Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Parental Stress and Young Children’s Development During Physical Distancing

Publication Date: 2020

Abstract

Recent reports acknowledge the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on family routines and dynamics, but less is known about how it has impacted on parent’s psychological wellbeing. Families can experience disproportionate impacts related to their socioeconomic and ethnic background. This study investigated the potential parental stress risk factors of the parents of young children’s parents, with consideration of socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. Using an online survey method, we recruited 212 parents of preschool age children in early May 2020. The survey collected information on families’ direct exposure to COVID-19, exposure in their communities, the amount of time they spent physical distancing time at home, home activities, and the availability of teacher support. Parental stress was captured by using Parental Stress Index-Short Form, which includes three dimensions of stress: parental distress, parent-child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child behavior. Our findings suggested significant increases in all dimensions of parental stress during the pandemic thus far. Based on respondent’s Parental Stress Index scores, close to 50 percent of parents can be considered clinically depressed. Minority parents perceived significantly higher levels of stress in all index domains than white parents did, and minority parent stress increased more significantly during the pandemic than did white parents. Regression analyses suggest that educational level was a protective factor in parental stress during the pandemic. Mothers perceived higher stress related to children’s behavioral and emotional problems than fathers did. Parents from higher-income families reported higher stress related to general emotional state and parent-child interactions than those of lower-income families. Family exposure to COVID-19 did not show significant association with parental stress in the dimensions of parental distress and difficult child behavior but had significant inverse association with parent-child dysfunctional interactions. The length of social-distancing time showed marginal inverse association with difficult child behavior. At the same time, parent-perceived impacts on family interactions was significantly associated with all domains of parental stress. These findings suggest the existence of family resilience during the pandemic and the successful efforts of parents in buffering pandemic impact to their children. Teacher support also showed significant association with increasing parental stress, specifically related to parent-perceived child behavioral or emotional difficulties. This finding highlights the need to review the effectiveness of professional support to parents during pandemics. Professional support can overwhelm parents if it does not consider parent’s needs. This study revealed the necessity of implementing trauma-informed approaches when providing remote support to families.

Introduction

Since the earliest official report of the coronavirus disease epidemic (COVID-19) in early January 2020, COVID-19 has quickly spread internationally. By March 2020, all U.S. states issued varying levels of public health emergency and stay-at-home orders that limit regular public social gathering amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Families were urged to enact “physical distancing” by staying at home and limiting unnecessary social interaction (Stokes et al., 20201). The latest reports from various countries indicated similar concerns about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on all aspects of family life, including parental burnout and child maltreatment (Griffith, 20202), children’s psychological development (Brook et al., 20203), and physical wellbeing, mental health, and productivity of both children and parents (Wang et al., 20204). Parents with children from newborns to five years old may experience additional stress, as childcare services are not part of “formal schooling,” and early childhood teachers are not required to provide remote instruction (e.g., online courses) as are teachers of older children. Parents with young children may lack professional guidance for childcare and education, which may lead, under the current circumstances, to parents changing their parenting practices and to parental stress. In order to investigate the pandemic impact specifically on families with young children, this study utilized an online survey to examine the relationship between family experience during the pandemic (i.e., exposure to COVID-19, physical distancing time) and parents’ perceived parental stress during the pandemic.

Parental Stress and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Existing studies have consistently shown that parental stress—the negative feelings that parents have toward themselves and toward their children due to a mismatch between perceived resources and the demands of their parenting roles—has a great impact on the quality of the parent-child relationship (Deater-Deckard, 19985; Morgan et al., 20026). Although parental stress is a normative part of parenting (Crnic & Greenberg, 19907), parents with high parental stress are prone to engage in dysfunctional parenting practices, which can lead to children’s deviant behaviors (Abidin, 19958); disadvantaged psychological functioning (Kolbuck et al., 20199); and challenging neurobiological development, such as reduced hippocampus volume (Blankenship et al., 201810).

Parental stress is a function of parents’ personal characteristics (e.g., sense of parenting competence), children’s characteristics (e.g., demandingness), and stressful or traumatic events (e.g., Abidin, 199211). Research has suggested that traumatic events usually influence young children’s well-being through parental stress (Whitson & Kaufman, 201712). For example, Halevi et al. (201713) found that, for a family who is living in a war zone, exposure to adversity influences child psychopathology through maternal stress and well-being. With increasing parental stress related to the adversities and challenges from a trauma event, parent-child conflicts increase, which may lead to emotional or behavioral problems in children (Garcia et al., 201714). Instead of treating parenting stress as a unidimensional concept (Farver et al., 200615), this study employed Abidin’s (1995) stress model and captured parents’ stress related to general emotional well-being (i.e., parental distress); negative interaction with children (i.e., parent-child dysfunctional interaction); and children’s emotional or behavioral difficulties (i.e., difficult child). By examining the relations between family pandemic experience, home learning experience, and different dimensions of parental stress, the impact of the pandemic on family well-being and the parent-child relationship can be revealed (Prime et al., 202016).

This study examined the pandemic’s impact on parental stress while taking into consideration the family’s level of exposure to the pandemic. Literature in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) suggests that the prevalence of PTSD is associated with the level of exposure to a disaster. For example, the victim of a disaster tends to have more severe PTSD than rescue workers and first responders (e.g., Neria et al., 200817). From this perspective, parents who were directly exposed to COVID-19, similar to “victims” of a disaster, may experience increased stress, while parents who were indirectly exposed to COVID-19 (e.g., knowing of a confirmed diagnosis in their neighborhood or social network) may experience stress at a lower level. Thus, in this study, we differentiated between family direct exposure and family community exposure to COVID-19 and examined whether different levels of exposure are related to parent-reported stress.

A unique characteristic of the COVID-19 pandemic that sets it apart from other types of natural disaster, such as earthquake and hurricane, is the prolonged physical distancing quarantine time. Brooks et al. (2020) reported that post-traumatic stress symptoms occur in 28 percent to 34 percent and fear in 20 percent of subjects in quarantine. In a study conducted after similar public health pandemics—H1N1 and SARS—researchers noticed that 30 percent of children who had been isolated or quarantined showed PTSD symptoms based on parents’ reports (Sprang & Silman, 201318). Thus, this study took the length of family physical distancing quarantine into account when examining the associations between family exposure to the pandemic and parents’ stress.

Families may experience different levels of COVID-19 impact due to their socioeconomic status (SES) and available social support. For example, low-SES parents are especially susceptible to experiencing stress (Ladwig et al., 200119) related to their income and neighborhood conditions compared with parents from middle- and high-income backgrounds (Raikes & Thompson, 200520). Parents of different ethnic backgrounds also may respond to stress and interactions with children differently during the pandemic. For example, Garcia et al. (2017) found that although a traumatic event may lead to parent-child conflict through parental stress, such conflict is generally associated with children’s behavioral problems only among parents born in the United States and not among immigrant parents. In a recent study, Driver and Amin (201921) found that Hispanic mothers (both foreign-born and native-born) tend to have significantly lower levels of parental stress as compared to African-American mothers, and their parental stress is related to the level of their acculturation and the availability of social support.

Research Questions

Specific research questions addressed in this study are:

- What were parents’ experiences during the pandemic?

- What was the nature of the home learning environment during the pandemic?

- What were the pandemic’s impact on parents’ stress when taking into consideration family SES, ethnic background, family’s level of exposure to COVID-19, and physical distancing time?

Method

Participants

In May 2020, researchers recruited participants through Facebook and Twitter. The participating parents signed an online consent form before proceeding to the online questionnaire. The questionnaire could be accessed via computer or smartphone. A total of 212 (73 percent female) parents gave consent and completed the online questionnaire. The participants were from all continental states (12 percent from the Northeast, 13 percent from the Midwest, 36 percent from the South, and 39 percent from the West). The participants also had diverse ethnic backgrounds (55.7 percent Caucasian and 45.3 percent Non-white minorities). The majority of the participants (80.2 percent) had a college degree or higher. About 64.5 percent of parents indicated an annual family income higher than $75,000.

Measures

The online questionnaire consists of several self-developed and existing measures capturing parents’ demographic background, parents’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, parent-child activities at home, and parental stress. For parents with multiple children, we asked them to complete the questionnaire based on their interactions with their preschool age child. If two or more of their children were in preschool, we asked the parents to complete the questionnaire based on their overall experience of interactions with their children at home.

Parents’ Experience During the Pandemic

Exposure. Parents were asked to indicate to what extent their family directly experienced the pandemic by completing a four-item checklist (i.e., one or more family members lost jobs due to the pandemic, one or more family members were diagnosed with COVID-19, one or more family members were hospitalized during the pandemic, one or more family members worked from home due to the pandemic). A similar four-item checklist was also completed by parents to indicate to what extent their family indirectly experienced the pandemic in their community (e.g., one or more friends/colleagues/neighbors of mine lost jobs, one or more friends/colleagues/neighbors of mine were diagnosed with COVID-19). Two composite variables (i.e., direct pandemic exposure and community pandemic exposure) were created by counting the number of checklist items parents selected (range 0-4).

Family Experience. Parents were asked to complete a set of questions to indicate: the duration of the family’s physical distancing time; the types of support parents received from children’s teachers; and the types of support parents feel are urgently needed from community service providers. Parents were also asked to indicate the frequency of different types of home activities (i.e., literacy, math, science, motor skills, art, and electronic entertainment activities) and note the daily occurrence or monthly occurrence of these activities. In addition, parents were asked to rate the level of pandemic impact on family routine and parent-child interactions from “nothing at all” to “significant impact.”

Parental Stress

Parent Perceptions of Changes in Child Behavior. Parents were asked to give a rating to indicate the changes in the frequency of three behavioral problems in their children (i.e., physical misbehaviors and aggression, such as fighting and kicking; disobedience or challenge of family rules; and expression of negative emotions, such as crying, yelling, or showing anxiety) during the pandemic. The internal consistency of these three Likert-scale items is .82 (Cronbach’s alpha). A composite variable was created for data analysis by summing up parents’ ratings of each item, with a possible range from three to 15.

Parent’s Perception of Changes in Their Well-Being. Parents were asked to give a rating to indicate the changes in frequency of occurrence of four types of challenges in their own lives (i.e., negative emotions such as depression, anxiety and stress; fatigue and exhaustion; conflict with children; and conflict with other family members) based on self-evaluation of their well-being before and during the pandemic. The internal consistency of these four Likert-scale items is .87 (Cronbach’s alpha). A composite variable was created for data analysis by summing up parents’ ratings of each item, with a possible range from four to 20.

Parental Stress. The Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF, fourth edition, Abidin, 201222) was used to measure parents’ stress during the pandemic. It has three dimensions labeled as Parent Distress (PD), Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction (PCDI), and Difficult Child (DC). Each dimension includes 12 statements that describe parents’ emotional states, the quality of parent-child interactions, and children’s behavioral problems. Parents were asked to rate each statement from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The PSI-SF has been frequently used in studies of parents with children three months to 10 years old (e.g., Britner et al., 200323) and parents from minority backgrounds (e.g., Reitman et al., 200224). The internal consistency of PSI-SF in this study is .95 (Cronbach’s alpha). In this study, participating parents were first asked to complete the PSI-SF based on their experience before the pandemic. Parents were then asked to complete the PSI-SF based on their experience during the pandemic. Composite variables were created at dimension levels by summing up the total scores of parents’ ratings of the items in each dimension, with a possible range from 12 to 60.

Results and Discussions

Family Experience During the Pandemic

Descriptive statistics (see Table 1) showed that most families followed local stay-at-home mandates for physical distancing at home by May 2020 (65.5 percent families in this study had stayed at home for one to two months). Around 90 percent of the parents reported the closure of their children’s childcare center amid the pandemic. About 85 percent of the parents in this study reported that they directly experienced COVID-19, but at different levels of exposure (e.g., family members were diagnosed with COVID-19 or lost jobs during the pandemic). About 95 percent of parents reported that they experienced community exposure to COVID-19 across different levels (e.g., friends or neighbors were diagnosed with COVID-19 or lost jobs during the pandemic). The majority of parents reported medium to high pandemic impact on family routine (94.3 percent) and the quality of parent-child interactions (81.2 percent).

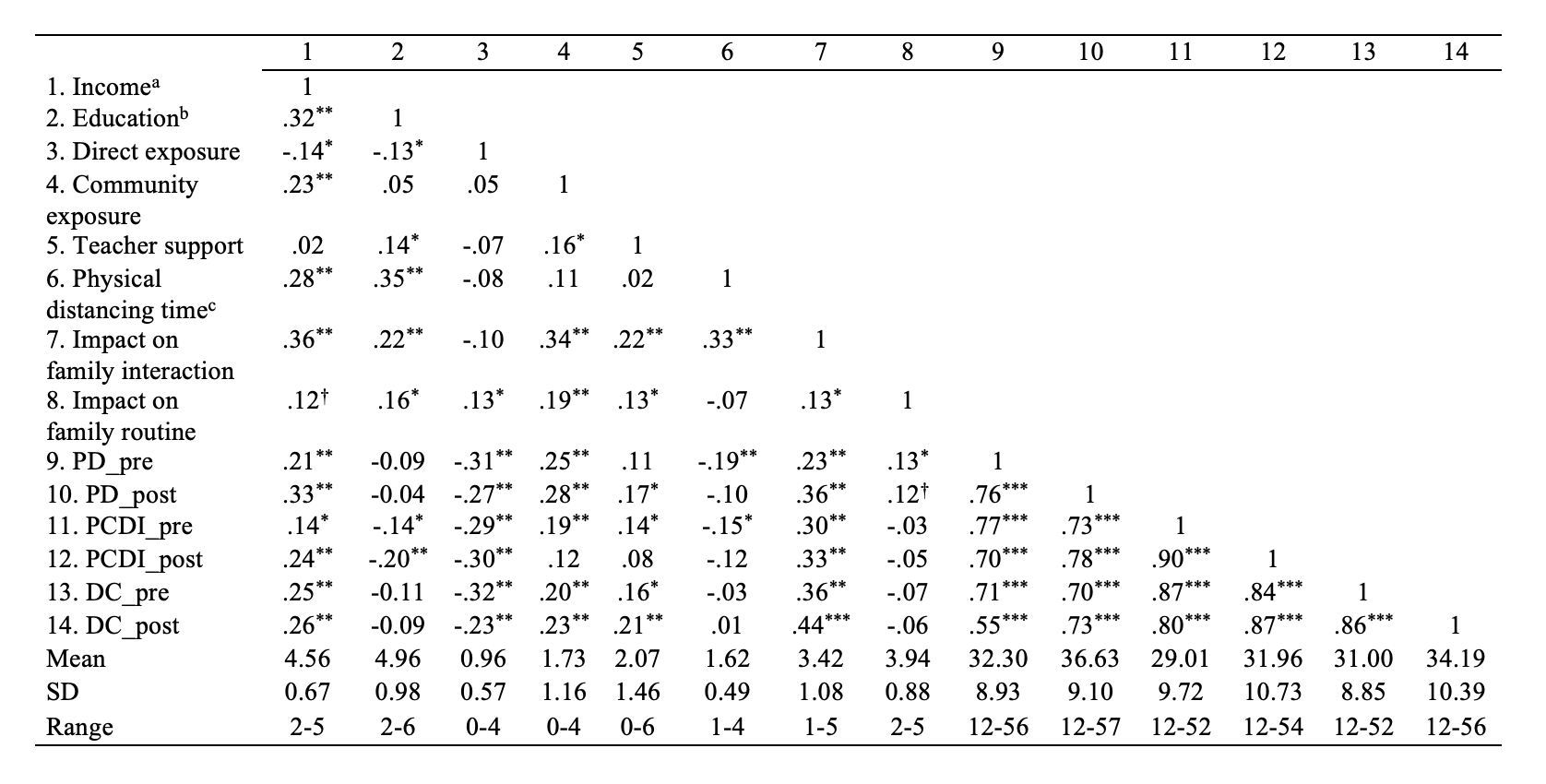

Table 1. Correlational matrix and descriptive statistics of family experience and parental stress (N=212).

About 80 percent of the parents in this study received some kind of support from their children’s teachers. Some parents indicated that their children’s teachers provided online meetings (48.6 percent) with their children or shared online resources (56.6 percent) for home learning activities. Some parents also received guidance from teachers for supporting children’s academic learning at home (43.4 percent). A smaller proportion of parents received support from teachers for promoting children’s socioemotional needs during self-isolation at home (25.9 percent). Parents provided a variety of home activities during physical distancing. However, electronic entertainment activities (e.g., iPad, TV, and computer) occurred much more frequently every day (50 percent) than other learning activities, such as literacy (37 percent), motor skills (34 percent), and math activities (23 percent). Among a variety of community support, providing learning materials (27 percent), introducing parenting strategies for supporting children’s emotional wellbeing (14.7 percent), and introducing more parent-child home activities (13.7 percent) were selected by the parents as the most needed support during the pandemic. About 10 percent of parents also indicated the need for remote mental health counseling for themselves (11.4 percent) and their children (9.5 percent).

Parental Stress During the Pandemic

A paired t-test was conducted first to examine the changes of parental stress during the pandemic. The results showed that parental stress significantly increased in all three domains: PD, t(211) = 10.01, p<.0001, Cohen’s d=.48; PCDI, t(211) = 9.50, p< .0001 Cohen’s d =.29; and DC, t(211) = 7.63, p<.0001, Cohen’s d=.34. It is important to note that close to 50 percent of participating parents may be considered clinically stressed during the pandemic according to PSI-SF criteria. Repeated measure ANOVAs (2 times x 2 ethnicity groups: Caucasian vs. Non-white, see Tables 2 and 3) showed that, in general, minority parents reported significantly higher stress than did Caucasian parents. Although all parents’ stress increased significantly during the pandemic, minority parents’ stress increased significantly greater than did Caucasian parents in the domains of PCDI (i.e., parent-child dysfunctional interaction) and DC (i.e., difficult child). This result suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic had significantly greater impact on minority parents’ psychological well-being compared to Caucasian parents.

-

| PD | PCDI | DC | ||||

| F | η2 | F | η2 | F | η2 | |

| Between-subjects effects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 18.74*** | .08 | 41.31*** | .17 | 30.70*** | .13 |

| Within-subjects effects | ||||||

| Time | 34.35 | 9.12 | 27.76 | 10.05 | 30.83 | 10.76 |

| Time x Ethnicity | .46 | .00 | 15.13*** | .07 | 3.03† | .02 |

Regression analyses were conducted to identify the significant predictors of parents’ stress during the pandemic after controlling for parent-perceived stress before the pandemic (see Table 4). These analyses revealed the factors that contributed to parents’ increasing stress during the pandemic and further confirmed that minority parents experienced significantly higher stress than did Caucasian parents. The significant association between parents’ gender and DC suggests that mothers perceived significantly higher stress than fathers over children’s behavioral and emotional problems. The inverse association between educational level and PCDI suggests that parents with higher educational levels perceived significantly lower stress over parent-child conflicts. In this study, family income showed significant positive association with parental stress, indicating that parents from higher-income families reported higher parental stress, especially stress related to parents’ own emotional state (PD) and parent-child conflicts (PCDI), than parents from lower-income families. This may be related to the fact that the majority of the participants in this study were from middle- and higher-income backgrounds. Correlational analyses (see Table 1) suggest another potential explanation. The parents from higher income families may have higher community exposure to COVID-19 (r=.23, p<.001) and may have longer physical distancing time r=.28, p<.001), while the parents from lower-income families tend to have higher direct exposure to COVID-19 (r= -.14, p< .05). The parents from lower-income families may still need to work during the pandemic and could not “afford” stay-at-home quarantine measures. In contrast, the parents from higher-income families may be able to stay at home during the pandemic, but the community exposure may also have a great impact on parents’ psychological well-being and the quality of parent-child interactions at home.

| PD | PCDI | DC | |||||||

| b | se | t | b | se | t | b | se | t | |

| Parental stress score before the pandemic | 0.68 | 0.05 | 14.84*** | 0.91 | 0.03 | 27.43*** | 0.93 | 0.04 | 21.05*** |

| Parent gender | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 2.48 | 0.91 | 2.71** |

| Education level | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | -0.89 | 0.37 | -2.58** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Income | 1.99 | 0.63 | 3.17** | 2.28 | 0.48 | 4.72*** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Ethnicity | 1.71 | 0.82 | 2.10* | 2.93 | 0.73 | 4.00*** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Social distancing time | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | -1.10 | 0.59 | -1.86† |

| Direct exposure | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | -0.87 | 0.54 | -1.62* | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Community exposure | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | -1.18 | 0.28 | -4.27*** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Impact on family interaction | 1.02 | 0.41 | 2.52** | 0.71 | 0.32 | 2.24** | 1.20 | 0.40 | 2.98** |

| Impact on family routine | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Teacher remote support | 0.44 | 0.27 | 1.62† | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.49 | 0.25 | 1.94* |

| R-square | 0.63 | 0.86 | 0.88 | ||||||

Family exposure to COVID-19, in terms of both direct and community exposure, did not show significant association with parental stress that was related to parents’ emotional state or children’s behavioral or emotional difficulties. However, a significant inverse association between family exposure and PCDI was observed. This suggests that the parents with higher exposure to COVID-19 reported less stress related to parent-child conflicts than did other parents. It is important to note that parent-perceived pandemic impact on family interactions showed a significant association with all dimensions of parental stress. And family exposure and physical distancing time both highly correlated with parent-perceived pandemic impact on family interactions. These findings may suggest that the parents in this study, when perceiving the pandemic’s impact on the quality of family interactions, may intentionally seek to reduce the impact of the pandemic on children. Scheering and Zeannah (200125) found that some parents may provide a sense of safety for their children during a traumatic event, which leads to their children’s increased ability to manage emotions and behaviors. Similarly, many parents may provide more responsive parenting to children when their families are exposed to COVID-19, which may lead to fewer parent-child conflicts during the pandemic.

Teachers’ support also showed significant association with increasing parental stress, specifically related to parent-perceived child behavioral or emotional difficulties. This finding may highlight the necessities of reviewing the effectiveness of professional support to parents during the pandemic. Based on parents’ report, the most common type of support they received from teachers during physical-distancing time at home revolves around online activities for children’s learning, rather than guidance for parenting or support for quality parent-child interactions. The parents’ needs were not met by professional support. The results in this study suggest that professional services, if not planned with consideration of parents’ need, may overwhelm parents. Recent studies of children’s post-trauma recovery suggest a trauma-informed approach to support children’s adjustment, specifically by closely working with parents (Conradi et al., 201126). This study suggests the need to further extend this model to other community service providers.

Conclusion

This study is one of few available that specifically examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on American families with young children. By investigating the association between family experiences during physical distancing time and parent-perceived stress, this study identified the factors that may contribute to parent-perceived stress during the pandemic. Generally speaking, young children’s parents perceived significantly higher stress during the pandemic. The parents from non-white minority background perceived higher stress than did Caucasian parents. While educational level was a protective factor for parental stress, the parents from higher income background perceived higher stress related to their emotional state and parent-child interaction. Many parents may intentionally seek to relieve the pandemic’s impact on their children. A community support system providing services to provide better parenting strategies and foster resilience during the pandemic is greatly needed.

References

-

Stokes, E. K., Zambrano, L. D., Anderson, K.N., et al. (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance — United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69, 759–765. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e2external icon ↩

-

Griffith, A.K. (2020). Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic.* Journal of Family Violence*. DOI: 10.1007/s10896-020-00172-2 ↩

-

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G.J. (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 395, 912-920. ↩

-

Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., & Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet 395, 945–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X ↩

-

Deater-Deckard, K. (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 314–332. ↩

-

Morgan, J., Robinson, D., & Aldridge, J. (2002). Parenting stress and externalizing child behaviour. Child & Family Social Work, 7, 219–225. ↩

-

Crnic, K., & Greenberg, M. (1990). Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development, 61, 1628–1637. ↩

-

Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting stress index (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. ↩

-

Kolbuck, V. D., Muldoon, A. L., Rychlik, K., Hidalgo, M. A., & Chen, D. (2019). Psychological functioning, parenting stress, and parental support among clinic-referred prepubertal gender-expansive children. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 7, 254–266. ↩

-

Blankenship, S. L., Chad, F. E., Riggins, T., & Dougherty, L. R. (2018). Early parenting predicts hippocampal subregion volume via stress reactivity in childhood. Developmental Psychobiology, 61, 125–140. ↩

-

Abidin, R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 407–412. ↩

-

Whitson, M. L., & Kaufman, J. S. (2017). Parenting stress as a mediator of trauma exposure and mental health outcomes in young children.* American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87*, 531–539. ↩

-

Halevi, G., Djalovski, A., Kanat-Maymon, Y., Yirmiya, K., Zagoory-Sharon, O., Koren, L., & Feldman, R. (2017). The social transmission of risk: Maternal stress physiology, synchronous parenting, and well-being mediate the effects of war exposure on child psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126, 1087–1103. ↩

-

Garcia, A. S., Ren, L., Esteraich, J. M., & Raikes, H. H. (2017). Influence of child behavioral problems and parenting stress on parent–child conflict among low-income families: The moderating role of maternal nativity. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 63, 311–339. ↩

-

Farver, J. M., Xu, Y., Eppe, S., & Lonigan C. J. (2006). Home environments and young Latino children’s school readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21, 196-212. ↩

-

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, American Psychologist, 75, 631-643. ↩

-

Neria, Y., Nandi, A., & Galea, S. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychological medicine, 38, 467–480. Doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001353 ↩

-

Sprang, G., & Silman, M. (2013) Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 7, 105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22. ↩

-

Ladwig, K.-H., Marten-Mittag, B., Erazo, N., & Gündel, H. (2001). Identifying somatization disorder in a population-based health examination survey: Psychosocial burden and gender differences. Psychosomatics, 42, 511–518. ↩

-

Raikes, H. A., & Thompson, R. A. (2005). Efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting stress among families in poverty. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, 177-190. ↩

-

Driver, N., & Amin, N. S. (2019). Acculturation, social support, and maternal parenting stress among US Hispanic mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(5), 1359–1367. ↩

-

Abidin, R. R. (2012). Parenting stress index (4th ed.). Lutz, FL: PAR. ↩

-

Britner, P.A., Morog, M.C., Pianta, R.C., & Marvin, R. S. (2003). Stress and coping: A comparison of self-report measures of functioning in families of young children with cerebral palsy or no medical diagnosis. Journal of Child and Family Studies (12), 335–348. ↩

-

Reitman, D., Currier, R. O., & Stickle, T. R. (2002). A critical evaluation of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) in a head start population. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31,384–392. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_10 ↩

-

Scheeringa, M., & Zeanah, C. H. (2001). A relational perspective on PTSD in early childhood. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, 799-815 ↩

-

Conradi, L., Agosti, J., Tullberg, E., Richardson, L., Langan, H., Ko, S. & Wilson, C. (2011). Promising practices and strategies for using trauma-informed child welfare practice to improve foster care placement stability: A breakthrough series collaborative. Child Welfare, 90, 207-225. ↩

Zhang, C. & Qiu, W. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Parental Stress and Young Children’s Development During Physical Distancing (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 312). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-parental-stress-and-young-childrens-development-during-physical-distancing