Damage, Dislocation, and Displacement After Low-Attention Disasters

Experiences of Renter and Immigrant Households

Publication Date: 2021

Abstract

On July 19, 2018, an EF3 tornado went through the small city of Marshalltown, Iowa, damaging many buildings, cars, and trees. The tornado did not cause any fatalities, but the northern part of Marshalltown and its residents suffered significant losses. While Marshalltown residents, like those in many other Midwest communities, were accustomed to tornado alerts, they had not been hit by tornados in recent history and subsequently were not prepared for the magnitude of damage to their community. In particular, the socially vulnerable population—who lived in older housing stock on the east side of the tornado’s path—faced many challenges to rebuilding after the tornado. This quick response research focused on Marshalltown households in the aftermath of the tornado, examining the effects of social vulnerability on tornado housing recovery and thereby addressing a critical gap in post-disaster housing recovery research. By conducting two surveys, researchers were able to examine the level of tornado impact on different types of housing, available recovery resources, and obstacles to accessing certain types of aid. Researchers were also able to collect data on progress in repairing damage and levels of social vulnerability. Results indicate that social vulnerability, specifically low-income and minority status, are associated with disaster impacts, housing damages, slow progress in repairs, and longer recovery periods.

Theoretical Background

Previous research shows that socially vulnerable groups such as minority and low-income populations are disproportionally impacted by disasters with respect to housing (Hamideh et al., 20181; Peacock et al., 20142; Zhang & Peacock, 20103). Disparities in disaster impacts are often manifested in housing damage (Cutter et al., 20144; Van Zandt et al., 20125); housing functionality and employment or school disruptions (Van de Lindt et al., 20186); dislocation (Mitchell et al., 20127); and mental and physical health (Fothergill & Peek, 20158) among other dimensions. Research has found that social characteristics such as race and income are associated with differing levels of damage and different recovery paths (Hamideh et al., 2018). These factors are associated with damage levels because older and poorer-quality housing is often occupied by low-income and minority populations. These socially vulnerable groups are therefore more likely to experience higher levels of damage due to poorer housing conditions (Hamideh et al., 2018).

With vulnerable groups concentrated in higher risk hazard zones, research suggests that these groups also face greater disruption of utilities and longer absences from work and school (Van de Lindt et al., 2018). As expected, losing homes, schools, and workplaces greatly impacts these groups as daily routines are disrupted (Van de Lindt et al., 2018). Recent research has also indicated that disparities in disruption occur among income levels as well as among different racial groups (Van de Lindt et al., 20209).

While extensive damage is expected to force households to relocate for safety, health, and comfort concerns, low-income homeowners who have fewer resources to pay for hotels or short-term rentals tend to stay in damaged and sometimes unsafe, uncomfortable, and unhealthy structures. On the other hand, renters are often dislocated at higher levels due to limited property rights and landlords asking them to leave even if damages are slight. For the displaced families, a network of relatives and friends can be the first line of support for immediate accommodation, and sometimes the only reliable one (Hack, 200610).

Natural hazards usually lead to localized, immediate, and temporary displacement (Oliver-Smith, 200511) when the majority of losses are covered by insurance or other recovery resources in a timely manner (Mitchell et al., 2012). Disasters that affect larger regions and cities involve significant involuntary displacement (Burby, 200612; Dash et al., 200713; Johnson and Olshansky, 201714) that could be handled using a combination of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)-provided trailers and vacant housing units in the local market (Comerio, 201415; French et al., 2008). However, in the absence of temporary housing or vacant units in the local market, which are common conditions in low-attention disasters in small towns, uninsured homeowners are left with very limited options for transitional shelter between their damaged home and a permanent home. Certain groups—such as elderly and those in substandard homes—are at a higher risk of displacement due to the complex challenges they face in recovery (Hamideh & Rongerude, 201816; Mitchell et al., 2012; Van de Lindt et al., 2018).

After disasters, national agencies such as FEMA or the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) often come forward to help communities get back on their feet. FEMA funding usually occurs in the form of covering minimum home repairs as well as in temporary housing assistance. In the absence of FEMA trailers or other temporary housing resources, households may rely on their own resources to work on repairs at a slower pace. Within HUD, funds are often distributed as Community Development Block Grants that can be used to assist with relocation, repairs, and rebuilding (Olshansky & Johnson, 201417). Should the president declare a state of national emergency, the U.S. Disaster Relief Fund also becomes available for communities to draw aid from (Olshansky & Johnson, 2014). Additionally, household recovery is often supplemented by insurance returns. For households without insurance, recovery can be prohibitively costly, leading to delayed recovery or eventual relocation. Given the growing number of low-attention disasters and increasing vulnerability in many communities (Beers, 201718; Mochizuki et al., 201419), it is critical to examine what strategies and resources households use in the absence of substantial federal funds to address their housing needs.

Immigrant households face an additional level of vulnerability as low-income owners of uninsured or underinsured properties in low-attention disasters. The literature shows that discrimination based on race and ethnicity has consequences for access to temporary housing and subsequent displacement (Fothergill et al.,199920; Weil, 200921). Immigrant populations face barriers to disaster recovery due to limited English proficiency, isolation, unfamiliarity with U.S. bureaucratic systems, differences in communication styles (Nguyen & Salvesen, 201422), lower access to credit for getting loans, and lack of documentation needed for assistance applications such as deeds and proof of ownership to qualify for aid. This study examined whether minority and immigrant households have limited access to resources and how that affects their recovery process.

Housing tenure plays a significant role is shaping disaster impact and recovery (Comerio 1998; Hamideh et al., 2018; Zhang & Peacock, 2010). Higher physical vulnerability of rental homes, as well as limited control of renters over recovery decisions and resources leads to a slower rate of recovery among rental housing compared to owner-occupied housing. Contract sale homes, as a hybrid between owner and rental housing without the legal protection of either form of tenure, face a different set of challenges in recovery, including uncertainty about ownership status. Contract sales are often set up as rent-to-own agreements between individuals instead of a mortgage through a bank; therefore, in uncertain situations such as a late payment or disaster destruction, the buyers have little control over their property despite the investment they have made in the house. This study will examine whether and how non-homeowner households, in particular those in contract sale, face different challenges in recovery than owner-occupied housing.

With these key variables in mind, this study examines how minority, immigrant, and renter or contract owner households fared immediately after an EF3 tornado tore through Marshalltown, Iowa in 2018.

Case Study: Marshalltown

Marshalltown, the seat of Marshall County, is located in central Iowa, an hour northeast of Des Moines. The JBS meatpacking plant and Lennox International factory are the major employers in the city (Donahey, 201823), which provides workers with an increasingly rare opportunity to earn a relatively good income (around $30,000 a year) without a college degree (U.S. Census Bureau, 201924). Consequently, this small manufacturing town has grown steadily within the last century, attracting many immigrant workers in the past few decades. The town had a population of 11,500 in 1900, but by 2010 Marshalltown had expanded to 27,500 people, an increase of almost 240% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019).

Not only has the population growth rate of Marshalltown been extraordinary for Iowa, which during this same time period grew only by 36%, but the demographic breakdown is also unusual for the state (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). As a whole, Iowa is around 92.5% non-Hispanic White whereas Marshalltown is only 62% Non-Hispanic White (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). The city is 29% Hispanic, 4.5% Asian, and 1.2% African American, with some indigenous and mixed-race families as well (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). It is also important to note that almost 4,800 residents of Marshalltown are foreign-born (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Of note, Marshalltown hosts large Mexican, Burmese, East Indian, and Salvadoran populations (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Due to the economic opportunities in the city, waves of immigrants arrived, first to work in manufacturing but later branched out to fill other jobs like construction and retail in both the immediate and surrounding areas.

Different races have tended to cluster in different parts of the city depending on socioeconomic status and employment, with the majority of the working class and minority or immigrant populations concentrated in the northeast and central areas of the city. When tracing the path of the July 2018 tornado, some groups suffered more losses than others partly due to this clustering of people along sociodemographic lines.

Tornado of July 19, 2018

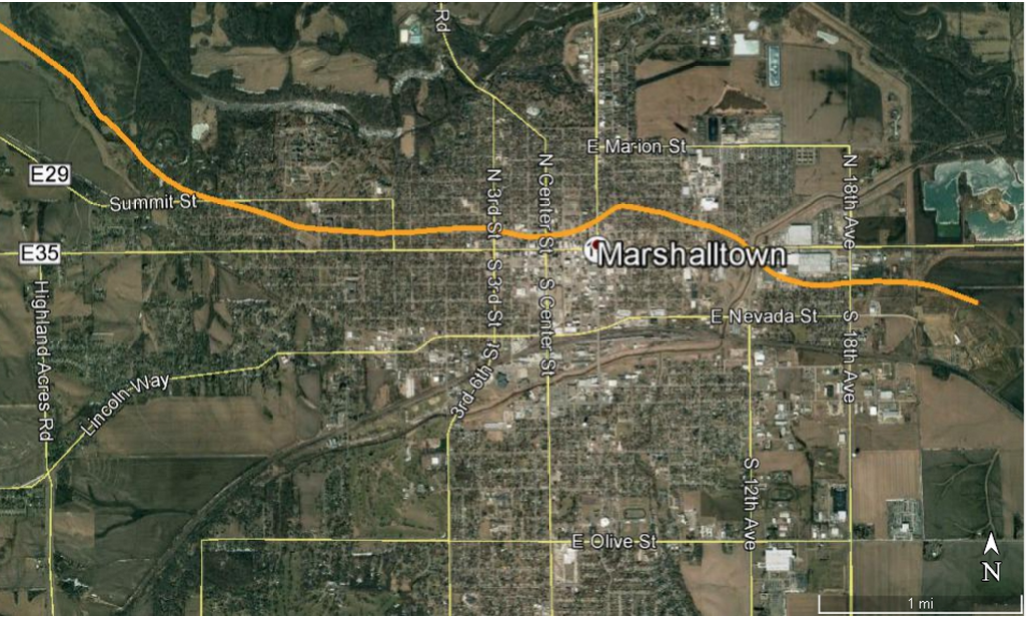

Contained within what is known as Tornado Alley, Iowa ranks sixth in the United States for tornado frequency, averaging 46 tornadoes each year (Iowa Public Broadcasting Service, 201725). 2018 was a particularly catastrophic year for Iowa as the state experienced 69 tornadoes according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (U.S. Department of Commerce & NOAA, 201926). On July 19, 2018, a large tornado struck the city of Marshalltown at 4:30 in the afternoon. Figure 1 shows the tornado path with an orange line in relation to the city. Despite the severity of this disaster—a 3 on the Enhanced Fujita 0-5 scale (U.S. Department of Commerce & NOAA, 201827)—the city received limited attention beyond the local news media. The federal government initially opted out of declaring the situation a federally declared disaster, even though the tornado caused major damage in Marshalltown (Sodders, 201828), and later only approved FEMA Public Assistance funds for the city. Therefore, affected households in Marshalltown were denied Individual Household Assistance from FEMA.

Figure 1. Tornado Path in Marshalltown

Research Questions

Due to Marshalltown’s demographics, this study’s researchers had an opportunity to examine the impacts of a low-attention disaster with respect to damages, dislocation, and displacement of socially vulnerable households. This research addresses the intersection of three gaps in the disaster literature. First, despite high frequency and growing losses from low-attention disasters, there is little knowledge about the unique features that shape and impact recovery efforts after such disasters. Given the growing number of low-attention disasters and increasing vulnerability in many communities (Mochizuki et al., 2014; Beers, 2017), it is critical to examine what strategies and resources households use in the absence of substantial federal funds to address their housing needs. Second, while previous research has shown disparities between the experiences of socially vulnerable populations and other disaster victims, systematic studies that address the effects of housing tenure on disaster impacts are rare, particularly with respect to contract sale homes. Finally, within the social vulnerability literature, the languages spoken at home and household ethnicity are often factors that can affect disaster victims’ access to information and resources after disasters. However, immigration as a factor that can affect visibility and eligibility of disaster victims for assistance and influence their ability to return to work has not received adequate attention. This research examined three questions:

What sociodemographic factors are associated with higher levels of damage, household life disruption, dislocation, and displacement after tornados?

Are there any differences in tornado housing impacts between renter and minority households versus other disaster victims?

Are there any differences in access to housing recovery resources between renter and minority households versus other tornado victims?

Methods

To answer the questions above, two surveys were developed by an interdisciplinary research team consisting of a social scientist, a structural engineer, and an extension and outreach community development specialist. Since the data for this study was perishable, speed was essential and fieldwork began within two months after the tornado as soon as the Iowa State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study with respect to minimizing negative effects on human subjects in the research. The team considered ethical issues in designing and conducting the survey research with vulnerable households such as privacy, confidentiality, and mental health effects from participating in the survey interviews. To gain a random sample while still focusing on areas affected by the tornado, this study used a cluster sampling procedure. Areas affected by the tornado were identified based on the tornado destruction path map of the City of Marshalltown. From the 609 census blocks in Marshalltown, blocks were selected within the target area based on size and sociodemographic characteristics using census data on population, race and ethnicity, housing units and tenure, citizenship status, and income levels, supplemented by American Community Survey estimates at the block group level where necessary. Four to five housing units were selected with households as the primary sample units in each selected block.

The first survey was a multiple-choice damage assessment. This questionnaire was intended to assist in developing a detailed database of the physical characteristics of a sample of residential buildings affected by the earthquake. With questions of building size, age, construction material, and foundation type, a relationship emerged between building composition and tornado damage. The second part of the damage assessment set out to determine damage to the exterior and interior portions of the property as well as analyze the repairs underway at the time of the survey.

When discussing exterior damage to the property, given that the disaster in question is a tornado, the survey focused on the extent and type of roof damage, the percentage of windows and doors breached during the event, and the condition of the garage. Exterior analysis also covered landscape such as fallen trees and deposited debris. Figures 2 and 3 below show two examples of damages to residential structures in Marshalltown. Based on the combined observed damage in the different structure and landscape components, an overall damage assessment was assigned, ranging from (1) None or Superficial Damage to (5) Property Destroyed.

Figure 2. Roof Damaged by Marshalltown Tornado

Figure 3. Siding and Other Tornado Damage

For damage to the interior of housing units, this survey was mainly concerned with identifying the cause of the observed damage, specifically, whether the damage was immediately after the tornado or delayed, and whether the damage was due to wind or exposure to water. To gain a better understanding of the extent of the interior damage this portion of the survey also had a place where residents could describe in their own words the damage they incurred.

Lastly, this damage assessment was also used as a method of identifying what type of physical repairs were underway at the time households were surveyed. This section determined what type of work was being done, what percentage of repairs were completed by the time of the survey, and whether the repairs were done by the residents of the property or were completed through hired contractors.

Along with the initial damage assessment, interviewers went to the sampled addresses and conducted a household survey. As mentioned, this study is dealing with perishable data, so the first thing that had to be determined was whether the houses selected for the random sample were still occupied and if not, whether the residents intend to come back based on the information that neighbors and housing managers shared. The household survey focused on the household members prior to and immediately following the tornado. Specifically, this survey attempted to quantify the disruptive effects the tornado had on families, such as disruption to school or work and for how long; interruptions to water, electricity, or gas for any period of time; displacement and overcrowding, and living in damaged unsafe homes.

During this survey, families were also asked to estimate the repair costs and whether they, as owners, renters, or contract sale renters, had home insurance prior to the tornado that could help cover these costs. In this vein, the study also attempted to determine whether people were applying for financial assistance and what type of relief aid they applied for. Lastly, residents were asked if they plan to move due to post-tornado circumstances, such as damage to their home or movement of jobs caused by the tornado. Using data from this household survey and cross examining it with basic demographic information, the researchers looked to see if there were patterns in certain demographics regarding the level of damage experienced or changes in behavior, such as moving out of Marshalltown due to the effects of the tornado.

Results

Survey results indicated that sociodemographic factors of race, ethnicity, and income were associated with the overall distribution of damage from the tornado. The surveys indicated that minority groups experienced higher levels of damage, across both race and income. Additionally, when looking at utility disruptions, minority households on average had to wait longer for their utilities to be reconnected than Non-Hispanic White households. The survey also found discrepancies between the distributions of damage severity between owned, rented, and contract sale houses. Lastly, the study found that many households—especially renter households—lacked insurance prior to the tornado. This lack of financial resources, along with a shortage of public funds due to absence of a Federal emergency declaration, will make recovery harder for disadvantaged groups in the years to come.

Patterns of Damage

After compiling the survey data, the research team identified several factors that correlated with the distribution of damage, household life disruption, and displacement after the tornado. The patterns highlighted by the data analysis indicate that age, race, socioeconomic status, and tenure were all associated with how much damage families incurred and how fast they were able to start recovery. When discussing damages to residences, this study uses four categorical levels of severity—(1) no damage, (2) slight, (3) moderate, and (4) major—based on the description and perceptions of the residents of their home damage. Examples of damage levels in Marshalltown can be seen in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. Examples of Slight (Top Left), Moderate (Top Right), and Severe (Bottom) Levels of Damage

As Table 1 shows, a higher proportion of Hispanic households experienced housing damage at all levels (slight, moderate, and major) than Non-Hispanic White households, with only 33% of Hispanic households experiencing no damage compared to over 50% of Non-Hispanic White households. Given the smaller proportions of other minority groups in Marshalltown, Asian households, African American and multi-race households had fewer participants in this study; however, of those surveyed, it appears that multi-race households experienced lower levels of damage.

Table 1: Distribution of damage by race-ethnicity

| Race-ethnicity | No damage | Slight | Moderate | Major | Don't know | Total Race-ethnicity |

| Not-Hispanic White | 68 (50.4%) | 37 (27.4%) | 21 (15.6%) | 6 (4.4%) | 3 (2.2%) | 135 (100%) |

| Hispanic | 17 (33.3%) | 14 (27.4%) | 12 (23.5%) | 6 (11.8%) | 2 (3.9%) | 51 (100%) |

| Not-Hispanic Black | 1 (16. 7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (83.3%) | 6 (100%) |

| Other races | 3 (33. 3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 3 (33.3%) | 9 (100%) |

| Two races | 12 (52.2%) | 4 (17.39%) | 3 (13.04%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (8.7%) | 23 (100%) |

| Total Damage | 101 | 56 | 38 | 14 | 15 | 224 (100%) |

Another component affecting social vulnerability is annual income. To examine the relationship between household income and average damage, we recorded the average annual income of those surveyed and then looked for differences in average damage across income levels. The survey distinguished between 15 different income categories to capture the nuances of lower income households. Beginning with households making under $4,000 a year, the survey then divided into $1,000 increases in yearly income up through $12,000. From then on, the range within categories began to increase, from $2,000 increments to $5,000, $10,000, and expanded yet further after reaching a total yearly income of $50,000 with the final income bracket encompassing all households that made $150,000 or more annually. The average income category among the surveyed households is $20,000 to $25,000 and the median is $30,000 to $39,000, which is significantly lower than the median $49,000 income in Marshalltown (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). The negative skew of the income distribution and low average income in the affected area indicates that some of the households affected by the tornado are much lower income. Further breakdown of survey data revealed that the annual household income of a quarter of the surveyed households is below $20,000, and 75% earn less than $75,000 annually.

To examine how household income interacts with damage level, we focused on distribution of damage along three annual income categories based on income quartiles. Category One consists of households that earn below the median income of the sample ($30,000); Category Two includes those who fall within the median and third quartile ($30,00 to $50,000); and the highest category includes households that earn more than $50,000 or the highest quartile of the sample. Table 2 captures the distribution of damage levels by income, looking at both the number and the percentage of households surveyed for each group. First, as seen in Table 2, in all income groups, over half of respondents experienced some level of damage. Fifty-seven percent of households with annual income below $30,000 suffered damages to their homes. This group represents the highest damaged proportion of houses among income categories. When looking at the categories of damage, 28% of households in the lowest income category experienced major or moderate damages compared to 25% among the other two income groups. It is important to note that a quarter of low-income households suffered moderate damages, marking the highest percentage of moderately damaged homes compared to other income categories.

Table 2. Distribution of damage by income categories

| Income Category | No damage | Slight | Moderate | Major | Total Income |

| Below $30K | 26 (42.6%) | 18 (29.5%) | 15 (24.6%) | 2 (3.3%) | 61 (100%) |

| $30K-$50K | 23 (44.2%) | 16 (30.8%) | 8 (15.4%) | 5 (9.6%) | 52 (100%) |

| $50K or more | 26 (46.4%) | 16 (28.6%) | 9 (16.1%) | 5 (8.9%) | 56 (100%) |

| Total Damage | 75 | 50 | 32 | 12 |

Table 3 presents the distribution of income categories across different damage levels. As shown in Table 3, 37% of damaged houses were occupied by households with annual income below $30,000, making it the highest income category among damaged homes. Also, for slight and moderate damages it is clear that the lowest income group had a higher proportion of such damages, 36% and 47%, respectively. In other words, close to half of the houses that suffered moderate damages were occupied by the lowest income group in our sample. This distribution raises concerns about the ability of these low-income households to finance their recovery given their limited resources.

Table 3. Distribution of income by damage categories

| Income Category | All Damage Levels | Slight | Moderate | Major |

| Below $30K | 35 (37.2%) | 18 (36%) | 15 (46.9%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| $30K-$50K | 29 (30.9%) | 16 (32%) | 8 (25%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| $50K or more | 30 (31.9%) | 16 (32%) | 9 (28.1%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| Total Damage | 94 (100%) | 50 (100%) | 32 (100%) | 12 (100%) |

There is also a large variance in destruction faced by households with different forms of housing tenure: renters versus owners versus contract sales (rent-to-own). As exhibited in Table 4, while no renter households surveyed experienced major damages due to the tornado, around 10% still had to deal with moderate damage and 25% with slight damage. The type of housing that experienced the highest percentage of damage is contract sale. With only 25% of these properties taking no damage, compared to 40% of owner-occupied houses and 65% of rental homes, contract sale residents took the highest percentage of moderate and major damages of any residence type. However, this observation should be considered with caution given the small number of contract sale homes in the sample results.

Table 4. Distribution of damage by housing tenure

| No Damage | Slight | Moderate | Major | Total | |

| Contract | 3 (25%) | 3 (25%) | 4 (33%) | 2 (17%) | 12 (100%) |

| Own | 57 (41%) | 40 (29%) | 29 (21%) | 12 (9%) | 138 (100%) |

| Rent | 39 (65%) | 15 (25%) | 6 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 60 (100%) |

Disrupting Impacts of the Tornado

After exploring whether there were differences between damage levels amongst renter and minority households versus the rest of tornado-affected residents, the next step is to examine whether there was a noticeable difference in disruptions in household lives due to the tornado. Based on this research, there appears to be disparities in access to basic utilities by household race and ethnicity.

While similar proportions of non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and the population as a whole lost access to various utilities, these groups regained utilities at different speeds. The most common utilities lost amongst these three groupings were electricity, gas, and internet, although general water as well as safe drinking water and phone service also experienced disruptions in some areas of town. In all cases except for phone service, the average number of days without utility was shorter for the non-Hispanic White population than for the Hispanic portion of Marshalltown.

The largest gaps between regaining access to utilities occurred with internet and gas, both of which had an average six-day wait for non-Hispanic White households compared to eight days without internet access for Hispanic households and an average of a 12 day wait before gas was restored to these residents. Loss of each of these basic utilities causes cascading effects for households affected, impacting and hindering the recovery process. For example, loss of electricity in July would result in food spoilage due to lack of refrigeration and possibly harmful heat effects on household members, especially children and elderly, when faced with hot Iowa temperatures and no air conditioning. Another example of cascading effects is that without internet access, it becomes much harder for individuals to access information regarding resources and aid as well as basic safety procedures in the aftermath of a disaster.

Recovery Resources

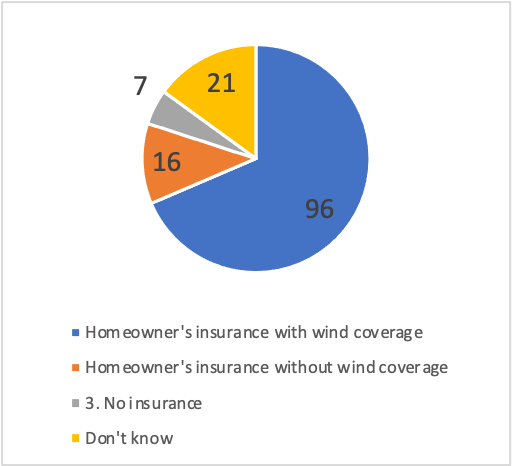

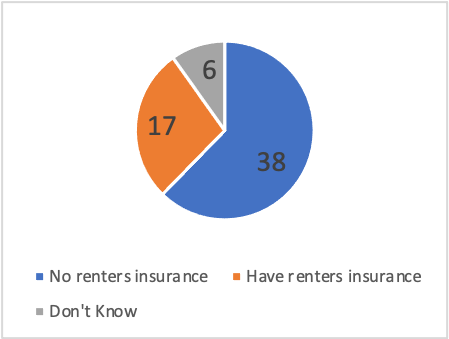

While lack of utilities affects households immediately following a disaster, socially vulnerable groups also faced disparities in the long run with respect to access to recovery resources, particularly insurance. Access to resources is linked to housing tenure type. When analyzing data from the perspective of tenure, the survey results indicated that recovery was disproportionately hindered for renter-occupied households, not due to severity of damage but rather due to lack of insurance. The difference in percentages of owner households with insurance compared to the insurance rate of renter households can be seen in Figures 5 and 6. When surveyed, 9.8% of renters were unsure whether they had renter’s insurance, 62.3% of renters did not have renter’s insurance, and only 27.9% of renters knew that they had insurance. In comparison, only six percent of owner households were unsure of their insurance situation and 80% of owner households knew that they had insurance versus the 14% of owner households without insurance. Since more than 30% of the households surveyed in Marshalltown were renters and 62% of these renters did not have insurance before the tornado, the lack of renter insurance affects a significant percentage of the residents in Marshalltown.

It is important to address the fact that renters have limited control over repairs. Since they do not own the building, their insurance covers belongings rather than the house itself. It is up to the landlord to purchase insurance for the physical building. As these households attempt to repair even slight or moderate damages to their belongings, the lack of insurance will require the homeowners to shoulder all of the rebuilding costs themselves, thereby potentially extending the recovery period or, in more severe cases, resulting in permanent dislocation as families decide it makes more sense financially to move than to wait for the landlord to repair the house. Other costs will be incurred from having to replace renters’ uninsured belongings that were lost in the disaster.

Figure 5. Homeowners Insurance

Figure 6. Renters Insurance

Insurance can also be assessed from the standpoint of race and income. As seen in Table 5, of those surveyed, 64% of non-Hispanic White households reported having homeowner’s or renter’s insurance whereas only 51% of Hispanic households stated they had insurance. When examining insurance by annual income, Table 6 demonstrates that of those surveyed households with an annual income below $30,000, only 54% were insured. In contrast, 72% of households earning $50,000 or more possessed insurance.

Table 5. Distribution of insurance by race-ethnicity

| Race-ethnicity | No insurance | Insured | Don't know | Total Race |

| Not-Hispanic White | 29 (21.48%) | 87 (64.44%) | 19 (14.07%) | 135 (100%) |

| Hispanic | 19 (37.25%) | 26 (50.98%) | 6 (11.76%) | 51 (100%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0 | 1 (16.67%) | 5 (83.33%) | 6 (100%) |

| Other Races | 2 (22.22%) | 4 (44.44%) | 3 (33.33%) | 9 (100%) |

| Two Races | 8 (34.78%) | 12 (52.17%) | 3 (13.04%) | 23 (100%) |

| Total Insurance | 58 | 130 | 36 | 224 |

Table 6. Distribution of insurance by income category

| Income categories | No insurance | Insured | Don't know | Total Income Category |

| Below $30K | 20 (30.77%) | 35 (53.85%) | 10 (15.38%) | 65 (100%) |

| $30K-$50K | 14 (25.93%) | 36 (66.67%) | 4 (7.41%) | 54 (100%) |

| $50K or more | 10 (17.54%) | 41 (71.93%) | 6 (10.53%) | 57 (100%) |

| Totoal Insurance | 44 | 112 | 20 | 176 |

The socially vulnerable lower income population of Marshalltown seems to have less access and thus will likely receive fewer resources via insurance than those in higher income brackets, an indication of which groups are more likely to have insurance as well as those more likely to know the process or have the resources to file insurance claims. It is important to note that several of the lower income households with insurance had no savings and consequently were facing difficulties in paying the deductible to receive their insurance payout and start repairs after the tornado. This observation highlights the complex challenges of low-income households in accessing recovery resources even when they insure their properties.

Beyond insurance, few other types of aid were available for household recovery at the time of this study. Of everyone surveyed, there was one household that reported receiving tribal aid, one household that reported receiving aid from the U.S. Army, and one that received funds according to their refugee status. Additionally, two households reported receiving low-interest Small Business Administration (SBA) home repair loans from the government. Ability to repay is one of the eligibility criteria for SBA loans and it is not surprising that most low-moderate income affected households in Marshalltown have not qualified for such loans. The dearth of governmental aid for individual households can be attributed to the fact that the federal government denied the request for individual assistance following the tornado and thus did not open FEMA’s Individual Assistance national disaster recovery funds to Marshalltown households.

Lastly, eight households surveyed reported receiving financial aid in the form of grants, loans, or gifts from non-governmental organizations, particularly Mid-Iowa Community Action (MICA), family members, and church or faith-based organizations. These findings should be considered with the timeline of the data collection in mind. Given the early stages of recovery when survey data collection occurred, it is expected that more households have applied for local non-governmental assistance, especially the through Region 6 Housing Trust Fund, MICA, and faith-based organizations in town. For the most part, at the time this survey was conducted, many of the uninsured Marshalltown households were looking for resources to fund their repairs.

Application and Next Steps

This study collected perishable data from households who were affected by a tornado that received limited attention and resources and therefore left many of them with challenges in accessing necessary resources. To complete repairs before winter, many households had to either start fixing homes on their own; seek assistance from friends or family in the form of labor; or look for other housing options in the month or two after the tornado. Since the tornado happened in July, homeowners had only a couple of warm months to complete repairs. But without insurance and long waitlists for trusted contractors, many were left slowly repairing damages on their own or with the help from family and friends. Temporary fixes, such as tarps on roofs and plastic on windows or cracks in the walls, made it hard to keep the cold out or withstand the snow and rain, causing additional damages to some of the tornado-affected homes.

Recovery challenges faced in Marshalltown—such as concentration of damages in low-income neighborhoods with a high proportion of uninsured houses, limited government assistance, and low capacity to provide affordable housing within the community—resulted in disproportionate impacts on vulnerable households and may lead to overall population loss for the community in the long run, given the deferred repairs and demolition decisions being made by the city and some homeowners. These challenges, which may be present in other smaller disaster-prone towns, further highlight the need for studies that seek to examine specific weak points in recovery.

Given limited resources for rental housing, this research can inform development of programs by state and local governmental and non-governmental organizations to better address the needs resulting after disasters from an intersection of vulnerability factors. For example, some low-income residents with homeowner’s insurance were still struggling to start their repairs due to their lack of savings to pay insurance deductibles. Assistance can be targeted towards these households that need a small and quick lift to access the larger sums of insurance payout they are entitled to. This study has also found that the assistance process and dedicated resources often results in a mismatch between what is available, to whom, and when. By providing construction safety training and material to uninsured and underinsured households, tornado recovery can be accelerated through drawing upon both community and volunteer organizations.

After cataloging damages and the beginning of recovery efforts, the next step is to collect perishable data from households who are going through the process of repairing or reconstructing their homes. As the weather got colder, temporary fixes such as tarps on roofs and plastic on windows or cracks in the walls fail to keep the cold out or withstand snow and rain. Therefore, it was important to interview the households experiencing these challenges as they move forward in repairs and perhaps consider different options for permanent housing. These immediate decisions have long-term consequences for the speed of recovery and ultimate physical form of the community (Hack, 2006). The next phase of this study entails a qualitative case study consisting of in-depth accounts of life disruption, recovery experiences, and risk of long-term displacement among immigrant and non-homeowner households in Marshalltown. Given the observations we made during survey work two months after the tornado in Marshalltown, it is crucial to capture the voices of understudied and underserved groups like renters and immigrants after disasters to better address their needs and support their recovery efforts.

References

-

Hamideh, S., Peacock, W. G., & Van Zandt, S. (2018). Housing Recovery after Disasters: Primary versus Seasonal and Vacation Housing Markets in Coastal Communities. Natural Hazards Review, 19(2), 04018003. doi:10.1061/%28ASCE%29NH.1527-6996.0000287 ↩

-

Peacock, W. G., Van Zandt, S., Zhang, Y., and Highfield, W. (2014). “Inequities in long-term housing recovery after disasters.” Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(4), 356–371. ↩

-

Zhang, Y., Peacock, W., G., (2010). Planning for Housing Recovery? Lessons Learned from Hurricane Andrew. Journal of the American Planning Association. 76(1). ↩

-

Cutter, S. L., Schumann III, R. L., & Emrich, C. T. (2014). Exposure, social vulnerability and recovery disparities in New Jersey after Hurricane Sandy.* Journal of Extreme Events, 1*(01), 1450002 ↩

-

Van Zandt, S., Peacock, W. G., Henry, D. W., Grover, H., Highfield, W. E., & Brody, S. D. (2012). Mapping social vulnerability to enhance housing and neighborhood resilience. Housing Policy Debate, 22(1), 29-55. ↩

-

Van de Lindt, J.W., Peacock, W. G. Tobin, J., Mitrani-Reiser, J., Koliou, M., Deniz, D., Rosenheim, N. Gu, D., Peek, L., Dillard, M., Sutley, E., Hamideh, S., Graettinger, A., Crawford, S., Coulbourne, B., Tomiczek, T., Memari, M., & Barbosa, A. (2018) The Lumberton, North Carolina Flood of 2016: A Community Resilience Focused Technical Investigation. October 2018 ↩

-

Mitchell, C.M., Esnard, A. M., & Sapat, A., (2012). Hurricane Events, Population Displacement, and Sheltering Provision in the United States. Natural Hazards Review, 13(2): 150-161 ↩

-

Fothergill, A. & Peek, L. (2015). Children of Katrina. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. Region 6 Resource Partners. MARSHALLTOWN OWNER-OCCUPIED HOUSING IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM https://www.region6resources.org/marshalltown-cdbg/ ↩

-

Van de Lindt, J. W., Peacock, W. G., Mitrani-Reiser, J., Rosenheim, N., Deniz, D., Dillard, M., ... & Harrison, K. (2020). Community Resilience-Focused Technical Investigation of the 2016 Lumberton, North Carolina, Flood: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Natural Hazards Review, 21(3), 04020029. doi: 10.1061/%28ASCE%29NH.1527-6996.0000387 ↩

-

Hack, G. (2006). Temporary Housing Blues. In Birch E. L. & Wachter S. M. (Eds.), Rebuilding Urban Places after Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina (pp. 230-243). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ↩

-

Oliver-Smith, A., (2005). Communities after Catastrophe: Reconstructing the Material, Reconstituting the Social. In Stanley Hyland (Ed.) Community Building in the 21st Century. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. ↩

-

Burby, R. J. (2006). Hurricane Katrina and the paradoxes of government disaster policy: Bringing about wise governmental decisions for hazardous areas. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 604(1), 171-191 ↩

-

Dash, N., & Gladwin, H. (2007). Evacuation decision making and behavioral responses: Individual and household. Natural Hazards Review, 8(3), 69-77. ↩

-

Johnson, L. A., & Olshansky, R. B. (2017). After great disasters: An in-depth analysis of how six countries managed community recovery. Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. ↩

-

Comerio, M. C. (1998). Disaster hits home: New Policy for Urban Housing Recovery. University of California Press. ↩

-

Hamideh, S., & Rongerude, J. (2018). Social Vulnerability and Representation in Recovery Decisions: Public Housing Recovery in Galveston, Texas following Hurricane Ike. Natural Hazards. DOI: 10.1007/s11069-018-3371-3 ↩

-

Olshansky, R. B., & Johnson, L. A. (2014). The Evolution of The Federal Role in Supporting Community Recovery After US Disasters. Journal of the American Planning Association, 804), 293-304. doi:10.1080/01944363.2014.967710 ↩

-

Beers, N. (2017, June 22). Tackling the Midwest's Low Attention, High Cost Disasters. Center for Disaster Philanthropy. https://disasterphilanthropy.org/blog/tornadoes/tackling-midwests-low-attention-high-cost-disasters/ ↩

-

Mochizuki, J., Mechler, R., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Keating, A., Williges, K. (2014). Revisiting the ‘disaster and development’ debate – Toward a broader understanding of macroeconomic risk and resilience. Climate Risk Management, Volume 3, Pages 39-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2014.05.002 ↩

-

Fothergill, A., Maestas, E. G., & Darlington, J. D. (1999). Race, ethnicity and disasters in the United States: A review of the literature. Disasters, 23(2), 156-173. ↩

-

Weil, J. H. (2009). Finding Housing: Discrimination and Exploitation of Latinos in the Post-Katrina Rental Market. Organization & Environment, Vol. 22, No. 4, Special Issue on the Social Organization of Demographic Responses to Disaster: Studying Population-Environment Interactions in the Case of Hurricane Katrina, pp. 491-502 ↩

-

Nguyen, M., & Salvesen, D. (2014). Disaster recovery among multiethnic immigrants. Journal of the American Planning Association, Volume 80, 385–396. ↩

-

Donahey, M. (2018, July 20). City’s Largest Employers Hit Hard. Times Republican. https://www.timesrepublican.com/news/todays-news/2018/07/citys-largest-employers-hit-hard/ ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau, 2013-2017. (2019, October 05). American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Marshalltown. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Marshalltown%20city,%20Iowa&g=1600000US1949755&tid=ACSDP5Y2019.DP05&hidePreview=false ↩

-

Iowa Public Broadcasting Service. (2017, March 08). Tornadoes. http://www.iptv.org/iowapathways/mypath/tornadoes ↩

-

U.S. Department of Commerce, & NOAA. (2019, June 19). 2018 Iowa Tornadoes. https://www.weather.gov/dmx/iators2018 ↩

-

U.S. Department of Commerce, & NOAA. (2018, August 22). July 19, 2018 Tornadoes - Bondurant, Marshalltown, Pella. https://www.weather.gov/dmx/20180719_Tornadoes ↩

-

Sodders, A. (2018, September 28). Gov. Reynolds appeals FEMA Individual Assistance Denial. Times Republican. https://www.timesrepublican.com/news/todays-news/2018/09/gov-reynolds-appeals-fema-assistance-denial/ ↩

Hamideh, S., Freeman, M., Sritharan, S., & Wolseth, J. (2021). Damage, Dislocation, and Displacement after Low-Attention Disasters: Experiences of Renter and Immigrant Households (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 304). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/damage-dislocation-and-displacement-after-low-attention-disasters