Experiences of Diabetes During the COVID-19 Pandemic in New Mexico Colonias

Publication Date: 2022

Abstract

COVID-19 contributed to rapid social and economic upheaval that has not impacted all communities equally. Individuals with conditions like diabetes and who come from multiply marginalized backgrounds face a confluence of factors, including elevated food insecurity and mental distress, that increase risks to their overall health and well-being. This report examines experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and its relationship to mental distress, food insecurity, and other dimensions of Type 2 diabetes management among adult residents of rural communities and colonias in Doña Ana County, New Mexico. The project used a mixed-methods qualitative and quantitative approach to understand potential interactions among these factors. In a survey of 77 individuals with Type 2 diabetes, we found that relatively few participants had a harder time managing their diabetes during the pandemic: at the time of the survey, most participants reported that their perceived diabetes control and self-care was the same or better than before the pandemic. In qualitative interviews, participants told us about challenges in managing their diabetes, but also noted positive changes. In surveys, we found that distress, but not food insecurity, was predictive of poor perceived diabetes control. Interview respondents indicated that their distress also interacted with their dietary choices. These results demonstrate that the pandemic has presented both opportunities and challenges for people with diabetes in this community. These findings will be distributed to local health agencies as we continue our analysis of the full dataset.

Introduction and Literature Review

On March 23rd, 2020 New Mexico enacted a stay-at-home order to limit the spread of COVID-19 across the state (New Mexico Department of Health [NMDOH], n.d.-a1). Early action in New Mexico was critical given that the state has a high prevalence of multiple risk factors for severe COVID-19 outcomes, including diabetes prevalence in excess of 10% (NMDOH, n.d.-b2), smoking in excess of 17% (NMDOH, n.d.-c3), and a large population of individuals who are aged 65 years or older (United States Census Bureau [USCB], n.d.4). New Mexico is also predominantly populated by traditionally marginalized groups who are at elevated risk for health disparities. For example, in 2018 New Mexico ranked 49th in the nation based on percent of the population in poverty (18.8%), and over 60% of the population identify as a racial or ethnic minority (USCB, n.d.). The sub-population of particular interest in this study are residents of rural and colonia communities in Doña Ana County (DAC), New Mexico. As of December 8, 2021, 38,134 COVID-19 cases and 565 deaths were reported in DAC (NMDOH, n.d.-d5). Diabetes prevalence in the county was 12.3% in 2014-2017 (NMDOH, n.d.-e6), highlighting the potential emergence of a COVID-19/diabetes syndemic within this community. The term “syndemic” here refers to co-occurring biological/biological and biological/social conditions that interact to exacerbate poor health outcomes within a specific population and have overlapping root causes (Singer, 20097). Colonias are defined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as rural communities in the four states (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) that border Mexico and have limited access to basic services and infrastructure such as sewer systems, water, paved roads, safe housing, and public facilities (New Mexico Bureau of Business and Economic Research [NMBBER], n.d.-a8). DAC is home to 37 colonia communities with a total population of approximately 100,000, with 30% of residents living below the domestic poverty line (NMBBER, n.d.-b9). Due to these factors, COVID-19 response measures may be particularly difficult for this population to implement, and eventual effects of the disease among the colonias may be especially severe and long-lasting. Given that approximately 840,000 people live in colonias along the United States-Mexico border (Esquinca & Jaramillo, 201710), data on how individuals manage chronic conditions during the pandemic crisis will be applicable to understanding the emerging COVID-19/diabetes syndemic across a broad region of the U.S. southwest.

Food insecurity and mental health management are also of considerable concern in DAC’s rural/colonia areas. In 2016, approximately 28% of DAC’s residents lived in areas designated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as “food deserts”, with three-quarters of this group living in rural areas and/or colonias (Growing Food Connections, 201611). The USDA defines food deserts as “low-income census tracts with a substantial number or share of residents with low levels of access to retail outlets selling healthy and affordable foods…” (USDA, 2021, paragraph 312). Prevalence of food insecurity in DAC was 15.7% in 2018 and increased to 21.3% during the first year of the pandemic (Feeding America Action, 202113). Although commercial agriculture is common across DAC, this does not necessarily translate to ease of access to home-grown foods, especially given the county’s location on the edge of the Chihuahuan desert. A report on agriculture and food insecurity in DAC by Raj and Raja (201814) identified lack of water rights, adequate land, and labor as barriers to small-scale farming. The same report identified factors including language barriers among the Spanish-speaking population, immigration status, financial resources, and transportation as particular challenges for rural residents in overcoming food insecurity. In terms of mental health, data from the NM Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System indicated that in 2019, 17.3% of the adult population of DAC experienced sustained mental distress, slightly lower than the state overall (20%) (New Mexico’s Indicator-Based Information System, 201815)). Data from 2018 suggested a ratio of 340 patients to every one mental health provider in the county, and in a 2020 survey of DAC residents, over half of the participants reported issues with reaching providers, insurance/paying for services, overall lack of services, and living in rural/remote settings as primary care access barriers (Boren et al., 202016). Rural residence is thus a common theme regarding both risk for food insecurity and inadequate access to mental health care in DAC.

Diabetes, Mental Health, and Food Insecurity

Over 30 million people in the United States have diabetes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], n.d.17), a statistic of acute concern given that individuals with diabetes are at greater risk for complications and mortality associated with COVID-19 (Huang et al., 2020). Researchers including Singer (202018) have referred to this as an emerging “syndemic” given that each condition aggravates the other. Much current research is focused on understanding this dynamic and its potential pathways (Drucker et al., 202019; Ganesan et al., 202020; Holman et al., 202021; Huang et al., 202022), but an equally important question is how the social, political, and economic crises attributed to COVID-19 impact well-being in individuals with diabetes, irrespective of whether they ever contract COVID-19.

Research indicates that mental distress and food insecurity, both factors associated with poorer outcomes in diabetes, have increased as a result of the crisis (Balch, 202023; Panchal et al., 202024). While typically analyzed separately, there is also the potential for interactions that amplify the effects of these conditions beyond what would be expected due to either distress or food insecurity alone. For example, both food insecurity/poor diet quality (Shaheen et al., 202125) and distress (Ogbera & Adeyemi-Doro, 201126) have been associated with poor glycemic control, which is a major predictor of diabetes-related complications and mortality (Gaster & Hirsch, 199827). Distress has been investigated as a pathway between food insecurity and poor glycemic control before the pandemic (Walker et al., 201828), and it is also possible that situational distress and food insecurity may interact to produce poorer outcomes than either factor acting alone. The anticipated significance in understanding the interactions between diabetes, food insecurity, and mental distress is to provide novel targets for diabetes care and management during periods of crisis. If interactive relationships are found, such as food insecurity exacerbating mental distress, selecting food insecurity as a primary intervention target may also ameliorate distress and its impact on glycemic control. This is an important potential insight for health professionals in resource-poor communities.

Theoretical Framework: Syndemic Theory

We apply syndemic theory to explore potential interactions between diabetes, mental distress, food insecurity, and social upheaval attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. Syndemic theory was introduced in the mid-1990s by medical anthropologist Merrill Singer as a model for studying the health impacts of concurrent and intertwined health problems; that is, a model for studying the “synergy of epidemics'' (Singer, 2009). This often involves collecting quantitative data from a broad sample of the research population as well as qualitative data—in particular, case studies—to elucidate connections, experiences, and interactions not conducive to quantitative analysis. In depth case studies, as opposed to other forms of qualitative data collection such as focus groups, allows for a focus on one individual’s nuanced experiences. The stories people are able to tell about their lives in the context of an interview provide additional support and help to elucidate the reasons for connections seen in quantitative data. More recently, the CDC further established the importance of viewing disease from a “syndemics perspective” by creating the Syndemic Prevention Network. The CDC initiatives have largely been applied to primary and secondary prevention of infectious diseases through a focus on biological, sociocultural, and structural relationships among diseases/conditions. Relevant here is work on intertwining cultural factors and HIV infection among Hispanics, which revealed interactions between substance abuse, intimate partner violence, HIV infection, and depression (CDC, 200929; Munoz-Laboy et al., 201830). Also relevant is the application of syndemic theory to understanding the diabetes-depression syndemic among Mexican immigrant women (Mendenhall et al., 201731).

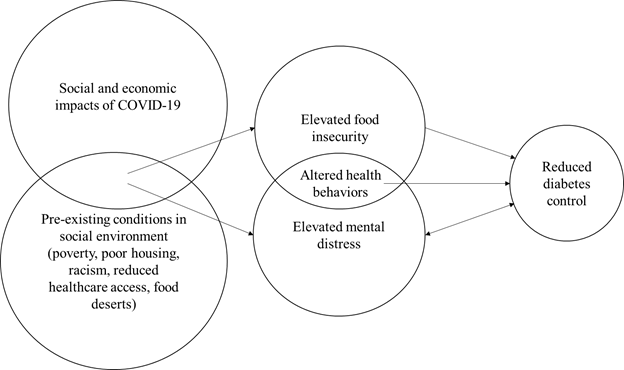

The syndemics perspective is differentiated from models that simply measure co-morbidity, as well as from the more general socioecological model, through integrating emphases on both disease/condition clustering and interaction (biological-biological and/or biological-social) (Gravlee, 202032; Mendehall et al., 2017). The primary contribution of syndemics models is that they often reveal biological-social-structural entanglements that are multiplicative rather than additive in terms of their impacts and provide insight into entry points where targeting one factor may ameliorate the effects of others (Gravlee, 2020). In regard to our sample, the significance is not that diabetes, food insecurity, and mental distress co-occur, but that within the pandemic environment among an already marginalized population, interactions between worsening food insecurity and mental distress may enhance risk for diabetes complications more than either factor would in isolation. These factors thus must be understood together, rather than separately, to effectively target programming for people with diabetes. Our proposed syndemic model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Proposed simplified syndemic model

Research Design

Research Questions

This report examines experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and its relationship to mental distress and food insecurity, as well as aspects of diabetes management and control (e.g.,medical care, diet, and physical activity) among individuals living with Type 2 diabetes in colonias in Doña Ana County, New Mexico. The long-term objective of this project is to develop a predictive model of how the COVID-19 pandemic contributes to outcomes in individuals with diabetes by exploring interactions among diabetes, mental distress, and food insecurity.

The primary research questions addressed in this report are:

- What is the impact of food insecurity and mental distress on diabetes management during the pandemic?

- How has the pandemic impacted health behaviors typically associated with diabetes management (i.e., engagement with health care, dietary patterns, and physical activity) in this population?

- How have individual experiences with diabetes management, distress, and food insecurity evolved over the course of the pandemic?

This report presents a preliminary analysis of data collected to address these questions in which we characterize the general experiences and perceptions of individuals with Type 2 diabetes in our sample and challenges they face in managing their diabetes. First, we define the sample of participants included in our data, then present our data collection and analytical framework. Next, we describe our sample demographic characteristics, general COVID-19 experiences, and diabetes histories. We follow this with our analyses of our participants’ experiences with access to care and treatment, perceptions of diabetes control and self-care, and the relationship of mental distress, food insecurity, and other sociobehavioral factors to dimensions of diabetes management. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of findings, their relevance to our syndemics model, and policy recommendations and future research directions based on our analyses and experiences conducting research among this population.

Sampling and Participants

Data were collected from adults living in or adjacent to colonias in DAC, New Mexico. Any adult (aged 18 years or older) who reported having either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes was included in the study; individuals with prediabetes, who were pregnant, or who had gestational diabetes were excluded, as their experiences are beyond the scope of our research. The analysis in this report includes responses from 77 participants who self-reported as having Type 2 diabetes. An additional nine participants who responded reported Type 1 diabetes, and two did not report diabetes type. These participants were not included in the 77 surveys used in the analyses presented in this report.

The study utilized a convenience sampling approach and recruited participants to complete an online (RedCap) or phone survey through social media advertisements; postcards sent to a random sample of addresses from an address sampling frame (obtained from Go Direct Marketing Services, El Paso, Texas); and through disseminating flyers at local food pantries. In August 2021, COVID-19 cases in DAC had reduced enough that community centers local to the colonias opened for activities. In collaboration with the DAC Department of Health and Human Services, we conducted in-person data collection events at five community centers within the community. We followed CDC-recommended COVID-19 safety protocols at all events (CDC, 202033). This included requiring mask wearing, providing hand sanitizer, wiping down tables, clipboards, and pens with disinfectant between individuals, and maintaining six feet of physical distance whenever possible.

We noted an important difference in the demographic profile of participants with Type 2 diabetes who responded to the survey flyers (n=22) and those who attended the community center events (n=55). A majority of the surveys submitted online or via mail were completed by English-speakers (86.4%), while the majority of the surveys submitted at the community centers were completed by Spanish-speakers (60.0%). In this population recruitment efforts demonstrably impacted the Type of responses that we received.

Ethics approval for the study was provided by the New Mexico State University Institutional Review Board before the study commenced (IRB #22565). All activities were conducted in collaboration with the DAC Department of Health and Human Services, which has a history of working closely with its population, and which manages the activities of local community health workers (CHWs). Participants who completed the online survey were asked to provide consent via a checkbox, while participants who completed the survey in-person signed a consent form before beginning study activities. Surveys and consent forms were available in both English and Spanish. The survey was translated by a native Spanish speaker who was an undergraduate research assistant on the team completing requirements for her involvement in the New Mexico State University Discovery Scholars Program

Survey

Surveys included questions on participant demographics (e.g., age, gender, education); diabetes history and experiences; diabetes self-management (Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure) (Toobert et al., 200034); food insecurity (USDA Food Security Survey) (USDA Economic Research Service [USDA-ERS], 2012a35); and mental distress (Kessler Psychological Distress 6-Item Scale) (Kessler et al., 200236). The instruments listed have all been developed for use in diverse and Spanish-speaking populations (Caro-Bautista et al., 201637; Millan et al., 200238; Terrez et al., 2011; USDA-ERS, 2012b39). Participants were also asked to evaluate changes in these dimensions via retrospective questions on overall perception of their diabetes control, self-care, health, and interference of diabetes in their day-to-day lives. The questions asked the participants to compare their recent perceptions to those from the period before the stay-at-home order was enacted (three options: is this experience BETTER, the SAME, or WORSE now than before March 2020/beginning of the pandemic). The diabetes self-management scale (Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure) is not analyzed here. Finally, participants were asked to complete a food frequency questionnaire and physical activity recall to assess dietary patterns and frequency of exercise.

Qualitative Interviews

Participants who agreed to be contacted for an interview during the initial survey were invited to complete a series of four qualitative interviews. All interviews were recorded after gaining a participant's permission and transcribed verbatim using machine transcription through the transcription feature in Microsoft Word/Microsoft 365. Transcripts were then reviewed with audio and corrected manually by a trained member of the research team. Generally, the interviewer conducted the transcription, but in some cases due to time constraints, co-PI Scott conducted transcriptions. First interviews occurred in November 2021. The first interview was a “grand tour” interview focused on a few open-ended questions to allow the participant to discuss ideas at the forefront of their minds regarding their experiences of diabetes. This allowed the researcher and participant to develop rapport and empowered the participant to guide the interview. Interview questions included broad questions such as “Can you tell me a little bit about how you learned that you had diabetes?” and “Can you tell me about any major changes in your life that have happened since your diagnosis with diabetes?” The first interview lasted, on average, 20 minutes.

The second interview is a follow-up that further explores participants’ understandings of the root causes of their diabetes, what happened in their bodies as they developed diabetes, and whether they perceive these causes and processes to be common in their communities. For example, follow up interviews explore the connections participants make among their environment, their behaviors, and the development of diabetes. Follow up interviews began on November 30, 2021, and are ongoing. We plan 2 additional follow up interviews at 1-month intervals with the goal of coproducing health-focused life histories with participants.

Thus far, we have enrolled nine participants in the interview series. Individual cases were selected based on diversity of experiences with diabetes control. This strategy was used to select a minimum of two participants who experienced better diabetes control, two who experienced no change in diabetes control, and two who experienced worse diabetes control. Each participant selected for a case study participated in interviews via Zoom or telephone, depending on participant preference.

Data Analysis

The preliminary quantitative analyses of survey data presented in this report were conducted using SPSS 26.0. Relationships between categorical variables were assessed using Chi Square and Fisher’s Exact tests. Differences in means were calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was assessed at p<0.05. Preliminary qualitative analysis of interviews included inductive line-by-line coding conducted by three research team members followed by preliminary organization of codes by PI Scott into broader analytic themes in NVivo to identify themes of change, such as changes in diabetes management. Qualitative data analysis is ongoing. Next steps include a review and revision of analytic themes with the research team and a second round of coding which will include an analysis of consistency in coding across team members prior to finalizing the theme set. Once the second round of coding is complete, the themes will be organized into a syndemic model using the principles of grounded theory- a qualitative analysis framework to develop models that emerge inductively from participant data.

Preliminary Findings

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents a breakdown of the sample demographics and COVID-19 related characteristics by gender. No participants reported nonbinary/third gender. Mean age of the survey sample was 61.73 ± 13.45 years, ranged from 19 to 87, and did not vary significantly between men and women (p=0.819). The majority of the sample reported place of birth in Mexico (60.5%) and 88.3% self-identified as Hispanic/Latinx. Almost half (48.7%) of the sample reported finishing high school, and 61.8% were married. Significantly more men (80.0%) reported being married than women (52.9%) (p=0.023). At the time of the survey, 9.6% had tested positive for COVID-19, and 92.1% had received at least one dose of an approved vaccine. Only 7.9% of the participants stated that they were not planning to eventually get vaccinated. Finally, significantly more women (78.4%) reported having at least one additional non-communicable chronic disease (e.g., hypertension) than men (56.0%) (p=0.043).

Table 1. Select Sample Demographic Characteristics and COVID-19-related Experiences

| Overall | Male | Female | P-Value | |

| n | 77 | 26 | 51 | |

| Mean Age ± SD | 61.73 ± 13.45 | 61.23 ± 16.79 | 61.98 ± 11.57 | 0.819 |

| Response Language Spanish | 38 (49.4%) | 12 (46.2%) | 26 (41.0%) | 0.689 |

| Born in Mexico | 46 (60.5%) | 13 (50.0%) | 33(66.0% | 0.176 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 68 (88.3%) | 20 (76.9%) | 48 (94.1%) | 0.054 |

| High School Graduate/GED | 37 (48.7%) | 12 (48.0%) | 25 (15.8%) | 0.933 |

| Married | 47 (61.8%) | 20 (80.0%) | 27 (52.9%) | 0.023 |

| Positive COVID-19 Test | 7 (9.6%) | 1 (4.0%) | 6 (12.5%) | 0.410 |

| At least one vaccine dose | 70 (92.1%) | 22 (88.0%) | 48 (94.1%) | 0.388 |

| No plans to vaccinate | 6 (7.9%) | 3 (12.0%) | 3 (5.9%) | 0.388 |

| Other NCDs | 54 (71.1%) | 14 (56.0%) | 40 (78.4%) | 0.043 |

Diabetes Histories

Duration of diabetes diagnosis ranged from 1 to 45 years. One-quarter of participants reported being on insulin, and 81.3% were prescribed pills (usually Metformin) to help manage their condition. From our qualitative interviews, the majority of our participants first learned that they had diabetes from a physician following abnormal lab results from a blood test. Many were worried about the diagnosis because they had family members or friends who had also been diagnosed with diabetes and were aware of challenges in management and potential complications. All mentioned diet, exercise, and medication as their main diabetes management activities. Several noted that it was their physicians who motivated them to make changes to improve their diabetes control.

Access to Care and Treatment

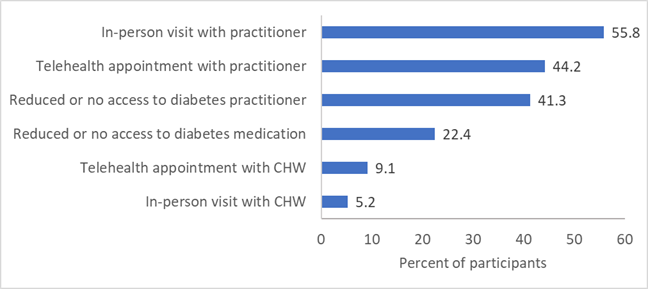

Figure 2 shows ways that participants were able to engage with their diabetes medical care in the period after March 2020. About one-fifth of the participants reported either reduced access or no access to diabetes medication during this time (22.4%), and 41.3% reported reduced or no access to their diabetes practitioner. Telehealth (44.2%) and in-person (55.8%) appointments with practitioners like doctors and physician assistants were more common than appointments with CHWs (9.1% and 5.2%, respectively).

Figure 2. Interactions with Health Professionals and Access to Medication in the Period After the Stay-at-Home Order was Announced

In contrast, from our qualitative interviews, most participants did not express any challenges in making doctor appointments or receiving their medication for diabetes. Most participants already received their medications through the mail or were able to use pharmacies with COVID-safe practices with which they felt comfortable. Many participants utilized telehealth during the pandemic and expressed comfort with those visits, although some stated a preference for in-person visits. No participants in the interviews stated that their health care suffered significantly due to the pandemic. The difference in survey and interview findings may result from the timing of the survey versus the interview. Since the interviews occurred later in the pandemic, it is possible that participants had greater access to medications during that time. It is also possible that those who agreed to participate in an interview were also more likely to have better access to medications and health care generally.

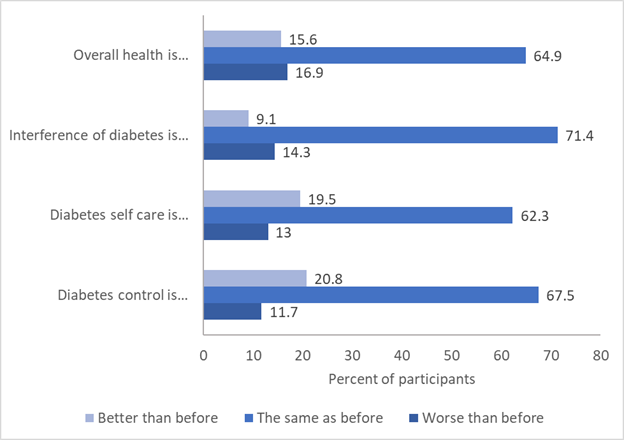

Perceived Diabetes Control, Self-Care, and Overall Health

Figure 3 reports participant self-assessment of diabetes control, care, day-to-day interference, and overall health. While a majority of participants reported that their assessment of these domains was the same as before the stay-at-home order began in March 2020, 11.7% said their diabetes control was worse than before and 13% said their self-care was worse than before. However, more participants reported improvements in their self-assessments; approximately 20% of the sample said that their control and/or self-care was better. In contrast to diabetes control and self-care perceptions, slightly more participants rated diabetes interference in their lives and their overall health as worse (16.9%) as opposed to better (15.6%) since March 2020 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Participants Reporting Changes in their Perceptions of Diabetes and Health in the Period After the Stay-at-Home Order was Announced

Mental Distress and Food Insecurity

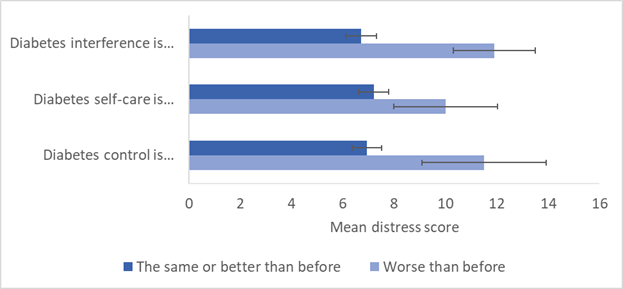

We examined mental distress and food insecurity as factors that might predict changes in perceived diabetes control and self-care (Figure 4). Mean distress score was significantly greater among those who rated their diabetes control as worse (mean = 11.50 ± 6.82) than among those who rated their control as the same or better (mean = 6.93 ± 4.97; p=0.021). Distress scores were also significantly greater among those who rated the interference of diabetes in their daily lives as worse than before (mean=11.90 ± 5.95 compared to 6.68 ± 5.04 (p=0.004). Differences in distress score between self-care groups was greater among those who rated their self-care as worse (mean=10.00 ± 6.82 compared to 7.22 ± 4.97), but this was not statistically significant (p=0.126). Distress score was also negatively correlated with perception of overall health score (r=-0.23, p=0.049). Food insecurity was not significantly different among groups in any analysis and was also not significantly associated with distress score (r=0.202, p=0.089).

Figure 4. Differences in Mean Distress Score by Perception of Diabetes Perceptions

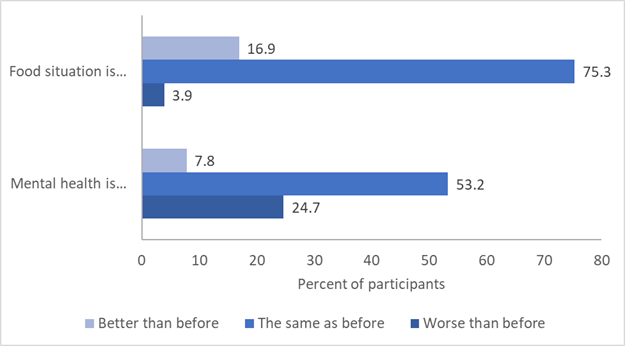

Participants reported changes in their mental health and food security situation (Figure 5). Many participants (28.8%) reported that their mental health was worse at the time of the survey, while 9.1% stated that their mental health had improved. In contrast, fewer participants (4.1%) reported that their food situation had worsened since the stay-at-home order was enacted, while 17.6% reported that their food situation had improved. Overall, these results suggest that our participants experienced greater detriments to their mental health over the period of the pandemic as compared to changes in their food situation.

Figure 5: Participants Reporting on Changes in Food Situation and Mental Health in the Period After the Stay-at-Home Order was Announced

Additional Sociobehavioral Factors Associated with Diabetes Control and Self-Care

In addition to mental distress and food insecurity, we examined other sociobehavioral factors commonly associated with diabetes management and outcomes, including physical activity and dietary patterns. In interviews, although many participants mentioned that managing diabetes was always challenging, they also discussed specific difficulties for diet and exercise during the pandemic. Many struggled to maintain their exercise routines. For example, one stated that while she previously enjoyed a water aerobics class, the pool where the class was offered closed during the pandemic and had yet to reopen at the time of our interview. Quantitative analysis supports the qualitative findings. Over one-quarter of the sample reported that they were less physically active (28.6%) at the time of the survey than before March 2020.

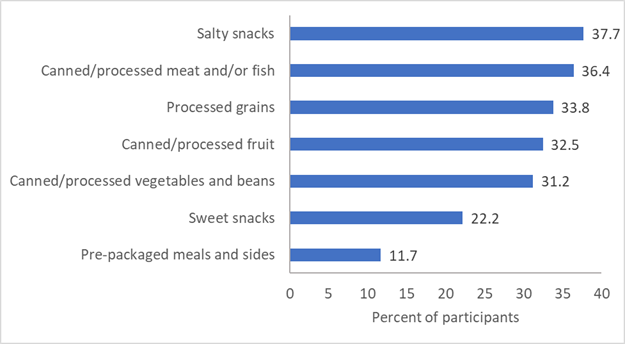

Maintaining a self-perceived healthy diet was also challenging for some. Several interview participants noted that their depression and anxiety had increased during the pandemic (as indicated by the quantitative data presented earlier), and they turned to food—particularly foods high in sugar and starch—to help alleviate some of the symptoms. Others indicated that they had more trouble getting fresh fruits and vegetables because of grocery store stock (not food security issues), limiting the number of trips to the grocery store, or having other people bring their groceries to them. In the surveys, participants reported more frequently consuming food products not advised in large quantities for people with Type 2 diabetes (Figure 6). Approximately one-third of the sample reported consuming more canned goods, more processed grains, and more salty snacks in the period since March 2020. Dietary and physical activity changes were not all negative, however, based on our qualitative data. For example, one participant received an increase in her food stamp allotment, which allowed her to purchase more healthy foods, particularly fresh fruits and vegetables. From the surveys, 26% of participants reported that they were consuming more home-grown foods. Others spent more time outside walking because this was one of the few activities they could do outside of the house in order to “get out of the house for a little while”. Of the survey respondents, 22.2% reported getting more physical activity after the stay-at-home order was announced than previously.

Figure 6. Participants Reporting Consuming More Processed Food in the Period After the Stay-at-Home Order was Announced

Conclusions

Summary of Preliminary Findings

Approximately 40% of our participants reported overall reduced access to their health care practitioners and diabetes medications, although participants in interviews have thus far not elaborated on these challenges. We also found a relatively low level of perceived poor diabetes control and self-care among our participants. In fact, more participants reported that their control/self-care was better than before the pandemic, which was supported in our qualitative analysis. While participants told us about new and additional challenges in managing their diabetes in the interviews, they also elaborated on positive changes, like being able to spend more time walking. We found that psychological distress was negatively associated with perceived diabetes control but did not find a relationship between diabetes control or self-care with food insecurity. Additionally, we found a pattern of behaviors and characteristics that were predictive of poorer diabetes control in other studies, such as elevated psychological distress, reduced physical activity, and increased consumption of processed foods (Indelicato et al., 201740; Aberg et al., 202041; Hamasaki, 201642). Participants in interviews also expressed concern over their ability to adequately meet their diet and exercise requirements.

The long-term objective of this project was to develop a syndemic model of how mental distress and food insecurity interact to negatively impact Type 2 diabetes outcomes among a multiply marginalized population during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we have not found evidence in this sample that food insecurity has played a major role in diabetes self-care/management, or that it has a relationship with mental distress. This does not support our initial proposed syndemics model. However, our preliminary results do suggest a relationship between mental distress and patterns of food consumption, as well as a relationship of both to perceptions of diabetes management and control, irrespective of food insecurity. We also found that distress was associated with perception that diabetes interference in day-to-day life had increased. It is difficult to say whether distress has impacted these perceptions, or whether these perceptions are driving elevated mental distress. What is most likely is that these factors are entangled in a cycle of cause and consequence. We will continue with our qualitative interviews and will target this relationship to further elaborate on interlaced dimensions of mental distress, dietary patterns, and diabetes control and self-care.

Applications of This Research

While data collection and analysis remain ongoing, there are several key immediate applications of this research. First, these data suggest that psychological health has played a role in how individuals perceive changes in their diabetes management during the pandemic in our sample. While it is not possible for us to draw conclusions about the direction of the relationship between distress and diabetes control (i.e., does distress contribute to poor control or vice versa), elevated distress has been associated with poor glycemic control in other studies (Indelicato et al., 2017). Evidence from our qualitative interviews suggest that participants are also eating starchy/sweet foods as a coping mechanism to deal with stress, consistent with other studies (Chao et al., 201843). Stress management as the pandemic continues should thus be a key target for diabetes education and health promotion programs.

Second, early on during the pandemic, people across the United States increased purchases of canned goods, prepackaged meals, and processed shelf-stable foods (Ellison et al., 202044). Evidence from this study shows that our participants with diabetes reported consuming these kinds of foods more often than they had previously. These foods tend to be higher in added sugars and refined carbohydrates, which contributes to poorer glycemic control (Aberg et al., 2020), and higher in sodium, which can exacerbate cardiovascular disease risk among persons with diabetes in particular (Provenzao et al., 201445). Diabetes programs and clinicians should work to develop avenues for individuals with diabetes to access fresh foods more regularly, especially when frequent visits to grocery stores may be impossible.

Finally, this research provides several lessons for conducting rapid research in populations that have been marginalized by historical and contemporary forces and may be hard to reach due to structural and sociocultural barriers. Early in the study, we were limited in our methods for data collection given the absence of opportunities for in-person events. As discussed in the methods section, the earliest data collection took place via online surveys advertised in mailings and flyers, and notably, most of our early respondents were English speakers who identified primarily as White/Caucasian. We were able to open data collection to in-person events at local community centers after vaccine administration began, and the majority of respondents at these events were Spanish speakers who identified primarily as Hispanic/Latinx. There were many early rapid assessments of the impacts of COVID-19 across diverse communities in the U.S. that concentrated on remote data collection methods (e.g., van Kessel et al., 202146). While the results of these surveys are very important, our study shows that these methods may miss groups who may be at greatest risk for the more severe impacts of the pandemic.

Limitations and Strengths

Limitations of the survey analysis include its small sample size (77 individuals with Type 2 diabetes), which limits the kinds of controls we can include in statistical models as we further evaluate this dataset. However, this is a hard-to-reach population, and we are satisfied with the overall response and engagement with the survey. We also relied on several retrospective questions regarding changes in experiences and behaviors from before March 2020, and participant recall may be faulty over this length of time. However, people with diabetes are likely to be more consciously engaged with managing their health, including their health behaviors and monitoring their blood sugar, on a day-to-day basis, which could positively impact recall over longer periods of time.

A major strength of this study is that we have integrated both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis techniques, which has allowed us to evaluate the impact of the pandemic across individuals, but also at greater depth than only quantitative data can allow. These methods can also allow us to validate findings from one method or the other convergently. An additional strength is that our study was developed in dialogue with local health councils and health workers, increasing the community value of the study findings.

Future Directions

The long-term objective of this project is to develop a syndemic model of how food insecurity and mental distress interact to impact diabetes control and outcomes in our participants. We have not found much evidence of a role for food insecurity, although there appear to be some interactions between distress and dietary choices based on our qualitative research. We have also found that the pandemic was not as detrimental to perceived diabetes control and self-care as expected, and factors that have favored resilience among people with diabetes during the crisis deserve more attention. The next steps are to fully analyze our dataset in conjunction with the results of our qualitative interviews, then to develop a model of how conditions during the pandemic have impacted diverse diabetes behaviors and outcomes in relation to elevated mental distress.

Acknowledgements. We thank Casa de Peregrinos, local community health workers, and the Dona Ana County Department of Health and Human Services for their assistance in recruiting survey participants. Additional funding for this project was provided by the American Philosophical Society.

References

-

New Mexico Department of Health. (n.d.-a.) Stay at Home-Essential Business. https://cv.nmhealth.org/stay-at-home-essential-businesses/ ↩

-

New Mexico Department of Health. (n.d.-b). Health Indicator Report of Diabetes (Diagnosed) Prevalence. https://ibis.health.state.nm.us/indicator/view/DiabPrevl.RacEth.NM_US.html#:~:text=Since%202011%2C%20the%20NM%20age,higher%20in%20older%20age%20groups ↩

-

New Mexico Department of Health. (n.d.-c) Fact Sheet Adult Cigarette Smoking. https://www.nmhealth.org/publication/view/help/3222/ ↩

-

United States Census Bureau. (n.d.) Quick Facts New Mexico. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM ↩

-

New Mexico Department of Health. (n.d.-d). COVID-19 Dashboard. New Mexico Department of Health. https://cvprovider.nmhealth.org/public-dashboard.html ↩

-

New Mexico Department of Health. (n.d.-e). Health Highlight Report for Doña Ana County. https://ibis.health.state.nm.us/community/highlight/report/geocnty/13.html ↩

-

Singer M. (2009). Introduction to syndemics: a systems approach to public and community health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009. ↩

-

New Mexico Bureau of Business and Economic Research. (n.d.-a). Colonias. New Mexico. https://bber.unm.edu/colonias ↩

-

New Mexico Bureau of Business and Economic Research. (n.d.-b.) Colonias Comparative Statistics. https://bber.unm.edu/colonias-comparative ↩

-

Esquinca, M., & Jaramillo, A. 2017. Colonias on the border struggle with decades-old water issues. The Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/2017/08/22/colonias-border-struggle-decades-old-water-issues/ ↩

-

Growing Food Connections. (2016, May). Dona Ana County, New Mexico. http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/05/GFC_COO_Profiles_Dona_Ana_County_20160606.pdf ↩

-

United States Department of Agriculture. (2021). Interactive Web Tool Maps Food Deserts, Provides Key Data. https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2011/05/03/interactive-web-tool-maps-food-deserts-provides-key-data#:~:text=In%20the%20Food%20Desert%20Locator,supermarket%20or%20large%20grocery%20store ↩

-

Feeding America Action. (2021). State-By-State Resource: The Impact of Coronavirus on Food Insecurity. https://feedingamericaaction.org/resources/state-by-state-resource-the-impact-of-coronavirus-on-food-insecurity/ ↩

-

Raj, S., & Raja, S. (2018). Agrarian Values and Urban Futures: Challenges and Opportunities for Agriculture and Food Security in Doña Ana County, New Mexico. In Exploring Stories of Opportunity. Edited by Samina Raja, 14 pages. Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project. ↩

-

New Mexico’s Indicator-Based Information System. (2018). Health Indicator Report of Mental Health - Adult Self-reported Mental Distress. https://ibis.health.state.nm.us/indicator/view/MentHlthAdult.Cnty.html ↩

-

Boren, R., Degardin, G., McNally, P. (2020). The State of the Behavioral and Mental Health System in Doña Ana County. SOAR: Southwest Outreach Academic Research Evaluation & Policy Center. https://alliance.nmsu.edu/files/2020/12/SOAR-Dona-Ana-Behavioral-Health-Assessment.pdf ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.) Diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/index.html. ↩

-

Singer M. (2020). Deadly Companions: COVID-19 and Diabetes in Mexico. Medical anthropology, 39(8), 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2020.1805742 ↩

-

Drucker, D.J. (2020). Coronavirus infections and Type 2 diabetes-shared pathways with therapeutic implications. Endocrine Society. https://covid-19.conacyt.mx/jspui/bitstream/1000/2521/1/1102039.pdf ↩

-

Ganesan, S. K., Venkatratnam, P., Mahendra, J., & Devarajan, N. (2020). Increased mortality of COVID-19 infected diabetes patients: role of furin proteases. International Journal of Obesity, 44(12), 2486–2488. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-00670-9 ↩

-

Holman, N., Knighton, P., Kar, P., O’Keefe, J., Curley, M., Weaver, A., Barron, E., Bakhai, C., Khunti, K., Wareham, N. J., Sattar, N., Young, B., & Valabhji, J. (2020). Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 8(10), 823–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(20)30271-0 ↩

-

Huang, I., Lim, M. A., & Pranata, R. (2020). Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia – A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(4), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018 ↩

-

Balch, B. (2020). 54 million people in America face food insecurity during the pandemic. It could have dire consequences for their health. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/54-million-people-america-face-food-insecurity-during-pandemic-it-could-have-dire-consequences-their ↩

-

Panchal, N., Kama, R., Orgera, K., Garfield, R. (2021). The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/#:~:text=A%20broad%20body%20of%20research,than%20among%20those%20not%20sheltering ↩

-

Shaheen, M., Kibe, L. W., & Schrode, K. M. (2021). Dietary quality, food security and glycemic control among adults with diabetes. Clinical nutrition ESPEN, 46, 336–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.09.735 ↩

-

Ogbera, A., & Adeyemi-Doro, A. 2011. Emotional distress is associated with poor self care in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Diabetes. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-0407.2011.00156.x ↩

-

Gaster, B., & Hirsch, I.B. (1998). The Effects of Improved Glycemic Control on Complications in Type 2 Diabetes. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(2), 134–140. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.2.134 ↩

-

Walker, R.J., Campbell, J.A. & Egede, L.E. (2019). Differential Impact of Food Insecurity, Distress, and Stress on Self-care Behaviors and Glycemic Control Using Path Analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34, 2779–2785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05427-3 ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Program Collaboration and Service Integration: An NCHHSTP White Paper. Enhancing the Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and Tuberculosis in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/programintegration/docs/207181-C_NCHHSTP_PCSI-WhitePaper-508c.pdf ↩

-

Muñoz-Laboy, M., Martinez, O., Levine, E. C., Mattera, B. T., & Isabel Fernandez, M. (2017). Syndemic Conditions Reinforcing Disparities in HIV and Other STIs in an Urban Sample of Behaviorally Bisexual Latino Men. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(2), 497–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0568-6 ↩

-

Mendenhall, E., Kohrt, B. A., Norris, S. A., Ndetei, D., & Prabhakaran, D. (2017). Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. The Lancet, 389(10072), 951–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30402-6 ↩

-

Gravlee, C. C. (2020). Systemic racism, chronic health inequities, and COVID ‐19: A syndemic in the making? American Journal of Human Biology, 32(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23482 ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Stop the Spread of Germs. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/stop-the-spread-of-germs.pdf ↩

-

Toobert, D. J., Hampson, S. E., & Glasgow, R. E. (2000). The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care, 23(7), 943–950. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.23.7.943 ↩

-

United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. (2012a). U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8282/short2012.pdf ↩

-

Kessler, R., Andrews, G., Colpe, L., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D., Normand, S. L., Walters, E., & Zaslavsky, A. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006074 ↩

-

Caro-Bautista, J., Morilla-Herrera, J.C., Villa-Estrada, F., Cuevas-Fernández-Gallego, M., Lupiáñez-Pérez, I., Morales-Asencio, J.M (2016). Spanish cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities measure (SDSCA) among persons with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atencion Primaria, 48, 458-467. ↩

-

Millán, M., Reviriego, J., & del Campo, J. (2002). Revaluación de la versión española del cuestionario Diabetes Quality of Life (EsDQOL). Endocrinología y Nutrición, 49(10), 322–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1575-0922(02)74482-3 ↩

-

United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. (2012b). U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module—Spanish: Three-Stage Design, with Screeners. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8285/hh2012spanish.pdf ↩

-

Indelicato, L., Dauriz, M., Santi, L., Bonora, F., Negri, C., Cacciatori, V., Targher, G., Trento, M., & Bonora, E. (2017). Psychological distress, self-efficacy and glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 27(4), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2017.01.006 ↩

-

ÅBerg, S., Mann, J., Neumann, S., Ross, A. B., & Reynolds, A. N. (2020). Whole-Grain Processing and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Diabetes Care, 43(8), 1717–1723. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-0263 ↩

-

Hamasaki, H. (2016). Daily physical activity and Type 2 diabetes: A review. World Journal of Diabetes, 7(12), 243. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v7.i12.243 ↩

-

Chao, A., Grilo, C. M., White, M. A., & Sinha, R. (2015). Food cravings mediate the relationship between chronic stress and body mass index.* Journal of Health Psychology, 20*(6), 721–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315573448 ↩

-

Ellison, B., McFadden B., Rickard, B.J., Wilson, N.L.W. 2020. Examining Food Purchase Behavior and Food Values During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43, 58-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13118 ↩

-

Provenzano, L. F., Stark, S., Steenkiste, A., Piraino, B., & Sevick, M. A. (2014). Dietary Sodium Intake in Type 2 Diabetes. Clinical diabetes: a publication of the American Diabetes Association, 32(3), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.32.3.106 ↩

-

van Kessel, P., Baronavski, C., Scheller, A., & Smith, A. (2021, March 5). In Their Own Words, Americans Describe the Struggles and Silver Linings of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/2021/03/05/in-their-own-words-americans-describe-the-struggles-and-silver-linings-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/ ↩

Olszowy, K.M., Scott, M.A., Mares, C., Taylor, H., Maranon-Laguna, A., Montoya, E., & Garcia, A. (2022). Experiences of Diabetes During the COVID-19 Pandemic in New Mexico Colonias (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 338). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/experiences-of-diabetes-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-new-mexico-colonias