Stakeholder Values in Hurricane Michael

Understanding How Value Dynamics Contribute to Collaborative Decision Making in Disasters

Publication Date: 2019

Abstract

The need to integrate multi-sector stakeholder values into emergency management is a hidden and overlooked issue in disaster literature. Stakeholder values are defined as things of importance, merit, and utility to stakeholders. Stakeholders (e.g., communities, governments, and the private sector and nonprofit sectors) have numerous values that they hold at varying degrees of importance; forming a system of value priorities. Stakeholder values and value priorities—referred to as value systems—are not static in the disaster context—they are dynamic, time-sensitive and event-driven. A more in-depth understanding of the dynamics of stakeholder value systems is crucial in helping policymakers introduce proactive and timely measures resulting in more resilient communities.

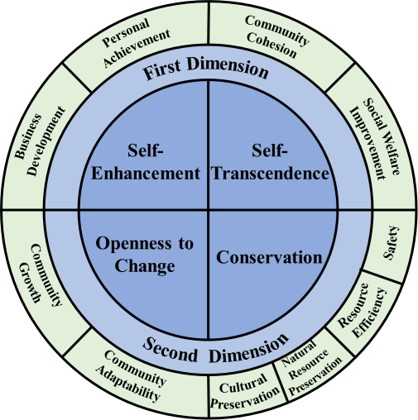

To address this gap, this report focuses on identifying and understanding stakeholder values in the context of Hurricane Michael. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to understand what public and private stakeholders valued in different phases of the hurricane. Based on the preliminary interview results, ten stakeholder values were identified and analyzed, including: safety, resource efficiency, natural resource preservation, culture preservation, community growth, community adaptability, community cohesion, social welfare improvement, personal achievement, and business development.

This study advances knowledge in the area of disasters by empirically investigating public and private stakeholder values across different phases. Such knowledge will help practitioners implement disaster-resilient strategies in ways that account for diverse stakeholder needs and priorities, thus facilitating human-centered decision-making aimed at building more resilient communities.

Introduction

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) sent the message “Don’t rely on us,” in its 2017 Hurricane Season After-Action Report (FEMA, 2017). FEMA noted, “The work of emergency management does not belong just to FEMA. It is the responsibility of the whole community, federal, [state and local governments], private sector partners, and private citizens to build collective capacity and prepare for the disasters we will inevitably face” (FEMA, 2018, p. 501). Despite the broader acknowledgment of shared responsibilities in emergency management, one of the overlooked issues in disaster literature is the integration of multi-sector stakeholder values. Stakeholders are defined as any individuals, groups, or organizations that are responsible for, impacted by, or interested in disaster management, such as different levels of government, the private sector, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and communities (Figure 1). Stakeholder values are things that are of importance, merit, and utility to stakeholders (Zhang & El-Gohary, 20162). Each stakeholder holds numerous values with varying degrees of importance, forming a system of value priorities. Stakeholder values and value priorities, referred to as value systems, are not static. They are dynamic, time-sensitive, and event-driven.

Research shows that major life events could impact individuals’ value systems (Bardi et al., 20143; Tormos et al., 20174). Disasters, as a devastating experience to most of the people impacted, could then potentially alter those people’s value systems. Their values could change at different phases of disasters, including disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Having a comprehensive and deep understanding of stakeholder value systems and how they change throughout different phases of disasters is crucial, as stakeholder value systems motivate and orient decision-making processes (Cheng & Fleischmann, 20105). A more in-depth understanding of stakeholder value systems allows decision-makers to implement different strategies and practices in a way that addresses stakeholder-prioritized concerns and needs.

Despite the importance, there is a lack of empirical studies that explicitly and systematically investigate stakeholder values in disaster contexts. Our literature review also did not reveal much research that examines how stakeholder value systems change in the aftermath of disasters or with elapsed time after disasters. Researchers have emphasized the importance of engaging stakeholders in decision-making on disaster management and have proposed strategies for such engagement (e.g., Ganapati & Mukherji, 20146; Ganapati & Ganapati, 20097; Kapucu & Garayev, 20118; Kapucu & Van Mart, 20069). While the underlying goal of stakeholder engagement is to account for their diverse values in decision-making, these efforts have neither explicitly nor systematically captured stakeholder value systems. In addition, during disastrous events, stakeholders may have an entirely different set of value priorities, compared with their value priorities in non-disaster time. Existing research has mainly focused on examining socioeconomic or demographic variables (e.g., gender, poverty, unemployment) as antecedents of individuals’ value priorities (Hitlin & Piliavin, 200410; Schwartz, 200411). However, contextual variables (e.g., the disaster context) may be just as important as understanding the value priorities and their potential changes over time.

To address the above-mentioned gaps, this study aims to understand multi-sector stakeholder values in the context of Hurricane Michael. It also examines how these values change during different disaster phases. We conducted an empirical study by interviewing public and private stakeholders in communities that were heavily impacted by Hurricane Michael. The remainder of the report describes our research context and the research questions that we aim to address, explains the research methodology, and presents our preliminary results and analysis.

Human Values and Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values

According to Schwartz’s theory of basic human values (Schwartz, 201212), values are the things that are of importance to the stakeholders. Each of the stakeholders holds numerous values (e.g., achievement, security, benevolence) with varying degrees of importance. A specific value may be important to one stakeholder but unimportant to another. Schwartz (2012) identified three main features of values (Schwartz, 2012):

- Desirable goals—Values refer to desirable goals that motivate actions and decision-making processes. For example, a community resident who values his/her property’s safety would install hurricane shutters during the disaster preparedness phase.

- Importance—Multiple values are ordered by importance relative to one another to form a system of value priorities. Different people have different systems of value priorities. For example, in the context of disaster, a business owner may value safety over business development.

- Multiple values guide action—The tradeoff among relevant but competing values guides actions and decision-making processes. For example, a community resident may value both property safety and renovation cost savings, and so will need to make a tradeoff when deciding whether to install expensive high-impact windows.

Table 1. Schwartz’s Ten Basic Human Values.

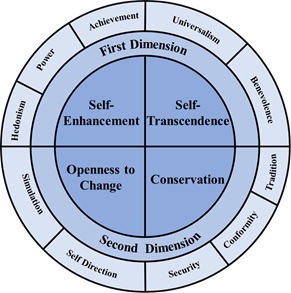

Schwartz (2012) proposes 10 basic human values, including self-direction, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, security, conformity, tradition, benevolence, and universalism. Table 1 summarizes the definitions and examples of these values. These 10 values are universal because they are grounded in three universal requirements of human existence, including needs of individuals as biological organisms, requisites of coordinated social interaction, and survival and welfare needs of groups. They are further grouped into two bipolar dimensions with four main categories: self-transcendence, self-enhancement, conservation, and openness to change (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schwartz’s value framework.

The first dimension contrasts “self-enhancement” and “self-transcendence” values; it captures the conflicts or synergies between values that emphasize pursuit of one’s own interests and relative success and dominance over others (power, achievement) and concerns for the welfare and interests of others (universalism, benevolence). The second dimension contrasts “openness to change” and “conservation” values. This dimension captures the conflicts or synergies between values that emphasize the independence of thoughts, actions, and feelings, as well as readiness and willingness for change (self-direction, stimulation) and values that emphasize protection and preservation of past and current conditions (security, conformity, tradition).

Research Context

Hurricane Michael, a Category 5 storm with maximum sustained wind speeds of 161 mph, made landfall in Florida’s Northwest Panhandle region on October 10, 2018. It was the strongest storm to hit the United States in more than 25 years, and the most powerful on record in the Florida Panhandle (Reeves & Lush, 201813). The storm’s rapid intensification was particularly noteworthy from both meteorological and disaster management perspectives. Many residents decided to shelter in place, assuming the storm would remain a Category 3; thus, they did not have time to safely evacuate when it became clear that the storm had rapidly intensified. Along with tragic losses of lives, the catastrophic wind damage and devastating flooding caused around $53 billion in economic losses (Perryman, 201814). Thousands of people living in the hurricane’s path were relocated after the hurricane. Cities and towns such as Mexico Beach, Panama City, Panama City Beach, and Marianna were still experiencing devastation when this study was conducted. In addition to the life-threatening storm surge, structural damage was extensive. Preliminary data assessments indicate that almost 50,000 structures were affected, and more than 3,000 structures were destroyed (National Weather Service, 201815). The image below shows the housing destruction caused by Hurricane Michael in Panama City.

The wind damage was not confined to the coastline and extended well inland. For example, in Marianna, many businesses lost their roofs and exterior walls. In addition to extensive structural damage, hurricane-force winds caused widespread power outages. Nearly 100% of customers across a large portion of the Florida Panhandle lost power, with some of those outages lasting weeks. The catastrophic winds also resulted in damage to timber and agricultural communities across Florida. According to the Florida Forest Service, the timber damage estimates amounted to more than $1.2 billion, with almost 3 million acres of forested land damaged (National Weather Service, 2018).

Research Objectives

Our study aims to understand and analyze the dynamics of multi-sector stakeholder value systems during the preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation phases of Hurricane Michael. In this preliminary work, we aim to address the following research questions:

- What do public and private stakeholders value in the context of Hurricane Michael?

- How do their values change throughout different phases of Hurricane Michael (i.e., preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation phases)?

Research Methodology

To answer these questions, we conducted a qualitative study primarily based on in-depth semi-structured interviews. The face-to-face interviews were conducted during our three visits to the Florida Panhandle in December 2018, January 2019, and February 2019. We conducted a total of 24 interviews with 30 interviewees. Our interviewees included stakeholders from public sector agencies, such as the Florida Division of Emergency Management, and the city governments of Panama City, Panama City Beach, and Mexico Beach, and private sector entities, such as construction firms, tourist-centered businesses, healthcare facilities, and financial institutions. We identified our initial set of interviewees through a review of secondary sources (e.g., websites of government agencies, local news websites, and articles). These interviewees were either individuals who have had disaster management responsibilities or liabilities (e.g., emergency managers, housing contractors) or were directly or indirectly affected by Hurricane Michael (e.g., local business owners). We then used a snowball sampling technique to expand the initial list of interviewees. Snowball sampling is a nonprobability sampling technique where exiting interviewees recruit future interviewees from among their acquaintances (Goodman, 196116).

Our interviews followed a semi-structured format. In the interview instrument, we grouped the questions into five major sections based on the disaster management cycle:

- Before Hurricane Michael (“normal” condition)

- Preparedness

- Response

- Recovery

- Community Future (mitigation)

Under each of these sections, we asked a similar set of open-ended questions. Some examples of the questions include:

- What did you/your group/your organization value about this community the most at that time?

- Can you please tell me why this mattered to you/your group/your organization the most at that time?

- Given that this is what you valued at the time, please tell me one thing you should have done but did not do right at that time.

- Please explain why you think doing this would have helped the community at that time.

The semi-structured format of the interview allowed us to modify the questions on the spot as per the profession and/or background of the interviewees, thereby allowing for more comprehensive data collection. For example, during the interviews with the government officials, we added questions about the scope of their work during the disaster, their expectations from residents, and what they value about the civil infrastructure.

We conducted and recorded 21 interviews with permissions from the interviewees and obtained a consent letter in each case. During the three interviews where recording was not permitted by the interviewees, we took detailed notes. All the interviews took place during the daytime, per the availability of the stakeholders. We recorded the interviews and transcribed them using commercial transcription software, including NVivo Transcription and Sonix. We cross-verified and edited them personally.

Preliminary Results

Our preliminary results analysis mainly focuses on identifying the main stakeholder values in the context of Hurricane Michael, analyzing the values between public and private stakeholders across different phases of disasters (i.e., before and after a disaster and for disaster preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation). Detailed descriptions and discussions on the collected responses and the analysis of the responses are presented below.

Classification of Responses

We broadly classified the interview responses from the interviews into either public or private sector based on the interviewees’ professions. Among the 30 responses, 12 were from public sector stakeholders (e.g., city commissioner, city manager, chairman of county, city planner) and 18 responses were from private sector stakeholders (e.g., construction project manager, hotel owner, civil engineer, doctor, bank officer, insurance agent, school principal). The descriptive statistics of the responses are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Participant demographic information.

| Private sector stakeholders | Public sector stakeholder | All stakeholders | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder group | |||

| Number of stakeholders | 18 | 12 | 30 |

| Region | |||

| Panama City | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| Panama City Beach | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Port St. Joe | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Bay County | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 16 | 10 | 26 |

| Female | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Age | |||

| 18-25 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 26-30 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 31-35 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| 36-40 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 41-45 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 46-50 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 51-55 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 56-60 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 61-65 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Education | |||

| High school graduate | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bachelor's degree | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| Graduate degree | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Associate’s Degree | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Professional degree | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Other (Credit, No college) | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Years with Current Organization | |||

| Less than 1 year | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| More than 1 but less than 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| More than 3 but less than 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| More than 6 but less than 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| More than 9 but less than 12 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 12 years or more | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| White | 9 | 9 | 18 |

| Black or African American | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| American Indian or Alaska | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Stakeholder Value Identification and Analysis

By analyzing our preliminary results of the interviews, we identified 10 stakeholder values in the context of Hurricane Michael, including safety, resource efficiency, natural resource preservation, culture preservation, community growth, community adaptability, community cohesion, social welfare improvement, personal achievement, and business development. We then classified these identified values into Schwartz’s value framework (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Identified stakeholder values in the context of Hurricane Michael.

Conservation

In the context of Hurricane Michael, the conservation value includes safety, resource efficiency, natural resource preservation, and cultural preservation.

Safety

Safety refers to the condition of being protected from disasters. It was the most prioritized value throughout different phases of Hurricane Michael by both public and private stakeholders. Safety has multiple levels and dimensions, including personal life safety, family safety, employee safety, home safety, business property safety, and public safety.

The interviewees from the private sector focused more on personal life safety, family safety, employee safety, and personal property safety. For example, as mentioned by one of the interviewees from the tourism sector, Hurricane Michael was initially predicted to be a Category 2 hurricane; the local residents’ initial value priority was the potential economic effects of Hurricane Michael because 30 percent of their jobs are tied to tourism. However, as the hurricane approached, “our main value [had] nothing to do with tourism business,” one interviewee said, adding, “our main value [was] the safety of our family and friends.” The first action taken by all community stakeholders was to ensure the safety of themselves, their family and friends, and their properties. For example, during the preparedness phase, community stakeholders took precautionary measures to ensure the safety of their properties by installing shutters, adding additional straps and clips to secure roofs, trimming trees and shrubs to restrict wind damage, and storing sandbags to prevent flood damage. They stored food, water, and emergency supplies to protect their personal life and family safety. In addition, some business owners mentioned that employee safety stayed at the top of their value list. They strove to provide all necessary resources and facilities to their employees who were vulnerable and in need of help before and after Hurricane Michael.

Public stakeholders attached high importance to the safety of the whole community, in addition to personal life safety and property safety. They took different actions to ensure the safety of the entire community. For example, one interviewee from the Florida Division of Emergency Management noted that the main goal of emergency management is to “ensure the safety of the whole community.” To do that, he emphasized that all sectors need to work collaboratively to ensure that communities are aware of emergency knowledge and resources available to them throughout different phases of disasters. In addition, he highlighted the importance of mitigation efforts. For example, more stakeholders and sectors need to be engaged in statewide emergency training and exercises. “We should not wait until the disaster hits us; we need to take better mitigation actions and be better prepared,” he said. Another interviewee from the public sector mentioned that a public safety risk management framework or flow chart could/should be designed to include multiple sectors, with clear definitions on the roles and responsibilities necessary to collaboratively reduce disaster risks to affected communities.

Resource Efficiency

Resource efficiency refers to using or consuming resources (e.g., water, energy, gas, materials, staffing) more efficiently throughout different phases of disasters. It includes reducing the waste or consumption of resources, reusing or recycling resources, and/or using resources with recycled content. Disaster management involves a coordinated and cooperative process of preparing to match the urgent needs of the public with limited resources. One critical goal of emergency management is to ensure the efficient use of life-saving and recovery resources, including water, power, gas, food, materials, and staffing.

In the interviews, both public and private stakeholders emphasized the importance of efficient use of resources, especially during the response and recovery phases. For example, according to an interviewee from Florida Department of Transportation, one of the most challenging tasks during the disaster response phase was the coordination of limited resources to effectively remove the debris and open the roads. “After Hurricane Michael, all roads are impacted, all roads need to be reopened, but we only have limited resources,” the interviewee said. “How to make a better use of these limited resources becomes a challenge.” Similarly, limited access to water, food, power, gas, and medical supplies was mentioned by several interviewees from the private sector. “To ensure the patients get the medicine they need after the disaster, I prepared all the prescriptions before Michael hit us because I knew there would be limited medical supplies once Michael passes,” said one interviewee who works in a private clinic. The local infrastructure conditions further worsened the limited resource supplies, as many local roads were completely inaccessible due to debris and fallen trees and branches. In some regions, water and power outages lasted for several weeks after the disaster because of the severely damaged infrastructure. In such a situation, efficiently using and allocating limited resources became a high value priority to the stakeholders.

Another major challenge for resource efficiency during the recovery phase is a shortage of construction material and related labor, which affects efforts to rebuild. According to a survey conducted by the Associated General Contractors of America (AGCA), 80 percent of the construction firms are unable to find the labor they require (AGCA, 201817). As a result, homes that previously took three to four months to rebuild can now take six to eight months to complete. “We need to reach out to high school kids to spread the information and provide training,” one interviewee from the Florida Home Builders Association said. “We need to build the positive image of the construction industry and bring more labor.”

Natural Resource Preservation

Natural resource preservation refers to the protection, preservation, restoration, and/or enhancement of ecosystems (e.g., wetlands, coral reefs, forests), biological resources (e.g., wildlife), geology, and hydrology. Natural resources and environmental concerns have been prevalent throughout different phases of disasters. Natural resource preservation plays a critical role in a community’s ability to prevent, cope with, and recover from disasters; it can help mitigate further damage, encourage economic health, influence property value, and spur revenue from recreational and tourism activities. At the global level, there is growing consensus around linking disaster risk reduction with natural resource protection. The Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) calls for efforts to “encourage the sustainable use and management of ecosystems, including through better land use planning and development activities to reduce risk and vulnerabilities” (UNEP, 2019, p.318). It facilitates the implementation of integrated environmental and natural resource management approaches that incorporate disaster risk reduction, such as integrated flood management and appropriate management of fragile ecosystems (UNEP, 2019).

In the interviews, the importance of natural resource preservation was mostly highlighted by the public stakeholders. “While large-scale disasters like Hurricane Michael cannot be entirely avoided, there are ways we can mitigate the devastating impact of disasters through better ecosystem management,” said one of the interviewees from the public sector. Strategically planning for green space and vegetated land and restoring large swaths of natural resources (e.g., wetlands) can reduce the effects of disasters. Vegetated land absorbs and retains water, slowing its movement, thus reducing flooding and its subsequent effects. Planning that incorporates these features not only helps reduce flooding, but also helps mitigate broader storm impacts. Similarly, in coastal regions, coral reef systems act as physical barriers that reduce wind and wave energy, thus reducing the impact of hurricanes. In Mexico Beach, the Mexico Beach Artificial Reef Association initiated one of the most active artificial reef programs in Florida. Since 1997, the organization has built over 300 patch reefs off the sandy shores of Bay and Gulf counties (Cox, 201919). Without the protection provided by natural resources and ecosystems, the detrimental effects of disasters could become more catastrophic.

Cultural Preservation

Cultural preservation is the value associated with preserving and/or protecting local culture and history. Preserving historic buildings and sites is vital to understanding a community’s heritage. To build more resilient communities, historic and cultural resources should be preserved in immediate disaster response, long-term community recovery, and future mitigation efforts (NIST, 201720). As highlighted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), “the symbolism inherent in heritage is a powerful means to help victims recover from the psychological impact of disasters. In such situations, people search desperately for identity and self-esteem” (UNESCO, 201521, p.324), and their heritage and historic places can help people find purpose and solidarity. Heritage plays an important role in facilitating social cohesion, sustainable development, and psychological well-being of communities. Thus, protecting heritage is an essential way to promote community resilience (UNESCO, 2015). Hurricane Michael seriously damaged and completely destroyed many historical structures in Panama City and Mexico Beach. For example, the Old Callaway School, constructed in 1911, was damaged by the hurricane; the roof partially collapsed, the windows were broken, and the front entrance was heavily damaged. The Sapp House, a nine-room, two-story building built in 1916, suffered broken glass and damage to its roof, windows, and walls during Hurricane Michael (Breaux, 201922). One city commissioner of an impacted community said, “We need to preserve and maintain the historic sites of the towns and preserve the landscape of the cities.” During the recovery phase, following guidance for protecting heritage and the treatment of historic areas and individual historical buildings, the commissioner worked with landscape planners and architects to restore the historic districts of the city’s urban areas. “It is a challenging process,” he said. “We need to balance the life safety, economic value, and preservation values in long-term recovery and planning.” The key is to retain historic features while sensitively incorporating new features that reduce the risk of future damage from disasters.

Openness to Change

In the context of Hurricane Michael, “openness to change” includes community growth and community adaptability.

Community Growth

Community growth refers to growth and changes brought about by disasters. Both public and private stakeholders expressed a positive and optimistic attitude toward Hurricane Michael’s impacts. Although their homes, businesses, and infrastructure systems were severely damaged, they emphasized that the disaster “opens doors for growth and change.” When talking about the future of their communities, they are determined to rebuild stronger structures instead of restoring the previous conditions. For example, one of the interviewees from the public sector emphasized that the building codes should and will be upgraded given the impact of Hurricane Michael. “There is no doubt that [the standard in the building code] should be raised,” he said. Most new homes and commercial buildings in Miami-Dade County must be built to withstand wind speeds of approximately 175 mph, but these specifications are only 120 mph in the Mexico Beach area. To build more resilient communities in the Florida Panhandle area, there is growing consensus that building codes along the Florida Panhandle area should be stricter.

Similarly, a number of interviewees from the private sector who have lived in the Florida Panhandle for their entire lives are optimistic about the future of their communities; they embrace changes and are looking forward to more resilient communities. “Panama City has not changed for decades; now, it is the time for a more resilient community,” said a business owner who has lived in Panama City for more than 30 years. “Panama City Beach is a small town that was developing slowly at its pace. After the hurricane, there will be more motivations among people to rebuild and grow.” Another interviewee from Panama City Beach stated, “The city is generally very resilient, and it will always come back strong. Now the goal is to grow back and grow stronger.” Similarly, an interviewee from Mexico Beach mentioned that “it’s going to be a better future as the development in Florida Panhandle has always been laid-back, but this time it’s an opportunity to rebuild and grow with new codes and regulations.”

Community Adaptability

Community adaptability refers to the ability of community members to adjust their responses to the changing environment and/or conditions caused by the disasters. It is a critical element of community resilience, as “community resilience is composed of a set of networked adaptive capacities” (Plough et al., 2013, p.119123). The adaptability of the communities in the Florida Panhandle was tested and challenged by the rapid intensification of Hurricane Michael from a tropical storm into a Category 5 hurricane in three days, leaving little time for preparedness. Many residents decided to shelter in place, as they did not have time to safely evacuate. One of the interviewees mentioned that news of the hurricane was not taken seriously until the storm had actually started. As a result, residents were not prepared for the magnitude of the disaster, and they did not have enough resources to withstand the resulting damage.

Meteorologists have provided a number of explanations for the rapid intensification of Hurricane Michael, including climate change. Such climate-added rapid intensification will make hurricanes increasingly difficult to predict in the future (Chow, 201824). Given this, the interviewees from the Florida Division of Emergency Management emphasized that “to build the capacity of community adaptability, we should not just focus on the disaster response phase. Rather, we need to spend more efforts on disaster mitigation.” They highlighted that “public education and outreach are the key; training and exercises are the key.” Such education, training, and exercises should engage all sectors, including different levels of government, private sectors, NGOs, and community residents. To build more resilient communities, different stakeholders should not only collaboratively adjust to short-term extreme events, such as Hurricane Michael, but also adjust to the gradually changing climatic conditions to prepare for and deal with the long-term effects of climate change, especially coastal flooding, erosion, and ecosystem changes.

Self-transcendence

In the context of Hurricane Michael, self-transcendence includes community cohesion and social welfare improvement.

Community Cohesion

Community cohesion refers to the aspect of togetherness and bonding exhibited by members of a community. It includes features such as a sense of common belonging, trust in neighbors, and/or help and support from neighbors. The interviewees highlighted the importance of community cohesion and trust in neighbors during the disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. This result corresponds with a number of research studies (e.g., Tompson et al., 201325; Townshend et al., 201526; LaLone, 201227; Chang, 201028) that confirm social cohesion as a critical component in building more resilient communities. For example, Tompson et al. (2013) proved that communities with a strong sense of social connection recovered at a faster pace. People living in communities with the fastest recovery were more inclined to say that “others can be trusted” and “the disaster brought out the best in [their] neighbors.” In communities that had a harder time bouncing back, more people reported seeing looting, vandalism, and hoarding of food and water (Tompson et al., 2013).

During Hurricane Michael, both public and private stakeholders emphasized the importance of community cohesion and took actions to help or support one another. Hurricane Michael catastrophically impacted every individual, household, and community in the area. Many residents’ houses were damaged or destroyed, and they suffered from water, power, and phone service outages. The critical infrastructure systems (e.g., transportation, electricity, water, sewer) in the affected communities experienced severe damage. In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Michael, although federal and state governments quickly announced that emergency aid had been made available to the affected communities, some of the hardest-hit areas were nearly impossible to reach because the roads were flooded or buried with debris. As a result, community residents volunteered to ensure the safety of their neighbors after the disaster; shared resources such as water, food, gas, and generators; and helped each other conduct initial damage assessments and recovery efforts.

Community cohesion and community relationships significantly increased as a result of the impacts from Hurricane Michael. For example, in Mexico Beach, local residents who did not have enough basic resources (e.g., water, food) sought help from their neighbors instead of waiting for the government to distribute emergency supplies. In Tallahassee, some Publix grocery stores were open the day after the hurricane, and some store employees began work at 3 a.m. to ensure that ice and other supplies were available for customers. One physician in Panama City who lost her home said that she tried to help her patients “at any cost.” She had filled all their prescriptions before the hurricane because she expected that people would need their medicines during and immediately after the disaster. She reopened her clinic the day after the disaster to serve the patients when the two large hospitals in Panama City were severely damaged and other small clinics were closed. Public sector agencies also took all necessary actions to reach out to and improve the conditions of the impacted communities, and they worked extra hours for the betterment of communities. For example, an interviewee from the city government of Port St. Joe mentioned that his priority immediately after the disaster was not to repair his own damaged house, but “to make sure all citizens were accessible to the drinking water and medical facilities.” During the recovery phase, the state government provided multiple community assistance programs, which increased the “sense of belonging” of the impacted communities. For example, the VISIT FLORIDA Hurricane Michael assistance program was initiated in December 2018 to aid local tourism businesses in the counties affected by Hurricane Michael. The program is designed to assist with marketing the destinations to possible tourists once hurricane-damaged areas reopen. It provides critical relief and support and increases the cohesion of the impacted communities.

Social Welfare Improvement

Social welfare improvement refers to providing public or private social services for assisting disadvantaged groups. The regions struck by Hurricane Michael—both the coastal counties under an evacuation order and inland counties people fled to—are among the most socially vulnerable regions in the United States (DirectRelief, 201829). Hurricane Michael and similar disasters have had a disproportionate impact on disadvantaged and vulnerable groups (e.g., economically disadvantaged, elderly, and homeless populations). The economically disadvantaged are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters, as they have limited access to risk management instruments. Studies have indicated that poor households are less able to cope with disasters than rich households (Vakis et al., 200430; Vakis, 200631). Similarly, elderly and disabled people and those who have mobility impairments, require special medical assistance, lack transportation, or do not understand English are the most vulnerable to disasters, and they may require additional help and resources to recover. In addition, many coastal communities with limited infrastructure and little coastal protection were particularly vulnerable during Hurricane Michael (Millis, 201832). According to one interviewee from the public sector, some areas in the Florida Panhandle, such as Destin and Panama City, have dense development behind the beachfront homes, condos, and hotels, and there are bays and inlets that can easily spill water into the nearby neighborhoods. Most sections of the major highway—U.S. 98—in the affected communities are only 100 feet away from the coast. If storm surge damaged one section of the highway, it would be extremely challenging for emergency responders to reach residents in need. Those coastal communities encouraged residents to take shelter in central schools. One of the school principals who was interviewed mentioned that his school property was used to shelter homeless people during Hurricane Michael. He also emphasized that there is a need to build more shelters for people who are vulnerable in disasters. He emphasized that incentives and funding provided by the government would facilitate such practices and that there should be more collaboration between the public and private sectors.

Self-enhancement

In the context of Hurricane Michael, self-enhancement is mostly relevant to stakeholder values before the disaster; it includes personal achievement and business development.

Personal Achievement

Personal achievement refers to personal success through demonstration of competencies according to social standards. Many interviewees mentioned personal achievement as an important value before Hurricane Michael. Different stakeholders have different definitions and understandings of personal achievement. For example, a government official may define personal achievement as being reelected, while a business owner may define it as increasing the value of the business. A hotel owner may define it as attracting more hotel guests or opening more hotels, and a doctor may define it as saving more lives. In a disaster setting, different stakeholders have different opinions about the importance of personal achievement. On one hand, several interviewees explained that the priorities of safety, resource efficiency, and community growth and cohesion transcended their personal achievements. For example, one interviewee said his initial value priority was his tourism business and how the hurricane would have affected his business. However, immediately after the hurricane, he said, “Our main value has nothing to do with the tourism business. Our main value is the safety of our family and friends.” Conversely, some interviewees valued personal achievement as consistently important throughout different phases of the disaster. For example, the doctor who defined her personal achievement as saving more lives highlighted that her value of personal achievement was still on top of her value list in the context of Hurricane Michael. She reopened her clinic immediately after the disaster to “save more lives.” Similarly, a city manager who defined his personal achievement as “improving the welfare of the citizen” indicated that this value “did not change after the disaster.” He continued to strive to provide resources and supplies to the citizens he serves.

Business Development

Business development refers to building new opportunities in business and growth in the future. It is a long-term value for many small businesses in the Florida Panhandle. As a result of Hurricane Michael, many local businesses suffered from severe property damage, as well as water, power, and phone services outages. One interviewee said, “We were fortunate enough to have generators, and so we were able to get power going right away. However, Internet signal and cellular phone signals were not available. It took a month to get back to a normal situation after the disaster.” Although many small businesses had purchased insurance to cover direct damage (e.g., to structures and inventory), they did not specifically have small business interruption insurance that could have partially covered indirect damages such as loss of customers and revenues caused by prolonged closing. “Some businesses may never return,” said one interviewee who owns a hotel. The hotel owner is one of the lucky few whose property was relatively free from damage. However, he understood that the occupancy rate might take a long time to return to what was normal before the disaster. In addition, some small business owners evacuated after Hurricane Michael and decided not to return. One interviewee said, “The recovery process will take years, so they would rather restart the business in a new place.”

The interviewees also expressed concerns about the employment rate. Hundreds of people could be out of work because of the impact of Hurricane Michael on the local businesses. Thirty percent of the jobs in the Panama City area are linked with the service and tourism industry, which has been severely impacted by the hurricane. Conversely, the impacts of Hurricane Michael were a boon to the construction industry. Many companies reported labor and resource shortages due to the overwhelming number of reconstruction projects. Several interviewees from the construction industry said that although their houses were damaged, they felt blessed that they did not lose their jobs.

Suggested Actions for Enhancing the Disaster Resilience of Communities

Based on the interview findings, possible actions to enhance disaster resilience of the communities in the Florida Panhandle were identified.

Enhance Collaboration Between Public and Private Stakeholders

Disaster management is a shared responsibility among all stakeholders. Thus, to build disaster-resilient communities, it is important to integrate the values of both public and private stakeholders. More systematic and formal collaborations between public and private stakeholders should be established in community disaster planning and management. Although private stakeholders are not typically involved in disaster management processes, they are largely affected by disasters, and they also possess additional resources that can be used to support disaster management. Therefore, their values in the context of disasters, though sometimes different than the values of public stakeholders, should be taken into consideration when disaster management decisions are being made.

Prioritize the Implementation of Disaster Management Practices Based on Stakeholder Values

Our interviews indicate that stakeholders consistently attach higher importance to certain values (e.g., life safety, property safety) during disasters. Many local communities are not investing enough resources for disaster resilience practices, and many decision-makers are not yet prioritizing the enhancement of disaster resilience. Given limited resources, future efforts should focus on improving disaster resilience based on stakeholder value priorities and, resilience planning should be aligned with stakeholder value priorities in order to maximize stakeholder benefits to provide higher benefits to the community stakeholders. These value-driven practices can be integrated into community development plans in order to prioritize the implementation of disaster resilience strategies within a community’s budget.

Learn from Disasters

Communities affected by Hurricane Michael serve as a test bed for the implementation of resilience and disaster management strategies and reveal major resilience challenges and problems. Thus, it is important to take advantage of these unexpected or emergent opportunities to evaluate and further improve current disaster management practices in local communities. From these opportunities, lessons learned can be systematically captured and used to inform how to better prepare for and respond to future disasters. Storing, transferring, and exchanging knowledge and experience are essential elements of disaster prevention and mitigation.

Conclusion

This report presents our preliminary results for identifying stakeholder values in the context of Hurricane Michael. We conducted 24 interviews with 30 interviewees from both the public and private sectors of the impacted communities. Based on the interview findings, we have identified 10 major values, including safety, resource efficiency, natural resource preservation, culture preservation, community growth, community adaptability, community cohesion, social welfare improvement, personal achievement, and business development. Based on Schwartz’s (2012) theory of basic human values, we classified these values into conservation, openness to change, self-transcendence, and self-enhancement.

This study contributes to disaster literature by offering a more explicit understanding of stakeholder values in a disaster setting. It advances empirical knowledge of disaster resilience by empirically investigating public and private stakeholder values across different phases of the disaster. Such knowledge will help practitioners implement disaster resilience strategies in a way that accounts for stakeholder needs and priorities, thus facilitating human-centered decision-making that fosters more resilient communities.

This report summarizes the preliminary results from our study. We acknowledge that the limited number of responses in each stakeholder group (e.g., emergency manager, city manager, business owner, housing contractor, banker) restricts more detailed analysis and comparison across stakeholder groups; larger sample sizes in each group would yield more data from which to work. Thus, we will continue our data collection with a wider range of interviewees in the future. We will also conduct stakeholder surveys to further analyze the priority levels of the identified values to different stakeholders, as well as whether stakeholder value priorities change across different phases of disasters.

References

-

FEMA. (2018). 2017 Hurricane Season FEMA After-Action Report. Accessed July 9, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=812985. ↩

-

Zhang, L., & El-Gohary, N. M. (2016). Discovering stakeholder values for axiology-based value analysis of building projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 142(4), 4015095-1-4015095-15. ↩

-

Bardi, A., Buchanan, K.E., Goodwin, R., Slabu, L., & Robinson, M. (2014). Value stability and change during self-chosen life transitions: self-selection versus socialization effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 131-147. ↩

-

Tormos, R., Vauclair, C. M., & Dobewall, H. (2017). Does contextual change affect basic human values? A dynamic comparative multilevel analysis across 32 European countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(4), 490–510. ↩

-

Cheng, A., & Fleischmann, K. (2010). Developing a meta-inventory of human values. Proc. American Society for Information Science and Technology (ASIST 2010), 47(3), Pittsburgh, PA, USA. ↩

-

Ganapati, N. E., & Mukherji, A. (2014). Out of sync: World Bank funding for housing recovery, post-disaster planning and participation. Natural Hazards Review, 15(1), 58-73. ↩

-

Ganapati, N. E., & Ganapati, S. (2009). Enabling participatory planning in post-disaster contexts: a case study of World Bank’s housing reconstruction in Turkey. Journal of the American Planning Association, 75(1), 41-59. ↩

-

Kapucu, N., & Garayev, V. (2011). Collaborative decision-making in emergency and disaster management. International Journal of Public Administration, 34(6), 366–375. ↩

-

Kapucu, N., & Van Wart, M. (2006). The emerging role of the public sector in managing extreme events: lessons learned. Administration and Society, 38(3), 279–308. ↩

-

Hitlin, S., & Piliavin, J. (2004). Values: reviving a dormant concept. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 359-393. ↩

-

Schwartz, S. (2004). Human values: European social survey education net. Accessed Feb 5, 2019. Retrieved from http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/1/. ↩

-

Schwartz, S. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online reading in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). ↩

-

Reeves, J., & Lush, T. (2018). Hurricane Michael wipes out Mexico Beach, Florida, in ‘apocalyptic’ assault. Accessed Feb 16, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/ weather/hurricane/fl-ne-hurricane-michael-apocalypse-20181011-story.html. ↩

-

Perryman, D. R. (2018). The Perryman group - An Economic and Financial Anaylsis Firm. Accessed Feb 2, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.perrymangroup.com/hurricane-michael. ↩

-

National Weather Service. (2018). Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena. Accessed Feb 10, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.weather.gov/media/bmx/stormdat/2018/bmxoct2018.pdf. ↩

-

Goodman, L. A. (1961). Snowball sampling. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32(1), 148–170. ↩

-

AGCA (Associated General Contractors of America). (2018). Eighty percent of contractors report difficulty finding qualified craft workers to hire as association calls for measures to rebuild workforce. Accessed Feb 20, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.agc.org/news/2018/08/29/eighty-percent-contractors-report-difficulty-finding-qualified-craft-workers-hire-0. ↩

-

UNEP. (2019). UNEP-Environmental-Management-for-DRR. Accessed Feb 20, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.preventionweb.net/english/hyogo/gar/background-papers/documents /Chap5/thematic-progress-reviews/. ↩

-

Cox, C. (2019). Hurricane Michael, where did you put our reefs? Accessed Feb 19, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.starfl.com/news/20190228/hurricane-michael-where-did-you-put-our-reefs. ↩

-

NIST. (2017). WBDG – Whole Building Design Guide. Accessed Feb 22, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.wbdg.org/design-objectives/historic-preservation. ↩

-

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). (2015). Revisiting Kathmandu: safeguarding living urban heritage. UNESCO, Paris, France. ↩

-

Breaux, C. (2019). 5 historic Bay County sites after Hurricane Michael. Accessed Feb 1, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.newsherald.com/news/20190104/5-historic-bay-county-sites-after-hurricane-michael. ↩

-

Plough, A., Fielding, J. E., Chandra, A., Williams, M., Eisenman, D., Wells, K. B., Law, G. Y., Fogleman, S., & Magana, A. (2013). Building Community Disaster Resilience: Perspectives From a Large Urban County Department of Public Health. Promoting Public Health Research, Policy, Practice and Education, 103(7), 1190–1197. ↩

-

Chow, D. (2018). Conditions were ripe for Hurricane Michael's 'rapid intensification'. Accessed Mar 1, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/mach/science/conditions-were-ripe-hurricane-michael-s-rapid-intensification-ncna918711. ↩

-

Tompson, T., Benz, J., Agiesta, J., Cagney, K., & Meit, M. (2013). Resilience in the Wake of Superstorm Sandy. The Associated Press and NORC- Center for Public Affairs Research., Accessed Feb 20, 2019. Retrieved from http://www.apnorc.org/projects/Pages/resilience-in-the-wake-of-superstorm-sandy.aspx. ↩

-

Townshend, I., Awosoga, O., Kulig , J., & Fan, H. (2015). Social cohesion and resilience across communities that have experienced a disaster. Spring Link-Natural Hazards, 76(2), 919-938. ↩

-

LaLone, M. B. (2012). Neighbors Helping Neighbors: An Examination of the Social Capital Mobilization Process for Community Resilience to Environmental Disasters. Journal of Applied Social Science, 6(2), 209-237, Virginia, USA. ↩

-

Chang, K. (2010). Community cohesion after a natural disaster: Insights from a Carlisle flood. Disasters, 34(2), 289-302. ↩

-

DirectRelief. (2018). Hurricane Michael Strikes Some of the Nation’s Most Vulnerable Communities. Accessed Feb 19, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.directrelief.org/2018/10/hurricane-michael-strikes-some-of-the-nations-most-vulnerable-communities/. ↩

-

Vakis, R., Kruger, D., & Mason, A. D. (2004). Shocks and Coffee: Lessons from Nicaragua. Social Protection Discussion Paper No. 0415, The World Bank, Washington, DC. ↩

-

Vakis, R. (2006). Complementing Natural Disasters Management:The Role of Social Protection” Social Protection Discussion Paper No. 0543, The World Bank, Washington, DC. ↩

-

Millis, R. (2018). These are some of Florida's most vulnerable areas. And they're right in the path of Hurricane Michael. Accessed Feb 22, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story /news/nation-now/2018/10/09/hurricane-michael-targets-florida-poor-vulnerable-coastal-regions/1575641002/. ↩

Zhang, L., Pathak, A., & Ganapati, N. E. (2019). Stakeholder Values in Hurricane Michael: Understanding How Value Dynamics Contribute to Collaborative Decision Making in Disasters (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 293). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/stakeholder-values-in-hurricane-michael