Making Us Whole Again? Lessons From Montana Disaster Recovery

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

In June 2022, counties across south-central Montana experienced a one-in-500-year flood event. Roads and bridges were washed away, and homes were destroyed. Clean water, electricity, and sanitation services were interrupted. The economic livelihoods of thousands were impacted. The highly publicized evacuation of 10,000 visitors from Yellowstone National Park due to the flooding danger highlighted the precarity of isolated, rural areas when facing a natural disaster. This project explores whole-community disaster recovery and resiliency from the perspective of local government workers in four Montana counties. Employing a mixed-methods approach, this study uncovers how public officials across the disaster-impacted landscape conceptualize community recovery and what these individuals believe is necessary to build future disaster and community resiliency. Preliminary findings indicate that both built environment and social capital are important indicators of disaster recovery, and that future resiliency is dependent upon strengthening human and financial capacity. This study has implications for rural communities seeking to foster greater community disaster management capacity and for federal and state partners.

Introduction

On June 14, 2022, Montana Governor Greg Gianforte declared a statewide disaster due to severe flooding from rapid snowmelt and heavy rains. Communities in south-central Montana, the state’s Yellowstone Country region, were particularly hard hit. Homes were destroyed, roads and bridges were washed away, local communities were without basic water and power services, and thousands of Montana residents’ economic livelihoods were devastated.

On June 16th, President Joseph Biden approved a major disaster declaration for Montana, releasing federal assistance to supplement tribal nation, state, and local recovery efforts. Individual Assistance (IA) was made available to eligible individuals and households with losses or needs not covered by insurance in Carbon, Park, Stillwater, and Yellowstone Counties. Public Assistance (PA) was activated to aid public and some private nonprofit entities in Carbon, Flathead, Park, Stillwater, Sweet Grass, Treasure, and Yellowstone Counties for certain emergency services and the repair or replacement of disaster-damaged public facilities (see Appendix A for map).

Where you stand in disaster response, recovery, and resiliency necessarily depends upon where you sit. Following the historic 2022 flood event in south-central Montana, this research seeks to explore the differential understandings and experiences of various groups within communities during and after a disaster, beginning with local government officials. By listening to and learning from impacted individuals and communities, emergency managers and public decision makers can better assist in disaster recovery and help cultivate local resiliency. Analyzing data collected from a combination of anonymous web-based surveys and in-depth semi-structured interviews, this exploratory study uncovers how rural local government officials experience the community disaster recovery process and what, in their minds, constitutes complete recovery and future resiliency.

Disaster Recovery and Rural Communities

Community disaster recovery starts soon after a disaster occurs, when emergency response actions conclude, and a community begins efforts to return to relatively normal daily life (Rubin, 20091). The recovery phase of disaster management is “the process of restoring, rebuilding, and reshaping the physical, social, economic, and natural environment through pre-event planning and post-event actions” (Smith & Wenger, 2007, p. 2372). Successful disaster recovery is vital for communities as it can help prevent adverse outcomes like loss of life, property, and livelihood (Rouhanizadeh et al., 20203), and foster future disaster resiliency (Demiroz & Hu, 20144). Despite the importance of successful disaster recovery, this phase has been described as the “neglected” component in disaster management (Rubin, 2009), and the least understood disaster management phase by both scholars and practitioners (Smith & Wenger, 2007).

One of the major barriers to studying disaster recovery is that there is no single agreed-upon definition of what constitutes “efficient and effective” recovery (Rubin, 2009). This is problematic for evaluating and, therefore, improving community disaster recovery. For example, the National Disaster Recovery Framework describes this phase as “a sequence of interdependent and often concurrent activities that progressively advance a community toward its planned recovery outcomes” (FEMA, 20165). These planned recovery outcomes imply that communities must identify their own measurable markers of recovery specific to their community, prior to a disaster occurring. This suggests that the definition of disaster recovery is inherently tied to how it might be identified. However, if it is difficult to define, it will be difficult to evaluate and improve, and it will inevitably be unique to each community.

One additional complicating factor in defining disaster recovery is that, as a process, it is experienced differently across different groups, suggesting that how disaster recovery is defined (and therefore evaluated) will also be different across different groups. Communities’ disaster recovery experience is inextricably linked to pre-disaster socio-economic and demographic conditions (Rivera et al., 20226). If there are historical disparities present before a disaster, these disparities could create uneven recovery processes, whereby some areas of a region recover faster than others, even accounting for severity of damage (see for example, Finch et al., 20107). For some groups, disaster recovery may simply include a return to the pre-disaster built environment; for other groups like those displaced for extended periods of time by disasters. The recovery process is complex and may involve socio-cultural restoration as well. For instance, following Hurricane Maria in 2017, many public schools in Puerto Rico were permanently closed in rural areas due to long-running demographic and economic challenges which were exacerbated by the natural disaster (Finucane et al., 20208). Thus, in addition to rebuilding public infrastructure and private structures, residents also had to navigate the post-disaster landscape of traveling further distances for educational services, suggesting the potential for more complex understandings of what constitutes disaster “recovery” among these communities.

Rural communities, in particular, experience recovery in different ways than their more urban counterparts (Caruson & MacManus, 20119). Paradoxically, rural communities tend to be more susceptible to natural disasters like floods, drought, and wildfires (Manuele & Haggerty, 202210), yet have smaller governmental structures, less diversified economies, and fewer financial reserves to handle disaster response and recovery than larger communities (Waugh, 201311; Kapucu et al., 201312). These communities often have pre-existing resource and capacity constraints (Jerolleman, 202013), such as few specialized emergency management and planning staff, impacting their ability to plan and prepare for disasters (Waugh, 2013). These capacity deficits are exacerbated when a disaster strikes, complicating the process of recovery, which generally requires new or adaptive capabilities.

Understanding how communities differentially experience, define, and evaluate disaster recovery is important for improving recovery outcomes and fostering future disaster resiliency, particularly in rural communities with higher vulnerability to and reduced capacity for managing disasters. One way of operationalizing the concept of disaster recovery into its more useful—and measurable—parts may be from a “community capitals'' perspective, wherein those resources, capacities, and networks necessary for recovery are “existing within several conceptually distinct domains: natural, built or physical, financial, human, social, cultural, and political” (Tierney & Oliver-Smith, 2012, p. 13514; Flora & Flora 200815; Ritchie & MacDonald, 201016). This Community Capitals Framework helps communities inventory their tangible and intangible assets and assess the potential impacts of disasters on those assets, or capitals (Goreham et al., 201717), as each of these capitals is necessary in disaster recovery (Tierney & Oliver-Smith, 2012). For instance, prior studies indicate that rural communities often receive less federal funding for hazard mitigation (Seong et al., 202218) and disaster recovery assistance (Downey, 201619) than urban areas. This suggests that how community capitals are developed and leveraged in rural areas are different than in more urbanized settings. The Community Capitals Framework is employed to explore local government officials’ perceptions of community disaster recovery and capacity needs to create actionable and understandable recommendations for fostering disaster resiliency.

Research Questions

To understand rural perspectives of disaster recovery and resiliency, this study seeks to discern the ways local officials in rural jurisdictions conceptualize whole-community recovery and resiliency to practically inform community planning and capacity-building efforts that other rural communities in the United States can use. This study, which is part of a larger project within the IA/PA counties under study, is guided by one central research question: what constitutes recovery for different community groups? Specifically, the questions explored through the local government study are:

1) How do local government officials across the disaster-impacted landscape conceptualize community recovery?

2) What do local government leaders believe is necessary to build future disaster and community resiliency?

These questions are designed to bring attention to local knowledge, unique opportunities, and ongoing challenges faced by rural government officials responsible for successfully leading their communities through disaster response and recovery, and toward future resiliency.

Research Design

This study incorporates a mixed-methods research design consisting of data collected with both a survey and interviews with local government officials across the four study counties. This investigation is part of a larger whole-community project that engages additional community members (small business owners, nonprofit organizations, and local residents). By exploring the perceptions and experiences of local government officials, this research design focuses on those having significant interaction(s) with the disaster response and recovery process, and those positioned to meaningfully influence community resiliency within municipal government.

This study utilizes a two-pronged approach to data collection. First, an electronic survey (hosted via Qualtrics) was broadly distributed to local government workers with publicly available email addresses. The surveys allowed for the development of a baseline understanding of local government workers’ perceptions of community recovery in the aftermath of the 2022 floods. In addition, widespread distribution of the survey provided identifying information linking the project to a flagship university in the state and informed community leaders about the intent of the project. In total, 321 unique email addresses were invited to participate in the survey. Notably, many of the areas within the study counties are unincorporated or dispersed, and official email contacts were unavailable or nonexistent. The analysis below includes data provided by 36 survey respondents which reflects the rural and sparsely populated nature of these communities.

The second prong of the research team’s approach to data collection involved semi-structured, qualitative interviews with local government workers. Interviewees were recruited through: (1) a secondary “anonymous raffle” form linked to the survey, into which participants were able to self-select; and (2) a direct email invitation sent by the research team (53 in total). The research team interviewed 15 individuals in 13 sessions; two interview sessions were group sessions consisting of two interviewees each.

This research design was employed for the purpose of collecting perishable data and cultivating trust as partners in this investigation. Qualitative interviews fostered relationship-building between the investigators and communities, adding richness to the data collected. Because the broader project draws inspiration from more community-engaged methodological approaches (see for example Wallerstein et al., 202020), it was essential to ensure the study design facilitated two-way dialogues whereby researcher engagement brings value to local communities.

Study Site and Access

This study region includes the four counties approved for both PA and IA: Carbon, Park, Stillwater, and Yellowstone. This area is located in south-central Montana, is home to two entrances to Yellowstone National Park (YNP): the North and Northeast Gates. Over 4.8 million people, more than four times the population of Montana, visited YNP during its record-breaking 2021 season, with a quarter of those visitors passing through the two entrances within the study region (National Park Service [NPS], 2022a21). That same year, spending by YNP visitors supported 8,736 jobs and infused $824 million into local economies (NPS, 2022b22). In addition to YNP, the region is rich in recreation and cultural amenities, mining and timber production, the state’s largest population center (Billings), and agricultural crops and livestock.

The study area covers approximately 9,295 square miles and is home to 201,358 people (U.S. Census, 202323). Most of the population resides within Yellowstone County (84%) generally, and the City of Billings (71%) specifically, further highlighting the overall rurality of the area (see Table 1). For comparison, the study area is 136 times the size of Washington D.C. with half a million fewer people.

Table 1. County, Population, and Income in Study Area

|

County |

Population |

Population per mi2 |

Per capita income (12 month) |

|

Carbon |

10,473 |

5.10 |

$37,557 |

|

Park |

17,191 |

6.10 |

$37,543 |

|

Stillwater |

8,963 |

5.00 |

$38,767 |

|

Yellowstone |

164,731 |

62.60 |

$38,186 |

The research team leveraged prior experience and expertise to gain site and participant access. Pre-existing relationships with members of the federal disaster workforce, transparent conversations with state emergency managers, and the research team’s practical expertise—in emergency management outside of the state of Montana, and community and economic development within the region, respectively—reduced several barriers to site and participant access.

Finally, the values of community-engaged research were fostered throughout this project. Prior use of community-engaged methodologies indicate that community resilience in disaster mitigation and recovery are powerfully informed by local ecological knowledge, community social capital, and place attachment (Afifi et al., 2020 24, Quinn et al., 202125). The research team was sensitive to the legacy of extractive research experienced by marginalized individuals and communities. While the distance between the study area and the institution with which the research team is affiliated is significant (more than 350 miles one way), the study design prioritized in-person conversations and travel to the impacted areas, demonstrating the team’s commitment to area communities and to fostering trust with participants. To further embed in the community, the research team offered participants a monetary token of appreciation in the amount of $25, which interview subjects were able to receive either as an electronic certificate or as a donation to a 501 (c) 3 local nonprofit/philanthropic organization of their preference. The decision to employ a monetary demonstration of commitment to included communities was catalyzed by the research team’s understanding of the economic and financial precarity of communities within the study region and desire to contribute to the region’s recovery in some small way.

In addition, communication with study communities remains ongoing, with the research team committing to return within four months to share initial analysis and findings, as well as seek corrections and additional guidance. Beyond the local government component of the larger IA/PA study, the research team is also undertaking two resident-focused projects that will help address the project’s overall research question. To benefit the study areas, the research team solicited topic areas of interest to local government officials that can be included in the resident projects, specifically for the benefit of study sites.

Data Collection Method: Survey

Survey Sampling Strategy

Because local government workers are public employees, the sampling strategy for the survey portion of this project began with the creation of a contact database. Through a search of government websites (including county, city or town, special district, etc.), e-mail addresses for local government workers were identified and entered contact information into our database. It is understood that individuals that occupy different positions within the same government have differential experiences of events, including disasters (e.g., Somers & Svara, 200926). Therefore, the research team intentionally cast a broad net when seeking survey participants. In total, 321 contacts were in the final database. Little standardization was present across the local governments within the study area; therefore, the research team elected to also employ a snowball sampling strategy. Those who were contacted were invited to forward the invitation to others in their organization or area local government(s).

Survey Measures

The 33-question survey Endnote 1 solicited local government workers’ perspectives of the 2022 flooding events; their understanding and experience with the federal emergency management response and recovery process; thoughts about equity in disaster recovery in their community; their vision for community resiliency in the future; and basic demographic information. A variety of question formats were deployed, including multiple choice and multiple response, Likert-scale, rank order, and open-ended questions. For questions that involved respondents assessing the level of importance or significance of several items on a list, items were randomly rotated to mitigate order effects and randomly distribute bias. For specific measures used in the analysis below, see Appendix B.

Survey Distribution

Initial survey distribution was conducted through e-mail invitations sent from University of Montana servers (i.e., an identifiable @umontana.edu e-mail address). Three invitations were sent over seven weeks (June 15, July 6, and July 31, 2023). In addition to e-mail invitations, the research team provided physical copies of the survey and half-page fliers (with a QR code linking to the survey) when interviewing participants, whether in-person or remotely.

Survey Participant Consent and Other Details

University of Montana IRB-approved consent language was presented within the e-mail recruitment and survey landing page. Before a respondent could access the survey, they were required to consent to participating in the study upon reading the approved information. Respondents were guaranteed anonymity to the degree the technology employed allowed. Respondents could also choose a non-response (prefer not to answer) to each survey question and, in the analysis reported below, the research team was attentive to the potential for breaching anonymity and confidentiality due to the area’s low population and unique identifiers. Therefore, limited personally identifiable information was requested beyond county of employment, general employment type (e.g., public health, emergency management, elected official, etc.), and select demographic questions. For categories with fewer than five observations, data were suppressed in the analysis.

Survey Sample

The sample included local government officials in the Montana counties of Carbon, Park, Stillwater, and Yellowstone. Roughly half of the respondents work for county government, with the other half employed by a city or town government. Respondents report a range of length of organizational membership, with the plurality of respondents (33%) having been with their organization for two –to five years, 14% having been in their job for more than 16 years, and one-fifth were in their first year. Respondents ranged in age from 26-79, with a median age of 50. Gender identification was evenly split between men and women, and most of the sample (94%) identify as white.

Data Analysis Procedures

Data were collected via Qualtrics and imported data into Stata 17. Observations containing missing data on key questions used throughout the analysis were removed (resulting almost entirely from a respondent exiting the survey prematurely, rather than systematic skipping of questions), leaving a sample size of 36 respondents. Descriptive statistics used in this report reflect the number of valid responses for each item (i.e., responses of “not applicable/prefer not to answer” are excluded from the analysis). No item used in the analysis included more than two “not applicable/prefer not to answer” responses, meaning each summary statistic is composed of no fewer than 34 observations. The research team utilized both inductive and deductive coding strategies to analyze open-ended survey responses. A priori coding employed themes related to the Community Capital Framework and are the same as those used in qualitative analysis of interview data (as described below). One member of the research team conducted initial coding of open-ended survey responses in Microsoft Excel. A second member of the research team recoded the data resulting in a consensus around the meaning of the responses.

Data Collection Method: Interviews

Interview Sampling Strategy, Recruitment, and Consent

To ensure representation from affected communities, interview sampling utilized two different strategies. First, all survey respondents were offered the opportunity to indicate whether they would be interested in talking further. If they were interested, respondents were asked them to provide contact information for further follow-up via an external website not linked to their survey responses. Second, potential interview subjects holding specific roles in local/municipal governments were identified in a quasi-quota approach and directly solicited those individuals to participate. In this context, quasi-quota sampling reflects the research team’s strategy for ensuring minimum representation of at least one city employee and one county employee in each study county. This sampling strategy enabled the research team to engage with at least one city and one county interview subject in each declared county. Given the small population and rural nature of the region, the sampling strategy was intentionally aimed to welcome any local government worker to share their story.

In addition to recruiting interviewees through the survey, the research team also reached out to local leadership across the four counties and associated communities to invite them to share their experiences and perspectives. Lastly, local/municipal officials responsible for the areas of emergency management, planning, public works, and finance were contacted to be interviewed. In total, 53 local government employees outside of survey recruitment methods were invited to participate.

The consent process began with interviewees opting in to participate. When interviewed, written consent from participants in person and verbal consent to audio record for transcription purposes from virtual participants was obtained. Through this process, the research team engaged in a conversation with subjects to build trust, including discussing the intent of the report, plans to return to discuss further iterations, and jointly planning future stages of the larger whole-community project.

Interview Sample

At least two local government employees (one representing the county and one representing the municipal government) were interviewed from each of the four counties approved for both IA/PA. These officials represented the areas of county/city administration and policy making, emergency management, public health, parks and recreation, planning, financial administration, and public works. Interviewees had either policymaking or decision-making authority in disaster response or were heavily involved in the administration of the PA program. Lastly, a local government official from the incident management team deployed to the area during the response to better understand the transition from response to recovery was interviewed.

Interview Guide and Setting

Interviews were semi-structured, which allowed for the co-creation of knowledge rather than direct transfer from interviewee to researcher (Luton, 201027). This back-and-forth between researchers and participants helped to enrich the quality of data and mutual sensemaking. Interviewees were asked about the impacts of the 2022 flood event to their community, their understandings of disaster recovery broadly, their perceptions of the 2022 flood recovery process, their community’s experience with navigating the federal recovery process, and perceived capacities their community might need for future resiliency. Additionally, to ensure respondents were not overly burdened by the data collection process, interviews were predominantly held in the respondents’ local communities and in locations suggested by interviewees. Of the 15 interviews, nine were held on-site, with three interviews occurring via Zoom and one via telephone, based on respondent preference.

Data Analysis Procedures

All interview participants consented to audio recording. Upon completion of the interviews, audio files were transferred to the Sonix automated transcription server. Each individual recording was transcribed by Sonix and cleaned by the research team. Three members of the research team, including the two individuals that conducted the interviews, met to discuss the coding schema. Working collectively during the analysis process is an important measure to ensure accuracy and trustworthiness of the data (Tracy, 201328). The researchers worked together throughout the data analysis process to discuss the codes and achieve agreement on the themes and meaning of the data. The resulting codebook included both a priori and emergent codes: for the purposes of this study, codes primarily derived from Gill and Ritchie’s (201429) community capital work and codes based on recovery and resiliency themes which emerged during the data collection and analysis processes were employed. In presenting the findings, the research team employs direct quotations and thick descriptions to promote the openness and accuracy of these findings (Tracey, 201830).

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

Community-engaged research approaches seek to co-create useful results for local communities, and therefore it was vital that the early phase of the larger project ascertain the key challenges and potential capacities needed from the perspective of those charged with facilitating recovery and creating future resiliency. While the larger whole-community study encompasses other community groups, the first phase of the project began with discussions with local government officials, or those individuals that were best positioned to speak to the community’s official recovery process because of their formal roles and statutory authority. To lessen the burden of study participation, members of the research team traveled to the study area to engage with communities directly.

This flood event was undeniably traumatic for those who experienced it. Therefore, it was important for the researchers to acknowledge this trauma throughout the research design, data collection, and analysis. To minimize further trauma, efforts were made to build trusted relationships with participants by treating their experiences with compassion and ensuring full transparency in how the data would be used and their stories shared.

Reciprocity

As this study is part of a larger participatory action project that explores the conceptualizations of whole-community recovery and disaster resilience across rural communities in Montana impacted by the June 2022 flooding events, findings described herein are limited to those related to the specific research questions presented above. Additionally, a key tenet of community-engaged research approaches that differ from more traditional research is how findings are presented and communicated. Rather than extracting data, analyzing it, and presenting it in academic manuscripts, this approach positions findings as an ongoing discussion with community partners, an often-overlooked stage of this research methodology (Macaulay et al., 200731). Therefore, this report represents just one early piece of ongoing exploration wherein collective sensemaking and analysis will continue as the whole community study progresses.

Findings

Conceptualizing Recovery

The Community Capitals Framework is employed as a strategy for organizing and understanding local government perspectives of recovery. A primary emphasis of this study is on how local government employees conceive of the concept of recovery. Interviewees were asked to define this concept in their own words, revealing several key dimensions of the concept of disaster recovery.

First, respondents often described recovery as either a restoration of pre-disaster conditions (“back to normal”), or in terms of the development of some new, improved state that would help the community be better prepared for future disasters. A large majority of interviewees described recovery in terms of “back to normal,” with the following quotation exemplifying this conceptualization: “…So, I think the period of recovery is that attempt to return to normalcy after the event or the immediate disaster kind of subsides…” (Interviewee 12, County 2). In contrast, a minority of interviewees described disaster recovery as containing an element of mitigation for future disasters, as illustrated by this interviewee:

"Recovery is also not just getting back to the way it used to be, but also being more resilient…I think recovery also is again, resiliency, but using more nature-based resources solutions and not just manmade, forcing the river to do what we want it to do" (Interviewee 6, County 1).

A second dimension to interviewees’ conceptualizations of recovery revolved around the tangible indicators used to describe and define recovery. Upon coding the qualitative interview data for community capitals (Gill & Ritchie, 2014), the built environment (built capital) is referenced near universally by subjects’ descriptions of disaster recovery. Notably, six interviewees described recovery solely in terms of the built environment. One interviewee noted:

"In my view, recovery is getting our infrastructure back to the position it was in prior to the event…And again, going back to, in my view, people made whole - like if you lost a water heater or a power box or something like that, if you have it back, in my view, you're recovered. Those impacts that were made during the event, when they are made whole again, that's when recovery happens." (Interviewee 5, County 1)

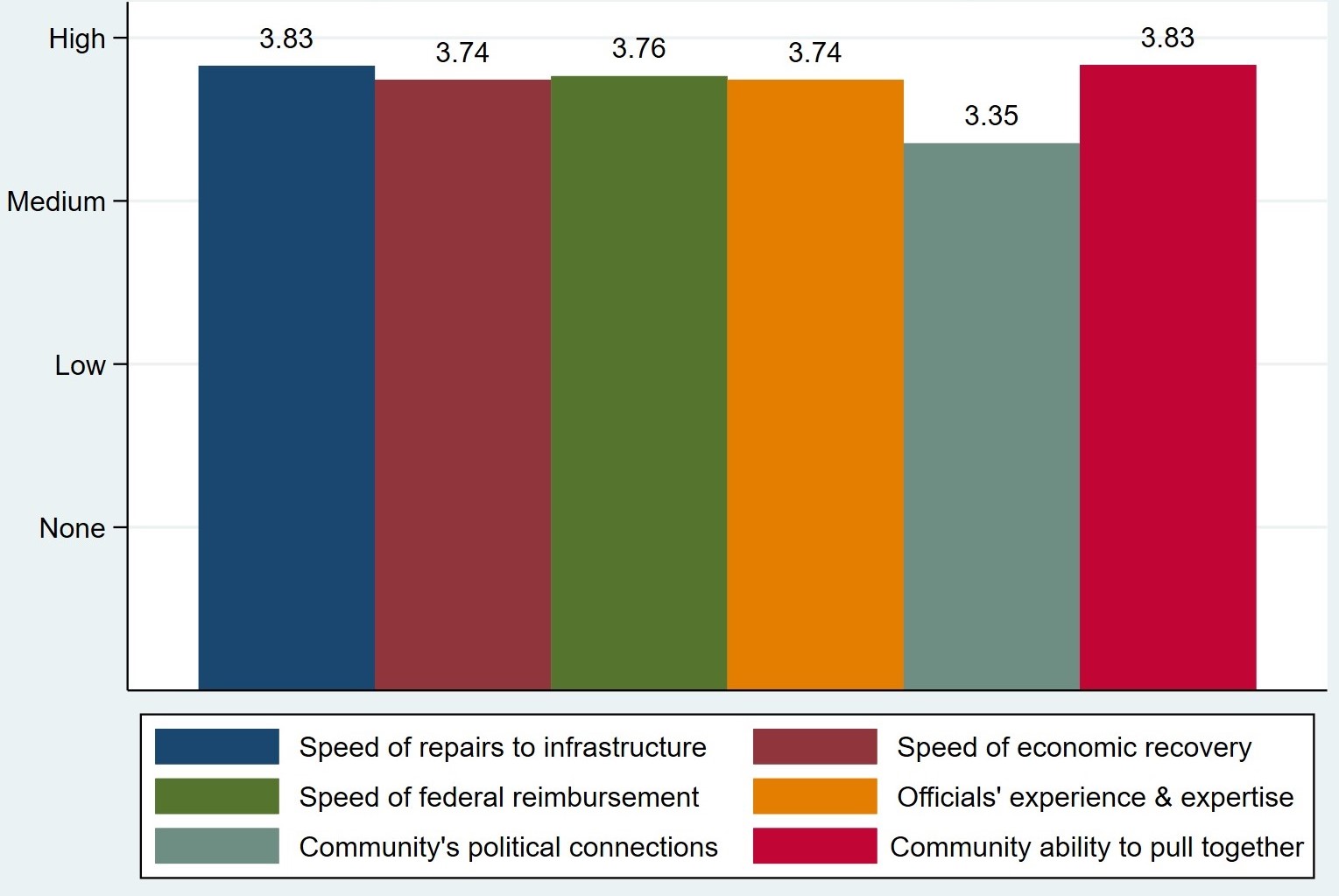

These qualitative findings complement those solicited via survey. Survey respondents were asked to rate the importance of a series of factors identified by prior studies as important to disaster recovery to their community’s recovery from the 2022 flood event (Nakagawa & Shaw, 200432; Tierney & Oliver-Smith, 2012; Goreham et al., 2017). While not describing recovery itself, respondents did indicate what was most important to the recovery process from a recent event. While not describing recovery itself, respondents did indicate what was most important to the recovery process from a recent event.

Figure 1. Factors Important to Disaster Recovery by Local Government Employees

As depicted in Figure 1, there is minimal variation in the degree of importance survey respondents place upon each recovery factor, with the means of all six items indicating above-medium importance (3.35-3.83 on a four-point scale). Respondents identified the speed of infrastructure repairs— a measure of built capital—as highly important (3.83 on a four-point scale). Survey participants also noted that social capital, or the community’s ability to pull together, is equally important to built capital in recovery. Other factors, including the speed of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reimbursement for federal aid and the speed of economic recovery in the community (financial capital) and local officials’ prior experience in disaster management (human capital), were of high importance; however, as aforementioned little variation in respondent perceptions was present.

Qualitative data also suggests the importance of community capitals beyond the built environment in recovery. Interviewees noted financial, natural, and social capital in their depictions of recovery, albeit less often than built capital. For instance, in the following comment, a respondent describes recovery simultaneously in terms of the built environment (homes), natural landscape (riverside acreage), and financial restitution (recouped taxpayer expenditures), linking three different community capitals:

"Disaster recovery is just trying to get back to that sense of normal, in an aspect. And we're never going to return everybody's life to normal, right? Like we lost houses that lost all their property and they're not going to get that property back. The river shifted. I mean, they can't rebuild. You know, you talk about people that had an acre. Now they have 12 feet...But then it's also making sure that the taxpayers aren't on the hook to replace that public infrastructure as much as we can." (Interviewee 1, County 3)

Findings from the survey and interviews suggest that local government study participants primarily conceptualize disaster recovery as a return to normal pre-disaster conditions, specifically regarding the built environment. Notably, disaster recovery definitions are not homogenous across the region. Some local government officials connect recovery efforts with creating future resilience and community capitals other than built capital.

Future Capacity Needs for Community Resiliency

The second major focus of this study explored local government workers’ perceptions of community capacity deficits in need of remediation to facilitate future disaster resiliency. The purpose of this focus on perceived capacity deficits was to directly inform actionable recommendations for the emergency management community. To address this second research question, quantitative and qualitative data related to respondents’ perceptions of barriers to the 2022 flood recovery and future community capacity needs for fostering disaster resiliency were collected.

Participants were asked to reflect on the major barriers to recovery from the 2022 flood. Both interview participants and survey respondents cited problems related to interfacing with various levels of government as a major barrier to recovery. Several open-ended survey responses noted issues related to communication with FEMA and other federal and state agencies; bureaucratic procedures preventing timely action and progress; complexities in knowing and following the processes required for federal reimbursement; and capacity issues, ranging from the availability of equipment and contractors to a lack of funding and workers.

Interviewees similarly noted these challenges, with roughly half of respondents citing the difficulties in navigating the federal disaster assistance process as a major barrier to recovery. The following comment from an interviewee illustrates this sentiment:

"So, trying to figure out which is the best way on the public infrastructure side so that we don't jeopardize taxpayer dollars, we took the more conservative route. We're going to make sure all the boxes are checked before we ever put a single piece of dirt in the ground…so there was that time frame, that time lag in that process. It took a lot longer than we would have liked to… (Interviewee 1, County 3)

Outside of this consistent challenge, participants cited a broad number of other factors as barriers. Survey respondents pointed to problems acquiring necessary resources and funding for disaster relief. Some officials who reported having access to resources, but insufficient knowledge of how to prioritize their distribution within the community, compounded these issues. Interviewees also noted challenges with navigating the floodplain permitting process; overall coordination between local, state, and federal agencies; and the need for greater leadership capacity as major barriers to the 2022 flood recovery.

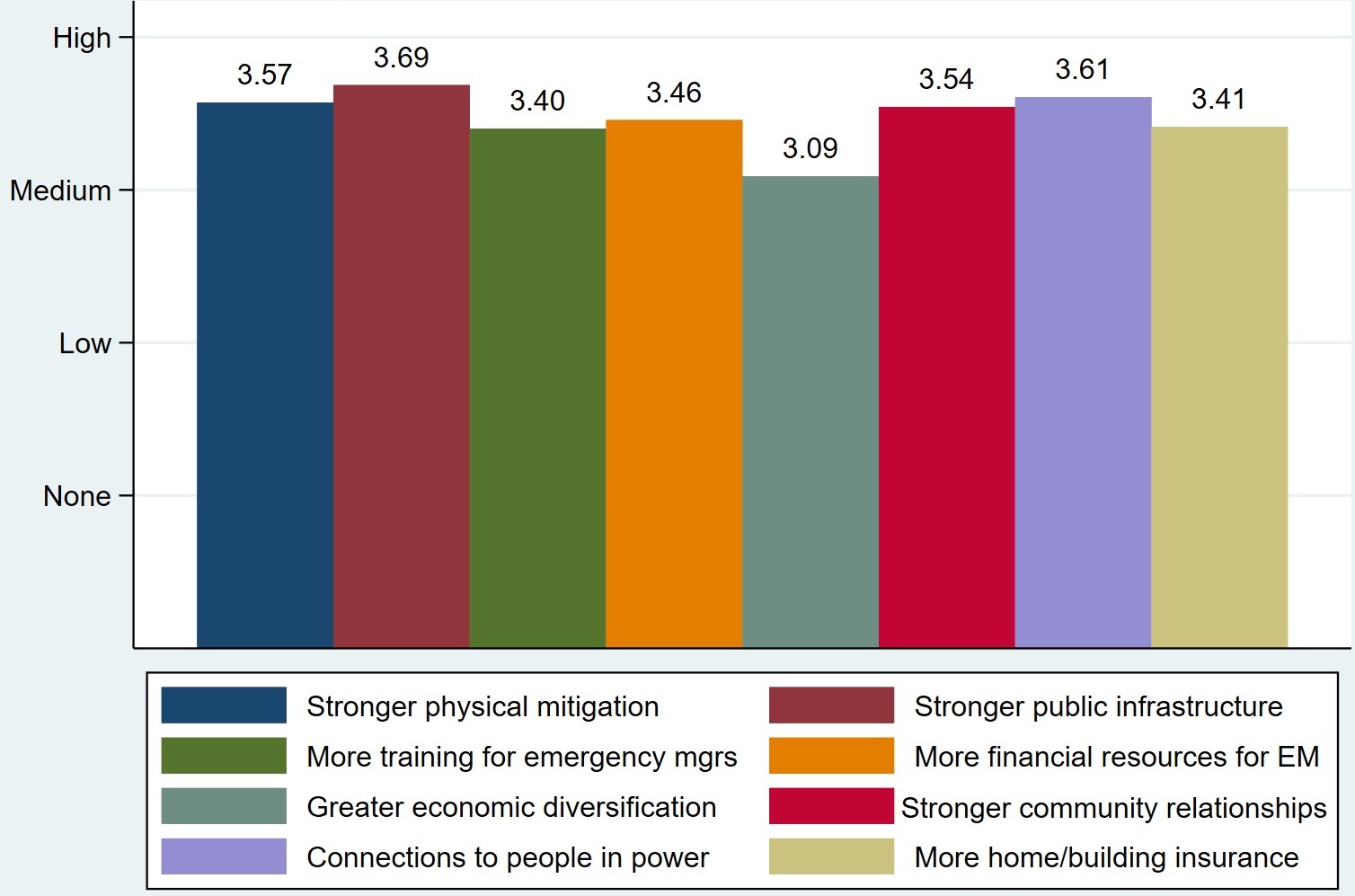

In addition to questions about barriers to this recovery event, participants were asked about their communities’ future disaster needs or capacities that would help strengthen future disaster resiliency. Depicted in Figure 2, survey respondents again placed high emphasis on all eight potential resiliency needs listed within the survey, with little variation among response categories. On average, they placed the most importance on strengthening public infrastructure (e.g., roads, utilities, wastewater) for building community resilience. The economic diversification of the community was viewed as the least important of the eight options, though this still had a relatively high mean score of 3.09. Like the data presented in Figure 1, minimal variation is present across respondents’ perceptions of what is needed for their communities to be resilient to future disasters.

Figure 2. Local Officials’ Perceptions of Needs for Future Disaster Resiliency

While interviewees cited concerns for hardening the built environment, such as reducing structures in floodplains, the most prominent future need related to human capital. Of the 15 interviewees, 10 noted the need for greater capacity in areas such as local government staffing, improved training for managers, and specialized post-disaster contractors. The following comment exemplifies this perception:

"We have a finite number of resources here in [community] and trying to find that balance of what we can do in-house versus what we have to do to contract it out. I think we have a finite number of civil excavators, electricians, and then we have, with our staff, we still have a [community] to operate and maintain that is growing and developing at unprecedented rates." (Interviewee 8, County 2)

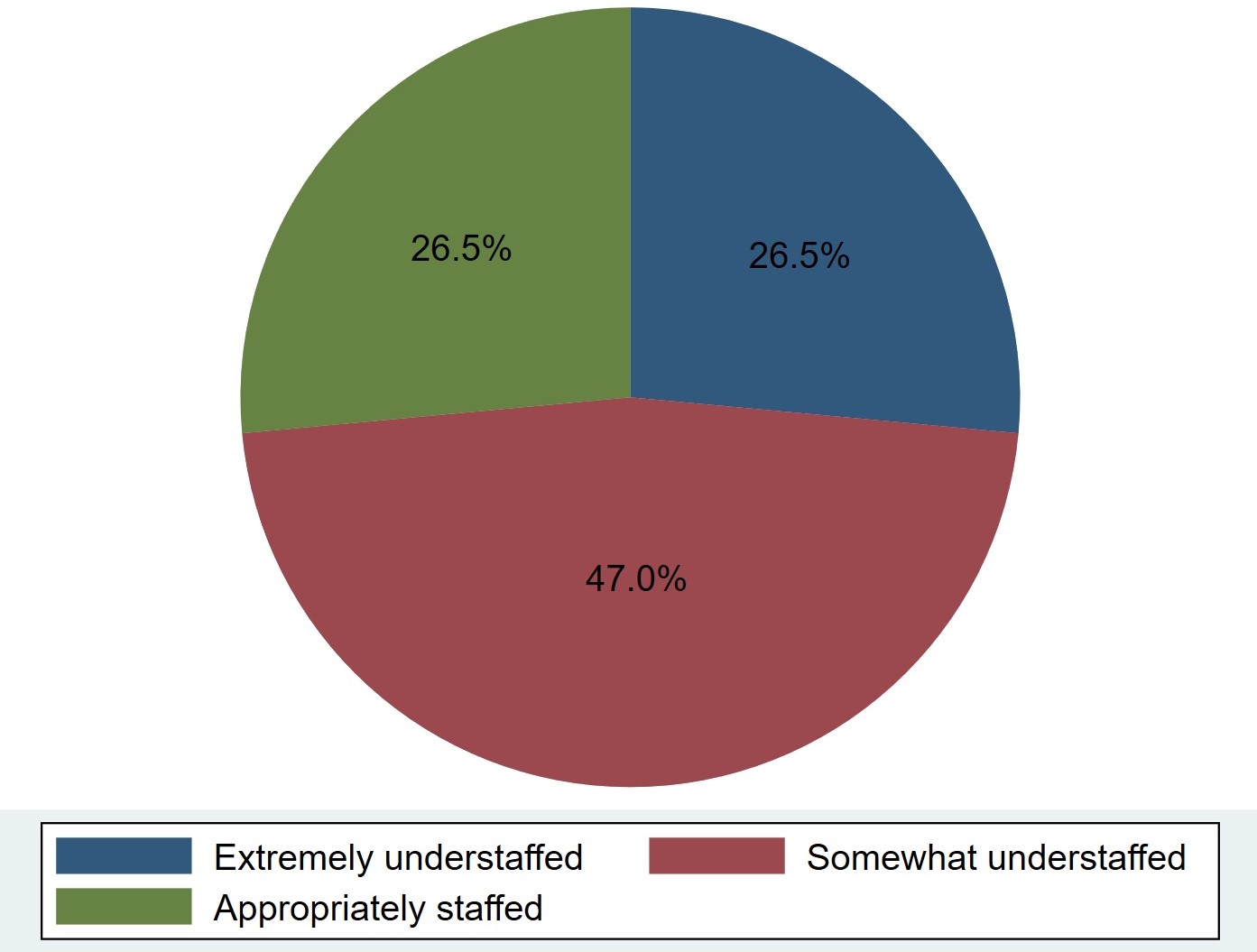

This sentiment dovetails with results from the survey, which suggest a staffing crisis in local government in terms of the workforce required to effectively respond to the 2022 Yellowstone Flood. As shown in Figure 3, approximately three-fourths of respondents reported their office as being at least somewhat understaffed, while no one viewed their department as having “more than enough” people to effectively respond to the emergency. Furthermore, only 11% of respondents reported their organization hiring new staff to aid in flood response, and typically only one-two new personnel. This, in part, likely contributed to 40% of respondents reporting a moderate to severe change in their day-to-day activities resulting from the flood recovery effort.

Figure 3. Officials’ Perceived Capacity to Respond and Recover From 2022 Flood

These findings suggest that while local government officials in these rural communities perceive interorganizational collaboration—particularly regarding navigating the federal disaster recovery assistance process—as a challenge to effective disaster recovery. Officials also note the need for future capacity beyond just hardening the built environment, identifying the need to strengthen human capital to foster future resiliency. Consensus around, and relative importance of, what local government officials perceive as crucial for future disaster recovery and necessary for resiliency highlights the precariousness of rural communities. In sum, if all factors are deemed essential, little capacity exists for sustainable adaptation in emergency situations.

Discussion and Implications for Practice

This study explores the ways in which rural local government officials conceptualize disaster recovery and what they perceive as needed for building future community disaster resiliency. Findings indicate that study participants predominantly consider recovery to be related to restoring the built environment, such as public infrastructure, buildings, and humanmade structures. However, considerations for other dimensions of recovery are present, and participants also recognize that recovery may also mean building back in ways that create future disaster resiliency. Additionally, study participants consistently perceived the process of navigating federal disaster assistance programs to be a barrier to recovery and cited widespread future capacity needs, but most frequently referenced human capital capacity as needed for future disaster resiliency. It is anticipated that as additional components of the whole-community project are undertaken that different community groups may offer new perspectives to community recovery and resiliency.

Due to their position in local government, and the responsibilities of these governments, it is unsurprising that participants in this study highlighted public infrastructure. At the same time, when they spoke about their own personal experiences of the flood (removing their “public official hat”), study participants offered insight into the psychological toll of the disaster. Previous work details that public workers who take part in disaster response encounter “heavy burden[s] on their bodies and minds” (Kashiwazaki, et al., 2022, p. 133). The Field Manual for Mental Health and Human Service Workers in Major Disasters identifies human service and disaster relief workers as groups at risk of experiencing adverse mental health impacts as a result of a disaster, noting that local public workers experience “considerable demands to meet the needs of the survivors and the community” (DeWolfe, 2000, p. 2334). It is important to remember that local public employees hold key roles not only during disaster response and recovery, but, across the disaster-impacted landscape, are also victims. For future resiliency, preventative strategies for managing the stress and psychological impacts of disasters at both the individual and organizational level should be adopted (DeWolfe, 2000). Clear, unimpeded administrative processes, reporting relationships, and access to resources can improve future disaster response and recovery and may relieve some of the stress experienced by local government officials in their identities as public workers and disaster victims.

A key takeaway from this study is the importance of investing in rural community disaster recovery capacity prior to disaster events. Though the built environment factored predominantly into their conceptualization of recovery, study participants clearly indicated inadequate levels of staffing and financial resources as problems to solve prior to the next disaster recovery process. This is especially important for rural communities, which have more acute staffing and resource constraints and little experience navigating federal disaster response and recovery systems. To foster future disaster resiliency in rural regions, it is important for community and disaster managers to identify avenues for amplifying this capacity before an actual recovery event. One potential way of addressing this deficit is through pre-disaster recovery planning. Pre-disaster recovery planning, though a relatively new area of academic study (Olshansky et al., 201235) is increasingly recognized as a vital and proactive step that can make recovery more efficient and effective once disaster strikes (Shaw, 201336). Additionally, effective and inclusive pre-disaster recovery planning can mitigate future hazards and increase community resiliency (FEMA, 201737). Yet, such planning capacity is not uniformly distributed across jurisdictions. To improve rural disaster recovery and resiliency, therefore, it is recommended that federal and state resources be directed towards fostering pre-disaster recovery planning capacity in these communities.

A second key takeaway from this study is that local government officials perceived interagency coordination and communication as problematic during the federal disaster recovery assistance process. Participants consistently described the processes of financial reimbursement, compliance with complex administrative regulations (which vary by agency and may conflict), and other interactions with federal and state authorities as cumbersome, complex, and frustrating. Notably, participants also expressed concerns that improper coordination could exacerbate recovery efforts by delaying repairs and remuneration during a time of crisis within communities, creating the potential for future damage if repairs are not completed before the next flood season begins or disaster strikes. Therefore, increasing and improving interorganizational collaboration is essential for fostering more efficient disaster recovery for these communities in the future.

Local community challenges with navigating federal disaster management programs is not a new phenomenon (see, for example, Smith & Vila, 202038). The ability to understand and successfully navigate complex bureaucratic rules, processes, and behaviors known as administrative capital (Masood & Nisar, 202139). Though not included in the Community Capitals Framework, this study points to the importance of administrative capital in rural communities’ disaster recovery experiences. One way to increase rural administrative capacity post-disaster is to rely on assistance from communities with more experience in navigating disaster recovery systems. While emergency management agreements between communities and states are common in disaster response (see, for example, Kapucu et al., 200940), findings from this study indicate that it is the recovery phase that may be overlooked through these arrangements. Therefore, it is recommended that as part of the pre-disaster recovery planning process, rural communities consider the long-term administrative capacity burdens of navigating multiple independent bureaucratic systems while also managing day-to-day community operations with already limited staff. Such pre-disaster consideration could include identifying potential collaborative arrangements or contracts with other jurisdictions or organizations for obtaining necessary extended administrative assistance before disaster strikes.

Conclusion

Recovery and resiliency are fundamental concepts in disaster management. The increasing frequency of climate-related disasters necessitates a fuller understanding of how communities define recovery, as well as potential barriers to building resilience, particularly in rural areas which may be uniquely vulnerable (Lal et al., 201141). Disaster recovery is a phenomenon that is experienced acutely and individually, and therefore may be experienced (Duffy & Shaefer, 202242) and defined (Tierney & Oliver-Smith, 2012) differently across different groups. The findings from this study demonstrate the value of working with rural communities to understand their unique challenges and diverse needs in disaster recovery, as no one-size-fits-all approach is appropriate (Cutter et al., 201643). Importantly, this study offers insight to the opportunities and strengths within rural communities – future discussion of which may provide lessons for practitioners across rural and urban jurisdictions alike.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study focused on the experiences and perspectives of local government officials in four disaster-impacted Montana counties following a flood event. As such, the findings reported above may not be generalizable across all communities and disasters. Socio-economic, geographic features and isolation, cultural understanding, and degree of experience, among other factors, vary across the study area and may influence differential experiences and perceptions. Additional research exploring disaster recovery and resiliency in rural communities following different types of disasters can potentially add to the knowledge and understanding of these experiences and inform future processes. Future research should explore experiences and conceptualizations of recovery following disasters other than flood events, as recovery is different in the context of other weather-related events, like wildfire or blizzards. Whatever the direction, future research should be a reciprocal partnership with communities so that local knowledge is incorporated, and findings provide actionable information to the places where the research is undertaken.

Acknowledgements

This project would not be possible without the public servants who gave generously of their time and entrusted us with their experiences. We thank our partners at the University of Montana’s Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research for their support of the greater whole-community project. The Quick Response Research Award Program is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF Award #1635593). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or Natural Hazards Center.

Endnotes

Endnote 1: The survey employed display logic whereby respondents’ answer selections determined the question(s) displayed. Depending on their answer selections, survey respondents were shown between 28 and 32 questions total. ↩

References

-

Rubin, C. B. (2009). Long term recovery from disasters – The neglected component of emergency management. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 6(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1616 ↩

-

Smith, G. P., & Wenger, D. (2007). Sustainable disaster recovery: Operationalizing an existing agenda. In H. Rodriguez, E. L. Quarantelli, & R. R. Dynes (Eds.) Handbook of Disaster Research (pp. 234-257). Springer. ↩

-

Rouhanizadeh, B., Kermanshachi, S., & Nipa, T. J. (2020). Exploratory analysis of barriers to effective post-disaster recovery. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 101735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101735 ↩

-

Demiroz, F., & Hu, Q. (2014). The role of nonprofits and civil society in post-disaster recovery and development. In N. Kapucu & K. T. Liou (Eds.) Disaster and Development (pp. 317-330). Springer Cham. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (2016). National Disaster Recovery Framework (2nd Ed.). Department of Homeland Security. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/national_disaster_recovery_framework_2nd.pdf ↩

-

Rivera, D. Z., Jenkins, B., & Randolph, R. (2022). Procedural vulnerability and its effects on equitable post-disaster recovery in low-income communities. Journal of the American Planning Association, 88(2), 220-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2021.1929417 ↩

-

Finch, C., Emrich, C. T., & Cutter, S. L. (2010). Disaster disparities and differential recovery in New Orleans. Population and Environment, 31(4), 179-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11111-009-0099-8 ↩

-

Finucane, M. L., Acosta, J., Wicker, A., & Whipkey, K. (2020). Short-term solutions to a long-term challenge: rethinking disaster recovery planning to reduce vulnerabilities and inequities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020482 ↩

-

Caruson, K., & MacManus, S. A. (2011). Gauging disaster vulnerabilities at the local level: Divergence and convergence in an “all-hazards” system. Administration & Society, 43(3), 346-371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399711400049 ↩

-

Manuele, K. & Haggerty, M. (2022, October 6). How FEMA can build rural resilience through disaster preparedness. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-fema-can-build-rural-resilience-through-disaster-preparedness/ ↩

-

Waugh, W. L. (2013). Management capacity and rural community resilience. In N. Kapucu, C. V. Hawkins, & F. I. Rivera (Eds.), Disaster resiliency: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 291-307). Routledge. ↩

-

Kapucu, N., Hawkins, C. V., Rivera, F. I. (2013). Disaster preparedness for rural communities. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 4(4), 215-233. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12043 ↩

-

Jerolleman, A. (2020). Challenges of post-disaster recovery in rural areas. In S. Laska (Ed.), Louisiana’s Response to Extreme Weather: A Coastal State’s Adaptation Challenges and Successes (pp. 285-313). Springer Cham. ↩

-

Tierney, K., & Oliver-Smith, A. (2012). Social dimensions of disaster recovery. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 30(2), 123-146. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072701203000210 ↩

-

Flora, C. B. & Flora, J. L. (2008). Rural communities: Legacy and change (3rd Edition). Westview Press. ↩

-

Ritchie, L. A. & MacDonald, W. (2010). Enhancing disaster and emergency preparedness, response, and recovery through evaluation. Special issue: Enhancing disaster and emergency preparedness, response, and recovery through evaluation, 126, 3-7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.325 ↩

-

Goreham, G. A., Bathke, D., Gill, D., Klenow, D., Koch, B., Mantonya, K., Mueller, A., Norr, K., Paul, B. K., Redlin, R, & Wall, N. (2017). Successful disaster recovery using the community capitals framework: Report to the North Central Regional Center for Rural Development. https://www.ndsu.edu/fileadmin/socanth/Natural_Disaster_Recovery/Chapter_1_Introduction__2_.pdf ↩

-

Seong, K., Losey, C., & Gu, D. (2022). Naturally resilient to natural hazards? Urban-rural disparities in Hazard Mitigation Grant Program assistance. Housing Policy Debate, 32(1), 190-210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2021.1938172 ↩

-

Downey, D. C. (2016). Disaster recovery in black and white: A comparison of New Orleans and Gulfport. American Review of Public Administration, 46(1), 51-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014532708 ↩

-

Wallerstein, N., Oetzel, J. G., Sanchez-Youngman, S., Boursaw, B., Dickson, E., Kastelic, S., Koegel, P., Lucero, J. E., Magarati, M., Ortiz, K., Parker, M., Pena, J., Richmond, A., & Duran, B. (2020). Engage for equity: A long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 380-390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198119897075 ↩

-

National Park Service (NPS). (January 21, 2022A). Yellowstone 2021 visitation statistics. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/news/22003.htm ↩

-

National Park Service (NPS). (June 29, 2022B). Tourism to Yellowstone creates $834 million in economic benefits; Report shows visitor spending supports 8,736 jobs in local economy. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/news/220629.htm ↩

-

U.S. Census. (2023). QuickFacts. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/MT/PST045222 ↩

-

Afifi, R. A., Abdulrahim, S., Betancourt, T., Btedinni, D., Berent, J., Dellos, L., Farrar, J., Nakkash, R., Osman, R., Saravanan, M., Story, W. T., Zombo, M., & Parker, E. (2020). Implementing community-based participatory research with communities affected by humanitarian crises: The potential to recalibrate equity and power in vulnerable contexts. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66(3-4), 381-391. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12453 ↩

-

Quinn, T., Adger, W. N., Butler, C., Walker-Springett, K. (2021). Community resilience and well-being: An exploration of relationality and belonging after disasters. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(2), 577-590. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1782167 ↩

-

Somers, S. & Savara, J. H. (2009). Assessing and managing environmental risk: Connecting local government management with emergency management. Public Administration Review, 69(2), 181-193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.01963.x ↩

-

Luton, L. S. (2010). Qualitative Research Approaches for Public Administration. M.E. Sharpe, Inc. ↩

-

Tracy, S. J. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. John Wiley & Sons. ↩

-

Gill, D. A. & Ritchie, L. A. (2014). Assessing social impacts of energy development on the Gitga’at First Nation. HazNet, 5(2), 46-51. http://haznet.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/HazNet-vol.-5-no.-2.pdf ↩

-

Tracey, S. J. (2018). A phronetic interpretive approach to data analysis in qualitative research. Journal of Qualitative Research, 19(2), 61-76. https://doi.org/10.22284/qr.2018.19.2.61 ↩

-

Macaulay, A., Salsberg, J., Ing, A., McGregor, A., Rice, J., Montour, L., Saad-Haddad, C., & Gray-Donald, K. (2007). Community-Based Participatory Research: Lessons from sharing results with the community: Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 1(2), 143-152. http://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2007.0010 ↩

-

Nakagawa, Y., & Shaw, R. (2004). Social capital: A missing link to disaster recovery. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 22(1), 5-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072700402200101 ↩

-

Kashiwazaki, Y., Matsunaga, H., Orita, M., Taira, Y., Oishi, K., & Takamura, N. (2022). Occupational difficulties of disaster-affected local government employees in the long-term recovery phase after the Fukushima nuclear accident: A cross-sectional study using modeling analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3979. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph19073979 ↩

-

DeWolfe, D. (2000). Field manual for mental health and human service workers in major disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency ↩

-

Olshansky, R. B., Hopkins, L. D., & Johnson, L. A. (2012). Disaster and recovery: Processes compressed in time. Natural Hazards Review, 13(3), 173-178. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000077 ↩

-

Shaw, R. (2013). Post disaster recovery: Issues and challenges. In R. Shaw (Ed.) Disaster recovery: Used or misused development opportunity. Springer ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (2017). Pre-disaster recovery planning guide for local governments. Department of Homeland Security, FEMA Publication FD 008-03. ↩

-

Smith, G., & Vila, O. (2020). A national evaluation of state and territory roles in hazard mitigation: Building local capacity to implement FEMA hazard mitigation assistance grants. Sustainability, 12(23), 10013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310013 ↩

-

Masood, A., & Azfar Nisar, M. (2021). Administrative capital and citizens’ responses to administrative burden. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 31(1), 56-72. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa031 ↩

-

Kapucu, N., Augustin, M. E., & Garayev, V. (2009). Interstate partnerships in emergency management: Emergency management assistance compact in response to catastrophic disasters. Public Administration Review, 69(2), 297-313. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27697865 ↩

-

Lal, P., Alavalapati, J. R., & Mercer, E. D. (2011). Socio-economic impacts of climate change on rural United States. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 16, 819-844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-011-9295-9 ↩

-

Duffy, M., & Shaefer, H. L. (2022). In the aftermath of the storm: Administrative burden in disaster recovery. Social Service Review, 96(3), 507-533. https://doi.org/10.1086/721087 ↩

-

Cutter, S. L., Ash, K. D., & Emrich, C. T. (2016). Urban-Rural differences in disaster resilience. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 106(6), 1236-1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2016.1194740 ↩

McKeague,L.K., Barsky, C.S., Hazelton-Boyle, J.K. & Emidy, M.B. (2023). Making Us Whole Again? Lessons From Montana Disaster Recovery (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 359). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/making-us-whole-again