Renter Experiences After Colorado’s Marshall Fire

Publication Date: 2023

Abstract

The Marshall Fire (2021) damaged or destroyed at least 1,233 homes in Colorado, the most destructive wildfire in state history. In the aftermath of the fire, our research group coordinated a national team of researchers to survey residents of the three jurisdictions at multiple time points. By recruiting participants through two distinct channels, we assembled a diverse sample of residents living in affected areas at the time of the fire, including 199 renters—a group that faces distinct and often overlooked challenges during disaster recovery. Using survey data collected 11-15 months after the fire, this report highlights renters’ experiences related to disaster impacts, displacement, rent increases, access to resources and support, and participation in decision-making channels. We find several significant differences between homeowners and renters. Renters were more economically and racially diverse than homeowners, were less likely to be living in fire-damaged homes, and were more likely to have been displaced outside the county. Renters also report being in greater need of financial support, are less insured, and are more supportive of policies that create permanent affordable housing. Importantly, renters report being less engaged in the recovery policymaking process, and were less confident that their voices were being heard or that the recovery process had been fair. These findings are important for recovery decision-makers who are working to create inclusive and equitable plans, programs, and policies.

Introduction

On December 30, 2021, the climate-enabled and weather-driven Marshall Fire destroyed 1,084 homes in the communities of Louisville, Superior, and unincorporated Boulder County, becoming the most destructive fire in Colorado’s history. An unusually wet spring followed by an extremely dry July to December created abundant dry grasslands along the foothills of Boulder County, setting the stage for hurricane-force winds over 100 miles per hour to carry a fire that ignited in the western part of the county to rapidly spread through open space into suburban neighborhoods not previously thought to be in the “wildland-urban interface” (Scott, 20221). The destruction was over in a matter of hours. The fire started in the early afternoon, and by about 8 pm the winds shifted and snow began to fall, leaving thousands of people displaced and left to grapple with the long road to recovery.

While considerable and needed attention has been given to homeowners who lost homes in the fire, a substantial number of renters were also impacted. Because the jurisdictions that were affected by the Marshall Fire do not routinely require rental licensing, official counts of the number of rental properties affected are not available. However, local media and advocacy group reports document numerous challenges facing renters in the area, including price gouging, retaliation, and smoke damage (Brown, 20222; East County Housing Opportunity Coalition, 20223).

The Marshall Fire Research Unified Survey Working Group formed in early 2022 with the goal of gathering perishable data on disaster impacts, the recovery process, and policy change through longitudinal surveys of residents in areas affected by this disaster. In this report, we present findings from the second wave of data collection, which occurred between November of 2022 and April of 2023, a period spanning the one-year anniversary of the fire. By leveraging two sampling approaches—including an address-based method and Boulder County’s official list of affected residents—we have succeeded in gathering data from a diverse sample of affected residents, including nearly 200 renters. In this report we analyze these data to assess how renters have been affected by the Marshall Fire, and how those impacts compare to homeowner experiences. These results highlight some key challenges renters are facing, including how many report feeling “sidelined” in the response and recovery process. Drawing on these results, we outline possible directions for action to promote a more equitable recovery.

Literature Review

Housing tenure refers to the “legal status under which people have the right to occupy their accommodation” (Wegmann et al., 20174). Housing tenure is a relatively understudied dimension of social vulnerability to natural hazards and disasters compared to other factors like income, age, and race/ethnicity (Lee & Van Zandt, 20195). Researchers have long understood, axiomatically, that reestablishing permanent housing is a fundamental requirement for household and community recovery post-disaster (Bolin, 19936; Bolin & Stanford, 19917; Comerio, 20148; Rodríguez et al., 20079). While earlier studies tended to focus on the recovery of housing units, more recent research has examined the variations in disaster recovery experiences among households with different tenure arrangements (e.g., Emrich et al., 202010; Green & Olshansky, 201211; Peacock et al., 200612). Broadly speaking, housing tenure is often strongly correlated with other characteristics of social vulnerability like income, housing quality, race/ethnicity, disability, and immigration status, and these factors can operate together to compound risk (Lee & Van Zandt, 2019).

Numerous studies show that renters face unique barriers to recovery that are rooted in tenure status. Disaster recovery programs and policies have historically centered on housing unit owners, such as providing resources that seek to bridge the gap between a homeowners’ resources and recovery costs (Dundon & Camp, 202113; Olshansky & Johnson, 201414; Spader & Turnham, 201415). Renters living in damaged properties must rely on landlords to make repairs, which can prolong their displacement and delay their recovery. Depending on the state, renters may also face higher likelihood of eviction post-disaster, as housing unit owners seek to capitalize on increasing market prices or choose to sell their properties (Brennan et al., 202216; Raymond et al., 202217). Not surprisingly, then, research on household recovery trajectories has often found that renters—including public housing tenants—face a higher likelihood of displacement after a disaster or are slower to return to their communities than homeowners (Fussell & Harris, 201418; Kammerbauer & Wamsler, 201719; Khajehei & Hamideh, 202320).

Disasters can also affect residents’ mental health outcomes in complex and long-lasting ways, and the challenges faced by renters can have important mental health implications. Studies from fires in California and Australia underscore the potential for high rates of depression and PTSD months after a fire, especially among those experiencing property loss (Bryant et al., 201821; Macleod et al., 202322; Silveira et al., 202123; Xu et al., 202024). Higher rates of suicidal thoughts and increased substance use have also been reported among fire-affected communities compared to nearby areas (Brown et al., 201925). Research indicates that homeowners and renters have different mental health outcomes in response to natural hazards (Baryshnikova & Pham, 201926). Ongoing displacement after such events has been associated with worse mental health (Fussell & Lowe, 201427). Decision-makers in a post-disaster context face the difficult task of crafting recovery policies that meet the diverse needs of affected residents, and often these decisions are shaped by input and participation among different groups facing different types of disaster impacts. To the extent that renters’ experiences and needs differ from those of homeowners, it is important to understand patterns of participation in post-disaster decision-making by housing tenure. In a general, non-disaster context, evidence shows that people who participate in local planning and zoning meetings tend to be homeowners rather than renters, and overrepresent older and male demographics (Einstein et al., 201828). Post-disaster, these gaps may widen as socially vulnerable groups face numerous barriers to participation, including greater likelihood of displacement and social stigma or power differentials (Hamideh & Rongerude, 201829).

Our review of the literature shows that research which specifically focuses on the experiences of renters post-disaster (as opposed to rental housing units) is still relatively rare, and important questions remain largely unexplored—such as renters’ pace of recovery, their likelihood of displacement, impacts of disasters on mental health outcomes, and renters’ engagement in post-disaster planning, policy and decision-making processes

Research Questions

This research explores how the Marshall Fire affected community members, and how recovery outcomes vary across groups and over time. This report focuses on housing tenure to address the following research questions:

- How do disaster impacts and recovery outcomes vary with housing tenure?

- What factors affect individuals’ participation in recovery decision-making processes, and how do participation and policy support vary with housing tenure?

Research Design

Soon after the Marshall Fire, our research group brought together over 30 researchers to design and implement a collaborative, unified longitudinal survey of disaster survivors in the three impacted jurisdictions: Louisville, Superior, and unincorporated Boulder County. The survey examines a wide range of themes: information about residents’ homes and fire impacts; evacuation and emergency alerts; environmental impacts and remediation post-fire; rebuilding, reconstruction, and relocation decisions; participatory processes and policy support; reminders of the fire; social capital, connections, and support; physical and mental health effects; and worldview and demographic questions. Our data collection methods were designed to collect perishable information from residents of the areas affected by the Marshall Fire, with a goal of gathering a range of experiences and perspectives that were likely to vary with both individual characteristics and the types of impacts experienced.

Data Collection Methods

Survey recruitment and implementation occurred over multiple waves and through two main sampling and recruitment procedures. We refer to these as the “Perimeter Sample” and the “BoCo Sample.”

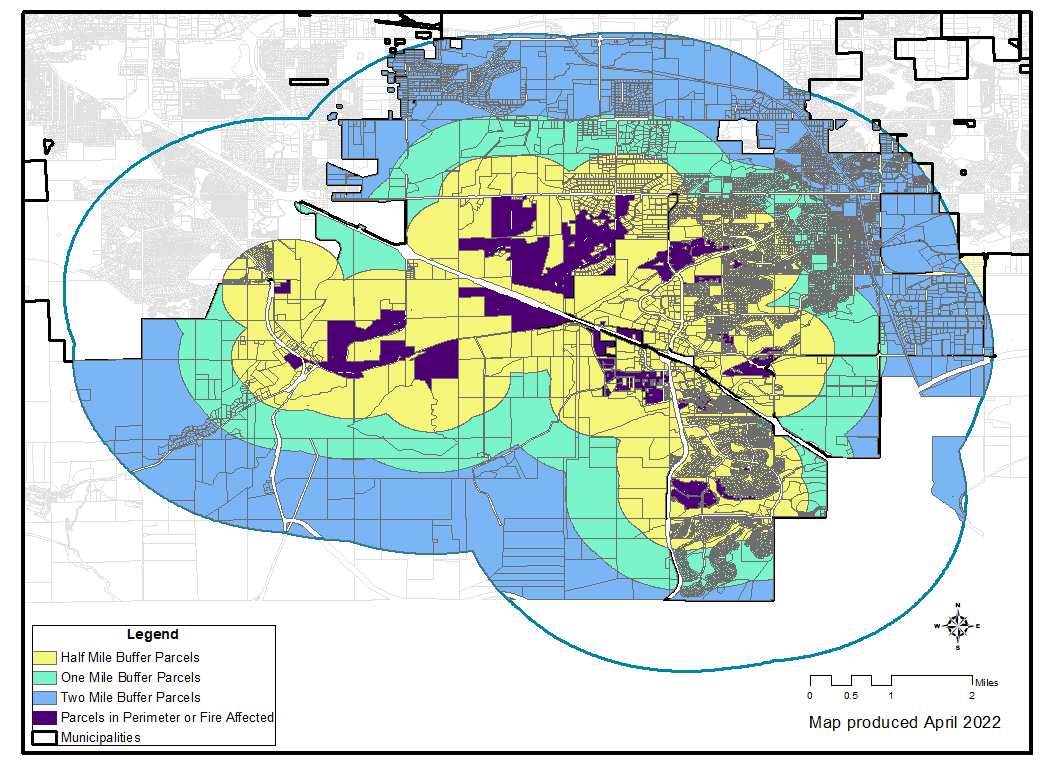

Perimeter Sample Recruitment. In the immediate aftermath of the Marshall Fire, our study team hoped to recruit participants through official lists of disaster-affected residents. However, local officials with access to these lists were focused on disaster response and were unresponsive to requests to share these lists. For this reason, and because we sought to sample residents with varying levels of exposure to and impacts from the fire, we proceeded with our Perimeter Sample strategy. Using publicly available tax parcel data and Boulder County’s fire perimeter GIS shapefile, we sampled addresses in four tiers or buffers (see Figure 1). The first tier included everyone that lived within the fire perimeter (N=1960), while the remaining three tiers included random samples of households within increasing distance buffers from the perimeter: within .5 of a mile (N=700), .5 to 1 mile (N=399), and 1 to 2 miles (N=383), for a total of 3,443 recruitment addresses.

Figure 1. Buffered Sampling Frame for the Perimeter Sample

In May 2022, about five months after the fire, the first survey invitation was mailed to households using a mail processing center to identify forwarding addresses, a crucial step given the large number of destroyed homes and displaced residents. The invitation letter contained a web address and QR code to access the online Qualtrics survey. Two reminder letters were sent to participants. Those who completed the survey received a gift card ($15 for those within the fire perimeter, $10 for those outside the perimeter) to a local business (either a grocery store or coffee shop). Wave 1 Perimeter survey data collection continued through July 2022.

In mid-November, we launched a Wave 2 survey, recruiting all individuals who completed Wave 1 and agreed to be recontacted. Recruitment was conducted by email or mail (depending on respondent preference from the Wave 1 survey), and a similar incentive structure was used. Data collection for the Wave 2 Perimeter survey continued through March 2023.

BoCo Sample Recruitment. Meanwhile, our team continued to engage with local officials and recovery groups to share results from the Wave 1 Perimeter survey and elicit input for the Wave 2 survey. Heading into the second year of the recovery process, several members of these local groups expressed a need for data capturing a larger proportion of affected residents, and therefore we expanded our recruitment to include individuals on the county’s contact list of affected residents. We submitted a request for the list of residents who had applied for financial assistance from Boulder County’s Disaster Assistance Center between December 30, 2021 (the date of the fire) and February 2023 (the date of our data request). This list included email addresses for most individuals. Next, we cross-referenced the list with our original Perimeter Sample and removed contacts that had completed our Wave 1 survey. We also randomly sampled one individual per household and removed contacts without a valid email address. This resulted in a list of 2,941 individuals, all of whom were recruited by email with a link to the online Qualtrics survey. All BoCo respondents received a $15 gift card to a local grocery store. Data collection began in early March 2023 and concluded in April 2023.

Data Analysis Procedures

For this report, we focus our analysis on the data from the second wave of data collection, which includes the Perimeter Sample Wave 2 data and the BoCo Sample. Descriptive statistics from the Perimeter Sample Wave 1 dataset are also provided for reference. Using the Wave 2 datasets, we computed descriptive statistics and conducted bivariate and multivariate analysis to examine variation in key disaster-related outcomes by housing tenure; specifically, we compare renters with homeowners.

Ethical Considerations and Researcher Positionality

From the outset, our research team has strived to conduct this research in an ethical, trauma-informed, and participant-driven manner. Our research team includes members with close ties to the impacted communities. Co-author Dickinson is a social science researcher and a Louisville resident who evacuated during the Marshall Fire. While her home was spared, she saw and understood the depth of the disaster’s impacts firsthand and cared deeply about conducting research that could help her community and others recover while promoting participants’ well-being and avoiding overburdening impacted community members. Similarly, co-authors Crow, Rumbach, and Albright all have Colorado ties and expertise in disaster policy research. Our desire to conduct robust and ethical research drove the formation of the Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey Working group, which convened our core team along with over 30 researchers across the country who expressed interest in collecting survey data in the aftermath of the Marshall Fire. By collaboratively developing and implementing the Marshall Fire Unified Survey, rather than having each team develop their own survey, we sought to minimize research burdens for affected residents while also leveraging the interdisciplinary expertise of the Working Group that would allow comprehensive analyses of the disasters’ impacts and recovery processes over time. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #22-0085).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents sample sizes, response rates, and descriptive statistics for the Perimeter Sample (Wave 1 and Wave 2), the BoCo Sample, and a combined sample for Wave 2 that includes both Perimeter and BoCo respondents.

For the Perimeter Sample, our Wave 1 response rate was about 24% for a total of 823 complete and usable responses. Of those, 799 were from individuals that reported that the address affected by the fire was their primary residence. For Perimeter Wave 2, 577 individuals completed the survey (70% response rate or 30% attrition), of whom 565 were individuals whose primary residence was affected. The response rate for the BoCo sample was slightly higher (26%) for a total of 769 respondents (768 primary residence). The distribution of respondents across the three jurisdictions affected by the Marshall Fire is similar across samples, with roughly half of respondents living in Louisville at the time of the fire compared to 10-14% from Unincorporated Boulder County and 30-39% from Superior.

Table 1. Characteristics the Perimeter, BoCo, and Combined Surveys

| Perimeter Sample | BoCo Sample | Combined Wave 2 (Perimter + BoCo) |

|||

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |||

| Dates | 5/12 - 7/21/22 | 11/11/22 - 3/27/23 | -- | 3/1 - 4/25/23 | 11/11/22 - 4/25/23 |

| Recruits | 3443 | 823 | -- | 2941 | 3764 |

| Total Responses | 823 | 577 | 247 | 769 | 1346 |

| Response Rate | 24.2% | 70.0% | 30.0% | 26.2% | 35.8% |

| Primary Residence Responses* | 799 | 565 | 29.3% | 768 | 1333 |

| Jurisdiction | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Attrition | BoCo | Combined Wave 2 |

| Unincorporated Boulder Co | 95 (11.9) | 58 (10.3) | 38.9% | 111 (14.5) | 169 (12.7) |

| Louisville | 394 (49.3) | 286 (50.6) | 27.4% | 425 (55.0) | 709 (53.2) |

| Superior | 310 (38.8) | 221 (39.1) | 28.7% | 234 (30.5) | 455 (34.1) |

| Impact of Marshall Fire | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Attrition | BoCo | Combined Wave 2 |

| Complete loss | 208 (26.0) | 162 (28.7) | 22.1% | 299 (39.0) | 461 (34.6) |

| Damaged, not living there | 39 (4.9) | 32 (5.7) | 17.9% | 89 (11.6) | 121 (9.1) |

| Damaged, living there | 357 (44.7) | 243 (43.0) | 31.9% | 325 (42.3) | 568 (42.6) |

| No damage, living there | 193 (24.2) | 126 (22.3) | 34.7% | 49 (6.4) | 175 (13.1) |

| No damage, not living there | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 0% | 6 (0.8) | 8 (0.6) |

| Ownership status | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Attrition | BoCo | Combined Wave 2 |

| Primary residence, homowner | 767 (96.0) | 543 (94.1) | 29.2% | 591 (77.0) | 1134 (85.1) |

| Primary residence, renter | 32 (4.0) | 22 (3.8) | 31.3% | 178 (23.0) | 199 (14.9) |

| Gender | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Attrition | BoCo | Combined Wave 2 |

| Female | 461 (57.7) | 344 (60.9) | 25.4% | 412 (53.7) | 756 (56.7) |

| Male | 286 (35.8) | 196 (34.7) | 31.5% | 263 (34.2) | 459 (34.4) |

| Non-binary/transgender/other or declined | 52 (6.5) | 25 (4.4) | 51.9% | 93 (12.1) | 118 (8.9) |

| Age | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Attrition | BoCo | Combined Wave 2 |

| 18-34 | 58 (7.3) | 36 (6.4) | 37.9% | 77 (10.0) | 113 (8.5) |

| 35-54 | 305 (38.2) | 225 (39.8) | 26.2% | 292 (38.0) | 517 (38.8) |

| 55+ | 377 (47.2) | 278 (49.2) | 26.3% | 298 (38.8) | 576 (43.2) |

| Missing | 59 (7.4) | 26 (4.6) | 55.9% | 101 (13.2) | 127 (9.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Attrition | BoCo | Combined Wave 2 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 667 (83.5) | 495 (87.6) | 25.8% | 557 (72.5) | 1052 (78.9) |

| Persons of Color | 74 (9.3) | 46 (8.1) | 37.8% | 104 (13.5) | 150 (11.3) |

| Missing | 58 (7.3) | 24 (4.3) | 58.6% | 107 (13.9) | 131 (9.8) |

| Income | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Attrition | BoCo | Combined Wave 2 |

| Less than $75K | 92 (11.5) | 65 (11.5) | 29.3% | 189 (24.6) | 254 (19.1) |

| $75K-$149K | 204 (25.5) | 151 (26.7) | 26.0% | 184 (24.0) | 335 (25.1) |

| $150K-$200K | 118 (14.8) | 94 (16.6) | 20.3% | 82 (10.7) | 176 (13.2) |

| $200K or more | 205 (25.7) | 148 (26.2) | 27.8% | 138 (18.0) | 286 (21.5) |

| Missing | 180 (22.5) | 107 (18.9) | 40.6% | 175 (22.8) | 282 (21.2) |

The BoCo Sample includes a higher proportion of people who experienced direct damages from the Marshall Fire, which is not surprising given that this sample is comprised of people who signed up with Boulder County for disaster assistance while the Perimeter Sample includes random samples of the affected communities at varying distances from the fire. For example, about 40% of BoCo respondents suffered a complete loss of their homes, compared to 25% of Perimeter Wave 1 respondents.

Another key difference between these samples is the significantly higher proportion of renters versus homeowners in the BoCo sample (20%) compared to the Perimeter sample (4%). While the Perimeter sampling frame included all residential properties in the relevant buffer areas, including rental properties, two factors may have contributed to the small proportion of renters in the sample. First, forwarding mail addresses for renters may have been less reliable than for homeowners. Second, mail for properties where the owner’s mailing address did not match the property address—which were likely rentals—was addressed to “Resident” rather than the property owner’s name. People may be less likely to open mail that is addressed to “Resident.” In contrast, the BoCo contact list was recruited by email and included people who had already signed up for disaster assistance. This likely removed some barriers to renters’ participation and led to the higher proportion of renters in this sample. The Combined Wave 2 dataset includes 199 renters, a robust sample that can shed light on disaster impacts and outcomes in this important group. We examined renter demographics and assessed several measures of disaster and recovery outcomes in this group, using the Combined Wave 2 dataset.

Demographics of Renters Versus Homeowners

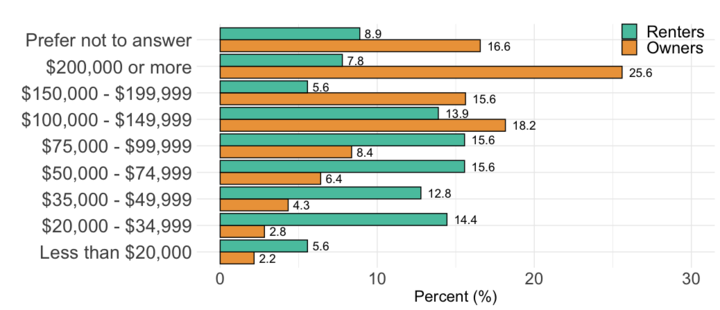

Not surprisingly, renters and homeowners in our sample differ in terms of several demographic characteristics. Compared to homeowners, renters are younger (average age of 43 versus 55 for homeowners), more likely to be people of color (20% versus 11%) and have lower incomes (average income of $50,000-$75,000 versus $100,000-$150,000 for homeowners). See Figure 2 for income distribution for renters versus homeowners.

Figure 2. Income Distribution for Renters Versus Homeowners

Disaster Impacts

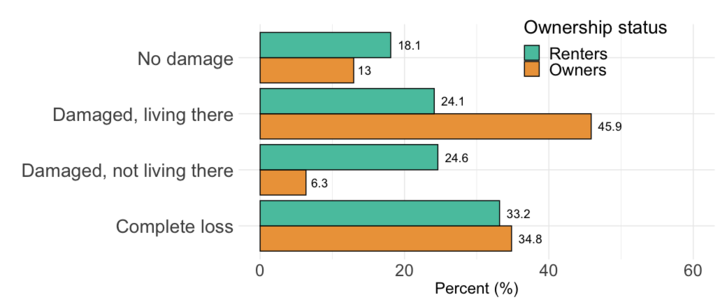

Homeowners and renters in our sample also differ in terms of the level of disaster impacts they experienced, as demonstrated in Figure 3. About a third of both renters (33.2%) and homeowners (34.8%) in our Combined Wave 2 sample suffered a complete loss of their primary residence due to the Marshall Fire. However, significantly more renters reported that they experienced damage to their home and were no longer living at the same place where they were living at the time of the fire (24.6% versus 6.3%), and conversely, more homeowners reported that they were still living at the same property but had experienced fire damage (45.9%). (We note that “damage” is a broad category in the context of this survey and includes everything from minor smoke or ash in the home to major structural damage.)

Figure 3. Marshall Fire Impacts by Housing Tenure

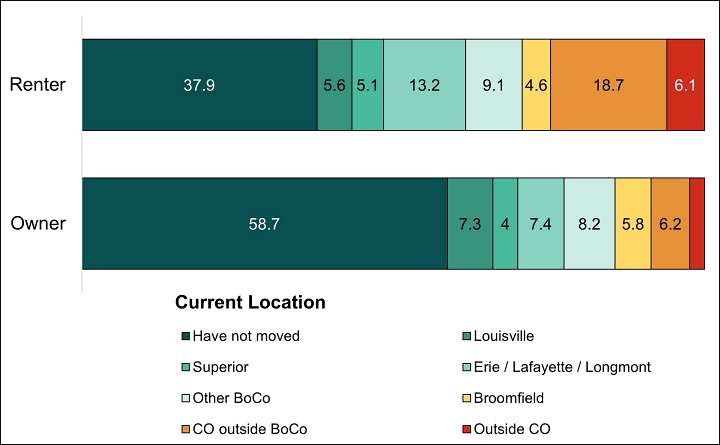

Displacement

Overall, about 62% of renters in our Combined Wave 2 sample (survey distributed 11-15 months after the fire) have moved and are not living at the same property they lived in at the time of the fire. In contrast, nearly 60% of homeowners still live at the same property. Figure 4 shows the location of renters and homeowners in the sample at the time of the Wave 2 survey. A larger proportion of renters left Boulder County—about a year after the fire, 4.6% of renters were living the nearby City and County of Broomfield, while 18.7% were living elsewhere in Colorado, and 6.1% had moved out of state, for a total of 29.4% of renters living outside Boulder County. In contrast, only 14.4% of homeowners had left Boulder County.

Figure 4. Renter and Homeowner Locations at the Time of the Wave 2 Survey

Rent Increase

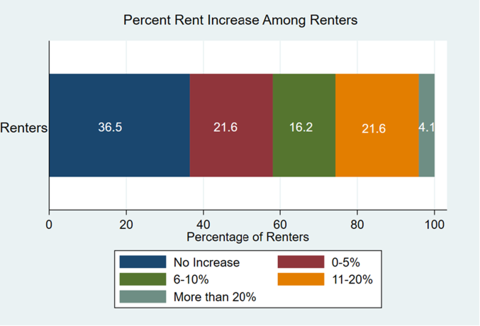

For the 75 renters (38%) that were still living at the same property as before the Marshall Fire, 63% reported that their landlord had raised their rent after the fire (see Figure 5). Sixteen (21.6%) had their rent raised less than 5%, 16.2% saw increases of 6-10%, 21.6% saw increases of 11-20%, and 6% had their rents raised more than 20%.

Figure 5. Rent Increases for Renters Who Did Not Move

We also asked renters who had not experienced a complete loss but had moved from their pre-fire homes to rate the importance of different factors in their moving decision. Of the 56 renters in this category, 75% rated “housing costs” as somewhat or very important in their moving decision.

Insurance

Most homeowners and renters in our sample who experienced damage to their homes during the fire reported that they were insured. However, while 97% of homeowners reported having homeowners’ insurance, the proportion of insured renters was 70%.

Access to Support

About 60% of renters said they needed some type of emotional support after the fire and 74% needed material support. Of these, 17% said they had not received the emotional support they needed, and the same proportion had not received sufficient material support. By comparison, 45% of homeowners needed emotional support and 9% said they had not received that support, while 57% needed material support and 10% had not received that support.

Mental Health

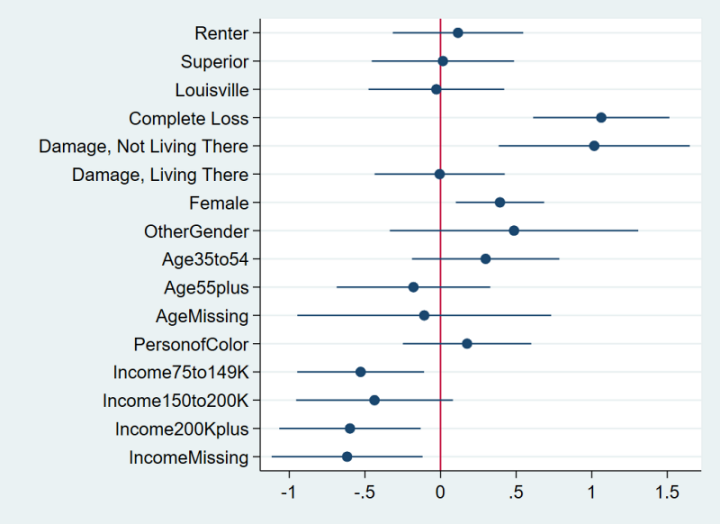

We asked respondents to report their level of distress using the following question: “Please describe how much distress you have been feeling overall in the past week, where 0 = things are good, 10 = I feel as bad as I have ever felt.” On average, renters reported a distress level of 3.65 on this scale while homeowners report a 3.12 (ttest pvalue=0.007). In a multivariate regression controlling for level of damage and demographics, the difference in distress level between homeowners and renters was not statistically significant (see Figure 6). We do observe that individuals who experienced complete loss and those who had damage to their home and were not living there reported significantly higher distress levels than those who experienced no damage. Females also reported higher levels of distress, and income categories above $75,000 reported lower distress those with income less than $75,000.

Figure 6. Multivariate Regression Results for Distress (0 to 10 Scale)

Policy Participation and Support

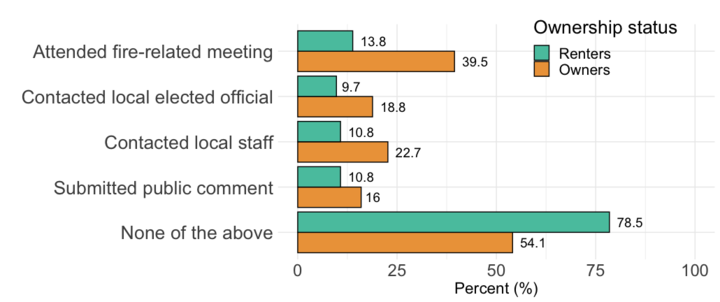

We assessed respondents’ levels of participation in local decision-making after the fire. Results show that renters were significantly less likely to have participated through multiple channels, including attending fire-related meetings, contacting local officials or staff, or submitting public comment (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Participation in Local Decision-Making by Housing Tenure

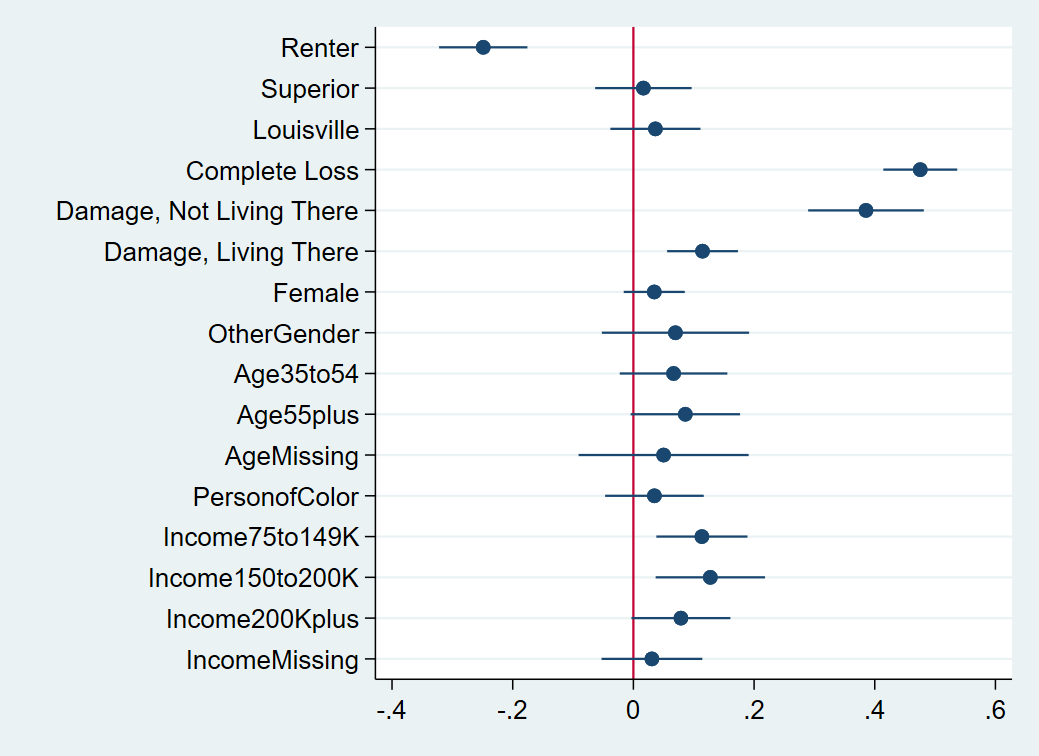

Controlling for other characteristics in a multivariate regression, we continued to find that renters were substantially less likely (about 20%) to report having attended a fire-related meeting remotely or in person in the three months before the survey (see Figure 8). Those who experienced a complete loss or had damage and were not living in their pre-fire homes were significantly more likely to participate, and income was also positively associated with participation.

Figure 8. Multivariate Regression Results for Those Attending a Fire-Related Meeting

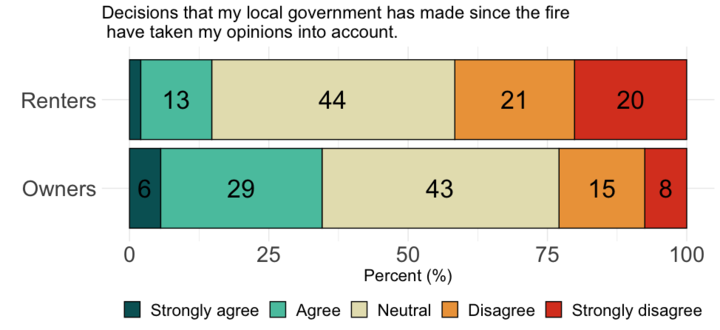

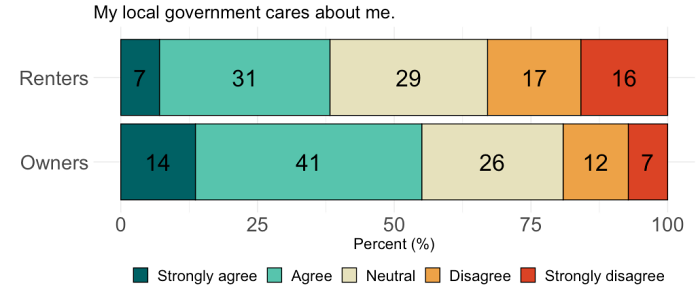

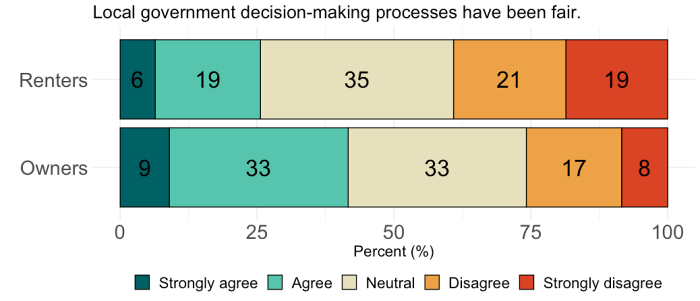

We also assessed respondent level of agreement or disagreement with several statements about local decision-making processes (see Figure 9). Compared to homeowners, renters were significantly less likely to agree that decisions by local governments since the fire have taken their opinions in to account, that their local government cares about them, and that local government decision-making processes have been fair.

Figure 9. Levels of Agreement with Opinions About Government and Decision-Making Processes by Housing Tenure

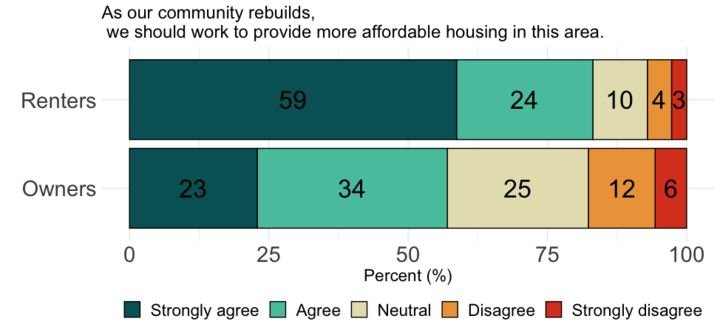

Finally, we assessed individuals’ levels of support for various policies in the recovery period. One of these questions asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “As our community rebuilds, we should work to provide more affordable housing in this area.” A majority of both homeowners and renters agreed with this statement; however, levels of agreement were substantially higher among renters (59% strongly agree, 24% agree) compared to homeowners (23% strongly agree, 34% agree) (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Levels of Agreement with Affordable Housing Statement by Housing Tenure

Open Ended Responses

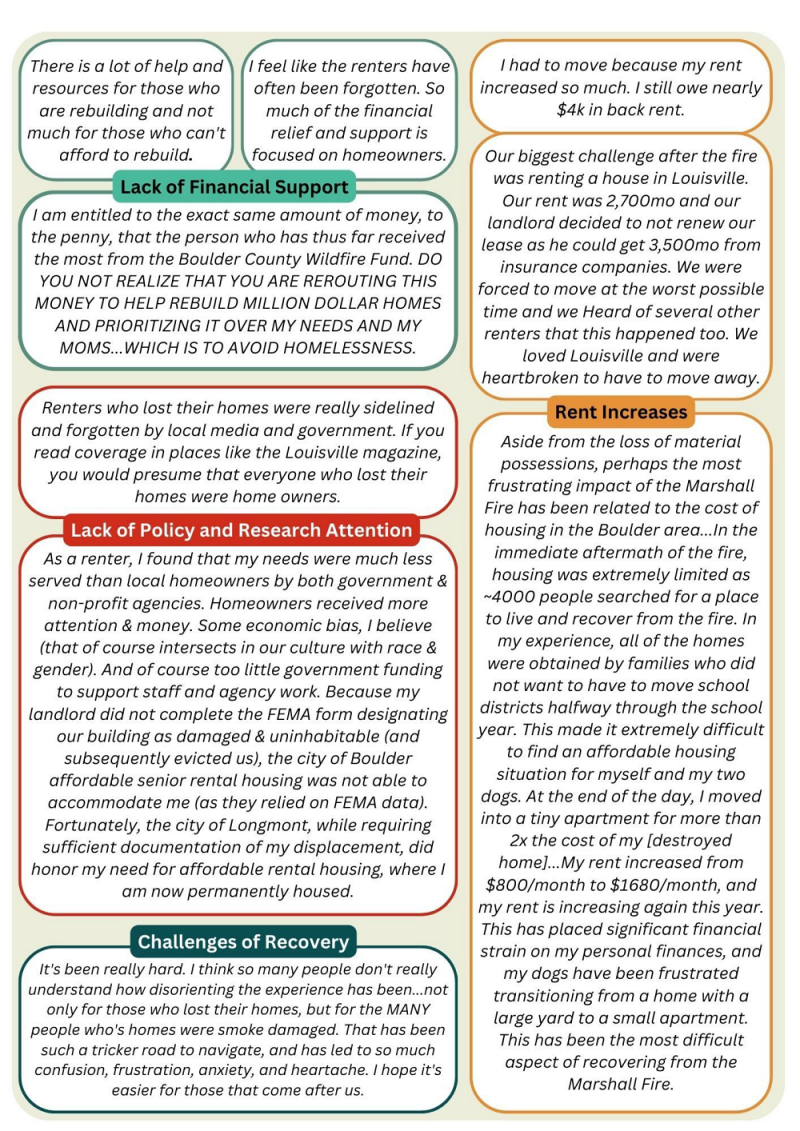

At the end of the survey, we included an open-ended question inviting respondents to share any additional information about their experiences around the Marshall Fire. A selection of responses from renters along with some emerging themes are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Quotes and Key Themes from Renter Responses to Open-Ended Survey Questions

Discussion

Results from our research fill an important gap in studies of housing tenure for renters, demonstrating that the experiences of renters and homeowners have differed in important ways following the Marshall Fire. Renters experienced higher levels of displacement, with nearly two-thirds moving from the property where they lived before the fire, and nearly a third of renters—all of whom were living in Boulder County at the time of the fire—moving out of the county.

In addition to direct displacement due to fire damage, our results show how increased housing costs after the fire contributed to a “second displacement” for many renters. Nearly two-thirds of renters still living in the same properties at the time of the Wave 2 survey reported an increase in rent, and about one-quarter of those not-displaced saw increases of more than 10%. Renters who did not experience a complete Ioss but had moved from their pre-fire properties rated housing costs as the most important factor driving their moving decisions. Open-ended responses also highlight the importance of housing costs and rent increases as a major challenge for renters after the fire. These results are consistent with a report released by the East County Housing Opportunity Coalition in late 2022 that documented challenges renters faced after the Marshall Fire, including widespread rent increases and price gouging (East County Housing Opportunity Coalition, 2022).

Our results also show that renters report, on average, engaging less with public officials and participating less in planning and policy-making processes, which could have important implications for long-term recovery. It is beyond the scope of this study to assess why renters report being less engaged than homeowners, but it is well-established that representation in planning, policy and decision-making processes is important for the groups who wish to see their needs addressed. Not surprisingly our survey results show that renters were less confident that their voices were being heard, that the recovery process was fair, or that their local government cared about them compared to homeowners.

Conclusions

Policy Implications

The challenges renters face in the process of recovering from the Marshall Fire highlight gaps in current policy that could provide more clarity and security for this group in the post-disaster context. In Spring 2023, the Colorado General Assembly passed legislation aimed at addressing some of these gaps. Perhaps most notably, HB23-1254 Habitability of Residential Premises includes provisions designed to codify landlords’ remediation responsibilities after environmental public health events, expand the definition of retaliation by a landlord, and provide more guidance around tenants’ rights to terminate a lease when a property has been damaged by a disaster (Habitability of Residential Premises, 202330). Ensuring that this law is implemented fully and adequately, with the engagement of communities that have experienced these disasters, will help to address some of the challenges highlighted in our findings. A broader bill aimed at repealing a statewide prohibition on local rent controls lost during the same legislative session (Repeal Prohibition Local Residential Rent Control, 202331). Given the reports in our data and elsewhere of large increases in rental prices after the Marshall Fire, this prohibition should be revisited or, as others have advocated, exceptions should be allowed in the aftermath of a disaster. A 2020 law intended to prevent price gouging after a disaster was referenced by statewide officials in an attempt to discourage large rent increases after the Marshall Fire, but the law does not specifically address housing costs and is aimed at other types of costs (e.g., building materials, emergency supplies, fuel) (Price Gouge Amid Disaster Deceptive Trade Practice, 202032).

We also found that renters are both less likely to participate in decision-making and are strongly in favor of equity-focused policies such as creating more affordable housing in the affected areas. Affordable housing proposals often face organized and vocal opposition, particularly in majority white, affluent communities like those affected by the Marshall Fire. Survey research like ours is important to gauge broader public opinions on these topics, rather than assuming that those who are engaging in decision-making processes are representative of the affected communities overall. Local decision-makers should be aware of who is not in the room and strive to create policies that serve the needs of the whole community, not just those who are able to participate and advocate for their needs.

Limitations

Like all modern survey research, our ability to make broad inferences from our sample is limited by the survey’s response rate. Overall, about 25-30% of those who were recruited to take our surveys responded, and it is quite possible that those who were particularly hard-hit by the disaster may have found it difficult to find the time and energy to participate. We are encouraged by the fact that, across our two samples, we collected data from about 461 complete loss households, out of a total of about 1084 lost homes according to official lists. In addition, the total number of displaced renters has been reported at around 340 (Golden, 202233); our sample includes 123 renters who were not living at their pre-Marshall homes, such that we may be capturing roughly 36% of this population. However, the lack of rental licensing and tracking makes these numbers hard to verify, and we cannot say with certainty that our results represent the overall experiences of renters or homeowners in the affected areas.

Future Research Directions

Household and community recovery after the Marshall Fire will take years, and it is vital that researchers continue to monitor the differential recovery pathways for different groups of survivors. We are actively seeking additional funding to conduct a third survey wave to continue tracking the recovery process as it unfolds over time. We plan to continue to focus on equity in the recovery process, including a continued focus on the experiences of renters and households with less income.

Acknowledgments. We acknowledge funding support from the Quick Response Research Award Program, which is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF Award #1635593). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or Natural Hazards Center. This project was also supported by funding from the National Science Foundation’s Decisions, Risk, and Management Sciences program (SES-2220589) and the JPB Environmental Health Fellows program. We also appreciate the collaboration of the Marshall Fire Unified Research Survey Working Group, and the assistance with data collection, cleaning, and analysis provided by Annie Rosenow of the Urban Institute and Rick DeVoss, Hannah Walters, and Molly Kadota of the Colorado School of Public Health.

References

-

Scott, M. (2022). Wet, then dry extremes contributed to devastating Marshall Fire in Colorado. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/wet-then-dry-extremes-contributed-devastating-marshall-fire-colorado#:~:text=Where%20the%20wildfire%20struck%E2%80%94in,December%2C%20drought%20conditions%20were%20extreme ↩

-

Brown, J. (2022). Colorado passed new laws intended to help tenants. But those affected by the Marshall fire say they're not working. The Colorado Sun. https://coloradosun.com/2022/06/27/marshall-fire-rental-housing/ ↩

-

East County Housing Opportunity Coalition. (2022). Lessons from the Marshall Fire - Our Law is Insufficient to Protect Renters. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e31dacdf21df7226cee7c3a/t/63865adda7af8f15242729ab/1669749469911/Marshall+fire+renters+report_final.pdf ↩

-

Wegmann, J., Schafran, A., & Pfeiffer, D. (2017). Breaking the double impasse: Securing and supporting diverse housing tenures in the United States. Housing Policy Debate, 27(2), 193-216. ↩

-

Lee, J. Y., & Van Zandt, S. (2019). Housing tenure and social vulnerability to disasters: A review of the evidence. Journal of Planning Literature, 34(2), 156-170. ↩

-

Bolin, R. (1993). Post-earthquake shelter and housing: Research findings and policy implications. In Monograph 5: Socioeconomic Impacts (pp. 107-131). ↩

-

Bolin, R., & Stanford, L. (1991). Shelter, housing and recovery: A comparison of US disasters. Disasters, 15(1), 24-34. ↩

-

Comerio, M. C. (2014). Disaster recovery and community renewal: Housing approaches. Cityscape, 16(2), 51-68. ↩

-

Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E. L., Dynes, R. R., Peacock, W. G., Dash, N., & Zhang, Y. (2007). Sheltering and housing recovery following disaster. Handbook of Disaster Research, 258-274. ↩

-

Emrich, C. T., Tate, E., Larson, S. E., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Measuring social equity in flood recovery funding. Environmental Hazards, 19(3), 228-250. ↩

-

Green, T. F., & Olshansky, R. B. (2012). Rebuilding housing in New Orleans: The road home program after the Hurricane Katrina disaster. Housing Policy Debate, 22(1), 75-99. ↩

-

Peacock, W. G., Zhang, Y., & Dash, N. (2006). Sheltering, temporary housing, and permanent housing recovery following a major natural disaster in the United States. International Workshop on Disaster Recovery and Rescue, Taiwan. ↩

-

Dundon, L. A., & Camp, J. S. (2021). Climate justice and home-buyout programs: renters as a forgotten population in managed retreat actions. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 11(3), 420-433. ↩

-

Olshansky, R. B., & Johnson, L. A. (2014). The evolution of the federal role in supporting community recovery after US disasters. Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(4), 293-304. ↩

-

Spader, J., & Turnham, J. (2014). CDBG disaster recovery assistance and homeowners' rebuilding outcomes following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Housing Policy Debate, 24(1), 213-237. ↩

-

Brennan, M., Srini, T., Steil, J., Mazereeuw, M., & Ovalles, L. (2022). A perfect storm? Disasters and evictions. Housing Policy Debate, 32(1), 52-83. ↩

-

Raymond, E., Green, T., & Kaminski, M. (2022). Preventing evictions after disasters: The role of landlord-tenant law. Housing Policy Debate, 32(1), 35-51. ↩

-

Fussell, E., & Harris, E. (2014). Homeownership and housing displacement after Hurricane Katrina among low‐income African‐American mothers in New Orleans. Social Science Quarterly, 95(4), 1086-1100. ↩

-

Kammerbauer, M., & Wamsler, C. (2017). Social inequality and marginalization in post-disaster recovery: Challenging the consensus? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 24, 411-418. ↩

-

Khajehei, S., & Hamideh, S. (2023). Post-Disaster Recovery Challenges of Public Housing Residents: Lumberton, North Carolina After Hurricane Matthew. Urban Affairs Review, 10780874231167570. ↩

-

Bryant, R. A., Gibbs, L., Gallagher, H. C., Pattison, P., Lusher, D., MacDougall, C., Harms, L., Block, K., Sinnott, V., Ireton, G., Richardson, J., & Forbes, D. (2018). Longitudinal study of changing psychological outcomes following the Victorian Black Saturday bushfires. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(6), 542-551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417714337 ↩

-

Macleod, E., Heffernan, T., Greenwood, L. M., Walker, I., Lane, J., Stanley, S. K., Evans, O., Calear, A. L., Cruwys, T., Christensen, B. K., Kurz, T., Lancsar, E., Reynolds, J., Rodney Harris, R., & Sutherland, S. (2023). Predictors of individual mental health and psychological resilience after Australia's 2019-2020 bushfires. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48674231175618. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674231175618 ↩

-

Silveira, S., Kornbluh, M., Withers, M. C., Grennan, G., Ramanathan, V., & Mishra, J. (2021). Chronic Mental Health Sequelae of Climate Change Extremes: A Case Study of the Deadliest Californian Wildfire. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041487 ↩

-

Xu, R., Yu, P., Abramson, M. J., Johnston, F. H., Samet, J. M., Bell, M. L., Haines, A., Ebi, K. L., Li, S., & Guo, Y. (2020). Wildfires, Global Climate Change, and Human Health. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(22), 2173-2181. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr2028985 ↩

-

Brown, M. R. G., Agyapong, V., Greenshaw, A. J., Cribben, I., Brett-MacLean, P., Drolet, J., McDonald-Harker, C., Omeje, J., Mankowsi, M., Noble, S., Kitching, D., & Silverstone, P. H. (2019). After the Fort McMurray wildfire there are significant increases in mental health symptoms in grade 7-12 students compared to controls. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-2007-1 ↩

-

Baryshnikova, N. V., & Pham, N. T. A. (2019). Natural disasters and mental health: A quantile approach. Economics Letters, 180, 62-66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2019.04.016 ↩

-

Fussell, E., & Lowe, S. R. (2014). The impact of housing displacement on the mental health of low-income parents after Hurricane Katrina. Social Science and Medicine, 113, 137-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.025 ↩

-

Einstein, K. L., Palmer, M., & Glick, D. M. (2018). Who participates in local government? Evidence from meeting minutes [10.1017/s153759271800213x]. Katherine Levine Einstein, Maxwell Palmer, David M Glick. https://doi.org/10.1017/s153759271800213x ↩

-

Hamideh, S., & Rongerude, J. (2018). Social vulnerability and participation in disaster recovery decisions: public housing in Galveston after Hurricane Ike. Natural Hazards, 93(3), 1629-1648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3371-3 ↩

-

Habitability of Residential Premises, HB23-1254, Colorado General Assembly (2023). https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb23-1254?utm_source=longmontleader&utm_campaign=longmontleader%3A%20outbound&utm_medium=referral ↩

-

Repeal Prohibition Local Residential Rent Control, HB23-1115, Colorado General Assembly (2023). https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb23-1115 ↩

-

Price Gouge Amid Disaster Deceptive Trade Practice, HB20-1414, Colorado General Assembly (2020). https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb20-1414 ↩

-

Golden, A. (2022, December 4). Report details struggles of renters following Marshall fire. Longmont Leader. https://www.longmontleader.com/local-news/report-details-struggles-of-renters-following-marshall-fire-6191687 ↩

Dickinson, K., Rumbach, A., Albright, E., & Crow, D. (2023). Sidelined: Renters’ Experiences After Colorado’s Marshall Fire. Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, 363. Boulder, CO: Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. Available at: https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/sidelined