The Impacts of COVID-19 on Gender Relations Amid Multiple Disasters In Coastal Ecuador

Publication Date: 2022

Abstract

This project analyzes the impact of multiple disasters and subsequent reconstruction initiatives on gender relations in a coastal Ecuadorian village. I focus on the aftermath of the 2016 earthquake and the COVID-19 pandemic in three neighborhoods that received differential outside support. While one neighborhood received no support, the other two received support from two organizations that employed different reconstruction strategies. Both provided housing for the two neighborhoods; one offered legal homeownership to women, seeking to build more equitable gender relations. With its distinct gendered landscape, this region offers an opportunity to gain comparative insights into how gender relations are reconfigured amid multiple disasters, including an unexpected pandemic, within households and communities. To analyze the gendered effects of post-disaster reconstruction, this project turns ethnographic attention toward the forms of connection, community, and kinship that have been created, changed, or dissolved amid multiple disasters; how women interpret and assign meaning to the disasters; and the impact that experiencing multiple disasters has on women’s capacities, strategies, work roles, and gender relations more broadly. By centering different forms of relationships, perceptions, care practices, and systemic dimensions, this project shifts the analysis of disasters from immediate consequences and suffering to the everyday spheres of transformation to explore the possibilities of change in gender relations in the wake of multiple disasters.

Introduction

Residents of Don Juan, a small fishing village on the coast of Ecuador, are familiar with different disasters. Through experiences of enduring floods, earthquakes, and pandemic crises, as well as responses to these events, socio-environmental disasters have become familiar, something that shapes thinking and ways of life. While external intervention is often motivated by the seemingly unambiguous moment of crisis, once the event evolves from urgency into a chronic state, strategies of interventions and their consequences can get complicated, particularly concerning gender relations when multiple and even overlapping disasters take place.

Disasters and health crises have gendered dimensions, an argument repeatedly recognized across disciplines (Enarson et al., 20181). Scholars have also made this point in the case of the global COVID-19 pandemic (Bahn & Cohen, 20202). Movement and confinement restrictions meant to contain its spread have affected individual and intra-household routines, exacerbating existing tensions or creating new ones (Rogers & Power, 20203). This has been especially challenging for households already burdened by recovery from recent disasters or living in socioeconomic precarity. These challenges are evident in Ecuador, which was one of the first Latin American countries to face a severe outbreak of COVID-19 (Johns Hopkins University, 2020). When containment regulations were imposed on overcrowded households, people faced difficulties obtaining food and medications, as well as maintaining access to utilities. Some cities even gained international attention because of the health system collapse.

As a result of multiple devastating events, social norms, gender expectations, relations, and personal aspirations in Ecuador have long been sustained and adapted in tension with messages and opportunities generated elsewhere. State and other development initiatives have long attempted to address gender and promote social equity through policies, reforms, and interventions (Guarderas 20164). This includes a reformed 2008 Constitution that framed its intervention around Buen Vivir or ‘good living’ (Colloredo‐Mansfeld et. al, 20185). Inspired by principles of socio-environmental solidarity, social equity, and Indigenous cosmovision, Buen Vivir influenced some post-earthquake funding projects for rural women to ensure equitable access to housing and land (SENPLADES, 20176). While some organizations and local leaders in Ecuador adopted these principles, expectations of gender equity have rarely been realized (Radcliffe, 20157). Rebuilding has therefore been shaped by a wide range of tumultuous political dynamics which failed to provide sustainable reconstruction solutions in rural areas of Ecuador (Waldmüller & Nogales, 2022)8. The lack of support exacerbated difficult conditions for people.

A watershed moment for analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender dynamics in Don Juan includes not only the socio-environmental disasters, but also the subsequent reconstruction initiatives, particularly asset allocation for women. In 2018, after the devastating earthquake, women in Don Juan, who have long struggled with gender-based and systemic violence, were targeted as agents of change. An Ecuadorian organization designed a post-earthquake housing complex where women became legal homeowners and received workshops on empowerment, positive co-living arrangements, reproductive health, and violence prevention. The change was anticipated at the site and scale of women’s bodies and their households to build a different future with more equitable gender relations. While these are promising directions, anthropological literature on women and development programs of the 1980s-1990s draws attention to unintended consequences of initiatives that target solely women as agents of change, particularly when structural issues are not addressed (Bhavnani et al., 20169; Gardner & Lewis, 201510).

As I consider gender relations from the perspective of women, I analyze how the needs for survival and desire to build different futures create new alliances, relations, forms of care, friendship, work roles, and living arrangements among people in a rural village in coastal Ecuador. I approach disaster recovery through an intersectional lens, to understand how gender intersects with other aspects of identity and difference, not just those concerning disaster and development. Inspired by feminist scholars (Lugones, 200711; Mohanty, 198812; Yuval-Davis, 201113), I use intersectionality as a methodology, epistemology and as a paradigm to analyze the intersecting social realities; systems of gender and gender identities (masculinities, femininities), ethnicity, race, socioeconomic position, cultural location, and environment. Inspired by ways through which they intersect with each other, but also in how they intersect with the “processes that shaped those emerging social orders and identifications” (Paulson, 201614, p. 400).

In this report, I present preliminary observations on whether and how households, and the men and women within them, in three neighborhoods with differential outside support reveal different capacities that enable or inhibit compliance with COVID-19 and subsequent regulations. The Natural Hazards Quick Response grant funded a portion of a larger dissertation project that analyzes the impacts of multiple disasters and subsequent initiatives on household and community dynamics.

Literature Review

In recent decades, anthropologists have contributed to a multi-dimensional understanding of disasters as processual phenomena wherein human and structural factors play a critical role in co-producing such events (Fjord, 201015; Barrios, 201716). Approaching disasters as processes, not as events, helps us understand ways in which the experience of disasters and recovery differ, and why some groups even thrive in the aftermath. These factors include local norms, values, historical conditions, external intervention, and power dynamics (Marino & Faas, 202017). Multiple disasters may further complicate recovery, as they arrive in different temporal frameworks, sparking a range of changes. In disaster contexts, where change might occur faster, sociocultural systems are framed as persistent, with possible changes emerging immediately after a disaster, but ultimately vanishing (Hoffman, 201618; Moreno & Shaw, 201919; Zhang, 201620). Significant to my project, long-term research can uncover whether gender relations and social conditions more broadly change at different stages of recovery.

Socio-environmental and health disasters have gendered dimensions, something that is recognized across disciplines (Enarson & Pease, 201621; Phillips, 202022). While gender and sexuality inexorably shape the social worlds in which disasters unfold, there is no unilateral way in which that occurs. Gender and disaster literature has portrayed women either as vulnerable—particularly regarding gender-based violence, labor devaluation, and political exclusion—or as resilient, and sometimes both (Bradshaw & Fordham, 201323; Browne, 201524; Phillips, 2020). Such binary constructs of gender and associated roles have ignored the complexities of gender relations. I approach gender as a sociocultural system, acknowledging that disasters can open a space for sociocultural and gender shifts: I consider not only roles among differently-positioned actors but also their relations (intimate, sexual, community, familial), perceptions, practices, attachments, emotions, affect, and care within a systemic frame (Martin, 200425; Paulson, 201526). This framework enables a multi-scalar analysis beyond the assumed gendered notions that have become associated with the performance of men and women, as well as those people who do not fit the binary.

In disaster and non-disaster contexts alike, housing provision has been established as one of the crucial catalysts for socioeconomic and gender change (Peacock et al., 201827). Feminist economists argue that owning a home can enhance women’s ability to respond to different shocks (domestic, environmental, health, etc.) and their sense of security; can engender new forms of decision-making and enhance the ability to make life choices; and can lower incidence of gender-based violence (Deere, 201628; Fay, 200529). Yet, the road to change may be more complex, particularly as intimate relations can be reshaped in unexpected ways amid multiple disasters. Furthermore, the value placed on newly acquired assets may differ, particularly when imposed in a context where they were previously not common, as is the case in Don Juan (Bradshaw, 201530). Thus, this project contributes to the literature on assets, gender, and disasters by empirically analyzing the changes that housing provision or gender-focused reconstruction can bring to gender relations and how those continue amid an unexpected disaster such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research Design

This project seeks to empirically examine how COVID-19 can impact gender relations in a coastal Ecuadorian village that is still undergoing recovery from previous disasters: El Niño high tides, seasonal rains and subsequent floods, the 7.8 magnitude earthquake in 2016, and subsequent resettlement and reconstruction processes. My fieldwork took place in three neighborhoods of Don Juan that received differential support after the 2016 earthquake: private intervention, government intervention, and no intervention. These distinct cases offer an opportunity to gain comparative insights into how gender relations can be reconfigured in the wake of disasters and how material investments can work as social engineering projects that bring changes to once-marginalized groups. The comparative research design is critical in investigating how models of COVID-19 containment that appear similar in theory might translate differently across various domains of life and work, particularly for women. The social experiment of the two neighborhoods that received differing levels of asset support with varying levels of community engagement offers a unique possibility to study the mechanisms that condition post-disaster trajectories. Drawing on literature and preliminary research, I expected different impacts on household and community relations in cases where women received housing titles and gender workshops. I expected those women to show greater capacity to deal with adversity arising from COVID-19.

Research Questions

The primary questions driving this study include:

- How have residents, particularly women, interpreted, understood, and assigned meaning to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent initiatives?

- What forms of connection, care, community, and kinship have been created, changed, or dissolved since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How has the response to COVID-19 and associated regulations affected intra-household and community gender dynamics?

- How does experiencing multiple disasters affect women’s capacities, strategies, and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic?

Study Site Description

Don Juan is located in coastal Ecuador, in a rural region characterized by high rates of illiteracy, unemployment, and gender-based violence. The 2016 earthquake of 7.8 magnitude destroyed 98% of its existing infrastructure, leaving 668 dead and over 200,000 people without housing. Many residents were relocated to temporary tent settlements donated by the Chinese Red Cross. But the types of post-disaster housing support in Don Juan varied significantly by neighborhood. Housing reconstruction efforts were undertaken by the government and private organizations. In early 2018, some people received housing and other aid, but those interventions were later interrupted by the pandemic.

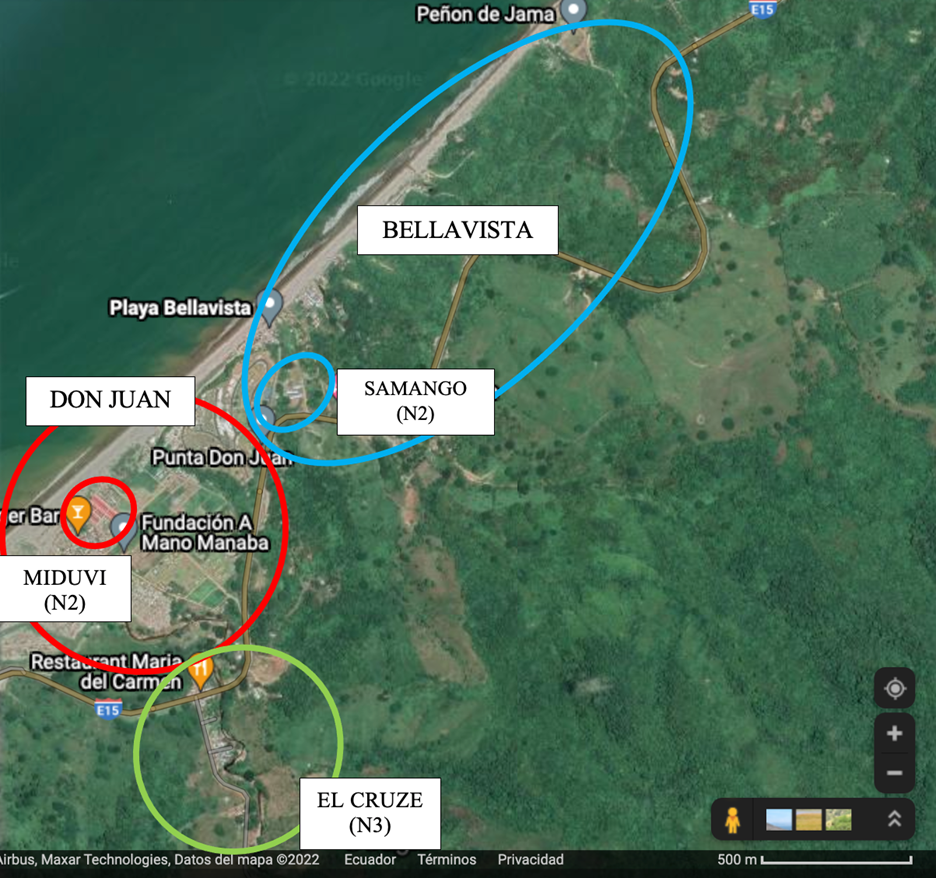

I selected three neighborhoods as sites for this study because they experienced three different types of post-disaster interventions. The first neighborhood, called Samango, received support from a private organization to build 18 housing units for disaster survivors. The second neighborhood was financed by the Ecuadorian government and is known as MIDUVI, the Spanish acronym for the Ministry of Urban Housing and Development (Ministerio de Desarrollo Urbano y Vivienda, in Spanish) which was responsible for building its 68 homes. The third neighborhood, El Cruze, is located farther inland and received no outside support for housing reconstruction. In stark contrast to the other neighborhoods, the only resources that El Cruze received consisted of occasional food donations. Table 1 compares the three sites and the forms of post-disaster aid they received. Figure 1 is a map of the three neighborhoods and Figure 2 depicts photos of their post-disaster housing.

Table 1. Description of Post-Disaster Aid Received in Each Neighborhood Site

| Neighborhood | Samango | MIDUVIa | El Cruze |

| Approximate Number of Households | 80 | 120 | 85 |

| Number of Households That Received a New House | 18 | 68 | N/A |

| Source of New Housing | Private intervention (An Ecuadorian organization with international funding) | Government intervention (Former Ministry of Urban Development) | None |

| Types of Post-Disaster Support | Housing, community development workshops, food and material support | Housing, food and material support | Food and some material support |

| Year of Implementation | 2018 | 2018 | N/A |

| Housing Co-pay | $500 | $0 | N/A |

| House Ownership | Women | Not specified | N/A |

| Housing Size | 2.5 bedrooms, 1 bath | 2 bedrooms, 1 bath | N/A |

| Process for Assigning Homes | Very clear to the people receiving houses | Unclear to the people receiving houses | N/A |

| Level of Post-Disaster Support and Community Engagement | High; aimed at women but engaging all community members | Medium; provided housing with little guidance and support but some community consultation | Minimal support; limited economic means, no community consultation since 2016 |

Figure 1. Map of Neighborhoods Selected as Study Sites: Samango, MIDUVI, and El Cruze

Figure 2. Post-Earthquake Housing in Samango, MIDUVI, and El Cruze

Don Juan is located in the province of Manabí where the main sectors of economic activity are small-scale fishing and shrimping, agriculture, and, more recently, tourism and construction work. According to my household survey, about 1,000 people live in Don Juan. On average, four children live in each household. It is home to people who identify as “Montubios,” an ethno-racial minority that honors their cultural festivals, oral tradition, gastronomy, and customs related to aquaculture and agriculture. Most families depend on income generated and controlled by men, though more women have been securing employment in the last 10 years, since fishing has become less lucrative and more tourist establishments have been built.

The province of Manabí is often stereotyped within the Ecuadorian imaginary. For example, men are portrayed as hard-working, focusing on activities related to fishing or agriculture, yet aggressive, and inclined to resolve conflict with violence. Women are constructed as docile, dedicating their time to household chores and childcare, and often suffering at the hands of their partners (deWalt, 2002; Friederic, 201431). My project shows that reality is more complex, and that different relations, identities, and expressions of gender and sexuality are always intersecting and in dynamic tension.

Data, Methods, and Procedures

I draw on 22 months of intermittent fieldwork that I started one month after the 2016 earthquake. I have returned every year since. Specifically, this grant supported fieldwork between July and November 2021. I initially proposed to conduct this research between January and March 2021, but due to pandemic-related complications, I had to postpone fieldwork until Summer 2021, after the majority of people, including myself, had been vaccinated. I used engaged ethnographic methods (participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and oral histories) and a survey to address my research questions.

First, I engaged in intentional and systematic observant participation in beach areas, where people return from fishing; convenience stores, where they shop; community centers, where they gather occasionally; and in post-earthquake housing settlements, where they spend most of their time. To analyze household and community dynamics, I accompanied people in daily activities usually undertaken by men (fishing, sorting fish, playing sports) and women (cooking in their kitchens, selling at the stores, playing bingo). I paid attention to participation by gender in different activities and public meetings (e.g., who got to speak). I lived in the heart of the village with a local family, within walking distance of the three neighborhoods where the study took place. The proximity of the three sites made the ehtnographic methods in this project feasible

Second, as depicted in Table 2, I conducted semi-structured interviews with men and women and a survey to obtain some demographic data. I also conducted oral histories to gain a deeper understanding of the village’s historical trajectories since there are few written sources on the topics. In my interviews, I talked about the impacts of COVID-19 (e.g., sickness, death, or unemployment) as well as changes in intrahousehold and community dynamics (e.g., roles, routines, conditions, organization, and expectations) during and after the pandemic, which I compared with the data I collected before. Inspired by the guidelines published by the CONVERGE COVID-19 Working Group (202032) that addresses the empirical gaps in cumulative disaster studies, I paid specific attention to the experience of a prior disaster; the acquisition of new awareness in the form of new capacities, strategies, and skills gained from prior disaster experience, as well as how they enable or constrain adaptations to the COVID-19 pandemic; and the way civic actors, disaster response professionals, and others understand the local context.

Table 2. Interview Sample

| Number | Samango | MIDUVIa | El Cruze |

| Interviews (men) | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| Interviews (women) | 10 | 12 | 10 |

| Oral History (men) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Oral History (women) | 2 | 3 | 1 |

Finally, I volunteered with A Mano Manaba Foundation , a local community library that was started after the earthquake in 2016 (Photo 7). There, I organized workshops and conversatorio (conversation circles) that have a similar format to focus groups but a less structured structure (e.g., the questions are more open-ended). Our collaboration is part of a “co-labor project,” with the researcher and participants entering into a series of conversations and interchange of ideas over the course of the study (Mora 2017). This process engages methods that seek to recover and illuminate both individual perspectives and collective memories constructed from oral traditions, storytelling, and everyday practices. This project arose out of consultation with community members and is designed to be conducted in collaboration with community organizations and partnerships. In 2018, I launched a cookbook project with local women who were affected by the earthquake that gained a lot of popularity and helped me build rapport with community members. In early 2020, I started a photovoice project with women to better understand and express the needs and struggles of local people. I have worked as volunteer at A Mano Manaba, organized a number of programs and workshops with women and girls, facilitated visits from other people who came to work with the community, and helped with grant writing.

My research has been directly impacted by disasters, including the COVID-19 pandemic, which I experienced in Don Juan. The experience deepened my understanding of the impacts of disasters, as well as the relationship within the community, including politics of care and trust. Thus, rather than focusing on suffering and powerlessness, which tend to dominate disaster research, I follow Eve Tuck’s (2009) proposal for a “desire-based” framework that accounts for trauma but centers on future visions and regeneration. As many women do, particularly survivors of domestic abuse, I frame disasters as a window of opportunity for change, a future-oriented approach that rethinks vulnerability and emphasizes resilience as key to reframing how we understand gender relations amid multiple disasters.

Sampling and Participants

I used snowball sampling for ethnographic semi-structured interviews and stratified random sampling for my survey. However, this report focuses on qualitative data, as I have not been able to analyze the 500 households included in the survey. This was my fifth trip to Don Juan so I have built a strong rapport with the residents across three villages, which made it easy to access individuals. I conducted 55 interviews, with 23 men and 32 women between the age of 18 and 75 (10 women and nine men in Samango; 12 women and eight men in MIDUVI; 10 women and six men in El Cruze). I also conducted eight oral histories (two men and six women), and surveyed 500 households, which I have not been able to analyze. Oral histories took place in people’s houses where I also took their portrait photos, to include with their narratives in a digital archive that I am currently building.

The interviews took place in Spanish and lasted between 45 and 180 minutes (100 minutes on average). I recorded and later transcribed the interviews, translated them into English and had them checked by a native speaker of Spanish who is fluent in English. The participation was voluntary and not-compensated. All of them took place in person in people’s houses or yards. The 23 interviews conducted between October and December 2020 were taken at a “research station”, which I set up on the beach in an open space, where I was able to be masked and sit over 6 feet away from the interviewee.

Ethical Considerations, Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Considerations

This project received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of North Carolina (#18-0863) in September 2020 and was renewed in August 2021, after I arrived in Ecuador and was able to evaluate the situation and adjust the research protocol. I postponed the return trip to Ecuador because of the pandemic and returned after everyone in the village had been vaccinated. Even before Ecuador made vaccination mandatory on December 23, 2021, the overwhelming majority of its citizens got vaccinated, as it was a mandatory requirement to receive El Bono de Desarrollo Humano (Human Development Voucher). I also asked each person I interacted with whether they have gotten vaccinated to which everyone replied affirmatively. I was also able to conduct interviews in open spaces, which was not a particular challenge because majority of people spend most of their time outside. We did, however, wear masks and keep a safe distance.

The people I interviewed are familiar with me and feel comfortable in my presence so I did not face many challenges getting an interview with them. Group activities were made more difficult, as people preferred to stay in smaller groups of people. I have been coming to Don Juan since 2018, and worked in other parts of Ecuador since 2016, when I was working with a Quito-based organization that supports women and children who experience gender-based violence. When the earthquake struck, we got engaged with coastal communities in need, which is how I ended up on the coast: first in a community in the northern province of Esmeraldas in 2017, and then Don Juan in 2018. I connected with A Mano Manaba, proposed a project to them, and received their support and approval. However, I have always had free reign to conduct my research without strings attached. My constant presence has helped me develop deep relationships with people, speak Spanish fluently, and have a solid understanding of the local boundaries, norms, and values.

Findings

To discuss my findings, I first contextualize the COVID-19-related results within the broader project that examines multiple disasters, housing, and gender. I completed my dissertation fieldwork on December 1, 2021 so data analysis is still in progress.

Material Resources

My preliminary results show that providing built assets to women and accompanying those with workshops in the wake of a devastating disaster could challenge existing power relations and spark long-term transformation. In Samango, where women obtained housing, I observed improved agency among women within their households, such as having the courage to speak up in public community meetings or to make strategic life decisions (e.g., whether they work or study), which was absent in the other two sites. Women are used to saying “eso es mi casa” to their partners (this is my house) when an intra-household conflict arises, telling their often-violent partners that they are free to leave if there is something that bothers them. They report feeling safer about their children and their future and confirm that their neighbors share the same sentiment.

However, despite some improvements, women still economically depend on their partners, particularly in the absence of income-generating opportunities for women. Thus, issuing a title in a context where women rarely own assets does not automatically change the social norms that influence who is assumed to have the right to participate in owner-driven reconstruction. On the community level, different post-disaster initiatives also contributed to new forms of othering, where the women who did not receive the same post-earthquake attention are seen as less worthy than those who did. Women will often refer to residents of other post-earthquake settlements as “the disorganized ones,” and don’t want to be associated with them, even them a lot of them are their biological family.

These findings suggest that the participation of households in post-earthquake relief responses deeply influenced their resources and dynamics. This has in turn impacted how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced these households. Household members who participated in post-earthquake workshops led by organization staff on conviviality (e.g., agreeable community living, work organizations, etc.) and gender-based violence seemed to have created communities within each post-earthquake housing settlement with shared values particularly among women. As I discuss later, these factors impacted the pandemic experience.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic affected perceptions of the gravity and risk associated with the 2016 earthquake. The residents consider the COVID-19 pandemic to be the most devastating disaster yet. During an interview, my friend Viviana (pseudonym), a 27-year-old mother of three, gave me an explanation as to why:

“So many people died in this pandemic. It has been a time of scarcity. The earthquake…was a time of abundance. So many people and goods came through our village. Now we have needed to be very self-sufficient because the catch from fishing has been bad and the flow of manufactured goods stopped.”

The material cost of the pandemic paired with a lack of medical attention and information scared people, but many said they were used to different forms of sharing resources that they undertook during previous disasters. This is because the majority of families were relocated after the El Niño high tides and later, the earthquake led to government-managed relocation, where 80-120 people had to cohabitate in small tent settlements. Thus, in some ways, people were prepared to respond to a new disaster such as the pandemic, but the different forms it took (from floods or earthquakes) scared them in ways that previous disasters did not.

Technology and Communication

I also attribute the different perceptions of gravity to another big change: technology. As the schools stopped in-person teaching and everything moved online, there was an increased demand for technology and reliable Wi-Fi in homes. The school work was distributed by WhatsApp, which meant that most households had to get a smartphone and secure internet. At the same time, people were able to receive more information about the pandemic via this technology, which many cited as anxiety-inducing. Carolina, a 33-year-old transwoman and a security guard in nearby gated community said that she was “glued to the news” and didn’t even want to leave her house (she was not needed at work as the tourist establishment where she works closed for anyone who did not live there). The majority of neighbors shared the same sentiment and attributed their paranoia to the news. In contrast, during the earthquake, people didn’t have phone reception let alone the internet, unless you went to one of the towns located 15-30 minutes away. Before 2020, only a few households had internet, in addition to the local community center, A Mano Manaba.

Adaptation and Previous Experiences of Disaster

Furthermore, my results suggest that the previous experience of disaster-impacted adaptations to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the way civic actors, disaster response professionals, and others understand the roles of the local groups with whom they work.

When the government announced a lockdown on March 12, 2020, the community quickly self-organized and enforced its own rules. Northern Manabí is often seen as a place exempt from and ignored by the Ecuadorian legal system, mostly because of its remote location and historically-rooted discriminatory practices (Friederic 201133). Yet, the inhabitants are used to taking law and order into their own hands, and justice is enforced by la ley el machete, or “the machete law.” During quarantine, a rotating group of men protected the entrance of the village so that people couldn’t pass without being screened, thus protecting the two neighborhoods that had previously received housing support. The third one, located on the other side of the road, was left unprotected. The screening process mostly involved taking temperature and checking whether you knew the person wanting to enter the village. If they didn’t know you were a threat and they would not let you through. If they did know you, they would let you enter but would fumigate you first. If you had been gone for days, you would have to quarantine in a tent, a relic from the earthquake. These mechanisms were in place until June 2020, when the government-imposed curfew (between 2 pm and 5 am) was removed.

Residents told me that the rotating groups of men organized organically, and while most people considered that form of community protection effective, others considered it to be pure "negocio" (business) as some were alleged to receive bribes and “special treatment” (e.g., they were first in line to receive food from a poorly-stocked vegetable truck that occasionally came into the village, or they would let people in who were possibly sick or not related to anyone in the village without being fumigated and/or quarantined). The groups were also formed based on pre-existing hierarchies (e.g., the members from the more influential homes were put in charge), which bothered some community members. The consensus, however, was that they protected the community and prevented the entry of many people from different cities, particularly Guayaquil; some even attempted to enter by boats. This was critical because there was no support from the state.

Despite the lack of material, medical, and economic support, most residents considered the remoteness of the village to be an advantage in surviving the pandemic. Viviana, a 53-year-old widow, said that she felt sorry for the people in the cities because “they don’t have a neighbor who will give them a piece of fish, nor can they gather in the open air.” After dwelling on economic hardships, she said: “I now see the earthquake more maturely…I am humbled. It taught me a lot. It felt manageable when it happened, even though we lived in tents for two years. Time feels different now, in this pandemic. It is so much harder.” Her words show that the imprints of disaster trauma that she and so many others are still trying to make sense of are deeply related to the earthquake and that new forms of understanding are coming into existence through experiencing the pandemic. The changing perceptions of the previous disaster are a complex and continuous process.

Homeownership and Household Response to the Pandemic

The households where women are homeowners reported less change and more cooperation within households and communities during COVID-19. Increased conflict and anxiety were common changes in other sites. While coping with and weathering the impacts of aftershocks after the earthquake, people, particularly women, have persisted in trying to transform and adjust their conditions of life. In the absence of support from the state, tight-knit relationships have shaped everyday social and economic exchanges even during the pandemic, where care has been a relational practice and collective responsibility of everyone who belongs to this community. Many families ended up hosting family members from other villages in their small, 1 or 2-bedroom homes that they were assigned after the earthquake, which led to housing struggles, such as overcrowding and lack of food. However, many agree that it was also a blessing because they got to spend a lot of time together.

When talking about their quarantine experience, the women in Samango suggested a significantly more positive account than women in the other settlements, saying that not much has changed for them because they have enjoyed being inside their homes, the homes that they own. Meanwhile, people in MIDUVI and El Cruze were not shy about sharing stories of quarantine violence and hardship. Whether that means their experience is harder or women in Samango are just reluctant to share might become clearer with more time and analysis. The struggle can be summarized in the words of Yolanda, a 23-year-old mother who lives with her partner, from Samango:

“There isn’t much to say [about intra-household violence]. Whatever happens in each house stays there and it should stay there! But you know that the walls are thin. Our walls weren’t supposed to touch but they ended up building the houses that way. We can hear everything. But we don’t want any issues so we don’t talk about it.”

This effort for those from Samango to hide what they’d perceive to be scandalous to live up to the expectations of a peaceful community could be a consequence of participating in the post-earthquake workshops, where they emphasized the importance of neighborhood harmony. It is also apparent in people’s accounts of how solidarity and household relations are negotiated. Yolanda said, “We just want to make it work. I never thought that I would be living with these people, sharing everything, making the rules. We want this community to get along. It feels good to know that my kids will always have a place to live.” Women in Samango did emphasize that men stopped drinking, mostly due to economic constraints and fear of how that would increase the likelihood of contracting COVID-19.

It is difficult to know with certainty how many people got COVID (as opposed to dengue or the flu) as no tests were done during the height of the pandemic or over 2021. Even more, having experienced COVID-19 almost became a source of pride. The local people mobilized ancestral knowledge and skills, including the use of herbs, teas, and home remedies to cure COVID-19 symptoms. Only two people, both with pre-existing health conditions, died due to COVID-19. However, more analysis is needed to determine the factors that impacted the spread, and many likely have to do with intimate care practices and with infrastructure, as well as with home conditions (e.g., how many people live in one house).

Conclusion

While my findings require more analysis, preliminary results show that providing built assets to women and accompanying those with workshops could challenge existing power relations and spark transformation after a disaster. This shows how people, especially women, experienced the pandemic.

First, regarding how the residents, particularly women, understood and interpreted the pandemic, my findings show that they view it as the worst disaster to have ever happened to Don Juan. The residents were scared, material goods were scarce (which did not happen during previous disasters), and they lacked medical attention. However, this created an opportunity to deepen care relations among neighbors. People would take turns going grocery shopping in a nearby town, either by bike or with one of the three cars in the village, or to trade goods (e.g., rice, fish, vegetables), depending on the supply. In search of social connection, some people created pods to stay outside and play board games with each other, and took turns in supervising when the police would come to check whether somebody was breaking the curfew.

Second, the pandemic and associated regulations had a differential impact on household and community relations in the three neighborhoods my study focused on. My findings suggest that the people in Samango, the neighborhood where people were subjected to the targeted, gender-focused reconstruction process, reported fewer changes and even fewer hardships than the households in MIDUVI and El Cruze. More analysis will reveal the factors associated with this. At the same time, women reported improved intrahousehold relations, as many men stopped drinking (which is a deep and widespread problem) during the quarantine. In terms of community relations, people reported increased cooperation and solidarity (e.g., local grocery stores sold goods by credit instead of cash, trusting that the people will pay it off once the financial situation is better; people shared their food with neighbors).

Finally, my findings suggest that experiencing multiple disasters affects people’s capacities and responses to future disasters. While more analysis is needed to elaborate on this argument, this was particularly clear in the immediate response to the pandemic; when the flow of goods stopped and there was no clear guidance on how to respond, people immediately self-organized to protect the village based on lessons learned after the 2016 earthquake. People’s perceptions of previous disasters, particularly of the earthquake, changed with the pandemic and how the state responded to it, and many expressed, albeit jokingly, a wish to have an earthquake every year, as it was a time of great abundance of material resources, volunteers, solidarity, and hope for a better future.

Limitations and Strengths

The biggest strength of this project is the in-depth ethnographic approach to research. I have built rapport with people, which allowed me to live in Don Juan during the COVID-19 pandemic and get a deep insight into their intimate lives for over 22 months. Because of that, I was able to easily access community members and get details of their lives that I would not have otherwise.

One of the limitations is that there hasn’t been a census in Ecuador since 2010; one was planned for 2020 but was canceled due to the pandemic. Thus, I lack the current demographic data of the residents. I was able to perform a house and population count and collect basic demographic questions. However, I was not able to get more systematic data on work, religion, and other population characteristics. Anything more elaborate would be difficult because (a) people are used to getting paid to participate in a census, which I would be unable to facilitate, and (b) there is a lot of flux in terms of migration, work, and the number of people living or sleeping in each house. The pandemic posed other research limitations, such as the inability to carry out some of the participatory action research methods planned for this project (e.g., photovoice), as the people felt uncomfortable doing group activities with people that weren’t part of their small, isolated social circle.

Future Research Directions

This is the first ethnographic study on the northern coast of Ecuador. As such, there are a few avenues for future research directions. First, there is a continuous issue with housing titles in MIDUVI where houses were provided by the government but official documentation related to titles has not been issued. While my research has already attempted to investigate this issue, more research is needed over the next 2 to 3 years to understand how the local and national governments will address the inconsistencies and assign housing titles, if at all), and what kinds of system inconsistencies that reveals, particularly in regards to disaster preparedness and recovery.

Second, while this study considers men’s perspectives, it nevertheless prioritizes women’s stories. A deeper analysis of changing men’s attitudes, behaviors, practices, and values would enable a better understanding of the changing gender relations in Ecuador. Men are less often considered as gendered subjects with their own struggles, so a rigorous analysis would enable a more critical discussion of changing gender norms and the roles that men play in the community, specifically now when fish products, and thus their livelihoods, are in decline.

Third, with the arrival of technology and more widely-accessible internet in Ecuador, I observed significant changes in visions, values, and behaviors among people younger than 25, and specifically among teenagers. This was also evident in the response to the pandemic, where a younger generation suddenly received access to Wi-Fi—which was critical for communication during the pandemic—and smartphones. An intra-generational study could contribute to an understanding of youth’s needs, particularly as the majority struggles with finishing school, finding jobs, teen pregnancy, and substance abuse. This analysis needs to be done while taking into account the local community library built after the earthquake, which offered a safe space and reading hours to the youth and has the potential to improve literacy levels and career-related decisions and directions.

Finally, as this research took place before, during, and after disasters, it will contribute methodological insights to ethnographic research on disasters that can be applied across the world, but particularly in smaller, rural, or coastal regions.

Implications for Practice and Policy

As disasters become more frequent and severe, and gender-sensitive responses become more common, this project has the potential of reaching a wide audience. This includes those affected by disasters, disaster analysts, and organizations involved in gender-focused disasters and COVID-19 relief. My work has the potential to inform preparedness and recovery plans that can be implemented in similar settings to improve people’s capacity to recover before another hazard strikes. It will also contribute to an understanding of how successive disasters change the awareness and capacities of people across various domains of life and work as well as of the differential factors that enable and inhibit compliance with COVID-19 regulations. While this is a context-specific study, some of its findings can be applied to similar settings (rural, low-income) that have lived through a single or multiple disasters.

These findings have several implications for policymakers at the international, national, and local levels. Although gender is often integrated into development and disaster recovery, gender dynamics play out differently across different contexts. My research considers local variations and access to support, bringing attention to gender equity and housing.

Disaster development practices infrequently consider input from the social sciences. This project remedies that by generating qualitative data on gender equity, providing policymakers a clearer picture of the complex social processes that unfold amid multiple disasters, particularly amid the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. It has the potential to better inform policy to counteract gender-based vulnerabilities in future disaster relief efforts, thus contributing to dialogues between development workers, government officials and policymakers, and the populations they seek to help.

Furthermore, there is a need for close collaboration among actors involved in post-disaster recovery to ensure equal access to shelter and shelter-related resources. These resources are not enough on their own; they should be accompanied by workshops and information to ensure that people’s voices are heard and their housing-related concerns are addressed. Moreover, policymakers could build on and strengthen the assets and knowledge of displaced populations, particularly in areas that are prone to disasters. They could initiate leadership programs at the community level to accompany people in grassroots organizing; provide financial, technical, and material support to the community and community-based organizations; and work with local leaders. Finally, there is a need for more significant involvement of medically-trained personnel in local politics. The lack of medical attention, resources, and knowledge was palpable during the pandemic when people needed to use home remedies as there was no access to medication.

References

-

Enarson, E., Fothergill, A., & Peek, L. (2018) Gender and Disaster: Foundations and New Directions for Research and Practice. In Havidan R., Quarantelli E., & Dynes Russel (Eds.), Handbook of Disaster Research (pp. 205-223). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_11 ↩

-

Bahn, K., Cohen J., & Rodgers, M.Y. (2020). A Feminist Perspective on COVID‐19 and the Value of Care Work Globally. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(5), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12459. ↩

-

Rogers, D. & Power, E. (2020). Housing Policy and the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Importance of Housing Research During this Health Emergency. International Journal of Housing Policy 20(2), 177-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2020.1756599 ↩

-

Guarderas, A. P. (2016). Silencios y Acentos en la Construcción de la Violencia de Género como un Problema Social en Quito. Íconos - Revista De Ciencias Sociales (55), 191-213. ↩

-

Colloredo-Mansfeld, R., Lyall, A., & Rousseau, M. (2018). Development, Citizenship, and Everyday Appropriations of Buen Vivir: Ecuadorian Engagement with the Changing Rhetoric of Improvement. Bulletin of Latin American Research 37(4), 403-416. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.12742 ↩

-

SENPLADES. (2013). “Plan Nacional de Desarrollo/Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir, 2013 2017.” Quito: Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo. ↩

-

Radcliffe, S. A. (2015). Dilemmas of Difference: Indigenous Women and the Limits of Postcolonial Development Policy. Duke University Press. ↩

-

Waldmüller, J.M. & Nogales, N.G. (2022). La Noche Que Tembló Ecuador. Abya Yala. ↩

-

Bhavnani, K., Foran, J., & Kurian, P.A. (2016). Feminist Futures: Reimagining Women, Culture and Development. Zed Books Ltd. ↩

-

Gardner, K. & Lewis, D. (2015). Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century. Pluto Press. ↩

-

Lugones, M. (2007). Heterosexualism and the colonial/modern gender system. Hypatia, 22(1), 186-219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2007.tb01156.x ↩

-

Mohanty, C. T. (1984). Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses. Boundary 2, 333-358. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.1988.42 ↩

-

Yuval-Davis, N. (2016). Power, Intersectionality and the Politics of Belonging. In The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Development (pp. 367-381). Palgrave Macmillan, London. 10.5278/freia.58024502 ↩

-

Paulson, S. (2016). “Towards a Broader Scope and More Critical Frame for Intersectional Analysis.” In Harcourt, W. (Ed.) The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Development. (pp. 395–434). New York, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ↩

-

Fjord, L. (2010). Making and Unmaking Vulnerable Persons: How Disasters Expose and Sustain Structural Inequalities. Anthropology News. 51(7), 13-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-3502.2010.51713.x ↩

-

Barrios, R. (2017). Governing Affect: Neoliberalism and Disaster Reconstruction. University of Nebraska Press. ↩

-

Marino, E. K., & Faas, A. J. (2020). Is Vulnerability an Outdated Concept? After Subjects and Spaces. Annals of Anthropological Practice: 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12132 ↩

-

Hoffman, S. M. (2016). The question of Culture Continuity and Change after Disaster: Further Thoughts. Annals of Anthropological Practice 40(1), 39-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12086. ↩

-

Moreno, J., & Shaw, D. (2018). Women’s Empowerment Following Disaster: A Longitudinal Study of Social Change. Natural Hazards 92(1), 205-224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3204-4 ↩

-

Zhang, Q. (2016). Disaster Response and Recovery: Aid and Social Change. Annals of Anthropological Practice 40 (1), 86-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12090 ↩

-

Enarson, E. & Pease, B., eds. (2016). Men, Masculinities and Disaster. Routledge. ↩

-

Phillips, B. D. (2020). Disrupting Gendered Outcomes: Addressing Disaster Vulnerability Through Stakeholder Participation. In Hoffman, S. M. & Barrios, E. Disaster Upon Disaster: Exploring the Gap Between Knowledge, Policy and Practice (pp. 172-197), Berghahn Books. ↩

-

Bradshaw, S. (2013). Gender, Development and Disasters. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham/Northampton. ↩

-

Browne, K. E. (2015). Standing in the Need: Culture, Comfort, and Coming Home after Katrina. Austin: University of Texas Press. ↩

-

Martin, P. (2004). Gender as a Social Institution. Social Forces 82 (4), 1249-1273.https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2004.0081 ↩

-

Paulson, S. (2015). Masculinities and Femininites in Latin America’s Uneven Development. Routledge. ↩

-

Peacock, W. G. (2018). Post-Disaster Sheltering, Temporary Housing and Permanent Housing Recovery. In Rodriguez, H., Quarantelli, E., & Russel, D. (Eds.), Handbook of Disaster Research. Springer (pp. 569-594), Springer, Cham. ↩

-

Deere, C. D., Contreras, J., & Twyman, J. (2014). Patrimonial Violence: A Study of Women’s Property Rights in Ecuador. Latin American Perspectives 41(1), 143-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582x13492133 ↩

-

Fay, M. & Ruggeri, L. C. (2005). Relying on One’s Self: Assets of the Poor. In Fay, M. (Ed.) The Urban Poor in Latin America (pp. 195-218). Washington D.C.:World Bank. ↩

-

Bradshaw, S. (2015). Engendering Development and Disasters. Disasters, 39(1), 54-75. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12111 ↩

-

Friederic, K. (2014). “Violence Against Women and the Contradictions of Rights-in-Practice in Rural Ecuador.” Latin American Perspectives 41(1), 19-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X13492140 ↩

-

CONVERGE COVID-19 Working Groups for Public Health and Social Sciences Research Agenda-Setting Paper. (2020). Cumulative Effects of Successive Disasters. ↩

-

Friederic, K. (2014). “Violence Against Women and the Contradictions of Rights-in-Practice in Rural Ecuador.” Latin American Perspectives 41(1), 19-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X13492140 ↩

Jeranko, M. (2022). The Impacts of COVID-19 on Gender Relations Amid Multiple Disasters In Coastal Ecuador (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 340). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/the-impacts-of-covid-19-on-gender-relations-amid-multiple-disasters-in-coastal-ecuador