Post-Wildfire Damage

The 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, California

Publication Date: 2021

Abstract

With the continued increase in frequency and intensity of wildfires in the western United States, risk to wildland-urban interface (WUI) communities is on the rise. In 2018, California’s most destructive wildfire, the Camp Fire, completely destroyed the majority of the town of Paradise, burning homes, commercial buildings, schools, and hospitals. Our team conducted two reconnaissance trips to Paradise to collect data through visual observations, lidar, drones, street map data, and interviews to accomplish five main goals: (1) document and measure the damage to critical facilities due to WUI fire impacts of the Camp Fire, (2) document and assess the success of mitigation strategies implemented before the Camp Fire to protect critical infrastructure from the impact of WUI fires, (3) document strategies being planned or already implemented after the Camp Fire for mitigation and prevention of impacts in the future, and (4) assess the impacts of healthcare and educational service shortages due to damages in Paradise on the displaced population and on facilities in the surrounding regions. The results of this data collection provided empirical data for the research team to determine mitigation methods that were implemented at schools and hospitals, quantifying the damage to the buildings of the schools and hospitals, and performing qualitative analysis on interviews that support the findings concluded through quantitative building analyses. The data will be used in future research to create damage and functionality assessment criteria for wildfires, compare damages between multiple hazard types, and learn how the Camp Fire recovery process can enhance resilience for future hazards.

Introduction

On November 8, 2018, a wildfire, later known as the Camp Fire, started east of Chico, California. The fire started in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and developed in intensity and size quickly, engulfing all of Paradise, California in just six hours (Cal Fire Progression Map, 20181). Residents were meant to evacuate by zones to avoid heavy traffic, but due to phone communication failures and the challenge of a fast-moving fire, chaos ensued, and evacuation out of Paradise became a large traffic jam. The fire left the community devastated, with a total of 86 deaths, mostly from the older population. The Camp Fire caused damage to 18,804 buildings throughout Paradise and the surrounding communities, including homes, businesses, hospitals, and schools (Cal Fire, 20192).

Communities are encroaching on wildland fire hazard regions as urban areas are expanding, and as remote and wild landscapes become more appealing and available for residential development. Approximately one-third of all residents in the United States live in a wildland-urban interface (WUI), defined as an area where forested land intersects and intermingles with infrastructure and communities. The occurrence of wildland fires has increased in the western United States in the past decade, with no signs of diminishing (Radeloff et al., 20183). In particular, the same area that the Camp Fire impacted has been burned by 13 large wildfires in the last 20 years (Gafni, 20184). WUI communities have a higher risk of wildfire hazards due to a build-up of fuels resulting from past wildfire suppression policies in addition to rising temperatures as a result of a changing climate (Schoennagel et al., 20175).

Damage to residential structures caused by wildfire has a direct impact on residents living in the WUI. Victims of wildfires often suffer from mental health challenges like trauma as a result of displacement and complete loss of their housing and other belongings. Damage to schools and other care facilities impacts the broader communities in multiple ways. For example, the sense of community, familiarity, and routine that schools provide for children and families is lost. In addition, people who have lost their homes in the fires do not have access to schools and healthcare facilities that often provide relief for parents and families as they restore emotional health and stability after disasters. Decisions made by and for children after the bush fires in Australia reflect the need for restoration of routine and familiar social and physical environments (Gibbs et al., 20156). Recovering these facilities as soon as possible is an important step for rebuilding communities after large losses from these kinds of disasters.

Information collection and building evaluations were performed in Paradise, CA during two reconnaissance missions. This work, funded by the Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Grant and a National Science Foundation (NSF) RAPID grant, examined the mitigation for wildfire around schools and hospitals in Paradise and qualitatively assessed the effect of the closure of these critical facilities on the community and facilities in surrounding communities. The goals of this reconnaissance project are to: (a) document and measure the damage to critical facilities due to WUI fire impacts of the Camp Fire, (b) document and assess the success of mitigation strategies implemented before the Camp Fire to protect critical infrastructure from the impact of WUI fires, (c) document strategies being planned or already implemented after the Camp Fire for mitigation and prevention of impacts in the future, and (d) assess the impacts of healthcare and educational service shortages due to damages in Paradise on the displaced population and on facilities in the surrounding regions.

This report first reviews research on damages from previous WUI fire hazards. The authors then summarize the damages observed to schools, hospitals, and commercial buildings in Paradise. Interviews with facility administrators revealed the extensive impact the structural damage has had on the community members and operations of key community facilities. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of this research and findings, and the essential role schools and hospitals play in the recovery of a community, the authors will highlight future areas of investigation they will focus on in subsequent trips (funded by NSF), and future areas of interest and research.

Research and Damage from Previous WUI Fire Hazards

Tunnel Fire

There have been many wildfires in the WUI in the western United States. The Oakland firestorm in 1991, officially known as the Tunnel Fire, caused widespread structural damage and life loss. Firefighters responded quickly to the Tunnel Fire. First responders believed to have controlled the fire, however, pine needles continued to smolder on the ground. Strong winds the next morning reignited the flames and produced a firestorm of embers that lit objects ahead of the fire’s path. The fire destroyed over 3,000 structures and took 25 lives (Routley, 19917). The Oakland hills had been impacted by wildfires previously in 1923, 1970, and 1980, but residents continued to rebuild in the same location. Although the threat for fire in the area was known, no mitigation was previously implemented. The extensive damage demonstrated the potential destruction WUI fires could cause, and motivated a new perspective of the risk of WUI communities to fire hazards.

California took a long time to implement change with regards to fire risk and mitigation. The damages to residences in the Oakland hills were mainly due to the wooden exteriors of homes and the close proximity between homes. After the Tunnel Fire, homeowners replaced wooden shingles and siding with fire-resistant stucco or treated wood. However, codes regarding wildfire hazards were not implemented until later. In 2005, California state law required 100 feet of clearance surrounding structures, which could be enforced by local fire departments and Cal Fire (Cal Fire, 20128). Now Oakland also requires fire code inspection for homes and commercial structures and landscape inspections annually to ensure compliance (City of Oakland, 20199).

Humboldt Fire

In 2008 the Humboldt fire burned close to the town of Paradise, CA, destroying only six homes within the town limits and destroying approximately 80 others in a large, unincorporated area south of Paradise narrowly avoiding burning the Butte College. This fire was also unpredictable, reversing and changing direction as it progressed due to changing wind speeds and directions (Silva, 201810). Parts of Paradise were evacuated due to the threat of the fire. The process in which evacuations were called revealed limitations to the town’s evacuation plans. Two escape routes were closed due to the fire, leaving only one route accessible (Kuruvila, 200811). The Humboldt Fire motivated revisions to the evacuation plans for the town of Paradise.

Tubbs Fire

Before the Camp Fire, the Tubbs Fire was the most destructive wildfire in California history. It started in October 2017 and burned parts of Napa and Sonoma counties. The city of Santa Rosa was affected the most. The Tubbs Fire traveled approximately 12 miles in just over three hours (Griggs et al., 201712) and destroyed 5,636 structures (Cal Fire Incident Information, 201813). The fire impacted many schools in Santa Rosa, completely destroying Hidden Valley Satellite and Redwood Adventist Academy, damaging Roseland Collegiate Prep, and destroying roughly 50% of Cardinal Newman High School, including the library, main office, and portable buildings (Hassan, 201714; Benefield, 201715).

Following the fire, the school district saw a large decrease in student attendance. After one year, the school district had not yet recovered from low attendance and was in danger of losing funding (Leavenworth, 201816). In February 2018, Assembly Bill No. 2228 (201817) was passed ensuring continued funding for the impacted schools of the 2017 fires for a period of three years until attendance rates could be restored. In addition to impacting schools, the fire amplified an already existing housing crisis in Santa Rosa. From 2011 to 2015, vacancy rates decreased from 2.2% to 1.2% for homeowner inventory, and from 2012 to 2015, rental market vacancies decreased from 5% to 3.2% (Santa Rosa City Profile Report, 201718). The damage from the fire additionally reduced the available housing by 5%.

Since the Tubbs fire, the city requires all new construction within the WUI fire area to conform to Chapter 7A of the California Building Code to reduce wildfire damage probability to homes. In addition, the city adopted Chapter 20-16: Resilient City Development Measures into their Zoning Code (201819) to allow for reduced review authority for residential, lodging, and childcare facilities to speed up the recovery process and create housing for their struggling population.

During the fire, patients from the Kaiser Permanente Santa Rosa Medical Center and Sutter Health’s medical center were evacuated. The Sutter Health’s medical center was inaccessible immediately following the fire due to road closures, but both facilities were left undamaged (Kohli, 201720). However, The Santa Rosa Community Health’s Vista campus was destroyed by the Tubbs Fire. The facility was affected by fire, smoke, heat, and water damages totaling up to $16 million. The facility served approximately 24,000 patients a year, which had to be absorbed by other Community Health clinics in the area (North Bay Business Journal, 201721). The Community Health clinics are vital for the community as they offer healthcare services to residents regardless of their ability to pay by offering a sliding fee payment scale (Santa Rosa Community Health, 201922). Although original estimations stated the center would reopen after a year, their service closure was extended, and the health center now plans to reopen nearly two years after the fire in August 2019.

Reconnaissance Field Study: Observed Damage Post-Fire

The team performed the reconnaissance in two stages: the first stage was a scoping mission to observe the overall damage to the school district in the towns of Paradise and Magalia. This trip was performed by Dr. Fischer and Stefanie Schulze of Oregon State University. The second trip consisted of detailed data collection at the schools and hospital facility that consisted of lidar, drone, street map data, visual observations, and interviews.

The first reconnaissance trip occurred on January 31, 2019 and consisted of only visual assessment of damage incurred by schools due to the Camp Fire. The purpose of the evaluations was to document major damage to school buildings and to understand what mitigation efforts before the fire were successful in minimizing damage to buildings. The second reconnaissance trip occurred end of March into early April the same year. The team collected detailed data of the damage to schools, the Adventist Health Feather River Hospital, and a few commercial buildings. lidar technology and drone imaging was used to collect imaging data and measurements on building damage. This information will be used later to create digital models of the buildings for analysis. General observations were also made about the residential areas of the town. Additionally, interviews were held with schools and hospital administrators to gain insight into the impact the fire has had on their facilities, operations, and clients. From April through October 2019, we conducted 33 interviews in Paradise with representatives of 18 Butte County organizations. The visually observed damage will be summarized in this section.

School Buildings

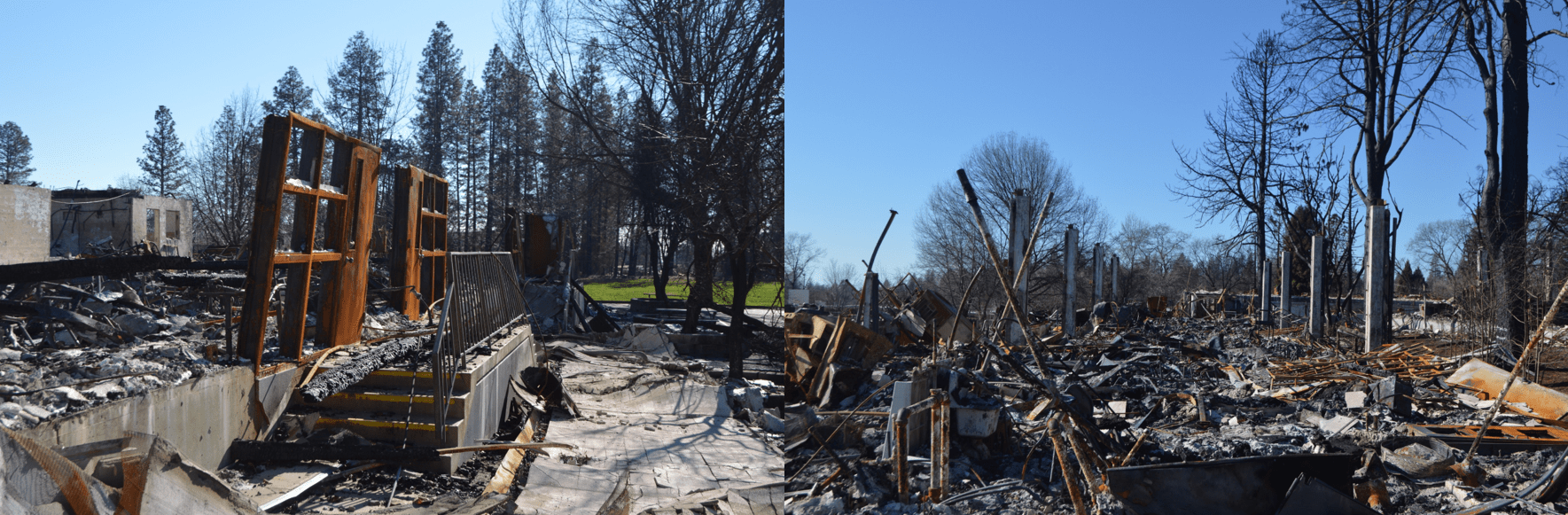

A few school buildings in Paradise completely collapsed due to the fire, including Paradise Elementary School and Ridgeview High School (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Paradise Elementary School Collapse

All of the schools had some level of damage. Common damages observed across all school campuses were due to the vulnerability of portable school buildings (Figures 2-4). These modular structures were easily ignitable during the Camp Fire and acted as fuel for igniting adjacent structures. Some schools survived the fire either due to luck of how the fire progressed through the city or through successful mitigation projects implemented before the fire. Observed isolated damages to schools and successful mitigation strategies are discussed in this section.

Figure 2. Portable Building Damage at Paradise Intermediate School

Figure 3. Portable Building Damage at Ponderosa Elementary School

Figure 4. Portable Building Damage at Children's Community School

Isolated Damage

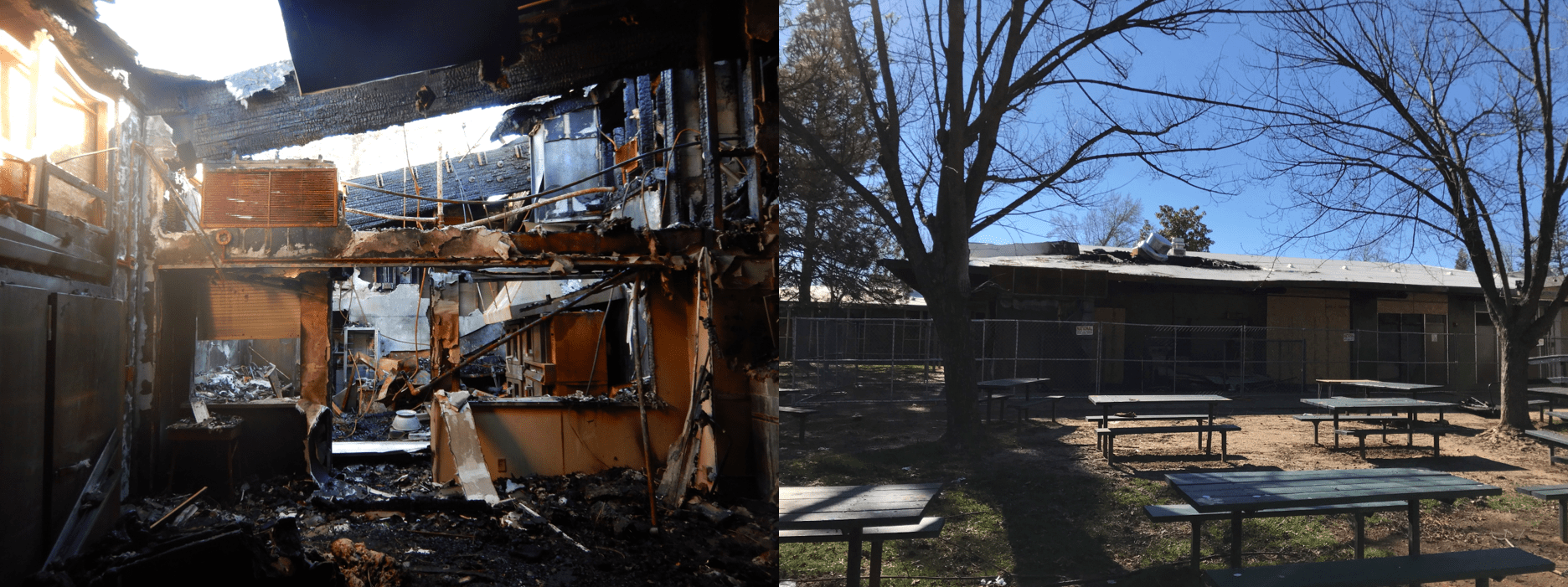

Ponderosa Elementary School had smoke damage inside the buildings, a damaged portable structure (Figure 3), and isolated damage to the common area (cafeteria and kitchen) building. The fire caused significant damage inside of the common area. The non-structural finishes of the space were damaged due to the heat of the fire. The paint on the walls bubbled, and the ceiling tiles fell. The fire caused a partial roof collapse where there was a large vent in the kitchen area, as shown in Figure 5. The glulam beams that supported the roof were charred. The fire affected a localized area of the roof support system before it was controlled and extinguished. The glulam beams did not collapse, and the remainder of the structural system supporting the roof was not damaged.

Figure 5. Ponderosa Elementary School Kitchen Damage (Left) and Roof Collapse (Right)

Achieve Charter High School is a steel frame metal building. This building did not collapse, however, there was evidence that the fire burned inside of the building. The fire was able to enter the structure through a hole in the roof, resulting in complete destruction of the non-structural components on the interior of the building. Figures 6 and 7 show the distortion of the steel members locally due to the fire. On the west side of the building, the concrete slab on grade was severely damaged indicating a higher fuel load on that portion of the building.

Figure 6. East Interior Wall of Achieve Charter High School Showing Steel Framing

Figure 7. Local Buckling of Members Due to the Fire at Acheive Charter High

Successful Mitigation

There were two cases observed where fire was prevented from damaging school buildings. The first was accidental, but effective. Ponderosa Elementary School is located adjacent to a lumber yard, which provided significant fuel for the Camp Fire. A metal shipping container between the lumber yard and a school building acted as a heat barrier and prevented the ignition of the structure. Where the metal container did not block heat, discoloration and bubbling of the exterior paint on the structure was observed.

Another success story of Paradise was the mitigation implemented at Pine Ridge Elementary School. In the summer of 2018, the Butte County Fire Safe Council performed fire mitigation on the south side of the school grounds through grants funded by the Sierra Nevada Conservancy and Cal Fire. Pine Ridge Elementary School is built on land granted to the school district by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and is completely surrounded by forested land. Within the school limits, the school buildings are bordered on most sides by sports fields, asphalt play areas, and asphalt parking and driveways. In addition to typical use for school activities, the school is used as an assembly site during fire evacuation for a section of the upper ridge residences, north of Paradise (Butte Fire Safe Council, 201723).

The mitigation performed at Pine Ridge included all invasive species and underbrush eliminated from the area using mastication techniques, clearing approximately 11 acres of land (Butte Fire Safe Council, 2017). Mastication involves reducing vegetation into small chunks by grinding or chipping trees and brush. An example of a masticated forest area following the fire is shown in Figure 8. From observing the surrounding burnt trees, it was apparent that the fire burned up to the school fences and then burned out due to lack of fuel. None of the other Pine Ridge Elementary School buildings were touched by the fire or damaged. The school was reopened on January 8, 2019 after minor repairs were completed.

Figure 8. Successful Mitigation of the Area Surrounding Pine Ridge Elementary School

The only damage observed at Pine Ridge Elementary School was to two of the portable school buildings on the northeast side of the school grounds. These portable classrooms were separate from the other main school buildings. No previous fire mitigation was performed in this location of the school grounds. Smaller buildings adjacent to the site of the damaged portables had only minor damage to the exterior of the buildings and were able to be repaired quickly within a few weeks after the fire.

Adventist Health Medical Care

The Adventist Health has two primary locations in Paradise. The Feather River Hospital is a large campus consisting of standalone buildings. The campus is located directly along the ridgeline above the Feather River Canyon and was one of the first areas in Paradise to be affected by the fire. Adventist Health also had a clinic in the southwest of town on Skyway Road, one of the main roads. The clinic suffered from smoke damages causing it to close briefly after the fire, but was reopened December 20, 2018 and currently operates with a limited scope of care services.

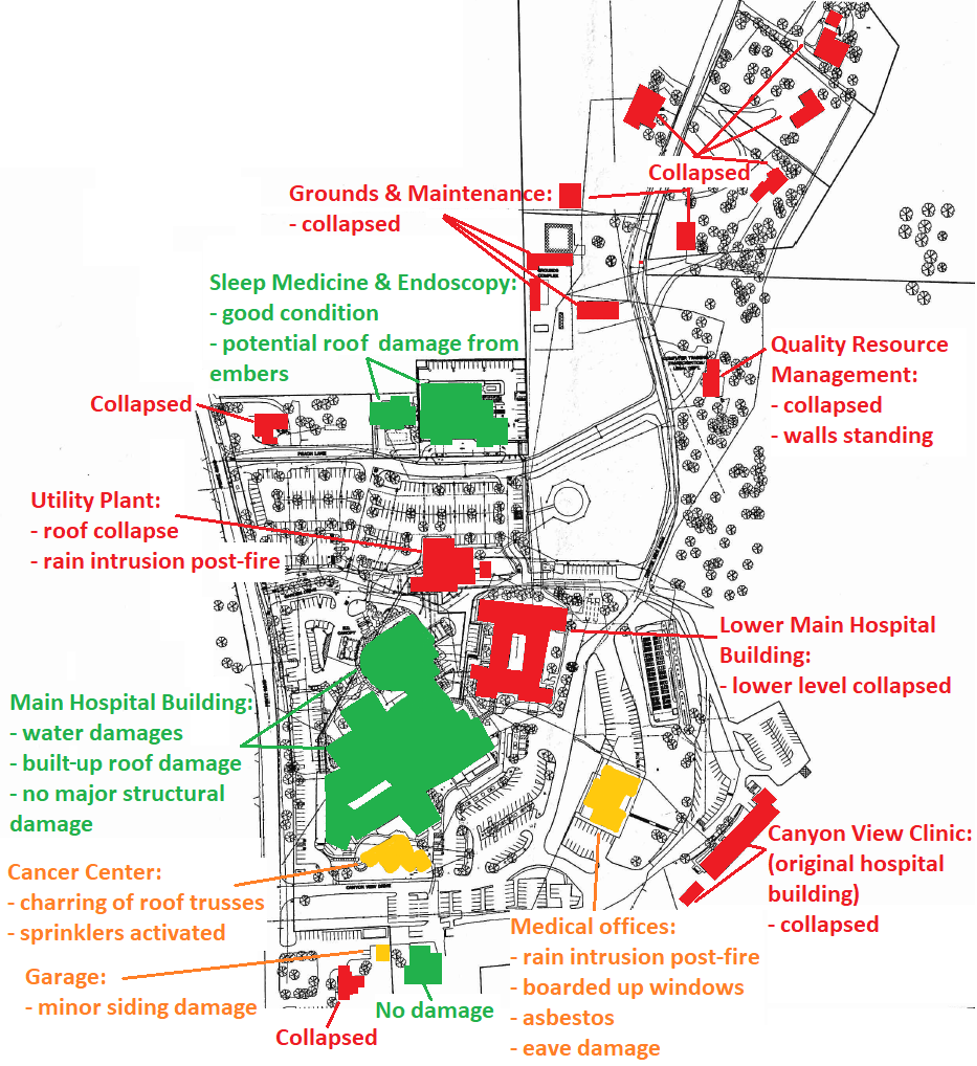

The Feather River Hospital suffered more severe damages and closed following the fire. A summary of the damage to the buildings is shown in Figure 9. Green indicates that there was no damage to the facility, or that it was repaired at the time that the team visited. Red indicates complete damage to the facility, or unsafe to enter, and orange indicates partial damage.

Figure 9. Adventist Health Feather River Hospital Map Outlining Building Damages

A portion of the emergency room facility collapsed, as shown in Figure 10. Roof damage of many buildings has led to serious water damage following the fire, in most cases due to water infiltrating the buildings. The water infiltration caused leaks, or in some cases, mold infestation. The hospital’s utility building was severely damaged due to the roof collapse. This damage significantly affected the operability of the campus. The roof collapse damaged much of the utility equipment inside the building required to operate the hospital, including the HVAC system, generators, and heating and cooling equipment, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 10. Partial Collapse of Feather River Hospital Emergency Room

Figure 11. Damage to the Feather River Hospital Utilities

Single Family Homes and Commercial Buildings

The pattern of destruction from the fire appeared to be random at times. The majority of single-family homes and other buildings in Paradise were destroyed in the fire, however there were a few areas of Paradise where homes were not damaged. More vulnerable construction, such as mobile homes, were destroyed by the fire. Similar to single family homes, commercial buildings were affected in clusters along the main commercial road through Paradise. Most commercial buildings in this area were constructed out of concrete masonry unit (CMU) walls with either timber or steel joist framing that supported the roof. The storefront openings are typically framed with steel columns and glulam beams. Typical damage observed to these buildings was roof collapse due to the fire, as shown in Figure 12. The charred glulam beams at the storefront collapsed, leaving the steel columns.

Figure 12. Interior and Roof Collapse of a Commercial Building

Oftentimes commercial and residential roofs were affected by the fire. This was observed as charring, discoloration, and fire damage under eaves and near gutters, as seen in Figure 13. Sometimes signs of firebrand spotting on the roofs were observed and, in some cases, collapse of all or portions of the roof. Damages to the roof additionally led to water damage within these structures from rain following the fire. Correlation between adjacency to trees and vegetation and the severity of damage was also observed. This was distinguished only when buildings saw exterior damage but did not completely collapse. In areas where homes and commercial structures were completely destroyed, the vegetation was also mostly gone.

Figure 13. Fire Damage Along a Roof Eave

Qualitative Study of Impacts on Schools and Healthcare Facilities

Previous studies and anecdotal evidence have shown that the recovery of schools and hospitals is essential to population recovery and have ripple effects on other aspects of a community recovery. We conducted a qualitative case study on schools and healthcare facilities in Paradise to examine these effects. Paradise Camp Fire recovery presents an opportunity to elucidate the complexity and unique challenges inherent to school and healthcare recovery in relation to overall community recovery. This study set out to answer two questions: (1) what are the impacts of the Camp Fire damages on operations of healthcare and educational service and subsequently on population return?, and (2) what are the effects of the service shortages on facilities in the surrounding regions?

This research utilizes two data collection techniques: in-depth interviews and archival research. We conducted 13 interviews with local hospitals and schools’ staff to understand their experiences, challenges, and perspectives about this fire disaster and learn about their assessment of the fire impacts, recovery, and mitigation in Paradise. The interviewees included superintendents or staff from affected schools in Paradise and Magalia, healthcare facilities, a local nonprofit agency, and Chico State University. The interviews were semi-structured to gather similar information from each respondent while allowing new topics to develop. Interviews were designed to take between 45 and 60 minutes each and were conducted at the place of the interviewees’ choosing, all in Paradise or Chico. Interviews, all audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, along with detailed field notes by investigators were transcribed for future quantitative analysis.

We collected and reviewed documents, reports, and media content about the Camp Fire impacts and recovery, including the Paradise long-term community recovery plan, North Valley Community Foundation 6-month report, City of Paradise and other local and state organizations press releases, newspapers, and other forms of media reporting looking for information on schools and healthcare facilities. We have uploaded these documents and recordings to the Atlas.ti software for qualitative analysis. We are in the process of applying coding techniques to the interview and archival data in three stages (Saldaña, 200924). First, open coding of basic themes only; second, examining relationships between basic themes through axial coding to connect similar themes under larger concepts; third, selective recoding of the data in relationship to these larger ideas. Preliminary findings in the form of large concepts identified so far in the analysis process are discussed in this section with respect to the impacts of the Camp Fire on schools and healthcare services, recovery progress, and interdependencies between these essential services and community recovery.

Impacts of the Camp Fire on Schools

All of the school interviewees emphasized, sometimes with great emotion, the overwhelming and successful evacuation of all children out of Paradise in the morning of the Camp Fire. This recurring emphasis indicates the extraordinarily strong ties between the schools as institutions and the community that go beyond providing educational services. After the disaster all of the schools were closed for three weeks because of the air quality and difficulty of access. Given the complete collapse and partial damages to three schools in Paradise, many students were left without a school, and Paradise Unified School District had to figure out where to educate its students in a short window of time and under high pressure of real estate competition in surrounding towns given all of the damaged businesses that were also looking for a new location.

While damage and closure of schools has caused interruption in education and lowering the schools capacity in Paradise, the bigger impact, according to our interviews, is the double loss of home and school for the students who lost both in the Camp Fire and had to move to a new school for the rest of the school year. A dilemma was raised several times that students who lost both their school and home in Paradise had to deal with instability and adjustment both to a new living situation, often in a trailer or doubling up with extended family, and to a new school. On the other hand, several of our interviews raised concerns about the potential stress and sadness that some displaced students from undamaged schools have to face every day when they are bussed through Paradise by seeing the devastation left by the fire.

Schools in all surrounding areas like Chico and Durham have tried to make room for the Paradise students by finding classrooms and transportation and especially counseling services that were needed more than ever before (North Valley Community Foundation, 201925). It is important to note that the impacts of the Camp Fire on students can be exacerbated by the pre-disaster vulnerabilities related to trauma for a large group of these students. A 2013 survey of California adults found that three-quarters of Butte County residents reported having lived through a traumatic event as a child, the highest rate in the state of California (Balingit, 201926).

Impacts of the Camp Fire on Healthcare Facilities

Adventist Health Feather River clinic and Adventist Health Hospital in Paradise are vital for the Paradise community as faith-based care providers that offer healthcare services to residents regardless of their ability to pay. With the closing of the hospital and limited operations of the clinic in Paradise, our interviews raised concerns about the availability of affordable healthcare to their displaced patients in sorrowing areas. Feather River Hospital was previously a 101-bed, acute-care hospital and the leading employer in Paradise (George, 201927).

Over 1,000 part-time and full-time employees will be laid off following the immediate closure, which has made it difficult to make decisions about returning to Paradise as their home. Many of the previous patients of the hospital also have expressed the dependency of their return upon the fate of this healthcare provider. This dependency is significant given the older profile of the population that had chosen Paradise as home especially for retirement based on the availability of healthcare facilities.

Recovery Efforts and Progress

School recovery

Funds provided through the Butte Strong Fund that collected donations after the Camp Fire have made significant contributions to the operation of schools remaining in Paradise and the schools that received the displaced students. In the six months after the fire, the Fund has awarded $2 million for schools and public safety through donor-advised donations. A few examples of the initiatives funded through this local organization for schools are providing free passes for students who need to ride B-Line buses to get to and from schools and gas cards to assist Paradise Elementary School staff teaching in Durham because of the Camp Fire, providing Chromebooks and counseling services to displaced students in Chico Country Day School and Palermo Union School District, and purchasing data for internet use at Paradise Intermediate School, currently located in an old hardware store building, which lacks the infrastructure to provide internet at the level that a school needs (North Valley Community Foundation, 2019).

Healthcare facility recovery

The medical clinic, located on Skyway in Paradise, reopened in December and is still available to patients. Adventist Health clinics in two close by towns are also open. But the Paradise hospital is to remain closed until further notice. According to the hospital press release it will be at least until 2020 before services could be reopened on their Pentz Road campus, “Even then, the type of services required for the community that ultimately redevelops in this geography are likely to be different from what we have historically provided,” (Adventist Health, 201928).

Several residents have expressed concerns about the hospital closing, as shown by the comments below:

“We live about 2 miles down on Pentz and purchased our home here due to the security of knowing this fine hospital was close by. The Cancer Center was the best.”

“I believed Feather River’s earlier comment ‘…will reopen,’ and we decided to rebuild on that belief. Our family is greatly disappointed.”

After the fire, employees were transferred to nearby clinics in Chico and Marysville, with some being offered full pay and benefits through February 5. The total of these stipends reaches about $30 million.

Summary and Future Work

In this study, two reconnaissance missions to Paradise, CA were conducted to collect data through various techniques, including visual observations, lidar, drones, street map data, and interviews. The overarching goals were to document and measure damage to critical facilities, assess the success of mitigation strategies implemented to protect critical infrastructure before the fire, document strategies being planned or already implemented after the fire for safeguarding against future events, and quantify the impact of damage to essential facilities in Paradise on the surrounding regions. The main findings can be summarized as follows:

- Wildland fires behave in an erratic way affecting infrastructure seemingly randomly

- Modular and temporary structures such as portable school buildings and mobile homes are vulnerable to complete loss in wildland fires

- Functionality loss of structures due to water infiltration, fire destruction of interiors of structures, etc. following a wildfire is as impactful to community operation as structural damage

- When maintained, mitigation strategies to create defensible space surrounding structures can save a structure from experiencing severe wildfire damages

- The speed in which a town recovers following wildland fire hazards depends on the return of community facilities such as schools and healthcare opportunities

The post-wildfire reconnaissance in Paradise brought many research gaps to the team’s attention. The information gathered will be helpful in guiding us to answers for how to assess the vulnerability of structures in wildfire, how to implement successful mitigation strategies, and how to design engineered structures to be resilient to wildfires. One area to expand is creating damage assessment forms for wildfire damage and distinguishing between structural damage and reduction in functionality. Consistent assessment of damage and vulnerabilities of structures in wildfire is needed to improve the resiliency and safety of communities. In the future, considerations for multiple hazards shall also be assessed. How to approach defining a structure as safe when there is a risk of an additional hazard can be challenging. Codes should then reflect these discussions so that multiple hazards are considered in all stages of a structure, from design to retrofit and repair.

Some other topics for future work include defining processes for risk assessment of WUI communities, modeling wildfire propagation through WUI communities, and risk assessment of water distribution system damage and contamination. These future investigations are vital for making WUI communities more resilient to wildfire. Communities are increasingly impacted by wildfire disasters in the western United States. As populations continue to move towards WUI areas and the climate warms, the risk of wildfires grows, as does the importance of wildfire resilient communities.

The importance of critical facilities for the livelihood of communities cannot be overlooked. Schools and hospitals, in particular, are vital for the social stability of communities. As such, developing appropriate damage prediction models for schools and hospitals in WUI areas is a logical step forward. These damage models will serve as the foundation on which functionality assessment frameworks can be devised. In cases in which only one hospital exists in the community, such as Paradise, the effect of the loss in functionality of the hospital on the community’s infrastructure, social, and economic sectors becomes critical to evaluate. Similarly, the effect of the community as a whole on regaining functionality of the hospital is also important. Therefore, modeling recovery of the relevant sectors while properly accounting for interdependencies among the sectors is needed.

References

-

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire). (2018). Camp Fire Progression Map. ↩

-

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire). (2019). Incident Information. Camp Fire Incident Information. Retrieved from https://fire.ca.gov/incident/?incident=75dafe80-f18a-4a4a-9a37-4b564c5f6014 ↩

-

Radeloff, V. C., Helmers, D. P., Kramer, H.A., Mockrin, M. H., Alexandre, P.M., Bar-Massada, A., … Stewart, S.I. (2018). Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. PNAS, 115(13), 3314-3319. ↩

-

Gafni, M. (2018, December 2). Rebuild Paradise? Since 1999, 13 large wildfires burned in the footprint of the Camp Fire. The Mercury News. Retrieved from https://www.mercurynews.com/2018/12/02/rebuild-paradise-since-1999-13-large-wildfires-burned-in-the-footprint-of-the-camp-fire/ ↩

-

Schoennagel, T., Balch, J. K., Brenkert-Smith, H., Dennison, P. E., Harvey, B. J., Krawchuck, M. A., … Whitlock, C. (2017). Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. PNAS, 114(18), 4582-4590. ↩

-

Gibbs, L., Block, K., Harms, L., MacDougall, C., Baker, E., Ireton, G., … Waters, E. (2015). Children and young people’s wellbeing post-disaster: Safety and stability are critical. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 13, 195-201. ↩

-

Routley, G. (1991). The East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California. USFA-TR-060. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). ↩

-

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire). (2012). 100 Feet of Defensible Space is the Law. Retrieved from https://calfire.ca.gov/communications/communications_firesafety_100feet ↩

-

City of Oakland. (2019). Fire Safety Inspections. Retrieved from https://www.oaklandca.gov/services/wildfire-district-inspections ↩

-

Silva, R. (2018, June 15). The Humboldt Fire, 10 years later. Paradise Post. Retrieved from https://www.chicoer.com/2018/06/15/humboldt-fire-10-years-later/ ↩

-

Kuruvila, M. (2008, June 15). 74 Paradise homes destroyed by Humboldt Fire. SFGate. Retrieved from https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/74-Paradise-homes-destroyed-by-Humboldt-Fire-3209635.php#photo-2064937 ↩

-

Griggs, T., Lai, K.K.R., Park, H., Patel, J.K., White, J. (2017). Minutes to Escape: How One California Wildfire Damaged So Much So Quickly. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/12/us/california-wildfire-conditions-speed.html ↩

-

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire). (2018). Incident Information. Tubbs Fire (Central LNU Complex) Incident Information. Retrieved from https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2017/10/8/tubbs-fire-central-lnu-complex/ ↩

-

Hassan, A. (2017, October 10). Cardinal Newman High School Sustains Significant Damage in Santa Rosa Fire. NBC Bay Area. Retrieved from https://www.nbcbayarea.com/news/local/Fire-Guts-More-Than-50-Percent-of-Cardinal-Newman-High-School-Campus-in-Santa-Rosa-450208613.html ↩

-

Benefield, K. (2017, October 9). Fire damages Cardinal Newman High School, destroys Hidden Valley Satellite. The Press Democrat. Retrieved from https://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/7507311-181/sonoma-county-school-closures?sba=AAS ↩

-

Leavenworth, S. (2018, April 2). A ‘very difficult year’ – Sonoma schools still recovering from devastating fire. The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved from https://www.sacbee.com/news/local/article207688414.html ↩

-

Assembly Bill No. 2228. (2018). AB-2228 Education finance: school apportionments: wildfire mitigation. ↩

-

Santa Rosa City Profile Report. (2017). Sonoma County Economic Development Board. ↩

-

Santa Rosa City Code. (2018). Title 20 Zoning, Chapter 20-16: Resilient City Development Measures. ↩

-

Kohli, S. (2017, October 9). Tubbs fire forces two hospitals to evacuate. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-northern-california-fires-live-tubbs-fire-forces-two-hospitals-to-1507579831-htmlstory.html ↩

-

North Bay Business Journal. (2017, November 10). Santa Rosa Community Health clinic destroyed by wildfire. North Bay Business Journal. Retrieved from https://www.northbaybusinessjournal.com/industrynews/healthcare/7622612-181/santa-rosa-vista-clinic-destroyed?artslide=0 ↩

-

Santa Rosa Community Health. (2019). Get Help with Costs. Santa Rosa Community Health. Retrieved from https://srhealth.org/costs-insurance/get-help-with-costs/ ↩

-

Butte Fire Safe Council. (2017) Upper Ridge Emergency Fire Zones and Public Assembly Points. Butte Fire Safe Council Flyer. ↩

-

Saldana, J. (2009). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, Sage Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA. ↩

-

North Valley Community Foundation. (2019). Rising from the Ashes: A six-month progress report on Camp Fire relief and recovery. ↩

-

Balingit, M. (2019, January 17). Out of the ashes, schools in fire-ravaged Paradise, Calif., struggle to rebuild. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/out-of-the-ashes-schools-in-fire-ravaged-paradise-calif-struggle-to-rebuild/2019/01/17/148771fc-03df-11e9-b6a9-0aa5c2fcc9e4_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.b77b4ca04975 ↩

-

George, K. (2019, February 14). Feather River hospital to close, over 1,200 employees to be laid off. The Orion. Retrieved from https://theorion.com/78106/news/feather-river-hospital-to-close-over-1200-employees-to-be-laid-off/ ↩

-

Adventist Health. (2019). Camp Fire Press Page. Adventist Health Feather River. Retrieved from https://www.adventisthealth.org/feather-river/camp-fire-press/ ↩

Fischer, E., Mahmoud, H., Hamideh, S. & Schulze, S. (2021). Post-Wildfire Damage: 2018 Paradise, California Camp Fire Reconnaissance Report (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 302). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/post-wildfire-damage