Information-Seeking in an Environmental Catastrophe: The Case of the Río Sonora Copper Sulfate Acid Spill

Publication Date: 2015

Abstract

On August 7, 2014 at the head of the Sonora River, 25 miles from the Arizona border, Mexico’s largest copper mine “Buenavista del Cobre” owned by Grupo Mexico S.A.B de CV, spilled approximately 40,000 cubic meters (10.6 million gallons) of Copper Sulfate into the Rio Sonora. The spill affected up to 272 km of the Sonora River and its northern tributaries (the arroyo las Tinajas and the River Bacanuchi). Mexico’s Minister of the Environment characterized the event as, “the worst natural disaster provoked by the mining industry in the modern history of Mexico.” The spill directly impacted over 24,000 individuals in 7 communities along the river. Over 300 wells and irrigation heads/tapping points were closed by the Ministry of Health. A team of researchers from CIAD and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro traveled to the region to conduct a RAPID assessment of conditions and how the event impacted the economic and psychological wellbeing of the region. This report is based on interviews with 31 individuals in 10 communities. The sample was purposeful in that where possible we Interviewed community leaders, small business owners, farmers, and wage laborers. The manner in which the event had been handled by the responsible government agencies caused a great deal of doubt and anxiety among residents as well as individuals living outside the region who were accustomed to purchasing products from the area or visiting relatives. This level of anxiety and the trauma it causes is clearly visible in our data on depression and traumatic stress. The physical impact of this event may be limited, but its social and psychological impact will continue for some time to come. People were most likely to trust friends rather than family when seeking information about the spill, although people said they trust few if any sources of information. This distrust of authorities and other sources of information also seems to impede people in their recovery from the trauma.

Background

On August 7, 2014 at the head of the Sonora River, 25 miles from the Arizona border, Mexico’s largest copper mine “Buenavista del Cobre” owned by Grupo Mexico S.A.B de CV, spilled approximately 40,000 cubic meters (10.6 million gallons) of Copper Sulfate into the Rio Sonora. Affected are up to18 km of Tinajas Creek, up to 64 km of the Bacanuchi River, up to 190 km of the Sonora River, and even part of the Molinito Dam that supplies water for the northern half of Sonora state’s capital city Hermosillo. Even before the spill, PROFEPA’s studies had found copper, arsenic, aluminum, cadmium, iron, manganese and lead over the levels indicated for normal health. The spill went unreported for several days until residents downstream informed the local press. Mexico’s Minister of the Environment characterized the event as, “the worst natural disaster provoked by the mining industry in the modern history of Mexico.” Mine officials say the breach was the result of heavy rains which caused the retaining dam to break. However, government officials dispute this claim stating that little rain had fallen in the period in question and that maintenance issues at the mine were already under investigation. The spill directly impacted over 24,000 individuals in 7 communities along the upper reaches of the river. Over 300 wells and irrigation heads/tapping points were closed by the Ministry of Health, according to PROFEPA. As a result individuals and groups from Sonora’s major cities took collections to provide water to communities along the river until they are told their drinking water is once again safe. Water trucks provided water for household use and most people bought purified water for cooking and drinking. The government provided some preventative health information and medicines to 12 villages along the river, totaling 1101 households, in order to prevent health problems from drinking the river water.

In addition to the health impact is the economic impact on the mine whose share prices has fallen significantly since the event. The social and economic impact to workers in the mine (laid off) and the 24,000 citizens along the river has been dramatic. Not only were they not able to drink water from their traditional sources, but they were not able to sell their produce as fear on the part of the general public has closed their markets. Some beef, milk, produce and other products had to be destroyed because of the lack of buyers. At the time of the writing of this report in Feubrary, 2015, most wells had reopened with affirmation by government that they were safe to use. Given the uncertainty of the situation and the lack of confidence the public has in the Government and Grupo Mexico, it is unlikely that confidence in the river and wells will return any time soon.

Methods

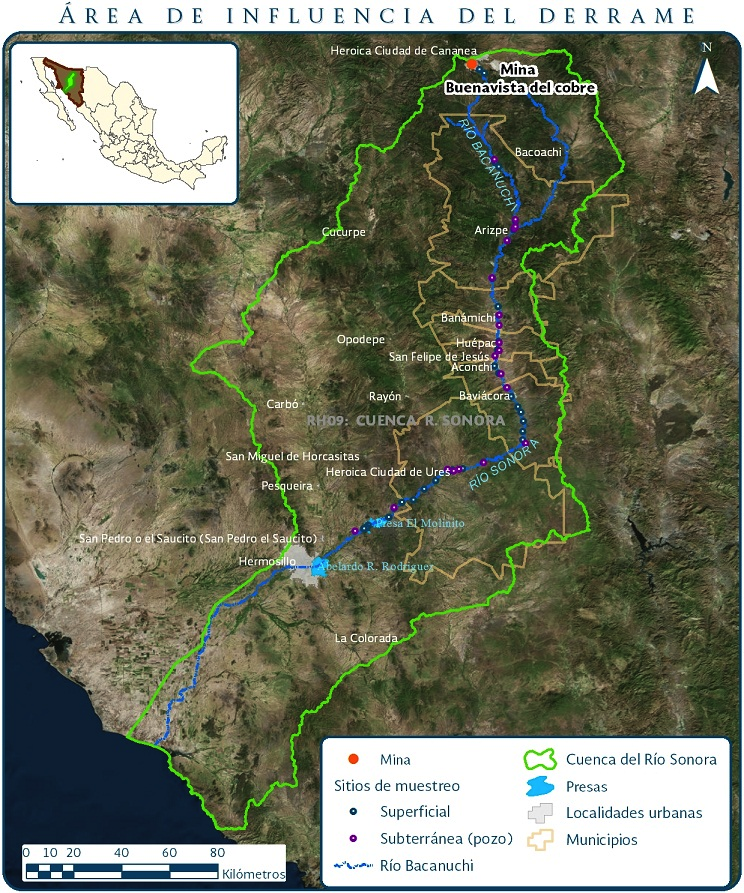

Approximately two months (October 17-20, 2014) after the discovery of the contamination of a tributary of the Sonora River, a team of researchers from CIAD and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro traveled to the region to conduct an RAPID assessment of conditions and how the event had impacted the economic and psychological wellbeing of the region. The goal of the assessment was to interview approximately 30 individuals including: community leaders, small business owners, farmers and wage workers. This report is based on interviews with 31 individuals in 10 communities (see Figure 1). The sample was purposeful in that we looked for community leaders, small business owners, farmers and wage laborers, where possible, in order to get an overall view of the impact, but at the same time opportunistic in that we did not turn down anyone who wished to speak with us about their experiences.

Figure 1: Area of the influence of the breach of the tailings pond

Source: http://www.semarnat.gob.mx/fideicomisoriosonora. Accessed 19 January 2015.

Typically, we interviewed people by going house to house in different parts of a village. The maximum number of houses per village was six and the minimum was one. In this report, we present the data as a first RAPID look at the entire region since the size of the sample does not permit us to break it down by community. Two of the communities in which we carried out interviews were not directly impacted by the coper sulfate spill from the Buena Vista Mine. However, it is fair to say that although they were not directly impacted the indirect impact was severe due to road blockages and trouble marketing their products. In one case for example a rancher from Bacoachi—a community on a tributary of the Rio Sonora not impacted by the spill—told us they were having trouble selling their yearling cattle because potential buyers from feedlots both in the United States and Mexico were nervous about purchasing cattle they might not be able to butcher in the future. Comments like this during our interviews plus reports from the press make it clear that the entire Rio Sonora watershed from Cananea to Hermosillo was affected—if not directly by chemical and heavy metal solution, then certainly by the social and economic stigma attached to the spill. This is not unlike what happened to the Alaskan fishing industry after the Exxon Valdez oil spill (Dyer 19931, 20022, 20093) the algae bloom in western Lake Erie, and Mad Cow scare in western Canada (Smart and Smart 20094) to name a few (see other examples in Jones and Murphy 2009).

The interview instrument was based on that used by the “International Disaster Response and Recovery Project” in the United States, Mexico and Ecuador (Norris et. al 20015, Jones et. al 20136). The instrument consists of a series of demographic questions, followed by questions pertaining to the impact of the event on individual and household daily activity as well as economic wellbeing. It asks about social networks and the information received through networks and includes a series of questions on physical and mental health that come from published scales (Leventhal et al. 19967; WHO 19978; Radloff 19749).

General Impact

Ethnographically it was hard to distinguish three events which occurred in close succession in the river basin and were being referenced or confounded by our respondents. The first was the spill from one of the waist ponds at the Buena Vista copper mine in Cananea. The second was hurricane Odile which caused severe flooding destroying crops along the banks of the Rio Sonora. The third event was the government stopping the use of the river and all wells within 500 meters on either side of the river for irrigation or for human or animal consumption. In the minds of many, the first two events were merged into a single phenomenon, and 90% of those we interviewed said they thought that fault lay with Group Mexico and, if not with the company, with the government for not keep vigil on the mine’s activities. As has been well documented for the cases of the Guatemalan Earthquake, the Exxon Valdeze spill, Hurricane Katrina, the Sri Lankan Tsunami, and others, post event activities by authorities and NGOs often result in a second disaster (Bates 198210, Button 201011, Gamburd 201412, Kroll-Smith and Couch 200913, Kroll-Smith and Baxter 201514, Simpson 201415). In this case the closing of access to water from wells and the river created a crisis of confidence not just along the river but in the entire region and the nation since people were not certain if products from the Rio Sonora Basin were safe to consume.

Demography

The team interviewed 31 individuals along the upper basin of the Rio Sonora. Sixteen (16) of the subjects were women and fifteen (15) were men. This ratio is close to that reported in the last census (CONAGUA 201216). The average age of the group was 50 years of age with the women being slightly younger at 49, and the men older at 53. The range of ages for women was 22 to 75, and for men from 28 to 72. As one would expect in this region of farmers and ranchers, we only found one person who was a pensioner as a result of an injury which did not allow him to work his fields any longer. Reflecting the age of adults and the flat demographic trend for the region since 1990 (CONAGUA 201216), households tend to be small with households averaging 2.3 individuals with a median and a mode of two people per household. That is to say, in most households there are two adults living alone. The median household had 1.1 children living at home. That figure is distorted by two households in the more urban areas with 4 and 3 minors at home while the modal number for the entire study was 0 children, and for the more rural areas impacted by the event was less than one child per household.

Education among those surveyed averaged 9.8 years or completion of secondary school and part of the first year of Preparatoria or High School. The average education for men was slightly higher than for women. Among both men and women, we encountered individuals who had completed university level education. However, only one of them, a geologist and hotelier, was able to continue his profession. The others had studied commerce or business administration, and the negative effects of the spill had closed any short term opportunities they might have to follow their profession.

Socio-Economic Factors

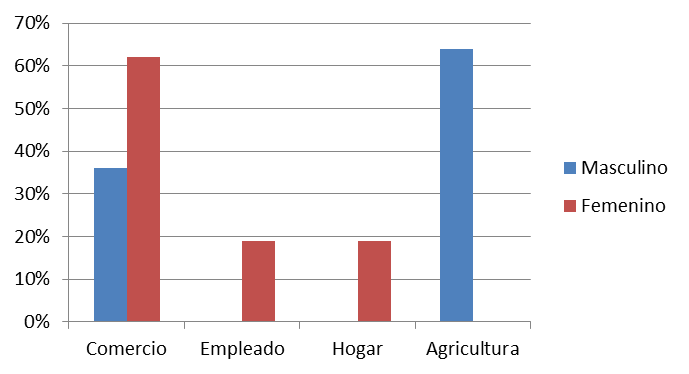

There was a clear division of work along gender lines among the group we interviewed. Sixty four percent of the men we talked to said they worked in Agriculture although 44% of that group said they worked in agricultural labor (see Figure 2). Only 36% of all men and 56% of those in agriculture privately owned the land they worked. The only other occupation of note reported by men was commerce. This ranged from owning and running a shop that made and sold tortillas to a hotelier. One man was a geologist who worked for one of the mining companies in the region. The majority of women we interviewed, 62%, worked in commerce. Again, this ranged from owning and running a parts store for cars and machinery to small stores. Nineteen percent indicated there were employees of one type or another and another 19% said they worked as homemakers. Three individuals we interviewed indicated the event and its aftermath had changed their employment or occupational activity. One woman who had worked in the home had to go to work as a waitress to help pay the bills after her husband lost his income and another woman had to close her business and was now living as a homemaker. One of the men who had worked as an agricultural laborer lost his job and was now un-employed as a result of the difficulty selling agricultural products from the region.

Figure 2: Employment sector after the event

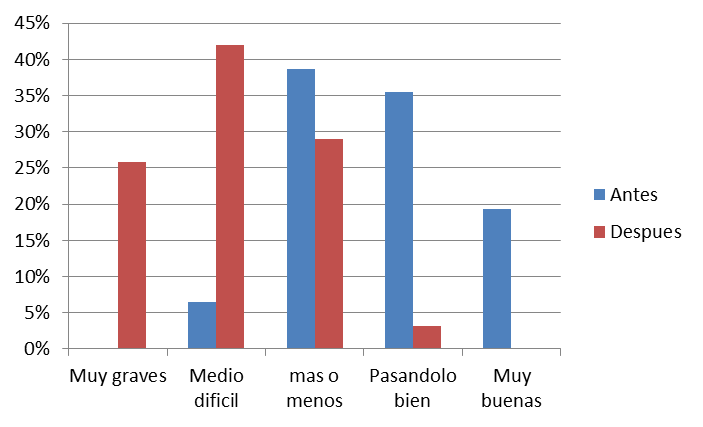

In Figure 3, we asked what the general condition of the community was before the event. Over ninety percent (93%) of our respondents indicated the top three choices on a 5 point Likert Scale and 55% indicated the top two options. There is a dramatic two point drop off after the event. At the time of these interviews, 68% indicated that conditions were very grave or difficult in their community and 70% said they had been gravely impacted. No one indicated that things were going well. Three individuals indicated no change, and the only individual who gave a positive response for the time after the event was the owner of a commercial establishment who was benefiting from the influx of water tanker drivers, but even he worried about what would happen when they left.

Figure 3: Perceived state of the community before (blue) and after (red) the breach in the tailings pond (terrible, very difficult, ok, pretty good, very good).

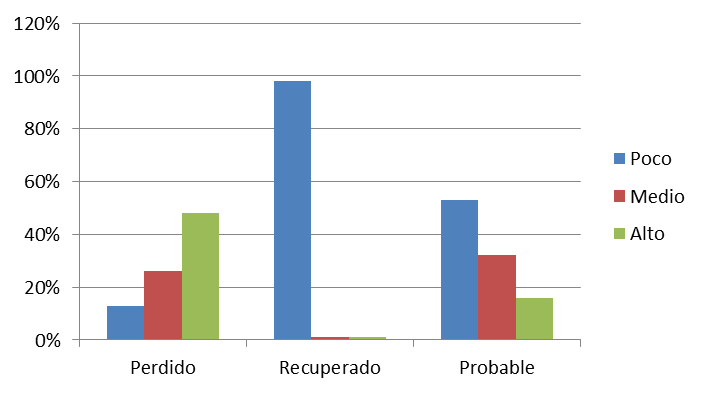

This general pessimism was mirrored in the response to the question of how much income had been lost and the prospects for recovery (Figure 4). Nearly half (48%) of our respondents indicated they had lost a great deal of their lively hood and only one individual said they had lost very little. They see little prospect for the future. Ninety eight percent (98%) indicated they had recovered little or nothing since the event and over half (53%) see little prospect of ever recovering what they had earned before the event.

Figure 4: Impact of event on income (perdido) ; subsequent recovery of income (recuperado), and future prospects for recovering income (probable).

It is difficult to say at this point if this pessimism is warranted but it is there.

There is virtual unanimity on who is responsible for the loss. Ninety percent (90%) of our respondents place the blame squarely on the shoulders of Group Mexico, and the others lay the blame on the government. When we asked who they felt confident would provide them trustworthy information about the event and its aftermath 52% said there was no source they could depend on. Thirty percent (30%) indicated mass media of one type or another. These data would indicate a lack of confidence in official sources of information. A fact born out when 100% of our respondents indicated that either the government or mass media sources were the least likely to provide accurate information on the event.

Seeking Information

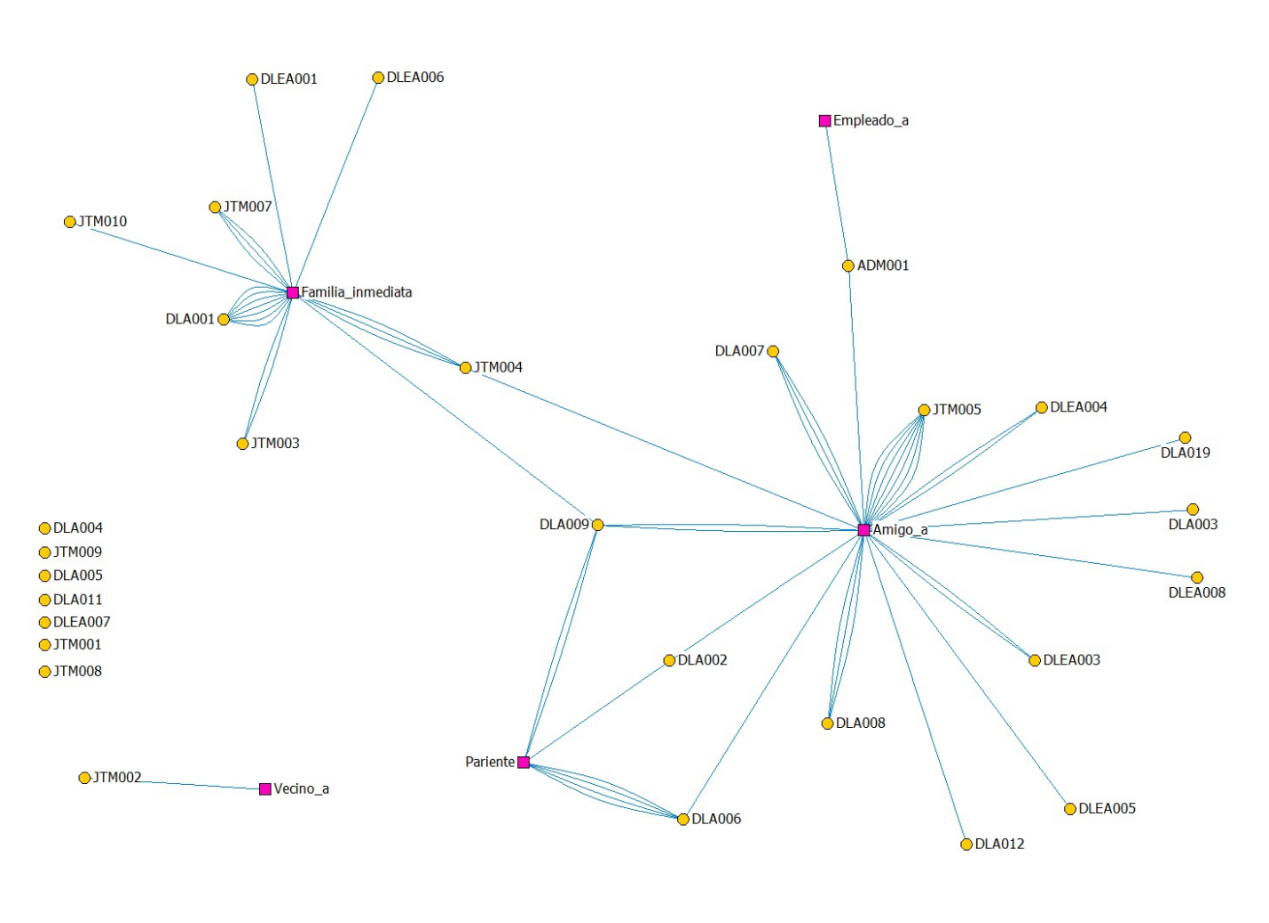

One of the goals of this RAPID study was to understand who people went to for information about the event. We asked each individual we interviewed to think of seven people with whom they have discussed the event. Our respondents focused on three types of individuals: Amigos (Friends), Parientes (Family), and Familia Inmediata (Close Family; see figure 5). Eighty six percent (86%) of those identified had also been impacted by the spill and its aftermath. The most common relationship was that of “amigo” or friend, by and large those who named friends did not name family members, as can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Two-mode information network indicating the connections that interviewees (yellow) have to different kinds of people (pink).

Only one of the characteristics of the relationships with others predicted sharing of useful information about the spill, its effects or what to do about it. Useful information about the spill was shared (p<.001, R=.473) and received (p<.001, R=.473) more by people who were emotionally close to the interviewee. Giving and receiving of useful information about the spill was not correlated with time known, relative wealth compared to interviewee, how often they saw one another, or whether they exchanged emotional or material support.

Over 60% of the respondents said they were very close to and on a daily basis had seen the person with whom they had consulted about the event. Over half had known the named individuals for 30 or more years. Ninety six percent (96%) of those mentioned were considered good sources of information about the event, and the interviewee agreed with the person named on what should be done about the event 82% of the time.

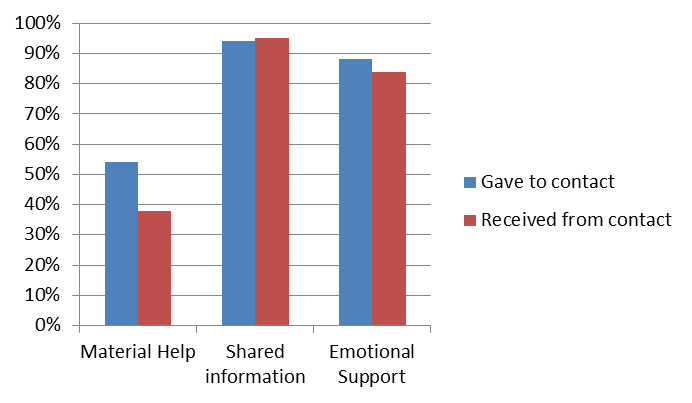

Figure 6: Level of support given and received, by type

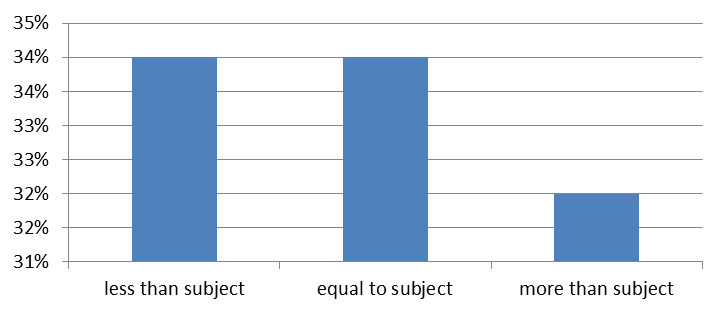

As is normal in the immediate aftermath of an extreme event (Fischer 199417, Glass 2005, Quarentelli 196018 and 200119), there was a good deal of reciprocity in the levels of information shared and emotional support between our subjects and their “alters” or the people they named (Figure 6). Over 90% shared information and well over 80% provided emotional support to each other with respect to the event. There was less exchange of material support over all with subjects claiming they received less than they gave. Perhaps this is due to the relative even economic distribution between subjects and their named alters (Figure 7). Subjects said that in 34% of the cases the person they discussed the event with was either of the same economic status or lower, and in 32% of the cases the individual had more resources than they did. The lower level of material support could be due to this lack of difference in resources to give.

Figure 7: Comparison of subject’s wealth level with wealth level of alter

Health

We asked a series of questions with respect to symptoms of physical health, depression and Post Traumatic Stress. For each set a questions we created a simple scale combining number of symptoms mentioned by the respondent and the severity of the symptom.

Physical symptoms:

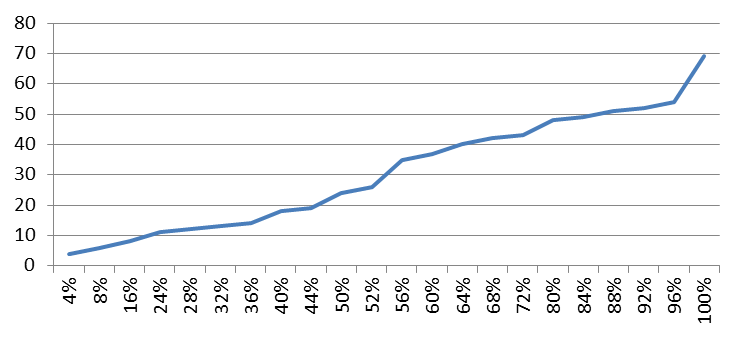

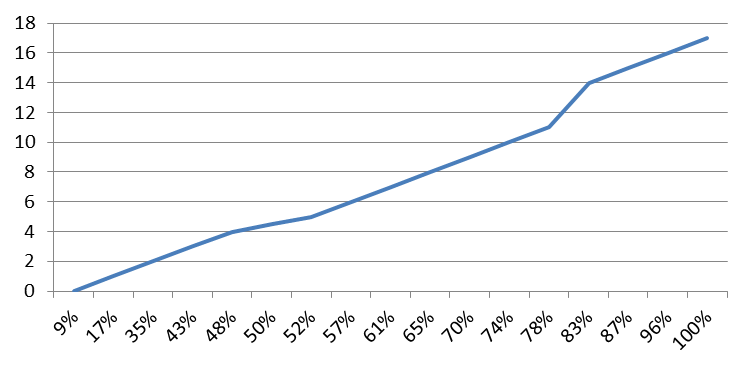

The scale for physical symptoms has a potential range of 0 to 170. As Figure 8 demonstrates the range for our respondents was 4 to 64 with a median value of 24. What is indicated is that while 50% had few symptoms of low intensity beyond the median, there is a sharp rise in symptoms and their severity.

The most common complaints had to do with muscular or skeletal aches and pains (Figure 8). The highest level of complaints, were with respect to shoulders, arms and hands. This could be a result of the fact that over half of our respondents were over the age of 50 and many had engaged in hard physical labor for most of their lives, and also had to carry water for months after the village water systems were turned off by the authorities. In the same way, the fact that over 50% of our respondents indicated they had cardiovascular and pulmonary issues could easily be associated with either their age or with the event. However, over 60% did report swelling of the feet and legs and itching of the skin and scalp.

Figure 8: Distribution of the physical health scale score per person

Depression:

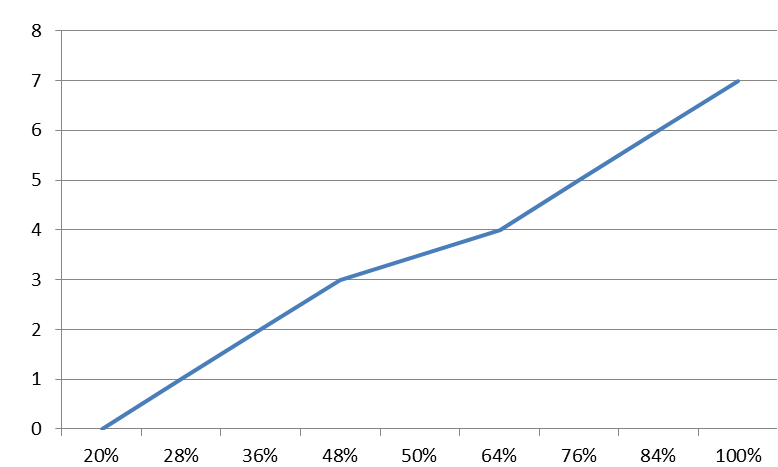

The depression symptoms scale has a range of 0 to 20. We found that 25% of our respondents indicated that in the past week they had suffered from over half of the indicated depression symptoms and 50% had five or more symptoms. Over 50% of our contacts indicated they felt depressed (50%), discouraged to the point where friends or family could not help (54%), sadness (57%), it required “fuerza” to carry out their normal activities (62%), and 50% had difficulty sleeping. In addition, another 40% said things that had not bothered them in the past bothered them now and caused problems with their families. While only 24% said they had uncontrolled incidents of crying, it was impressive in this country known for its machismo to hear a 63 year-old respected member of his community, head of the ejido association, talk about how he would break down crying at times thinking of what had happened to him, his family and his community.

Figure 9: Distribution of the number of depression symptoms per person

Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

It is clear from Figure 10 below, and we certainly felt it while conducting interviews, that our respondents suffered from some degree of traumatic stress. Over half indicated they suffered from 4 or more of the symptoms, and over 25% suffered from 5 or more of the 9 symptoms. The most common symptom was intrusion in in which thoughts about the event interfered with daily life and activities (88%). This data combines with 46% who said they had problems concentrating on normal activity. Sixty four (64%) said they had lost control and were more irritable than before the event and another 50% were angry with themselves over what hand happened and how they reacted to it. Forty two percent (42%) felt alone and isolated, a phenomenon that is common and often caused by people pulling away from individuals with symptoms. On a positive note and reflecting the resilience of this population, only 26% indicated there was no reason to think about the future.

Figure 10: Distribution of the number of posttraumatic stress symptoms per person

Conclusions from RAPID assesment

The purpose of this RAPID assessment was a preliminary look at the impact the release of toxins by the Buena Vista Copper mine into the upper portions of the Rio Sonora River Basin, and to explore how people shared information about the spill. What we found was a great deal of uncertainty as to what the future would bring for the region. Useful information about the spill was shared with almost perfect reciprocity between the interviewees and people they named as sharing information with them. People did not share or receive information based on wealth level, time knowing each other, or how often they seen one another, but only based on how close they felt to each of the people they named.

The manner in which the event had been handled by the responsible government agencies had caused a great deal of doubt and anxiety among residents as well as individuals living outside the region who were accustomed to purchasing products from the area or visiting relatives . As one couple told us, what bothered them most was that their daughter said she was not bringing their grandchildren to the farm again because of the contamination. They feared they would never see them again. This level of anxiety and the trauma it causes is clearly visible in our data on depression and traumatic stress. The physical impact of this event may be limited, but its social and psychological impact will continue for some time to come.

References

-

Dyer, Christopher L. 1993. Tradition Loss as Secondary Disaster: The Long-Term Cultural Impacts of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. Sociology Spectrum 13:65-88. ↩

-

Dyer, Christopher L. 2002. Punctuated Entropy as Culture-Induced Change: The Case of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. In Catastrophe & Culture: The Anthropology of disaster. Susanna M. Hoffman and Anthony Oliver-Smith, eds. Santa Fe, NM: SAR Press, Pp. 159-85. ↩

-

Dyer, Christopher L. 2009. From the Phoenix Effect to Punctuated Entropy: The culture of Response as a Unifying Paradigm of Disaster Mitigation and Recovery. In The Political Economy of Hazards and Disasters. Eric C. Jones and Arthur D. Murphy, eds. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press, Pp. 313-336. ↩

-

Smart, Alan and Josephine Smart 2009. Learning from Disaster? Mad Cows, Squatter Fires, and Temporality in Repeated Crises. In The Political Economy of Hazards and Disasters. Eric C. Jones and Arthur D. Murphy, eds. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press, Pp. 267-93. ↩

-

Norris, Fran H., J. Perilla, and A.D. Murphy. 2001. Postdisaster stress in the United States and Mexico: a cross-cultural test of the multicriterion conceptual model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 110(4), 553-63. ↩

-

Jones, Eric C., S.N. Gupta, SN, and A.D. Murphy 2011. Inequality, Social Support and Post-Disaster Mental Health in Mexico. Human Organization 70(1), 33-43. ↩

-

Leventhal, E., S. Hansell, M. Diefenbach, H. Leventhal, & D. Glass 1996. Health Psychology 15, 193-199 ↩

-

World Health Organization 1997. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Version 2.1. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. ↩

-

Radloff, L.S. 1977. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1,385-401. ↩

-

Bates, Fred 1982. Recovery, Change and Development: A Longitudinal Study of the 1976 Guatemalan Earthquake. New York: Bantam. ↩

-

Button, Gregory 2010. Disaster Culture: Knowledge and Uncertainty in the wake of Human and Environmental Catastrophe. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. ↩

-

Gamburd, Michele Ruth 2014. The Golden Wave: Culture and Politics after Sri Lanka’s Tsunami Disaster. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ↩

-

Kroll-Smith, Steve and Stephen R. Couch 2009. The Real Disaster is Above Ground, A Mine Fire and Social Conflict. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky. ↩

-

Kroll-Smith, Steve, Vern Baxter and Pamela Jenkins 2015 (forthcoming). Left to Chance, Hurricane Katrina and Stories from Two New Orleans Neighborhoods. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ↩

-

Simpson, Edward 2014. The Political Biography of an Earthquake: Aftermath and Amnesia in Guajarat, India. New York: Oxford University Press. ↩

-

CONAGUA. 2012. Atlas Digital del Agua México: Sistema Nacional de Información del Agua. URL [online] www.conagua.gob.mx, last accessed 19 January 2015. ↩ ↩

-

Fischer, Henry W. 1964. Response to disaster: Facts versus fiction and its perpetuation. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ↩

-

Quarantelli, E.L. 1960. Images of Withdrawal Behavior in Disasters: Some Basic Misconceptions. Social Problems 8, 68-79. ↩

-

Quarantelli, E.L. 2001. The sociology of panic. In International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences, Smelser N. Bates (ed.) New York: Pergamon Press, 11020-30. ↩

Murphy, A. (2015). Information-Seeking in an Environmental Catastrophe: The Case of the Rio Sonora Copper Sulfate Acid Spill (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 254). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/information-seeking-in-an-environmental-catastrophe-the-case-of-the-rio-sonora-copper-sulfate-acid-spill