Overcoming COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Black Communities

Less Fear, More Hope

Publication Date: 2021

Abstract

Extensive COVID-19 research conducted before vaccine development found strong vaccine hesitancy in Black communities. At the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, this study revisited vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans and explored the cognitive mechanisms underlying decisions to receive the vaccine. Our study, which surveyed Black Americans in January 2021, showed continued lack of willingness to receive a vaccine. Despite our three treatments designed to elevate subjects’ fear of COVID-19 morbidity, the COVID-19 vaccine, and both threats simultaneously, those manipulations produced no significant effect on subjects’ intention to get vaccinated. Neither did they appreciably influence subject concerns about unknown risks, side effects, or the novelty of the COVID-19 vaccine. However, when incorporating individuals perceptions about COVID-19 vaccine efficacy, we found individuals with higher perceptions of vaccine efficacy consistently indicated stronger vaccination intentions across all four experimental groups. These perceptions were most pronounced when individuals were confronted with information designed to increase their fear of both the disease and the vaccine. In the context of growing overall acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine, this study points to a targeted approach in addressing disparities in vaccination intentions across racial and ethnic groups. Particularly, it suggests an alternative approach to promoting COVID-19 vaccination uptake by replacing fear appeals with interventions to raise perceptions about the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines.

Introduction and Literature Review

Long-term control of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic and return to normalcy is pinned on large-scale uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine. A sizeable portion of the population of the United States, ranging from 25% to 40%, has reported refusal or reluctance to get a vaccine (Callaghan et al., 20211; Malik et al., 20202; Neergaard & Fingerhut, 20203). With half of Americans inoculated with at least one dose of the vaccine in May 2021, the country was experiencing its first slowdown in daily vaccination rates across states, casting doubt on reaching herd immunity (Mandavilli, 20214). Public authorities are increasingly grappling with the challenges of devising new and creative ways to encourage vaccination, offering “beers, bucks, and bonuses” (Swanson, 20215) as incentives.

Unwillingness to receive a vaccine is unevenly distributed across ethnic and racial groups. Abundant evidence shows that vaccine hesitancy is especially strong in Black communities as a consequence of structural disadvantage and historical injustice (Callaghan et al., 2021; COVID Collaborative et al., 20206). In light of this strong hesitancy, inoculation rates may not reach the threshold needed to prevent coronavirus from spreading quickly and easily in Black communities. In the meantime, this group bears disproportionate impacts from COVID-19 as a result of pre-existing health conditions and employment in essential jobs during the pandemic (Platt & Warwick, 20207; Wright & Merritt, 20208). As of April 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that Black Americans are 1.1 times more likely to contract COVID-19, 2.8 times more likely to be hospitalized, and 1.9 times more likely to die from the disease than White, non-Hispanic Americans (CDC, 2021b9). Identifying and understanding psychological factors underlying vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans is of the utmost importance in designing and implementing tailored interventions to protect this population and narrow COVID-19-induced disparities.

We drew on theories of fear appeals (i.e., persuasive messaging that uses fear to evoke a desired response) to distinguish two separate and independent cognitive processes individuals have when facing a potential threat (Rogers, 197510; Witte, 199611; Witte & Allen, 200012): (a) threat appraisal, defined as an individual’s subjective assessment of the probability of the threat and the potential damage caused if no mitigation measures are taken; and (b) coping appraisal, which reflects one’s evaluation of their ability to exercise control and avert the threat. Protective behavioral change, such as intending to get a vaccine, is possible when individuals believe that the health threat is severe and that they can successfully control the danger. Low threat appraisal usually leads to complacency toward the threat, whereas low vaccine efficacy appraisal can cause maladaptive emotional response through risk denial, passivity, and fatalism.

When it comes to COVID-19, individuals can simultaneously hold fear for the disease and the vaccine (Karlsson et al., 202013). Using an online survey experiment conducted with 547 Black Americans in January 2021, our project sought to answer two main questions:

- What is the current level of vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans?

- How do perceived risks and perceived vaccine efficacy influence uptake intentions?

Methods and Procedures

We contracted with Qualtrics to collect a nationally representative sample of between 500 and 600 Black American adults. Qualtrics uses a non-probability, quota-based sampling procedure to sample subjects from a variety of pre-existing panels. In a quota-based sampling procedure, subjects are sampled from within certain quota groups (e.g., age, gender, region) until a sample that roughly mirrors the population of interest is obtained. We gathered complete data for 547 participants.

We designed a between-subjects survey experiment with three treatment groups and a control group. The survey experiment was conducted January 14-15, 2021, before widespread distribution of COVID-19 vaccine in the United States. For context, the Washington Post vaccine tracker (Washington Post, 202114) indicated on January 14, 2021 that 3.4% of the U.S. population had received at least one dose of an approved vaccine. Our sample included only Black American adults who had not received a dose of a COVID-19 vaccine at the time of the survey experiment. We positioned all experimental treatments—blocks of text containing either COVID-19 mortality information, COVID-19 vaccine side effect information, or both types of information—at the very beginning of the survey to avoid distraction, contextualization, or signals from other survey questions. Survey questions included demographic questions, questions about subjects’ worries about contracting COVID-19, and other questions aimed at gleaning information about subjects’ COVID-19-related attitudes.

Treatment 1, which we will call our Mortality Treatment Group, aimed to induce fear of COVID-19 by providing contemporaneous, factual COVID-19 infection counts, hospitalization counts, and death counts. Additionally, this treatment emphasized that Black Americans are more likely to be infected by, to be hospitalized by, and to die from COVID-19 than White Americans. The treatment aimed to present this information in a form that was easy to process and impactful, so that the desired response of fear arousal was produced in subjects. All information presented in the treatment text was publicly available at the time of the survey experiment (CDC, 2021a15). The treatment text appears verbatim below.

Mortality Treatment Text

Please read the following information about COVID-19 carefully:

Infections, hospitalizations, and deaths:

As of January 14, 2021, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate the following: 22,538,426 Americans have been infected with COVID-19. A total of 131,326 Americans are currently hospitalized because of COVID-19. In total, 371,449 Americans have died from COVID-19. In the first 10 days of this month, the country has recorded some 2.35 million COVID-19 cases and more than 28,000 deaths from the disease. That works out to be around 163 Americans diagnosed with COVID-19 every minute, and approximately one American death from the disease reported every 30 seconds. When compared with White Americans, African Americans are 1.4 times more likely to contract COVID-19, 3.7 times more likely to be hospitalized and 2.8 times more likely to die from COVID-19.

Treatment 2, which we will call our Side Effect Treatment Group, aimed to induce fear about COVID-19 vaccine side effects by providing contemporaneous, factual information about them. All of the information presented in the second treatment text was publicly available at the time of the survey experiment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). Indeed, misinformation exaggerating the frequency and severity of COVID-19 vaccine side effects was in widespread circulation when the survey was fielded and continues to be in widespread circulation (Hotez et al., 202116). The purpose of our Side Effect treatment was to assess how subjects respond to true, though out of context and potentially anxiety-inducing, information about COVID-19 vaccine effects. Given that the goal of misinformation is often to scare individuals into forgoing COVID-19 vaccination, it is important to assess how individuals respond to real, factual information about the vaccine’s side effects. The treatment text appears verbatim below.

Side Effect Treatment Text

Please read the following information about COVID-19 carefully:

Vaccine side effects:

As of January 14, 2021, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate the following: 16,129 instances of individuals have experienced side effects from a COVID-19 vaccine. Among the most common of these side effects are headache (836 individuals), dizziness (679), and chills (510). Of the 16,129 instances of individuals experiencing side effects, 1,008 have been serious side effects. Among the most common serious side effects are difficulty breathing (33), heart palpitations (17), and chest discomfort (13).

Treatment 3, which we will call our Dual Treatment Group, included contemporaneous, factual information about COVID-19 infection counts, hospitalization counts, and death counts, as well as COVID-19 vaccine side effects. The purpose of this treatment was to simultaneously induce a fear response regarding COVID-19 health effects and a fear response regarding COVID-19 vaccine side effects. We were interested in learning which of these responses would win out. The third treatment text, which combined the above two treatments, appears verbatim below.

Dual Treatment Text

Please read the following information about COVID-19 carefully:

Vaccine side effects:

As of January 14, 2021, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate the following: 16,129 instances of individuals have experienced side effects from a COVID-19 vaccine. Among the most common of these side effects are headache (836 individuals), dizziness (679), and chills (510). Of the 16,129 instances of individuals experiencing side effects, 1,008 have been serious side effects. Among the most common serious side effects are difficulty breathing (33), heart palpitations (17), and chest discomfort (13).

Infections, hospitalizations, and deaths:

As of January 14, 2021, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate the following: 22,538,426 Americans have been infected with COVID-19. A total of 131,326 Americans are currently hospitalized because of COVID-19. In total, 371,449 Americans have died from COVID-19. In the first 10 days of this month, the country has recorded some 2.35 million COVID-19 cases and more than 28,000 deaths from the disease. That works out to be around 163 Americans diagnosed with COVID-19 every minute, and approximately one American death from the disease reported every 30 seconds. When compared with White Americans, African-Americans are 1.4 times more likely to contract COVID-19, 3.7 times more likely to be hospitalized and 2.8 times more likely to die from COVID-19.

Immediately after reading the treatment text to which they were assigned, subjects answered the following question about their COVID-19 vaccination plans:

When a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available to you, easily accessible and free of charge, how likely is it that you will get one?

Subjects chose one of the following response options: (1) very unlikely, (2) unlikely, (3) slightly unlikely, (4) neither likely nor unlikely, (5) slightly likely, (6) likely, or (7) very likely. As the response options show, higher scores on this question would indicate a stronger intention to get vaccinated.

Subjects in our control group received no information about COVID-19 health effects or COVID-19 vaccine side effects before responding to the above question. There were 147 subjects in our Side Effects Treatment Group, 150 subjects in our Mortality Treatment Group, 126 subjects in our Dual Treatment Group, and 124 subjects in our control group.

Data Analysis and Results

Table 1 presents the frequency distribution of expressed intentions for getting a vaccine.

Table 1. Vaccine Uptake Intentions by Total Population

| Frequency | Percentage | |

| Very Unlikely | 115 | 21.0 |

| Unlikely | 44 | 8.0 |

| Slightly Unlikely | 26 | 4.8 |

| Neither Likely Nor Unlikely | 100 | 18.3 |

| Slightly Likely | 80 | 14.6 |

| Likely | 75 | 13.7 |

| Very Likely | 107 | 19.6 |

| N=547 |

Survey Question: "When a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available to you, easily accessible and free of charge, how likely is it that you will get one?"

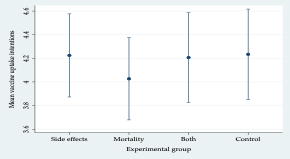

Figure 1 shows the mean vaccine uptake intentions among our three experimental groups and our control group (means are calculated across all seven response options). We expected that giving subjects information about COVID-19 vaccine side effects would reduce their vaccination intentions relative to the control group. Similarly, we thought that giving subjects COVID-19 mortality information would increase their intentions to be vaccinated and that giving them information about both side effects and mortality would present individuals with a double hazard (i.e. dangers of COVID-19 and dangers of the vaccination), with an indeterminate effect on vaccination intentions. All four means were very similar, ranging from about four to just more than 4.2. Moreover, the 95% confidence intervals overlapped considerably. These results suggest that providing Black American individuals with information about COVID-19 vaccine side effects would not appreciably lower their vaccine uptake intentions. Similarly, providing respondents with information about COVID-19 mortality did not meaningfully increase their vaccination intentions.

Figure 1. Mean Vaccine Uptake Intention

In addition to the vaccine uptake intention survey question, we also asked subjects a series of questions to determine their anxieties about getting a COVID-19 vaccine. Subjects were asked to indicate the degree of their level of agreement or disagreement with the following three statements using a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree):

- I am worried about experiencing side effects from COVID-19 vaccination.

- There are unknown risks associated with COVID-19 vaccination.

- COVID-19 vaccines are too new for me to feel confident about getting one.

We expected that subjects assigned to the side effects treatment would express higher levels of skepticism and anxiety about a COVID-19 vaccine, and so anticipated higher levels of agreement on each of these items among those subjects.

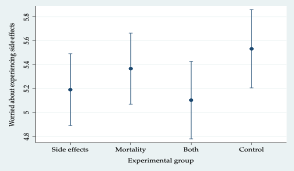

The mean level of worry about experiencing COVID-19 vaccine side effects by the three experimental groups and control group is shown in Figure 2. Contrary to our expectations, the mean among the subjects assigned to the side effects group was lower than the mean worry among control subjects. More generally, we noted that the group means were quite similar in magnitude and that their confidence intervals overlapped considerably.

Figure 2. Mean Worry About Side Effects

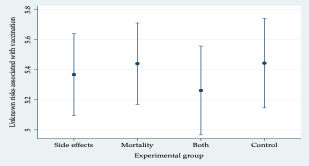

Figure 3 shows mean levels of agreement with the statement that there are unknown risks associated with COVID-19 vaccination by the three experimental groups and control group. Once again, contrary to our expectation, the perception that there could be unknown vaccine risks was lower among the side effects treatment subjects than among control subjects. The four group means were similar in magnitude and their confidence intervals overlapped considerably.

Figure 3. Perception of Unknown COVID-19 Vaccines Risk

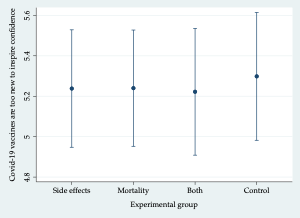

Figure 4 shows the group mean levels of agreement with the statement that COVID-19 vaccines are too new for subjects to have confidence in them. Yet again, anxiety about vaccination was lower among the side effects treatment subjects than among control subjects. We again note that the four group means were quite similar in magnitude and that their confidence intervals overlapped considerably.

Figure 4. Lack of Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines Based on Novelty

Taken together, these three figures suggest that the information treatments did not have an appreciable effect on the measure of subject concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine in terms of its side effects, unknown risks, or novelty.

As an additional piece of analysis, we examined whether and how perceptions about vaccine efficacy might influence subject vaccine uptake intentions. We asked subjects about their level of agreement with three seven-point scale questions to get at the strength of these perceptions:

I believe a COVID-19 vaccine can effectively protect me from the coronavirus.

Regarding COVID-19 vaccines, I am confident that public authorities make decisions that are in the best interest of citizens.

- A vaccine is important to ending the COVID-19 pandemic.

We used principal component analysis to create a factor score for each subject. Since perceived vaccine efficacy is a cognitive process parallel to risk appraisal to affect protective behavior (Rogers, 1975; Witte & Allen, 2000), we estimated a linear regression in which vaccine uptake intention was the dependent variable and group assignment, perceived vaccine efficacy, and their interaction were independent variables. Note that, although not shown in the results, this model also included a suite of control variables, including age, gender, party identification (Democrat, Republican, Independent, other), political ideology (far left, liberal/progressive, middle of the road, conservative, far right), and education level.

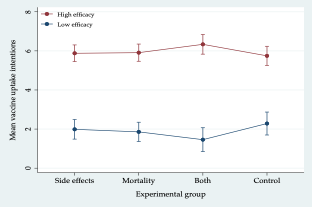

Figure 5 presents the estimated mean of vaccine uptake for individuals perceiving low and high vaccine efficacy by experimental group. Marginal means for those perceiving low vaccine efficacy were computed by setting subject efficacy perceptions to the 10th percentile value of the subject. Marginal means for those perceiving high vaccine efficacy were computed by setting subject efficacy perceptions to the 90th percentile value of the sample.

Figure 5. Mean Vaccine Uptake Intention by Efficacy

Two things merit attention. First, as shown in Figure 5, uptake intentions were higher when efficacy perceptions were higher in all four groups. Second, efficacy interacted with the dual treatment, that is, the treatment in which subjects received information about COVID-19 vaccine side effects and COVID-19 adverse health outcomes. Note the downward sloping line connecting the dual group to the control group when efficacy is high (red line). By contrast, the line connecting the dual group to the control group is upward sloping when efficacy is low (blue line).

When efficacy is high, receiving information about COVID-19 vaccine side effects and COVID-19 mortality increased vaccine uptake intentions relative to the control group. This suggests that perceptions about vaccine efficacy spur individuals toward vaccination when they are pulled in opposite directions by competing threats. When efficacy is low, receiving information about COVID-19 side effects and COVID-19 mortality decreases subject uptake intentions relative to the control group. This interaction effect is statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Key Findings

Although many Americans have received the COVID-19 vaccine, vaccine hesitancy a notably limiting factor for reaching herd immunity. The problem is made more severe by the disproportionally strong hesitancy in Black communities, which can be partly attributed to systemic disenfranchisement and resulting mistrust in public health systems (Latkin et al., 202117). Using a national survey conducted at the outset of vaccine rollout, our study confirms considerable vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans. Despite the increase in vaccine acceptance in the broader population (Brenan, 202018; Funk & Tyson, 202019; Hamel et al., 202020), the continued strong hesitancy among Black communities signifies the importance of examining and targeting the underlying heterogeneity across various ethnic and racial groups.

While a targeted approach using different interventions for different segments of the population is well recognized in public health practices (French et al., 202021), our study suggests an alternative approach to communicating and engaging with the targeted communities. Our three experimental treatments, designed to raise fear about COVID-19, vaccine side effects, and both combined, do not produce significant variations in subject willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Nor do they appreciably influence subject concerns about the side effects, unknown risks, or the novelty of the COVID-19 vaccine. The null effects of the fear appeals were surprising, given the extensive evidence showing that perceptions of COVID-19 risks are a key motivator for individual adoption and continuous engagement in protective health behavior (Cori et al., 202022; Reiter et al., 202023; Ruiz & Bell, 202124). A closer look at the timing of the study and fear appeal theories suggests an explanation. After a year-long exposure to COVID-19, people have formed and progressively reinforced their view of COVID-19 risks to such a point that they might be no longer sensitive to additional information about the morbidity of the disease. The fatigue and anxiety individuals face in a seemingly endless battle with COVID-19 offers substantial potential for efficacy-raising interventions. People who are eager to return to normal may become willing to overlook information about COVID-19 vaccine side effects—or the side effects themselves—if they believe the vaccine offers a means to ending the pandemic. This is evident from our findings that people who believe in the efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine express consistently stronger vaccination intentions across all the experimental groups, with a particularly pronounced effect when subjects are pulled in opposite directions by fear appeals about the two competing threats.

Implications for Practice

Although fear appeals can be crucial in overcoming complacency in the short term, prolonged and heightened fear can backfire, causing avoidance and detachment (Chou & Budenz, 202025; Jankó, 2020). As individual reactions to COVID-19 are more indicative of fatigue and burnout than complacency, the attitudinal shift requires a corresponding shift in vaccination promotion strategies. Instead of focusing on risks and fear, it is critical that “fear regimes should be replaced with regimes of hope” (Jankó, 202026, p. 310) in future risk communication and community engagement. Successful implementation of an efficacy-oriented approach requires public authorities and public health practitioners to identify interventions with sufficient leverage to bolster perceptions of confidence in the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines. These efforts can benefit from prior literature that demonstrates the importance of framing, social networks, communication channels, and the identity of the messenger (Morrow, 200927). For instance, Chou and Budenz (2020) recommend framing vaccination as effective and safe to encourage vaccine acceptance. The way in which messages are framed, packaged, and delivered to Black communities, along with many other ethnic and racial groups, is an important direction for future research. Future practice and research could experiment with various communication and engagement strategies by altering the identity of the messenger or communication channels. We plan to share our findings and insights with practitioners and researchers via popular media, conferences, and journals to promote an efficacy orientation to COVID-19 vaccine uptake promotion strategies, and to help identify context- and audience-specific intervention strategies.

References

-

Callaghan, T., Moghtaderi, A., Lueck, J. A., Hotez, P., Strych, U., Dor, A., Fowler, E. F., & Motta, M. (2021). Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Social Science & Medicine, 113638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113638 ↩

-

Malik, A. A., McFadden, S. M., Elharake, J., & Omer, S. B. (2020). Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine, 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495 ↩

-

Neergaard, L., & Fingerhut, H. (2020, December 11). AP-NORC poll: Half of Americans would get a COVID-19 vaccine. Associated Press-University of Chicago National Opinion Research Center. https://apnorc.org/ap-norc-poll-half-of-americans-would-get-a-covid-19-vaccine/ ↩

-

Mandavilli, A. (2021, May 3). Reaching ‘Herd Immunity’ Is Unlikely in the U.S., Experts Now Believe. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/03/health/covid-herd-immunity-vaccine.html ↩

-

Swanson, I. (2021, May 3). Beers, bucks and bonuses: States get creative to encourage vaccinations.The Hill. https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/551568-beers-bucks-and-bonuses-states-get-creative-to-encourage-vaccinations ↩

-

COVID Collaborative, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, & UnidosUS. (2020). Coronavirus Vaccine Hesitancy in Black and Latinx Communities. https://www.covidcollaborative.us/content/vaccine-treatments/coronavirus-vaccine-hesitancy-in-black-and-latinx-communities ↩

-

Platt, L., & Warwick, R. (2020). Are some ethnic groups more vulnerable to COVID-19 than others. Institute for Fiscal Studies, 1. ↩

-

Wright, J. E., & Merritt, C. C. (2020). Social Equity and COVID-19: The Case of African Americans. Public Administration Review. ↩

-

CDC. (2021b, April 23). Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html ↩

-

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. The Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 93–114. ↩

-

Witte, K. (1996). Fear as motivator, fear as inhibitor: Using the extended parallel process model to explain fear appeal successes and failures. In P. A. Andersen & L. K. Guerrero (Eds.), Handbook of Communication and Emotion (pp. 423–450). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012057770-5/50018-7 ↩

-

Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27(5), 591–615. ↩

-

Karlsson, L. C., Soveri, A., Lewandowsky, S., Karlsson, L., Karlsson, H., Nolvi, S., Karukivi, M., Lindfelt, M., & Antfolk, J. (2020). Fearing the Disease or the Vaccine: The Case of COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences, 110590. ↩

-

Washington Post. (2021). Washington Post COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/health/covid-vaccine-states-distribution-doses/ ↩

-

CDC. (2021a). COVID Data Tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker ↩

-

Hotez, P., Batista, C., Ergonul, O., Figueroa, J. P., Gilbert, S., Gursel, M., Hassanain, M., Kang, G., Kim, J. H., & Lall, B. (2021). Correcting COVID-19 vaccine misinformation: Lancet Commission on COVID-19 Vaccines and Therapeutics Task Force Members. EClinicalMedicine, 33. ↩

-

Latkin, C. A., Dayton, L., Yi, G., Konstantopoulos, A., & Boodram, B. (2021). Trust in a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S.: A social-ecological perspective. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 270, 113684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113684 ↩

-

Brenan, M. (2020, December 8). Willingness to Get COVID-19 Vaccine Ticks Up to 63% in U.S. Gallup. http://news.gallup.com/poll/327425/willingness-covid-vaccine-ticks.aspx ↩

-

Funk, C., & Tyson, A. (2020). Intent to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine Rises to 60% as Confidence in Research and Development Process Increases. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/12/03/intent-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-rises-to-60-as-confidence-in-research-and-development-process-increases/ ↩

-

Hamel, L., Kirzinger, A., Munana, C., & Brodie, M. (2020). KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020/ ↩

-

French, J., Deshpande, S., Evans, W., & Obregon, R. (2020). Key guidelines in developing a pre-emptive COVID-19 vaccination uptake promotion strategy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5893. ↩

-

Cori, L., Bianchi, F., Cadum, E., & Anthonj, C. (2020). Risk perception and COVID-19. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. ↩

-

Reiter, P. L., Pennell, M. L., & Katz, M. L. (2020). Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine, 38(42), 6500–6507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043 ↩

-

Ruiz, J. B., & Bell, R. A. (2021). Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010 ↩

-

Chou, W.-Y. S., & Budenz, A. (2020). Considering Emotion in COVID-19 vaccine communication: Addressing vaccine hesitancy and fostering vaccine confidence. Health Communication, 35(14), 1718–1722. ↩

-

Jankó, F. (2020). Fear regimes: Comparing climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic. Geoforum, 117, 308–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.09.023 ↩

-

Morrow, B. H. (2009). Risk behavior and risk communication: Synthesis and expert interviews. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. ↩

Zhang, F. & Marvel, J. (2021) Overcoming COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Black Communities: Less Fear, More Hope (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 331). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/overcoming-covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-in-black-communities