Resilience Under Fire

Protective Action, Attitudes, and Behaviors Evidenced in the 2018 Woolsey Fire

Publication Date: 2019

Abstract

The attitudes and behaviors of those who choose to “stay and defend” properties during wildland fires are not well understood. Linking stay and defend attitudes and behaviors to well-established indicators of resilience advances practical understanding of how resilience takes root in a community. People who chose to stay and defend during the 2018 Woolsey Fire in Southern California were interviewed shortly after the fire to better understand the related attitudes and behaviors influencing the protective actions taken. Well-established resilience indicators provided themes to guide and evaluate the interviews, which revealed high levels of resilience at individual and community levels. Yet, actions on the part of institutions before, during, and after the fire largely worked counter to resilience building. This stay and defend inquiry fills a critical gap for more comprehensive future study. Next steps include a larger study linking protective actions and community governance with measures to reduce wildland fire risk.

Introduction

The community response to the Woolsey Fire demonstrates how local knowledge prevailed to manage extreme risk in a situation where professionally prepared organizations struggled. Local knowledge was influential to those who chose to “stay and defend” their homes and community instead of evacuating. Given the prevalence and success of those who stayed and defended their homes, the research questions explored were: What attitudes and behaviors related to resilience are evident in citizens who chose to stay and defend property during the Woolsey Fire? Further, are the individual indicators of resilience consistent with the community and institutional indicators of resilience?

“Stay and defend” describes the attitudes and behaviors of people who are willing to engage in assertive protective actions to save their homes and possibly other homes in their community in the event of a wildfire. The attitudes and behaviors of people who choose to stay and defend properties during this fire are important to understand as Malibu, and more broadly California, look to build more resilient communities.

The stay and defend research fills a critical gap for more comprehensive study. A larger comprehensive study is needed to integrate the convergence of factors in advancing fire policy and practice in California. Therefore, this ongoing study will link governance as assessed through stakeholder engagement, policy development, and design thinking with measures to reduce wildland fire risk (e.g., land use, vegetation management, and building practices).

The research used an important framework for resilience, which focuses on relevant factors at the individual, community, and institutional levels (Becker, 20111). Semi-structured interviews were conducted with those who were able to stay and defend properties during the Woolsey Fire, using prompts based on the established resilience framework. Analysis focused on identifying attitudes and behaviors among those who chose to stay and defend. Community and institutional factors were assessed through news reports, official reviews, and community meetings. The data collected provides a baseline for possible longitudinal studies in the area, as well as for studies of other major fires in the state.

The exploration contributes to a clearer understanding of how the Malibu community and other wildland-facing communities can better prepare for and protect themselves from fire and other hazards. At the same time, the Woolsey Fire reveals a multi-scalar breakdown of policy combinations across multiple levels. The investigation of the protective actions provides insight for a way forward in the management of escalating wildland urban interface (WUI) risk and highlights a need for a systems approach for realigning a wide range of policies and practices. A future inquiry will be needed to explore whether this action is framed within institutional policy and practice.

The 2018 Woolsey Fire

Coverage of the Woolsey fire has predominantly focused on its historic size and the wind speed; yet, the context of events in the hours before the fire broke out holds key information regarding the response. The Borderline Shooting took place in Thousand Oaks, California, one day before the fire and in an area near where the Woolsey Fire started. Around the same time, two other fires burned in California, the nearby Hill Fire, and the more distant Camp Fire, which became the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history. The compressed timeframe of these events shows a need for additional peak load resources to support and suppress fire.

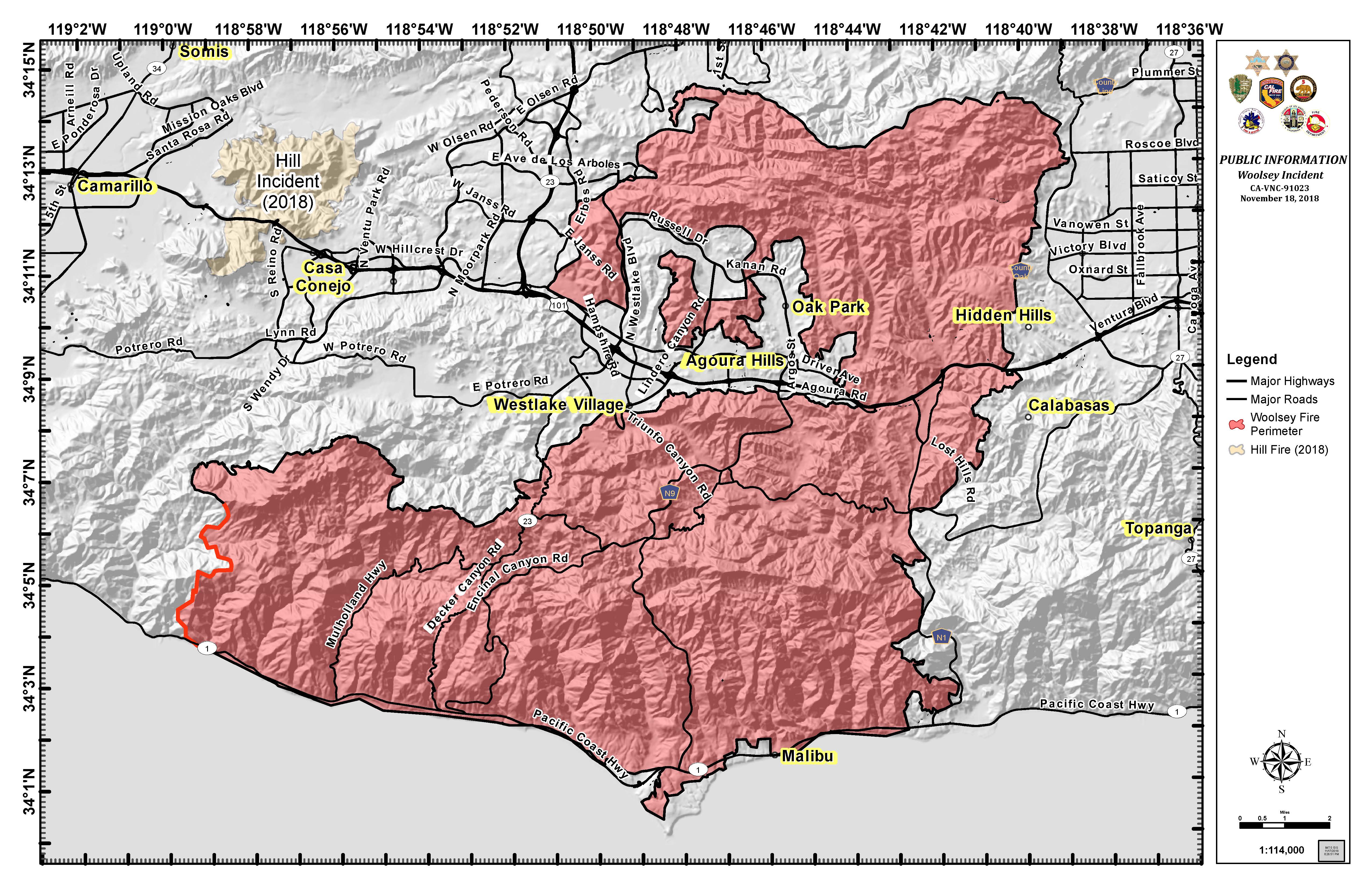

A vegetation fire broke out in the Woolsey Canyon north of Los Angeles on Thursday, November 8, 2018, at 2:24 p.m. The fire eventually consumed 96,949 acres of land (see Figure 1), destroyed more than 1,600 structures, prompted the evacuation of more than 295,000 citizens, and killed four people.

Figure 1. Woolsey Fire Perimeter.

The Woolsey Fire required the collaborative effort of hundreds of strike teams from across the nation. Fierce Santa Ana winds, often a factor in Southern California fires, pushed the fire to the south. The wind-driven fire raced through high fuel loads and steep terrain until it reached the town of Malibu. The fire service response is under review at the time of this writing. While examples of heroic action exist, questions remain around some aspects of the fire response. Preliminary assessment of the response to the fire has yielded the following:

- The evacuation of Malibu was late and hastily organized, resulting in thousands of cars stuck in fire-prone areas for up to six hours.

- Thousands of residents were not allowed to return to their homes for an extended time compared to previous return times after a fire, which resulted in extra stress.

- Normal emergency management functions were slow to engage compared to previous fires, both in Malibu and Los Angeles County.

- Operations were compromised when resources were heavily committed to the nearby Hill Fire. This allowed the Woolsey Fire to spread rapidly, jump the 101 Freeway, and rapidly move toward Malibu. Mutual aid resources were over-taxed, severely limited, and slow to arrive.

- After the fire, widespread citizen reports given at public meetings and in local news outlets evidenced that fire strike teams were unwilling to engage in areas where fire fighting was possible.

- After the fire, the discouragement of stay and defend measures by public officials were also evidenced in public meetings and local news outlets, although they were carried out anyway.

The attitudes and behaviors of those who chose to stay and defend are the focus of this study, as these attributes signal change in how assertive protective actions emerging from the community can combine with a range of other factors to improve fire management in the WUI.

Literature Review

A transdisciplinary approach was used to better understand the complex nature of the stay and defend research question. Resilience research, particularly concerning individual factors, was central to this exploration. Furthermore, a community resilience framework developed in New Zealand brings together much of the peer-reviewed literature. The framework highlights individual indicators: self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, critical awareness, and action coping (Becker et al., 2011). The framework further identifies community indicators and institutional signs: community participation and articulating problems and community empowerment and trust (Becker et al., 2011). Likewise, the fire literature from Australia undergirds the stay and defend portion of fire response efforts. The work of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission (VBRC) is authoritative and builds on a wide range of relevant peer-reviewed research (Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission, 2010)2.

Land use and vegetation management research is relevant to the context of future citizen protective actions, particularly as it relates to changes resulting from shifts in climate. Recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports and the Fourth National Climate Assessment inform present and future requirements for stay and defend and related policies (USGCRP, 20183).

Historical Relationship to Protective Actions

Stay and defend actions are deeply reflective of attitudes and behaviors rooted to the settlement of the American West. Remnants of these self-sufficient attitudes and behaviors are still evident in communities across the Western United State, even in cosmopolitan areas such as Malibu. Henry Lewis provides an account from 1848 about pioneers being caught on the Great Plains during a fire:

When the emigrants are surprised by a prairie fire, they mow down the grass on a patch of land large enough for the wagon, horses, etc., to stand on. They then pile up the grass and light it. The same wind which is sweeping the original fire toward them now drives the second fire away from them. Thus, although they are surrounded by a sea of flames, they are relatively safe. Where the grass is cut, the fire has no fuel and goes no further. In this way, experienced people may escape a terrible fate (Butler, 19744, p.1).

The use of fire tactics identified here includes backburning and establishing defensible space to create a survivable situation for people, animals, and property.

Past generations in the Malibu area reveal an acknowledgement that the area will largely be on its own during a fire, particularly in the critical early hours of the fire. Interviewees report that the fire service actively supported and helped train people to defend their properties through the mid-1980s. Stay and defend policies began to be established more fully. Additionally, a community-based volunteer fire force was established in Corral Canyon and supported to some degree by the fire service.

The Quadrennial Fire Review (QFR) provides a unified fire-management strategic vision for the five federal natural resource management agencies under the U.S. Departments of the Interior and Agriculture, together with other partners in the larger fire community. The 2009 QFR took a clear position on the future of stay and defend as part of a wider fire management strategy:

In order to reaffirm fire governance, the strategy requires building a “new” national intergovernmental wildfire policy framework… Indeed the logical extension of more fire-adapted ecosystems and more communities that require defensible space around fire-resilient structures built according to wildfire defense minded codes and ordinances is that homeowners should have an option to stay and defend their homes… The option would detail agency and public education efforts, require information and notification procedures, and summarize community preparation steps from building codes and property owner defense planning to resident education (National Wildfire Coordinating Group, p.245).

The stay and defend endorsement in late 2008 by the International Association of Fire Chiefs was a centerpiece of the 2009 QFR and was released one month before the catastrophic Australian Black Saturday bushfires in 2009. This endorsement was quickly abandoned after the Black Saturday fires. U.S. fire officials referenced the high death toll (173 fatalities) and quickly backed away from any endorsement of stay and defend policies.

However, an exhaustive year-long investigation into the Black Saturday fires was conducted by the VBRC in 2009 and found:

As a result of its inquiries the Commission concludes that the central tenets of the stay or go policy remain sound. The 7 February fires did, however, severely test the policy and exposed weaknesses in the way it was applied. Leaving early is still the safest option. Staying to defend a well-prepared, defendable home is also a sound choice in less severe fires, but there needs to be greater emphasis on important qualifications… The stay or go policy failed to allow for the variations in fire severity that can result from differing topography, fuel loads and weather conditions… The stay or go policy tended to assume that individuals had a fire plan and knew what to do when warned of a bushfire threat (p.5).

Notably, irrespective of the VBRC conclusions, Australian fire officials generally continue to discourage stay and defend practices. Reasons for discouraging stay and defend are not entirely clear, though a trend of shutting down assertive protective actions has been recorded. Thus, a de facto practice exists, based upon erroneous evidence, inappropriate for the scale of risk faced, and inconsistent with U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) policies, such as the Presidential Policy Directive 8 (PPD8) calling for a Whole of Community approach (White House, 20116).

Gender

The masculine attributes dominating firefighting and emergency management (Enarson, 19987; Tyler and Fairbrother, 20138; Reynolds and Tyler, 20189) have found their way into narratives surrounding stay and defend. Yet, these masculine narratives mischaracterize the work that, in reality, has more nurturing qualities. For example, defensible space preparations require the sensitivities of a gardener, as does extinguishing spot fires during a fire response. The challenges of recovery after a fire also require a nurturing characteristic. A willingness to nurture and adapt to natural systems is entailed in stay and defend work. Significantly, the data collected reveals that those who stayed to defend during the Woolsey Fire were well represented by females of all ages. A narrative that matches the nature of the effort is needed, as the masculine narrative does not align.

Fire Behavior

Fire behavior in forests and chaparral areas is still not adequately understood (Finney, 201510), particularly as fire interacts with structures at the WUI. Descriptions of this complex problem are beyond the scope of this report, but a short discussion on how fire tends to spread to structures is worthwhile.

Fire can spread by direct flame contact, convection, or through radiant heating, but short distances are required for this type of fire spread. More often in the WUI, fire spreads through the transport of embers, which can number in the hundreds of thousands and are capable of moving significant distances. Embers can lodge in flammable items surrounding a structure or find their way into unprotected openings. The resulting structure fire is often far more intense and can propagate to nearby structures.

Ember transport factors are essential in understanding the practice of stay and defend for two main reasons. First, defensible space and fire-safe building practices are used, thus minimizing risk. Second, recognizing that eliminating all fire risks is difficult and that ember-ignited fires will start small, stay and defend focuses on catching fires while they are small and manageable (Cohen, 200011).

Fire in the interface is the result of interrelated and interdependent factors, which can manifest as varied effects in different fires. Aligning local context actions for each factor to work together as a whole can significantly reduce WUI fire. Future wildfire adaptation requires focusing on the community functioning as a whole.

Resilience Building and Participatory Processes

Traditional approaches to managing risk were heavily focused on various levels of government. As the changing environment of disasters became clearer, a Whole of Community approach was called for in PPD 8. The “whole community” was defined by FEMA as:

…a means by which residents, emergency management practitioners, organizational and community leaders, and government officials can collectively assess and understand the needs of their respective communities and determine the best ways to organize and strengthen their assets, capacities, and interests. By doing so, a more effective path to societal security and resilience is built (FEMA, 2011, p.312).

Participatory processes are by no means a new concept, but the relationship to community resilience is important.

The coordinated focus of interactions needed involves solving for adaptation and system stability during a disaster response and recovery. Comfort (2009) states that coordinated action is possible when a hazard event is “perceived as the product of the interaction between groups of people and their environment” (p.3). Therefore, a coordinated adaptation of interactions between people and their environment can be evidence of community resilience.

Methodology

The research design for this quick response research is qualitative in both data gathering approaches and analytic strategies. A model put forth to build community resilience (Becker, 2011) was used to frame the understanding of the stay and defend action. Questions were based on the individual indicators identified in the framework and were developed to guide the semi-structured interview discussions. The interview questions shaped by the indicators of individual and community resilience are as follows:

Self-efficacy:

- What gave you confidence to take protective action?

- What prepared you for taking action?

Critical awareness:

- Was wildfire risk important to you before the Woolsey Fire?

- How would you describe your understanding of wildfire, at least as it concerns where you live?

- At what point before the fire did you start to consider the possibility of stay and defend?

Action coping:

- What factors contributed to your decision to stay?

- What measures did you take to manage the risk of staying?

- What actions did you take that made a positive difference?

Outcome expectancy:

- Did you expect that your action would lead to a better outcome?

- If so, how were you able to determine your actions would be successful?

Articulating problems:

- What action did you take in preparation that enabled an improved outcome?

- What additional preparations would have been helpful?

- Describe any challenges you faced, and the actions taken in response.

- Were you injured during this time?

Community participation and empowerment:

- Describe community connections you developed prior to the fire.

- Describe support you may have received from your community.

Inclusion criteria for participants specified an adult who took protective actions during the Woolsey Fire and stayed to defend property in some way.

Participants were identified through a Call for Participation flyer distributed at several post-fire town hall meetings. Additional participants were recruited from follow-on referrals. Fifty-two (n=52) semi-structured interviews were conducted in accordance with the protocol, with most being telephone conversations. The interviews were recorded with written consent given. The recorded interviews were then transcribed. Upon transcription, the recordings were deleted.

Thematic analysis of the transcripts was initially conducted manually for preliminary results. More in-depth analysis will be carried out using NVivo software to obtain more nuanced findings. As a comparison, indicators of wider community resilience are also being assessed qualitatively using news reports, community meeting transcripts, and official review reports.

Preliminary Results

The key community resilience indicators are used as the primary themes to frame the results discussion and is consistent with the guiding question structure. The preliminary findings from the data gathered are discussed below.

Self-Efficacy

High levels of self-efficacy were evident in the interviews among those who chose to stay and defend, without exception. The sense of self-efficacy is tied to a strong sense of place, as well as an understanding of the larger environment and the interaction that routinely occurs with fire in this locale. Also present were common themes of deep communing with nature during a time of crisis, prayer being a powerful and guiding force, and very specific direction on actions required. Importantly, this same self-efficacy was not necessarily correlated to success in other aspects of the interviewee’s lives.

Critical Awareness

The majority of interviewees articulated a good understanding of fire behavior and the effects of fuels, terrain, and weather. Some noted they had trained with fire departments or experts at the community level in the past. Most stated that they knew from experience that they would be on their own and should not expect help from the fire service. Notably, most self-identified as “Old Malibu”. Although what constitutes “Old Malibu” might be unclear, the phrase generally refers to a longer-term relationship and deeper connections with the people and place.

During the fire, awareness of the larger situational picture was a constant problem because communications were limited at best. Telecommunications were severed to most facilities due to the fire and destruction of the connections.

Action Coping

A wide range of pre-fire preparation levels existed. On the highly prepared end, some neighborhoods had well-developed fire protection systems, vehicles, water storage, pumps, fire hoses, and personal protective equipment in place and were practiced at employing them. In contrast, other neighborhoods had very little preparation, but were able to improvise with the materials on hand. One person saved their home using a case of bottled water to put out the spot fires and embers.

Regardless of the level of preparation, tests and equipment maintenance were lacking. As the fire approached, most people realized that prepared gear had not been checked on a regular basis. Equipment breakdowns or failures were an issue for most and fixing or replacing equipment was necessary.

Outcome Expectancy

Local knowledge was an asset for those who chose to engage in assertive protective action of their homes and community instead of evacuating. Everyone interviewed expected a positive result from the decision to stay and defend. Importantly, minor abrasions and burns aside, two people out of the n=52 stay and defend group were injured and required medical attention.

When asked why they should expect a positive result, all stated that experience had shown they could expect to be successful. The “Old Malibu” construct resurfaced here with ties to the land and even a multi-generational expectation that it is “just what you do when you live here.” In particular, those rescuing horses and other animals expected success in getting animals to safety and shelters.

Articulating Problems

Self-organizing networks were evident in various areas or neighborhoods. Networks were formed on the spot for specific functions to support stay and defend work. Small groups were able to move to hotspots in their neighborhoods and extinguish spot fires, thereby preventing the loss of houses. Feeding areas became communications hubs. High levels of competence were made available for emerging and specialized roles. Four distinct role types were evidenced in the stay and defend actions:

- Animal/livestock rescue

- Extinguishing spot fires and embers

- Logistics

- Communications

Self-organized communication volunteers further specialized to encompass specific functions: situational awareness, linking to outside the largely cut-off community, and creating gathering points for the community to synchronize their efforts.

Creative problem-solving occurred in a multitude of places. For example, one woman realized she could rig a makeshift network connection using a box of old cables and equipment found in a garage, thereby providing a communications route to the outside world for those in her neighborhood. An emergent boatlift of food and water supplies was supported with logistical receipt and distribution. Distribution areas quickly evolved to become feeding areas and communication hubs. Because cellular service was cut off, communications progressed from toy walkie talkies found in homes to more sophisticated systems that were cobbled together to give each working network a better operational picture.

Whether extinguishing spot fires on their own property or assisting in efforts in the community, interviewees describe nearly constant activity moving from one problem to the next. Intense levels of activity lasted several days in some locations. Improvisation was critical to success, as plans had to continually change as the fire situation evolved.

Community Participation and Empowerment

The community response to the Woolsey Fire demonstrated how local knowledge prevailed in managing fire risk in a situation where professionally prepared organizations struggled. No one reported being empowered by institutions to do this work; moreover, many were discouraged from engaging in protective action or actively blocked. Still, the community itself acknowledged the complexity of the situation and expressed extraordinary gratitude for efforts made on their behalf.

Commitment to the community was strong and showed evidence of an ability to work through a wide range of problems related to the fire. As expected of a well-established community, Malibu is home to accomplished and capable citizens. This level of capability is also evident in other communities around California that have experienced interface fires.

Trust

Trust is the essential foundational organizational element needed for any collective action. The low level of support without explanation during the Woolsey fire compounded the trauma of the fire for residents. The human element of the fire response was overlooked, perhaps because it was deemed a natural hazard.

The 2018 Woolsey Fire resulted in a concerning erosion of public trust in civic institutions. Additionally, when civic functions, such as police and fire, are ascribed to those who are not engaged in the community and do not know the local geography, they can become a significant disadvantage in adversity. Many respondents reported fire units on scene refusing to assist with firefighting. Similar problems were evident with law enforcement and local government. Some who stayed had to work around law enforcement roadblocks and uneven water access. Those who stayed to defend were characterized as reckless, putting first responders at risk, or even breaking the law. Critically, the words of one resident rang out: “They were not there!” Ignored requests for help were common themes. Reasons for the refusal to assist are presently unclear and several official inquiries are underway at the time of this writing.

A sense of betrayal by the institutions of local government, fire service, and law enforcement is deeply held by community members regardless of whether they stayed to defend or evacuated. Poor communication was demonstrated within institutional arrangements, as well as to residents. This has contributed to a bi-directional defensiveness. The erosion of confidence appears profound and the evidence points to declining trust.

Discussion

Our study showed that a gap existed between the services of the public sector and the needs of the private sector. Emergent volunteers filled this gap on an ad hoc basis. These volunteers filled gaps such as meeting the need for food, water, feeding operations, communications, animal rescue, and ember extinction following fires. The community response to the Woolsey Fire demonstrated how local knowledge fueled creative solutions to manage fire risk in a situation where professionally prepared organizations left them on their own.

The engagement and empowerment of all parts of the community is one of FEMA’s (FEMA, 201113) central principles toward resilience building (p. 4). Citizen participation was likened to spinach by Arnstein (1969), no one is against it in principle because it’s good for you. The key difference is between “going through the ritual of participation or giving real power to affect the outcome of the process” (Arnstein, 1969, p.21614). Whole of Community approaches seem to be wanted until people actually affect the outcome. Still, affecting the outcome is what is needed. Citizen engagement is vital.

The Woolsey Fire was an event with extraordinary attributes that helps us understand future scenarios. Many people made the decision to stay and defend homes and businesses. The fast-moving fire brought out the best in people. Even though homes were lost, many homes and animals were saved.

The demographics of those who stayed to defend in the Woolsey Fire dispel the common narrative of youthful masculine exploits. Such a gender biased message was not consistent with actual requirements of the tasks and skews the broader perception. The equal female presence in the Woolsey Fire is notable. Further, the composition of the people interviewed reflect the diversity, gender, age, and socio-economic status of most California communities. Therefore, shifting the narrative of those who stay and defend to a gardener storyline is much more appropriate, as they understand the ebbs and flows of nature in their locality.

Limitations

The inquiry was uniquely positioned to capture information about attitudes and actions taken by those who stayed to protect property in the 2018 Woolsey Fire. The dataset was a significant representation of those who stayed and defended (n=52), diverse and reflective of the community. The current limitation is that the preliminary analysis does not yet reflect the nuance and depth the dataset holds as keys to community resilience behaviors.

Next Steps

An important gap in knowledge has been filled by researching the 2018 Woolsey Fire stay and defend response by citizens. Deeper analysis of the complex nature of assertive protective actions is still required. An important next step in this research is to explore institutional-level resilience, particularly concerning how individual factors interact with institutional factors. This Quick Response Research study can also provide a baseline for possible longitudinal studies in the area, as well as for comparative studies of other major California fires.

The stay and defend research will fold into a second more comprehensive study around the convergence of factors in advancing fire policy and practice in California. This study will link governance with measures to reduce WUI fire risk. The exploration will contribute to a better understanding of how Malibu and other wildland-facing communities can better prepare for and defend themselves from fire and other hazards.

References

-

Becker, J. S., Johnston, D. M., Daly, M. C., Paton, D.M., Mamula-Seadon, L., Peterson, J., Hughes, M.E., and Williams, S., (2011). Building community resilience to Disasters: A practical guide for the emergency management sector. New Zealand: GNS Science Report. ↩

-

Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission, (2010). 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission: Interim report. Retrieved from the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission website: http://royalcommission.vic.gov.au/getdoc/208e8bcb-3927-41ec-8c23-2cdc86a7cec7/Interim-Report.html ↩

-

USGCRP, (2018). Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, Retrieved from: https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/downloads/ ↩

-

Butler, C.P. (1974). The urban/wildland fire interface. In: Proceedings of Western states Section/Combustion Institute papers, (Vol. 74, No. 15). Pullman, WA: Washington State University. ↩

-

National Wildfire Coordinating Group Executive Board (2009). Quadrennial Fire Review (QFR) Final Report. Retrieved from: https://www.nifc.gov/PUBLICATIONS/QFR/QFR2009Final.pdf ↩

-

White House, (2011). Presidential Policy Directive 8: National Preparedness. Washington, DC, Retrieved from Department of Homeland Security website: https://www.dhs.gov/presidential-policy-directive-8-national-preparedness ↩

-

Enarson, E. (1998), Through Women’s Eyes: A Gendered Research Agenda for Disaster Social Science. Disasters, 22: 157-173. ↩

-

Tyler, M. and Fairbrother, P. (2013). Gender, masculinity and bushfire: Australia in an international context. Australian Journal of Emergency Management Volume 28, No. 2, April 2013 ↩

-

Reynolds, B. and Tyler, M. (2018). Applying a Gendered Lens to the Stay and Defend or Leave Early Approach to Bushfire Safety. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77: 529-541. ↩

-

Finney, M., et.al. (2015). Role of buoyant flame dynamics in wildfire spread. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, August 11, 2015 112 (32) 9833-9838 ↩

-

Cohen, J. (2000). What is the Wildland Fire Threat to Homes? Thompson Memorial Lecture, School of Forestry, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ. April 10, 2000. ↩

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency, (2011). A Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management: Principles, Themes, and Pathways for Action. FDOC-104-008-1. Washington D.C.: Federal Emergency Management Agency. ↩

-

FEMA, (2011). A Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management: Principles, Themes, and Pathways for Action. FDOC-104-008-1. Washington D.C.: Federal Emergency Management Agency ↩

-

Arnstein, S. R., (1969). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association 35:4, 216-224. ↩

Jensen, S. J., Feldman-Jensen, S., & Woodworth, B. (2019). Resilience Under Fire: Protective Action, Attitudes, and Behaviors Evidenced in the 2018 Woolsey Fire (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 298). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/resilience-under-fire