Toward Equitable Recovery for Unincorporated Areas

Lessons From California’s 2023 Winter Storms

Publication Date: 2024

Abstract

One-third of U.S. residents live in unincorporated areas, which are defined by their absence of local, municipal government. However, hazard mitigation and disaster recovery strategies are largely predicated on strong municipal planning. This is problematic for rural, low-income communities of color with high flood risks, which face yet more barriers to receiving planning assistance. This report examines contextual policy and programmatic changes needed to mitigate flood risks and enact equitable recovery in unincorporated areas. Here, the case of the Pájaro Valley in California is examined through the 2023 Winter Storms, a series of atmospheric rivers which passed across the state between December 2022 and March 2023. In the Pájaro Valley, these storms caused persistent flooding and three levee failures. This Quick Response report examines the extent of flooding, its severity, and barriers to equitable recovery in unincorporated areas across the region. Through semi-structured interviews with community leaders and public officials in the Pájaro Valley, flood risk mapping, and observations of planning meetings, we sought to achieve three goals: (1) determine the distribution and severity of flooding in the region’s unincorporated areas; (2) identify major barriers to equitable recovery in unincorporated areas; and (3) amplify opportunities and future hopes for the Pájaro Valley. We find several barriers surrounding regional coordination, disaster communication, compensation for community-based organizations, and response limitations stemming from jurisdictional boundaries. Conversely, three strategies emerged for addressing these barriers: supporting regional organizations, supporting local leadership and community cohesion, and maintaining the media’s attention. Finally, we close with three policy recommendations: (1) supporting regional-scale initiatives, (2) building and compensating local organizations, and (3) increasing support for studying mitigation and recovery in unincorporated communities.

Introduction

Flooding is the most common hazard in the United States, yet many communities lack the visibility and resources to mitigate their flood risks and recover from flooding due to their location in an unincorporated area—a public policy and planning term meaning “those communities and areas that are outside the jurisdictional boundaries of incorporated cities” (Los Angeles County, 20241). The 2020 U.S. Census estimates that approximately 30% of the nation lives in unincorporated areas, mainly across the American West and Midwest (Toukabri & Medina, 2020, para. 32). Considering this fact, it is noteworthy that funding for hazard mitigation in unincorporated areas has been declining in recent years despite clear increases in urban areas (Bukvic & Borate, 20213). This has led to a largely unspoken belief that unincorporated areas should instead “rebuild themselves” (Seong et al., 20224).

To examine the impact of limited or absent local governance on flood recovery, we collected perishable data regarding the extent of and damage caused by California’s 2023 Winter Storms, which occurred across the coast from December 2022 through March 2023. California experienced multiple atmospheric rivers in rapid succession, causing widespread flooding in rural areas, such as our study area, the Pájaro Valley. The Pájaro Valley is a central coastal region bisected by the Pájaro River, covering southern Santa Cruz and northern Monterey counties. In March 2023, rising waters caused Pájaro River’s levees to fail, inundating and displacing the unincorporated Town of Pájaro, located in Monterey County. Across the river in Santa Cruz County, the City of Watsonville also experienced flooding and displacement of households along the Corralitos Creek, a Pájaro River tributary. The flooding resulted in damaged housing and infrastructure, flooded agricultural fields, and lost jobs. Flood impacts are compounded by existing poverty rates in the Valley experienced by the majority Latinx and/or Indigenous communities. These events eerily mirrored the 1995 floods and levee failures, marking a repeated failure of flood mitigation efforts in this community.

Our goal for this Quick Response project was not just to identify the flood mitigation and response issues specific to unincorporated areas, but also to begin to identify planning and policy strategies to aid these communities. To identify the barriers facing flood mitigation in the unincorporated Town of Pájaro, we undertook flood risk mapping and conducted semi-structured interviews with community leaders and public officials throughout the Pájaro Valley. Through this research we identified: four barriers to equitable recovery following the floods, three strategies found to be indispensable during recovery, and three shared hopes for the future of the region and its riverways, as expressed by our interviewees. We conclude by advocating for three policy recommendations stemming from these findings: (1) there is a need for strong regional governance to support hazard mitigation in unincorporated communities; (2) local networks are key to recovery, but local leaders need compensation for their recovery efforts; and (3) there is a need to replicate this study in other states with differing state-level governance structures.

Literature Review

There is no right to local government in the United States, yet the majority of hazard planning tools and programs at the state and federal levels are designed with the presence of strong local governments in mind (e.g., large, incorporated cities) (Cross, 20015; Hendricks et al., 20186). This lack of policy and planning tools and resources at these levels restricts unincorporated communities’ access to hazard mitigation, particularly throughout the midwestern and western United States where unincorporated areas occur more frequently (Cross, 2001). Horney et al. (20177) found that hazard mitigation plans in rural communities are often of lower quality when compared to plans from urban areas, particularly because rural areas are trying to adapt plan templates intended for use by incorporated cities. Lapping and Scott (20198) refer to this as a “deficit approach” to rural planning and land management, or the theorization of rural areas as “residual” spaces between incorporated cities which inherently lack resources and capacity. This formulation definitionally centers incorporated areas, leaving unincorporated areas to act “opportunistically rather than strategically” (Frank & Hibbard, 2017, p. 3039).

Instead, rural planning scholars advocate for rural communities to be understood through “context appropriate” approaches that “holistically understand and value specific rural places, empower their residents, and coordinate their constituencies” (Frank & Hibbard, 2017, p. 302). In this approach, we view rural communities as being systematically excluded from hazard mitigation planning due to what we call “Scales of ‘No’,” or layers of government in the United States which all deny responsibility for assisting unincorporated areas in hazard mitigation (Rivera, 202310). In lacking municipal governance, unincorporated areas face limited representation and, therefore, political exclusion and barriers to accessing resources, particularly for low-income communities of color (Gomez-Vidal & Gomez, 202111). New tools and approaches for rural hazard mitigation and disaster recovery are needed, as existing tools are not representative of unincorporated area governance and contexts (Gomez-Vidal & Gomez, 2021). This leaves these areas institutionally vulnerable and reduces the possibilities for inclusive decision-making power (Anderson, 200812).

We view unincorporated areas as an inherently distinguishable policy space due to the critical differences in their local governance structures. From the existing literature, two gaps emerge, which underpin our own research questions presented in the next section. First, there is a need to identify the specific local governance structures positively and negatively affecting hazard mitigation in unincorporated areas. Second, there is also a need to identify how these structures also impact disaster recovery.

Research Design

Research Questions

Given the central role local governance plays in achieving equitable recovery outcomes (Olshansky & Johnson, 201413; Rumbach et al., 201614), we specifically focused on how unincorporated status affects flood mitigation and recovery. From this, we pose three research questions:

- What is the distribution and severity of flood damage from the 2023 Winter Storms in the Pájaro Valley?

- What local governance barriers slowed or prohibited equitable recovery in the Pájaro Valley?

- What are the hopes and desires of impacted communities for their recovery and reconstruction?

Study Context

This project is part of a larger study in California and Texas on rural hazard mitigation planning, but this report specifically engages our work in the Pájaro Valley. Our work in the Pájaro Valley is in its third year, with funding continuing for at least another two years. As such, while the primary data collected and analyzed for this report was geospatial or collected through the seven semi-structured interviews with regional leaders and residents, we also analyzed notes from community and planning meetings between 2021 and 2024.

Study Site and Access

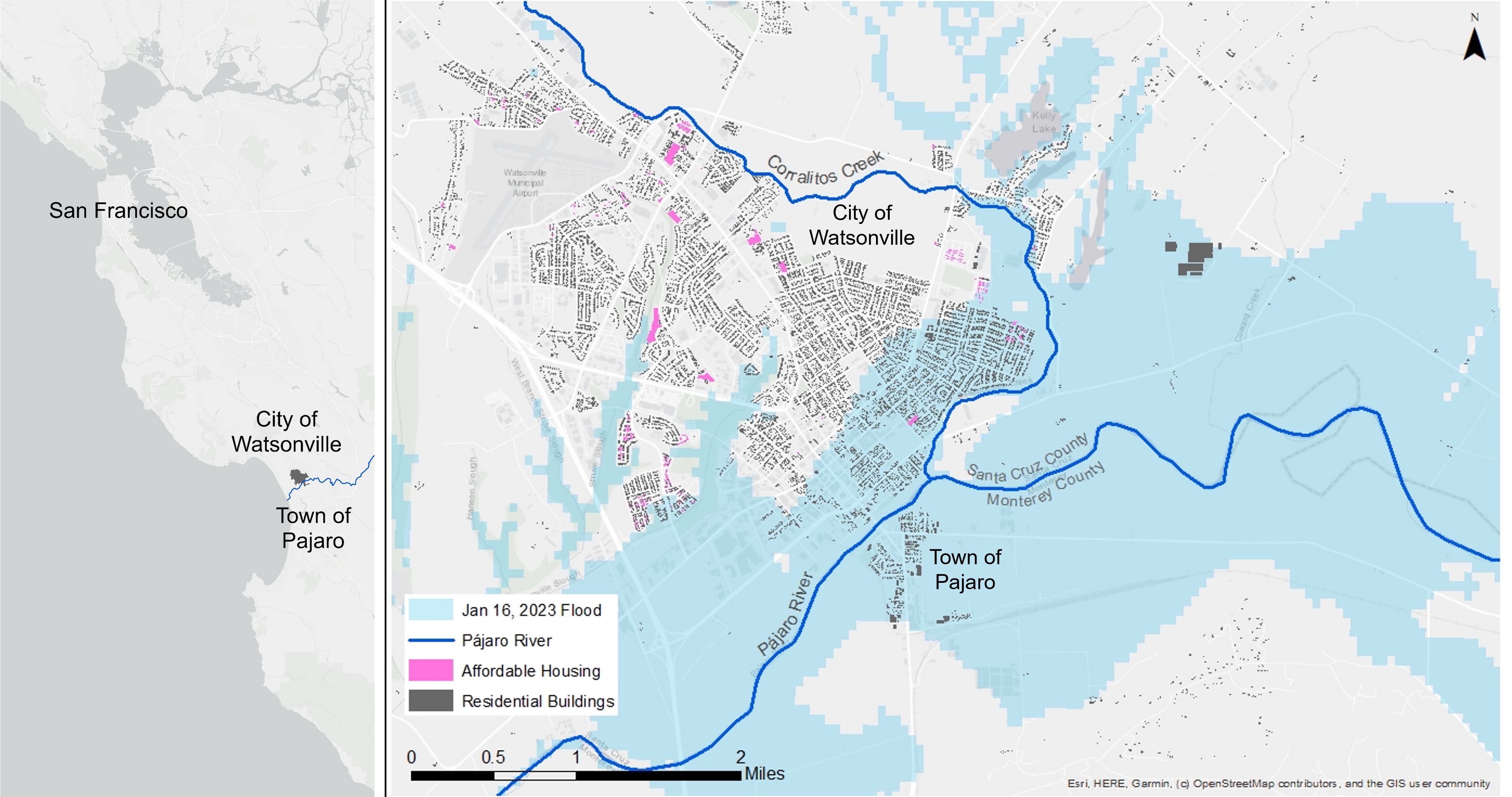

This study focuses on the Pájaro Valley of California, a region situated in the Pájaro River floodplain. Figure 1 shows how the Pájaro River divides the Valley, with Watsonville to the north and Pájaro to the south. Watsonville is located on the northern bank of the Pájaro River in Santa Cruz County and has a population of 53,224, 83.3% of which are Latinx (United States Census Bureau, 202015), while Pájaro is an unincorporated area located across the river from Watsonville in Monterey County and has a population of 3,650, 95.2% of which is Latinx (United States Census Bureau, 2020). This is a primarily agricultural region and, as such, has a large percentage of farmworkers and others working within the agricultural industry. The region has a long history with agriculture due to its highly arable lands and climate, but the unpredictable nature of the Pájaro River has contributed to repeated floods throughout both its developed and agricultural areas.

Figure 1. Location of the Pájaro Valley (Left) and Prediction of Flood Exposure on January 16, 2023 (Right)

Most recently in 2023, a series of atmospheric rivers (or concentrated streams of moisture over the Pacific Ocean) led to multiple months of sustained rainstorms known as the “Winter Storms.” These storms caused widespread flooding throughout California due to the exceedingly dry lands from La Niña years, which caused the ground to behave hydrophobically, or disallowing/slowing the absorption of water into the ground. This increased the velocity of stormwater across the state and caused stormwater management systems to back up due to accumulated debris from drought years. President Biden declared the winter storms a Major Disaster (DR-4683-CA) on January 14, 2023 (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2023a16). A second Major Disaster declaration (DR-4699-CA) was made on April 3, 2023, given continued rains and flooding across California and the failure of the Pájaro River levee in three locations in Monterey County (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2023b17).

In researching these storms, our two community partners—Regeneración and Watsonville Wetlands Watch—were essential in gaining local community members’ trust and in identifying relevant local leaders to speak with. Regeneración is a nonprofit organization focusing on climate action throughout the Pájaro Valley. Our second partner, the Watsonville Wetlands Watch, is a nonprofit organization working with local jurisdictions to protect and restore wetland habitats. They also undertake community outreach for ecological literacy. Lastly, the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency is a relatively new joint powers authority tasked with reducing flood risk from the Pájaro River and its tributaries. Since its introduction to the region in 2021, it has quickly become a critically important local actor in flood mitigation and, as such, they figure prominently throughout our findings and discussion.

Methods

Semi-Structured Interviews

Our team conducted seven semi-structured interviews with local leaders and representatives, including:

- Member of Regeneración—Pájaro Valley

- Planner at the City of Watsonville

- Housing Planner at the City of Watsonville

- Member of the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency

- Public Works Official at the City of Watsonville

- Resident in the Town of Pájaro

These semi-structured interviews lasted 60 minutes each and were conducted at the time and location of the interviewee’s choice. As such, most interviewees elected to be interviewed via online video conferencing. The lone exception was the Pájaro resident interview, which occurred in-person in Pájaro and lasted three hours.

Sampling Strategy and Recruitment

We used a combination of purposive and snowball sampling strategies for sampling of government officials and members of non-profit organizations. Purposive sampling identified key interviewees by their position and/or leadership within the valley’s flood recovery processes. This fed into snowball sampling, whereby additional interviewees were identified from our first round of interviews. For resident sampling, we used emails shared through a survey randomly distributed to Pájaro Valley residents living in FEMA’s 100- and 500-year flood zones, contacting only residents who expressed an interest to be interviewed. All potential interviewees were contacted via an email where our research team introduced ourselves, the project, and provided a consent document for their review. If willing to participate, a time and place of the interview was chosen by the interviewees. All interviewees signed the consent form, were informed of their rights, and reminded that the interview was voluntary, and they could skip any questions they wished.

Interview Questions

Interview questions were divided into one of five question types: introductory, extents/impacts of Winter Storms, barriers to recovery/mitigation, positive strategies and future hopes, and concluding. (The interview guide we used for residents can be found in Appendix A whereas Appendix B provides the interview guide for government officials and nonprofit representatives). Given the semi-structured nature of the interviews, interviewees had space and flexibility to speak to what they wanted to share and skip topics that they did not want to discuss. For interviewees who felt comfortable sharing spatial information about where and how flooding occurred, we used participatory mapping techniques whereby interviewees drew the areas that flooded in the Winter Storms on printed or digital maps.

Data Analysis Procedures

We used qualitative coding analysis to assess the interview results and cross-analyze our data sources using Atlas.TI software. The research questions were leveraged as guides for analysis by focusing our quote selection on the (a) extents/impacts of the Winter Storms, (b) stated barriers to mitigation and in the recovery process; and (c) strategies that helped or worked well and hope for the future. These quotes, once categorized as above, were then further classified by the core themes presented in our Findings and Results.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

All the researchers listed on this proposal reside in the Bay Area. Because we live close to the research site, we were able to carefully time our recruitment of research participation so that it took place just after the short-term recovery phase of the Winter Storms, avoiding emergency response and early recovery phases which we view as unethical to interrupt (Oulahen et al., 202018). Additionally, all researchers successfully passed the CONVERGE “Broader Ethical Considerations for Hazards and Disaster Researchers” Training Module before engaging in the research (Adams et al., 202119). Lastly, as the team discussed our final interview guide, we chose to add more questions regarding what went well in the recovery process to avoid a “damage-centered” narrative of the region and to reduce the possibility of re-traumatizing research participants (Tuck, 200920).

Findings and Discussion

In this section, we present our findings and discuss their theoretical and policy-level significance for equitable flood recovery in rural and unincorporated communities. Table 1 summarizes these findings following our three research questions.

Table 1. Overview of Findings

| Research Question | Findings |

| Research Question 1: Distribution and Severity of Flooding | ● Finding 1: Uneven Flooding in Unincorporated Areas ● Finding 2: Widespread Housing Damage and Displacement in Pájaro |

| Research Question 2: Barriers to Equitable Recovery in Unincorporated Areas | ● Barrier 1: Lack of Regional Expertise and Capacity ● Barrier 2: Inconsistent Disaster Communications ● Barrier 3: Lack of Compensation for Community-Based Organizations ● Barrier 4: Responses Fractured on Jurisdictional Lines |

| Research Question 3: Opportunities and Future Hopes for the Pájaro Valley | ● Strategy 1: Cultivating Local Experts and “Diplomacy” ● Strategy 2: Community Cohesion for the Community Itself ● Strategy 3: Keep the Media’s Attention ● Hopes for New Forms of Connection to the Pájaro River and Community |

Distribution and Severity of Flooding

Upon examining our first research question, we discovered that there were few to no resources tracking the extent and severity of flooding across the Pájaro Valley region throughout the Winter Storms. Even the community representatives we interviewed expressed frustrations with their own lack of comprehensive knowledge regarding when and where flooding occurred. Two key findings emerged concerning the spread of flooding in the Pájaro Valley’s unincorporated areas.

Finding 1: Uneven Flooding in Unincorporated Areas

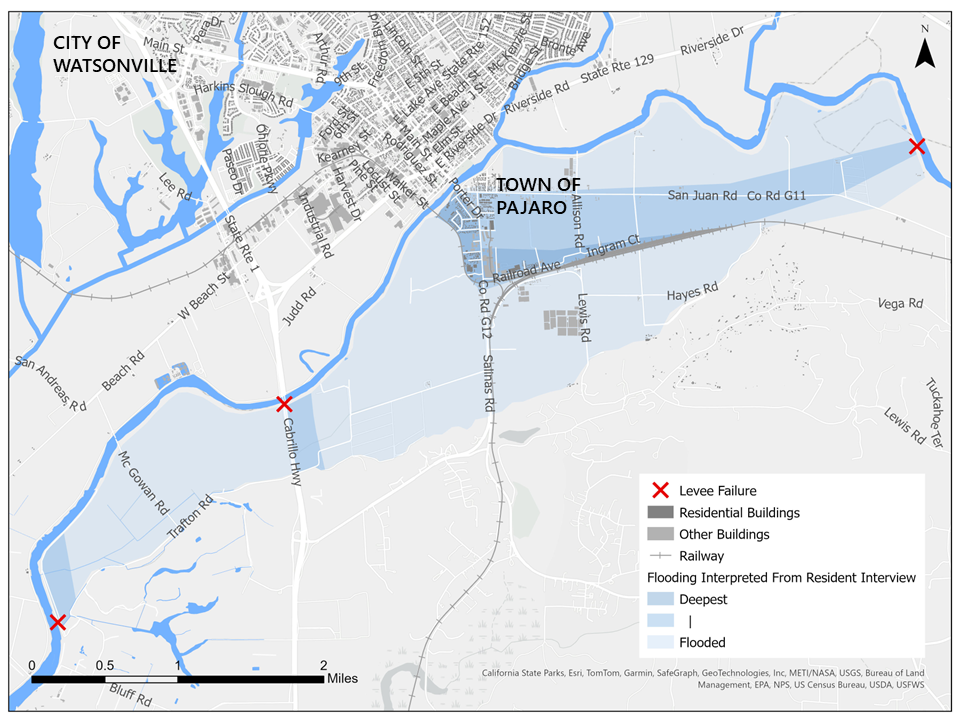

While media outlets focused on the main Pájaro River levee breach, our interviewees—including a Pájaro resident, an official from the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency, and an organizer from Regeneración—described how its flood water flowed across the Monterey County-side of the region, leading to two further levee breaches down-river in Monterey County, as shown in Figure 2. Furthermore, two interviewees—the planner from the City of Watsonville and the official from the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency—explained that flooding occurred at least four times along the breadth of the Pájaro River’s two major tributaries, the Salsipuedes and Corralitos Creeks, which form the jurisdictional boundary between incorporated Watsonville and unincorporated Santa Cruz County and, in some areas, only have levees on the Watsonville side. This flooding occurred unevenly across the creeks.

Figure 2. Extent of Flooding in March 2023

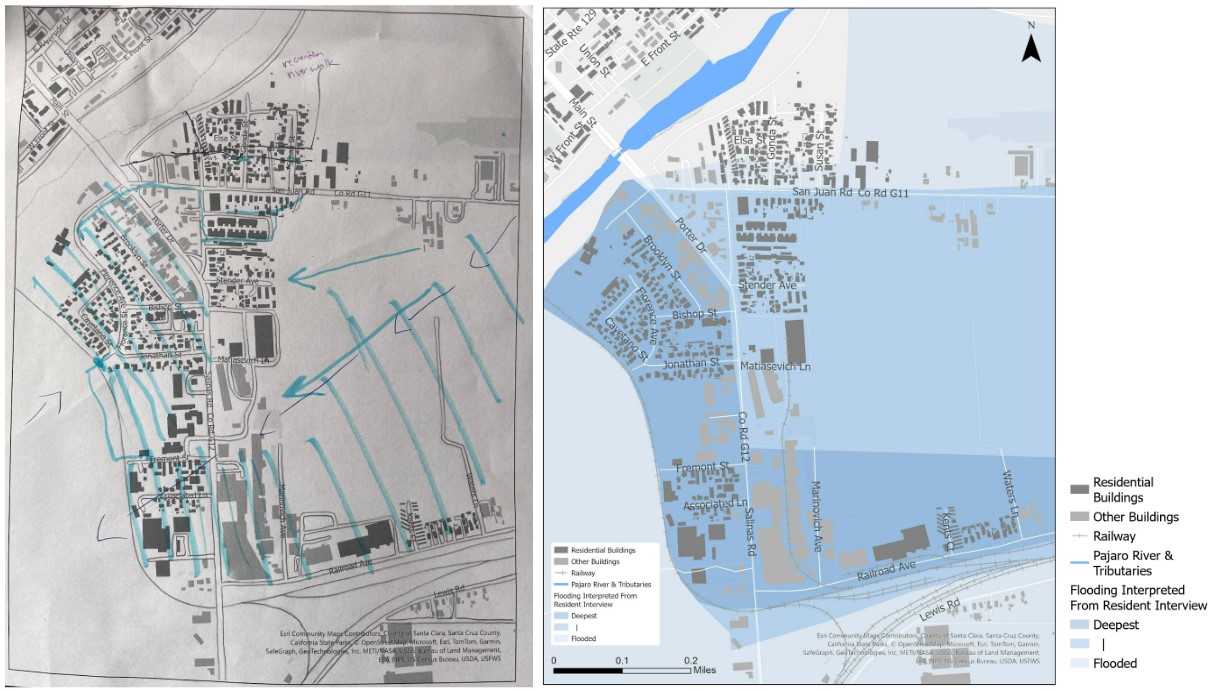

However, even within unincorporated areas like the Town of Pájaro, flood risk was found to be uneven in potentially significant ways for proposed flood mitigation projects. Mr. Hall, a third-generation resident of Pájaro (given a pseudonym to protect his identity), shared his experiences with the 2023 Winter Storms and the 1995 storms and levee failure. As a long-term homeowner, landlord, and volunteer firefighter in the 1995 flood response, Mr. Hall recounted the flood risk in Pájaro:

I mean it would come up in the street [San Juan Road] about 3 feet and if you look at the houses across the street [south side of San Juan Road], they've been there a while and they built them up because they remember where the water goes… you know San Juan Road is pretty deep, but it did not flood these houses.

Mr. Hall walked one of the authors through the Town of Pájaro, providing insights on where flooding was most severe, the flow patterns of the water, blockages he witnessed which exacerbated flooding, and the locations of levee failures. Mr. Hall helped create participatory maps, depicted in Figure 3, to visualize his insights. The key finding in Mr. Hall’s account of the Pájaro River’s levee breach is that part of the unincorporated area of Pájaro rarely (perhaps never, in Mr. Hall’s account) floods. However, in speaking with various state and federal agencies during planning meetings, it appears this is not known beyond this small subsection of the Pájaro community.

Figure 3. Hand-Drawn and Digitized Participatory Maps of March 2023 Flooding in the Town of Pájaro

Finding 2: Widespread Household Damage and Displacement in Pájaro

While we investigate the varying intensity of flooding across the community, it is important to keep in mind a quote from an official from the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency, who noted that “flooding of any magnitude anywhere is catastrophic, it's damaging, it upsets people's livelihoods. Even the smallest amount of water can completely overwhelm a home with mold.” Table 2 shows the results from an assessment of 691 homes in Pájaro after the levee failure. The assessment found that 273 homes were damaged—five homes were destroyed, 37 had major damage, 114 had minor damage, and 117 had “some” damage. Of the damaged homes, the majority were single-story, single-family residences, followed by mobile homes.

Table 2. Housing Damage Assessment Results for Pájaro (Scroll left or right to view full table)

| Mixed Commercial/Residential | 0 | |||||||

| Mobile Homes | ||||||||

| Multi-Family Residence: Multi-Story | ||||||||

| Multi-Family Residence: Single Story | ||||||||

| Single Family Residence: Multi-Story |

||||||||

| Single Family Residence: Single Story | ||||||||

| Total |

Long-term displacement is not assessed or recorded after a disaster event, and individual and household recovery is difficult to track. “People leaving the region” is a tempting metric, but it can be difficult to ascertain whether they were forced into unstable living situations or homelessness, or simply chose to move elsewhere. Changes in school enrollment rates for the Pájaro Valley Unified School District hint at the scale of displacement, however. According to enrollment data, the school district lost 2,043 students between the 2022-23 and 2023-24 school years, lowering total enrollment to 15,920 (California School Dashboard, n.d.21). Additionally, two interviewees—planners in the City of Watsonville—explained that homelessness has been rising in the Pájaro Valley. The population of unhoused individuals living in Watsonville was approximately 175 in 2022 but increased to approximately 322 in 2023 (Guild, 202422). A Watsonville Public Works official interviewed for this study noted that the city had become host to new populations due to post-flood displacement:

The population boom we’ve seen is [from] unsheltered residents, which is unfortunate, but I think a lot of people were potentially displaced from their homes, or they were displaced from the levee system and they’ve moved over to our side [Watsonville].

Barriers to Equitable Recovery in Unincorporated Areas

Our second research question sought to uncover the barriers to equitable flood recovery in unincorporated communities following the Winter Storms. We have identified four for discussion.

Barrier 1: Lack of Regional Expertise and Capacity

“This community here is ignored, Pájaro is totally ignored,” Mr. Hall stated. This sentiment is not uncommon in unincorporated areas and small towns unable to undertake extensive hazard mitigation planning due to lack of city services. There is a sense that no one is tracking major hazards. A Watsonville Public Works official said during their interview that Pajaro’s limited services and planning abilities stemmed from their smaller population and limited tax base, whereas Watsonville residents received more services because have a higher-than-average property tax rate.

While limited capacity to mitigate flood risk is recognized in the broader mitigation literature (Seong et al., 2022), our research uncovered a key mechanism missing from unincorporated and rural areas. As the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency employee stated, interacting with government agencies requires extensive “know-how”. As they further noted:

It takes expertise on the local side to know what to say, when to say it with the Army Corps, and how to push on them to get repairs done and get them to move and step aside of their own internal barriers.

This depth of expertise is rare to find outside of incorporated cities and, even when found, difficult to leverage effectively across unincorporated spaces. This interviewee felt that regional bodies, like the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency, are well-positioned to effectively steward mitigation projects spanning multiple local and county jurisdictions and undertake the difficult task of coordinating between various federal and state agencies, whose funding and rules may conflict with one another. This expertise is further discussed below as a positive strategy.

Barrier 2: Inconsistent Disaster Communications

“Who is the responsible agency?” This reasonable question was posed by a community leader in a February 2023 planning meeting. There was no clear answer for the Pájaro Valley. Our discussions with officials highlighted the real procedural challenges with coordination and communication around flood risk and even active flooding. A Watsonville Public Works official noted the difficulties of keeping up with ever-shifting conditions:

You don't know who's in charge [...] and you're just trying to do the best you can in the moment with the information you have. In strategic planning, they want me to figure out 10 days from now; well, those atmospheric rivers were coming and slamming into the Central Coast. [...] We had never seen anything like that before historically, so communication was a real struggle.

There is still a sense that no one knows who is “responsible” for regional disaster communications, particularly in unincorporated areas not covered by Watsonville. Additionally, the state only seemed prepared to communicate in English and Spanish, not Mixteco Bajo, which is commonly spoken by local farmworkers according to the organizer at the nonprofit, Regeneración, who was interviewed for this study.

Barrier 3: Lack of Compensation for Community-Based Organizations

As a continuation of fractured disaster communications, at several meetings and in our interviews, it was evident many community-based organizations feel “exploited” by government agencies who used them to contact residents in the absence of “formal” communications systems in the unincorporated areas of the Pájaro Valley and across the local farmworker communities. The work community-based organizations did to provide assistance required extensive staff time and including providing translation services (to Spanish and Mixteco Bajo) and two-way data sharing on active flooding. Despite their contributions, we found that much of this work was not compensated, stoking mistrust of the government in the community.

Barrier 4: Responses Fractured on Jurisdictional Lines

In speaking with Watsonville employees, their concerns for Pájaro residents are deeply felt. Yet, the realities of jurisdiction dictate that they cannot provide services across the county lines. This became a serious issue when Pájaro residents were evacuated following the March 2023 levee breach. Residents were initially instructed to move to Salinas, a city an hour away which was itself experiencing flooding, so residents instead crossed into Watsonville which was “right there,” according to a City of Watsonville Public Works Official interviewed for this study. However, in crossing the single bridge into Santa Cruz County, residents found they lacked the ability to cross the boundary to their homes again. The Sheriff for Santa Cruz County had placed a barrier on this bridge prohibiting crossing for jurisdictional and safety reasons. In this way, during the floods, jurisdictional boundaries created a fractured landscape of services and protections that caused displaced residents to be on the “wrong side” to receive services or return home for several weeks.

Opportunities and Future Hopes for the Pájaro Valley

Our third research question sought to uncover the hopes for the future of the Pájaro Valley’s unincorporated communities for a more equitable future for the region. Here, we discuss two key types of findings. First are three strategies which were shown to positively assist residents in their flood recovery. Second are the visions and hopes kindly shared with us for the future of the region.

Strategy 1: Cultivating Local Experts and Diplomacy

As mentioned under Barrier 1, the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency Official noted that their agency has been unique in developing the institutional know-how to promote the needs of the region, and its unincorporated communities with high flood risk. The agency has been operating since 2021 and during that limited time, they have landed a number of major policy wins—including improved levees and expedited timelines for the region—through their political advocacy with the State of California. The agency also advocated for and won a rare California Environmental Quality Act exemption for levee repairs by working closely with their regional state representatives. This exemption allowed proposed levee improvements to advance through environmental impact studies more quickly. While repairs look slow to the community, levee improvements have proceeded rapidly, with two breaches fixed within a year of the disaster, and the third breach nearly complete. The agency’s growing expertise and active authority is a magnificent opportunity for the region but, as many have noted, their successes need to be more clearly communicated to Pájaro Valley residents.

Strategy 2: Community Cohesion for the Community Itself

Following the Winter Storms, local capacity growth has not been limited to government agencies but is growing within the community as well. As the Regeneración organizer noted: “There's people taking leadership, there's people really finding their voice, there's people stating demands.” Through Pájaro’s recovery, there has been a notable shift in the residents’ sense of community cohesion that has strengthened ongoing initiatives. For example,, the community-based organization Casa de Cultura is a mutual support organization in Pájaro that has received increased recognition and trust from residents following the levee breaches. The researchers also saw firsthand during the week after the levee breach that farmworkers in Watsonville hosted a daily barbeque to feed displaced Pájaro residents and local churches housed, fed, and clothed Pájaro residents unable to return home for belongings. As a Watsonville Public Works official stated during an interview, “No one's going to save us here, which ‘save’ is the wrong word, but in terms of: we need to help ourselves.” There is a growing sense of agency and determination amongst Pájaro Valley residents.

Strategy 3: Keep the Media’s Attention

A nearly ubiquitous sentiment across research participants in all sectors was the critical importance of the media in bringing to light the plight of Pájaro’s residents following the levee breach. Almost all our respondents mentioned their critical role in reaching out to media outlets. A Watsonville Public Works official noted the significance of President Biden’s visit following his Disaster Declaration, in which Governor Newsom recognized multiple flood events across multiple rural communities (including the Pájaro Valley) in one declaration. For a small, rural region, media attention brought more resources and assistance to residents and prevented their plight from being hidden.

Hopes and Visions for the Future

Three major hopes and visions for the future of the Pájaro Valley were kindly shared by our research participants: (1) seeing the Pájaro River as a place of connection which allows the community to truly live and thrive alongside the water; (2) centering climate justice in hazard mitigation and disaster recovery; and (3) improved disaster communication and planning. It is striking that all three visions are eminently attainable, given resources and advocacy.

Amongst these articulations of the future, one retelling of the region's past stands out. Mr. Hall, long-term resident of Pájaro, noted:

I grew up here in the ‘50s, you know I was born in ‘54. So ‘50s and ‘60s, this was all open behind here, I [could] walk down to the [Pájaro] river and I went hunting and fishing. I’d catch steelhead this big and they used to dam up a spot right where the Corralitos [Creek] comes in down here and all the kids would go swimming and stuff down there.

A Regeneración organizer also emphasized the importance of climate justice and recreational spaces. The Pájaro Valley will be affected by rising sea levels and increased frequency and magnitude of atmospheric rivers in over the coming decades—both of which raise the risk of flooding. The vision for their future requires living differently with water in a manner that faces climate change and prioritizes the just and equitable treatment of the region’s unincorporated communities. Improved communication and coordination to meet community needs requires communication through all languages of the community. The Regeneración organizer stated that they needed “better coordination and communication between all parties and just really getting clear, accurate, understandable information out to the community through multiple channels in all the languages that are represented in the area.”

Lastly, we heard a variety of hopes aimed at better planning and coordination between the region’s various governments, agencies, and community-based organizations. There were hopes for leaders to emerge on topics like disaster communications, hazard mitigation, affordable and safe housing, and access to healthy foods. Overall, as the Regeneración organizer noted, the hopes for the future recognize that their risks of disaster are tied to daily life:

We need to address the underlying issue, not just respond to the disasters, but just have comprehensive education and information about the climate emergency and act in a unified and cooperative way to eliminate fossil fuels from the Pájaro Valley and the world…and address this like an emergency and actually head towards preventing future disasters.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice and Policy

Our results point to three policy and planning implications for flood recovery and hazard mitigation in unincorporated areas. First, strong regional-level agencies can greatly shift the power dynamics between incorporated cities and unincorporated areas. While regional-scale agencies like the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency are rare in the United States, it is evident that they are best situated to structure and fund mitigation efforts, while also assisting in rapid recovery. These organizations can provide a local name for programs and funding, while also actively advocating for the needs of unincorporated communities at the state and federal levels.

Second, local networks and organizations are critical for successful recovery in unincorporated areas and small towns, especially if they lack strong regional representation. This mirrors previous research (e.g., Olshansky & Johnson, 2014; Rumbach et al., 2016), but here we found that local capacity is even more important for unincorporated areas, especially for disaster communications, perishable data collection, and receiving expert assistance. However, if county, state, or federal agencies or other non-local organizations depend on local networks and organizations strongly to assist in provide services (especially within unincorporated areas), fair compensation is needed. State agencies and county governments need to be prepared to compensate local organizations for their time and resources, on a reasonable timeline.

Third, there is a need to expand data collection efforts on hazards beyond incorporated areas in California, and more broadly across the United States. The dearth of information on unincorporated areas and the risks they face significantly hampers our ability to model hazards, create informed mitigation plans, and to visualize continuous systems of hazards cutting across jurisdictions. Most critically, this will help us to answer the important questions that unincorporated communities are asking relative to the real risks they face.

Limitations

This research project experienced several setbacks. Initially, to answer research questions 1 and 2, we planned a series of community visioning workshops. However, given the compressed timeline to collect this perishable data and the delayed Institutional Review Board process at our institution, we were unable to collect these responses from the broader Pájaro Valley community. While our research respondents are all Pájaro Valley residents, our data here is restricted to the views of those holding leadership and/or public positions. There may be additional insights to glean by capturing a larger volume of resident responses.

Future Research Directions

Future areas of research should center context-appropriate approaches to hazard mitigation and recovery in unincorporated areas that includes approaches to mitigation and recovery built in full acknowledgement of the implications wrought by a lack of city governance. This report will be shared with our community partners and research participants to structure our “next steps” for creating rural hazard mitigation tools and policies. These next steps have been funded by CalWater and the U.S. Geological Survey into 2025 to expand our research throughout the Bay Area of California. Additionally, we are seeking National Science Foundation funding to continue expanding the research’s geographic focus. Lastly, there is also a need to gain more perspectives from residents in unincorporated areas. We are continuing efforts to hold our community workshops in Pájaro in concert with our governmental and community partners.

Acknowledgments. The authors would like to thank CalWater and U.S. Geological Survey for their additional funding to continue and expand this work. We would also like to thank Pájaro residents and the following institutions and organizations for their assistance: Regeneración, Watsonville Wetlands Watch, City of Watsonville, Santa Cruz County, Pájaro Regional Flood Management Authority, and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers-San Francisco.

References

-

Los Angeles County. (2024). Unincorporated Areas Services. https://ceo.lacounty.gov/master-planning-unincorporated-area-services/ ↩

-

Toukabri, A. & Medina, L. (2020). America: A Nation of Small Towns. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/05/america-a-nation-of-small-towns.html ↩

-

Bukvic, A., & Borate, A. (2021). Developing coastal relocation policy: Lessons learned from the FEMA Hazard Mitigation grant program. Environmental Hazards, 20(3), 279–299. ↩

-

Seong, K., Losey, C., & Gu, D. (2022). Naturally resilient to natural hazards? Urban–rural disparities in Hazard Mitigation grant program assistance. Housing Policy Debate, 32(1), 190–210. ↩

-

Cross, J. A. (2001). Megacities and small towns: Different perspectives on hazard vulnerability. Environmental Hazards: Human and Policy Dimensions, 3, 63–80. ↩

-

Hendricks, M. D., Newman, G., Yu, S., & Horney, J. (2018). Leveling the landscape: Landscape performance as a green infrastructure tool for service-learning products. Landscape Journal, 37(2), 19-39. ↩

-

Horney, J., Nyugen, M., Salvesen, D., Dwyer, C., Cooper, J., & Berke, P. (2017). Assessing the quality of rural Hazard Mitigation plans in the Southeastern United States. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 37(1), 56–65. ↩

-

Lapping, M. B., & Scott, M. (2019). The evolution of rural planning in the Global North. In M. Scott, N. Gallent, & M. Gkartzios (Eds.), The Routledge companion to rural planning (28–45). Routledge. ↩

-

Frank, K. I., & Hibbard, M. (2017). Rural planning in the twenty-first century: Context-appropriate practices in a connected world. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 37(3), 299–308. ↩

-

Rivera, D. Z. (2023). Unincorporated and underserved: Critical stormwater infrastructure challenges in South Texas colonias. Environmental Justice, OnlineFirst. ↩

-

Gomez-Vidal, C., & Gomez, A. M. (2021). Invisible and unequal: Unincorporated community status as a structural determinant of health. Social Science & Medicine, 285, 114292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114292 ↩

-

Anderson, M. W. (2008). Cities inside out: Race, poverty, and exclusion at the Urban Fringe. UCLA Law Review, 55(5), 1095–1160. https://www.uclalawreview.org/cities-inside-out-race-poverty-and-exclusion-at-the-urban-fringe/ ↩

-

Olshansky, R., & Johnson, L. A. (2014). The evolution of the federal role in supporting community recovery after U.S. disasters. Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(4), 293–304. ↩

-

Rumbach, A., Makarewicz, C., & Németh, J. (2016). The importance of place in early disaster recovery: A case study of the 2013 Colorado floods. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 59(11), 2045–2063. ↩

-

United States Census Bureau. (2020). Decennial Census P.L. 94-171 Redistricting Data [Data set]. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/about/rdo/summary-files.html ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023a, January 14). California Severe Winter Storms, Flooding, Landslides, and Mudslides [DR-4683-CA]. Federal Disaster Declaration. https://www.fema.gov/disaster/4683 ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023b, April 3). California Severe Winter Storms, Straight-line Winds, Flooding, Landslides, and Mudslides [DR-4699-CA]. Federal Disaster Declaration. https://www.fema.gov/disaster/4699 ↩

-

Oulahen, G., Vogel, B., & Gouett-Hanna, C. (2020). Quick response disaster research: Opportunities and challenges for a new funding program. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 11, 568–577. ↩

-

Adams, R. M., Evans, C. M., & Peek L. (2021). Broader Ethical Considerations for Hazards and Disaster Researchers. CONVERGE Training Modules. Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://converge.colorado.edu/resources/training-modules ↩

-

Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409-428. ↩

-

California School Dashboard. (n.d.). District performance overview: Pájaro Valley Unified. https://www.caschooldashboard.org/reports/44697990000000/2023 ↩

-

Guild, T. (2024, June 14). Annual homeless census shows positive trends, with bad news. The Pajaronian. https://pajaronian.com/pit-count-results-2024/ ↩

Rivera, D. Z., Breder, E., & Dodd, A. (2024). Toward Equitable Recovery for Unincorporated Areas: Lessons From California’s 2023 Winter Storms. (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 367). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/toward-equitable-recovery-for-unincorporated-areas

Acknowledgments

The Quick Response Research Award Program is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF Award #1635593). Opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations produced by this program are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or Natural Hazards Center.