Children, Teens, and Older Adults in COVID-19

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

Young children, youth, and older adults are often vulnerable during disasters and targeted for interventions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these populations experienced varying types of vulnerability. For older adults (ages 65 or older), their vulnerability is largely attributed to the greater health risks associated with exposure to the virus for this age group. Children and teens (ages 5-18) are less likely to suffer severe complications from COVID-19 infections, but many have fallen behind academically due to school closures. In addition, all three age groups have experienced mental and emotional health concerns associated with isolation and economic and social instability. Indeed, age vulnerability is central in the pandemic, and yet, the voices of the young and old are rarely heard. This ongoing research project explores the lived experiences of children, teens, and older adults in several places in the United States and Canada during the pandemic, focusing specifically on their vulnerabilities, mobilities, and capacities. We used multiple methods—including interviews, online surveys, drawings, mapping activities, focus groups, daily journals, and podcasts—to learn from older adults, children, teens, parents of young children, and key informants in the community. Data collection and analysis is led by an international team of social scientists with backgrounds in sociology, public health, and international development. Results will contribute to better disaster preparedness, response, policies, and support systems that address the specific challenges of these highly diverse groups. A broader understanding of the experiences of children, teens, and older adults is necessary to keep potentially vulnerable populations safe and resilient as the pandemic continues and to prepare us for future disasters.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the vulnerability of children, teens, and older adults. These populations are often vulnerable during and after disasters. With COVID-19, the main risks to these groups have diverged. Older adults are the most likely to experience severe illness, hospitalization, and death from the virus. Children and teens are much less likely to become seriously ill or die from COVID-19, but they have been harmed academically due to school closures in ways that may affect them throughout their life course. There are other concerns that cut across all three groups such as the mental and emotional health effects of isolation, social unrest, and economic instability.

The pandemic has been a time of uncertainty and anxiety for all age groups. But the experiences of children, teens, and older adults—the groups which COVID-19 may have most strongly affected—are strikingly underexamined. There is clearly a gap in our knowledge about the unique perspectives and needs of these populations. We developed this mixed methods research project to provide a deeper understanding of how the lives of children, teens, and older adults have been shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study, which is ongoing and actively collecting data, is examining the specific vulnerabilities of these groups and how they can be reduced. For example, we are documenting the resources that children, teens and older adults have sought, accessed, or needed to navigate the pandemic and how they are processing risk information. We are also revealing how older adults, teens, and children have contributed to their own resiliency.

Literature Review

Children, teens, and older adults have been found to be vulnerable to disasters in ways that are different from the general adult population (Anderson, 20051; Muzenda-Mudavanhu, 20162; Fothergill, 19963; Fothergill & Peek, 20064; Bodstein et al., 20145; Greenberg, 20146; Powell et al., 20097; Kwan & Walsh, 20178; Campbell, 20199). Their vulnerability can be psychological, physical, social, economic, and educational (Muzenda-Mudavanhu, 2016; Fothergill & Peek, 201510; Malik et al., 201811; Fernandez et al., 201212; Barusch, 201113; Staley et al., 201114). Children, for example, may need forms of physical, social, mental, and emotional support distinct from those required by adults to cope with and recover from disasters (Peek & Richardson, 201315; Fothergill & Peek, 2015). While older adults may have greater mental and physical health ailments and needs (Malik et al., 2018; Greenberg, 2014; Fernandez et al., 2012; Barusch, 2011; Staley et al., 2011; Powell et al., 2009; Kwan & Walsh, 2017), their post-disaster activities such as volunteering may facilitate both their own recovery and that of their communities (Campbell, 201616). Though children also benefit from volunteering in a disaster, it is often more difficult for them to find opportunities to do so.

In the pandemic, the vulnerability of older adults is generally attributed to greater health risks and the vulnerability of children and teens is attributed to educational discontinuity. Additionally, research suggests that pandemic-related stressors may be linked with premature brain aging and negative mental health outcomes among youth (Gotlib et al., 202217). Framing the vulnerability of these groups as simply coronavirus-related medical issues or educational concerns, however, is too narrow. Such views are based on talking about these groups rather than with them. Moreover, it defines these groups as passive recipients of interventions, thereby ignoring the important contributions they bring. The tendency to dismiss the agency of presumed vulnerable groups in disasters needs to be rectified (Fothergill & Peek, 2015; Kwan & Walsh, 2017; Campbell, 2019).

As in previous disasters, existing disparities linked to gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, citizenship, religion, and other social determinants of health have been exacerbated during the pandemic (S. Cutter, 200618; S. L. Cutter & Finch, 200819; Enarson, 200020; Fernandez et al., 2002; Fothergill, 1996; Gibb, 201821; McLeman, 201322; Powell et al., 2009). As such, our larger study uses an intersectional approach to better understand how other facets of identity affect the experiences of children, teens, and older adults throughout the COVID-19 crisis (Mullings & Schulz, 2006).

Research Questions

Our research questions reflected the main topics of this project: the daily experiences and mobilities (where they could and could not go during the pandemic) of children, teens, and older adults; their connections with others (including who they could and could not see); the challenges they faced and the coping strategies they used to address these challenges; where they got their COVID information; and how they were helped and helped others. More specifically, we sought to answer the following questions:

- What is the routine and feel of everyday lives of children, teens, and older adults during the pandemic?

- How do these groups mark milestones and holiday celebrations during the pandemic?

- Who is a part (or not a part) of their pandemic lives?

- Where do these groups go (or not go)?

- How does the situation affect their mental and physical health?

- What new challenges do they face and what challenges do they foresee?

- How do they cope with these challenges?

- How do they express agency and resilience?

- How do they help others?

- How do communications from media and government sources impact their risk perception and daily activities?

- How do these experiences and outcomes vary among groups with different characteristics within each of these populations?

Research Design

This project has utilized multiple quantitative and qualitative methods and child-centered and older adult-centered approaches to help broaden our understanding (Peek & Richardson, 2013; Campbell, 2019). Additionally, we have used the restrictions on in-person research necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to develop new research methods or to innovatively combine existing ones. As we have argued in the context of pandemic-catalyzed innovations to research on children and disasters (Gibb et al., 202223), we anticipate that our methodological experimentation will inform disaster research even after the COVID-19 pandemic is over. The following sections describe each of our data collection methods— which, to date, have included journals, drawings, interviews, focus groups and online surveys. We are currently preparing for our podcast research method (described briefly in the ‘future research directions’ section). We plan to share our research instruments through DesignSafe and to further analyze the merits and challenges of the various methods we have used in a methodology-focused scholarly publication. Other study procedures, including our consent and assent processes and broader ethical considerations, are also described in more detail below.

Sampling Approach and Recruitment Strategies

The study has been designed to foreground the voices of children (ages 5-11), teens (ages 12-18), and older adults (ages 65 and over) living in the United States or Canada. We have put 12-year-olds in the teen category for two reasons: (1) The age range of the first COVID-19 vaccines approved for minors was 12 to 17 years old, and (2) We have determined that 12-year-olds can complete the survey on their own without assistance from an adult. Our decision to define older adults as 65 years or older is based on the Medicare age eligibility criteria in the United States and the typical age of retirement and pension eligibility in Canada. This age was also used to identify older adults in the initial guidance from public health agencies about the susceptibility of this population to COVID-19.

We have recognized that children, teens, and older adults do not have one common experience, and that these age groups are diverse in myriad ways. As such, we have aimed to recruit a diverse sample. Our recruitment strategies have included using professional and personal contacts to start snowball sampling; reaching out to relevant organizations found online via email and direct messaging on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram; posting links to our study on relevant Facebook pages; circulating posts on our various social media platforms; and publishing a study website, called Life in COVID study.

Journals

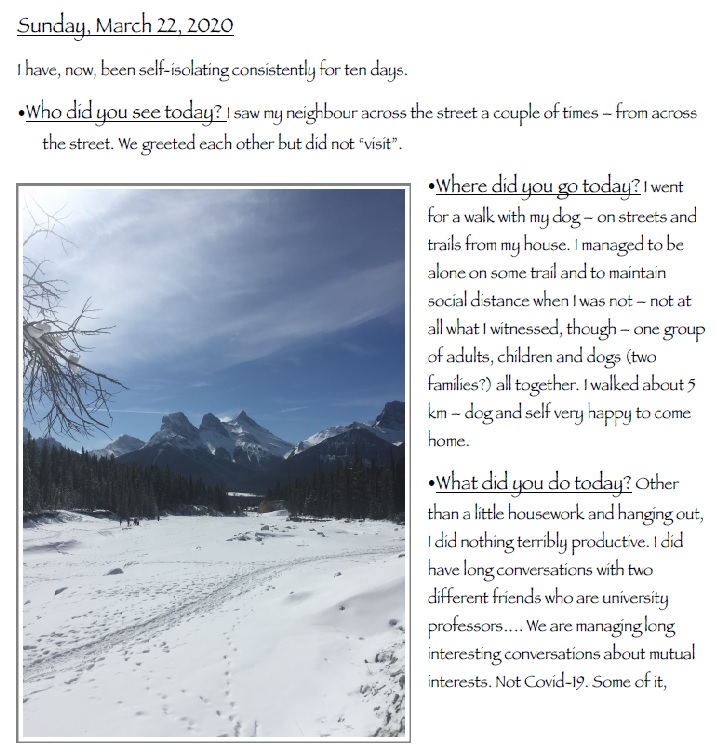

During the period of public health measures that included self-isolation and physical distancing, some research participants kept a daily journal capturing their real-time experiences, emotions, and knowledge. Journaling started in Canada in the spring of 2020 and has continued through April of 2023. Journals include written accounts and pictures drawn or taken by participants, as well as drawings, photographs, and maps of the participants’ movements (e.g., walks in their neighborhood). We have provided five prompts for their daily writing activity: Who did you see today? Where did you go today? What did you do today? How did you feel today, and why? What did you learn about COVID-19 today?

We have collected 20 journals; all but one has been submitted by older adults. Journal formats have ranged from handwritten to email journals to electronic journals submitted regularly by email. Participants have journalled for various periods of time, from six weeks to almost three years. Additionally, one teen has contributed a one-time written retrospective reflection on her pandemic experiences.

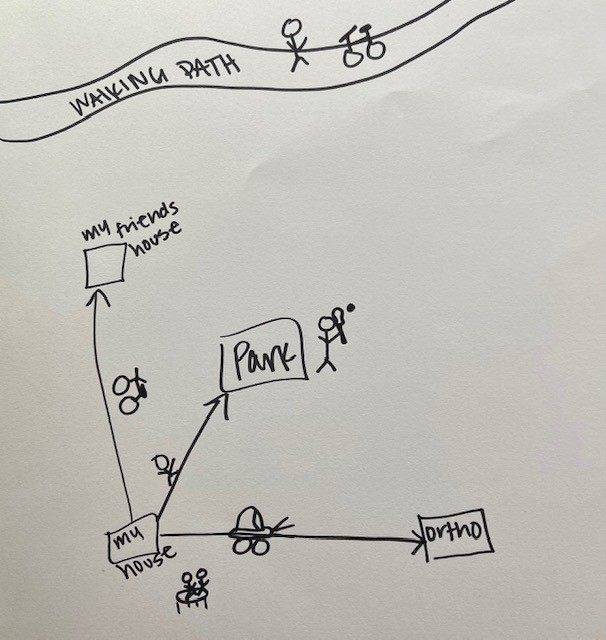

Drawings and Maps

To complement the narratives of research participants as told in their journals and interviews, we have collected drawings and maps made by children, teens, and older adults. Additionally, we have asked children and teens to draw a map depicting the places that have been significant to them during the pandemic during interviews. These maps have been used to help guide the conversation; for example, about their feelings, the important people in their everyday lives, missed milestones, and other topics.

Interviews

We have conducted semi-structured one-on-one qualitative interviews with children, teens, older adults, and key informants in community organizations that have provided services or other support during the pandemic to individuals in these age groups. Initially, all the interviews were conducted online or over the phone. As public health restrictions were lifted, we have requested and received permission from the research ethics review boards at our respective institutions to interview research participants in person.

We have conducted 23 interviews with children, teens, and older adults. Additionally, we have conducted 12 interviews with key informants, for a total of 35 interviews. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes to two hours.

Focus Groups

Our study includes focus groups. We adapted to pandemic restrictions on in-person activities and held online discussion-based focus groups with teens. The focus groups have provided a space for research participants to explore their pandemic experiences with others in their age cohort.

We have conducted three focus groups. We recruited the teens for the focus groups through a community organization in Texas that we have collaborated with during the project. Each focus group was moderated by a core member of our research team. Focus groups lasted approximately one hour to two hours. The total number of participants across the focus groups was 11.

Surveys

We developed an online survey about the COVID-19 experiences of children, teens, and older adults. The survey was distributed by Qualtrics in the United States and Canada in English, French, and Spanish. Qualtrics recruited a representative sample from various sources, including permission-based networks, social media, and member referrals. The company sent an email to older adults, the parents or guardians of child participants aged 11 and under, and adolescents aged 12-18, inviting them to complete an online survey on their COVID-19 experiences and provide demographic information. Survey respondents were compensated by Qualtrics at the amount they agreed upon when they entered into the survey (e.g., SkyMiles, points at retail outlets, gift cards). To date, only one participant has requested a paper copy of the survey, which we mailed to them and they returned by regular mail. All other surveys were submitted through the secure data gathering application Qualtrics.

We conducted a pilot survey in 2021. This survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete and had very low response rates, but provided some valuable pilot data. In 2022, we revised the survey instrument and created a shorter version that took approximately ten minutes to complete. We also contracted Qualtrics to recruit a representative sample. We decided that these changes were necessary to improve response rates. For this report, we only analyzed responses from the shorter 2022 survey.

We received 1,036 surveys from older adults, 1,029 from the parents or guardians of 5-11-year-old children, and 1,017 from teens ages 12-18. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of our survey sample. Note that older adults were asked questions about educational attainment and housing type that were not included on the other two surveys.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Survey Sample

Ages 5-11 (N = 1,029) |

Ages 12-18 (N = 1,017) |

Ages 65 and Over (N = 1,036) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | United States | ||||||

| Canada | |||||||

| Gender | Female | ||||||

| Male | |||||||

| Gender Non-Conforming/ Nonbinary | |||||||

| Another Gender Identity | |||||||

| Prefer not to say | |||||||

| Age | 5 (Child) | ||||||

| 6 (Child) | |||||||

| 7 (Child) | |||||||

| 8 (Child) | |||||||

| 9 (Child) | |||||||

| 10 (Child) | |||||||

| 11 (Child) | |||||||

| 12 (Teen) | |||||||

| 13 (Teen) | |||||||

| 14 (Teen) | |||||||

| 15 (Teen) | |||||||

| 16 (Teen) | |||||||

| 17 (Teen) | |||||||

| 18 (Teen) | |||||||

| 65-69 (Older Adult) | |||||||

| 70-74 (Older Adult) | |||||||

| 75-79 (Older Adult) | |||||||

| 80-84 (Older Adult) | |||||||

| 85-89 (Older Adult) | |||||||

| 90-94 (Older Adult) | |||||||

| 95+ (Older Adult) | |||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | White/ Caucasian | ||||||

| Black/African American/Canadian | |||||||

| Indigenous/Native American/Alaska Native | |||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | |||||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | |||||||

| Other | |||||||

| Prefer not to say | |||||||

| Education | Less than a high school diploma | ||||||

| High school diploma or equivalent | |||||||

| Vocational school | |||||||

| Some bachelor’s degree or equivalent | |||||||

| Bachelor’s degree or equivalent | |||||||

| Graduate degree | |||||||

| Doctorate | |||||||

| Other | |||||||

| Housing | Single-family home | ||||||

| Multi-unit building without age restrictions | |||||||

| Retirement community | |||||||

| Assisted living facility | |||||||

| Other | |||||||

The 2022 Qualtrics survey had much higher response rates than our pilot and bolstered overall participation in the study. However, Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) and adults older than age 70 were underrepresented in our sample. Using Qualtrics to recruit participants likely depresses participation from groups who lack internet access or have less digital literacy. This limitation is valid for all age groups, but may be especially pertinent for adults over age 70. As such, results from this survey must be understood with the caveat that the views of populations with limited internet access or digital literacy are not adequately represented.

Data Analysis

Both qualitative and quantitative tools are being used for our data analysis. Preliminary quantitative data from the Qualtrics survey are presented as descriptive statistics in this report. Qualitative data from the interviews, journals, and focus groups have been coded using an open coding strategy. Each transcript is being coded by one member of the research team and then checked by another to ensure consistency of code application and clarity of code definitions. The coding of the interviews, focus groups, and journals is ongoing. For this report, we use quotes and other excerpts from the qualitative data as examples of the major survey findings. The qualitative data also bring to life participant voices and put their experiences into a richer context.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

We received official ethics approval, after a long process, at two of our universities. As part of our ethics procedure, all study participants aged 18 years or older have completed an online consent form or have given oral consent. All study participants aged 17 years and younger have completed an online assent form or have given oral assent, and their parent or guardian has completed an online consent form or has given oral consent. We are using two versions of the consent/assent forms: one for children and youth ages 18 and under and one for adults ages 65 and older. These forms are available in English and French via our study website.

Our research team includes four core researchers from Canada and the United States, plus several graduate and undergraduate student assistants from three universities in both countries. It has been a goal of the core team to employ a diverse group of assistants. The core team has placed a high priority on the ethics of the research project, having thoughtful discussions about the data design and collection in bi-weekly meetings. We have been cognizant of how the pandemic has caused profound distress and loss, and the inequities of those losses, and have strived to be sensitive to the needs and experiences of our participants. We have understood the dangers of a “gold rush” approach to disaster research (e.g., Gaillard & Gomez, 201524), and have tried to move slowly, carefully, and deliberately. It is important to us to teach our research assistants about disaster research ethics and to model ethical research planning.

Our research is shaped by our positionalities in terms of age, gender, career status, race, ethnicity, religion, and country of origin. We have also been guided by who we are in our relation to others – as spouses and partners, parents of young children and college-aged children, and (grand)children ourselves of aging (grand)parents. Our own social locations and relationship statuses have influenced how we have designed our study, what questions we have asked, and how we have conducted the research.

Dissemination of Findings

We will disseminate our findings through multiple channels, as we are committed to reaching a wide audience, including academics, practitioners, and policy makers. We have written journal articles and have presented our findings at conferences, including at the Annual Natural Hazards Workshop in 2020, 2021 and 2022. In addition, we will be creating podcasts and utilizing podcasting as a data construction, analysis, and dissemination method.

Findings

In this section, we will present our preliminary findings. We have divided our discussion into four themes: the emotions that study participants have felt during the disaster, the challenges they have faced, the coping strategies that they have used, and the ways in which they have been able to help others. It is important to acknowledge that the disaster is still ongoing, particularly for older adults, those who are immunocompromised, and those who are suffering from long COVID.

Emotions

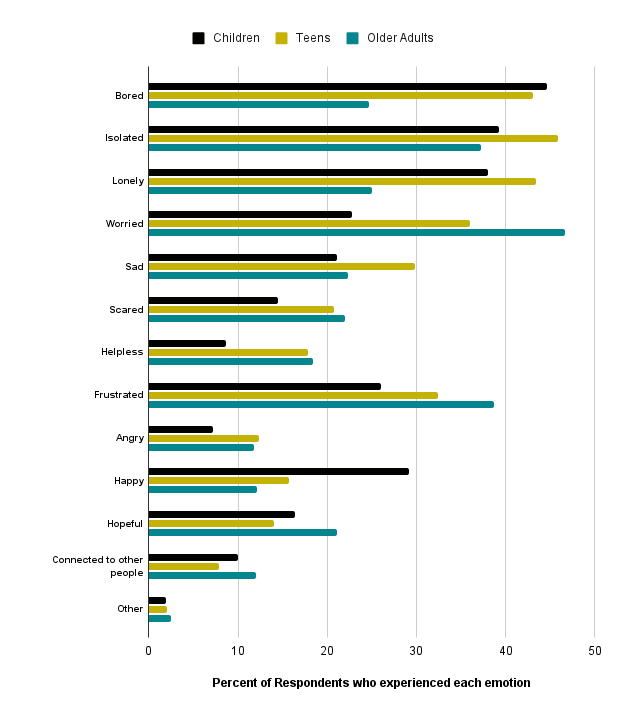

The impacts of the pandemic are evident in the emotions experienced by our research participants. In response to the survey question “Which of the following best captures how your child has felt during the pandemic? Choose as many as apply,” parents and guardians reported that the most common emotions felt by their children during the pandemic included boredom (44.62%), isolation (39.28%), and loneliness (38.02%), as detailed in Figure 1. Similarly, teens most frequently reported feeling isolated (45.84%), lonely (43.40%), and bored (43.10%). The emotional impacts among older adults differed somewhat, as the most commonly reported emotions among this group included feeling worried (46.62%), frustrated (38.71%), and isolated (37.26%). It is noteworthy, however, that feelings of isolation ranked within the top three emotions reported by all groups.

Figure 1. Emotions Experienced by Children, Teens, and Older Adults in the United States and Canada During the COVID-19 Pandemic

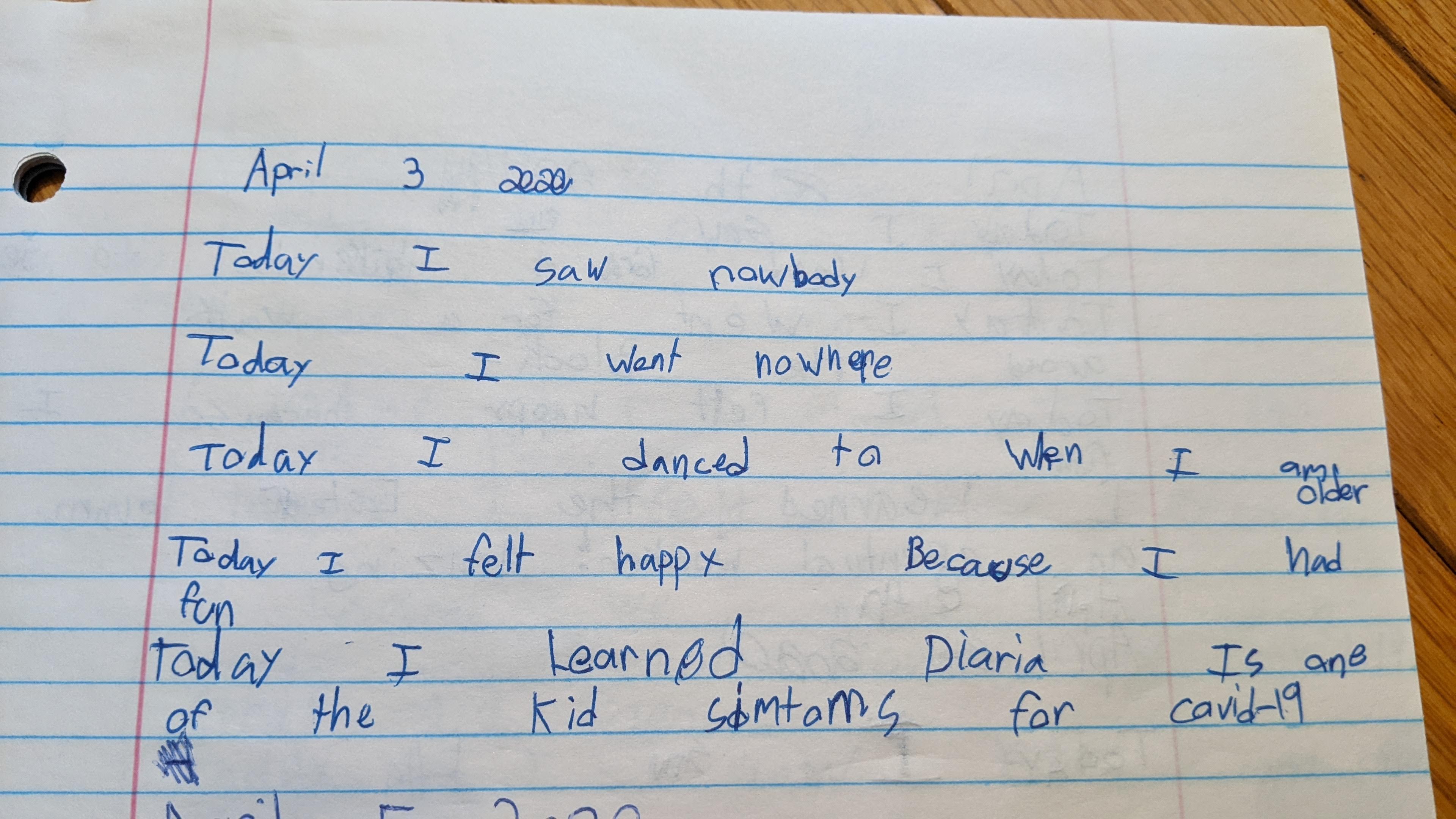

While the lockdown at home was isolating for many young people, they also experienced periods of joy. Even so, many children and youth felt that interacting with the people in their household was not enough to counteract their feeling of isolation from the social world. As shown in Figure 2, one 7-year-old child in Canada wrote the following in her journal:

April 3 2020 Today I saw nowbody [nobody] Today I went nowhere Today I danced [to the song] when I am older Today I felt happy Because I had fun Today I learned diaria [diarrhea] is one of the kid simtoms [symptoms] for covid-19

Figure 2. Journal Entry From Seven-Year-Old Child.

Challenges

Table 2 displays the major challenges that children, teens, and older adults in our study experienced during the pandemic. Below, we discuss each of these challenges in more detail.

Table 2. Challenges Experienced by Children, Teens, and Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Conflict with family members or friends | |||

| Difficulty using technologies (e.g., Zoom, webinars) | |||

| Fear of going out and catching COVID-19 | |||

| Financial challenges or worries | |||

| Medical challenges or worries that I experiencedd | |||

| Medical challenges or worries that someone close to me experiencedd | |||

| Missing important milestones (e.g., birthdays, graduations) | |||

| Missing summer campe | |||

| Not being able to do my own groceries/ shoppingd | |||

| Not being able to do my usual activities | |||

| Not being able to go to schoole | |||

| Not being able to go to the park or other recreational facilitye | |||

| Not being able to visit friends | |||

| Not being able to visit grandchildren/ other relativesd | |||

| Not being able to visit grandparents/ other relativese | |||

| Ostracized for my views about the pandemicf | |||

| Staffing shortages at my residenced | |||

| Struggling to keep close relationshipsf | |||

| Other | |||

| None of the above | |||

Challenges: Children and Teens

Our preliminary analysis of the survey results shows that children and teens have been managing several challenges during the pandemic. Their major challenges involved feelings of loneliness and boredom at home, difficulties with remote school, and decreased connection with friends and family. As shown in Table 2 the top five challenges for children were not being able to visit friends (61.98%), not being able to go to school (61.20%), not being able to do their usual activities (43.84%), missing important milestones (37.63%) and not being able to visit grandparents or other relatives (35.40%). For teens, the top five challenges were not being able to visit friends (60.89%), not being able to do their usual activities (47.77%), missing important milestones (42.42%), not being able to go to school (41.93%), and fear of going out and catching COVID-19 (41.15%).

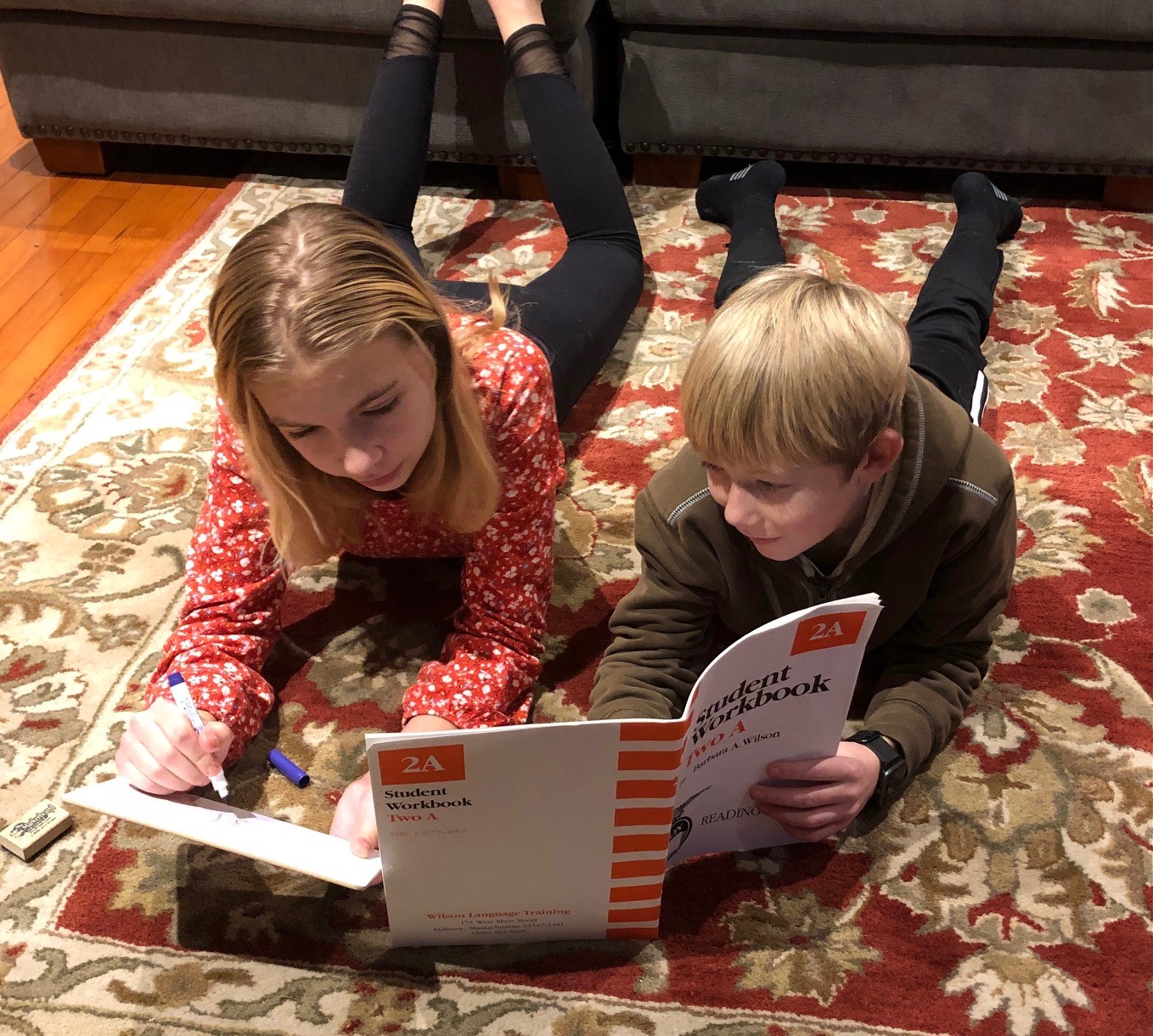

When the pandemic hit and school went remote, children and teens throughout the United States and Canada had to remain at home for the remainder of the 2019-2020 school year. The experiences of children and youth with homeschooling during this period were mixed, but largely difficult. Interestingly, even though most children and teens reported having difficulties with remote schooling, a majority also said they liked doing schoolwork at home as opposed to disliking it. The mixed experiences continued through the 2020-2021 school year, as students continued with full-time online instruction, returned to in-person instruction, or participated in a hybrid in-person and online school year. Interviews with teachers underlined that the pandemic-related changes to usual school routines and the uncertainty about when schools, and even individual classes, would be open for in-person instruction have been particularly challenging for students and teens with pre-existing difficulties with learning.

In a journal entry, a U.S. teen wrote about the difficulties of attending her school remotely: “I struggled a lot with online school mainly because it just wasn’t an impactful way of learning. I’m more of a visual and in person type learner so that first semester was pretty rough.” In a focus group with U.S. high school students, one participant spoke of the difficulty of learning at home:

But then junior year hit, and teachers, they made everything online [and it made it] so much worse. And so I didn't get to go to school, right? ... So at that point, I really regretted not being able to go to school.

Interviews, journals, and focus groups showed that the challenges faced by children and teens were shaped by their knowledge of COVID-19, their household’s COVID-related rules (e.g., around mask-wearing), and how these norms were respected or violated in other spaces. Young people learned about COVID-19 impacts by observing people in their daily lives; for example, elementary school students noted mental health challenges faced by older siblings. Many young people were also aware of the scientific discussion about how coronaviruses are transmitted and the public health guidelines and restrictions put in place to limit the spread of infections. It was challenging for young people to negotiate situations where others did not adhere to their understanding of public health guidelines. As one primary school teacher in Canada noted in an interview, varying levels of awareness and interest in adhering to pandemic rules created a unique set of boundaries and uncertainty in social norms among students:

I think in this past school year, the first year of in-person during a pandemic school, there was a lot of figuring out new boundaries between the students themselves. I guess the ones who felt like [they] knew a little bit more about the pandemic, or whose family were very strict about what rules they were following versus whatever another family who maybe weren't as vocal about how they were observing the pandemic, if you will. So the kids were moving along a little bit more unaware of what was okay or what wasn't okay, or what this new normal looked like. So that being the kids who would have their masks down and be walking around because they just ate their snack and were going to go get something to wipe their face, as compared to the kids who double-masked and sat away, and only ate their snack if they were not sitting near anybody else. Like, figuring out, "Okay, you are my friend, but you're doing something I'm uncomfortable with, but I don't know how to tell you. And I don't know if I should be uncomfortable, if you should be uncomfortable." The social aspect was certainly interesting to observe. There certainly wasn't a lot of clear, "Ah, here is the line where we will both agree on," because as kids, it's hard for them to express what might be making them uncomfortable, or why. There were a lot of times where mediation was necessary, or an overall class discussion about a situation.

Challenges: Older Adults

Older adults also reported experiencing a range of challenges during the pandemic. As shown in Table 2 the top five challenges they reported in the survey were fear of going out and catching COVID-19 (54.05%), not being able to visit friends (50.87%), not being able to do their usual activities (48.46%), missing important milestones (42.47%) and not being able to visit grandchildren or other relatives (40.06%).

One U.S. participant captured a common sentiment among our research participants in her daily journal, writing on May 16, 2020, that she was feeling, “tired, low key, maybe borderline depression. Almost on the verge of tears often lately—sometimes the prospect of endless social and economic upheaval, social distancing, and incredible asinine U.S. political leadership is overwhelming.”

Although difficulty using technologies (e.g., Zoom, webinars) was reported as a challenge by only 8.78% of older adult survey respondents, many interviewees in this age cohort underscored the shortcomings of online social interactions. They noted that videoconferencing platforms did not work well for gatherings of friends and family, especially with grandchildren who all wanted to speak at once. One Canadian woman passionately recalled how she avoided video-conferencing with multiple grandchildren:

I hated it! You’ve got all these people on the screen and they’re all interrupting each other. That is not a substitute for anything, it [is] just the recipe for frustration. I said I would rather just do one at a time or not at all. And so, now we Facetime, which I like a lot better. Zoom is fine one on one, but not when you’ve got this whole group of people. I don’t think it works at all. I think it’s very stressful.

A social worker in New York City whose agency serves low-income older adults noted in an interview that her clients do not have any access to the internet and very few, if any, skills with technology. She saw how they were isolated by the digital divide and that this isolation worsened during the pandemic. As she stated, “The real loneliness, because they're not, [the] majority are not technological. They're not going to be on the internet. They're not going to be doing FaceTime. They're going to be more cut off.”

Comparison

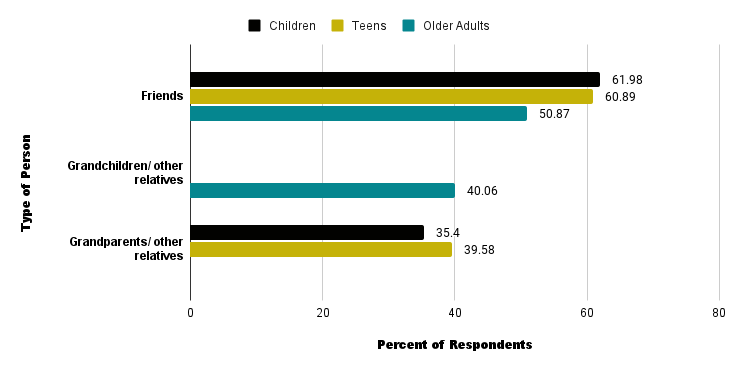

The survey revealed that children, teens, and older adults reported many similar challenges during COVID-19. Figure 3, for example, shows that more than half of each group felt that not being able to visit friends was challenging. Nearly 40% of each group also found it difficult to be isolated from extended family members, including grandparents or grandchildren.

Figure 3. Percentage of Children, Teens, and Older Adults Who Reported Being Unable to Visit Others as a Challenge

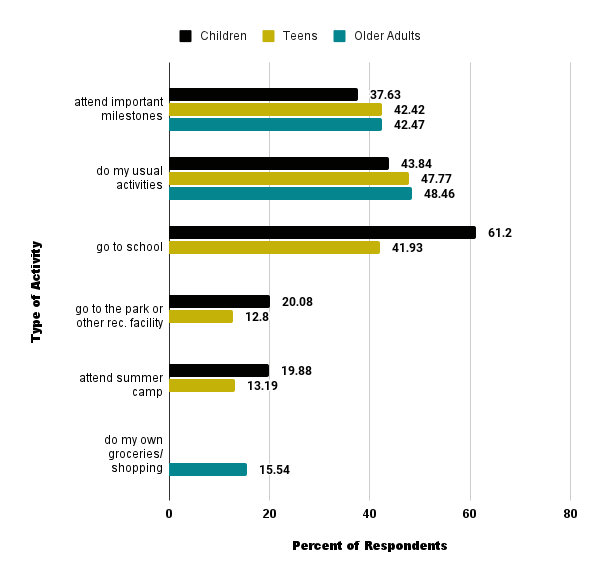

Another challenge that children, teens, and older adults all perceived was missing activities outside the home. Figure 4 shows that roughly 40% of all three groups found it challenging to miss events marking milestones, like birthdays or graduations whereas approximately 45% felt it was difficult to miss their usual activities.

Figure 4. Percentage of Children, Teens, and Older Adults Who Reported Missing Activities as a Challenge

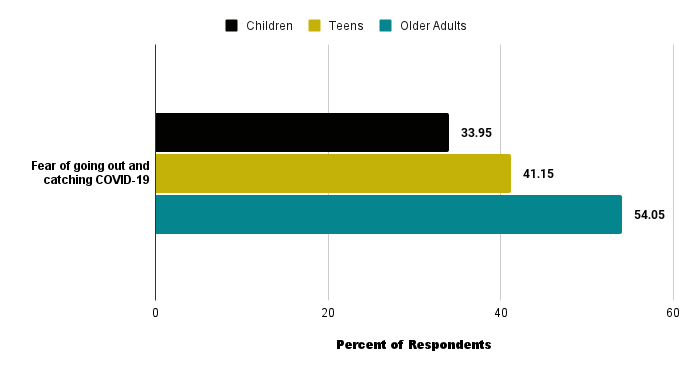

Figure 5 shows that more older adults reported that they feared going out and catching COVID-19 than children and teens. More than 54% of older adults said that their fear of being exposed to the virus during trips outside their home was a challenge. While children and teens were less likely to report their fear of exposure as a challenge, a substantial percentage still found it difficult—41% of teens and 34% of children.

Figure 5. Percentage of Children, Teens, and Older Adults Who Reported Fear of Going Out and Catching COVID-19 as a Challenge

Coping Strategies

Table 3 displays the coping strategies that children, teens, and older adults reported using during the pandemic. Bolding represents the top three most frequent responses for each age group. Below, we discuss the major coping strategies used by each group in more detail.

Table 3. Coping Strategies During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Connecting with friends remotely | |||

| Connecting with grandparents/ grandchildren and other family members remotely | |||

| Playing video gamesd | |||

| Spending more time watching TV or readinge | |||

| Spending time with a pet | |||

| Connecting with teachers and classmates remotelyd | |||

| Buying extra food, toilet paper, or other household suppliese | |||

| Talking or playing with neighbors | |||

| Learning a new skill or hobby | |||

| Keeping a diary, creating art, writing poetry, songs, memes, etc. | |||

| Participating in remote activities (i.e., fitness classes, religious services)e | |||

| Participating in web-based activities (e.g., online arts, music, fitness, or other activities) d | |||

| Evaluating my financial situation (i.e., budgeting, refinancing, estate planning)e | |||

| Talking with a trusted adult, such as a teacher, counselor, therapist, or social workerd | |||

| Using telehealth or videoconferencing for medical appointmentse | |||

| Talking with a counselor, therapist, or social workere | |||

| Using a delivery service for groceries, medication, or other goodse | |||

| Volunteering | |||

| Becoming more politically active (i.e., attending rallies/protests)f | |||

| Other | |||

| None of the above | |||

Coping Strategies: Children and Teens

As displayed in Table 3, the survey showed that children and teens had largely similar coping strategies with only slight variation. For children, the most common coping strategy was connecting with friends remotely, followed closely by playing video games, and connecting with grandparents and other family members online. For teens, the two most frequent coping strategies were connecting with friends remotely and playing video games. In contrast to children, teens’ third most frequent strategy was spending time with a pet.

Most teens and children did not report using coping strategies that they thought were harmful. Some however, did use strategies they felt were bad for their health and wellbeing (5.05% among children and 5.01% among teens). For teens, the most frequent harmful strategies included substance use (of alcohol, marijuana, nicotine, and other drugs) and an excess of Internet and screen time, particularly video games. For children, the most common activities that parents or guardians felt were harmful were increased screen time and time spent playing video games. A smaller number of children and teens turned to acts of self-harm or aggression to cope.

The qualitative data revealed several productive or positive ways that children and teens found for coping with the pandemic. For example, one 11-year-old in the U.S. said that she “did a lot of cooking” and spent a lot of time tidying up after her family members “just so we’d have a room in our house that was clean” and not cluttered as a result of everyone working from home. This same child also said that after “remote school,” she and her friend would coordinate to meet outside on the road and do science experiments they had researched themselves, including making “elephant toothpaste.” One elementary school social worker in New York remarked, “some students really focused on their academics and the Chromebook [given to all students in the New York public school system] as a way to cope and stay connected.”

However, the qualitative data also showed that some children and teens coped in ways that they felt were unhealthy or harmful to their wellbeing. For example, one teen participant commented that he played NBA 2K “all day” as his “coping mechanism,” and that “most kids just watched a lot of Netflix and stuff like that.” In terms of academics, some teens resorted to plagiarism for their written assignments when working from home, according to a high school teacher in New York.

Coping Strategies: Older Adults

Older adults reported somewhat similar coping strategies as children and teens on the survey. Their most frequent coping strategies were spending more time watching television or reading, connecting with friends remotely, connecting with grandchildren and other family members remotely, talking with neighbors, and purchasing extra household supplies.

The qualitative data revealed how older adults valued these strategies. A grandmother in Vermont, for example, explained how she felt about being away from her grandchildren in the pandemic, and how video-conferencing was a strategy she used to remain connected with them:

And it was heartbreaking for us that we couldn't see them [her grandchildren]... So we're doing the best you can with FaceTime. The youngest girls are soon to be six and seven, so we've been seeing them on screen, but it's not the same. I did see a commercial about hugging your grandchildren, and that's very true. It's a big deal. So, we've missed them.

Older adults also discussed the importance of watching television or reading as a coping strategy in interviews and their journals. One interviewee described the value of such activities during the pandemic, stating: “Staying in [is] still the best approach – glad that I like reading and a few TV programs and doing puzzles and working in my studio, writing short articles…. Keeps me out of ‘trouble,’ for sure.”

Similar to children and teens, most older adults did not report in the survey that they used coping mechanisms that they thought were harmful. However, among the minority who did use harmful coping mechanisms (3.96%), the most commonly cited were substance use (including alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco) and overeating.

Helping Behaviors

As shown in Table 4, our preliminary analysis demonstrates that children, teens, and older adults found ways to help other people during the pandemic. Bolding represents the top five most frequent responses for each age group.

Table 4. Helping Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Create artwork or food for someone | |||

| Hang a rainbow, heart, or other sign or place a bear in your window or on a door | |||

| Help a sibling with schoolwork d | |||

| Reach out/ provide support (listening, comforting) to a friend or family member | |||

| Run errands for a family membere | |||

| Share your knowledge and experience of past crisesf | |||

| Volunteer | |||

| Clap, bang pots, use noise makers, or sing outside to support essential workers/ healthcare workers | |||

| Create outdoor pandemic-related artworks or treasures/notes for others to findd | |||

| Create pandemic-related educational or inspirational videos or content, and post it onlinee | |||

| Deliver food packages or goods to people in needd | |||

| Help someone get a vaccinee | |||

| Make personal protective equipment to donate (e.g., face masks, face shield)d | |||

| Raise money for/ donate to organizations helping people impacted by COVID-19 | |||

| Take on a job to help your family with expensese | |||

| Attend a protest or rallyd | |||

| Other | |||

| None of the above | |||

Among children, the most common helping behavior reported on the survey was creating artwork or food for others. Nearly one-half of children gave art or food to help someone else. More than one-quarter of children also reported placing something—such as a rainbow, heart, or teddy bear—in their window or door to brighten the spirits of passersby. In addition, nearly one-quarter of children reported helping a sibling with schoolwork or providing support to a family member or friend by comforting or listening.

One 11-year-old in the United States described some of the helping activities she participated in:

We painted rocks and we put them in little gift baskets and then made cards. This was before Christmas break and whatever. And we were like, "Happy Holidays," and we gave them to that senior living place and it really brightened their day. And I would also, since we have a river...behind our house, me and my neighbor [another child], we'd go out, we'd get our boots on and we'd go find rocks in there, and we would paint them and then put them around the neighborhood.

Among teens, the survey showed that the most common helping behaviors were providing support to a friend (e.g., by listening) and running errands for a family member. Notably, nearly one-quarter of teens reported helping their siblings with schoolwork and a similar number created food or artwork for others.

Among older adults, the survey showed that nearly half of respondents reached out to a family member or friend to provide support by comforting or listening. This was the only helping activity that a substantial number of respondents carried out in this age group. Approximately one-third of older adults reported doing no helping activities. We cannot, however, distinguish between survey respondents who did no helping activities from those who did not perceive their actions as helping activities. Indeed, in interviews, some older adults initially stated they did not help others, but later recounted instances of assisting neighbors and family members. Further analysis will shed light on this finding.

An older adult in New York spoke in an interview about how helping individuals older than herself helped her emotionally and mentally by keeping her occupied:

I ran little errands for seniors who didn't want to leave the apartment and needed someone to go to the store from them. And so that's what kept me busy. I say two years flew right by because I try not to pay attention to it....I don't even know how to describe this pandemic, how it took over the globe.

Conclusions

Key Findings

Our findings speak to a variety of ways in which children, teens, and older adults experienced the COVID-19 pandemic. Its emotional impacts were comparable among all three populations, with isolation emerging as the most commonly felt emotion. In addition to isolation, children and teens also frequently felt boredom and loneliness, while older adults most commonly experienced feelings of worry and frustration. All three age groups experienced challenges during the pandemic. The most common challenges among survey respondents were the inability to socialize with people outside their immediate household and disruptions to their normal routines. Not being able to visit friends, not being able to do their usual activities, and missing important milestones were among the top three challenges reported in each age group. Despite generational differences, children, teens, and older adults generally coped with these challenges by connecting with friends and family online and spending more time using the Internet on their smart phones or computers and watching television.

Our study also found that children, teens, and older adults have found ways to help others in the pandemic. They assisted in tangible ways—such as making meals and running errands for others— and also did the emotional labor of checking in on loved ones to see how they were faring during lockdown. Many young children created artwork and food for others, and many teens and older adults reached out to listen and support family and friends. Providing this type of emotional support is vital yet often invisible, often taking place in the private sphere and not framed as helping behavior. We anticipate that when the study is complete, we will have specific recommendations for policy and practice.

Limitations

As our sample is limited to North America, the results reported here may not necessarily be generalizable to other parts of the world. The experiences of the pandemic—including factors like case numbers, isolation/masking mandates, school closures, and socio-economic consequences—varied across countries and regions, which likely produced differing outcomes that cannot be universally addressed.

In addition, future research should aim to assess the experiences of groups with less internet access or digital literacy. This might involve doing in-person interviews, surveys, or other fieldwork.

Future Research Directions

The data and results presented in this report are still preliminary, and while they provide valuable insight, they are not complete. Moreover, our mixed-methods approach involves various methodologies that have yet to be analyzed and considered in their entirety. In building off the insights drawn from this study, future research should involve using our findings to continue to develop and investigate interventions for groups that are particularly vulnerable during times of disaster.

Podcasts

Finally, we are developing an intergenerational podcast. Like radio, the podcast is an intimate bridging medium that enables boundaries of knowledge and context to be crossed and can be easily created by individuals sited at different locations (Orfanella 199825; Swiatek, 201826). In a bridging activity, a young person will be paired with an older adult to co-create a podcast; brainstorming questions, interviewing each other about their COVID-19 experiences, reading excerpts from their journals, and deciding which exchanges are ultimately included in the podcast. Transcripts of the entire process of the podcast creation will be used as a data source for research analyses. In this way, the podcast will be used as a tool for data construction, data analysis and research dissemination.

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to thank Akram Salih, Alexandra Repper, Alyssa Koutras, Connor Hendricks, Danielle Campbell, Eliza Erman, Elizabeth Leier, Elyse Gregory, Emilie Boulette, Emma Kearns, Jagnoor Saran, Laura Parent, Liz Siegfried, Logan Iwanoff, Mac Gaither, Madison Lavery, Kate Lord, Olivia Alleyne, Onsum Woo, Osas Iyalekhue, Raina Barara, Tamara Khudair, Tony Dinh, and Valérie Charest for their help with this project and report. Additionally, the authors would like to expression their gratitude to Unite and Inspire team for their ongoing support of this study.

References

-

Anderson, W. A. (2005). Bringing children into focus on the social science disaster research agenda. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 23(3), 159. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072700502300308 ↩

-

Muzenda-Mudavanhu, C. (2016). A review of children’s participation in disaster risk reduction. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 8(1), 270. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v8i1.218 ↩

-

Fothergill, A. (1996). Gender, Risk, and Disaster. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 14(1), 33-56. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072709601400103 ↩

-

Fothergill, A., & Peek, L. (2006). Surviving Catastrophe: A Study of Children in Hurricane Katrina. Learning from catastrophe: Quick response research in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, 97-129. ↩

-

Bodstein, A., Lima, V., & Barros, A. (2014). The vulnerability of the elderly in disasters: The need for an effective resilience policy. Ambiente & sociedade, 17, 157-174. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-753X2014000200011 ↩

-

Greenberg, M. R. (2014). Protecting seniors against environmental disasters: From hazards and vulnerability to prevention and resilience. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203763346 ↩

-

Powell, S., Plouffe, L. & Gorr, P. (2009). When ageing and disasters collide: Lessons from 16 international case studies. Radiation Protection Dosimetry, 134(3-4), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncp082 ↩

-

Kwan, C., and Walsh, C. A. (2017). Seniors’ disaster resilience: A scoping review of the literature. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 25, 259-273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.010 ↩

-

Campbell, N. (2019). Disaster recovery among older adults: Exploring the intersection of vulnerability and resilience. Emerging Voices in Natural Hazards Research, 83-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815821-0.00011-4 ↩

-

Fothergill, A., & Peek, L. (2015). Children of Katrina. Austin: University of Texas Press. ↩

-

Malik, S., Lee, D. C., Doran, K. M., et al. (2018). Vulnerability of Older Adults in Disasters: Emergency Department Utilization by Geriatric Patients After Hurricane Sandy. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 12, 184-193. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2017.44 ↩

-

Fernandez, L. S., Byard, D., Lin, C-C, et al. (2012). Frail elderly as disaster victims: Emergency management strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 17, 67-74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00000200 ↩

-

Barusch, A. S. (2011). Disaster, vulnerability, and older adults: Toward a social work response. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 54(4), 347-350. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2011.582821 ↩

-

Staley, J. A., Alemagno, S., & Shaffer-King, P. (2011). Senior adult emergency preparedness: What does it really mean? Journal of Emergency Management, 9, 47-55. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2011.0079 ↩

-

Peek, L., & Richardson. K. (2013). In their own words: displaced children's educational recovery needs after Hurricane Katrina. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 4, S63-S70. https://doi.org/10.1001/dmp.2010.10060910 ↩

-

Campbell, N. (2016). Trial by flood: experiences of older adults in disaster. Boulder: University of Colorado. ↩

-

Gotlib, I. H., Miller, J. G., Borchers, L. R., Coury, S. M., Costello, L. A., Garcia, J. M., & Ho, T. C. (2022). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and brain maturation in adolescents: Implications for analyzing longitudinal data. Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2022.11.002 ↩

-

Cutter, S. (2006, June 11). The geography of social vulnerability: Race, class, and catastrophe. Items.

https://items.ssrc.org/understanding-katrina/the-geography-of-social-vulnerability-race-class-and-catastrophe/ ↩ -

Cutter, S. L., & Finch, C. (2008). Temporal and spatial changes in social vulnerability to natural hazards. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105, 2301-2306. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0710375105 ↩

-

Enarson, E. (2000). Gender and natural disasters. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/---ifp_crisis/documents/publication/wcms_116391.pdf ↩

-

Gibb, C. (2018). A critical analysis of vulnerability. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 28, 327-334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.11.007 ↩

-

McLeman, R.A. (2013). Climate and human migration: past experiences, future challenges. New York: Cambridge University Press. ↩

-

Gibb, C., Campbell, N., Meltzer, G., & Fothergill, A. (2022). Researching children and disasters: What’s different in pandemic times? Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 26(2), 83-98. ↩

-

Gaillard, J. C., & Gomez, C. (2015). Post-disaster research: Is there gold worth the rush? Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 7(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v7i1.120 ↩

-

Orfanella, L. (1998). Radio: The Intimate Medium. The English Journal, 87(1), 53-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/822022 ↩

-

Swiatek, L. (2018). The Podcast as an Intimate Bridging Medium. Podcasting: New Aural Cultures and Digital Media (pp. 173-187). Springer International Publishing, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90056-8_9 ↩

Gibb, C., Campbell, N., Fothergill, A., & Meltzer, G. (2023). Children, Teens, and Older Adults in COVID-19 (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 354). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/children-teens-and-older-adults-in-covid-19