Social Capital and the COVID-19 Pandemic

A Preliminary Qualitative Analysis

Publication Date: 2021

Abstract

This research investigates the relationship between social capital and adoption of safe nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPI), such as mask-wearing and avoiding public places during COVID-19 nearly one year into the pandemic. This report details preliminary findings from a follow-up study consisting of a survey of and interviews with individuals from Boston and New York City. The first wave study was conducted in May and June 2020. This second wave study was conducted in January and February of 2021. Findings from this second wave advance our understanding of the importance of social contexts on safe, hygienic, and socially conscious behaviors in the later months of the pandemic. The primary questions driving this study, and informing the preliminary findings reported here, include: (a) Does an individual's social capital influence their response to NPIs implemented during the pandemic? and (b) How has the pandemic itself influenced levels of social capital present in the communities we study? Our findings point to four themes among those we interviewed (N=64): (a) failure to form new social ties; (b) severing bonding ties over divergent behavior; (c) loss of bridging ties (e.g., with professional colleagues); and (d) virtual social fatigue. Future analysis will further explore these findings and triangulate them with our first wave results.

Introduction

In May and June of 2020, our research group launched a longitudinal panel study to investigate the role of social capital and resilience at different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This report documents preliminary survey and interview findings from our second-wave study, launched in January 2021. The study's participants are residents of New York City and Boston who were recruited on social media and by mail. This research aims to shed light on the role social capital plays in nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as quarantine and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specific questions addressed in this study include: (a) Does an individual's social capital influence their response to NPIs implemented during the pandemic? and (b) How has the pandemic itself influenced levels of social capital present in the communities we study?

Our preliminary findings point to four themes informing forthcoming analysis: (a) reduced likelihood of building new social capital; (b) severance of bonding social capital with individuals whose behavior during the pandemic diverged from that of the respondent; (c) loss of work-related, or bridging social capital due to job loss or the transition to "work from home"; and (d) virtual social fatigue. These themes inform further analysis of our second-wave data, as well as a forthcoming third-wave survey and interviews to be conducted in 2022.

Literature Review

Previous research on bonding, bridging, and linking social capital demonstrates that these three types of social capital function in different ways and can lead to varied outcomes. Bonding social ties can facilitate physical, emotional, and financial support during an event (Hurlbert et al., 20001), but they also have the potential to end at the water's edge: when individuals are displaced or face an overwhelming catastrophe, they may lose access to their spatially embedded bonding ties and resources (Elliott et al., 20102). Bridging ties reach across networks and, in some cases, span space, providing access to resources that would not otherwise be available in an individual's immediate network (Elliott et al., 2010; Hawkins & Maurer, 20103). Linking ties offer individuals access to information and resources from entities with power and authority (Szreter & Woolcock, 20044). Previous work has also demonstrated that communities with a combination of these ties have experienced better outcomes after a disaster, compared to communities, for example, with only bonding or linking ties (Aldrich, 2012; Aldrich, 20195). This study advances this literature in a two-wave study to understand the role of social ties and information on safe, healthy, and socially conscious behaviors of individuals in the early and later months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research Design

Research Questions

The primary questions driving this study, and informing the preliminary findings reported here, include:

Does an individual's social capital influence their response to NPIs implemented during the pandemic?

How has the pandemic itself influenced levels of social capital present in the communities we study?

In addition, data from this second wave study, alongside results from the first wave study, allow our team to examine multiple questions beyond those central to the preliminary findings presented here. These questions, delineated in Appendix A, will inform future analyses.

Study Site Description

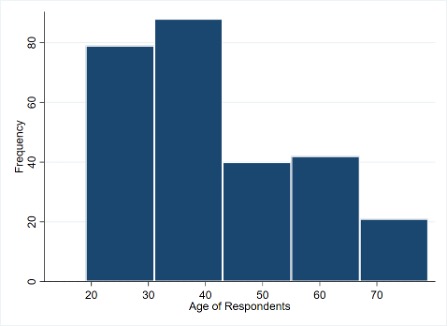

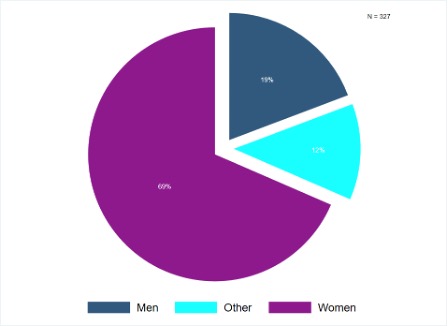

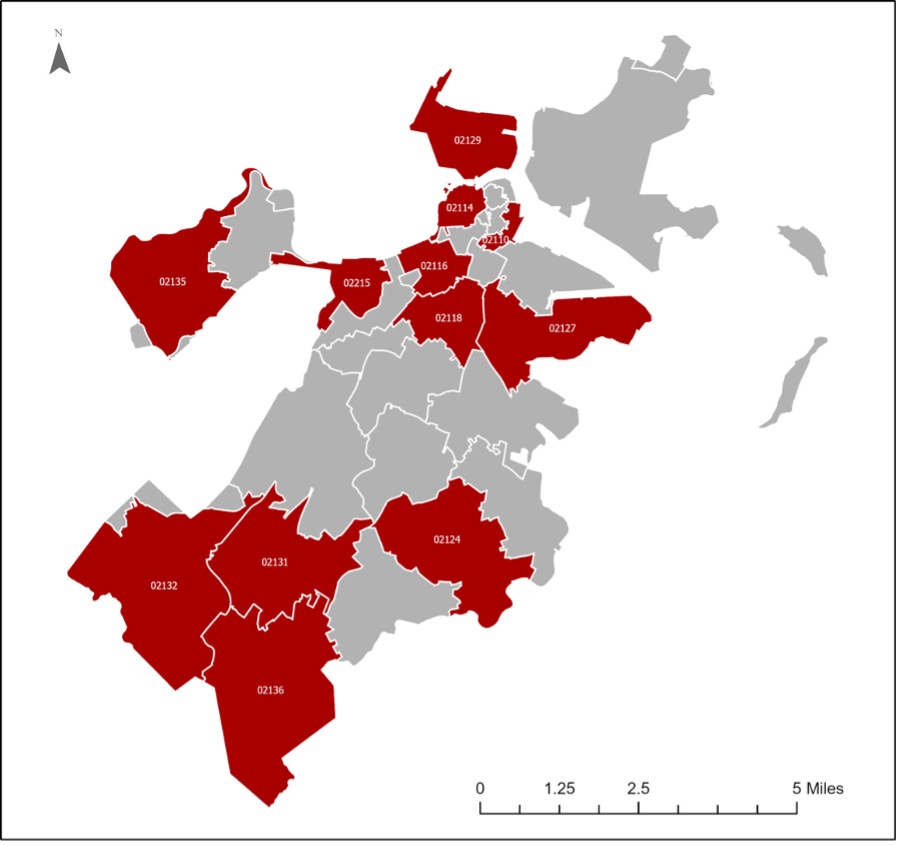

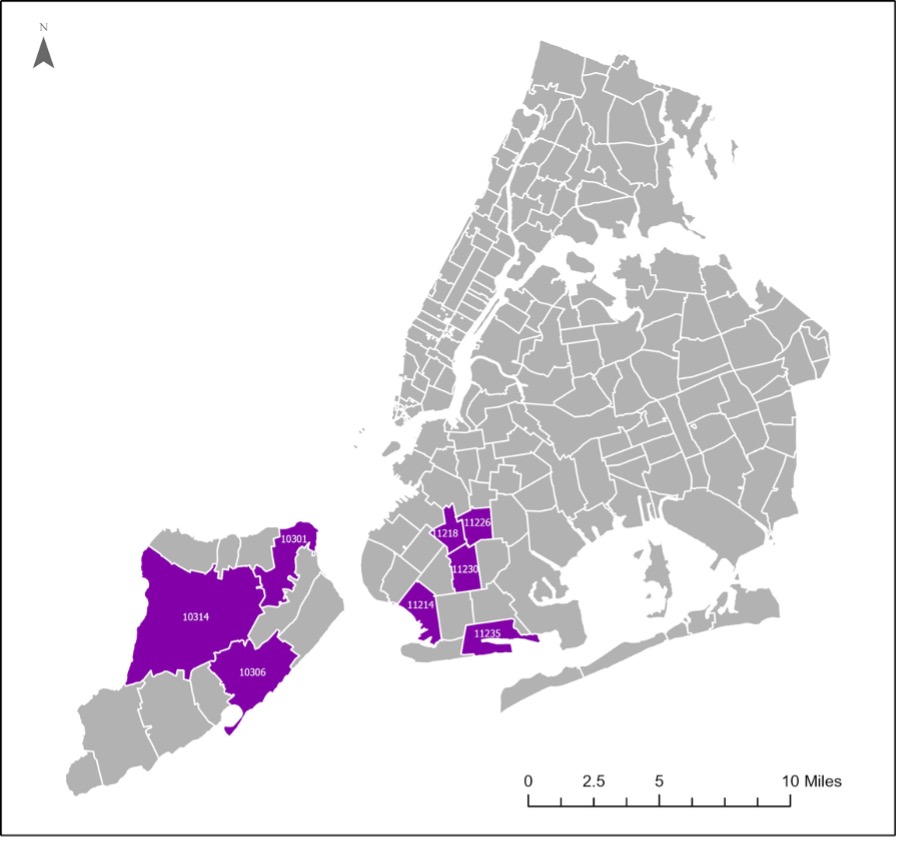

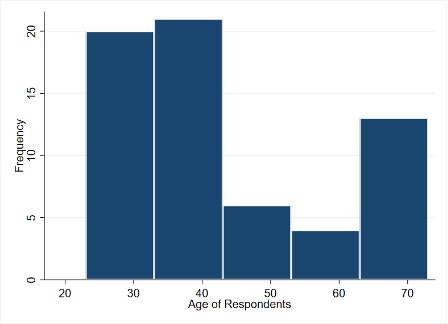

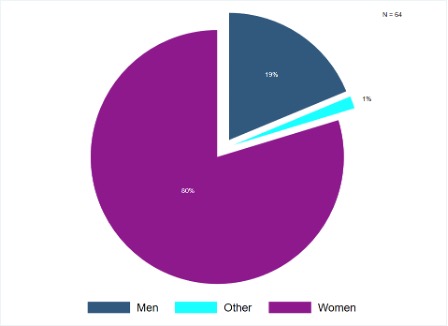

This study builds on the work of our previous study by focusing on the same six neighborhoods in Boston and New York City during May and June of 2020, (see Aldrich et al., 20206) for further information on site selection): West Roxbury, South Boston, and Brighton in Boston and Gravesend, Seagate-Coney Island, Grymes Hill-Clifton-Fox Hills in New York City. These neighborhoods represent a suburban demographic in which female, white, college-educated participants are disproportionately represented. While many political science studies aim for representative samples (D'Exelle, 20147), we intend this study to complement others looking at the reactions of varying demographic groups to NPIs implemented during COVID-19. In the context of public health risk communication in the United States, where mass public health education efforts are uncommon, this is especially relevant. Our study in particular targets a population infrequently targeted with public health messaging campaigns. See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for age, gender, and geographical distribution of our survey respondents.

Figure 1. Age and Gender Distribution of Survey Respondents

Age

Gender

Figure 2. Zip Codes from which 1+ Responses were Returned

Boston

New York City

Data, Methods, and Procedures

We are currently cleaning the survey data for further quantitative analysis. We have some preliminary findings of interest from our one-on-one interviews conducted with a subset of survey participants in the months of February and March 2021.

Data collected from the second panel includes both survey data collected in January 2021 (N = 327) and qualitative interview data from one-on-one Zoom interviews conducted in February and March 2021 (n = 64). Our preliminary analysis engages primarily with our qualitative data and findings. A semi-structured interview approach was the most suitable for our study because it allowed the generalization of results and provided participants the opportunity to elaborate on their responses. The interviews were conducted in follow-up with survey participants, and are meant to supplement quantitative findings. Our study followed a deductive approach guided by existing social capital and resiliency literature (Page-Tan et al., 20218). We prepared our interview questions with the goal of understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic influenced social ties and how social ties influenced NPI behavior during the pandemic. Based on the data we collected, we allowed themes to emerge based on the responses of individuals.

Interviews were conducted using the Zoom videoconferencing platform. They averaged forty-six minutes and were semi-structured with the guidance of twenty-six predetermined questions informed by relevant social capital and resiliency literature (see Appendix A). During the interviews, participants were asked about their resiliency with targeted questions regarding accessing COVID-19 information; personal challenges and behavioral changes; the 2020 election; the economy; and their community during the pandemic. The interviews were recorded with participant consent (see Appendix B) using Zoom recording capabilities and automatically uploaded to remote storage. Recording the interviews facilitated the use of a transcription software. The interviews were transcribed using AWS Transcribe automatic speech recognition and the 'tscribe' Python package. We identified the themes presented in this report through a thematic and content analysis of the transcribed interviews.

Sample Size and Participants

In our qualitative analysis, our interview participant pool (n = 64) is a subsample of the survey sample used for both the first- and second-wave studies. The second-wave study drew from the same participant pool of the first-wave study and offered compensation to complete the survey as well as an unpaid and voluntary opportunity to participate in a follow-up interview with someone from our team. Figure 3 displays the age and gender distribution of our interview participants. Eighty percent of our interview participants were women, with a mean age of 42.

Figure 3. Age and Gender Distribution of Interview Participants

Age

Gender

Data Analysis

Qualitative content analysis of the interview transcripts to date includes a systematic review for common empirical themes and development of a codebook incorporating these alongside theoretically-derived themes, to be used to code transcripts for further analysis. This process was conducted by a team of three PIs (CPT, DA, and SM) and six researchers (DH, ML, LP, PS, and two research assistants). This content analysis began with a review and cleaning of each transcript. A team member reviewed each transcript for accuracy by observing the recorded interview footage and comparing the transcripts produced by the transcription software. Cleaned transcripts were then transferred to a separate document to be uploaded to NVivo. During the review, our team corrected inaccuracies and noted common trends. This step helped our team identify recurring themes in the interview data, facilitating the development of empirically-driven codes. In addition to the codes derived from the data, the codebook (Appendix C) includes theory-driven, directional, and tonal codes. It was developed through several iterations of transcript review and team discussions. Our team is currently in the process of testing the codebook for inter-rater reliability using NVivo qualitative data analysis software. We will continue to refine it through this process before moving forward with coding interview transcripts for further analysis.

The codebook contains 44 data-driven codes clustered in one of five sections (interview sections, news and information sources, personal challenges, behavior change, and policy interventions/institutional factors). These codes were informed by empirical data gathered from content in the interview transcripts. There are also a total of four theory-driven codes under the sections "social capital" and "trust." Most of the theory-driven codes were drawn from themes in the literature. Social capital codes were split into bonding, linking, and bridging. Other theory-driven codes were informed by the content in the transcribed interviews such as trust and distrust. Lastly, there are two tonal codes and two directional codes. These codes will be used to indicate a negative or positive tone or an increase in the attribute. Interview data will be coded manually in NVivo. Codes will be assigned to data at the sentence level. Further analysis will draw on overlap in codes and patterns revealed by the coding process, validating or challenging the preliminary themes identified in this report.

Researcher Positionality, Reciprocity, and Other Ethical Considerations

During this ongoing pandemic, we face a number of ethical challenges, including ensuring that our data collection harms neither our investigators nor our informants. Further, many people may already be feeling stressed or anxious because of the loss of a loved one, the loss of a job, or the loss of normalcy. Our team received IRB approval for our first-wave survey and interviews (NEU IRB #: 20-04-31) and second-wave survey and interviews (ERAU IRB #: 21-064). Beyond institutional approval, our lab has extensive research experience working in a crisis environment. Our core approach requires that we do not put our subjects or ourselves at risk mentally or physically, and we will continue to use teleconferencing software to protect the health and safety of our participants and researchers. Further, our data collection does not collect names or other personally identifiable information and all of our data is stored on cloud-based, password-protected, two-factor authenticated servers.

Findings

Content analysis of interview transcripts revealed four common themes to be further investigated through systematic coding and triangulation with quantitative findings. These include: (a) reduced likelihood of building new social capital; (b) severance of bonding social capital with individuals whose behavior during the pandemic diverged from that of the respondent; (c) loss of work-related, or bridging social capital due to job loss or the transition to "work from home"; and (d) virtual social fatigue. Each is documented and discussed in the following sections.

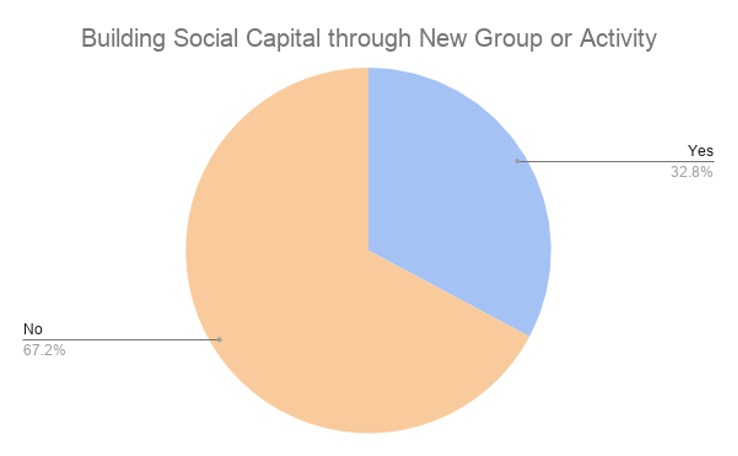

Theme 1: Failure to Form New Social Ties?

"Did you join any new groups since the outbreak of the pandemic?"

"No."

This is the most common answer we got through interviewing residents of Boston and New York City. Almost 70% of people said they did not make any new connections by joining any new groups since the COVID-19 outbreak (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percentage of Interview Participants who Reported Building New Connections

Additionally, some even stopped participating in the activities of the groups they joined before the pandemic. One participant stated:

One of the things my husband and I used to do that we obviously haven't been able to do since the pandemic, which I really loved, is that we love to sing. Um, and we were part of revels. Um, not the fancy revels that performs at [Theatre Name], you know, at Christmas time. But the, like, community-level revels...And we both really loved doing that. And, you know, that's been a real kind of hole in our lives. Um, so, you know, that's something I think I really missed. That's a group we belonged to, and we shared. So it was good for us as a couple, and it was good for us individually because, you know, he being a bass and me being a soprano, you know, we were in different sections of the chorus and, like, we each had our own friends within the chorus. Um, so we really missed that.

This interview participant quit the singing group passively because the group did not transition well to the virtual space. The group failed to provide an alternative way for people who are interested in this kind of activity to get together during the pandemic. However, other kinds of groups that successfully transitioned their meeting mode from face-to-face to virtual could not attract the same number of people as pre-pandemic. The reason behind this phenomenon is that people are tired and fatigued with virtual interactions. For instance, one interview participant who had previously taught fitness courses said, "I personally, like, absolutely hate Zoom fitness classes; like I just hate them."

Some social groups survived the COVID-19 interruption.Even though 67.2% of interview participants indicated they are not growing their social capital, some people consistently engaged in groups during the pandemic in order to access information, reduce stress, and receive emotional support. There are some groups that persevered and were able to transition to a virtual presence. Other groups emerged during the pandemic, such as book clubs, dog groups, cook groups, and others. Nearly 33% of our interview participants noted new groups and indicated that these groups emerged in an organic way. For instance, one work-from-home interview participant said:

One of my former co-workers started leading Friday night yoga every Friday at five. She's a yoga instructor. Uh, and she just reached out to a bunch of us and said, ‘hey, would you be interested in joining me for yoga?’ Like, not super planned, kind of casual, and, uh, so that was immensely helpful. I had never done yoga before.

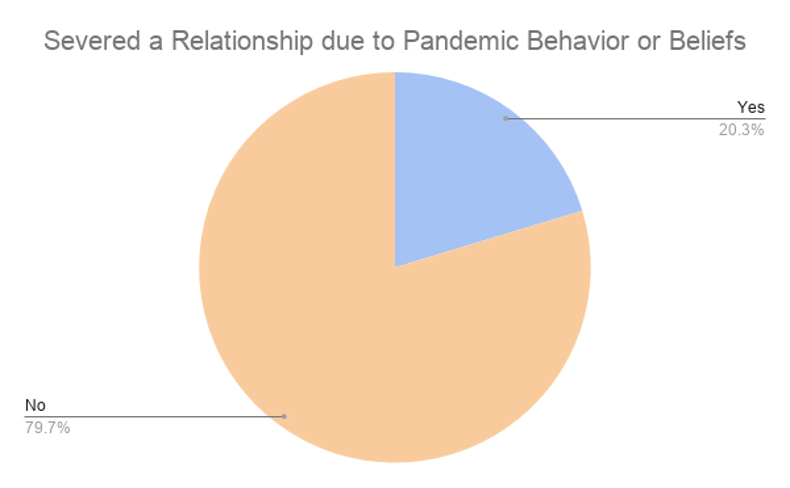

Theme 2: Severing Bonding Ties Over Divergent Behavior

Some of my friends I don't really respect how they've handled this. Um, just some of my friends who I always considered to be free spirits. But I thought when it came down to what they cared about, other people's health and safety, [they] have been traveling when they didn't necessarily need to have been visiting. Friends indoors have been visiting. Family members have been doing things that weren't necessarily safe and that I didn't agree with and then have been very flippant when I asked more questions about it and then have been encouraging me to do things like visit. And that sort of made me lose respect for them.

Friendship is categorized as bonding social capital, which describes intimate familial or friend connections (Adler & Kwon, 20029). Bonding social capital is valuable in times of need because these people can supply essential goods, information, and emotional support (Hurlbert et al., 2000). People with high levels of bonding capital have been shown to recover from disasters more quickly (Adler & Kwon, 2002). This underscores the significance of a common theme among our interview participants: cutting social ties during a time of need and isolation. Our interviews reveal three reasons for this: (a) physical distancing from friends leading to passive weakening of ties; (b) disparities in risk-aversion among friends resulting in loss of trust and respect; and (c) instances in which, due to growing lack of trust, one person took initiative to sever their relationship. These three reasons are discussed below.

First, some interview participants noted they have less opportunity for physical contact with friends or do not have enough flexible time to meet them even virtually. Zoom fatigue was often cited as a contributing factor. For instance, one interview participant expressed:

Yes. We got a couple of friends who not being able to see them. I really haven't had any interaction with them. I feel like at work a little bit more distant in part just because it's been so much, so wild and crazy with all the COVID stuff that people don't really have time to chat. Um, so that been impacted me a little bit.

Second, approximately one-fifth of interview participants stated that they emotionally distanced themselves from friends they did not feel treated the pandemic seriously (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Percentage of Interview Participants Who Reported Severing a Close Personal Relationship due to Pandemic-Related Behavior or Beliefs

A group of interview participants expressed that their friends who engage in irresponsible behavior during the pandemic, like eating out indoors and going to busy places, do not respect people and they do not care about other people's health. Thus, they feel they do not respect or trust this group of friends anymore, as one interview participant said:

The other piece of that is family or friends that I feel are making dangerous or irresponsible decisions. I respect them less, which I feel, like, creates a bit of a hole. Yeah. Um, eating out indoors, uh, going to busy places, um, continuing to be irresponsible. Um, traveling. I feel really...I feel very bitter about people who choose to travel, which will prolong this pandemic when I have not gotten to see my family and or friends in a year and a half.

Third, some severance in bonding social capital was a result of ideological disagreements. Some interview participants expressed a difference in ideas on how to manage risks compared to their friends and indicated they do not want to have the same relationship with those who are not on the same "wavelength" anymore. For example, an interview participant who works in a church expressed:

Um, I do have one friend who takes a little bit more risk than I would take. And sometimes I feel like, um, that our relationship isn't as close, now? I don't agree with her more and that we have a little more tension in the relationship. Um, because she will do things that I don't agree with, like, go eat in a restaurant or go to a bar or go to other places.

Theme 3: Loss of Bridging Social Capital

Professional ties or ties that span groups are often referred to as weak ties (Granovetter, 197310) or bridging social capital. Research shows the lack of social capital at work can have a negative effect on employees (Helliwell & Huang, 201011). One participant who works in higher education provided an extensive example of the impact that the loss of weak professional ties has had on her mental health:

Um, I worked an awful lot, and I loved the work that I did. I, um you know, I've spent 35 years in higher education, and, um, I believe so strongly in the mission of [Insert University], and, um, and the people that I worked with were a gift to me, and I miss that interaction in addition to that work was sort of the conduit for going, you know, like, um, you're sitting at your desk at work and your friend sends you an instant message and you connect to go meet somewhere after work. And when you are in all these different places, there's no more connection. There's no more easy ‘on the way, by on the way to the parking lot, let's just stop by and get a drink’ kind of thing. Um, so I missed that interaction, and, um and then in it in in a lot of ways, we've tried to make up for some of these missed connections. Um, so we've had video conferences and, you know, we've really tried, and I think we've been really successful, and we've done great things, but there's still a let down at the end of the [Professional Society] meeting, the most boring daylong meeting you can possibly attend. You know, you think about 200 you know, student financial services representatives in a room. But at the end of that meeting, we would all go somewhere together and have that social part of that group, and it's not the same. You just click close on your Zoom session and your meeting's over. So yeah, I think that that's probably one of the biggest places that we are all suffering.

Theme 4: Virtual Social Fatigue

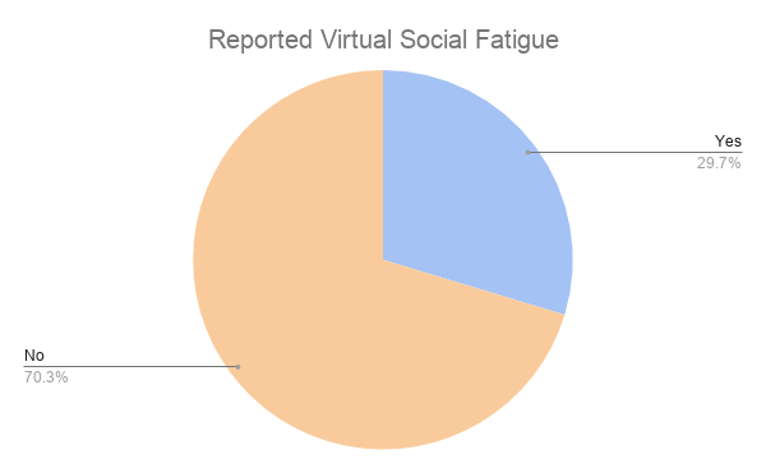

Many of the people we interviewed reported that the volume and breadth of their social interactions actually increased significantly at the onset of the pandemic. However, for many people the novelty of virtual interactions quickly faded. In February 2021 about 30% of interview participants reported virtual social fatigue, despite not being directly asked about this (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Percentage of Interview Participants Who Reported Fatigue from Virtual Social Interactions

Many interview participants reported negative emotions about the state of their virtual socializing when these interviews were conducted in February 2021, including: "Zoom fatigue"; "no longer exciting"; "tired of it"; "sick of all of that"; and "tiresome." Some of these same interview participants cited a spike in social connection at the onset of the pandemic, but as time passed, the quantity and breadth of their virtual calls decreased. Even someone who described themselves as outgoing and social reported that "Zoom social is more exhausting than fulfilling for me." One person described their socializing as a V-shape in which their virtual socializing has recently bounced back, but in a different way:

It went kind of like a V shape. At first there was a lot more. And then everyone kind of got sick of Facetiming a lot. And then, uh, kind of gravitate towards it, but less, uh, with so many people at once like instead of maybe our whole group of eight friends getting together and everyone just has time to really say hi, [it would] be smaller groups like one-on-one, maybe groups of two or three people.

Although this person was able to modify their virtual interactions to make them more fulfilling and "bounce back" on their self-described V-shape, many other interview participants had hit the bottom of the V and were not willing to bounce back until they could see their friends and family in person again.

Conclusions

Key Findings

Our initial findings from our qualitative analysis of 64 one-on-one interviews identified four main themes. First, we observed a reduced likelihood of building new social capital over the course of pandemic among our interview participants; however, some individuals also engaged in new social behavior and joined virtual groups, from yoga to dog walking clubs. Second, individuals discussed severing bonding ties with individuals whose behavior during the pandemic diverged from that of the respondent. Third, individuals reported a loss of work-related, or bridging social capital due to job loss or the transition to "work from home." Finally, 30% of our participants indicated virtual social fatigue nearly a year into the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implications for Practice

By conducting in-depth interviews, we captured important themes of social and protective behavior nearly one year into the COVID-19 pandemic. We know social capital to be an important factor in driving resilience in a crisis. Resilience, defined as “the ability to adjust to ‘normal’ or anticipated stresses and strains and to adapt to sudden shocks and extraordinary demands (Bruijne et al., 2010, p.2712),” is often the outcome when individuals or communities possess what Aldrich (201213) refers to as “deep reservoirs” of social capital. For example, following Hurricane Katrina, individuals with strong ties to their communities return at rates faster than those without ties (Aldrich 2012). However, the COVID-19 pandemic presented several challenges to maintaining social ties, and in some cases, individuals chose to sever ties when they disagreed with the behavior of their close friends or family. The full impact of the pandemic is still unknown; however, the themes from our interviews indicate that the pandemic could have long-lasting effects on the resilience of individuals in future crises.

Dissemination of Findings

We intend to complete this research in 2023 and share our findings with both the individuals who participated and the community leaders in the communities in which our participants live. Our team intends to present our initial findings at conferences and submit several focused studies to peer-reviewed journals. We are interested in advancing our understanding of social capital in a prolonged pandemic. COVID-19 presented unique challenges, especially in its early months when NPIs were the only protection against the virus; however, these very measures upset deeply cherished and practiced social traditions, from family gatherings to congregational worship in faith communities. The outcome of this study will explore how, if at all, individuals remained engaged in their communities and how the pandemic changed the nature of social networks at the same time.

Limitations

The methodology of our study offered many benefits such as the ability to interface with participants to allow them to share their experiences through a semi-structured approach. Qualitative studies offer both data and context not available otherwise. However, as advantageous as the methodology is for this research, there are reliability and validity considerations that should be noted. The following section explores the disadvantages of the methodology due to sampling biases and the possibilities of human error that cannot be controlled. Additionally, confounding variables that could explain our conclusions should be considered.

External Validity

The sampling biases present in our research are influenced by our participant pool. There are biases in the make-up of our participant pool that impact the external validity or greater generalizability of the results. The first is that our participant pool comprises residents of two northeast cities, Boston and New York City. Geography influences responses because there are perspectives that are more prominent in some regions in comparison to others. For instance, the geopolitical climate in the United States varies by state, and Boston and New York City are predominantly liberal. Considering that the pandemic has been politicized, the content of the study appeared to have attracted participants that were willing to dedicate time to answering surveys and completing an interview regarding this important topic. In 100% of the interviews conducted, the participants indicated they believed in the legitimacy of the threat of the COVID-19 virus. However, a survey conducted by Pew Research in late March of 2020, only two-third of respondents indicated COVID-19 as a serious threat (Deane et.al., 202114). Location can also influence responses regarding isolation and activity level. The interviews were conducted in the winter of 2021 when Boston and New York City are colder, resulting in residents spending more time indoors. These participants are therefore possibly more isolated than their southern counterparts. Furthermore, responses to questions regarding behavior changes and community support are likely to vary from city to suburban to rural communities.

Additionally, pandemic guidelines and restrictions are specific to each local government in the United States, which ultimately could influence residents' behaviors. Considering these biases, it would be difficult to generalize the results of the research to any residents beyond the cities of the northeast region.

Another issue that could affect generalizability is that there is little diversity in the socio-economic class (SES) and race of the interviewed participants. Our participant pool consisted mostly of middle-class non-minority college students or working professionals. The sample did not have many minorities despite the 47.2% minority composition of Boston and 30.4% minority composition of New York City (United States Census Bureau, 2019). The lack of representation of low-SES individuals could be influenced substantially by the format of the interview, which requires that a participant have access to a computer as well as stable internet service. Interviews were also conducted in English, which excludes non-English speakers.

Internal Validity

Although our study identified themes at this stage, we are not making any causal claims. We are further investigating if the themes from our initial qualitative analysis are due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, occurred during a time full of other stressors such as the political climate and civil unrest. The experiences of the interview participants are therefore more nuanced, making it difficult for a cause-and-effect relationship between COVID-19, behavior changes, and social capital to be established. For instance, the theme regarding the loss of work social capital could be directly related to the work-from-home situation or loss of employment; however, it could additionally be due to an avoidance of politically-charged discussions surrounding events such as the Black Lives Matter protests. It should be noted that many stressors in 2020 were byproducts of the pandemic. Stressors that could affect social capital were found in our interviews, including childcare, financial distress, health, and a loss of work-life balance, which all seem to be byproducts of the pandemic.

Reliability

The last consideration is interviewer bias and the influence this may have on reliability. There were a total of six qualitative researchers who conducted interviews guided by an interview script. These researchers also had the option of asking follow-up questions and probing for elaborations, which were contingent on the answers provided to the initial question. These follow-up questions and the level of probing could vary and skew the prominence of some themes over others. Additionally, the interview participant's willingness to offer information is both dependent on their comfort level and the interviewer's ability to establish rapport. Lastly, there were opportunities for human error or oversight. Human error or oversight could occur during the transcript review process when correcting transcription errors. Although the transcription software produces a confidence level and an accuracy graph which were all above 70%, failing to correct some of the errors could result in a misinterpretation of the data contained. Human error or oversight could also occur while coding the transcripts. In future studies, our team will manually code transcripts to ensure accuracy.

Future Research Directions

Future research will explore how social capital influenced an individual's likelihood to maintain social ties, despite the challenges distancing imposed. For example, it is not clear to us why some people maintained the virtual calls they started at the beginning of the pandemic while others succumbed to fatigue. Further, we observed that almost all interview participants had stable internet access that allowed them to conduct video calls if they desired. Our team will investigate other sources of resilience that may inform future interventions to build resiliency before the next pandemic or prolonged crisis.

References

-

Hurlbert, J. S., Haines, V. A., & Beggs, J. J. (2000). Core networks and tie activation: What kinds of routine networks allocate resources in nonroutine situations? American Sociological Review, 598-618. ↩

-

Elliott, J. R., Haney, T. J., & Sams-Abiodun, P. (2010). Limits to social capital: Comparing network assistance in two New Orleans neighborhoods devastated by Hurricane Katrina. The Sociological Quarterly, 51(4), 624-648. ↩

-

Hawkins, R. L., & Maurer, K. (2010). Bonding, bridging and linking: How social capital operated in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. British Journal of Social Work, 40(6), 1777-1793. ↩

-

Szreter, S., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(4), 650-667. ↩

-

Aldrich, D. P. (2019). Black wave. University of Chicago Press. ↩

-

Aldrich, D.P., Page-Tan, C., Fraser, T., Lee, J., and Yoshida, T. (2020) Social Ties, Quarantine Policy, and the Spread of COVID19. Quick Response Report. Natural Hazards Center: University of Colorado-Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/social-ties-quarantine-policy-and-the-spread-of-covid-19 ↩

-

D'Exelle, Ben. (2014). Representative Sample. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2476 ↩

-

Page-Tan, C. Marion, Summer, and Aldrich, Daniel P. (forthcoming) Information Trust Falls: The Role of Social Networks and Information During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Suburbanites ↩

-

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of management review, 27(1), 17-40. ↩

-

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380. ↩

-

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2010). How's the job? Well-being and social capital in the workplace. ILR Review, 63(2), 205-227. ↩

-

Bruijne, M., Boin, A., & van Eeten, M. (2010). Resilience: Exploring Concepts and Its Meanings. In L. K. Comfort, A. Boin, & C. Demchak (Eds.), Designing Resilience : Preparing for Extreme Events. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. ↩

-

Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. University of Chicago Press. ↩

-

Deane, C., Parker, K., & Gramlich, J. (2021, March 5). A year of U.S. public opinion on the coronavirus pandemic. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/2021/03/05/a-year-of-u-s-public-opinion-on-the-coronavirus-pandemic/ ↩

Page-Tan, C., Marion, S., Aldrich, D. P., Holck, D., Liu, M., Pimentel, L., & Shejwal, P. (2021) Social Capital and the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Preliminary Qualitative Analysis (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 335). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/social-capital-and-the-covid-19-pandemic