Thundering Forward: Remembering Community Tragedy in Huntington, West Virginia

Publication Date: 2015

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to learn more about the meaning associated with memorials that commemorate times of university campus and community crisis. Focusing on the November 1970 plane crash that killed 75 passengers affiliated with Marshall University and Huntington, WV, there were two major goals of this study: (a) to inform how communities heal and move forward after a tragedy, and incorporate the memory of that tragedy into their revised identity; and (b) to offer insight into the purposes and functions of memorials—both physical structures and annual commemorative events—within a community. Interviews were conducted with 17 individuals connected to the Marshall and Huntington communities, and observations were conducted during the 45th anniversary ceremony commemorating the plane crash. Findings from this study reveal how memorials have aided the crisis recovery process and how people interact with and make meaning of the existing memorials. The results of this study may be used by local officials and campus administrators who need to make future decisions and take actions that help a community to both heal and move forward after a tragedy.

Introduction and Context

November 14, 2015 marked the 45th anniversary of the plane crash that resulted in the death of the majority of the Marshall University football team and coaching staff, along with several Huntington, WV community members. In total, 75 people died in that crash. This crash is yet recorded as the largest sports-related air disaster in U.S. history, and was the subject of a 2006 movie entitled “We Are Marshall.” As such a large-scale tragedy, this plane crash had a major influence on the lives of people near and far from Huntington. A participant who grew up in southeastern Ohio, about 40 miles from Huntington, recounted the news of the plane crash:

I was in high school, and it happened late at night, so my parents let me know the next morning. So we were just—oh my gosh!—we were just devastated. There was a lot of prayer and a lot of people just, you know, there was just so much grief in the area. So you would have had to been—I don’t know—in another world not to have felt the effect that it had on the entire community; not just Huntington, but the contiguous community also. The tri-state [Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky] area was just devastated. There were so many people that knew somebody. So if you didn’t know someone directly, you may have known their aunt, their uncle.... It was hard.

Although the plane crash was 45 years ago, the emotion and memory surrounding it is still palpable in Huntington, WV and on the campus of Marshall University. Not only are there physical markers that serve as reminders of the crash and annual commemorative events and activities, but every first-year student learns about the crash and watches “We Are Marshall” as part of an introductory seminar course.

A Quick Response Grant from the National Hazards Center at University of Colorado Boulder was used to visit three physical memorials in Huntington, and attend the annual ceremony that commemorates the lives lost and the 1970 football season. This visit took place from November 13-15, 2015, the days surrounding the anniversary ceremony. As the 45th anniversary of the plane crash, 2015 was a crucial year to collect data surrounding this tragedy in Huntington. Crisis anniversaries usually include special events and encourage large crowds (including those integral to the actual crisis response and original memorial decisions) to pilgrimage. Given that the annual efforts to remember this tragedy and commemorate the lives lost were consistent over the 44 years preceding 2015, the anniversary year drew a large crowd of people whose lives were directly or indirectly affected by the plane crash.

The Huntington/Marshall Town/Gown Relationship

The current website for the City of Huntington refers to Marshall University as “one of the largest employers in town and a major contributor to the heart and soul of the community” (City of Huntington, 2015, “Community Profile”1). The website goes on to refer to the plane crash as a “tragedy for the university and community.” A strong town/gown relationship is important for cities and universities, such as Huntington and Marshall, that rely heavily on each other for survival. In the words of one participant, who is a resident of Huntington, “It’s just natural to support Marshall. Everybody does here. It’s amazing—if you just wear a green sweatshirt, you’re dressed….you’ll fit in.” The Huntington/Marshall relationship has been a tightly woven one for several decades. This is evidenced by the fact that 24 of the deceased from the fatal 1970 plane crash were Huntington residents who were fans and supporters of the Marshall “Thundering Herd” football team. The memorials at the center of this research are located in both city and university spaces. Using memorials as a focal point, this study helps to inform how communities heal and move forward after a tragedy involving mass death, and how incorporating the memory of that tragedy serves to revise their identity.

Three Memorial Sites

The three memorials included in this research are unique and symbolically located. One memorial is a fountain located on the campus of Marshall University; one is a cenotaph and seating area in a local cemetery; and the other is a marker and resting place at the crash site.

Memorial Site at Marshall University

The fountain, which is a regular stop of campus tours, is located directly outside of one of the main entrances to the University’s student center and has a grand presence. The exterior of the fountain is a large marble square. At the center of the fountain is a distinctively-shaped sculpture that contains 75 individual points at its top—one point for each life lost in the crash. Water bubbles up from within this sculpture and falls into the marble basin that surrounds it. Each November 14, a commemorative ceremony (dubbed by community members as the “Fountain Ceremony”) occurs near the fountain. At the close of the ceremony, the fountain is turned off until the following spring. A bronzed plaque extending out of the waters in the fountain contains a brief summary of the plane crash and the names of the 75 deceased. One of the messages inscribed on both this plaque and on the second memorial described below (a cenotaph in the community cemetery) are the words: “They shall live on in the hearts of their families and friends forever, and this memorial records their loss to the university and to the community.”

Figure 1. On the morning of the 45th anniversary memorial, November 14, 2016, workers clean the fountain before the start of the annual ceremony. Floating bouquets have been placed inside the fountain for the ceremony

Figure 1. On the morning of the 45th anniversary memorial, November 14, 2016, workers clean the fountain before the start of the annual ceremony. Floating bouquets have been placed inside the fountain for the ceremony

Figure 2. The memorial wreath and flowers wait inside the entrance to the Marshall University student center. During the “Fountain Ceremony,” this wreath sits in front of the fountain and the each of the bucketed roses (one for each of the 75 deceased) is individually carried, by a pre-selected person, from the student center to the fountain and placed on the rim of the fountain.

Figure 2. The memorial wreath and flowers wait inside the entrance to the Marshall University student center. During the “Fountain Ceremony,” this wreath sits in front of the fountain and the each of the bucketed roses (one for each of the 75 deceased) is individually carried, by a pre-selected person, from the student center to the fountain and placed on the rim of the fountain.

Figure 3. People begin to gather for the start of the ceremony. Seating is limited, so early arrival is required for those who prefer not to stand. The front rows are reserved for family members and special guests.

Figure 3. People begin to gather for the start of the ceremony. Seating is limited, so early arrival is required for those who prefer not to stand. The front rows are reserved for family members and special guests.

Figure 4. The wreath is ceremonially carried toward the fountain.

Figure 4. The wreath is ceremonially carried toward the fountain.

Figure 5. A current Marshall University football player lays one of the 75 roses at the fountain.

Figure 5. A current Marshall University football player lays one of the 75 roses at the fountain.

Figure 6. All 75 roses lay on the fountain’s edge at the end of the annual ceremony.

Figure 6. All 75 roses lay on the fountain’s edge at the end of the annual ceremony.

Memorial Site in the Local Cemetery

A second memorial is located in the Spring Hill Cemetery in Huntington, WV. The centerpiece of this memorial is a granite cenotaph, inscribed on all four sides, and flanked by two granite benches. At this site are buried six members of the team whose bodies were unrecognizable after the crash, others who perished in the crash, and other teammates (not on the plane that crashed) who died in later years. In front of the cenotaph are six unmarked graves, one for each of the unidentified teammates, and a stone plaque engraved with all six names. The inscription on the front of the cenotaph again recognizes the six unidentified players; the inscription on other sides list the names of all those who perished in the crash. This memorial is located at the highest point in Spring Hill Cemetery and is encapsulated by a circular roadway. At the end of the annual Fountain Ceremony, the memorial wreath displayed during the ceremony is relocated to the cenotaph and family members of the deceased gather to greet visitors to the memorial.

Even though located off-campus, this memorial is actively recognized by the campus community. Each year on September 11, the student body holds a memorial walk during which they march from the campus recreation center to the cemetery and place 75 U.S. flags in the ground at the border of the circular plot containing the cenotaph. According to a Student Government officer, last year’s walk attracted approximately 150 attendees. Additionally, the Thundering Herd football team takes an annual run to the cemetery: “The Herd team has made this run every year, along with a viewing of the Warner Bros. movie, “We Are Marshall,” to remind the team of what was lost here and where the program rose from” (Woodrum, 2015, p. 22). While these organized pilgrimages to the cenotaph happen annually, this memorial is also simply a staple of the Huntington community, with residents reporting occasional strolls through the cemetery and past the memorial.

Figures 7 and 8. On the morning after of November 15, 2015, new paraphernalia has been left at the foot of the cenotaph, including tickets from the previous day’s home football game. The next set of photographs are from the memorial at the crash site.

Memorial at the Crash Site

A final memorial is located near the site of the plane crash. The crash occurred while the flight was descending for landing into the regional airport in Huntington. Located on the side of a state highway, the memorial is a wooden deck—consisting of a landing and railings that outline the perimeter—that is fitted between a break in the metal barriers flanking the edge of the highway. The deck is painted in Marshall University’s signature green and contains a flagpole that flies the U.S. flag at the top and a Marshall University flag displaying the athletic mascot below. In the center of the deck is a historical marker sponsored by the Wayne County Genealogical and Historical Society and the West Virginia Division of Archives and History. The marker, shown below, contains a history of the plane crash. Each November 14, family members of those who perished in the plane crash gather at this site at 7:30 p.m. to be together at the time that they lost their loved ones. According to one study participant who is a campus employee, the University maintains this site, ensuring that the area is manicured.

Figures 9 and 10. View of the memorial platform and plaque on the side of a roadway that is near the site of the November 14, 1970 plane crash.

Figure 11. Marker at the crash site memorial. Two flags, one US flag and one containing the Marshall University athletic logo, fly at the memorial and can be seen in the background.

Figure 11. Marker at the crash site memorial. Two flags, one US flag and one containing the Marshall University athletic logo, fly at the memorial and can be seen in the background.

Figure 12. Many mementos have been left at the crash site memorial by visitors. Pictured here ae a tribute banner to the 75 crash victims, bouquets of white flowers, a black wreath and magazine, and several coins and a glow stick on top of the bannister railing. Coins are often left at the sites of memorials and graves as a signifier to family members and other visitors that others have been present at those sites. The glow stick was likely left behind by visitors who were at this site on the evening of November 14, 2015 at the time of the crash. This photograph was taken on the afternoon of November 15, 2015.

Figure 12. Many mementos have been left at the crash site memorial by visitors. Pictured here ae a tribute banner to the 75 crash victims, bouquets of white flowers, a black wreath and magazine, and several coins and a glow stick on top of the bannister railing. Coins are often left at the sites of memorials and graves as a signifier to family members and other visitors that others have been present at those sites. The glow stick was likely left behind by visitors who were at this site on the evening of November 14, 2015 at the time of the crash. This photograph was taken on the afternoon of November 15, 2015.

As part of this project, we visited each of these three memorial sites, participated in the commemorative events on November 14, 2015, and interviewed people connected to Marshall University, the City of Huntington, WV, and the tragedy of the 1970 plane crash. In addition to the Fountain Ceremony on the 2015 anniversary of the crash, the Thundering Herd football team played a home game. We attended a tailgating event with one of the study participants who lost two family members in the plane crash, and attended the football game. During the game, there were several tributes to the 1970 football team, in addition to the visual reminders of the 1970 season, team, and plane crash that exist within the stadium. Photographs depicting some of these visual reminders are included below.

Figures 13 and 14. The words “We Are Marshall,” also the title of the 2006 film detailing the story of the plane crash and the University’s response and recovery, can be seen many places throughout the campus. These two photographs show the words on the side of a building in the athletic complex and embroidered on a flag being flown among other Marshall University flags and pennants in the tailgating area.

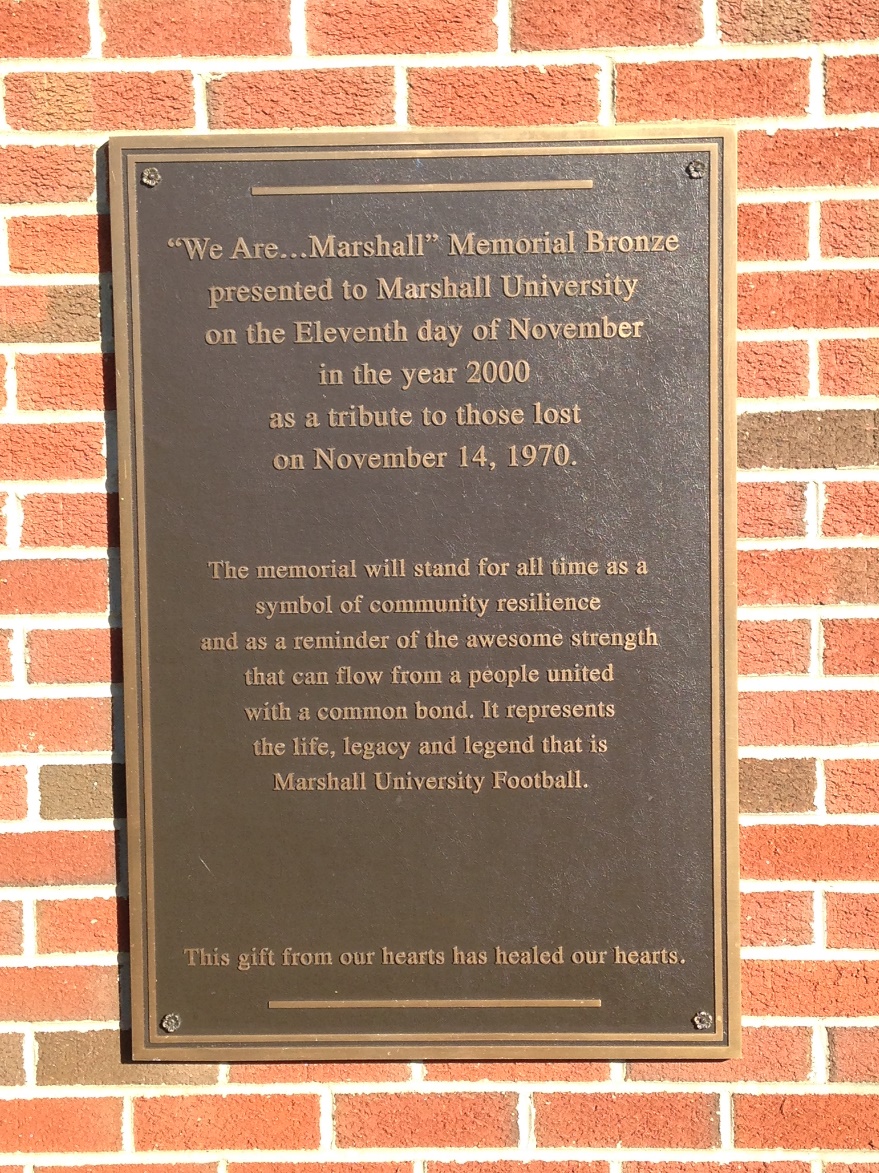

Figure 15. The words “We are Marshall” can again be seen as a prominent part of this memorial that is displayed on the exterior of the football stadium. Figures 16 through 19 show the other portions of this memorial in more detail.

Figure 15. The words “We are Marshall” can again be seen as a prominent part of this memorial that is displayed on the exterior of the football stadium. Figures 16 through 19 show the other portions of this memorial in more detail.

Figure 16. The bronze sculpture that is the focus of the memorial shown in Figure 15 depicts three football players atop a thundering herd of buffalo.

Figure 16. The bronze sculpture that is the focus of the memorial shown in Figure 15 depicts three football players atop a thundering herd of buffalo.

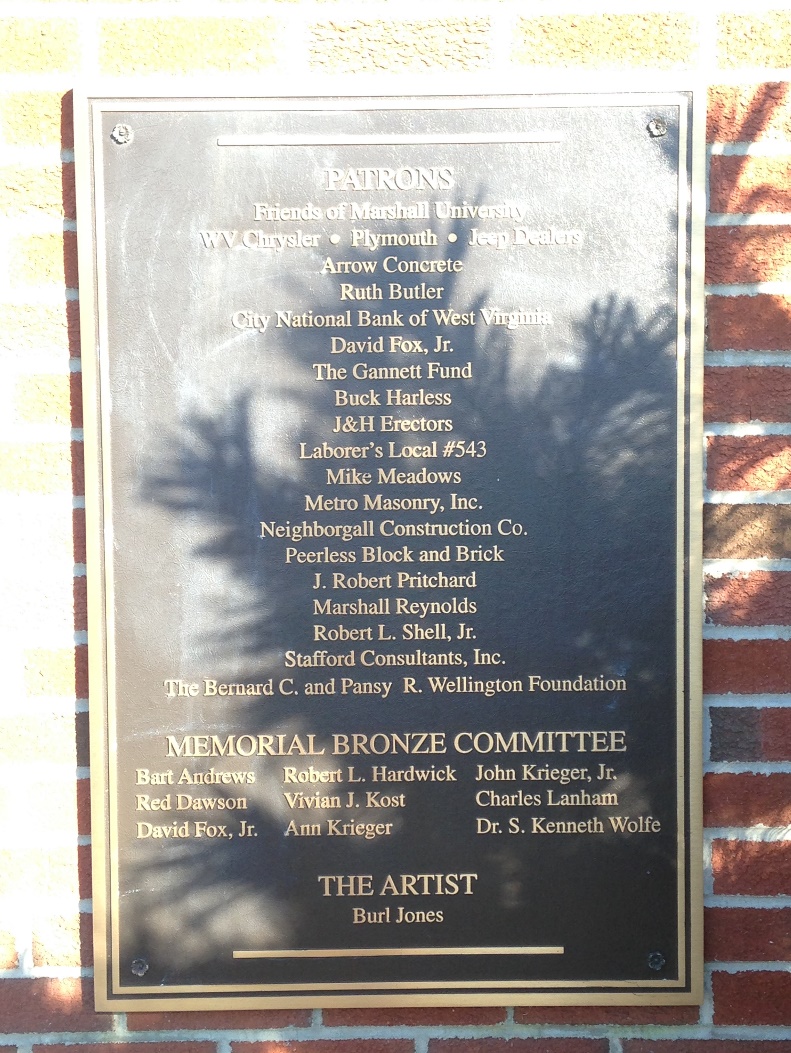

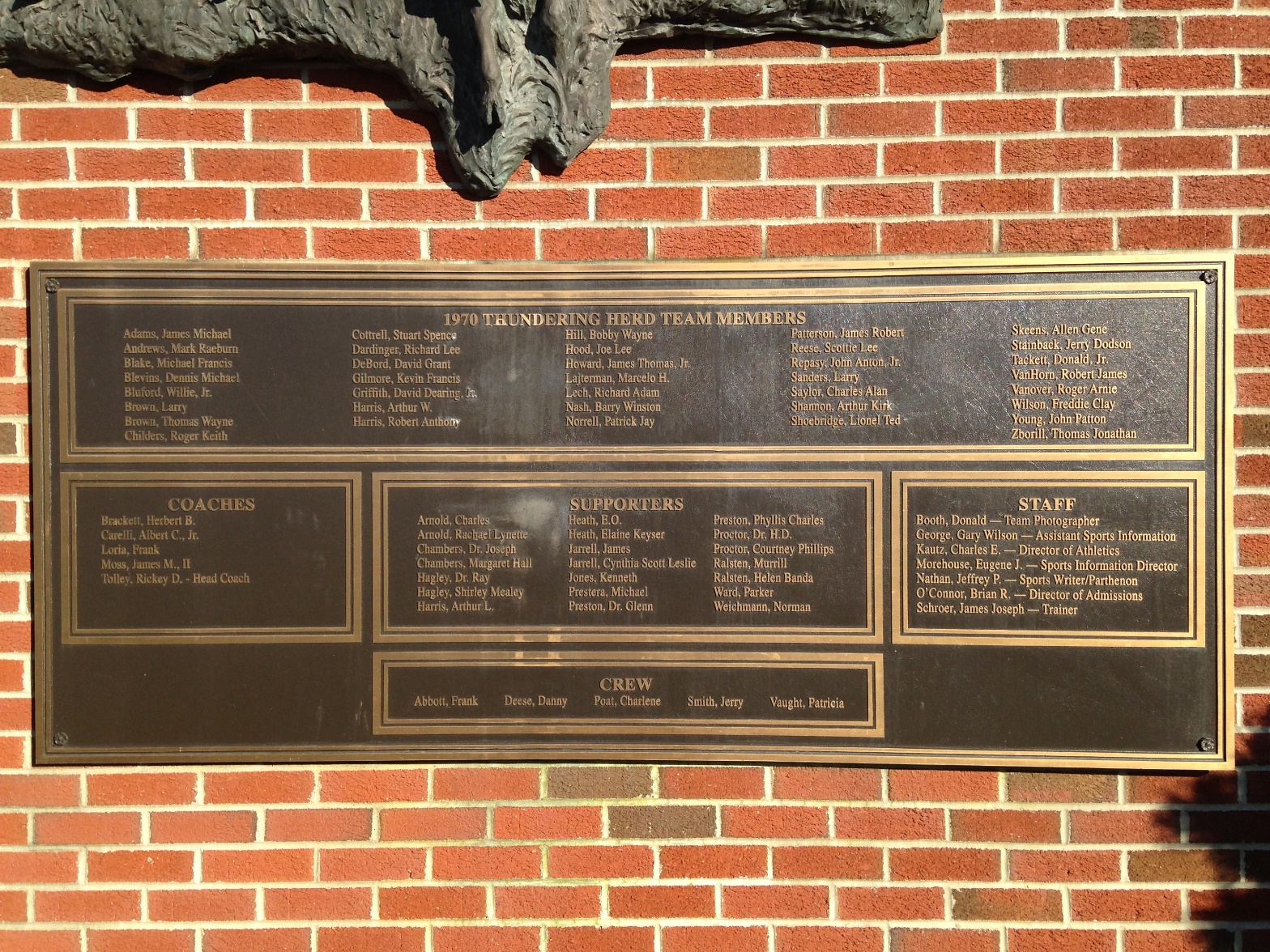

Figures 17 and 18. TThe plaques that flank either side of the memorial note the purpose of the memorial and the groups and individuals that played a role in the creation of the memorial.

Figure 19. The main text display lists the names of all 75 crash victims and their association to the football team.

Figure 19. The main text display lists the names of all 75 crash victims and their association to the football team.

Figure 20. One of the many banners hanging from the rafters inside the stadium is dedicated to the 1970 Thundering Herd football team. This banner contains the team picture and a picture of the memorial fountain.

Figure 20. One of the many banners hanging from the rafters inside the stadium is dedicated to the 1970 Thundering Herd football team. This banner contains the team picture and a picture of the memorial fountain.

Figure 21. Researchers Greg Cherry and Mahauganee Shaw in the stands at the November 14, 2015 Thundering Herd football game.

Figure 21. Researchers Greg Cherry and Mahauganee Shaw in the stands at the November 14, 2015 Thundering Herd football game.

Literature Review

Theoretically, this research helps to inform bodies of literature on crisis management, organizational remembrance and forgetting, and memorialization. Within the realm of crisis management, this study will better inform the crisis recovery process. Crisis management includes any actions taken by an organization to prepare for, mitigate, respond to, recover and learn from the impact of a crisis (Zdziarski, Rollo, & Dunkel, 20073). The main focus of this project is the creation of permanent commemorative structures and events (i.e., memorials), actions usually undertaken during the crisis recovery phase. In focusing on the act of community remembrance through memorialization, this study centers on recovery decisions and actions that become infused into an institution’s standard operations.

In addition to theories of crisis recovery, there is a substantial body of literature from the field of management revolving around the concepts of organizational memory, knowledge, and learning. Within the body of literature on organizational remembrance is a growing strand of research on organizational forgetting (Bowker, 19974; Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 20115; Fernandez & Sune, 20096; Kleiner, Nickelsburg, & Pilarski, 20127; Martin de Holan, 2011a8, 2011b9; Martin de Holan, Phillips, & Lawrence, 200410; Martin de Holan & Phillips, 2004a11, 2004b12; Wong, Cheung, Yiu, & Hardie, 201213). A campus administrator reflecting on the institutional response to a major campus crisis, once remarked: “There are reasons, after a campus crisis, that institutions do not want to remember what happened” (personal communication, J. Howe, January 31, 2013). This quote was offered during a discussion of letting the one year anniversary date of a major campus crisis pass without mentioning its occurrence, and subsequently breathing a sigh of relief when local media also neglected to mention the anniversary. The decision to not relive “what happened” by announcing an anniversary, erecting memorial structures, or implementing commemoration events is a tactic sometimes use to spark the act of forgetting, both on the institutional level and among the general public. Given that there are campus crises that institutional leaders intentionally forget, this study examines a tragedy that is intentionally remembered through the act of memorialization.

Regarding reasons that institutions may want to remember a crisis, previous research suggests that the memorials at the center of this study may (a) help to foster community around the emotions invoked by a crisis and (b) serve as reminders of poignant times past to all who visit. However, this literature focuses largely on impromptu shrines and memorial sites erected spontaneously by the members of the general public who leave tributes and gifts in remembrance of tragic events (Reid & Reid, 200114; Santino, 200615; Sturken, 200716). It has been noted that public memorializations, such as impromptu shrines and roadside death memorials, both “provide a sense of comfort in the face of fear and loss” (Sturken, 2007, p. 86) and “provide a variety of mourners a way to express their intense grief and memorialize the deceased” (Reid & Reid, 2001, p. 35414). This suggests that, for institutions that choose to remember tragic events, erecting memorial structures or organizing memorial events may be a helpful way to both acknowledge tragedy and encourage healing. This study’s focus on institutional remembrance and memorialization will advance the body of knowledge on memorialization by moving beyond prior research on spontaneous memorials to those that are planned and sanctioned.

Research Purpose and Questions

The goal of this research is to offer insight into the purposes and intended functions of memorials to a community that permeates the imaginary boundaries of city and university. It also sheds light on how people actually interact with existing memorials, and the meanings associated with these interactions. This leads to many applied benefits; specifically, the results of this research are useful for local officials and campus administrators who need to make future decisions and take actions that help a community to both heal and move forward after a crisis. Currently no existing research examines university campus memorials, or the role these memorials play within campus environments; thus, this study also helps to fill this gap in the literature. With intent to speak with people who belong to the communities impacted by this plane crash, we embarked upon this data collection experience with three research questions:

(1) How do people who pilgrimage to the 45th anniversary of the November 14, 1970 Marshall University plane crash make sense of that experience? (2) What roles do the memorial structures and events play in the life of the community? What about in the lives of those who pilgrimage? (3) How have the memorials aided the crisis recovery process?

The goals of these three questions were to home in on the role that the memorials play in the healing process of a community of people who are connected by tragedy, and to understand why people make the annual effort, from near and far, to participate in commemorative events.

Methods

A case study method is being used to investigate institutional and community remembrance through creation of events and erection of structures intended to commemorate experiences of crisis. Specifically, a descriptive case study is used to investigate a phenomenon and the real-life setting in which it occurs (Yin, 200917); in this study the phenomenon investigated is community (including both a university and its city) remembrance after crisis in the setting of Huntington, WV/Marshall University. The research questions outlined above guided the data collection process. When designing this study, we believed that 2015 being the 45th anniversary year was an indicator that the annual commemoration was likely to be both well-attended by people who were ideal potential participants for this study and the best opportunity in several years to recruit participants and conduct interviews. Two main factors influenced our considerations: (a) the special anniversary year was likely to draw a wide range of people involved with the memorial over the decades, and (b) many people affiliated with the campus in 1970, and the original memorial decisions, are now elderly and may either not be alive for or mobile during the next major anniversary.

Data Sources

We drew upon two sources of data in this study: information from local and national news sources regarding the anniversary year and interviews. Interview participants included both people who were involved in the planning and implementation of the memorial structures or commemorative event, those attending the 2015 memorial event, and those who have attended past memorial events. The final groups of interviewees—those attending the recent or past memorial events—includes both individuals who live in Huntington, WV and those who traveled to town for the anniversary events. In total, we interviewed 17 people for this study.

Each individual was asked to participate in a single interview. All interviews were semi-structured and audio recorded (Stake, 201018; Yin, 200917). Face-to-face interviews were conducted with all participants interviewed between the day preceding the annual memorial ceremony and the day following the ceremony. Interviews conducted after the site visit occurred over the phone. Interviews ranged in length from approximately 10 to 30 minutes. While some interviews were scheduled prior to the site visit, other participants were recruited on site from the group of people attending the memorial ceremony.

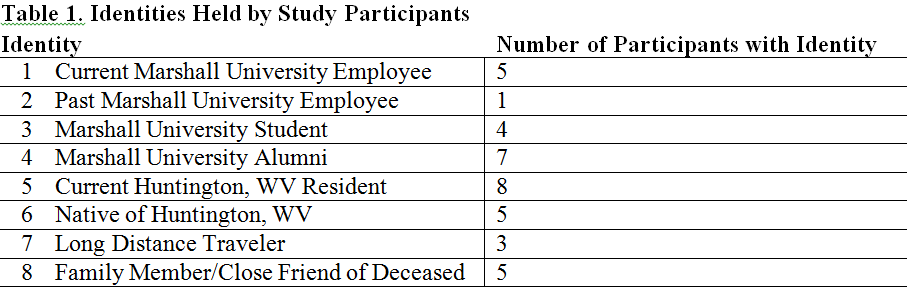

Participants had multiple connections to the plane crash and the affected communities. They included past and current employees of Marshall University, students and alumni of Marshall University, family members and close friends of those who perished in the crash, natives and residents of Huntington, and people who traveled long distances to attend the ceremony. Table 1 shows the numbers of participants (in column 2) with these various forms of connections to the crash and the community (column 1).

Data Analysis

Following the submission of this initial report, all interviews and data will be transcribed and coded into themed categories (Saldaña, 200919). These themes will be used to note where study participants both converge and diverge in the ways they describe the purposes of the memorials and the meanings they associate with the memorials. It was originally believed that the first question—How do people who pilgrimage to the 45th anniversary of the November 14, 1970 Marshall University plane crash make sense of that experience?—could only be answered through analyzing the responses of the individuals who traveled long distance to the memorial ceremony. However, the preliminary findings presented below reveal that participating in the ceremony is a meaningful and cathartic experience for most participants; thus, this idea of pilgrimaging is not necessarily connected to distance traveled.

Synthesizing the responses of all participants will allow the second question—What roles do the memorial structures and events play in the life of the community? What about in the lives of those who pilgrimage?—to be answered. It was originally hypothesized that those responsible for planning the memorial and those who travel to the memorial events would diverge in points of their thinking, but that both groups would converge with the group of memorial attendees who are long-time Huntington residents. This assumption has also been disproven by the preliminary findings. All participants seemed to have similar beliefs about the role of the memorials in the lives of the general public; however, there was divergence in the role of memorials to individuals with close family or friendship ties to the deceased and those who do not have these ties. The final research question—How have the memorials aided the crisis recovery process?—is to be answered by aligning the themes associated with the purpose and meaning of the memorials to the literature on crisis recovery that specifies the needs of post-crisis communities (e.g., community remembrance and healing, the reduction of fear and grief, psychological recovery, etc.). The findings below highlight themes that were apparent in the data collection process and in our preliminary analysis.

Preliminiary Findings and Discussion

The significance of the November 14, 1970 plane crash is engrained in the lives of people affiliated with the City of Huntington and with Marshall University. Every study participant spoke freely and eloquently about the impact of that plane crash on their lives, regardless of their age and the point at which they learned about the crash. The community has continued to keep the memory of the crash alive and to teach newcomers about it through the use of various mechanisms, including the memorial sites and ceremony. The findings presented here detail the reported reasons people attend the annual ceremony, the role of the memorials in the community, and insights regarding how the memorials have aided the crisis recovery process.

Reasons for Attending the Annual Memorial Ceremony

Overwhelmingly, participants noted attending the memorial ceremony, in 2015 or past years, as a way to honor the memory and lives of those who perished in the crash. This is seen in the ways that participants described their reasons for either attending the ceremony or recommending that others attend:

To honor and to pay a tribute to the lives of the people who were lost in the crash…because it’s something that never seems to be forgotten. (Participant with identities 6 and 7)

I always tell students in my freshman UNI class the one thing that I really want them to do is come to the Fountain Ceremony, and they will feel the importance of being a Marshall student here at this institution. You feel it on the day. It grabs you. It takes hold of you. (Participant with Identities 1, 4, and 5)

I don’t know if I’ve ever given it true thought to ‘what is the meaning of this?’.... But to me, to me, it is tremendously meaningful when I look around at the crowd, not at the people I expect to see. It’s impressive and touching to me how many 18 to 25 year olds I see who have taken the time to come and attend and who are paying attention and not playing on their cell phone or tablet or just there because it’s something to do or because their teacher required them to be there. You know, that, to me, is what makes this one different. It’s not like so many [other] services and memorials. (Participant with Identities 4, 5, 6 and 7)

While most people expressed great meaning associated with participating in the ceremony, there was one participant who felt differently:

I have purposely stayed away from those kinds of things.... I think it’s important for those whose make up is such that it helps them. There are people for whom it’s absolutely necessary to be there. It isn’t for me. [There are people who find] it very, very helpful. Not all of us do. (Participant with Identities 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8)

The participant quoted above, holding Identities 4, 5, 6 and 7, who has participated annually in the ceremony since the 1970s noted that some of their other relatives have not ever participated:

There’s five of us [siblings], and you know, my [older] brother has never attended one of these to this day.... And my middle sister has real troubles with it every year.... everybody deals with things in their own way, shape, or form, and they’re all different. That’s just the way it goes.

These were the only two interviews in which participants noted reasons someone would choose not to attend the annual ceremony. In both instances, the persons not wanting to attend the ceremonies are either relatives or close friends of the deceased and find it difficult to separate the pain of loss from the act of remembrance. In the words of the participant who purposely stays away from the memorials:

You can’t walk around with your head down all the time. I really have a hard time going to them. I’ve been to one, and it was the second one. I couldn’t go to the first one, I just couldn’t. And then the second one they had, I went to and I wish I hadn’t gone to that. I don’t think we should forget what happened, but I’m not sure in my opinion that it’s anything I need to commemorate each year, that loss.

These quotes highlight the contrast between how people make decisions about memorial attendance and how close connection to the deceased can influence that decision.

Role of the Memorial Structures

The Huntington, WV memorials are inscribed with text that detail the history of the tragedy, information about the deceased, and the connection between the tragedy and the local and university communities. Almost every participant talked about the memorials as a reminder of the tragedy, the people lost, and the commitment to never forget. If this is the overarching purpose of these memorials, they seem to serve that purpose well. Participants’ comments, which all lead back to this main purpose, highlighted a few specific functions served by the memorials. First, the memorials serve to educate visitors and passersby about the plane crash and its significance to the community. Even the participant who chooses to avoid the memorial ceremonies noted that the memorials help to educate people about the history of the crash: “It definitely is to bring exposure to what happened and where we were and where we are now. And I think it’s important to not forget, but some of us don’t need that to remember. I don’t.” Another participant spoke about how attending the ceremony in the past helped her to connect to the importance of the plane crash within the community:

Going to the memorial made it that much realer, and actually made it realer for me hearing the names and hearing what happened and having people recall what was happening at that time makes it far more realer and makes it feel like I was there. Even though they were not my memories, it’s a bit hard to explain, but even though they’re not my memories it makes it real, it makes it real. (Participant with Identities 1, 4, and 5)

Contrast is highlighted again by these quotes. Both participants confirm that the ceremony is educational and helps people to remember the deceased. However, proximity to the deceased influences the outcome of attendance. For the participant who can vividly recall the evening of the plane crash and the emotions of that moment, attendance at the memorial recalls those memories and makes the experience unpleasant. For the participant who learned about the crash later in life, upon affiliating with Marshall University, attending the memorial helps her to connect to the evening of the plane crash and to understand why it was a significant event. In addition to educating about the history of the crash, the memorials serve as a gathering place for family members of the crash victims, as well as for those in the Marshall and Huntington communities. Participants spoke about how often they visit the memorials:

My wife and daughter and I walk fairly regularly in the cemetery where the [cenotaph memorial is located] and if we’re gonna take a longer walk, we walk up by the memorial, you know? And if you’re on Marshall’s campus, you can’t help hardly but to walk by the fountain, I mean if you’re going anywhere on campus, it’s right in the center. It’s really something that you don’t…it’s just something that you don’t get away from in Huntington. I mean if you’re aware of it, almost anywhere you look, turn, or someone you talk to, then they’re somehow connected [to the plane crash and the deceased]. Whether they are a kid, or a grandkid, a nephew, or a friend. (Participant with identities 4, 5, 6, and 8)

I work here, and so obviously you eat lunch there [at the fountain]. And I have two grandsons…one is a student here now and I’ve sat at the fountain and explained to him what the fountain was. (Participant with Identities 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8)

These quotes are evidence that conversation about the crash, as well as visiting the memorials, is a regular part of life in Huntington for those who are long-time residents of the city. One student participant spoke about how the fountain has influenced his experience at the University:

It’s had a positive effect on me, I believe. Freshman year, being so far away from home [New Jersey], I was thinking about transferring back or transferring somewhere else. And I went to the Fountain Ceremony, I went with some friends and everything, and I just felt that community come together. (Participant with Identity 3)

In addition to being a source of connection for those who are long-time residents of Huntington, the memorials help Marshall students to develop a connection to the institution and the community.

Finally, the memorials were spoken about as a symbol of honor and prestige for the Marshall University community. Several participants mentioned the October 1970 plane crash that resulted in the death of 31 individuals associated with the Wichita State University football team. While Wichita State eventually discontinued the football program, Marshall University’s football program remains strongly intact today. People who feel closely connected to the Marshall plane crash hold this as a source of pride. The memorial structures and ceremony are a physical representation of this pride, and are respected with the local community. These quotes from one participant (with Identity 3) help to illuminate this theme in the interviews:

It talks for itself, the ceremony. It’s not the most advertised thing, because people just know in this area [Huntington]. November 14th is when the plane crash happened and they know that there’s going to be a ceremony at the fountain. Yeah you’ll get your Facebook updates and invites and word of mouth and everything but people know in this area that November 14th is the day to come to Marshall and experience the Fountain Ceremony….November 14th at Miami of Ohio [home institution of the researchers] I’m sure is different than November 14th here.

I’ve never seen it [the fountain] disrespected, ever. That’s coveted ground at Marshall. People don’t go in the water. People don’t throw coins in the water. People sit on the side and do homework, and that’s the only physical interaction I’ve ever seen with that fountain. It’s like when you go to the graveyard, you don’t mess with the stones.

Memorials as an Aid to Crisis Recovery

The memorials not only serve as a means to honor those who perished in the crash, but also to aid in the personal healing of individuals affected and the greater Marshall and Huntington communities. Throughout interviews, participants often spoke about Marshall University and Huntington, WV as communities that were inextricably intertwined by the plane crash. One participant (with Identities 1, 4, and 5), spoke specifically, at varying points in the interview, about how the plane crash joined these two communities together:

It made the community band together, as well as supporting and surrounding the students at Marshall University, because those students had some kind of connection to somebody on that plane crash, but also those community members had somebody that was connected on that plane.

It made the two entities [Marshall and Huntington] come together and form one entity. You have a community and institution that may have been separate at one time and had their own ideals and beliefs and things about one group or the other, but now they’ve come together because they’ve had to form this partnership

While the Marshall and Huntington communities united to support one another, other communities outside of West Virginia have shown their support as well:

A lot of us were very touched several years ago, we played East Carolina. That’s who we’ve played, that’s where we [the Marshall football team] were coming back from. And, and a lot of us found out that East Carolina still does some type of little tribute memorial or whatever you want to call it, uh, every year… a lot of them [people from East Carolina] took the time to go to the, you know, the memorial up at Spring Hill and down to the fountain. (Participant with Identities 4, 5, 6, and 8)

The first time that the City of Tuscaloosa recognized my brother and the three other guys that were killed in the plane crash was about three or four years ago. I was contacted by the Mayor’s Office of Tuscaloosa. They wanted me to participate in it. (Participant with Identities 7 and 8)

In addition to uniting communities, the memorials provide a space for individuals to personally reflect on the tragedy or gather together with others:

You just never forget. And you know, every day I walk past the student center or I’m walking on campus and I sit there, and you look at it ... and I’m not complacent about it. It’s not like it’s a backdrop or anything like that ... you look at it and you remember, you don’t forget. (Participant with Identity 1)

The number one thing you’ll hear from Marshall students is that we’re just one giant family and this is probably the reason why. The way I see it, everybody’s personal family they go through tragedy. Here at Marshall, we have that tragedy and because of that tragedy we have a common mindset. (Participant with Identity 3)

In this way, these memorials function as an integral part of the healing process, allowing people a designated space to visit and reflect on the tragedy and the lives of the deceased. One of the participants who was affiliated with the campus at the time of the crash, also spoke about how the tragedy of the crash itself served a similar purpose of uniting people across communities and helping people to heal:

Just immediately prior to the plane crash, there was an awful lot of racial unrest on this campus.... And it was about to explode. And I think [the plane crash] stopped all of that and brought everybody together. The Huntington community it brought together like no other, because we lost several really prominent people who were on that flight—doctors and lawyers and educators.... All the differences we had were minimized and everybody worked at making sure Marshall was okay. (Participant with Identities 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8) MU-15.11.13-MDS1-pt1, mins 9-10)

Thus, while the memorials currently help people to connect and heal, the memorials are an extension and continuation of the healing and connection spurred by the plane crash.

Another theme related to how the memorials aided crisis recovery is seen in the family members of the deceased. Study participants who are related to crash victims, all of whom traveled from afar to attend the 45th fountain ceremony, spoke of how the memorials and ceremony also help families of the deceased connect with one another and create their own systems of support:

We’ve [the families of the deceased] all become family over the years. It’s just become a huge family expanding over the years. (Participant with Identities 6, 7, and 8)

There were so many young kids that lost their parents, both parents, and I think that they stayed in the community, a lot of them did ... They helped each other in the process, in the healing process. (Participant with Identities 7 and 8)

It’s always a good time to go back. Even this time, there were people there that has never attended a memorial since the crash, and I met some of those people this time. You know, who just couldn’t, you know for whatever reason, build up the courage to go back for a service. So, you know I was glad to be able to meet them. (Participant with Identities 7 and 8)

The connections between these people was apparent as they embraced each other and engaged in intimate conversation before and after the ceremony, intent on maintaining the connections that their deceased family members shared.

Despite such a tragic event occurring to the Marshall and Huntington communities, members of these communities persevered and have developed a narrative around this perseverance. During interviews, there was a heavy emphasis on building and passing on a legacy:

You definitely have to remember that we’re, you know, standing on the backs of those who died ... you have to remember how all of this started. We’re here making you [those who perished in the crash] proud. (Participant with Identities 4 6, 7, and 8)

We pulled together a football team for the next year. Most of the people didn’t understand all that was going on behind the scenes, but just to see how we couldn’t let it die, how you have to go on for the people who are here, the people who gave their lives.... We owe it to the football players and the coaches and the people who died on the plane to keep that memory alive. Because it is [a memory] not only one of sadness but a rising from the ashes, that we are not going to roll over and die, that we are a community that is viable. We can move on, we can still honor people from the past, and you honor them by going on and doing something positive for the city. (Participant with Identities 1, 4, 5 and 6)

These people that lost their lives, they are the ones that reshaped Marshall’s foundation and made it into what it is today, and ... grew it from a school to a family. (Participant with Identity 3, 5, and 6)

These examples of how people speak of the deceased as heroes whose lives provided a foundation for institutional revitalization and growth are the epitome of how and why this plane crash is remembered; the collective memory provides the foundation for institutional identity.

Conclusions and Implications

These findings offer insights into how people interact with the memorials that exist. Ashworth and Hartmann (200520) write about tourism attraction to sites where human atrocities have occurred. The three main reasons they identify regarding why tourists are attracted to these sites all have to do with the sense of familiarity that is inherent in human atrocity. These three reasons are (1) the curiosity of wanting to view spaces that are unusual or unique, similar to any type of tourism; (2) the empathy some may feel either toward the victims or perpetrators of an atrocity; and (3) the attraction to horror, not unlike the desire to feel a flurry of emotions in a movie theater or haunted house. Some of these same elements may help to explain how and why people interact with sites of campus/community tragedy. For our study participants, the first two reasons are resonant: visitors are drawn to the Marshall plane crash memorials largely out of empathy and connection to the victims, but also often due to either the curiosity of seeing the memorial sites or the experience of being engulfed in the crowd that gathers each November 14th.

It is likely that the importance placed on the three memorial structures has been largely sustained by the continuation of an annual memorial ceremony for 45 years. That is, if the ceremony did not occur each year, spurring and encouraging the act of remembrance, it is possible that institutional memory surrounding the plane crash would not be as strong and the memorial structures would not be held with the same amount of reverence that they are currently afforded. Marshall University and Huntington, WV are effective at educating newcomers and visitors alike on the history of the plane crash and indoctrinating new community members into the culture of remembrance that surrounds that tragedy. The annual events surrounding November 14th are a major factor in the success of this indoctrination, and have played a large role in helping this community to bond, heal, remember, and continue to “thunder forward.”

This research helps to answer questions regarding the impact of tragedy on a community and how communities move through the healing process after a tragedy. The results suggest that memory of a community tragedy can be a powerful force in the healing process and in helping people to move forward. The one important caveat is that individuals closely related to victims of tragedy, through family or friendship ties, may have their healing process stunted or reverted by consistent acts of remembering. These findings help to inform leadership responses to community tragedies and provide a foundation for further research around the topics of crisis management, emergency preparedness, and community healing.

References

-

City of Huntington. (2015). Community profile. Retrieved from: http://www.cityofhuntington.com/visitors/community-profile ↩

-

Woodrum, W. (2015, June 13). Marshall makes pilgrimage to Spring Hill Cemetery. Herd Insider. Retrieved from: http://herdinsider.com ↩

-

Zdziarski, E. L., II, Rollo, J. M., & Dunkel, N. W. (Eds.). (2007). Campus crisis management: A comprehensive guide to planning, prevention, response, and recovery. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. ↩

-

Bowker, G. C. (1997). Lest we remember: Organizational forgetting and the production of knowledge. Accounting, Management, & Information Technology, 7(3), 113-138. ↩

-

Easterby-Smith, M. & Lyles, M. A. (2011). In praise of organizational forgetting. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(3), 311-316. ↩

-

Fernandez , V., & Sune, A. (2009). Organizational forgetting and its causes: An empirical research. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 22(6), 620-634. ↩

-

Kleiner, M. M., Nickelsburg, J., & Pilarski, A. M. (2012). Organizational and individual learning and forgetting. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 65(1), 68-81. ↩

-

Martin de Holan, P. (2011a). Agency in voluntary organizational forgetting. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(3), 317-322. ↩

-

Martin de Holan, P. (2011b). Organizational forgetting, unlearning, and memory systems. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(3), 302-304 ↩

-

Martin de Holan, P., Phillips, N., & Lawrence, T. B. (Winter 2004). Managing organizational forgetting. MIT Sloan Management Review, 45-51. ↩

-

Martin de Holan, P. & Phillips, N. (2004a) Organizational forgetting as strategy. Strategic Organization, 2(4), 423-433. ↩

-

Martin de Holan, P. & Phillips, N. (2004b). Remembrance of things past? The dynamics of organizational forgetting. Management Science, 50(11), 1603-1613. ↩

-

Wong, P. S. P., Cheung, S. O., Yiu, R. L. Y., & Hardie, M. (2012). The unlearning dimension of organizational learning in construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 30, 94-104. ↩

-

Reid, J. K., & Reid, C. L. (2001). A cross marks the spot: A study of roadside death memorials in Texas and Oklahoma. Death Studies, 25(4), 341-356. ↩ ↩

-

Santino, J. (Ed.), (2006). Spontaneous shrines and the public memorialization of death. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ↩

-

Sturken, M. (2007). Tourists of history: Memory, kitsch, and consumerism from Oklahoma City to ground zero. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Weick, K. E. (1988). Enacted sensemaking in crisis situations. Journal of Management Studies, 25(4), 305-317. ↩

-

Yin, R.K. (2009). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage. ↩ ↩

-

Stake, R. (2010). Qualitative Research: Studying How Things Work. New York: The Guilford Press. ↩

-

Saldaña, J. (2009). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Los Angeles: Sage. ↩

-

Ashworth, G. & Hartmann, R. (2005). Horror and human tragedy revisited: The management of sites of atrocities for tourism. New York, NY: Cognizant Communication. ↩

Shaw, M. & Cherry, G. (2015). Thundering Forward: Remembering Community Tragedy in Huntington, West Virginia (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 260). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/thundering-forward-remembering-community-tragedy-in-huntington-west-virginia