Impacts of COVID-19 on the Social Determinants of Health

Publication Date: 2021

Abstract

Along with the direct health impacts of COVID-19, the pandemic disrupted economic, educational, health care, and social systems in the United States. This cross-sectional study examined the primary and secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among low-income and minority groups in the state of New York using the social determinants of health framework. New Yorkers were recruited to complete a web-based survey by Qualtrics, a survey research firm. The survey took place in May and June of 2020 and asked respondents about COVID-19 health impacts, risk factors, and concerns. Chi-square analysis was used to examine disparities in these health effects as experienced by people belonging to different racial and ethnic groups. Significant results were analyzed in a series of logistic regression models. Results showed that members of all ethnic and racial minorities included in the survey were more likely than White respondents to experience direct impacts of COVID-19 as well as secondary impacts such as concerns about economic stability, and access to education and health care. Given the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 on minority populations, this study demonstrates that improved policies and programs are needed to address impacts on lower-paying essential jobs to reduce exposure risks and improve safety. Future research could identify how social determinants affected the long-term health consequences of the pandemic on vulnerable populations.

Introduction

COVID-19 created widespread disruption to the economy, healthcare systems, education, neighborhoods, and social life. Public health control measures like social distancing, quarantine, and travel restrictions led to a reduction in economic activity and job loss, particularly for those in the hospitality, tourism, and transportation sectors (Montenovo et al., 20201; Nicola et al., 20202). Individuals with higher levels of education were more likely to work in jobs where remote work was possible where those with lower levels of education were more likely to work in jobs that required work outside of the home (Montenovo et al., 2020). Employment losses were higher among individuals working in jobs that required face-to-face interaction (Montenovo et al., 2020). Furthermore, food system disruptions resulting from panic buying and stockpiling led to concern about food shortages and higher prices (Nicola et al., 2020). Early evidence suggests that food insecurity significantly increased as a result of the social and economic impacts of COVID-19 (Bauer, 20203; Fitzpatrick et al., 20204; Niles et al., 20205). Economic instability, and food insecurity are closely related to health (Higashi et al., 20176).

Healthcare workers faced direct infection risk and high healthcare costs, shortages of protective equipment, low numbers of intensive care unit beds, and a lack of ventilators exposed weaknesses in patient care delivery. Access to care for many who may have had higher risk of exposure was limited due to lack of healthcare system capacity (Nicola et al., 2020). Schools across the nation quickly transitioned to online formats resulting in reductions in employment and productivity for parents, due in part to a loss of child care and disruptions in access to free school meals. Shifting online exacerbated disparities in Internet access, devices, and applications as well as the abilities of students and teachers to engage with a digital learning format. These shifts called into question whether digital environments are adequate to meet the educational and social needs of students (Burgess & Sievertsen, 20207; Iivari et al., 20208).

Disaster mental health research suggests that emotional distress is ubiquitous among affected populations and anxiety and depression are particularly likely with COVID-19 (Pfefferbaum & North, 20209). Limited research on the psychological effects of global pandemics have demonstrated increased psychological distress (Brooks et al., 202010) resulting from the primary effects of the disease and secondary effects such as economic depression, loneliness, and social isolation (Nelson et al., 202011). Studies on the psychological impacts of COVID-19 have found increased reports of loneliness and depression during the pandemic. The job insecurity and financial concerns that have accompanied the pandemic are also associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Killgore et al., 202012; Nelson et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 202013).

The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected all non-White ethnic and racial groups included in this study. Factors contributing to these disparities included higher rates of preexisting medical problems (i.e. diabetes, hypertension, renal disease, and obesity) that increase the severity of disease and mortality are also associated with less access to health care (Tai et al., 202014). Socioeconomic disparities further exacerbated these populations exposure to COVID-19. People of color perform a greater proportion of service industry and jobs considered essential during the pandemic. Even those who were able to stay home were more likely to live in higher density housing or in multigenerational households that made social distancing difficult (Tai et al., 2020).

New York State experienced an early surge in COVID-19 cases, primarily in the New York City metro area. The first positive test was found on March 8, 2020, and positive test daily rates reached a peak on April 14, 2020 with 11,571 individuals testing positive (43.1% daily positive rate) (New York Forward, 202015). Due to challenges with testing capacity and reliability, these numbers are likely an underestimate of actual disease burden in the state (Dudzik, 202016; Reisman, 202017). On March 20, Governor Andrew M. Cuomo issued an executive order known as "New York State on PAUSE," a stay-at-home order and closure of all non-essential businesses for the entire state as part of the public health measures to slow the spread of COVID-19 (Cuomo, 2020a18, 2020b19). As COVID-19 infection rates and the number of deaths rose, racial and ethnic disparities attributable to systemic racism and inequity within health care, economic, and social systems arose. Analysis of infection rates showed that Black and Latino individuals were three times more likely to become infected with COVID-19 and were twice as likely to die as Whites in the United States (Lieberman-Cribbin et al., 202020; Mays & Newman, 202021; Oppel et al., 202022). Population level data showed that lower income individuals were less likely to get tested and more likely to be positive when tested. These are also the populations who are more likely work in essential jobs such as those in municipal, factory, service, and healthcare settings (Lieberman-Cribbin et al., 2020). With widespread community disruption and risk factors at the individual, community, and policy levels that create health disparities, a social determinants of health approach to this survey was best for understanding differential impacts of COVID-19 in New York State (Dahlgren & Whitehead, 199323).

Social determinants of health are “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks” (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.-b24). Determinants are grouped into five categories: economic stability, education, healthcare access, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.-b). Economic stability measures how reliably a person has enough income to meet health needs such as housing and nutrition,. Education includes access to educational opportunities and assistance for succeeding in school. Health care includes access to high quality and comprehensive health services and health insurance. Neighborhood and built environment includes the features of the places where individuals live, work, and play that contribute to individual health and safety. These features include exposure to crime, air and water pollutants, having safe homes, access to spaces for physical activity, and safe transportation, and safe workplaces. Social and community context includes social and community relationships and interactions that support individual health and well-being (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.-a25).

Disasters and public health emergencies disrupt social and built environmental systems that impact the daily routines and stability of households and communities ([Lindell & Prater, 2003]^Lindell and Prater, 2003]). In addition to the primary health impacts of a hazard, such as an injury or illness, there are many secondary health effects that influence the health and well-being of individuals. To more fully understand the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for families, it is important to characterize a broader range of impacts on health determinants. Using a social determinants of health framework (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.-b), this study examined differences in the primary and secondary health impacts of COVID-19 among low-income and minority groups in New York State. At the time of writing (March 13, 2020), New York State had conducted 12.2 million COVID-19 tests, there have been 476,708 documented positive tests, and 25,598 residents have died from the virus (NY State Department of Health, 202026).

Methods

Study Design

A cross-sectional web survey was used to ask about COVID-19 health impacts, risk factors, food access, and concerns related to the social determinants of health. The survey was adapted from an already validated National Food Access Research Team (NFACT) survey (Niles, Bertmann, Belarmino, et al., 202027; Niles et al., 2020). Questions about food access and security were adopted directly the NFACT survey and validation analysis of the survey showed an alpha value of 0.70 (M. Niles, Bertmann, Belarmino, et al., 2020). To comprehensively assess the social determinants of health, we added two sets of validated questions to the survey—including an assessment of anxiety and depression, and questions about the disease's impact on employment and health—adapted from surveys in the PhenX COVID-19 Toolkit, which is a battery of consensus measures assembled by expert working groups funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NGHRI) (Bernard et al., 202028; Cawthon et al., 202029; Fisher et al., 202030; Kroenke et al., 200331, 200732; MESA COVID-19 Questionnaire, 202033; NHGRI, n.d.34)

Recruitment and Data Collection

A quota-based, non-proportional sample of 415 individuals in the state of New York, excluding counties in the New York City metropolitan area, were recruited by Qualtrics during the phased reopening stages of New York State on PAUSE . New York City was left out of the survey due to the vastly different context of city and state communities (Axelson, 202035; New York Forward, 2020). Quotas were designed to oversample minority (50% Hispanic, 50% Black or African American) individuals with low income or low levels of education (50%) and male respondents (50%) to ensure a sufficient sample size to analyze the experiences of individuals at high risk for adverse COVID-19 consequences. During recruitment, Qualtrics aims to achieve a sample as close to these proportion as possible in the target geographic area of recruitment. In 2018, 89% of White, 88% of Hispanic, and 87% of Black or African Americans and 81% of Americans with an annual income of less than $30,000 use the internet (Pew Research Center, 201936), therefore a web survey is appropriate for reaching the target population.

Participants were recruited from survey panels maintained by Qualtrics (Qualtrics, n.d.-a37). Panel members were eligible to participate if they were age 18 or older and lived in New York State, excluding New York City. Potential participants were asked about their race, ethnicity, education, income, and gender to fill the quotas set for the study. Participants who met the inclusion criteria but fell outside of the quotas needed for the sample were ineligible to continue. A total of 1,274 people began the survey, 475 were excluded due to ineligibility, such as not living in a recruitment county, not fitting the criteria of the quotas, or not consenting to participate. Another 325 participants were removed due to poor quality responses, such as speeding, straight-lining, or providing nonsense responses (Miller et al., 202038; Qualtrics, n.d.-b39). Qualtrics does not provide a response rate with its panel data. The research team does not have access to records showing how many people were invited to participate in the survey. Data is only available on how many people started and completed the survey. Data collection was completed between May 14 and June 8, 2020. The median time for survey completion was 13 minutes.

Measures

Surveyors assessed race by asking respondents to select all self-identified races from a list of 13 options. Respondents were coded into racial groups of White, Black or African American, other, and more than one race. Hispanic ethnicity was assessed by asking respondents to indicate if they identify as having Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origins. Respondents were categorized as either Hispanic or not Hispanic. The race and ethnicity variable for this study classified each respondent as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black or African American, Hispanic, or other, or more than one race.

Direct health impacts of COVID-19 were assessed by asking respondents if they knew anyone who had tested positive, been quarantined, been hospitalized, or died due to the virus and about current mental health. Respondents were classified as having direct COVID-19 impact if they checked “self” for any of impact categories and impact on family or friends if they checked “family” or “friend” for any category. Likely depression was assessed using PHQ-2, a two-item screener for depressive disorders (Kroenke et al., 2003). The two-items were scored (range 0-6). A cut point of three was used to classify respondents with likely major depressive disorder (83% sensitivity and 90% specificity) (Kroenke et al., 2003). Anxiety was assessed with the GAD-2, a two-item screener for generalized anxiety disorder (Kroenke et al., 2007). The two-items were scored (range 0-6). A cut point of three was used to classify respondents with likely generalized anxiety disorder (86% sensitivity and 83% specificity) (Kroenke et al., 2007).

Secondary health impacts were evaluated using a social determinants of health framework and include economic stability, education, health care, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community contextual factors. Each factor and its associated measure are described below.

Economic Stability

This category measured income level, reduced work and concerns about job security, housing, debt, and food security. The survey asked participants to select the range that best described their income in 2019 before taxes (categorized as less than $25,000, $25,000-50,000, and greater than $50,000). The pandemic impact on hours worked was assessed by asking respondents to check all that apply from a list of job impacts including working more hours, working less hours, furloughed, laid off, working from home, unemployed before the pandemic, or no changes (categorized as reduced work or no reduced work). Respondents concerns about job security, housing, debt, and food security were assessed using a Likert scale to indicate how often (never, sometimes, most of the time, always) they have been concerned about those issues. Responses were put into two categories, ever (sometimes, most of the time, always) or never (never).

Education

Concerns about education were assessed on a Likert scale by asking how often (never, sometimes, most of the time, always) they were concerned about schooling. Responses were categorized as ever (sometimes, most of the time, or always) or never (never).

Healthcare

Respondent access to health care was assessed on a Likert scale. They were asked to indicate how often (never, sometimes, most of the time, always) they were concerned about healthcare access since the pandemic began. Responses were categorized as ever (sometimes, most of the time or always) or never (never). Health insurance status was assessed by asking respondents whether they had public, private, or no health insurance. Health insurance was categorized as either insured (public or private insurance) and uninsured (no insurance).

Neighborhood and Built Environment

Respondents were asked about the frequency (never, sometimes, most of the time, always) with which they engaged in certain behaviors in built environments, such as standing too close to others while getting food, going to bars and restaurants, making fewer grocery shopping trips, and the need for more public transportation access during the pandemic. Responses were categorized as ever (sometimes, most of the time, always) or never (never) for each behavior. Respondent access to public transportation was assessed by asking how helpful (not helpful, somewhat helpful, helpful, very helpful) it would be for their household to have more access to public transportation and responses were categorized as helpful (somewhat helpful, helpful or very helpful) or not helpful (not helpful).

Social and Community Context

This category included perceptions of response to the pandemic by different levels of government (city government, state government, federal government, public health agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and communications about protecting households. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with a set of statements about response to the pandemic (strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, agree, strongly agree). Respondents were classified as agreeing the response was effective if they indicated somewhat agree, agree, or strongly agree.

Data Analysis

Sample characteristics and health effects of COVID-19 were described and chi-square analysis completed to examine differences in health impacts by race and ethnicity. Factors that were statistically significant across groups were analyzed in a series of unadjusted logistic regression models (unadjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals reported). Statistical analysis was completed using Stata 16 software (StataCorp, 201940).

Ethical Considerations

Study participants agreed to the terms of a consent document and confirmed they were 18 or older before beginning the survey. This study was approved by D’Youville College Institutional Review Board and was given exempt status because the survey data collection was anonymous.

Results

Characteristics of the Sample

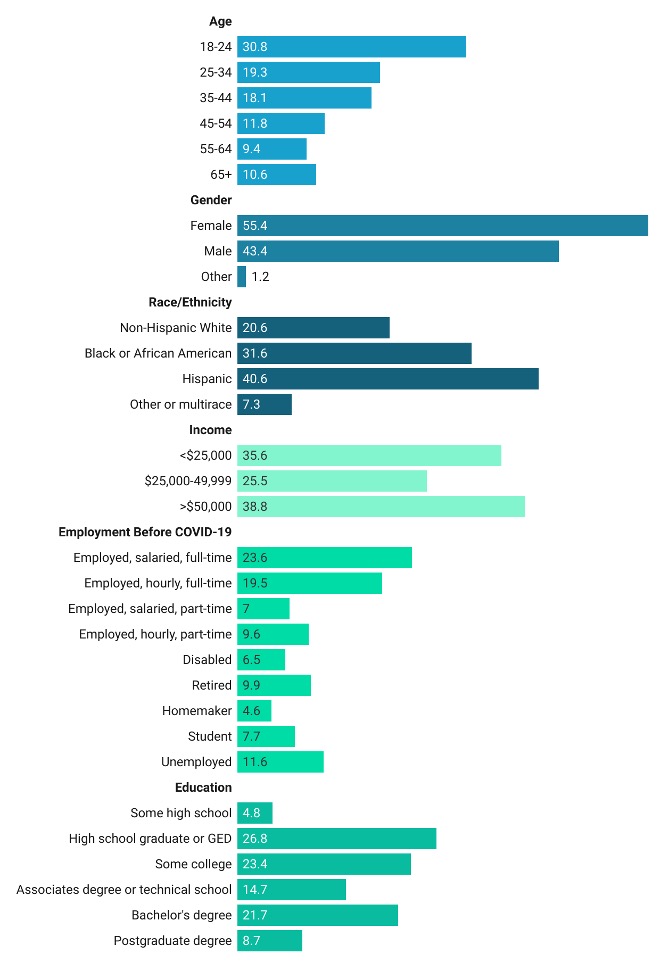

Participants in the sample were 41% Hispanic, 32% Black or African American, and 21% White (Figure 1). Females made up 55% of the sample and another 1% of the sample reported non-binary or other gender. More than half of study participants reported an annual income in 2019 of less than $50,000 and 36% reported making less than $25,000. Nearly one third of the sample reported having a high school education or less and 43% of respondents were working full time before the pandemic.

Figure 1. Sample Characteristics

Chi-square analysis showed significant differences between ethnic and racial groups for two direct impacts of COVID-19, all five economic stability factors, the single education factor, one healthcare factor, and one neighborhood and built environment factor. There were no significant results for the social and community context factors (Table 2).

Table 2: Race and Ethnic group differences for primary and secondary COVID-19 social and health impacts (chi2 )

| Direct and Indirect Social and Health Impacts | Non-Hispanic White | Black or African-American | Hispanic | Other or Multiracial | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Direct Impacts | ||||||||

| Direct COVID-Impact: Self | 11 | 14.3 | 31 | 40.3 | 29 | 37.7 | 6 | 7.8 |

| Direct COVID-Impact: Family/Friend*** | 32 | 13.0 | 87 | 35.4 | 110 | 44.7 | 17 | 6.9 |

| Likely Generalized Anxiety Disorder* | 26 | 16.7 | 44 | 28.2 | 77 | 49.4 | 9 | 5.8 |

| Likely Major Depressive Disorder | 29 | 17.5 | 53 | 31.9 | 74 | 44.6 | 10 | 6.0 |

| Economic Stability | ||||||||

| Income** | ||||||||

| <$25,000 | 15 | 10.8 | 51 | 36.7 | 63 | 45.3 | 10 | 7.2 |

| $25,000-50,000 | 19 | 18.3 | 34 | 32.7 | 38 | 36.5 | 13 | 12.5 |

| >$50,000 | 48 | 30.8 | 41 | 26.3 | 61 | 39.1 | 6 | 3.9 |

| Reduced Work* | 21 | 13.2 | 48 | 30.2 | 77 | 48.4 | 13 | 8.2 |

| Concerns About Job Security*** | 36 | 14.1 | 84 | 32.9 | 113 | 44.3 | 22 | 8.6 |

| Concerns About Paying Rent/Mortgage*** | 31 | 12.4 | 81 | 32.4 | 114 | 45.6 | 24 | 9.6 |

| Concerns About Debt** | 41 | 16.1 | 78 | 30.6 | 116 | 45.5 | 20 | 7.8 |

| Risk for Food Insecurity Since COVID-19** | 23 | 13.7 | 53 | 31.6 | 78 | 46.4 | 14 | 8.3 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Concerns About Schooling** | 26 | 12.9 | 66 | 32.7 | 92 | 45.5 | 18 | 8.9 |

| Health Care | ||||||||

| Concerns About Healthcare Access** | 44 | 16.8 | 78 | 29.8 | 113 | 43.1 | 27 | 10.3 |

| Health Insurance | 75 | 21.3 | 113 | 32.0 | 143 | 40.5 | 22 | 6.2 |

| Neighborhood and Built Environment | ||||||||

| Standing Too Close When Shopping | 46 | 19.3 | 74 | 31.1 | 99 | 41.6 | 19 | 8.0 |

| Going to Restaurants Less During COVID | 49 | 19.7 | 72 | 28.9 | 108 | 43.4 | 20 | 8.0 |

| *** p<.001; **p<.01; *p<.05 | ||||||||

The results of the logistic regressions revealed disparities in the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19. The majority of differences were reported between Hispanic and White respondents. The largest differences, in terms of magnitude, were reported between other or multiracial respondents and White respondents (Table 3). A discussion of the direct and indirect impacts follows. Indirect impacts are organized according to the social determinants of health.

Table 3. Unadjusted Odd Ratios of Primary and Secondary COVID-19 Impacts by Race and Ethnicity

| White | Black or African American | Hispanic | Other or Multiracial | |||||

| OR | 95 % | OR | 95 % | OR | 95 % | OR | 95 % | |

| Direct Impacts | ||||||||

| Direct COVID-Impact: Family/Friend*** | ref^ | 3.5 | 1.95, 6.24 | 3.3 | 190, 5.75 | 2.2 | 0.93, 5.24 | |

| Likely Generalized Anxiety Disorder* | ref | 1.2 | 0.64, 2.09 | 2.0 | 1.12, 3.41 | 1.0 | 0.39, 2.42 | |

| Economic Stability | ||||||||

| Income** | ref | 0.3 | 0.17, 0.64 | 0.4 | 0.18, 0.67 | 0.4 | 0.16, 1.10 | |

| Reduced work** | ref | 1.8 | 0.97, 3.30 | 2.6 | 1.47, 4.72 | 2.4 | 0.98, 5.71 | |

| Concerns About Job Security*** | ref | 2.6 | 1.44, 4.53 | 3.0 | 1.70, 5.11 | 4.0 | 1.54, 10.44 | |

| Concerns About Paying Rent/Mortgage*** | ref | 3.0 | 1.66, 5.27 | 3.9 | 2.23, 6.84 | 7.9 | 2.73, 22.84 | |

| Concerns About Debt** | ref | 1.6 | 0.93, 2.85 | 2.5 | 1.45, 4.38 | 2.2 | 0.91, 5.45 | |

| Risk of Food Insecurity Since COVID-19** | ref | 2.4 | 1.28, 4.48 | 3.0 | 1.65, 5.42 | 3.5 | 1.33, 9.28 | |

| Education | ||||||||

| Concerns About Schooling** | ref | 2.4 | 1.32, 4.24 | 2.8 | 1.62, 4.95 | 3.5 | 1.46, 8.52 | |

| Health Care | ||||||||

| Concerns about Healthcare Access*** | ref | 1.4 | 0.80, 2.47 | 2.0 | 1.15, 3.45 | 11.7 | 2.60, 52.28 | |

| Neighborhood and Built Environment | ||||||||

| Making Fewer Grocery Trips During COVID* | ref | 1.8 | 0.95, 3.37 | 2.3 | 1.25, 4.32 | 6.3 | 1.38, 28.37 | |

| *** p<.001; **p<.01; *p<.05 ^ref = Reference group |

||||||||

Direct impacts of COVID-19 were increased among non-White respondents, with 3.5 greater odds of Black or African American respondents knowing a friend or family member infected with COVID-19 compared with White respondents (OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.95, 6.24) (Table 4). The odds of this effect were 3.3 times greater for Hispanic respondents than for White respondents (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.90, 5.75). Hispanic respondent odds of having generalized anxiety disorder were two times greater than White respondents (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.12, 3.41).

Racial and ethnic differences were observed in measures of economic stability, including income, work disruptions, concerns about job security, paying rent/mortgage, debt, and risk of food insecurity. All groups had greater odds of experiencing at least three of these measures compared with White respondents. Hispanic respondents had increased odds of experiencing all six of the economic stability measures compared with White respondents. Both Black and other or multiracial respondents had greater odds of experiencing three of the six economic stability measures, including concerns about job security, paying rent or mortgage, and risk of food insecurity compared with White respondents. All minority groups were less likely than White respondents to have had greater income in 2019 than in 2020. Notably, the odds of experiencing concerns about job security (OR 4.0, 95% CI 1.54, 10.44) and paying rent or mortgage (OR 7.9, 95% CI 2.73, 22.84) for other or multiracial respondents were 4.0 and 7.9 times the odds of White participants, respectively.

All racial and ethnic groups experienced increased concerns about schooling compared with White respondents. The odds of experiencing concerns about schooling for Black or African American (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.32, 4.24), Hispanic (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.62, 4.95), and other or multiracial (OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.46, 8.52) respondents were more than twice the odds of White respondents. Hispanic and other or multiracial respondents experienced greater concerns about health care access compared with White respondents. The odds of experiencing concerns about health care access for Hispanic respondents was double the odds of White respondents (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.15, 3.45), and other or multiracial respondents had 11.7 times the odds of White respondents (OR 11.7, 95% CI 2.60, 52.28).

Hispanic and other or multiracial respondents were more likely to make behavior changes related to their neighborhood or built environment. Hispanic respondents reported making fewer trips to grocery stores during the pandemic compared with White respondents (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.25, 4.32). Other or multiracial respondents had 6.3 greater odds of making fewer grocery trips compared with White respondents (OR 6.3, 95% CI 1.38, 28.37).

Conclusions

Key Findings

This study found differences in the primary and secondary health impacts of COVID-19 among minority groups in New York State. Black or African American and Hispanic respondents were more likely to experience direct impacts of COVID-19 compared with White respondents. Hispanic, Black or African American, and respondents identifying as other races or multiracial were more likely to express concern about economic stability and education compared with White respondents. Hispanic and other or multiracial respondents were more likely to express concerns about access to health care and make fewer grocery trips during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implications

Disparities in the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19 were observed among minority populations in New York State. The majority of differences reported were between Hispanic and White New Yorkers, with the largest differences reported between other or multiracial respondents and White respondents. Given the disproportionate burden that COVID-19 places on minority populations, improved policies and programs to address COVID-19 changes to work environments for jobs in the service industry, and in healthcare and factory settings could reduce risks of disease exposure and improve worker safety for minority populations. The increased risk of COVID-19 infection and death among Hispanic and Black Americans and structural racism in the United States makes it critical that they participate in pandemic and public health policy. Pandemic and emergency planning requirements for federal and state agencies should require increased stakeholder participation from minority groups. Funding for community planning should be used to support increased participation by the groups that experience disproportionate burdens from the pandemic. It is also important to establish policies and processes that support racial sensitivity and implicit bias training for all employees working in health care and public health. These policies should include measures to identify at-risk groups in hospital and clinic protocols. Future pandemic relief legislation should also include additional financial support for these groups. Future research is needed to understand the long-term health consequences of the pandemic on the social determinants of health among the populations that are most at-risk. More research on interventions that best support communities of color is also critical to improving health outcomes.

Dissemination of Findings

Findings are being published in research and policy briefs that will be made available to policy makers, advocacy groups, agencies, and organizations working on responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Research and policy briefs are being shared by the NFACT team, Network and the Nutrition and Obesity Policy, Research, and Evaluation Network (NOPREN) COVID-19 Working Group. Research and policy briefs will also be posted on the Disaster Research Lab website, shared on the NFACT website, and published through DesignSafe-CI. Articles and conference abstracts are being developed to disseminate findings among researchers.

Limitations

This study used a cross-sectional design. It was an observational study and characterizing causal relationships was beyond its scope. To mitigate this limitation, survey questions asked respondents specifically about social determinants of health in relation to COVID-19. The sampling frame was designed to oversample individuals at increased risk for contracting COVID-19. As a result of purposive sampling, generalizations cannot be made about all New Yorkers. Given the already documented disparities in COVID-19 impacts between ethnic and racial groups, understanding the experiences of individuals with greater risk was privileged over representativeness. The survey was administered through a web-based platform, therefore, individuals without access to the internet were systematically excluded from participation. Because of the widespread impact the pandemic had in New York State, this methodology was selected to facilitate timely completion of data collection during the state's phased reopening. This study provides an important snapshot of the lived experiences of many New Yorkers.

Future Research Directions

Future research will take an in-depth look at factors that restrict or facilitate access to food. New research will examine food seeking behaviors, food insecurity risk, mental health influences on food insecurity, and how these problems were experienced by essential workers and individuals whose employment was disrupted by the pandemic. Collaborative studies with New York City, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Mexico are being planned to analyze state level policy differences and their impact on food security during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgements. The research team would like to thank the individuals who shared their experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic by completing the survey. We appreciate their time. This research was funded by a Natural Hazards Center, Quick Response Grant. The Quick Response program is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) (Award #1635593). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NSF or the Natural Hazards Center.

This research was conducted in association with the National Food Access and COVID Research Team (NFACT), which implements common measurements and tools across study sites in the United States. NFACT is a national group of researchers committed to rigorous, comparative, and timely food access research during COVID-19. This is done through collaborative, open-access research that prioritizes communication to key decision makers while building scientific understanding of food system behaviors and policies. Visit www.nfactresearch.org to learn more.

References

-

Montenovo, L., Jiang, X., Rojas, F., Schmutte, I., Simon, K., Weinberg, B., & Wing, C. (2020). Determinants of disparities in covid-19 job losses. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w27132 ↩

-

Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Sohrabi, C., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., Iosifidis, C., Agha, M., & Agha, R. (2020). The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery, 78, 185. https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ijsu.2020.04.018 ↩

-

Bauer, L. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis has already left too many children hungry in America. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/05/06/the-covid-19-crisis-has-already-left-too-many-children-hungry-in-america/ ↩

-

Fitzpatrick, K., Harris, C., Drawve, G., & Willis, D. (2020). Assessing Food Insecurity among US Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2020.1830221 ↩

-

Niles, M., Bertmann, F., Morgan, E., Wentworth, T., Biehl, E., & Neff, R. (2020). Food Access and Security During Coronavirus: A Vermont Study. University of Vermont. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/calsfac/21 ↩

-

Higashi, R., Lee, S., Pezzia, C., Quirk, L., Leonard, T., & Pruitt, S. (2017). Family and social context contributes to the interplay of economic insecurity, food insecurity, and health. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 41(2), 67–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12114 ↩

-

Burgess, S., & Sievertsen, H. (2020). Schools, skills, and learning: The impact of COVID-19 on education. VoxEu. https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education ↩

-

Iivari, N., Sharma, S., & Ventä-Olkkonen, L. (2020). Digital transformation of everyday life–how COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? International Journal of Information Management, 102183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183 ↩

-

Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. (2020). Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383, 510–512. https://doi.org/DOI:10.1056/NEJMp2008017 ↩

-

Brooks, S., Webster, R., Smith, L., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 14–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 ↩

-

Nelson, B., Pettitt, A., Flannery, J., & Allen, N. (2020). Rapid Assessment of Psychological and Epidemiological Predictors of COVID-19. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184. ↩

-

Killgore, W. D., Cloonen, S., Taylor, E., & Dailey, N. (2020). Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research, 290(113117). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117 ↩

-

Wilson, J., Lee, J., Fitzgerald, H., Oosterhoff, B., Sevi, B., & Shook, N. (2020). Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(9), 686–691. https://doi.org/doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962 ↩

-

Tai, D., Shah, A., Doubeni, C., Sia, I., & Wieland, M. (2020). The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases, ciaa815. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa815. ↩

-

New York Forward. (2020). Percentage Positive Results By County Dashboard. New York Forward. https://forward.ny.gov/percentage-positive-results-county-dashboard ↩

-

Dudzik, K. (2020, April 16). A look at the COVID-19 testing capacity in Erie County. WGRZ. https://www.wgrz.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/crunching-the-coronavirus-testing-numbers-in-erie-county/71-c527fc71-84ba-4e46-a7a5-d72f17404f5b ↩

-

Reisman, N. (2020, May 22). Facilities Face Challenges In Ramping Up Testing. Spectrum News. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nys/central-ny/ny-state-of-politics/2020/05/22/facilities-face-challenges-in-ramping-up-testing ↩

-

Cuomo, A. (2020a). Governor Cuomo Issues Guidance on Essential Services Under The “New York State on PAUSE” Executive Order. NY State Office of the Governor. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-issues-guidance-essential-services-under-new-york-state-pause-executive-order ↩

-

Cuomo, A. (2020b). The “New York State on Pause” Executive Order. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2020-03-20-Notice-New-York-on-Pause-Order.pdf ↩

-

Lieberman-Cribbin, W., Tuminello, S., Flores, R., & Taioli, E. (2020). Disparities in COVID-19 Testing and Positivity in New York City. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(3), 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.005 ↩

-

Mays, J., & Newman, A. (2020, April 8). Virus Is Twice as Deadly for Black and Latino People Than Whites in N.Y.C. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/nyregion/coronavirus-race-deaths.html ↩

-

Oppel, R., Gebeloff, R., Lai, K., Wright, W., & Smith, M. (2020, July 5). The Fullest Look Yet at the Racial Inequity of Coronavirus. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/05/us/coronavirus-latinos-african-americans-cdc-data.html ↩

-

Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (1993). Tackling inequalities in health: what can we learn from what has been tried. Working Paper Prepared for the King’s Fund International Seminar on Tackling ↩

-

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.-b). Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved September 17, 2020. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health ↩

-

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.-a). Social and Community Context. Retrieved September 17, 2020. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/social-and-community-context ↩

-

NY State Department of Health. (2020). Workbook: NYS-COVID19-Tracker. New York State Department of Health COVID-19 Tracker. https://covid19tracker.health.ny.gov/views/NYS-COVID19-Tracker/NYSDOHCOVID-19Tracker-Fatalities?%3Aembed=yes&%3Atoolbar=no&%3Atabs=n ↩

-

Niles, M., Bertmann, F., Belarmino, E., Wentworth, T., Biehl, E., & Neff, R. (2020). The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients, 12(7), 2096. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072096 ↩

-

Bernard, A., Weiss, S., Stein, J. D., Ulin, S. S., D’Souza, C., Salgat, A., Panzer, K., Riddering, A., Edwards, P., Meade, M., McKee, M. M., & Ehrlich, J. R. (2020). Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on persons with disabilities: development of a novel survey. International Journal of Public Health, 65(6), 755–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01433-z ↩

-

Cawthon, P. M., Orwoll, E. S., Ensrud, K. E., Cauley, J. A., Kritchevsky, S. B., Cummings, S. R., & Newman, A. (2020). Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying mitigation efforts on older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. ↩

-

Fisher, P., Desai, P., Klotz, J., Turner, J., Reyes-Portillo, J., Ghisolfi, I., Canino, G., & Duarte, C. (2020). COVID-19 Experiences (COVEX). https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/toolkit_content/PDF/Fisher_COVEX_Employment_Education.pdf ↩

-

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R., & Williams, J. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 1284–1292. ↩

-

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R., Williams, J., Monahan, P., & Lowe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146, 317–325. ↩

-

MESA COVID-19 Questionnaire. (2020). PhenX Toolkit. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/toolkit_content/PDF/MESA_Questionnaire.pdf ↩

-

NHGRI. (n.d.). PhenX Toolkit. Retrieved December 23, 2020. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/collections/view/8z ↩

-

Axelson, B. (2020). Coronavirus timeline in NY: Here’s how Gov. Cuomo has responded to COVID-19 pandemic since January. Syracuse.com. https://www.syracuse.com/coronavirus/2020/04/coronavirus-timeline-in-ny-heres-how-gov-cuomo-has-responded-to-covid-19-pandemic-since-january.html ↩

-

Pew Research Center. (2019). Demographics of Internet and Home Broadband Usage in the United States. Internet and Technology. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/ ↩

-

Qualtrics. (n.d.-a). Qualtrics XM // The Leading Experience Management Software. Retrieved November 5, 2020. https://www.qualtrics.com/ ↩

-

Miller, C., Guidry, J., Dahman, B., & Thomson, M. (2020). A tale of two diverse Qualtrics samples: Information for online survey researchers. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention, 29(4), 731–735. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0846 ↩

-

Qualtrics. (n.d.-b). Response Quality–Qualtrics Support. Retrieved November 5, 2020. https://www.qualtrics.com/support/survey-platform/survey-module/survey-checker/response-quality/ ↩

-

StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC. ↩

Clay, L. & Rogus, S. (2022). Impacts of COVID-19 on the Social Determinants of Health (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 321). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/impacts-of-covid-19-on-the-social-determinants-of-health