to the area to help his friend’s family and appeared to have ready access to residents. He volunteered during the day, engaging in activities such as construction and helping with donations. In the evenings, he worked at a restaurant/bar owned by his friend’s family. During this time he was able to interact with residents and provide emotional support through those interactions.

Emergent Camps

Emergent camps represented one type of gathering place where aid workers and residents came together, not always in positive ways. In several camps we visited, we observed tension between camp volunteers and aid workers affiliated with established VOADs or the government. Thirty-one percent of aid workers we interviewed identified one of two emergent camps— Rockport Relief Camp (RRC) and Texas Camp David (TCD)—as areas where they interacted with residents. We also visited a third emergent camp calling itself the Cajun Commissary. Interviews at this camp revealed it to be a female-run organization loosely affiliated with the Cajun Navy. We describe the first two camps in depth, as they were more frequently identified by interviewees.

The RRC was located on a campground in Rockport, Texas. It functioned as a donation distribution site and housed tents and RVs occupied by displaced residents and aid workers. According to several interviewees, the woman who owned the property assumed the role of camp leader and created an informal structure to govern the camp. This structure included designated lights-out times, penalties for excessive noise or drug possession, and rules about who was allowed in camp. FEMA Corps volunteers and at least one FEMA employee were operating in the RRC when we visited, and they also adhered to this governing structure. A displaced female resident who lived in the camp explained to us that the structure protected the camp against outside influences. She also vocalized suspicion about the FEMA contingent stationed there. To limit FEMA Corps power, the camp leader required representatives to stay under a designated tent, and they were not permitted to talk to camp visitors outside of the tent.

Located in Port Aransas, Texas Camp David (TCD) housed aid workers from outside the affected area and displaced residents. An employee of the City of Port Aransas explained that the displaced residents who lived in TCD had been displaced from a mobile home community. Their homes had been destroyed, and they refused to leave the island because they were concerned they would never be able to return. The aid workers in TCD were volunteers from across Texas (e.g., Bastrop, Padre Island, Fort Worth, Corpus Christi, and Mason). There was also a volunteer that we interviewed from Illinois. At the time of our interviews in TCD, the camp had been operating for 25 days. TCD also held a non-denominational service every Sunday morning at 10 a.m. for camp residents or anyone else who wished to attend.

Damage in Bayside, Texas, observed by the authors during a windshield survey on September 21. ©Ronald Schumann, 2017.

Damage in Bayside, Texas, observed by the authors during a windshield survey on September 21. ©Ronald Schumann, 2017.

Recurrent themes at all three camps included an anti-government sentiment and frustration with the limitations of government aid. For the camp leaders we interviewed at the RRC and Cajun Commissary, this seemed to justify their continued operation in the recovery zone. At TCD, one interviewee said that the government could no longer help people in disasters and that she was relying on her faith to see her through in the future. While we did not ask specifically about individual perceptions of government aid following disasters, this theme emerged organically in our conversations with aid workers and residents. It could be an interesting avenue for future research.

Limitations of Gathering Places and Displacement

In addressing the limitations of gathering places, we recognized that distance created an obstacle for some residents in accessing gathering places. Of the 49 percent of residents who were displaced from their homes, 18 of those individuals were displaced outside of their communities, and they were located, on average, 64 miles away from their pre-Harvey residences. Four of these respondents reported being displaced over 150 miles from their homes .

Respondents identified distance from their home communities as an obstacle to their recovery and overall wellbeing. For instance, a young pregnant woman had been displaced along with her husband and child was frustrated by her inability to access health care in her temporary community. Her primary physician would not release her to another doctor since her pregnancy was high-risk, so she had to drive several hours in each direction access prenatal care.

For several of our respondents, the inability to access formal information and resources in their temporary communities was a challenge. Interviewees in line at the FEMA DRC in Ingleside, Texas, had traveled from places as distant as San Antonio, Padre Island, Brownsville, Three Rivers, and Laredo. These displaced residents reported difficulty getting answers to their concerns over the phone or on the internet. In the absence of DRCs in communities they had been displaced from, these residents traveled to either Ingleside or Port Aransas to access a DRC.

Limitations of Gathering Places in Supporting Communal Recovery

Many of the gathering places designed to meet disaster recovery needs four weeks after Harvey served survivors and their households as consumers and did little to foster a sense of community in the process. This assertion is informed by both interviews and our own observations. It is worth noting, however, that this lack of communalism is endemic to formal disaster relief and assistance programs. While the intent is to have an aggregate effect on community recovery, programs and services that determine eligibility on an individual or household basis contribute to a piecemeal recovery.

During our fieldwork, we observed how residents queued solemnly at the Ingleside DRC, appearing detached and socially distant from other community members in line, although those who shared their stories with us told similar tales of recovery struggles or displacement. Donation centers established by churches or set up at the emergent relief camps supported isolation and consumerism in much the same way. We observed individuals coming in looking for household items, but the experience largely simulated a trip to a retail store, shopping carts and all. Survivors sometimes asked a relief camp worker or donation center volunteer for a particular item or even a hug and a chat, but this service was performed with the intent of attending to as many individuals as possible rather than fostering connections between community members to collectively meet needs.

Meal-prep operations like the ones at Texas Camp David in Port Aransas were also designed as grab-an-go fast food operations with little seating for survivors and little reason to congregate and mingle. Even dispersed encounters between aid workers and residents in the grocery stores and parking lots around the affected towns seem to perpetuate this consumeristic matching of supply and demand at the household level when it came to volunteer labor. In instances where these dispersed gatherings identified a labor-intensive job at a survivor’s home requiring resource inputs from several aid groups, our interviewees attested to a lack of mixing or mingling between the cooperating aid groups. Hence, we observed this lack of communal recovery in all types of interactions (among residents, among aid workers, and between residents and aid workers).

The primacy of the internet as a one-stop-shop for information on recovery resources may also be exacerbating the trend toward individualistic and consumeristic recovery services in the short-term. In one-third of resident interviews (25 of 76), when asked where interviewees had physically been going for resources, online was a response. Furthermore, in one-sixth of interviews (13 of 25) residents noted that the internet had been the only location where they had sought out disaster-related information or resources, apart from the disaster recovery center, where all interviews in this subset took place. Despite the inaccuracy of referencing a virtual place instead of a physical location to answer the question (even after clarification by the researchers), such a finding is striking.

Several exceptions to the rule of individual-oriented aid did emerge. Two interviewees identified a functioning martial arts studio in Port Aransas, which provided a sense of community and a healthy outlet for recovery-related stresses. Small business owners in Port Aransas had congregated organically at Giggity’s Bar shortly after the storm to reunite as a group and collectively take an accounting of damages, needs, and recovery plans. During our research trip, we attended a formal meeting of small business owners organized by the Port Aransas Chamber of Commerce to discuss funding long-term recovery. The initial meet-and-greet portion of this meeting provided a space for community bonding and mutual encouragement. Residents also mentioned that informal neighborhood gatherings and high school pep rallies lent to informal bonding and neighboring.

Lack of Gathering Places Offering Emotional Support

A recurring theme among the residents was the lack of emotional support centers in the community. When asked if there were gathering places specifically addressing emotional support needs, residents generally answered no. Emotional support and community support has been mentioned throughout recovery literature as an important feature in successful recovery. Therefore, the absence of formalized gathering places offering emotional support services is problematic.

Apart from religious services, we only identified one formal gathering place that focused on the emotional support needs of residents. An Episcopal church in Port Aransas offered both a Thursday evening meditation group as well as a Friday evening mental health group, which one resident called a “Harvey Hangover” meeting. These meetings were led by a local psychologist and local counselors. The Thursday meditation event was advertised as “a safe place for those who wish to meet for a time of meditation and discussion,” while Friday evenings were billed as “a safe place for those who wish to meet to discuss the effects of the hurricane, while sharing hope and helpful ideas.”

The lack of formalized emotional support notwithstanding, interviewees identified numerous other informal gathering places where friends and neighbors offered emotional support. One community near Rockport, Texas, hosted regular pot lucks, and community residents actively sought one another out to check in and maintain their social bond. We also heard of a small group of friends from Port Aransas who, before Harvey, had gathered for a regular happy hour. Since all the friends were displaced to Corpus Christi, they continued their happy hours even after the storm. This provided emotional and community support for these individuals, even though they were unable to return to their hometown.

In addition to resident-organized informal gatherings, 94 percent of aid workers we interviewed stated that they did offer emotional support to residents. One aid worker, an independent volunteer, described how she offered residents one-on-one emotional support by just “lovin’ on them.” Hence, residents could find informal means of emotional support from aid workers even in the absence of formal gathering places in any of the three communities devoted to this purpose. The degree to which formal and informal channels for emotional support remain available to residents throughout the recovery process remains to be seen. Also noteworthy in our fieldwork was the total absence of formal gathering places offering emotional support for aid workers.

Conclusions and Implications

This research aimed to identify and characterize gathering places in three South Texas coastal communities four weeks after Hurricane Harvey. We identified 22 types of gathering places (11 formal, seven informal, and four that were both formal and informal). These included ephemeral places that were newly emergent and others that would imminently disappear. This research has increased our understanding of where and how residents and aid workers access services and information one month after a major disaster. Several key themes emerged from observations and interviews at these gathering places. Among them were the broad lack of emotional support, the limited extent of interaction between residents and aid workers, the persistence and function of emergent camps, and the limited degree to which community recovery efforts actually support communal recovery.

Most apparent during our research was the shortage of formal emotional support channels for aid workers and for residents. When comparing only Port Aransas to the Rockport/Fulton/Aransas Pass area, larger community size appears to correlate with lower levels of emotional support; however, our smallest community, Bayside, lacked emotional support services entirely. High levels of displacement and severe damage to all three churches in Bayside may be a complicating factor. Given the centrality of mental health services in a successful recovery, monitoring disparities and changes in emotional support over time is a promising avenue for further research.

Based on previous experiences in disaster-affected areas, the limited degree of contact between aid workers and residents was surprising. One author has experience volunteering after five disaster events, including one internationally (Haiti), and four in the United States. In most of these experiences, she remembers volunteers freely interacting with and, in some cases, socializing with residents in their spare time. However, in this research, interactions appeared more regimented. Apart from encounters between individual aid workers and residents dispersed throughout the disaster zone during work hours, the only instances of such interaction took place in the emergent camps (where displaced residents and aid workers interacted) and at Team Rubicon’s VFW hall gatherings (where Rubicon veterans and local veterans met for drinks and conversation). The low degree of interaction between residents and aid workers could impact the workers’ effectiveness in communicating with locals and addressing their needs. Furthermore, the self-containment of aid worker feeding and housing operations could also indirectly delay small business recovery since visiting workers do not patronize reopened businesses for these services.

Emergent camps, where residents and aid workers cohabitated, and the social norms governing their operation were unique among the set of gathering places investigated. Like emergent organizations, these camps were created by non-governmental groups, and in two of three cases, by groups that had not existed before the disaster. Conversations with individuals in these camps unearthed anti-government sentiments. Further research into emergent camps is needed to better understand what factors motivate their development and condition their interactions with established and expanding response organizations in the disaster zone.

Finally, a worrisome finding of this study was the lack of recovery efforts that either leveraged or supported community cohesiveness. Instead, a high degree of individualism and consumerism were found embedded in the current set of gathering places. Perhaps as short-term recovery transitions to long-term, place identity and place bonding may come to frame emergent gathering places and contribute to greater community cohesion. At four weeks post-event, it is clear that the aims of community recovery are not necessarily aligned with communal recovery. The question remains, however: will the evolution of gathering places enable such communal recovery, or will these changes simply give way to increased social fragmentation?

References

Aldrich, D.P. 2012. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Aldrich, D.P., and M.A. Meyer. 2015. Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral Scientist 59 (2): 254-269.

Bradshaw, K. 2017. Port Aransas still facing long recovery after Harvey, mayor says in update. San Antonio News-Express, 4 October 2017.

Brown, B.B., and D.D. Perkins. 1992. Disruptions in Place Attachment. Human Behavior and Environment 12: 279-304.

Chamlee-Wright, E., and V.H. Storr. 2009. "There's No Place Like New Orleans:" Sense of Place an Community Recovery in the Ninth Ward After Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Urban Affairs 31 (5): 615-634.

Chang, J. 2017. After Hurricane Harvey, Port Aransas faces long road to recovery. Austin American-Statesman, 13 October 2017.

Crow, K. 2017. Port Aransas feels economic pinch after Hurricane Harvey. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 16 September.

Cuba, L., and D.M. Hummon. 1993. A Place to Call Home: Identification with Dwelling, Community, and Region. The Sociological Quarterly 34 (1): 111-131.

Erikson, K. 1976. Everything in Its Path: Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood. New York: Simon & Schuster.

FEMA. 2017. Historic Disaster Response to Hurricane Harvey in Texas. Washington, D.C.: Department of Homeland Security.

Fothergill, A. 2004. Heads above Water. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Francaviglia, R.C. 1978. Xenia Rebuilds: Effects of Predisaster Conditioning on Postdisaster Redevelopment. Journal of the American Planning Association 44 (1): 13-24.

Fritz, C.E., and J. Mathewson. 1957. Convergence Behaviors in disasters; a problem in social control. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council.

George, C., M. Kadifa, L. Ellis, and K. Blakinger. 2017. Storm deaths: Harvey claims lives of more than 75 in Texas. Houston Chronicle, 9 October.

Haas, J.E., R.W. Kates, and M.J. Bowden. 1977. Reconstruction Following Disaster. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hummon, D.M. 1992. Community Attachment: Local Sentiment and Sense of Place. In Place Attachment, edited by I. Altman and S. M. Low, 253-278. New York: Plenum Press.

Jervis, K. 2017. How the city at the ground zero of Hurricane Harvey is moving forward 7 weeks later. USA Today, 17 October 2017.

Kaniasty, K., and F.H. Norris. 1995. In search of altruistic community: Patterns of social support mobilization following Hurricane Hugo. American Journal of Community Psychology 23 (4): 447-477.

Kendra, J.M., and T. Wachtendorf. 2003. Reconsidering convergence and converger legitimacy in response to the World Trade Center disaster. In Terrorism and Disaster: New Threats, New Ideas, edited by L. Clark: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Milligan, M.J. 1998. Interactional Past and Potential: The Social Construction of Place Attachment. Symbolic Interaction 21 (1): 1-33.

National Hurricane Center. 2017. Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Miami: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Office for Coastal Management. 2018. Fast Facts: Hurricane Costs. NOAA 2018 [cited 29 July 2018]. Available from https://coast.noaa.gov/states/fast-facts/hurricane-costs.html.

NRC (National Research Council). 2012. Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

NWS (National Weather Service). 2017. Major Hurricane Harvey -- August 25-29, 2017.

Phillips, B.D. 2013. Disaster Recovery. 2nd ed. ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Pretty, G.H., H.M. Chipuer, and P. Bramston. 2003. Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology 23 (3): 273-287.

Ritchie, L.A., and D.A. Gill. 2007. Social Capital Theory as an Intergrating Framework in Technological Disaster Research. Sociological Spectrum 27 (1): 103-129.

Scannell, L., and R. Gifford. 2010. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30: 1-10.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Census 2010 Summary File 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Van Wassenhove, L.N. 2006. Humanitarian aid logistics: supply chain management in high gear”, Journal of the Operational Research Society 57 (5): 475-489.

Zhang, Y., M.K. Lindell, and C.S. Prater. 2009. Vulnerability of community businesses to environmental disasters. Disasters 33 (1): 38-57.

References in Order of Appearance

-

Kaniasty, K., and F.H. Norris. 1995. In search of altruistic community: Patterns of social support mobilization following Hurricane Hugo. American Journal of Community Psychology 23 (4): 447-477. ↩

-

Van Wassenhove, L.N. 2006. Humanitarian aid logistics: supply chain management in high gear”, Journal of the Operational Research Society 57 (5): 475-489. ↩

-

Fritz, C.E., and J. Mathewson. 1957. Convergence Behaviors in disasters; a problem in social control. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council. ↩

-

Haas, J.E., R.W. Kates, and M.J. Bowden. 1977. Reconstruction Following Disaster. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ↩

-

Zhang, Y., M.K. Lindell, and C.S. Prater. 2009. Vulnerability of community businesses to environmental disasters. Disasters 33 (1): 38-57. ↩

-

Phillips, B.D. 2013. Disaster Recovery. 2nd ed. ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ↩

-

FEMA. 2017. Historic Disaster Response to Hurricane Harvey in Texas. Washington, D.C.: Department of Homeland Security. ↩

-

National Hurricane Center. 2017. Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Miami: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. ↩

-

Crow, K. 2017. Port Aransas feels economic pinch after Hurricane Harvey. Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 16 September. ↩

-

Jervis, K. 2017. How the city at the ground zero of Hurricane Harvey is moving forward 7 weeks later. USA Today, 17 October 2017. ↩

-

Bradshaw, K. 2017. Port Aransas still facing long recovery after Harvey, mayor says in update. San Antonio News-Express, 4 October 2017. ↩

-

Chang, J. 2017. After Hurricane Harvey, Port Aransas faces long road to recovery. Austin American-Statesman, 13 October 2017. ↩

-

George, C., M. Kadifa, L. Ellis, and K. Blakinger. 2017. Storm deaths: Harvey claims lives of more than 75 in Texas. Houston Chronicle, 9 October. ↩

-

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Office for Coastal Management. 2018. Fast Facts: Hurricane Costs. NOAA 2018 [cited 29 July 2018]. Available from https://coast.noaa.gov/states/fast-facts/hurricane-costs.html. ↩

-

NWS (National Weather Service). 2017. Major Hurricane Harvey -- August 25-29, 2017. ↩

-

Ritchie, L.A., and D.A. Gill. 2007. Social Capital Theory as an Intergrating Framework in Technological Disaster Research. Sociological Spectrum 27 (1): 103-129. ↩

-

Aldrich, D.P. 2012. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ↩

-

NRC (National Research Council). 2012. Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. ↩

-

Aldrich, D.P., and M.A. Meyer. 2015. Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral Scientist 59 (2): 254-269. ↩

-

Brown, B.B., and D.D. Perkins. 1992. Disruptions in Place Attachment. Human Behavior and Environment 12: 279-304. ↩

-

Scannell, L., and R. Gifford. 2010. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30: 1-10. ↩

-

Milligan, M.J. 1998. Interactional Past and Potential: The Social Construction of Place Attachment. Symbolic Interaction 21 (1): 1-33. ↩

-

Pretty, G.H., H.M. Chipuer, and P. Bramston. 2003. Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology 23 (3): 273-287. ↩

-

Cuba, L., and D.M. Hummon. 1993. A Place to Call Home: Identification with Dwelling, Community, and Region. The Sociological Quarterly 34 (1): 111-131. ↩

-

Francaviglia, R.C. 1978. Xenia Rebuilds: Effects of Predisaster Conditioning on Postdisaster Redevelopment. Journal of the American Planning Association 44 (1): 13-24. ↩

-

Erikson, K. 1976. Everything in Its Path: Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood. New York: Simon & Schuster. ↩

-

Fothergill, A. 2004. Heads above Water. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ↩

-

Chamlee-Wright, E., and V.H. Storr. 2009. "There's No Place Like New Orleans:" Sense of Place an Community Recovery in the Ninth Ward After Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Urban Affairs 31 (5): 615-634. ↩

-

Kendra, J.M., and T. Wachtendorf. 2003. Reconsidering convergence and converger legitimacy in response to the World Trade Center disaster. In Terrorism and Disaster: New Threats, New Ideas, edited by L. Clark: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↩

-

Hummon, D.M. 1992. Community Attachment: Local Sentiment and Sense of Place. In Place Attachment, edited by I. Altman and S. M. Low, 253-278. New York: Plenum Press. ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Census 2010 Summary File 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. ↩

Schumann, R. & Nelan, M. (2018). Gathering Places During the Short-Term Recovery Following Hurricane Harvey Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 268). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/gathering-places-during-the-short-term-recovery-following-hurricane-harvey