Land Use Adaptations to Wildfire in Unincorporated Communities in Colorado

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

The increasing occurrence of devastating wildfires in the United States is causing concern about effective risk management. By 2021, more than 63,661 U.S. communities faced wildfire risk, but only 30% had protective plans. Wildfire risk and inadequate preparedness pose a potential disaster for numerous communities in the wildland-urban interface. Existing wildfire management practices prioritize mitigation actions, such as fire suppression and fuel reduction, over adaptive land use planning. Moreover, property-scale measures such as special building codes are more popular than community-scale measures such as buyouts, re-zoning, or land readjustment. The inadequate attention given to land use wildfire adaptation, especially on a community scale, may be influenced by diverse socioeconomic, cultural, and institutional factors that remain largely unexplored. This study investigates wildfire adaptation strategies, particularly land use planning, that are currently employed in unincorporated communities, using the state of Colorado and Boulder County as case studies. Data collection involved reviewing 20 community wildfire protection plans and 63 hazard mitigation plans to identify wildfire adaptation and land use planning-related actions. Additionally, 14 key informants were interviewed to understand the challenges of pursuing community-scale land use adaptations to wildfire. The study uses descriptive statistics and thematic analysis to understand how various factors impact the perception and acceptance of community-scale land-use strategies for wildfire adaptation. The findings highlight gaps in current planning and policy approaches, urging a broader conversation on integrating land use planning with mitigation efforts to improve wildfire management practices.

Introduction

Wildfires are becoming more frequent in the United States, posing substantial threats to communities, ecosystems, and infrastructure (Thomas et al., 20171; Weber & Yadav, 20202). In recent years, the frequency, intensity, and impacts of wildfires have intensified, exacerbated by climate change and urban expansion into wildland areas. As the world tackles the increasing challenges of wildfires, effective wildfire mitigation strategies have become necessary to safeguard lives, protect property, and preserve the environment (Koksal et al., 20193; Liu et al., 20154).

Addressing the challenges of reducing wildfire losses is a comprehensive strategy that spans all U.S. government levels. Federal fire policy attempts to achieve this goal by creating resilient landscapes and vegetation, implementing effective and efficient suppression measures, and promoting fire-adapted communities capable of withstanding wildfires, therefore minimizing loss of life and property (U.S. Departments of Interior and Agriculture, 20145). On the other hand, research has shown that land use planning can be considered a vital and proactive strategy to reduce fire risk and enhance community resilience using wildfire adaptation approaches. (Brzuszek et al., 20106; Headwaters Economics, 20167; Muller & Schulte, 20118; Syphard et al., 20139). Land use planning involves land allocation, distribution, or restriction for various purposes, considering communities’ immediate and long-term needs. When thoughtfully integrated with wildfire management measures, land use planning tools, such as zoning and building codes and subdivision rules, can provide a strategic framework to mitigate fire hazards, and foster safer, more sustainable communities (Burby et al., 200010; Ge & Lindell, 201611).

Existing literature demonstrates that land use planning can be considered a vital and proactive strategy to reduce fire risk and enhance community resilience through wildfire adaptation approaches. When thoughtfully integrated with wildfire management measures, land use planning tools, including zoning, building codes, subdivision rules, etc., can provide a strategic framework to mitigate fire hazards and foster safer, more sustainable communities (Burby et al., 2000; Ge & Lindell, 2016). Despite its potential significance in wildfire management, however, few communities adopt land use adaptation strategies for wildfire, and fewer still do so in unincorporated areas, which face increasing wildfire risk but are less likely to undertake mitigation actions (Radeloff et al., 201812).

This indicates a need for an in-depth examination of whether and how unincorporated communities adapt to wildfire risk and the extent to which they depend on land use planning to do this. This study seeks to fill this gap by examining the use and perceptions of land use planning strategies for wildfire adaptation in unincorporated areas. The findings from this study shed light on the perceptions and challenges of using land use planning strategies to build fire-resilient communities.

Literature Review

In 2021, there were more than 63,661 communities in the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) at risk of experiencing wildfires in the United States, with only 30% having any wildfire protection plans in place to prevent disaster (National Association of State Foresters [NASF], 202113). Meanwhile, the WUI continues to grow at approximately two million acres per year, with 41% of new housing in the WUI introduced from 1990-2010 (NASF, 2021; Radeloff et al., 2018). This combination of increasing wildfire risk and severe under-preparedness creates heightened risks for many WUI communities. It also raises questions about viable options to mitigate against and adapt to wildfires in these communities, as well as existing challenges and opportunities to pursue these adaptations.

Existing wildfire management practices tend to overemphasize mitigation actions such as fire suppression (including fuel reduction and emergency response planning) rather than focusing on adaptive land use planning (Abrams et al., 201614; McGee, 201115). Here, mitigation is understood as actions taken to address the source of the wildfire and/or climate risk, while adaptation is understood as actions taken to reduce exposure to or cope with those risks (Scott et al., 2020). While mitigation is critical to wildfire management in the WUI, it is also expensive, often conducted in an ad hoc manner, and only results in the short-term protection of properties (Gan et al., 201516).

Alternatively, land use adaptations, which include actions such as improving building codes, rezoning, land readjustment, property acquisition, buyouts, promoting incentive-based development, and community relocation using comprehensive or mitigation plans, can allow communities to better balance their disaster risks and long-term growth aspirations (Ajibade et al., 202017; Canadas et al., 202318; Olshansky, 200119; Schlickman et al., 202220). The lack of attention paid to land use adaptations to wildfire at the municipal level may be due to ecological, socioeconomic, cultural, and institutional reasons that have not been deeply explored. A recent study by Mockrin et al. (2020)21 suggests that land use planning and regulation for wildfire is inhibited by a general distrust in land use planning, concerns about the economic impacts on the community, inadequate financial resources, limited ability of local government to adopt such actions, and a general lack of public support. Other barriers that are common to wildfire management, such as poor understanding of risk and exposure, lack of actionable data, absence of clear leadership, and lack of previous and/or recent experience managing wildfires, may also influence the implementation of land use adaptations (Colavito, 202122; Fillmore et al., 202123; Hunter et al., 202024; Miller et al., 202025).

The challenges to land use adaptations are even more significant for unincorporated areas. U.S. federal law defines unincorporated areas as “any area not within the corporate or municipal boundaries of any [legally defined] municipality” (Definitions, 196726). In contrast to incorporated cities governed by independently chosen city or town halls, county governments regulate most of the unincorporated areas in the United States. Unincorporated areas are often characterized by inexpensive land, urban sprawl, and limited control over land use when compared to incorporated municipalities (Carruthers, 200327). Poor enforcement of land use regulations in unincorporated areas has also resulted in fragmented and informal housing development, especially in areas on the periphery of growing metropolitan regions (Durst & Wegmann, 201728). This, in turn, can result in greater levels of intermix WUI which is defined as an area where houses and wildland vegetation directly intermingle, thereby contributing to greater wildfire exposure for unincorporated communities (Edgeley et al., 202029; Radeloff et al., 2018).

Indeed, new housing construction has been shown to contribute most to the growth of the WUI; the houses within the WUI in western states form a large proportion of all housing in these states; and, worse, the western United States (especially the northern Rockies) is experiencing extremely fast growth (Radeloff et al., 2018; U.S. Fire Administration, n.d.30). All this indicates a significant increase in wildfire exposure to unincorporated areas, as well as increased vulnerability attributable to poor land use controls and regulations, which could spell disaster for the future.

Research Questions

In light of these issues, this study asks the following questions:

- How are wildfire adaptation strategies, such as land use planning, currently being used in unincorporated communities of Colorado?

- What are the constraints or challenges of adopting such strategies in unincorporated areas of Boulder County in light of recent wildfires?

Research Design

The study uses a qualitative research approach to investigate wildfire management in the Colorado. Qualitative inquiry approaches allow for an in-depth and nuanced understanding of complex socioeconomic and institutional phenomena such as wildfire management (Labossière & McGee, 201731; Mockrin et al., 2020; Paul & Milman, 201732). The study was conducted in two parts. In the first, we conducted a secondary document review of 20 community wildfire protection plans (CWPPs) and 63 county hazard mitigation plans in Colorado. The second part involved using key informant interviews with stakeholders involved in wildfire mitigation and recovery after the 2021 Marshall fire to further investigating the findings of part one. Boulder County was focused on specifically. Interviews included state and local government officials and representatives of nonprofit organizations.

Study Site

As with most of the western United States, Colorado’s unique climatic conditions make it highly prone to wildfires (West et al., 201633), with 15 of the 20 largest acreage wildfires in the state occurring between 2013 and 2022 (Colorado Division of Fire Prevention & Control, n.d.34). The historical peak season for wildfires has shifted, and the average duration of wildfires in Colorado trended upward since the 1970s. Forecasts based on climate projections indicate the state's fire risk will escalate in the next 30 years with increasing temperatures, prolonged drought conditions, and higher number of properties exposed to wildfire hazards (Freedman & Geman, 202135).

The study site for this research is Boulder County, Colorado which as of 2023 has a population of 327,468 (Boulder County Government, n.d.36). Approximately 15% of this population is estimated to live in unincorporated areas (Boulder County Public Health, 201437). Unincorporated Boulder County includes eight distinct unincorporated communities, namely Allenspark, Coal Creek Canyon, Eldora, Eldorado Springs, Gold Hill, Gunbarrel, Hygiene, and Niwot (Boulder County Government, n.d.). Some of these communities are suburban in nature (for example, Gunbarrel and Niwot) while others are rural (for example, Allenspark, Coal Creek Canyon, Gold Hill, Hygiene, Eldorado Springs and Eldora). Unlike the incorporated communities of Boulder County that have their own governments, all the unincorporated communities of the county are governed by a single Board of County Commissioners (BOCC) which consists of three members elected at large. These Commissions are responsible for adopting regulations and ordinances (including those related to fire safety) in consultation with the County’s Community Planning & Permitting Department.

Approximately 58% of Boulder County residents live in WUI areas, of which approximately 16% face moderate-to-high levels of wildfire risk (Colorado Forest Atlas, n.d.[^Forest Atlas, n.d.). While the specific wildfire risk to unincorporated communities within the county is unknown, they do face significant risk as demonstrated in the 2021 Marshall Fire which destroyed 157 homes and more than 200 parcels of land in unincorporated Boulder (Boulder County, n.d.[^Boulder County, n.d.]).

Fire safety regulations in unincorporated communities of Boulder County vary based on which Wildfire Zones they fall under. The more rural, heavily forested and mountainous communities such as Coal Creek Canyon and Elardo fall under Zone 1 which has generally been subject to more fire-safety regulations than the suburban communities of Gunbarrel and Niwot that fall in Zone 2 (plains and grasslands) (Boulder County Community Planning and Permitting, 202238). However, after the 2021 Marshall Fire which occurred in Zone 2 and is considered the most destructive wildfire in the state’s history, the BOCC has considered expanding fire-safety regulations—such as the ignition resistance requirement for construction—into Zone 2 (Gabbert, 202239; Boulder County Community Planning and Permitting, 2022).

Data Collection

Document Review

We systematically collected and reviewed two types of documents related to wildfire management in the state of Colorado: (1) county-level community wildfire protection plans (CWPPs), and (2) county-level and tribal hazard mitigation plans (HMPs).

Sampling: This study focuses on CWPPs and HMPs because these plans are more likely to focus on hazard-specific land use regulations and strategies than other types of general or land use plans. While CWPPs are more directly related to wildfire planning, HMPs may also contain strategies for wildfire mitigation because of their mandated multi-hazard focus (Mitigation Planning, 200240). Including both plans in this analysis allowed the study to capture all possible planning for wildfire mitigation and adaptation.

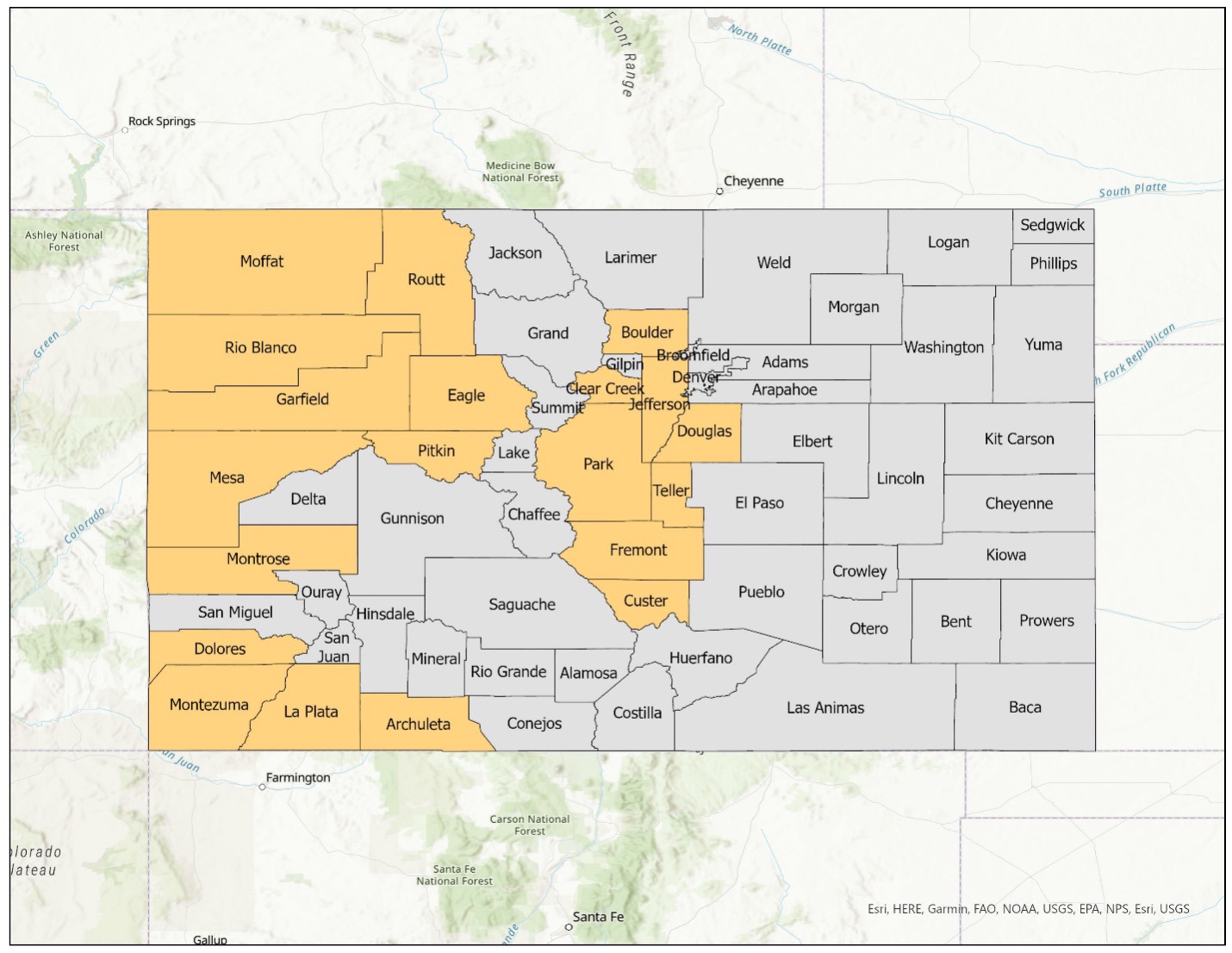

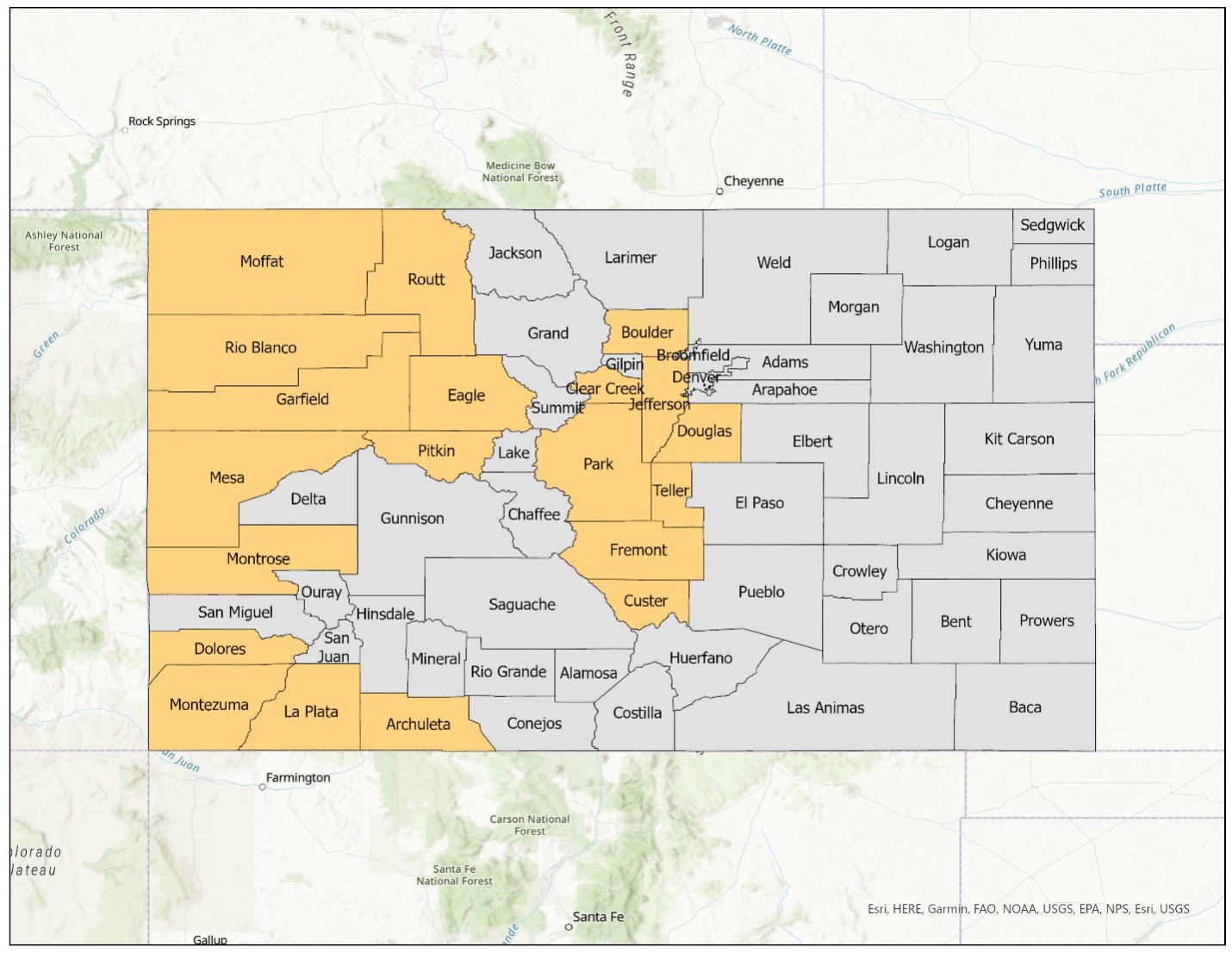

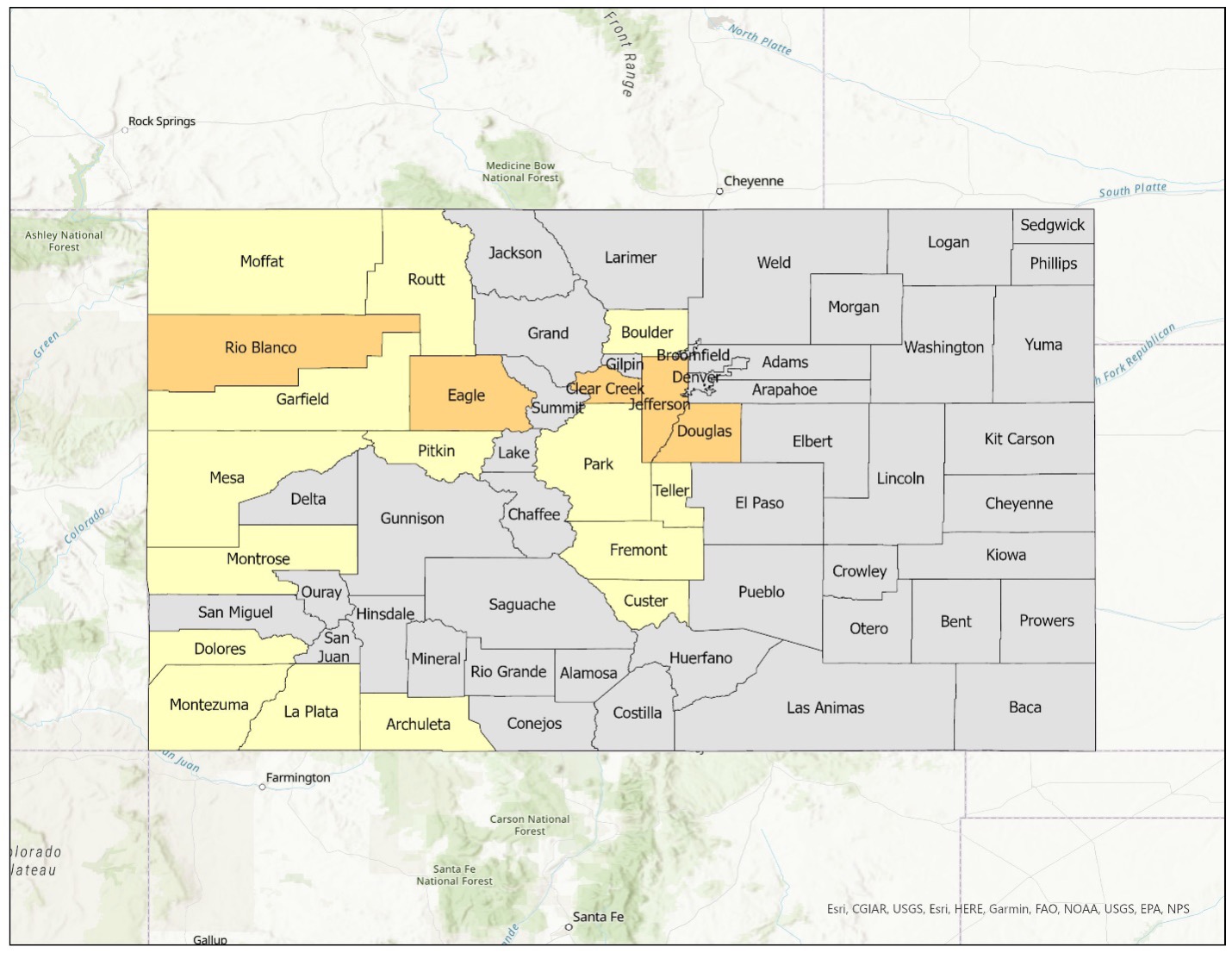

Plans used in this analysis were selected based on the following criteria. First, we selected plans developed at the county level because planning for unincorporated areas is conducted through county-level and not community-level plans (since counties directly govern unincorporated lands). There are no standalone CWPPs or HMPs created for unincorporated lands specifically. Second, for CWPPs we focused on the 20 counties with the highest percentage of area at risk of wildfire, as identified by the 2018 Colorado Enhanced State Hazard Mitigation Plan (Colorado Department of Public Safety, n.d.41). This resulted in a total of 20 CWPPs selected for analysis. For HMPs, we collected county-level HMPs for all 64 counties except three (Jackson, Moffat, and San Juan) that did not have publicly available plans. We also collected HMPs for two Native American tribes that had their plans available online. This resulted in a total of 63 HMPs selected for analysis.

Figure 1. Community Wildfire Protection Plans Reviewed.

Figure 2. Hazard Mitigation Plans Reviewed.

These secondary documents were sourced from the websites of county and state-level agencies, including the Colorado Department of Natural Resources and the Colorado Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. Both types of plans were analyzed for strategic actions that related specifically or predominantly to wildfires with particular attention paid to land use actions.

Key Informant Interviews

Sampling. The document review activity was supported by 14 key informant interviews with diverse stakeholders, including state, county, and local government officials and a representative of a nonprofit organization working in Boulder County. Interviewees included five county and city planners or elected officials, eight disaster specialists (recovery managers, mitigation and resilience officers, and meteorologists), and one nonprofit representative who was actively involved in recovery and mitigation after the Marshall Fire. We identified potential informants through web searches, wildfire reports, and snowballing.

Interview Protocol. We conducted in-person and online interviews (using Zoom) based on study participant preferences and availability. Study participation was voluntary and conducted with the informed consent of the participants following Institutional Review Board requirements of the University of Utah (IRB 00163790). Interviews were recorded to facilitate note-taking and transcription. In-person interviews were conducted during an eight-day field trip in July 2023. The online interviews were conducted between March and July 2023. The semi-structured, open-ended interviews covered topics such as wildfire mitigation and adaptation actions after recent fires, including the 2021 Marshall fire, the extent to which land use planning was or was not considered in this mitigation and adaptation planning, and why. Interviews also focused on assessing participant understanding of the feasibility of land use adaptations within their community.

Data Analysis

Document Review

We used descriptive statistics and GIS mapping tools to describe the document review data. Data was analyzed for three types of wildfire management strategies implemented within different counties across Colorado: wildfire response, wildfire mitigation and adaptation, and land use planning. This data is reported using maps and descriptive statistics.

Interview Data

Interviews were transcribed using the “close” or “attentive” listening technique, which involves repeated, careful listening of an audio recording, identifying themes and concepts occurring in the conversation, and transcribing only parts of the recording of import to the study (Bauer, 199642). The transcribed data was then coded and analyzed using thematic analysis. We identified five themes that affect the adoption of and attitudes towards land use adaptation to wildfire including: (i) governance structure, (ii) organizational capacity, (iii) fears of overregulation, (iv) community acceptance of land use strategies, and (v) concerns for equity.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

Researchers took into account two ethical considerations related to this research. The first was to ensure that undue burden was not placed on Boulder County communities affected by the Marshall Fire. To circumvent this possibility, and in addition to requiring IRB training for all personnel, the study primarily focused on secondary data collection that did not involve local residents and only collected primary data from planning and emergency management organizations. The second was the need to protect study confidentiality, given the narrow geographic and topical focus of the research. To do so, this study only uses broad of participant classifications and excludes names and organizational affiliations throughout the report.

All study team members are urban planners by training with varying levels of experience in conducting qualitative inquiry studies in hazards and disaster planning. Co-PIs Chandrasekhar, Contreras and Finn have each been engaged in disaster studies for over a decade while Co-PI Isaba is a new doctoral student in the field of disaster planning.

Findings

Review of Wildfire Planning Strategies Used in Colorado

Community Wildfire Protection Plans

County-level CWPPs provide planning guidelines for wildfire management in unincorporated areas. We analyzed 20 county CWPPs in Colorado to understand the types of strategies being considered for wildfire planning in unincorporated areas and the extent to which land use adaptations feature in this planning. Based on our analysis, we found three types of wildfire management actions being promoted in CWPPs: (i) wildfire preparedness and response strategies which are actions to be taken before or after a wildfire event to reduce its immediate risk and impact to communities; (ii) wildfire mitigation and adaptation strategies which refer to long term actions to reduce risk and impact of wildfires, and (iii) land use planning strategies which are a subcategory of wildfire adaptation strategies but focused specifically on regulating the built environment conditions (including buildings and lands) of at-risk communities.

Wildfire Preparedness and Response: Wildfire response preparedness generally refers to shorter term actions taken during or immediately after of wildfire events to protect the human and natural environment (U.S. Departments of Interior and Agriculture, 2014). These actions can include pre-event response training and drills, organizational resource assessment, community education on fire prevention, fire suppression, and community evacuation and sheltering. In our examination of 20 CWPPs, we observed that each of the 20 documents outlined some types of preparedness and response measures, including conducting regular multi-jurisdictional exercises among local firefighting agencies, resource assessment for each involved agency, developing pre-attack or operational plans for areas with elevated risk, and assessing existing fire hazards in the community.

Figure 3. Community Wildfire Protection Plans That Include Response/Preparedness Actions to Address Wildfire Risk.

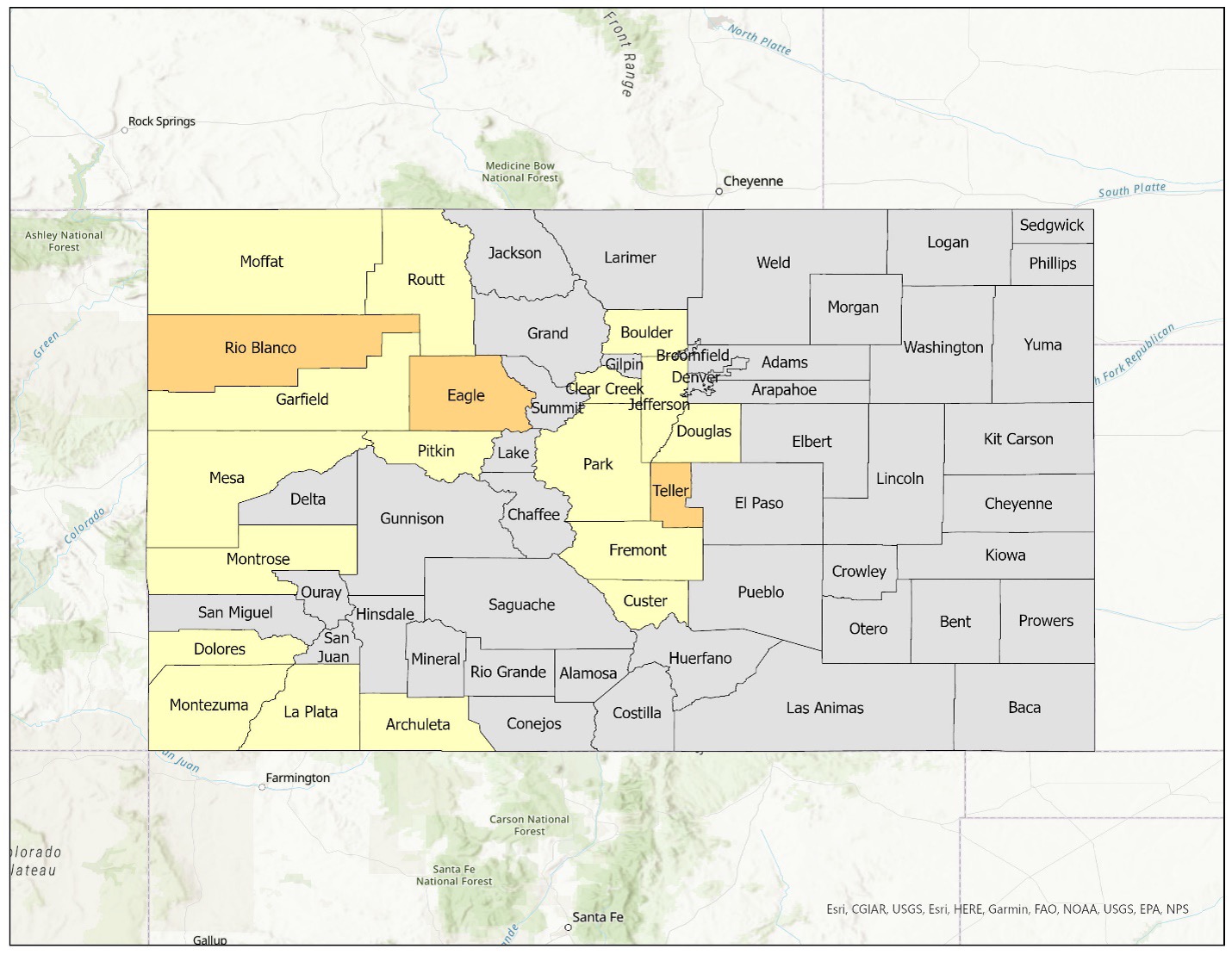

Wildfire Mitigation and Adaptation: Mitigation and adaptation refers to long-term actions taken to reduce the risk or impacts of wildfire in communities (Canadas, et al, 2023). As described earlier, mitigation action addresses the source of the wildfire and/or climate risk, while adaptation refers to actions that reduce exposure to or cope with those risks (Scott et al., 202043). This includes property-level actions such as creating defensible spaces, buffer zones and creating fire-resistant landscapes. All 20 community wildfire protection plans reviewed included at least some type of mitigation activity, such as requiring adequate defensible space around the houses, creating buffer zones between buildings, planting fire-resistant vegetation that slows the spread of fire, designing fuel breaks in strategic locations, generating a WUI hazard map, and conducting fuel management and reduction projects to influence fire behavior. Only three of the 20 plans mentioned wildfire adaptation as a strategy. When such adaptations were identified, they predominantly focused on forest management, requiring changes to landscapes, and fostering fire-adapted ecosystems.

Figure 4. Community Wildfire Protection Plans That Include Mitigation Measures to Address Wildfire Risk.

Figure 5. Community Wildfire Protection Plans That include Wildfire Adaptation Measures to Address Wildfire Risk.

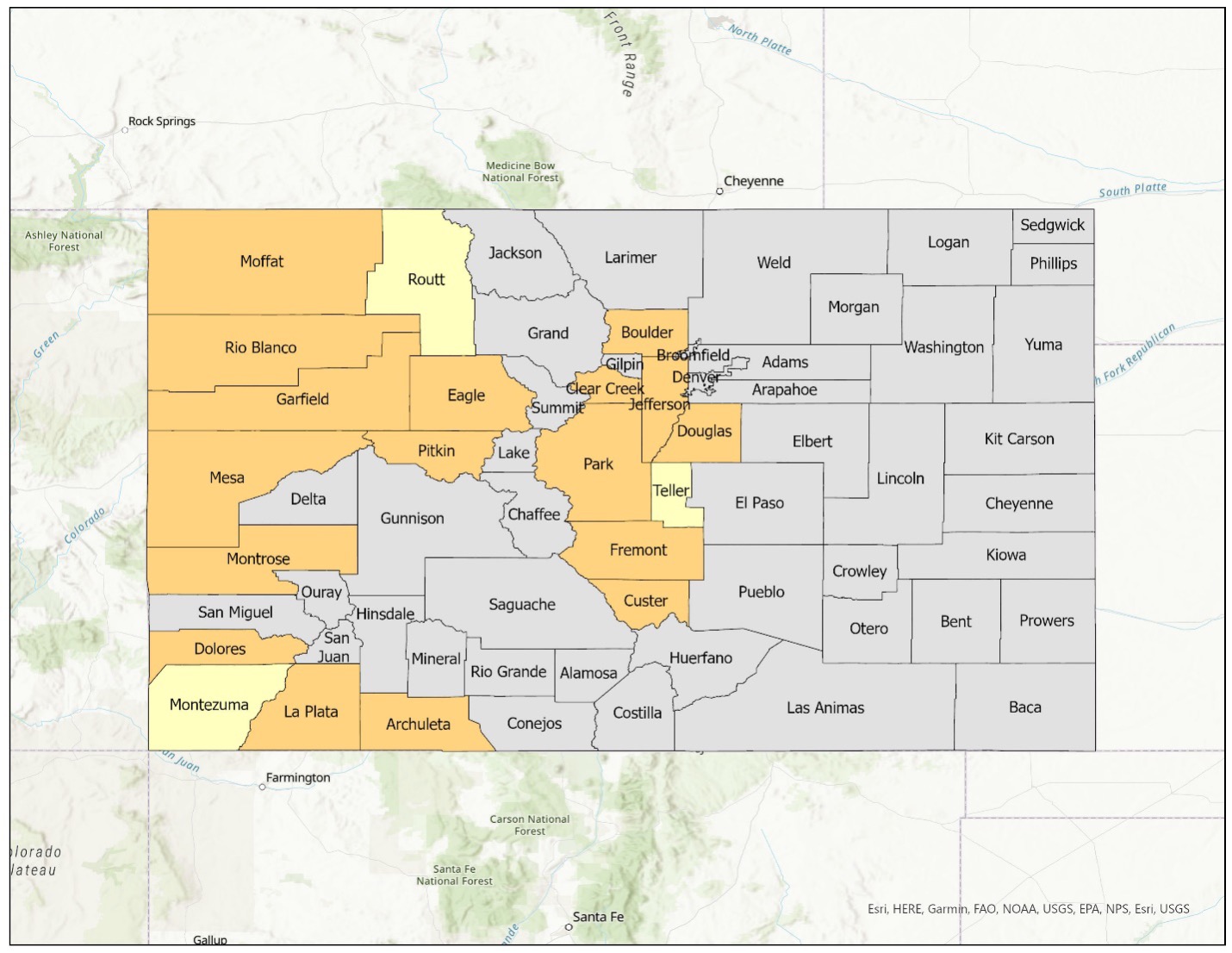

Land Use Planning: Land use planning strategies are a subset of mitigation and adaptation actions that communities can take to manage impacts of wildfires. Land use planning refers to actions taken to regulate built environment conditions of a community in the present and future, such as zoning, building codes, subdivision regulations, and development incentives including property acquisition and buyouts (U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit, 201744). In the context of our analysis of the reviewed CWPPs, we observed that the references to land use codes and regulations primarily pertained to the property-level scale. Some CWPPs, such as the Fremont County Community Wildfire Protection Plan (2008)45, recommended using land use code to uphold wildfire management strategies on both private and public lands. However, such recommendations are typically suggested for new construction and not existing properties, which could carry equal, if not greater risk, due to structural ageing.

When considering specific land use measures, our review indicated that community-scale actions such as zoning were less likely to be recommended than property-level actions, such as implementing building codes. Only five of the 20 CWPPs mentioned zoning as a means to manage wildfire risk, while 17 emphasized the enforcement of building codes and wildfire-resilient construction practices. For instance, the 2012 CWPP for Rio Blanco, the county with the highest percentage of areas at wildfire risk, noted that density might be a consideration in future land use mapping categories. The Rio Blanco CWPP (2012)46 also highlighted that creating fire-adapted communities through zoning regulations would be more cost-effective than traditional mitigation measures.

Figure 6. Community Wildfire Protection Plans That Include Building Regulations to Address Wildfire Risk.

Figure 7. Community Wildfire Protection Plans That Include Zoning or Community-Scale Regulations to Address Wildfire Risk.

Hazard Mitigation Plans

Unlike CWPPs, which are wildfire-specific, hazard mitigation plans address all possible hazards a county may experience. Sixty plans of the 63 plans reviewed (95%) contained at least one action related to wildfires, while three counties (Logan, Otero, and Prowers) did not have any wildfire-specific measures. Among the 63 plans reviewed, 239 county-level wildfire-related actions were identified. The Boulder City/County Hazard Mitigation Plan had the most wildfire-related guidance, at a total of 15 actions. Overall, the 60 plans that included wildfire-related measures contained an average of 3.79 actions, with a median of three. The total number of all actions in every plan was not calculated, but most likely surpassed 1,000. This study focused solely on actions specific to wildfires rather than those that encompassed wildfires as part of multi-hazard measures.

We ultimately identified 16 items (6.7% of all wildfire-related actions) that focused on adaptation actions such as land use planning, zoning, regulating new development, and related approaches. These items were present in hazard mitigation plans from 12 counties (19% of all hazard mitigation plans reviewed). Only three counties had more than one adaptation-related item—the Boulder City/County plan (2 actions), the Montrose County plan (3 actions), and the Park County plan (2 actions).

Unfortunately, the actions contained in hazard mitigation plans often lacked specificity, making it somewhat difficult to develop a deep understanding of the proposed actions. For example, we identified an additional three items in our preliminary analysis as possibly related to land use planning, but ultimately excluded them from our results because of ambiguous wording. After analyzing the 16 land use planning adaptation actions in the 12 counties, we found evidence that while only a few communities were using this approach, land use related adaptations took many forms. These included revising land use and subdivision regulations for wildfire mitigation; updating site plan reviews and building permit guidelines; integrating hazard mitigation plans with local comprehensive land use plans; revising zoning codes to emphasize setbacks, defensible space, and weed control; updating subdivision infrastructure guidelines (e.g., road design); and limiting new development in high-risk areas.

Challenges of Land Use Adaptation to Wildfire

Evidence from review of CWPPs and HMPs suggests that land use adaptation approaches are still relatively rare in unincorporated Colorado communities. Analysis of interview data revealed five major challenges to the adoption of community-scale land use strategies to manage wildfire risk, as described below.

Governance and Decision-Making Structure

The Boulder County study participants generally agreed that having strong governmental support is an important element for pursuing any type of wildfire adaptation plans. One planner, for example, described unincorporated areas of Boulder County as not having “a public sector advocate fighting for [them]” in contrast to incorporated communities, which have an organized government to pursue resources and advocate on their behalf. Another participant identified centralized decision-making as impacting the success of wildfire adaptation measures, citing the example of California, which conducts wildfire management using state codes, unlike Colorado, where planning and governance is locally oriented.

Unincorporated areas also have a complex landscape of political representation that challenges consensus-based mitigation and adaptation planning. One participant described the challenge this way: “The incorporated cities have a higher number of elected officials involved in decision-making. So, there's just more people making the decision, which makes it harder and it also makes it easier for them to cave to public pressure, I think.” This observation implies that a significant number of strong opinions from the community can make decision-makers feel compelled to cater to the demands of the public, underscoring the political nature of policymaking in unincorporated areas.

Organizational Capacity Issues

One major concern related to organizational capacity was insufficient staffing to pursue land use adaptation measures, especially in unincorporated and rural communities. As one state official noted:

[These communities] have very limited capacity with staff, so high-intensive land use strategies in terms of requirements—let's say building codes that require lots of inspections for very large counties with no staff—you have to be thinking also about how you would implement these strategies.

Some participants also identified lack of funding to undertake land use adaptations like property acquisition or buyouts of hazard-prone property as a significant challenge. Participants attributed this lack of funding to two reasons. First, some planners and state officials claimed that unlike the case of floods, buyouts and property acquisition for wildfire adaptation was not yet broadly accepted within WUI communities which had resulted in lower state and local funding allocations to pursue such strategies. Second, some participants claimed that buying out properties in wildfire-prone urban areas is prohibitively expensive because of high property values. These claims match a 2023 report from the Boulder County Assessor that describes a 35% increase in property value county-wide and a 35-41% increase in property value in unincorporated areas (Boulder County Assessor, n.d.47). As a solution to the problem, participants suggested clear earmarking of federal funds for wildfire-related buyouts and property acquisition.

Adequacy of Current Efforts

Several participants stated that implementing land use regulations would be a challenge in Boulder County because it already has rigorous code enforcement so adding more regulations would further burden homeowners. Some participants also felt that existing land use regulation efforts, such as the Wildfire Partners program in unincorporated Boulder County, were already helping residents mitigate their properties (Wildfire Partners, n.d.48). One planner attributed this program to the “long-term commitment to wildfire mitigation and land use protection” and stricter codes in unincorporated Boulder County. Another participant questioned the need for land use planning strategies such as managed retreat or relocation, saying that it “is not, I would say, feasible, nor maybe required, when you could also balance home hardening and other WUI land management practices to mitigate and slow fire spread.” It is important to note, however, that very few of the participants commented on whether existing measures were adequate to address recent repetitive fire events or the increasing risk of catastrophic fire caused by climate change.

Equity and Social Justice Concerns

Concerns were also raised in interviews about the potential for negative impacts when imposing land use regulations on marginalized communities, including increasing barriers to homeownership. One participant described the problem as such:

Home ownership is targeted for the haves in the society. It's already targeted towards white families who have generational wealth, and if we increase the building codes, what does that do to families of color or poor white families who are trying to buy a first house?

Participants also expressed concern about how incentives and resources for mitigation and adaptation privileges residents who are able to rebuild in the same location. As one participant said, “Incentives and resources only are available if you choose to rebuild. So [if they] moved to another area, those folks have not had the same access to resources and assistance.” Since disaster displacement and social vulnerability are highly correlated, this implies that adaptation could end up benefiting higher-income residents disproportionately in the long run (Elliott & Pais, 201049).

Community Resistance to Regulation

Multiple participants suggested that some Boulder County communities might be unwilling to make changes to their structures and surrounding built environment. Even if communities are interested in implementing land use measures, they could encounter opposition from the prevailing culture that champions property rights and resists regulation. In these communities, participants suggested focusing more on incentives or education.

Participants indicated that residents in unincorporated county areas are more or less inclined to resist regulatory actions than those in cities or towns. One Boulder County official hypothesized that the reason people choose to live in unincorporated areas is that they likely desire less government intervention, which also makes them less likely to “adhere to, listen to, and stick with the rules and regulations.” However, another Boulder County official felt that this hypothesis did not apply to the context of Boulder County, where populations in both incorporated and unincorporated areas were “supportive of regulatory programs.” According to this participant, “each community has its own culture and politics,” which determined what actions were acceptable to most or not.

Discussion

The findings of this study show that while wildfire management plans in Colorado generally incorporate land use actions to promote long-term adaptation, these actions tend to be targeted at individual properties (through fire safety building codes, for example) and not at community-scale, such as through zoning restrictions, cluster development, property buyouts, or managed retreat. Furthermore, while property-level actions can be effective in mitigating future wildfire risk, they are generally dependent on individual compliance by property owners and may not be adequate to address the increasing uncertainty of wildfire risk in WUI communities of Colorado. These property-level actions are also too often focused on regulating new construction and not enough on mitigating existing risk. The interview data supports the document review finding that land use is part of a broad conversation about wildfire management at the state and county level, but that conversation generally revolves around building code updates or construction material regulations, not zoning or other community-scale actions.

The interviews also provide some explanation for current state of wildfire management. While none of the participants rejected community-scale strategies such as zoning or managed retreat outright, they raised concerns that included lack of government capacity, challenges with coordinating land use actions in highly decentralized settings, and concern about how increased regulation is received at the local level. Concerns that additional regulations or implementing community-scale programs (such as buyouts) would burden lower income communities were also raised. Such equity issues are likely to be greater in unincorporated areas where community representation lacks cohesion, and there might not be a clear government advocate for local populations. Governmental capacity, which is generally poorer in unincorporated areas, may also lower the focus on longer-term adaptation.

Conclusions

Implications for Mitigation and Recovery Planning Practice

Based on the findings, the study presents three clear recommendations for improving wildfire adaptation planning in unincorporated communities. First, we recommend that mitigation and recovery planners promote a fuller set of land use strategies for wildfire adaptation than what is currently being implemented locally. In addition to existing strategies such as building codes and defensible space practices, emergency managers should also promote community-scale land use strategies such as zoning, cluster development, managed retreat, buyouts, and property acquisition which have proven to be viable and cost-saving options in flood-prone communities (Greer & Binder Brokopp, 201750; Nelson & Camp, 202051). If the more diffused risk geographies associated with wildfire makes large-scale buyouts and managed retreat infeasible, mitigation and recovery planners could still promote the use of mid-range solutions such as clustered development to promote wildfire resilience. Colorado’s Planning for Hazards website, which provides actionable guidance on integration of land use planning and hazards planning, is a useful resource in this regard and should be integrated into best practice guides for CWPPs and HMPs within Colorado. The website may also provide a template for similar efforts in other FEMA Region 8 states.

Second, we recommend that mitigation and recovery planners pay close attention to institutional capacity issues in wildfire adaptation planning in unincorporated areas. Adequate and reliable funding as well as staff support to county government is necessary for long-term effectiveness of land use adaptations. FEMA Region 8 staff can play a significant role in this regard by providing greater levels of technical assistance, financial assistance, and scientific data for the purpose of community adaptation planning to local governments. Targeting these efforts at the county level will have the greatest impact on unincorporated communities since these areas are governed directly by county governments. It is important that such assistance be offered before disaster strikes because discussions about integrating resilience goals into future growth planning requires a high level of community engagement, which is difficult to achieve under urgent conditions of post-disaster recovery (Olshansky et al., 201252).

Third, we recommend that FEMA Region 8 personnel attempt to increase their active collaboration with grassroots organizations that have experience in working in local communities, especially with individuals with low-incomes or other socially vulnerable groups, to promote land use adaptations at the property- and community-scale. Research suggests that resilience-based and sustainable development actions do not always result in equitable outcomes for marginalized populations (Checker, 201153; Gould & Lewis, 202154). Based on our interviews, equity appears to be a real concern for the wildfire management community in Colorado. To ensure effective and equitable outcomes for the more socially vulnerable residents, we recommend that FEMA Region 8 mitigation and recovery planners engage with local nonprofits and community-based organizations to broaden participation in wildfire adaptation planning by educating local residents, especially lower income residents about the benefits of such approaches by partnering with local nonprofit groups who are trusted local information brokers (Chandrasekhar et al., 202255).

Limitations

This study has two limitations that affect the generalizability of its results. First, it is limited to an examination of Colorado (for plan review) and Boulder County (for interviews), both of which represent a very specific governance context. Emergency management and urban planning practices, building code adoption, and other regulatory constraints vary from state to state. Second, the interviews conducted only focus on Boulder County which is wealthier than other parts of the state—the county currently ranks sixth highest in terms of median household income according to the 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. On the other hand, research shows that living in unincorporated communities is generally associated with higher levels of social vulnerability (Gomez-Vidal & Vida, 202156; Mattiuzzi & Weir, 202057) which implies a need to study unincorporated communities in other Colorado counties and states. Importantly, as many of our participants pointed out, Boulder County populations are typically more civically engaged and open to adoption of land use regulations, which may not be typical of other places.

Future Research Directions

The next steps for this study involve expanding the study to other states within FEMA Region 8 with rapidly expanding WUIs, as well as examining comprehensive land use plans in addition to CWPPs and hazard mitigation plans. The study team also hopes to expand the number of key informants for this study by interviewing national-level experts and community stakeholders in wildfire adaptation and land use planning to understand the state-of-art in policy and practice.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported through the FEMA Region 8 Quick Response Research Award Program of the Natural Hazard Center in Boulder and the Graduate Student Research Funding program of the Global Change and Sustainability Center at the University of Utah.

References

-

Thomas, D., Butry, D., Gilbert, S., Webb, D., & Fung, J. (2017). The costs and losses of wildfires. NIST Special Publication, 1215(11). Available at: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1215.pdf ↩

-

Weber, K. T., & Yadav, R. (2020). Spatiotemporal trends in wildfires across the Western United States (1950–2019). Remote Sensing, 12(18), 2959. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12182959 ↩

-

Koksal, K., McLennan, J., Every, D., & Bearman, C. (2019). Australian wildland-urban interface householders’ wildfire safety preparations: Everyday life project priorities and perceptions of wildfire risk. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 33, 142-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.09.017 ↩

-

Liu, Z., Wimberly, M. C., Lamsal, A., Sohl, T. L., & Hawbaker, T. J. (2015). Climate change and wildfire risk in an expanding wildland–urban interface: A case study from the Colorado Front Range Corridor. Landscape Ecology, 30(10), 1943-1957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0222-4 ↩

-

U.S. Departments of Interior and Agriculture. (2014). A National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy. https://www.forestsandrangelands.gov/documents/strategy/strategy/CSPhaseIIINationalStrategyApr2014.pdf ↩

-

Brzuszek, R., Walker, J., Schauwecker, T., Campany, C., Foster, M., & Grado, S. (2010). Planning strategies for community wildfire defense design in Florida. Journal of Forestry, 108(5), 250-257. https://academic.oup.com/jof/article/108/5/250/4598913 ↩

-

Headwater Economics. (2016, January). Land use planning to reduce wildfire risk: Lessons from five western cities. https://headwaterseconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/Planning_Lessons_Full_Report_Web.pdf ↩

-

Muller, B., & Schulte, S. (2011). Governing wildfire risks: What shapes county hazard mitigation programs?. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 31(1), 60-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X10395895 ↩

-

Syphard, A. D., Bar Massada, A., Butsic, V., & Keeley, J. E. (2013). Land use planning and wildfire: development policies influence future probability of housing loss. PloS One, 8(8), e71708. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071708 ↩

-

Burby, R. J., Deyle, R. E., Godschalk, D. R., & Olshansky, R. B. (2000). Creating hazard resilient communities through land-use planning. Natural Hazards Review, 1(2), 99-106. [https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2000)1:2(99)https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2000)1:2(99) ↩

-

Ge, Y. G., & Lindell, M. K. (2016). County planners’ perceptions of land-use planning tools for environmental hazard mitigation: A survey in the US Pacific states. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 43(4), 716-736. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813515594810 ↩

-

Radeloff, V. C., Helmers, D. P., Kramer, H. A., Mockrin, M. H., Alexandre, P. M., Bar-Massada, A., Butsic, V., Hawbaker, T.J., Martinuzzi, S., Syphard, A.D. & Stewart, S. I. (2018). Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(13), 3314-3319. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1718850115 ↩

-

National Association of State Foresters. (2021). Communities at Risk Report, Fiscal Year 2021. https://www.stateforesters.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/NASF-2021-Communities-At-Risk-Report.pdf ↩

-

Abrams, J. B., Knapp, M., Paveglio, T. B., Ellison, A., Moseley, C., Nielsen-Pincus, M., & Carroll, M. S. (2016). Re-envisioning community-wildfire relations in the U.S. West as adaptive governance. Ecology and Society, 20(3):34. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-07848-200334 ↩

-

McGee, T. K. (2011). Public engagement in neighbourhood level wildfire mitigation and preparedness: Case studies from Canada, the US and Australia. Journal of Environmental Management, 92(10), 2524-2532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.05.017 ↩

-

Gan, J., Jarrett, A., & Gaither, C. J. (2015). Landowner response to wildfire risk: Adaptation, mitigation or doing nothing. Journal of Environmental Management, 159, 186-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.06.014 ↩

-

Ajibade, I., Sullivan, M., & Haeffner, M. (2020). Why climate migration is not managed retreat: Six justifications. Global Environmental Change, 65, 102187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102187 ↩

-

Canadas, M. J., Leal, M., Soares, F., Novais, A., Ribeiro, P. F., Schmidt, L., Delicado, A., Moreira, F., Bergonse, R., Oliveira, S., Madeira, P. M., & Santos, J. L. (2023). Wildfire mitigation and adaptation: Two locally independent actions supported by different policy domains. Land Use Policy, 124, 106444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106444 ↩

-

Olshansky, R. B. (2001). Land use planning for seismic safety: The Los Angeles County experience, 1971–1994. Journal of the American Planning Association, 67(2), 173-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360108976227 ↩

-

Schlickman, E., Milligan, B., & Wheeler, S. M. (2022, July 13). A case for retreat in the age of fire. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/a-case-for-retreat-in-the-ageof-fire-184031 ↩

-

Mockrin, M. H., Fishler, H. K., & Stewart, S. I. (2020). After the fire: Perceptions of land use planning to reduce wildfire risk in eight communities across the United States. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 45, 101444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101444 ↩

-

Colavito, M. (2021). The human dimensions of spatial, pre-wildfire planning decision support systems: A review of barriers, facilitators, and recommendations. Forests, 12(4), 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12040483 ↩

-

Fillmore, S. D., McCaffrey, S. M., & Smith, A. M. (2021). A mixed methods literature review and framework for decision factors that may influence the utilization of managed wildfire on federal lands, USA. Fire, 4(3), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire4030062 ↩

-

Hunter, M. E., Colavito, M. M., & Wright, V. (2020). The use of science in wildland fire management: A review of barriers and facilitators. Current Forestry Reports, 6(4), 354-367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-020-00127-2 ↩

-

Miller, R. K., Field, C. B., & Mach, K. J. (2020). Barriers and enablers for prescribed burns for wildfire management in California. Nature Sustainability, 3(2), 101-109. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0451-7 ↩

-

Definitions, 49 C.F.R. § 372.239 . (1967, December 20). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49/subtitle-B/chapter-III/subchapter-B/part-372/subpart-B/section-372.239 ↩

-

Carruthers, J. I. (2003). Growth at the fringe: The influence of political fragmentation in United States metropolitan areas. Papers in Regional Science, 82(4), 475-499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10110-003-0148-0 ↩

-

Durst, N. J., & Wegmann, J. (2017). Informal housing in the United States. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(2), 282-297. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12444 ↩

-

Edgeley, C. M., Paveglio, T. B., & Williams, D. R. (2020). Support for regulatory and voluntary approaches to wildfire adaptation among unincorporated wildland-urban interface communities. Land Use Policy, 91, 104394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104394 ↩

-

U.S. Fire Administration. (n.d.) What is the WUI?. https://www.usfa.fema.gov/wui/what-is-the-wui.html ↩

-

Labossière, L. M., & McGee, T. K. (2017). Innovative wildfire mitigation by municipal governments: Two case studies in Western Canada. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, 204-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.03.009 ↩

-

Paul, M., & Milman, A. (2017). A question of ‘fit’: Local perspectives on top-down flood mitigation policies in Vermont. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 60(12), 2217-2233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1283298 ↩

-

West, A. M., Kumar, S., & Jarnevich, C. S. (2016). Regional modeling of large wildfires under current and potential future climates in Colorado and Wyoming, USA. Climatic Change, 134(4),565-577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1553-5 ↩

-

Colorado Division of Fire Prevention & Control. (n.d.). Historical Wildfire Information. https://dfpc.colorado.gov/sections/wildfire-information-center/historical-wildfire-information ↩

-

Freedman, A. & Geman, B. (2021, December 31). Climate changes linked to Colorado's fire disaster. Axios. https://www.axios.com/2021/12/31/climate-change-links-boulder-fires ↩

-

Boulder County Government. (n.d.). Unincorporated Towns & Communities. Boulder County. https://bouldercounty.gov/government/about-boulder-county/unincorporated-towns/ ↩

-

Boulder County Public Health (2014, September). Demographic Summary of Boulder County, Colorado. http://assets.thehcn.net/content/sites/bouldercounty/Boulder_County_Demographics_Summary_FINAL_09_23_2014_20140923145223.pdf ↩

-

Boulder County Community Planning and Permitting. (2022, May 12). Boulder County Building Code Amendments Wildfire Zone 2 Update. https://assets.bouldercounty.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/borc-22-0001-staff-recommendation-packet-20220512.pdf ↩

-

Gabbert, B. (2022, October 29). Report released for the Marshall Fire which destroyed 1,056 structures southeast of Boulder, Colorado. Wildfire Today. https://wildfiretoday.com/2022/10/29/report-released-for-the-marshall-fire-which-destroyed-1056-structures-southeast-of-boulder-colorado/ ↩

-

Mitigation Planning. (2002). Available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-44/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-201 ↩

-

Colorado Department of Public Safety. (n.d.). Enhanced State Hazard Mitigation Plan. https://mars.colorado.gov/mitigation/enhanced-state-hazard-mitigation-plan-e-shmp ↩

-

Bauer M. (1996). The narrative interview: Comments on a technique for qualitative data collection. London School of Economics and Political Science, Methodology Institute. ↩

-

Scott, M., Lennon, M., Tubridy, F., Marchman, P., Siders, A. R., Main, K. L., Herrmann, V., Butler, D., Frank, K., Bosomworth, K., Blanchi, R. & Johnson, C. (2020). Climate disruption and planning: Resistance or retreat?. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(1), 125-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1704130 ↩

-

U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit. (2017, May 15). Planning and Land Use. https://toolkit.climate.gov/topics/built-environment/planning-and-land-use ↩

-

Fremont County Emergency Management. (2008, April 23). Fremont County Community Wildfire Protection Plan. https://static.colostate.edu/client-files/csfs/documents/cwpp042308.pdf ↩

-

Rio Blanco County of Emergency Management. (2012, September). Rio Blanco Community Wildfire Protection Plan Update. https://www.rbc.us/DocumentCenter/View/1982/Appendix-Y---Community-Wildfire-Protection-Plan ↩

-

Boulder County Assessor. (n.d.). 2023 Property Values in Boulder County. Boulder County. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/506c8e672e294e0abaad3f8a18ffeb61/page/2023-Value-Map/ ↩

-

Wildfire Partners. (n.d.) Homeowner Resources. Retrieved on August 28, 2023 from: https://wildfirepartners.org/for-homeowners/ ↩

-

Elliott, J. R., & Pais, J. (2010). When nature pushes back: Environmental impact and the spatial redistribution of socially vulnerable populations. Social Science Quarterly, 91(5), 1187-1202. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00727.x ↩

-

Greer, A., & Brokopp Binder, S. (2017). A historical assessment of home buyout policy: Are we learning or just failing?. Housing Policy Debate, 27(3), 372-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2016.1245209 ↩

-

Nelson, K. S., & Camp, J. (2020). Quantifying the benefits of home buyouts for mitigating flood damages. Anthropocene, 31, 100246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2020.100246 ↩

-

Olshansky, R. B., Hopkins, L. D., & Johnson, L. A. (2012). Disaster and recovery: Processes compressed in time. Natural Hazards Review, 13(3), 173-178. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000077 ↩

-

Checker, M. (2011). Wiped out by the “greenwave”: Environmental gentrification and the paradoxical politics of urban sustainability. City & Society, 23(2), 210-229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-744X.2011.01063.x ↩

-

Gould, K. A., & Lewis, T. L. (2021). Resilience gentrification: environmental privilege in an age of coastal climate disasters. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 3, 687670. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.687670 ↩

-

Chandrasekhar, D., García, I., & Khajehei, S. (2022). Recovery capacity of small nonprofits in post-2017 hurricane Puerto Rico. Journal of the American Planning Association, 88(2), 206-219. ↩

-

Gomez-Vidal, C., & Gomez, A. M. (2021). Invisible and unequal: Unincorporated community status as a structural determinant of health. Social Science & Medicine, 285, 114292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114292 ↩

-

Mattiuzzi, E., & Weir, M. (2020). Governing the new geography of poverty in metropolitan America. Urban Affairs Review, 56(4), 1086-1131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419834075 ↩

Chandrasekhar, D., Finn, D., Contreras, S. & Isaba, T.T. (2023). Land Use Adaptations to Wildfire in Unincorporated Communities in Colorado (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 361). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/land-use-adaptations-to-wildfire-in-unincorporated-communities-in-colorado