The Relationship Between the Community Rating System Program and Business Disaster Recovery

Publication Date: 2018

Abstract

Scholars argue that businesses benefit from community adoption of mitigation measures. However, there is little information on the extent to which community-level mitigation activities impact business disaster recovery efforts. Using data gathered from 25 semi-structured interviews with businesses and local government staff, this study addresses this research gap by examining business disaster recovery efforts for Hurricane Irma in relation to whether the business is located in a county that participates in the Federal Emergency Management Agency Community Rating System (CRS) program. The CRS is a federal, voluntary program created in 1990 to incentivize communities to implement floodplain management activities that exceed National Flood Insurance Program minimum requirements. Preliminary findings suggest that businesses located in communities with higher CRS ratings recovered faster and sustained less impact than businesses located in communities with lower CRS ratings. Findings also indicate that dependence (both on other businesses and customers), stress and emotional reactions, financial considerations, personnel issues, working with contractors and insurance companies, and supply chain issues affected the ability of businesses to recover quickly.

Background

Hurricane Irma made landfall in Florida on September 10, 2017, as a Category 4 storm. Unlike other major hurricanes in recent years, Hurricane Irma lingered in the Atlantic Ocean for several days, allowing individuals and communities additional time to prepare for the strongest storm on record in the Atlantic Ocean (Klotzbach 20171). Hurricane Irma posed a unique challenge to the entire state of Florida, as initial forecasts suggested that the storm would primarily be an East Coast storm. However, as the storm moved closer to Florida, it continued to move westward, with the eye of the hurricane traveling north along Florida’s west coast. Despite its westward trajectory, Hurricane Irma affected nearly every county in Florida. In fact, initial reports suggest that the costs associated with Hurricane Irma amount to approximately $50 billion (NOAA 20182).

Natural disasters like Hurricane Irma can have devastating effects on communities and, especially, on businesses (Tierney 20073). For example, when businesses are affected by natural disasters, they may be unable to continue their operations for long periods of time, or they may close indefinitely. Hence, when disasters strike, the primary goals for businesses are to survive and to quickly recover (Sadiq and Weible 20104). Despite the important role businesses play in society, no study to the author’s knowledge has considered the extent to which community-level mitigation activities influence business disaster recovery. This is surprising given that scholars (e.g., Tierney 2007) argue that businesses benefit from community adoption of mitigation measures, such as the construction of dams and levees and the regulation of land use. The scientific problem is thus a limited understanding of how community-level mitigation activities influence recovery efforts and how businesses recover from natural disasters.

The present study addresses these research gaps by examining business disaster recovery after Hurricane Irma in relation to whether a particular business is located in a county that participates in the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Community Rating System (CRS) program. This study also examines business disaster recovery among communities that participate in the CRS program at varying levels. The CRS is a federal, voluntary program created in 1990 to incentivize communities to implement floodplain management activities that surpass the minimum requirements of the National Flood Insurance Program. Communities that participate in the CRS can accumulate credit points by implementing floodplain management activities, and in return, enjoy flood premium reductions commensurate with their credit points (FEMA 20175). FEMA organizes participating communities into one of 10 classes. Class 1 consists of communities with the highest number of credit points, while Class 10 consists of communities that do not choose to participate or have not met the minimum requirements for participation (FEMA 2017). The CRS class designations serve as good indicators of the degree of hazard adjustments and flood mitigation efforts initiated by local communities (Brody et al. 20176; Posey 20097; Sadiq and Noonan 20158).

Research Objectives

The purpose of this exploratory research is to gain a better understanding of the business disaster recovery process among communities that do and do not participate in the CRS program. More specifically, the study seeks to answer the following research questions in the context of Hurricane Irma and four counties in Florida: (1) What are the differences between communities that participate in CRS and those that do not with regard to business disaster recovery? (2) How and to what extent were businesses in Florida able to continue operations in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma? (3) Why were some businesses able to recover more quickly from Hurricane Irma than other businesses?

Hypotheses

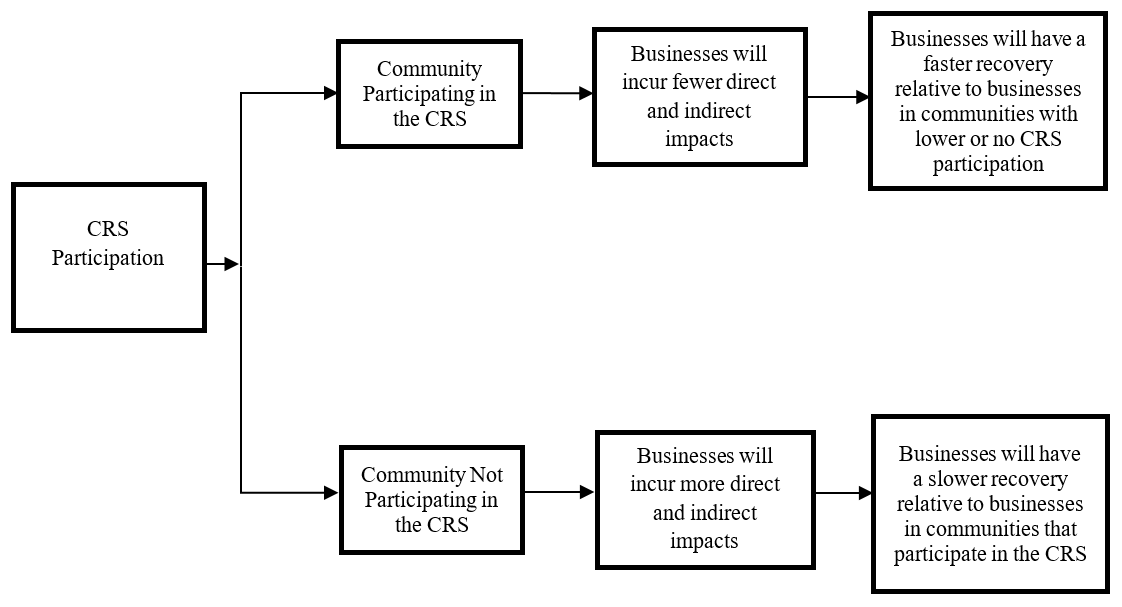

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model underpinning this research. This model suggests that businesses located in communities that participate in the CRS, or that participate in the CRS at higher levels, will incur less direct (e.g., physical damage) and indirect (e.g., supply chain issues and loss of customers) impacts, and as a result, will recover faster than businesses located in communities with little or no CRS participation. The rationale for this argument is that communities that participate in the CRS program experience reduced disaster losses because they engage in more structural (e.g., the construction of levees and floodwalls) and non-structural (e.g., stricter building codes and insurance programs) mitigation activities (Highfield, Brody, and Blessing 20149; Highfield and Brody 201710). Furthermore, studies (e.g., Highfield and Brody 2017) have empirically determined that communities with better CRS ratings experience fewer disaster losses.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of business disaster recovery and the CRS program

Figure 1. Conceptual model of business disaster recovery and the CRS program

Based on this conceptual model, this study tests the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Businesses located in communities with higher CRS ratings will experience approximately the same amount of damage and disruption from Hurricane Irma as businesses located in communities with lower CRS ratings.

Hypothesis 1b: Businesses located in communities with higher CRS ratings will experience less damage and disruption from Hurricane Irma than businesses located in communities with lower CRS ratings.

Hypothesis 2a: Businesses located in communities with higher CRS ratings will recover at approximately the same rate as businesses located in communities with lower CRS ratings.

Hypothesis 2b: Businesses located in communities with higher CRS ratings will recover faster than businesses located in communities with lower CRS ratings.

Data and Methods

Research Design

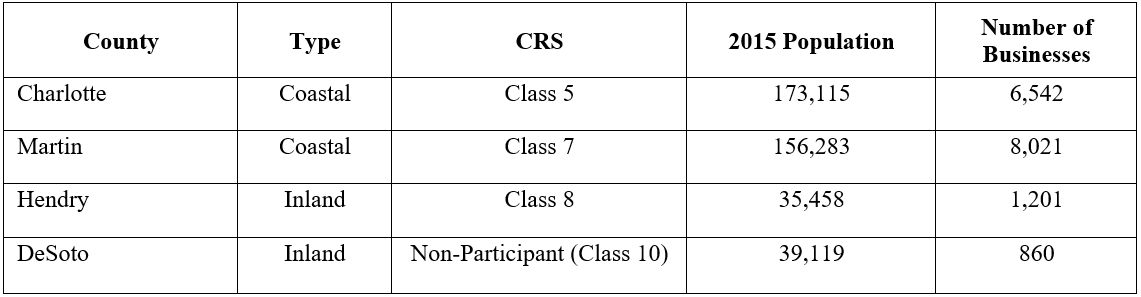

A qualitative research design was employed to examine business disaster recovery from Hurricane Irma in communities that do and do not participate in the FEMA CRS program. Specifically, the author conducted semi-structured interviews with business owners or the individual in the company who was most knowledgeable about the business’ risk management practices (e.g., the risk manager) in two coastal southern Florida counties—Charlotte County and Martin County—and two inland Florida counties—Hendry County and DeSoto County—affected by Hurricane Irma. These counties were purposely selected through a matching procedure based on hurricane impact (measured as whether a county received individual assistance on or prior to September 13, 2017), as well as FEMA CRS program class, population size, and number of businesses in the county as of 2017 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Counties Selected for Sample

Table 1. Counties Selected for Sample

Sampling

To identify businesses to interview, the author established a sampling frame using ReferenceUSA, which provides a comprehensive list of businesses in the United States. Using this database, the author randomly selected 25 businesses from the two inland counties and 50 businesses from the two coastal counties. An additional 25 businesses were randomly selected for the two coastal counties because no interviews had been scheduled after the first 25 businesses were contacted. In total, the author attempted to make contact with 150 businesses (25 in both DeSoto and Hendry counties and 50 in both Charlotte and Martin counties). To ensure the samples were representative of both small and large businesses, proportional stratified random sampling techniques (O’Sullivan et al. 201611) were employed. For example, Charlotte County has 6,542 total businesses, and 5,283 (approximately 81 percent) are considered “small businesses” with fewer than 10 employees (Chang 201012). Thus, the author attempted to contact 20 small businesses and five large businesses in Charlotte County.

Following a modified version of Dillman’s (201113) tailored design method, the author attempted to contact the 150 businesses three times over a four-week period, from October 24 to November 28, 2017. Of the businesses sampled, 19 businesses completed the interview process (10 in person and 9 over the phone), resulting in a response rate of approximately 13 percent. The average length of the interviews was just over 18 minutes, with a maximum time of 28 minutes and a minimum time of 12 minutes. The semi-structured interviews included both open- and closed-ended questions and gathered information on business characteristics (e.g., size, type, and prior disaster experience), how businesses prepared for Hurricane Irma, and the challenges associated with recovering from Hurricane Irma, among other topics. The author recorded and transcribed verbatim 18 of the 19 interviews. One interview was not recorded due to a technical issue.

In addition to interviews with businesses, the author interviewed emergency management directors in the four counties and, when available, the CRS coordinator. There were six interviews in total; four were conducted in-person, and two were conducted over the phone. These interviews were used to gain additional insights into the effects Hurricane Irma had on each county, why each county does or does not participate in the CRS program, and the resources available to businesses as they prepare and recover from natural disasters such as Hurricane Irma, among other topics. The average length of time for these local government staff interviews was approximately 38 minutes, with a maximum time of 53 minutes and a minimum time of 17 minutes. These six interviews were also recorded and transcribed verbatim.

After transcription, the author used the qualitative data management software NVivo 11 to support the examination of data and the organization of themes. To analyze the data, the author first coded the data according to preliminary themes and then went back and searched for additional themes located within the initial codes.

Results

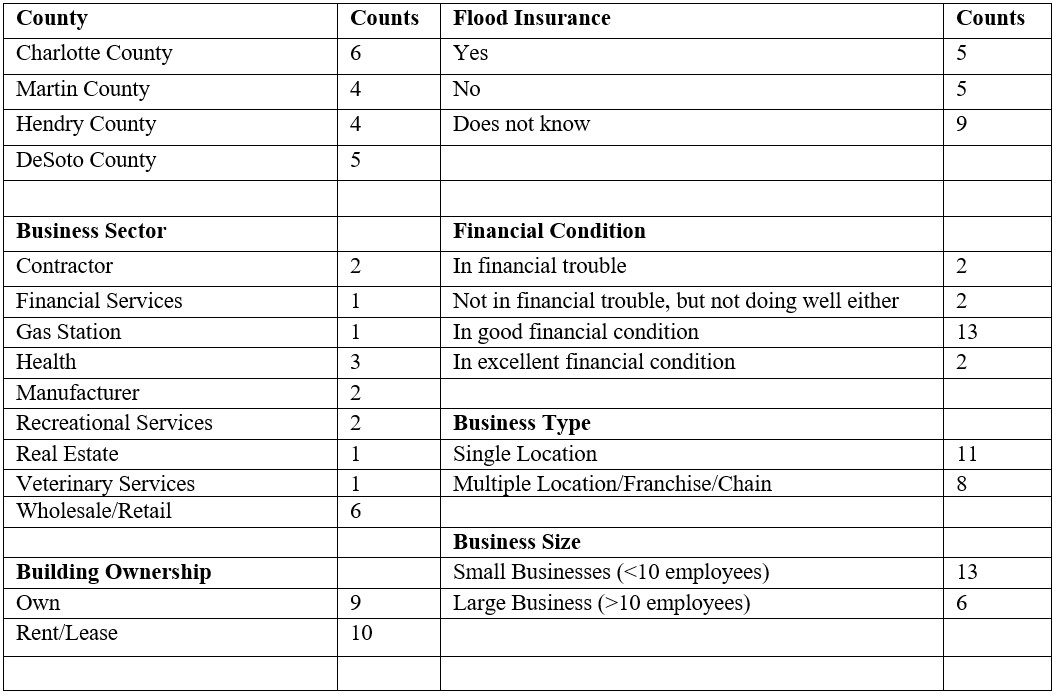

Table 2 shows the demographic and business-related characteristics of the 19 businesses included in this study—six were located in Charlotte County, four each were located in Martin and Hendry Counties, and five were located in DeSoto County, respectively. Six of the businesses were wholesale or retail businesses, and three were health-oriented (for a list of other sector classifications, see Table 2). Eleven businesses operated out of a single-location (versus eight businesses with multiple locations), and nine businesses were operator-owned (versus ten businesses that rented or leased their spaces). Thirteen businesses reported that they were in good financial condition, and the same number were classified as small businesses. Only five businesses reported that they had purchased flood insurance.

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of Businesses

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of Businesses

Tables 3 shows the responses to the following question: “Why was your business unable to continue its operations?” This question was only asked of the 16 business interviewees that responded “yes” to the question, “Was your business closed at any point in time as a result of Hurricane Irma?” Only three businesses reported not closing before, during, or in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma. Businesses that did close remained closed for an average of 5.5 days. Only one business was still closed at the time of the interview. The majority of respondents cited a lack of power and/or internet as the main reason for interrupted operations. However, some businesses discontinued their operations in order to provide employees with additional time to prepare their homes for the hurricane, or as a result of evacuations, physical damage, or limited work available in the immediate aftermath of the storm.

| Theme | Responses to Why Buisnesses were Unable to Continue Operations |

|---|---|

| No Power or Internet |

|

| Employee Preparations |

|

| Limited Business Activities |

|

| Physical Damage |

|

| Evacuation |

|

Table 3. Reasons Why Businesses were Unable to Continue Operations

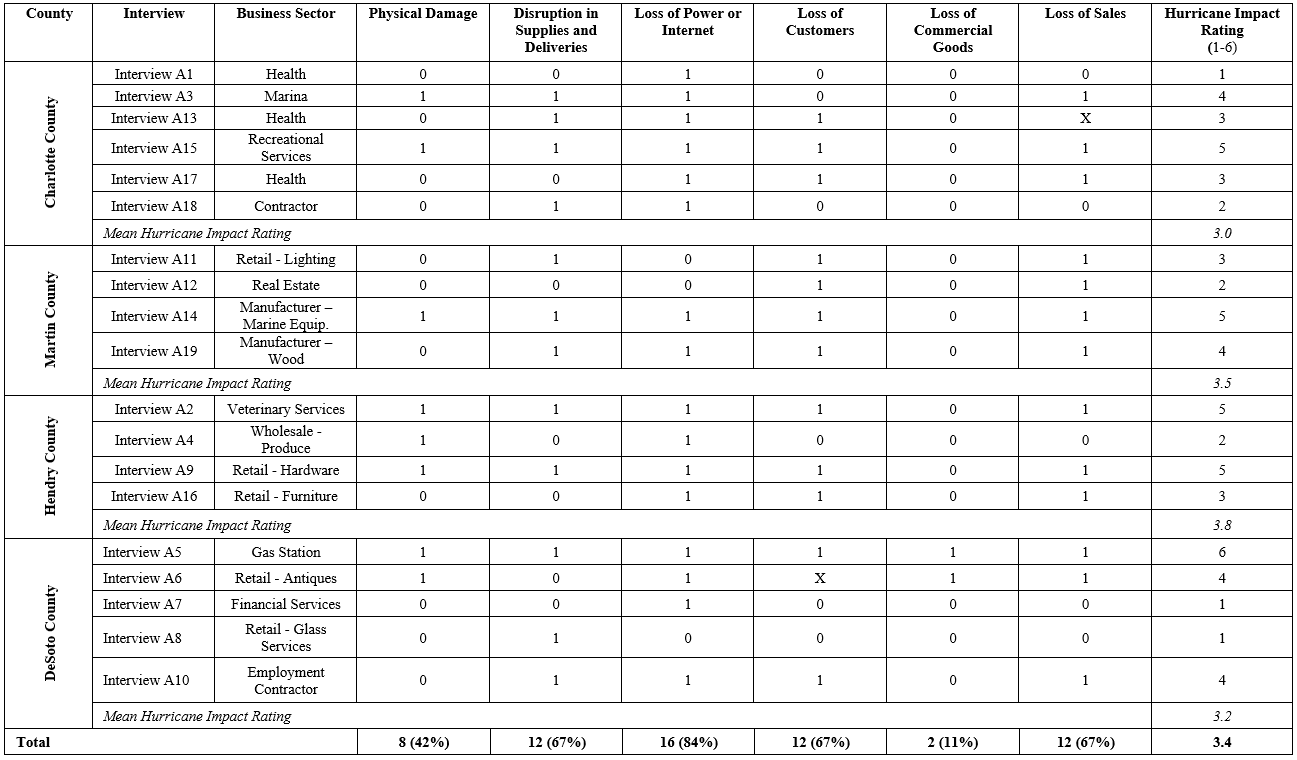

Table 4 presents data on how Hurricane Irma impacted businesses. Specifically, the author read the following statement to respondents: “I am going to read a series of potential impacts businesses in the state of Florida experienced during and after Hurricane Irma. Please indicate whether your business experienced this impact during or after Hurricane Irma. If the item does not apply, simply say ‘does not apply.’” The author then read the following six impacts:

- damage to the business’s physical infrastructure

- disruption in supplies and deliveries

- loss of power or internet

- loss of customers

- loss of commercial goods

- loss of sales

The author added the number of affirmative responses for these six items and then created a hurricane impact rating, ranging from 0 to 6. The results show that, on average, businesses experienced 3.4 of the six hurricane impacts. The most common impacts included loss of power (N=16), loss of customers (N=12), loss of sales (N=12), and disruption in supplies and deliveries (N=12). Charlotte County reported the lowest mean hurricane impact rating (3.0), followed by DeSoto County (3.2), Martin County (3.5), and Hendry County (3.8).

Table 4. Hurricane Impact Ratings Organized by County (N = 19)

Table 4. Hurricane Impact Ratings Organized by County (N = 19)

Table 5 illustrates the number of businesses that have and have not fully recovered in the four selected counties. Business recovery was measured by asking respondents the following two questions:

- To what extent has your business recovered from Hurricane Irma?

On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents “has not recovered at all” and 5 represents “has completely recovered,” to what extent has your business recovered from Hurricane Irma?

These similar versions of the same question allowed the author to capture both contextual and quantifiable data. The data show that businesses located in Charlotte County have the highest mean recovery rating (4.7), followed by businesses located in Martin County (4.3). As mentioned previously, both Charlotte and Martin are coastal counties that participate in the CRS program at Class 5 and Class 7 levels, respectively. The two inland counties reported lower mean recovery ratings. Hendry County, which participates in the CRS program as a Class 8 community, reported a mean recovery rating of 3.3, while DeSoto County, which does not participate in the CRS program reported a slightly higher mean recovery rating of 3.8.

| County | N | Recovered | Not Recovered | Mean Recovery Rate | Relevant Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlotte County | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4.7 |

|

| Martin County | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4.3 |

|

| Hendry County | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3.3 |

|

| DeSoto County | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3.8 |

|

| Total | 19 | 9 | 10 | 4.0 |

Table 5. Number of Businesses Recovered and Not Recovered from Hurricane Irma by County (N=19)

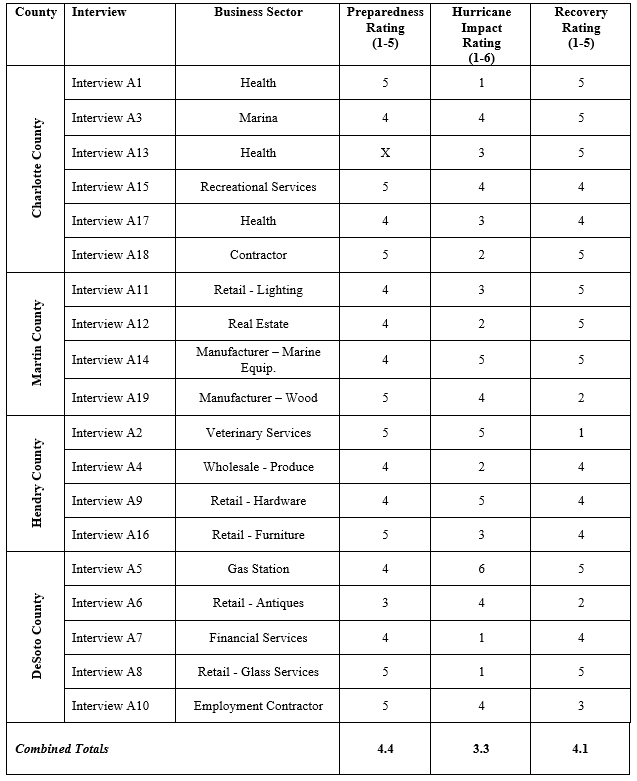

Table 6 compares business hurricane impact ratings, preparedness ratings, and recovery ratings. The preparedness rating was developed by asking respondents the following question: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents ‘has not prepared at all’ and 5 represents ‘very prepared,’ to what extent was your business prepared for Hurricane Irma?” The results from this comparison provide some interesting findings. First, the average preparedness rating, 4.5, was quite high. Second, the data show that businesses with higher preparedness ratings typically had lower hurricane impact ratings. However, these ratings did not always result in higher recovery ratings. For example, despite having experienced similar hurricane impacts, three out of the four businesses that had a recovery rating of 1–3 also rated the business as being very prepared (5). This suggests that additional factors may influence business disaster recovery.

Table 6. Comparison of Hurricane Impact Ratings, Preparedness Ratings, and Recovery Ratings Organized by County (N=19)

To identify additional factors that might influence business disaster recovery efforts, the author reviewed the transcripts a second time. This review revealed six additional influential factors: dependence (both on other businesses and customers), stress and emotional reactions, financial considerations, personnel issues, working with contractors and insurance companies, and supply chain issues. Table 7 shows related quotes from respondents.

Dependence |

|

| Stress and Emotional Reactions |

|

| Financial Considerations |

|

| Personnel Issues |

|

| Contractors and Insurance Companies |

|

| Supply Chain Issues |

|

Table 7. Challenges Business Faced during and in the Aftermath of Hurricane Irma Organized by Theme

It is important to note that while the majority of the business contacts interviewed reported that Hurricane Irma negatively affected their business operations, a few reported that Hurricane Irma was, to some extent, advantageous for their business. For example, some businesses saw a temporary increase in sales or customers both prior to and after the hurricane. These businesses were primarily in industries that sold supplies to help homes and businesses prepare and recover from potential storm damage. Another interviewee reported that the hurricane was advantageous because it helped spread out the business’s workload.

Tables 8 and 9 present responses from the county emergency managers and CRS coordinators about how each county helps businesses prepare and recover from natural disasters like Hurricane Irma. Specifically, Table 8 shows the responses to the following question: “To what extent does your county and/or organization work with businesses to help them prepare for natural disasters?” All of the respondents stated that they help businesses prepare for natural disasters through a variety of community outreach initiatives. For example, respondents for two counties each reported that they attend an annual business expo where they disseminate disaster preparedness information. In addition, the majority of respondents reported that they engage their chamber of commerce to provide talks to local businesses on how to prepare for natural disasters. Charlotte County reported the most direct contact with businesses, noting that the emergency management department meets with individual businesses, such as local supermarkets, annually to discuss the importance of disaster preparedness. Table 9 shows the responses to the following question: “To what extent does your county and/or organization work with businesses to help them recover from natural disasters?” In general, respondents reported that their main function is to ensure that FEMA and Small Business Administration resources are available to businesses. It is important to note that the respondent from Hendry County expressed difficulty in providing resources to businesses due to a lack of staff and funding, as well as the absence of a functional economic development council.

| County | Resources to Help Businesses Prepare for Natural Disasters |

|---|---|

Charlotte County |

|

Martin County |

|

Hendry County |

|

DeSoto County |

|

Table 8. Resources Available to Help Businesses Prepare for Natural Disasters

| County | Resources to Help Businesses Recover from Natural Disasters |

|---|---|

Charlotte County |

|

Martin County |

|

Hendry County |

|

DeSoto County |

|

Table 9. Resources Available to Help Businesses Recover from Natural Disasters

Discussion and Conclusions

This study sought to answer the following three research questions: (1) What are the differences between communities that participate in CRS and those that do not with regard to business disaster recovery? (2) How and to what extent were businesses in Florida able to continue operations in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma? (3) Why were some businesses able to recover more quickly from Hurricane Irma than other businesses? In terms of the first research question, the results from the 19 business interviews provide partial support for Hypothesis 2b, which states that businesses located in communities with higher CRS ratings will recover faster than businesses located in communities with lower CRS ratings. For example, as hypothesized, Charlotte County—the county with the highest CRS rating—had the highest mean recovery rating, followed by Martin County—the county with the second highest CRS rating. However, DeSoto County—the county that does not participate in the CRS program—reported a higher mean recovery rating than Hendry County, despite the fact that Hendry County participates in the CRS program as a Class 8. A possible explanation for why Hendry County reported slower recovery times compared to DeSoto County could be that businesses in Hendry County reported slightly higher hurricane impact ratings and greater struggles in providing resources to help businesses recover. Another explanation could be that communities that participate in the CRS must cross a certain threshold to experience fewer disaster losses (Highfield and Brody 2017). In other words, participation in the CRS program as a Class 8 community may not be sufficiently robust to produce fewer disaster losses for businesses in Hendry County. With regard to hurricane impacts, the results do not fully align with the conceptual model, as they provide support for Hypothesis 1a, which states that businesses located in communities with higher CRS ratings will have experienced approximately the same amount of damage and disruption from Hurricane Irma as business located in communities with lower CRS ratings. For example, there is only a 0.8 difference in impact between the most impacted county—Hendry County—and the least impacted county—Charlotte County. Nonetheless, when observing the three communities that participate in the CRS, results showed that Charlotte County (the Class 5 community) reported the lowest mean hurricane impact rating, followed by Martin County (the Class 7 community) and Hendry County (the Class 8 community).

In terms of the second research question, the results show that the majority (N=16) of respondents did not continue their operations just prior to, during, and in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Irma. Respondents reported that a lack of power and/or internet was the primary reason why their businesses were unable to continue operations. Additional respondents reported that they discontinued their operations in order to provide employees with additional time to prepare their homes for the hurricane, or as a result of evacuations, physical damage, or limited work available in the immediate aftermath of the storm. The businesses that did continue operations during Hurricane Irma did so for the following reasons: inability to physically secure the building, sufficient access to electricity throughout the storm, availability of shelter space for employees, or because the business was housing the pets of individuals who evacuated.

Finally, with regard to the third research question, results indicate that, in addition to hurricane impacts, preparedness levels, and community-level flood mitigation activities, dependence (both on other businesses and customers), stress and emotional reactions, financial considerations, personnel issues, working with contractors and insurance companies, and supply chain issues affect businesses’ abilities to recover quickly.

A number of study limitations are worth mentioning. First, this study relies on a relatively small sample size. As a result, the findings are not generalizable among the four counties selected to participate in this study or to other counties that were impacted by Hurricane Irma. Second, there is potential for response bias (Sadiq and Graham 201614). For example, representatives of businesses that have recovered may have been more likely to volunteer to be interviewed compared to representatives of businesses that have not recovered. On the other hand, businesses that have experienced damage and difficulty in recovering from Hurricane Irma may have been more likely to volunteer to be interviewed because they viewed the author as an individual to whom they could voice their frustrations regarding the recovery process; in fact, two respondents were initially under the impression that the author was conducting this research with FEMA. Third, the interviews were conducted over a four-week period. Therefore, it is possible that recovery ratings are skewed. For example, businesses interviewed in October might have lower recovery ratings compared to businesses interviewed in late November. Fourth, inter-coder reliability was not maintained because the author individually coded all of the interview transcripts. Finally, the proposed study cannot isolate the effects of the CRS program on business disaster recovery, nor can it rule out the possibility of confounding factors. Indeed, it is possible that there are other factors that explain why some businesses fare better than others following natural disasters. Thus, future work on this topic would greatly benefit from a quantitative study with a large sample size that includes a variety of control variables, such as financial wellbeing, business age, and level of disaster preparedness. Despite these limitations, the proposed investigation was an ideal opportunity to collect perishable data on Hurricane Irma and represents a first step to improve our understanding of the disaster recovery process in communities that do and do not participate in FEMA’s CRS program.

Acknowledgements. The author is grateful to Abdul-Akeem Sadiq at the University of Central Florida for his support and assistance throughout this project.

References

-

Klotzbach, Phil. 2017. “Hurricane Irma Meteorological Records/Notable Facts Recap. Accessed August 20, 2018. https://webcms.colostate.edu/tropical/media/sites/111/2017/09/Hurricane-Irma-Records.pdf ↩

-

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2018. “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Events: Table of Events.” Accessed August 20, 2018. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/events/US/1980-2017 ↩

-

Tierney, Kathleen J. 2007. “Businesses and Disasters: Vulnerability, Impacts, and Recovery.” In Handbook of Disaster Research edited by Havidán Rodríguez, Enrico L. Quarantelli, and Russell Dynes, 275-296. New York, NY: Springer. ↩

-

Sadiq, Abdul-Akeem, and Christopher M. Weible. 2010. “Obstacles and Disaster Risk Reduction: Survey of Memphis Organizations.” Natural Hazards Review 11(3):110-117. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2017. “National Flood Insurance Community Rating Systems Coordinators Manual.” Accessed August 20, 2018.

https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/8768 ↩ -

Brody, Samuel D., Wesley E. Highfield, Morgan Wilson, Michael K. Lindell, and Russell Blessing. 2017. "Understanding the Motivations of Coastal Residents to Voluntarily Purchase Federal Flood Insurance." Journal of Risk Research 20(6):760-775. ↩

-

Posey, John. 2009. “The Determinants of Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity at the Municipal Level: Evidence from Floodplain Management Programs in the United States.” Global Environmental Change 19(4):482-493. ↩

-

Sadiq, Abdul-Akeem, and Douglas S. Noonan. 2015. Flood DISASTER MANAGEMENT POLICY: An ANALYSIS of the United States Community Ratings System. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research 7(1):5-22. ↩

-

Highfield, Wesley E., Samuel D. Brody, and Russell Blessing. 2014. “Measuring the Impact of Mitigation Activities on Flood Loss Reduction at the Parcel Level: The Case of the Clear Creek Watershed on the Upper Texas Coast.” Natural Hazards 74(2):687-704. ↩

-

Highfield, Wesley E., and Samuel D. Brody. 2017. “Determining the Effects of the FEMA Community Rating System Program on Flood Losses in the United States.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 21:396-404. ↩

-

O'Sullivan, Elizabethann, Gary R. Rassel, and Jocelyn Devane Taliaferro. 2016. Practical Research Methods for Nonprofit and Public Administrators. New York, NY: Routledge. ↩

-

Chang, Stephanie E. 2010. "Urban Disaster Recovery: A Measurement Framework and its Application to the 1995 Kobe Earthquake." Disasters 34(2):303-327. ↩

-

Dillman, Don A. 2011. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method--2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. ↩

-

Sadiq, Abdul-Akeem, and John D. Graham. 2016. “Exploring the Predictors of Organizational Preparedness for Natural Disasters.” Risk Analysis 36(5):1040-1053. ↩

Tyler, J. (2018). The Relationship Between the Community Rating System Program and Business Disaster Recovery Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 269). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/the-relationship-between-the-community-rating-system-program-and-business-disaster-recovery