¡Puerto Rico Se Levanta!

Hurricane Maria and Narratives of Struggle, Resilience, and Migration

Publication Date: 2018

Abstract

Hurricane Maria, a Category 4 storm, ravaged Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017. All regions of the island were affected, given Maria’s trajectory and magnitude. The storm flooded island communities, thousands of houses endured structural damage or were completely destroyed, and the storm devastated the island’s infrastructure. Island residents lacked access to public services and everyday essentials for months, including food, potable water, and adequate medical services. Florida has become Puerto Ricans’ primary mainland destination in recent decades, and the state has attracted the largest proportion of Hurricane Maria evacuees. This study draws on resiliency and migration models to analyze the experiences of Puerto Ricans displaced by Hurricane Maria. Data for this research come from 17 in-depth interviews and observations conducted in the Orlando metropolitan area from December 2017 through January 2018. The research examines how respondents and their families experienced Hurricane Maria and relief efforts, the survival strategies they deployed after the storm, their migration decision-making and journeys to Florida, and their interpretations of governmental response to the hurricane. This study demonstrates how populations with unequal political and territorial status experience a natural disaster, engage in recovery behavior, and experience displacement. The report concludes with policy recommendations for addressing the housing, employment, and healthcare needs of Hurricane Maria evacuees in Florida.

Background

On September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria—a Category 4 storm—ravaged Puerto Rico. Hurricane Maria arrived less than two weeks after Hurricane Irma, a storm that brought heavy rain, toppled trees, and left over 1 million Puerto Ricans without energy. Hurricane Maria is the most catastrophic storm to impact Puerto Rico in nearly a century (Centro 20181). Maria made landfall on the island’s southeastern coast with winds of 155 miles per hour, and it exited through the island’s northwest coast as a Category 3 storm (National Hurricane Center 20172). Because of the storm’s magnitude and trajectory, all regions of the island were affected. Maria flooded many island communities, some to waist-deep levels, while others were affected by mud slides that uprooted homes, trees, and roads. Thousands of houses endured structural damage or were completely destroyed. Various communities were rendered inaccessible given the damages to the island’s infrastructure, with those located in rural and interior areas most affected. Moreover, Puerto Rico’s archaic power grid was destroyed, leaving all 3.4 million island residents without power. Many also lacked access to basic necessities, including food, safe water, and shelter.

One month after Hurricane Maria, conditions on the island remained dire. Eighty percent of island residents did not have electricity. Almost 40 percent of islanders lacked access to telecommunications, as nearly half of all damaged cell phone towers required restoration (StatusPR 20173). Access to potable water continued to be a critical issue four weeks after Hurricane Maria, with almost 1 million Puerto Ricans lacking safe drinking water. Journalistic reports documented desperate island residents collecting water from contaminated creeks, and soon after health issues surfaced, adding to concerns of an outbreak of waterborne diseases (Sutter 20174). Health issues were compounded by limited access to medical services in Puerto Rico (StatusPR 2017). A slow response by the federal government and logistical coordination issues with the Puerto Rico government critically exacerbated the effects of the storm.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) predicts that it will take years to rebuild Puerto Rico. Early economic analyses estimated that Hurricane Maria would cost Puerto Rico between $45–$95 billion dollars (Friedman 20175), and others estimate the storm will produce a loss of $180 billion in economic output in Puerto Rico over the next fifteen years (Centro 2018). These economic forecasts add to already dire economic conditions on the island, most notably, a decade-long recession, high levels of unemployment and underemployment, a looming $72 billion debt, and severe austerity measures. Existing economic and social conditions in Puerto Rico had previously set in motion a massive exodus—in the past ten years, over 400,000 Puerto Ricans left the island, a migration wave comparable to the Puerto Rican “Great Migration” of the 1950s. In the last three decades, Florida has become Puerto Ricans’ primary migration destination. In fact, the Puerto Rican population in Florida surpasses 1 million and is now the largest stateside (ACS 2017).

The devastation caused by the natural disaster and Puerto Rico’s ominous future prompted Puerto Ricans to leave the Island for the mainland within weeks after the hurricane. Given the rise of Florida as Puerto Ricans’ new and leading mainland destination, the state attracted the largest proportion of those who fled the island (Centro 2018). Officials in Florida expected the arrival of at least 100,000 Puerto Ricans, and in anticipation of this influx, Florida Governor Rick Scott declared a “state of emergency” two weeks after the storm to enable state agencies to prepare for the arrival of Puerto Ricans fleeing the devastation on the island (Healy and Ferré-Sadurní 20176).

This study builds on literature that examines natural disasters from a sociological perspective. Particularly, it focuses on the aspect of resiliency—“the process by which communities confront and try to resolve different social, political, and economic forces impacting the way they…mitigate, respon[d] [to], and recover from a disaster” (Rivera and Kapucu 20157, 2). This literature has also drawn attention to the significance of community-based disaster resilience (Fischer 19988; Aldrich and Meyer 20159). For example, formal and informal social ties are critical resources drawn upon during and following disasters (Aldrich and Meyer 2015). Community members engage in search and rescue operations, provide immediate assistance and access to resources and information, and they are also a source of important emotional and psychological support (Hurlbert, Haines, and Beggs 200010; Aldrich 201111). Another line of scholarship examines the relationship between climate change, natural hazards, and migratory movements. This work has found that migration in response to natural disasters is informed by various factors, including financial resources, social networks, and access to and historical ties with destinations. It also finds that temporary rather than permanent migration is the most prevalent pattern (Newland 201112). This study engages with the above literature by centering the narratives of Puerto Ricans who experienced Hurricane Maria and were displaced to Florida. This investigation is guided by the following interrelated research questions:

How did Puerto Rican evacuees in Florida experience Hurricane Maria and relief efforts? How did evacuees respond in the storm’s aftermath?

What factors influenced Puerto Rican evacuees’ migration decision-making, and why did they choose Florida as their destination? What type of material and social resources did Puerto Ricans draw on to migrate?

What are evacuees’ settlement plans in Florida? What type of resources have Hurricane Maria evacuees accessed in Florida (e.g., disaster relief, housing, employment, social services) and what challenges have they encountered?

Methodology

Data for this report come from 17 in-depth interviews conducted in the Orlando metropolitan area (Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford). The Orlando metro area was selected as the research site because it is home to the second largest Puerto Rican community on the mainland (380,000) (ACS 201713). Moreover, Orlando is located in Florida, the state that has consistently ranked as Puerto Ricans’ top mainland destination for over a decade (Velázquez Estrada 201714). Given these settlement patterns, the Orlando metro area was expected to attract a significant proportion of those fleeing the island in the wake of Hurricane Maria.

The interview sample includes 14 families that arrived in Florida from Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. These families originate from various parts of Puerto Rico, including the San Juan metro area (5), and the central (3), eastern (3), northern (2), and northwestern (1) regions of the island. Families arrived in the Orlando metro area from October 7, 2017–December 27, 2017. The interview sample also includes three local government and community leaders who had unique insight into institutional and community-led efforts carried out for Puerto Rican evacuees. Interviews were guided by a semi-structured interview guide, and they lasted 45 to 120 minutes. Interviews were conducted at a location selected by respondents, most often at a relative’s home or at the FEMA hotel where they were temporarily residing. The majority of interviews were conducted in Spanish (14) and a smaller share in English (3). All interviews were digitally recorded. The analysis was conducted in the same language as the interviews to preserve the integrity of the narratives; interview excerpts included in this report were translated by the author. The analysis relied on an inductive/deductive approach that allowed for the capture of themes emergent in narratives, as well as theory-driven themes. Respondents were identified via existing networks in the region that were established during previous research, at community-based organizations serving hurricane evacuees, and through respondent referrals. Interviews were conducted in December 2017 and early January 2018. All respondents have been assigned pseudonyms to protect their anonymity and confidentiality.

Other types of data collected include: socioeconomic and demographic surveys of evacuees, which were conducted at the end of interviews; observations conducted at two community organizations; local emergency operations data that capture the number of Puerto Rican evacuees seeking assistance at the airport Multi-Agency Resource Center (MARC); and air travel data, including the number of flights and passengers that arrived from Puerto Rico from October 2017 through March 2018.

Findings

Experiencing Hurricane Maria and the Aftermath

Descriptions of Hurricane Maria

Respondents’ descriptions of Hurricane Maria capture the magnitude of the storm and the profound impact it had on respondents and their families. Victoria, a 70-year-old respondent from Toa Alta’s countryside, recounted that Hurricane Maria was “like no other storm I have experienced in Puerto Rico.” Kamila, from the metropolitan municipality of Cupey, described Hurricane Maria as a “horrible experience,” the storm was “incessant.” She recalled that at one point “you begin to panic, and you’re just waiting for your house to fall apart.” Nayelis, from the coastal town of Aguadilla, noted “Maria was a monster!” and said the “wind made a dark ominous sound.” The winds were so powerful that at one point, her 7-year-old son, in tears, asked “Mommy what is this? It seems like it’s the end of the world.” She added, “we would ask ourselves when is this going to end?!” In fact, most respondents reported that Hurricane Maria lasted anywhere from 24 to 36 hours, with some unable to leave their home for two full days. Fabiola from Adjuntas, a municipality in the central region of the island, offered a similar description of the storm’s duration, “it was an eternity… it was horrible.” Alondra, who resided in an urban area of Trujillo Alto, described the early morning as “twelve horrific hours. It was never ending, it felt as if [Hurricane Maria] lasted three days… it was truly a difficult experience.”

Surviving the Hurricane

All families described having to enter “crisis-management” in the midst of the Category 4 storm. Homes became inundated with rain that filtered through windows, doorways, and air conditioning units. Many reported having to spend much of the hurricane trying to soak up water with towels and bed linens while also trying to save their furniture and personal belongings. Some men held up doors as the wind threatened to knock them off their frames, while others held wooden panels over shattered windows. Some respondents drew on their ingenuity to deal with emergent issues. For instance, because Victoria did not install protective panels over her windows, her niece used candle wax to seal aluminum window frames while Victoria tied down cranks on her glass windows to keep them shut. And Sarah from Caguas rearranged her bedroom furniture during the storm to bolster a sliding glass door that seemed unlikely to resist powerful winds.

Some families sought shelter in single rooms or confined spaces when the hurricane strengthened. One respondent described spending the duration of the storm in a narrow hallway with her three sons to protect themselves from glass projectiles, as she expected her apartment windows to burst. Others recounted that entire families relocated into single bathrooms to escape flooding in other areas of the home and because they feared debris and zinc roof plates would fly through windows. Kamila and her family retreated to her son’s room because it was the safest room in their house. While in her son’s room, “there were instances in which the wind strengthened and the hallowing was more piecing, this is when we would pull blankets over our heads to protect ourselves… at various points we all got on our knees and prayed, we asked God to protect us, to end the storm, we begged him to end the noise because it was making us anxious.” While all participants described Maria as unrelenting, they did emphasize that the early morning hours (1 a.m.–8 a.m.) of September 20 were the most difficult. Sofia, from Rio Piedras, recalled that nobody slept that night because “you could feel and hear a buzzing coming through the windows. I would plead, ‘Lord Father, when will it dawn?’”

The Aftermath

Respondents described that the devastation caused by Hurricane Maria was immediately visible the moment they stepped outside of their homes. All respondents described broken and uprooted trees, as well as downed electricity poles and power lines, all of which blocked roads in their communities. Local streets were also covered in debris, including metal roof panels and loose hardware, as well as carcasses of animals that did not survive the storm. The deforestation caused by the storm impacted many; emotionally, respondents described that all leaves and vegetation had been blown away. Fabiola recounted what her family observed in Adjuntas once Maria had passed:

“As you walk out you see the destruction… [We saw] a lot of pain, a lot of pain and suffering… We cried with my children, everyone in my house from men to children cried. It was very impactful to see trees grounded, the landscape looked burned, it was just brown, everything was brown… to see the neighbor’s house without a roof… downhill the river had overflown into homes. Thursday morning, we had to begin removing debris from roads [because] we were uncommunicated, we couldn’t leave and nobody could come in, we were isolated.”

Survival and Strategies Deployed Post-Maria

Challenges: Access to Daily Essentials

Conditions worsened in the days and weeks following the storm. Respondents did not expect the level of destruction caused by the hurricane or the amount of time they would spend without access to vital necessities and public services. They described “chaotic conditions” and “a sense of desperation” that came over residents as they sought food, water, and fuel.

-

Food: The majority of families prepared for the storm by purchasing canned food and water. Participants purchased varying amounts of food supplies. The most prepared thought they had purchased enough food and bottled water for about one month. These respondents seemed to be those with greater financial resources, as well as those who had previously prepared for Hurricane Irma and restocked their supplies. Those who purchased fewer items noted that they did so because they did not anticipate the impact Hurricane Maria would have on access to groceries; for others, their vulnerable financial position limited how much, or whether, they could purchase additional food in advance of the storm.

Most families ran out of food within one to two weeks. They described going to the grocery store as a “horrible” experience; lines were “miles-long,” in some instances containing hundreds of people, and the wait was endless. Entrance to grocery stores was limited to 10 people at a time, and purchases were rationed—each customer was only allowed a few canned goods and beverages. Availability of food items was limited, especially fresh foods, and entire grocery departments were empty. A major issue was also the rise in prices that occurred in the weeks after the storm; some respondents reported being unable to afford the higher priced canned goods and drinking water. Overall, families relied on crackers, dry cereal, canned meats, and canned pastas as their major sources of nourishment in Maria’s aftermath. This diet took a toll, particularly on children who asked for home cooked meals, and on individuals with health conditions that require a low-sodium diet.

- Water: Access to potable water emerged as another critical issue. Respondents lacked access to running water for months. Although some families had filled their external water tanks prior to the storm, Hurricane Maria often destroyed these tanks, or the water became contaminated with debris and dirt. Several families had to seek out natural sources of water, collect water in plastic containers, and carry water back to their homes to be used for personal hygiene and for cleaning. While there was a concern about potential contamination and waterborne illnesses, respondents expressed not having another option. Respondents waited in line for 2–3 hours to collect water at springs, creeks, and wells. For some who lived in the metro area, running water was reinstated within 1–2 months; however, this water was not drinkable because at times it was dirty, and at others it was heavily treated with chemicals. Respondents had to purchase drinking water at local stores once their supplies diminished. Purchases of filtered water were limited to one case per customer, and when water became scarce, purchases were further limited to two bottles per person. Bottled water prices increased significantly in the wake of the hurricane—a 24-pack that typically cost $3 tripled to $10. Increased prices also impacted the amount of drinking water that families could buy.

- Electricity: All families lost access to power on the eve of Hurricane Maria regardless of whether they lived in urban or rural areas. One family had not had power since Hurricane Irma. Most study participants reported that they lacked access to electricity anywhere from 30 to 98 days. While a small share of respondents had access to electrical generators, they noted that they did not use these regularly because they were costly to operate. One family had power restored 60 days after Hurricane Maria; the rest of respondents’ homes in Puerto Rico continued to lack electricity at the time of the interviews. The majority of families did not regain full and regular access to electricity until they set foot in Florida.

- Fuel: Fuel was an important commodity in the wake of the hurricane, as it was necessary for gas stoves, transportation, and to operate electrical generators. All families were affected by fuel shortages that followed the hurricane; fuel purchases were limited to $10 worth per customer. All respondents described hours long waits at gas stations and instances in which fuel supplies had been depleted by the time they made it to the front of the line. One respondent recounted that her granddaughter fainted while waiting in line under the hot sun for hours. Respondents developed fuel strategies after realizing the difficulties of purchasing gas. For instance, some noted their spouses stayed at gas stations overnight in order to be among the first customers in line in the morning; others were up by 2 a.m. in order to arrive early at gas stations and limit their wait in line to a few hours; and others took their entire family to gas stations and had each individual purchase a share of fuel to maximize the trip.

-

Cash: Limited access to food and fuel was compounded by the inability to withdraw cash. Banking centers were closed and automated teller machines (ATMs) were nonoperational given the lack of power. Because power and telecommunications collapsed, electronic payment systems were also down, and as such, all purchases were made in cash. Many respondents recounted that their bank account balances were irrelevant, as their financial position after the hurricane was defined by the amount of cash they had on hand. They recalled spending frugally, as it was unknown how long it would be before they could access their accounts. Once systems were restored, respondents reported that cash withdrawals were initially limited to $100 and eventually to $50. One respondent recounted waiting in line at an ATM for twelve hours to withdraw cash.

Survival Strategies

-

Redefining “normal” and developing a new daily routine: Given post-Maria conditions, all respondents’ way of life drastically changed in the wake of the hurricane. All families described developing a new daily routine that was necessary for their survival amidst new living conditions. The new routine required rising before dawn to minimize waits at water wells, creeks, gas stations, and grocery stores. For many families, a typical day began at 5 a.m., and they returned home just before the evening curfew after being in miles-long lines much of the day. Only enough supplies for one or two days could be purchased at a time because purchases were rationed, and as such, the routine was repeated in the following days. The narratives below capture a typical day and survival strategies in post-Maria Puerto Rico:

“We would make a list, a map, [and] we religiously left every day at 6 a.m. to look for water. Every day. We used the water we collected to bathe, clean, and flush the toilet for that day… Once gas arrived, we had to make a new schedule because we needed to be on the road by 4 a.m. to get in line to buy gas, to have gas by 6 or 7 a.m., and then we would look for water, followed by whatever other tasks of the day… It was terrible.” Kamila, Cupey, Puerto Rico

“[Every day] I had to go out and look for food, look for gas, we waited [in line] 8 hours at gas stations... There was a curfew, which was a problem because you had been waiting in line all day and then the police would tell you to leave. I had my children with me and at times… one child fell asleep and the other complained about being tired, but we had to get gas. Entrance to grocery stores was controlled, lines [to get in] were extremely long, stores were empty [and] at times food was spoiled, it was all very hard. Finding water was also very difficult, there was no water [to buy], there was no running water.” Alondra, Trujillo Alto, Puerto Rico

Some respondents received Meal-Ready-to-Eat (MRE) packages from federal and/or relief agencies during Hurricane Maria's aftermath. These MREs were often the primary source of nourishment for several weeks because grocery stores were closed or had limited supplies, and roads were impassable.

Some respondents received Meal-Ready-to-Eat (MRE) packages from federal and/or relief agencies during Hurricane Maria's aftermath. These MREs were often the primary source of nourishment for several weeks because grocery stores were closed or had limited supplies, and roads were impassable.

-

Lacking aid and relief in Puerto Rico: Most families reported receiving little to no aid from local and state governments or federal agencies while in Puerto Rico. Some received aid once, often in the form of “military food” (Meal Ready-to-Eat (MRE)) that was delivered by local government officials or members of the military. Of those who received military food, most received enough meals for one day (2–4 meals). However, families from the central and southeastern regions of the island received more food aid relative to other participants. For example, Mikaela from Cidra received ten meals. Fabiola from Adjuntas was coincidentally in town when the U.S. Marine Corps helicopter arrived three weeks after Hurricane Maria; she recalled taking several boxes of food and distributing them among twelve community members. Melanie and her children, who resided in Las Piedras, survived an entire month on MREs; in fact, while at first these meals were not appetizing, her son reported “meal [labeled] #31 eventually became my favorite,” which suggests that a degree of normalization occurred.

Some families received bottled water from municipal mayors; however, this typically occurred once or twice and came weeks after the hurricane. Two respondents noted that their mayors supplied their countryside communities with portable water tanks; however, these were only available for limited hours. A respondent who resided in public housing in the metro area recounted that her mayor eventually sent a food truck, which distributed one meal per registered resident on a biweekly basis. Others reported that sources of food and water aid included the Red Cross and the Ricky Martin Foundation.

- FEMA absent: Several respondents reported an unsatisfactory experience with FEMA. Those who lived in mountainous regions noted that FEMA arrived with tarps six weeks after Hurricane Maria; moreover, FEMA had stationed in the municipality’s town, which made it difficult for residents who lived in the highlands to access FEMA supplies. In the weeks that residents awaited tarps, they searched for whatever debris or plastic coverings they could find to use as improvised roofs. In some cases, FEMA did not arrive in communities for weeks (21–70 days) after Hurricane Maria. In fact, some respondents had relocated to Florida by the time FEMA representatives arrived at their Puerto Rico homes to assess damages. Their move to Florida further complicated and delayed FEMA aid applications because they were not present when inspectors arrived. Another issue that emerged with requests for FEMA assistance was the method of application: on the web, over the phone, or at municipal emergency management centers. Because telecommunications had collapsed, the first two options were not available to many, while those who were isolated due to road blocks, or who did not have a means of transportation, were unable to get to local/regional application centers. Overall, respondents were disappointed and frustrated with what they described as insufficient aid received, especially once they learned about the amount of aid that had arrived in Puerto Rico and was held at the port. They largely attributed their survival to their individual and community-wide efforts.

-

Community support and resilience in the wake of Hurricane Maria: All respondents recounted that Hurricane Maria fostered unity between neighbors and relatives. A consistent theme that emerged was resident-led community clean-up efforts. Upon realizing the extent of the devastation, respondents understood that they could not rely on the arrival of government agencies to remove broken trees and clear roads of debris and mud. For example, neighborhood residents used machetes, axes, and saws to break down trees that had collapsed. Others recalled that men in their communities organized a meeting to conduct an inventory of their tools and to create a debris removal plan. These efforts were necessary as communities were trapped by uprooted trees, broken branches, and downed electricity posts and cables. In the most extreme case, a respondent revealed a neighbor died on the eve of Hurricane Maria. The neighbor’s family endured the storm with the deceased in their home, and once the hurricane passed, local officials refused to remove the body because FEMA had to document the level of destruction in the community prior to any clean-up. Community members responded by removing debris themselves and creating a narrow passageway that allowed funeral transportation to reach the home.

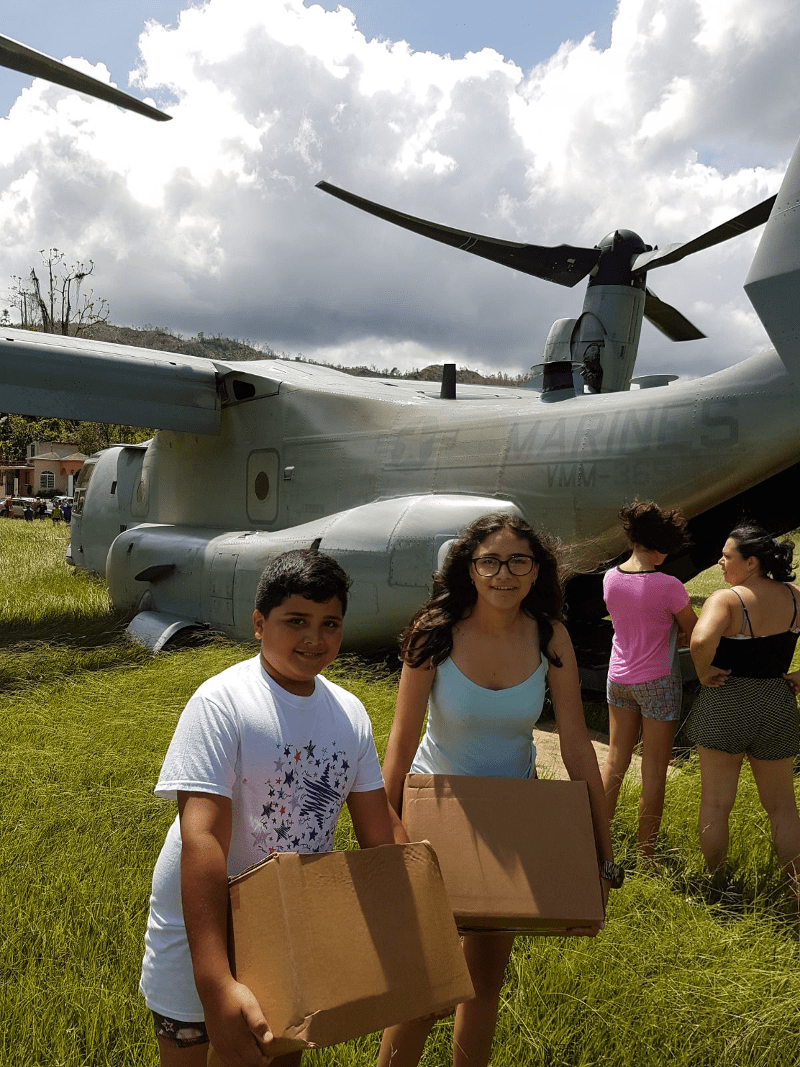

One respondent's children carry boxes of food and snacks distributed by the U.S. Marine Corps in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico. The respondent expressed feeling a sense of relief when the Marine Corps arrived in her town with aid and supplies. She and her husband organized a system of food distribution in which they would pick up supplies in town and drive them to their mountainous neighborhood to be distributed among residents who were unable to leave their homes or neighborhood. The respondent noted that she was able to transport supplies because she had a sport-utility vehicle, which allowed her to drive on rough terrain and roads. The respondent consented to the use of this photo for this report.Another important form of community support that emerged was the sharing of supplies and resources. Neighbors shared: energy produced by electrical generators by adding extensions and running these across properties; gas stoves so that families could prepare warm meals; and water previously collected in external water tanks. Community members also provided food to respondents who had run out, and in other instances, community-wide meals were prepared. One respondent’s family led and organized food distribution efforts. The respondent and her spouse picked up food and supplies when these arrived in town, and her mother and sister maintained a log of community members who were given supplies to ensure equitable distribution. Another respondent led a youth group in his working-class community. The group sought and distributed food aid and planned activities to entertain community members. They also collected funds to photocopy FEMA aid applications, which they delivered to community residents whom they assisted with completing the applications. He noted that through this type of collective work “is how we slowly got up again.”

Social and Material Migration Resources

Social Ties

Social ties, as previously documented by migration scholars, were critical sources of support, as well as resources that facilitated migration and settlement. Relatives and neighbors in Puerto Rico provided financial support to those who wanted to migrate but could not afford airfare costs. Relatives and friends in Florida provided respondents with emotional support and often encouraged respondents’ migration to the state. Because telecommunications were largely unreliable in Puerto Rico, relatives in Florida searched for flights and made travel arrangements for respondents. Some participants noted that while they were still in Puerto Rico, their siblings in Florida researched the types of assistance available to Hurricane Maria evacuees in Florida so that such assistance could be sought as soon as families arrived. Florida relatives and friends also provided guidance and helped respondents identify and navigate local institutions, such as schools, healthcare facilities, and government agencies. Housing was another important form of support that families arriving from Puerto Rico received from Florida relatives. And, for those temporarily living in FEMA approved hotels, relatives in Florida provided groceries, meals, and transportation.

FEMA TSA Program

Seven (of fourteen) families were temporarily residing in local hotels as part of the FEMA Transitional Shelter Assistance (TSA) program. This program provided short-term housing for individuals displaced as a result of Hurricanes Irma and Maria. FEMA covers lodging costs for eligible applicants at an approved hotel or motel in the United States or Puerto Rico. Some families noted that their migration to Florida was only possible because they were able to secure shelter through the FEMA TSA program. Although they had relatives and friends in the Orlando metro area, they did not want to “burden” them with the arrival of an entire family from Puerto Rico. Others reported learning about the program and their eligibility once in Florida. They initially migrated to a relative’s home but noted that it was difficult to have numerous people (in some cases up to nine) living in one house. For another respondent, her Florida relatives were also recent arrivals who did not have secure housing arrangements. At the time of the interviews, the FEMA TSA program was set to expire on January 13, 2018. All respondents who were participating in the program expressed anxiety about the impending deadline. They hoped for an extension because they needed more time to find jobs, to generate the financial resources necessary to secure permanent housing arrangements, and to become familiar with the Orlando housing market. Several respondents noted that if the program was not extended, they would likely become homeless or have to move into a shelter in the area given that returning to Puerto Rico was not an option for them.

Settlement Plans and Community Support in Florida

Preliminary Settlement Patterns

Settlement plans varied across respondents. One respondent on a fixed income indicated that she planned to engage in circular migration mainly because she could not afford to settle in Florida given the higher cost of living. Two families reported uncertain settlement plans, largely due to the highly fluid nature of their circumstances in Puerto Rico and Florida. Four families/individuals reported potential permanent settlement in Florida; this was often contingent on employment prospects in the region, as well as children’s adjustment to local schools and the level of progress made in Puerto Rico. The majority of families planned on permanently settling in Florida (7). This pattern emerged among respondents who had lost a home or experienced significant damage to their home, those who had lost their job, those who had previously considered migrating to Florida, and parents who were focused on their children’s overall well-being. One respondent explained, “We [plan to] move forward. I want to get a job, I want to have a house. I wasn’t able to have my own house in Puerto Rico because salaries are too low. I want to go to school here [in Florida]… There is no turning back.”

Institutional and Community Support in Florida

Multi-Agency Resource Center

Several families visited the MARC at the Orlando International Airport. According to the MARC director, the center was a joint effort between the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority, the City of Orlando, and the State of Florida with the purpose of serving evacuees from Puerto Rico. This effort was led by Governor Rick Scott; upon visiting Puerto Rico days after Hurricane Maria, Scott understood that Florida would become an important destination for island evacuees. While comparable disaster relief centers were also established at the Miami International Airport and Seaport, the director noted that the Orlando MARC received the highest volume of evacuees. Agency records show that the MARC served approximately 30,000 evacuees from October–December 2017, with the majority seeking services in the month of October; in fact, the center served nearly 1,000 evacuees from Puerto Rico on a single day in October. Overall, the center’s director observed that younger arrivals were seeking work opportunities, permanent housing, and schooling for their children; he believes they are likely to stay in Florida if they find these three things. However, he noted that retirement-aged arrivals expressed temporary settlement plans in Florida to await the restoration of public services in Puerto Rico.

A sign in the Orlando International Airport directs those arriving from Puerto Rico to the Airport Disaster Welcome Center (also known as MARC) that provided Hurricane Maria evacuees with information about resources and agencies in Central Florida. Non-profit organizations and local community groups were present to provide information about their services. The center opened in October 2017 and closed on March 30, 2018.

A sign in the Orlando International Airport directs those arriving from Puerto Rico to the Airport Disaster Welcome Center (also known as MARC) that provided Hurricane Maria evacuees with information about resources and agencies in Central Florida. Non-profit organizations and local community groups were present to provide information about their services. The center opened in October 2017 and closed on March 30, 2018.

MARC provided information, assistance, and referrals to those arriving from Puerto Rico. Respondents reported that the services and information they received at the MARC were helpful as they transitioned into Florida. For example, they initiated applications for a Florida driver’s license or identification card. They obtained various types of information, including on local schools and enrollment procedures, distinct state and federal social programs and applications processes, and services provided by community-based and non-profit organizations in the region. They also had access to FEMA representatives on site, which provided information about available aid and assisted with applications.

Community-Based Organizations

Some respondents received assistance from community-based organizations in Orlando, among these, CASA (Coordinadora de Apoyo, Solidaridad, y Ayuda) and Latino Leadership. These organizations provided respondents with non-perishable food, baby food and supplies, toiletries, and clothing and shoes. They also gave respondents information about various services in the region. For some, their visit to these organizations resulted in the establishment of connections that facilitated job opportunities; others met local government representatives who referred them to additional services and programs in their districts. CASA—a group created and led by Puerto Rican community members that was initially established to provide support for Puerto Rico in response to Hurricane Irma—also planned holiday activities for Hurricane Maria evacuees in Orlando. Additionally, CASA was involved in relief efforts for the island, literally collecting tons of supplies that were shipped to Puerto Rico. Other local leaders initiated their own efforts through which they collected donations to purchase tarps, solar-powered lamps, first-aid kits, and other essentials that they personally delivered in Puerto Rico; they also created initiatives such as, Adopta Un Pueblo (Adopt a Town), with the goal of providing consistent aid to Puerto Rico communities.

The warehouse for CASA, a local relief project in Orlando created by community members to provide support in Puerto Rico in response to Hurricanes Irma and Maria. CASA collected and distributed donations (food, clothing and shoes, and personal hygiene products) to Hurricane Maria evacuees who arrived in the Orlando metro area. Donations of water, canned goods, and baby supplies were shipped to Puerto Rico and distributed in the island’s communities.

The logo for Latino Leadership, a community organization in Orlando that provided information about services and donations to Hurricane Maria evacuees who arrived in the Orlando metro area, and the food pantry the organization set up for evacuees.

Local Orlando residents collected and distributed donations, including tarps, solar-powered lamps, and food items, for Puerto Ricans affected by the hurricane in response to what they perceived as slow and insufficient government aid. The residents collected donations and held fundraisers to purchase the tarps and other supplies, and personally flew to Puerto Rico to distribute the supplies throughout island communities in November 2017, often facing difficulties—including improvised bridge crossings—to get to isolated neighborhoods.

Local Schools

Parents reported that local schools had also been supportive. School administrators were understanding of the circumstances in Puerto Rico and allowed children to continue their studies in Florida without holding them back, despite the fact that they had missed most of fall semester. Some schools provided children with school supplies, free uniforms, and meal vouchers. Some local schools donated groceries on multiple occasions, as well as clothes and Christmas gifts for the children. Schools also provided career support services for parents by helping them create resumes to facilitate their job searches in Florida. One respondent recounted becoming emotional when she realized the level of support and empathy her family received from her children’s school. Another parent expressed significant gratitude for the support she had received from a Puerto Rican teacher who was not only helping her child adjust to the local high school, but also identifying local sources of aid for the family and helping the respondent research the process for transferring Puerto Rico teaching credentials to Florida. Overall, parents were optimistic about their children’s ability to adjust to Florida’s education system, and they were encouraged by the level of support they had received in local schools and by educators.

Interpretations of Government Response to Hurricane Maria

Distrust in Government and Political Inequality

The majority of respondents were critical of the response by local, Puerto Rico, and federal government officials to Hurricane Maria. Respondents claimed that Puerto Rico party politics, which is divided along ideologies on the island’s political status, interfered with the distribution of aid at the local level by influencing which residents were prioritized by local officials. Others noted that it was necessary for residents to help one another in the aftermath of Maria because they could not count on government entities to provide vital support and services. Similarly, another respondent expressed that “the government responded once all the clean-up work had been done.” Several respondents also felt that the government of Puerto Rico was slow to respond because it was focused on conforming to federal bureaucratic disaster procedures despite the precarious conditions that residents were enduring. These respondents felt that the Puerto Rico government failed to assert its authority, particularly with FEMA, and to work in the interest of island residents. Respondents also mentioned a belief that Puerto Rican government leaders were purposely delaying the distribution of supplies at the ports for their own political interests. A former employee of the Puerto Rico Agency for Emergency and Disaster Management agreed, noting that per his experience in the field, Puerto Rico government officials knowingly lied to island residents, not only about actual death rates, but also about the extent of progress being made in the hurricane’s aftermath and about projections for the reinstatement of utility services.

Respondents were also very critical of the federal government, particularly of Donald Trump’s presidential visit. Respondents rejected and were appalled by the comparisons he made between Hurricane Maria and Hurricane Katrina. They also felt his four-hour visit was dismissive, as it did not allow for him to grasp the extent of the destruction and the severe conditions that people were enduring. He (and Governor Rosselló) were also critiqued for only visiting middle and upper middle class communities in the metro area instead of visiting the regions of the island that were devastated the most. Some respondents were disturbed and felt disrespected by the president’s comments on the negative impact that post-Maria Puerto Rico would have on the federal budget and comments [tweets] in which he blamed Puerto Ricans for their conditions and slow recovery. One respondent, referencing his infamous visit to a local church, said, “I feel like tossing a bunch of Bounty paper towels at him like he did to us.” Some respondents expressed feelings that the federal government’s slow response to Hurricane Maria and the inferior treatment given to Puerto Ricans stemmed from Puerto Rico’s political status. David, a retired member of the U.S. Air Force who served for 25 years, offered the following:

“We are U.S. citizens since 1917, but this is just on paper. Outside of that, the U.S. doesn’t consider us for absolutely anything; they see the island as a territory that they own where they can come and play golf, but that’s it. In moments like these [Hurricane Maria], we see our lacking importance. Not only is the response slow, they control and restrict the aid they provide us. There has been so much corruption, I hate to admit it, in our existing and former governments [in Puerto Rico]. As a result, [the federal government] closely oversees the aid they provide us… they’ve treated all towns, whether severely impacted or not, in the same manner. They just visited to say they did so without moving with the speed and sense of urgency that was necessary. Who can fix this? I don’t know.”

These perceptions are significant because they demonstrate the ways in which individuals that reside in unincorporated territories experience and make sense of their social and political positions in the aftermath of a catastrophic natural disaster. These perceptions also capture an important erosion of trust in government actors and entities at all levels, a distrust that stems from the dynamics and structural conditions created by Puerto Rico’s unequal territorial and political status.

Recommendations and Conclusions

The experiences documented in this research reveal inadequate and insufficient governmental responses to a catastrophic natural disaster. They also highlight the physical, emotional, and psychological impacts that the destruction and subsequent redefined normality had on respondents and their families. The level of devastation caused by Hurricane Maria is not only a product of the storm’s magnitude, it is also a consequence of a political relationship that has deemed Puerto Rico as unequal and inferior. For example, U.S. imposed economic policies have disrupted the Puerto Rican economy, set in motion the decade-long recession, and led to austerity measures that contributed to the substandard development of the island’s infrastructure. Post-Maria living conditions were exacerbated by colonial legal mechanisms and paternalistic bureaucratic procedures that complicated efforts to receive and distribute aid and provide disaster relief. As scholars have argued, the federal government’s response—disaster wise, verbal/written, and behavioral—reflects a neglect of and double standard toward Puerto Ricans (Rivera and Aranda 201715). Indeed, these structural conditions further increased the island’s vulnerability to a natural disaster and shaped how Puerto Ricans on the island experienced relief efforts. The devastation caused by Hurricane Maria has also contributed to the ongoing exodus of Puerto Ricans from the island. Given that migration has emerged as a form of disaster relief for Puerto Ricans, as well as the number of Hurricane Maria evacuees that have arrived in Florida (over 40 percent of total evacuees) (Centro 2018), the areas of focus provided below identify particular challenges caused by displacement that warrant policymakers’ attention.

Limited Housing

The most vulnerable respondents were those participating in the FEMA TSA program. At the time of the interviews, the FEMA TSA program was set to expire on January 13, 2018; however, the program was later extended until May 14, 2018, on a case-by-case basis. Some respondents assumed that they would become homeless in Florida if they did not receive an extension, while others predicated that they would turn to local relatives for shelter; however, the latter was not a guaranteed option, as homeowner’s associations and leases may restrict the accommodation of relatives. Public housing assistance was not an immediate option, as various regional programs had waitlists that extended several years. Respondents who were part of Puerto Rico’s Section 8 housing program could transfer their vouchers to Florida, but they were responsible for finding a rental property that participated in the program in a limited timeframe. Entering the private housing market was not feasible for many, as this required sufficient financial resources needed for a deposit and first and last month’s rent, as well as commitment to a multi-month lease. Certainly, Hurricane Maria evacuees in Florida will need long-term housing assistance as they settle in Florida and are able to generate the resources needed to secure more permanent housing arrangements.

Jobs

The majority of respondents were seeking employment in Florida, and a few respondents had found temporary or part-time jobs. Because migration to Florida was unplanned and unexpected, several families arrived with limited resources and without the opportunity to research the Florida labor market prior to their arrival. Respondents who had professional occupations in Puerto Rico were seeking information about transferring their credentials to Florida—for many this would require developing greater English language fluency, getting Florida certifications, or downward occupational mobility. Working-class respondents were particularly vulnerable and likely to become incorporated in low-paying service sector occupations. Respondents’ willingness to perform any type of work they could find, including minimum-wage jobs, reflects the urgent need for employment; in fact, a couple of them had taken jobs in the region’s agricultural sector to begin generating income. For many, securing employment in Florida would determine whether they would settle or return to the conditions they left behind in Puerto Rico, as well as their incorporation trajectory in Florida. Access to jobs with living wages as well as employment opportunities that allow them to draw upon their skills, knowledge, and work experience is a critical need for evacuees that have arrived from Puerto Rico and are seeking to start a new life in Florida.

Healthcare and Mental Health Services

Some respondents and their families were in need of important healthcare services. Many families were dealing with the trauma of experiencing a Category 4 hurricane, post-Maria living conditions, and uprooting and leaving loved ones and their homes behind. Some, including children, arrived with health conditions that could not be treated in Puerto Rico due to lacking medical services on the island. In one case, a respondent’s brother became very ill in the wake of Maria because he needs a liver transplant; doctors in Puerto Rico urged the family to seek medical care on the mainland, as he would not receive the necessary treatment on the island. After being in Florida for over a month, the respondent was unable to get his brother on an organ transplant waitlist due to issues with insurance coverage in Florida. Whether it be mental health services, treatable conditions or illnesses, or life and death situations, Hurricane Maria evacuees of all ages will need healthcare coverage and access to healthcare services in Florida.

Conceptually, disaster resilience is important, as it allows us to understand how regions, communities, individuals, and government agencies prepare for, navigate, and respond to and recover from disasters (Kapucu et al 201316; NRC 200917). Critical to this process is the capacity for community redevelopment and the ability to progress beyond pre-disaster conditions (Kapucu et al. 2013; Rivera and Settembrino 201318). Literature that focuses on building disaster response capacity emphasizes that increasing resiliency necessitates having an understanding of areas and regions that are susceptible to natural or human-made hazards, as well as the vulnerabilities of those areas. Moreover, examining the distinctive aspects of communities enables the building of more adequate and effective disaster response and recovery capacity (Rivera and Kapucu 2015). Just as important is the role of social infrastructure for disaster survival and recovery; that is, networks of formal and informal ties that provide vital forms of assistance throughout various stages of a disaster (Aldrich and Meyer 2015).

This study contributes to disaster, resilience, and migration literature by centering the experiences of Puerto Rican evacuees. In doing so, this study expands our understanding of how populations with unequal political/territorial status experience natural disasters and relief efforts, engage in recovery behavior, and experience displacement. The study also analyzes the act of migration and settlement in Florida (short- and long-term) as a form of disaster resilience and demonstrates how social capital (e.g., neighbors, relatives, friends, and co-ethnics) located within (i.e., Puerto Rico) and beyond (i.e., stateside) the disaster site promotes community resilience. Additionally, by examining the narratives of Puerto Rican evacuees in Florida, this study captures how Florida state institutions responded to a natural disaster that did not make landfall in the state, but had reverberating impacts within its boundaries. As such, this study contributes to reconceiving resilience and recovery as multi-sited processes. Scholars have established that regional differences (urban versus rural residence), community socioeconomic status, human resources, and social context combine to create unique community vulnerabilities (Henstra 201019; Rivera and Kapucu 2015). Given that Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the United States, the findings from this study can inform disaster response policies and practices that more effectively address the vulnerabilities and needs of millions of U.S. citizens who are subjected to differentiated rights and protections as a result of Puerto Rico’s territorial status. Finally, this research furthers our understanding of social inequalities, and in particular, how these manifest during natural disasters along political, racial, and cultural lines.

References

-

Centro. 2018. “Puerto Rico Post-Maria Report.” New York: The Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College. https://centropr.hunter.cuny.edu/events-news/rebuild-puerto-rico/puerto-rico-post-maria-report ↩

-

National Hurricane Center, National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration. “Hurricane María Tropical Cyclone Update.” Hurricane Maria Advisory Archive, September 20, 2017. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2017/MARIA.shtml? ↩

-

StatusPR. 2017. Government of Puerto Rico. Accessed October 20-31. www.status.pr ↩

-

Sutter, John D. 2017. “Desperate Puerto Ricans are Drinking Water from a Hazardous-Waste Site.” CNN, October 14. http://www.cnn.com/2017/10/13/us/puerto-rico-superfund-water/index.html ↩

-

Friedman, Nicole. 2017. “Hurricane Maria Caused as Much as $85 Billion in Insured Losses, AIR Worldwide Says.” The Wall Street Journal, September 25. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hurricane-maria-caused-as-much-as-85-billion-in-insured-losses-air-worldwide-says-1506371305 ↩

-

Healy, Jack, and Luis Ferré-Sadurní. 2017. “For Many on Puerto Rico, the Most Coveted Item is a Plane Ticket Out.” The New York Times, October 5. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/05/us/puerto-rico-exodus-maria-florida.html ↩

-

Rivera, Fernando I., and Naim Kapucu. 2015. Disaster Vulnerability, Hazards, and Resilience: Perspectives from Florida. New York: Springer Verlag ↩

-

Fischer, Henry W. 1998. Response to Disaster: Fact versus Fiction and its Perpetuation: The Sociology of Disaster. Lanham: University Press of America. ↩

-

Aldrich, Daniel P., and Michelle A. Meyer. 2015. “Social Capital and Community Resilience.” American Behavioral Scientist 59(2): 254-269. ↩

-

Hurlbert, Jeanne S., Valerie A. Haines, and John J. Beggs. 2000. “Core Networks and Tie Activation: What Kinds of Routine Networks Allocate Resources in Nonroutine Situations?.” American Sociological Review 65(4): 598-618. ↩

-

Aldrich, Daniel P. 2011. “The power of people: social capital’s role in recovery from the 1995 Kobe earthquake.” Natural Hazards 56(3): 595-611. ↩

-

Newland, Kathleen. 2011. “Climate Change and Migration Dynamics.” Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. 2017. American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Hispanic or Latino Origin by Specific Origin in Florida. Table B03001. ↩

-

Velázquez Estrada, Alberto, L. 2017. “Perfil del Migrante, 2015.” Instituto de Estadísticas de Puerto Rico. San Juan, Puerto Rico. https://censo.estadistias.pr/ ↩

-

Rivera, Fernando I., and Elizabeth Aranda. 2017. “When the U.S. Sneezes, Puerto Rico already has a Cold.” Contexts, October 5. https://contexts.org/articles/puerto-rico-already-has-a-cold/ ↩

-

Kapucu, Naim, Christopher Hawkins, and Fernando Rivera, eds. 2013. Disaster Resiliency: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. London: Routledge. ↩

-

National Research Council (NRC). 2009. “Applications of Social Network Analysis for Building Community Disaster Resilience”. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. ↩

-

Rivera, Fernando I., and Marc Settembrino. 2013. “Sociological Insights on the Role of Social Capital in Disaster Resilience.” In Disaster Resiliency: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Naim Kapucu, Chistopher Hawkins, and Fernando Rivera, 48-60. New York: Routledge. ↩

-

Henstra, Daniel. 2010. “Evaluating Local Government Emergency Management Programs: What Framework Should Public Managers Adopt?.” Public Administration Review 70(2): 236-246. ↩

Valle, A. (2018). ¡Puerto Rico Se Levanta!: Hurricane Maria and Narratives of Struggle, Resilience, and Migration (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 279). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/puerto-rico-se-levanta-hurricane-maria-and-narratives-of-struggle-resilience-and-migration