Hurricane Irma: Inmate Workers and Inmate All-Hazard Firefighters in Disasters

Publication Date: 2020

Abstract

Prisoners occupy a variety of roles in an emergency management context. Incarcerated populations are often viewed as dangerous and a potential threat to the safety of facilities and surrounding communities. Recognition of prisoners as a vulnerable population who could not provide for their own safety and welfare in a disaster, has also recently gained momentum. Prisoners are also a labor resource for emergency management, providing assistance to impacted communities and the state throughout the disaster life cycle. Because of the social and geographic isolation of prison systems, however, the role and experiences of prisoners in disasters remain drastically under-researched. Qualitative interviews with corrections, fire, emergency, and government officials were used to examine the challenges faced by the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) in providing for the safety and welfare of prisoners and staff during Hurricane Irma. The study also looks at the contributions of the GDC Fire and Life Safety inmate firefighter program and the assistance of inmate work crews from the general prison population. Preliminary results reveal the role of inmate workers and inmate firefighters in both local and state disaster operations, the types of assistance prison inmates provide. I end with a discussion on the perceptions of inmates as they work in communities, and the implications of such perceptions. Specifically, I discuss the perceptions of inmates as dangerous to the community and the perceptions of the disaster context as dangerous to inmates.

Introduction

Sudden onset disasters—floods, hurricanes, tsunamis, and forest fires—destroy homes, property, and economic opportunities and are on the rise worldwide (Munich Re 20171; NOAA 20172). The historic hurricane and wildfire seasons of 2017 were characterized by record-breaking damages. Examples of their significant impact on incarcerated populations could be seen in Hurricane Harvey, which necessitated the evacuation of nearly 6,000 prisoners in Texas; Hurricane Irma, which prompted the evacuation of nearly 2,000 prisoners across Georgia; and in California, where the state called on nearly 2,000 inmate firefighters to battle devastating fires in December (McCullough 20173; Fonseca 20174). As the nation grapples with how to respond to the rising needs of states impacted by disasters, the role and experiences of prisoners may become more apparent and debated.

Across the United States, it is common for inmate workers to be used as a labor source to prepare for and respond to emergencies and disasters. The most visible and commonly debated type of inmate labor in disasters remains the use of inmate firefighters for wildland fire suppression in western states, particularly the state of California (CITE). However, inmate workers can be assigned to assist with a variety of labor tasks associated with disasters throughout the United States. As a function of the Stafford Act and the FEMA Public Assistance Program, states are reimbursed for the costs of using prisoner labor for disaster management including any wages inmates receive as part of their work assignment as well as the costs of providing security guards, food, and lodging (FEMA 20185). This policy incentivizes using prison workers as a cheaper alternative to free civilian workers. While many anecdotal examples are available throughout news media, little research has examined this practice in depth. Inmate workers are used for a variety of tasks, therefore they are often used as a resource in increasing a community’s disaster resilience. The practice, however, remains largely invisible, and so current studies of disaster resiliency do not address the role prison labor plays in disasters.

Hurricane Irma and the Georgia Prison System

The Georgia prison system is one of the largest in the U.S., incarcerating nearly 52,000 persons in 2017 (GDC 2017). In preparing for the predicted impacts of Irma, the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) evacuated two correctional facilities located within Governor Nathan Deal’s mandatory evacuation zone. Coastal State Prison which held 1,701 inmates and Coastal Transitional Center which housed 252 inmates (GDC 2017). Transitional centers differ from state prisons in the type of security measures in place for incarcerated persons. According to the GDC, transitional centers are structured to provide “work release” where inmates must find a job in the community while they live at the center. The majority of those incarcerated within transitional centers are released on parole after about six months (GDC n.d.). Facilities prepared for the potential impacts of the hurricane by stocking up on basic supplies including food, water, and medical supplies (GDC 2017).

Visitation at all correctional facilities housing state inmates in Georgia was cancelled beginning September 7th and was not restored until September 16th and 17th (GDC 2017; GDC 2017). As Hurricane Irma pummeled the region, 31 state corrections institutions lost power in Georgia. After the loss of power, the institutions ran on back-up generator power until power was restored to the facilities (GDC 2017).

Inmate Labor in Georgia

Georgia Inmate Work Crews

The United States Constitution’s 13th Amendment states that subjecting persons to slavery, a condition of forced and uncompensated labor is illegal within the nation except for persons who have been convicted of a crime (CITE). In addition to federal law, states have also included within their own official codes laws which require inmates to work while incarcerated, further formalizing their forced servitude. In the state of Georgia, all able-bodied inmates are required to work. According to the official Georgia code,

“Each inmate not enrolled in a full-time training or rehabilitative program shall be assigned work consistent with his (her) physical and mental capacity and security needs of the individual. He (she) shall be required to perform whatever work is assigned, such as work essential to the operation of the institution, maintenance of public roads, support of public works, or performance of such other tasks as are assigned by the institutional authorities and are within the legal prerogatives of the State Board of Commission” (O.C.G.A. 125-3-5-.03).

The most common beneficiaries of inmate workers are the state government of Georgia and local municipalities throughout the state. Various state departments and agencies contract with the GDC to include inmate workers such as the Department of Transportation, Georgia Forestry Commission, Georgia State Patrol, the Georgia National Guard, the Department of Natural Resources as well as colleges and hospitals throughout the state (GDC 2017).

Local governments as well as the state government of Georgia can contract with the GDC to acquire inmate workers to work on local and state projects. When a local government contracts to obtain inmate workers, the work crew is assigned to the responsibility of a local department, most often public works. Under the supervision and direction of public works departments, inmates often provide community services like cleaning up parks and grounds maintenance.

The Georgia Department of Corrections Fire and Life Safety Program

Within the United States, the practice of using inmate workers for emergency and disaster labor varies across different states and regions depending on the types of hazards within the area. For example, inmates are commonly assigned to participate in wildland fire suppression across several Western states. In the U.S. state of Georgia however, inmates serve a unique role within emergency and disaster management by acting as all-hazard or all-risk firefighters on behalf of local communities as well as the state government. “All-hazard” firefighters or fire departments are those that are trained to respond to any type of hazard or emergency from structure fires to hazardous materials incidents and large scale-disasters (Crosbie 2014).

The Georgia Department of Corrections operates nineteen fire stations located on prison grounds and five additional fire teams housed within county prisons (GDC 2017). In interviews I learned that one additional fire team is housed within a civilian county’s fire station. At least one county prison’s fire department acts as their county’s only fire department with inmate firefighters and local civilian volunteers (CITE). Prison fire teams operating from state prison grounds are typically directed by a separate GDC fire chief while those housed in county prisons typically respond under the leadership of the community’s fire chief. Through memorandums of agreement, the GDC fire teams respond to at least 51 local counties and cities. According to GDC policy, inmate fire departments must have at least eight inmate firefighters to fully staff the department. Each GDC inmate fire department must also provide 24-hour services to municipalities with contracted memorandums of agreement (GDC 2018).

GDC policy also dictates that all inmate firefighters must sign a “waiver of liability” (GDC 2011). I was not able to find a copy of this document. It is likely that this waiver would release the Georgia Department of Corrections from legal responsibility should an inmate be injured during activities (training, emergency response) or by the hazardous conditions of emergency and disaster response. As of 2017, inmate firefighters were required to be minimum security inmates, have no physical limitations, no arson or “sexual offense” conviction, working towards their GED, and be able to read at a 10th grade level (GDC 2017).

According to the GDC (2017), inmates are trained to respond to structure fires, brush fires, hazardous materials incidents, motor vehicle accidents, railroad incidents, incidents involving bombs, emergencies involving pressurized containers, as well as medical emergencies. The expansive training inmates partake in is reflective of the “all-hazards” nature of their role in emergency response. According to their 2011 policy, the GDC Chief of Training is responsible for coordinating facility and station training (GDC 2011). Inmates will often train with local fire departments that are hosting training sessions for their own departments as well (GDC 2017).

While inmate labor for emergency and disaster management work in the U.S. outside of wildfire suppression has been discussed and critiqued within prison labor studies (Thompson 20126), there remains much we do not know about the practice in reference to how it differs from the general labor inmate workers do daily throughout the country including. Therefore, one of the core purposes of this study is to demystify the role of inmate workers in emergencies in disasters and how their labor (both forced and voluntary) may represent a foundational role in how the governments of states as well as the federal government have invested in disaster resilience.

Research Questions

- Specifically, what is the role of inmate workers in emergencies and disasters?

- How does the process of working with inmate workers in disasters differ from the daily labor inmate workers are assigned to?

- Every day across the state of Georgia, inmates respond to local emergencies including car accidents, structure fires, and emergency medical calls. This study asks, how does emergency response differ for inmate all-hazard firefighters during a state-wide disaster and what is their role in disaster response?

In this study I ask: Inmates are also understood to be a dangerous population that could pose a threat to the safety and welfare of corrections staff, as well as the surrounding communities. In this study, I ask how corrections officials manage varying perceptions of prisoners as both a potential source of danger and population for which they are responsible for protecting.

Data and Methods

My primary source of data is in-person interviews that present perspectives on emergency management and the role of prisoner labor, including general population inmates on assigned work teams or “details” and inmate firefighters during disaster. Interviews provide a naturalistic understanding and in-depth local knowledge on disaster planning, institutional operations, and the experiences of officials (Marshall and Rossman 20067; Weiss 19948). The interviews were semi-structured to allow me to gather similar data from each participant while simultaneously allowing for interviewees to initiate topics of discussion and for ideas to emerge (Weiss 1994). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. The sample was composed of individuals in Georgia that represented the Georgia Department of Corrections, the Georgia Forestry Commission, local fire and emergency medical services officials (fire chiefs, firefighters, and emergency medical technicians), emergency management and local government officials with local correctional facilities including state and county prisons. Communities represented include coastal areas that were designated for individual and public assistance by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), as well as non-coastal and coastal-adjacent areas that received the FEMA public assistance designation. Counties with known memorandums of agreement with the GDC were contacted first.

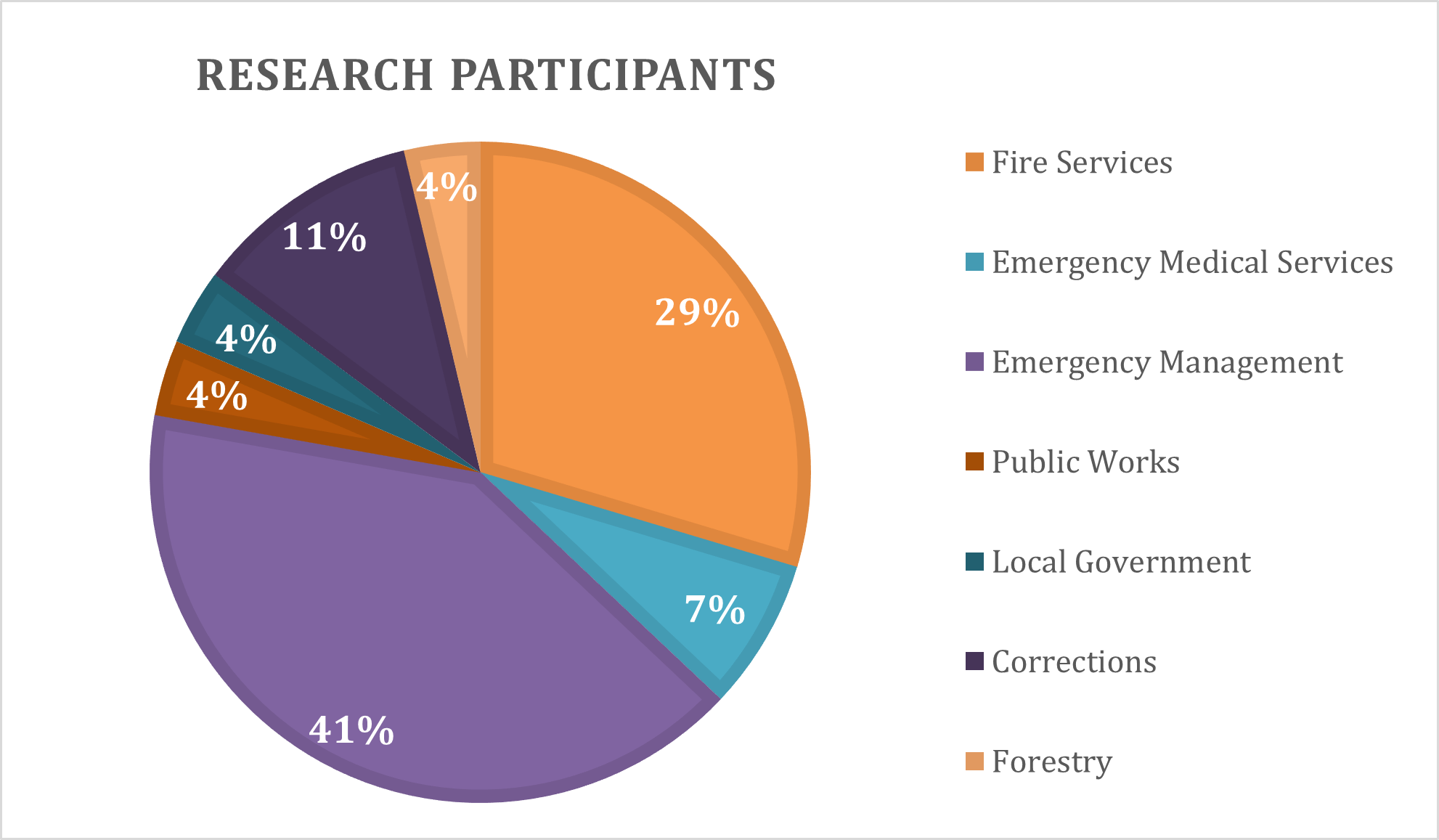

A sample of potential interviewees was drawn from media accounts, local and state government websites, and public information. Twenty officials were interviewed across the professional disciplines of emergency management, fire services, emergency medical services, corrections (prison management), public works, local government, and forestry. The majority of interviewees represented emergency management, fire services, and corrections.

Description. ©Citation Name, XXXX.

Description. ©Citation Name, XXXX.

Emergency officials often wear multiple hats, especially in rural areas which often lack adequate resources to sustain separate departments for fire services and emergency management. Three of the four county fire chiefs interviewed also served as their county’s emergency management director and one firefighter acted as the county’s deputy director of emergency management. Emergency Medical Services are also facing resources strains across the country in primarily rural areas causing municipal systems to combine their fire and emergency medical services into one department. One participant acted as the county fire chief, the director of emergency medical services, and the director of emergency management for the county. Only one fire chief in the sample served in the sole capacity of fire chief.

| Professional Field | Position/Title | Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency Management | County Director of Emergency Management | (7) |

| Deputy/Assistant Director of Emergency Management | (3) | |

| Emergency Management Specialist | (1) | |

| Fire Services | County Fire Chiefs | (4) |

| Firefighters | (3) | |

| Emergency Medical Services | Director of Emergency Medical Services | (2) |

| Corrections | GDC Emergency Operations Official | (1) |

| State Prison Warden | (2) | |

| Public Works | County Public Works Representative | (1) |

| Local Government | County Commissioner | (1) |

| Forestry | Georgia Forestry Commission Official | (1) |

A grounded theory approach was used to analyze the qualitative data, wherein analysis and data collection occurred simultaneously. The data was coded and recoded in three stages using ATLAS.ti. First, I performed open coding of basic themes. Then, I examined the relationships between these themes and performed axial coding to connect similar themes together under larger concepts. Finally, I identified core concepts and processes and then performed selective coding of the data in relationship to these ideas (Charmaz 20019; Corbin and Strauss 199010).

Preliminary Findings

Prison Inmate Workers in Disasters

In the following discussion, I examine the deployment of inmate workers and inmate all-hazard firefighters during Hurricane Irma at the state level and the local community level.

Inmate Work Assignments in Emergencies and Disasters

The Georgia State Emergency Operations Center (EOC) and Inmate Workers

In a governor-declared disaster, Georgia law gives the state the authority to “utilize all available resources of the state government and of each political subdivision of the state as reasonably necessary to cope with the emergency or disaster” (O.C.G.A. 38-3-51 2010). According to the 2018 Georgia Emergency Operations Plan (EOP), inmate labor falls under the umbrella of a state resource. The state’s EOP details how the Georgia Department of Corrections is responsible for providing inmate work crews for debris removal, clearing public access areas, and providing meal service including mobile field kitchens (GEMA 201811). Interviews with participants reveal that inmates are responsible for additional tasks throughout the life cycle of disasters.

When Hurricane Irma hit, the persons and/or entities requesting inmate labor expands from local government agencies (public works, fire departments etc.) to include utilities companies requesting inmate workers to assist with clearing roadways to allow utilities workers to restore power to critical facilities (hospitals, prisons, etc.) and communities. In a later section I provide further details on the types of activities and work that inmate workers do during disasters, including work they did during Hurricane Irma.

Requests for various assistance by local and state governmental agency officials as well as utilities companies were made to the Georgia Emergency Management Agency (GEMA) at the state Emergency Operations Center (EOC). As with any major emergency or disaster event, the Georgia Department of Corrections sent its emergency operations manager and several other representatives to the state EOC to act as a liaison between the state and the GDC. In this role, the emergency operations manager manages requests from GEMA for GDC resources, including inmate workers, and coordinates those requests with the wardens, superintendents, and/or individual facility operations managers.

One of the corrections officials representing emergency operations and the Georgia Department of Corrections described how in a disaster prisons act as resource distribution centers where workers and equipment can be sourced from at a moment’s notice. Requests would come through to the state’s emergency operations center where officials from the GDC would facilitate the deployment of inmate workers by communicating directly with wardens and administrators of correctional facilities across the state.

When we get a request that comes in through GEMA, then they’ll come over… “hey we got one [request] over in this county, can you fulfill this request.” And I’m like yeah, we got a prison right next to it, we’ll send them [inmates]. And then at that point I’m coordinating with that warden or superintendent saying, hey I need one detail, two details [work crews] over here.

This finding is important because the state Emergency Operations Level is now identified as a conduit of organizing and deploying inmate labor.

Local Emergency Operations Centers

Across the state of Georgia, emergency management and response personnel were preparing for the impacts of Hurricane Irma days in advance. Locally, emergency management directors and fire chiefs take on the responsibility of emergency preparedness and response. In preparing for Hurricane Irma, communities in Georgia that were expecting more serious impacts from the storm used a more formalized structure to prepare and respond by activating their local emergency operations plan and setting up an emergency operations center (EOC). This would allow for coordination and communication in person with staff and leadership across local services and utilities.

Officials within fire and emergency management described having a representative from their local correctional facility present at their local EOC during Hurricane Irma as well as other previous disasters. As with the state operations center, having a correctional official present would allow emergency management to coordinate resources to the correctional facility or for the correctional facility to provide resources to the community, including inmate workers. One community’s emergency management agency director described how he required all of the correctional facilities to send representation whenever the EOC is activated.

Should we have an EOC activation, I require all the local prisons, all of em that’s in our area to provide a representative here at the EOC. Our EOC operation is, should we ever have a major disaster, I have a representative from each agency... So they would have an active part in it in here.

Another county’s fire chief who also served as the county’s director of emergency management and director of emergency medical services, described corrections officials, especially those overseeing inmate workers at a local inmate work camp, as active not only during the emergency response phase, but throughout the recovery as well.

Then we have a county employed prison warden for our work camp. So both the warden, the deputy warden, as well as the sheriff and his designees were all completely involved during all our main processes, our response as well as our recovery.

This finding reflects that for communities hosting correctional facilities, prison wardens or facility operations management personnel have an important role within emergency operations at the local level.

Contracted Inmate Work Crews

Some communities that already have inmates contracted out in the disaster may only have to redirect their assigned inmate workers to disaster-related labor. For example, one county’s fire department contracted with the local county correctional institute for an inmate “work detail” or team for day-to-day work at the fire department, including general maintenance of facilities and equipment.

Another Emergency Management Agency Director described how after extreme weather events, inmates could be directed to assist with debris cleanup and other emergency related tasks. The community would not have to request them unless there was a need for additional inmate workers.

Oh, it was a… we had a… I want to say it was a windstorm or something but it had to do with debris pickup and removal… But we already had the crew, it was not, we didn’t have to request it… We had a crew that worked with the road department that we contracted with the state to give us that crew every day, and so when they during that disaster operation time and we had going on they were picking doing debris work. But we wasn’t, we already had them we didn’t have to request them.

In addition to the changes in the type of work inmate workers may be doing in a disaster, there may be changes to the conditions and boundaries under which they work. For example, one prison warden described how he directed the facilities contracted workers to extend the days they typically would spend out in the community so that they could provide labor to assist with cleaning up debris and clear the roadways.

Well, I have six contract details for different local towns, within a 30 to an hour radius. So, typically we don’t go out on Fridays. But what we did, because there was so much debris in those areas, we allowed those details to go out and assist with debris pickup. You know, just trying to help them get back on track. Clear the road ways.

However, contracted work details may be working alongside additional inmate workers sent from the local prison or correctional facility. The same warden went on to describe how requests for inmate workers came in to the facility directly, and how inmate workers were also assigned to assist with the disaster.

Actually, they will call us first. Especially when trees are down because most of their resources is going to be dealed towards power lines. We’re[inmates] used more to clear roads for buses, ambulance, fire trucks, citizens. So, we’re used for that so we coordinate that and they will ask us how many inmates, how many vehicles, how many buses, trucks, bulldozers, everything. So, we give them a list of what we have and what sources that we have before them. And if they use us, we are on a 12-hour shifts. So, the inmates are on 12-hour shifts. So technically the first 12 will go out, if we’re doing 20, we’ll send 20 out for 12 hours, and then the other 20 will come and take up that shift, they’ll come back and sleep and the other 20 will go out. So, we’re just continuously for so many days just run a rotation from that point.

All-Hazard Inmate Firefighters

Interviews with corrections officials and local emergency services personnel revealed that if there is an indication of an impending emergency or disaster, both inmate all-hazard fire teams and other inmate workers will be alerted to prepare to be sent to disaster zones. The GDC official described how inmate firefighters are often the first to provide emergency response throughout the state. They are prepared not only to respond locally, but to be sent wherever they are needed.

They had their bags packed for deployments. And they’ve been critical, they’re kind of like our first response to disasters because they’re constantly ready to serve in the community with fire services and so they’re already ready to roll for the most part. And so when a disaster is coming through, those are some of the quickest crews and teams that gets out in that local community.

As requests come in, GEMA and GDC representatives will work to direct resources to areas most severely impacted. The proximity of the work location to individual correctional facilities influences the type and amount of resources provided by the GDC. If prisoners are deployed to a region outside their host facility, they might be housed overnight at another secure facility. In talking about both inmate workers and inmate all-hazard firefighters, the representative of the Georgia Department of Corrections described how the agency could send inmate workers, especially inmate firefighters, across the state as long as there is a nearby “secure facility” for the inmates to return to at night if they are deployed away from their host facility.

It’s hard to assess exactly which community’s going to be hit and impacted the hardest. But, what we try to do is concentrate resources there… I try to strategically look at locations of the prison knowing that at the end of that day they’ve[inmates] got to go back in to prison. They’re not sleeping at a hotel or in a tent. They’re having to go back to a secure facility. But, so we try to get what’s closest to them. But with fire services there’s so many of them. And if they have to, they can sleep at another prison for that night. So, they concentrate and we’ll deploy them you know from the North area down South if we need to.

Anything We Need: Inmate Workers in Emergencies and Disasters

In a disaster or emergency, both general inmate populations and inmate fire teams participate in a variety of preparedness, response, and recovery tasks. These contributions different types of labor in all phases of the disaster. When inmate workers are deployed or assigned to communities or to work on behalf of the state in the midst of a disaster, the immediacy of the need determines the type and level of assistance and work they are assigned to.

Inmate Work Crews

Preparedness Phase

In the preparedness phase, inmates are assigned work tasks ensuring that GDC facilities (and those within them) have all the necessary supplies they would need if an emergency or disaster does occur. The GDC food and farm services program is responsible for feeding on average 44,000 Georgia inmates every day. Through the program, more than 5,000 inmates across GDC state prisons to raise livestock and harvest crops in addition to operating canning plants, milk processing plants, meat processing plants, and vegetable processing facilities (GDC 2015). When a disaster approaches, these facilities and resources may be stored and stockpiled to provide food and other resources to staff as well as inmates. As Hurricane Irma approached, the GDC official described how the GDC would direct the Georgia Corrections Industries program, the for-profit corporation branch of the agency that employs inmate workers, to begin making such preparations:

We had our Georgia Corrections Industries which handles all our food and farm, they were stockpiling food at these facilities to go ahead and prep them up so in case you know your roads were shut off and they couldn’t get to them.

According to the GDC official, as communities prepared for the impacts of Hurricane Irma, inmate work details were also at work throughout communities cleaning and preparing shelter sights for evacuees. Local fire and emergency management officials described inmates as helping prepare for flooding by making and distributing sandbags.

Response Phase

After a disaster such as an extreme weather event like Hurricane Irma, one of the first tasks for emergency management is to clear roadways to allow first responders to reach those in need, to allow utility services to restore power and other services, and to allow additional evacuation of civilians. Across interviews, it became apparent that prisoners are an integral part of this vital task at both the state and local level during the initial response to disasters and Hurricane Irma was no exception. The GDC official noted that at the state level, inmate work details are included along with civilian state employees within plans to clear roadways throughout Georgia after a disaster to allow for emergency response to take place.

They’re[inmates] going to be clearing debris off the road. With Georgia we have main reentry routes going from inland to the coast, basically plans to cut our way back in from white line to white line of the road. So, we’re parts of those teams, it’s a multi-task force you could call it, with state patrol, department of transportation, forestry, corrections, DNR [Natural Resources]. And you know, power companies, ambulances, they’ve got these teams where their whole job is to cut from white line to white line, get it clear so emergency services can get back into those impacted areas and start saving lives.

Inmates clearing debris from roadways throughout communities was commonly described across interviews with corrections, fire, emergency medical, and emergency management personnel. This task is particularly important in the wake of a disaster such as a major storm. If trees and/or other debris are blocking roadways, emergency response is impeded, power cannot be restored, and the community may not be able to function or respond. One county’s fire chief who also acted as the director of emergency medical services and emergency management, described getting inmates out quickly to respond was a key lesson learned from previous disasters.

Yeah one thing during Matthew, I don’t feel like we utilized the correctional assets as well as we could have. That’s one thing we addressed during Irma. Immediately after Matthew the inmates for the most part they stayed in the prison itself except you had a very small amount that were allowed to go out and do things. After Irma, the forces were mobilized a lot faster, a lot quicker to where when the storm winds subsided below what we thought was safe, I mean they were out. Because our fire department and public works are responsible for opening roadways, so they were right there with them, so it went pretty well.

In addition to addressing the need to clear roadways, inmates may also be assigned to assist with search and rescue efforts as was noted by a participant who serves as a county fire chief and director of emergency management:

They[correctional officers] will bring out crews if needed for storm debris removal, for actually helping clear roadways if it’s bad enough that our actual [prison] fire team can’t do. Actually, if we need help with search and rescue, they [prison officials] will send out crews to assist with anything we need.”

Recovery

After a major disaster, debris cleanup efforts often last long into the recovery process. Interviewees often described inmates participating in debris cleanup in response phase, but at least one community described prisoners as participating in debris cleanup efforts months after the last major hurricane to hit before Irma, Hurricane Matthew, that impacted the region only a year before. This would likely be the case for many communities in the months following Hurricane Irma. One county’s fire chief and EMA director describes inmate workers as actively cleaning up debris in the community for months following Hurricane Matthew.

The biggest thing was the incredible amount of volume of vegetative debris that came down. We had crews [inmates] out for a couple of months moving debris.

Inmates were also described as being an integral part of the state’s recovery efforts, as they help rebuild critical infrastructure as part of the inmate mobile construction services unit. One GDC official described the inmate “mobile construction” unit where inmates travel throughout Georgia working on state construction projects.

We have a big section too that’s our engineering construction services section and those are inmates that some of them are on what’s called mobile construction where they go out and they might be helping rebuild a school out here or they may be doing some work in the prison or what not and those men and women have specialized skills and heavy equipment and so we’ll leverage them.

Mitigation

Inmate workers were not specifically described as a labor resource for “mitigation” by participants, however, it became clear that for Georgia communities—which might have faced a disaster in the past or are at risk of one in the future—use inmate labor to provide services that improve potential community response and deter disaster impacts. Inmates, for instance, routinely work with public works departments to keep drainage ways clear of flood-causing debris. They also provide regular maintenance for emergency response fleet vehicles, including ambulances and fire trucks. Inmates assist with testing of emergency response equipment and help with routine maintenance and upkeep, which allows emergency responders more time to train and prepare for emergencies.

“One of Us”: Inmate All-Hazard Fire Teams

As with general prisoner labor, inmate firefighters are involved during all phases of disaster. However the activities and work they do is often qualitatively different than that of general inmate workers. Inmate all-hazard firefighters provide services that require skill and expertise that developed and honed everyday as they provide fire and emergency services to communities across the state.

Preparedness

If a disaster or major emergency event is believed to be imminent. First responders prepare to respond to the needs of their communities and beyond. Inmate firefighters are no different, in that they prepare to respond to the needs of impacted communities as well as the state. If an emergency or disaster is imminent, inmate fire teams are placed on alert for activation and deployment. During Hurricane Irma, for instance, inmate firefighters were put on standby to assist with Georgia Search and Rescue (GSAR), an organization within GEMA. One participant, a GDC official, described how inmate firefighters would assist GSAR with searching for disaster victims and recovering bodies:

Another thing our fire services, they were on standby, and luckily was not called upon to do. They’ve got what’s called GSAR teams which is Georgia Search and Rescue teams, and they’re [inmate firefighters] a part of it, so they were on standby to be called in the South Georgia area to response in case you know searching for missing individuals, body recovery, and things such as that. So, they were on standby for that search and rescue type operation.

In preparing for a disaster, local emergency management officials and other emergency services officials (fire, EMS) coordinate with their local prison fire chief and/or their local facility warden to discuss and plan for what role the inmate firefighters will have in the response efforts. Within the communities they serve, inmate firefighters make up a significant portion of full-time emergency services. Emergency representatives often spoke of the enormous value of their service and contribution to emergency efforts.

Emergency services go out of their way to ensure there are no barriers preventing inmate firefighters from assisting throughout disasters. In preparation for Hurricane Irma one community’s fire chief and director of emergency management was so concerned that the storm would prevent the prison fire team from being able to respond, the prison fire chief and the prison fire team spent the night at the local civilian fire station along with the area’s civilian firefighters. This allowed for the prison crews to supplement the civilian firefighters during the response.

“They all came in and actually we had all double staffing at all of our stations which the fire chief came in here and um, he stayed here actually. And um, so he could operate his crew. And once the storm passed and the winds got to a manageable level, at that point we began deploying into teams to different areas to check for damage and clearing roadways.” -- County Fire Chief and EMA Director. (CF)

Response

Aside from their day-to-day services as firefighters responding to structure fires and other local emergencies, inmates were described as responding to tornados, floods, winter storms, storms and hurricanes. During the initial response phase of a disaster, inmate fire teams differ from inmate work details in the types of labor they participate in. When it becomes safe for first responders to go out into the community, inmate firefighters are often right alongside them, checking on citizens to make sure they are safe. One GDC state prison warden described inmates as being responsible for going door-to-door throughout the community, checking homes for victims and hazards within the home.

Now we have our mobile fire station, they look for people who’s deceased. So they’ll go through and clear a house, making sure nobody’s in there and they’ll mark the house. Anything dealing with emergencies they can handle. They’ve been trained to handle that, because our training class for our firemen can be from 1 year to 2 years of going through training.

However, because the state is responsible for the wellness and safety of prisoners, they are not typically allowed to respond until the immediate danger has passed. Prison fire teams were strongly relied upon, but local officials described how they were not allowed to respond until after the worst of the storm had passed. One fire chief and director of emergency management commented:

They [GDC] were not going to be allowing their fire department crew to respond until actually the storm had passed.

The all-female inmate fire department in Northern Georgia housed at Lee Arrendale State Prison, the only all-female fire department in the GDC and in the entire U.S., responded to impacted communities the night Hurricane Irma struck their region. One emergency manager described the women as responding until the conditions became too dangerous, prompting them to return to the prison.

Recovery and Mitigation

After a disaster, emergency responders like firefighters return to providing emergency response throughout their communities. Inmate all-hazard firefighters were described as mirroring this activity as they returned to training and providing emergency services within their fire stations when the initial response to Hurricane Irma ended.

Managing Perceptions of Inmate Workers and Inmate Firefighters in Disasters

Perceptions of Inmates as Dangerous

Inmate Workers

Even during times of status-quo, community members express concern over the dangers of inmate workers in their community. Community vulnerability and the increased presence of inmate workers in the wake of disasters may exacerbate this fear. Most participants recognized the public had some general fears about inmate workers in their communities, but generally brushed off concerns.

However, corrections officials noted it was necessary to have visible corrections officers overseeing inmate workers to allay community member fears. Other officials said it was important to be upfront with the public and ensure that they fully understand why the inmates are there, what security-risk level of inmate they are (low and/or medium), and what security measures are in place to prevent inmate misconduct and/or violence. A county’s fire chief and director of emergency services and emergency management noted that his local government, his departments included, makes a point to stay ahead of community questions:

We have stuff on our website; the city has stuff on their website, that tells people this is a detail [crew] that we have. So, when you see inmates working around, this is what they’re doing, so we try to stay ahead of that one. I think it’s important… we live in a very social media intensive world now, to where if somebody’s got a question, they’re going to answer it, and there’s no telling what answer’s going to be given on Facebook or whatever. So, we try to stay out ahead of all these things and educate people as to why, what it is. They’re very low security, they’ve been vetted, and this is what they’re doing. So, I think that’s incredibly important.

For participants that oversee inmate workers while out in the community, the primary concern working with inmates was not that they were dangerous, but that being in the public presented opportunity for them to break the rules or participate in misconduct. They trusted the Georgia Department of Corrections to properly “vet” the inmate workers.

One participant, a lieutenant firefighter for the county’s fire department described working daily with inmates, including during Hurricane Irma response. The only issues she described as having come up in the past were related to inmate workers breaking minor policies such as using department technology (phones, tablets) to access the internet.

They’re supposed to be trustee, they made it to that trustee status because they’ve shown they’re not a flight risk, they’re not a violence issue or risk. There’s no big issues with that. We’ve occasionally had a few that have taken advantage of the situation, they’ve been immediately pulled from our crews.

Another security concern was contraband. Having inmate workers in the public provides them opportunities to access items that they are not allowed (drugs, weapons, phones and other technology) to have in correctional facilities. With increased inmate presence in the community, there may be more opportunities than usual to contraband to inmates and back inside facilities.

Inmate Firefighters

Perceptions of inmate all-hazard firefighters varied. Representatives across the interview sample described pushback against the inmate firefighter program from the community and/or emergency responders. One urban county’s director of emergency management described state prisoners as hardened criminals, incapable of being rehabilitated and therefore incapable of having the qualities needed for being firefighters.

So the state prisoners, once again, they’re not DUIs, they’re not… they’re just not. These guys are for more or less, if they have to stay there for any longer than a couple of days before they bail out, they wouldn’t work well on our volunteer fire department… For the guys who don’t care if they’re on a road or not, and this is their third or fourth trip back in behind bars. And they know as soon as they get out they’re gonna go back to doing what they were doing…. Rehabilitation, eh…

Yet others described inmate firefighters as working closely with communities, building relationships, and contributing to ending the stigma of inmates as inherently dangerous and violent.

I think that helps to send a positive message of you know that not all these offenders are dangerous, or you know, some of them are gonna come back out and transition and be highly successful and stuff, so I think yeah some of that helps bridge that gap of our agency as well as stigmas that maybe some people have of inmate populations.

Participants that represented emergency services personnel that work closely with inmates for day-to-day emergency response and in times of disasters described pushback from community members as fading over time. One deputy director of emergency services and firefighter for their county described community members being afraid of inmate firefighters at first, but as the program continued and inmates provided needed help, this concern faded over time.

In the beginning there was some resistance, I guess… I mean you had you know, ‘I don’t want inmates in my house. I don’t want them….’ But as times has gone on, I think everybody’s truly seen the benefit in it… We don’t really have a lot anymore. It’s really worked out well. That’s a good thing.

On the other hand, communities may have no idea that their firefighters are in fact prison inmates. Several participants described their communities as having little to no idea that inmate firefighters were responding to local emergencies. One county fire chief described the local state prison as actively working to keep the community from knowing that the firefighters that just assisted them were in fact prison inmates:

The corrections facility does a phenomenal job even on structure fires, not they kind of want to hide what’s going on, but they place their vehicle to a standpoint where it can’t be clearly seen from everybody. Usually they’ll hide it behind a firetruck or something so that way… but… you’d be surprised. I’ve actually had homeowners and family members come up, shake their hand, thank them for what they’ve done and they have no clue, they have no clue where they came from.

This deception was described by participants as beneficial to both inmate firefighters and community members. Emergency services personnel did not want survivors to fear the inmate firefighters that may be working to rescue them or provide them necessary help. Others described it as important for the self-esteem of inmate firefighters to be able to feel like they weren’t prisoners, and just regular firefighters such as in the example above.

However, if community members are not aware that the firefighters are in fact inmates, any stigma they have towards inmates will not be impacted by the knowledge of inmates contributing to their community in such a meaningful way. Another consideration is that if the community is not aware of inmates acting as firefighters in their community, then community opinion cannot discourage them from using inmate workers.

Disasters Dangerous to Inmate Workers and Inmate Firefighters

Very little research has examined the impact of disaster labor on inmate health. In the American Correctional Association’s guidebook, “Strategic Planning for Correctional Emergencies,” author Dr. Robert Freeman recommends that in the wake of disasters, prisons create a special medical response team to assess whether or not corrections officers and inmate workers have been exposed to water-borne illnesses while working in communities impacted by flooding. He also states inmates should be provided with appropriate protective gear, “Inmates and staff engaged in recovery activities should be provided with appropriate gloves, clothing, and boots to prevent injury and contamination of sores or wounds by polluted water” (Freeman 199612). However, research has shown that corrections systems may not consistently provide adequate protective equipment to inmates while they work in hazardous conditions (Thompson 2012). For example, Louisiana prisoners assigned to work details assisting with cleanup to the BP oil spill were provided with “only flimsy coveralls and gloves as protection from extensive exposure to crude oil and chemical dispersants” (Thompson 2012:43).

Other risks to inmates working in disasters include electrocution (Freeman 1996). At minimum, inmate firefighters are subject to the same type of risks firefighters face while conducting community emergency response, prompting the Georgia Department of Corrections to require them to sign a waiver of liability when they agree to participate as firefighters (GDC 2011).

Participants were reluctant to acknowledge environmental hazard risks to inmate workers and firefighters while they worked in disasters. The only specific policy that any participant described that would keep inmates safe was the timing of their deployment. As previously discussed, participants across communities described their inmate workers as not being deployed until after the immediate storm had passed. Inmate firefighters were described as working until conditions became threatening, at which point they were pulled back to the correctional facilities or fire stations.

Other participants acknowledged the possibility that an inmate worker or inmate firefighter could be injured, but that any injuries would be treated in the same way that any other inmate work injuries would be. They trusted that the Georgia Department of Corrections would provide for the inmates. Under the eighth amendment to the U.S. constitution barring “cruel and unusual punishment” for prisoners, state corrections agencies must provide “reasonably adequate” medical care (Manville 200313).

One participant, a director of an urban county’s emergency management program, described how he and other emergency services officials had discussed with the county’s sheriff using inmates in the county’s jail as a source of labor, but had decided against it in consideration of the liability they could be subject to if an inmate were to be injured.

There’s also you have to think about the liability of those prisoners being hurt while they’re out doing something like that. There were still trees falling and things like that. You know… all of that was taken into account when we were discussing it and it was decided that it was best to just keep them in place.

Like other workers, the nature of the work and the disaster context present risks to the health and safety of inmates. Yet unlike civilian workers, they face serious repercussions if they refuse to work. As previously discussed, inmates in the United States do not have the constitutional right to refuse to work. Under the constitution’s 13th amendment they are legally considered slaves. In Georgia, as in other states, all inmates who able to, must work at the tasks they are assigned. Inmates work performance and compliance with work assignments is evaluated and recorded in each inmate’s personal file which is drawn upon when an offender is considered for parole opportunities. According to the GDC’s Inmate Handbook, if an inmate participates in any “refusal to work, work stoppage, or work slowdown” that inmate is in violation of policies “pertaining to the security and the orderly operation of the institution” and is subject to disciplinary actions (GDC n.d. p. 28).

Conclusion

In conclusion, inmate workers in Georgia are involved throughout the life cycle of disasters in communities throughout the state while inmate firefighters are depended upon primarily for emergency response operations. Inmates are viewed by officials across emergency management and emergency services as vital to the successful response of both the state’s disaster operations and local disaster operations. Those that work with and rely on inmate workers for disaster operations did not perceive inmates to be a substantial risk to the community, nor did they perceive the disaster situation to be particularly dangerous to inmates. Regardless, inmates do not have the right to refuse to work in the disaster context, even if they perceive there to be threats to their health and safety. In Georgia, as in other states, inmates who are deemed “able” must comply with the work assignments they are given by corrections officials and others they are assigned to work for.

Since many states across the U.S. use inmate labor during times of disaster, this study provides an understanding of prison labor deployment that can be compared with other states. As disasters increase in magnitude and frequency, future studies of community should recognize that prisoners are often used as disaster response and recovery resources and seek to better understand this role and its impact on incarcerated populations. Future research should also be informed by the perspectives of former and current prisoners have worked in the context of disasters and can provide a more detailed understanding of their experiences from their own points of view.

References

-

Munich Re. 2017. “Sharp rise in natural disaster losses – measures to enhance resilience can cushion losses” https://www.munichre.com/en/media-relations/publications/company-news/2017/2017-03-09-companynews/index.html ↩

-

NOAA. 2017. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/ ↩

-

McCullough, Jolie. 2017. “Two More Texas Prisons Evacuated as Hurricane Harvey flooding Continues,” The Texas Tribune, August 17th. ↩

-

Fonseca, Ryan. 2017. “Nearly a Quarter of Firefighters Working Southern California’s Big Fires are Inmates. Here’s How They’re Helping,” Los Angeles Daily News, December 8th. ↩

-

FEMA. 2018. Public Assistance Program and Policy Guide. Washington, D.C.: Federal Emergency Management Agency. Retrieved 1-22-19 (https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1525468328389-4a038bbef9081cd7dfe7538e7751aa9c/PAPPG_3.1_508_FINAL_5-4-2018.pdf). ↩

-

Thompson, Heather Ann. 2012. “The Prison Industrial Complex: A Growth Industry in a Shrinking Economy.” Pp. 38-47 in New Labor Forum: The Murphy Institute/City University of New York. ↩

-

Marshall, Catherine and Gretchen Rossman, eds. 2006. 6th ed. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↩

-

Weiss, Robert S. 1994. "Learning from Strangers.” New York, NY: The Free Press. ↩

-

Charmaz, K. 2001. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations. Waveland Press, Inc. ↩

-

Corbin, Juliet and Anselm Strauss. 1990. “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons and Evaluative Criteria.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 19(6): 418-427. ↩

-

GEMA. 2018. State of Georgia Emergency Operations Plan (GEOP). Atlanta: Georgia Emergency Management and Homeland Security Agency. ↩

-

Freeman, Robert. 1996. “Strategic Planning for Correctional Emergencies.” Lanham, MD: American Correctional Association. ↩

-

Manville, Dan. 2003. Federal Legal Standards for Prison Medical Care. Lake Worth, FL: Prison Legal News. ↩

Purdum, C. (2020). Hurricane Irma: Inmate workers and Inmate All-Hazard Firefighters in Disasters Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 274). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/hurricane-irma-inmate-workers-and-inmate-all-hazard-firefighters-in-disasters