Lessons from Concurrent Disasters

COVID-19 and Eight Hurricanes

Publication Date: 2021

Abstract

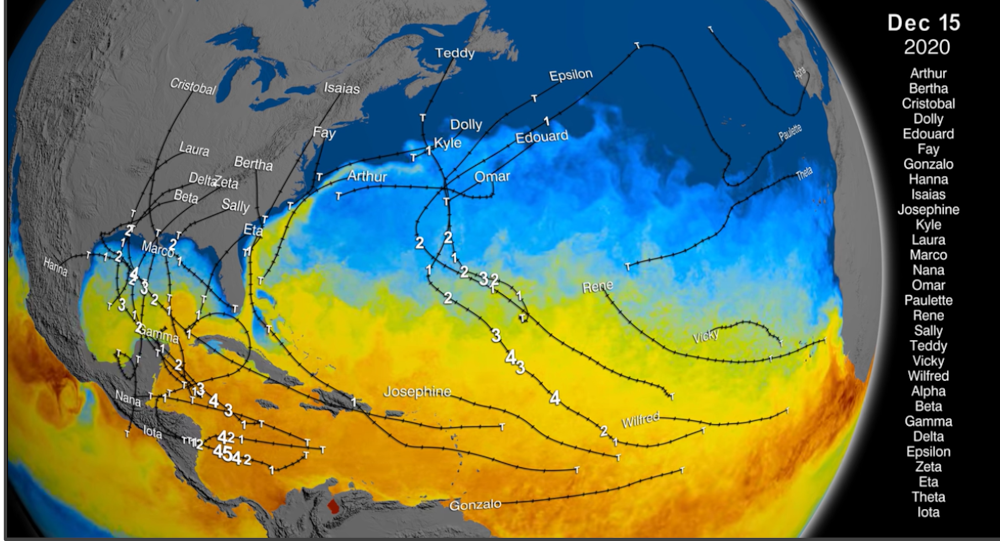

Changing climate dynamics have resulted in a confluence of disaster events to which Louisiana local government leaders and their emergency managers have never before had to respond simultaneously: a global pandemic and an “epidemic” of landfalling hurricanes during the 2020 season. Eight cones with challenging, unusual characteristics passed over Louisiana: (1) Two hurricanes passing over the same location within 36 hours, a fujiwhara—Hurricanes Marco and Laura; (2) 150 mile per hour winds inadequately forecasted and of an almost unprecedented speed last seen in the 1850s; (3) a difficult to forecast surge magnitude that led to incorrect immediate response; (4) delayed long-term recovery efforts from responders outside of the area because of initial reporting errors regarding surge heights and wind speed; and (5) a storm, Zeta, that passed directly over a densely populated area that would have been hard hit by rain and resultant flooding if the storm had slowed. In addition, the number and closeness in dates of storm occurrences led to lengthy coastal high-water levels that altered usual return-to-normal patterns. To these multiple, co-occurring threats federal forecasters, state and local officials, and Louisiana residents responded with expertise and commitment by adhering to close collaboration during weather assessments and COVID-19 surges, modifying evacuation protocols to be responsive to COVID-19, and undertaking multiple protective measures, all contributing to a low death rate from storms and a modest death rate from COVID-19 after the initial Mardi Gras surge when the disease was not known to be present. This research focuses on seeking a deeper understanding of management practices; how officials drew upon their earlier management experiences to manage the unusual; the ways in which practiced relationships between managers and weather forecasters benefited the unique situation; and if/how their response was impacted by the heightened alertness and response reciprocally to the danger of COVID-19 and the storms by both leadership and residents. More just outcomes were supported by the general capacity of the responders; commitment to keep the residents informed about both risks and appropriate responses to them; and the provision of special services, calculated for the new situation of the pandemic and the storm epidemic, for those without the means to respond adequately to both.

Introduction and Literature Review

There is no doubt–drawing upon the events that have unfolded over the last decade or two–that novel disease, environmental, and meteorological events are occurring. If they have previously occurred, they have done so rarely or so distantly in time as to not have an impact on current society. It is important for applied social science and emergency management research to be sensitized to these changes and to be quickly responsive by conducting research that will reveal the potentially needed changes in managing them, i.e., the refinement of earlier behaviors. Can responses practiced for earlier events within “standard” parameters satisfy new response needs, or must adjustments—sometimes outsized—be required to protect communities and thus societies as climate and the environment change?

The confluence of COVID-19 with the 2020 hurricane season offers a test of the sense making/decision-making/implementation frameworks from earlier, more common storm patterns to such a unique and extreme experience within a pandemic of the 2020 season. Managing landings of hurricanes that demonstrate new qualities—two at a time in the same geography (Norwood, 20201: ), extreme wind speeds accelerating rapidly before landfall, and prediction of dramatic (extreme, life-threatening) surge levels that did not happen—within the context of a world-wide pandemicEndnote 1 is a scenario that begs understanding for application of refinements to local disaster management practices. This occurrence also presents many concerns for assuring social justice in emergency management and response because of the new disasters’ qualities.

Two concepts in the literature, one evolving since the 1990s and the other more recently, can be applied to the assessment of the events and officials’ responses: “Sense making” (Takeda et al., 20172) and “disaster layering” (Laska et al., 20153). Sense-making builds on a “deep understanding” of a situation by focusing on prior knowledge, belief systems, situational awareness, environment, uncertainties, opportunities, risks, context, anticipated dynamic future, and perceived alternatives (Weick et al., 2005 in Takeda et al., 2017). Psychologist Tania Lombrozo (20124) is among researchers who believe that the drive to explain the world is a basic human impulse, similar to thirst or hunger. This unusual situation begs the application of such a term because emergency/disaster responses are actions to reduce risk. To make decisions about how to act, the actor must appreciate what is happening and how it differs from earlier emergencies/disasters, i.e., making sense of the new experiences. The interviews that are the basis for this empirical research definitely demonstrate that the officials we interviewed were using significant effort to make sense of these remarkably new situations. Our findings will demonstrate the way in which the respondents sought that “sense.”

Layering, the other concept useful for this research, recognizes the reality of perceived individual events converging to create new situations that require attention to concurrent individual occurrences and their combination. Both concepts contribute to achieving an understanding of these new, complicated weather-related dynamics, as well as the combination of the storm epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic. These foci provide the opportunity to explore assessment of the situation, forming the basis for ensuing actions by local leaders in the response phase to a new super event and drawing a comparison to how “normal” disasters have been managed in the past. The layering is the new situation to which local officials must respond.

Officials’ response to the unusual and overlapping conditions in 2020 can be examined through cognition, framed as “the capacity to recognize the degree of emerging risk to which a community is exposed and to act on the information (Comfort et al., 2010) and the concept of improvisation (Mendonca et al., 20015). The latter includes understanding the way in which the local officials interact with state and federal counterparts and with citizens as they are making their assessment and as they respond (Fairchild et al, 20066Another component to consider is how local officials interacted with the National Weather Service (NWS) as an agency, NWS officials as individual professionals, and with NWS products during times of uncertainty. In addition, we considered how local officials interacted concurrently with parish and state health officials as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded.

How uncertainty is identified and assessed is key to understanding which of the perceived alternatives local officials deemed appropriate, including how the response might be different from that made for a “normal” storm, as well as the role that sensemaking plays. The literature suggests that officials will be seeking commonalities to earlier “normal” storms as they are told by the weather forecasters and journalists that the events will be different. For example, there was an extreme level of evacuation from the coastal areas where Hurricane Laura struck, such that less than five people died during the event. It was likely due to the warning of a catastrophic storm surge (“life threatening”) that motivated residents to evacuate despite the presence of a high rate of COVID-19 within the area. That the surge was not life threatening was not important to the outcome unless some who acquired COVID-19 in the evacuation would not have done so if the forecast had been more accurate and supported their decision to remain home. However, the storm quality of 150 mile-per-hour wind—which was not predicted—was what actually put residents and their property at risk. If the surge had been forecasted correctly, then coastal residents would have remained in place and thus would have been subject to the high winds which were not forecast. The complexity of the storm qualities and the inability to forecast them “layered” to both control and generate risk.

Therefore, one focus of the research is local officials’ response to forecast uncertainty, changing storm dynamics, and perceived error. The response will be based on the effectiveness of NWS forecasts, as Haines & Wood (20107) showed in their research regarding Hurricane Ike. Historically, forecasts have had only a certain level of accuracy, albeit increasingly better, especially on the magnitude of the storm; thus, local officials have commonly normalized errors.

Methodology

Research Questions

The research that forms the basis for this report focused on the following research questions: When two never-happened-before unique disaster experiences co-occur in one U.S. coastal state, the experience of simultaneous and overlapping responses to the events generates multiple—many of them unique—difficult challenges to which those in charge of emergencies must respond. Our research questions are: How does the complexity and unusualness of the disaster situation affect decision-making by local officials whose communities have had a very long history of hurricane experience but not with these qualities? What dimensions of the new, multi-faceted event most challenged the officials? What was their response to those dimensions? Did they modify their behavior from the responses that they made to earlier, more normal storms? The research will seek to determine if parish leaders and disaster managers adjusted their management response or maintained conformity to the response that they had used previously for normal storms. If they did change, are they clear as to what was different in the situations and what they did differently? Or did they consider the event as fitting into their usual response practices, thus requiring little or no difference in response? What lessons were learned about responding to these unique, complicated experiences that will benefit not only those directly involved with their response, but others who manage emergency responses and must anticipate increasingly complex challenges? Additionally, we want to understand what qualities about the emergencies posed extreme challenges with regard to responses. We focus on those lessons most generalizable to emergency management in the 21st century.

Study Site Description

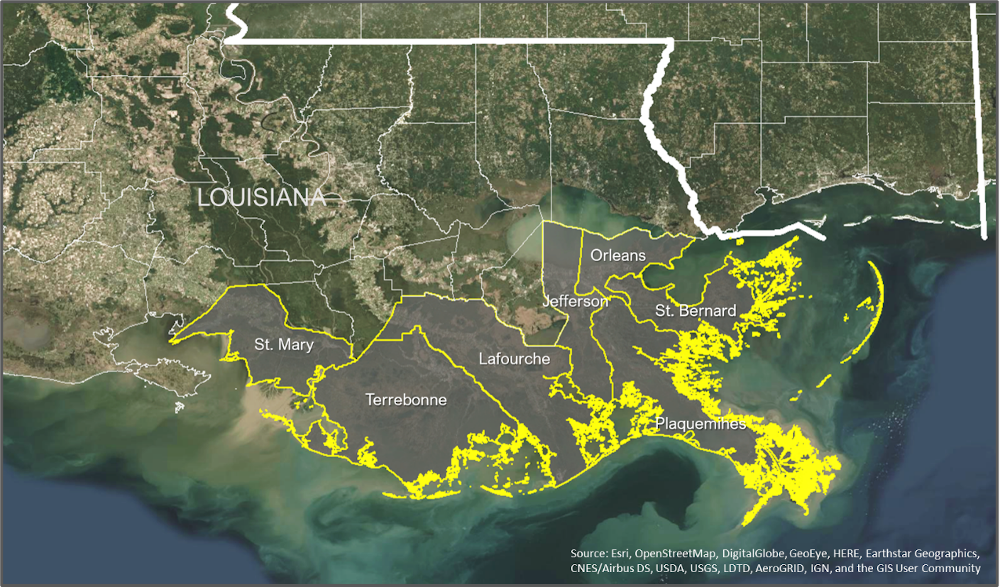

The study site was seven contiguous coastal parishes (counties) in one of the most at-risk coasts of the Atlantic tropical storm basin: LouisianaEndnote 2. They are St. Bernard, Orleans, Plaquemines, Jefferson, Lafourche, Terrebonne, and St. Mary Parishes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Louisiana Parishes (counties) Examines in This Study

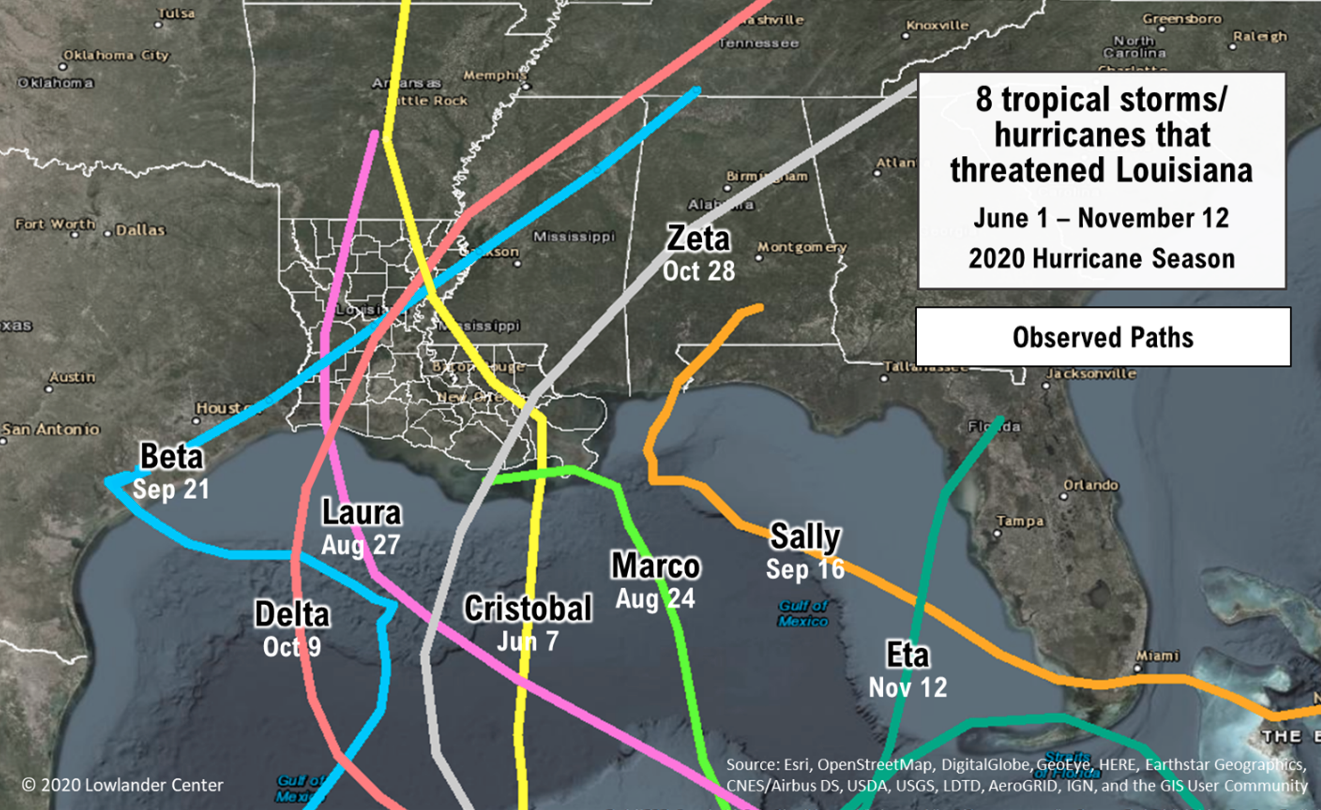

Over the 20th and 21st centuries, the area has been struck by multiple powerful hurricanesEndnote 3. Key to the selection of the area for study in this project is that eight tropical storms threatened Louisiana during the 2020 hurricane season, the most ever for Louisiana, and perhaps for any American state, a true “epidemic.” These eight events spanned five months plus a week of the 2020 hurricane season (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Observed Paths of 8 Hurricanes That Threatened Louisiana in 2020

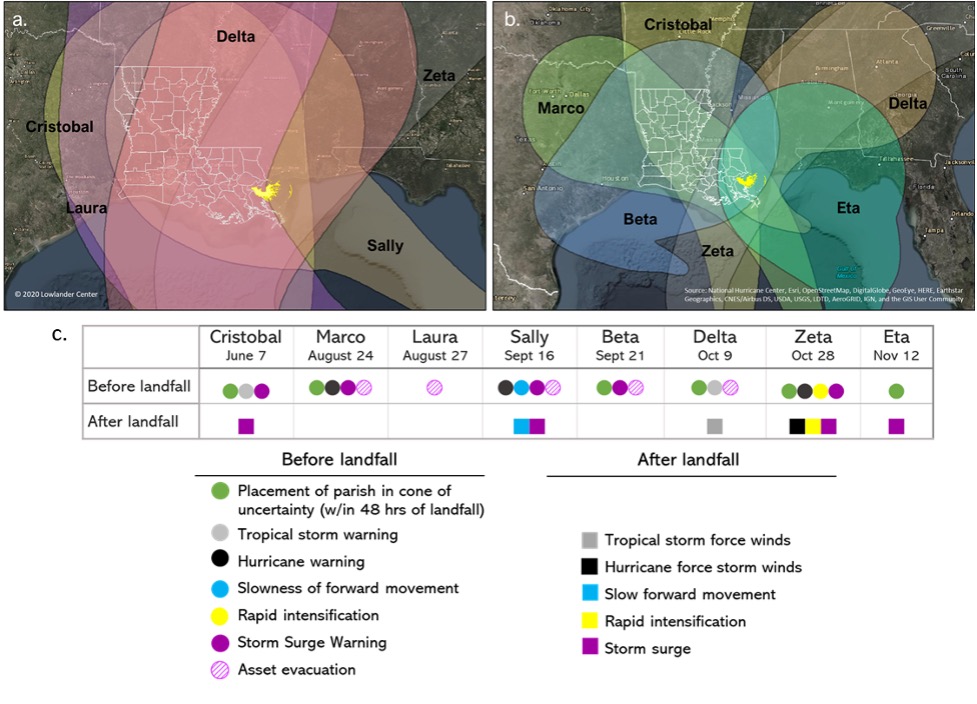

All of these storms had the cone of uncertainty (wrapped around the predicted eye location) covering part of Louisiana. Only one with the cone over Louisiana in its early stage, Eta, veered off to the northeast early in its progression. Another storm’s (Sally) surge damaged the Louisiana coast while not passing over the state.

Sample Size and Participants

Given the history of storm impact in the area, multiple members of the communities/parishes participate in the preparation, response to, and recovery from storms. To reflect the diversity of positions and government types involved in the response, six types of parish leaders were identified: (1) parish presidents, (2) parish emergency managers, (3) assistant emergency managers of large parishes, (4) levee board directors, (5) incorporated town mayor/levee managers, and (6) unincorporated Indigenous village leaders. In addition, we had the opportunity to interview a professional employee of the NWS and chose to do so because Louisiana government officials had so often discussed weather and its forecasting. Fourteen agreed to be interviewed. Researchers transcribed all interviews and collaborated in analysis utilizing an informal emergent coding process to identify key themes.

Data Collection and Analysis

The method used to collect data for this project was an interview guide with open-ended questions asked orally in a Zoom meeting that always included two of the researchers, Jerolleman and Laska, and lasted about an hour. The initial recording and draft transcription were discarded with only the approved final version of the interview retained.

We wanted respondents to tell us about the sensemaking that they went through with both COVID-19 and the multiple storms, as well as their being intertwined. We asked about whether their previous experiences informed this year’s response or if it was so new that their response stood separately from how they had responded to their responsibilities in the past. We requested that they “begin at the beginning” in describing their experiences with COVID-19. Again, the request was responded to without hesitation: what, when, their thinking, what they did initially, how they evolved, their response, what they thought would be the future of their government’s COVID-19 response. For the parish presidents, we asked the extent to which they played a role in their parish’s response. We also wanted to know how the COVID-19 response was impacted by the storms. This theme was complicated by the need to social distance while evacuating and sheltering. The management of the tension rendered all previous evacuation arrangements unusable without substantial changes.

A series of diagrams and maps were shared with the respondents before their interviews (see Figure 3); respondents were asked to have them available for their interviews. By utilizing the maps and tables described in the next session, respondents were asked to discuss their experiences with the weather. Reviewing all of the qualities on maps and tables acted as a review of the qualities of the event and made the responses more detailed and specific. It also permitted them to consider their weather assessment process and their faith/trust in the forecasting.

The final theme that was covered was to ask the respondent to assess the management experience that they had to go through, and because of that, what they would tell others who were going to assume similar roles or might have similar challenges. Just about every respondent conversed for an hour.

Figure 3. 2020 Hurricane Season - St. Bernard Parish

Positionality, Reciprocity, Ethical Considerations

Researchers Jerolleman and Laska have a long history, spanning decades, of working with officials in the study area. This long history of collaboration positions the researchers as trusted partners, and not solely as external researchers. Furthermore, research participants were interested in supporting similar officials and therefore pleased to have their experiences captured.

As previously described, transcripts were shared with respondents for any corrections, with only the approved final version of the interview retained. All efforts were made to preserve anonymity of responses and informed consent was obtained at the beginning of each interview. The researchers received an IRB exception from Jacksonville State University.

Findings

Using the approach of offering general topics to the respondents generated different replies from each of the respondents interviewed, but also generated remarkably common responses and themes. The result of this open approach in sum has been a confirmation from one to the next on the responses, both what happened and the officials’ assessment of the events and their responses; in other words, their sensemaking. Where the respondents differed was in particular experiences that their parish, their office, or they themselves had or created. Because of such findings, we feel confident in drawing findings-based recommendations. Finally, we considered which of the recommendations would be relevant to officials dealing with significant disasters, especially those that co-occurred. There are many more of these than one realizes “on first blush.”

Competency: Public Officials and Staffs Stretched to Growth by Co-Epidemics

It was not the intent of this study to explore the professional competency of the respondents. However, interviews revealed many dimensions of what competency meant to respondents: how it was acquired, how it was applied, how the interacting epidemics challenged respondents so as to enhance competency, and what respondents wanted to accomplish to improve their response capacity. There is no doubt that each of the respondents grew in capability with the requirement of managing the two epidemics concurrently, and that they recognized that. On its own, the occurrence of a global pandemic was new, and in the opinion of many, unprecedented. The combination of the pandemic with an “epidemic” of hurricane threats was even more novel. An emergency manager could not have gone through these experiences without changing for the better even if all of their responses were imperfect. Not a single respondent recalled being unable to carry out their responsibilities, or any hesitancy.

Those threats of most concern to them were the storm paths that past experience told them could be catastrophic; they did not—could not—know if and to what extent these storms would cause the most damage and destruction. Uncertainty of threat is definitely a quality of emergency responders’ role that makes the positions different from others with responsibility that is more predictable. The following are the experiences and challenges emergency officials confronted that built competency, both generally and specifically for prospective occurrences of the two epidemics and their co-occurrence in the future.

Relevant Experience Before Assuming Their Professional Role

Each of the respondents—parish presidents, emergency managers, mayors/community leaders, and levee board directors—had previous experience that they saw, and we saw, as relevant, but not all clearly directly related to disaster prevention/management. For example, a levee board director was an electrician before Hurricane Katrina. It is almost as if the variety of experiences they had, whether related to disasters or not, prepared them well for the positionsEndnote 4. In addition, up close exposure to the issues and the operations of the organization before taking leadership created a person qualified to lead it. It may also be that a position that has so many only partially anticipatable happenings and decisions requires such a complexity of exposure to different experiences as good preparation for assuming such a role.

Response to Each Novel Event Made Unique and More Complex by Co-Occurrence of the Two Epidemics

Blending the conditions of the current situation with earlier ones led to a response informed by previous challenges. Evolving capacity through the two epidemics strengthened the responses. However, the next hurricane season (2021) could return to more normal challenges. There was thus a hesitancy to overreact in terms of changing procedures when the challenges might be only temporary. There was no doubt that earlier experiences and their response to them formed the basis of officials’ responses. It was, however, when the current crisis began to demand more than had been demanded in the past that officials had to focus on a new solution to the current events.

Delay in After-Action Efforts

Every major disaster event is reviewed in an after-action meeting and a report. The respondents made reference to the use of this activity. Due to both the prohibitions of face-to-face meetings and the speed of the demands on emergency leaders and staffs from August to November, these activities had not appeared to have taken place per usual timing. Several respondents indicated that they would be scheduled in the future. If they never occur, this will mean a large gap in the data needed to assess the events and the governments’ responses in this double epidemic year and will likely reduce the quality of the exercises and the reports.

Revision Process of Emergency Plans

Despite emergency leaders’ and their staff’s commitment to and capacity for this key activity, the two epidemics could not have been any more coterminous at the usual time for this activity, mid-March, thus interfering with each parish’s pre-hurricane season review and amendment processes. While the Atlantic basin hurricane season begins officially June 1, since storms have been occurring in May—the first one in 2020 was May 17Endnote 5,—there was likely only a two-month time frame to review and to revise hurricane plans. This gave little flexibility to delay the hurricane plan review and to create a COVID-19 response plan. Yet both were challenged by time and know-how for the COVID-19 mitigation plan and for COVID-19 restraints in the hurricane response plan. Officials relied more on earlier plans, including Ebola and influenza plans, that had been developed some years ago.

Revising the Hurricane Response During the Season Due to Both Epidemics

Seven of the eight storms occurred within a 2.5 month time span. With this tight spread, each storm was not a standalone event as it was most often in a “regular” season. So many tropical events back-to-back revealed the efforts to be undertaken for each because the behaviors became unconsciously and consciously regularized. Also, respondents described how they came to be aware that preparation for previous storms could be left in place. That made the season easier despite the burden of there being so many storms, especially for parish employees. It is expected that more preparation for the first storm that threatens to impact a parish will be retained in place for the entire hurricane season in 2021 if it is possible to do soEndnote 6.

Coordination Across the Region

Emergency managers across the study area are a close-knit group with a long history of helping each other solve intractable problems. Not only did the officials have pre-existing relationships, and trust, but there were also coordination mechanisms, such as calls hosted by the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness (GOHSEP), that allowed for constant communication in the face of impending storm impacts.

Coordination with the Non-Profit Sector and Community Partners

Emergency managers across the study area also had pre-existing relationships with non-profits and community partners. These relationships were stronger in some parishes than in others. However, officials described improved relationships with non-profit and community partners through the process of providing information and resources in response to COVID-19. These relationships were then stronger—respondents used the word “tighter”—for hurricane season.

Evacuation and Sheltering

The confluence of simultaneous disaster events in 2020, particularly the occurrence of a tremendously active hurricane season while the COVID-19 pandemic was still ongoing, resulted in a series of challenges around sheltering and evacuation that government leaders and their emergency managers had to face. One immediate impact was the inability to undertake the normal annual pre-season activities of planning, exercising, and engaging with the public around preparedness. A second set of impacts involved evacuation, both in terms of the challenges in calling for an evacuation and in the ability to assist carless residents to do so—such as allowing more persons on buses than was safe. This concern came up when thinking about the challenges of evacuating a city such as New Orleans, which had absorbed a large number of evacuees from southwest Louisiana following Hurricane Laura due to a shift to non-congregate sheltering. As local officials evaluated alternatives to evacuation, one adaptive measure that was frequently considered, unlike for singular storm events, was to utilize in-parish facilities as shelters against what the state usually recommended.

Following Hurricane Laura, the decision by GOHSEP to use hotels in New Orleans for non-congregate sheltering reflected this adaptation towards case-specific sheltering south of I-10. Another reason that officials described for considering local sheltering was the concern that hurricanes are intensifying more rapidly than has traditionally been the case and that existing evacuation decision thresholds may not allow enough time to do so. The topic of evacuation was exposed and “exercised” in very useful ways due to the extreme challenges revealed in the 2020 season.

Communicating with the Public and Their Response: Social/TV Media and the Public’s “Competency” during Co-Epidemics

One assistant emergency manager recounted the change from four years ago to now when she was hired as the first (solo) public information officer (PIO) for that parish. Now she has a staff of four. This growth has been created to a great extent by the opportunities made available to communicate with the public via social media.

The PIO specialist was reminded of the “earlier times,” when one press conference per day was communication with the public. Now communication is continuous. Four methods of communicating with the public were discussed: (1) parish/community emergency websites, (2) alerts by parish/community through texts, (3) NWS storm information and forecasts, (4) social media, especially Facebook, and (5) network TV. There was agreement that the emergency management offices needed to pay attention to what was communicated, especially in cases where there is information being disseminated on social media that is contradictory to the NWS forecasts. The best solution was the continuous flow of official communications by the government emergency management office and the NWS.

The respondents’ assessment of the responsiveness of the public to the events and to varied forms of information was very informative for assessing the “competency” of the public in their response. The public values information about crises. People have signed up for those alerts that are made available to them (over 100,000 for hurricanes and 45,000 for COVID-19 in Orleans Parish). Findings from a survey conducted by the City of New Orleans about NOLA Ready and reported by one of the respondents in this research argued that the regular receipt of social media about tropical weather in previous years likely impacted the acceptance of social media communications about COVID-19. Building confidence in the medium built confidence in the information that was communicated across crises. This important finding has not been considered in discussion of how to be successful at communicating about the COVID-19 vaccine. Besides residents responding to forecasts as they came out of NWS, respondents discussed the qualities of broader communication by parishes. Respondents felt that government officials should emphasize to residents preparation, alertness to communication from officials, and response as advised. One interesting area of change that they recommended, and that seems to be already occurring, is that forecasters include not only the storm qualities but the impacts that the qualities will generate. For example, advising about serious wind speed is reinforced if officials already have equivalent damage to demonstrate; for example, “so much wind leads to so much tree damage which leads to so much roof and structure damage.” Respondents believe the storm qualities take on more meaning to residents in terms of their protective decisions if that equivalency is offered.

We have no direct measurements of the knowledge level or the competency of citizens with regard to COVID-19 and hurricanes. However, the number who subscribe to the city’s NOLA Ready system suggests an interest in relevant information. In addition, while there has been COVID-19 vaccine resistance in all of the parishes, none of the respondents indicated strong opposition. Orleans Parish has been noteworthy in the success of keeping COVID-19 under better control than most of the parishes in the state, despite it being the source of one of the first major outbreaks, with an estimate of 50,000 cases from Mardi Gras in 2020. That housing density is extreme with multi-generation cohabitation being common, as is poverty, the COVID-19 response is even more remarkable.

Descriptions of communications with the public regarding the hurricane threat focused on both the trust in the knowledge and experience of the public, as well as fears about complacency in the face of so many storms. However, most of the comments made by local officials focused much more on the idea that coastal residents know what is best for their own families and can consider factors such as whether they can withstand a power outage. One elected official described the importance of trust in both directions: “They have trust in their government and if you don’t have trust going back and forth both ways then, geez, I couldn’t imagine going through a crisis.”

Adaptation of Emergency Management Plans and Strategies

In addition to the adaptations around evacuation and sheltering described above, local officials also described having to adapt preparedness and response strategies to account for COVID-19 in many other ways. As one elected official stated, “There was no playbook for a global pandemic.” These adaptations centered primarily around learning virus protection procedures to be followed by emergency/disaster preparedness staffs and the communication of information and guidance to the public while hurricane response activities were simultaneously undertaken.

Weather “Behaved” Differently in Many Different Dimensions, Causing Challenging Responses

One storm struck early (Cristobal, June 7) and the other seven all occurred within a 2-month plus 2.5-week period at the middle/end of the season. Several other qualities of the storms were of interest and concern by the parish officials in addition to the total count. Officials wished for more information and explanation on rapid intensification, forward speed declining, and forward speed increasing, all three of which occurred during the storms’ passage across the Gulf of Mexico, with potential to be particularly dangerous and vexing at landfall. Intensification produced unanticipated wind speeds and slowing down resulted in heavier rainfall. The speed changes were manifested by storms before the 2020 season, but respondents were interested in whether there were changing patterns in these qualities. Was climate change making a difference, for example?

Services Provided

COVID-19 deeply challenged the way in which federal forecasting services developed their forecasts and interacted with parishes and communities to offer specific communications with local officials. Social distancing challenged the NWS concurrently with their being expected to achieve the most accurate forecasts possible during these circumstances, as sheltering and evacuation were so risky. Parish and community officials indicated that they looked at whatever was available on the internet about the storms, not just the official forecasts from the NWS. The NWS and the National Hurricane Center believe that they offer the best forecasts. Officials do not disagree; they just want as much ancillary information as they can get. The storm epidemic impacted officials’ ability to make successful decisions for their residents far more than did COVID-19; however, the latter should not be discounted because it played a role, especially with regard to evacuation considerations and sheltering decisions. Our research has left us with a strong level of respect for what coastal Louisiana officials have accomplished. Future research will benefit from the horrific experiences of southwest Louisiana. We did not feel that the time was right to interview parish officials in southwest Louisiana for this study. Time will allow them to tell their story.

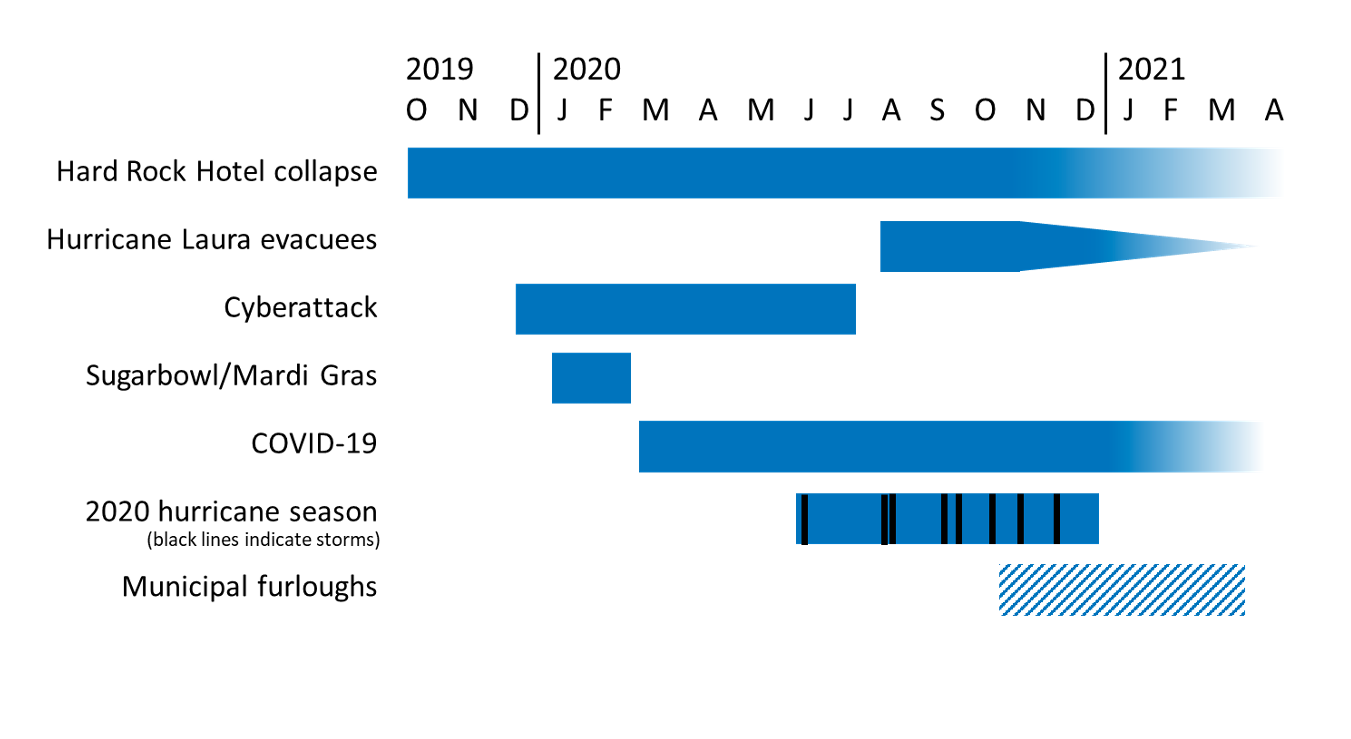

Staff Challenges

One key set of challenges involved local staffs themselves, as they navigated months of heightened activation levels due to a series of concurrent and successive disasters. The city of New Orleans, for example, remained at a heightened level of activation dating back to 2019 as a result of the building collapse at the Hard Rock site, followed by Mardi Gras and then COVID-19 (see Figure 4). Emergency managers were concerned about mental health impacts of the prolonged activations, including physical impacts from exhaustion. Also of concern were the direct impacts of cases among staff, as well as their families, coupled with the toll of the pandemic itself and additional work burdens. Officials were aware of these challenges, and frequently mentioned them in our interviews, but didn’t offer any solutions. Instead, they described a sort of stoicism, portraying an attitude of doing what needed to be done.

A further challenge was that these impacts were being felt while drastic cuts to local government budgets, coupled with the strain of COVID-19, were resulting in staff working while furloughed and without receiving any overtime pay for the declarations. One local emergency manager described this as insulting to the importance of the staff and detrimental to morale.

Figure 4. Overlapping New Orleans Emergency Events: October 2019 - Current

Conclusions

Key Findings

Coastal Louisiana parish (county) emergency responders drew from the experiences of a long legacy of responding to hurricanes and other crises such as inland storms, Mississippi River floods, and the BP oil spill. They engaged the threats of the pandemic and the storm “epidemic” with uncertainty but experience in dealing with the unknown. COVID-19 was more uncertain. It required much learning. The eight storm cones and their historical legacy of extremely uncertain and damaging impacts were considered on a sounder footing of experience and successful response. As the two collided, evacuation from the threat of the storms in a context of interpersonal contagion posed the most challenging undertaking to manage. Moving the evacuees of one storm into a coastal area at risk to storms was a risk-enhancing decision, but devoid of an alternative decision given the number who needed shelter in non-congregant facilities. The luck of the only storm passing over urban New Orleans moving rapidly and thus devoid of massive rain concluded the season with one area, southwest Louisiana, just gradually recovering and at the time of this report barely on the path to a return to normal. Increased communication for both COVID-19 and storms, officials’ trust of the public, and continuing support from NWS staff and emergency responders from across the area supported the area’s successful emergency disaster responses.

Implications for Practice

Implications for practice are integrated above within the findings as that was the key goal of the research. We believe that the nature of the challenges confronted by residents and government officials annually—when hurricane season hangs over the state for six months, extending earlier into May and officially to 6.5 months for the 2021 season—contributed to their capacity to respond capably to the novel situation of ever-changing storms within the context of COVID-19. Concomitantly, the Louisiana public has been “schooled” in crisis response from their perpetual history of hurricane threat and thus necessary assessment of risk and decisions about the appropriate response for themselves and their families. Within the collective identification of storms that go back as far as the “lost island” devastating storm of 1856 (Sallenger, 20098), Louisiana residents have been immersed in storm response behavior much more than any of us wants to acknowledge. That experience assisted the public in responding to COVID-19 and to multiple hurricanes within this unique hurricane season. Past experience truly benefitted the emergency managers and their citizens within this double crisis.

Dissemination of Findings

This report has been enlarged (by about double) and will be published by Emerald Press in the Jerolleman edited volume, Justice, Equity and Emergency Management, part of the Community, Environment, and Disaster Reduction Management series edited by Dr. Bill Waugh, forthcoming in 2022. In addition, the Natural Hazards Center’s URL for the report will be sent directly to the respondents and other officials who were invited to be interviewed. The Lowlander Center web page will also advertise the report and forward those who wish to read it to the Natural Hazards Center site.

In addition, conversations with respondents have revealed a collaboration opportunity that will be initiated at the beginning of the 2021 hurricane season: Applying the storm paths of the most serious storms to other parts of the coast to model what destruction would have occurred there. One of the officials offered the idea, identified those with whom he had spoken, and gave us permission to seek out other partners. As of this report’s submission, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has joined the team interested in pursuing this exercise. Other respondents, parish officials, and federal government professional staff will be sought to participate. The Lowlander Center, of which both Drs. Jerolleman and Laska are senior staff, will be an active co-lead.

Limitations

Challenges and time constraints related to the authors’ need to respond professionally to the two epidemics created a smaller scale research project than we might have preferred. This said, we were surprised and gratified as applied researchers that the observations we collected revealed how officials coped with the situation of a viral pandemic—not experienced since 1918—along with eight tropical storm cones across Louisiana, which had never been experienced by the state before. The story and its lessons for future pandemics and storm clusters emerged.

Future Research Directions

Phrasing the concluding remarks with a focus on the most important “layering” dynamics that we need to become better aware of is critical. Our research is based on the assumption that more serious crises will be generated by the climate conditions we acknowledged as we created this project and for which past experience has prepared coastal Louisianians. The effect of the response to one traumatic/dramatic event on the response to the next is an urgent consideration; in the 21st century, such multiple events may become the norm.

This conclusion leads to special consideration of the safety of the more vulnerable members of the parishes as so much more risk is introduced into the storm season, especially with the COVID-19 threat. Evacuations that are constrained by the need to achieve social distance between residents who are sharing transportation to shelters inland from the coast, and which then must consider social distancing of occupants within shelters, are issues that are fraught with social justice challenges. Concurrently, there is significant risk to placing evacuees into hotels in cities near the coast if an evacuation is needed for an impending hurricane.

Similarly, if changes are made to place evacuation facilities closer to the coast, those who likely will need such shelters will be those who are more economically challenged. They will be more at risk to an unexpectedly powerful storm. The tension of the challenges for safety of those who need some of these public actions can never be ignored, nor can the responsibility to make the safest decisions that weigh upon the parish leaders. We did not hear them ignoring these obligations; we did hear the uncertainties of the benefits going forward for changing from the actions taken before 2020 to new ones. Remembering the challenges and considered solutions of this remarkably risky year in addressing the most at-risk residents must occur in spite of the challenges of doing so with very little time available to deliberatively consider them as COVID-19 continues and even as there has only been a short period to anticipate the next hurricane season. Herd immunity must be the state’s goal to reduce the risk of the hurricane response for those most economically at risk.

It is a responsible commitment for us, the co-authors of this research, to follow up with these parish leaders after the 2021 hurricane season if it evolves into another challenging one, especially if COVID-19 continues to be a threat, to learn what decisions were made and how the parish leaders evolved in their decision-making to achieve safety for all of their residents.

Endnotes

Endnote 1: Surprisingly, one similar event to this August’s confluence of events was the landing of the “Louisiana Hurricane of 1918” in Cameron Parish, during the influenza pandemic of that year (Roth, 2010).↩

Endnote 2: The most damaging of the 2020 storms–Hurricanes Laura and Delta–struck southwest coastal Louisiana as did the Artic ice storm. Due to the magnitude of the area’s damage and destruction, the research team decided not to interview officials there because of the incredible challenge they are facing to recover.↩

Endnote 3: Audrey 1957, Betsy 1965, Camille 1969, Andrew 1992, Katrina 2005, Rita 2005, Gustav 2008, Ike 2008, Isaac 2012.↩

Endnote 4: Experience by author Laska interacting with Alaskan community public officials suggested a professional cadre who took leadership positions in various segments of the community’s structure rather than remaining within one profession for the duration of their work career. In Alaska that might be influenced by a paucity of residents within the small communities.↩

Endnote 5: Due to the earlier arrival of the first storms, a step recognizing this is being taken in 2021 and it is proposed that the official season be advanced to May 15th in 2022.↩

Endnote 6: The revisions to the plans due to the co-occurrence of the two pandemics will be reviewed in the next section on Evacuation and Sheltering.↩

Referenes

-

Norwood, N. (2020, September 2). Laura a reminder New Orleans has not seen winds as strong in at least a century. Fox 8-WVUE. https://www.fox8live.com/2020/09/02/laura-reminder-new-orleans-has-not-seen-winds-strong-least-century/ ↩

-

Takeda, M., Jones, R., & Helms, M. M. (2017). Promoting sense-making in volatile environments: Developing resilience in disaster management. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(8), 791-805. doi:10.1080/10911359.2017.1338173 ↩

-

Laska, S., Peterson, K., Rodrigue, C., Cosse, T., Philippe, R., Burchett, O., & Krajeski, R. (2015). “Layering” of natural and human caused disasters in the context of anticipated climate change disasters: The coastal Louisiana experience. In M. Companion, (Ed.), The Impact of Disasters on Livelihoods and Cultural survival: Opportunities, Losses and Mitigation (pp. 225-238. Taylor and Francis (CRC Press). ↩

-

Lombrozo, T. (2012). Explanation and abductive inference. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), Oxford Library of Psychology. The Oxford handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 260–276). Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Mendonca, D., Beroggi, G. E., & Wallace, W. A. (2001). Decision support for improvisation during emergency response operations. International journal of emergency management, 1(1), 30-38. doi: 10.1504/IJEM.2001.000507 ↩

-

Fairchild, A. L., Colgrove, J., & Jones, M. M. (2006). The challenge of mandatory evacuation: Providing for and deciding for. Health Affairs, 25(4), 958-967. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.958 ↩

-

Haines, B. & Wood, L. (2010, January 17-20). Hurricane Ike: User response and effectiveness of NWS forecast products Conference presentation abstract. Fifth Symposium on Policy and Socio-economic Research, GA, United States. https://ams.confex.com/ams/90annual/techprogram/paper_163176.htm ↩

-

Sallenger, A. (2009) Island in a storm: A rising sea, a vanishing coast, and a nineteenth-century disaster that warns of a warmer world. PublicAffairs. ↩

Jerolleman, A., Laska, S., & Torres, J. (2021). Lessons from Co-Occurring Disasters: COVID-19 and Eight Hurricanes (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 327). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/lessons-from-co-occurring-disasters