Individual Responses to Severe Weather Media Messages

Publication Date: 2019

Abstract

This study sought to measure risk perception and behavioral intention of coastal counties in southern Alabama and northern Florida in areas affected by Hurricane Michael in October 2018. The research investigated how visual cues and media messages surrounding an impending hypothetical hurricane influenced risk perception and decision-making across three experimental conditions. Data were collected on 567 respondents within and near the path of Hurricane Michael. Analyses determined that the live video condition was most likely to motivate respondents to prepare for the storms, when compared with computer models and text-based warnings, while none of the models had significant influence on respondents’ likelihood to seek more information. Women, nonwhites, less educated and those in rural areas were more likely to engage in preparedness activities. In terms of information gathering about the event, female, white and less-educated respondents were more likely to be information seekers, along with those with a history of property damage during Hurricane Michael.

Introduction

Hurricane Michael gives us an opportunity to look at the risk information seeking and processing (RISP) model (Griffin et al., 19991), as it relates to severe weather events. The RISP model suggests that individuals may be more likely to seek and process information if such behavior helps minimize impending risk and supplies knowledge as an aid for decision-making (e.g., Chen & Chaiken, 19992; Eagly & Chaiken, 19933; Yang et al., 20144). In this context, the RISP model mainly examines the gap between what individuals know about a topic and what they need to know to make a decision (see Dunwoody & Griffin, 20155). Given that both of these frameworks involve perceived behavioral action, they fit well with an exploration of how media messages impact individual likelihood to take action during a hurricane.

Many studies on disaster preparedness and media messages emphasize either the function of word-of-mouth communication of weather information, or that of governmental and official announcements and advice (e.g., Linardi, 20166; Landwehr et al., 20167). Yet, little academic study specifically examines how individuals gather disaster information and learn about severe weather preparedness. In particular, academic investigations that examine the influence of media graphics on disaster preparedness and information seeking are rare.

This study attempts to address that gap by connecting literature on media messages and disaster preparedness for vulnerable populations. When examining severe weather, one media message may not be effective for all populations—particularly those who have significant impediments limiting their ability to take action, such as dependent children, limited access to childcare, and no proximate evacuation location. Media messages about impending disaster be interpreted differently, depending upon the population segment.

Therefore, the current study focuses on exploring the effectiveness of different media channels, in the context of a real-life disaster-simulated condition. For example, what effect does information presented in differing formats have on individual decision-making? With the swift development of media technology in the contemporary era, it is crucial to not only understand how audiences are interpreting media messages, but also how media receivers use that content to perceive disaster-related risk. Specifically, we examine various elements, such as community location, gender, race, and educational differences that could limit resources and make individuals be more vulnerable to severe weather. The specific hypotheses are below.

Hypotheses

H1: When a hurricane is imminent, individuals who view live video of a hurricane within a news story will be more likely to take action to prepare for severe weather than those who view computer-projected model or a text-based warning.

H2: Those residents who have suffered impacts from Hurricane Michael will be more likely to engage in information-seeking activities and preparedness activities than those who have not suffered previous impacts.

H3: When a hurricane is imminent, more socially vulnerable residents will be more likely to engage in preparedness activities, than those who are less socially vulnerable. Specifically,

H3a: Residents living in rural communities will be more likely to engage in preparedness actions than those living in urban areas.

H3b: Women will be more likely to engage in preparedness actions than men.

H3c: Minority residents will be more likely to engage in preparedness actions than white residents.

H3d: Less-educated residents will be more likely to engage in preparedness actions than more-educated residents.

H4: When a hurricane is imminent, more socially vulnerable residents will be more likely to engage in information-seeking activities, than those who are less socially vulnerable. Specifically,

H4a: Residents living in rural communities will be more likely to engage in information-seeking activities than those living in urban areas.

H4b: Women will be more likely to engage information-seeking activities than men.

H4c: Minority residents will be more likely to engage in information-seeking activities than white residents.

H4d. Less-educated residents will be more likely to engage information-seeking activities than more-educated residents.

Methods

Participants

Following institutional review and approval from the University of Alabama, participants were recruited from November 30 to December 15, 2018 for this research via a Qualtrics panel (i.e., a pool of U.S. adults who have volunteered in online survey research via the company). The company is able to recruit participations in targeted areas (in this case, southern Alabama and northern Florida) and provides them monetary compensation to participate in the study. The funds from this grant were used to contract with Qualtrics. Responses were anonymous and confidential, and no personal identifiers were linked to participants.

Study participants (N = 567), were provided with an online consent form before being directed to the study. Participants were drawn from residents within and near the path of Hurricane Michael: Mobile County (2016 population: 413,000) and Baldwin County (2016 population: 212,000) in Alabama; and in Florida, Escambia County, (2016 population: 313,000), Bay County (180,000), Santa Rosa County (166,000), Walton County (63,000), Leon County (285,000), Okaloosa County (197,000), and Wakulla County (31,586). The sample was 68 percent female participants, a median age of 55-64 years and 83.6 percent who identified as white. Roughly 50 percent of participants reported that they have lived in the area for more than nine years and 90 percent of participants reported that they had prior experience with severe weather or a natural disaster.

Study procedure

This study included an experiment embedded in a survey. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions, outlined below. Their general views on disaster preparedness and media use were first assessed through a survey. Then participants received one of three conditions, where a hypothetical Hurricane Farrah was three days from landfall near their location. Each of these stimuli was placed within a 140-second “breaking” news story about a storm, with a certified broadcast meteorologist providing the voiceover. The audio content was identical in these conditions, with the only difference being the graphic employed during the middle segment of the story. With no reporter on screen, participants viewed one of these conditions: 1) a “cone-of-uncertainty” hurricane tracking model; 2) a live-shot of hurricane-like storm conditions; 3) a text-only statement from the National Weather Service.

In all three conditions, the same text (a National Weather Service Hurricane Warning) was read by the off-screen broadcaster. After viewing the video, participants were asked how likely they would be to search for information and take precautionary actions, if the hypothetical scenario were real. At least 150 respondents received each condition. Regarding the manipulation check, 97.9 respondents correctly identified Farrah as the name of the storm. All but five respondents were able to correctly identify which computer simulation they received. Those five were eliminated from the data analysis.

Dependent variables

The two main dependent variables in this study were information seeking and preparedness activities. The information seeking variable was created from 11 items asking participants on a 1-7 scale how important they would find each of the following sources in obtaining information about a potential severe weather event: radio, television, newspaper, email, social media, general Internet sources, friends, face-to-face conversation with a stranger, telephone call, written notice (e.g., evacuation notice on their door) or an official policy (M = 57.55, SD = 16.05; α= .87). The preparedness activities variable was created from a seven-item index asking respondents on a 1-7 scale which actions they would be likely to conduct if an actual hurricane was imminent: prepare to leave the area, evacuate current location and go home, gather household members, pack supplies for travel, protect property, secure home and evacuate the area, or seek shelter immediately (M = 38.58, SD = 8.15; α= .78). This scale is adapted in part from that of Morss & colleagues’ (2016)8 examination of preparedness actions.

Independent Variables

Community size was determined by noting the two largest counties of Escambia and Leon, Florida and Mobile, Alabama, as urban (all populations of above 283,000,000). Thirty percent of the participants were from urban areas. The remaining six counties (where 70 percent of participants resided), included Baldwin, Alabama, and Bay, Santa Rosa, Walton, Okaloosa and Wakilla, Florida. These counties were categorized as rural. Community attachment was ascertained through a single item with 7 possible options that asked how long the participant lived in the area: less than 1 year, one year or up to 3 years, at least three years and no more than five years, at least five years and no more than seven years, at least seven and no more than nine years and more than nine years. For analysis, that variable was split at median, with 51.7 percent of respondents living in area more than nine years (see Sampson, 19889).

Participant demographics

Self-reported results indicated that 47.8 percent of respondents had a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education, while 39.7 percent were employed full-time. In addition, 46.2 percent of participants reported suffering damage to their home or property from Hurricane Michael. Participants were asked to self-report how frequently they search for information about severe weather in their area on a 1-7 scale (M = 5.72, SD = 1.42).

Results

To examine hypotheses, we employed the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 24, employing analysis of variance (ANOVA), analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA), as well as Scheffe post-hoc tests.

First, to examine the impact of the three stimuli on an individual’s likelihood to engage in information-seeking and preparedness activities, we conducted one-way ANOVAs examining the three stimuli on our dependent variables of information seeking and likelihood to engage in preparedness activities. No main effects [(F (2, 565) = 1.091 p < .34)] were found for information seeking, as means for all three conditions were: M computer model = 56.39; M live video = 58.89; M text-only: 57.76.

For analyses on preparedness activities, significant main effects were found [(F (2, 565) = 3.65, p < .05)], with differences among the three conditions. This result suggested that certain video conditions were more likely to engage viewers to take preparedness actions than others. To further investigate this finding, a Scheffe post-hoc test (p < .05) indicated that those who viewed the live shot were significantly more likely to take action (M = 40.09, SE = .59) than those that viewed the computer model (M = 37.88, SE = .62, p < .05). Results for those who saw the text warning alone (M = 38.18, SE = .53, p < .09) were not significantly different from the live shot or computer model conditions.

In this regard, the first hypothesis was supported, indicating that individuals who view live video of a hurricane within a news story will be more likely to take action to prepare for severe weather than those who view computer-projected model or a text-based warning.

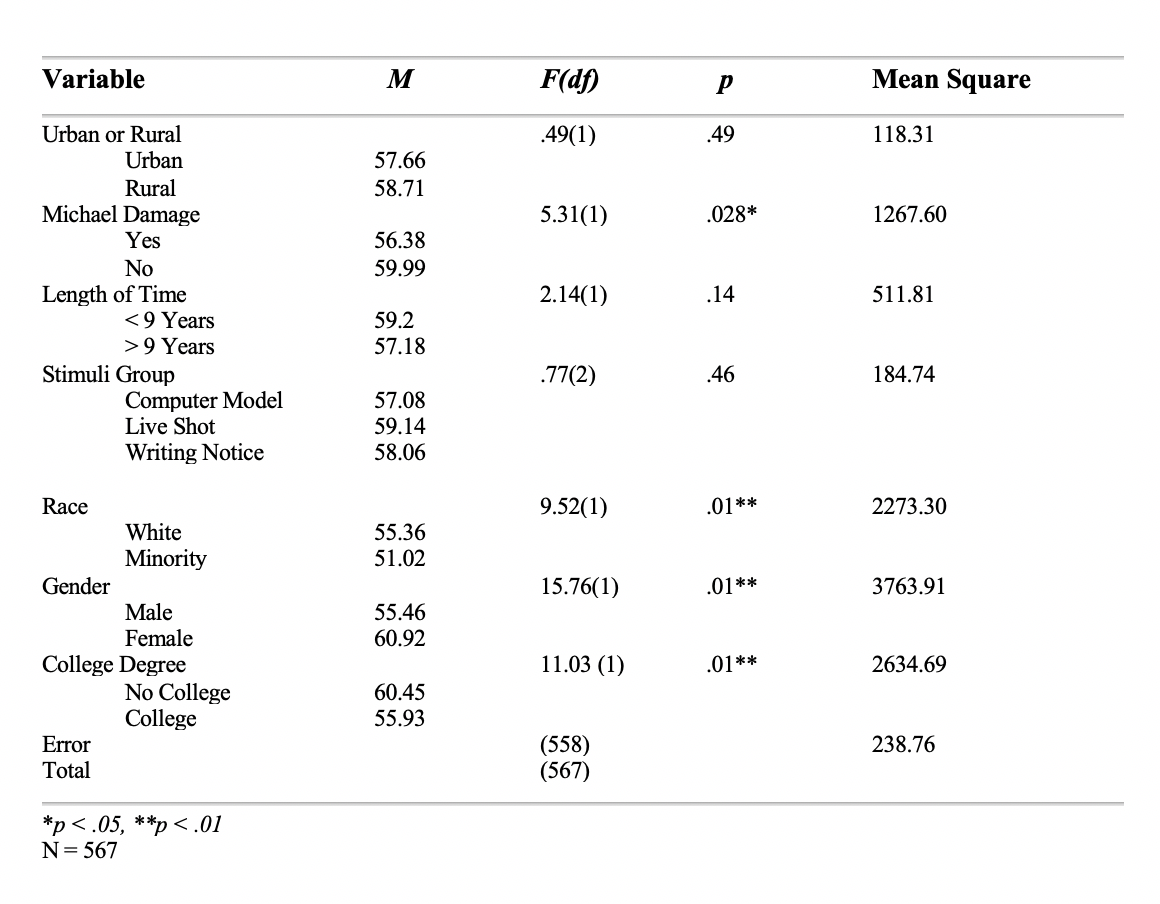

To test H2-H4, we conducted analyses on information-seeking activities (ANOVA) and preparedness activities (ANCOVA), which included the covariate of information search frequency. Following research on social vulnerabilities (e.g., Sommerfeldt, 201510), the following variables were included in the analysis as controls: race, gender, education, prior experience, and geographic area, along with the three stimuli. The second hypothesis posited that those who suffered damage from Hurricane Michael would be more likely to both engage in information-seeking activities and preparedness activities. Based on our the analyses (shown in both Tables 1 and 2), significant results were found for information-seeking activities, such that those who suffered damage were less likely to seek information (M = 56.38), compared to those who did not suffer damage (M = 59.99, p < .05). However, the relationship was in the opposite direction from what was predicted. No significant differences were found for those engaging in preparedness activities. Based on these results, H2 was not supported.

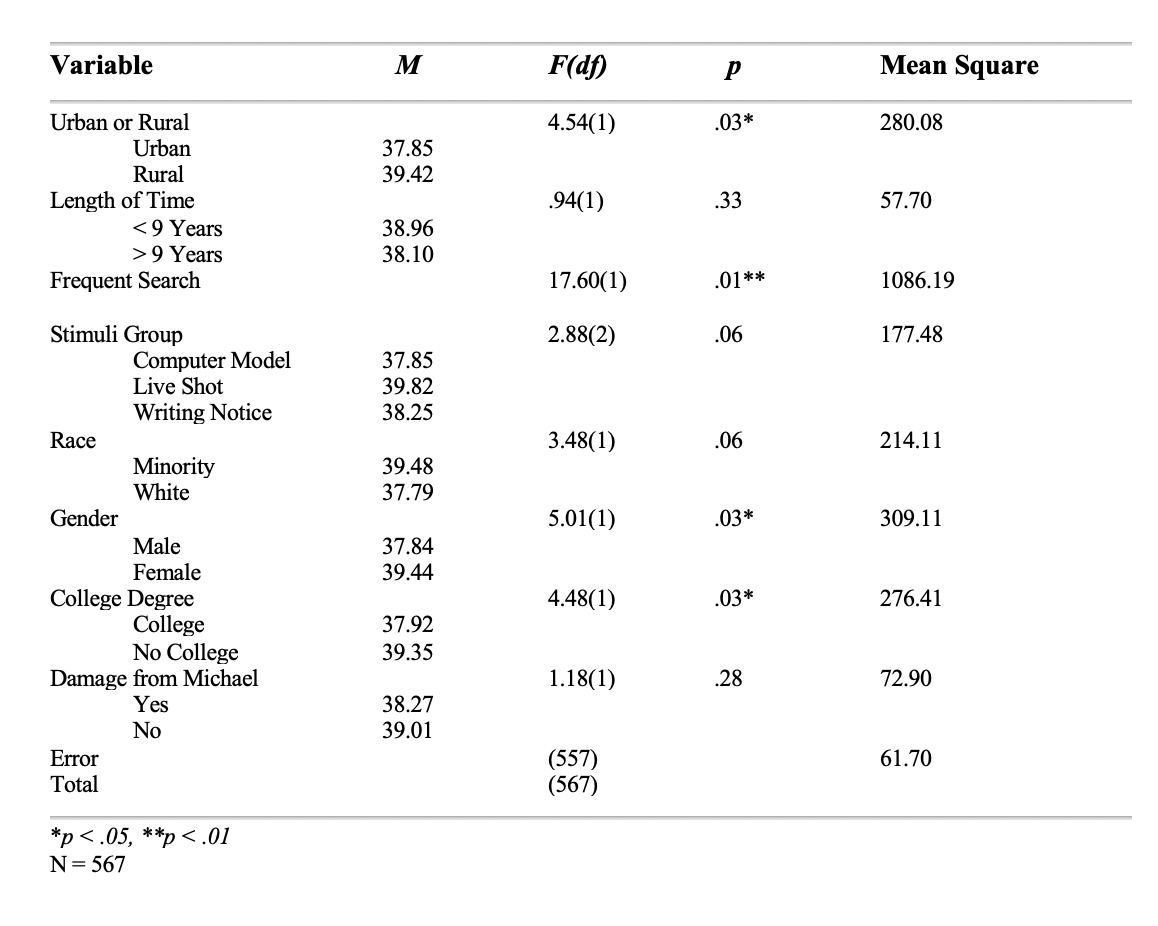

In terms of analyses on preparedness activities, we ran an ANCOVA controlling for those who frequently search for weather-related information, regardless of weather conditions. We employed the following variables: location (urban vs. rural), community attachment, race, gender, education, prior damage, and stimuli. We found main effects of gender [(F (1, 567) = 5.01, p < .05)], education [(F (1, 567) = 4.48, p < .05)], and location [(F (1, 567) = 4.54, p < .05)], such that women, less educated and rural participants (all considered more socially vulnerable) were more likely to engage in preparedness activities. No interactions were found. In this regard, H3a, b and d were supported, but the lack of significance of the race variable did not support H3c (see Table 1).

Table 1: ANCOVA for Likelihood to take action after viewing stimuli.

In terms of analyses on information-seeking activities, we ran an ANOVA and employed the following variables: location (urban vs. rural), community attachment, race, gender, education, prior damage, and stimuli. Main effects were found for race [(F (1, 558 = 9.52 p < .01)], gender [(F (1, 558 = 15.76 p < .01)], and education [(F (1, 558) = 11.03, p < .01)], such that minority participants, women and those who did not have a college degree were more likely to seek out information on the impending weather than women, white participants and those with a college degree, regardless of the stimuli. No interactions or significant differences in the stimuli conditions were found. No significant main effects were found for community attachment or location on hurricane-related information seeking. In this regard, the fourth hypothesis which argued that those who are more socially vulnerable will be more likely to seek out information compared to those who are less socially vulnerable, was partially supported. Specifically, H4a was not supported, but this analysis found support for H4b, c and d (see Table 2).

Table 2: ANOVA for Post-Test Information Search Hurricane.

The three video stimuli can be found here:

Computer Model: https://youtu.be/4-An0Nv8GG8

Live Video: https://youtu.be/wQ9DRBB92cs

Text-based warning: https://youtu.be/1h8ZwgPDDUg

Conclusions

This project measured individual responses to three types of media messages associated with a severe-weather disaster to determine the potential impact on preparedness activities. Our focus was to develop, compare and test specific messaging surrounding hurricanes and other severe weather for comprehension and interpretation. Three video messages were created and evaluated, using a professional broadcast meteorologist from Birmingham. The goal was to create media messages and gauge the effectiveness of those messages in motivating individuals to prepare for imminent severe weather. Ultimately, the purpose was to help with community resiliency when disaster strikes, minimizing human casualties and helping communities prepare for such events.

Perhaps the key message of this research is that not all individuals interpreted the messages in the same way. Various factors likely influence preparedness actions in response to severe weather. Disaster researchers recognize social vulnerability indices and talk about how unique populations respond differently to critical situations; however, media messages are generally uniform in their delivery to consumers. This study suggests that perhaps more nuanced or specialized messages may help residents determine what kinds of information they need to make decisions.

Specifically, these findings indicate that women, less-educated individuals, and those living in rural areas were more likely to take preparedness action than their counterparts; however, when it comes to seeking information, white, college-educated female respondents were more likely to want more sources of information. This suggests that information sufficiency is not uniform for all residents at the same time—some individuals want more information and some can make decisions with a single media message. Thus, uniformity in media messages may not be the appropriate way to stimulate action among residents, particularly when they have other concerns about their well-being.

Finally, this research suggests that differences exist in the influence of various types of media messages. After Michael, participants found the message which included the live shot to be more effective in engaging them to prepare for the storm when compared to the computer-cone model. However, that effect was eliminated when the full model was in place, suggesting that the different visual stimuli may not be as important as the overall message itself.

References

-

Griffin, R. J., Dunwoody, S., & Neuwirth, K. (1999). Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environmental Research, 80, S230-S245. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3940 ↩

-

Chen, S., and Chaiken, S. (1999). The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 73–96). New York, NY: Guilford. ↩

-

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ↩

-

Yang, Z. J., Aloe, A. M., & Feeley, T. H. (2014). Risk information seeking and processing model: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 64(1), 20-41. ↩

-

Dunwoody, S., and Griffin, R. J. (2015). Risk Information Seeking and Processing Model. The SAGE Handbook of Risk Communication, 102-116. doi:10.4135/9781483387918.n14 ↩

-

Linardi, S. (2016). Peer coordination and communication following disaster warnings: An experimental framework. Safety Science, 90, 24-32. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2016.03.017 ↩

-

Landwehr, P. M., Wei, W., Kowalchuck, M., & Carley, K. M. (2016). Using tweets to support disaster planning, warning and response. Safety Science, 90, 33-47. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2016.04.012 ↩

-

Morss, R. E., Demuth, J. L., Lazo, J. K., Dickinson, K., Lazrus, H., Morrow, B. H. (2016). Understanding public hurricane evacuation decisions and responses to forecast and warning messages. Weather Forecasting, 31, 395-417. doi: 10.1175/WAF-D-15-0066.1 ↩

-

Sampson, R. J. (1988). Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society: A multilevel systemic model. American Sociological Review, 53(5), 766-779. ↩

-

Sommerfeldt, E.J. (2015). "Disasters and Information Source Repertoires: Information Seeking and Information Sufficiency in Postearthquake Haiti." Journal of Applied Communication Research, 43, no. 1 (2015): 1-22. doi:10.1080/00909882.2014.982682. ↩

Armstrong, C. L. (2019). Individual Responses to Severe Weather Media Messages (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 294). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/individual-responses-to-severe-weather-media-messages