Relocation, Repopulation, and Rising Seas

Monroe County, Florida, Following Hurricane Irma

Publication Date: 2018

Abstract

To what extent do long-term risks associated with climate change, specifically sea level rise, contribute to repopulation or relocation decisions of people displaced by disasters in coastal communities? This research focuses on this question, which has received little attention in disaster literature. It is based on a case study of Monroe County, Florida, in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma. Its data collection methods include interviews (n=24), participant observation, and review of secondary sources (e.g., local plans, newspaper articles). The study suggests that, as displaced populations get back to their “new normal” in the aftermath of the hurricane, their focus is on short-term, immediate needs: pre-disaster challenges that were exacerbated after the hurricane—specifically a lack of affordable housing and low paying jobs—and the risks associated with potential storms. Long-term environmental risks associated with sea level rise have little to no direct influence on their relocation or repopulation decisions. The study suggests that policymakers need to find the optimum period to act on sea level rise adaptation and mitigation in the aftermath of a disaster, after affected populations’ immediate needs are addressed and before the populations’ collective memory of the disaster is forgotten.

Introduction

Climate change has a range of impacts on the natural and built environment in and around communities across the globe (IPCC 2007)1. One such impact is sea level rise, which poses significant risks not only to coastal communities, but also to inland communities, which are likely to be the destination of environmental immigrants, those who would migrate away from coastal communities (IPCC 20142, Tacoli 20093; Myers 20024). Although there is no consensus on how to define environmental migrants, the International Organization for Migration (IOM 20115) characterizes them as “persons or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment that adversely affects their lives or living conditions, are obliged to leave their habitual homes, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move either within their country or abroad” (as cited in Environmental Migration Portal, 20186). Migration due to changes in environmental conditions is nothing new. Studies estimate that the number of environmental migrants has been increasing and will rise to approximately 200 million by 2050 (IOM 20087, Warner et al. 20108). The reasons behind environmental migration are complex, encompassing environmental drivers such as climate change and its associated impacts such as sea level rise, intertwined with economic, political, social, and demographic drivers (Black et al. 20119).

Migration also takes place due to extreme events. In recent years, the impacts of extreme weather events have been devastating for settlements throughout the United States (e.g., New Orleans, Puerto Rico), causing mass migration from these areas. In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina, for example, caused substantial flooding in over 80 percent of the city of New Orleans and displaced more than a million Gulf Coast residents (Gotham 201710). Those who decided to stay in the area after this catastrophic disaster have been struggling with a variety of problems (e.g., economic challenges, post-traumatic stress and depression symptoms, and other health problems) (Fothergill & Peek 200411, Fothergill & Peek 201512, Fussell et al. 201013, Gotham 2017, Mazzei & Robles 201714). The residents of Puerto Rico, who were hit by another catastrophic storm, Hurricane Maria, in September 2017, have been struggling with several challenges since then. They had to endure living without electricity for approximately three months, were without water for more than two months, and were without cellular service for more than one month (Kishore et al. 201815). Many had already been migrating from the island (Matthews 201716). They continued to leave the island at a faster pace to escape from these harsh conditions and have been living on the U.S. mainland.

It is possible to see a similar situation in Monroe County, which is the southernmost part of the state of Florida and the United States. The vast majority of the population in the county, 77,000 people (American Fact Finder 201717), lives on a chain of islands, the Florida Keys, which is highly vulnerable to tropical weather events. The Florida Keys were hit by Category 4 storm, Hurricane Irma, on September 10, 2017, and have been dealing with the disaster recovery process for more than a year. Faced with a variety of challenges (e.g., lack of affordable housing, low-wage job industries, logistical challenges), many residents, 3,000 people, have already left the Keys in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma (O'Hara 201818).

Focusing on the case of Monroe County, this study aims to examine the extent to which the long-term risks associated with climate change, specifically sea level rise, contribute to repopulation or relocation decisions of people displaced by disasters in coastal communities. This topic has received little attention in disaster literature. The significance of the study is twofold. First, it enables us to understand coastal communities’ current and future vulnerabilities to natural hazards (e.g., hurricanes and floods) and to long-term environmental risks (e.g., sea level rise). Both coastal communities and inland areas are likely to be impacted by the adverse impacts of climate change (e.g., disaster-induced relocations). Hence, it is important to identify the vulnerabilities emerging from these slow-onset and immediate hazards. Second, the study uncovers the relocation and rebuilding processes in the aftermath of disasters, which present communities with opportunities to be more adaptive and resilient (Berke et al. 199319, Ganapati & Ganapati 200920, Guarnacci 201221, Vale & Campanella 200522).

The study’s data collection methods include semi-structured interviews (with nested quantitative survey questions) (n=24), participant observation, and review of secondary sources (local plans, newspaper articles). This study uncovers whether the residents consider long-term environmental risks associated with sea level rise in their relocation and/or repopulation decisions. It also investigates whether this consideration varies among different population groups (e.g., younger populations, residents with high education levels, homeowners). In doing so, the author aims to provide guidance for policymakers to better link disaster recovery with adaptation to and mitigation of long-term environmental risks associated with sea level rise.

Background: Gaps in the Literature

Scientists show that climate change has a variety of impacts on the natural and built environment and communities across the world (IPCC 2007). Hence, interest in environmental policy development, which emerged from disaster-prone countries, such as Australia, the Netherlands, and the United States, has increased across the world (Titus 198923). Sea level rise due to climate change is a significant long-term global risk, the progression and effects of which have been studied by many scholars (Bray et al. 199724, Dasgupta 200725, Houghton et al 199226, Karim & Mimura 200827, Mimura 199928, Nicholls & Cazenave 201029, Tol & Nicholls 200830, Warrick 199331, Wu & Fisher 200232). It is reported by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) that worldwide approximately 265.3 million people were internally displaced as a response to disasters, over the period between 2008 and 2018. Although the number is not available for populations who have been migrating due to slow-onset hazards (e.g. droughts or sea level rise) it is evident that these hazards are also impactful on displacements (Migration Data Portal, 201833). There are a variety of factors that motivate migration. Black et al. (2011) list five drivers of migration: economic, political, social, demographic, and environmental. They state that global environmental change has both direct and indirect influences on migration (Black et al. 2011).

Similarly, a variety of motivations that drive relocation in post-disaster periods, as well as the ones that drive return decisions, have been studied by scholars (Burton et al. 199334, Clark et al. 199835, Fussel et al. 2010, Landry et al. 200736, Morrice 201337, Myers et al. 200838). However, the post-disaster recovery literature lacks a focus on long-term environmental risks, such as sea level rise. Although the potential risks associated with climate change, especially sea level rise, are likely to exacerbate the impacts of natural disasters, the link between these two remains understudied. This research contributes to the existing disaster literature by analyzing the motivations behind relocations and repopulations in a post-disaster recovery context, with a particular focus on risk perception caused by global environmental changes. Furthermore, it enables an understanding of whether the level of this perception varies by emotional, socioeconomic, and demographic factors that are mentioned in other studies (Fussel et al. 2010; Landry et al. 2007; Morrice, 2013).

There is growing literature both on the progression and impacts of sea level rise, especially as they relate to coastal communities (Bray et al. 1997, Dasgupta 2007, Houghton et al, 1992; Karim and Mimura 2008, Mimura 1999, Nicholls and Cazenave 2010, Tol and Nicholls 2008, Warrick 1993; Wu and Fisher 2002), the most densely populated counties in the United States (FitzGerald et al. 200839). Similarly, the literature on disaster recovery is on the rise, even though recovery has often been articulated as the least studied phase of disasters (Berke et al.1993, Esnard & Sapat 201440; Ganapati and Ganapati 2009). One of the themes in recovery literature deals specifically with people’s motivations to relocate away from or return to their communities. As Morrice (2013) underscores, decisions about whether to return or relocate are “complex, multidimensional, and individually unique” (Morrice, 2013 p. 33). Such decisions include demographic (e.g., age, ethnicity, race, marital status), socioeconomic (e.g., social networks, income level, employment, homeownership), and emotional factors (e.g., attachment to place), as well as the damage level (e.g., housing damage) (Burton et al. 1993, Clark et al. 1998, Fussel et al., 2010; Landry et al. 2007, Morrice 2013; Myers et al. 2008). Yet, the role of environmental risks associated with sea level rise on relocation or repopulation decisions in the aftermath of a disaster remain understudied.

To examine public opinion in terms of relocation and repopulation decisions, the author analyzes the post-disaster period, during which the sensitivity of the population to probabilities of occurrence of natural hazards peaks (Esnard et al. 201141, Levine et al. 200742), and asks three inter-related research questions:

To what extent do long-term risks associated with sea level rise contribute to relocation or repopulation decisions of people affected by disasters?

Which population groups, if any, do take long-term risks associated with sea level rise into consideration in their relocation or repopulation decisions?

What can policymakers do to better link disaster recovery with adaptation to and mitigation of long-term environmental risks associated with sea level rise?

Research Context and Methods

The research is based on a case study of Monroe County, Florida, which includes the Florida Keys. It was conducted between July 24 and August 12, 2018. Monroe County was an ideal case study site because it is highly vulnerable to flooding due to tropical storms and to long-term environmental risks associated with sea level rise (Wadlow 201743, Zhang et al. 201144). It is the southernmost part of the continental United States and has a very low average elevation—less than 1.5 m above sea level. The region is highly vulnerable to long-term environmental changes due to its erosion-prone limestone geology, the isolated location from the mainland, and damage from frequent tropical weather events (Flugman et al. 201245, Ross et al. 200946, Zhang et al. 2011). Hurricane Irma was the most recent of these catastrophic cyclones and destroyed 25 percent of the buildings in the Florida Keys and left 65 percent with major damage (Baumgard 201747, Mak 201748). Within Monroe county, Big Pine Key, Marathon, and Cudjoe Key were the most impacted areas (City of Marathon Damage Assessment Report 201749).

Primary data collection methods for the case study included interviews and participant observation, which were supported by a review of secondary sources. For the interviews, the author used a nested mixed methods design. The interview questionnaire primarily included open-ended questions, which provided qualitative data. It also had close-ended questions, which were nested into the open-ended questions, and provided quantitative data (see Appendix A). The main goal of the interviews was to understand whether the residents were aware of sea level rise as an environmental risk, and the extent to which this risk influenced their relocation and/or repopulation decisions.

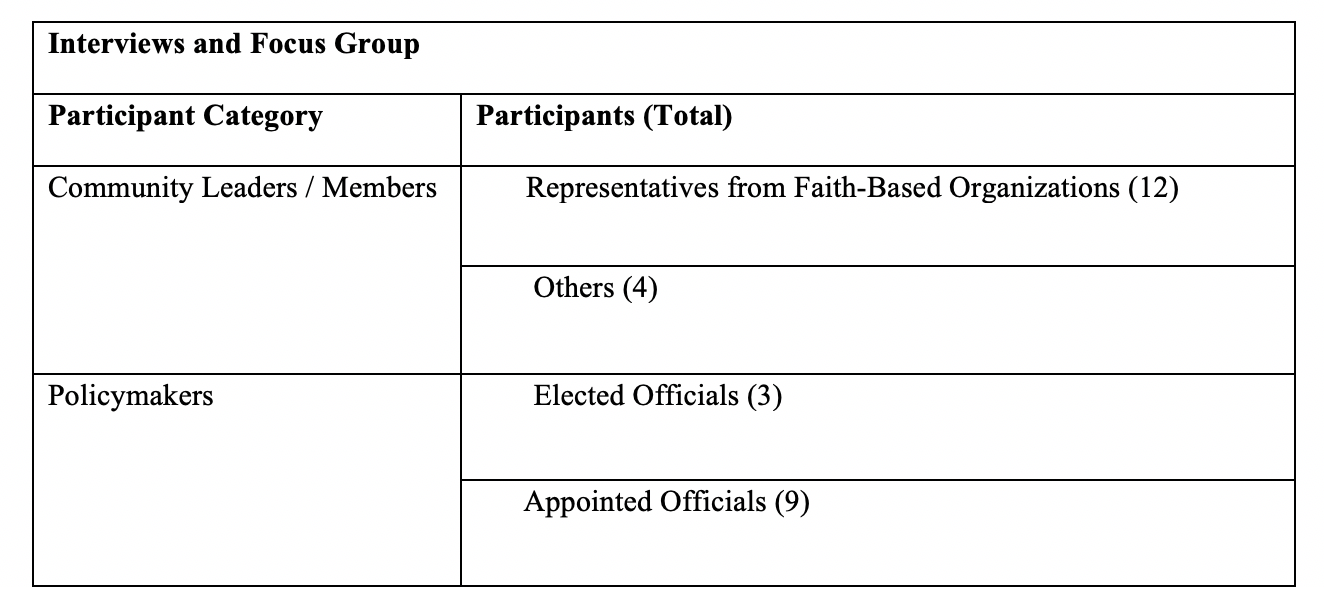

The study sample included two main groups: community leaders (e.g., heads of local nongovernmental organizations and church groups) and elected and appointed government officials (e.g., county commissioners and local government employees from emergency management, urban planning, and public works departments). The author identified the initial set of interviewees reviewing secondary sources (newspapers, government websites) and expanded this sample using snowball sampling. The author reached theoretical saturation with 23 individual interviews and one focus group (n=28) (see Table 1). The author conducted the interviews in person (n=13) or via telephone (n=11), depending on the preferences and availability of participants. The duration of interviews varied from 45 minutes to three and a half hours. The author recorded the interviews with the permission of the interviewees and transcribed them verbatim.

Table 1. Number of participants per group

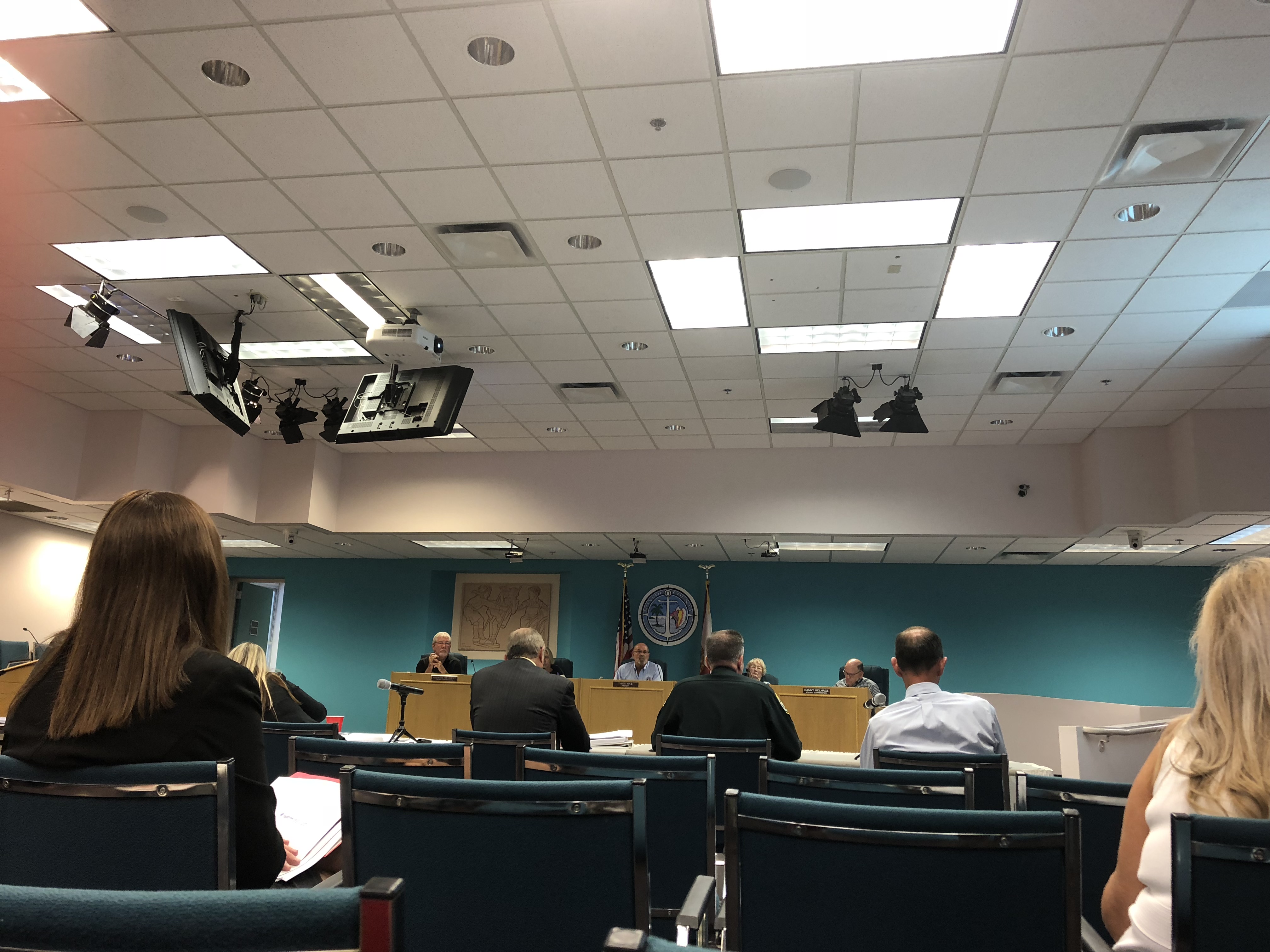

The author relied on participant observation to develop a more comprehensive and holistic understanding of the repopulation and relocation context in the area and to triangulate interview data. Assuming the role of observer as participant, the author conducted participant observation at public events, such as the Board of Monroe County Commissioners meeting on July 31, 2018, and the First Baptist Church of Islamorada weekly meeting on August 8, 2018. To understand the extent of hurricane damage, the author also visited the most impacted neighborhoods in the county, including Big Pine Key, No Name Key, and the city of Marathon (see Appendix B). The author took detailed field notes and photographs while conducting observations.

The author supplemented primary data collected through interviews and participant observation through a review of secondary sources. These sources included local-level plans (e.g., Monroe County Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan, Monroe County Recovery Plan), damage assessments, emergency management and planning laws and regulations, and news pieces from regional (Miami Herald) and local (Key West Citizen) newspapers. These sources were instrumental in identifying the initial set of interviewees as mentioned earlier and also in terms of triangulating data.

For data analysis, the author imported the transcriptions of interviews (open-ended questions) and observation field notes into NVivo 12, a qualitative data analysis software program, and coded them. The author derived the initial set of codes from the research questions and the interview guide provided in Appendix A and supplemented them with emergent sub-codes. The close-ended questions nested into the interview instrument were entered into Excel. The author analyzed responses to these questions mainly in relation to the second research question: Which population groups, if any, do take long-term risks associated with sea level rise into consideration in their relocation or repopulation decisions?

The study involved two key challenges. While the former was logistical and unique to the geography of the study location, the latter was related to studying sea level rise. Florida Keys is a 120-mile island chain, which is linked through a single road, the Overseas Highway. Hence, it was difficult to travel across the area to conduct multiple interviews during working hours in a given day. Depending on the traffic, it took two and a half to three hours to go from one end of the Florida Keys to the other (e.g., from Key Largo to Key West). To address this challenge, the author attempted to group interviews in certain areas and conducted some interviews via telephone rather than face-to-face. Another challenge had to do with keeping interviewees interested while asking questions related to sea level rise. In general, the participants were quite enthusiastic to talk about their Hurricane Irma experiences. When asked about their thoughts on sea level rise, however, they seemed a little disappointed. They seemed to prefer to talk about their recent hurricane experience, which left them with a number of immediate unmet needs, as opposed to their long-term needs with respect to sea level rise.

Preliminary Findings

The findings that emerged from the analysis of interview, observation, and secondary data are grouped under three themes: relocation, repopulation, and linking disaster recovery with SLR adaptation and mitigation.

Relocation

The decision to return or relocate in the aftermath of a disaster is “complex, multidimensional and individually unique” (Morrice 2013 p. 33). Residents’ decisions to move away from or return to their communities vary depending on demographic (e.g., age, ethnicity, race, marital status), socioeconomic (e.g., social networks, income level, employment, homeownership), and emotional factors (e.g., attachment to place), as well as the damage level (e.g., housing damage) (Burton et al. 1993, Clark et al. 1998, Fussel et al. 2010, Landry et al. 2007, Myers et al. 2008, Morrice 2013).

News outlets project that nearly 3,000 people moved out of the Florida Keys following Hurricane Irma (O'Hara 2018). This study revealed the importance of high living costs in relation to relocation decisions of Florida Keys residents. The area’s high cost of living was a challenge that existed prior to Hurricane Irma. It was, however, exacerbated following the hurricane. In the Florida Keys, the residents were not able to find an affordable place to live, work for a reasonable income, or fulfill their basic needs even before the hurricane. As noted in the Board of County Commissioners Special Budget Meeting (July 31, 2017), land shortages in the Keys kept the housing prices high. The housing stock was also limited. Most of it included secondary homes that remained unoccupied for several months of the year (American Fact Finder 201650) or were rented for a short term. Hence, a relatively small percentage of housing was available to meet the long-term housing demands of residents. Residents with limited income were forced to live in trailers or recreational vehicles (e.g., in Big Pine Key, which was hit hard by the storm) in flood zones, or on their boats. Some also shared single family houses. They were not registered as the residents of these homes, and hence, were ineligible for housing assistance. Along with a lack of affordable housing options, there were other factors that drove the cost of living in the Florida Keys, including high costs of home maintenance, flood insurance, and goods (e.g., groceries). One of the public officials who dealt with recovery needs of the community after the hurricane seemed overwhelmed with the stories about high living costs:

So there's limited housing stock…Housing stock which drives the price of housing very high which…and the wages do not keep up with that cost of living based on housing, so most people in the Keys are spending at least fifty percent of their income on housing and nationally we know that that's not a good percentage. It should be maybe thirty or less, and…and many, many folks are spending up to seventy percent of their wages on housing, so you know it so that's kind of a triple a fact of you know the housing market rental markets being extraordinarily high, and a lot of folks who have second homes here do either don't rent them or might rent and you know seasonally so annual rentals.

Incompatible with the high cost of living in the Keys, the economy is highly dependent on low-wage jobs, mainly in service-sector-driven industries (e.g., hotels, restaurants), construction, and fishing. The residents, who are the drivers of the economy and the permanent occupants of the housing stock, have to spend a majority of their income on their rents. This is true even for residents who have better paying jobs. Most residents in the area work two or three jobs to be able afford a place to stay.

Hurricane Irma seems to have exacerbated these ever-present issues in the Florida Keys. Although government officials declared that the Keys were ready to host tourists by October 1 (less than a month after the hurricane), a considerable number of businesses, including hotels and restaurants, remain closed as of August 2018 (almost a year after the hurricane). Even governmental departments (e.g., the sheriff’s office, schools) continue to struggle, trying to meet the needs of affected populations with a number of vacant positions as they are unable to find employees who are willing to live in the area due to high cost of living. A county commissioner shared the following story about a bank branch in Key West to demonstrate the peril of the situation in the Keys:

You know it is all over the place. There's a bank branch, of Bank of America branch down here in downtown Key West, but had to close because they couldn't find out tellers. You know. This is this is what we're worried about right now.

In addition, some of the canals are closed due to uncleaned hurricane debris. This has an impact on the fishing industry, which has already suffered significant losses from the hurricane due to damages to boats and lobster traps.

This study revealed that risks associated with sea level rise do not play a direct role in the relocation decisions of Florida Keys residents. People are aware of the potential adverse impacts of this slow-onset hazard. However, they view sea level rise not as a current problem, but as a problem that needs to be dealt with in the future. Their focus is on their relatively urgent, short-term recovery needs (e.g., affordable housing). They do consider the risks of a potential storm or flood, but without relating these risks to sea level rise (even though sea level rise might increase the risks of these immediate hazards).

Although sea level rise risks are more likely to play a role in the relocation decisions of some particular groups (e.g., homeowners, residents whose homes were significantly impacted by the hurricane, and those with a college degree), many of the participants underscore that the residents’ focus is on the next storm rather than on sea level rise itself. Sea level rise concerns have little or no direct impact on relocation decisions. A church member shared her insights on this topic as follows:

If sea level rise is connected with a storm, yeah, I think they're terrified of another storm. I don't know if that connects or not … but…I have not heard one people, one person say, ‘I'm afraid of sea level rise, so I'm leaving.’ I haven't heard anybody say that. But I've heard a lot of people say, ‘if another storm comes I'm out of here.’

Repopulation

Prior studies highlight the importance of attachment to place in affected people’s decisions to return to and/or to rebuild in the same location following a disaster (Ganapati 200951, Morrice 2013). In line with prior studies, most of Florida Keys residents noted that more people decided to stay and repopulate the area following Hurricane Irma, precisely because of their attachment to place. However, their attachment to place seems rather unique. The Keys has a strong identity emerging from its history. Key West, namely Conch Republic, has been the symbol of independence and sovereignty since their victory against mandated roadblocks and inspections in 1982, which were historically carried out by the U.S. government when Keys residents landed on the mainland. The community united and resisted against these inspections, which cemented the ties within the community, and their adoption and attachment to the place (Steinberg, 2009). The community still reflects this strong identity and the spirit of independence. Furthermore, its residents are tightly connected to one other and value their one-of-a-kind environment, surroundings, and the warm climate. When the author requested residents’ reasons for returning to and rebuilding in the area in the aftermath of hurricane, many people underscored the uniqueness of the place. One of the public officials who had lived in the area for a long time expressed his sentiments as follows:

[We stay in the area] Because there’s no community quite like this…You know... where there has this combination of, you know, a gorgeous environment, and you have a 99 percent of the time a very pleasant climate and…and people who really care about each other. So I think those are the factors that make this place unique.

It is important to acknowledge, however, that those who decide to stay and rebuild in the Keys face a variety of challenges during recovery. One of their top challenges relates to homeowner’s insurance. Those who are trying to rebuild their losses through their insurance coverage express significant frustration with the process of communicating and negotiating with their insurance companies. Many suggest that they were not able to receive their full coverage, despite the damages, or that it took a long time for them to get their insurance payments. The challenges of rebuilding are perhaps even more prevalent among those who do not have insurance and those who have to apply for government assistance (e.g., via community outreach representatives, the Florida Division of Emergency Management, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency) or those who seek help from nongovernmental and faith-based organizations. A variety of faith-based or charitable organizations (e.g., the Florida Keys Outreach Coalition, Salvation Army, Keys Strong, church groups, and long-term recovery groups) offer support to affected residents to meet their immediate (e.g., food) or rebuilding (e.g., shelter) needs. However, their efforts seem to fall short.

Another critical challenge faced by those who stayed to rebuild in the Florida Keys after Hurricane Irma relates to the length of the waiting period for building permissions. Although Monroe County waived the fees for building permits initially, on September 27, 2017, the county strictly applied 18 permit types to the rebuilding projects (County Commission Meeting, October 18, 2017). These permit types, combined with an overwhelming number of rebuilding projects in the area and a lack of qualified contractors, have led to long delays in housing reconstruction. This causes additional stress on affected residents. A case worker noted the rebuilding challenges in the area:

I think they're… funding is slow. If they are uninsured, they have to rely on grants or loans. And the construction process with the lack of available contractors. Some people can't…the loans haven't come through yet.

Those who have decided to stay and rebuild in the area are aware of the impacts of sea level rise. They consider those risks indirectly in the context of their homeowner’s and flood insurance policies, preparedness for future storms or floods, and/or in the context of building regulations and restrictions. Existing laws and regulations in the area regulate construction, forbid construction of buildings in flood zones, and require elevation of homes. Although the consideration of sea level rise is likely to be relatively higher in the rebuilding decisions of some populations groups (e.g., younger populations, families with young children, those whose homes were significantly impacted by the hurricane, and high-income groups), it still is not a major concern in the rebuilding process. Homeowners’ focus remains on the affordability of their homeowner’s or flood insurance policies and/or on elevating their homes for future hurricanes. They do not immediately make the connection between sea level rise and hurricanes.

Linking Disaster Recovery with Sea Level Rise Adaptation and Mitigation

The recovery literature lacks long-term environmental concerns associated with climate change and sea level rise. This research contributes to this literature by examining the link between disaster recovery and sea level rise and by analyzing relocation and repopulation decisions of Florida Keys residents. The findings indicate that the residents’ focus is on short-term priorities related to the disaster recovery process (e.g., debris removal from canals) rather than on long-term environmental risks. In the long run, residents would like the government to rebuild the Keys in a more resilient manner while reviving the economy and providing solutions for the affordable housing shortage. However, they have concerns about corresponding building permit restrictions and the possible financial burden on their families (e.g., through higher home and flood insurance rates).

Long-term recovery priorities of the government are sustainable and resilient development, road elevations, fund-raising, and addressing sea level rise in planning and policy formulations. Government officials tend to emphasize that sea level rise is already addressed in their plans, policies, and floodplain zoning practices. However, sea level rise is not included in the Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan (April 2017), where many other types of potential hazards (e.g., tropical storms, floods, terrorist attacks, and nuclear power plant accidents) are listed. In the Monroe County Recovery Plan (April 2017), a variety of elevation requirements for both buildings and infrastructure are presented. However, sea level rise and other adverse impacts of climate change are not addressed. One government official who is actively involved in the community recovery process stated:

Before the storm, our comprehensive plan does [did] address sea level rise. I don’t know if this answers the question with the degree of certainty, but yes our local governments are acknowledging the frame of sea level rise.

The government’s plans and policies have not changed since the hurricane in terms of addressing risks associated with sea level rise. As government officials believe that the potential risks are already addressed through flood zoning and building permits, the government is not likely to review its adaptation or mitigation policies. The attention given to climate change issues may have increased since the hurricane in government circles. However, the attention during recovery seems to focus on addressing the short-term needs of the community. The government views sea level rise as one component in the recovery process. However, sea level rise remains far from being a priority during recovery.

Conclusions: Future Research and Policy Implications

Focusing on the case of Monroe County, Florida, this study examined the link between long-term environmental concerns and the disaster recovery process. It analyzed the extent to which the long-term risks associated with sea level rise contribute to repopulation or relocation decisions of people displaced by disasters in coastal communities. This topic is important not only because it enables us to understand coastal communities’ current and future vulnerabilities to natural hazards, but also because it analyzes post-disaster relocation and rebuilding processes, which present these communities with opportunities to be more adaptive and resilient (Berke et al. 1993, Ganapati and Ganapati 2009, Guarnacci 2012, Vale & Campanella 2005).

The findings of the study mainly show that the Florida Keys residents are aware of sea level rise. However, sea level rise has little to no direct influence on their relocation or repopulation decisions. Although, some of the population groups (e.g., homeowners, residents whose homes were significantly impacted by the hurricane, and those with a college degree) seem more likely to consider long-term environmental risks in their relocation decisions, the difference is negligible. Sea level rise is unlikely to affect the relocation decisions of any particular group of the population. Similarly, sea level rise is not a priority for any of the residents who have returned and rebuilt. As immediate concerns of people affected by disasters are their family members’ short-term needs (e.g., food, shelter, and jobs) following a disaster (Berke et al. 1993, Bolin & Stanford 199152; Ingram et al. 200653), the long-term environmental risks play a minor role in affected populations’ relocation and repopulation decisions. Many of the participants underscore that the focus is on the next storm rather than sea level rise.

The literature suggests that younger populations may be more conscious about environmental deterioration (Dietz et al. 199854, Guagnano & Markee 199555, Schultz 200156) and tend to migrate following a disaster, while elderly populations prefer to stay, hoping to go back to their pre-disaster lives (Levine et al. 2007). In addition to age, studies consider a variety of factors (e.g., education level, household income) that contribute to climate change awareness (Kvaløy et al 201257:, Lee et al. 201558). Although some of these factors (e.g., education level, income level) seem to have slightly contributed to the residents’ level of concern in the Florida Keys, they were unlikely to have influenced the relocation or repopulation decisions of any specific population group.

Displaced populations get back to their “new normal” in the aftermath of the hurricane focusing on their short-term, immediate needs. In the Florida Keys, residents are trying to cope with pre-disaster challenges that were exacerbated after the hurricane (specifically a lack of affordable housing and low paying jobs) and the risks associated with potential storms. Policymakers need to find a delicate balance while linking long-term environmental risks into the disaster recovery process. They must find the optimum period to act on sea level rise adaptation and mitigation in the aftermath of a disaster. They should take long-term risks into consideration soon after addressing the immediate needs in the community, but while the collective memory of the disaster is still present. To address long-term environmental risks in disaster recovery processes and build resilient communities, local officials need funding support from upper levels of the government (state and federal). They also need public support for their policies (e.g., perhaps through public awareness campaigns).

This study focused on the unique recovery case of the Florida Keys. It was designed as an initial step toward a more comprehensive research project on sea level rise and disaster recovery that the author plans to conduct. The study’s sample was relatively small, although it allowed for the capture of the relocation and repopulation perspectives of Florida Keys residents. Future studies can focus on other coastal areas that are affected by disasters. One example is North Carolina. According to a recent survey conducted after Hurricane Florence (Mandel 201859), more North Carolina residents now link climate change and disasters and call for their elected officials to act on climate change. There is also a need for longitudinal studies that can examine the role of sea level rise risks associated with relocation and repopulation decisions of residents of disaster stricken communities over time. Future studies could also conduct surveys with residents of disaster stricken communities to measure the impact of sea level rise in their decision making processes related to relocation and repopulation in a quantitative manner.

This research fills a significant theoretical gap in post-disaster recovery and sea level rise literature by linking them together and offers future directions for research. It also provides policy guidance to policymakers at local, state, and federal levels on how they can better address long term vulnerabilities associated with sea level rise in disaster-affected and disaster-prone communities. It aims to help them create more resilient coastal communities in the most densely populated counties in the United States (Fitzgerald et al., 2008). The study also informs those who are displaced by disasters on their decision-making processes related to repopulation and relocation.

References

-

IPCC. (2007). Summary for Policy Makers, in S Solomon, D Qin, M Manning, Z Chen, M Marquis, K B Averyt, M Tignor and H L Miller (editors), Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York. ↩

-

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2014). Working Group II,. Climate Change 2014. Impacts, Adaption, and Vulnerability. ↩

-

Tacoli, C. (2009). Crisis or adaptation? Migration and climate change in a context of high mobility. Environment and urbanization, 21, no. 2: 513-525. ↩

-

Myers, N. (2002). Environmental refugees: a growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 357, no. 1420: 609-613. ↩

-

International Organization on Migration. (2008). Migration and climate change. In: Migration Research Series No. 31, Geneva. ↩

-

Environmental Migration Portal. (2018). ENVIRONMENTAL MIGRATION | Environmental Migration Portal. Accessed June 01, 2018. https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/environmental-migration. ↩

-

International Organization on Migration. (2011). Glossary on Migration, 2nd Edition. International Migration Law No. 25, IOM, Geneva. Accessed May 15,2018. http://publications.iom.int/bookstore/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=56&products_id=1380 ↩

-

Warner, K., Hamza, M., Oliver-Smith, A., Renaud, F. and Julca, A. (2010). Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Natural Hazards, 55, no. 3: 689-715. ↩

-

Black, R., Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., Dercon, S., Geddes, A., and Thomas, D. (2011). The effect of environmental change on human migration. Global environmental change, 21: S3-S11. ↩

-

Gotham, K. F. (2017). The elusive recovery: Post-hurricane Katrina rebuilding during the first decade, 2005–2015. 138-145. ↩

-

Fothergill, A. & Peek, L. A. (2004). Poverty and disasters in the United States: A review of recent sociological findings. Natural hazards, 32, no. 1: 89-110. ↩

-

Fothergill, A. & Peek, L. (2015). Children of Katrina. University of Texas Press. ↩

-

Fussell, E., Sastry, N., and VanLandingham, M. (2010). Race, socioeconomic status, and return migration to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Population and environment, 31, no. 1-3: 20-42. ↩

-

Mazzei, P. & Robles, F. (2017, December 18). Puerto Rico Orders Review and Recount of Hurricane Deaths. The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/12/08/us/puerto-rico-hurricane-maria-death-toll.html ↩

-

Kishore, N., Marqués, D., Mahmud, A., Kiang, M. V., Rodriguez, I., Fuller, A., Ebner, P. et al. (2018). Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. New England journal of medicine, 379, no. 2: 162-170. ↩

-

Matthews, D. (2017, October 5). What the Hurricane Maria migration will do to Puerto Rico - and the US. Vox. Retrieved from: [https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/10/5/16403952/hurricane-maria-puerto-rico-migration, date of access: 11/01/2018](https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/10/5/16403952/hurricane-maria-puerto-rico-migration, date of access: 11/01/2018). ↩

-

American Fact Finder. (2017). Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017. Retrieved from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=PEP_2017_PEPANNRES&prodType=table, date of access: 11/03/2018. ↩

-

O'Hara, T. (2018, October 22). Keys population drops after Irma. Key West Citizen. Retrieved from: https://keysnews.com/article/story/keys-population-drops-after-irma/, date of access: 10/23/2018 ↩

-

Berke, P. R., Kartez, J., and Wenger, D. (1993). Recovery after disaster: achieving sustainable development, mitigation and equity. Disasters, 17, no. 2: 93-109. ↩

-

Ganapati, N. E., & Ganapati, S. (2008). Enabling participatory planning after disasters: A case study of the World Bank's housing reconstruction in Turkey. Journal of the American Planning Association, 75, no. 1: 41-59. ↩

-

Guarnacci, U. (2012). Governance for sustainable reconstruction after disasters: Lessons from Nias, Indonesia. Environmental Development, 2 73-85. ↩

-

Vale, L. J. & Campanella, T. J. (2005). The resilient city: How modern cities recover from disaster. Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Titus, J. G. (1989). The causes and effects of sea level rise. The challenge of global warming: 161-195. ↩

-

Bray, M., Hooke, J., and Carter, D. (1997). Planning for sea-level rise on the south coast of England: advising the decision-makers. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 13-30. ↩

-

Dasgupta, S., Laplante, B., Meisner, C., Wheeler, D., and Yan, J. (2007). The impact of sea level rise on developing countries: a comparative analysis. The World Bank. ↩

-

Houghton, J. T. (1992). Callander, BA & Varney, SK, eds. Climate Change 1992: The Supplementary Report to the IPCC Scientific Assessment. ↩

-

Karim, M. F., & Mimura, N. (2008). Impacts of climate change and sea-level rise on cyclonic storm surge floods in Bangladesh. Global Environmental Change, 18, no. 3: 490-500. ↩

-

Mimura, N. (1999). Vulnerability of island countries in the South Pacific to sea level rise and climate change. Climate research, 12, no. 2-3: 137-143. ↩

-

Tol, R. S.J., Klein, R. J. T., and Nicholls, R.J. (2008). Towards successful adaptation to sea-level rise along Europe's coasts. Journal of Coastal Research: 432-442. ↩

-

Warrick, R. A. (1993). Slowing global warming and sea-level rise: the rough road from Rio. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 18, no. 1: 140-148. ↩

-

Wu, S., Yarnal, B. and Fisher, A. (2002). Vulnerability of coastal communities to sea-level rise: a case study of Cape May County, New Jersey, USA. Climate Research, 22, no. 3: 255-270. ↩

-

Migration Data Portal. (2018). Environmental Migration | Migration Data Portal. Accessed: May 2018 https://migrationdataportal.org/themes/environmental_migration ↩

-

Burton, I. (1993). The environment as hazard. Guilford press. ↩

-

Clark, G. E., Moser, S. C., Ratick, S. J., Dow, K., Meyer, W. B., Emani, S., Jin, W., Kasperson, J. X., Kasperson, R. E., and Schwarz, H. E. (1998). Assessing the vulnerability of coastal communities to extreme storms: the case of Revere, MA., USA. Mitigation and adaptation strategies for global change ,3, no. 1: 59-82. ↩

-

Landry, C. E., Bin, O., Hindsley, P., Whitehead, J. C., and Wilson, K. (2007). Going home: Evacuation-migration decisions of Hurricane Katrina survivors. Southern Economic Journal 326-343. ↩

-

Morrice, S. (2013). Heartache and Hurricane Katrina: recognising the influence of emotion in post‐disaster return decisions. Area 45, no. 1: 33-39. ↩

-

Myers, C. A., Slack, T., and Singelmann, J. (2008). Social vulnerability and migration in the wake of disaster: the case of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Population and Environment, 29, no. 6: 271-291. ↩

-

FitzGerald, D. M., Fenster, M. S., Argow, B. A., and Buynevich, I. V. (2008). Coastal impacts due to sea-level rise. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 36. ↩

-

Esnard, A, & Sapat, A. (2014).Displaced by disaster: Recovery and resilience in a globalizing world. Routledge. ↩

-

Esnard, A., Sapat, A., and Mitsova, D. (2011). An index of relative displacement risk to hurricanes. Natural hazards, 59, no. 2: 833. ↩

-

Levine, J. N., Esnard, A., and Sapat, A. (2007). Population displacement and housing dilemmas due to catastrophic disasters. Journal of planning literature, 22, no. 1: 3-15. ↩

-

Wadlow, K. (2018, October 22). The parks in the Keys took a big hit - and won’t be the same for months. Miami Heralds. Retrieved from: [http://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/florida-keys/article177718921.html, date of access: 11.25.2017](http://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/florida-keys/article177718921.html, date of access: 11.25.2017) ↩

-

Zhang, K., Dittmar, J., Ross, M., and Bergh, C. (2011). Assessment of sea level rise impacts on human population and real property in the Florida Keys. Climatic Change, 107, no. 1-2: 129-146. ↩

-

Flugman, E., Mozumder, P., and Randhir, T. (2012). Facilitating adaptation to global climate change: perspectives from experts and decision makers serving the Florida Keys. Climatic Change, 112, no. 3-4: 1015-1035. ↩

-

Ross, M. S., O'Brien, J. J., Ford, R. G., Zhang, K., and Morkill, A. (2009). Disturbance and the rising tide: the challenge of biodiversity management on low‐island ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7, no. 9: 471-478. ↩

-

Baumgard, J. (2017,September 5). Florida Keys to reopen to tourists on Oct 1. Curbed Miami. Retrieved from: https://miami.curbed.com/2017/9/5/16257912/hurricane-irma-miami-florida, date of access: 10/25/2017. ↩

-

Mak, A. (2017,September 12). The Latest Reports of Damage in the Parts of Florida Hit Hardest by Irma. Slatest. Retrieved from: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2017/09/damage-reports-from-areas-of-florida-hit-hardest-by-hurricane-irma.html. Date of access: 10/30/2017. ↩

-

City of Marathon Damage Assessment Report thru 11/26/2017 ↩

-

American Fact Finder. (2017). OCCUPANCY STATUS: Housing units 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Retrieved from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_B25002&prodType=table ↩

-

Ganapati, N. E. (2009). Rising from the rubble: Emergence of place-based social capital in Golcuk, Turkey. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 27, no. 2: 127-166. ↩

-

Bolin, R., & Stanford, L. (1991). Shelter, housing and recovery: A comparison of US disasters. Disasters ,15, no. 1: 24-34. ↩

-

Ingram, J. C., Franco, G., Rumbaitis-del Rio, C., and Khazai, B. (2006). Post-disaster recovery dilemmas: challenges in balancing short-term and long-term needs for vulnerability reduction. Environmental science & policy, 9, no. 7-8: 607-613. ↩

-

Dietz, T., Stern, P. C., and Guagnano, G. A. (1998). Social structural and social psychological bases of environmental concern. Environment and behavior, 30, no. 4: 450-471. ↩

-

Guagnano, G. A., and Markee, N. (1995). Regional differences in the sociodemographic determinants of environmental concern. Population and Environment, 17, no. 2: 135-149. ↩

-

Schultz, P. W. (2001). The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. Journal of environmental psychology, 21, no. 4: 327-339. ↩

-

Kvaløy, B., Finseraas, H., and Listhaug, O. (2012). The publics’ concern for global warming: A cross-national study of 47 countries. Journal of Peace Research, 49, no. 1: 11-22. ↩

-

Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C., and Leiserowitz, A. A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature climate change ,5, no. 11: 1014. ↩

-

Mandel, K. (2018, October 5, ). North Carolina voters are worried about climate change after Florence. Think Progress. Retrieved from: https://thinkprogress.org/poll-north-carolina-voters-climate-change-florence-79ed3f59f78e/, date of access: 10/30/2018 ↩

Kuru, O. D. (2019). Relocation, Repopulation, and Rising Seas: Monroe County, Florida, Following Hurricane Irma (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 290). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/relocation-repopulation-and-rising-seas