To Remain or Relocate? Mobility Decisions of Homeowners Exposed to Recurrent Hurricanes

Publication Date: 2020

Abstract

Limited funds and growing demand for disaster assistance call for a broader understanding of why homeowners decide to either rebuild or relocate from their disaster-affected homes. This research explores the long-term mobility decisions of homeowners in Lumberton, North Carolina, who received Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) assistance for property acquisition, elevation, or reconstruction following Hurricane Matthew (2016). A subsequent disaster, Hurricane Florence (2018), devastated the city less than two years later, providing a unique opportunity to position long-term mobility decisions in the context of repetitive hurricanes. The authors conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 HMGP-recipient households to understand their long-term mobility decisions following Hurricane Matthew and perceptions of those decisions following Hurricane Florence. Findings suggest wealthier homeowners were more likely to choose property acquisition than either elevation or reconstruction, while more socially vulnerable homeowners expressed concerns about the affordability of relocation. In addition to income, the risk of subsequent disasters and willingness to accept that risk and a desire to remain in one’s current home and/or neighborhood played a significant role in the homeowner’s decision-making process.

Two Hurricanes in Two Years

In October 2016, Hurricane Matthew, the most powerful hurricane to strike the Atlantic coast that year, wrought $10.3 billion in damage across the southeastern United States. Lumberton, a city in southern North Carolina situated approximately 60 miles from the coast, received 12.6 inches of rainfall from the hurricane. In the weeks preceding Hurricane Matthew, Tropical Storms Julia and Hermine had dumped several inches of rainfall on Lumberton. , Immediately before Matthew, the Lumber River, which runs diagonally through the city from northwest to southeast, measured at flood stage (13 feet). On the morning of October 9, overwhelmed by the accumulated rainfall, the river swelled to 24.39 feet, then its highest recorded level. The city’s water treatment plant was flooded, preventing its then-approximately 22,000 residents from receiving running water for several weeks. While initially displacing thousands, one month before the second anniversary of the storm, county officials stated 750 Lumberton residents were still displaced. It is estimated that Matthew damaged 264 public housing units in the city “beyond habitability. ”

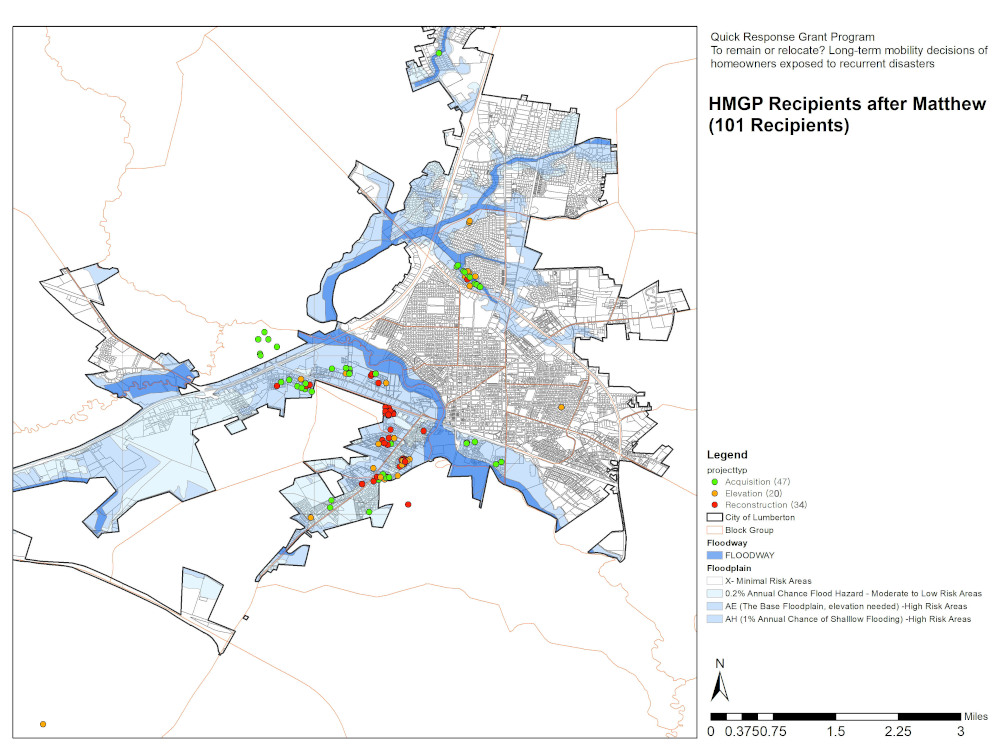

Following Hurricane Matthew, the city of Lumberton accepted applications for the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) from homeowners for property acquisition, elevation or reconstruction. More than 400 households in Lumberton applied to the HMGP, but only 106 homeowners were awarded assistance (five homeowners have since dropped out of the program, leaving 101 recipients). Only 800 households in North Carolina were awarded HMGP assistance; households in Lumberton constitute approximately 12.5 percent of all recipients. In Lumberton, 47 homes are currently slated for property acquisition; 20 for elevation; and 34 for reconstruction. The majority of properties are located in either a floodway or floodplain and lie primarily in the southern and western portions of the city. The city estimated that the costs incurred from the HMGP will total $13.5 million. The discrepancy in costs between the three mitigation categories is negligible—on average, the city anticipates it will spend $127,872 per acquisition, $124,820 per elevation, and $129,213 per reconstruction.

In September 2018, as the city was still reeling from the devastating effects of Hurricane Matthew, another storm—Hurricane Florence—swept the Carolinas, dumping 22.76 inches of rain on Lumberton. The Lumber River swelled to 25.4 feet—more than a foot above its peak in Hurricane Matthew. In the days preceding Hurricane Florence, the city crafted a temporary berm around the water plant and pumped water out of the levee to provide more room for rainfall. While the city has devoted increased attention to hazard mitigation planning in the wake of Hurricane Matthew, construction on a floodgate in West Lumberton, which “could reduce the damage from a Matthew-like flood by at least 80 percent,” had not been initiated by Florence’s descent.

A second HMGP program was initiated after Hurricane Florence; as of April 2019, 101 homeowners in Lumberton had newly applied to the program, but funding had not yet been awarded as of the publication of this report. The vast majority of applicants (68 homeowners) seek property acquisition. Twenty-nine homeowners applied for elevation, while a mere two homeowners applied for reconstruction, and two homeowners remain undecided. While applicant properties are dispersed across the city, nearly all are situated in either a floodway or floodplain. Endnote 1

Struggles to recover amidst higher social vulnerability

Lumberton—with a median household income in 2016 of $31,126 to the state’s $48,256—is consistently ranked one of the poorest cities in North Carolina. Over one-third of the city’s population (35.1 percent)—more than twice the rate for the state (16.8 percent)—lives below the poverty level. The poverty level has climbed substantially in recent years: in 2000, around one-fourth of individuals lived below the poverty level. Economic troubles, which have beleaguered the city for the past several decades, contributed to the near 10 percentage point increase in the poverty level. Federal policies instituted in the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (1994) and the Tobacco Reform Act (2004), derailed the manufacturing and tobacco industries, effectively eradicating the base for much of the city’s economic activity. From 1993 to 2003, Robeson County lost an estimated 8,708 manufacturing jobs. In an era that increasingly prides itself on knowledge-based work, former manufacturers without a high school diploma are left with few opportunities for employment. In 2016, the city’s labor force participation rate, which reflects the proportion of the total number of individuals actively seeking labor to the total number of people eligible to participate in the labor force, measured a meager 47.5 percent compared to the state’s 62.6 percent. In other words, able-bodied residents of Lumberton simply aren’t seeking jobs, at least in the formal economy. Currently, educational services, health care, and the social assistance industry comprises the majority of jobs in Lumberton (27.6 percent in 2016), followed by manufacturing and retail trade (18.7 percent and 11.3 percent in 2016, respectively)Endnote 2.

Diminished economic activity, the consequent increase in the poverty rate, and lower income levels due to the city’s abating job base have exacerbated Lumberton’s social vulnerability. The city’s sociodemographic composition diminishes the ability of residents to mitigate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters. Lumberton is racially diverse: in 2016, 39 percent of the population was white; 37 percent was African American; and 13 percent was Native American (the remaining 11 percent was either another race or two or more races, while 9 percent of the total population was Hispanic or Latino.) A mere 17.5 percent of residents over 25 years of age have completed at least a bachelor’s degree compared to the state’s 29 percent. The city contains a higher concentration of renters than homeowners—in 2016, 54.5 percent of households were renters (renters are more susceptible to permanent displacement from disasters, translating into the potential for more significant losses in population in Lumberton). Slightly over one-third (35 percent) of residents in Lumberton are currently married (versus 48.9 percent for the state). The high social vulnerability of the city’s residents has prolonged the recovery trajectory of disaster-affected households, leaving those households more susceptible to deleterious effects from subsequent disastersEndnote 3.

Literature Review

Before the 1990s, disaster studies defined recovery as a process of multiple strategies to return to “normalcy,” trying to predict future hazards and protecting communities from the potential disaster events (Berke et al., 19931). However, subsequent studies have demonstrated that encouraging communities to return to their pre-disaster conditions essentially reproduces physical and social vulnerability and exacerbates racial and economic inequality (Elliott & Pais, 20062; Mileti, 19993; Muñoz & Tate, 20164). Previous research emphasizes the importance of assessing the hazard exposure and physical and social vulnerability of communities. The recovery process, which often occurs concurrently with reconstruction, provides communities the opportunity to reduce physical and social vulnerability in rebuilding efforts (Masterson et al., 20145). In this respect, relocating homeowners has been a preferred hazard mitigation method because residents can be relocated to safer places and land-use transferred to open space, an approach that aims to prevent future death or injuries (de Vries & Fraser, 20126). The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which launched the HMGP in the late 1980s, has implemented floodplain buyout programs since 1993. These buyouts are particularly prevalent in areas where structural mitigation measures do not prove cost effective and forewarning residents of an impending disaster does not mobilize household evacuation (de Vries & Fraser, 2012).

Despite growing interests surrounding buyouts, many researchers have pointed out that effective adaptation should have integrated policy options, such as development controls, emergency management, repair and reconstruction, and selective relocation (Nicholls et al., 20077), because individuals experience disasters at different rates as well as with different outcomes (Muñoz & Tate, 2016). In addition, since post-disaster recovery is a sequential process during which the household seeks temporary shelter, short-term housing, and then ultimately permanent housing, mobility decisions made in the immediate aftermath of a disaster contribute to long-term residential mobility and choice (Bukvic & Owen, 20178; Fussell et al., 20149; Fussell et al., 201010). In this process, various driving factors have been identified as determinants of mobility decisions, including disaster experiences, satisfaction of living conditions, citizenship, income level, race, assistance program, and social capital (Asad, 201511; Kick et al., 201112; Tate et al., 201613]; Xu et al., 201714). In addition, despite current limitations of funding opportunities, research has found governmental financial assistance to be one of the most critical factors behind post-disaster mobility decisions (Binder et al., 201515; Bukvic & Owen, 2017; Rashid et al., 200716; Xu et al., 2017).

Although previous research finds governmental financial assistance plays a pivotal role in post-disaster mobility decisions, the role of federal funding in facilitating hazard mitigation for individual homeowners through property elevation or reconstruction has not been well researched. In addition, few researchers have investigated the impact of subsequent or repetitive disasters on changes to recipients’ mobility decisions. The unique timeline of the allocation of disaster assistance to homeowners, which occurred between Hurricane Matthew (2016) and Hurricane Florence (2018), allows this research to contribute new knowledge regarding the impact of repetitive disasters on the mobility decisions of homeowners. The results expect to contribute new knowledge to enhance our understanding of the factors that shape the long-term mobility decisions of homeowners affected by recurrent disasters. In addition, growing demands for disaster assistance necessitate a deeper understanding of homeowners’ post-disaster mobility decisions to inform disaster recovery policy.

Methods

To identify interviewees, we used a HMGP recipient list provided by the City of Lumberton and Robeson County parcel data to determine the addresses of homeowners who received disaster assistance. In March, we sent potential subjects recruitment letters in the mail asking whether they would like to participate in our study. Seventy letters were sent out for recruitment and seven homeowners agreed to interviews; a 10 percent response rate. We also screened and enrolled interviewees while conducting field observations in Lumberton and added eight homeowners to the study in that way. In March and April of 2019, the authors conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 homeowners or related individuals who were awarded HMGP assistance following Hurricane Matthew: 13 homeowners and two family members. Among those interviewed, eight households will remain in their homes while seven will relocate from their homes—eight homes are slated for property acquisition, five for reconstruction, and two for elevation. In addition, the authors spoke with several officials in city government—the city and deputy city managers and a community development administrator—to understand the challenges faced by the city in the recovery process as well as the status of property acquisition, reconstruction, or elevation for HMGP recipients. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed (with the exception of three interviews in which the respondents requested not to be audio recorded). The authors used pseudonyms for names and property addresses to protect respondents’ confidentiality.

The interviews largely focused on 1) the property damage sustained by homeowners from both Hurricanes Matthew and Florence, 2) the motivations behind homeowners’ decisions to either rebuild or relocate from their homes, and 3) homeowners’ perceptions of their mobility decisions in light of the subsequent disaster. The interview questions were guided by the overarching research questions:

- What factors drive homeowners’ long-term mobility decisions to rebuild or relocate from their disaster-affected homes?

- How does a subsequent disaster affect homeowners’ perceptions of mobility decisions made before the recurrent event?

Interview questions broadly fell into one of seven categories:

- Property damage

- Disaster assistance recieved

- Long-term mobility decisions

- Preparations for Hurricane Florence

- Perceptions of natural disasters

- Demographic characteristics

- Concluding remarks

Each interviewee was first asked to describe the property damage (if any) sustained from Hurricanes Matthew and Florence, as well as whether—and how—Hurricane Florence affected or will affect the process of property acquisition, reconstruction, or elevation. The interviewee was then asked whether the homeowner(s) received any financial assistance following either hurricane, the source of these funds, and a rough timeline of the distribution of these funds. The third set of questions addressed the homeowner’s decision-making process to rebuild or relocate and, for those who will relocate, whether the subsequent property lies within the city. The fourth set of questions focused on the ways homeowners prepared their property for Hurricane Florence and any differences in their preparations for Hurricanes Matthew versus Florence. The interviewee was subsequently asked about the effects, if any, of Hurricane Florence on the homeowner’s decision to rebuild or relocate. The interviewees were asked to provide their age, income, gender, race and ethnicity, educational level, and marital status. In conclusion, the interviewee was asked whether he/she wished to see any changes to disaster recovery policy and, if so, to explain those changes.

The interviewees comprise a diverse demographic profile with respect to income, gender, race and ethnicity, educational level, and marital status. However, there is relatively less diversity in regard to age. The vast majority of interviewees (10) are 60 years of age or older, while six interviewees are 70 years of age or older. The pool consists of seven females and eight males and five African American, three Native American, and seven Caucasian interviewees who earn between approximately $9,000 and $200,000 per year. The sole source of income for five interviewees is governmental assistance—Social Security, disability, and/or Veterans Affairs; their monthly income amounts to no more than $1,000. The marital status of interviewees varies: six are married, four are widowed, one is divorced, and four are single. The educational attainment of interviewees also varies: four interviewees have graduate or professional degrees, while four never graduated from high school.

The authors encountered difficulty in establishing contact with and subsequently enrolling HMGP recipients in their research. Several weeks before conducting field research, the authors sent a recruitment letter to each HMGP recipient (properties were identified from a map published by the city). The authors sent letters to 70 homeowners. Seven recipients responded to the recruitment letters (a 10 percent response rate); the authors were able to initiate contact with and interview six of these recipients.

Upon arriving in the field, the authors discovered that about 76 recipients (three-quarters) had vacated their properties. The interviewees in this study owned four of those properties. Two of the fifteen interviewees (both of whom applied for property acquisition) had purchased another property before completing the property acquisition process and vacated their damaged property. The other two had temporarily moved into either a family member’s house or a vacation home. All four homeowners are of higher income. Although we interviewed several lower-income homeowners who remained in their disaster-affected homes, the results of this research do not necessarily reflect the opinions or experiences of lower-income homeowners who vacated their property after Hurricane Matthew. Another limitation posed by this study is the age of the interviewees: the vast majority (10) are 60 years or older; eight interviewees were retired or not seeking employment. It is more likely for elderly and/or retired homeowners to elect to remain in their properties. As such, the findings of this research may not reflect the opinions or experiences of younger and/or employed homeowners. It must also be noted that selection bias proves of concern to our research.

Results

Homeowner Selection of HMGP Status

Homeowners are broadly grouped into two categories: those who will remain (i.e., recipients of HMGP funds to elevate or reconstruct property) and those who will relocate (i.e., recipients of whose property was acquired through HMGP funds). The homeowners who elected to relocate are of higher financial means that those who chose to remain. Several factors shaped each homeowner’s decision to remain or relocate; however, recurring themes include the financial feasibility of purchasing another home, the hassle of relocation, the duration of homeownership of the disaster-affected home, the risk of subsequent disasters and willingness to accept such a risk, and a desire to remain in their current home and/or neighborhood. The following lists provide a brief summary of the primary reasons for electing to remain or relocate and are explored in detail thereafter.

Primary reasons homeowners chose to remain:

- The cost of purchasing another home is prohibitive

The interviewees who applied for property acquisition are of higher income than those who applied for property elevation or reconstruction and are currently employed, whereas the majority of those who elected to remain are retired and several rely solely on governmental assistance. Many of the homeowners who will remain in their disaster-affected homes expressed concern over the financial feasibility of purchasing another home. Without additional income to supplement the buyout settlement, many homeowners cannot afford to relocate. The interviewees also expressed an aversion to renting for financial reasons: “It [the home] was bought and paid for and no more than Social Security that me and [redacted] gets. We couldn’t afford to go out and start paying for another one because rent is so high.”

- Emotional attachment to the home and/or neighborhood

Many of the homeowners who elected to remain have lived in their disaster-affected home for several decades: “It’s been our home since I was a baby. So if I can keep it I want to keep it.” The emotional ties to the home and surrounding neighborhood, conveyed through the interviewee’s high degree of sentimentality toward their home, rendered property elevation or reconstruction the more appealing options

"I wanted to come back to my home. This is my home where I raised my kids and I raised my granddaughter. This is my home. I been here now going on 41 years. So yeah it’s the only place I knew."

- The hassle of starting over (purchasing another home, moving, etc.) is too high

In addition to the financial costs associated with purchasing a home, relocation also involves the costs incurred from the move itself in addition to the time, energy, and resources necessary to complete the move (i.e., hiring a moving company or enlisting the help of family or friends). The majority of the interviewees who elected to remain are 65 years of age or older and several depend solely on governmental assistance; as such, the financial costs and physical effort of moving proved an additional hassle to the financial burden of purchasing another home.

Primary reasons homeowners chose to relocate:

- The homeowner is weary from flooding and eager to avoid subsequent disasters

The interviewees who applied for property acquisition expressed an aversion to the risk of recurrent flooding and the hassle of handling the aftermath “Just tired of flooding. Don’t want to do it again.” Another interviewee echoed a similar sentiment: “We were dealing with a 500[-year] floodplain and it took us twice within 10 years so we said it’s time to go.”

In fact, one interviewee who had already purchased a subsequent property indicated that flood exposure significantly affected his decision to purchase that property: “I think our decision to [buy] in a non-flood zone was probably half the decision to buy this house if not more.”

- The homeowner can afford to purchase another home

The interviewees who applied for property acquisition had sufficient financial resources to relocate. In fact, one of the interviewees who applied for property acquisition had purchased another property before receiving the buyout settlement, while another had moved into a home he purchased over a decade ago. These interviewees also expressed concerns over their ability to sell their home on the private market. One interviewee told us “we [he and his wife] couldn’t have got it [the amount received from the buyout settlement] any other way….everybody knows particularly this street floods.” Another interviewee responded similarly: “I guess it depends you know… some people they have the money.”

Interviewees expressed no inclination to change their long-term mobility decisions in the aftermath of the repetitive disaster. If anything, Hurricane Florence actually solidified the decision of those who elected to relocate: “It [Hurricane Florence] reaffirmed our plan to get out of there.”

But even for the interviewees who chose to remain in their disaster-affected home, the threat of disaster did not outweigh their perception of the benefits and/or significance of their home and/or neighborhood.

The majority of interviewees did not prepare for Hurricane Florence—a few households moved furniture and vehicles to higher ground:

"With Matthew we figured out the afternoon pretty early we concluded that we were getting ready to get flooded and we spent several hours moving personal property upstairs and relocating our vehicles although we almost left that too late. They almost flooded because when the water started coming up it just came up really fast. Faster than I certainly anticipated. In Matthew we did a lot of small things like moving furniture and personal possessions upstairs, so they didn’t flood and as a consequence we saved an awful lot of stuff."

Another homeowner expressed remorse for not moving his belongings: “If I would have raised say the bed or whatever it wouldn’t have been damaged.”

Although hazard mitigation strategies generally include efforts to eliminate long-term risks, such as elevating the home or designating a safe room, moving furniture and vehicles can be considered preparedness by homeowners to reduce the effects of disasters.

The Significance of Place

Many of the interviewees who elected to remain have lived in their homes for several decades:

"I wanted to come back to my home. This is my home where I raised my kids and I raised my granddaughter. This is my home. I been here now going on 41 years. So yeah it’s the only place I knew."

For one interviewee, it was even her childhood home: “It’s been my family home….since I was a baby. So if I can keep it I want to keep it.”

The decades-long relationship to the home and community have created strong sentimental ties and place attachment that have played significant roles in homeowners’ decisions to remain.

Perceptions of the city’s reaction to the hurricanes

Several homeowners criticized the city’s response to Hurricane Matthew, which one homeowner said “was a disaster amongst itself.” One homeowner cited a delay in the city’s response: “There was a lot of lip service…. I don’t think the solutions to the problem was well executed because it took a long time for them to come around to really tell us what they want to do.” Another homeowner criticized the city’s lack of response to Hurricane Matthew: “I don’t know if our city government did anything that I can see.”

In particular, homeowners expressed skepticism (but also a degree of resignation) toward the timeline of the mitigation proceedings: “There’s just no excuse for the delay for it taking this long.” Several other homeowners voiced their frustration: “I’ve been in that program for over two years. And I figure it might be another two years.” Another homeowner said “It [mitigation proceedings] could be streamlined.” Frustration over the duration of mitigation led to fear over damage from a potential future storm: “But if another one [hurricane] come I don’t know if I’m going to be able to keep it [home]. I think it’s another three years before they even talk about elevation?”

However, some homeowners indicated that the city has improved its response to Hurricane Florence: “I think the city government really stepped up to the challenge in a lot of ways and I think they also benefited from the horrendous experience we had in Matthew and were much better prepared when Florence hit.” Another homeowner expressed a similar sentiment: “They were more prepared for Florence. I think they learned a little bit from where they went wrong with Matthew.”

Discussion

While long-term mobility decisions are affected by a variety of factors, wealth and the emotional ties to one’s home and/or neighborhood played particularly significant roles in interviewees’ decision-making processes. Higher-income households demonstrate a higher preference for relocation than less wealthy households. The interviewees who applied for property acquisition were among the highest-income interviewees. These results are consistent with the population of HMGP recipients: a higher proportion of homeowners in higher-income neighborhoods sought property acquisition than those in lower-income neighborhoods. Twelve of the 20 recipients (60 percent) with properties in higher-income neighborhoods are slated for property acquisition, while 35 of the 81 recipients (43.2 percent) with properties in lower-income neighborhoods were awarded property acquisition. Higher-income households can afford to incur a financial loss on their disaster-affected home and the costs associated with relocation, while lower-income households may face financial constraints related to housing affordability. While the financial strain imposed by relocation certainly played a large role in homeowners’ mobility decisions, homeowners’ emotional ties to their home and/or neighborhood also proved significant factors in their mobility decisions.

In addition, property elevation and reconstruction will likely entail a lengthy process. Thus far, the city has prioritized property acquisitions of wealthier HMGP recipients: buyout proceedings for homes located in one of the highest-income neighborhoods in the city have largely been completed. Meanwhile, in general, mitigation proceedings for homes in more socially vulnerable neighborhoods have not been initiated. In this regard, the city is perpetuating socioeconomic disparity in disaster recovery and may exacerbate the recovery process for its most socially vulnerable homeowners.

Future Work

There are several opportunities to expand on the findings from this study to improve knowledge on the long-term mobility decisions of disaster-affected homeowners. Perhaps the following questions that linger from this study will provide a foundation for future research:

- How long does the mitigation process last for HMGP recipients? Does the duration affect recipients’ perceptions of hazard mitigation and if so, how?

- Do homeowners express a desire to change their mobility decisions as mitigation proceeds?

Recommendations

Based on the information garnered from extensive interviews with homeowners and related individuals, the authors propose the following recommendations for planning and policy:

Socially vulnerable HMGP recipients should be prioritized in the mitigation process. Cities who have been awarded HMGP funds should focus first on mitigating the properties of socially vulnerable homeowners. While it is certainly important to mitigate the properties of all physically vulnerable owners, funds should be initially directed to those with the least resources—the most socially vulnerable households. These homeowners face greater susceptibility to adverse outcomes from future disasters and greater difficulty in the recovery process. As such, to alleviate socioeconomic disparities in households’ recovery trajectories, cities should prioritize the most socially vulnerable HMGP recipients in the mitigation process. In addition, governmental entities should be more proactive with hazard mitigation.

"The city—and I’m not talking about just our neighborhood but other neighborhoods in Lumberton—they could have been buying out the high-risk neighborhoods before we ever had a flood."

The devastation wrecked on the city of Lumberton by Hurricanes Matthew and Florence was largely the result of limited preventative measures in place. The paucity of hazard mitigation techniques intensified the damage from the storms, thereby exacerbating the intensity and duration of disaster recovery. The city indeed invested in hazard mitigation planning after Hurricane Matthew, resulting in the procurement of funds for property mitigation for individual homeowners as well as for structural reinforcements, including a floodgate. However, these efforts are complicated by the ongoing recovery from now not only one, but two flooding events. Investing in hazard mitigation before disaster strikes diminishes its ramifications on the community. Governmental entities should direct hazard mitigation efforts particularly toward socially vulnerable residents, who face the most significant hardships in recovery and prolonged recovery trajectories.

Finally, lower-income HMGP recipients should be equipped with the resources necessary to make buyouts a financially feasible option. Buyouts are a well-recognized mitigation technique promulgated by FEMA. However, buyouts often disadvantage lower-income households, who, unlike wealthier households, generally cannot afford to purchase a home in a non-physically vulnerable area. In other words, the buyout amount--the fair market value of the disaster-affected home--may not translate into the funds necessary to purchase a home that is not located in a flood-prone area. Wealthier households may apply supplemental income to the purchase of another home, an option generally not feasible for lower-income households.

Acknowledgements. This report is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF Award #1635593). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or the Natural Hazards Center. The authors express enormous gratitude to the Natural Hazards Center for funding this research, as well as to the National Institute for Standards and Technology Center of Excellence in Community Resilience Planning for their generosity in providing additional financial support. The authors also extend their gratitude to the individuals who participated in our research for their time, hospitality, sincerity, and kindness. We wish you the very best in recovery and many happy days ahead.

Endnotes

Endnote 1: Conversation between the authors and Brian Nolley, Community Development Administrator, City of Lumberton, on April 5, 2019.↩

Endnote 2: The authors used 2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates data from the U.S. Census Bureau for 2016 to reflect the demographic characteristics of the city prior to the hurricanes. ↩

Endnote 3: Approximately thirty HMGP recipients did not receive a letter from the authors as these homeowners were already enrolled in a concurrent research study conducted by the National Institute for Standards and Technology Center of Excellence in Community Resilience Planning. ↩

References

-

Berke, P. R., Kartez, J., & Wenger, D. (1993). Recovery after disaster: achieving sustainable development, mitigation and equity. Disasters, 17(2), 93-109. ↩

-

Elliott, J. R., & Pais, J. (2006). Race, class, and Hurricane Katrina: Social differences in human responses to disaster. Social science research, 35(2), 295-321. ↩

-

Mileti, D. (1999). Disasters by design: A reassessment of natural hazards in the United States: Joseph Henry Press. ↩

-

Muñoz, C., & Tate, E. (2016). Unequal recovery? Federal resource distribution after a Midwest flood disaster. International journal of environmental research and public health, 13(5), 507. ↩

-

Masterson, J. H., Peacock, W. G., Van Zandt, S. S., Grover, H., Schwarz, L. F., & Cooper, J. T. (2014). Planning for community resilience: Island Press. ↩

-

De Vries, D., & Fraser, J. (2012). Citizenship rights and voluntary decision making in post-disaster US. ↩

-

Nicholls, R. J., Wong, P. P., Burkett, V., Codignotto, J., Hay, J., McLean, R., . . . Arblaster, J. (2007). Coastal systems and low-lying areas. ↩

-

Bukvic, A., & Owen, G. (2017). Attitudes towards relocation following Hurricane Sandy: should we stay or should we go? Disasters, 41(1), 101-123. ↩

-

Fussell, E., Curtis, K. J., & DeWaard, J. (2014). Recovery migration to the City of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: a migration systems approach. Population and Environment, 35(3), 305-322. ↩

-

Fussell, E., Sastry, N., & VanLandingham, M. (2010). Race, socioeconomic status, and return migration to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Population and Environment, 31(1-3), 20-42. ↩

-

Asad, A. L. (2015). Contexts of reception, post-disaster migration, and socioeconomic mobility. Population and Environment, 36(3), 279-310. ↩

-

Kick, E. L., Fraser, J. C., Fulkerson, G. M., McKinney, L. A., & De Vries, D. H. (2011). Repetitive flood victims and acceptance of FEMA mitigation offers: an analysis with community–system policy implications. Disasters, 35(3), 510-539. ↩

-

Tate, E., Strong, A., Kraus, T., & Xiong, H. (2016). Flood recovery and property acquisition in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Natural Hazards, 80(3), 2055-2079. ↩

-

Xu, D., Peng, L., Liu, S., Su, C., Wang, X., & Chen, T. (2017). Influences of sense of place on farming households’ relocation willingness in areas threatened by geological disasters: Evidence from China. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 8(1), 16-32. ↩

-

Binder, S. B., Baker, C. K., & Barile, J. P. (2015). Rebuild or relocate? Resilience and postdisaster decision-making after Hurricane Sandy. American journal of community psychology, 56(1-2), 180-196. ↩

-

Rashid, H., Hunt, L. M., & Haider, W. (2007). Urban flood problems in Dhaka, Bangladesh: slum residents’ choices for relocation to flood-free areas. Environmental management, 40(1), 95-104. ↩

Seong, K., & Losey, C. (2020). To Remain or Relocate? Mobility Decisions of Homeowners Exposed to Recurrent Hurricanes (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 303). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/to-remain-or-relocate-mobility-decisions-of-homeowners-exposed-to-recurrent-hurricanes