Food, Energy, and Water Security in Colorado During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Publication Date: 2020

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted nearly every facet of global society, creating fiscal uncertainties for households around the world. In this project, we seek to assess the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and related regulatory measures (e.g., lockdown orders, quarantining) on the food, energy, and water security of households. We focus on the state of Colorado. The first step of our project—which is nearly complete—includes a social media-based survey of Colorado residents to understand how the pandemic and economic fallout affected the food, energy, and water security of their households. For the next step, we propose to conduct a survey of local governments in Colorado to understand the impacts of—and possible ameliorative policies for—COVID-19.

Introduction

In late 2019, a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in Wuhan, China that caused acute respiratory symptoms in humans (hereafter “COVID-19”). By early 2020, the virus had spread to 114 countries. As of the writing of this article, over half a million people have died from the global pandemic and cases are rising in the United States and Brazil, even as other nations are seeing their infection rates fall.

Governments have a range of options to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Governments can conduct informational campaigns to inform the public of the severity and extent of COVID-19 and encourage voluntary practices to mitigate the spread of the virus, such as mask-wearing, handwashing, and social distancing. Some governments around the world have taken more aggressive measures like mandating face masks in public spaces and enforcing social distancing. Indeed, in the early stages of the pandemic, many governments instituted shut-down orders, effectively closing many places of employment deemed non-essential. In the U.S., unemployment spiked after the lockdown orders, raising concerns about how the pandemic and policy response would impact households, especially low-income families.

Families of low socio-economic status often find that they must make difficult “heat or eat” tradeoffs, typically prioritizing caloric intake over adequate thermal comfort (Frank et al. 20061; Nord &Kantor 20062). Household energy security is associated with increased hospitalization, lower self-rated health, developmental challenges in children, asthma, poor sleep, and pneumonia (Cook et al. 20083; Hernandez & Siegel 20194). Children in homes struggling with food and energy security exhibit more problematic behaviors (Fernandez et al. 20185). This association between food insecurity and energy insecurity has also been observed outside the U.S. (Emery et al. 20126; LaCroix & Jusot 20147; LaCroix & Chaton 20158; Healy 20039; Harrington et al. 200510).

The pandemic and policy responses (e.g. shutdown order and quarantining) may exacerbate these inequalities. Households that were already struggling with utility bills will likely see those bills increase because of the increase in the time they must spend at home. This, coupled with millions of job losses that are already occurring, will likely create a scenario where millions more households face “heat or eat” dilemmas. We aim to uncover where the most vulnerable households are in terms of likelihood of experiencing energy-insecurity related vulnerabilities in the context of coronavirus, what intersecting variables may exacerbate these vulnerabilities, and what type of changes in patterns of energy use are taking place at the household level in real time as a result of the stay-at-home and shelter-in-place risk mitigation efforts that are underway.

In this report we will provide preliminary findings of our quick Response research that examines the food, energy, and water security implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for households in Colorado.

Research Design

Phase 1: Social Media Survey

We chose to target the state of Colorado, which has several advantages as a site for this research. Politically, Colorado has historically been a “swing state” with significant numbers of both Republicans and Democrats. This is advantageous given that attitudes and behaviors around COVID-19 appear to be exhibit some degree of partisan polarization (Green et al. 202011; Gardarian et al. 202012). Further, Colorado has a great deal of topographical and demographic variability. The state’s population is concentrated in the Denver metropolitan region east of the Rocky Mountains. Yet, Colorado also has rural counties centered on farming, mining, and industrial agriculture as well as regions rich in natural resources with economies driven by tourism and recreation.

We collected data from April 2020 to July 2020. We targeted geographically specific groups and forums related to Colorado. These include subreddits on www.reddit.com, including many subreddits for rural communities; Nextdoor.com; Facebook; and Instagram. The survey took an average of six minutes for respondents to complete. Respondents were screened for residence in Colorado and age (over 18). Three-hundred sixteen respondents passed the initial screening and 228 completed the survey, for a completion rate of 72 percent. Among those who did not complete the survey, the vast majority quit after the initial screening questions. We also checked for unusually rapid completion times (e.g., under a few minutes) but did not find any. Online convenience data such as ours is especially useful for preliminary analysis of new topics, such as the food, water, and energy security impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The survey included a series of questions to capture respondents’ experiences with food, water, and energy security, as well as standard socio-demographics. We adapted the energy security questions used by Cook et al. (2008) to understand both water and energy security. For food security, we employed the well-validated set of questions developed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service.

Collecting data via social media platforms is especially appropriate on new and emerging topics and for preliminary analyses. Still, we acknowledge that this form of data collection has key limitations and caveats. First, our data may exclude households that do not have internet access. However, some 88 percent of Colorado residents have internet access. Not surprisingly, our sample does not neatly track Colorado demographics. Following the guidance of Pew (201813), we re-weighted our data to state demographics. We calculated weights using the ebalance command in Stata 15/IC to weight our data according to the state’s distribution of college graduates, people who identify as male sex, and race. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Colorado State University.

Preliminary Findings for Phase 1

Descriptive Results

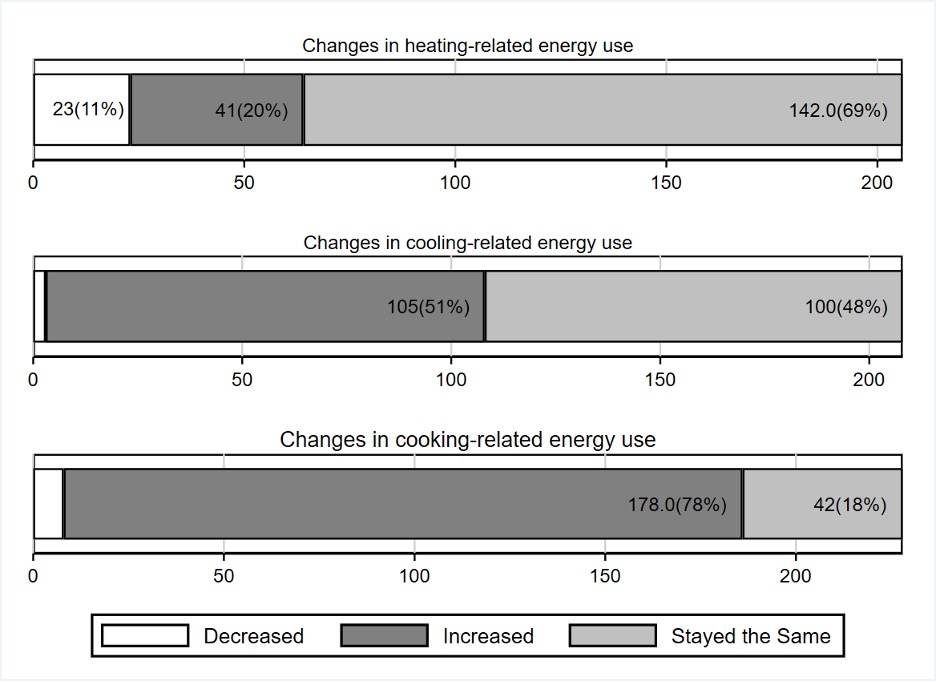

Figure 1 displays the results of a series of questions that asked about increased household expenditures for heating, cooling, and cooking since the start of the pandemic. A majority of respondents—69 percent—indicated that heating expenditures had stayed the same, though this result may be an artifact of the timing of the spread of COVID-19 in Colorado, which began in earnest in April 2020 and into the summer months. Heat may not have been necessary during this period. However, a slight majority (51 percent) indicated that cooling-related energy use had increased, and very few (3 percent) indicated that it had decreased. Finally, 78 percent indicated that they were using more energy for cooking at home. Thus, the respondents in our sample indicated that their household energy use had increased.

Figure 1. Changes in energy use since the beginning of the quarantine.

Table 1 displays the results of the energy security questions adapted from Cook et al. (2008). These questions document direct experiences with energy security before the pandemic and lockdown orders (that is, the 3 years before March 2020) and since March 2020. In general, respondents reported very few changes from the previous year. For instance, only 2.6 percent of respondents indicated that their home did not have heating or cooling in the three years before the pandemic, and the same figure post-pandemic is 2.2 percent.

Table 1. Experiences with energy insecurity before and after pandemic.

| An energy or utility company shut-off your power for lack of payment. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 223 | 97.3% | 229 | 100% |

| Yes | 6 | 2.6% | - | - |

| An energy or utility company threatened to shut off your power for lack of payment. | ||||

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 213 | 93% | 221 | 96.5% |

| Yes | 16 | 6.9% | 8 | 3.5% |

| You used a cooking stove to heat your home. | ||||

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 223 | 96.5% | 218 | 96% |

| Yes | 8 | 3.5% | 9 | 3.9% |

| You used a cooking stove to heat your home. | ||||

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 223 | 97.3% | 211 | 97.8% |

| Yes | 6 | 2.6% | 5 | 2.2% |

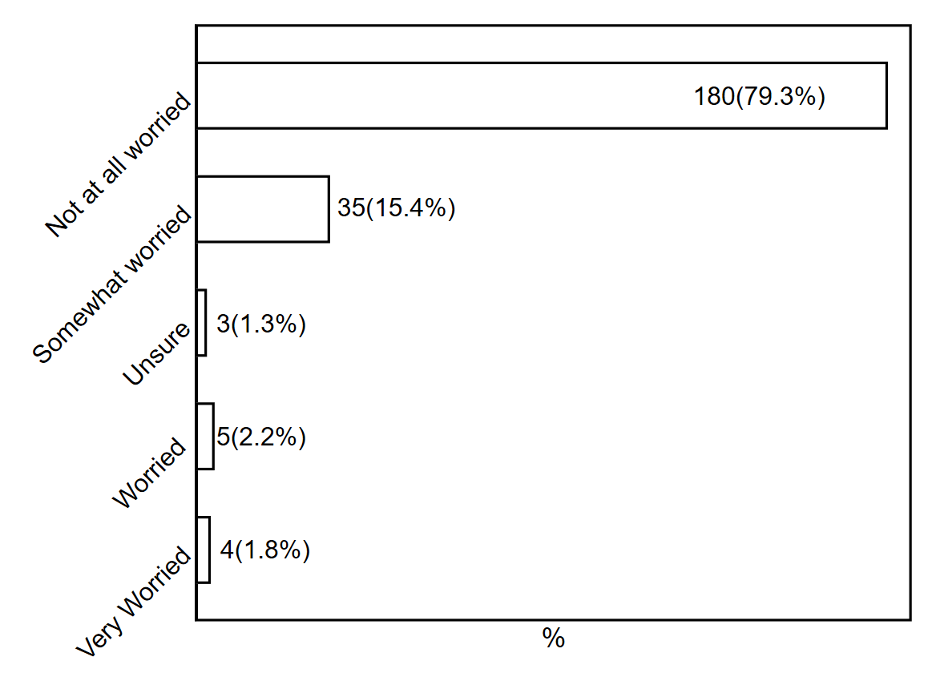

Finally, we asked respondents how worried they were that they would not be able to pay their energy bills in the next year. As shown in Figure 2, nearly 80 percent of respondents indicated that they were “not at all worried” about their ability to pay energy bills, while 15 percent stated “somewhat worried”.

Figure 2. Worry about paying energy bills.

Water Security

Table 2 displays the results for our water security questions, which again were adapted from the energy security questions of Cook et al. (2008). In general, the results imply few changes from pre- and post-pandemic.

Table 2. Experiences with water security before and after the pandemic.

| A water company shut-off your water for lack of payment. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 226 | 100% | 226 | 100% |

| Yes | - | - | - | - |

| A water company threatened to shut off your water for lack of payment. | ||||

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 222 | 98% | 224 | 99% |

| Yes | 4 | 2% | 2 | 1% |

| Were there any days you did not use the water you needed to save money? | ||||

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 221 | 97% | 217 | 96% |

| Yes | 6 | 3% | 10 | 4% |

Food Security

Table 3 provides the distribution of the food security items adapted from the USDA’s validated food security inventory. The descriptive results imply that relatively few respondents experienced greater food insecurity because of the coronavirus pandemic. For instance, 13 percent indicated that before the pandemic they cut the size of their meals because there was not enough money for food. After the pandemic, this figure rose to 17 percent. Other figures show little to no change.

Table 3. Experiences with food security before and after pandemic.

| Did you or any other adults in your household ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn't enough money for food? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 202 | 87% | 192 | 83% |

| Yes | 29 | 13% | 38 | 17% |

| A water company threatened to shut off your water for lack of payment. | ||||

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 195 | 85% | 193 | 84% |

| Yes | 35 | 15% | 38 | 16% |

| Were there any days you did not use the water you needed to save money? | ||||

| Before the pandemic | After the pandemic | |||

| No | 204 | 89% | 207 | 90% |

| Yes | 26 | 11% | 24 | 10% |

Self-described household impacts of Coronavirus

In an open-ended question, survey respondents were asked to self-report what their main concerns were about how their households might be impacted by coronavirus. These responses provide more clarity about Coloradoans’ concerns that are not easily captured with survey data, chief of which were economic issues. Despite the lack of evidence of concern over access and affordability of food, water, and home energy, participants reported being concerned about potential job losses and cuts in wages. The second biggest concern was related to potential health risks, including mental health issues stemming from social isolation. Some survey respondents identified concerns at the intersection of health, health insurance, and economic wellbeing:

I'm concerned about healthcare coverage. I have bare minimum coverage through the VA so I don't know what I'll do if I need care beyond what a general practitioner can provide. Even with the reduced income or if I wasn't working, we make too much for me to qualify for Medicaid. It wasn't the plan for this year, but my lack of coverage wasn't discovered until after it was too late to get coverage through my spouse's employer. I'm in a higher risk category so it stresses me daily, especially now that the number of new cases is on the rise again.

Should we lose our health insurance due to lay off I will be unable to afford the medication that literally keeps me alive (insulin). My prescription without insurances exceed $2500 per month for all the supplies that work with insulin to keep me alive.

[Fear of being] evicted due to non-payment of rent. Husband and I are both immunocompromised and I have severe mental health issues that would be greatly imbalanced due to eviction.

I lost my second part-time job at the start of the pandemic but returned to that job 3 weeks ago. The owners of the bar do not follow health department guidelines, and I fear it will contribute to another outbreak, or I'll get sick, or the bar will be shut down. It is stressful. My husband also lost his job just after stay at home orders went into effect. Luckily, I still had my full-time day job, and he was able to find a new position within 3 weeks, earning more than he was before.

While some survey respondents suggested that they had concerns about missing out on social gatherings, events, day-to-day activities, celebrations, and the ability to travel, others suggested that in some ways the pandemic had a positive impact on their household:

Honestly the Coronavirus helped our family because it changed legislation that allowed me to actually get unemployment. I got laid off just before the pandemic and had an adjunct position. We ended up moving three times since February and I still live on that poverty line.

Having severe epilepsy has kept me homebound most of my life - I've been on SSDI and did not lose a job. The stimulus payment allowed me to pay off some debt.

I got a new job as an essential worker that pays approximately double what my old job did.

On top of my FT job I started a business related to Coronavirus and it has taken off.

The magnitude of this event, however, cannot be understated. This is exemplified by one survey respondent who highlights both the positives of the pandemic on their household, while simultaneously noting the severity of the potential consequences:

Has been sort of a blessing. I spend more time with my son instead of working 60 hours a week to stay afloat. Very concerned my immunocompromised spouse will catch COVID and die.

Another respondent further elaborates on the interconnections of the complexity of their fears of potential immediate and long-term negative impacts of Coronavirus on their household:

We are ok because we were planning for no running water, electricity, grocery stores, [and] working toward energy and food sovereignty. [We are] worried about 2 deaths in the apartment complex - exposure from unmasked/not concerned community members. Concern about lack of access to garden space to grow food with upcoming shortages.

Conclusion

The U.S. is currently the global epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is a nation with a comparatively weak welfare state, expensive healthcare, and little end in sight for the global pandemic. Given this environment, it is likely that COVID-19 and the policy response will engender significant hardships for households. We provided a preliminary investigation of the food, water, and energy security implications of the current pandemic using an opt-in social media survey hosted on several websites.

Our results have some sanguine implications, especially given the economic challenges posed by COVID-19. Our respondents reported some concerns about energy security, but overall we found little evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown orders caused extremely deleterious energy, food, or water security for Colorado residents. Respondents did not report threatened shutoffs from utility or water companies or increased hunger during the pandemic, although a non-trivial minority voiced concerns about being able to pay their utility bills. Still, respondents reported high levels of concern about the potential economic and health risks faced by their households, suggesting that households may currently be worried about other economic stressors, such as losing employment or taking pay cuts. If that happens, we would expect to see increased concern for household capability to afford food, water, and energy.

Our conclusion comes with several important caveats. First, our survey data was collected in the first few months of the pandemic. It is likely that struggling households engaged in several unconventional strategies to avoid food, water, and energy insecurity. Households may have drawn from savings or retirement accounts, increased credit card debt, refinanced their homes, sold other assets, taken in family members or roommates, or pursued other strategies to ensure access to food, water, and energy. Some of these strategies may not be fiscally sustainable for households in the long run. In other words, we suggest that our findings should not be interpreted as evidence that the pandemic has had no effect on households—rather, Colorado residents appear to be relatively resilient thus far. Second, we recognize that internet-based surveys are unlikely to access households who lack internet access, and are also unlikely to reach the most vulnerable populations in Colorado—including those who are currently homeless and likely to be impacted by Coronavirus. Given the use of a convenience sample, we expected that households’ income levels might skew toward those who live well above the poverty line and thus are not as likely to struggle with access or affordability at the food-energy-water nexus.

As noted earlier, we view this study as a preliminary investigation into a significant and deeply salient issue. The current work points to ample future research needs. We suggest that longitudinal and qualitative research can help understand household adaptive strategies—for instance, do households incur debt to stave off food, energy, and water insecurity during hard times? Such an analysis might allow scholars to develop a more sophisticated understanding of food, energy, and water insecurity as a process that unfolds over time. Further, we don’t know the extent to which households relied upon charities, government programs, family, friends, or neighbors to bolster their household finances during the pandemic; these could have been key ways that households avoided food, water, and energy insecurity. These, and many other questions, provide ample space for future research that we hope to extend in the second round of this study.

Future Direction

Phase 2: Local Government Survey

The second phase of this project is a survey among local governments to understand how COVID-19 is impacting their provision of food, energy, and water and other effects of the pandemic and policy responses (e.g., quarantine and lockdown orders). We are also interested in learning how the pandemic has impacted local services, especially to vulnerable populations, and the fiscal outlook of local governments.

We will distribute this survey via the Qualtrics platform via emails to local government leaders. We have collected some 4,500 email contacts from city and county governments in the state of Colorado. Additional support from the NHC will allow us to complete this critical phase of the project.

References

-

Frank, D. A., Neault, N. B., Skalicky, A., Cook, J. T., Wilson, J. D., Levenson, S., Meyers, A. F., Heeren, T., Cutts, D. B., & Casey, P. H. (2006). Heat or eat: The Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program and nutritional and health risks among children less than 3 years of age. Pediatrics, 118(5), e1293–e1302. ↩

-

Nord, M., & Kantor, L. S. (2006). Seasonal variation in food insecurity is associated with heating and cooling costs among low-income elderly Americans. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(11), 2939–2944. ↩

-

Cook, J. T., Frank, D. A., Casey, P. H., Rose-Jacobs, R., Black, M. M., Chilton, M., Ettinger deCuba, S., Appugliese, D., Coleman, S., & Heeren, T. (2008). A brief indicator of household energy security: Associations with food security, child health, and child development in US infants and toddlers. Pediatrics, 122(4), e867–e875. ↩

-

Hernández, D., & Siegel, E. (2019). Energy insecurity and its ill health effects: A community perspective on the energy-health nexus in New York City. Energy Research & Social Science, 47, 78–83. ↩

-

Fernández, C. R., Yomogida, M., Aratani, Y., & Hernández, D. (2018). Dual food and energy hardship and associated child behavior problems. Academic Pediatrics, 18(8), 889-896. ↩

-

Emery, J. H., Bartoo, A. C., Matheson, J., Ferrer, A., Kirkpatrick, S. I., Tarasuk, V., & McIntyre, L. (2012). Evidence of the association between household food insecurity and heating cost inflation in Canada, 1998–2001. Canadian Public Policy, 38(2), 181-215. ↩

-

Lacroix, E., & Jusot, F. (2014). Fuel Poverty is it harmful for health? Evidence from French health survey data. ↩

-

Lacroix, E., & Chaton, C. (2015). Fuel poverty as a major determinant of perceived health: The case of France. Public Health, 129(5), 517–524. ↩

-

Healy, J. D. (2003). Excess winter mortality in Europe: a cross country analysis identifying key risk factors. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 57(10), 784-789. ↩

-

Harrington, B. E., Heyman, B., Merleau-Ponty, N., Stockton, H., Ritchie, N., & Heyman, A. (2005). Keeping warm and staying well: Findings from the qualitative arm of the Warm Homes Project. Health & Social Care in the Community, 13(3), 259–267. ↩

-

Green, J., Edgerton, J., Naftel, D., Shoub, K., & Cranmer, S. J. (2020). Elusive consensus: Polarization in elite communication on the COVID-19 pandemic. Science Advances, 6(28), eabc2717. ↩

-

Kushner Gadarian, S., Goodman, S. W., & Pepinsky, T. B. (2020). Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Behavior, and Policy Attitudes in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic (March 27, 2020). ↩

-

Pew. (2018). Weighting in online opt-in surveys. Retrieved March 6, 2020 from https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/2018/01/26/for-weighting-online-opt-in-samples-what-matters-most ↩

Meyer, A., Ryder, S. & Dickie, J. (2020). Food, Energy, and Water Security in Colorado During the Coronavirus Pandemic (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 309). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/food-energy-and-water-security-in-colorado-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic