Invisible Variables

Personal Security Among Vulnerable Populations During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, socially vulnerable populations faced unique challenges managing their safety, financial means, and autonomy in response to public health measures implemented to curb the spread of COVID-19. This project aimed at shedding light on the “invisible variables” that contributed to the personal security of socially vulnerable individuals during the pandemic. By invisibility, we mean the features of one’s life that are often assumed—correctly or incorrectly—within sociotechnical systems and are grounded in historical biases. The invisible variables we aimed to understand in this study are those that, from a sociotechnical systems perspective, were not accounted for in that system’s assumptions but, nevertheless, existed, particularly for individuals from intersectionally marginalized identities. We employed a novel framework incorporating principles of liberatory theories such as antiracism, queer theory, and Black feminism to qualitatively understand the impact that an individual’s safety, financial means, and autonomy had on overall personal security throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. We focused on six areas of daily life to understand how personal security was impacted: housing, income and finances, employment, healthcare, wellness, and family. We recruited participants who lived in the Greater Boston Metro Area for semi-structured interviews about their lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ongoing results show that municipalities and institutions can avert harm to socially vulnerable individuals’ overall wellbeing during disasters by setting medium- to long-term expectations for day-to-day requirements (e.g. how to get to work, scheduling for childcare, rules for accessing services, how long to expect remote work) as opposed to short and changeable ones, so that individuals can effectively manage their lives during periods of disruption.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been unprecedented in its magnitude, swiftness, and impact. It has spread illness, disability, and death around the globe; shut down global economies; and altered how humans live and interact with each other. National, state, and local governments in the United States enacted a number of policies to limit the spread of the SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, including social distancing, closure of non-essential businesses, shelter-in-place orders, curfews, and lockdowns. The COVID-19 pandemic set precedents locally and globally for disaster management—pandemic related and beyond. It is imperative to understand the effects of public health measures on socially vulnerable residents to understand this unique moment in modern history and to plan for future crises. While the coronavirus causing COVID-19 is unique, and the conditions the world adopted to slow its spread were tailored for the specific problem at hand, the unfolding reality of climate change and globalization means that another pandemic could strike soon. Public health officials could also be compelled to enact social distancing or lockdown measures in response to other disasters, such as wildfire smoke, chemical spills, heat waves, or high levels of air pollution. An updated understanding on how 21st Century hazards and their institutional responses affect vulnerable populations is paramount for policymakers as they try to navigate the realities of rapidly changing climate, economies, and societies.

Literature Review

Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Attempting to curb the spread of COVID-19 required the implementation of social distancing measures for months to years. The aim of social distancing measures generally is to minimize the number of contacts an average person has with other members of the public. Optimally, individuals were advised to limit close contact—defined as spending greater than 15 minutes with an individual, unmasked, and indoors—to only those in their household (Glass et al., 20061; Lewnard et al., 20202). As the pandemic stretched beyond the first few months, social distancing parameters and norms changed to accommodate the longevity of the crisis, and the need to balance public health and risk with other sectors of life and the economy. The need for social distancing was due to the contagious and fast-moving nature of the COVID-19 causing virus, which has a base rate of replication, commonly known as R0, of 2-2.5 and has seen exponential growth worldwide (Liu et al., 20203; Zhang et al., 20204). In the United States, social distancing was mandated at the state and local level, and included measures such as school cancellations, moving college courses online, prohibiting indoor dining at restaurants and bars, closing non-essential businesses, limiting gatherings to no more than 10 people, and “shelter-in-place” or “stay at home” orders or advisories (Henderson et al., 20205; Pueyo, 20206). Social distancing guidelines were phased—with “reopenings” and “reclosings”—common over the course of the pandemic as cases waxed and waned, and new variants of COVID-19 emerged. Initially, government and public health officials made quick decisions about social distancing—their guidance often changing on the hour—in part because COVID-19 was a lethal disease with the potential to overwhelm healthcare systems and cause societal breakdown (Pueyo, 2020). The assumption made by state and local leaders making these decisions is that the community and individuals are safer if they stay home, which was popularized by social media campaigns such as “#StayAtHome” (Stay Home Save Lives 2020), “#FlattenTheCurve” , or “#15DaysToSlowTheSpread” (The White House, 20207).

While appropriately implemented social-distancing measures have been shown to slow the spread of COVID-19 (Kissler et al., 20208) and remains a top priority of policymakers, these measures exacerbate other conflicts and issues in society (Stein, 20209; Greenstone et al., 202010). Though in lockdown, the everyday needs of individuals and societies do not come to a halt. The challenge for policymakers is to manage these conflicting societal needs (Short, 202011). In Italy, for example, a nationwide lockdown came with a moratorium on rent, mortgage, and debt payments (Dowd et al., 202012), and in Canada, the government passed a package to send its citizens $2,000 per month checks for the duration of mandated social distancing measures (Michael & San Juan, 202013).

In the United States, however, help for socially vulnerable individuals was not adequate. The government was often focused on the needs of large corporations, such as those in the airline and meat packing industries, and the stock market. Measures such as individual stimulus checks were watered down in favor of bailouts for companies. There were no nationwide moratoriums on debts or housing payments; landlords could still increase rent, creditor payments were still due, and, other than federal student loans, individuals were still responsible for paying their debts on time—with delinquencies impacting their credit scores long-term. As a result, local, institutional, and statewide leaders were forced to make rapid, drastic, and unprecedented decisions for the benefit of public health, and the American public was left with little to no safety net. The negative impacts of social distancing measures on American jobs and income was seen as a drawback of these measures (International Labour Organisation, 202014; Smith, 202015; Bauer, 202016; Rushe et al., 202017). Policy-makers were forced to choose between implementing social distancing mandates and making many of their constituents jobless and incomeless or foregoing social distancing measures and further overwhelming the healthcare system by adding fuel to the COVID-19 fire.

The implicit assumptions in some of these measures taken by federal government officials and many public health officials—though not all—were that Americans are safer at home, that Americans should be able to weather the storm financially, or that a shelter-in-place order is an easy sacrifice to make. However well-intended, these assumptions are based on a faulty premise—that Americans are universally secure. That is, that they live lives in relative safety, have means to fulfill their needs and obligations, and have the ability to optimize their decisions to meet desired outcomes. But this is not the case. Individuals experiencing low income from various employment sectors, for example, are likely to be financially insecure, and 78% of Americans have been shown to live paycheck-to-paycheck (Servon, 201718; Friedman, 201919). Americans who work in certain sectors that are nonessential may be faced with a sudden cutoff of income and healthcare benefits. Health care is tied to employment for a majority of Americans, so a lack of employment and income also translates to a lack of ability to obtain even lifesaving care (Riotta, 202020).

There are often invisible stressors on systems like housing, employment, and wellness. Just because someone has housing or healthcare “on paper” does not mean they are safe or secure. Indeed, preliminary reports have shown the rate of domestic violence increased during mandated social distancing (Foster et al., 202021). Variables like one’s safety at home are not quite counted or seen when measuring the impact of a decision on a population, and yet the effects of these variables are amplified during the rapidly unfolding COVID-19 crisis. To reduce harm to insecure populations, and to reduce strain on municipalities during the COVID-19 pandemic, an updated understanding of variables such as housing, employment, income, healthcare, and wellness needs to exist.

Social Vulnerability

This research is related to the concept of social vulnerability in natural disasters (Thomas et al., 200922). Social vulnerability is a framework positing that resilience and vulnerability to disasters is informed not just by the natural hazard itself, but by social dimensions (Fatemi et al., 201723; Singh et al., 201424; Alexander, 201225). These social dimensions can be specific features of an individual’s life—for example, being employed at a specific organization, or living in a certain place (Thomas et al., 2009). Additionally, they can be related to one’s identity and aspects of that identity—for example being a part of a marginalized religious group (Fatemi et al., 2017). Often, these identity-based aspects of vulnerability relate to features such as employment, or where one lives, so dimensions of social vulnerability are interconnected (Thomas et al., 2009).

There are broad indicators of social vulnerability that are considered more universal, poverty for example (Cutter et al., 201126; Thomas et al., 2009; Flanagan et al., 201127). Additionally, there are dimensions of social vulnerability that are considered specific to a given country, city, area, or situation (Fatemi et al., 2017). For instance, the degree to which sexuality makes one vulnerable depends on where one lives and whether that area has hospitable attitudes, norms, systems, and laws surrounding sexuality. The degree to which religion can be an aspect of social vulnerability can depend on geography as well, depending on site-specific or country-specific discrimination or oppression against certain religions (Fatemi et al., 2017).

Social vulnerability impacts how individuals are able to withstand and be resilient to disasters. Models of disaster response and social vulnerability include the risk hazard model, as well as the pressure and release model (Alexander, 2012; Burton et al., 201828). These models aim to theorize and framework how different aspects of vulnerability lead to disparate harms and burdens for individuals and groups during and after a natural disaster.

A key principle of social vulnerability is that disasters themselves are social. An event such as a hurricane or earthquake or a virus may be a natural event, but what makes an event a disaster is a combination of social factors, sociotechnical systems, cultural norms, and legal norms. This research aims to contribute to this literature by understanding how social vulnerability showed up in Greater Boston during the COVID-19 pandemic. This research ultimately will try to provide an updated and specific understanding of the ways that vulnerability was manifested in this scenario, in order to inform more effective and equitable policies, interventions, actions, and norms for the future.

Intersectionality and Critical Theory

As part of this research, we developed a qualitative framework to consider the impacts that natural disasters and hazards have on individuals (this framework is detailed in the Research Design section). This framework draws from liberatory theories and frameworks—such as intersectionality, queer theory, and critical theory more broadly—and intersects with themes embedded in social vulnerability research.

Intersectionality is a theory that aims to describe how different aspects of identity cause individuals to have a unique experience in the world (Crenshaw, 201729). For example, the lived experience of Black women is different than the lived experience of White women, because Black women experience both racism and sexism, as well as their intersection, misogynoir (Bailey, 202130). Aspects of identity that are often included under the framework of intersectionality include race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity (e.g. cisgender, transgender, nonbinary), religion, socioeconomic class, sexuality, disability, nationality, citizenship status, whether one was or is incarcerated, language spoken, body size, relationship status (e.g. marriage and partner privilege), and others (Crenshaw, 2017; Shields, 200831; Erevelles et al., 201032; Friedman et al., 201933; Lincoln, 201634; Yuval-Davis, 200735; Foster et al., 201536). Within these aspects of identity, there are often metrics used as proxies for indicating or measuring status—for example, the literature on colorism within communities of color (Jha, 201537), or using homeownership as a proxy for class (Trochmann, 202138). Some aspects of identity included in intersectionality are inherent from one’s birth, such as ethnicity, while others can change over time—religion or class, for instance.

Intersectionality is part of a body of work known as critical theory (Delgado et al., 202339; Sullivan, 200340). An important aspect of critical theory is the principle of lived experience and lived expertise (Delgado et al., 2023). This principle states that people who have a unique experience resulting from a marginalization, have better access, intelligence, and expertise about their own lives and lived experiences than those who do not. For example, the lived experience of a Black man would give him unique knowledge and expertise on how anti-Black racism works that others could miss, discredit, or misunderstand—no matter their credentials (Delgado et al., 2023). Similarly, the lived experience of a queer person in a queer relationship would give that person a unique knowledge and expertise of heteronormativity and queerphobia (Sullivan, 2003). One can take different aspects of one’s identity—for example, the aspects in the above paragraph on intersectionality—and extend the lived experience principle to each. For example, a disabled person uniquely understands the nuances and oppression of being disabled (Meekosha et al., 200941); an undocumented person uniquely understands the oppression of being undocumented (Osorio, 201842), etc.

The principle of lived experience ultimately aims to normalize respect and credibility for the experiences of those with marginalized identities (Delgado et al., 2023). Additionally, it implies that those living with marginalized identities know best how to navigate societal oppression and systems where they might experience that oppression. For example, for an undocumented person in the United States, the best way of getting medical care might be using emergency services, who are required to treat people as they show up and do not require appointments (Osorio, 2018). But a person who is a U.S. citizen and employed might have healthcare coverage through their job that makes using preventative care services a more appealing or better option for certain scenarios. Research and rhetoric that does not ground the principle of lived experience may assume that undocumented people using emergency services to access health care are dumb, ignorant, or making an illogical decision (Delgado et al., 2023). The principle of lived experience lends credibility, respect, and humanity to the complex decisions that those in different intersectional identities must make to navigate their lives. The principle of lived experience upholds autonomy and dignity around basic decision-making and life planning as important and a sign of an equitable and liberatory society. If individuals across identities are able to live their lives without societally imposed assimilation or segregation and fulfill their needs with autonomy and dignity—as opposed to getting their needs met in subversive or dangerous ways—that is a sign that a society or a particular system in society, for example, a healthcare system, is equitable.

This research aims to, ultimately, take an intersectional and critical theory-influenced approach to understanding the experiences of socially vulnerable individuals during the pandemic and to propose interventions, policy changes, and norms for managing natural disasters in general.

Research Design

Research Questions

The central purpose of this research project was to explore how the safety, means, and autonomy of socially vulnerable populations in Greater Boston were affected by the COVID-19 crisis. More specifically, we tried to understand how socially vulnerable individuals managed their housing, healthcare, and other economic needs during the time of state-mandated social distancing and pandemic mitigation measures—defined as any restriction on business function or occupancy, mask-wearing, mandated COVID-19 testing, or other measures not typically employed before the pandemic. Our three research questions were:

- How are individuals from economically vulnerable job sectors managing their individual safety, financial means, and autonomy during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How do COVID-19 pandemic norms, technologies, and policies impact the lives of economically vulnerable populations locally?

- What design features of pandemic norms, technologies, and policies contribute to potentially unique impacts on the lives and experiences of economically vulnerable populations?

In this report, the discussion of results will focus only on Research Question No. 1, particularly on how individuals managed their safety, means, and autonomy in six different sectors of life during the COVID-19 pandemic: their housing, employment, income and finances, health care, wellness, and family.

Research Plan

The research questions were addressed using the following three methods:

- The development of a conceptual framework to analyze information on the pandemic in Greater Boston.

- An analysis of policies and timelines that impacted the Greater Boston area during the COVID-19 pandemic, including timelines of social distancing, specific social distancing requirements, and businesses impacted, as well as where the policies were coming from (e.g. the state, the federal government, county or municipal governments, or other institutions).

- Semi-structured interviews with individuals living in Greater Boston and working in socially vulnerable job sectors during the pandemic.

Study Framework: Personal Security

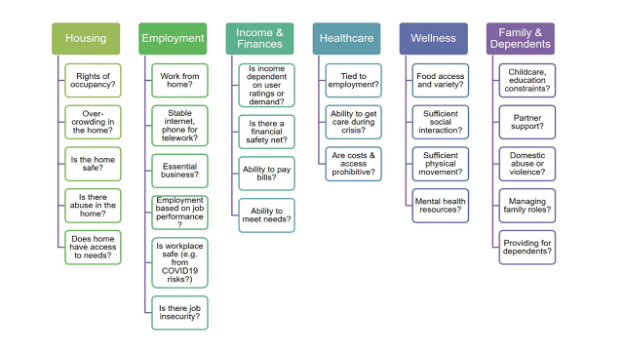

This study conceptualizes a framework to study the impact of natural disasters on individuals called Individual Security (see Figure 1). We conceptualize this as the qualitative interplay between safety, means, and autonomy. These concepts are grounded in intersectionality and the tenets of critical theory—particularly the principle of lived experience and expertise. We propose this framework as a means to understand impacts of natural disasters and to understand vulnerabilities in the 21st century.

We define safety as having a low risk of harm or abuse of all kinds. We define financial means as the ability to fulfill needs and obligations, potentially including those of dependents, as well. We conceptualize autonomy as the ability to choose how to best meet one’s needs and obligations (e.g., how to safely and reliably get to work, what kind of food to purchase, how to meet child care obligations, what to spend money on, etc.). The interaction between safety, means, and autonomy is considered qualitatively as an individual’s overall security—for example, do individuals make decisions sacrificing their safety to preserve financial means–or can all of these factors be balanced?

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework of Individual Security

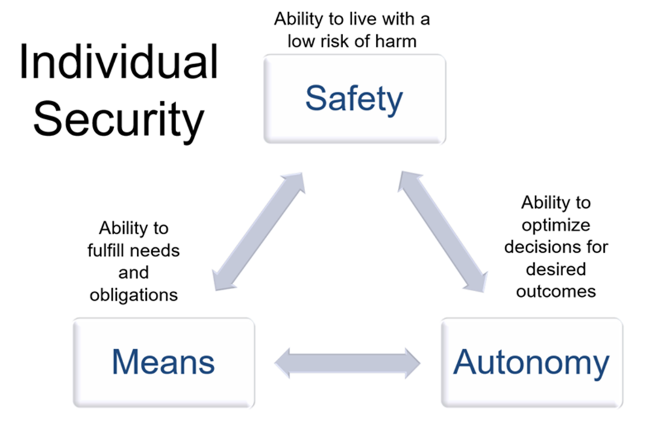

This study looks at six different spheres of life that shape Individual Security (see Figure 2). These spheres are drawn from the social determinants of health framework (World Health Organization, 201043) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Griggs et al., 201344). Interview questions in the study were focused on individual security in the areas of housing, employment, income and finances, health care, wellness, and family/dependents.

Figure 2. Six Spheres of Life Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic

Examples of the interplay between safety, means, and autonomy on the employment sector could be having an unsafe (e.g., OSHA non-compliant) workplace, harassment or assault in the workplace, lack of COVID-19 protections in the workplace, being unable to fulfill workplace tasks, being unable to use transportation effectively to get to the workplace.

Study Site Description

This study was sited in the Greater Boston area. It includes participants living in Middlesex County and Suffolk County in Massachusetts from February 2020 to December 2021. Greater Boston was one of the first pandemic “hot spots” in the United States, stemming from a Biogen conference that took place in a hotel in downtown Boston in late February. By March 17, 2020, the Greater Boston area was under a stay-at-home ordinance, and the universities and colleges in the area had displaced students from their university-managed housing and sent them away from campus until further notice.

Greater Boston led the nation in terms of setting up logistical support and policies to manage the pandemic and strove to emulate international norms, such as accepting COVID-19 as a serious public health threat, having robust community testing sites with less than 48-hour turnaround of results, and mask-wearing in public. In May 2020, the cities of Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville, joined the State of Massachusetts, in implementing a four-phase plan to manage social distancing, economic activity, and pandemic policies throughout the pandemic. This plan set guidelines and goals for testing capacity, testing availability, and hospital infrastructure. Additionally, it set guidelines based on COVID-19 test positivity rates for classifying businesses and institutions as safe to reopen, setting capacity restrictions for indoor and outdoor spaces, and adopting or lifting mask-wearing protocols.

The combination of Greater Boston’s features—being a pandemic hotspot, having a diverse population of people from different socioeconomic backgrounds and other identity-based backgrounds, and the aggressive stance that the local governments took on addressing the pandemic with social distancing tools—made the region an ideal case for this study.

Data, Methods, and Procedures

Participants in the study completed paid semi-structured interviews about their experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic. The interviews were coded and analyzed with a grounded theory and narrative approach, and the interviews are complemented with a policy analysis.

Individuals were recruited using social media and community organization outreach to apply to the study. Potential participants applied using a Google form which asked about their demographics (name, age range, race, ethnicity, gender, pronouns), their zip code during the pandemic, and their type of employment. Individuals accepted into the study were assigned an interviewer and point of contact on the research team. Informed consent was obtained using a signature form which requested participants consent to the interview itself, the recording of the interview, and whether quotes from the interview could be used with any of their identifying information.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted virtually over Zoom and lasted between 60-120 minutes. Questions focused on the experiences of the individual being interviewed during the pandemic in different spheres of their life (see Figure 2 for question topics). Participants could opt out of the interview at any time or refuse to answer any question. The interviews were transcribed using Zoom functionality and analyzed using a grounded theory approach. An analysis of local policies during the pandemic was also performed to contextualize information from the participant interviews.

Sampling and Participants

Data collection and analysis for the study is ongoing, and we would like to ultimately interview approximately 75 participants. As of this writing, 35 individuals have been recruited into the study. There are two inclusion criteria for acceptance. First, participants must have lived in Greater Boston for at least one month during the study period defined above. Greater Boston is defined as any zip code in Suffolk or Middlesex Counties. Secondly, participants must have fallen into one of the following categories: individuals with low income, undergraduate or graduate students, contract workers, workers who rely on tips, those on a fixed income, and those who are informally employed. The participants were selected without regard to race, ethnicity, gender, or age. Because sampling is ongoing, the potential for demographic generalization or broader conclusions cannot yet be determined.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by expedited IRB protocols by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (COUHES) on May 29, 2020.

Findings

Key preliminary findings in this study include insights specific to Greater Boston and those potentially generalizable to larger audiences about pandemic norms and policies and their impacts on socially vulnerable populations.

Policies and Timeline of COVID-19 Interventions in the Greater Boston Area

During the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, institutional and business leaders in the Greater Boston area made short-term decisions about daily operations at their offices, factories, universities, healthcare systems, childcare operations, and other enterprises. Their messaging often matched state, federal, or local government officials. Individuals living in Greater Boston acted as best they could under the assumption that the situation was a short-term (less than three months) emergency situation.

The City of Boston led the way in the United States for setting up longer-term phased reopening plans, wider testing access, and optimizing logistics for healthcare providers. From March 2020 through May 2020, Greater Boston was under a stay-at-home order or advisory; many business sectors were shut down entirely. During this stay-at-home order, the state of Massachusetts, as well as cities like Boston and Cambridge, developed phased plans for reopenings and reclosings, testing infrastructure, and hospital capacity. The phased plan for reopening was set in place by May 11. However, despite these plans and systems being in place by mid-May at the state and municipal level, institutions of employment and other services in Greater Boston—for example, universities, K-12 schools, and hospitals—delayed making longer-term decisions until July 2020 or later.

This institutional hesitancy to set longer-term expectations greatly impacted individuals’ ability to manage their lives during the pandemic and minimize harm to themselves and their loved ones. Delays in guidance from institutions—for example K-12 schools, colleges and universities, hospitals, and other employers—did not match municipal-level norms and policies around decision-making (e.g. parking, commuting, housing, school decisions, immigration). This delay and mismatch exacerbated existing inequities and created new instabilities. Individuals with financial means, safety nets, employment stability, household stability, and assets were better able to manage.

Institutional and municipal-level hesitancy in the first several months of the pandemic compounded instabilities, and in Greater Boston particularly (see Figure 3), impacted individuals occupying intersectionally marginalized positions in society (e.g., international residents and international students). A broad policy recommendation from this work is for cities and their institutions to create aligned long-term preparedness plans and be prepared to act quickly, decisively, and conservatively, so individuals can prepare realistically and make the best decisions for themselves and their dependents.

Figure 3. Individual Personal Security During the Early Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greater Boston

Interview Findings

In semi-structured interviews of 60-120 minutes, interviewees talked about the way they managed their lives in Greater Boston during the pandemic. Several themes emerged from these interviews. One theme was confusion and lack of clear direction—especially in the early months of the pandemic—as well as assimilationist assumptions in local policy and employer systems. A related finding was that inconveniences brought on by the pandemic—for example, needing to find alternate child care when school-sponsored programs shut down—were passed on to the individual, creating income and financial strain for that individual. Another theme was the creativity individuals tried to employ to live their lives with dignity during the pandemic while managing different risk factors. The interconnectedness of different areas of life was another theme—particularly the outsized roles of employment, institutions of employment, and, where applicable, child care on other areas such as housing, income, wellness, and health care. A final theme was the sacrifices that individuals made—either by choice or by direction, often from their employer—to fulfill some pandemic-derived requirement. Individuals often described sacrificing or changing key areas of their life, such as no longer commuting by subway, due to an employer mandate or risk profile management. Individuals overall managed their safety, means, and autonomy in complex, creative, and individualized ways—with the main constraints on these factors often coming directly from their employer.

The following subsections detail some examples and narratives from interviewees in the different spheres of life considered in this study—housing, employment, income and finances, health care, wellness, and family and dependents. Interviewees in the study did not all consent to direct quotes being used from their interviews, so for consistency, narratives and vignettes here are summarized and detailed without direct quotation.

Housing

During the pandemic, interviewees faced many challenges to their housing safety and autonomy, both as its own sphere of life and as it relates to other spheres considered in this study.

Many interviewees described instability in their housing for a variety of reasons. One big factor in this instability, though, was when housing was tied to an institution–university-based or government-subsidized housing, for instance. Individuals that lived in institutional housing faced challenges during the pandemic, such as their housing being changed or taken away from them at a moment’s notice. Some interviewees who were undergraduates or graduate students described being kicked out of their apartments with less than a week’s notice without financial compensation to store or move their items or buy a plane ticket home.

In interviews, individuals described the tedious and stressful process of applying for exceptions to these policies. One interviewee described her biological family as abusive and said she wanted to stay in her university housing. She had to apply multiple times to get an exemption to the move-out mandate. At first, the university system denied her, and when she appealed, it ultimately required her to provide proof that she would be in danger if she returned to her biological family’s home. The system did not have the ability to take her particular situation into account when evaluating whether she could stay in her housing.

Another interviewee described how she needed to stay in her university housing because she was an international student. The process of applying for an exemption to stay in her housing was tedious, and though she was ultimately granted this exemption, she had to move her belongings to different university housing units multiple times in the first few months of the pandemic. The reason given by the university for these moves was because the university was working out a plan to keep housing density and staffing as low as possible.

Another interviewee, a graduate student living in university-subsidized family housing described having a substantial rent increase of more than 20% passed on to him during the pandemic, as well as a requirement from the university to move his family to a different apartment within a different university-owned building. During this time, the university he was employed at was not giving raises, so the rent increase felt particularly unfair to him. This interviewee described how he had no choice but to do this because even with the rent increase, it was still cheaper than what his family could afford in a typical unsubsidized rent arrangement. He described how, ultimately, the university forcing him to move added a significant financial burden and, to him, seemed arbitrary. This policy was ostensibly a way for the university to staff less housing buildings during the pandemic, but it created a significant trauma and financial burden on top of the pandemic for his family.

Another theme interviewees described related to housing during the pandemic was the difficulty of making necessary upgrades, repairs, or adjustments to their homes. This was described by individuals in both institutional and standard housing. For example, one individual described how his landlord refused to fix a plumbing issue that caused a significant leak in his bathroom because of the pandemic and the associated financial strain his landlord was experiencing. One interviewee who lived in government-subsidized housing described how her air conditioning unit was broken for several months during 2020. Due to the contracts of her housing, the process of getting this air conditioner repaired had to go through her building’s manager, who was also a tenant in her building. She described how her building manager often made blatantly racist comments to her and others of her racial background (Asian), and how she believed the building manager ignored her requests to have the air conditioning unit repaired because of anti-Asian racism and bias, which had been exacerbated by the pandemic. The system that required this interviewee to go through the building manager to get this needed repair could not have anticipated the strain, impact, and gatekeeping that an informal relationship and racism might have on her. She described ultimately attempting to fix the air conditioning system herself, because summers in Greater Boston are often very hot and humid and to her it was important to have a working air conditioner.

Many interviewees described their housemate situation as being a very critical relationship during the pandemic. Interviewees living in university housing described how they had no autonomy or control over who their housemate was or whether they had one at all—universities would arbitrarily assign or relocate individuals based on pandemic concerns—and this lack of autonomy was stressful and confusing. Individuals also described how conflicts in risk tolerance and differences in what was deemed as acceptable levels of pandemic carefulness caused great stress. One interviewee described how he felt the autonomy of his living situation and health was compromised by having a roommate who, in his opinion, did not take COVID-19 seriously. This roommate routinely went out socially, associated with different groups of friends indoors and unmasked in close proximity, and did not mask in public settings despite the mask mandate in Greater Boston. This interviewee described how, absent the pandemic, he felt he’d get along with this roommate, but the fact that they saw this situation so differently caused great conflict in their household. In order to manage his preferred risk tolerance and avoid conflict with his roommate, this interviewee relied on a safety net he had—specifically, a romantic partner who had an unoccupied house in a different part of the state that he moved into. Having to move to avoid risk put a stress on his finances and autonomy, but he was unwilling to sacrifice his safety so he made the decision to move despite losing a lot of money and personal belongings in the process. This interviewee described his partner having the house as an option as a stroke of luck, because otherwise he would have had to continue to live in what he felt was a very unsafe situation.

Individuals described other impacts the pandemic had on their housing. For example, rent increases from landlords, matched with the financial and logistical difficulty of moving during the pandemic, caused much stress. Another example discussed by interviewees was the impact of the mask mandate. In Greater Boston, from April 2020 and onward, the mask mandate included a requirement to mask in shared corridors and common areas of apartment buildings, as well as outdoors on individual private balconies in apartment situations. Some individuals described this aspect of the mask mandate as welcome and a benefit to their safety, while other individuals described this as a perceived encroachment on their autonomy of having to wear a mask while outside on their own private balcony, or as they walked to get their mail down the hall of their building.

Interviewees described how their housing intersected with other spheres of their life and had cascading impacts. For example, one interviewee described how his apartment situation was inappropriate for remote work. He had a lot of difficulty getting his employer to help him obtain the necessary hardware and internet infrastructure that he needed to continue to do his job. Furthermore, his apartment was not set up to accommodate his work setup, so he was burdened by having to use a significant amount of space in his apartment to accommodate it.

A major insight that many interviewees commented on was their inability to make decisions about housing in a timely manner because of its relation to other factors, such as employment and the changing institutional and municipal policy actions and recommendations around remote work. One interviewee described how her housing location was inconvenient during the pandemic because her employer prohibited employees from taking the subway because of COVID-19 risk. As an in-person worker, the fact that she could not take the subway anymore was a significant financial and autonomous hurdle for her. Her 30-minute subway commute became an expensive car commute that was more than an hour long, and she had to buy a car and parking pass to keep doing her job and following the guidelines of her employer. Because her employer did not indicate how long the ban on public transportation to get to work would last, she felt she was unable to plan ahead—in her case, she would have liked to look for an apartment closer to her work, but her employer’s hesitancy to state longer-term recommendations and guidelines made her unsure if it would be worth the trouble and expense. Ultimately, she decided take on the financial burden of purchasing, driving, parking, and maintaining a car. The change in commute had detrimental impacts her changed commute had on her mental and physical health, as well. She said that she felt that she was unable to do what she wished and what would have worked best for her—to take the subway—without losing her job. Additionally, she felt unable to plan for medium- or longer term (6-12 months) expectations because of her employer’s hesitancy to set long-term expectations and insisting that all of the pandemic-imposed changes would be temporary, even when they stretched out for months.

Employment

During the pandemic, interviewees in our study described their employment as being a significant factor that impacted their life safety, means, and autonomy in many ways. These impacts stemmed from more obvious effects—such as employment being tied to one’s income and benefits—but in other pandemic-specific ways as well.

One pandemic-specific experience that multiple interviewees described was the stress, burden, and often financial cost of the frequently and suddenly shifting requirements and expectations for their jobs. These shifting expectations led to difficulty for interviewees to plan other spheres of their lives considered in this study—especially as it related to their housing, income and finances, and family and dependents. One example of shifting expectations was how long remote work would last. With employers hesitating to say that remote work might last longer than eight weeks, individuals struggled to plan for the reality of the pandemic’s multiple year long-haul.

One interviewee described the excruciating process he went through to apply for unemployment after being furloughed from his position working in a fitness center that was impacted by pandemic closures. Fitness centers in Greater Boston were closed through late Summer 2020 and went through multiple reopenings and reclosings as part of Greater Boston’s phased and flexible reopening plan. This particular interviewee wanted to be able to plan his finances long term and knew that he was about to be furloughed due to informal conversations he’d had with his boss. Since he knew that applying for unemployment benefits successfully would take time, he asked his employer to hasten his furlough so he could begin applying for unemployment as soon as possible. Ultimately, this request caused him to be denied unemployment because the system considered him to have quit his job voluntarily. While he did not want to quit his job, he described how he was trying to plan ahead for his financial security—but because he did not wait to be furloughed, he was penalized in the long run and was not able to receive unemployment benefits.

Interviewees often described their employer’s expectations that employees would pick up whatever slack or burden was asked of them, even when it led to financial strain such as having to purchase or use a car instead of taking public transportation, having to purchase masks when they were not readily available, or requiring mandatory participation in COVID-19 testing when the testing infrastructure wasn’t free, easily accessible, or covered by their employer. Similarly, they reported that having to immediately adjust to remote work and perform at the same level, at times without their employer providing internet materials, desks, and other remote-work infrastructure, was difficult. These expectations often negatively impacted many interviewee’s financial means, but they indicated they felt they had to comply or lose their jobs.

A common theme when discussing employment with interviewees was the perceived invasiveness and heavy-handedness of the expectations around employee conduct, behavior, and lives during the pandemic. For example, some employers prohibited their employees from leaving the state at times during the pandemic, and some employers prohibited their employees from taking public transportation to work. Some interviewees described how these expectations from different employers clashed with, for example, their housing and family situations. Interviewees described some employers taking a heavy-handed role in managing their lives—particularly universities and hospitals—to the point where individuals living with roommates or family that did not work at the same institution were considered a public health liability because of the testing and isolation standards had by different employers.

While many interviewees described these risk management practices to be difficult, burdensome, and seemingly inappropriate, this was not an opinion held universally by interviewees. Some interviewees found their employer’s risk-management practices to be helpful in managing stress and expectations during the uncertainty and conflicting information of the pandemic. These individuals described employer risk-management practices primarily as a way of keeping them safe. For example, one interviewee described how helpful it was to have his employer’s guidance to determine when it was okay to socialize with others and in what proximity, as well as when to vaccinate and get a vaccine booster and when to test for COVID-19. Some employers took financial, material, and logistical responsibility for routinely testing their employees for COVID-19.

Income and Finances

In the category of income and finances, interviewees often described unexpected expenses and burdens they took on because of COVID-19. Sometimes these expenses were directly related to COVID-19—for example, the requirement or need to take a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) COVID detection test. Many times, financial strain was indirectly related to other factors, such as the example above in which an interviewee incurred the expense of owning a car because she could not take the subway.

Individuals also said they had a did not have ability to plan financially beyond their immediate future during the pandemic and that this impacted related areas of life, such as their housing and childcare. A common feature of interviewees who were able to weather this instability was that they had some sort of safety net to rely on—whether that was a partner, a family member, an inheritance, or something else. For those who did not have access to these kinds of safety nets, interviewees often said they had to make the choice to do something they felt was unsafe to manage their financial means. Examples included taking an extra job driving Uber or Lyft, working at a grocery store, or getting an additional roommate.

Health Care

A major theme of this study in the area of health care was how interviewees described taking great lengths and risks to avoid the healthcare system because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Whether the specific reason was fear of exposure to COVID-19, not wanting to overburden the healthcare system, or being confused or unable to access care, this was a repeated experience that many interviewees described.

Often individuals described an unwillingness or an inability to access health care unless it was an emergency. One interviewee described injuring themselves while biking and trying to rehabilitate their injury without seeking formal medical care or diagnosis because they didn’t want to and know how to access non-emergency long-term care during the pandemic. Some individuals described a fear and avoidance of going to the doctor or to the hospital, even when it was needed, due to the risk of contracting COVID-19.

Many individuals described having a poor ability to plan for needed care that wasn’t considered an emergency. For instance, one interviewee postponed a necessary surgery for more than a year based on the pandemic outlook, but regretted not getting surgery in March or June 2020 when COVID-19 cases were much lower than they ended up being in 2021. Individuals said they were unable to make necessary milestone or recurring appointments, such as dental cleanings and pap smears, nor could they access necessary care that could be detrimental to their health if left unchecked, such as filling a cavity.

Some interviewees described inability, confusion, and stigma when trying to manage their sexual and reproductive health. One interviewee described the experience of being unsure of how to access preventative medications such as Plan B and PreP during the pandemic. This individual decided to forego taking these medications, although she needed them at certain times. In this case, she stated she felt stigma from the healthcare system when she had tried to access sexual and reproductive health services and she explained this stigma as related to an expectation that individuals shouldn’t be seeking sexual or romantic partners during a pandemic. This particular interviewee described the difficulties she experienced from being single and living alone with no family nearby, and she indicated that she felt such struggles were invisible and stigmatized during the pandemic by both society and the healthcare system. Ultimately the lack of understanding, empathy, and neutrality she experienced from healthcare professionals led her to make decisions that she felt she risked her safety and health in order to avoid shame and further stigmatization.

A positive thing some interviewees described was that, in some cases, they were able to access flexible telehealth policies through their healthcare coverage, especially when seeking mental health care.

Wellness

In the area of wellness, several themes emerged from interviews. One major theme was that individuals felt the need to exhibit strong self-reliance and resilience during the pandemic as opposed to relying on external systems of support for their wellness and mental health. One way that this theme manifested was in the the importance of some of routines. Many interviewees had routines around movement, such as biking or walking, and these routines were often described as very important to individuals’ wellness, even if it was brief. Movement routines described by interviewees were sometimes connected to other tasks. One interviewee described looking forward to his biking routine which helped him avoid public transportation (for safety), exercise and get outside, and go to an outdoor grocery market. These movement routines often were described as giving participants a sense of autonomy as they managed other aspects of their lives.

Individuals described routines for other wellness purposes, as well. For example connecting with others at a distance through video and phone calls, and through social events such as Zoom happy hours or DJ sets. These routines were often described as a way of trying to maintain social connections safely, or as a way of practicing joy—for example, by dancing during a Zoom DJ set—even though autonomy around social events was limited. Some of the events described helped interviewees stay connected with communities representing their identity or their special interests—for example, a queer community Zoom happy hour. Other routines described by interviewees centered around small joys and community with in-person housemates and family—playing a particular board game each night, doing a long-term craft together as a family or household, or other communal activities.

Another major wellness theme was the difficulty of accessing mental health care because the system was overburdened. Some individuals described cascading impacts on other spheres of life due because of this. For example, one interviewee described her son’s need to access routine mental health care and medication. During the pandemic, she was unable to continue accessing the appointments and medication her son needed because her employment and benefits changed, as well as long waitlists to get appointments with employer-covered mental health providers. This interviewee indicated that her son’s lack of access to this care ultimately led to him being kicked out of his after-school program. This had a cascading impact that inhibited the interviewee from working her regular shifts because she needed to care for him after school—which ultimately led to her being terminated. She described this entire scenario of events as stemming from the fact that her son could not get an appointment for months to see a psychiatrist and get his needed medications.

Some individuals who were able to access mental health care described the difficulty of relating to mental health providers if they were in a particularly unique situation, for example one that related to an aspect of their identity or positionality. One interviewee said she had great difficulty relating to her therapist. She was an immigrant to the United States who was unable to leave during the pandemic and faced a lot of stress due to anti-immigrant sentiment and the changing policies from the Trump administration. She felt that her therapist was unable to help her, give advice, or relate to the experience she was having. Many interviewees conveyed a sentiment of feeling alone in their struggles. For interviewees who were the heads of household and had children, they often described a particularly burdensome feeling of needing to hold things together for their children and keep things safe for them while not processing or managing their own needs and feelings due to the confusion and turmoil of the time.

Another theme that emerged from interviews was around the nuances of accessing food during the pandemic. For those living in employer-sponsored situations, their autonomy related to food was an issue of not being able to have the same options at dining halls or food services on campus. One interviewee described how, for a month during the pandemic, the university delivered food to her dorm apartment. She said she could not make any requests to accommodate her dietary restrictions and she had no choice in what food was delivered or its timing. Additionally, because she was living in university housing, she was not allowed during that month to leave to go to the grocery store, so her only option was to eat the food delivered. She said that she received inadequate nutrition during this time and had to dispose of some food items because of her dietary restrictions.

Many individuals described changing the way they obtained food during the pandemic, including walking or biking instead of using a rideshare application or taking public transportation or going to a less-convenient grocery store for pandemic-related reasons. One interviewee described how he didn’t feel safe going to his local grocery store because it was indoors and because he had a high COVID-19 risk profile, so he made a point of only going to outdoor markets like Haymarket in Boston or ordering grocery delivery.

Individuals also described the systems they developed to make food last since municipal and state recommendations instructed people leave their house as little as possible, as well as when some food items were regularly unavailable. Some interviewees discussed how they ate certain foods for days at a time, regardless of whether it was nutritionally recommended, enjoyable, or what they wanted.

A final major theme in this category was a sense of fear, sadness, and anxiety often conveyed by interviewees that resulted from the perception that they were putting their lives on hold for an indeterminate amount of time. One interviewee described how, despite being new to Boston at the time of the pandemic, he had decided to forego dating and making new friends until it was over because of safety concerns. He felt that this was the right choice for safety and public health, but the fact that he felt he needed to make this choice made him feel sad, and he expressed that he feared he was missing out on experiences in life he would never have again.

Family and Dependents

Individuals in this study described many facets and features of their family lives during the pandemic. One theme that emerged from interviews was a sense of chosen family or closeness because of what they were living through together. Interviewees described sometimes feeling like their roommates became their family. One interviewee described how his roommate became like his brother—they were both from outside of the United States and undocumented, and the time they spent together in their shared apartment made them grow close and develop an almost familial bond.

One evident theme during many interviews was the difficulty interviewees faced managing and having autonomy in family relationships that were not formally recognized by systems in society, such as unmarried romantic relationships, queer relationships, polyamorous relationships, and close relationships where individuals were not biologically related. Individuals described many aspects related to these types of relationships during the pandemic. One interviewee who was in a three-person queer relationship, described as a “throuple,” said he and his partners often felt anxiety at the thought of what would happen if one of the three of them became sick and hospitalized. The fact that their family was not recognized legally and the fact that polyamorous relationships are stigmatized in society and not legally recognized, meant that he wouldn’t be able to be at the hospital or have rights if one of his partners became ill.

As in many other aspects of life, the role of institutions and their pandemic risk-management policies played a role in many families as well. One interviewee discussed how her long-term partner was not allowed access into her university housing unit for months because he was not a member of her university community. She said this experience was extremely stressful because he was her only support system in the United States, as her family was in another country.

Another theme related to family expressed by interviewees was the sense of responsibility many felt towards their elderly and/or high-risk family members. Individuals said they didn’t see some family because of COVID-19 risk. This risk was especially prevalent in Greater Boston which had a higher density of disease prevalence compared to more rural and suburban areas. One interviewee described a situation in which her parents wanted her to come visit them and, while she felt like visiting them would have been beneficial for her wellness and mental health, she decided not to because she felt she would expose them to higher COVID-19 risk since she lived in Boston and the lived in a rural area with relatively lower risk. The situation was ultimately compounded by employer guidelines prohibiting her from leaving the state and not being clear on when she would be expected to return to in-person work. She felt unable to go visit her parents, or to live with them for a longer period of time, in case she’d need to return to in-person work quickly. She said this situation made her feel a great deal of uncertainty and sadness when she reflected on it and on when and whether she’d see her family again.

A final theme in this area of life that emerged from interviews was a sense of responsibility and confusion related to providing for children during the pandemic. Guidelines from Massachusetts, from employers, and from local municipalities around in-person education and child care often changed during the pandemic. Individuals who relied on subsidized school programs such as school lunches and after school care described the not knowing whether they’d have these programs during the pandemic or how to access them, and the stress of, for a time, not having the support of these programs at all.

Overall Themes and Nuances of Experiencing COVID-19 in Greater Boston

Within Greater Boston, some infrastructural features and cultures impacted individuals specifically during the pandemic: the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) commuting systems, institutions, and assimilationist assumptions.

The MBTA commuting system in Greater Boston shapes much of the city. Individuals are often incentivized to use the MBTA through employer-based subsidies and easier commuting logistics and disincentivized to use personal vehicles through lack of parking, as well as strict enforcement of parking policies. Additionally, the older design of Boston’s streets oftentimes leads to significant traffic and delays. During the pandemic, however, the airborne virus provided a huge deterrent to using public transportation and some institutions specifically discouraged or forbade the use of the MBTA. Suddenly, individuals who relied on the MBTA for their commute could no longer be certain they could go to work, make it home in time for child care, or do other daily tasks. Individuals who were able to weather this storm typically had some sort of social safety net, or flexibility in their work or childcare arrangements. Individuals without these benefits had to make an unfair and difficult choice to risk their health or their jobs riding the MBTA.

Institutions, such as Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT, and Northeastern University are a fixture of Greater Boston. In the early stages of the pandemic, institutions made the policy decisions that shaped individual lives in the long term. Institutions in general made their own decisions without coordination, and these decisions were not always on the same timeline as the city or as other institutions in Greater Boston. Institutional decision-making oftentimes left employees, students, and clients vulnerable to harm in sectors like housing, income, health care, and wellness as the pandemic continued on.

Decision-making in Greater Boston, particularly from institutions—often rested on a set of assimilationist assumptions about the individuals impacted—that people had safety nets, safe homes, and nuclear families to return to; the ability to navigate the U.S. legal systems such as immigration agencies; dual-income homes; sound mental and physical health; and the ability to socially distance. These assumptions especially harmed individuals from diverse backgrounds. As an example, queer and trans individuals, individuals who are not U.S. citizens, and individuals who faced significant physical and/or mental health concerns were often “glitches” in the policies set forth in the pandemic. Further analysis of these assumptions and biases is ongoing. We aim to connect and situate these findings to social vulnerability literature, as well as literature on intersectionality and sociotechnical systems.

Conclusions

This study aims to understand how pandemic norms and policies impacted individuals from socially vulnerable populations. A key insight from interviews is that local policy making and norm setting—from cities, municipalities, and institutions—has a significant impact on individual abilities to manage lives during the pandemic. These implications are important for policy making and framing in the context of long-term natural disasters. The major finding of our study this far is that policy makers, as well as institutional (employers, colleges and universities, healthcare providers, childcare providers, K-12 schools, etc) decision makers can help individuals manage the adverse impacts of disasters by quickly setting clear expectations that are aligned across institutions, municipalities, and states. Further, policy makers can ensure that individuals from a wide variety of backgrounds and family structures are centered in defining norms for support and management of ongoing disasters.

References

-

Glass, R. J., Glass, L. M., Beyeler, W. E., & Min, H. J. (2006). Targeted social distancing designs for pandemic influenza. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(11), 1671 –1681. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1211.060255 ↩

-

Lewnard, J. A., & Lo, N. C. (2020). Scientific and ethical basis for social-distancing interventions against COVID-19. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(6), 631-633. ↩

-

Liu, Y., Gayle, A. A., Wilder-Smith, A., & Rocklöv, J. (2020). The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa021 ↩

-

Zhang, S., Diao, M., Yu, W., Pei, L., Lin, Z., & Chen, D. (2020). Estimation of the reproductive number of novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the probable outbreak size on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: A data-driven analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 93, 201-204. https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(20)30091-6/fulltext ↩

-

Henderson, M., Kreiss-Tomkins, J., Kofman, I., & Rosen, J. (2020, March 16). Covid Act Now. covidactnow.org ↩

-

Pueyo, T. (2020, March 20). Coronavirus: Why you must act now. Medium. https://tomaspueyo.medium.com/coronavirus-act-today-or-people-will-die-f4d3d9cd99ca ↩

-

The White House. (2020, March 16). 15 days to slow the spread. https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/15-days-slow-spread/ ↩

-

Kissler, S., Tedijanto, C., Lipsitch, M., & Grad, Y. (2020, March 24). Social distancing strategies for curbing the COVID-19 epidemic. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.20041079 ↩

-

Stein, R. (2020). COVID‐19 and rationally layered social distancing. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 76(7). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13501 ↩

-

Greenstone, M., & Nigam, V. (2020). Does social distancing matter? University of Chicago Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2020-26. Available at https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/BFI_WP_202026.pdf ↩

-

Short, J. (2020). Biopolitical economies of the Covid-19 pandemic. TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies. ↩

-

Dowd, J. B., Andriano, L., Brazel, D. M., Rotondi, V., Block, P., Ding, X., Liu, Y., & Mills, M. C. (2020). Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(18), 9696-9698. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004911117 ↩

-

Michael, D., & San Juan, D. M. (2020). Responding to COVID-19 through Socialist(ic) measures: A preliminary review. SSRN. ↩

-

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2020, March 18). COVID-19 and world of work: impacts and responses. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_738753.pdf ↩

-

Smith, R. (2020). Independent contractors and COVID-19: Working without protections. New York: National Employment Law Project. https://www.nelp.org/publication/independent-contractors-covid-19-working-without-protections/ ↩

-

Bauer, J. (2020, March 16). Changes to unemployment insurance would help Oregon cope with COVID-19. Oregon Center for Public Policy. https://www.ocpp.org/2020/03/16/oregon-covid-19-unemployment-insurance/ ↩

-

Rushe, D., & Holpuch, A. (2020, March 26). Record 3.3m Americans file for unemployment as the US tries to contain Covid-19. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/mar/26/us-unemployment-rate-coronavirus-business ↩

-

Servon, L. (2017). The unbanking of America: How the new middle class survives. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ↩

-

Friedman, Z. (2019, January 11). 78% of workers live paycheck to paycheck. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/zackfriedman/2019/01/11/live-paycheck-to-paycheck-government-shutdown/#1760a9024f10 ↩

-

Riotta, C. (2020, March 27). Coronavirus: Teenage boy whose death was linked to COVID-19 turned away from urgent care for not having insurance. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/coronavirus-teenager-death-california-health-insurance-care-emergency-room-covid-19-a9429946.html ↩

-

Foster, H. & Fletcher, A. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on women and children experiencing domestic and family violence and frontline domestic and family violence services. Women’s Safety New South Wales. Investing in Women. https://investinginwomen.asia/knowledge/impact-covid-19-women-children-experiencing-domestic-family-violence-frontline-domestic-family-violence-services/ ↩

-

Thomas, D. S., Phillips, B. D., Fothergill, A., & Blinn-Pike, L. (2009). Social vulnerability to disasters. CRC Press. ↩

-

Fatemi, F., Ardalan, A., Aguirre, B., Mansouri, N., & Mohammadfam, I. (2017). Social vulnerability indicators in disasters: Findings from a systematic review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, 219-227. ↩

-

Singh, S. R., Eghdami, M. R., & Singh, S. (2014). The concept of social vulnerability: A review from disasters perspectives. International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies, 1(6), 71-82. ↩

-

Alexander, D. (2012). Models of social vulnerability to disasters. RCCS Annual Review, (4). https://doi.org/10.4000/rccsar.412 ↩

-

Cutter, S. L., Boruff, B. J., & Shirley, W. L. (2012). Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. In S. L Cutter (Ed.), Hazards vulnerability and environmental justice (pp. 143-160). Routledge. ↩

-

Flanagan, B. E., Gregory, E. W., Hallisey, E. J., Heitgerd, J. L., & Lewis, B. (2011). A social vulnerability index for disaster management. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1792 ↩

-

Burton, C., Rufat, S., & Tate, E. (2018). Social vulnerability: Conceptual foundations and geospatial modeling. In S. Fuchs & T. Thaler (Eds.), Vulnerability and resilience to natural hazards (pp. 53-81). Cambridge University Press. ↩

-

Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press. ↩

-

Bailey, M. (2021). Misogynoir transformed: Black women’s digital resistance. New York University Press. ↩

-

Shields, S. A. (2008). Gender: An intersectionality perspective. Sex roles, 59, 301-311. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11199-008-9501-8 ↩

-

Erevelles, N., & Minear, A. (2010). Unspeakable offenses: Untangling race and disability in discourses of intersectionality. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 4(2), 127-145. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2010.11 ↩

-

Friedman, M., Rice, C., & Rinaldi, J. (Eds.). (2019). Thickening fat: Fat bodies, intersectionality, and social justice. Routledge. ↩

-

Lincoln, K. D. (2016). Intersectionality: An approach to the study of gender, marriage, and health in contex (Vol. 6). In S. M. McHale, V. King, J Van Hook & A. Booth (Eds.), Gender and couple relationships (pp. 223-230). Springer Nature. ↩

-

Yuval‐Davis, N. (2007). Intersectionality, citizenship and contemporary politics of belonging. Critical review of international social and political philosophy, 10(4), 561-574. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230701660220 ↩

-

Foster, H., & Hagan, J. (2015). Punishment regimes and the multilevel effects of parental incarceration: Intergenerational, intersectional, and interinstitutional models of social inequality and systemic exclusion. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 135-158. ↩

-

Jha, M. (2015). The global beauty industry: Colorism, racism, and the national body. Routledge. ↩

-

Trochmann, M. (2021). Identities, intersectionality, and otherness: The social constructions of deservedness in American housing policy. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 43(1), 97-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1700456 ↩

-

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2023). Critical race theory: An introduction (Vol. 87). NYU Press. ↩

-

Sullivan, N. (2003). A critical introduction to queer theory. NYU Press. ↩

-

Meekosha, H., & Shuttleworth, R. (2009). What's so ‘critical’ about critical disability studies? Australian Journal of Human Rights, 15(1), 47-75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1323238X.2009.11910861 ↩

-

Osorio, S. L. (2016). Border stories: Using critical race and Latino critical theories to understand the experiences of Latino/a children. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(1), 92-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1195351 ↩

-

World Health Organization. (2010, July 13). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852 ↩

-

Griggs, D., Stafford-Smith, M., Gaffney, O., Rockström, J., Öhman, M. C., Shyamsundar, P., Steffen, W., Glaser, G., Kanie, N., & Noble, I. (2013). Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature, 495(7441), 305-307. https://doi.org/10.1038/495305a ↩

Turner, K.M., Acuff, K., Reid, J., Goel, T., Gibson, E., & Wood, D. (2023). Invisible Variables: Personal Security Among Vulnerable Populations During the COVID-19 Pandemic (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 343). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/invisible-variables