Solidarity and Storytelling: Debris and Visual Expressions of Collective Community After the 2019 Lee County, Alabama, Tornado

Publication Date: 2020

Abstract

Our research focused on the 2019 Lee County tornado that occurred on March 3, 2019. The research aims for this fieldwork were threefold: 1) to use social media information about tornado debris to create two-dimensional trajectories illustrating debris spread for different sizes and shapes of debris, 2) to identify important aspects of the warning system that the community experienced during the event, and 3) to identify instances of collective community solidarity (both in the community and online). The team also explored the social impact and processes related to the event, including memorialization, spirituality, and religious or ritualistic aspects of the event. Results included documentation of debris that traveled 20 miles (32 km), inconsistent warning dissemination, and instances of collective solidarity (Beauregard Strong ) displayed on community signs and in online community forums. Another finding that emerged was that physical donations became a problem for local churches that ran out of space for storing the donations. Many of the donations came from states as far away as Pennsylvania. In total, the Lee County tornado outbreak confirmed known research on debris spread as well as research on pro-social responses in disasters. The data also revealed ongoing problems with warning systems and donations management.

Figure 1. Students examine debris on Highway 51.

Overview

The EF-4 tornado that touched down in Lee County, Alabama, on March 3, 2019 killed at least 23 people. There were multiple tornados that touched down throughout the southern United States on March 3rd, but the Lee County tornado event was the focus of substantial news media and public attention. Understanding the ways in which survivors sought protection and received vital warning information may be important for emergency managers, meteorologists, and other stakeholders involved in risk communication for tornadoes. Additionally, identifying the physical aspects of debris spread for items of differing sizes and shapes has the potential to inform policies and practices on risk communication and mitigation planning.

Literature Review

While research on disaster warnings is increasingly expansive (e.g. Sorensen, 20001; Wood et al., 20182) and tornado “subculture” has been identified as a growing area of research interest (Webb, 20183), there are still facets of research on tornadoes that require additional study. This study focuses on extending existing research on warnings (who received the warnings and how), debris trajectories (Knox et al., 20134; Black et al., 20195), and collective solidarity (“Lee County Strong” and other examples) – and linking this to physical and social impacts of tornado events. Furthermore, this research has the potential to expand the literature on prosocial behavior after disasters (e.g., Drabek, 20136; Rodriguez et al., 20067), considering that evidence from social media suggests that many of the early “first responders” were neighbors and friends in the impacted areas. Among natural hazard events, tornadoes are rapid onset, which makes them dangerous and often deadly. While research on tornado warnings and impact is not new (Boruff et al., 20038), additional research is needed to understand ways to prevent deaths and injury. Additionally, when tornadoes do occur, they provide opportunities for researchers to expand findings on the physical and social aspect of catastrophic tornado events.

Debris spread can indicate key information about the tornado (Knox et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 20149) and provide forensic information about the physical strength, distance, and path of the thunderstorm and the associated tornado funnel. Using social media data, Knox and students (2013) identified record distances of debris through tracking items such as photos and other artifacts. This Knox and colleagues 2013 study was the most comprehensive analysis at that time of tornado debris. Since then, a subset of the original team has extended its research to heavy debris hurled by the “Tybee tornado” along the Georgia coast (Black et al., 2019). However, tornado debris continues to be an understudied aspect of severe weather. Debris tracking is particularly important for identifying and recording key community characteristics (Nakamura, 201210). As social media becomes a more common way to record life events, including visual histories linked to personal narratives, tracking information on social media may become an increasingly critical way to understand community history. Such approaches can also create a link between physical and social aspects of the disaster to aid in understanding of key behavioral findings (Lindell & Prater, 200311).

Considering the fatalities, mapping the ways in which people received and acted upon warning information is important for future safety planning initiatives. While forensic and physical studies on tornados provide information about possible injury prevention (Brenner & Noji, 199512; Simmons & Sutter, 200813; 201314), research on risk interpretation and communication can provide useful information about the limitations of warnings (Ripberger et al., 2015 15; Wood et al., 2018), including any possible differential impacts. Since children were killed in this event, it is also important to identify ways in which families and young children may have been at a greater risk due to key factors such as physically unsafe housing. Research on children in disasters is also a growing but understudied area (Peek, 200816; Silverman & Greca, 200217). Traumatic stress in catastrophic events is also an area of study that could benefit from additional research, including examination of event-specific case studies (North et al., 201218).

Collective solidarity plays an important role in community recovery and as such, is of interest to disaster researchers. Prosocial behavior after disasters is common (Drabek, 2013; Oliver-Smith, 201219; Rodriguez, Trainor, & Quarantelli, 2006), but there is a lack of research on visual and web-based displays of collective solidarity (Ryan & Hawdon, 200820). Social media displays of collective solidarity can be multifaceted and can include for example, pages devoted to the identification and return of items lost due to tornadic winds. Displays of solidarity may also be linked with mourning and memorialization (Grider, 200621; Margry & Sánchez-Carretero, 201122). Research on online mobilization suggests that even visual displays of solidarity or communication, such as the hashtag symbol can help to galvanize community efforts after disasters, such as was the case after Super Storm Sandy (Donovan, 201823).

Spontaneous shrines and expressions of solidarity may have several different functions for individuals and communities – from engaging in closure, celebrating lives of victims, and/or making political statements about the disaster. Much of the research on collective solidarity has been conducted in the context of 9-11 (Haskins & DeRose, 200324), mass shootings, (Giglietto & Lee, 201725) or other large-scale events (Hawdon & Ryan, 201126). There is a scarcity of research on understanding the specific processes, meanings, and outcomes of memorialization in smaller-scale localized disasters such as a tornado event.

Research Questions

Debris: What is the pattern of debris spread? What are the sizes and weights of debris, and what are the differences in trajectories of debris of different sizes and weights?

Warnings & sheltering: When, where, and how did community members receive warnings for the tornado? How and where did community members shelter during the tornado? What groups were impacted and identify differential impacts?

Collective solidarity: What indicators suggest that the community has engaged in collective solidarity as a part of recovery? (e.g., road-side signs, churches, signs on businesses, donation drives, fund-raising announcements; road-side memorials, memorials at site of impact).

Methods

Part I. Team 1. For the first team led by the PI (DeYoung), primary data were gathered through observation, interviews, and photographs during a two day-deployment to the community of Beauregard, Smiths Station, and Opelika in Lee County, Alabama. As time passes, memories of respondents may fade, and this might impact the content and recall of valuable information such as the method of receiving the warning, and specific details regarding protective action. Additionally, identification of debris, expressions of solidarity, prosocial behaviors, and other social aspects of the disaster are more likely to be happening in the days and weeks following the disaster rather than months or years after the event. We had a semi-structured interview guide for face-to-face participants that contained 15 questions about warnings, impacts of the tornado, volunteer engagement, stress, protective action, and demographic information. For the web-based instrument, there 26 questions about the warning received, channel for the warning, volunteer engagement, protective action, and demographic information. Informed consent statements were displayed before participants clicked on the web-based survey and explained in person during the face-to-face interviews. IRB approval for this project was obtained from the University of Georgia.

The first team gathered 32 total community responses (n=28 web responses and four face-to-face interviews). The team used a combination of convenience and snowball sampling techniques. Many people were displaced and living in temporary housing immediately following the event and therefore difficult to access. Two of the face-to-face respondents were recruited through the networks of the principal investigator’s student who was raised in Opelika and whose mother worked at a local church.

Specifically, one month after the disaster the first team launched a web-survey in several groups (e.g. Beauregard Strong and parenting groups in Auburn and surrounding areas). Three weeks after the disaster, the first team conducted four in-depth semi-structured interviews with community members about their experience related to getting the warning, helping others after the event, perspectives of recovery, and interpretations of meaning surrounding the event. The web survey took approximately 10 minutes to complete and contained questions about sheltering, warnings, donations, and volunteering and community activities. The face-to-face interviews contained the same questions with more in-depth follow-up and probing regarding community solidarity, donations management, and mental health resources.

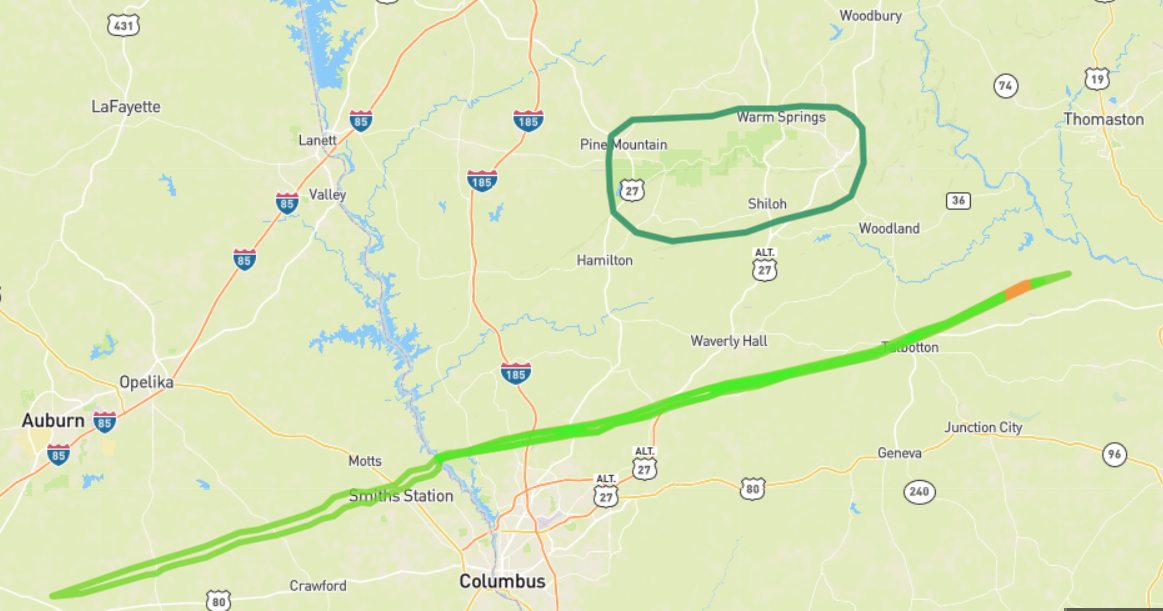

Part II. Team 2. For the second team led by the Co-PI (Knox), primary data were gathered through observation, social media data mining, photographs, and a respondent interview, all of which were conducted along and just to the north of the tornado path ranging from Lee County, Alabama, to Warm Springs, Georgia.

The second team gathered 45 point-to-point trajectories of tornado debris items via social media data mining. The second team investigated tornado debris from an unwarned tornado in Pine Mountain, Georgia, created by the same supercell thunderstorm that spawned the Lee County, Alabama, tornado. Finally, the second team conducted an interview with a couple who found debris from Beauregard, Alabama, in Lee County in their field in Durand, Georgia—which is 48 miles (77 km) from Beauregard.

SPSS statistical software was used to generate descriptive data from the respondent data. For preliminary qualitative data analyses, we identified themes from the interview data using an open-coding content analysis approach (Saldaña, 201527). Open coding is useful in cases in which multiple meanings or categories may emerge from the data (Moghaddam, 200628). Additionally, we used an inductive approach in which we detected new patterns during data collection that informed additional analyses. For example, while questions about physical donations were not included in our original instrument, field observations of excessive donations prompted us to ask questions about these donations during the interviews.

Results

Demographic Information

Face-to-face interviews (n=4) conducted by the first team were with female respondents ranging in age from 44 to 72. For the web-based response data (n=34), the average age of respondents was 42. For housing type, 16 (57 percent) indicated living in a stand-alone house, six (21 percent) indicated residing in a mobile home, and four respondents indicated living in an apartment or other structure type. Of the face-to-face interviews, one respondent lived in a mobile home that was destroyed during the tornado and the other three sought shelter in the interior of their homes during the event. The first team also had informal conversations with three emergency management officials at a donation distribution center and two business managers in downtown Opelika. Of the nine individuals that the first team spoke with (in depth interviews and informal conversations), all knew someone personally who was injured or killed in the disaster. For household income, 43 percent of the respondents from the web-based data indicated a household income of $39,000 or less a year. Additionally, 60 percent of the web-based respondents indicated having children in the household (n=16). For ethnicity, two of the respondents were African American (one face-to-face interview and one from the web-based data) and the remaining respondents were white. The second team interviewed a couple from Durand, Georgia, about debris that landed in their field that had originated from the Lee County, Alabama, town of Beauregard. Both subjects were white, with the female of age 40 and the male of age 53.

Observational Data

During the two-day time frame in which the first research team was in the impacted communities, the first team took over 385 photos to document placement of debris, community expressions of solidarity, and evidence of recovery. The solidarity photos will be described in detail in sections below. Detailed coding of photos will include a process in which the photos will be assigned categories for meaning (recovery, solidarity, donations, or other).

The second team observed and photographed (approximately 50 photos) evidence of tornado debris from the Lee County, Alabama, tornado in both Alabama and Georgia. In addition, the second team documented tornado debris in Pine Mountain, Georgia, associated with an unwarned tornado spawned by the same supercell thunderstorm that caused the Lee County, Alabama, tornado. Finally, the second team interviewed a couple from Durand, Georgia, about debris that landed in their field that had originated from the Lee County, Alabama, town of Beauregard.

Warning

Face-to-Face Interviews. In all of the first team’s face-to-face, in-depth interviews there were expressions indicating that some community members received no tornado warning (i.e. word of mouth that there were friends and neighbors who did not receive warning). One respondent who was in her mobile home indicated that she got a severe weather warning on her phone prior to the event but that she never received a tornado-specific warning. Two respondents specifically stated they had signed up for warnings in the Lee County area because of their jobs working in the school system, and yet received no warning. Another respondent indicated that she did receive a tornado warning but she was confused because she was unable to hear the outdoor sirens. Another respondent never received a tornado warning and did not know about the event until she discovered conversations on social media about it later that evening.

Other respondents indicated that although they received a warning, it was for the entire county (Lee County) and therefore it was unclear to them if the warning applied to their specific area: "The only warning we received is for Lee Co not a specific area. We need sirens in the area," and another respondent indicated, "Most people wasn't [sic] alerted and that concerned me."

Some respondents indicated advanced warnings (half of them got a warning, the other half did not). Respondent Number 1 got a watch notification on her phone but not a warning. Respondent Number 2 got a warning on her phone as the tornado passed through her neighborhood. Respondent Number 3 got an alert on her phone and sheltered in place with her children. Respondent Number 4 did not get an alert on her phone, even though her mobile home was destroyed while her and her husband were inside. Specifically, she indicated, "I started receiving warnings 24 hours before the tornadoes. I received an email and a phone call alerting me to bad weather the next day."

Respondent Number 3 from the (n= 4) face-to-face interviews indicated that she did get the tornado-specific-warning and that she sheltered in the interior of her house, along with her husband and son. Another respondent received a “severe weather” warning but not a tornado warning. She was watching television in her mobile home when the tornado tore the roof from her home: "We were watching TV and then I looked up and saw the sky."

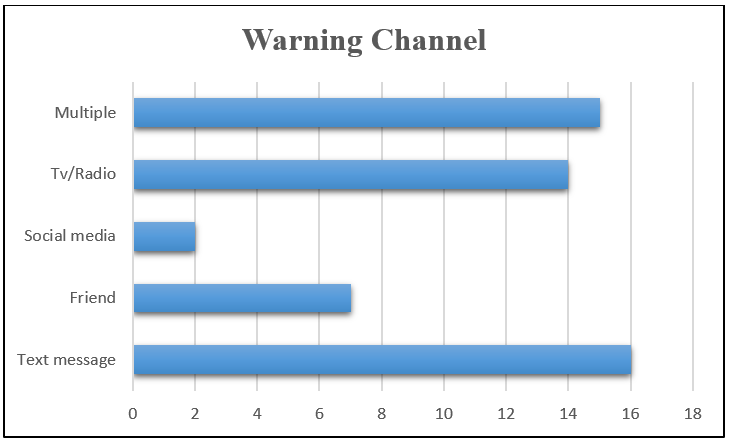

Figure 2. Warning Channels.

When people who did receive the warning received the message, most respondents indicated that they engaged in protective action by sheltering in the interior of their home. Some people who received the warnings sought shelter in the Providence Baptist church, which has a basement storm shelter.

Web-based Respondents. Five of the 34 respondents received no tornado warning before the event. For method of receiving the warning, web-based respondents indicated that they received the alert through multiple channels (n=15, 58 percent). Many of the web-based respondents (62 percent) received an automatic text alert, while others received the information from the television or radio (n=14, 54 percent). Some respondents also indicated that a friend called them when the warning was issued (n=7, 30 percent).

Debris in Beauregard, Alabama

Figure 3.

Since the tornado occurred on March 3 and we deployed to the community the weekend of March 30, nearly four weeks had passed. When we drove south on highway 51 towards Highways 38 and 39, there were visual indicators of smoke in the sky, which was likely debris being burned. When we arrived at one of the main points of impact where highways 38 and 51 intersect, debris was evident on either side of the road for several kilometers. Debris included plywood, tires, trees, clothing and other textiles, metal scraps from construction, furniture, cars, glass, and other materials from the homes that were destroyed.

There were bulldozers, backhoes, and other debris removal equipment being used by homeowners, ad hoc groups, and members of official organizations (city utilities workers) engaging in debris removal. In places where mobile homes had been destroyed, there are were ad hoc memorials for victims who died. Many of the homes had large dumpsters, storage containers for moving furniture, and other supplies that indicated that many of the partially damaged homes were being cleared out. Some residents had RV’s and trailers parked in the driveway of the damaged areas, indicating that some people were living on site as they worked on debris removal. There were also multiple posts in social media groups in which community members were coordinating efforts for debris removal.

Figure 4.

It was unclear from visual inspection if there were discrepancies in speed of debris removal throughout the community. However, there was at least one house that was already being completely rebuilt. We later interviewed a respondent whose house was being rebuilt and she indicated that the house being built over the site of the damaged home was replacing her mobile home. She noted that the damage to her mobile home was complete, except for the double-framed windows which remained intact.

Debris Elsewhere in Lee County and in Georgia

The second team (Co-Principal Investigator Knox and students) identified the debris spread from the 45 items data-mined from social media. Of note is an area of denser fallout of debris, a “hot spot,” in the vicinity of Warm Springs, Georgia.

Figure 5.

Several debris items were notable enough to make the local and news. One such item was a flea market sign in Smiths Station, Alabama, that traveled 20 miles (32 km) across the state line into Georgia.

Figure 6.

The team followed the path of debris from Lee County into Georgia. In Pine Mountain, Georgia, the team documented additional debris caused by an unwarned tornado spawned by the same thunderstorm that caused the Lee County tornado. The unwarned tornado was one of many smaller tornados from the outbreak on March 3. The EF4 that caused damage and deaths was the only tornado for which warnings were issued by the National Weather Service. The debris encountered by the team consisted of two signs that blew across U.S. Highway 27 for approximately 50 yards (150 m). Based on the team’s observations, the tornado’s damage was consistent with the National Weather Service’s rating of it as an EF-1 tornado.

Figure 7.

Via data mining on social media, the second team located two residents of Durand, Georgia, who found multiple debris items from Beauregard, Alabama, in their field. Data mining for the purposes of this project included joining online groups (i.e., Beauregard Strong) and other forums for community members impacted by the tornado. In those groups, people posted images of lost and found items as well as damage reports, information about volunteering, and other information for the tornado-impacted community members. The research team made note of the relevant posts in an Excel spreadsheet so that we could reach out to key community members and obtain broader information about key locations in which debris were located. We conducted a 30-minute interview in which we learned the characteristics of the debris items; the exact location of the debris landfall; and other information related to the Beauregard tornado.

Figure 8.

From the two key respondents in Durand, the second team obtained a list of names and contact information for others in the Durand/Warm Springs, Georgia, area who also found debris on their property, but who are unlikely to be reached via social media because they indicated that they do not participate in social media.

Collective Solidarity

Everyone that the first team spoke with in-person (n=4) knew someone who was killed, injured, and/or who lost their home in the tornado. During each of the in-depth face-to-face interviews, respondents indicated that the community “came together” and “rallied together” to support the families most severely impact by the storm. One of the respondents hosted one of the families who lost family members in her rental house even though she did not directly know the family before the tornado. The rental house was normally used to host visitors during the football season for Auburn University.

The first thing that happened was a friend of a friend from cub scouts, one of the moms from cub scouts. She has a friend who was best friends who could not find and get the daughter to call them back. They are in Texas—they ended up being one of the families that had one of deceased and her fiancé was also killed. They all came from Texas to look for her… They were two of the last ones to be identified. We have a game-day rental—we had someone leave on Friday and we had not time to clean it but—they needed a place that they could stay and they could all stay together, coordinating with the family from Texas… It was more of a comfort care kind of thing.

The same respondent also used her rental house to host one of the victims who had been injured by the tornado. She indicated that donations and supplies for the rental house began arriving shortly after her social networks became aware of the family’s need for a temporary location.

The signs of Beauregard Strong were posted throughout the community in multiple locations, as well as online. In fact, Beauregard Strong was the name of the community-based Facebook group that provided community members with an opportunity to organize fundraisers, debris removal, and communicate other urgent needs in the days and weeks following the tornado. We also observed signs that said, Smiths Station Strong posted at church signs and in improvised spaces—mainly on the side of the highways near the heavily impacted areas. It should also be noted that people in the Facebook group were creating and selling Beauregard Strong memorabilia, with some efforts to direct proceeds for these items to families of the victims.

Figure 9.

Another respondent indicated that immediately after the event people appeared on site to help her with debris removal. She indicated that all of the neighbors came out of their houses after the tornado passed and that “We just knew to check on each other”. Another respondent recruited through with web-based data collection efforts similarly indicated that community members supported one another immediately after the event and in the days that followed:

People were able to immediately make family and friends aware they were safe. The pace of the recovery has benefited due to having a tool like Facebook to help connect people to volunteers with the tools needed for the job. The ability of having the phone chat on Facebook also helped people call each other without having a phone number.

Another respondent indicated that a neighbor was the first on site to perform CPR on one of the victims who had been trapped under debris. Other respondents indicated that the community members were the main people searching for bodies and working to identify victims immediately after the storm.

When you’re in a situation you’re overwhelmed by the monstrosity of everything that needs to be done but at the same time you’re overwhelmed at how people just show up in your yard and they say, ‘what can I do?’ and they just start working… The biggest thing is that you learn the true value of people in a situation like this.

Figure 10.

While the community recovery efforts initially focused on debris removal and working together to host displaced people, respondents also described efforts at donation sites and points of distribution, which were mainly at local churches. However, these points of distribution also received too many physical supplies and some church leaders were exasperated a month after the storm that many supplies remained at the points of distribution. Multiple churches that we visited has pallets of bottled water stacked in parking lots and inside of the church hallways. Used clothing was stacked to the ceiling of one church that we visited and this was a source of stress for the church leaders because they were uncertain about finding space for the donated supplies. We also observed stacks of bags of dog food, tables of infant formula, toiletries, non-perishable food, toys, and other items. One respondent in particular who was managing the donations indicated:

The problem is, we’re a place, Providence is a place, there are so many places, and there isn’t really one central location of [where the donations]. Also, people don’t know where to get the things they need, if some people don’t have internet access, they might not know to come get these items. There needs to be case management. The first day of the disaster was amazing, but every day since then has been the problem… There are all of these things, but I don’t think anyone has a place to put all of this. This is not how you help people.

The respondent indicated that a truck load of clothing arrived from Pennsylvania among the influx of donations that arrived. The respondent indicated that managing the donations was the most stressful aspect of the disaster for her. In this case, there was a gymnasium stocked with supplies and items.

Urgent Needs

Multiple respondents indicated that trauma and stress were lingering in the community. While respondents indicated that the county and city school systems had counselors visiting the communities, the respondents emphasized that there were not enough counselors to meet the vast needs. Many respondents indicated having nightmares and being hyper-vigilant. Other respondents were coping with feelings of guilt:

Survivor’s guilt is a real thing. My husband has also suffered. You know, waking up at night with nightmares and that sort of thing. I have students that were affected. A lot of people and counselors have been coming out to the schools. Lee County had a meeting with the faculty and there have been programs available.

Another web-based respondent indicated:

I have experienced emotional trauma from this incident. My son and I both have storm related anxiety. I think counseling should be offered to the community. It will take years to rebuild, but also to heal emotionally for many families. I am not sure counseling resources have been provided to those that need it most.

There were also instances of families that still had injured family members in the hospital at the time of our deployment. One respondent indicated that there were families that had two caregivers that were both hospitalized at one time, making childcare difficult. Additionally, some respondents indicated that there were concerns with health insurance and that some of the victims did not have a financial safety net for handling medical bills after the tornado.

Finally, there was noticeable interest in investing in storm shelters. In two of the daily print newspapers there were advertisements for household storm shelters. In the online groups, community members engaged in dialogue about the benefits and cost of the storm shelters. Some of the respondents indicated that the cost of building and installing the storm shelter would be the primary factor in deciding to obtain one. In April of 2019, Alabama lawmakers introduced HB 428, which would provide tax breaks for households that purchased a storm shelter.

Another notable aspect of collective solidarity online has been the creation of multiple Facebook pages for the posting of debris items, especially photographs, with the intent of returning said items to their original owners. For example, different sites were created for Lee County such as Lee County Lost and Found and Beauregard Strong, specifically for the Beauregard community within Lee County. The first page had, as of April 26, 2019, a modest following of 45 members; however, the second page had on the same date a robust following of 2,396 members. The group forum continued for weeks and months after the disaster. In December of 2019, the group members communicated in the forum that the December 2019 tornado outbreak caused stress and trauma because it reminded them of the tornado event from March. This shows that online community groups can serve as a space for sharing emotions and feelings about stress about the event that may be triggered due to severe weather, anniversaries of the event, and other important social or environmental events.

Conclusion and Implications

Our findings suggest that the warnings system may have impacted the ability for some people to seek shelter in advance of the tornado. Additional research on the local weather forecast office and warning systems may provide clarification about improving the warning system, including reducing the number of unwarned tornadoes. According to the National Weather Service, the EF4 tornado was the only tornado for which warnings were issued on March third (National Weather Service, 201929). Some respondents also indicated that even though they did receive the warning for Lee County, the felt that this may not apply to them specifically. This is aligned with work by Mileti and Sorensen (1990) that a warning should include components that make the risk personalized by the individual receiving the message (i.e. “Does this apply to me?”). Reports after the tornado indicate that many of the victims who did not survive the tornado lived in mobile homes, which indicates that housing structure continues to be an important factor in predicting mortality in tornado events.

Another finding of note is that debris from the Lee County tornado fell out of the sky in a localized area of southwest Georgia. The collective activities of residents in both Alabama and Georgia provided the opportunity for items to be reclaimed by their owners, particularly photographs, and also enabled this research, as in the case of debris from the 2011 Tornado Super Outbreak (Knox et al., 2013). Our work described above, including the in-person interview in Durand, Georgia, confirmed the localization of debris and provided additional contacts for future work.

Similar to research by Drabek (2013), Rodriguez and colleagues (2006), and Quarantelli (1982), the communities that were impacted by the tornado in Lee County on March 3rd rallied together during and after the disaster to support neighbors, friends, colleagues, and one another. Additional research is needed on the constructions and meanings of the “Strong” signs and memorabilia because the literature on the functionality (i.e. coping, fundraising, raising awareness) of these messages is scarce. Research in this area so far has identified that victims and community members may use the event to construct meaning during recovery and to display solidarity with the community through asserting identity through shared values (Giglietto, 2017). Localized events such as tornados or other hazards generate the “Strong” messages that are contained within the geographic area while more visible international catastrophic events garner attention throughout the globe. Future research should compare mechanisms for dissemination of such messaging and related displays of solidarity, including the potential benefits for community bonding.

There was also evidence that a “second disaster” impacted the community—in the form of an unmanageable amount of physical donations. This is consistent with previous research by Holguín-Veras, Jaller, Van Wassenhove, Pérez, and Wachtendorf (2012) indicating that physical donations can be a burden on the local community, despite the intentions of groups who sent those donations (Nelan et al., 201930). Given this situation, it is important to communicate that cash/monetary donations are more effective in assisting a community after disaster than in-kind goods. Finally, community and stakeholder interest in installing storm shelters was high immediately following the event. If this interest leads to legislation that provides tangible benefits for community members, this will be consistent with Birkland’s policy research on focusing event theory, underscoring the potential policy change impact of disasters (Birkland, 2006 31; Birkland & DeYoung, 201232). Policies and programs that would reduce loss of life for tornado events may include funding allocation for storm shelters in mobile home communities, improved warning systems and continued research on warning dissemination in rural communities, and continued documentation of debris travel from tornados.

Acknowledgements. Quick Response Research Reports are based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF Award #1635593). We also would like to thank residents from the community who facilitated data gathering, specifically Victoria M. Jackson from Opelika, Alabama, and Sabrina and James Cuddington of Durand, Georgia. Students for this fieldwork deployment included Prabhjot Minas (a University of Georgia graduate currently at the University of California, San Francisco medical school), Lindsey Nixon, Nick Morgan, and Evan Vickers (University of Georgia Department of Geography).

References

-

Sorensen, J. H. (2000). Hazard warning systems: Review of 20 years of progress. Natural Hazards Review, 1(2), 119-125. ↩

-

Wood, M. M., Mileti, D. S., Bean, H., Liu, B. F., Sutton, J., & Madden, S. (2018). Milling and public warnings. Environment and Behavior, 50(5), 535-566. ↩

-

Webb, G. R. (2018). The Cultural Turn in Disaster Research: Understanding Resilience and Vulnerability Through the Lens of Culture. In Handbook of Disaster Research (pp. 109-121). Springer, Cham. ↩

-

Knox, J. A., Rackley, J. A., Black, A. W., Gensini, V. A., Butler, M., Dunn, C., Gallo, T., Hunter, M. R., Lindsey, L., Phan, M., Scroggs, R., & Brustad, S. (2013). Tornado debris characteristics and trajectories during the 27 April 2011 super outbreak as determined using social media data. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 94(9), 1371-1380. ↩

-

Black, A. W., Knox, J. A., Rackley, J. A., & Grondin, N. S. (2019). Tornado debris from the 23 May 2017 “Tybee Tornado.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 100(2), 217-222. ↩

-

Drabek, T. E. (2013). The human side of disaster. CRC Press. ↩

-

Rodriguez, H., Trainor, J., & Quarantelli, E. L. (2006). Rising to the challenges of a catastrophe: The emergent and prosocial behavior following Hurricane Katrina. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 604(1), 82-101. ↩

-

Boruff, B. J., Easoz, J. A., Jones, S. D., Landry, H. R., Mitchem, J. D., & Cutter, S. L. (2003). Tornado hazards in the United States. Climate Research, 24(2), 103-117. ↩

-

Zhou, H., Dhiradhamvit, K., & Attard, T. L. (2014). Tornado-borne debris impact performance of an innovative storm safe room system protected by a carbon fiber reinforced hybrid polymeric-matrix composite. Engineering Structures, 59, 308-319. ↩

-

Nakamura, F. (2012). Memory in the debris: The 3/11 Great Japan earthquake and tsunami (Respond to this article at https://www.therai.org.uk/publications/anthropology-today/debate). Anthropology Today, 28(3), 20-23. ↩

-

Lindell, M. K., & Prater, C. S. (2003). Assessing community impacts of natural disasters. Natural Hazards Review, 4(4), 176-185. ↩

-

Brenner, S. A., & Noji, E. K. (1995). Tornado injuries related to housing in the Plainfield tornado. International Journal of Epidemiology, 24(1), 144-149. ↩

-

Simmons, K. M., & Sutter, D. (2008). Tornado warnings, lead times, and tornado casualties: An empirical investigation. Weather and Forecasting, 23(2), 246-258. ↩

-

Simmons, K., & Sutter, D. (2013). Economic and societal impacts of tornadoes. Springer Science & Business Media. ↩

-

Ripberger, J. T., Silva, C. L., Jenkins-Smith, H. C., & James, M. (2015). The influence of consequence-based messages on public responses to tornado warnings. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 96(4), 577-590. ↩

-

Peek, L. (2008). Children and disasters: Understanding vulnerability, developing capacities, and promoting resilience—An introduction. Children Youth and Environments, 18(1), 1-29. ↩

-

Silverman, W. K., & La Greca, A. M. (2002). Children experiencing disasters: Definitions, reactions, and predictors of outcomes. Helping children cope with disasters and terrorism, 11-33. ↩

-

North, C. S., Oliver, J., & Pandya, A. (2012). Examining a comprehensive model of disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder in systematically studied survivors of 10 disasters. American Journal of Public Health, 102(10), e40-e48. ↩

-

Oliver-Smith, A. (2012). The brotherhood of pain: Theoretical and applied perspectives on post-disaster solidarity. In The angry earth (pp. 170-186). Routledge. ↩

-

Ryan, J., & Hawdon, J. (2008). From individual to community: The “framing” of 4-16 and the display of social solidarity. Traumatology, 14(1), 43-51. ↩

-

Grider, S. (2006). Twelve Aggie angels: Content analysis of the spontaneous shrines following the 1999 bonfire collapse at Texas A&M University. In Spontaneous shrines and the public memorialization of death (pp. 215-232). Palgrave Macmillan, New York. ↩

-

Margry, P. J., & Sánchez-Carretero, C. (Eds.). (2011). Grassroots memorials: the politics of memorializing traumatic Death (Vol. 12). Berghahn Books. ↩

-

Donovan, J. (2018). After the #Keyword: Eliciting, Sustaining, and Coordinating Participation Across the Occupy Movement. Social Media + Society. https://doi-org.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/10.1177/2056305117750720 ↩

-

Haskins, E. V., & DeRose, J. P. (2003). Memory, visibility, and public space: Reflections on commemoration (s) of 9/11. Space and Culture, 6(4), 377-393. ↩

-

Giglietto, F., & Lee, Y. (2017). A hashtag worth a thousand words: Discursive strategies around# JeNeSuisPasCharlie after the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting. Social Media+ Society, 3(1), 2056305116686992. ↩

-

Hawdon, J., & Ryan, J. (2011). Social relations that generate and sustain solidarity after a mass tragedy. Social forces, 89(4), 1363-1384. ↩

-

Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage. ↩

-

Moghaddam, A. (2006). Coding issues in grounded theory. Issues in Educational Research, 16(1), 52-66. ↩

-

National Weather Service, 2019. Alabama Tornado Database, 2019. Retrieved at: https://bit.ly/2UzMciA ↩

-

Nelan, M. M., Penta, S., & Wachtendorf, T. (2019). Paved with Good Intentions: A Social Construction Approach to Alignment in Disaster Donations. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 37(2). ↩

-

Birkland, T. A. (2006). Lessons of disaster: Policy change after catastrophic events. Georgetown University Press. ↩

-

Birkland, T. A., & DeYoung, S. E. (2012). Focusing events and policy windows. In Routledge handbook of public policy (pp. 193-206). Routledge. ↩

DeYoung, S. & Knox, J. (2020). Solidarity and Storytelling: Debris and Visual Expressions of Collective Community After the 2019 Lee County, Alabama, Tornado (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 296). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/solidarity-and-storytelling-debris-and-visual-expressions-of-collective-community-after-the-2019-lee-county-alabama-tornado