The Effect of Experiencing Disaster Losses on Risk Perceptions and Preparedness Behaviors

Publication Date: 2023

Executive Summary

Overview

Some studies suggest that individuals who have experienced material losses or personal harm during disasters may be more likely to take disaster preparedness actions prior to the next event. To date, however, results are inconclusive and no study has fully explored the direct and indirect relationship between individuals’ experience of personal loss during past disasters and their subsequent preparedness actions for future extreme weather events. This study explored how individuals who experienced personal losses during Tropical Storm Eta in November 2020 were affected. More specifically, our study investigated whether personal losses during the severe flooding event influenced individuals’ risk perceptions regarding flooding, personal relevance of flooding, hurricane personal self-efficacy, and preparedness actions. We distributed an online survey (N=312) to residents of Alexander, Mecklenburg, and Wake counties in North Carolina within one year of Tropical Storm Eta, whose heavy rains moved through the state November 12-13, 2020, producing severe flooding that caused injuries, deaths, and property damage throughout the three counties. By exploring the relationship between experiencing personal losses during a disaster and subsequent preparedness behaviors, this study aims to shed light on how public risk communication messages could leverage these experiences to encourage people to prepare for future events.

Research Questions

Our overarching research questions were:

- To what extent does an individual’s experience of material loss or personal harm during an extreme weather event influence their risk perception (measured as “perceived susceptibility” and “perceived severity”) of that type of event?

- If experiencing personal losses during disasters is associated with increased risk perception, to what extent does that heightened risk perception then influence people to prepare for future extreme weather events?

- Does experiencing material losses or personal harm during a disaster directly influence individuals to take preparedness actions? What is the role of perceived personal relevance and self-efficacy in the relationship between experience with an extreme weather event and disaster preparedness actions people tend to take to prepare for such an event, and between risk perception and disaster preparedness actions?

Research Design

The study used Qualtrics to distribute an online survey to respondents in the three counties mentioned above. The questionnaire asked participants about the material losses or other personal harms they experienced during Tropical Storm Eta. We developed a scale to measure personal losses during disasters that used six items, including questions about significant physical injuries, material loss (e.g., home, source of employment), loss of family members or friends, and loss of utilities. Participants were also asked to describe the preparedness actions they tend to take during hurricane season; how they perceive the risks of flooding, tropical storms, and hurricanes in the region; how they rated the personal relevance of these risks; and about their hurricane personal self-efficacy. We used structural equation modelling to assess the direct relationship between experience and disaster preparedness actions, and the indirect relationship between experience and preparedness actions through risk perception, personal relevance, and self-efficacy.

Findings

Our preliminary analysis of the survey data showed that experiencing material loss during Tropical Storm Eta had a very strong direct influence on individuals’ preparedness behaviors. Material loss also had strong indirect effects on preparedness behavior by increasing how individuals perceived their susceptibility to flooding and their perceptions of the personal relevance of flooding. Material loss, however, did not affect how individuals perceived the severity of flooding nor their perceptions of hurricane personal self-efficacy.

Implications for Practice and Policy

This study shows that individuals who experienced material loss during a previous extreme weather event were much more likely to prepare for future extreme weather events. The relationship between previous material loss and preparedness may be even stronger than the relationship between preparedness and self-efficacy or preparedness and perceived susceptibility This finding suggests that public risk communication could leverage negative experiences with past events to motivate individuals to take disaster preparedness actions. Such messages could be particularly useful during the post-crisis phase of an extreme weather event, especially in the weeks before the next hurricane season begins. Findings also suggest that risk messaging should focus on how susceptible individuals are to the storm, rather than on how severe the storm may be.

Introduction

On November 9, 2020, the National Weather Service forecasted that Tropical Storm Eta would dump between 3-4 inches of rainfall across North Carolina (Johnson, 20201). The storm made landfall two days later, and between November 11 and 13, 2020, caused severe flooding throughout the state. Post-storm reports would eventually show that some areas around Charlotte (Mecklenburg County) and Raleigh (Wake Country) received more than twice what was forecasted (Jasper, 20202; Kepley-Stewart, 20203). At least 11 people in North Carolina lost their lives during the event. The most severe devastation took place in Alexander County where six people were killed and 31 people had to be rescued from flooding (Guzman, 20204; Jasper, 2020). Wake County was also hit hard. One child drowned near a swollen creek and numerous people were rescued from the floodwaters (Kepley-Stewart, 2020).

Such devasting consequences of extreme weather provide a stark reminder of the need for continued research into the types of risk communication that might motivate the public to take disaster preparedness steps. For example, weather alerts such as storm and flood warnings are vital, but their effectiveness depends on the extent to which individuals are capable of following their advice (Kellens et al. 20135; Kuller et al. 20226; Lindell et al., 20197; Potter et al., 20188; Shrestha et al., 20219). Disaster preparedness improves the ability to heed warnings or take other protective actions and has been shown to save lives and increase resilience (Tall et al., 201210).

This study aimed to investigate whether experiencing material losses or other personal harms during a disaster event—such as suffering significant physical injuries, losing loved ones, or going without electricity, food, or water in the days after the event—would influence an individual’s subsequent risk perceptions and disaster preparedness behaviors. This research topic has not received adequate attention. Understanding this relationship could be useful for crafting public awareness messages that leverage individuals’ negative experiences during past disasters in ways that encourage them to prepare for future extreme weather events. There are several ways in which the effectiveness of such messages could be studied. This study proposes, however, that it is necessary to first establish and understand the relationship between past disaster experiences and subsequent disaster preparedness actions. We surveyed individuals about their material losses and other personal harm during Tropical Storm Eta and assessed how these experiences directly influenced their subsequent disaster preparedness actions. We also examined how these experiences indirectly affected their preparedness actions through changes in their risk perception, personal relevance, and self-efficacy.

Literature Review

Kellens et al.’s (2013) review of 57 peer-reviewed articles on flood risk perception found that individuals who have experience with floods tend to have higher perceptions of risk and efficacy beliefs and are more likely to engage in preparedness actions. Kuller et al.’s (2021) meta-analysis of 128 peer-reviewed articles also concluded that personal experience with floods has a positive influence on risk perception, and, further, that risk perception persists if memory of the experience is triggered, for example through stories and commemorative signs or other public displays memorializing the tragedy.

Other studies, however, have been less conclusive. Weber et al. (201811), for example, found that individuals with past disaster experience—including hurricanes and floods—were not directly influenced by that experience to engage in disaster preparedness behaviors. Moreover, the authors showed that even though past disaster experience increased individuals' perceived susceptibility, their heightened risk perception did not lead them to take disaster preparedness actions. On the other hand, the authors found that experience with disaster impacts—including individuals who suffered some type of personal harm or material loss during the disaster—did significantly influence preparedness behaviors both directly and indirectly through self-efficacy. It is important to recognize the difference between having experienced a disaster without suffering personal harm or material losses and being impacted in these ways by the disaster. Kellens et al. (2013) do this by distinguishing between physical exposure to flood hazards determined by proximity to the hazard source (e.g., river, ocean) and firsthand experiences with previous flood events such as being personally affected by floods or suffering flood damage.

Bronfman et al. (202012) found that individuals who had experienced physical and material impacts during the 2014 earthquake in Iquique, Chile had higher levels of risk perception and were more likely to be prepared for future earthquakes. Other studies, however, have shown that even though individuals with prior disaster experiences have higher risk perceptions, they do not necessarily act on these perceptions and take disaster preparedness steps. For example, Johnston et al. (199913) described how residents in New Zealand who experienced an earthquake became more knowledgeable about earthquakes and more aware of the risk earthquakes posed to them, however, their increased risk perception did not translate into preparedness activities for a similar future event. Instead, the authors found “a reduction in preparatory activities" (p. 125). Johnson et al. (198914) attributed this decrease in disaster preparedness to normalization bias, which was described by Mileti and O'Brien (199315) as a type of rationalization in which people assume that because they experience a negative event without adverse effects, then similar subsequent events will also not harm them personally.

In addition to the direct ways in which experiencing a disaster influences individuals’ preparedness behaviors, research also suggests there are indirect effects through risk perception. Risk perception is often measured as “perceived susceptibility” or “perceived severity.” There are gaps, however, in the risk communication literature regarding the role of personal relevance in the relationship between disaster experience and preparedness actions. In Petty and Cacioppo’s (198616) Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), personal relevance (sometimes called issue involvement) is defined as the extent to which an issue is of personal importance (see also Petty & Cacioppo, 199017, p. 367). In the context of extreme weather, the attitudinal issue can be seen broadly as the threat of being impacted by the weather event.

In the broader field of communication, personal relevance has been explored in studies about message processing and design (Johnson & Eagly, 1989; Petty & Cacioppo, 1990; Zaichkowsky, 198518, 198619). According to Miller and Averbeck (201320), the type of personal relevance (or involvement, as the authors refer to it) that has received the most scholarly attention is “outcome-relevant involvement,” which is defined as people's “concern about their ability to attain desirable outcomes” (Johnson & Eagly, 1990, p. 375). In this framework, personal relevance measures people’s concern with the outcome of an extreme weather event or the outcome of disaster preparedness actions to mitigate the impact of the event. The ways people perceive the relevance of these outcomes to their own lives has implications for risk communication and related responses.

Some researchers have theorized that increasing the personal relevance of a risk could lead individuals to take mitigating actions (see Kahlor et al., 200621; Weber, 200622). For example, Guion et al. (200723) suggested that perceived benefits of disaster preparedness actions can be increased through messaging that increases the personal relevance of those actions. In assessing factors that contribute to flood risk preparedness, however, Maidl and Buchecker (201524) found that although knowledge about flooding predicted personal relevance, it did not predict risk perception. According to Petty and Cacioppo’s (1986) Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), higher levels of personal relevance motivate message processing through the central route of cognition, allowing for greater elaboration on message arguments, which then leads to longer-lasting attitude and behavior change. Alternatively, lower levels of personal relevance motivate message processing through the heuristic route, allowing for greater elaboration on cues (e.g., attractiveness of message source) that are irrelevant to message arguments. Persuasion through the heuristic route is not as long-lasting as through the central route of message processing. It therefore stands to reason that messages that leverage the personal relevance of severe weather could result in more central route processing and therefore longer lasting behavior change regarding disaster preparedness. Personal relevance therefore deserves more attention in risk communication research.

Although our study does not test messages, it helps to address gaps in the literature by providing more insight into the role personal relevance plays in the relationship between experience with loss caused by an extreme weather event and disaster preparedness actions for a future similar event, and further, how this relationship is influenced by risk perception.

Research Design

Research Questions

Our overarching research questions were:

- To what extent does an individual’s experience of material loss or personal harm during an extreme weather event influence their risk perception (measured as “perceived susceptibility” and “perceived severity”) of that type of event?

- If experiencing personal losses during disasters is associated with increased risk perception, to what extent does that heightened risk perception then influence people to prepare for future extreme weather events?

- Does experiencing material losses or personal harm during a disaster directly influence individuals to take preparedness actions? What is the role of perceived personal relevance and self-efficacy in the relationship between experience with an extreme weather event and disaster preparedness actions people tend to take to prepare for such an event, and between risk perception and disaster preparedness actions?

Hypotheses

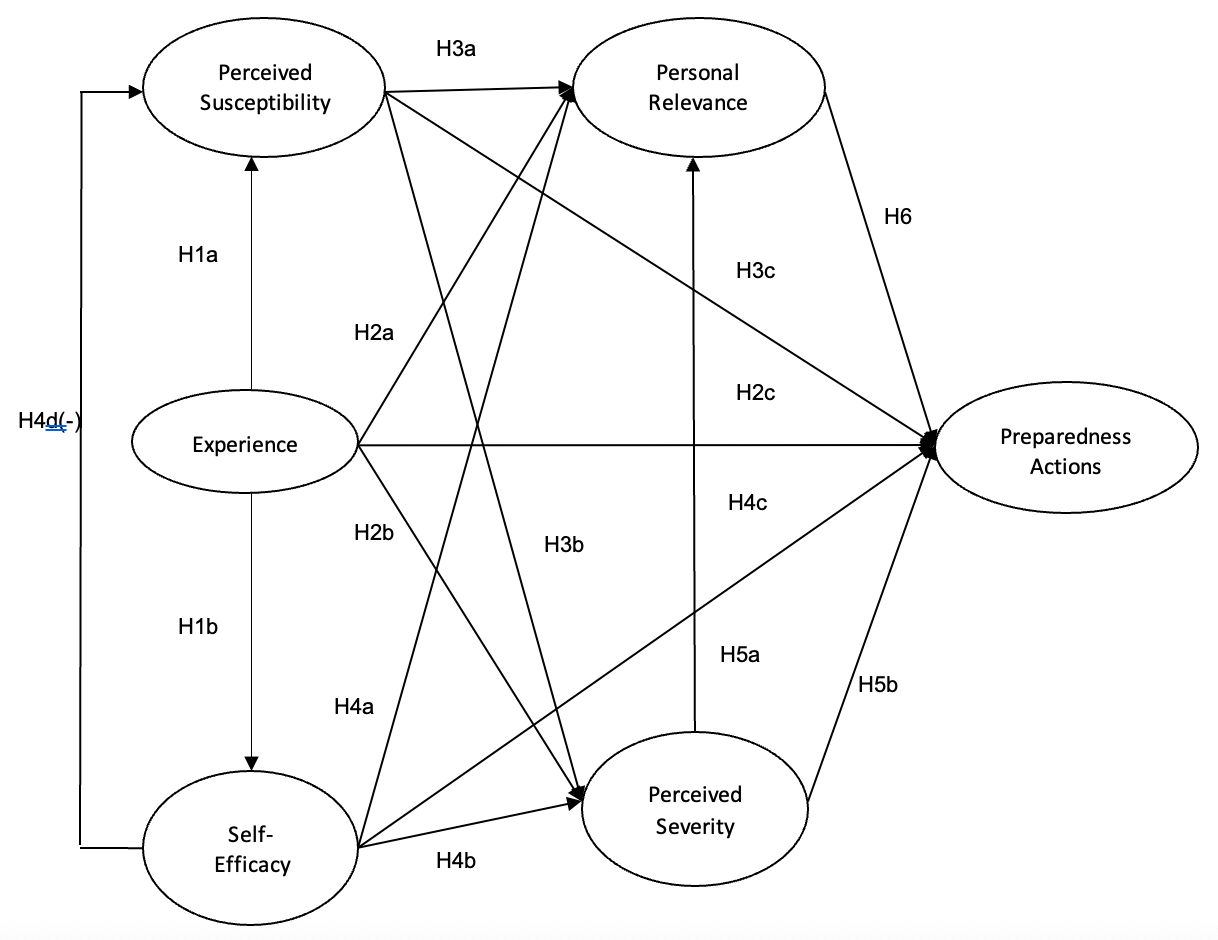

Using past studies and other relevant literature as our guide, we tested the conceptual model diagrammed in Figure 1. The list below explains each hypothesis in the model:

- Hypothesis 1 (H1): Experience will have a positive influence on (a) perceived susceptibility and (b) hurricane personal self-efficacy.

- Hypothesis 2 (H2): Experience will be positively associated with (a) personal relevance, (b) perceived severity, and will also have a (c) direct positive influence on preparedness actions.

- Hypothesis 3 (H3): Perceived susceptibility will be positively associated with (a) personal relevance and (b) perceived severity, and will have a (c) direct positive influence on preparedness actions.

- Hypothesis 4 (H4): Hurricane personal self-efficacy will be positively associated with (a) personal relevance, (b) perceived severity, and will have a (c) direct positive influence on preparedness actions, but a negative influence on (d) perceived susceptibility.

- Hypothesis 5 (H5): Perceived severity will be positively associated with (a) personal relevance and (b) preparedness actions.

- Hypothesis 6 (H6): Personal relevance will be positively associated with preparedness actions.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Model

Study Site Description and Context

We conducted an online survey of current residents of Alexander, Mecklenburg, and Wake counties in North Carolina between August 18, 2021, and October 5, 2021, which was roughly nine to eleven months after Tropical Storm Eta. Participants had to be over 18 years and currently residing in the counties mentioned.

Data, Methods, and Procedures

Online survey data were collected via Qualtrics, which recruited and compensated participants on behalf of the study team. Qualtrics charged on average $5 to $6 per respondent. According to Qualtrics, panel participants were recruited from various sources and provided with a hyperlink to the survey. Before beginning the survey, prospective participants were asked to read an information page about the study and provide consent electronically.

Qualtrics provided the research team with data from 312 completed surveys. These surveys were collected from respondents who met the inclusion criteria (18 years or older and living in one of three study counties) and who correctly answered the quality control questions which required participants to choose specific answers to questions not directly related to the research questions. The final number of surveys used in the data analysis represents 47% of people who started the survey. The results in this report are based solely on data from the final data set of 312 respondents.

Sampling and Participants

About half (51%) of the participants were from Wake County with another 43% from Mecklenburg County. The vast majority of the participants were white (82%) with the next largest group being Black or African American (13%). About two-thirds of the participants were under age 65. Over 60% of respondents had at least a two-year college degree. The sample had an overrepresentation of females (77.6%), which we address in the section on limitations. See Table A1 for details on demographics.

Measures

The measurement scales used in the survey are briefly described below. Seven-point Likert scales (0 – 6) with explicit descriptions for the ends of the scales (e.g., low agreement—high agreement) were used to measure perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and personal relevance. Five-point Likert scales (strongly agree to strongly disagree) was used to measure hurricane personal self-efficacy and experience with loss during Tropical Storm Eta. We repeated all items for three types of risks: flood, tropical storm, hurricane. For this report, we only analyzed the flood data because that specific extreme weather event was the impetus for this study. (In the appendix, see Table A2 for scale reliabilities, Table A3 for means and standard deviations of the scales, and Table A4 for inter-scale correlations.)

Preparedness Actions

To develop our measures for disaster preparedness actions, we reviewed readync.gov, a North Carolina state government website for informing the public about emergency preparedness. Our review resulted in us creating two “check all that apply” questions with lists of disaster preparedness actions. We labeled the first question as level 1 preparedness actions (and used the shorthand “L1Preps”). This checklist included less demanding actions such as storing clean drinking water or keeping a first aid box ready. The other question had a list of more effortful actions such as participating in mock drills for flood evacuation and making one’s home flood resistant; we refer to these as level 2 preparedness actions (“L2Preps”). We measured each set of actions by summing the number of “check all that apply” boxes checked. (See Tables A5-A8 in the appendix for the list of actions and percentage of participants checking each box.)

Perceived Susceptibility

Perceived susceptibility was measured using the susceptibility subscale of the Risk Behavior Diagnostic Scale, which is often referred to as the “RBD” (Witte, McKeon, Cameron, & Berkowitz, 199525), and one additional item added by the research team. The four items were: (1) it is likely that I will be affected by flooding, (2) I am at risk for being affected by flooding, and (3) It is possible that I will be affected by flooding. The additional item was: (4) The extent to which I will be affected by flooding is great.

Perceived Severity

Perceived severity was measured by adapting the severity subscale of the RBD (Witte et al., 1995) and one additional item added by the research team. The four items included: (1) I believe that flooding is severe, (2) I believe that flooding has serious negative consequences (the term “negative consequences” was added to improve specificity), and (3) I believe that flooding is extremely harmful. The additional item was: (4) I believe that the effects of flooding are intense. The item ”I believe that flooding is severe” was dropped after a confirmatory factor analysis showed a very low factor loading.

Personal Relevance

Personal relevance was measured on a scale adapted from Zaichkowsky’s (1994) Personal Involvement Inventory (PII) in which involvement is operationalized as perceived personal relevance. The original bipolar adjective items were put into complete sentences. For example, “unimportant‒important’” read, “How important is the threat of flooding in your life?” The other items measured perceptions of concern, relevance, triviality, and the extent to which the threat was of interest. Although eight items were used in the questionnaire, only five items were used for the model fit because three of the items (whether flooding has meaning to the individual, whether flooding matters to the individual, and whether flooding is significant to the individual) have very low factor loadings.

Hurricane Personal Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured using eight items from a Hurricane Personal Self-Efficacy Scale adapted from Stewart (201526). Example items are “I have a safety plan for how to deal with a hurricane” and “I can evacuate when necessary ahead of a hurricane.”

Experience With Material Loss or Other Personal Harms During Disaster

Experience with material loss or other personal harms during disaster was measured using six items adapted from a physical experience subscale in Bronfman et al. (2020) and designed to specifically capture losses or harms that occurred during Tropical Storm Eta. The six items measured on a five-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) were:

- I suffered significant physical injuries during Tropical Storm Eta or during the flooding related to the storm.

- I was affected by significant material loss (home, source of employment, car, etc.) during Tropical Storm Eta or during the flooding related to the storm.

- I suffered the loss of a family member, friend, colleague, etc. during Tropical Storm Eta or during the flooding related to the storm.

- I lost access to communication (e.g., unable to use a telephone) to contact my family and friends during Tropical Storm Eta.

- I ran out of water or food during Tropical Storm Eta.

- I was without electricity for more than two days during Tropical Storm Eta.

Ethical Considerations

This study (IRB00024151) was approved by the Wake Forest University Institutional Review Board on Mach 15, 2021.

Data Analysis

The hypotheses were tested using a structural equation model, run with IBM SPSS Amos 28 using maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was evaluated using the following criteria: (a) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of .08 or lower, (b) a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of .06 or lower, (c) a comparative fit index (CFI) of .95 or higher (Hu & Bentler, 199927), and (d) a chi-square goodness-of-fit statistic divided by the degrees of freedom (χ2/df) of less than 3 (Kenny, 202028).

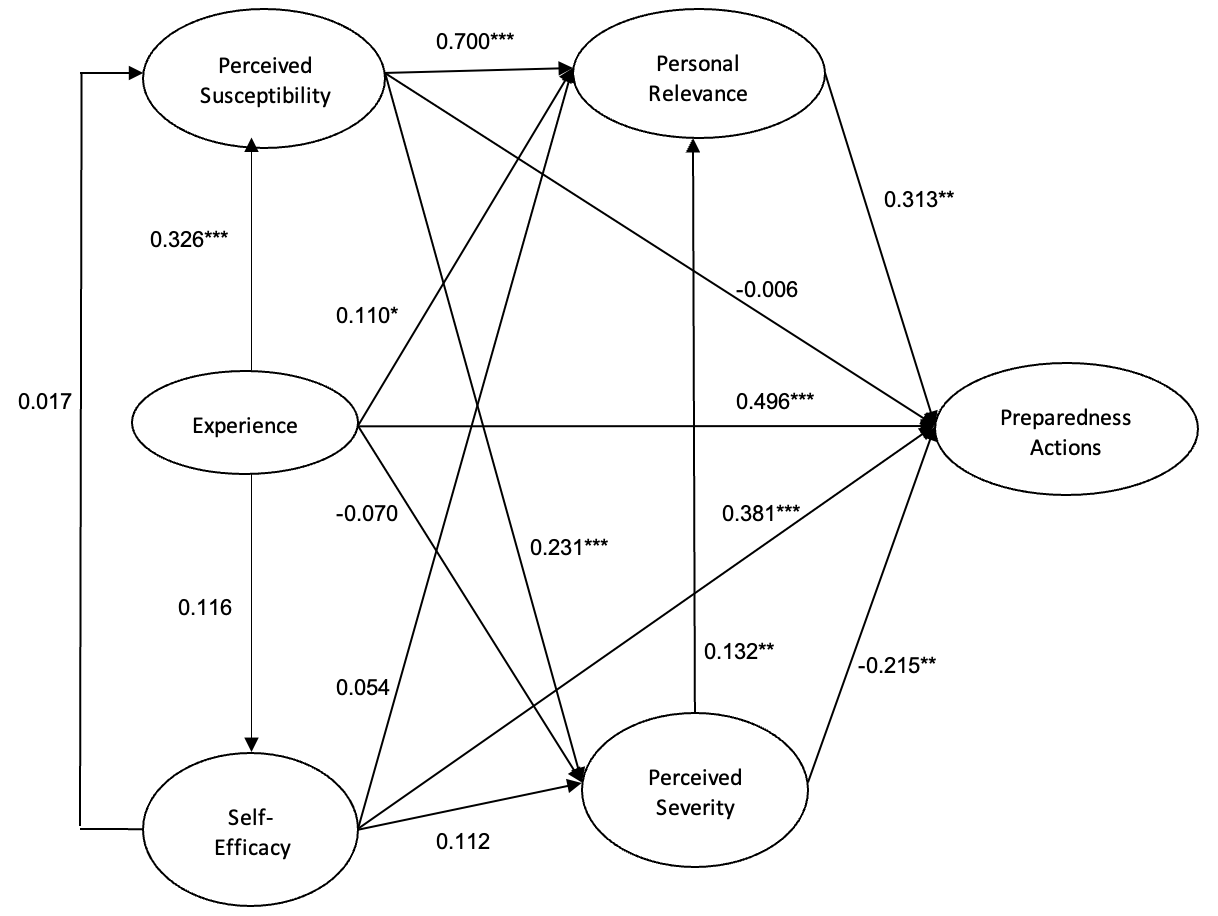

Based on these criteria, the model fit between the hypothesized model and the observed data was somewhat acceptable for all three hazards–flood, tropical storm, and hurricane. Although the CFI was lower than desired (less than .95), it is above .90, which is considered acceptable (see Lai & Green, 201629). The fitted model below shows the model fit (N = 312), χ2 (df = 335) = 806.026, p < .001 (χ2/df = 2.4); RMSEA=0.067 (90% confidence interval: 0.061-0.073); SRMR = .062; CFI = .909.

Results

We sought to investigate the extent to which a person’s experience of material loss and other personal harms during a disaster influenced their risk perception (perceived susceptibility and perceived severity), and the extent to which that risk perception then influenced their preparedness actions. We also sought to study the extent to which material loss or personal harm directly influenced disaster preparedness actions. Our results showed that experiencing these personal losses or harms had a strong positive influence on an individual’s perceived susceptibility to floods, but it did not influence their perceptions of flood severity. In turn, the increase in perceived susceptibility did not influence individuals to take disaster preparedness actions. Furthermore, having higher levels of perceived severity had a significant negative influence on preparedness actions. On the other hand, experiencing material or personal loss during a disaster had a very strong direct positive influence on preparedness actions.

We also investigated the role of personal relevance and efficacy in the relationship between experiencing material or personal loss and preparedness actions. Our results showed that, on the one hand, experiencing such disaster harms or losses personally had a significant but relatively weak direct positive influence on personal relevance. On the other hand, experiencing harms had a significant indirect influence on personal relevance through perceived susceptibility. This indirect relationship resulted in personal relevance having a strong positive influence on preparedness actions. Experiencing disaster losses or harm did not have a significant direct influence on hurricane perceived self-efficacy. However, having higher levels of perceived self-efficacy had a strong direct influence on disaster preparedness actions.

The outcomes of the hypotheses are shown in Figure 2, which illustrates the standardized regression weights of the fitted model. (Table A9 in the Appendix shows both unstandardized and standardized regression weights for each path.) Hypotheses 1-5 received partial support and Hypothesis 6 was fully supported. Hypothesis 1 was partially supported in that experiencing disaster losses or harm did have a positive influence on perceived susceptibility (H1a), but the prediction that experience would also have a positive influence on hurricane personal self-efficacy was not supported (H1b).

Figure 2. Fitted Model

*p<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001.

Hypothesis 2 was also partially supported in that experiencing disaster loss or harm was positively associated with personal relevance but the strength of the relationship was fairly week (H2a). Moreover, the prediction that these experiences would be positively associated with perceived severity was not supported (H2b). Lastly, our results showed that disaster loss or harm had a direct and positive influence on preparedness actions (H2c).

Hypothesis 3 was partially supported by our results. Perceived susceptibility to flooding was associated with higher levels of personal relevance (H3a) and perceived severity (H3b). However, perceived susceptibility did not have a direct positive influence on preparedness actions (H3c).

Hypothesis 4 was only partially supported by the results. Hurricane personal self-efficacy was not positively associated with personal relevance (H4a) or perceived severity (H4b). However, the prediction that self-efficacy would be positively associated with preparedness actions was supported (H4c). On the other hand, contrary to our hypothesis, self-efficacy was not negatively associated with perceived susceptibility (H4d).

Hypothesis 5 was also partially supported by the results. Perceived severity was positively associated with personal relevance (H5a). However, it was not positively associated with preparedness actions (H5b). Instead, perceived severity had a significant negative influence on preparedness actions.

Hypothesis 6 was the only prediction with one path and it was fully supported. Personal relevance was positively associated with preparedness actions.

Conclusions

Implications for Practice and Policy

This study showed that experiencing material loss or other personal harm during an extreme weather event can have a strong direct positive influence on individuals’ preparedness behavior for future disasters. This finding can be leveraged through risk communication messages between the post-crisis phase of an event and the pre-crisis phase of a subsequent event. The finding can also be used during periods of high uncertainty, for example, during the tropical storm season when general predictions are made but more specific predictions may not be possible until storms are impending. In the few days or hours of a warning, reminding residents of the negative effects of past storms (e.g., personal and community loss due to flooding) while highlighting self-efficacy to engage in self-protective behaviors might serve to augment the effectiveness of the warning to motivate such behaviors. The results also showed that perceived susceptibility on its own may not directly motivate preparedness behaviors unless they are deemed personally relevant. Risk communicators can apply these findings by working with communities to help them process stories of loss by using those stories to save future lives and valued possessions.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The overrepresentation of females in the sample (77.6%) is a limitation of the study, going well beyond the typical 60-40 female-male split that the panel service told us to expect. The interpretation of the results should therefore be viewed within the context of this limitation. The results are not generalizable to populations and contexts in which gender distribution is approximately equal or overrepresentative of one gender. Nonetheless, because many studies show that females tend to have higher perceptions of risk than males, including greater vulnerability, while at the same time having less access to mitigating resources (Chauvin, 201830), this study can provide useful knowledge to the broader study of disaster risk perception and behavior. The results we found might be particularly useful for risk communicators who share disaster information with groups that are disproportionately female, such as caregivers. For example, it can lend insight into how disaster experiences of women might be leveraged to promote preparedness for extreme weather in households headed by women.

The study did not test messages so a next step would be to conduct lab and field experiments that assess the extent to which public awareness messages that incorporate past experiences of material loss or personal harm during disasters affect individual risk perception and preparedness behaviors. Extreme care should be taken, however, to tap into these painful stories wisely. More work should also be done to test the role of personal relevance in perceptions of extreme weather events and preparedness behaviors. We also recommend investigating how stories of others experiencing personal loss or harm during disasters affect the risk perceptions, personal relevance, and preparedness actions of individuals who have not suffered these same losses. Such studies should be conducted in partnership with people from different socio-economic backgrounds.

References

-

Johnson, K. (2020, November 9). Tropical Storm Eta: Here's What Storm Will Mean For NC. https://www.msn.com/en-us/weather/topstories/tropical-storm-eta-heres-what-storm-will-mean-for-nc/ar-BB1aQ9KK. ↩

-

Jasper, S. (2020, November 13). Death toll climbs after flash flooding in North Carolina; Some rivers are still rising. https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/weather-news/article247165406.html. ↩

-

Kepley-Stewart, K. (2020, November 13). Multiple deaths reported in NC after flooding; statewide State of Emergency in effect. https://wlos.com/news/local/multiple-deaths-reported-in-nc-after-flooding-statewide-state-of-emergency-in-effect. ↩

-

Guzman, G. (2020, November 13). Eta flash floods turn deadly in North Carolina. At least seven are dead and three are missing. Retrieved from https://thehill.com/changing-america/resilience/natural-disasters/525850-eta-flash-floods-turn-deadly-in-north-carolina. ↩

-

Kellens, W., Terpstra, T., & De Maeyer, P. (2013). Perception and communication of flood risks: A systematic review of empirical research. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 33(1), 24-49. ↩

-

Kuller, M., Schoenholzer, K., & Lienert, J. (2021). Creating effective flood warnings: A framework from a critical review. Journal of Hydrology, 602, 126708. ↩

-

Lindell, M. K., Arlikatti, S., & Huang, S. K. (2019). Immediate behavioral response to the June 17, 2013 flash floods in Uttarakhand, North India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 34, 129-146. ↩

-

Potter, S. H., Kreft, P. V., Milojev, P., Noble, C., Montz, B., Dhellemmes, A., ... & Gauden-Ing, S. (2018). The influence of impact-based severe weather warnings on risk perceptions and intended protective actions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 30, 34-43. ↩

-

Shrestha, M. S., Gurung, M. B., Khadgi, V. R., Wagle, N., Banarjee, S., Sherchan, U., ... & Mishra, A. (2021). The last mile: Flood risk communication for better preparedness in Nepal. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 56, 102118. ↩

-

Tall, A., Mason, S. J., Van Aalst, M., Suarez, P., Ait-Chellouche, Y., Diallo, A. A., & Braman, L. (2012). Using seasonal climate forecasts to guide disaster management: the Red Cross experience during the 2008 West Africa floods. International Journal of Geophysics, 2012. ↩

-

Weber, M. C., Schulenberg, S. E., & Lair, E. C. (2018). University employees' preparedness for natural hazards and incidents of mass violence: An application of the extended parallel process model. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, 1082-1091. ↩

-

Bronfman, N. C., Cisternas, P. C., Repetto, P. B., Castañeda, J. V., & Guic, E. (2020). Understanding the Relationship Between Direct Experience and Risk Perception of Natural Hazards. Risk Analysis, 40(10), 2057. ↩

-

Johnston, D. M., Lai, M. S., Houghton, B. F., & Paton, D. (1999). Volcanic hazard perceptions: comparative shifts in knowledge and risk. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. ↩

-

Johnson, B. T., & Eagly, A. H. (1989). Effects of involvement on persuasion: A meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 106(2), 290. ↩

-

Mileti, D. S., & O’Brien, P. (1993). Public response to aftershock warnings. US geological survey professional paper, 1553, 31-42. ↩

-

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag. ↩

-

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1990). Involvement and persuasion: Tradition versus integration. ↩

-

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 341-352. ↩

-

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1986). Conceptualizing involvement. Journal of Advertising, 15(2), 4-34. ↩

-

Miller, C. H., & Averbeck, J. M. (2013). Hedonic relevance and outcome relevant involvement. Electronic Journal of Communication, 23(3), 1-35. ↩

-

Kahlor, L., Dunwoody, S., Griffin, R. J., & Neuwirth, K. (2006). Seeking and processing information about impersonal risk. Science Communication, 28, 163-194. DOI: 10.1177/1075547006293916 ↩

-

Weber, E. U. (2006). Experience-based and description-based perceptions on long-term risk: Why global warming does not scare us (Yet). Climatic Change, 77, 103-120. DOI: 10.1007/s10584-006-9060-3. ↩

-

Guion, D. T., Scammon, D. L., & Borders, A. L. (2007). Weathering the storm: A social marketing perspective on disaster preparedness and response with lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 26(1), 20-32. ↩

-

Maidl, E., & Buchecker, M. (2015). Raising risk preparedness by flood risk communication. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 15(7), 1577-1595. ↩

-

Witte, K., McKeon, J., Cameron, K., & Berkowitz, J. (1995). The Risk Behavior Diagnosis Scale (a health educator's tool): Manual. https://www.msu.edu/~wittek/rbd.htm ↩

-

Stewart, A. E. (2015). The measurement of personal self-efficacy in preparing for a hurricane and its role in modeling the likelihood of evacuation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 3(3), 630-653. ↩

-

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55. ↩

-

Kenny, D. (2020, June 5). Measuring model fit. http://www.davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm ↩

-

Lai, K. & Green, S. B. (2016). The problem with having two watches: Assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivariate behavioral research, 51(2-3), 220-239. ↩

-

Chauvin, B. (2018). Individual differences in the judgment of risks: Sociodemographic characteristics, cultural orientation, and level of expertise. Psychological perspectives on risk and risk analysis: Theory, models, and applications, 37-61. ↩

Kirby-Straker, R. & Straker, L. (2023). The Effect of Experiencing Disaster Losses on Risk Perceptions and Preparedness Behaviors (Natural Hazards Center Weather Ready Research Report Series, Report 8). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/the-effect-of-experiencing-disaster-losses-on-risk-perceptions-and-preparedness-behaviors