The Effect of COVID-19 Vaccination on Evacuation Behavior During Hurricane Ida

Publication Date: 2022

Abstract

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, decision-making during disasters fundamentally changed to accommodate the combined risks of hurricanes and infectious diseases. Prior research conducted by this research team, and explained in detail in the literature review, examined how individuals changed their intended evacuation decision-making during the pandemic and actual evacuation decisions during Hurricanes Laura and Sally. Hurricane Ida provided further data on evacuation decision-making when vaccinations and masks were widely available. We conducted a digital survey of individuals affected by Hurricane Ida in 2021. Respondents provided information about their actual evacuation choices and perceptions of public shelters and COVID-19 risks. Compared to the 2020 hurricane season, more individuals have reduced negative perceptions of hurricane shelters. However, individuals were also much less likely to utilize public shelters than in the 2020 season, with 11.4% more individuals who stated that they would definitely or probably avoid using shelters in 2021. Fewer individuals identified that COVID-19 was a primary reason they chose to stay home during Hurricane Ida (19.5% compared to 86.8% during Hurricanes Laura and Sally). Furthermore, respondents with health risks for severe COVID-19 were no more likely to evacuate than those respondents who had no health risks. Potentially, as the pandemic progressed and vaccine availability and COVID-19 management improved, COVID-19 has had less impact on evacuation decision-making. The results from this work should guide planners in emergency management and public health in the 2022 hurricane season and future pandemics or other outbreaks to anticipate behavior changes and properly manage infectious disease threats.

Introduction

Emergency managers and communications experts have worked for decades to improve compliance with evacuation orders among residents in hurricane evacuation zones. However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 has made that task even more challenging as hurricane evacuations typically result in congregate sheltering for a significant amount of impacted populations, which are in direct conflict with the social distancing and isolation needs of the pandemic (Whytlaw et al., 20211). People evacuating from a hurricane must leave their homes and, in many cases, congregate with others in public spaces, hotels, or shelters—actions that directly conflict with public health guidance to socially distance and isolate in order to prevent infection and the spread of disease. Prior research conducted by Collins et al. (2021a2, 2021b3, 2021c4, 20225) examined how the COVID-19 pandemic affected how residents thought about and planned evacuation options for their households in the months prior to the 2020 and 2021 hurricane seasons. A follow-up study explored the actual evacuation behaviors of residents during Hurricanes Laura and Sally in 2020 (Collins et al., 2021c). These studies demonstrate that individuals develop a hyper-avoidance of sheltering and instead favor the risks of staying at home over the risks of virus transmission in congregate sheltering.

The purpose of this study was to document how a later stage of the pandemic—when masks and vaccinations were widely available and we better understood how the virus transmits—would influence the population’s hurricane risk perceptions and evacuation behaviors. This described later-stage COVID-19 context is likely to endure for several hurricane seasons, if not longer. Understanding how the public’s evacuation perceptions and behaviors evolved in this period can help guide emergency managers and other practitioners to promote higher rates of compliance with future evacuation orders.

The 2021 Hurricane Season and Hurricane Ida

The occurrence of Hurricane Ida in 2021 presented our research team with an opportunity to investigate evacuation behavior in a later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since December 2019, there have been 509.5 million cases of COVID-19 reported worldwide, with over six million deaths as of April 28, 2022 (World Health Organization, 20226). At the time of Hurricane Ida, vaccination was available, but only approximately 40% of Louisiana’s population was vaccinated (Mayo Clinic, 20217).

The 2021 hurricane season was above-average, with 21 named storms, ranking third for the most active hurricane years on record (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA], 20218). This trend will continue into the 2022 hurricane season (NOAA, 2021; Shipley, 20219) due to considerably warmer sea surface temperatures averaged across the tropical Atlantic and much lower vertical wind shear than average (NOAA, 2021). This heightened activity compounded by the pandemic poses additional challenges during the hurricane season.

Hurricane Laura made landfall as a Category 4 on August 27, 2020, as the strongest hurricane to hit Louisiana in over a century. This was the first time in recent history a mass evacuation occurred during a pandemic. One year later, while still recovering from the 2020 hurricane season, the region was impacted again on August 29, 2021, when Hurricane Ida made landfall as a Category 4 in Port Fourchon. Ida rapidly intensified in the days leading up to its landfall and had notable wind speeds, central pressures, tornadoes, and storm surge heights up to ten feet (Borenstein, 202110; Livingston, 202111). Ida tied with the Last Island Hurricane (1856) and Hurricane Laura (2020) for the strongest maximum sustained winds for a Louisiana landfalling hurricane on record, each with sustained winds of 150mph. Ida resulted in over 90 deaths (Hanchey, 202112) and at least $31 billion in damages, ranking it one of the costliest hurricanes recorded (Scism, 202113).

Hurricane experts remind residents to prepare the same for every season regardless of predicted activity. However, guidance during the 2020 and 2021 seasons has differed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. When Hurricane Ida made landfall, Louisiana was already dealing with a fourth surge of COVID-19 patients overwhelming their health care systems and diminishing existing resources due to the more severe Delta variant (Linderman & Galofaro, 202114). Epidemiologists are unsure if additional cases occurred due to Ida; however, there was a decrease in reported cases and hospitalizations related to COVID-19 in the weeks following the hurricane (Kiefer, 202115; Louisiana Department of Health, 202216). However, the data may not accurately portray the number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to the strain on local hospitals, halting of testing capacities, and evacuation of residents out of the area (Hanchey et al., 2021; Kiefer, 2021).

These compounding risks posed urgent challenges for those in the path of Hurricane Ida. Given that social distancing was warranted and capacity issues have historically plagued public shelters, there may have been competing priorities when deciding to evacuate. While non-congregate shelters were offered in the past (such as hotels used by local governments during the 2020 hurricane season), this was not a common practice during Hurricane Ida (Kiefer, 2021). Due to the pandemic, shelter operations following Hurricane Laura were primarily non-congregate options with limited use of traditional congregate shelters. Thousands of evacuees from impacted parishes in west Louisiana evacuated to larger metropolitan areas–primarily New Orleans–with higher-density development to immediately house and sustain large numbers of people in hotels.

In contrast, Hurricane Ida targeted New Orleans and strengthened rapidly during the approach, further reducing the ability to issue a mandatory evacuation across the New Orleans region. Emergency management plans do not support mass sheltering south of I-10 in Louisiana, including the New Orleans metropolitan area, or encourage vertical evacuation strategies (e.g., moving to higher levels of a structure in the case of an emergency). Due to the pandemic and continued infection concerns, non-congregate shelters across the state were once again prioritized and utilized outside Ida's immediate impact area.

Shifting to this emergency planning and response method meant non-congregate shelter options were less densely concentrated from city to city. The inability to target traditional congregate sheltering operations with large numbers of evacuees proved challenging for circulating a survey tool in both Hurricane Laura and Ida. A demonstrable density of non-congregate sheltering operations was employed during Hurricane Laura within a single jurisdiction due to the use of New Orleans-based hotels. During Hurricane Ida, these operations were much more scattered and crossed various jurisdictions. In both situations, the primary use of non-congregate sheltering options reduced survey reach to residents who evacuated to a traditional emergency shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic. The few survey respondents who did evacuate to a congregate shelter may have stayed in unplanned shelters—spontaneous shelters—opened by organizations that are not part of the official disaster response plan.

Hurricane Ida provided the ability to examine affected populations, many of whom had not recovered from a previous hurricane when Ida came through. Understandably, much of the U.S. population has no practical experience managing a hurricane evacuation during a highly communicable, infectious disease pandemic. COVID-19 poses a unique threat to evacuation shelter management and mass care compared to other infectious diseases which have affected prior hurricane evacuations. However, it is also important to note that the level of misinformation fueling public distrust impacts personal perceptions and behavior, further impeding the uptake of officials’ public safety messages. Emergency managers and public health officials from the government, private sector, and non-profit organizations need to better recognize the influence and impact COVID-19 potentially has on hurricane evacuation plans to improve existing strategies.

Literature Review

People form their decision to evacuate or not evacuate for several reasons. Senkbeil et al. (202017) and Morss et al. (201618) suggest that evacuation decision-making is a complicated puzzle as people receive different information via different forms of messaging which interacts with people’s physical and social stimuli. Many factors impact evacuation decisions, including predicted landfall location, storm severity, official warnings, mobile home residence, low lying areas, expected impacts, type of housing, social cues, individual assessment of their risk of injury, and past experiences with hurricanes and evacuations (Baker, 199119; Demuth et al., 201220; Dow & Cutter, 199821, 200022; Huang et al., 201623; Gladwin et al., 200124; Goldberg et al., 202025; Whitehead et al., 200026).

When local officials issue an evacuation order, the decision to comply and evacuate is the protective measure to ensure safety from hurricane hazards, including flooding, particularly from storm surge. However, many people still resist an order as they consider the negative consequences of evacuating, including the expense, chaos, frustration, and inconvenience. Past research (Goldberg et al., 2020) on evacuation decision-making has shown that people with previous hurricane experience will make the same decision in the future. For example, if they sheltered at home in the past, they will most likely shelter at home again, or if they evacuated, they will most likely evacuate again. This research was pre-pandemic though, and compounding the issues of hurricane evacuation with a pandemic, adds additional factors and complications to the decision-making process due to potential health concerns. When considering individuals who live in flood-prone areas in Florida, Botzen et al. (202227), for example, noted that COVID-19 concerns overshadowed flood risk perceptions and negatively impacted evacuation intentions.

COVID-19 and Evacuations

Research has greatly advanced our understanding of how residents perceive hurricane risk and make decisions about evacuating. Nevertheless, the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic created much uncertainty about how people’s perceptions and decision-making processes might alter in this new context. Previous research suggested some possible outcomes. For example, Bissell (198328) found that hurricanes are associated with higher rates of infection with endemic diseases in the area because large numbers of people seek shelter together in places that are especially conducive to the spread of disease via respiratory droplets. Likewise, Lemonick (201129) studied past disasters and disease associations and found that crowding increased disease transmission, a frequent concern in shelters. In addition, Ivers & Ryan (200630) found that after the impact of a natural hazard, "the congregating of displaced individuals" increased disease transmission. In another analysis of how tropical cyclones impact disease spread, Shultz et al. (200531) conducted a study on a wide variety of hurricanes and their associated disease outbreaks. They identified six factors that can play into infectious disease outbreaks, with one of these key concerns pertaining to changes in population density (especially in crowded shelters) which leads to increased exposure to contracting the virus. They further note that infectious disease outbreaks within the community after hurricanes are almost unheard of in developed countries; the concern is primarily in areas where people congregate and interact in close proximity.

Travers (202032) found that Americans generally hold one of five “types” of views regarding risk perception of COVID-19 and trust in the governmental response to the pandemic. Individuals fall into one of the following five categories: (1) “Sounding-all-alarms,” (2) “At risk,” (3) “Under-control,” (4) “Open-ups,” and (5) “Dismissers.” The largest group (Sound-all-alarms, 29%) feels that the federal response has fallen short and worries about things getting worse, whereas groups 4 and 5 (14% each) think there has been an exaggerated response to the threat.

Hurricane Evacuations in the Age of COVID-19: Prior Research by Author Team

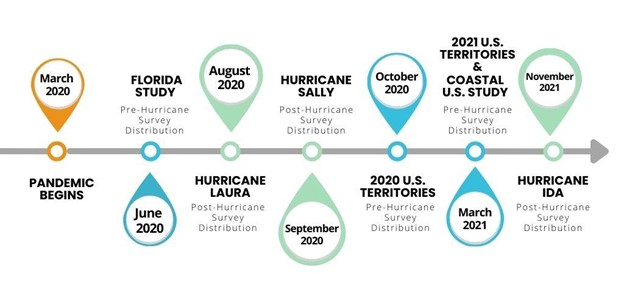

Hurricane Ida provides data that, compared to prior research on actual evacuation behavior in 2020 and anticipated evacuation behavior in 2021, create a timeline of the effect of COVID-19 on evacuation decision-making. Future work on this project will further explore the connections between prior and current research. As shown in Figure 1, the author team has conducted six prior surveys tackling concerns of COVID-19 during hurricane evacuations. These projects consisted of either pre-hurricane or post-hurricane surveying to capture both anticipated and actual evacuation behavior during the 2020 and 2021 hurricane seasons. The pre-evacuation surveys included four distinct projects: those residing in Florida or Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands in 2020 and then the coastal United States and the U.S. territories again in 2021. The post-evacuation surveys conducted after a hurricane landfall include Hurricanes Laura and Sally in 2020 and Hurricane Ida in 2021. All of the pre-hurricane surveys were very similar in question wording and length to allow for comparisons across the research projects; the same is true of the longer post-hurricane surveys. Similar questions shared between both the pre-and post-hurricane surveys include Likert-type questions that gathered data on individuals’ perceptions of shelters and the concern of COVID-19 in congregate spaces.

Figure 1. Timeline of Related Projects Conducted by the Research Team

The first of this research series was a pilot study conducted in Florida to measure anticipated evacuation behaviors entering into the 2020 hurricane season, the first season impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In June 2020, our research team disseminated an online survey (in both English and Spanish) of 40 questions to Florida residents through regional planning councils, emergency management agencies, and the media. In just over two weeks, 7,102 people from more than 50 counties responded to the survey (Collins et al., 2021b). Half of the survey respondents described themselves as vulnerable to COVID-19 due to their health status. In addition, 74.3% of individuals viewed the risk of being in a shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic as more dangerous than enduring a hurricane at home. A significant number of individuals noted that they would choose not to utilize a public shelter during COVID-19 when they would have previously, with a 7.7% decrease in the number of individuals who identified that they would definitely or probably use a shelter. In 2021, our team sent a follow-up survey to those residing in the coastal United States as a point of comparison to the Florida Study. However, this research included additional questions regarding vaccination status and its role in hurricane evacuations. Preliminary research from this project found that many individuals (71.3% of the sample) anticipated evacuation decision-making would not be affected by their vaccination status (Collins et al., 2021c).

When comparing the current research on Hurricane Ida, prior data from Hurricanes Laura and Sally has proven to be of great use. Since the research team used similar surveys from those deployed in 2020, these research projects yielded information on actual hurricane evacuation behavior for the two events for further comparative analysis. Key results from the study found that 76.7% of people stayed home and that, of those who stayed at home, 80% stated that the choice was somewhat attributable to concerns of COVID-19. However, for those who evacuated to somewhere other than a shelter or a hotel (15.8% of the overall sample), the majority (85%) stated that COVID-19 was not the primary reason they selected that evacuation choice. Regarding perceived vulnerability to COVID-19, 39.4% of those who experienced Hurricane Laura or Sally considered themselves vulnerable to COVID-19 due to pre-existing health concerns, and two-thirds of the sample stated that it would be “very serious” if they or their loved ones caught COVID-19. Finally, regarding perceptions of shelters, there was an observed negative perception of public shelters similar to responses seen in the pre-evacuation research and a significant decrease in the number of people who would utilize them during the pandemic who would have before (Collins et al., 2021c).

Research Design

Research Questions

As Hurricane Ida approached and evacuation orders were issued, residents balanced their need to evacuate against the risk of contracting COVID-19. The purpose of this research project is to examine how the state of the COVID-19 pandemic in Louisiana during the 2021 hurricane season—a context that includes the wide availability of vaccines and masks, greater scientific and public understanding of how the virus is transmitted, relaxed public health restrictions, and a surge in cases due to the highly contagious Delta variant—affected how residents’ perceived hurricane risks and made evacuation decisions. Ultimately, this study investigates the extent to which people risk their lives by sheltering in place rather than evacuating. The four primary research questions addressed in this study were:

- How did the later-stage COVID-19 context in August 2021 affect people’s hurricane risk perceptions and evacuation decisions?

- What concerns did residents have about COVID-19 in their potential evacuation sites, and how did these concerns influence their evacuation decisions?

- Did various health factors such as vaccination status affect evacuation choice?

- What sources of information did people rely on during Hurricane Ida’s evacuation, and did individuals feel the information was adequate?

Survey Design and Measures

Residents who were in the path of Hurricane Ida received an anonymous survey, available in both English and Spanish, through Qualtrics between November 1, 2021, and February 24, 2022. The Hurricane Evacuations in the Age of COVID-19 survey projects previously used by Collins et al. (2021c) to study evacuation behavior during Hurricanes Laura and Sally is available in a recent online data depository at https://doi.org/10.17603/ds2-ry5r-a653.

The research team initially designed the survey instrument during the 2020 hurricane season with input from emergency managers, planners, and other government officials to ensure the questions supported their planning and response efforts. Word consistency of questions allows for comparisons between surveys for various hurricanes throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. This current survey includes additional questions regarding vaccination status and its effect on evacuation decisions. Piloting both the English and Spanish survey instruments for Hurricanes Laura and Sally and the modified version used for Hurricane Ida ensured questions were understandable and strengthened the reliability of the survey instruments.

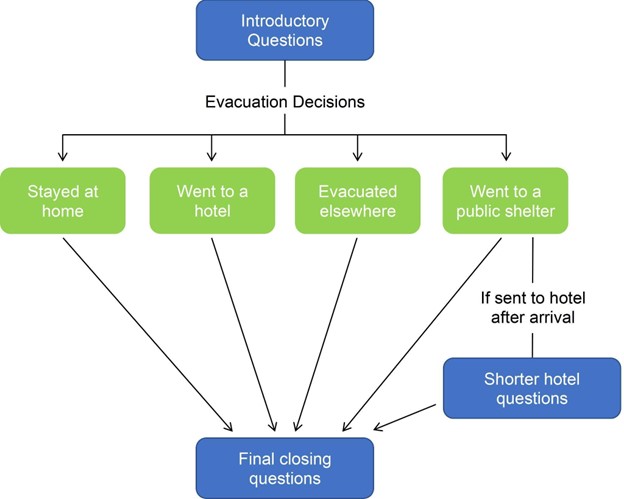

Respondents chose their evacuation decision from one of four primary options: (1) evacuated to a shelter, (2) evacuated to somewhere other than a hotel (but not to a shelter), (3) evacuated to a hotel, or (4) stayed at home. Individuals who evacuated to a shelter and then sent later to a hotel were asked additional questions from the hotel experience section (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Visual Display of the Branching Paths Offered Through the Survey Design

The survey contained 146 questions. Each option noted above contained approximately 80 questions, with those who stayed at home having the shortest questionnaire and those who went to a shelter that then sent them to a hotel being the longest. The median time for survey completion was 13.43 minutes. It was necessary to have a long survey to address the research questions and maintain the reliability of the survey instrument. The authors acknowledge that the length survey likely affected the number of completed surveys.

The survey asked participants several questions regarding their hurricane risk perceptions and the practical aspects of their evacuation experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other questions asked respondents about their health status and risks, their perceptions of shelters, and how their perceived risks of a hurricane compared to their perceived risks of contracting COVID-19. In addition, participants answered questions regarding social distancing and COVID-19 protection measures witnessed during their evacuation experience. The survey also included a section on vaccination status, the role of vaccination in evacuation decision-making, and impressions of vaccination in their local communities.

Sampling Strategy and Sample Demographics

To obtain participants for this survey study, the research team utilized a unique and diverse professional network developed in previous projects (Collins et al., 2021b, 2021c) to assist with distributing surveys to the local community, primarily through direct e-mail distribution and social media outlets hosted by our network of connections. This distribution network, which shared our survey with their communities, consists of regional partnerships within local emergency management offices in the affected areas, government officials, Ida-specific social media groups, and news media outlets. Additionally, partners from previous research projects about Hurricanes Sally and Laura employed in engineering, emergency management, public health, and communications also distributed promotional materials and survey links (see Figure 3) to their community contacts.

Figure 3. Example of Distribution Materials Provided to Professional Network

This sampling method represents a combination of convenience and snowball sampling which effectively identifies participants beyond the initial contacts engaged from affected areas due to challenges reaching individuals in a disaster setting. However, a disadvantage is the limited knowledge of true distribution in the affected areas and not guaranteeing the representativeness of the population. Nevertheless, despite having downfalls regarding representation, this process was an effective way of contacting this community, which is still recovering from the impacts of the hurricane. Furthermore, the research team decided to limit exposure to COVID-19 risks by not administering the survey in person.

At the beginning of the digital survey, the research team presented a consent form with information outlining the study as low-risk for participants. Following this step, participants confirmed if they were 18 or older and if they were affected by Hurricane Ida. If participants answered no to either question, the survey ended as they did not qualify to participate in the study. The survey had 124 unique respondents, most of whom (99%) completed it in English. They lived in 18 counties or parishes and 51 zip codes, primarily in Louisiana. The sample is not representative of the population in hurricane-prone areas of the United States. Compared to the U.S. Census estimates (U.S. Census Bureau, 201933), the sample from this study had a higher percentage of women (79.8% compared to a national average of 50.8%), less racial diversity (with 81.9% identifying as white compared to a national average of 76.3% and low representation from certain minority ethnicities), and a higher annual income (with many having a household income exceeding $90,000 when the national average is $62,843).

The sample also had higher rates of educational attainment. All respondents had completed high school compared to 88% in the national average. Moreover, 62.7% of our sample were college graduates, nearly two times the national average of 32.1%. The majority of the sample was employed full-time (60.6%); of note is that 14.9% identified as retired. Due to these demographic variations, this research may not be generalizable to the public at large in the region. (See Appendix for further demographic characteristics of the survey participants.)

As we discuss further in the Limitations section, it is important to acknowledge prior literature addressing the reasons that the sample has these demographic skews. As noted in prior research, digital and e-mail surveys are typically less representative than other forms of surveying, such as mail surveys (Dillman, 201134; Mackety, 200735; Tse, 199836). Further, these e-mail samples typically represent the middle and upper classes with a higher educational background and higher income and are whiter than the average compared to other survey methods (Kehoe et al., 199937; Mehta & Sividas, 199538; Sheehan & Hoy, 200039; Witte et al., 200040). Furthermore, women and white individuals typically respond more frequently to their counterparts in all survey modes (Green & Stager, 198641; Kehoe et al.,1999; McCabe et al., 200242).

Data Analysis

Data were downloaded from Qualtrics and imported into IBM SPSS v.26 to be cleaned, categorized, and organized for statistical analyses. Any short-answer questions, such as respondents’ descriptions of hazards near their homes, were broadly categorized by topic for analysis purposes. Due to many of the questions asked on this survey being categorical or ordinal in nature, the analysis included nonparametric testing (such as chi-square and McNemar’s tests) and simple frequencies with t-tests and ANOVAs used when relevant.

Ethical Considerations, Reciprocity, and Other Considerations

The University of South Florida Institutional Review Board approved this study (STUDY001517), and we followed standard consent and data management practices in order to protect participants’ confidentiality and privacy. Ethical considerations must be taken through all stages of the study, including the conceptualization, design, data analyses, and dissemination of findings. To accomplish this, we engaged practitioners and academics in the region from public health, epidemiology, emergency management, geosciences, meteorology, marketing, and communications early on in our research design process, data collection methods, and analyses. We knew many of these individuals from previous research projects, and by involving the partners at every stage, we ensured the research results would be of reciprocal benefit to both the research team and emergency managers and community leaders in the affected areas. As part of this approach to reciprocity, the research team has provided preliminary results to relevant stakeholders. To ensure representation and inclusivity, everyone on the research team engaged in reviewing existing literature, the grant writing process, research design, survey development, testing of the survey instrument, dissemination, and logistics (Oulahen, 202043). Further, bilingual speakers on our research team were involved in all stages to ensure the proper representation of those with limited English skills.

Findings

Risk Perceptions and Evacuation Decisions

Concerns for Specific Hurricane Hazards

An evacuation zone is a classification based on storm surge risks that emergency managers use to determine which broad areas should be under a mandatory evacuation order in the event of a hurricane. A flood zone is a FEMA-designated classification of vulnerability to flooding risks given on a local scale based on topography. Since both represent aspects of hurricane risks and states do not consistently employ evacuation zones, both were included. A little less than half (42.1%) of the sample lived in a flood or evacuation zone at the time of Hurricane Ida. Nearly one in ten (9.3%) did not know if they lived in a flood or evacuation zone.

Most of the sample (80.4%) were homeowners. Few (8.4%) lived in a mobile home at the time of Hurricane Ida. The majority of respondents (74.8%) sustained damages to their homes as a result of Hurricane Ida. Nearly half (42.7%) had concerns about their home or location prior to Hurricane Ida, mostly related to prior flooding concerns, proximity to a water source, or large trees that could fall.

Survey participants were asked to rate how concerned they were about a specific hurricane-related hazard on a Likert-type scale from “not concerned” (zero) to “extremely concerned” (four). Respondents were most concerned about the intensity/category of the storm (N = 101, x̄ = 3.56), wind speeds (N = 102, x̄ = 3.52), and wind gusts (N = 102, x̄ = 3.40). Respondents were least concerned about storm surge (N = 102, x̄ = 1.35), rainfall/flooding (N = 102, x̄ = 2.64), and tornadoes (N = 102, x̄ = 2.66). This information has been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Respondent Concern About Hazards at Their Residence

| Hazards of Concern | n | Mean Score (± S.D.) |

| Storm Surge | 102 | 1.35 (± 1.43) |

| Rainfall / Flooding | 102 | 2.64 (± 1.22) |

| Tornados | 101 | 2.66 (± 1.25) |

| Falling Trees | 101 | 2.83 (± 1.37) |

| Actual Storm Size (Width of Hurricane) | 102 | 3.13 (± 1.06) |

| Wind Gusts | 102 | 3.40 (± 0.86) |

| Wind Speed | 102 | 3.52 (± 0.90) |

| Intensity (Category of Storm) | 101 | 3.56 (± 0.83) |

General Evacuation Decisions

Regarding their actual evacuation decision for Hurricane Ida, 44.5% of the sample stayed at home, 0.8% went to a shelter and stayed in a shared space with other evacuees, 18.5% went to a hotel or motel (paid for by themselves or someone else), and 36.1% evacuated to the home of a friend or family member, stayed in their vehicle, or went to another location. A third (33.6%) of the group identified that they were under a mandatory evacuation order for Hurricane Ida, 60.5% were not, and 5.9% did not know if they were.

For those that were under a mandatory evacuation order, 35.0% stayed at home, 2.5% went to a shelter, 15.0% went to a hotel, and 47.5% evacuated to somewhere else. For those not under a mandatory evacuation order, 51.4% stayed at home, 0% went to a shelter, 20.8% went to a hotel, and 27.8% evacuated to somewhere else. As expected, those in a mandatory evacuation zone had a higher percentage of individuals evacuating somewhere else, and fewer stayed at home. However, the distinction of being under a mandatory evacuation order was not statistically related to specific evacuation choices or even the broader decision to stay or go, indicating it did not play a significant role in evacuation decision-making. This could be attributable to the smaller sample size of those under a mandatory evacuation (72 people) or due to the demographic skew of the sample, as those with more money may have more flexibility in their evacuation choices. Nearly one-quarter of respondents (24.5%) reported having to seek a secondary shelter after their original place of shelter was flooded, lost electricity, or was damaged. These individuals typically fled to the homes of friends or family (47.8%) or a hotel/motel (34.8%).

Most respondents (84.8%) had experienced a hurricane evacuation order before. During those previous events, nearly half (49.6%) of the respondents stated that they chose to stay at home, 4% went to a public shelter, and 55.4% had evacuated to another location such as the homes of friends and family or to a hotel or motel. Prior hurricane experiences were not significantly linked with evacuation choices made during Hurricane Ida.

Regarding hurricane preparedness, 69.8% of the sample had a hurricane evacuation plan, and 62.5% had a disaster kit prior to Hurricane Ida. More than half (54.2%) owned a generator. For those who did have a generator, 62.1% stated that it did affect their decision to evacuate or stay at home. For those who did not, 53.1% stated that not having a generator impacted their evacuation decision. There was a statistically significant relationship between generator ownership and evacuation choices, with those who owned generators being 28.4% more likely to stay at home than those who did not (X2(1) = 7.910, p = .005). Further, those who had a disaster kit before Ida were also 32.8% more likely to stay at home than evacuate (X2(1) = 9.980, p = .002). The research team did not see this relationship among those who had an evacuation plan, indicating that the presence of a disaster plan was not indicative of evacuation choice.

Nearly 80% of respondents answered affirmatively when asked, “Did the category of Hurricane Ida influence your evacuation decision?” When asked about hurricanes in general, three-quarters of the sample (75.5%) also stated that the category influenced their evacuation decision. Of this group, 35.3% stated that the lowest category they would evacuate for is Category 3, whereas 4.9% selected Category 1, 10.8% selected Category 2, 16.7% selected Category 4, and 7.8% selected Category 5.

When analyzing demographic effects on hurricane evacuation decisions, the study found no differences across the groups. These findings can be due to the limited sample demographics described above. Additionally, due to the low number of shelter evacuee respondents, no specific statistics will be presented from that sample group.

Perceptions of Evacuation Sites

Perceptions of Hotels

A small portion of this sample (18.5%) said they went to a hotel or motel. Although we asked if COVID-19 was the primary reason they chose to evacuate to a hotel, no respondents answered this question. No one in this study self-identified as being sent to a hotel from a public shelter. Additionally, no one identified having to separate members of their group at the hotel due to them having symptoms or being more at-risk. The majority (76.2%) of the sample covered their hotel stay by paying themselves or having a member of their household pay for the accommodations. Additionally, 9.5% had a family member or friend outside their household pay, and 4.8% had the cost covered by a non-profit or government organization. The overwhelming majority of the sample (90.5%) got to the hotel via personal vehicle, with the remainder (9.5%) carpooling to a hotel.

Participants' experiences with staff and guests at the hotel maintaining social distancing in common spaces varied, with 33.3% definitely agreeing, 28.6% somewhat agreeing, and 33.3% not agreeing at all. Regarding masks, 23.8% felt that staff and guests definitely masked in common spaces, 42.9% said somewhat, and 33.3% said not at all. No-one identified extreme difficulty with obtaining supplies to protect themselves from COVID-19 (e.g., hand sanitizers, masks, soap) while staying at the hotel, with 76.2% stating that it was not at all difficult and 23.8% stating it was somewhat difficult. Many individuals (85.7%) brought their own masks. A few respondents (9.5%) tested positive for COVID-19 after their hotel experience. Three-quarters (76.2%) of the sample had pets at the time of evacuation, and the overwhelming majority (93.8%) of those pet owners were able to bring their pets into the hotel.

Perceptions of Those Who Stayed at Home

Almost half (44.5%) of the sample stayed at home during Hurricane Ida. When asked if COVID-19 was the primary reason they stayed at home, 4.9% said definitely, 14.6% said somewhat, and 80.5% said not at all. When asked, “If I wanted to evacuate, I could have found friends or family to give me shelter IN my COUNTY,” 53.7% agreed. When asked the same question outside of the county, 65.9% agreed. Approximately a quarter (22.0%) wanted to evacuate but waited until it was too late.

Most (85.4%) of those who stayed at home had pets, and out of these pet owners, 65.7% stated that their pet played a major role in their choice to stay at home. Additionally, 7.3% stated that a lack of transportation did play a role in their choice to stay at home. A quarter (22.0%) stated that one of the reasons they chose not to evacuate was to care for someone else who either could not or would not leave.

Perceptions of Those Who Evacuated Elsewhere

Approximately a third of the sample (36.1%) evacuated their home and did not choose to go to a shelter or hotel. The majority (54.1%) of individuals who evacuated elsewhere identified that they stayed with their families. The remainder of the sample stayed with a friend or coworker (21.6%), at a vacation rental such as Airbnb (5.4%), stayed in their RV or car (5.4%), or did something else such as staying at a secondary owned property (8.1%). Most individuals (94.6%) got to this evacuation location via their personal vehicle.

The majority of participants (94.6%) stated that COVID-19 was not the primary reason they chose to evacuate to somewhere other than a shelter. Almost three-quarters (67.6%) of those who evacuated elsewhere had pets at the time of Hurricane Ida, and of those who had pets, only 28.0% stated that having pets influenced their decision to go somewhere other than a shelter. A small number of evacuees (5.4%) tested positive for COVID-19 within 14 days of their evacuation experience.

Perceptions of Public Shelters

A series of Likert-scale questions have been summarized in Table 2 that relate to aspects of individual perceptions of public shelters during COVID-19. When comparing the questions, “Prior to COVID-19, if I needed to evacuate to a shelter during hurricane season, I would most likely have done so,” and “Considering the current situation with COVID-19, I would still go to a shelter if I needed to during a hurricane evacuation order in 2020,” 11.4% more individuals stated that they would definitely or probably avoid using shelters in 2021. When comparing this willingness to use shelters before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a statistically significant decrease in potential shelter usage (p = 0.043) as determined through a McNemar’s test.

Table 2. Percent of Respondent Agreement With Statements Regarding Public Shelters During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Statement | Definitely True | Probably True | Probably False | Definitely True |

| “Prior to COVID-19, if I needed to evacuate to a shelter during hurricane season, I would most likely have done so.” a | 18.6 | 25.8 | 24.7 | 30.9 |

| “Considering the current situation with COVID-19, I would still go to a shelter if I needed to during a hurricane evacuation order in 2021.” a | 10.3 | 22.7 | 21.6 | 45.4 |

| “Now, after Hurricane Ida made landfall, I feel the same about the risks of a shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic.” b | 32.6 | 52.6 | 6.3 | 8.4 |

| “Prior to Hurricane Ida approaching, I felt that the risks of being in a shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic would be worse than staying at home and enduring the risks of a hurricane (e.g., storm surge, strong winds, etc.)” c | 25.0 | 33.3 | 27.1 | 14.6 |

| “I think if I went to a shelter, there would have been adequate safety measures in place to keep me safe from COVID-19, such as being able to social distance at least 6 ft. apart.” a | 12.4 | 17.5 | 29.9 | 40.2 |

COVID-19, Vaccination, and Perceived Health

The public health orders for COVID-19 in effect at the time of Hurricane Ida ranged by respondents’ county. The survey asked respondents what they believed their current restrictions were, to allow comparisons between those who believed that masking and isolation restrictions were in place against those who did not. A third (39.2%) stated that all restrictions were lifted in their county, 20.6% reported a stay-at-home recommendation, and 25.5% were unsure. Regarding mandatory masking, half (50.5%) believed that they lived in a county that enforced masking inside all public and commercial buildings, 28.7% of participants stated that masks were required in some places, and 9.9% said they were not required anywhere. A small portion (10.9%) did not know their masking requirements. When comparing this perception of restrictions against their evacuation choices, no significant relationship was found.

Slightly more than one-third (37.3%) of respondents reported having pre-existing health conditions, putting them at greater risk of serious illness if infected with COVID-19. When comparing this with vaccination status, those who considered themselves more vulnerable to COVID-19 were much more likely to have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, X2(3) = 13.438, p = 0.004. More specifically, 13.9% of respondents identified as immunocompromised, and 15.8% were over the age of 65. Moreover, half (50.5%) said they or someone in their household had an underlying medical condition associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 or made them eligible for special needs shelters, such as electricity dependence. Our analysis showed that those respondents with health risks for severe COVID-19 were no more likely to evacuate than those respondents who had no health risks. When observing evacuation choices of those with children, who could not vaccinate against COVID-19 at the time, there were no significant changes in the evacuation choice. However, those who had at least one individual over 65 years of age in their house were 35.6% more likely to evacuate somewhere (a hotel, shelter, or elsewhere) than stay at home (X2(1) = 8.355, p = .004).

When asked, “How serious would it be if you or someone in your household were to get COVID-19?”, 35.3% stated it would be very serious, 51.0% stated it would be somewhat serious, and 13.7% stated it would be not at all serious. There was no significant relationship between an individual's perception of COVID-19 severity and their choice to evacuate.

A quarter (24.2%) had someone in their household who tested positive prior to Hurricane Ida. Out of those who tested positive, approximately a third (29.2%) tested positive within 14 days of Hurricane Ida’s landfall. These results were not significantly related to the choice to evacuate or not, indicating that those who had previously tested positive, even within 14 days of landfall, did not have their decision-making significantly altered by this factor. We asked those who chose to evacuate (either to a shelter, hotel, or elsewhere) if they had tested positive following the evacuation. Out of those respondents who replied (58), many had not received a test following the evacuation. Only four (6.9%) reported that they had tested positive following their evacuation.

Many (76.0%) respondents knew someone who tested positive for COVID-19, 53.6% knew someone who was hospitalized due to COVID-19, 36% knew someone who was placed on a ventilator due to COVID-19, and 39.2% knew someone who had died due to COVID-19 complications. These numbers are slightly higher when compared to prior research from Pew Research Center in September 2020, which found that 39% of people knew someone who had been hospitalized or died due to COVID-19 (Kramer, 202044). This is potentially attributable to the fact that this survey occurred almost a year later, further into the course of the pandemic than the Pew study.

Regarding vaccination, 81.2% of individuals had identified that they had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Approximately one-third (39.6%) had received their booster dose, another third (35.6%) had received either two doses of Moderna or Pfizer or one dose of the Johnson and Johnson vaccine but not their booster; this survey was conducted prior to the approval of a fourth booster. Only 14.9% stated that they had no plans of getting vaccinated. Vaccination status was not statistically significantly related to age, evacuation choice, or gender. When asked if their vaccination status plays a role in their evacuation decision-making, 21.8% stated it did. When asked, “If more people in your county were to get vaccinated, would you have a different hurricane evacuation plan?”, 8.1% stated yes. These individuals who did say that vaccination status affected their decision to stay home or not were significantly more likely to have made the choice to stay at home than the rest of the sample, X2(4) = 9.987, p = .042.

Sources of Information for Evacuation Decision

Most of the sample felt that they were “provided enough information to make a good evacuation decision,” with 42.7% definitely agreeing with the statement, 43.7% somewhat agreeing, and 13.6% not at all agreeing. The survey asked participants to rank the sources of information that they relied on during their Hurricane Ida decision-making on a Likert-scale ranging from “not relied on at all” at 1 to “most relied on” at 5 (see Table 3). The most relied on sources of information were local media (N = 95, x̄ = 3.99), government officials (N = 89, x̄ = 3.38), and electronic media (N = 82, x̄ = 3.28). The least relied on sources were print media (N = 85, x̄ = 1.35) and family/friends far away (N = 47, x̄ - 1.47).

Table 3. Sources of Information Used to Make Prior Hurricane Evacuation Decisions

| Source of Information | n | Mean Score (± S.D.) |

| Local media | 95 | 3.99 (± 1.08) |

| Government officials | 89 | 3.38 (± 1.30) |

| Electronic media | 82 | 3.28 (± 1.25) |

| Family and friends nearby you | 90 | 3.03 (± 1.37) |

| National media | 96 | 2.66 (± 1.41)/td> |

| Neighbors | 88 | 2.51 (± 1.39) |

| Radio broadcasts | 87 | 2.49 (± 1.32) |

| Social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) | 91 | 2.45 (± 1.44) |

| Family and friends a distance away from you | 88 | 2.07 (± 1.41) |

| Other | 47 | 1.47 (± 1.08) |

| Print media | 85 | 1.35 (± 0.80) |

Discussion

As seen in past hurricanes, the largest group in the Hurricane Ida evacuation were those who stayed at home (44.5%). More people chose to evacuate to a location other than a shelter (e.g., a hotel or house of a friend or family member) than during Hurricane Sally (Collins et al., 2021c). This may be attributable to our sample demographics, wider adoption of emergency management recommendations to shelter in non-congregate places, and the increased severity of Hurricane Ida in comparison to Sally (but not to Laura). Further, the evacuation results for Hurricanes Laura and Ida are comparable, potentially due to the similar severity and similar geographic location of the two storm systems (see Appendix 2).

Those who used shelters only accounted for 0.8% of the study sample. This mirrors what was seen in prior research from the author group (Collins et al., 2021c) during Hurricanes Laura and Sally, where only 0.9% of the overall sample evacuated to a shelter. As shown in hurricane evacuation research, those who have access to more resources will typically choose an evacuation plan that does not involve public shelters as they are seen as undesirable, even before the pandemic (Perry & Lindell, 200745). Other research that measured shelter usage before the pandemic found an average evacuation rate of around 5%, ranging from 2% to 11% (Wong et al., 202146).

Compared to Collins et al.’s (2021c) research on Hurricanes Laura and Sally, fewer individuals identified that COVID-19 was a primary reason that they chose to stay home (80.5% stated it did not play a role at all during Hurricane Ida, while only 13.2% said that during Hurricanes Laura and Sally). These findings suggest that with the availability of vaccines and COVID-19 management which has improved; COVID-19 has had less of an impact on evacuation decision-making than in earlier stages of the pandemic.

Of note is that 22% of those who stayed at home wanted to evacuate but waited until it was too late, which shows that there is room for improved social support to encourage those who would evacuate to do so if they felt it was in their best interest. Further, this reflects an area of practical improvement for emergency management. Local emergency managers could work to improve physical resources such as transportation as well as improved and timely communications to the most-impactful sources of information (local media, government officials, and electronic media). These findings could also be attributable to the fact that Hurricane Ida went through what is known as rapid intensification, all but making pre-landfall evacuation orders impossible due to a compressed timeframe. Not having this mandatory pre-landfall evacuation order might have influenced these respondents' decisions, demonstrating the need to improve policies and further harden the infrastructure used for emergency shelters.

Louisiana had one of the lowest vaccination rates in the nation at the time of Hurricane Ida (with only approximately 40% of the population fully vaccinated), providing a unique environment for data collection regarding actual evacuation behavior and its connection to the COVID-19 pandemic (Mayo Clinic, 2021). When observing the role of vaccination on evacuation decision-making, 21.8% of individuals whom Hurricane Ida impacted stated that their vaccine status did play a role in their decision-making; these individuals were more likely than the sample to have chosen to stay at home, indicating that they may have chosen one of the other protective actions that increased COVID-19 exposure. This matches prior research done by Collins et al. (2021c) tracking the anticipated impact of vaccination on evacuation behavior in the coastal United States, where 29.6% stated it would play a role in the then-upcoming 2021 hurricane season.

Further, despite a third of the sample considering themselves more vulnerable to COVID-19, this perceived vulnerability did not impact evacuation decisions. This could also be due to the high percentage of individuals who decided to stay at home, which would be the expected response for anyone concerned about COVID-19 infection as remaining home is isolated and non-congregate. However, it may be due to people’s risk-taking behavior with COVID-19. In many other circumstances, when individuals perceive a threat as severe and imminent, people generally engage in more preventative behaviors, but this does not seem to hold true in the case of COVID-19. Studies conducted by Harper et al. (202047) and Pakpour & Griffiths (202048) show that although people have felt stressed, anxious, and fearful of COVID-19, those feelings did not match their behaviors of adopting preventative measures to reduce their risk of catching COVID-19.

Additionally, as shown in Table 2, people still have a negative perception of shelters which has worsened during the pandemic compared to non-pandemic situations. More than half (58.3%) of the participants identified that they felt the risks of staying in a shelter were greater than the risks they would experience staying home and enduring during a hurricane. This is lower than participants indicated during Hurricanes Sally and Laura, where 62.5% would rather risk hurricane conditions than COVID-19 infection in a shelter.

Of particular interest is the number of individuals who would have considered using a public shelter in the past who would no longer do so during the COVID-19 pandemic. Travers (2020) found that Americans generally hold one of five “types” of views regarding risk perception of COVID-19, with trust in the governmental response to the pandemic representing the largest group (29%) in which people feel that the federal response has fallen short and worry about things getting worse. This aligns with our study findings, where our data suggests a significant increase in the number of individuals (11.4%) that would disagree with the statement that they would use a shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic. This finding highlights poor perception and trust of public shelters during the pandemic. When asked to self-identify their likelihood to evacuate to a shelter before the COVID-19 pandemic and afterward, there was a statistically significant decrease in potential shelter usage, with 11.4% more individuals stating that they would definitely or probably avoid using shelters in 2021. This finding suggests that although individuals rarely utilize shelters during hurricane evacuations, those who may have previously chosen a sheltering option are choosing other evacuation options (such as staying at home or going elsewhere) directly resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. This shelter usage decrease was much more significant than what researchers saw during Hurricanes Laura and Sally (11.4% compared to 2.1%).

Compared to Hurricanes Laura and Sally, those who experienced Ida more often reported lacking enough information to make “a good evacuation decision” (13.2% compared to just 3.6% in 2020). This shows a need for improved communications and better-utilized communication channels during the upcoming hurricane seasons to increase message uptake and ensure that individuals have enough information to properly proceed with making a protective action decision.

Conclusions

Limitations and Strengths

One key strength of this research is how it fits into the existing work by Collins et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2022) conducted on hurricane evacuation decision-making during the pandemic. One critical limitation of the research is the low response rate. The team believes that this is likely due to survey fatigue seen in the professional distribution network and the surveyed population utilized in previous research done by Collins et al. since early 2020, as well as others. Due to team limits and an overabundance of caution for COVID-19 safety, the research team did not contact respondents in person to increase the response rate. An additional limitation is that a limited number of respondents used public shelters, leading to the inability to use a number of shelter-specific questions. As stated previously, the study sample is unrepresentative of the general U.S. population, limiting the generalizability of this research. The sampling method utilized could attribute to this factor; although not ideal for representation, this strategy is effective in disaster research (Norris, 200649; Price, 201350). This is of concern as various studies conclude that minority groups are a vulnerable population. Racial and ethnic minorities are at greater risk during pandemics since they often have less capacity to implement preparedness strategies or tolerate impacts given disparities in underlying health status and social factors, such as socioeconomic disadvantages, cultural, educational, linguistic barriers, and lack of access to health care (Hutchins et al., 200951).

Key Results and Impacts

Our Hurricane Ida research provides interesting results demonstrating COVID-19’s impact on evacuation decision-making further along the course of the pandemic. When compared to the 2020 hurricane season, in particular Hurricane Sally, more individuals affected by Ida are leaving their homes. Ida victims also seem to have fewer negative perceptions of hurricane shelters than Hurricane Sally. However, in direct conflict with this finding, individuals are also less likely to utilize public shelters during the COVID-19 pandemic than observed during Hurricanes Laura and Sally. This could be attributable to the skew of the Ida sample being more affluent, who are traditionally individuals who are less likely to use shelters. Further, compared to the 2020 hurricane season, fewer individuals identified that COVID-19 was a primary reason they chose to stay home (80.5% stated it did not play a role at all during Hurricane Ida compared to 13.2% during Hurricanes Sally and Laura). Indicating that with the availability of vaccines and improved management of the pandemic response, COVID-19 has had less of an impact on evacuation decision-making than in the past.

Individual perceptions of research respondents have been dynamic throughout the course of the COVID-19 pandemic as people weigh their personal health risks and the ever-changing COVID-19 exposure risks during hurricane evacuations. As displayed here, individuals seem to be more willing to evacuate when they need to instead of facing hurricane risks at their homes when it is dangerous, showing that people are adjusting to the balancing of COVID-19 and hurricane risks to make an appropriate evacuation decision. Further, as vaccines and masking have become more widely available, COVID-19 plays a much smaller role in many individuals’ evacuation planning. Although considerations for COVID-19 still need to be made in risk communications messaging and, most importantly, shelter planning, it seems to be less on the forefront of people’s minds than during the 2020 hurricane season.

This research and anticipated further analysis of the longitudinal data gathered by Collins et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2022) regarding COVID-19 and hurricane evacuation is important as COVID-19 poses a unique and widespread threat to shelter management and mass evacuations. This research provides not only additional knowledge on sociological perspectives during complex disasters but also provides guidance that is necessary for future planning during pandemic-hurricane events in the United States (Lindell et al., 201152; Whytlaw et al., 2021). Therefore, the results from this work should guide those in emergency management and public health planning not only for the 2022 hurricane season but also for future pandemics. Specifically, stakeholders should consider this research regarding anticipated behavioral changes in light of an infectious disease threat.

Acknowledgements. We would like to acknowledge critical collaborators to this project’s success, including those who assisted with translation services: Andrea Tristán, Antonio Piñero Crespo, and Carmen Crespo. In addition, we would like to acknowledge the funding and support from the Natural Hazards Center’s Quick Response Program as well as the NSF Research Experience for Undergraduate program in “Weather, Climate and Society” (NSF Award: 1659754, PIs: Collins and Ersing), which helped provide training for the student authors on this report. We thank student volunteers for their feedback and assistance with piloting these surveys in Spanish and English, and we appreciate the assistance of Delián Colón-Burgos, who assisted with graphics for this paper. Additional thanks to emergency management practitioners who provided feedback on the survey instrument before and during distribution. We thank those from numerous fields, including broadcast meteorology, emergency management, and others who assisted with disseminating the survey. Finally, we thank our anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback which has improved this report.

References

-

Whytlaw, J. L., Hutton, N., Yusuf, J. E., Richardson, T., Hill, S., Olanrewaju-Lasisi, T., Antwi-Nimarko, P., Landaeta, E., & Diaz, R. (2021). Changing vulnerability for hurricane evacuation during a pandemic: Issues and anticipated responses in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 61, 102386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102386 ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., Dunn, E., Maas, L., Ackerson, E., Valmond, J., Morales, E., & Colón- Burgos, D. (2021a). Compound hazards, evacuations, and shelter choices: Implications for public health practices in the Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Natural Hazards Center Public Health Report Series, 6. Boulder, CO: Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/compound-hazards-evacuations-and-shelter-choices ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., McSweeney, K., Colón-Burgos, D., & Jernigan, I. (2021b). Hurricane risk perceptions and evacuation decision-making in the age of COVID-19. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 102(4), E836–E848. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-20-0229.1 ↩

-

Collins, J., Polen, A., Dunn, E., & Welford, M. (2021c). NSF RAPID: Hurricane evacuations in the age of COVID-19. DesignSafe-CI. https://doi.org/10.17603/ds2-ry5r-a653 ↩

-

Collins, J. M., Polen, A., Dunn, E., Mass, L., Ackerson, E., Valmond, J., Morales, E., & Colón-Burgos, D. (2022). Hurricane hazards, evacuations, and sheltering: Evacuation decision making in the pre-vaccine era of the COVID-19 pandemic in the PRVI Region. Weather, Climate, and Society, 14(2), 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-21-0134.1 ↩

-

World Health Organization. (2022, April 28). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Retrieved April 28, 2022, from https://covid19.who.int/ ↩

-

Mayo Clinic. (2021). U.S. COVID-19 vaccine tracker: See your state’s progress. https://www.mayoclinic.org/coronavirus-covid-19/vaccine-tracker ↩

-

National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. (2021). Active 2021 Atlantic hurricane season officially ends. https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/active-2021-atlantic-hurricane-season-officially-ends ↩

-

Shipley, A. (2021). Colorado State University releases first look at 2022 hurricane season. Fox 4 News. https://www.fox4now.com/weather/weather-blogs/colorado-state-university-releases-first-look-at-2022-hurricane-season ↩

-

Borenstein, S. (2021). Ida: Exclamation point on record onslaught of US landfalls. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/environment-and-nature-science--85bbaba49c4b8374a29ecfc1cfb5cbbd ↩

-

Livingston, I. (2021). Ida’s impact from the Gulf Coast to Northeast - by the numbers. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2021/09/03/hurricane-ida-numbers-surge-wind-pressure-damage/ ↩

-

Hanchey, A., Schnall, A., Bayleyegn, T., Jiva, S., Khan, A., Siegel, V., Funk, R., Svendsen, E. (2021). Notes from the field: Deaths related to Hurricane Ida reported by media — nine states, August 29–September 9, 2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7039a3.htm ↩

-

Scism, L. (2021). Ida storm damage expected to cost insurers at least $31 billion. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ida-storm-damage-expected-to-cost-insurers-atleast-31-billion-11632303002 ↩

-

Linderman, J., & Galofaro, C. (2021). Ida and COVID-19: ‘Twin-demic’ slams Louisiana hospitals. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/hurricane-ida-environment-and-nature-louisiana-pandemics-health-e1ba589ce2b70b6fb3994fbe101c514f ↩

-

Kiefer, P. (2021). Gathering, evacuations during and after Ida worry epidemiologists as COVID delta surge continues. The Lens. https://thelensnola.org/2021/09/06/gatherings-evacuations-during-and-after-ida-worry-epidemiologists-as-covid-delta-surge-continues/ ↩

-

Louisiana Department of Health. (2022). COVID-19 information. https://ldh.la.gov/Coronavirus/ ↩

-

Senkbeil, J., Reed, J., Collins, J., Brothers, K., Saunders, M., Skeeter, W., Cerrito, E., Chakraborty, S., & Polen, A. (2020). Perceptions of hurricane—track forecasts in the United States. Weather, Climate, and Society, 12(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-19-0031.1 ↩

-

Morss, R. E., Demuth, J. L., Lazo, J. K., Dickinson, K., Lazrus, H., & Morrow, B. H. (2016). Understanding public hurricane evacuation decisions and responses to forecast and warning messages. Weather and Forecasting, 31(2), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1175/WAF-D-15-0066.1 ↩

-

Baker, E. J. (1991). Hurricane evacuation behavior. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 9(2), 287–310. ↩

-

Demuth, J. L., Morss, R. E., Morrow, B. H., & Lazo, J. K. (2012). Creation and communication of hurricane risk information. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 93(8), 1133–1145. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00150.1 ↩

-

Dow, K., & Cutter, S. L. (1998). Crying wolf: Repeat responses to hurricane evacuation orders. Coastal Management, 26(4), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920759809362356 ↩

-

Dow, K., & Cutter, S. (2000). Public orders and personal opinions: Household strategies for hurricane risk assessment. Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards, 2(4), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1464-2867(01)00014-6 ↩

-

Huang, S.-K., Lindell, M. K., & Prater, C. S. (2016). Who leaves and who stays? A review and statistical meta-analysis of hurricane evacuation studies. Environment and Behavior, 48(8), 991–1029. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916515578485 ↩

-

Gladwin, C. H., Gladwin, H., & Peacock, W. G. (2001). Modeling hurricane evacuation decisions with ethnographic methods. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 19(2), 117–143. http://www.ijmed.org/articles/479/ ↩

-

Goldberg, M. H., Marlon, J. R., Rosenthal, S. A., & Leiserowitz, A. (2020).A meta-cognitive approach to predicting hurricane evacuation behavior. Environmental Communication, 14(1), 6-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2019.1687100 ↩

-

Whitehead, J., Edwards, B., Vanwilligen, M., Maiolo, J., Wilson, K., & Smith, K. (2000). Heading for higher ground: Factors affecting real and hypothetical hurricane evacuation behavior.Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards, 2(4), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1464-2867(01)00013-4 ↩

-

Botzen, W. J. W., Mol, J. M., Robinson, P. J., Zhang, J., & Czajkowski, J. (2022). Individual hurricane evacuation intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights for risk communication and emergency management policies. Natural Hazards, 111(1), 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05064-2 ↩

-

Bissell, R. A. (1983). Delayed-impact infectious disease after a natural disaster. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 1(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/0736-4679(83)90010-0 ↩

-

Lemonick, D. M. (2011). Epidemics after natural disasters. American Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(3), 144–152. https://www.aapsus.org/wp-content/uploads/ajcmsix.pdf ↩

-

Ivers, L. C., & Ryan, E. T. (2006). Infectious diseases of severe weather-related and flood related natural disasters. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, 19(5), 408–414. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qco.0000244044.85393.9e ↩

-

Shultz, J. M., Russell, J., & Espinel, Z. (2005). Epidemiology of tropical cyclones: The dynamics of disaster, disease, and development. Epidemiologic Reviews, 27(1), 21–35. ↩

-

Travers, M. (2020, May 21). New psychological research identifies 5 types of COVID-19 sentiments. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/traversmark/2020/05/21/new-psychological-research-identifies-5-types-of-covid-19-fear/ ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). United States quick facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 ↩

-

Dillman, D. A. (2011). Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method -- 2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide. John Wiley & Sons. ↩

-

Mackety, D. M. (2007). Mail and web Surveys: A comparison of demographic characteristics and response quality when respondents self-select the survey administration mode. (Order No. 3278716) [Doctoral dissertation, Western Michigan University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/docview/304815411 ↩

-

Tse, A. C. B. (1998). Comparing response rate, response speed and response quality of two methods of sending questionnaires: E-mail vs. mail. International Journal of Market Research, 40(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078539804000407 ↩

-

Kehoe, C., Pitkow, J., Sutton, K., Aggarwal, G., & Rogers, J. (1999). Results of GVU’s tenth World Wide Web user survey. https://www.cc.gatech.edu/gvu/user_surveys/survey-1998-10/report.pdf ↩

-

Mehta, R., & Sivadas, E. (1995). Comparing response rates and response content in mail versus electronic mail surveys. Journal of the Market Research Society, 37(4), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078539503700407 ↩

-

Sheehan, K. B., & Hoy, M. (2000). Dimensions of privacy concern among online consumers. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 19(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.19.1.62.16949 ↩

-

Witte, J. C., Amoroso, L. M., & Howard, P. E. N. (2000). Research Methodology: Method and Representation in Internet-Based Survey Tools - Mobility, Community, and Cultural Identity in Survey2000. Social Science Computer Review, 18(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443930001800207 ↩

-

Green, K. E., & Stager, S. F. (1986). The effects of personalization, sex, locale, and level taught on educators’ responses to a mail survey. The Journal of Experimental Education, 54(4), 203–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1986.10806421 ↩

-

McCabe, S. E., Boyd, C. J., Couper, M. P., Crawford, S., & D’Arcy, H. (2002). Mode effects for collecting alcohol and other drug use data: Web and U.S. mail. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(6), 755–761. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2002.63.755 ↩

-

Oulahen, G., Vogel, B., & Gouett-Hanna, C. (2020). Quick response disaster research: Opportunities and challenges for a new funding program. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 11(5), 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-020-00299-2 ↩

-

Kramer, S. (2020). 14% of U.S. adults say they have tested positive for COVID-19 or are ‘pretty sure’ they have had it. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/14/14-of-u-s-adults-say-they-have-tested-positive-for-covid-19-or-are-pretty-sure-they-have-had-it/ ↩

-

Perry, R. W., & Lindell, M. K. (2007). Emergency planning. Wiley. ↩

-

Wong, S., Walker, J., & Shaheen, S. (2021). Bridging the gap between evacuations and the sharing economy. Transportation, 48(3), 1409–1458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-020-10101-3 ↩

-

Harper, C. A., Satchell, L. P., Fido, D., & Latzman, R. D. (2021). Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19(5), 1875–1888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00281-5 ↩

-

Pakpour, A. H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 and its role in preventive behaviors. Journal of Concurrent Disorders, 2(1), 58–63. https://concurrentdisorders.ca/2020/04/03/the-fear-of-covid-19-and-its-role-in-preventive-behaviors/ ↩

-

Norris, F. H. (2006). Disaster research methods: Past progress and future directions. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20109 ↩

-

Price, M. (2013, April 5). Convenience Samples: What they are, and what they should (and should not) be used for. Human Rights Data Analysis Group. http://hrdag.org/2013/04/05/convenience-samples-what-they-are ↩

-

Hutchins, S. S., Fiscella, K., Levine, R. S., Ompad, D. C., & McDonald, M. (2009). Protection of racial/ethnic minority populations during an influenza pandemic. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S2), S261–S270. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.161505 ↩

-

Lindell, M. K., Kang, J. E., & Prater, C. S. (2011). The logistics of household hurricane evacuation. Natural Hazards, 58(3), 1093–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-011-9715-x ↩

Polen, A., Collins, J., Dunn, E., Murphy, S., Jernigan, I., & McSweeney, K. (2022). The Effect of COVID-19 Vaccination on Evacuation Behavior During Hurricane Ida (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 344). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/the-effect-of-covid-19-vaccination-on-evacuation-behavior-during-hurricane-ida