Trajectories of International Student Psychological Functioning and Pandemic Preparedness During COVID-19

Publication Date: 2020

Abstract

International students at colleges in the United States have typically been less prepared for natural hazards and incidents of mass violence when compared to their peers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many international students as well as students from unstable family situations remained in on-campus housing, while their peers returned to their family homes. This may have represented an added stressor for students who remained on campus. Additionally, Asian students likely experienced increased prejudice as a result of the pandemic. While it is clear that some populations are more vulnerable to pandemic-related mental health consequences, it is vital for researchers to better understand factors contributing to pandemic preparedness and psychological functioning with a predominantly international sample. This work is necessary to promote emergency preparedness and adaptive coping for the current pandemic and future large-scale emergencies.

This study examines factors that contributed to preparedness trajectories among quarantined university students from May 2020 to October 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in the southeastern region of the United States. Additionally, investigators sought to understand factors contributing to resilient versus distressed trajectories for international students, with attention paid to additive stressors from COVID-19 such as discrimination and financial strain. This project is interdisciplinary in that we are examining both mental health outcomes (resilience and distress) and pandemic preparedness (factors pertinent to disaster science and emergency management).

We conducted 14 waves of surveys sent approximately weekly, with results from the first eight waves reported here. By longitudinally surveying international students, we were able to prospectively examine how their distress, resilience, and preparedness changed over time. We also explored social support, meaning in life, and self-efficacy as predictors of resilience trajectories. Similarly, we explored self-efficacy, collective-efficacy, and threat perception as predictors of pandemic-prepared trajectories.

Psychological distress was predicted by within- and between-person meaning in life and between-person emotional social support. Within-person threat perception and within-person collective efficacy predicted prevention/preparedness behaviors.

This research contributes to the science of resilience during stressful experiences by identifying effective means of coping through meaning-making and social support. Through this study, we provide practical resources and recommendations for international students to build resilience and preparedness during a pandemic. Because most research on community-wide stressors is retrospective and cross-sectional, the time-series design of our study conducted during this stressful event allows us to clarify patterns that remain unclear in the disaster and trauma literature.

Introduction

This study examined factors contributing to resilient and symptomatic psychological trajectories, such as social support and meaning in life, among international university students quarantined in Lafayette County, Mississippi during the COVID-19 outbreak. The current study assessed the role of self-efficacy, collective efficacy, and threat perception for predicting pandemic-prepared trajectories. The current study collected weekly data as the pandemic unfolded from May 2020 to October 2020 to measure how resilient and preparedness trajectories evolve over time. As a secondary analysis, we compared the effects of secondary stressors from COVID-19 such as discrimination against Asians.

Literature Review

The natural hazard and pandemic literature has elucidated various external, psychological factors relevant to consider within the context of natural hazards. Relevant environmental factors include symptoms of COVID-19; indirect stressors from the virus such as prejudice against Asians (Jeung, 20201); and financial strain. Environmental factors impacting distress and resilience include financial strain (Huang et al., 20152) and severity of impact from a disaster (Boasso et al., 20153; Pietrzak et al., 20144).

Regarding psychological factors, perceived meaning in life and social support fluctuate as often as daily (Miao et al., 20175). However, these factors are typically studied cross-sectionally so these changes over time, especially during a chronic stressor like a pandemic, are an important gap in the literature (George & Park, 20166). It would be helpful to understand how these factors predict changes in resilience and psychological distress in populations vulnerable to COVID-19. When so many meaningful activities and forms of social support are limited during the pandemic, it is particularly important to gather data on ways COVID-19 survivors effectively engage in social support and meaning-making that promote resilience.

Disaster preparedness, an individual factor, also influences well-being prior to natural hazards (Gil-Rivas & Kilmer, 20167; Weber et al., 20198). Understanding different factors that promote or inhibit a symptomatic trajectory during a pandemic can facilitate an increased understanding of how distress and resilience processes unfold over time, and how different factors can influence these trajectories. Understanding covariates can also inform intervention and prevention efforts for vulnerable populations in addition to programs of research.

The current study addresses crucial gaps in the literature by gathering more accurate, contextual data through a time-series design representing the first six months of the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S. We aimed to (1) identify protective factors against distress during the pandemic, (2) clarify the ways meaning and social support bolster resilience during a pandemic, and (3) examine the roles of collective- and self-efficacy for increasing pandemic preparedness and prevention efforts.

It is important that research on this topic focus on those who face particular vulnerabilities due to the outbreak. Individuals with particularly limited social support and those facing additional stressors from the virus should be included in research on the COVID-19 outbreak. Most college students in the U.S. have been encouraged to return to their family homes for the duration of the spring semester, if not longer. International students comprised the majority of students at our and at other U.S. universities who remained on their college campus after classes went online in Spring 2020, for they were unable to travel home. International students, especially those from Asia, are at increased risk for experiencing prejudice and discrimination because the outbreak originated in China (Jeung, 2020). Domestic students who remained in on-campus housing were approved to remain due to stressors such as unstable family home environments, homelessness, or family members with health issues that put them at greater risk from the virus. Thus, college students remaining in campus housing faced many unique stressors indirectly because of the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, a previous study of disaster preparedness among students at this same institution (Tkachuck et al., 20189) found that international students were more concerned about disasters, but less prepared than other university students and perceived disasters to be less likely. Thus, there was a need for research identifying international students’ pandemic efficacy, preparedness, and resilience.

Research Design

Research Questions

- What demographic characteristics (i.e., extent of lockdown, having or not having COVID-19 symptoms, gender, socioeconomic status) contribute to symptomatic or psychologically–-resilient trajectories and pandemic preparedness during COVID-19?

- How do between- and within-person differences in meaning-making, social support, and self-efficacy contribute to psychological functioning during the pandemic?

- How do between- and within-person differences in threat perception, self-efficacy, and collective efficacy contribute to pandemic preparedness during COVID-19?

- As assessed qualitatively, how do international students and others confined to campus housing engage in social support and meaning-making during quarantine?

Study Site Description

This study took place at the University of Mississippi in Lafayette County, an area that has endured varying states of lockdown over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. After spring break (March 15, 2020), no confirmed cases were reported in the county; however, to mitigate risk all students with stable housing elsewhere had been instructed not to return to the campus (USAFacts, 202010). Participants in the study were the exception, as they were students permitted to remain in university housing due to an inability to return home. At the start of the study (May 1, 2020), the county had 89 identified COVID-19 cases (USAFacts, 2020). By the end of the study, many participants had relocated to housing elsewhere in Lafayette County. At the time that data collection ended (October 2020), travel bans remained in place and international students were not able to return to their home countries. As of October 1st, 2020, the county had identified a total of 2,228 COVID-19 cases (USAFacts, 2020) and the university had reported 757 cumulative cases (University of Mississippi, 202011). Travel bans have remained in place and international students are generally unable to return to their home countries.

Context for this study includes additive stressful events as well as local demographics of the town (Mississippi Secretary of State, 201812) and the student population (Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning, 202013), which is largely white with the largest ethnic/racial minority group being Black/African American. The most clearly delineated potential additive stressor during the course of this study was a policy proposed by the Trump administration of the U.S. federal government that would have required international students to return to their home countries if they were not enrolled in in-person classes (Jordan & Hartocollis, 202014). This policy was proposed on July 6, 2020 and was rescinded on July 14, 2020, an interval during which many international students’ home countries were still banning travel into the country (Jordan & Hartocollis, 2020). This meant that not only might the students be unable to continue their education, but it was unclear where they could go if they could not return home and could not reside in the U.S. Furthermore, during that aforementioned interval of time, the University of Mississippi had not yet determined whether Fall 2020 courses would be offered in-person, so international students could not be certain whether meeting the requirements of the bill would even be possible.

Data, Methods, and Procedures

Procedures

In order to involve participants in the study, the researchers contacted the Office of International Programs and Department of Housing at the University of Mississippi prior to finalizing the research methods. Staff at both offices declined to offer input regarding the survey content but made suggestions regarding the timing of distributing the first survey and subsequent surveys. At this time, the researchers also offered to share a report of the results with both offices and meet with them virtually once data collection was complete if they wanted more information on the study. Prior to data collection, the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Mississippi.

The study employed a prospective longitudinal design. The Office of International Programs at the University of Mississippi graciously included the study recruitment script in their monthly e-newsletter (see Appendix 1), which included the hyperlink for the baseline online survey consent information and subsequent questionnaire. Data were collected using the secure online survey platform Qualtrics. A researcher sent the participants the survey every seven days for eight weeks whether or not participants had completed the previous week’s survey. Participants were paid $5 per survey completion using their preferred method as indicated in the payment survey (cash by mail, check by mail, PayPal, or Venmo). The researchers emailed participants once they were paid to confirm payments were received. Each week, participants were informed to notify the researchers if they no longer wanted to participate and only one participant did so. After eight weeks, preliminary data were analyzed as described in the results below. At this time, due to difficulty recruiting more participants, the researchers decided to continue surveying the current participants for six more weeks, a modification approved by the University of Mississippi’s IRB. Thus, all data were collected between May 1, 2020 and October 12, 2020, and the data collected by August 28, 2020 are reported here as preliminary findings.

Measures

After completing informed consent online, participants were asked to respond to demographic questions including international student status, nationality, gender, financial strain, and others. Demographic questions were excluded from surveys at time two onward. The next questions were to provide unique, anonymous participant numbers that were used to match participant data across time points. After completing demographic questions, participants were asked the same questions each week using the following brief self-report questionnaires to assess the following topics:

- Perceived meaning in life as measured by the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ; Steger et al., 200615)

- Emotional and tangible social support as measured by the two-way social support scale (Shakespeare-Finch & Obst, 201116)

- Adaptive and maladaptive forms of coping as measured by the Brief Coping Inventory (B-COPE; (Carver, 199717)

- COVID-19-related self-efficacy measured by items adapted from several surveys in the PhenX Toolkit database of coronavirus questionnaires and protocols (RTI International, 202018)

- COVID-19-related threat perception, adapted from several surveys in the PhenX Toolkit database of coronavirus questionnaires and protocols (RTI International, 2020)

- COVID-19-related collective efficacy, adapted from the Community Collective Efficacy Scale (Carroll et al., 200519) so that the questions specifically referred to the COVID-19 pandemic

- COVID-19-related pandemic preparedness, based on guidelines of preparedness/prevention behaviors from the (Centers for Disease Control, 202020). These behaviors were categorized as social distancing (eight items), sanitation (four items), and other (six items, e.g., “Read or watched guidelines for what to do to prevent COVID-19”)

- Psychological distress. Traumatic stress was measured with the PTSD Check List for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 201321). Depression, anxiety, and panic symptoms were measured with the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 item version (DASS-21; (Lovibond & Lovibond, 199522).

- Whether they had experienced COVID-19 symptoms that week based on symptom screeners in the PhenX Toolkit database of coronavirus questionnaires and protocols (RTI International, 2020)

- Whether they have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and other questions pertinent to the severity of their experience.

- Whether they experienced any other stressors (e.g., racial discrimination exacerbated by the pandemic or death of a loved one). Discrimination was measured with the Brief Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire-Community Version (Brief PEDQ-CV; (Brondolo et al., 200523)

- Qualitative text-entry questions asking participants how they obtained social support and engaged in meaningful activities that week.

At the end of the survey, participants were redirected to a second survey to fill out identifying information in order to pay them. In this way, their responses to the main survey content could not be connected to their identifying payment information. At the end of the payment survey, participants were redirected to the Clinical Disaster Research Center’s web page of COVID-19 resources.

Sample Size and Participants

A total of 72 participants were in the study at baseline, with approximately 52 participants completing most or all of the 14 time points, for approximately 700 data points in total. At the time data collection began on May 1, 2020, only 187 students resided in university housing, nearly all international students, according to staff with the Department of Housing. Inclusion criteria for the study was that students were living in campus housing at the time data collection began. Nearly all participants who responded identified as international students (92.4%), with the remainder identifying as the spouse or partner of an international student. While the sample inclusion criteria were quite specific, the study of this uniquely vulnerable population lends to the novelty of our research compared to larger, broader ongoing studies of pandemic-related stress. Furthermore, by geographically limiting the current location of participants, the progression and severity of the pandemic over time at that location were controlled for.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are as follows. Slightly more than half (55.6%) of participants identified as male, 43.1 percent identified as female, one individual (1.4%) identified as non-binary, and no one selected the “Other”/text entry response. Nearly all participants identified as heterosexual (84.7%), and eleven as LGBTQIA identities (15.3%) that included gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, queer, and transgender. Socioeconomic status was measured by whether participants qualified for need-based financial aid and by their parents’ education level. About a third (31.9%) said they qualified for need-based financial aid, 40.3% said they did not, and 27.8% were unsure. Parents’ education was almost uniformly spread, with 15.3% saying their parents did not finish high school, 15.3% of parent(s) had a high school degree, 5.6% parent(s) had a two-year college degree, 34.7% of parent(s) had four-year college degree(s), 4.2% of parent(s) had some graduate school, and 25.0% of parent(s) had a graduate or professional degree.

To maintain anonymity of participants, especially given how identifiable this might be due to the small number of participants living in student housing at that time, their nation of origin was not asked. To protect participants’ anonymity but also address the research question about discrimination against Asians, participants were asked how they identified with broad race/ethnicity categories and then those who indicated “Asian” had a regional follow-up question. The majority (69.0%) identified as Asian, 14.1% as Black/African/African American, 8.5% as White/European/European American, 5.6% identified as Arab or Middle Eastern, and 2.8% as Hispanic/Latino/a/x. Of the Asian participants, 58.0% identified as South Asian (i.e., India, Pakistan), 28.0% as Southeast Asian (i.e., Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia), 12.0% as East Asian (i.e., China, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan), and 2.0% as Central Asian (i.e., Uzbekistan, Mongolia).

Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Ethical Considerations

To participate in reciprocity, the primary investigator offered to provide homemade masks free of charge for any students quarantined on campus in May 2020. To avoid coercion and ensure that students felt comfortable asking for masks without participating in the research, the offer for face masks was included in the e-newsletter as a separate entry from the survey recruitment. The researchers endeavored to promote reciprocity with the institutional stakeholders by soliciting their input on the survey content and following their recommendations on when and how to distribute the survey. At the time of this report, results are not finalized but the researchers still plan to disseminate the results to the Office of International Programs and Department of Student Housing and to discuss the study further with them, should these stakeholders be interested.

An ethical consideration during the course of this study was how the researchers should respond when the federal policy affecting international students was initiated in July 2020. The researchers ultimately determined that showing support for the students could confound the results, considering a focus of the study was social support. The researchers decided that instead, they would send thank-you notes to the participants once the study had concluded, which could then include reference to support and solidarity with the students during that potentially even more stressful event.

Dissemination of Findings

Findings from the study, including recommendations for meaning-making and social support within COVID-19 public health guidelines, will be disseminated to the university student community and international students specifically. Findings will be described in the same international e-newsletter through which recruitment took place. Any recommendations for the institution that are distinct from findings for a lay audience will be provided to staff at the Office of International Programs, Department of Student Housing, and the Incident Response Team-a group of university staff involved in responding to and preparing for campus emergencies. In the time since this study began, the student newspaper, university news, and other local sources of dissemination have requested information and interviews from the mentor of the PI’s and director of the Clinical-Disaster Research Center https://news.olemiss.edu/finding-meaning-and-resilience-six-months-into-the-pandemic/. In the spring, a member of our team will be giving a TEDx talk on resilience during the pandemic, based in part on this study’s findings. The research team plans to share key findings with these parties in the event that they want to disseminate the findings through their respective outlets. Lastly, key recommendations for coping will be added to the “COVID-19 responding and coping” page on the Clinical-Disaster Research Center’s website, https://cdrc.olemiss.edu/covid-19/responding-and-coping/. This link was provided in American Red Cross brochures distributed in communities across the U.S. for coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. In this way, recommendations for coping may be shared with international students, Asians/Asian Americans, and university students more broadly throughout the United States.

Preliminary Findings

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using R/RStudio software. Latent Growth Mixture Modeling (LGMM) was used for research question one to assess trajectories and preparedness. Optimal fit for our latent factor of psychological dysfunction (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress, and posttraumatic stress) was used to determine the number of classes adhering to relevant fit indices, including Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The best-fitting model was used to test for covariates for the first research question, which included exhibiting or not exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms, gender, and socioeconomic status. To test the second research question, we used multilevel modeling (MLM) to examine between and within-person predictors (meaning, social support, self-efficacy) of psychological dysfunction using the latent means that we constructed from depression, anxiety, stress, and posttraumatic stress. To test the third research question, we again used MLM to understand how between- and within-person fluctuations in threat perception, self-efficacy, and collective efficacy predict pandemic preparedness.

A priori power analysis

Sample size was estimated as a two-level MLM using the powerlmm package in R/RStudio. The intraclass correlation coefficient for participants was set to approximately .55 based on previous research by the authors (Pavlacic et al., 202024). Additionally, we estimated small slope heterogeneity and medium effect sizes for proposed predictors. Dropout was set to 30% using a Weibull function to appropriately model higher than normal dropout due to the current crisis. Power estimates indicated that approximately 81 participants would be necessary to achieve 80% power.

Qualitative Coding

Data analysis for research question 4 is ongoing, as coding for the qualitative measures takes more time. Thus, research question 4 is not included in the following results, discussion, and conclusions. Coding for the baseline responses will be conducted using the Constant Comparative Method (Glaser & Strauss, 200925) to generate categories with respect to the forms of meaning-making or social support described. For subsequent time points, two or more independent coders will code all qualitative responses according to the categories established, with the goal of interobserver agreement (IOA) above 90%. If IOA is above 90%, the discrepant responses will not be included in frequency computations or any subsequent secondary analysis. Should IOA be below 90%, a third independent coder will resolve discrepancies.

Results

Results for Research Question 1

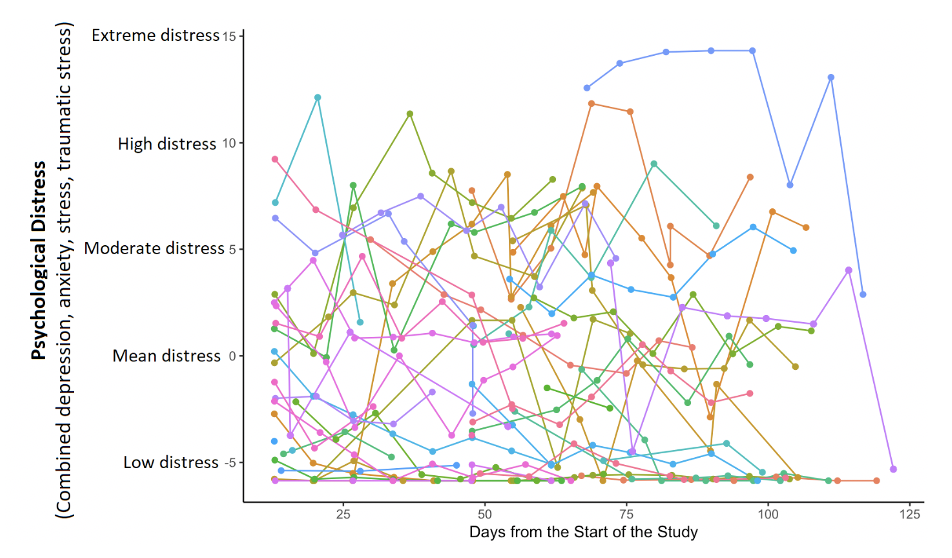

Latent Growth Mixture Modeling (LGMM) was used for research question one to assess trajectories and preparedness. Optimal fit for our latent factor of psychological dysfunction (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress, and posttraumatic stress) was used to determine the number of classes adhering to relevant fit indices, including Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). As can be seen in Figure 1, there is no clear pattern of distress over time for the participants overall. There was a great deal of variability, with the only pattern being that individuals with low distress from the start tended to maintain low distress throughout. Next, a general latent class mixed model fitted by maximum likelihood method was conducted to examine fixed effects of demographic variables (Table 1). None of the demographic variables included had a significant effect on psychological distress, so these were not included in the subsequent model for research question 2. Demographic predictors in the model were gender, socioeconomic status proxy variables (parents’ education level, qualification for need-based financial aid), and whether the individual had COVID-19 symptoms or a diagnosis.

Figure 1. Individual Trajectories of Psychological Distress Over Time for Each Participant

Table 1. Demographic Fixed Effects on Psychological Distress Over Time

| Coefficient (Wald) | p | |

| Intercept (not estimated) | 0 | |

| Time | 0 | > .05 |

| Gender female dummy code | 1.064 | > .05 |

| Gender non-binary dummy code | -0.284 | > .05 |

| Received need-based financial aid | -0.127 | > .05 |

| Parent had higher education | 0.022 | > .05 |

| Had COVID-19 diagnosis or symptoms | 0.189 | > .05 |

Results for Research Question 2

To test the second research question, we used multilevel modeling (MLM) to examine between and within-person predictors (meaning, social support, self-efficacy) of psychological dysfunction using the latent means that we constructed from depression, anxiety, stress, and posttraumatic stress scale scores. Data after eight time points (N = 49, observations = 383) showed weekly perceived meaning in life predicted between-person lower distress (totaled traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety; Table 2). Meaning also predicted within-person lower distress, i.e. distress was lower the weeks that meaning in life was higher. Emotional social support predicted lower between-person distress, with no within-person effects. Surprisingly, self-efficacy predicted greater within-person distress. With half the data collected, 27% of the fixed variance was accounted for.

Table 2. Multilevel Effects of Meaning in Life, Instrumental Social Support, and Emotional Support on Overall Psychological Distress

| Coefficient | SE | df | t | p | |

| Intercept | 15.611 | 3.956 | 330 | 3.947 | <.001 |

| Meaning between in-person | -0.229 | 0.104 | 44 | -2.202 | 0.033 |

| Meaning within-person | -0.104 | 0.043 | 330 | -2.413 | 0.016 |

| Instrumental support between-person | 0.164 | 0.155 | 44 | 1.056 | 0.297 |

| Instrumental support within-person | -0.018 | 0.055 | 330 | -0.331 | 0.741 |

| Emotional support between-person | -0.356 | 0.106 | 44 | -3.355 | 0.002 |

| Emotional support within-person | 0.039 | 0.035 | 330 | 1.124 | 0.262 |

| Self-efficacy between-person effects | -0.070 | 0.224 | 44 | -0.311 | 0.757 |

| Self-efficacy within-person effects | 0.328 | 0.065 | 330 | 5.016 | 0.000 |

Results for Research Question 3

To test the third research question, we again used MLM to understand how between- and within-person fluctuations in threat perception, self-efficacy, and collective efficacy predicted pandemic preparedness and prevention efforts (Table 3). Data after eight time points (N = 49, observations = 384) showed greater within-person perceived severity of COVID-19 predicted greater preparedness/prevention efforts. Greater within-person collective efficacy predicted greater preparedness/prevention efforts. Within-person effects of self-efficacy were not significant. Between-person effects were not significant for any predictor. With half the data collected, 15% of the fixed variance was accounted for.

Table 3. Multilevel Effects of Collective Efficacy, Self-Efficacy, and Perceived Severity of COVID-19 on Pandemic Prevention and Preparedness Behaviors

| Coefficient | SE | df | t | p | |

| Constant | 0.649 | 2.066 | 331 | 0.314 | 0.754 |

| Perceived severity between-person | 0.357 | 0.438 | 44 | -0.814 | 0.420 |

| Perceived severity within-person | 0.353 | 0.111 | 331 | -3.174 | 0.002 |

| Self-efficacy between-person | 0.204 | 0.159 | 44 | 1.285 | 0.206 |

| Self-efficacy within-person | -0.092 | 0.052 | 331 | -1.774 | 0.077 |

| Collective efficacy between-person | 0.122 | 0.097 | 44 | 1.263 | 0.213 |

| Collective efficacy within-person | 0.122 | 0.040 | 331 | 3.043 | 0.003 |

| Fear of the pandemic between-person | 0.035 | 0.073 | 44 | 0.486 | 0.629 |

| Fear of the pandemic within-person | -0.019 | 0.036 | 331 | -0.529 | 0.597 |

Additional Exploratory Analysis

We decided to run an additional analysis to explore the possible effects of the federal policy affecting international students (see “Study Site Description” above) on their psychological functioning. A linear mixed-effects model fit by maximum likelihood was conducted. The latent mean of psychological distress before and after the policy was enacted were compared (Table 4). Distress before and after the policy was enacted were not significantly different. Mean distress before the policy was M = 4.737, during the policy was M = 4.917, and after the policy was rescinded M = 4.880.

Table 4. Additional Exploratory Analysis of the Effects of the Temporary Federal Policy Affecting International Students (Jordan & Hartocollis, 2020) on Their Psychological Distress

| Coefficient | SE | df | t | p | Intercept | -0.848 | 0.731 | 333 | -1.159 | 0.247 | Time before policy | 0.459 | 0.438 | 333 | 1.048 | 0.295 | Time after policy | 0.572 | 0.626 | 333 | 0.914 | 0.362 |

Discussion of Preliminary Findings

Conclusions

Psychological resilience best characterized the pattern of psychological functioning over time; many ratings of distress fluctuated greatly from week to week, but many remained consistently low. Even as pandemic-related stressors grew, these individuals were steadily buoyant above the waves of hardships they faced, which is consistent with past studies of individuals responding to stressful or traumatic experiences (Galatzer-Levy et al., 201826).

Our finding of largely within-person, not between-person, effects of meaning in life on resilience and distress suggest that neither resilience nor perceived meaning during a pandemic is static or trait-like; they fluctuate. The between-person effects of meaning and emotional social support suggest that, even amidst these fluctuations in distress and resilience over time, individuals with an enduring sense of meaning in life and those with a stronger emotional support system experience less distress. This is even amidst the stressors from the pandemic, like COVID-19 symptoms, policy changes for international students, and fluctuation of positive cases in the area. It is never too late in the ongoing pandemic to enhance social support and meaning, even for individuals facing added stressors.

Accurate threat perception in combination with a strong sense of collective efficacy is vital for individuals to engage in greater COVID-19 preparedness and prevention efforts. These within-person effects suggest that changing a person’s threat perception and sense of self-efficacy is quite possible and effective. Our preliminary findings that collective efficacy outweighs self-efficacy fit with the prosocial aspect of COVID-19 prevention behaviors. Further, considering the added stressors the international students in our study faced, implications include that it is vital to provide stronger community support and to enhance their sense of community during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While our exploratory analysis on the psychological effects of the federal policy did not show significant results, descriptive data did suggest a possible quadratic effect, in which distress will remain higher as reinstatement of such a policy remains possible.

Implications

Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic will likely set a precedent for future pandemics. Clarifying factors that contribute to psychological functioning and pandemic preparedness affords health and mental health professionals, emergency management practitioners, and policymakers the opportunity to improve the lives of understudied groups in later stages of the current pandemic and during future emergencies.

Implications of our preliminary findings include that emotional support can be and should be emphasized in our interactions with others during the pandemic, as health professionals as well as in personal relationships. Health professionals providing care and services to individuals during the pandemic should assess for and/or consider additional stressors like deportation risk, discrimination against Asians, and financial strain and respond to these stressors by enhancing the individual’s emotional support system and aiding the individual in fostering a stronger, more enduring sense of meaning in life.

Public health implications include that accurate threat perception, not fear of the pandemic, should be highlighted in efforts to improve adherence to COVID-19 best practice guidelines for preparedness and prevention. While self-efficacy has been linked to disaster preparedness in the past, it appears that collective efficacy may be more important for the current pandemic. Two potential reasons for this increased importance of collective efficacy are that pandemic prevention behaviors explicitly involve the whole community sharing in the responsibility and efforts to maintain social distancing. Compared to other preparedness behaviors to which self-efficacy has been linked (e.g., preparing a first-aid kit, learning the location to go in a tornado warning; (Weber et al., 201827), social distancing and mask-wearing involve mutual prevention efforts to aid each other, not just to prevent harm to oneself. A second potential explanation for the primacy of collective efficacy in our study may be the diversity of our international sample. While the topic is understudied, some research suggests that collective efficacy may be more important than self-efficacy to change an individual’s behaviors in collectivist cultures (Alavi & McCormick, 201828; (Khong et al., 201729). Thus, the predominantly Asian demographics of our sample, as well as the collective responsibility component of social distancing behaviors, may explain the importance of instilling collective efficacy to increase engagement in pandemic prevention.

Limitations and Strengths

Some limitations of the current findings, mainly the potentially underpowered analysis of the psychological effects of the federal policy, may be resolved when data collection is complete. Similarly, with increased power, additional effects that were not significant for the current data may be uncovered. Less-easily addressed limitations of the study include the potential confounding variables in stress as students gradually shifted to off-campus housing over the course of the study. Although fewer participants were recruited than anticipated, the study will likely not be underpowered. This is because a priori power analysis was conducted, anticipating a 30% attrition rate for 80 participants, which would result in as few as 56 participants by the final waves. Our study included 52 individuals, all of whom completed nearly every wave.

Future Research Directions

In order to expand on and continue this line of research, we are applying for additional grant funding to track our participants as the pandemic continues and evolves. If additional funding is secured, we will expand the study to recruit more participants and address additional research questions. Potential future research questions include clarifying how each additional stressor (e.g., potential deportation, discrimination) affects psychological distress and resilience beyond directly pandemic-related stress. Once we have analyzed our qualitative data, we would like to further the research on the themes and categories that emerge regarding ways individuals make meaning and find social support during various COVID-19 restrictions. We hope to develop a scale on meaning-making and social support that could be utilized throughout the current pandemic or with individuals facing social isolation for other reasons. Another next step in the research would be to clarify the reason for the importance of collective efficacy for preparedness and prevention in our current sample: the collective nature of prevention efforts, and/or the collectivist culture of the sample? Empirical research with non-international students could elucidate this. Alternatively, considering the current proliferation of research related to the COVID-19 pandemic, a systematic review may be warranted to examine the respective roles of self- and collective efficacy.

References

-

Jeung, R. (2020, March 25). Incidents of Coronavirus Discrimination. Report for the Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council and Chinese for Affirmative Action. Retrieved March 30, 2020, from http://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/A3PCON_Public_Weekly_Report_3.pdf ↩

-

Huang, Y., Wong, H., & Tan, N. T. (2015). Associations between economic loss, financial strain and the psychological status of Wenchuan earthquake survivors. Disasters, 39(4), 795-810. ↩

-

Boasso, A., Overstreet, S., & Ruscher, J. B.(2015). Community disasters and shared trauma: Implications of listening to co-survivor narratives. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 20(5), 397-409. ↩

-

Pietrzak, R. H., Feder, A., Singh, R., Schechter, C. B., Bromet, E. J., Katz, C. L., Reissman, D. B., Ozbay, F., Sharma, V., Crane, M., Harrison, D., Herbert, R., Levin, S. M., Luft, B. J., Moline, J. M., Stellman, J. M., Udasin, I. G., Landrigan, P. G., Southwick, S. M. (2014). Trajectories of PTSD risk and resilience in World Trade Center responders: an 8-year prospective cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 44(1), 205-219. ↩

-

Miao, M., Zheng, L., & Gan, Y. (2017). Meaning in life promotes proactive coping via positive affect: A daily diary study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(6), 1683-1696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9791-4 ↩

-

George, L. S., & Park, C. L. (2016). Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Review of General Psychology, 20(3), 205-220. ↩

-

Gil-Rivas, V., & Kilmer, R. P. (2016). Building community capacity and fostering disaster resilience. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72, 1318– 1332.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26990644/ ↩

-

Weber, M. C., Pavlacic, J. M., Gawlik, E. A., Schulenberg, S. E., & Buchanan, E. M. (2019). Modeling resilience, meaning in life, posttraumatic growth, and disaster preparedness with two samples of tornado survivors. Traumatology (online first). http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/trm0000210 ↩

-

Tkachuck, M. A., Schulenberg, S. E., & Lair, E. C. (2018). Natural disaster preparedness in college students: Implications for institutions of higher learning. Journal of American College Health, 66(4), 269-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1431897 ↩

-

USAFacts. (2020, October 24). US Coronavirus cases and deaths. https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/ ↩

-

University of Mississippi. (2020, October 23). Confirmed cases reported to UM. https://coronavirus.olemiss.edu/confirmed-cases-reported-to-um/ ↩

-

Mississippi Secretary of State. (2018). Demographics: Oxford, Mississippi, Lafayette County Economic Development. https://oxfordms.com/economic-development/county-info/demographics/ ↩

-

Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning. (2020). Fall 2019-2020 Enrollment: Oxford and Regional Campuses. https://irep.olemiss.edu/fall-2019-2020-enrollment/ ↩

-

Jordan, M., & Hartocollis, A. (2020, July 14). U.S. rescinds plan to strip visas from international students in online classes: The Trump administration said it would no longer require foreign students to attend in-person classes during the coronavirus pandemic in order to remain in the country. The New York Times, Section A, p. 1. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/14/us/coronavirus-international-foreign-student-visas.html ↩

-

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80-93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 ↩

-

Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Obst, P. L. (2011). The development of the 2-way social support scale: A measure of giving and receiving emotional and instrumental support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(5), 483-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.594124 ↩

-

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92-100. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401 ↩

-

RTI International. (2020). PhenX Toolkit: COVID-19 Protocols. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/covid19/ ↩

-

Carroll, J. M., Rosson, M. B., & Zhou, J. (2005, April). Collective efficacy as a measure of community. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1-10). https://doi.org/10.1145/1054972.1054974 ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control. (2020, March). Coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html ↩

-

Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov. ↩

-

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation. ↩

-

Brondolo, E., Kelly, K. P., Coakley, V., Gordon, T., Thompson, S., Levy, E., Cassells, A., Tobin, J. N., Sweeney, M., & Contrada, R. J. (2005). The Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation of a community version. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(2), 335-365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02124.x ↩

-

Pavlacic, J. M., Schulenberg, S. E., & Buchanan, E. M. (2020, November). Meaning, purpose, and experiential avoidance as predictors of valued behavior: A daily diary study. In S. C. Hayes & T. B. Kashdan, Discussant & Chair, New Research Directions at the Interface of Values and Psychopathology. Symposium presented at the 54th Annual Convention of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Philadelphia, PA. ↩

-

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2009). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (1st ed.). Transaction Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206 ↩

-

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Huang, S. H., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 41-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.008 ↩

-

Weber, M. C., Schulenberg, S. E., & Lair, E. C. (2018). University employees' preparedness for natural hazards and incidents of mass violence: An application of the extended parallel process model. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, 1082-1091. ↩

-

Alavi, S. B., & McCormick, J. (2018). Why do I think my team is capable? A study of some antecedents of team members’ personal collective efficacy beliefs. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1147-1162. ↩

-

Khong, J. Z., Liem, G. A. D., & Klassen, R. M. (2017). Task performance in small group settings: the role of group members’ self-efficacy and collective efficacy and group’s characteristics. Educational Psychology, 37(9), 1082-1105. ↩

Weber, M., Pavlacic, J., and Torres, V. (2020). Trajectories of International Student Psychological Functioning and Pandemic Preparedness During COVID-19 (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 313). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/trajectories-of-international-student-psychological-functioning-and-pandemic-preparedness-during-covid-19